Nava Atlas's Blog

February 13, 2026

Tarbell, Herrick & McCormick: Women Who Fought to Report Front Page News

Ida Tarbell, Genevieve Forbes Herrick, and Anne O’Hare McCormick, three trailblazing journalists from the early twentieth century, fought to report hard news — the kinds of stories that have a place on the front page.

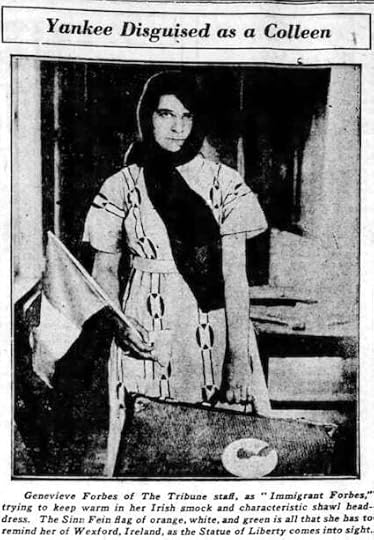

At right: Genevieve Forbes Herrick, who is very rarely depected in a photo.

The American newsroom of the first decades of the twentieth century, where front-page news was produced, was all but closed to women. Ishbell Ross, a respected journalist of the 1920s, believed that all city editors secretly thought: “Girls, we like you well enough, but we don’t altogether trust you.”

At the dawn of the 1900s, American journalism was changing at a dizzying pace. In newsrooms of major city papers, the clacking of typewriters had replaced the scribbling of pens. The linotype machine revolutionized the printing process. Now, each letter of type didn’t have to be set by hand.

Just as important, the kind of splashy undercover stories that made stunt girl reporters like Nellie Bly and Winifred Bonfils famous was falling out of favor. Investigative journalism, newly respectable, relied on careful research and fact-checking instead of wild set-ups and dramatic storytelling of earlier times.

Something else that was changing — finally — was the number of female journalists. In the 1880s there were just a few hundred in the entire country. By 1900 that number grew to nearly 2,200, and by the end of the 1930s, there were about 16,000 women in American journalism.

Sure, it was a great improvement. But the majority of “girl reporters,” as they were called, were assigned to women’s pages or features that weren’t front page news — society, home, fashion, and family.

Of course, there was nothing wrong (and there still isn’t) with covering those topics — if that’s what a woman reporter chose to do. But for the most part, female journalists weren’t given that choice and continued to be unwelcome in city newsrooms. That doesn’t mean that women had failed.

Women’s pages, as they were called, helped sell papers. By the 1930s, women were serving as editors, producing longer features and Sunday magazines, and working in business, art, mechanical, and promotional departments. Here, we’ll look at the careers of three women journalists whose hard news reporting made it to the front page despite the odds.

. . . . . . . . . .

Ida Tarbell

Ida M. Tarbell in 1904

Ida M. Tarbell (1857 – 1944) was known as “muckraker” — a word coined by president Theodore Roosevelt describing journalists who exposed big business’s shady dealings. He didn’t mean it as a compliment. Ida Tarbell’s reputation as a muckraker made her a pioneer in the new brand of detailed investigative journalism. She’s still considered one of the best ever.

Her most famous investigation was of Standard Oil’s unfair business practices, called The History of Standard Oil. This title might sound like a snoozefest, but Tarbell wrote the nineteen-part series in a way that captured readers’ imaginations and made them eager for the next installments.

Through her careful research, Tarbell proved that corporate monopolies hurt the public. Her series led to the 1911 Supreme Court decision that ruled against Standard Oil and broke it apart. Though this was the highlight of her career, Ida never stopped writing.

Tarbell was mainly interested in politics and presidents and was a Lincoln scholar. Strangely, she was against women’s right to vote, making her unpopular with other female journalists and reformers of her time. Still, whenever you see a list of most influential journalists of all time — male or female — Ida Tarbell’s name is always near the top.

. . . . . . . . . .

Genevieve Forbes Herrick

Herrick went undercover to investigate immigration in 1921

Genevieve Forbes Herrick (1894 – 1962) bridged the gap between stunt reporting and the newer breed of investigative journalist. Brilliant and ambitious, she joined the Chicago Tribune in 1921 with a master’s degree to her credit.

The Tribune wanted to steer her toward the women’s pages, but she refused. Instead, Herrick talked her editors into letting her pose as a poor Irish girl to experience what it was like to immigrate to America. Her reporting recounted the terror of the ocean voyage from Ireland and the terrible treatment immigrants faced after arriving through Ellis Island.

Herrick told the hidden truth of how women were forced to strip for unneeded medical exams; how passengers were kicked and shoved into lines by authorities; and how newly arrived parents and children were forcibly separated. Genevieve was asked to testify before the House of Representatives, which resulted in improved conditions at Ellis Island.

Because this exposé was so successful, the Tribune let Herrick report on whatever topics she chose. Through the 1920s and 1930s, she covered politics and promoted women running for office. One of them was Ruth Hanna McCormick, who ran for the House of Representatives in 1928 — and won.

Herrick’s reporting was fearless, whether she was going after Chicago’s corrupt politicians or the city’s mob bosses.

. . . . . . . . . .

Anne O’Hare McCormick

Anne O’Hare McCormick, 1941

(photo from the collection of the Library of Congress)

Anne O’Hare McCormick (1880–1954) started out freelancing for newspapers and magazines. Her career chugged along steadily, though writing about this and that wasn’t very exciting.

That changed in 1921 when her husband was sent to Europe for his work. She asked the New York Times’ managing editor if she could send him reports from overseas. For a woman to be a foreign correspondent was practically unheard of, but the editor agreed.

McCormick plunged right into some of the most challenging topics, including the first in-depth look at the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini’s rise to power. She documented and reported on the gathering storm of fascism in Europe.

In 1936, McCormick became the first woman to be appointed to the New York Times’ editorial board. The paper’s publisher instructed her: “You are to be the ‘freedom’ editor. It will be your job to stand up … and shout whenever freedom is interfered with in any part of the world.” The following year Anne won the Pulitzer Prize for foreign correspondence — another female first.

She continued to be an active journalist through the World War II years, and was called “the expert the experts looked up to.” Anne O’Hare McCormick often sounded the first alarm about dangerous dictators. She was trusted by American presidents and respected by everyday readers who learned about the world from her popular column, “Abroad.”

. . . . . . . . . . . .

More about trailblazing journalists on Literary Ladies Guide Radio Days: Trailblazing Women Journalists on the Airwaves Colonial America’s Intrepid Women Newspaper Publishers See the entire category featuring historic women journalistsThe post Tarbell, Herrick & McCormick: Women Who Fought to Report Front Page News appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 11, 2026

Rereading Favorite Books from Childhood — Literary Comfort Between Covers

Rereading favorite books from childhood as an adult is the literary equivalent of a warm bowl of comfort food or a soft blanket. Their nostalgic pull is undeniable, likely because the stories we want to return to usually invoke a feeling of safety and predictability — the opposite of what life often feels like to us as adults.

Here are seven such revisits, some focusing on single books, others on entire series. Let’s dive in with several by Literary Ladies Guide contributor Marcie McCauley, who is our resident expert on revisiting beloved children’s literature with an adult perspective. These are followed by two others, one by Nancy Snyder and another by Jill Fuller.

Here’s what’s ahead:

The Ramona series by Beverly ClearyThe Betsy-Tacy Books by Maud Hart LovelaceTuck Everlasting by Natalie BabbittHarriet the Spy by Louise FitzhughFrom the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweilerby E.L. KonigsburgDaddy-Long-Legs by Jean WebsterA Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’EngleLittle Women by Louisa May Alcott

How long has it been since you reread your favorite childhood book? Perhaps these musings will inspire you to pick one or two of them up again.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Revisiting the Ramona seriesby Beverly Cleary (1955 – 1999)

Marcie McCauley: “The sight of that smooth, faintly patterned cloth fills me with longing,” writes Beverly Cleary, recalling an early childhood memory of Thanksgiving. At first, a moment of calm for the young girl: anticipating relatives seated around the dining room table. Then, activity: she finds a bottle of blue ink, pours some out, presses her hands into it, then “all around the table I go, inking handprints on that smooth white cloth.”

You might guess that the lingering memory would be the moment of discovery. Instead: “All I recall is my satisfaction in marking with ink on that white surface.”

I also think of my fictional friend Ramona when I envision Beverly Bunn (the author’s pre-marriage name) sliding down the banister, trying to find the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow, pressing her nose against the barbershop window, yearning to look under the swinging doors of a saloon, feeling frustrated when the church ladies mistook her for a picture (a pitcher!) with big ears, and standing on the tilting seat of the fair’s Ferris Wheel.

The Ramona Quimby series kicked off in 1955 with Beezus and Ramona; the final entry in the series was Ramona’s World (1999.) Read the reset of Reading and Revisiting Beverly Cleary’s Ramona Quimby Stories.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

The Betsy-Tacy Books byMaud Hart Lovelace (1940 – 1955)

Marcie McCauley: Revisiting the Deep Valley novels by Maud Hart Lovelace (1892 – 1980) during the winter holiday season is a particular delight, though this American author’s stories can be enjoyed year-round.

Perhaps better known as the Betsy-Tacy books, the themes celebrated in these nostalgic novels for young readers are universal: friendship, devotion, love of home, ambition, and comfort. Though the novels were published in the 1940s, they take place in the early years of the twentieth century, when the author herself was growing up. (The first volume, Betsy-Tacy, begins in 1897, and the tenth, Betsy’s Wedding, takes place in 1917.)

The Betsy-Tacy books were based on her experiences growing up in Mankato, Minnesota. The Betsy-Tacy Companion by Sharla Scannell Whalen even contains a helpful chart that displays the names of the novels’ main characters alongside their real-life corollaries. But the enduring appeal of this series rests as much with their invented elements as their real-life, autobiographical links.

Read the rest of The Betsy-Tacy Books by Maud Hart Lovelace: An Appreciation.

. . . . . . . . . . .

On Rereading Tuck Everlastingby Natalie Babbitt (1975)

Marcie McCauley: When I first reread Tuck Everlasting, I was in my thirties. It was never one of my school texts: when I was a girl, it hadn’t yet achieved its iconic status. But the timing for me to rediscover this story, about how “dying’s part of the wheel, right there next to being born” was perfect.

Originally intended for middle grade children, this gracefully written story by Natalie Babbitt has resonated with readers of all ages. It explores the idea of eternal life, and its flip side, mortality. When 10-year-old Winnie Foster inadvertently comes upon the Tuck family, she learns that they became immortal when they drank from a spring on her family’s property.

They tell Winnie how they’ve watched life go by for decades, while they themselves never grow older. Winnie must decide if she’ll keep the Tucks’ secret, and whether she wants to join them on their immortal path. I had no idea that, when Tuck Everlasting was new, Michele Landsberg had heralded Babbitt’s exploration of death as “one of the most vivid and deeply felt passages in American children’s literature.”

Read the rest of Drinking from the Spring: On Rereading Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Revisiting Louise Fitzhugh’sHarriet the Spy (1964)

Marcie McCauley: Revisiting Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy as an adult, I’m no longer convinced that Harriet and I would have been friends off the page. We would never have summered together in Water Mill, Long Island. We would never have had a sleepover on a Saturday night while her parents attended a white-tie-and-tails party.

On the page, however, we could be best friends. Like me, Harriet is “just so about a lot of things” and the only kind of sandwich in her world is a tomato sandwich. When she “didn’t have a notebook it was hard for her to think” and she gets a “funny hole somewhere above her stomach” when she loses the person in her life who knows her best.

And perhaps most importantly, when she plays Town, she plays so hard that even her friends are like characters in her life – impediments to and inspirations for – doing the work of telling stories. In that sense, Harriet and I have lived in the same Town from the moment we met, and, even still, that Town is a place I visit every day.

Read the rest of Playing Town: Revisiting Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Revisiting E.L. Konigsburg’sMixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler (1968)

Marcie McCauley: E.L. Konigsburg summed up her stories as being about the “everyday, corn-flakes, worn-out-sneakers way of life” when she won the Newbery Award for her children’s novel From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler in 1968.

Marcie McCauley: E.L. Konigsburg summed up her stories as being about the “everyday, corn-flakes, worn-out-sneakers way of life” when she won the Newbery Award for her children’s novel From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler in 1968.This prize-winning novel was a favorite of mine from the first reading—the first sentence, even — because it begins with Claudia’s failure.

She knows she’s never going to be able to run away in “the old-fashioned way”— in the “heat of anger with a knapsack on her back.” She reflects on her situation and makes a plan: she learns to rise to meet challenges in her own way.

… In her 2013 obituary in the New York Times, Paul Vitello writes that Konigsburg’s “upbringing in small-town Pennsylvania, where she did not have great expectations, helped her as a writer.” As a small-town girl who saw just enough of her childhood outside the city in Claudia, I was old enough to realize how Konigsburg had helped me as a writer too — by suggesting that real-world events from your everyday life could fill up a storybook. That they could be “enough.”

Read the rest of Overnight in the Museum: Revisiting E.L. Konigsburg’s Mixed-Up Files.

. . . . . . . . . . .

On Rereading Daddy-Long-Legsby Jean Webster (1912)

Marcie McCauley: The summer I was twelve, I pulled a well-read and worn book from the shelves of the public library and discovered a story that seemed to be told directly to me. Behind the deceptively dull cover of Daddy-Long-Legs by Jean Webster (1912) were letters and drawings that pulled me hard and fast into Judy Abbott’s life—an orphan at boarding school.

So many of my favorite things were combined in this book: orphans and lonely childhoods, girls succeeding against the odds with their studious natures, boarding school and class events, and perhaps most of all, the burgeoning writer’s sensibility that I also enjoyed in Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy .

I borrowed and devoured Jean Webster’s Daddy-Long-Legs that very afternoon; I’ve revisited it many times. Judy’s orphan status reminded me of other favorite characters, from classics like Emily of New Moon (1923) by L.M. Montgomery, Ballet Shoes (1936) by Noel Streatfeild, and A Little Princess (1905) by Frances Hodgson Burnett.

Read the rest of Orphans and Boarding Schools: On Rereading Daddy-Long-Legs.

And here are another pair of grown-up revisits of childhood classics …

. . . . . . . . . . .

On Rereading A Wrinkle in Timeby Madeleine L”Engle (1962)

Nancy Snyder: I gave myself the best holiday present ever: rereading A Wrinkle in Time by our new Christmas tree. Rereading Madeleine L’Engle’s masterpiece was like visiting my oldest and dearest friend. A Wrinkle in Time is the book that ignited my reading obsession more than fifty years ago, and for that, I’m forever grateful.

… From my first reading decades ago to my most recent rereading, I have seen myself as Meg. I have stayed angry at the social and economic injustices that permeate our world, perceiving my anger as a necessary element to challenge and overcome such injustice.

Meg Murry is an incredible character. However, I also admire the skills of Calvin O’Keefe as a great communicator and an incredibly calm person. I also aspire to the great intelligence of Charles Wallace, but remember the warnings of Mrs. Whatsit. Charles’ magnificent mind may be accompanied by arrogance and pride, something we need to check ourselves of when we’re convinced our intelligence is infallible.

Read the rest of On Rereading A Wrinkle in Time: A Fifty-Year View.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Returning to Little Women by Louisa May Alcottfor Comfort and Guidance (1868)

Jill Fuller: I have always loved Little Women by Louisa May Alcott. There is no need for me to explain what it is about the writing and the characters that are so powerful and endearing, for I know that many, many readers have experienced it too. We laugh at Jo’s antics, feel Teddy’s heartbreak, and weep when Beth takes her last breath.

But with my most recent re-read of this classic, published in 1868 and beloved for generations, the book tugged at me a little bit more, pulled me in a little bit deeper, and spoke to me in a way it never had before … Perhaps it is because my husband and I read it out loud together. It’s amazing how much difference it makes to read with your voice, for it turns words from flat, two-dimensional blotches of ink into a conversation, a dream, a dramatic sigh.

The book took on a new life when I read it out loud, more real than before, more concrete, more alive. And sharing the reading experience together turned every evening into a literary date night. Now I will always have the memories of sharing Little Women (and all of the discussions and laughs and tears that accompanied it) with my husband.

Read the rest of Little Women: A Book I Come Back to for Comfort and Guidance.

The post Rereading Favorite Books from Childhood — Literary Comfort Between Covers appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 7, 2026

Where to Start with the Books of South African Writer Olive Schreiner

Olive Schreiner (1855 – 1920) was a South African writer and activist best known for her debut novel, The Story of an African Farm, first published in 1883 under the pseudonym Ralph Iron. It was republished in 1891 under her real name.

Today, Schreiner’s work is still widely studied, and she’s considered a pioneering anti-colonial feminist voice. She also wrote many articles, essays, and letters.

The following is a guide to Olive Schreiner’s books is for readers who would like a broader scope of her writing.

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Olive Schreiner

. . . . . . . . . .

Olive Schreiner was born in Wittebergen, Eastern Cape, South Africa. She was one of twelve children born to missionary parents Gottlob and Rebecca Schreiner.

Schreiner lived with one of her brothers, a headmaster in Cradock, from 1867. After becoming dissatisfied with Cradock, she worked as a governess for several Cape households. This period became the inspiration for The Story of an African Farm, a story considered partially autobiographical.

For most of her life, Olive was disillusioned with the restrictions and rules of traditional Victorian culture. Her critical, anti-establishment views led her to clash with many employers. She struggled to settle into a single job or home in her early years.

In 1881, Schreiner traveled to Southampton, England, to pursue medical studies. She was unable to continue, partially due to worsening respiratory health. The sudden change led her to pursue a career as a writer.

Her first short publication was a short story: “The Adventures of Master Towser,” which was published in the New College Magazine in 1881. She followed this up with an 1882 essay in the same publication titled “My First Day at the Cape.”

The Story of an African Farm was published in 1883 and has remained Schreiner’s best-known work. She continued publishing essays and shorter works: “A Dream of Wild Bees” in The Woman’s World (1889) and “Stray Thoughts on South Africa: The Wandering of the Boers” (1896).

Many of her writings would comment on socio-political issues of the time: particularly Colonial life, Victorian customs, observations on Southern Africa, and women’s rights.

She wrote “Letter on the Taal” in South African News (1905), referring to the rise of Cape Afrikaans against Colonial-dominant English. A more exhaustive collection of her letters and shorter essays is available at Olive Schreiner Letters.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Books by Olive SchreinerAfter the publication of The Story of an African Farm, Olive co-authored The Political Situation with her husband, whom she later divorced, citing a repeatedly unhappy marriage in her letters. Here are her major works:

The Story of an African Farm (1883)Olive Schreiner’s first novel has remained her best-known and most adapted work. The description following is from the 2008 reprint from Oxford University Press:

“Lyndall, Schreiner’s articulate young feminist, marks the entry of the controversial New Woman into nineteenth-century fiction. Raised as an orphan amid a makeshift family, she witnesses an intolerable world of colonial exploitation.

Desiring a formal education, she leaves the isolated farm for boarding school in her early teens, only to return four years later from an unhappy relationship. Unable to meet the demands of her mysterious lover, Lyndall retires to a house in Bloemfontein, where, delirious with exhaustion, she is unknowingly tended by an English farmer disguised as her female nurse. This is the devoted Gregory Rose, Schreiner’s daring embodiment of the sensitive New Man.

A cause célèbre when it appeared in London, The Story of an African Farm transformed the shape and course of the late-Victorian novel. From the haunting plains of South Africa’s high Karoo, Schreiner boldly addresses her society’s greatest fears — the loss of faith, the dissolution of marriage, and women’s social and political independence.”

The Political Situation (1896)The Political Situation was co-authored with her husband Samuel Cronwright-Schreiner, and centers around the Cape Colony’s political situation. At the time, the Cape was still under Colonial rule, though an increasing number of people began to opposite it.

Samuel was a farmer, though also a Freethinker who opposed Cecil John Rhodes. After her death, Samuel attracted controversy for his biography, The Life of Olive Schreiner (1924), and the posthumous publication of her works, which she explicitly forbade in her will.

Trooper Peter Halket of Mashonaland (1897)As it is described, “the story of one of Cecil John Rhodes’ young troopers lost in Mashonaland.” Mashonaland refers to a region in Zimbabwe – and might point to Olive’s overall knowledge of Africa and its political climate. The story’s protagonist is age twenty, and comes to encounter a savior-like figure who brings to light the turmoil of war.

Closer Union (1908)Closer Union, published in 1908, collected from a series of letters. This volume explores Schreiner’s thoughts on government. It explores what she considered the dangerous idea of unifying the four main colonies into one central government. This was one of her many politically focused works directly critical of colonialism and Cecil John Rhodes.

Woman and Labour (1911)Woman and Labour explored women’s rights and her thoughts on student and labor activism. While some consider the book to be wordy, it’s nonetheless a valuable collection. Her thoughts were quite revolutionary for the time. It begins, “The female labour movement of our day is, in its ultimate essence, an endeavour on the part of a section of the race to save itself from inactivity.”

Stories, Dreams and Allegories (1922)The essay collection Stories, Dreams and Allegories was published in 1922, or two years after Schreiner’s passing. This collection contains stories like ‘The Buddhist Priest’s Wife,’ wherein an unnamed woman’s life is recounted – and shines through her accomplishments, unusual for mainstream Victorian life.

Thoughts on South Africa (1923)If Schreiner’s other books explored family relationships and people, then Thoughts on South Africa was a book about its surroundings and scenery. Thoughts on South Africa focused on colonial life and her observations. In this book, she referred to what she saw as the Boer culture’s “antique faults and heroic virtues.”

From Man to Man (1926)Schreiner’s last novel may have possibly been one that she started writing in her teens. It remained unfinished at the time of her death. This was among the books published posthumously. Reviews have noted that it’s quite dissimilar to The Story of an African Farm; rather than exploring Victorian life, it seems directed at her critics and takes a hard turn toward escape from circumstances.

From Man to Man is the story of two sisters: one remains in the Cape Colony under British rule, while the other leaves the setting to explore her surroundings and self.

Other books and collectionsThe Political Situation (1896)Trooper Peter Halket of Mashonaland (1897)Closer Union (1908)Woman and Labour (1911)Stories, Dreams and Allegories (1922)Thoughts on South Africa (1923)From Man to Man (1926). . . . . . . . . .

Olive Schreiner in young adulthood

. . . . . . . . . .

With her health declining, Schreiner returned to England for treatment in 1913. World War I (which began in 1914) prevented her immediate return to South Africa. She finally returned in 1920 and died of chronic respiratory disease in Wynberg the same year. Her last work, The Dawn of Civilisation, was published after her death.

Schreiner was originally buried in Kimberley, South Africa. Her gravesite was later moved to Cradock in 1921, when Cronwright-Schreiner returned to Southern Africa. Her posthumous legacy includes a residence at Rhodes University named in her honor. The Oliver Schreiner Prize was established in 1961, and is awarded to exceptional works of poetry, prose, or drama.

The Story of an African Farm was adapted into a film in 2004. It was generally unfavorably reviewed. An earlier television series made in 1980 received more favorable reviews. A short documentary called In Search of Olive Schreiner (directed by Lisha Vosloo), exploring her life and legacy, was released in 2025 .

Inspired By Olive SchreinerSome of the authors inspired by Olive Schreiner’s writing include J.M. Coetzee, Doris Lessing, Nadine Gordimer, and Virginia Woolf. Her work continues to inspire more authors to find their voice; here is what some of these writers have had to say:

Virginia Woolf: Quoted in this study, Virginia Woolf both praised and criticized Schreiner: “The writer’s interests are local, her passions personal, and we cannot help suspecting that she has neither the width nor the strength to enter with sympathy into the experiences of minds differing from her own, or to debate questions calmly and reasonably.”

Nadine Gordimer wrote groundbreaking works like Burger’s Daughter and July’s People; she credited Schreiner’s work as one of her influences, and would call her “the broken-winged albatross of white liberal thinking.”

J.M. Coetzee: The author of Waiting for the Barbarians, admired Olive’s writing, though he criticized her work for skimming over other issues that existed at the time – such as racial segregation.

Doris Lessing wrote the 1968 afterword to The Story of an African Farm and remarked it to be, “one of those few rare books, on a frontier of the human mind.” Lessing herself won the 2007 Nobel Prize for Literature.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Alex J. Coyne, a journalist, author, and proofreader. He has written for a variety of publications and websites, with a radar calibrated for gothic, gonzo, and the weird. His features, posts, articles, and interviews have been published in People magazine, ATKV Taalgenoot, LitNet, The Citizen, Funds for Writers, and The South African, among other publications.

More by Alex Coyne on Literary Ladies Guide

Nadine Gordimer, South African Author and Activist 8 Essential Novels by South African Author Nadine Gordimer Jeanne Goosen, Author of We’re Not All Like That 6 Notable South African Women Poets The Banning of Nadine Gordimer’s Anti-Apartheid Novels Olive Schreiner, Author of The Story of a South African Farm 10 Unforgettable Books by South African Women Writers Ingrid Jonker, South African Poet and Anti-Apartheid ActivistThe post Where to Start with the Books of South African Writer Olive Schreiner appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

February 4, 2026

Overnight in the Museum: Revisiting E.L. Konigsburg’s Mixed-Up Files

E.L. Konigsburg summed up her stories as being about the “everyday, corn-flakes, worn-out-sneakers way of life” when she won the Newbery Award for her children’s novel From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler in 1968.

This prize-winning novel was a favorite of mine from the first reading—the first sentence, even — because it begins with Claudia’s failure.

She knows she’s never going to be able to run away in “the old-fashioned way”— in the “heat of anger with a knapsack on her back.” She reflects on her situation and makes a plan: she learns to rise to meet challenges in her own way.

Claudia’s organization skills are top-notch: from accumulating weeks of allowance, gathering essential supplies, brainstorming an exit strategy, to maintaining secrecy. And, above all, selecting the perfect destination: someplace comfortable, indoors, and beautiful. “Planning long and well was one of her special talents.” She selects The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Because she is one month away from turning twelve, she will still qualify for children’s fare and thus cut her transportation cost in half. Same for her brother Jamie, who is only nine years old. Although he’s not running away to protest “a lot of injustice” or a lack of “Claudia appreciation” at home, he’s up for what Claudia terms “the greatest adventure of our mutual lives.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about E.L. Konigsburg

. . . . . . . . . .

This kind of detail — the negotiation process, the dollars and cents of it all—captivated me, convinced me it was not only possible but real. And I knew about museums, because I’d been to the Royal Ontario Museum (commonly called the ROM) in Toronto.

For a small-town girl like me, Toronto equaled New York City; Claudia’s father worked in what everyone called the city, but the other adults (that she knew, that I knew) considered it “exhausting” and it “made them nervous.” But, like Claudia, I thought the city was elegant, important, and busy; like her, I thought a museum would be an excellent refuge.

Also like Claudia, I had a “concern for delicate details” and an abundance of caution: Claudia is “cautious (about everything but money)” and Jamie is “adventurous (about everything but money).”

I understood her outrage over having domestic chores to complete daily, while her brothers escaped all that; it rang true for me in an inexpressible way that had nothing to do with chores — I didn’t want to be a nurse, a secretary, or a teacher, but … something else, something exciting. If Claudia could figure out how to live inside a museum, I could figure out … other things, important things. Like … the city.

Relating to thrills and fears

Unlike Claudia, however, I had no siblings, no allowance, no supplies, and no inter-city train system. And there was one part of the museum (as I knew it) that both thrilled and frightened me; in a pie-chart of my childhood thoughts, the bat cave in the ROM occupied as vibrant and sizable a space as Saturday morning cartoons.

And it was an unavoidable horror for me, because it was situated at the end of the dinosaur gallery — my favorite place in the whole museum. I was like a kid in an advertisement, grabbing whichever adult’s hand I could reach, tugging in the direction of those skeletal figures; but the bat cave loomed at the end of it all.

The fear in Mixed-Up Files isn’t rooted in jump-scares: it’s the ordinary kind of fear when one is required to do a thing they’ve not successfully done before. Indeed, the first fearful moment for Claudia and James is a familiar part of their ordinary routine, when they are sitting in their usual seats on the school bus. Except that morning, they do not leave: they stay.

After the children have reached their destination and the others have exited, Claudia and Jamie hunch down in their seats, awaiting the bus’s next stop: its return to the city depot. They await the driver’s inspection — a daily routine they don’t normally observe, which might capture any belongings left behind, or two children who dare to depart from their familiar routine. In synch with them, I held my breath.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Recognizing universal childhood experiencesWhen Konigsburg taught at a private girls’ school before she was married, she recognized some universal childhood experiences that affected children from lower, middle, and upper-class families; she witnessed many children struggle to adjust to new situations.

She also noticed that children’s books did not reflect a variety of upbringings; she couldn’t see herself even in some of her favorites, like Mary Poppins and The Secret Garden, couldn’t see the kind of modest upbringing that she had, her ordinary (though strictly religious) girlhood in a Pennsylvania mill town. “So I need words for this reason,” she says: “to make a record of a place, suburban America, and a time, early autumn of the twentieth century.”

Konigsburg also witnessed her own three children’s experiences and noted their absence in children’s stories of their day. For instance, her first book — Jennifer, Hecate, Macbeth, William McKinley and Me, Elizabeth, also published in 1967 — was inspired by her daughter Laurie’s experience of being the new kid at school in Port Chester, New York. Konigsburg wanted to “tell how it is normal to be very comfortable on the outside but very uncomfortable on the inside. Tell how funny it all is.” This juxtaposition was something else I wouldn’t have been able to articulate, but which I yearned to have validated.

From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler was inspired by her children’s discomfort with being uncomfortable at a picnic, and her son Paul and daughter Laurie modeled for the illustrations (other books were inspired by the experiences of her youngest son and, later, her grandchildren).

You can see both Claudia and James appearing very comfortable on the outside, while feeling very uncomfortable on the inside, even on their first night in the museum. “Five-thirty in winter is dark, but nowhere seems as dark as the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Konigsburg writes.

There’s part of me that’s still afraid of the dark, inside and outside the museums of our everyday lives. It was dark in the ROM’s bat cave, but the dinosaurs were well lit. My favorite was the stegosaurus, and I lingered with it as long as I could: partly because I was so impressed by the sunrise swell of its massive plates, partly because there were only three more dinosaurs between the stegosaurus and the overarching terror at the other end of the wing.

Where the cave was curtained and only dimly lit in amber-colored recesses, with highly strung netting that resembled cobwebs above the suspended bats, and an unpredictable, screechy soundtrack emerging from seemingly every inch of the dusky display. (And, I swear, it was windy: but, how?)

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Following their first night in the darkened museum, Claudia and Jamie awaken with their stomachs feeling “like tubes of toothpaste that had been all squeezed out.” They are “unaccustomed to getting up so early, to feeling so unwashed, or feeling so hungry.”

Their discomfort has been limited, however. They were able to spend the night in the hall of the English Renaissance, where they were secreted from the night watchman’s view by the heavy curtains surrounding the bed. Thereafter, I routinely sought out and noted the best place to sleep in any museum I toured.

The displays of historical furnishings in the ROM, however, were all behind glass. And I didn’t care much about them anyway, except for one room from a later era, in which children had begun to inhabit their own separate spaces in the family home, with books and toys and a most sublime rocking horse.

There was no way to enter that walled-in space; I imagined people constructing it the way that I had constructed my project for the science fair — though it was small enough to fit atop my slanted wooden desk—backing themselves out as their work was completed, sealing the last pane of glass as they removed the leg last inside their diorama. What I couldn’t see — the hallways behind those exhibits, for instance—was neither a source of comfort nor fear. And the bat cave was nobody’s science project: it was real.

My father was puzzled by my simultaneous resistance of and obsession with the bat cave; he strained to convey that the cave was home to the bats (realizing, of course, that the world contained things far more frightening than bats).

My mother endured my unceasing chatter about the bat cave when I was nowhere near it, between museum visits, as I persisted in the idea that, on the next visit, I would remain wholly unmoved. In the future, I could look back on the preceding visit as a failure, but from a comfortable place in the present, I could make a plan.

. . . . . . . . . .

The 35th anniversary edition

. . . . . . . . . .

Looking back on Mixed-Up Files, introducing the 35th-anniversary edition published in 2002, Konigsburg itemizes what has changed since it won the Newbery. She considers the economic details particularly, and how many readers have complained that the sum of money on which Claudia and Jamie depended could not actually sustain them very long.

Demonstrating the suspended-in-time-ness of a good children’s book, even decades later; Mixed-Up Files wasn’t an object affixed with a publisher’s imprint and a copyright of 1967, but an enduring story about the importance—and comfort—of a well-executed plan that made the impossible possible.

She also explains that the bed in which Claudia and Jamie slept, enclosed in drapery, had been dismantled and removed. Much of the original setting and many circumstances had changed in the intervening years; regular adjustments — by visitors and runaways alike — would be required.

Konigsburg also highlights the 1965 New York Times’ article which contributed another part of the plot in Mixed-Up Files. One of ELK’s responsibilities in an early job obtained after she completed her science degree at what’s now Carnegie Mellon University, was to maintain files of articles clipped from newspapers and other publications: a habit she retained, a real-world habit that informed her fiction throughout her lifetime.

Konigsburg underscores, however, that the core of the story is not about any particular object housed in the museum; it’s clear that the “greatest discovery is not in finding out who made a statue but in finding out what makes you.” Anytime I needed to be reminded of that, I could reread Mixed-Up Files. Which I often did after my parents divorced.

After that, all my routines changed, and I no longer went regularly to the museum. I could count each visit on the fingertips of one hand, as I grew older and stopped holding other people’s hands, but still went, reliably, to the dinosaur gallery first. I grew older yet again, and I held my husband’s hand, and then the hands of my stepchildren, who never even flinched when it came to the bat cave.

Reflections following E.L. Konigsburg’s death

I was disproportionately sad when Konigsburg died, given that I’d never even seen her in person; she had passed through the whole gallery and, finally, reached the final exhibit. And, so, I reread Mixed-Up Files, prepared to feel that sort of distanced disappointment when the younger-you who once loved a book so completely has been subsumed by older-you who rates things differently.

I started rereading it on a Toronto streetcar and continued on the subway, not far from the ROM— moving towards the home I made in the city where the bat cave made its home. Feeling as though I had, at last, left behind that scared little girl, but not so far behind that I couldn’t still enjoy Mixed-Up Files just as much.

In her 2013 obituary in the New York Times, Paul Vitello writes that Konigsburg’s “upbringing in small-town Pennsylvania, where she did not have great expectations, helped her as a writer.” As a small-town girl who saw just enough of her childhood outside the city in Claudia, I was old enough to realize how Konigsburg had helped me as a writer too — by suggesting that real-world events from your everyday life could fill up a storybook. That they could be “enough.”

Yes, there are, literally, corn-flakes in Mixed-Up Files: Claudia collects the box tops and returns them by mail for a rebate. And there’s a corner in the museum, where you can kick off your sneakers and pull the drapes and not be surrounded by darkness and fear, but sleep soundly through the night.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Marcie McCauley, a graduate of the University of Western Ontario and the Humber College Creative Writing Program. She writes and reads (mostly women writers!) in Toronto, Canada. And she chats about it on Buried In Print and @buriedinprint.

More by Marcie McCauley on Literary Ladies Guide Lois Duncan, Author of I Know What You Did Last Summer Reading and Revisiting Beverly Cleary’s Ramona Quimby Stories Fact and Fiction in All This, and Heaven Too Sometimes You Have to Lie: The Life and Times of Louise Fitzhugh Revisiting Anna and the King of Siam Margaret Landon, Author of Anna and the King of Siam On Rereading Daddy-Long-Legs Jean Webster, Author of Daddy-Long-Legs The Betsy-Tacy Books by Maud Hart Lovelace Winifred Holtby, Author of South Riding Elizabeth Taylor, English Novelist Elizabeth Taylor’s Novels: Where to Begin Quotes from Elizabeth Taylor’s Fiction Quotes by English Novelist Elizabeth Taylor on Love & Loneliness Selma Lagerlöf, First Woman Nobelist in Literature Natalie Babbitt, Author of Tuck Everlasting On Rereading Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt Barbara Pym, English Author of Comedies of Manner Making Room to Grow in The Long Secret by Louise Fitzhugh Revisiting Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the SpyThe post Overnight in the Museum: Revisiting E.L. Konigsburg’s Mixed-Up Files appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 30, 2026

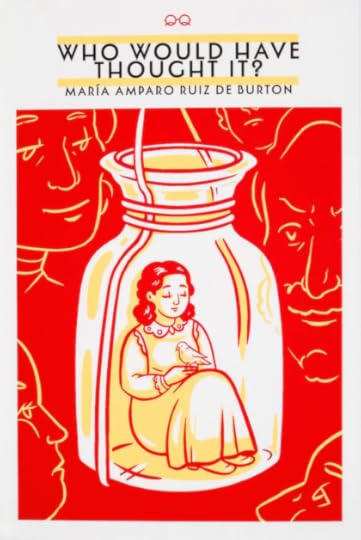

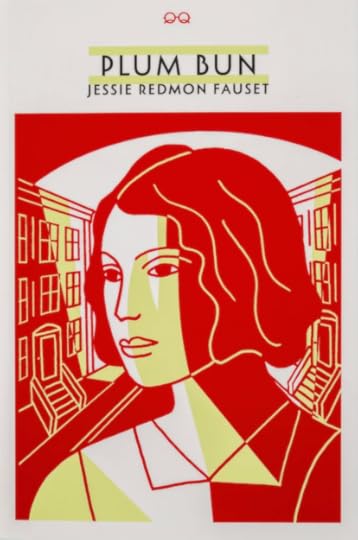

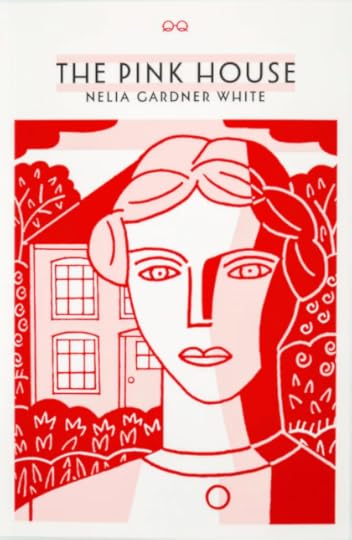

An Appreciation of The Pink House by Nelia Gardner White

The Pink House by Nelia Gardner White is a 1950 novel that has the feel of a timeless classic. Yet like the rest of Gardner’s large body of work, it fell out of print and remained obscure and hard to find.

That is, until recently, when Independent press Quite Literally Books reissued it in a handsome new edition in 2025.

It’s surprising that a writer of her caliber would be so thoroughly forgotten. Her books were well reviewed and sold well. She was even a pioneer in the realm of what we now call biofiction: Daughter of Time (1942) is a novelization of the tragically brief and brilliant life of short story master Katherine Mansfield. It was warmly reviewed in the New York Times.

You have to do some persistent digging to find good copies Nelia Gardner White titles. Other novels include Woman at the Window, The Merry Month of May, The Thorn Tree, David Strange, Hathaway House, and others, including No Trumpet Before Him, which will be briefly discussed ahead.

The new edition of The Pink House is available from Quite Literally Books. See a roundup of QLB’s current titles here on Literary Ladies Guide.

The following appreciation of The Pink House is by Tyler Scott, a Literary Ladies Guide contributor:

The Pink House: An Appreciation

“Out of the fullness of my heart I write down this story of my life. The snow is falling, silently, gently, beyond the panes. Every branch is limned with snow.”

Thus opens the novel The Pink House (1950) by Nelia Gardner White. When I was about twelve years old, my mother handed me this novel and explained that it had been her favorite when she was my age. This was in the Adirondacks, where we had a summer place, and every year after that, I read the book during vacation. It became my favorite.

Nelia Gardner White (1894 – 1957) was an extremely popular and prolific writer. She was born in Andrews Settlement, Pennsylvania, one of five children. Though they weren’t wealthy (her father was a Methodist minister), hers was a happy childhood. As she grew up, she worked odd jobs so she could attend Syracuse University (1911 to 1913). She then attended Emma Willard Kindergarten School from 1913 to 1915 to become a teacher. She married a lawyer and had two children.

In her early career, White wrote children’s stories, articles on child-rearing, and young adult novels, mostly set in small towns. Over time, she began writing for adults. She wrote some twenty-five novels, all (save for the 2025 reissue of The Pink House) out of print, as well as countless stories and articles for the top magazines, reaching millions of readers. The magazines in which her work was published included Ladies Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and McCall’s. A shorter version of The Pink House was serialized in The Woman’s Home Companion.

One of her career highlights was during World War II, when she was hired to write articles for the British Ministry of Information while living in England.

Now even more obscure than The Pink House, White’s 1948 novel, No Trumpet Before Him,, is the story of a Black man falsely accused of a crime and sentenced to death. It explores the power of a community coming together in the face of of racial injustice. No Trumpet Before Him was awarded the prestigious Westminster Fiction Prize, which came with a generous cash prize of $8,000 (equivalent to more than $100,000 today).

The Pink House is the story of Norah Holme. When the novel opens, seven-year-old Norah’s mother dies. Her father, who works overseas, doesn’t know what to do other than leave her with his sister and her family in their grand New England house, The Grange. Quiet and shy, Norah has scoliosis and uses a cane. Three of her cousins take an immediate dislike to her; only the oldest, Paul, shows her kindness. The spoiled cousins tease her, call her Toad, and won’t play with her.

Norah’s Aunt Rose is elegant, icy, and distant: the type of woman who has breakfast in bed and overspends. Her husband, Norah’s Uncle John, mostly keeps to himself and worries about money. Aunt Poll (John’s sister who lives with the family) takes Norah under her wing. Poll is stern and plain-speaking, but she ably educates Norah and teaches her to be tough, set goals, and live well despite her disability.

Norah’s growing strength and self-acceptance are qualities that may have appealed to post-war readers. It’s easy to see why the book made an impression on so many young women. The story is timeless and speaks to anyone who struggles with loneliness and lack of confidence while growing up.

White had a knack for building character and description. Her early works were sometimes criticized as sentimental women’s novels, but The Pink House defies this description. It’s a tableau of family life, with dynamics both good and bad. Secrets to be revealed keep the story moving forward, and, as the flyleaf of my original 1950 edition reads, “undercurrents of hate and frustration and mystery.”

I don’t want to divulge spoilers by give away the ending; however, in the end, good people prevail. With The Pink House, White wrote a novel in which even today, readers may find much to identify with, just as they did when it was originally published.

Excellent authors often leave us with wonderful quotes; this was one of my favorites from Nelia Gardner White on writing:

“One must have discipline, and discipline comes from failure, through writing thousands of words and using a few hundred of them, through filling the mind with great literature, through stretching the imagination to the utmost, through forgetting markets and concentrating on the immediate work. A surface cleverness is not enough.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Tyler Scott, who has been writing essays and articles since the early 1980s for various magazines and newspapers. In 2014 she published her novel The Excellent Advice of a Few Famous Painters. She lives in Blackstone, Virginia where she and her husband renovated a Queen Anne Revival house and enjoy small town life. Visit her at Pour the Coffee, Time to Write.

A sampling of original 1950 reviews of The Pink House

The Pink House was reviewed in dozens of newspapers, large and small, attesting to the author’s reputation. While occasional reviews were somewhat mixed, most were quite positive. It’s a testament to a fairly lengthy book that’s more character-driven than plot-driven, that many reviewers noted that it was hard to put down.

The Hartford (CT) Courant, Feb. 19, 1950:

“This is a drama of selfishness and greed and of warring personalities … The characters don’t quite ring true — they’re either too good or too bad. As a psychological study of Norah Holme alone, the book is fairly successful. And it has other points, too. Some of the descriptions of the New England countryside (the Pink House is in central Connecticut) are excellent. And it’s the kind of book you won’t want to put down until you’ve finished.”

The Pittsburgh (PA) Press, March 19, 1950:

“Hobbling around on crutches, our heroine learns many things in the gabled mansion — things that everybody has to learn sooner or later. She discovers things that are hateful in the midst of things that are full of love. Life, she learns, can be a cruel illusion as well as a beautiful reality. She loses none of her own charm, however, in the process. And the happy ending comes along, as the reader knew it inevitably would.”

The Lewiston (ME) Daily Sun, Feb. 27, 1950:

“It is well that not too many books like The Pink House are published often. People can’t sit up every night forgetting all about bedtime to finish a book. And The Pink House is that kind of a story. Once started, it is hard to put down this New England family story … Not that the family is charming. Far from it. or are they all blackguards. They are simply human beings, bad ones and good ones. And that is why the book casts such a spell.”

The post An Appreciation of The Pink House by Nelia Gardner White appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 27, 2026

Book-to-Film Adaptations directed by Mira Nair

In celebrating the success of Zohran Mamdani, the youthful maverick who took the office of New York City mayor in 2025, we might give credit where due to his mother, Mira Nair. She has been successful and influential in her own right as a filmmaker and director.

Zohran Mamdani’s meteoric political rise has created huge interest worldwide. Consideration of his origins might bring to mind the old adage, “the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world” — a reminder of the influence that mothers have on a society’s direction.

Early years and educationMira Nair was born in Rourkela, India. Shelived in many cities in India and developed a love for English Literature in high school, like many girls of the time. She majored in Sociology from Miranda House, a prestigious women’s college, where she also dabbled in theatre, including playing Cleopatra in Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra.

Nair also took part in political street theatre in Calcutta, with Bengal’s theatre luminary and playwright, . She later moved to the United States to study at Harvard on a scholarship (after turning down a full scholarship to Cambridge). The reason, in her own words: “I had a chip on my shoulder about the Brits.”

At Harvard, Nair studied photography before moving to filmmaking. Her career started with producing documentaries, and later moved on to making feature films. Her directorial debut, the Hindi language Salaam Bombay! (1988) earned nearly two dozen international awards.

. . . . . . . . . .

Mira Nair in 2008 (photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

. . . . . . . . . .

Praveen, Mira Nair’s mother, wielded a strong influence on her daughter, cultivating social awareness, confidence, independence, and fearlessness.

Nair’s early documentaries critique patriarchal attitudes and hypocritical notions of “virtue.” These attitudes were revealed in her documentary, India Cabaret (1985), which deals with the horrific practice of aborting fetuses after identifying them as female through amniocentesis (creating the term female feticide). Nair tackled this subject in another documentary, Children of Desired Sex (1987).

Her research for the feature film Mississippi Masala (1991), a romantic drama, took her to Uganda, where she met her second husband, Indo-Ugandan academic Mahmood Mamdani, whom she interviewed about Idi Amin’s expulsion of Asians from Uganda based on his book, From Citizen to Refugee.

Nair has never shied away from tackling bold, controversial themes in her filmmaking. Her love of literature led her to her turn to books for inspiration for many of her films. The choice of films and their adaptations speaks to her activist bent, which we see reflected in the values inherited by her son, Zohran Mamdani.

Monsoon Wedding

Before getting started with Mira Nair’s book-to-film adaptations, it would be remiss not to mention Monsoon Wedding (2001). Like Mississippi Masala, it was created from an original screenplay rather than a book. It’s generally considered Mira Nair’s magnum opus — her most critically praised and successful film. Rotten Tomatoes gave it a 95% rating, praising it as “An insightful, energetic blend of Hollywood and Bollywood styles … a colorful, exuberant celebration of modern-day India, family, love, and life.”

Set in Delhi, the film begins with preparations for the proverbial big fat Indian wedding, set in a traditional Hindu Punjabi household. revolves around the chaos of planning for such an extravaganza, with the extended family arriving from everywhere for the occasion. The baggage they arrive with, in addition to literal suitcases, is emotional.

Mira Nair is to be commended for handling the taboo issue of sexual abuse within families and ending it in a way that the audience feels that justice has been served. The film went on to win the Golden Lion at the 58th International Venice Film Festival of 2001, among other notable awards.

Following are notable book-to-film adaptations directed by Mira Nair.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

The Perez Family (1995)

The Perez Family, based on the novel by Christine Bell, saw Mira Nair embarking on an American comedy film. The story revolves on a bunch of Cuban refugees bearing the same name, Perez, who decide to band together as a family, in the hope that they will be able to stay on in the United States under this premise. One of them, in fact, tells a U.S. immigration official (who is also named Perez), “If you want something done in this life, ask a Perez – there are so many of us!”

The film, which casts a wary eye on the vagaries of the American immigration process, received mixed-to-positive reviews. Roger Ebert, for one, gave it four out of five stars, concluding, “The movie sometimes bends the plausible to set up a laugh, and most of the time I didn’t care, because I was enjoying the company of the characters.”

. . . . . . . . .

Vanity Fair (2004)

Nair’s film adaptation of the classic novel Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray gave it a modern spin. The film opens with its famous heroine, Becky Sharp (portrayed by Reese Witherspoon), watching her impoverished father sell off her mother’s portrait, an object that means so much to her.

As the portrait leaves the shop, so goes Becky’s last connection to her lineage, which will determine her future social mobility. Nair offers a kinder than usual interpretation of Becky, as she moves from orphan to governess to middle class.

While being accused by Western critics of making Becky a one-dimensional character, the film succeeds in showing the possibilities of a post-colonial production. Reviews were generally split down the middle. Some critics opined that Thackeray’s bawdy masterpiece had been rendered dull and safe. Yet others agreed with the Washington Post, which applauded “Mira Nair’s fine movie version of the 1848 book, in all its glory and scope and wit.”

. . . . . . . . .

The Namesake (2006)

film adaptation is based on , British-born daughter of Bengali parents. The story sympathetically explores the struggles of Ashoke and Ashima Ganguli, who have moved from West Bengal, India, to the United States.

Bengalis are known for giving unusual nicknames for their children. Ashoke and Ashima’s name for their son is Gogol (based on the Russian author Nikolai Gogol), which becomes his officially registered name.

The story shifts to Gogol and his cultural clashes with his parents over customs and traditions that he can’t relate to. The film brings out the dilemma of American-born children of Indian parents, and the story turns full circle as it moves to its final denouement.

The film was well received, appearing on several best-of-the-year lists. Rotten Tomatoes called it “An ambitious exploration of the immigrant experience with a talented cast that serves the material well.”

. . . . . . . . .

The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2012)

Based on Mohsin Hamid’s novel, the film adaptation of The Reluctant Fundamentalist is a gripping political thriller. The film revolves around Changez Khan, a Pakistani who admires the opportunities afforded by America for economic advancement.

Returning to America after a business trip post September 11th, Changez is horrified to be picked up and invasively strip-searched, leaving him furious and humiliated. After his U.S. visa expires, Changez returns to Lahore in Pakistan and is hired as a university lecturer. His travails continue to unfold from there.

The film deftly explores issues of identity and racial stereotyping, wrapped in a gripping story. Though The Reluctant Fundamentalist wasn’t a box office success and received mixed reviews, it won several prestigious international awards, including the Centenary Award at the 43rd International Film Festival in India for addressing burning issues such as intolerance and xenophobia.

. . . . . . . . .

The Queen of Katwe (2016)

The Queen of Katwe film is based on the biography by American Tim Crothers, subtitled One Girl’s Triumphant Path to Becoming a Chess Champion. The story tells of Phiona Mutesi, a girl living in Katwe, a slum of Kampala, the capital of Uganda, who becomes a chess prodigy.

After her victories at the World Chess Olympiads, Phiona becomes a Woman Candidate Master. The film traces the ups and downs of competition, with Phiona finally overcoming setbacks to lift her family out of poverty and buy them a home.

The film received critical acclaim and won several awards. Mira Nair said of her choice to make it: “I have always been surrounded by these stories, but hadn’t done anything in Uganda since 1971. I love any story about people who make something from what appears to be nothing.”

. . . . . . . . .

A Suitable Boy (2020)

Mira Nair directed the miniseries adaptation A Suitable Boy, based on Vikram Seth’s lengthy novel. It was the first BBC period drama series to feature a non-white cast.

Reception of the miniseries was decidedly mixed, often within the same reviews. The Guardian observed,“It is beautiful, expensive and groundbreaking in its casting, yet Andrew Davies’s adaptation of Vikram Seth’s tome still feels uncomfortably old-school.”

Other critics praised the cast and the settings, but panned the stereotypical portrayal of India. “There is no dearth of stereotypes in this adaptation of Vikram Seth’s 1993 novel,” wrote the critic of The Hindu, “yet the show moves too briskly and looks too lovely to ignore.” The film ran into a bit of controversy as well, mainly due to the characters of Lata and Kabir kissing in a temple. For some time, “Boycott Netflix” trended on Twitter until the next scandal came along.

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Melanie P. Kumar, a Bangalore, India-based independent writer who has always been fascinated with the magic of words. Links to some of her pieces can be found at gonewiththewindwithmelanie.wordpress.com.

Further reading

A Conversation with Mira Nair Mira Nair Movies & TV Shows BritannicaMORE BY MELANIE KUMAR ON LITERARY LADIES GUIDE

10 Classic Indian Women Authors Remembering Meena Alexander, Indian Poet & Scholar A House with Four Rooms by Rumer Godden Reminiscences of Enid Blyton Gone with the Wind‘s Melanie Wilkes Bangalore Literature Festival 2023The post Book-to-Film Adaptations directed by Mira Nair appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 22, 2026

Miriam Karpilove, Yiddish-Language Writer

Miriam Karpilove (1888 – 1956) was a Belarus-born immigrant writer of fiction in the Yiddish language, best known for Diary of a Lonely Girl (1918).

Photo at right: Miriam Karpilove, from the collection of David Karpilow.

Karpilove became well known for her serialized novels in the American Yiddish press, focusing on the lives of young Jewish women and exploring contemporary issues of gender roles, sexual mores, immigration, and cultural dislocation.

Early life and emigration from Belarus

Karpilove was born in a small town near Minsk, Belorussia (now Belarus) in 1888, though the exact date is unknown. She was the fifth of ten children in an observant household. Her father, Elijah, was a lumber merchant and builder. Her mother, Hannah, encouraged the secular and religious education of all their children, including the girls.

Karpilove was an early lover of literature, especially Russian, and composed her own poetry in the language. She trained as a photographer and photographic retoucher.

She emigrated to the US in 1905, one of thousands of Jews who were fleeing the Russian Empire as a result of economic hardship, antisemitic pogroms, and restrictions on Jewish life under Tsarist rule. She settled in New York City, among the growing communities of Eastern European Jews on the Lower East Side, and supported herself with work in a photography studio. Some of her brothers, who also emigrated, settled in Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Writing life in New York

Karpilove published her first writing in 1906, in the Yiddish newspaper Di idishe fon. This was the start of a fifty-year career during which she wrote short stories, novels, novellas, sketches, criticism, and play scripts.

Nearly all her work appeared in Yiddish newspapers and periodicals such as Tog, Kibitser, Forverts, Yidisher Kemfe, and Fraye Arbeter Shtime, and more than twenty of her novels were serialized (only five appeared in book form in her lifetime).

The Yiddish press, like the wider American press at that time, was largely male dominated. Karpilove was one of the very few women able to make a living from writing. Her work was hugely popular with readers, particularly female readers, but was mostly ignored by (male) critics of the time.

Throughout her writing career, Karpilove explored American urban life from the perspective of Jewish women, often young and independent immigrants, and portrayed themes of emotional isolation, cultural dislocation, sexual vulnerability, and the rapid social changes of the period.

She was frank about romantic and sexual encounters, although virginity and marriage remained ideals for most of her heroines – not out of prudishness, but as a critique of the way the new social and sexual trends left women vulnerable and often exploited.

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Diary of a Lonely Girl and other writingsHer breakthrough novel, Tagebukh fun an elender meydele, oder Der kamf kegen fraye libe (Diary of a Lonely Girl, or the Battle Against Free Love) was serialized in Di Varhayt from 1916-1918, before being published in book form in 1918.

The story is told through the diary entries and letters of an unnamed protagonist as she writes, in wry detail, of her love life among the tenements of New York’s Lower East Side. She rejects both the idea of arranged marriages from the “old world culture” and “free love.” The latter, condoning extramarital affairs with no commitment, was advocated by the secular, radical Bohemians of the “new culture.”

The novel contrasts male entitlement with the lack of real autonomy for women, highlighting the disproportionate social and legal consequences that women could face as a result of men’s pursuit of “free love.”

Under the 1909 Tenement Act, for example, a woman could be evicted or arrested for prostitution simply for having a male visitor in her rented room. Unsurprisingly, there were no such consequences for the male visitors. In one diary entry, the protagonist writes, “If free is what you want, don’t force me.”

Similarly, Yudis (Judith) is an epistolary novel that explores the relationship between a small-town Jewish girl, uprooted by antisemitic violence, and her revolutionary lover Joseph. In her letters, Judith details the experiences and challenges faced by young Jewish immigrant women who move between old and new worlds and navigate shifting cultural ideas.

Karpilove often wrote from her own life experiences. Her 1909 play In di shturm teg (In the Stormy Days) drew on her childhood in the Russian Empire, while another serialized novel, A Provincial Newspaper (1926), explored an early-career female journalist’s struggles with overt sexism in the workplace.

From 1929 to 1937, she served as a staff writer for the renowned Yiddish newspaper Forverts. She published seven novels and several short stories there during that time, as well as reporting on current events, and contributing personal observations and opinion pieces on topics such as labor conditions and the culture of the Jewish community.

Travels to Palestine

Karpilove became active in the Labor Zionist movement upon her arrival in the US. Her brother Jacob, whom she was close to and who settled in Bridgeport, became a prominent Zionist leader in the Poale Tsion movement, and she was the secretary of the local chapter in New York.

In 1926, she traveled to Palestine, hoping to settle there permanently. Before departing (in something of a disorganized rush), she wrote to Chaim Liberman, Secretary of the Yiddish Writers’ Union:

“Yes, dearest of all secretaries, I am going to the land of Israel. I will be leaving in about a month, on the first of September, 1926 … My weak head is dizzy with all of the things that I have to do for myself in order to leave from golus [diaspora]. I am my own moshiyekh’te [lady messiah] and, as you know, I have no white horse and, as you also know, the subway is on strike to boot. Therefore please accept my apologies for my distance, my tardiness, in following the aforementioned rules and regulations …”

She returned from Palestine three years later, unable to make ends meet there. Her autobiographical novel A Novel About Israel: My Three Years in Israel chronicles her time there. It hasn’t been translated in full, but is held in her archive at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. An excerpt, translated by Jessica Kirzane, can be viewed here.

Karpilove wasn’t impressed with the British government mandate then in charge of the country. In the novel, she wrote of the government officials:

“They didn’t like us. I could tell. But we couldn’t ask them why…we just had to ignore their cold, dry demeanor towards us immigrants. I doubt if we’ll be able to accomplish much in Eretz Yisrael under the Mandate that they use to squeeze money out of us. We can only accomplish things that are in their interest. On the way to Eretz Yisrael, we heard our fill about their decency, but now all we could do was console ourselves with the hope that it won’t always be this way. Someday we’ll come to an agreement. We will prevail.”

. . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .

Recent scholarly resurgenceKarpilove has experienced a recent resurgence, thanks to the efforts of scholar Jessica Kirzane at the University of Chicago, whose translations have made her work more accessible. Syracuse University Press published Diary of a Lonely Girl, or the Battle for Free Love, in 2020, and A Provincial Newspaper and Other Stories in 2023. Judith: A Tale of Love and Woe was published by Farlag Press in 2022.

Karpilove kept scrupulous lists of what she wrote, where and when it was published. This makes it possible to get a fuller view of her writing life compared with other women’s, whose writing has been lost. Contemporary scholars place her as a sophisticated observer of Jewish women’s life: Kirzane says that Karpilove gives the reader “a provocative, audacious portrait of Jewish womanhood that maybe we wouldn’t get in the same way elsewhere.”

However, there is also an acknowledgement that in many of Karpilove’s short stories, particularly those written during and after her time in Palestine, there is a distinct element of racism and orientalism that was common among Westerners at the time.

Her narrators often portray Arabs in a negative light, blaming their own moral failings and not systemic or political failure. Critic Sarah Imroff, in reviewing Kirzane’s translation of A Provincial Newspaper, wrote that, “With no critique internal to the stories, it is difficult to conclude that Karpilove herself did not also hold some of these views.”

Kirzane, in her introduction, wrote that, “It is important to note Karpilove’s racism in the text, particularly because she sees herself as outside of the ideologically strident voices calling for the exclusive use of Jewish labor over Arab labor.”

Personal life and later years

Karpilove never married or had children. Among her family, she was closest to her brother Joseph, and around 1938, she moved from New York to Bridgeport to help him care for his ailing wife, Annie. She then stayed to care for Joseph after Annie died.

From postcards written in the 1940s to her friend and fellow Yiddish writer Bertha Kling. It can be gleaned that she desperately missed the bohemian atmosphere of Yiddish New York and the gatherings at Kling’s home that she would once have been a part of.

She wrote that if she had still been in New York, she would not have missed a single meeting, and said, “I think it’s long overdue that women writers should have the chance to hear each other. The power has been in the hands of male writers for too long.”

In her later years, she suffered from ill health, although there are no specifics on record. She died in Bridgeport in early 1956, with various sources citing March or May.

Her great-nephew, David Karpilow, remembered her as “a woman ahead of her time … a strong feminist, an early beatnik…unique within the family. I recall her reading a lot and having strong opinions … she was an intellectual, certainly in her own way. Her experiences were vast.”

. . . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris. Find more of her writings here and on Literary Ladies Guide.

Further readingThree books are available in English, all translated by Jessica Kirzane:

Diary of a Lonely Girl, or the Battle for Free Love (Syracuse University Press, 2020) Judith: A Tale of Love and Woe (Farlag Press, 2022) A Provincial Newspaper and Other Stories (Syracuse University Press, 2023)More about Miriam Karpilove

Jewish Women’s Archive Diary of a Lonely Girl: A Queer Reading Miriam Karpilove’s FOMOThe post Miriam Karpilove, Yiddish-Language Writer appeared first on Literary Ladies Guide.

January 17, 2026

5 Thriller-Crafting Lessons from Patricia Highsmith

Did you know that Patricia Highsmith, who rose to fame with novels like Strangers on a Train (1950) and The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955), also wrote about writing? Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction is a delightful cross between an instructional guide and a personal diary sharing her own processes, struggles, and triumphs.

Highsmith is considered one of America’s greatest writers of psychological thrillers. Her books are must-reads for anyone aspiring to write crime or suspense fiction. (Incidentally, The Price of Salt (later republished as Carol and adapted into the 2015 film), is a seminal work in LGBTQ+ literature.)

First published in 1983, Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction, remained Highsmith’s only full-length nonfiction book. In it she shares much wisdom to offer those who aspire to write in this genre. Gathered here are five crucial takeaways for would-be thriller authors.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

1. Make your anti-heroes fascinatingAs writers, we’re often told that our protagonists must be likable, or else readers won’t care about the story. Highsmith, however, disagreed with that. She claimed that your main character doesn’t have to be likable, so long as they’re fascinating — for example, if they’re so compellingly evil that the reader can’t turn away.

Many of Highsmith’s protagonists are anti-heroes who manage to be both fascinating and likable. In The Talented Mr. Ripley, Tom Ripley is tasked with persuading a prodigal son to return home, but instead murders him and assumes his identity and wealth. Naturally, readers wouldn’t condone this behavior in real life — yet somehow, we’re invested in his fate.

We’re curious as to what he’ll do next and whether he’ll get away with his crimes. Plus, we actually kind of like him (if we overlook his unfortunate murder habit!). We appreciate his artistic and culinary tastes and his loyalty to his friends, plus we feel sorry for him because of his rotten upbringing. This ability to make us root for a cold-blooded killer is one of the reasons Highsmith is so well-acclaimed.

If you want to write your own anti-hero, you can ensure they’re sufficiently fascinating by giving them ordinary, relatable traits or interests. Above all, build a character who is realistically complex and not, as Highsmith put it, “monotonously brutal.” You want your reader to ask themselves, “How can someone who does such a normal thing as X also commit such a heinous crime as Y?”

. . . . . . . . . .

Learn more about Patricia Highsmith

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

. . . . . . . . . .

To showcase your protagonist’s complexity, you’ll probably want to let the reader in on their private thoughts and feelings. However, Highsmith advised against writing your thriller in the first person. This is a somewhat controversial tip and you’re welcome to ignore it — but hear her out before making your decision, so you can at least mitigate the risks she identified.

Highsmith’s objections to first-person POV stem from her personal impressions of “I”-sentences. When attempting on two separate occasions to write in the first person, all she could see in her head was the narrator sitting at a desk writing their story — an image she proclaimed to be “fatal” to the suspense genre. Indeed, knowing the narrator lives to write their tale makes the reader less fearful for the character.

Highsmith’s other impression of first-person narrators, particularly morally reprehensible ones, was that they come across as “nasty schemers.” The level of self-awareness required for proper introspection sounds ridiculous in the voice of someone whose actions can’t be justified by any sane reader. A third-person narrator, on the other hand, can relate subconscious thoughts and feelings and convey the same information in a less obnoxious or incredulous manner.

Thus, Highsmith recommended a third-person POV with one or two main viewpoint characters. I’ll leave it to you to decide whether to heed her advice.

. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . .

3. Stretch the reader’s credulity — but don’t break itMy favorite Highsmith novel, Strangers on a Train, jumps between two third-person POV characters. The first is Guy Haines, a perfectly ordinary architect whose unfaithful wife is refusing to cooperate with divorce proceedings. The second is Charles Bruno, a charming psychopath who resents his father.

The entire novel is based on a chance encounter on a train. The two men get talking and Bruno suggests they “trade” murders: he’ll murder Haines’s wife, and Haines can murder his father. Naturally, Haines doesn’t take the idea seriously, but Bruno actually does murder Haines’s wife, then blackmails Haines into upholding his end of the bargain.