Beth Kanell's Blog

October 29, 2025

Coming Soon: Audiobook of THE BITTER AND THE SWEET -- Plus Nov. 20 Presentation

Almost all of my "spare" time for the past two weeks has been spent listening to a very skillful "audiobook" reader create the spoken version of THE BITTER AND THE SWEET, checking that the words move smoothly from the pages. It's taken a huge amount of time and has been fascinating. Kathy, the professional reader, clearly prepares for each chapter ahead of time, so that she's ready with separate voices for the different characters, and moments when someone "drops" their voice to keep quiet in a scene. She even inserts small chuckles of her own when they are laughing!

I am so excited about this, and grateful to All Things That Matter Press for investing in this version of the book. People often ask whether there are audio versions of my novels. Now I can give a resounding YES for this latest title. As soon as the version is available to order, I'll let you know ... it won't be much later, I think. (Locally, Boxcar & Caboose bookstore in St. Johnsbury and Green Mountain Books in Lyndonville are carrying all three books in the Winds of Freedom series, in softcover.)

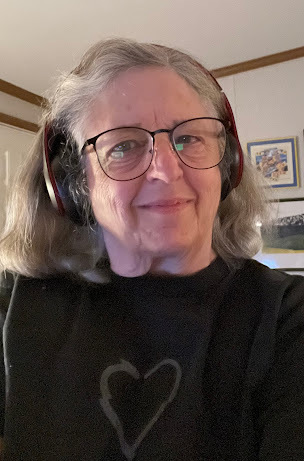

In another direction, I've learned over the years to develop an engaging public presentation, and loved the way the audience connected with my talks recently, first this summer on the 1800s immigration into Barnet, Vermont, and then in September on "The Poetry of Transitions," as an approach to my poetry book THRESHOLDS that will be published in 2026 (recording here!).

So when the St. Johnsbury Athenaeum asked me to take part in their November consideration of mysteries, of course I said yes! Here's the planned approach: the various subgenres, how mysteries are changing, the inclusion of more women and minorities as both authors and characters, and I'll provide a list of suggested authors for people to check out. Of course I'll mention THE BITTER AND THE SWEET, with a quick explanation of how I learned this region's role in counterfeiting in the 1800s. But this talk also dips deeply into the 17 years of learning the mysteries and crime fiction field with my late husband Dave Kanell, as we created Kingdom Books and traveled the United States, meeting authors and learning more.

I hope you can join me! November 20, at 7 pm, at the St. Johnsbury Athenaeum. I'll let you know if it's also recorded for viewing afterward.

October 22, 2025

Would You Change a Famous Line of Poetry?

Work room, with art in progress, year 7 of the "after."

Work room, with art in progress, year 7 of the "after."I'm walking into my seventh winter without Dave, my late husband. The pain is muted now, a low hum of missing spiced with surprising joy, as I recall the fun times we made and had.

But the transition (as you'll see in 2026 in my book Thresholds) surely colors my poetry, so I feel grateful this week to write about other things, including raking autumn leaves as a kid, and my mother's endless supply of nursery rhymes and children's songs. Good memories! These fed into a poem I'm calling "Half," and it took shape around a memory of something Mom used to chant at us when she wanted a kiss from one of her children: "Half past kissing time, time to kiss again!"

I thought she might have made it up, but it turns out to be part of a poem by Edward Field, and I found a list of his poems on Wikisource, an online compendium that I don't think I'd ever visited before. Find it here: https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Author...

Coincidentally (and in 12-Step programs we say, "Coincidence is God acting anonymously"), one of my relatives called when the poem was almost done. He told me he plans to get a poetry tattoo dedicated to his wife: "We were together. I forget the rest." (Yes, it caught me in the heart as he said it.) He said it's Walt Whitman's poetry, then added that he'd recently learned it is a paraphrase -- the original line, which I looked up as we chatted, said:

"Day by day and night by night we were together,—All else has long been forgotten by me."So, a poet's question to you readers today: Do you like the shorter version better, with that hint at modern language? (It is concise, packs a punch, and fits well on shoulder perhaps.) Or would you hold to the original? And for extra credit: Would you add a line of poetry to the landscape of your back or shoulder? Or have you done so, already ...

October 19, 2025

What If Aging Means Less Juggling? Novels, Poems, Feature Articles, History ...

I have never learned to juggle. I've watched a few people learn it, and it didn't seem terrible -- but as someone who can barely catch a basketball, grabbing smaller items out of the air isn't likely. Actually I don't throw very well, either. (Don't ask about the company baseball team, back in 1973 or so.)

Maybe you have read the "how" of juggling? I leaned on such book-learning for writing "Juggling Parenthood at Seventy," which is in the most recent issue of New Feathers Anthology - you can read it here (it's short). I was thrilled that New Feathers asked for a second poem, too, which again is set in my part of parenting "adult children." (Yes, it's here.)

With the onset of my seventies, I notice changes in how I move, which is no surprise. I'm losing some speed and coordination, but not, thank goodness, determination.

What scares me more than the physical changes are mental ones. I worry each time I can't pull up a word or remember why I was headed into another room. It seems that most of my similar-aged friends have the same worry ... none of us want to become dependent on others for basic life, and that's what those little glitches seem to threaten.

But I can't live under threat as a mood. It's terrible for writing. So I'm trying to be practical, the way I was when I got rid of the last throw rug (I loved it, but throw rugs are a Big Problem in terms of falling, "they" say.)

For writing, that means sometimes narrowing the range of what I'm working on. With the gracious collaboration of editor/publisher Justin Lavely, I'm taking a break from feature articles for The North Star Monthly for a few months at least, and I'm not rushing to write another novel. Instead, I'm making a lot of room for poems. There are scraps and Post-it notes and lists all over this home, with metaphors, bits of lines, ideas for structure. It's working! Maybe I should have tried this sooner.

Meanwhile, though, I'm watching how the novels are reaching readers. If you live in Vermont's Northeast Kingdom, you can buy a copy of The Bitter and the Sweet easily in St. Johnsbury or Lyndonville (thank you, Boxcar & Caboose, and Green Mountain Books). But you might not have heard: I was able to regain rights to the first two books in the series, The Long Shadow and This Ardent Flame, and Speaking Volumes has them back in print, with covers that match the ebooks. You can get the lovely softcovers at those same two bookstores -- and of course, order them in any other bookshop, in person or online.

There's some relief in not juggling as much: I don't worry about hard rubber balls landing on my head. But can I stick with just poetry? Umm, no. Watch for news about a huge historical research project in the wings.

October 13, 2025

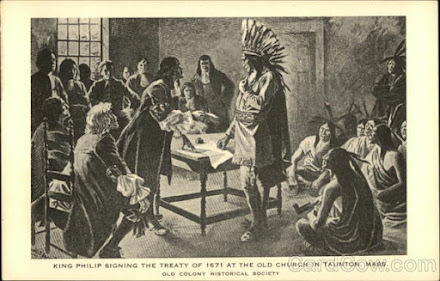

History, Historiography, and Mom: A Meditation for Indigenous Peoples' Day

Real history.

Real history.My mother wasn't a historian. She remembered her own life, of course, and some of the stories told by her relatives about earlier years. Descended on her mother's side from Quakers, who kept good records, she owned one small book written by a Quaker ancestor. Otherwise, her exploration of family history took place via letters exchanged with her cousin Alice -- who, as a professor, might have been expected to be more tuned in with the standards of history. But Alice's interest was in religion, and she too mostly provided family history via stories, letters, and some photographs, as well as her personal experience. Some of those details appear in my Winds of Freedom series of historical novels set in the 1850s in Vermont.

On my grandfather's side -- Mom's father's side -- there are better records because many of the ancestors were merchants on Cape Cod. Those folks are well documented and date back quite neatly to emigration from England on the Mayflower and other notable ships. And in England, church records allow good reliability for tracking the family tree, too.

The most fragile part of Mom's stories about the family turned out to be its connections with Native Americans. I wasn't yet asking "the right questions" at the time of Mom's death -- I was only 28 then. But I have one of her excited letters, splashed with exclamation points, suggesting that my four-greats grandmother Love Perkins in Wells, Maine, might be of Native American ancestry.

Thanks to marrying historian Dave Kanell, I've become a researcher, and I question everything in the family tree, especially connections to America's pre-1600 people. It took a lot of work, but I've demonstrated that Mom was wrong about Love Perkins. But another branch of her tree, the Hopkins line, seems to have descended in part from Wampanoag members based around Nantucket and Cape Cod. I would love to be sure about that, because it would certainly be a source of great interest. But ... the historian part of me doubts that I'll ever have enough evidence.

Still, I am thinking of Margaret Diguina today, on what has been a date recently to contemplate Indigenous peoples of our continent. If she was indeed the Wampanoag person that some records suggest, she had an amazing heritage herself. I hope that her marriage to Gabriel Weldon was both willing and happy. "Historiography," the study of the writings of history, suggests I won't get answers to my related questions during my lifetime. (Also, DNA from back then is far too diluted at this point to show up in my own genetics.)

But for the sake of a bit of history today, I recommend this article on Ruth (West) Coombs of the Mashpee Wampanoag. And for the sake of my grandsons, who may read this post some day, here's a reminder: The Wampanoag did not wear those massive feather headdresses that you see in old movies. Dig into the history of your people, and your nation, and this continent. There is so much to learn!

Real postcard but fake history and garb.

Real postcard but fake history and garb.October 8, 2025

Some Days Are Meant for Poems

I have a new routine that I call "Tuesdays are for poetry." It's a way to break the hold that "paid work" has on my schedules, and admit that I need, for all my soul, to spend enough time writing poems. Yesterday was Tuesday, and that's what I did with the time.

But even though today is Wednesday, this poem came along as I paced the wet sidewalks of a nearby town, waiting for my car to be ready at "the shop." You'll see things in this one that may become themes of many poems ahead. Thank you to this day, and to Emma, for starting this rolling.

I Remember: for Emma

When I slipped (again) to your sister’s name it was onlybecause

those memories were laid down when I was a young mother—

a time so fraught with peril that hypervigilance felt normal

(there must have been ways to stay safe)

and I hope you can forgive me (again) for what must seem

like I do not know you for who you are: But so many times

each year now, as I scan the images of who I’ve been andwhere

this aging brain is headed,

I’ve seen you again in your leather chaps, chainsaw ready,

your confidence on a mountaintop and the carefully blank

gaze you gave to some demanding young man, bare chested,

muscles rippling,

who practically dragged the saw out of your hands, started

showing off with the fallen trees. There were reasons we had

for not shouting at him. I remember those, too. And themoment

I pulled my supervising motif

up from my boots, interrupted him, said “I am paying thiswoman

to do this job, give the saw back. Now.” Plus your calmpatience

guarding the lake (its wide waters ample as a woman’s hips)from

invasion at the boat dock. See?

Now every morning through an Alice-in-Wonderland view

I marvel at your blossoms, herbs, eggs, invitations tostrangers

as well as friends, the way you share your journey inbiscuit-

sized morsels, feeding the world.

You will understand, on this cold and rainy Wednesday, how

my mind goes to biscuits, and lighting the oven, making magic

with flour and cream: Baking may become my enduring skill

as bits of thought crumble behind me

trails laid out for grandchildren to follow if they arequick

because there are always crows ready to sample what’s left

behind. Crows recognize faces. The ones around me call out

when I pass, walking briskly,

trying anything and everything that may maintain my mind.

Aging comes with funhouse mirrors, thickening the waist,

creasing the face, tugging at eyelids that never will goback

a quarter century and more.

I am willing to give up youth and nimble knees. To wake

repeatedly each night, rolling the seized-up shoulder muscle

easing the hip, taking care not to think in the darkness

(because it triggers insomnia)

and then to meet the stranger reflected in the bakery window,

telling her she looks seasoned, capable. I talk to the crows. Oneday,

I may not notice when I mouth the wrong name. But today

is not that day. I do remember, Emma.

BK 10-8-2025

@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:Aptos; panose-1:2 11 0 4 2 2 2 2 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:536871559 3 0 0 415 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman",serif; mso-fareast-font-family:Aptos; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-font-kerning:1.0pt; mso-ligatures:standardcontextual;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; mso-fareast-font-family:Aptos; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}

October 1, 2025

The Poetry of Transitions: A Community Conversation of Discovery

It was such a pleasure (and honor!) to recently share poems and ideas, focused around how poetry connects with transitions in life -- and to do this with a group of community members, for an enjoyable hour that also included some impulsive moments of song, and plenty of laughter and learning.

Catch up with it all here, in this recording courtesy of OLLI St. Johnsbury, Catamount Arts, and KATV community access television: https://www.katv.org/vod/osher/2025/20250925

September 30, 2025

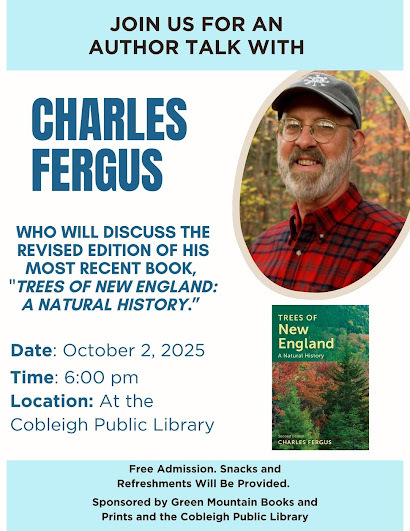

Diversion: In the New England Narrative Tradition, TREES OF NEW ENGLAND by Charles Fergus

This year's two directions for this set of essays relate to what I write: poems, and fiction set in 1850s Vermont. But sometimes I like to chat about other authors' work.

Charles Fergus first came to my attention (and that of my late husband Dave) for his book BEARS in the Wild Guide Series. Later, as we began to share research on America's 1800s for the historical fiction we both craft, we also exchanged book recommendations, especially for crime fiction and some literary work, too.

Last year, Charles mentioned that he'd been asked by publisher Globe Pequot to prepare a new edition of his 2005 book TREES OF NEW ENGLAND: A NATURAL HISTORY. As the publication date neared, I ordered a copy so I could read it right away.

But this isn't a book to be devoured with speed. Instead, it offers a slow, comprehensive, and highly personal ramble (alphabetically) through the trees that surround and often support New England residents. There are no color images -- the book is not a field guide, this author warns at the outset -- but instead delicate and detailed black-and-white drawings from the pen of Amelia Hansen. Though I missed the familiar bright field-guide images at first, I soon discovered that between Hansen's unusual details of bark growth and leaf individuality, and Charles Fergus's meditative reflections on each tree's structure and growth, I felt more capable of identifying the trees around me, including my beloved maple sapling rescued from a backhoe and beginning to show serious growth in the front garden.

This year I've become a daily reader of excerpts from the classic American philosopher of outdoor New England, Henry David Thoreau. And that's one voice I hear in the writing in this new book -- along with others like Aldo Leopold and Louise Dickinson Rich.

Here is a sample from this Charles Fergus book:

"I have watched ruffed grouse eating aspen buds. In the last day's light, the birds alight in a winter-bare tree. Their feathers fluffed against the cold, they clamber about on the swaying branches, using their beaks to wrench off the energy-packed buds. ... Aspen buds and catkins are favorite foods of the ruffed grouse throughout the bird's range, which largely coincides with the range of bigtooth and quaking aspen in North America."

Or in the section on yellow birch:

"Fence-row trees cast sharp shadows in the moonlight. Beneath my snowshoes the snow groaned, and when I kicked a ball of ice, it made a hollow tinkling as it rolled along the top of the crust. I crossed our hay field to where a logging road led into the woods. Trunks of maple and ash etched dark vertical lines against the snow. I was brought to a halt by another tree that presented a different aspect. Its bark was pale and burnished. Thin, ragged strips of bark curled away from the trunk, catching the moon's glow."

Will you be within driving distance of Lyndonville, Vermont, on October 2? As the poster here shows, there's a great opportunity to meet this thoughtful and knowledgeable author at the Cobleigh Public Library there, and to hear more about his observations of the trees that surround us.

September 22, 2025

The Poetry of Transitions: Where Do Poems Come From?

The earliest poems in my life were lullabyes and nursery rhymes, and I remember them well. In fact, I still sing them. But I've never quite gotten used to the shivery side of this one, which somehow reappeared around bedtime:

Rock-a-bye baby on the treetop.

When the wind blows, the cradle will rock.

When the bough breaks, the cradle will fall

and down will come baby, cradle and all!

Come on, who would sing that to a baby? A baby they cared about? Well, my parents sang it to me, and somehow the melody and the arms around me took away the sting.

On Thursday Sept. 25, I'll be leading a discussion of the Poetry of Transitions, at Catamount Arts, 115 Eastern Ave, St Johnsbury, starting at 1:30 pm. I hope you'll come and bring with you some ideas about the poetry that stays with you -- poems that are memorable -- and why and how that happens. And I'll share with you some of my ideas, as well as some poems of others and some of my own new-ish ones, and a taste of my 2026 book, THRESHOLDS.

We can figure out this puzzle!

September 16, 2025

Looks Like There Will Be an Audiobook of THE BITTER AND THE SWEET!

In surprise news today, an editor at All Things That Matter, the brave and clever publisher of THE BITTER AND THE SWEET, said there will soon be applications open to record this Vermont historical novel as an audiobook. I am thrilled! People often ask me about this, and it's the first time a publisher has offered to invest in the special version like this.

The first related author task for this process was to provide the sounds of unusual words in the book, like characters (popular names in the 1850s have sure gone out of fashion today) and places. That second part surprised me for a moment, but then I realized that St. Johnsbury might seem a strange name to a "voice actor" from, say, Georgia or Oklahoma.

So here's my list. Do you remember where in the book each one comes up? And if your answer is, you haven't yet read this third book in the Winds of Freedom -- what are you waiting for? It's available on request from local booksellers, as well as online, or you could encourage your local library to pick up a copy that more neighbors could share.

The Bitter and the Sweet -- Pronunciations

Almyra: al-MY-ruh

Antoinette: an-twuh-NET

chamomile: KAM-oh-mile

Crimean: cry-ME-uhn

Dana: DAY-nuh

Eli: EE-lie

Eliphalet: ell-IF-uh-let

Ephraim: EE-frum

Grimkeé: GRIM-kay

Hazen: HAY-zen

Isaiah: eye-ZAY-uh

Jerusha: juh-ROO-shuh

Jewett: JOO-it

medicament: MED-ick-uh-ment

Myles: miles

Peacham: PEECH-um

Potton: POTT-un

Rokeby: ROKE-bee

Stanstead: STAN-stead

St. Johnsbury: Saint JONS-burry

Stowe: STOH

<font size="4">@font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;}@font-face {font-family:Aptos; panose-1:2 11 0 4 2 2 2 2 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:536871559 3 0 0 415 0;}p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin-top:0in; margin-right:0in; margin-bottom:8.0pt; margin-left:0in; line-height:115%; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman",serif; mso-fareast-font-family:Aptos; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-font-kerning:1.0pt; mso-ligatures:standardcontextual;}.MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; mso-fareast-font-family:Aptos; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-latin;}.MsoPapDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; margin-bottom:8.0pt; line-height:115%;}div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;}</font> For extra pleasure, check out this online guide to the skills needed to become a successful audiobook narrator, or this one about what makes a GREAT one.

September 9, 2025

The Poetry of Transitions: Re-Shaping for an After-School Group

There's always someone creative taking charge of after-school groups of students who want to spend a few hours doing something "interesting."

So when one reached out to me a few weeks ago, asking what I could offer to her eager and probably very active students, I spilled out my enthusiasm about this new niche of mine, the poetry of transitions. I explained how it could become a nifty activity after school. I guess I had seventh and eighth graders in mind.

But these kiddos are younger than that, it turns out. So, the leader asked, what did I have up my sleeve that might suit that crew instead?

It took me back to my early years of poetry, when my mother modeled how to craft a birthday or Christmas card by making up a rhyme about the person, the occasion, or the things you love, like snow falling on a quiet evening or the first ringing bells of a holiday.

I emailed back:

How about "poems for special occasions" -- where we could lay out a range from birthdays and Christmas to completed homework, awesome book reports, new friends, broken friendships, and more.

And that, of course, spun me into wanting to write some of those childhood rhymes again. It's always fun, and often surprising. The following is NOT, of course, for an after-school program, but thoughts on where my own poems have been wandering.

Over Labor Day weekend, one of the poets I studied with, Rachel Richardson, suggested ways to make a collage out of lines that others had already written. Using lines from e.e. cummings, Walt Whitman, Ted Kooser, Dyaln Thomas, and Nick Laird (new to me that day), I put this together:

my father moved through dooms of love

Captain, oh my captain

although I miss you every day

do not go gentle into that good night

what are the ceremonies of forgetting?

It's actually not a bad place to start, as I approach another anniversary of my father's death. And indeed, what a "transition" that was, 27 years ago, for me and for my siblings.

Now, where will I take this? Where will you take your own? Can you still talk with your father face to face, or do you summon up his spirit for conversations while you're making a long drive? What would he say if you surprised him with --

Go ahead. Let a line form in your thoughts. That's the point of poetry ... or one of them, anyway.

By the way, if you're curious about what poet Rachel Richardson achieves with her poetic collages -- check out her newest collection of poems, SMOTHER. I bought a copy to treat myself.