Joanna Arman's Blog

March 13, 2025

Rebellion by Richard Cullen

The start of an epic new historical adventure series from Richard Cullen introducing The Black Lion

As war approaches, the lion will roar…

1213AD.

King Richard the Lionheart is dead, and his brother, John Lackland, sits uneasily upon the throne of England.

Across the sea, Prince Louis, heir to the powerful King Philip Augustus of France, looks to King John’s crown with a covetous eye.

But King John must be wary of rebellion, as well as invasion, for even his own barons would see their king unseated, and the French pretender put in his place.

Thrust amid this tumult is young Estienne Wace, orphan squire to Earl William Marshal – the greatest knight to ever serve the kings of England, and one of the few men who still holds faith in King John’s rule.

Raised by Marshal as his ward, Estienne must prove himself worthy of his adopted father’s name, but acceptance may be the least of his troubles. War is looming, as usurpers emerge from every quarter, determined to steal England’s crown from its most wretched king.

Rebellion tells the story of events in England in the 13th century from the point of view of Etienne de Wace, a young French knight in the service of William Marshal.

These events happened the last years of the reign of King John, when the Barons of England rebelled and ended up inviting Louis the dauphin of France to rule England.

This began a war lasting 2 years, in which those who adhered to the Magna Cara and where loyal to the Kings son fought to oust Louis from England. 2 years in which the future f England hung in the balance- which rebels and guerrilla fighters roamed the land.

Rebellion is an excellent fictionalized account of his time, and of the role played by the legendary Marshal and his family as well as many others. Even the indomitable Nicola de la Haye makes an appearance.

The book is detailed in its depiction of major events without bogging the reader down in unnecessary detail- and the interesting twist at the end left me wanting more. Thankfully there is already another book.

Until then, I have 1217 by Catherine Hanley to keep me going.

Thanks to Boldwooks for approving me for this title. All opinions are freely given and wholly my own

Order any of my books today from Amazon , the Publisher Website or any good retailer

My new bio of John Duke of Bedford out now

December 12, 2024

God’s Own Gentlewoman: The Life of Margaret Paston Diane Watt

The remarkable story of Margaret Paston, whose letters form the most extensive collection of personal writings by a medieval English woman.

Drawing on what is the largest archive of medieval correspondence relating to a single family in the UK, God’s Own Gentlewoman explores what everyday life was like during the turbulent decades at the height of the Wars of the Roses. From political conflicts and familial in-fighting; forbidden love affairs and clandestine marriages; bloody battles and sieges; fear of plague and sudden death; friendships and animosity; childbirth and child mortality, Margaret’s letters provide us with unparalleled insight into all aspects of life in late medieval England.

Diane Watt is a world expert on medieval women’s writing, and God’s Own Gentlewoman explores how Margaret’s personal archive provides an insight into her activities, experiences, emotions and relationships and the life of a medieval woman who was at times absorbed by the mundane and domestic, but who also found herself caught up in the most extraordinary situations and events.

This book was a fascinating biography of Margaret Paston, the 15th century matriarch of the Pason family. Much has been written on the Paston family, famous for their Letters which are windows into the lives of a Medieval gentry family. Margaret wrote many of those letters but has yet to receive a treatment of her own. Until now.

God’s Own Gentlewoman uses Margaret’s letters as a basis for sketching out her life and relationships with family members, but don’t be fooled: it is not just The Paston Letters #5. It is much more of a biography of a Medieval woman living during a period of political turbulence, war and uncertainty which very few in England escaped.

Caister Castle, Norfolk. Seat of the Pastons

Caister Castle, Norfolk. Seat of the Pastons

There’s more than just the politics though: the book recounts how women ran households and estates like businesses, defying the stereotype that women were powerless pawns. The passages detailing social and economic history were great. It is only sad that most of the places and sites related to Margaret are gone.

Discover more about Margaret and the Paston Family via Paston Footprints

My Fourth Book Henry V’s Brother is due out in January 2025 from Pen and Sword

Named after his famous grandfather, John of Gaunt, John of Lancaster Duke of Bedford, has been largely forgotten and sidelined in history. As the third of four sons, he was not his father’s heir, but he nonetheless distinguished himself in his youth in his service on the Scottish borders.

As an adult, he was overshadowed by his charismatic older brother, the warrior king and victor of Agincourt, Henry V. Yet Henry trusted John the most of all his brothers and twice left him to rule England during his expeditions in France. John Duke of Bedford was the man who really governed England for almost half of his brother’s nine-year reign.

John reached the pinnacle of his career when he was appointed Regent of France. As Regent, he governed a polity that had not existed for three centuries: a truly Anglo-Norman realm. It was not just ruled by England but populated by English settlers who lived & fought alongside the French.

For thirteen years, John held the English kingdom of France together on the negotiating table and often on the battlefield. He struggled against renegade soldiers and his adversary, Charles VII of France, but sometimes against the political machinations of his relatives to keep his late brother’s dream alive.

John became a man noted for equitable rule and an unshakeable commitment to justice. In England, people looked to him to heal the divisions which poisoned Henry VI’s government, and in France, they viewed him as the only statesman fully committed to the good governance of Normandy and Paris.

Today, John is only remembered as the man who condemned Joan of Arc, even though he was not involved. This biography provides a much-needed reassessment of John’s life and political career.

Order this or any of my other books today from Amazon , the Publisher Website or any good retailer

April 19, 2024

Two Great Reviews…..

February 25, 2024

Crusaders and Revolutionaries of the Thirteenth Century: De Montfort by Darren Baker

Preview of the Book

One of the families that dominated the thirteenth century were the de Montforts. They arose in France, in a hamlet close to Paris, and grew to prominence under the crusading fervour of that time, taking them from leadership in the Albigensian wars to lordships around the Mediterranean. They marry into the English aristocracy, join the crusade to the Holy Land, then another crusade in the south of France against the Cathars.

The controversial stewardship of Simon de Montfort (V) in that conflict is explored in depth. It is his son Simon de Montfort (VI) who is perhaps best known. His rebellion against Henry III of England ultimately establishes the first parliamentary state in Europe.

The decline of the family begins with Simon’s defeat and death at Evesham in 1265. Initially they revive their fortunes under the new king of Sicily, but they scandalise Europe with a vengeful political murder. By this time it is the twilight of the crusades era and the remaining de Montforts either perish or are expelled. Eleanor de Montfort, the last Princess of Wales, dies in childbirth and her daughter is raised as a nun.

Darren Baker’s “Crusaders and Revolutionaries of the Thirteenth Century” is a compelling family biography that traces the remarkable journey of the de Montfort dynasty, from their origins in France to their pivotal role in shaping England’s parliamentary system.

Baker’s narrative begins with the rise of the de Montfort family during the tumultuous 13th century, where they distinguished themselves as valiant Crusaders and acquired lordships across the Mediterranean. Through meticulous research, Baker dispels misconceptions and illuminates the lives of the family’s most prominent members.

There were two main branches of the family, one of which was related the Ibelins by marriage. I never knew that at all, and was delighted to learn more in this book. Now I want to research that side of the family more

The most famous members of the family were Simon de Montfort, the 5th Earl of Leicester, whose military prowess in the Albigensian Crusade propelled him to prominence and is son, also named Simon de Montfort, who left an indelible mark on history. As the 6th Earl of Leicester, he led the Second Baron’s War against King Henry III, ultimately paving the way for the establishment of Europe’s first parliamentary state.

Tragically, the family’s fortunes take a downturn following Simon’s death at the Battle of Evesham in 1265. Their reputation is tarnished by their involvement in a political murder scandal that reverberates across Europe. The decline reaches its nadir with the passing of Eleanor de Montfort, the last Princess of Wales, and the end of the family’s lineage.

Baker’s masterful storytelling vividly brings to life the triumphs and tribulations of the de Montfort dynasty, offering readers a captivating glimpse into the intricacies of medieval power dynamics and the evolution of governance. “Crusaders and Revolutionaries of the Thirteenth Century” is a poignant reminder of the enduring legacy of one of history’s most influential families and their pivotal role in shaping the course of European history.

Thanks to Pen and Sword for approving me for this title on Netgalley.

April 23, 2022

Book Review: Edward II’s Nieces, The Clare Sisters by Kathryn Warner

Pen and Sword Books, 2020, 254 Pages

Pen and Sword Books, 2020, 254 Pages The de Clare sisters Eleanor, Margaret and Elizabeth were born in the 1290s as the eldest granddaughters of King Edward I of England and his Spanish queen Eleanor of Castile, and were the daughters of the greatest nobleman in England, Gilbert the Red’ de Clare, earl of Gloucester.

They grew to adulthood during the turbulent reign of their uncle Edward II, and all three of them were married to men involved in intense, probably romantic or sexual, relationships with their uncle. When their elder brother Gilbert de Clare, earl of Gloucester, was killed during their uncle’s catastrophic defeat at the battle of Bannockburn in June 1314, the three sisters inherited and shared his vast wealth and lands in three countries, but their inheritance proved a poisoned chalice.

Eleanor and Elizabeth, and Margaret’s daughter and heir, were all abducted and forcibly married by men desperate for a share of their riches, and all three sisters were imprisoned at some point either by their uncle Edward II or his queen Isabella of France during the tumultuous decade of the 1320s.

Elizabeth was widowed for the third time at twenty-six, lived as a widow for just under forty years, and founded Clare College at the University of Cambridge.

This book was the first attempt at a full-length biography of three medieval sisters. The Clare sisters were the daughters of Joan of Acre, the famous daughter of King Edward I and Gilbert de Clare Earl of Gloucester.

Elizabeth de Clare, the youngest, has received some attention before as her surviving household accounts are a valuable historical source and because she stands out among her sisters as a woman who remained a widow for many decades and ran her own estates for some time.

Warner’s book is a great joint biography and provides a valuable resource for historians. She has drawn extensively on the available sources to trace the movements and activities of the sisters, as well as their relationships with their husbands and children. However, readers seeking an account of the everyday lives of these women, or insights into their personalities might be disappointed.

This is more of an academic work then one which would appeal to the general reader.

It is almost impossible for historians to tease out the kind of intimate details that some expect in modern biographies. We have to examine such things as the churches and charitable foundations which people gave money to, the places they visited, the things they spent money on and the places they visited.

Two of the Clare sisters were married to men who were favourites of Edward II: Hugh Despenser and Piers Gaveston. This was where I must admit to some personal divergence from the author’s opinion. I’m not entirely convinced that Edward has a sexual relationship with either man, as is commonly claimed. Just because some said he loved them, or they were close it doesn’t mean they were involved in that way. Conceptions of love have differed over the centuries, and the notion that people of the same gender who are close must inevitably be gay is largely a modern one.

Warner presents another interesting theory: that King Edward was sexually involved with not Hugh Despenser, but Eleanor his wife. Eleanor was Edward’s niece, and such an incestuous relationship could have been alluded to by contemporaries who accused the King of having “unnatural and perverted” liaisons. The author suggests this might have been the reason why Queen Isabella turned against Eleanor Despenser nee Clare so dramatically in the years following her husband’s fall from grace.

To her credit, she does not demand the reader accept her assertions as fact. They are presented as a theory, speculation. The things we are certain of are clearly distinguished from those we don’t know about with absolute certainty. That’s a good approach.

Thanks to Rosie Crofts for sending me a copy of this title when I requested it through the Marketing Programme for review. This did not influence my opinions, which are impartial and entirely my own.

April 2, 2022

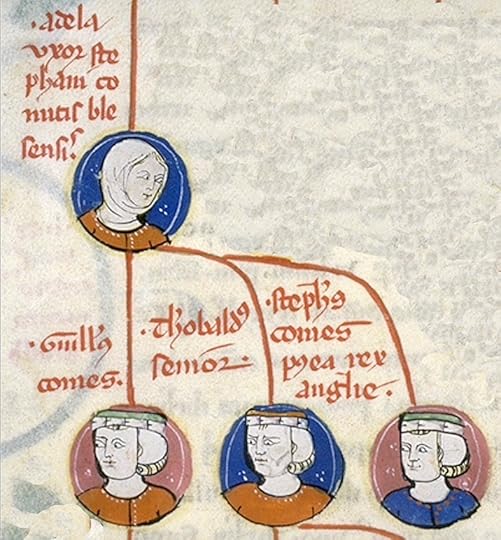

The First Cousin’s War? The Two Matildas and the Anarchy

The Wars of the Roses of the Fifteenth century is sometimes known as the “Cousin’s War” because of the relationship of the leaders. Henry VI of England was a cousin of Richard Duke of York and Edward IV, Edward was by turn a cousin of the Earl of Warwick, etc.

My second book which will be a biography of Henry VI’s Queen Margaret of Anjou, covers the Wars of the Roses, but today I’m going back to a period four centuries earlier to examine some of the key players of a period known as The Anarchy.

The Anarchy was a civil war which raged in the first half of the 12th century between Maud (or Matilda) the daughter of Henry I and Stephen, the nephew of Henry who claimed the throne when she was still living with her husband in France.

Maud and Stephen were of course first cousins, as the offspring of two children of William the Conqueror. Stephen was the son of Adela, the Conqueror’s daughter.

However, what is not widely commented upon is that Stephen’s wife, who was also named Matilda, was also the first cousin of his arch-rival Maud. Maud’s mother was Matilda of Scotland (her birth name was Edith) the daughter of St Margaret of Scotland a woman of Saxon heritage and King Malcolm III of Scotland. Stephen’s wife, Matilda of Boulogne was the daughter of Mary of Scotland, Matilda/Edith’s younger sister.

Matilda and Henry arranged Mary’s marriage to Eustace, Count of Boulogne sometime in the first decade of the 12th century. She was only a few years younger than the English Queen, and both seem to have been educated at Wilton Abbey, then lived at the royal court.

Mary herself, despite being married to the Count of Boulogne retained strong connections with England and was buried in the Benedictine Abbey which once existed in Bermondsey.

Although Maud is more famous, Matilda of Boulogne, her cousin, was actually crowned Queen of England, something Maud never managed to achieve.

Matilda also proved to be a capable leader, and even acted as a general when her husband was captured and imprisoned during the civil war, using a combination of force of arms and diplomacy to force her cousin’s hand and secure the release of Stephen.

The author of the anonymous Gesta Stephani or the “Deeds of Stephen” called Matilda “a woman of subtlety and a man’s resolution ” who “bore herself with the valour of a man” when she entered London after her entreaties to Maud to free her husband was rebuffed.

She proceeded to lay siege to the Tower of London. When her opponent retreated back to her centre of operations in Winchester, Matilda followed and laid siege to that city for two months.

Another interesting detail which reveals how Matilda was viewed by her husband and some of her contemporaries is that she was depicted on a coin alongside Stephen.

Coin showing Stephen and his wife Matilda of Boulogne

Coin showing Stephen and his wife Matilda of BoulogneBoth were shown sitting on thrones next to each other. It was extremely unusual to see women depicted on English coinage during this period, although Maud had coins struck showing herself. Her husband was a mere Count.

What we do know is that for a time, in 1142-43 an unprecedented situation existed in which a war for the throne of England was being waged between two women, both of whom were acting in the capacity as commanders.

What is most interesting about Matilda’s legacy is that whilst her cousin Maud derived her claim to the throne from her own mother’s descent from the House of Wessex and Alfred the Great, Matilda of Boulogne was of the same bloodline.

Even though her husband’s claim to the throne of England was weak and based entirely on descent from the Conqueror, her sons, William, and Eustace could boast of being direct descendants of Alfred the Great through their mother. Arguably, their claim was just as good as Maud’s. Had the events of The Anarchy transpired differently, it is possible that William or his brother might have chosen to press that claim. We could have had a King William III before the 17th century or even a King Eustace.

February 5, 2022

Reviewed: Murder During the Hundred Years War by Melissa Julian- Jones

In 1375, Sir William Cantilupe was found murdered in a field outside of a village in Lincolnshire. As the case progressed, fifteen members of his household were indicted for murder, and his armor-bearer and butler were convicted. Through the lens of this murder and its context, this book will explore violence, social norms and deviance, and crime and punishment ‘at home’ during the Hundred Years War.

The case of William Cantilupe has been of interest to historians for many years, ever since Rosamund Sillem brought it to light in her work on the Lincolnshire Peace Rolls in the 1930s, but this is the first time it has received a book-length treatment, taking relationships between the lords and their servants into account.

The verdict – guilty of petty treason – makes this one of the first cases where such a verdict was given, and this reveals the deep insecurities of England at this time, where the violent rebellion of servants against their masters (and wives against their husbands) was a serious concern, enough to warrant death by hanging (for men) and death by burning (for women). The reader is invited to consider the historical interpretations of the evidence, as the motives for the murder were never recorded.

The relationships between Sir William and his householders, and indeed with his own wife and , and whether the jury were right to convict him and his alleged accomplice in the first place.

The title of this work is a little bit deceptive. Officially its about a Medieval Murder, but it actually explores Medieval society, social and gender roles, attitudes to sex and class in the 14th century.

The murder of William Cantilupe opened up a proverbial can of worms in which everything from domestic violence to the treatment of intersex people (which William may have been) in Medieval society was laid bare.

The author doesn’t attempt to solve the mystery, but rather examine the social context in which it happened, A readable debut by this author.

Thanks to Pen and Sword for granting my request for this title.

November 19, 2021

Stephen and Matilda’s Civil War by Matthew Lewis

The Anarchy was the first civil war in post-Conquest England, enduring throughout the reign of King Stephen between 1135 and 1154. It ultimately brought about the end of the Norman dynasty and the birth of the mighty Plantagenet kings.

When Henry I died having lost his only legitimate son in a shipwreck, he had caused all of his barons to swear to recognize his daughter Matilda, widow of the Holy Roman Emperor, as his heir and remarried her to Geoffrey, Count of Anjou.

When she was slow to move to England on her father’s death, Henry’s favourite nephew Stephen of Blois rushed to have himself crowned, much as Henry himself had done on the death of his brother William Rufus. Supported by his brother Henry, Bishop of Winchester, Stephen made a promising start, but Matilda would not give up her birthright and tried to hold the English barons to their oaths.

The result was more than a decade of civil war that saw England split apart. Empress Matilda is often remembered as aloof and high-handed, Stephen as ineffective and indecisive.

By following both sides of the dispute and seeking to understand their actions and motivations, Matthew Lewis aims to reach a more rounded understanding of this crucial period of English history and asks to what extent there really was anarchy.

Stephen and Matilda's Civil War (formerly entitled Cousins of Anarchy) was an excellent and very engaging popular history of the 12th century conflict often known as 'the Anarchy'. The protagonists were two grandchildren of William the Conqueror, Matilda (AKA Empress Maud) and King Stephen. For readers who know nothing about the period, this book is an excellent choice.

It doesn't go into as much depth as some, but is more a summary of key events and figures. I appreciated the slightly more sympathetic appraisal of Stephen reign, and how the author didn't shy away from criticizing Matilda where it was due. However, I'm not that familiar with this period, and I have to confess that other material I have read by Mr Lewis has caused me to have some serious questions about his objectivity and approach.

It's ironic in a way that some of the same criticisms he levels at other historians and Victorian writers in their depiction of Stephen can also be leveled at him for his treatment of Henry VI and other key figures in 15th century Wars of the Roses. In the same way as it does Stephen "a disservice to label his reign as lawless and lacking in government" it is also a disservice to the man who established Eton an King's College Cambridge to label him as utterly useless an incompetent.

For the most part though, this was a good book, I would recommend it more as a starting point for those who seek to learn about the events of the first half of the 12th century in England.

Thanks to Pen and Sword for approving my request for this title on Netgalley. This did not influence my review, and all opinions expressed are my own.

September 18, 2020

Women of Power in Anglo-Saxon England by Annie Whitehead: Blog Tour Review

Many Anglo-Saxon kings are familiar. Æthelred the Unready is one, yet less is written of his wife, who was consort of two kings and championed one of her sons over the others, or his mother who was an anointed queen and powerful regent, but was also accused of witchcraft and regicide. A royal abbess educated five bishops and was instrumental in deciding the date of Easter; another took on the might of Canterbury and Rome and was accused by the monks of fratricide.

Anglo-Saxon women were prized for their bloodlines – one had such rich blood that it sparked a war – and one was appointed regent of a foreign country. Royal mothers wielded power; Eadgifu, wife of Edward the Elder, maintained a position of authority during the reigns of both her sons.

Æthelflaed, Lady of the Mercians, was a queen in all but name, while few have heard of Queen Seaxburh, who ruled Wessex, or Queen Cynethryth, who issued her own coinage. She, too, was accused of murder, but was also, like many of the royal women, literate and highly-educated.

From seventh-century Northumbria to eleventh-century Wessex and making extensive use of primary sources, Women of Power in Anglo-Saxon England examines the lives of individual women in a way that has often been done for the Anglo-Saxon men but not for their wives, sisters, mothers and daughters. It tells their stories: those who ruled and schemed, the peace-weavers and the warrior women, the saints and the sinners. It explores, and restores, their reputations

[image error]

Annie Whitehead’s new book brings Anglo-Saxon women to life in a vivid and readable story, simultaneously challenging certain preconceptions about Medieval women as powerless pawns and placing them in the context of their times.

The women she chooses are sometimes controversial (Emma of Normandy and murderous Mercian Queens), and some saints. Literally, others like the mother of Oswald of Northumbria are largely lost to history. By discussing their families and the connections, Whitehead helps sheds some light on even the most obscure women of the various ruling dynasties.

The author follows the logical progression of the period from the age of Saints in the 7th century, to the supremacy of Mercia in the next, and the rise of Wessex in the 9th century under the dynasty of Alfred the great, to the women of the Norman Conquest and just after. Of course, my heroine Lady Aethelflaed is not forgotten. How could she be?

Not all of the women were “powerful” in the way that we would think today, but the author shows how power could be exercised in a real and credible way in early the Early Medieval world and royal families. Being an Abbess or nun did not mean a woman was powerless, as and abbeys were often not only centres of learning but produced diplomats and politicians. The women who ran the earliest English abbeys in the 7th and 8th century “were not considered in any way inferior but revered by men and in the eyes of God.”

Even charters can reveal women taking part legal and administrative processes in their own right, and Queens who might be considered unsuccessful because their dynasties did not survive were nonetheless influential.

Whitehead does subscribe to the idea that women’s rights and power were much reduced after the Norman Conquest. A position I am not sure I entirely agree with, but her book is a valuable and very enjoyable account of the women before and on the cusp of that pivotal event.

One of the final lines sums up the subject: “ for the women of power in Anglo-Saxon England, life was neither dark, nor typically medieval. They had rights, they were able to influence events and mindsets, and although they took up little of the scribes’ time and attention, they nevertheless left their mark, enough at least for us to find them.”

Thanks to Rosie Crofts for sending me my copy of this title. I was not required to write a positive review an all opinions expressed are entirely my own.

August 10, 2020

Reviewed: Queens of the Conquest by Alison Weir

The story of England’s medieval queens is vivid and stirring, packed with tragedy, high drama and even comedy. It is a chronicle of love, murder, war and betrayal, filled with passion, intrigue and sorrow, peopled by a cast of heroines, villains, stateswomen and lovers. In the first volume of this epic new series, Alison Weir strips away centuries of romantic mythology and prejudice to reveal the lives of England’s queens in the century after the Norman Conquest.

Beginning with Matilda of Flanders, who supported William the Conqueror in his invasion of England in 1066, and culminating in the turbulent life of the Empress Maud, who claimed to be queen of England in her own right and fought a bitter war to that end, the five Norman queens emerge as hugely influential figures and fascinating characters.

Much more than a series of individual biographies, Queens of the Conquest is a seamless tale of interconnected lives and a rich portrait of English history in a time of flux. In Alison Weir’s hands these five extraordinary women reclaim their rightful roles at the centre of English history.

Alison Weir’s book is a readable and informative tour de force of the first 3 Queens of England after the Norman Conquest. Well, actually 4, as the Empress Matilda came very close to becoming England’s first ever Queen Regnant (as in a Queen reigning in her own right, instead of the wife of a King.)

Weir’s previous work tended to focus more on the Tudors and late Medieval Monarchs, but she’s done very well with this book focusing on 4 strong, interesting and intelligent women who played important rules in 11th and 12th century English history.

Incidentally, all 4 of them were also called Matilda, which can make things a little bit confusing, and makes you grateful for nicknames. First was Matilda of Flanders, the faithful and capable wife of William the Conqueror, then Matilda of Scotland, wife of Henry I. Her birth name was Edith, and the blood of the ancient Saxon Kings of Wessex ran in her veins, but she was also the daughter of St Margaret of Scotland, and Malcolm II Canmore. She unified the House of Wessex with the line of William, and was a contemporary of some of England’s greatest Medieval scholars and writers, including the philosopher Anselm of Canterbury, which whom she enjoyed a close friendship.

Some of their letters are transcribed at the end of the book, in a useful and interesting addition.

The final two women were Empress Maud, the famous daughter of Henry and Matilda, and Queen Matilda, the wife of Stephen. Empress and Queen both became involved in the brutal 12th century civil war known as The Anarchy. (I never knew that the Queen Matilda was the niece of Godfrey de Bouillon, one of the leader’s of the First Crusade who became the Crusader ruler of Jerusalem).

Weir’s exposition of the life and career of Maud is extensive and detailed, but has proved controversial for some, because she suggests that some of the contemporary allegations of arrogance and belligerence might have been true. Now, I’m not one for suggesting that everything a historian says is wrong simply because I disagree with them on one or two points, and I suspect a lot of people might have stopped reading as soon as they got to that part.

Weir is objective in her treatment of Maud, and does not take such claims at face value, but questions them and provides some alternative viewpoints and, where she does speculate, she presents it as such.

Some aspects of Maud’s career does suggest she may have been possessed of her father’s negative traits, and indeed at the time of his death, she was engaged in outright rebellion against him. There’s an annoying tendency today to assume that any criticism of a woman is ‘misogyny’ and this refers to female historical figures as well.

We tend to assume that any criticism of their character or actions was based on the ‘misogynistic’ attitudes of the time, and discount any possibility that contemporary observers may actually have had a point. I do think with Matilda, they might have done. Weir (rightly) points out that there was a double standard in terms of expectations and attitudes, but asks the reader to overcome that and look at things from the perspective of the time, and appreciate some of the evidence.

Ultimately, Empress Maud does come over in a good light, but as a woman who was, nevertheless flawed, and made some bad choices. For that, she is all the more human and relatable than some kind of perfect feminist icon to be placed on some kind of pedestal. I would recommend Queens of the Conquest for all who are interested in Women’s History and a worthy addition to the library of anyone interested in Medieval European History. It ends with the Empress Maud’s death before Eleanor of Aquitaine became Queen, so she doesn’t feature much in the book.

Thanks to Random House and Negalley for a PDF of this title. This in no way influenced my review, and all opinions expressed herein are entirely my own.