Sangeet Paul Choudary's Blog

November 30, 2025

The 'bento box' guide to the Reshuffle of professional services

Japanese convenience stores sell millions of bento boxes each day. You’ve probably come across one before.

Most of us see the bento box and appreciate its near-ornamental visual aesthetic. But what’s most interesting about the bento box is not quite visible.

The bento is a collection of constraints that defines the structure of an entire industry behind it.

The box fixes the shape of the meal. Those constraints determine the workflow of the kitchen. And that workflow fixes the architecture of the entire supply chain.

Start with the box first. Its compartments dictate portion sizes and enforce consistency. Every meal must fit the grid.

This forces producers to engineer machinery that can portion ingredients with remarkable precision. Rice dispensers release exactly the right amount and cutters produce identically sized slices. The box’s dimensions determine the logic and parameters of the machines.

These machines, in turn, set production expectations. Farmers standardize produce and seafood suppliers target consistent cuts. Even the chemistry of sauces is stabilized so viscosity doesn’t disrupt portioning equipment.

Those production constraints also show up in logistics. Because bentos are perishable, the system must replenish stock many times per day. Cold-chain trucks are run on fixed schedule loops calibrated to store-level demand. Factories operate in short, intense bursts to prepare batches that match the expected sales by hour, not by day. On the distribution end, convenience stores design their shelves around predictable bento turnover, refreshing inventory multiple times per shift.

The architecture of the entire industry is determined by the constraints imposed by the bento box and its attached workflow. The stability of the bento workflow creates predictability. Predictability allows tighter coordination. Tighter coordination allows higher throughput.

The bento box illustrates how product and workflow constraints eventually determine industry architecture - the underlying structure that defines how work is divided, and how value and control are distributed across an ecosystem.

Sign up here if you haven’t already.

The ‘bento box’ guide to industry architectureThe surprising lesson of the bento box has important implications for the future of work today.

It shows that industries don’t simply choose their architecture. They are shaped around constraints. If those constraints change, the entire architecture of the industry changes alongside.

Professional services industries, today, are structured around similar constraints. Their workflows look nothing like a bento line, yet they display the same deep interdependence between what happens at the task level and what emerges as industry structure.

The work of a lawyer or auditor is document-centric, sequential, and heavily reliant on human interpretation.

Because humans can only process so much information at a time (the dominant constraint), the industry’s architecture is built around sampling techniques, multi-layered review chains, and periodic cycles to manage those constraints.

Specifically, the industry is structured around four key constraints.

1. Human speed and attention: Work must be done sequentially, step-by-step, with human review, because humans cannot monitor continuous flows of data.

2. Document-based evidence: Information is trapped in documents. Understanding that information requires humans to assess these documents.

3. Sampling and periodicity: These industries rely on episodic reviews in the form of annual audits, yearly underwriting, and periodic inspections.

4. Fragmented, heterogeneous data: Data is scattered across incompatible formats or unstructured documents. Humans do the stitching and translation to make sense of it.

These constraints also dictate industry architecture. There’s a structured cause-and-effect chain that locks in the industry’s architecture:

Regulation defines structure: Because of the constraints inherent to manual reviews and decision-making, regulators advocate fixed workflows and traceability requirements that ensure predictability.

Structure defines business model: Pricing models are anchored to billable hours. This is backed by the organizational pyramid structure, where lower-priced juniors help expand margin.

Business model defines skill/work patterns: Partner economics are structured around leverage i.e. how many juniors each senior could oversee. This produces junior-heavy, manual workflows.

This is a locked system. Rules lock methods, methods lock workflows, workflows lock economics, and economics lock incentives against transformation.

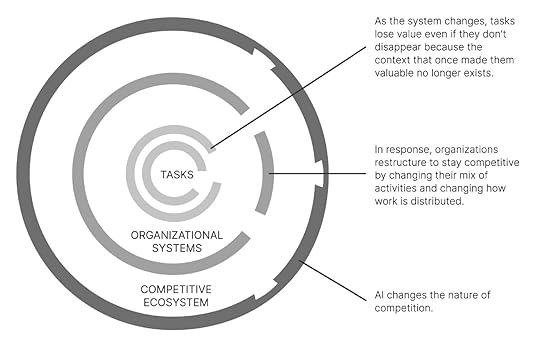

AI removes many of the constraints around which professional services workflows were built, and the moment the workflow changes, the architecture begins to reshuffle.

Dismantling constraintsAs I explain in my book Reshuffle, AI doesn’t simply automate or augment existing tasks. That dual framing is a fallacy that distracts us from the bigger shifts. AI removes the constraints that shape today’s workflows.

AI dismantles all four constraints above.

AI removes human speed as a bottleneck

Agents can analyze full datasets instantly, analyze events as they happen, and even decide and act or route decisions and actions to the appropriate stakeholders for further oversight.

AI moves analysis from documents to underlying data

Models extract entities from static documents, map relationships between those entities, and develop a detailed understanding of the domain.

AI eliminates the need for sampling and periodicity

Continuous evaluation makes annual cycles obsolete. Risk and compliance are no longer episodic or reactive, but can be managed continuously and proactively.

AI stitches fragmented data into an integrated view

This enables what I call ‘coordination without consensus’ in Reshuffle. Actors don’t need to align on standards before they start speaking the same language or start seeing a shared view of the system.

Removing these constraints has obvious effects on the nature of the workflow, but it also eventually reorients the entire industry architecture.

Non-linearity enters film-makingTo understand how a shift in constraints changes the entire industry architecture, let’s study an example where this has already played out, instead of merely speculating what might happen to professional services.

Traditionally, film editing was built around the physical limitations imposed by celluloid. ‘Film’ was literally ‘cut’. Rearranging sequences meant taping and re-taping. Mistakes were expensive, and redoing edits consumed days.

Because editing was slow, irreversible, and costly, the entire industry formed around that constraint. (I use a similar example of the impact of the word processor on the typists in Reshuffle.)

Then, non-linear editing arrived. Suddenly, cuts were reversible. Footage could be rearranged endlessly.

Films could be made faster on lower budgets. The old constraint of irreversible cuts was gone. With that, the logic of the entire system changed.

Directors no longer held unilateral power. Producers could reshuffle scenes deep into post-production. Junior editors leapfrogged veterans because software fluency mattered more than muscle memory with film. Shooting ratios exploded. Story structures changed as well because infinite rearrangement created new aesthetic possibilities.

Professional services are at a similar moment with AI today.

Law firms, audit firms, insurers, and compliance organizations operated under their own version of physical splicing: human limitations. Humans could review only so fast. Decisions had to be made sequentially. Entire industries grew around these constraints, just as film grew around celluloid.

The impact of AI is poised ot play out similar to the impact of nonlinear editing on filmmaking in the 1990s.

Reshuffling the film industrySo what exactly happened to the film industry?

First, there were the immediate, mechanical consequences. Shooting ratios exploded. Because everything can be rearranged later, directors shoot vastly more footage. Meanwhile, a cut can be reworked dozens of times in a single session.

But these mechanical shifts don’t change the industry architecture; they simply remove the constraint that shaped the craft.

Industry architecture changes once shifts in the workflow shift, where decisions are made and who sits at the new positions of power that emerge.

In movie-making, directors lose their monopoly on the cut because producers can now see and rework edits quickly.

With “fix it in post” becoming viable, production practices change as well. Actors perform with the knowledge that many imperfections can be smoothed later. Cinematographers and shooting crews change how they work as well.

The creative center of gravity moves into post-production.

With that, the role of the editor changes as mastery of software matters more than mastery of celluloid. Apprenticeships and time-based seniority lose power.

Eventually, rapid cuts, non-linear pacing, montage-heavy sequences, and complex structures become common because editors can try dozens of alternatives without cost.

Eventually, as we see with film-making, the entire industrial system changed.

Film editing is today a software discipline, built around version control. Nonlinear workflows also enable distributed editing. Post-production becomes globalized, with specialized hubs emerging - Los Angeles for direction, Vancouver for VFX, Mumbai or Manila for rotoscoping. New power centers emerge as well. VFX houses, post-production studios, and software companies like Avid and Adobe become more influential than equipment manufacturers or film labs.

Removing the physical constraint of film splicing first transformed how editors worked, then reshaped the hierarchy and economics of filmmaking, and finally produced an entirely new industry architecture built around software-driven, globally distributed workflows.

The ideas in this post are based on my book Reshuffle.

Reimagining the nature of work

Reimagining the nature of workAlongside the reshuffle in industry architecture and power structures, the very identity of the movie has changed as well.

The shift from linear to nonlinear editing changed the nature of movie-making and storytelling.

When the constraints of a craft change,

the identity of the work changes with them.

In the early 1990s, film editing was still a mechanical art. Rebuilding a sequence was painful. That friction shaped the storytelling of that era with clear continuity, long takes, linear plots, and a relatively conservative approach to structure.

Sure, you could do something more experimental, but every experiment carried a cost.

Nonlinear editing changed the underlying limitations. You could try ten versions of a scene and revert to version three if things went wrong. That elasticity opened the door to new narrative habits.

The mid-90s wave of non-linear and self-reflexive storytelling - think of films like Fight Club or, a little later, Memento - reflected directors jumping to exploit the shift in constraints. Writers and directors now operated in a world where editors could rearrange time in post-production and test strange sequencing structures without destroying ‘film’.

Nonlinear editing made it cheap to experiment with non-linear storytelling.

Fight Club landed with unusual force because nonlinear editing made its fractured narrative structure feel natural rather than jarring. The film could ricochet between timelines, identities, and hallucinations with a fluidity that analog editing could never have supported. It allowed the story’s ‘content’ - the themes of alienation, split selves, and consumer-culture dislocation - to be embodied in the very form of the film.

Fight Club’s cultural impact was, in large part, attributable to the way the narrative felt like the world it described: disordered, unstable, and stitched together from competing realities.

By the late 90s and early 2000s, editing had been further transformed by digital tools that made it feasible to juggle dozens of layers, VFX plates, and micro-cuts. The Matrix exploited this in showing bullet time, slow motion, hard cuts between planes of perception, which would have been far more cumbersome in a purely analog workflow.

A few years later, the Bourne films pushed an opposite style, where fast cutting, and micro-fragments were stitched together as editors could manage hundreds of cuts in a short sequence. The ‘shaky cam’ effect gave a sense of realism in action cinema, shaping audience expectations of how physical conflict should feel on screen.

At the same time, fully digital production pipelines enabled the resurgence of fantasy and sci-fi genres. You can see it starting with The Lord of the Rings trilogy and rolling into the 2010s with the Marvel Cinematic Universe. These were films whose storytelling relied on visual density and visual continuity across dozens of interlocking movies. An ambitious cinematic universe like the MCU depends on an editing culture comfortable working inside massive, interdependent timelines. The core creative act shifts from choosing between a handful of takes to managing an evolving mesh of assets spread over years.

Editing technology also enabled a different narrative style of telling a story that ironically felt unedited. Films like Children of Men, Birdman, and 1917 used long takes and simulated one-shot structures to create immersion and tension. Those feats depended absolutely on digital editing, with hidden transitions and stitching, but the result felt like the opposite of fast cutting.

The editor’s identity changed yet again. The task was no longer to chop scenes into pieces but to hide transitions so well that the audience forgot cuts existed at all.

Today, Netflix’s binge-watching is made possible by the same technology - the ability to manage an evolving mesh of assets across different production timelines. These storytelling styles simply wouldn’t have existed in an era of linear editing. Cliffhangers, cold opens, and cross-episode callbacks are now central tools to sustain the binge and increase ARPU. The unit of narrative shifts from the film to the season, managing attention over hours.

Feel free to share the post.

Reimagining the architectureThat’s the real point of what’s happening around us today. AI looks like automation today. But…

The future of industries isn’t just faster, cheaper, better.

It is a reshuffling of the entire architecture.

And an evolution of the identity of the core work that the industry offers.

When a new technology removes foundational constraints, it doesn’t just shave hours off the day. It makes different kinds of work thinkable, then practical, then expected.

The editor still edits but the underlying activity they perform and the universe around it have completely changed.

Once the constraint moves, the identity of the work moves. And once the identity of the work moves, the architecture of the industry follows.

October 26, 2025

The slow incumbent fallacy

We often believe that incumbents fail because they’re too slow.

It’s a convenient explanation.

It guarantees consensus theater.

Yet, it doesn’t quite explain why fast-moving incumbents fail.

The ones who do everything right by the textbook - the ones that both explore and exploit - the ones you talk about in HBS case studies.

Adobe checks all those boxes - one of the rare incumbents that made the leap to the cloud without imploding. In the early 2010s, it pulled off a full business model reboot, turning its one-time software licenses into recurring subscriptions. It rebuilt its products for continuous delivery and taught a generation of analysts to worship ARR (annual recurring revenue). By the mid-2010s, Adobe was thriving. The Creative Cloud became a case study in bold reinvention - the story of a company that understood the difference between digitizing its products and digitizing its economics.

The incumbent wasn’t slow.

If anything, the incumbent had moved fast and gotten it right.

And yet, as I write in Figma - the untold story, Adobe failed to counter Figma’s growing dominance.

Why exactly do the fast incumbents fail?

Below, I unpack 15 counterintuitive lessons on this topic, based on a podcast discussion I had with Aidan McCullen on The Innovation Show.

The ideas I cover apply every bit as well to the dilemmas that firms face today with AI adoption and covers:

Why productivity isn’t the real prize

Why expertise can become a liability

Why ‘learning AI’, while important, is not at all sufficient.

How power shifts not just between companies but inside careers, as algorithms strip away agency from some roles while new value accrues to others.

Read this as both a map of corporate disruption and a set of ideas to challenge how you think about disrupting your own career path.

Thank you to the first 100 paid subscribers supporting the newsletter over the past 6 weeks.

If you’ve found this newsletter useful, do consider supporting its operations with a subscription:

The slow incumbent fallacyThe slow incumbent fallacy is the belief that incumbents fail because they move too slowly.

Well, here’s the thing:

Incumbents often don’t fail because they move too slowly.

They fail because they move fast in the wrong direction.

The myth of slowness is comforting because it preserves the illusion of control.

It lets everyone nod along in boardrooms and MBA classrooms: just be faster, more agile, more experimental. It helps you sell Lean Startup and Agile bootcamps into organizations as some form of silver bullet.

But speed within the old frame is still the old frame.

The fallacy persists because it panders to existing hierarchies and treats failure as a matter of efficiency rather than imagination.

But architectural revolutions, like the cloud, platforms, and now AI, are not efficiency games. They are system redesign games.

There are three broad reasons incumbents love the slow incumbent fallacy, particularly when it’s sold to them in the form of workshops with a lot of post-its stuck to ‘innovation room’ walls.

Architectural change is harder to perceive than operational change

Operational change shows up on dashboards and KPIs. Architectural change is not quite as visible because it makes older metrics completely irrelevant.

Managers can see faster workflows, but not the invisible shift in the system’s underlying logic.

That invisibility makes architecture both the slowest-moving variable and the most dangerous to ignore.

Execution bias amplifies path depandance

Speed is good if you’re headed in the right direction.

But if your expertise, incentives, and infrastructure are all tuned to preserve yesterday’s logic, every process, skill, and metric reinforces the old logic and makes you progressively blinder to the new one.

Movement is misunderstood as progress

Motion is visible, quantifiable, and consensus-friendly.

It produces the illusion of progress without confronting the existential dread of redesign.

Architecture, by contrast, requires leaders to admit they don’t fully understand the game board.

Measuring motion soothes anxiety; re-architecting threatens identity.

That’s why organizations fetishize execution while avoiding the deeper work of redefining which execution matters.

Fallacy case study - Adobe vs FigmaLet’s unpack this further using the Adobe vs Figma case.

For starters, here’s the video with Aidan exploring the case:

Now digging into the ideas in here:

How architectural shifts determine incumbent fortunes

How value migration determines incumbent fortunes

The shift from execution to governance

How moving fast in the wrong is worse than not moving at all

How to reimagine your career to avoid the incumbent trap

And finally, a. diagnostic to apply this to your business or your career.

October 5, 2025

The problem with agentic AI in 2025

In the early nineteenth century, canals represented the height of industrial progress. They connected inland towns with ports, allowing coal, grain, and other bulk goods to move at far lower cost than by wagon.

For a time, canals delivered exactly what they promised: lower transportation costs and smoother flows of commerce.

Railroads, when they appeared, seemed at first like a faster version of the same idea. Yet their impact was of an entirely different order.

Like canals, railroads reduced the cost of moving goods. Far more importantly, though, they changed the entire logic of commerce.

Trains ran on fixed timetables, and as railway lines stretched across hundreds of miles, local timekeeping started to become a problem. Before railroads, every town set its clocks by the sun, which meant noon in one town could be fifteen minutes different from noon in the next. That was tolerable for canals, where barges moved slowly and deliveries were measured in days or weeks. But it made railroads unworkable.

Faster railroads resulted in a coordination failure.

To coordinate trains safely across long distances, the industry had to impose standardized time zones.

That act of forcing distant towns and cities to operate on the same clock had far-reaching economic consequences.

It meant grain in Chicago could be priced against demand in New York on the same schedule.

It allowed financial markets, shipping companies, and manufacturers to plan production and deliveries with a new degree of precision.

Canals lowered the cost of moving a barrel of flour from one city to another. But Railroads created a world where supply and demand could be matched across vast regions in real time, because the movements of goods and information could now be coordinated on a shared clock.

Canals and railroads seem similar - they are both transportation technologies. Yet, they require fundamentally different mindsets.

Canal engineers thought like cost optimizers: How do you cut the time or expense of moving goods along an existing path?

Railroad builders were forced to think like system designers: How do you align schedules, enforce standardized time-zones, and orchestrate the movements of thousands of passengers and shipments across a continent?

The railroad’s significance lay in coordination.

Those who clung to the mindset of canals missed the real value of railroads. They saw a faster way to move coal and cotton, but couldn’t have imagined the invention of national markets.

This is the classic trap when a new technology resembles the old. We instinctively draw on the mental models of the last breakthrough. The trouble is that those models smuggle in assumptions that limit the possibilities that the new tech offers.

Canal logic never yielded time zones. Only when people realized the railroad demanded that clocks in Chicago and New York strike the same minute, so that freight arrived predictably, did the system-transforming potential become clear.

When incumbents continue to apply the old frame, they capture short-term savings but miss the larger systemic transformation.

This is the problem with (much of) agentic AI in 2025.

This essay works through various ideas, including:

The problem with today’s agentic AI experts

We’ve seen the same problem before with lean manufacturing, cloud adoption, ERP, and big data

Two core failures in agentic AI implementations today

Agentic AI’s railroad moment - and what it will take to get us there

Let’s dig in!

The problem with Agentic AI expertsOn the surface, agentic systems appear to be an extension of automation tools, Many of today’s agentic AI experts came of age in the world of Robotic Process Automation (RPA), where success was measured in headcount reduced or hours saved. Their language and mental models reflect that background.

In their view, agentic AI is a more powerful tool for automating tasks.

The problem is that this interpretation is the modern equivalent of seeing railroads as faster canals.

RPA was built to optimize discrete tasks within existing structures. It delivered cost savings by replacing clerical labor at narrow points in the process.

Agentic AI, by contrast, has the potential to reimagine entire workflows, and with that, reimagine the organizational systems that need to be built around them.

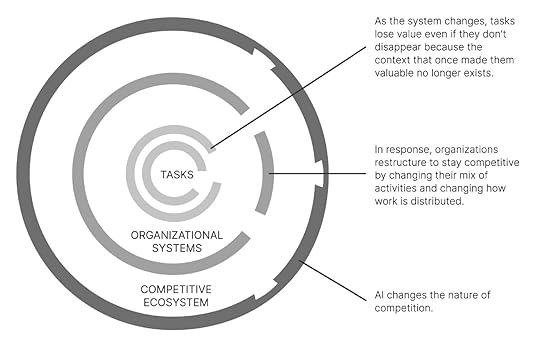

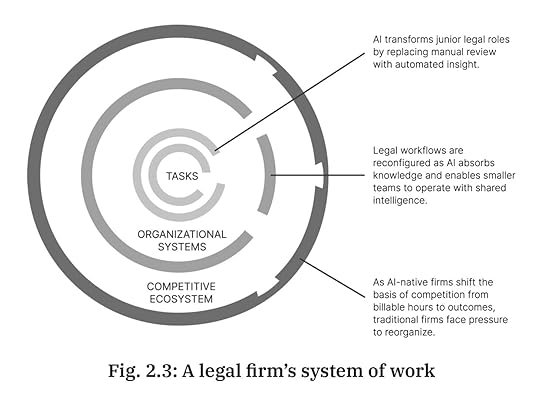

In Reshuffle, I use the system of work framework to explain these interdependencies.

When workflows change, reporting lines, incentives, compliance structures, and even the logic of competition change in response.

A bank that treats agentic AI as another round of task automation might save money on reconciliations, but a competitor that uses it to redesign end-to-end customer onboarding could collapse cycle times from weeks to minutes and reorient the economics of the industry.

The former sees automation and efficiency; the latter achieves coordination, and with it, an advantage that compounds over time.

As I explain in Reshuffle, agentic AI is not primarily a technology of efficiency but of coordination. When experts carry the RPA mindset into the agentic era, they risk misframing the opportunity.

Reshuffle continues as #1 bestseller in all categoriesNearly three months after its launch, Reshuffle remains a #1 bestseller in all its categories.

If you haven’t yet got your hands on a copy, now is a good time.

The Toyota way to agentic AIBefore we unpack the limitations of current agentic AI implementations, it is worth noting that this is not the first time an entire generation of consultants has failed to grasp the true value of an emerging technology or practice.

Lean manufacturing is one of the clearest examples of how the same set of practices can produce entirely different outcomes depending on the frame applied.

In the United States and Europe, lean was often reduced to a toolkit for cutting costs. They saw the kanban boards as scheduling devices, just-in-time as inventory reduction, kaizen as incremental productivity programs.

Consultants packaged lean as a new efficiency initiative, and executives measured its success in working capital improvements and headcount reductions.

This was great for short-term results, with less stock on factory floors, leaner balance sheets, but the systemic gains never materialized.

Instead, production became more fragile when suppliers faltered, and employees learned to view lean as a euphemism for austerity.

Toyota, by contrast, never conceived lean as an efficiency drive.

The Toyota Production System was built as a coordination architecture, one that aligned the company with its suppliers, empowered line workers to halt production when defects emerged, and created dense feedback loops so that learning could compound across the organization.

Just-in-time was less about stripping out inventory and more about reorganizing workflows across the entire supply network. Quality circles - where frontline workers regularly met to identify, analyze, and solve production problems - were a lot more than the productivity tricks that Western consultants were making of them. They were mechanisms for embedding problem-solving capacity at the edges of the system. This led to a steady rise in quality and resilience, enabling Toyota to scale globally while Western rivals wrestled with recurring defects and costly recalls.

The techniques - kanban cards and andon cords - were visible in both Japanese and Western plants. But Western managers treated lean as another canal, an efficiency program that trimmed waste. Toyota treated it as a railroad, a system that required new standards, coordination mechanisms, and governance to deliver compound benefits.

That distinction in mindset explains why the same vocabulary produced fragile savings in Detroit but an enduring advantage in Toyota City.

The limits of the traditional automation viewRPA’s origins explain why its worldview is so narrow. It was designed to automate repetitive, rules-based tasks performed by clerical workers. The technology assumed a fixed structure in the inputs and processes involved.

This history conditioned automation practitioners to identify tasks in isolation and to script deterministic logic around them, and eventually, to justify projects with short-horizon cost savings.

That orientation was well-suited to the problems RPA set out to solve, but it carries hidden constraints.

It works well with structured inputs but fails in dynamic environments. It treats exceptions as errors rather than as signals of where coordination breaks down.

Accordingly, it builds automation as one-off projects instead of as evolving systems.

These habits hold back the potential of coordination that agentic AI offers. As a result, you could employ all the right technologies and still end up stuck within yesterday’s workflows.

That’s the problem with most agentic AI implementations today.

In fact, this problem shows up in two big ways that hold back most agentic AI implementations:

Agentic AI fails when you try to automate workflows instead of eliminating or collapsing them.

Agentic AI fails when you focus entirely on workflow execution at the cost of workflow governance.

Below, we explore these two ideas in further detail.

1. Which workflows should stop existing?Let’s start with the first point.

The real potential of agentic AI is not to automate the steps of a workflow but to eliminate the workflow itself.

In talking about Reshuffle in a post that went viral on LinkedIn last week, Howard Yu makes a similar point about the book’s central message:

Workflows exist because organizations have historically needed to break down complex objectives into linear sequences of tasks performed by different roles. RPA thrived in this environment because it could pick off individual steps and automate them, but the structure of the workflow remained in place.

RPA taught practitioners to see a workflow as a string of discrete steps that could be mapped, scripted, and optimized one by one. That logic carries over when they design agents. Each agent is framed as a substitute for a task, rather than as a participant in a network of interactions.

This task-by-task orientation of RPA experts completely misses the reason agentic AI matters.

When agents can perceive context, make decisions, and negotiate with one another, the need to route work through a rigid sequence of steps no longer holds. Instead of a claims process that moves from intake to validation to adjudication in a linear chain, a network of agents can operate in parallel, gathering data, identifying anomalies, consulting policies, and resolving exceptions dynamically. The goal is no longer to make each step cheaper, but to redesign the system so that many of those steps disappear or collapse into a coordinated interaction.

This is why treating agentic AI with a task-substitution lens misses the point.

Counting hours saved at the task level is the wrong metric because the system advantage lies in eliminating the constraints that made workflows necessary in the first place. A well-designed agentic system can compress weeks of back-and-forth into minutes, not because some tasks were automated more efficiently, but because the structure of the work was reimagined.

In this sense, agentic AI is NOT an extension of RPA.

It is a challenge to the very logic of workflows

as the organizing principle of knowledge work.

Where RPA automated the clerks, agentic AI makes it possible to rethink why the clerks were needed at all.

It is important to acknowledge that the practitioners who came up through RPA do bring genuine strengths. They understand enterprise processes in detail. They have experience navigating change management in conservative organizations, where risk and audit concerns dominate decision-making.

But these strengths come with blind spots. Deep process knowledge is not the same as systemic vision. Comfort with task automation can make it difficult to reimagine workflows around agentic capabilities. The risk is that the very people best positioned to guide adoption of this new technology are also the ones most likely to limit its potential. Unless they evolve their perspective, the organizations they advise will see only incremental efficiency when coordination could be transformative.

Platforms, AI, and the Economics of BigTech is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

2. Moving from execution to governanceRather than automating tasks within a fixed process, agentic AI enables multiple agents to perceive context, make decisions, and interact with one another to achieve outcomes.

This brings us to the second point.

Its value does not lie in how cheaply a task can be executed but in how effectively a system of tasks can be synchronized, governed, and adapted as conditions change.

This shift from automation and efficiency to coordination is also a shift from focusing only on task execution to focusing on workflow governance.

In the world of RPA, the emphasis was on execution: how quickly a task could be completed, how many hours of manual work could be displaced, how reliably a form could be processed.

When agents are not simply automating tasks but making decisions and interacting with other agents and humans, the central question is no longer how efficiently they execute but under what rules, policies, and standards they coordinate.

Governance becomes the key determiner of a successful agentic AI implementation. It defines:

what goals agents pursue,

how much autonomy they are allowed,

when they escalate exceptions, and

how accountability is assigned when outcomes diverge from expectations.

In other words, the real challenge is not teaching agents to act

but aligning their actions with organizational objectives.

With RPA, governance was an afterthought. It showed up as compliance checks at the end of the process, audit trails to satisfy regulators, oversight to make sure bots were doing what humans used to do.

This distinction is crucial.

Execution can be optimized within the boundaries of a process,

but governance sets the boundaries itself.

Poorly governed agents can amplify errors, undermine trust, or generate coordination failures that break things down in adjacent workflows even if the immediate one is managed.

Well-governed agents, by contrast, can catch problems earlier, synchronize across functions, and adapt dynamically as conditions change.

The payoff of agentic AI is not in raw execution speed,

even though that’s what agentic AI experts chase today.

The payoff is really in the quality of the governance systems

that orchestrate many agents acting together.

Instead of counting task-level savings, leaders need to ask how agentic systems are governed and how the architecture of workflows changes when decision-making is redistributed.

The organizations that understand this shift will capture the benefits of coordination; those that don’t will find they now have faster clerks but no systemic advantage to justify their expensive investments.

From canals to railroads - from execution to governanceCanals were essentially about execution. Once a waterway was dug, the task was straightforward: load goods at one end, move them slowly but steadily along, and unload them at the other. Each barge was largely independent. The system did not require different towns or operators to coordinate their schedules in any precise way. As a result, there was minimal need for governance. Execution capacity, in terms of more barges, wider locks, sturdier boats, was the main variable of performance.

Railroads, by contrast, made governance a central performance driver.

Trains traveled fast, shared tracks, and passed through dozens of towns in a single day. If every locality kept its own solar noon, then scheduling was impossible and collisions were inevitable.

The success of the railroad was based on how rules, standards, and coordination mechanisms were designed so that thousands of journeys could interlock without chaos.

Canals optimized execution within a fixed process. Railroads redefined governance so that the larger system could scale.

Agentic AI needs the same reframing today: moving beyond faster execution of isolated tasks to building the governance frameworks that allow many agents to act together coherently across a system.

The distinguishing feature of agentic AI is therefore not performance on an isolated task but the ability to reconfigure relationships across tasks, workflows, and actors. A supply chain improves not by merely speeding up data entry, but by acting as a network where agents coordinate forecasts, resolve disruptions, and optimize flows in real time.

With the RPA hat on, experts frequently frame agentic AI as a cheaper clerk rather than as an orchestrator of systems. Yet just as railroads restructured markets by demanding new forms of coordination, agentic AI will restructure organizations by requiring new ways of structuring governance, standards, and interactions.

Thanks for reading Platforms, AI, and the Economics of BigTech! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Agentic AI: A case of wrong experts with the wrong frameEvery major technological wave has gone through this cycle.

Efficiency experts dominate early, extract savings, and declare victory.

Meanwhile, a different group reimagines the technology as a system architecture and captures the real prize.

Many companies invested heavily in ERP systems in the 1990s with the narrow goal of cutting back-office costs. Walmart, instead, used the technology to rewire relationships with suppliers, integrating information flows so tightly that it could orchestrate inventory across an entire retail ecosystem. Walmart saw ERP as a coordination platform, not as an accounting tool. That choice gave it a control point in the value chain that competitors could not match.

With the rise of cloud computing, CIOs in large firms justified migrations as a way to cut capital expenditures by outsourcing servers. Startups like Netflix and Stripe saw cloud as the foundation for an entirely new system architecture: elastic, API-driven, and capable of supporting products that scaled globally.

With the rise of big data, enterprises built larger dashboards, but Amazon and TikTok built personalization engines and logistics flywheels.

In each case, the wrong experts applied the old frame, extracted incremental value, and left the systemic transformation for others to capture.

Agentic AI now sits at a similar juncture.

The choice is not between adopting the technology or ignoring it.

The choice is between treating it as a canal or as a railroad.

Efficiency experts will continue to deliver savings. But the leaders who frame agentic AI as a coordination layer, who build the standards, governance, and architectures that allow agents to orchestrate complex systems, will capture the gains from transformation.

Until the mindset shifts, we will keep digging canals in an age that demands railroads.

September 24, 2025

Reshuffle and biopolitical power

TLDR: The power of AI lies in coordination without consensus, where hidden inferences from ordinary data become tools of governance and exclusion.

September 21, 2025

Openness is a rug-pull, digital strategy is really about leakiness

This post is based on ideas from my new book Reshuffle.

The story of the Library of Alexandria is often told as an example of ancient openness, a hub where the world's knowledge was collected and shared with scholars.

But the mechanics of its growth reveal something entirely different.

Every ship that entered Alexandria’s port was required to hand over any manuscripts on board. The library’s scribes copied them, and those copies stayed in Alexandria.

What appeared as openness was, in practice, a system designed to capture knowledge that leaked through trade and travel routes. The library’s power was based on its ability to intercept and absorb information that originated elsewhere.

Systems that appear open generate value not because they give away access,

but because they create opportunities for knowledge, practices, or code

to leak out of one setting and into another.

Take yoga’s journey from India to the West. In the West, yoga is packaged as a gift of openness - an ancient practice generously offered to anyone seeking balance and well-being. Studios frame it as a kind of cultural commons, open to all who wish to participate.

Yet what gave yoga its global economic power was not its openness but the leakage of specific practices out of their original religious and cultural context.

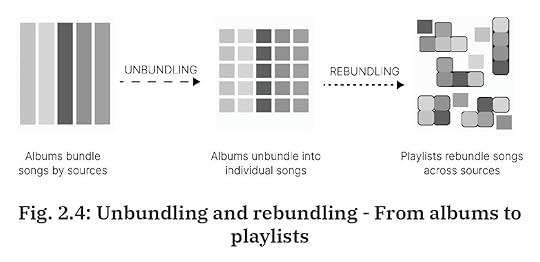

Breathing techniques, postures, even the Sanskrit names seeped into new domains, unbundled from their context, and rebundled into fitness routines, lifestyle brands, and billion-dollar studio chains.

The flows of knowledge were never fully controlled by their originators; they leaked, and others built systems to capture and commercialize them.

The organizations that thrive are those that stand at the points of leakage and have the capacity to capture, recombine, and scale what flows through.

Open source is not too different. It is often held up as the pinnacle of digital openness, where code is freely shared, modified, and redistributed.

Yet the firms that have extracted the greatest economic value are not the contributors but the cloud providers that take open-source tools, integrate them into large-scale infrastructure, and monetize them as proprietary services.

The openness of the community creates an environment where leaks of code and ideas are inevitable. The firms with the systems to absorb these leaks end up with the advantage.

Openness is a misdirection. What’s really at work is leakiness.If openness provides the appearance, leakiness supplies the mechanism.

The reason openness has become such a powerful cultural ideal in business and technology is that it works as a social signal. Declaring yourself open attracts participation, lowers resistance from users and regulators, and reassures partners that they are entering a fair system.

But the real source of durable advantage lies in how systems capture what escapes through that openness.

Leakiness is a condition where information, behavior, and value generated in one setting escape their boundaries and are absorbed elsewhere, often without the original participant’s full knowledge or control.

What matters is not whether a system is nominally open or closed, but whether it has the absorptive capacity to catch and use what leaks.

Consider Facebook’s Login API. It was presented as a convenience for developers and users: one password, access everywhere. On the surface, this looked like openness. Yet the true advantage came from the way every login generated data about user behavior across the web. That information leaked into Facebook’s ad infrastructure, strengthening its targeting engine.

Apple’s privacy posture offers a different case. The company has built its reputation on being closed to outside surveillance. Still, it allows data flows that feed its own advertising system. The signal to users is closure, but the mechanism is selective leakiness.

Stripe offers yet another angle. It does not advertise itself as open or closed. Its position at the boundary of payments means that every transaction leaks economic context to Stripe on what is sold, when, and by whom. Stripe captures and integrates that information into a broader system of financial intelligence.

In each case, the signal of openness or closure matters less than the actual underlying game of leakiness. The real economic logic is not whether you open your system to others, but whether you stand at the junctions where activity produces spillovers, and whether you can absorb them.

Leakiness transforms externalities - unintended side effects of activity - into strategic resources.

Platforms and ecosystems - business models that dominate the internet today - are really not about being open and closed but about creating the conditions for value to leak out of one context and into another.

This shift reframes competitive advantage in the digital economy.

Firms that succeed are not those that are most transparent or most closed off, but those that can spot, engineer, and capture leaks from surrounding systems and redirect them into their own.

The ‘openness’ signal may win attention, but the ‘leakiness’ condition decides who captures the value.

Not subscribed yet? What’re you waiting for?

Why leakiness mattersClassical economics has long grappled with the problem of spillovers. Knowledge generated in one firm often escapes to others; ideas spread through labor mobility, reverse engineering, or casual observation. These spillovers were traditionally seen as externalities - valuable, but difficult to capture, and often wasted.

What digital technologies have done is change the character of those spillovers.

They have made them

Observable,

Weakly excludable, and

Rapidly absorbable.

Together, those three features explain why leakiness has become the engine of advantage in digital systems.

ObservabilityIn the early industrial era, market activity was largely invisible till the railroad ticketing system came around. Suddenly, the flows of people and goods could be tracked, priced, and optimized, not just guessed at. The simple act of issuing tickets created a data trail.

Today, Stripe plays a similar role across internet activity. Every payment becomes an observable event.

Stripe might seem like a payments company but it’s really a financial intelligence layer for the internet. It captures patterns of activity - seasonality, demand cycles, geographic shifts - that would otherwise dissipate.

The observability of these traces is what makes leakiness possible. Without a trail, nothing leaks.

Weak excludabilityEven when firms attempt to wall off their data, much of it slips out through other channels.

In economics, excludability refers to whether you can prevent others from using or benefiting from a good without your permission. A good is highly excludable if you can enforce property rights around it i.e. lock it behind a fence, put a password on it, or charge a fee for access. A good is non-excludable if, once it exists, others can use it whether you like it or not, for instance, clean air or a public broadcast.

Weak excludability is the gray zone in between. It describes situations where, in theory, property rights exist, but in practice they are hard to enforce or incomplete. Information and data are classic cases. You might own the copyright to a piece of text, but once it is posted online, it is difficult to stop it from being copied, scraped, repurposed, or used to train an LLM.

Apple’s App Tracking Transparency campaign was meant to shut down the use of device identifiers by advertisers. Yet within months, marketers had shifted to other methods, like probabilistic attribution and fingerprinting, that reconstructed user behavior from the fragments that still leaked.

Browser extensions that promise coupons or shopping help to online shoppers often end up capturing vast amounts of browsing data, and leak user data into external systems.

This incompleteness of property rights is what makes leakiness possible. If firms could perfectly exclude others from using or seeing the by-products of interactions, spillovers would remain locked down. But because excludability is weak, value escapes. The organizations best positioned to capture and absorb these leaks - whether through algorithms, networks, or institutional systems - are the ones that gain advantage.

So, weak excludability in the context of property rights means that rights may be formally defined but cannot be fully enforced.

The gap between formal ownership and practical control is where leakiness occurs, and where competitive advantage in digital systems often resides.

If you’re lovin’ it so far, feel free to share this further!

Absorptive capacityAbsorptive capacity is the ability of a system to take what leaks in and turn it into a durable advantage.

During World War II, Allied intelligence would intercept radio chatter. On its own, the information was fragmented and noisy. But signals intelligence operations, from Bletchley Park to the U.S. Navy’s codebreaking units, had the organizational and computational capacity to absorb those leaks and transform them into actionable strategy.

Today, Tesla relies on its fleet of cars as an absorptive engine. Every driver correction, every braking event leaks back into the central system, strengthening the autopilot. Google’s ad system functions in much the same way: trillions of search queries become raw material for auctions that match advertisers and consumers with uncanny precision.

Observability and excludability set the conditions, but without absorptive capacity, the leaks would remain unusable.

Leakiness, then, is an economic condition that transforms incomplete property rights and observable spillovers into compounding strategic resources.

When information leaks, it flows to whoever has the absorptive capacity to catch it, structure it, and redeploy it.

This is why platforms orchestrate ecosystems, why AI systems accelerate so quickly off the back of publicly available information, and why digital moats are less about ownership than about position.

The most defensible firms are those that sit at the junctions of activity, watching what leaks through, and building the systems to turn those leaks into leverage.

Sign up for briefingsI’ve started a new series titled ‘Briefings’ which go out every week only to paid subscribers. Here’s the first one from last week:

How leakiness transforms the rules of competitionLeakiness changes competition not through the ownership of assets but through the management of flows.

Its effects play out in three important ways:

The internalization of knowledge spillovers,

The creation of new control points, and

The destabilization of complements.

Each of these can be traced back to the way firms position themselves to absorb what escapes elsewhere.

Internalization of knowledge spilloversIn most markets, spillovers are considered a public good: valuable ideas and practices diffuse outward, often benefitting rivals as much as originators.

Digital ecosystems reverse this dynamic. Firms with absorptive capacity capture the by-products of others’ activity and fold them into their own systems.

On Amazon, sellers may think of themselves as independent businesses, but every product listing, pricing experiment, and fulfillment choice leaks into Amazon’s data infrastructure. The lessons of one seller are abstracted and applied across the entire marketplace, and in some cases, appropriated directly into Amazon’s private-label offerings.

The emergence of control pointsIn the industrial economy, control came from owning bottlenecks: railroads controlled track, oil companies controlled pipelines, and manufacturers controlled plants.

In the digital economy, control is exercised less through ownership and more through placement at leaky boundaries.

Stripe does not own merchants, banks, or consumers, but by handling the flows of payments, it positions itself where valuable data leaks from one domain to another. That boundary becomes a point of leverage.

Similarly, Facebook did not need to own the web to control how people moved across it. The Login API gave it a seat at the junction where users flowed between sites without changing identity, turning an apparent convenience into a strategic chokepoint.

These control points are difficult to see from the outside because they rely on leakiness rather than control.

Destabilization of complementsPlatforms often encourage complements to flourish - developers building apps, sellers stocking shelves, curators creating playlists - because they make the ecosystem more attractive.

But complements cannot prevent the leakage of their contributions into the platform itself.

Spotify’s rise illustrates the pattern. Independent curators built followings and added value through their taste. But every skip, like, and playlist addition leaked into Spotify’s algorithms, which absorbed and automated the work of curation. In many ways, Spotify has today captured playlists as a mechanism to redirect attention rather than as a way for users to curate.

Over time, the complements were commoditized. Their insights were captured, abstracted, and built into the system, leaving them with little bargaining power.

The same story plays out in most ecosystems: complements thrive only so long as their activity continues to leak into the platform’s advantage.

Together, these outcomes explain why leakiness compounds power. Firms that capture spillovers strengthen themselves with every new participant. Firms that sit at leaky boundaries convert other people’s activity into control. And firms that absorb the contributions of complements eventually destabilize the very ecosystem they cultivated.

Competitive advantage in this environment is not about scaling production or locking down assets. It is about ensuring that what leaks flows in your direction

This post is based on ideas from my new book Reshuffle, now available in Hardcover, Paperback, Audio, and Kindle formats.

This post is based on ideas from my new book Reshuffle, now available in Hardcover, Paperback, Audio, and Kindle formats.

Leakiness and power

Leakiness and powerLeakiness can reshape entire markets, confound regulators, and shift the balance of power in ways that few participants anticipate.

For one, leakiness accelerates concentration. Once a firm has positioned itself at a leaky boundary and built the capacity to absorb what flows through, each new participant strengthens the system.

Regulation often misfires in this context. Policymakers are drawn to the visible signal of openness. They debate whether platforms should be more transparent, more interoperable, more open to competition. They talk about data residency and algorithm auditability.

But the real lever of power is not openness; it is leakiness.

Firms can appear open or closed depending on the audience they are addressing, while ensuring that the leaks flow inward. Apple’s privacy positioning is the clearest example: the signal is closure, but the structure is selective permeability. By focusing on the posture, regulators miss the logic that creates defensibility.

Leakiness distorts the relationship between contributors and orchestrators. Developers who contribute to open-source projects believe they are enriching a commons; in reality, much of their work leaks into corporate systems that monetize it at scale. Cultural practices such as yoga migrate across contexts in much the same way: they appear to be shared openly, but the long-term value accrues to those who build systems that capture what leaks and package it for new audiences.

These dynamics create a strategic paradox. Firms must leak enough to attract users, partners, and complements, but they must capture enough to sustain advantage. Too much closure and the system withers; too much openness and the system diffuses without defensibility. The art of digital strategy lies in managing this tension—engineering just enough permeability to generate activity, while ensuring that the flows of data and behavior leak in the right direction.

Leakiness, in the end, is an outcome of observability, incomplete property rights, and the capacity of systems to absorb what leaks. It explains why platforms orchestrate ecosystems and why moats today are built less by what you own and more by what leaks toward you.

That is the real source of digital power, and it is the reason the firms that appear most open often end up the most entrenched.

September 17, 2025

When supply chain power meets ecosystem power

I’m starting a new series of posts titled Briefings meant only for paid subscribers.

Every Briefing will explore one single idea.

Here’s the first one…

TLDR: Bargaining power is not about squeezing margins but about strategically preventing the capture of capabilities that anchor long-term control.

September 7, 2025

The 'data moats' fallacy

This post is based on ideas from my new book Reshuffle, now available in Hardcover, Paperback, Audio, and Kindle formats.

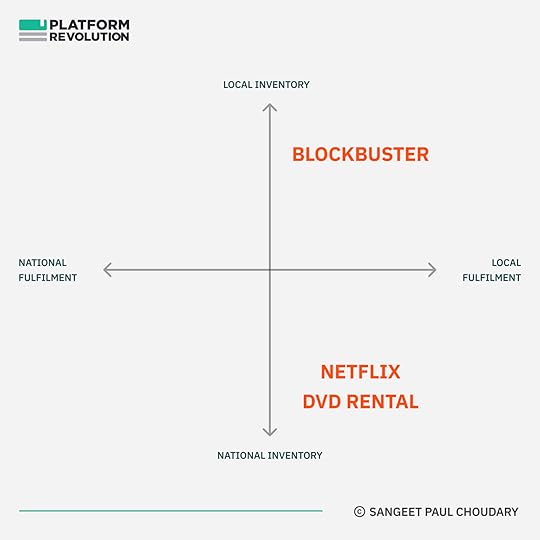

Netflix vs. Blockbuster is one of those well-worn stories that suggest quick and obvious explanations - all of which successfully miss the point.

The first misconception is that Netflix’s streaming beat Blockbuster’s DVD rental. But Netflix was way ahead way before streaming entered the picture.

If you rewind the tape a little further, another generic explanation is Netflix’s better customer experience - no more late fees, no more humiliation at the checkout counter when you returned “Titanic” three days late.

Those explanations fit the narrative we want to believe, that a plucky upstart delighted customers and the lumbering incumbent was too slow to adapt.

The trouble is, Blockbuster did adapt. Once Netflix’s no-late-fee policy started luring away customers, Blockbuster eliminated late fees too. When Netflix’s DVD-by-mail model gained steam, Blockbuster copied that as well, complete with its own red envelopes. On the surface, it matched Netflix feature for feature. Yet Blockbuster still collapsed.

Finally, the last bastion of defence: Netflix had better data, which helped it personalize recommendations for its customers.

Sounds right, you might expect.

But it’s yet another case of true, but utterly useless.

To receive new posts and access exclusive analysis, consider becoming a subscriber.

The real reason - fulfilment architectureThis post is not about Netflix vs Blockbuster but understanding why Netflix beat Blockbuster really helps us understand a larger point about where competitive advantage really lies.

In a 2020 post, Amazon is a logistics beast, I explain what really helped Netflix stand out:

The one thing that Blockbuster could never compete with was the integration of demand-side queuing data (users would add movies that they wanted to watch next into a queue) with a national-scale logistics system. All this queueing data aggregated at a national scale informed Netflix on upcoming demand for DVDs across the country.

Blockbuster could only serve users based on DVD inventory available at a local store. This resulted in:

1) low availability of some titles ( local demand > local supply), and

2) low utilization of other titles (local supply > local demand).

Netflix, on the other hand, could move DVDs to different parts of the US based on where users were queueing those titles. This resulted in higher availability while also having fewer titles idle at any point.

Queueing data improved stocking and resulted in higher utilization and higher availability. It allowed Netflix to serve local demand using national inventory.

I explain this further in Why offline retailers fail at online marketplaces:

There was no way for Blockbuster to compete with Netflix within the framework of local inventory - local fulfilment. Netflix fundamentally changed that framework.

This Netflix parable is important - it helps us identify a key factor that drives the competitiveness of companies in the age of data and AI.

Debunking the ‘data is our moat’ fallacyThe “data is our moat” fallacy is the belief that simply accumulating large amounts of proprietary data automatically creates a durable competitive advantage.

The logic goes like this: data is scarce, data is valuable, and the company that collects the most will be hardest to dislodge.

This assumption is flawed for several reasons. Data is often substitutable, its marginal utility declines rapidly in most cases, and features built on data are copyable.

Defensible advantage in data-driven businesses does not come from having data in isolation, but from the data-informed architecture a company builds.

What matters is the architecture that emerges when data is embedded in the system itself. Netflix’s queue created an entirely new operating model. Competitors could mimic features and even acquire similar datasets, but they could not easily rip out and rebuild their architecture without unraveling their existing model.

The puzzle of Netflix versus Blockbuster, in other words, was not about who had the data, but about who used it to reconfigure the logic of the business. Blockbuster never escaped the gravity of its old architecture.

In short, the fallacy is mistaking data as an asset in isolation for data-informed system design. The former is often transient; the latter, when well-architected, can produce durable advantage.

The architecture is the moatCompetitive advantage in data-driven businesses comes less from the data itself and more from the architecture that data makes possible.

In any complex system, outcomes are shaped less by individual parts than by how the parts are arranged - the feedback loops, buffers, and flows that govern behavior over time.

Data provides visibility, but it is the architecture that determines how variability is managed and how guarantees are met.

A well-designed architecture creates reinforcing loops: better forecasts reduce variance, which improves reliability, which attracts more usage, which in turn generates better data. These loops compound, widening the gap between firms that embed data into their structures and those that treat it as an add-on.

Once an architecture is built, it channels behavior in ways that are difficult to reverse. Changing it requires not just new inputs but dismantling and reassembling the system itself.

In this sense, architecture becomes the true moat. It is the pattern of interconnections, informed by data, that locks in compounding performance improvements and makes imitation prohibitively costly.

The AI-first seriesThis post is fourth as part of an ongoing series on AI-first companies.

You can see the previous posts below:

Data unlocks architectural movesData can help unlock a range of architectural moves. Four prominent ones are particularly interesting in the case of order fulfilment as with Netflix above.

1. Risk poolingWithout data, firms guess demand locally, leading to frequent stockouts in some stores and excess in others. With data, firms can forecast across a wider population, consolidate inventory, and reduce variance.

Centralizing stock reduces the safety buffer required to meet uncertain demand. Netflix did this with DVDs. Instead of guessing what each neighborhood wanted, it pooled demand nationally, shipping from a central stock based on queue data.

Amazon uses a similar principle with regionally optimized fulfillment centers, dynamically reslotted as demand signals shift.

These data-informed fulfilment architectures can promise availability with fewer assets, something a competitor tied to a local inventory model cannot easily match.

2. Demand shapingData allows companies to manage demand, not just respond to it.

Netflix’s queue was an early example. By asking customers to line up what they wanted, it smoothed out variability and gave the firm foresight into future demand.

Amazon does this through delivery-date promises; the moment a customer sees arrives Thursday, they are committing to a slot that Amazon has calculated it can meet.

In India, quick-commerce players use batching windows - “delivery in 10 minutes” versus “within 30 minutes” - to steer demand toward times and routes that make the network most efficient.

Here, the promise itself becomes the product. Competitors may have similar goods, but without a system designed to manage promises at scale, they cannot compete on reliability.

3. PostponementThe later you commit, the more accurate your decision, because uncertainty reduces as time passes. Data makes postponement feasible at scale.

Amazon leverages robotics and sortation systems that hold orders in a “ready-to-ship” state until late in the cycle, when routing decisions can be made with fresher data.

Quick-commerce firms prepare pods of popular items in dark stores, holding off on final assignment until the last minute. The architecture absorbs uncertainty by delaying commitments until predictions are more accurate.

The outcome is higher reliability without excess cost. Replicating this requires both better forecasts and physical and organizational systems designed for late-binding decisions.

4. Economies of densityPerhaps the most powerful effect of data-informed architecture is the shift from scale to density.

Traditional firms think in terms of growing volume nationally, but in last-mile systems, what matters is the number of orders per square kilometer per hour. Data allows dynamic routing and clustering so that each new order in a neighborhood reduces delivery cost and time.

Dark stores placed close to demand, riders dispatched in batched clusters, and vans leaving fuller as local demand grows - all these effects create non-linear efficiency gains. This is what makes quick-commerce viable: the system compounds as density increases.

A competitor operating on a broader but thinner footprint can grow overall volume but will never match the cost curve in dense zones without restructuring around the same principle.

If you’ve enjoyed this post, go ahead - share it!

This post is based on ideas from my new book Reshuffle, now available in Hardcover, Paperback, Audio, and Kindle formats.

Deep-dive and framework

Deep-dive and frameworkNow that we’ve covered the core idea, the rest of the post (paywalled) gets deeper into the application:

Unpack the ideas above futher by diving deeper into e-commerce and quick-commerce fulfilment architectures.

Extend the AI-first thesis that we’ve been developing across the past 3 posts.

Close with the final framework: The five tests for an architectural moat

August 31, 2025

From railroads to Roblox - Designing an AI-first economy

Reshuffle is now available in Hardcover, Paperback, Audio, and Kindle.

Traditional publishers in the gaming industry have repeatedly attempted to replicate Roblox.

They launch platforms with familiar ingredients: simplified graphics, accessible scripting tools, creator marketplaces, and virtual currencies. On paper, these efforts should work.

The incumbents control world-class studios, operate at a scale far larger than Roblox, and have the financial resources to fund creator incentives.

Yet, they fail to replicate Roblox’s success.

The challenge lies not in replicating surface features but in replicating the underlying structure.

Roblox is not just another game platform; it is built around a fundamentally different atomic unit of value.

Inverting the logic of gamingThe traditional gaming industry has been structured around the title as the unit of production and monetization.

Studios raise budgets, allocate teams, and measure returns on a title-by-title basis. Incentives throughout the system reinforce the centrality of the title.

Roblox begins from a different unit. It treats the experience block - an environment, an asset, a behavior - as the foundational building block. Blocks can be created quickly, remixed easily, and reused across many contexts.

Once the block becomes the operative unit, the entire system above it reorganizes.

Discovery shifts from promoting titles at launch to recommending flows of activity across many blocks.

Monetization shifts from unit sales to streams of microtransactions within an ongoing economy.

Identity persists across worlds rather than resetting with each new release.

Incumbents cannot simply bolt this model on because their systems assume the title as the atomic unit. Their payout structures, content policies, and discovery algorithms are written for packaged games, not for composable experiences.

Even when they copy the visible features, they remain locked into the economics of the old atom.

Unbundling the atom to create a new system

Unbundling the atom to create a new system The unbundling of the game title into experience blocks set off a cascade of effects.

First-order effects - New sources of innovationFirst, this unlocks a new source of game experience creation.

Developers assemble experiences from shared libraries, deploy them instantly, and update them continuously.

Avatars and inventories can travel across worlds, making identity portable in a way that the title-based model never allowed.

Second-order effects - New economic logicAt the second level, a market begins to form.

Different types of creators emerge: some focused on world-building, others on scripts, others on avatar skins.

Roblox introduced its virtual currency Robux to enable exchange and designed recommendation systems to optimize for overall time-in-world rather than for the success of individual titles.

The result was an economy where coordination mattered more than production.

Third-order effects - New governanceAt the third level, institutional infrastructure changes.

Roblox had to invest in trust and safety operations, enforce age bands, detect fraud, and design payout contracts that stabilized creator income.

Standards for versioning and dependency management became critical for ensuring interoperability across the building blocks.

Roblox’s economy looks less like a traditional game studio and more like a self-contained economy with its own labor force, currency, and governance.

Anyone, from a teenager in their bedroom to a micro-studio, can create and upload building blocks that plug into this economy, coordinated through a few common mechanisms:

Robux acts as the medium of exchange

Creators earn payouts based on time spent and in-game transactions

A marketplace allows buying, selling, and remixing of assets

Governance structures manage trust, safety, and age-appropriate content.

This progression explains why incumbents failed to adapt. Even if they copy the surface-level ‘features’, they are architecturally constrained unless they unbundle their atomic unit - the title - into more foundational building blocks.

Doing that would mean pulling apart their entire business and rebuilding a new one from scratch.

That is the power of an architecturally-native business model.

For more on the idea of an architecturally-native business model, read:

The incumbent architectural lock-inThe inability of incumbents to replicate Roblox lies not in their technical capability but in the lock-ins embedded in their operating model.

The first hurdle is accounting.

Incumbent accounting logic is built around titles. Their revenues, greenlight approvals, and performance metrics all assume the title as the unit of measurement.

The second hurdle is org design.

Their organizational design reinforces this, with teams structured as discrete studios producing individual games on multi-year cycles.

The third hurdle is internal product fiefdoms.

The IP regime privileges ownership and control, making it difficult to accommodate derivative rights and remix culture, and accept interoperability with less successful titles within the same studio.

The fourth hurdle is risk.

Their safety and compliance processes are modeled on batch testing before launch, not on continuous governance of a live marketplace.

The final hurdle is design.

Sunk investments into high-fidelity graphics and immersive engines may create resistance to moving to standardized, low-variance building blocks.

Each of these lock-ins is rational when the title is the atomic unit of value.

Together, they make sense of why incumbents thrived in the previous system.

But when the atom shifts, the very structures that once conferred advantage become obstacles.

To copy Roblox would require breaking these lock-ins simultaneously, which is not simply a matter of launching a new product or platform but of abandoning the entire economic logic on which the incumbent firm is built.

So the next time you hear advice about moving from a product to a platform or about building out user communities, think again about whether your atomic unit allows you that flexibility.

Subscribe here if you haven’t already

The Roblox wayRoblox’s durability comes from being architecturally native to its chosen atom.

As we noted in last week’s post, four properties define this:

The shift in the atomic unit from the title to the gaming environmental block.

The embrace of constraints as design principles. Low-fidelity graphics combined with simplified scripting act as standards that enable interoperability and scale.

The recomposition of systems around the new architecture

The reframing of competition. Roblox competes on coordination i.e. who can orchestrate the most creators, sustain the deepest engagement, and govern the most resilient economy.

We noted these properties with the shift from Adobe to Figma as well, and in explaining why Adobe - structured around the design file - is structurally incapable of replicating the success of Figma - structured around a design element as the atomic unit.

For more on the shift from Adobe to Figma, check out my interview on The Innovation Show below:

By shifting the atom, Figma embraced the constraints of the browser, rebundled collaboration workflows, and reframed competition around design workflow and governance in the enterprise.

The pattern is the same as in gaming: change the atom, adopt its constraints, rebuild the system, and redefine the axis of competition.

But there is also a difference in scope.

Figma rebundled workflows, but Roblox rebundled an entire economy around the new atomic unit.

The same structural forces play out, but in the case of Roblox, they extend beyond workflow into labor markets, currencies, and governance.

Unbundling knowledge work in the age of AIAll of this matters because AI today unbundles knoweledge work into fundamentally new atomic units. I explain this in Chapter 7 of Reshuffle:

Historically, expertise and specialized knowledge were tightly bundled with human labor - to access expertise, you had to hire, train, and manage workers. As a result, organizations paid a premium to access knowledge, and hit bottlenecks when they tried to scale it.

AI changes this. It unbundles expertise from the expert, turning knowledge into a capital asset rather than a labor input. Instead of hiring someone to perform a task, you can now rent the associated capability.

When knowledge is unbundled from human labor and becomes accessible as capital, it gains three essential traits.

It becomes rentable, as you can access it without long-term commitments.

It becomes recombinable, since different forms of expertise can be recombined without the overhead of coordinating across siloed teams.

And it becomes scalable: once a solution is built, it can be deployed repeatedly at near-zero marginal cost, unlike human labor, which scales linearly with cost.

The availability of expertise as building blocks changes productivity, but more importantly, it changes power.

Knowledge workers who once sold their labor can now package and deploy it as a building block. On the other hand, solopreneurs and creators gain leverage by combining these building blocks into new businesses.

The nature of competition also changes as a result.

Capabilities bundled with underlying assets were confined to the boundaries of a specific industry. However, as building blocks, they are now available to be leveraged across various industries. Industry boundaries don’t matter and competition, instead, plays out in connected ecosystems where these building blocks are now available across industry boundaries and success is determined not by what you own, but by how well you assemble and coordinate the building blocks that others provide.

With this unbundling and shift in the atomic unit - from the performance of knowledge work tied to skilled workers to components of knowledge work accessible on-demand - we have the opportunity to rebundle not just new workflows as Figma did, but entirely new economies as Roblox did.

Every time the atomic unit of an industry shifts,

the economy above it reshuffles.

What does it take to create a new economy? - Lessons from the rise of TV programmingIn the mid-twentieth century, the movie studio was the unquestioned center of the entertainment economy. Everything revolved around the feature film.

Studios financed production on a per-title basis, distribution schedules were structured around theatrical runs, and revenues were tallied in box office receipts.

The incentives of the system, from star contracts to marketing budgets, all assumed the feature film as the atomic unit of value.

Then television arrived, and changed the atomic unit.

The feature film gave way to the episode.

Much more importantly, the episode enabled the creation of the time slot for TV programming - an entirely new atomic unit, enabling the rise of an entirely new economy.

A film could be two hours long or three; an episode was standardized at twenty-two or forty-four minutes, carved up by advertising breaks. This constraint quickly became the basis for a new economy.