Matthew Carmona's Blog

October 16, 2025

113. Designing new towns (on the edge)

New towns?

Recently, I served on a fascinating all-day design review panel for the Chase Park and Crews Hill sites in Enfield. Just four days later – and entirely unrelated – the New Towns Taskforce, Report to Government was published, and these very sites were identified as the core of a proposed new town on the edge of London. However, while our review focused on allocations for 3,700 and 5,600 homes respectively, the conversation was now about 21,000 homes across both sites and beyond, biting off almost 900 hectares from the green belt.

Looking across the 12 potential new towns identified by the Taskforce, it’s striking how many are edge-based rather than free-standing. They broadly fall into four categories:

Free-standing new towns – Adlington, Heyford Park, TempsfordTown satellites (standalone but immediately adjacent to an existing large town) – Marlcombe, Worcestershire ParkwayUrban extensions (expanding existing limits) – Brabazon & West Innovation Arc, Crews Hill & Chase Park, (northern) Milton KeynesUrban infill (within large cities) – Leeds South Bank, Manchester Victoria North, (central) Plymouth, Thamesmead WaterfrontThis list differs markedly from the post-war new towns which were largely independent settlements, with a few town expansions such as Northampton and Peterborough. By contrast, nine of today’s 12 proposed ‘new towns’ are either enveloped by, extensions of, or sitting so close to existing urban areas that they will be dominated by their host settlements.

Are these truly new towns? I doubt they will be perceived as such when built (much like Northampton and Peterborough today), and perhaps that doesn’t matter, but in design terms it certainly adds complexity. Not only are you creating something new but also fundamentally reshaping something that exists.

Where this occurs wholly within the existing perimeter, densification can naturally create new sub-centres – Plymouth’s emerging city centre or Leeds South Bank, for example. But where growth pushes beyond the existing urban edge, the challenge is to make places that feel distinct, are appropriately dense, and remain sensitive to their edge conditions. England’s record here is poor: over half of rural-edge schemes scored “poor” or “very poor” in The Housing Design Audit for England.

Two sites on the edge

Chase Park and Crews Hill illustrate these edge conditions vividly – but in contrasting ways.

Chase Park currently exists only as countryside. The A110 defines London’s edge here, separating low-density suburban housing from open fields. From the suburban back gardens you can gaze out to green belt farmland – a quintessential urban-rural boundary. Bus routes connect to commuter rail, yet the area remains car-dependent, with generous private parking and limited walkability.

Chase Park, rolling green hills and the urban edge beyond

Chase Park, rolling green hills and the urban edge beyondCrews Hill, by contrast, already has a railway station but little resident population or intrinsic quality. Instead, it consists of a street along which are strung a succession of garden centres, nurseries and one large residential cul-de-sac (the only part that is not currently green belt). It feels suburban, despite being within the green belt – a textbook case of ‘grey belt’. Bus links are poor, the M25 roars nearby, and the place lacks any of the arcadian qualities found at Chase Park.

Crews Hill, defined by its string of garden centres

Crews Hill, defined by its string of garden centresIf these two sites form the nucleus of a larger ‘new town’, then like most of the other selections of the New Towns Taskforce, this will be a town truly on the edge; in geographic terms, a new outer suburb of London. Three critical issues follow – density, landscape, and dealing with the ‘stuff’ that is already there.

Density at the edge

The Taskforce calls for ‘ambitious density’ – enough to support walking, public transport, and vibrant neighbourhood life. It stops short of defining figures, passing that buck to government; perhaps a wise move given how different each of the sites are and the need for an ambitious but also ‘appropriate’ density for each.

So what about Chase Park and Crews Hill? 21,000 homes implies around 50,000 residents – a town the size of Durham sitting on London’s fringe. Such a population demands a full suite of services, a town centre, and strong public transport – otherwise the scheme risks becoming another car-dependent sprawl.

The ‘Goldilocks’ density – high enough to sustain amenities but low enough to retain liveability – is probably between 50–80 dwellings per hectare (on average). Interestingly, the best scoring schemes in The Housing Design Audit for England averaged 56 dwellings per hectare, so the good news is that we are much better at building at these sorts of densities.

At 50 dph, rising to perhaps 150 dph in the town centre, 21,000 homes would require about 400 hectares – less than half the 884 hectares identified. That leaves ample land for green infrastructure and biodiversity, crucial for an edge-of-town setting. Without this, we risk repeating the stark edges found in so many recent schemes, including well known projects such as Poundbury where a wall of buildings runs close to the new ring road, or less known projects such as at Loddon in Norfolk which is even worse and all too typical.

The new negative urban edge at Loddon: road, verge, fence, backs

The new negative urban edge at Loddon: road, verge, fence, backsDevelopers in such locations will certainly argue for lower-density detached housing and reduced green space, citing market demand. Yet evidence from Tackling Inequality in Housing Design Quality showed that with strategic public intervention, higher-density mixed-tenure models are viable. With 40–50% affordable housing planned across the new generation of new towns, this public role will be essential – not just to shift the dial of viability but also to secure design quality.

Landscape at the edge

Edge sites have two boundaries to design: the ‘old edge’ (between existing suburbs and the new development) and the ‘new edge’ (between new the settlement and countryside).

Residents along the old edge often resist nearby development and, if it proceeds, call for buffers and fences to ‘protect’ their neighbourhoods. This instinct must be resisted. A successful edge between old and new should be a permeable connective seam, not a barrier – connecting communities to encourage walkability and the sharing of facilities, but also to maintain access for established residents to the countryside.

The new edge, facing outward, should likewise be porous and landscape-led. Whether it proves permanent or not, it should function as a living transition – allowing movement, ecology, and views to flow. The design might be seen as the physical expression of a ‘contract’ between old, new, and future residents, setting out that change may occur, but this place will remain an intermediary between town and country in perpetuity.

The first Essex Design Guide captured this well over fifty years ago, distinguishing ‘new urban’ places (space defined by buildings) and ‘new rural’ one (space defined by landscape). Both are needed. A successful edge settlement should step from a dense urban core, through medium-density neighbourhoods, to a landscape-dominated fringe – avoiding the road-dominated, placeless sprawl that the Essex Design Guide characterised as ‘unsatisfactory suburbia’.

Derwenthorpe on the edge of York maintains a network of generous landscape connections from the countryside to the plentiful and varied green open spaces within the development

Derwenthorpe on the edge of York maintains a network of generous landscape connections from the countryside to the plentiful and varied green open spaces within the developmentStuff at the edge

Greenfield sites are never blank slates. They come with their own topography, ecology, and history – and often, a good deal of awkward ‘stuff’.

At Chase Park, remnants of an anti-aircraft battery and army encampment sit among rolling fields, hedgerows and two brooks. At Crews Hill, the stuff includes fragmented land holdings, a rich ecology of businesses, rows of pylons, the M25, and the Hertford Loop railway slicing through the site.

These features – some positive others negative – shouldn’t be ignored. Instead, they can become structuring elements – ecology parks along railways and brooks, solar arrays and vertical farms integrated into noise mitigation for motorways, the local economy assets consolidated and bolstered, and heritage features (built and natural) reinterpreted in public open space.

Of course, none of this will be easy, although the Government’s response to the Taskforce was helpful, setting out unequivocally: “We want exemplary development to be the norm, not the exception”. Achieving that will look very different in a city centre location to London’s green belt edge, or indeed the variety of other edge sites identified by the Taskforce.

We have long struggled to design positive, permeable, ecologically rich suburban schemes. Yet that is precisely what most of the Taskforce’s new towns will be: large-scale suburban extensions. To succeed, they must combine urban density with landscape richness and connection, and making the most of local assets – good and bad – already in place.

The new towns programme offers a once-in-a-generation opportunity to get suburban growth right. We should see it for what it is, and let’s hope we have the vision – and the courage – to deliver it.

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL

September 30, 2025

112. A tribute to Terry Farrell

It was with great sadness that I learned yesterday of the passing of Sir Terry Farrell. Terry was a titan of the British architectural scene. Though he often saw himself as something of an outsider, his ability to grapple with urban problems and arrive at original – often unconventional – solutions marks a life of extraordinary contribution.

I first encountered his work when I was applying to study architecture. One university (I forget which) asked me to bring along a portfolio of sketches for the interview. Lacking one, I quickly set about compiling it, and one of the buildings I sketched was the recently completed and wonderfully exuberant TV-am headquarters in Camden. At the time, I was more drawn to high-tech architecture than to postmodernism, but Farrell’s work taught me early on that architecture could be fun—something playful and imaginative, rather than the overly serious, polarised discipline it is often made out to be. My tutors, unfortunately, were less convinced.

The TV-am Building

The TV-am BuildingWhile many obituaries today rightly celebrate Terry’s architectural legacy, for me it was his impact as an urbanist that was most profound. Where others sought to solve urban challenges by reaching for another big architectural statement, Terry worked with the grain of places, discerning what they needed rather than imposing what ego – or even the client – might demand. He often said that “the place is the client,” an expression that perfectly captures his deep urban sensibility.

It was this sensibility that led me, in the early 2000s, to invite him to serve as a Visiting Professor at The Bartlett School of Planning when I was Head of School. He accepted and went on to deliver lectures for a decade, always encouraging students to shed their constraints and think differently about the problems we set them. In this role, he was an inspiration to many.

In his later years, Terry became a passionate advocate for urbanism and a tireless promoter of urban ideas. His earlier embrace of postmodernism, in retrospect, was the perfect training ground for this role. In London, Hong Kong, and elsewhere, he generated a stream of masterplans – sometimes implemented, often not, and frequently pro bono and speculative simply because he had something important to say. His proposals for the Marylebone/Euston Road corridor, the Thames Gateway, and London’s airports are all excellent examples.

Terry Farrell’s plans for Old Oak Common

Terry Farrell’s plans for Old Oak CommonThere was always something fresh and original in Terry’s plans, many of which found their way into his numerous books. As an academic, books shape much of my intellectual landscape, and his works loom large in my own personal bibliography. His brilliant Shaping London came out just as I was embarking on my own project trying to understand London’s public spaces, and I remember thinking, “Damn, Terry already has all the answers.” Later, in The City as a Tangled Bank: Urban Design Versus Urban Evolution, he argued persuasively against the ‘big plan’ and in favour of incremental change – an argument that, characteristically, challenged even the premises of his own masterplanning. It showed once again his ability to think differently, and his willingness to shed even the weight of his own past ideas.

My most direct contact with him came in the wake of the 2013 Farrell Review, which he launched with lukewarm government support to help fill the leadership gap in design quality left by CABE’s demise. The report was comprehensive and wide-ranging – parts of it I agreed with, others less so. But Terry was always generous in hearing out both supporters and dissenters. From the discussions that followed, the Place Alliance initiative was born. That initiative occupied the next decade of my life, and though Terry was never directly involved, its spark came from his report.

And so, as I sit here at Charing Cross Station – one of his designs – waiting for my train, I find myself reflecting on how much I, like many others, have to thank Terry for. He was an architectural titan who refused to be pigeonholed, and whose work was all the more meaningful and impactful as a result.

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL

July 25, 2025

111. Cold shower or warm bath? Musings on design review

This blog explores the essential nature of design review as a peer review process with a long history and a present that has seen the practice grow and grow. During this history. practices have evolved and many have moved from a top-down critique that can be likened to a cold shower, to a more supportive two-way engagement, more like a warm bath. Rather than a regulatory gateway through which projects must pass, this form of design review represents a constructive and engaging informal improvement tool, focused on adding value to developments by helping to broaden discussions as well as positively challenging the design / development team. Drawing on international examples, I argue that cold showers are sometimes good for us, but warm baths are likely to be more beneficial over the long run.

Past

As a tool of design governance, design review has a long history. As mentioned before in these blogs, the earliest evidence I have found was of the wonderfully named ‘Committee of Taste’, set up in 1802 in England. Its official name was the Committee for the Inspection of Models for National Monuments, but under the chairmanship of Charles Long (first Baron Farnborough), it quickly became known as the Committee of Taste, perhaps reflecting its membership which was described at the time as seven leading “connoisseurs and collectors of British paintings and classical antiquities”.

The committee was initially established to supervise the erection of suitable monuments to the “heroes of the Napoleonic wars”, a focus on the design and positioning of monuments that also underpinned the founding in 1910 of the Commission of Fine Arts in Washington DC, America’s first and longest surviving design review panel, and, in 1924, of the Royal Fine Arts Commission, England’s first country-wide panel. While the Committee of Taste only operated until the mid-1820s, it established the principle of a peer review process for the design of built environment projects and, in essence, that is what design review remains today.

In one form or another and under many different labels, including quality review, place review, design surgeries, aesthetic control, design advisory boards, design commissions, building committees, project meetings, quality chambers, and spatial quality teams, design review has spread around the globe. In a few countries, design review has become ubiquitous. In the Netherlands, for example, design review has been a constant presence since 1898 when municipalities were first empowered to establish ‘Aesthetic Control Committees’. Today, all 355 municipalities in the country have a committee with the formal power to prevent building permits being issued if the design is not deemed suitable.

In most countries, including Australia, the USA and the UK, design review practices followed local political choices and developed in a more haphazard and intermittent manner. In these places some locations are covered by panels and others are not. They have also tended to be more informal in nature, with a status reflected in an advisory rather than a regulatory purpose. In Europe’s German speaking countries, for example, design advisory boards developed as intermediaries between the interests of owners and the public in many larger towns and cities, including in Innsbruck. There, the design advisory board assesses the quality of projects submitted against specified criteria and offers advice to the city council which they have the discretion to follow, or not.

Typically, panels are appointed by municipalities and consist of design and other built environment professionals who conduct their work for the public sector without a charge being levied on those being reviewed. In England, however, following the 2011 demise of the influential Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE), along with its national design review panel and funding for regional offshoots, design review was opened to the market as a chargeable service. After a rocky start, this marketisation eventually led to a range of market and not-for-profit organisations offering their services to municipalities who can either employ a private provider to set up and run a dedicated panel, or can choose to set up one themselves, in-house. Many chose not to conduct or commission design review at all.

In whatever form it is conducted, processes of design review have long been the subject of criticism, notable amongst them being Brenda Case Scheer’s withering critique of American design review. She concluded that such process potentially set professionals against another, subject the work of experienced designers to demeaning scrutiny by non-designers, carry unacceptable costs, not least those associated with re-designing to ‘improve’ design outcomes or to deliver more expensive design solutions, are unduly secretive, often being conducted behind closed doors without community input, and are arbitrary and subjective in their deliberations. Likewise, the London-based national panel of CABE was widely criticised, notably for being elitist, biassed (against traditional design), overbearing, insensitive, and inconsistent in its deliberations. Others maintained that it was never nearly forceful enough in how it assessed design quality. Whatever the case, arguably it was the gradual build-up of resentment amongst professionals – particularly architects whose projects had not fared well at CABE’s design reviews – that sowed the seeds of the organisation’s eventual downfall.

Present

This might seem a curious response from a profession raised on the foundation of the architectural crit, with studios in universities around the world routinely building up and demolishing students of architecture in front of their peers (as a student I remember the fear of the crit, often following an ‘all-nighter’, all too well!). This is the very essence of what we can call a ‘cold shower’ approach to design review – a top-down, one-way shock to the system, often featuring a power-imbalance against those being reviewed.

Clearly no one likes being criticised, particularly if that is a public process, but the extent to which design review is either a fully open process (rare in my experience) or the results are openly disclosed (as CABE’s ‘letters’ were), varies significantly, along with almost every aspect of the process. Thus panels range in: i) their focus, some concentrating on specific projects and places and others on whole municipalities; ii) their administration, whether as an integral part of larger regulatory processes or separated from them; iii) their size and the range of expertise of panel members; iv) their status, including the discretion given to project promoters to appear or not; and, perhaps most importantly, v) in the degree to which the advice is taken on board by both developers and regulators.

As instruments of urban design governance, design review falls into a larger category of what I have termed ‘Rating tools’. Rating tools allow judgments to be made about the quality of design in a systematic and structured manner, usually by parties such as other professionals or community groups, that are external to, and therefore independent from, the design / development process being evaluated. They enable the public sector to systemise these judgements and make assessments about design quality in ways that are (hopefully) robust.

This can be done in two ways. First, formative evaluations, feeding into and informing the design process, and second, summative, evaluating the design quality of already fully formed development propositions. Depending on when and how it is conducted in relation to regulatory processes, design review can operate in both these ways, although evidence from London suggests that formative design review has the potential to deliver the greatest improvements in design quality as engaging earlier in the development process helps to build a local culture of design quality that empowers designers to strive for better design, and delivers a more certain, informed and confident environment for decision-making.

For John Punter, such processes have the potential to extend the remit of design review beyond a narrow regulatory function, and to thereby address some of the critiques. Panels such as those created in Auckland and Vancouver have demonstrated the potential of such an extended remit. In both cities, design review has been used to provide early and constructive advice to developers on specific development proposals; to advise their respective cities on policy and guidance frameworks; and generally to champion good design across the professional establishment and community at large. In both these cases, the link between the design review function and formal regulatory processes is less clear cut, with design review being used more as a formative critique as opposed to a summative evaluation immediately prior to the final regulatory gateway decision, as occurs in most American panels.

This informal and formative design review works by lending project teams (temporarily) but also repeatedly over the course of designing a large development project, the skills and wisdom of experienced practitioners who are able to advise on the design of specific identified development projects from their independent and dispassionate perspective. In doing so, the aim should be to constructively challenge development teams by drawing from a breadth and depth of experience that may not be available to the project team or within the municipality, including expertise in more specialist areas such as inclusion, resilience, ecology, or carbon reduction. Design review, of this type can be characterised as a ‘warm bath’ approach – a supportive, two-way engagement, featuring a constructive conversation between those reviewing and those being reviewed. Rather than a gateway through which projects pass, this form of design review is an improvement tool, focused on adding value to developments by helping to broaden discussions by positively challenging the design / development team. It may also have a gateway role, ensuring projects meet defined standards, but this, I would suggest, should not be its primary purpose.

The development of Spatial Quality Teams (Q-teams) in the Netherlands, offers an example of this more hands-on and supportive style. Q-teams build on the more reactive work of the long-established Aesthetic Control Committees to provide proactive advice about enhancing the spatial quality of buildings, streets, neighbourhoods, cities, landscapes and regions. They do not design projects, but are instead set up by local, provincial, or national authorities as multidisciplinary teams of experts to provide independent advice on large scale development areas, often advising individual projects on their contribution to the quality of the larger place and sometimes guiding the establishment of associated spatial policy frameworks. Typically, this means providing knowledge and design capacity to authorities at the early stages of a planning and design processes.

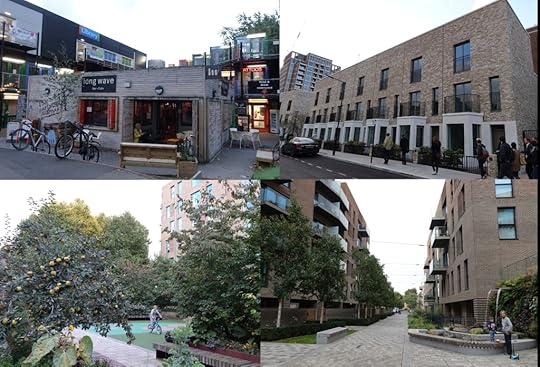

In England, many panels have learned from the downfall of CABE and have adopted the ‘warm bath’ approach. This, and the associated funding mechanism (developers now pay) means that, against early expectations, this marketisation of urban design governance has led to an increased take up of design review. And correlating the design quality of 142 housing-led development projects across the country with processes of delivery revealed that good design quality is four times more likely to be associated with the use of design review than poor quality design. In other words, the post-CABE landscape of design review has had an impact on positively shaping better design outcomes and is doing so more widely and for more developments than ever before.

There is, of course, a downside. Every panel managed externally by a private or third sector partner implies the removal of that capacity and the associated resources from the public sector and into an external consultancy. In other words, the potential to use the income from the marketisation of design review to build internal design capacity within local authorities is effectively being lost. So, instead of design review becoming the cornerstone of an enhanced public sector design capability, it is often a standalone, isolated and specialist activity, run in a fairly regimented and standardised manner, with some design review service providers running twenty or more local authority panels. One provider has even systemised their service to such a degree that bookings can be made online for anywhere in UK with panels put together on an impromptu basis, seemingly without prior connection to the place. Such practices are reminiscent of the somewhat detached national panel once operated by CABE, but whether it is a return to a full ‘cold shower’ is doubtful given the lack of gravitas enjoyed by such ad hoc arrangements.

Future

Whether the critiques of design review are accepted, or not, design review clearly leads to judgements – good or bad – about design propositions, and by implication also passes judgements on the performance of the teams responsible for them. If conduced in an unduly top-down, detached, and fleeting manner, design review can be likened to a cold shower: giving a shock to the system, perhaps with some benefits, but for most of us representing something to be endured, got through as quickly as possible and avoided wherever possible in the future. Conversely, for design review that is constructive, engaging, and part of an ongoing programme of support, the impact may be more like a warm bath, encouraging recipients to stick around and participate in a process of positive and perhaps profound change leading to real benefits under the guidance of a critical friend.

Of course some people like cold showers and eschew warm baths, and indeed sometimes it might be better to simply say “no, start again”, rather than engaging in a process of constructive engagement. There is also the question of internal resources within the public sector that will influence what is the right approach to take in different circumstances. A local authority with a well-resourced internal design team, for example, may require less input from an external panel, but will still value the final gateway review to confirm or perhaps challenge their judgement while helping to ensure that design quality remains an important and visible consideration in all development-related decision-making. A local authority without such a team will benefit from input from an external panel more regularly throughout the design / development process.

John Punter concluded an international review of design review practices by noting that “Each design review system will have its own priorities which will be strongly influenced by long-standing cultural conditions, the local politics of the development process, the perceived design failings of contemporary development, and particularly the sheer power of the market”. Whether as a formal or informal tool, design review has an important role to play in the smart governance of design, with panels not only playing a vital role in critiquing and improving design projects, but also playing important ancillary roles as mediator, facilitator, professional support group, and educator.

Critically, however, design review should always be seen as just one tool within a larger investment in the governance of design by the public sector. This should include, establishing high design aspirations, consistently seeking high standards (including, but not limited to, design review), employing appropriately skilled urban designers within the public sector to prepare proactive guidance and negotiate enhanced design outcomes, and untimely nurturing a local culture of design quality. If, conversely, design review is seen as another silo in a fragmented network of ever smaller and more specialist silos, then it is unlikely that the necessary integrated thinking will be nurtured in order to deliver long term ‘place value’.

Returning to the Committee for Taste. Interestingly, this was established by the UK Treasury, not an arm of government that in most countries (including the UK) is typically troubled by such matters. It demonstrated a concern for value beyond price that is all too rare today. As well as reviewing projects, the Committee for Taste ran competitions, exhibited designs, awarded commissions, and supervised the erection of monuments, even later branching out to supervise the repair of key public buildings. In doing so, in an early demonstration of a warm bath over a cold shower, the committee demonstrated that one tool is never enough, and that a reliance on design review will only take you so far. Then, as now, design review represents a good place to start.

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL

April 1, 2025

110. Evolving design codes, Earls Court shows the way

A confused national picture

Paragraph 138 of the National Planning Policy Framework states: “Local planning authorities should ensure that they have access to, and make appropriate use of, tools and processes for assessing and improving the design of development”. Until December last year, the sentence was followed with: “The primary means of doing so should be through the preparation and use of local design codes, in line with the National Model Design Code”. This instruction has now been dropped.

The change seems subtle given that paragraph 133 still suggests (as it did before) that “all local planning authorities should prepare design guides or codes” to “provide maximum clarity about design expectations at an early stage”. But it was also very deliberate, rowing back on the ‘requirement’ (well never quite a requirement) contained in the 2003 Levelling-up and Regeneration Act that authorities produce ‘authority-wide design codes’; doubtless as a reaction to the resource implications of their preparation.

To summarise, authorities ‘should’ prepare codes or guides, but don’t have to use them in decision-making – my head hurts!

So where does this leave us with regard to design codes? The answer is, back where we were prior to the legislation when design codes were advocated as one amongst a number of tools that authorities can use to guide their decision-making. On ‘site-specific design codes’, I think we should go further.

Coding Earls Court

The current flexible position regarding the preparation and use of design codes is further emphasised in the NPPF’s advise that the geographic scale and coverage of design codes should be a matter for local decision-making, along with responsibility for their preparation – whether local authorities or developers. This advise has been consistent since July 2021 when codes were first mentioned in the NPPF. It reflects the reality that the vast majority of design codes have been prepared at the level of individual large sites, often at the behest of local authorities but at the direction of developers seeking planning permission.

My own research, over many years, has revealed that, prepared in this way, design codes can be extremely effective tools at defining and delivering a public interest design agenda. Consequently, I was delighted to be asked to play a small role in the preparation of a code for what is one of the most significant sites in London today – the site of the long gone but not forgotten Earls Court Exhibition Centre.

Earls Court today, criss-crossed by tube and rail lines, bisected by the boundary of two Boroughs, and surrounded by varied neighbourhoods

Earls Court today, criss-crossed by tube and rail lines, bisected by the boundary of two Boroughs, and surrounded by varied neighbourhoodsThe redevelopment of Earls Court on the Zone 1/2 border, is a challenging and potentially transformative urban renewal project that has the potential to completely remould much of the Earl’s Court urban landscape and community. The project is led by the Earls Court Development Company, a Public Private Partnership between Delancy, APG and Transport for London, with the company taking ultimate responsibility for the design, development and construction of the project, and commissioning a design code to help steer this herculean endeavour.

Why a code?

During its years as an exhibition centre, Earls Court was a place of wonder, and now the Development Company aims to retain this sense of awe through its plans for the future. This, they hope, will take the form of a vibrant mixed-use community, combining residential (affordable and market), commercial, and leisure development, all set within a walkable and ecologically rich sequence of streets and public spaces. A high ambition indeed.

The vision for Earls Court from above

The vision for Earls Court from aboveSite-specific design codes are particularly effective when sites feature three characteristics. They should be:

Large-scale, Earls Court extends over18 hectares and will be built out over multiple phasesLong-term, Earls’s Court’s development is programmed over almost twenty years Complex, Earls Court will involve numerous design teams (and, if other large scale projects are anything to go by, may eventually involve different developers).Given this, and the desire to deliver something that is coherent, with all parts coordinating together to create an integrated whole, there is a need to put in place what I have referred to elsewhere as a wireframe for a place-focussed urbanism. In other words, because delivery is fragmented, there is a need for a set of consistent rules to establish a formwork on which each part, and eventually the whole neighbourhood, can grow. In the absence of a structure provided by the site itself, which at Earls Court is largely cleared, the code becomes the wireframe to support the evolving vision, in this case as reflected in the illustrative masterplan. So, what was my role?

Peer and community review

Earls Court, currently the subject of a hybrid planning application for the masterplan and phase one, was masterplanned by HawkinsBrown and Studio Egret West, who also produced the design code. Concerned that their design code should meet all the best practice expectations incorporated in the National Model Design Code, I was appointed by the Earls Court Development Company to draw together and chair an independent panel of external experts to review the code and act as a critical friend for the design / development team.

The full panel included Vicky Payne (who managed the process), Andy von Bradsky who, while at MHCLG, had been responsible for the National Model Design Code, Sue Riddlestone of BioRegional, bringing her deep sustainability knowledge to proceedings, and Noel Farrer, to bring an equally deep landscape expertise.

Our work sat alongside that of a Public Realm Inclusivity Panel, drawn from amongst the local community and made up of younger and older residents with a remit to feed in throughout the masterplanning and coding process. The Public Realm Inclusivity Panel naturally focussed on those codes that they felt were most pertinent to their aspiration for a development that serves the needs of all, including street furniture, signage, lighting, accessibility and materials. With the final design code running to 625 pages, this was a sensible strategy, but not one my panel was able to adopt given our wider brief and the need for a comprehensive analysis of all parts of the code.

While the size of the code may seem excessive (elsewhere I have argued for shorter and simpler codes), it is explained by the size and complexity of the project and the structure of the code which is divided between sitewide codes and codes for seven varied character areas within the masterplan. Our work therefore began with each panel member completing their own desk-top analysis of the sitewide codes and the three (phase one) character areas, followed by two days of structured conversation amongst the panel involving systematically working through the code to agree a set of detailed comments for the design / development team to consider.

The content of the code

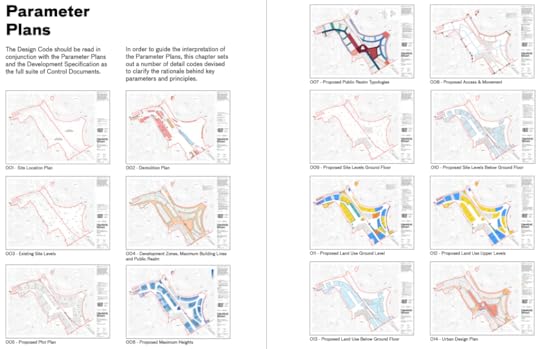

As published, the sitewide codes begin with fourteen parameter plans, dealing with everything from development zones and building lines, to building heights, land uses, access and movement, and public realm typologies. These sit alongside a separate ‘development specification’, setting out the maximum quantum of development for each development zone and its type, a design and access statement, and the illustrative masterplan (illustrative because it will inevitably need to flex over the 20 year build out).

Fourteen parameter plans

Fourteen parameter plansRather than structuring the code against the ten characteristics of well designed places (from the National Model Design Code), the document adopts a simpler and more integrated structure. Sitewide codes and the seven character area codes are instead divided between ‘Landscape’ and ‘Built environment’ codes, with each section led by the landscape as a commitment to the production of a high quality public realm.

Each code features six elements: a reference, title, textual description, rationale, cross-reference (to other codes or documents) and supporting graphics, with simple and clear diagrams underpinning almost all the codes. Expression is also carefully thought through with, in each case, an epithet: ‘must’, ‘should’ or ‘could’, highlighted in bold so that the status of each code is clear.

Looking at all this, our review found that the overall structure and approach to the design code was sound. In most part, therefore, we focused on refining the detail, giving particular attention to five key areas:

Usability & coherence: Ensuring that the wording and visual elements were crystal clear, including on use of the three status epithets and avoidance of duplication between the sitewide and character area codes.Flexibility & longevity: Focussing on the balance between control and flexibility, recommending the addition of specific metrics, greater use of cross-referencing to improve clarity, and suggesting building a review process into the code.Design quality: Providing a clearer definition of the distinctive nature of the character areas, with qualitative criteria modified to ensure the delivery of varied but also coherent design outcomes throughout. Procedural coding: Stewardship plans were recommended as part of the codes with sustainability commitments more explicitly embedded into the code through a stronger integration of environmental factors.Landscape design control: The use of stronger language on greenery and biodiversity and an acceptance of more natural (even scruffy) landscape elements as part of the mix. Example ‘landscape’ and ‘built environment’ codes

Example ‘landscape’ and ‘built environment’ codesDiscover wonder

Reflecting the vision, the tag line for the Earls Court project is ‘Discover wonder’. While one senses the sticky fingers of marketing executives on such slogans, here there is a genuine potential, not only for a sustainable new piece of London, but also for some wow factor as well. While developments often focus on the architecture to deliver the wow factor, often with ever more outlandish buildings that quickly fade in their appeal, here the wow factor will be delivered by the public realm which promises to provide this part of London a new heart and to stich the site (for the first time since it was rural fields) into its surrounding areas.

It is early days yet, and the planning application still awaits determination, but the structure of the partnership, along with the people involved, and the determination to give something back to the community, seem to have come together at Earls Court to offer the opportunity for something extraordinary. We will have to see if it delivers, but if it does, the code will be an important part of that journey; helping to clearly articulate and then (as an enforceable part of the planning approval) guarantee a set of admirable design ambitions, even for such an advantageous location.

When the National Planning Policy Framework is next revised, let’s hope the confusion over design codes can be sorted out, and, as previously advocated, that a clear statement be added that local authorities should prepare or require the preparation of design codes for large sites meeting the three characteristics listed above: large-scale, long-term and complex. Earls Court shows how.

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL

February 18, 2025

109. Tackling inequality in housing design quality 2: cross-cutting lessons for delivery

The challenge of delivering high-quality housing in economically disadvantaged areas is one of the most pressing urban issues in England today. Too often, poor housing quality is the norm, reinforcing cycles of deprivation, while new housing is either poorly designed or not delivered at all because it is unviable. However, as my previous blog showed, there are housing projects that have been able to defy the odds and deliver good quality development in some of the most challenging areas.

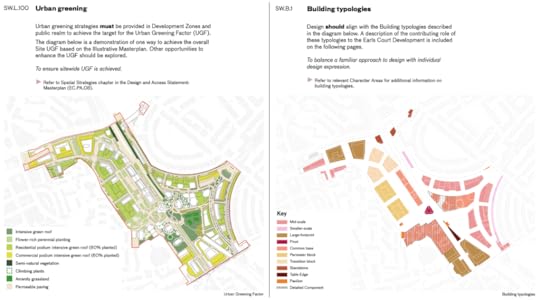

The new Place Alliance report, Tackling Inequality in Housing Design Quality, sets out ten routes to success and illustrates those with twenty stories of success. Looking across the routes and stories, certain cross-cutting lessons were also apparent that can usefully be adopted elsewhere.

The 20 projects from which the cross-cutting lessons were drawn

The 20 projects from which the cross-cutting lessons were drawnEach of the stories follows a common structure covering the journey from vision to delivery, and the key lessons are structured in the same way. They will be relevant to housing developers (public and private); design, housing, planning, real estate and highways professionals; and both local and national politicians.

The journey from vision to delivery

The journey from vision to deliveryThe Key to Success: Design Vision and Leadership

One of the primary takeaways from successful housing projects in disadvantaged communities is the importance of a clear design vision. This means prioritising key design factors such as:

A holistic approach to place-making—integrating the mix of local amenities and infrastructure necessary to create a functioning place.Optimising density—to make developments viable and liveable (the average across the 20 cases was 84 dph – the average in the UK is 31 dph).A high-quality, connected public realm—ensuring that streets, green and public spaces enhance community life.Visually appealing and robust architecture—buildings that are attractive and durable.Healthy private living spaces—with ample good quality internal and external areas for residents.Embracing adaptable standardisation—delivering economies of scale and more certain production and quality control while being responsive to context.Strong design leadership is crucial in driving such principles forward. Successful projects typically feature a collaborative leadership model, where public, private, and third-sector actors work together. Moreover, a dedicated delivery vehicle—such as public-sector housing companies or public-private partnerships—can play a critical role in ensuring a consistent and high-quality approach to housing development.

Proactive Planning: Creating a Culture of Quality

Quality housing doesn’t happen by accident. It nearly always requires proactive planning, with local authorities playing a significant role in shaping and guiding development. Key strategies include:

Building a culture of quality—where high design standards are expected because, quite simply, authorities are committed to uphold them.Setting strategic quality expectations—across all public sector plans and strategies.Providing site-specific guidance—to ensure clear, actionable expectations for developers, through pre-application engagement, design review, and design briefs and codes.Using positive planning approaches—such as CPOs and the direct public sector delivery of new housing (across tenures).Without proactive planning, disadvantaged communities risk being subjected to substandard development, where profit-driven considerations override long-term quality.

Engaging the Community: The Power of Local Voices

A common pitfall in housing development is failing to engage the community. Successful projects recognise the importance of understanding and balancing the needs of both existing residents and incoming populations. Effective community engagement means:

Understanding the needs and concerns of local residents by spending time with them and using meaningful engagement processes that genuinely influence design and planning.Balancing gentrification risks with opportunities for improvement.Encouraging long-term resident involvement in the management of housing developments.Communities thrive when residents have a stake in their environment. Housing projects that foster a sense of ownership—whether through co-design, participatory planning, or resident-led governance—are more likely to succeed in the long run.

Financing High-Quality Housing: Making It Work Economically

Many disadvantaged areas are deemed “uninvestable,” leading to a cycle where only the lowest-quality housing is developed, or none at all. But these localities are all unique socio-economic and market contexts that need to be understood and that will almost always have some place advantages that can be exploited.

To stem the race to the bottom, innovative strategies are needed, such as:

Leveraging public sector land—to offset risks in difficult locations.Densification strategies—to maximise ‘place value’ on public land.Public sector borrowing to invest—to fund long-term, high-quality developments.Cross-subsidisation—using revenue from market-rate housing to support affordable housing, or allowing cross-subsidy across different public sector schemes.Accepting that in deprived areas the answer is not always building more ‘affordable’ homes, sometimes a greater mix is required.Patient capital investments—where long-term returns are prioritised over quick profits.By understanding and shaping the economic context, it is possible to deliver high-quality housing in even the most challenging environments.

Overcoming Regulatory Barriers and monitoring delivery

Careful design and development strategies can all too easily be undermined by inappropriate regulation or crude value engineering prior to delivery. A dividend of using a public-private partnerships to deliver new housing in disadvantaged areas is the smoothing of these processes. Successful projects challenge outdated or overly rigid regulations by:

Advocating for flexible planning standards—questioning inappropriate dwelling distances and excessive parking requirements that hinder densityEngaging highways authorities early—ensuring that adoption standards support walkable, human-centric environments.Emphasizing design integrity throughout the process—by anticipating and proactively addressing cost-cutting measures that compromise quality.Monitoring and learning from past projects—ensuring that mistakes are not repeated and that successes are built upon.Tackling Inequality in Housing Design Quality, unpacks all this in more detail, systematically setting out overarching lessons for success.

Conclusion: What Are We Waiting For?

The research was clear: high-quality housing can be delivered in disadvantaged communities. The success stories prove that with strong leadership, proactive planning, community involvement, innovative financing, sensitive regulation, and delivery with integrity, it is possible to break the cycle of substandard housing.

Cross-cutting lessons for success

Cross-cutting lessons for successThe question now is, why aren’t we scaling these successes across the country?

If we are serious about tackling inequality and improving living conditions for all, then investing in better housing is not just an option—it is a necessity. The knowledge and tools exist. The only thing missing is the collective will to implement them at scale.

So, what are we waiting for?

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL

February 11, 2025

108. Tackling inequality in housing design quality 1: routes to success

As the UK grapples with a deepening housing crisis, the focus is often been on the quantity of homes we should build. However, the Labour Party’s 2024 manifesto emphasised a desire for “exemplary development to be the norm not the exception” and promised to take “steps to ensure we are building more high-quality, well-designed, and sustainable homes”.

In other words, it is not just about quantity, but also about quality, and it is not just about quality for some but quality for all.

The reality of poor-quality housing

Unfortunately, in too many disadvantaged areas, poor quality housing development is the norm. As a series of Place Alliance studies have shown, the private market works less well in such places, with lower land prices leading, proportionally, to lower investment in all aspects of the design and delivery of new homes and neighbourhoods. This happens to the point where all quality is squeezed out of private and associated affordable housing, or housebuilding simply becomes unviable.

It is perpetuated in large parts of the country by the disengagement of the public sector from housebuilding and from the proactive governance of design quality. It leads to a failure to harness the power of proactive planning to deliver anything better than standard market products and residential layouts dominated by roads.

The result, in depressed areas, is that poor quality housing development is the norm and routinely accepted by all concerned. The disadvantages that under-privileged communities already suffer are then compounded by having to live with the everyday experience of a poorly designed built environment, with long-term impacts on health and well-being.

A positive shift: learning from success stories

Despite these challenges, high-quality housing development is deliverable in disadvantaged areas. A new report from the Place Alliance highlights 20 projects from across England that have successfully delivered well-designed housing in deprived locations.

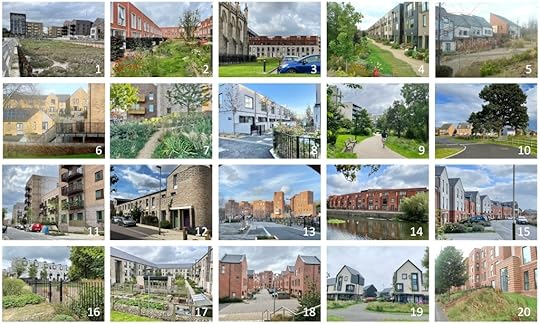

The 20 projects represented a broad range of housing tenures and typologies

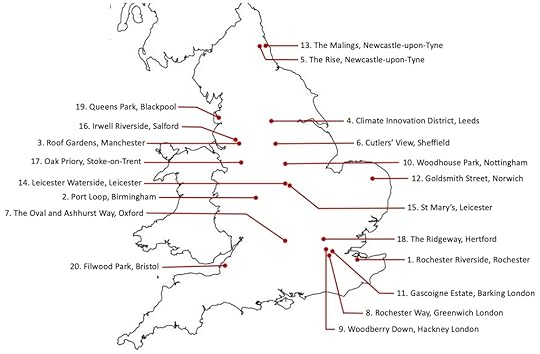

The 20 projects represented a broad range of housing tenures and typologies The projects covered every English region

The projects covered every English regionTogether the success stories revealed ten key routes to achieving high-quality housing in challenging contexts:

Route I: Creating a place and value through design

Large-scale, long-term placemaking strategies can reshape perceptions of disadvantaged areas by re-inventing the nature of places to define a completely new market. Rochester Riverside in Kent (1) and Port Loop in Birmingham (2) are two post-industrial landscapes being actively transformed into desirable new neighbourhoods, creating ‘place value’ where none previously existed.

Route II: Building a market through architectural innovation

Design excellence can drive desirability and market success, appealing to segments of the market that seek something different, including environmental pioneers. Roof Gardens in Manchester (3) and the Climate Innovation District in Leeds (4) demonstrate this and show how innovative architecture can turn marginal locations into sought-after neighbourhoods.

Route III: An entrepreneurial public sector, sharing the risk in partnership

Many successful projects emerged from strong collaborations between the public and private sectors, bringing together the high ambitions and land holdings of the public sector with the development know-how and resources of the private sector. The Rise in Newcastle-upon-Tyne (5) and Cutler’s View in Sheffield (6) were spearheaded by public-private joint ventures that combined these elements.

Route IV: Utilising under-utilised public infill plots in high value (deprived) locations

Disadvantaged areas often contain underutilised public land with the potential to host significant numbers of affordable homes and deliver other community benefits. This involves the active seeking out and bringing forward of multiple smaller publicly owned infill plots for redevelopment as seen in Oxford’s The Oval and Ashhurst Way (7) and Rochester Way in Greenwich (8). Both set new high design standards while addressing local housing needs.

Route V: Cross-subsidising affordability and design quality

Not all disadvantaged areas lack market appeal. Some, like Woodberry Down in Hackney (9) or Woodhouse Park in Nottingham (10) have inherent advantages (such as proximity to water, open space, or city centres) that can be leveraged to attract high-quality development. This route exploits that locational advantage to attract development interest without the need for risk-allaying intervention or even much (or any) public investment.

Route VI: Simply public sector vision, leadership and funding

When local authorities take a proactive approach, design quality improves significantly. Goldsmith Street in Norwich (11) and the Gascoigne Estate in Barking (12) are prime examples of public-sector-led projects that set new benchmarks for social housing design based on strong public sector leadership across all design / development stages, from inception to delivery, backed by public funding.

Route VII: Shifting the economic equation

Making high-quality housing viable in low-value areas can require public intervention designed to shift the economic equation and stimulate private investment, for example de-risking through public loans and grants, overage agreements on public land, or through regulatory exceptions and forward sales. Leicester Waterside (13) and The Malings in Newcastle-upon-Tyne (14) were of this type.

Route VIII: Economies of scale (across multiple sites)

Using standard house types doesn’t have to mean boring, repetitive architecture. Projects like St Mary’s in Leicester (15) and Irwell Riverside in Salford (16) show how adaptable on- or off-site standardisation can enhance both construction efficiency and aesthetics across multiple development sites.

Route IX: Cutting costs through continual design interrogation

Rather prosaically, the continual refinement of projects through a dual emphasis on cost and quality across the development process can deliver a focus on long-term (preferably whole life) value alongside short-term costs. At Oak Priory, Stoke on Trent (17) and The Ridgeway in Hertford (18), interrogating specifications, procurement practices and post-permissions delivery helped to avoid wasted expenditure while optimising quality within the available budget

Route X: Leveraging community ambition

In some cases, putting in place a fundamental community engagement process, either formally or informally, can help to refine critical design parameters and a defined path to success. Queens Park in Blackpool (19) and Filwood Park in Bristol (20) utilised early engagement to gain public trust, avoid resistance and ensure that the projects met the needs of both existing and new residents.

Conclusion: What Are We Waiting For?

The UK’s housing crisis is not just about numbers; it is also about the quality of homes and places we create. If the 20 success stories prove anything, it is that high-quality housing is achievable, even in the most disadvantaged areas. The ten routes to success show how.

The ten routes to success

The ten routes to successTackling Inequality in Housing Design Quality reveals definitively that while some locations are more difficult than others to develop, if the political will exists, then there are always ways and means of bucking the trend and tackling inequality head on through an investment in design quality.

So, what are we waiting for?

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL

November 15, 2024

107. National leadership on design, England’s shifting sands

This week the short lived Office for Place closed its doors less than a year after it was formally launched as an independent advisor on design in England. In a statement the Minister for Housing and Planning announced: “In taking the decision to wind up the Office for Place, the government is not downgrading the importance of good design and placemaking, or the role of design coding in improving the quality of development. Rather, by drawing expertise and responsibility back into MHCLG, I want the pursuit of good design and placemaking to be a fully integrated consideration”. Staff and key programmes of work are to be re-absorbed into the Ministry.

Office for Place R.I.P.

Office for Place R.I.P.There is a pattern here. The Royal Fine Art Commission was abolished shortly after the New Labour Government of Tony Blair came to power in the late 1990s, the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment was abolished twelve years later by the newly elected Conservative-led coalition, and now, thirteen years on, as the political pendulum swings once again, the Labour administration closes the Office for Place.

In a tight public spending environment, there is a logic to concentrating design expertise and resources in one location (back in the Ministry), rather than across two. Some argue, however, that this comes at the expense of having an independent (or at least more independent) national voice on such matters with a greater degree of latitude to manoeuvre and innovate than is possible within government. We certainly saw that in the heady days of CABE, and in other parts of the UK such organisations have proven their worth over decades, notably in Scotland and Wales. But, having tried and rejected this model in England three times, the challenge must now be to avoid further shifting of the sands and for the bolstered Ministry team to more comprehensively and forcefully take on the design quality mantle.

Under the leadership of the Chief Planner and her Head of Architecture and Urban Design, we can be confident of success. That is as long as they have access to the sustained resources and leeway required to take their work on this front to the next level.

Learning from Public Architects in Europe

This reflects the conclusion of my last blog which examined types of leadership in urban design and argued that leadership varies according to how governance and development processes give agency to those with responsibility for shaping better places. The second part of the paper that underpinned that blog was by coincidence published this week, and explores the role and leadership practices of Public Architects across Europe.

What are collectively referred to as Public Architects in the paper are in fact senior public servants and their teams charged with providing leadership relating to urban, landscape and architectural design for governments, most of whom are embedded within government departments. This is the model that in England we are now strengthening. Actual titles vary, and even though much of the work of these entities focuses on urbanistic rather than architectural issues, the most common descriptors are ‘state’, ‘principal’, ‘government’, ‘chief’ or ‘city’ architect (the nomenclature reflecting the view in Europe that urban design is a sub-set of architecture).

Our research focussed on the experiences of Ireland, Flanders, The Netherlands, Scotland, and Sweden, plus the cities of Copenhagen and Vienna. Across these cases, the specific skills and areas of responsibility of Public Architects varied dramatically from, at one end of a spectrum, a focus on the design and construction of governmental buildings, to, at the other, a focus exclusively on promotional and advisory work relating to design quality. In the former role, Public Architects are directly supported by, and head up, large technical teams, while in the latter, the role tends to be supported by smaller teams focussed on engaging with other public and private actors in order to influence their practices.

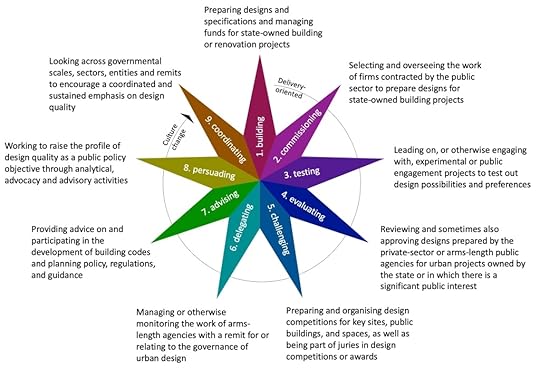

There is no space here to discuss the cases we looked at (those interested can find that in the paper), but looking across the experiences it was possible to identify nine distinct roles that Public Architects performed. These range from delivery-oriented functions utilising the harder powers of the state, to supporting a culture change by embracing tools at softer end of the power spectrum.

Nine roles of Public Architects

Nine roles of Public ArchitectsApplying lessons to England

Across Europe, investment in Public Architect roles demonstrates that governments are increasingly perceiving the value and potential of more hands-on and persuasive forms of urban design related public leadership. Today, this is widely understood to be necessary to create the right conditions under which well-designed places can more consistently emerge with all the place value that delivers.

Returning to England, national Government has tended to avoid engaging with the delivery-oriented side of design leadership processes (1-5 in the diagram above), the exception being Homes England who have an important delivery role. The Ministry has instead focused on the culture change aspects, including:

Taking responsibility for managing and monitoring its arm’s-length agencies (including, until this week, the Office for Place) (6);Developing policy, regulations and guidance associated with design quality (7); and Coordinating responses across government scales and sectors (9).The Office for Place added new capacity in this final area of responsibility and was also charged with a more outward facing persuasion role (8) focussed on convincing others about the need to deliver design quality, utilising research, advocacy and advisory means. This is something that UK government departments have historically struggled with, but which the experience of Public Architects overseas suggests is both important and deliverable and which the Ministry will now need to embrace.

So just as I wished the Office for Place great success when it was announced, so to do I now wish the new arrangements, led by the equivalent of our Public Architect – the Chief Planner, the Head of Architecture and Urban Design and their team at MHCLG, all the very best in delivering on their strengthened role of securing design quality across England. This is no small task and is one that for decades we have consistently struggled to achieve.

As well as strong political backing, Public Architects need enough resources to mobilise appropriate soft design governance tools and the long-term support across Government to deliver the culture change. This won’t be easy, it won’t be quick, and the current tight fiscal environment alongside the drive to deliver housing fast, won’t make it any easier. But it was ever thus, and we need to keep on trying, so good luck!

Matthew Carmona

Professor of Planning & Urban Design

The Bartlett School of Planning, UCL

November 12, 2024

106. Leadership in urban design (through an Indonesian lens)

This summer, a Visiting Professorship to Diponegoro University in Semarang, coincided with the publication of the first part of a new two part paper examining Urban Design Leadership. The conceptual framework provided by the latter offered a useful lens through which to reflect on the former.

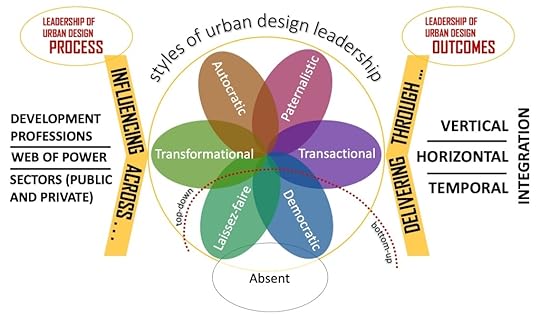

Urban design leadership conceptualised (Matthew Carmona)

Urban design leadership conceptualised (Matthew Carmona)Coordinating and integrating

In any design-based discipline, the emphasis is often on the creative act of design and what that delivers, but the act of design sits at the centre of a place-shaping process which needs to be ‘mastered’ (aka led) in a manner that directs efforts towards achieving positive outcomes, namely high-quality urbanism.

Yet given that any built environment intervention will follow a leadership process to deliver a set of outcomes, the question arises, what distinguishes urban design leadership from leadership associated with, for example, architecture, landscape or infrastructure design. Urban design has been defined in many ways – relating to the scale across which it operates, in relation to other professions, in terms of the knowledge fields from which it draws, or, most often, as a set of normative principles. Most of these substantially overlap with and can also be used to define the allied disciplines that surround urban design.

Looked at another way, it is exactly this overlap that sits at the heart of what should distinguish leadership in urban design relating to the essential integrative and coordinating nature of the discipline. Indeed, as a range of writers imply, if urban design does not focus on integrating, it is not urban design at all but instead a simpler form of artifact or project design such as a bench, a building, or a bridge.

For this reason, the initial conceptualisation of urban design leadership in the paper was framed through its fundamental joining-up function which sets it apart from other built environment disciplines and relates to both processes (the left side of the diagram and 1-3 in the box) and outcomes (the right and 4-6):

Leading across the development professions – joining-up a fragmented and often estranged set of remits through connecting fabric and processesLeading across sectors (public / private) – in a field where absolute leadership is rare and represents a negotiation across the public/private divideLeading across the web of power – utilising creative visioning to conceptualise viable urban propositions and reconcile sometimes contrasting aspirations.Leading through vertical integration – across the range of spatial scales, with different objectives, tools, and dynamics at each spatial scale Leading through horizontal integration – emphasising the importance of continuity, connection and synergy between individual urban developmentsLeading through temporal integration – accepting that places are shaped through time as part of an ongoing continuum of change that is unknownStyles of urban design leadership

Turning to the form leadership takes in urban design, six substantive styles and a seventh – its absence – are identified and fully explained in the paper, the most critical characteristic being whether they are top-down or bottom-up. None of the leadership styles (or characteristics) are absolute. Instead, they overlap and present themselves in different ways in different places at different times. That was certainly what I observed in Indonesia.

Today Indonesia is defined as a middle income country of the Global south, with a large rapidly growing economy, a stable democracy, and a young population. This has manifested itself in high population growth and strong rural/urban migration, particularly on the Island of Java where over half the county’s population is located, including the capital city Jakarta (approaching 11 million) and eight other cities (including Semarang) with a population of between one and three million. These cities combine a rich and vibrant culture with problems brought on by congestion, a lack of basic services and housing, and (in places) a deteriorating environment, all of which has dampened the prosperity gains from urbanisation.

All the forms of urban design leadership can be recognised in Indonesia’s cities:

1. Autocratic

Autocratic leadership in urban design is often the consequence of an autocratic leader taking top-down decisions about what should be where and how and might be seen as an anathema to democratic ideals. However, there are circumstances in which even representative democracies come close, notably in relation to the grand tradition of building capital cities. This was not a type of development I witnessed first-hand in Indonesia, but it did loom large in discussions in relation to the design and planning of Indonesia’s new capital city – Nusantara – on the island of Borneo. This top-down project to establish a new seat of government and home for 2 million people was instigated in 2019 at the direction of the then president and in the teeth of opposition from indigenous peoples being displaced and concerns about the impact on local wildlife. It required a constitutional amendment to ensure its delivery which is managed by the Nusantara Capital City Authority accountable directly to the President. The masterplan is based on an international design competition which defined Nusantara as ‘Indonesia’s smart and sustainable forest city’, although early phases suggests more Haussmann than holism.

2. Paternalistic

Paternalistic leadership in urban design reflects a traditional top-down approach where elected governmental organisations at different levels in the hierarchy (national to local) enact policies and propositions from the top-down in a manner that they perceive to be in the best interests of their populations. But rather than basing them on engagement with populations (beyond the democratic process), they are instead largely based on professional and political conviction. A clear example is Semarang’s old town, Kota Lama, which has been undergoing a regeneration, initially spurred by heritage loving local entrepreneurs, and latterly by the city government which has been promoting its colonial heritage as a candidate for the UNESCO world heritage list. This has involved scrubbing and ‘restoring’ the area to reveal something of its former glory, although not, unfortunately, always with a full possession of what is or isn’t authentic. Recently, for example, this has included demolishing key buildings for car parking and installing public realm features more reminiscent of Paris (again) than the former Dutch East Indies. The result seems rather sanitised when compared to the vibrant hustle and bustle typical of so many Indonesian neighbourhoods.

Kota Lama, with its Parisian style lamps, a surfeit of bollards absence of Indonesia’s typical vibrant urban life

Kota Lama, with its Parisian style lamps, a surfeit of bollards absence of Indonesia’s typical vibrant urban life3. Democratic

Modes of democratic decision-making might vary along a spectrum from decisions simply being made by elected representatives to community led processes. In the business management literature, democratic leaders focus on building a rapport so that decisions are based on a consensus that takes advantage of different skills and perspectives. Translating this to urban design, a democratic leadership approach would imply broadening out decision-making to include a wider range of stakeholders and organisations representing different development interests, and importantly, the community. I witnessed this in Tambak Lorok, a fishing village that is gradually sinking into the Java Sea, yet the community support each other to collectively plan for the settlement’s future, including trying to raise incomes through building their own fish market within the village to sell products directly to their customers. Local democracy acting through the Village Head ensures that the village is represented at higher governmental tiers and has been able to successfully capture and utilise resources to raise street levels, provide communal facilities such as public toilets, and create spaces for the community to meet and interact.

Traders outside the Tambak Lorok Fish market which has created a new economic centre for the village

Traders outside the Tambak Lorok Fish market which has created a new economic centre for the village4. Laissez-faire

Laissez-faire leadership implies a hands-off approach whereby public sector leaders largely eschew taking on a leadership role in relation to design quality and instead look to the market to define and deliver a vision. This model is common throughout the world, but in the Global south where public resources are limited, it can dominate large scale formal (as opposed to informal) urbanisation practices, with private corporations often given free rein. Naturally the market chooses to build what gives the best return and that is often exclusive gated communities that cut off wealthy residents from society at large (and all of its ills) behind high walls and security. In Jakarta, the Panti Indah Kapuk (PIK) represents a case-in-point. Developed by some of Indonesia’s largest real estate developers, it takes the form of a sequence of private gated enclaves around a sprawling roads based infrastructure and sequence of private exclusive malls and leisure facilities. According to some, PIK has been developed with scant regard to regulations or its impact on the neighbouring mangroves and communities.

A vehicle entering ‘Harmony’, one of the many exclusive suburban enclaves that make up PIK. On the other side of the road are Melody and Symphony.

A vehicle entering ‘Harmony’, one of the many exclusive suburban enclaves that make up PIK. On the other side of the road are Melody and Symphony.5. Transactional

Transactional leadership implies that leader–follower relationships are defined as a transaction. While this may characterise almost any relationship where a consultant is hired to deliver a service, some forms of urbanism and the processes that create them are notoriously formulaic, being driven by consultancies who sell similar products across nations and internationally. The urban extensions being planned around Semarang fit into this category, including Bukit Semarang Baru (BSB) City in Semarang’s south-eastern hills or the Pearl of Java (POJ) City on its north-eastern waterfront. The former is designed by the Japan based international consultancy, Nikken Sekkei, and the latter by Singapore based international consultancy, ENCITY. Both ‘products’ mix seemingly attractive environmental visions (respectively, a ‘green city’ and the ‘first seaside ecotourism destination’) with a programme of selling sprawling suburbia and the other amenities on offer. This transactional emphasis even extends to charging for entry to key amenities on offer, such as playgrounds and parks.

Paying to enter the park to walk or jog around the lake at BSB City (photography, fishing, cycling, skating, swimming, smoking and picnics are all banned)

Paying to enter the park to walk or jog around the lake at BSB City (photography, fishing, cycling, skating, swimming, smoking and picnics are all banned)6. Transformational

Urban design leadership that is transformational is often associated with inspirational leaders who are able to motivate and inspire followers to deliver positive change based on their ideas, passion, and force of argument. Equally, transformational leadership in urban design may simply involve municipalities delivering or facilitating interventions that are themselves transformational in their impact, setting a new higher benchmark for others to aspire to. The Tebet Eco Park in Jakarta is such an example, designed by SIURA Studio and delivered by the DKI Jakarta Provincial Government, the project revitalised a previously aging public park with a degraded environment, difficult accessibility, flooding problems (from an open sewer), and an association with antisocial behaviour. From this, a new heart for the surrounding communities has been forged, in which ecological diversity mixes with an inclusive human environment full of diverse recreational possibilities that have been attracting investment to the surrounding streets.

The Tebet Eco Park Infinity Link Bridge sinuously winds around and connects across the waterway and the Tebet Barat XI road that formally divided the park into two

The Tebet Eco Park Infinity Link Bridge sinuously winds around and connects across the waterway and the Tebet Barat XI road that formally divided the park into two7. Absent