Christian Monö's Blog

November 27, 2025

The complexity of following orders

On November 18, 2025, six Democratic members of Congress published a video telling the US military: “You must refuse illegal orders.” The comment referred to what many consider illegal military strikes by the Trump administration against boats in the Caribbean. The Trump administration responded by calling this encouragement to refuse unlawful commands “potentially unlawful comments”.

Let’s put our opinions aside for a moment and look at this from a soldier’s perspective. Most people agree that one shouldn’t obey illegal orders—but what makes an order illegal?

Human laws are not universal truths like gravity or thermodynamics. They’re man-made and can be shaped by anything from moral principles and common sense to hatred, fear, and simple opinion.

In addition, the legality of an order will often depend on who’s in power or—in times of war—who’s winning. This means that an action can be seen as both legal and illegal at the same time. Such was the case in 2003, when military forces led by a US–UK coalition invaded Iraq. The countries involved argued the invasion was legal under existing UN Security Council resolutions. Many legal experts, world leaders on the other hand, including then–UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, argued the opposite—that the war violated international law.

So how would you, as a soldier, navigate such a situation? Below is an excerpt from Why We Follow where I discuss the Malcolm Kendall-Smith case— the British officer who refused to obey orders because he believed the Iraq intervention was illegal. As you will see, such a decision comes with great personal risk, even if your disobedience is supported at an international level.

If you’re the one giving orders, you’ll be judged by the decisions you make.

If you follow orders, you’re judged by the decisions others make.

I often find it striking that we pay managers and other decision-makers higher salaries not primarily because we expect them to make decisions, but because they’re responsible for the decisions they make. Yet in many ways, it is much harder to be a subordinate.

If you’re the one giving orders, you’re judged by the decisions you make. If you’re following orders, you’re judged by the decisions others make. This means you may be punished regardless of whether you obey an order or refuse it. So what can we do?

I believe that as subordinates, we should consider two essential questions before following an order:

Does the order conflict with any laws, rules, or regulations?

Does the order go against any of our moral values?

The first question will often be enough to guide us. However, if—as we’ve seen above—there are conflicting views (even within yourself, between what is legal and what is right), then the second becomes your compass. Because at the end of the day, you have to live with the decisions you make, whether you’re seen as a decision-maker or a subordinate, a leader or a follower.

***

The Kendall-Smith Example Excerpt from Why We FollowIn 2006, British officer Malcolm Kendall-Smith was sentenced to eight months in prison and ordered to pay more than £20,000 (approximately $37,000 at the time) in legal fees and costs. Why? He had refused to obey his superior’s orders.

Kendall-Smith was a medical officer in the British Royal Air Force. Three years earlier, the US, Great Britain, Australia, and Poland had invaded Iraq for reasons that remain complex. The details are irrelevant, but even today, many believe the allies lacked both justification and legal right to start the war. Kendall-Smith was stationed in both Kuwait and Qatar during the initial stages of the war. It was during this time that he began to question the invasion. He believed that, as an officer, he was “required to consider each and every order.” Therefore, he spent time examining the grounds on which Britain had decided to initiate the war.

“I have satisfied myself that the actions of the armed forces in Iraq were, in fact, unlawful, as was the conflict,” he concluded. So, when ordered to Iraq a third time, Kendall-Smith refused. “I believe that the current occupation of Iraq is an illegal act,” he stated, “and for me to comply with an act which is illegal would put me in conflict with both domestic and international law.”

Let’s consider Kendall-Smith’s case. We’ve just seen that soldiers may be punished for obeying unlawful orders, but here we have a soldier who’s punished for refusing to obey orders he interpreted as illegal. In fact, during the trial, the judge turned to Kendall-Smith and said: “You have, in the view of this court, sought to make a martyr of yourself and shown a degree of arrogance which is amazing.”

Was Kendall-Smith’s questioning of the legality of the invasion unreasonable? I don’t think so. There had been international disagreements on how to deal with Iraq before the invasion in 2003. US President George W. Bush had mixed support from the American people for an armed attack, especially after no weapons of mass destruction were found. In Great Britain, on the other hand, Tony Blair faced tough national criticism. Countries like Poland, Spain, Australia, Kuwait, and Japan supported the US, while Germany, France, Sweden, Greece, Austria, Finland, Russia, and others opposed war. For Kendall-Smith, it mattered little that the world was divided on the issue.

“Obedience of orders is at the heart of any disciplined force,” the judge argued. “Those who wear the Queen’s uniform can’t pick and choose which orders they obey, and those who do so must face the consequences.”

From Why We Follow

November 24, 2025

We Didn’t Evolve for This

I recently read an article by evolutionary anthropologists Colin Shaw and Daniel Longman, who argue that our biology isn’t adapted for modern cities. Everyday stressors—traffic, office pressure, constant digital stimulation—trigger ancient systems built for life-or-death situations.

Humans evolved to live in small bands of 25–50 people where everyone participated in decision-making that affected their lives. Today we share our space with thousands (if not millions) of others, and most of us stand on the sidelines while others make important choices for us.

My point is this: We may have structured ourselves hierarchically, with managers and cubicles, but that doesn’t mean we’ve discovered the optimal way to collaborate. I believe that, just as cities have outpaced our evolution, so has the way we organize work.

I’m utterly convinced that the future belongs to the companies, organizations, and even countries that best align structure and culture with our evolutionary wiring.

What would it look like if we designed work environments fully adapted to human nature? One thing is certain: the way we organize ourselves today is not the only way. Better structures and models exist — we just need the courage to explore them.

This is why I argue we should explore the natural process of leading and following—where followers aren’t subordinates, and leaders aren’t decision-makers. Doing so, I believe, will lead to discoveries that can fundamentally change how we collaborate and create together.

November 14, 2025

For the Love of Science: Define What You Mean by Leader

I’m currently doing research for a new book. I find it fascinating that despite academics’ love for peer-reviews and clear definitions, the concepts “leader” and “follower” are still routinely used in leadership literature without being defined.

When reading these texts, you must consciously or unconsciously interpret the meaning of these concepts. Does the author define leaders as decision-makers, or maybe a type of decision-maker? Or perhaps they believe that being a leader has nothing to do with having a formal role of power or influence? It’s up to you to figure it out.

It’s the same within followership literature. If the concepts aren’t defined, then how do you know what the author means when speaking about followers? Do they see followers as subordinates or a type of subordinate? Maybe, as in my work, being a follower has nothing to do with the formal role or position you hold.

This is problematic for two main reasons:

It makes it hard to fully understand and evaluate the author’s arguments,

It increases the risk of misinterpretations, leading to the reader drawing flawed conclusions.

So, for the love of science, if you write about leadership and/or followership, please define the concepts in your texts. That way, you’ll help bring clarity to this broad and increasingly muddled subject.

In 1994, Manfred Kets de Vries—a Dutch professor of leadership development—wrote that “as far as leadership studies go, it seems that more and more has been studied about less and less, to end up ironically with a group of researchers studying everything about nothing.”

I believe Kets de Vries is right, and the reason for this is that “leader” can mean almost anything to anyone. So, let’s clarify the conversations by explaining the terms we use.

A Quick Exercise:Look up a few books or articles discussing leadership and see if the authors define “leader” in the text or if it is up to the reader to interpret its meaning. If you like, please share your findings.

November 4, 2025

Brave enough to speak your mind?

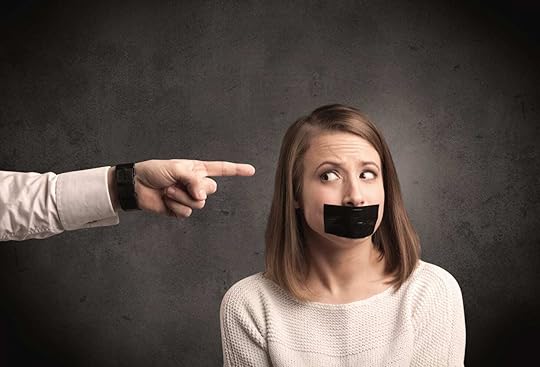

Do you have the courage to speak your mind, be it against superiors or larger groups of people who see things differently? Most likely, your answer depends on the situation.

A new study by Arizona State University and the University of Michigan explores the hidden dynamics of self-censorship. This is an important topic for anyone interested in natural followership or collaborationship.

The study shows that self-censorship (the act of censoring what one says or does) is not simply impacted by fear. Rather, it’s a form of strategy. People balance what they want to say with the potential risk of being punished for saying it.

What’s interesting is that the type of punishment appears to matter. “Uniform punishments,” where everyone gets the same penalty for a certain type of offence, tend to produce widespread self-censorship. “Proportional punishments,” on the other hand, where the penalty scales with the severity of the offence, allow for more risk-taking. In such situations, people are more willing to voice their disapproval.

Bold populations resist self-censorship better.According to Merriam-Webster, bravery is “the quality or state of having or showing mental or moral strength to face danger, fear, or difficulty.” In other words, bravery is having the courage to act despite fearing the consequences.

According to the study, populations with higher “boldness” (i.e. willingness to risk negative consequences) tend to resist self-censorship better than more fearful populations. However, if surveillance intensifies or punishment becomes stricter, even bold participants will gradually conform.

This is why it’s critical that we have the courage to speak up and voice our concerns before those in power gain too much control and start introducing different forms of punishment.

Authority adapts over timeAnother important observation from the study is that authoritarian rulers or managers will often adjust their surveillance and punishment over time in response to how much dissent or silence they observe.

What starts as moderate oversight may evolve into stricter control — which, in turn, can shift the balance toward silence rather than open dialogue.

Beware of normalizationFast changes, in whatever context, are easier to spot than slow, gradual ones. I’ve seen this in organizations where management applies increased control in incremental steps. Whether intentionally or not, they reduce the risk of an organized backlash from employees.

While employees still react negatively to each change, the changes occur at such a pace that people adapt to what they consider “normal” management behaviour.

To make matters worse, if employees stay silent — even before being punished — that silence also becomes the “new normal.”

As a result, it’s not until they speak with friends or family that they may realize the absurdity of what’s happening in their organization. By then, there are generally just two options: adapt or quit.

Again, that’s why it’s important for people to react sooner rather than later when disagreeing with what’s happening. This is where bravery comes into play. Bravery is the strength to speak up or take action for what you believe is right, even when it’s difficult, unpopular, or risky.

To all managersAs I’ve pointed out before, collaborationship can only function in environments where people feel safe enough to voice their opinions — even if it means criticising decisions made by others.

The whole point of building collaborationship is to have a group make better decisions together. A manager who gets upset every time an employee disagrees with them or questions their decisions should not be a manager. Frederic Taylor’s vision of managers as the “know-it-all” has been debunked long ago. The modern manager has one main task - to create an environment where people collaborate brilliantly together.

So what can we learn from this?From a collaborationship perspective:

In any collaborative setting (team, organization, community), people will choose silence when they perceive that speaking up is risky — even if there’s no explicit punishment. This will kill any attempt to build collaborationship.

“Boldness” is crucial. Having the courage to speak up, even when there are certain risks, is key to reducing self-censorship and maintaining a healthy collaborative environment.

The type of response to dissent matters. If pushback is met with punishment of any form, silence will dominate.

Speak up quickly. Once silence sets in, it’s hard to regain the openness required to build strong collaborationship.

If you’re thinking about psychological safety, participatory decision-making, or co-creative culture design — this is a paper worth reading.

I’d also love to hear if you’ve ever experienced a situation where early dissent made an impact on decisions made in an organisation.

October 9, 2025

We care for each other – and always have

Perhaps you, like me, are exhausted by the torrent of angry, narrow-minded men sweeping across our planet right now, creating havoc wherever they go. In their hunger for power and status, they provoke, blame, threaten, and lie. They divide people — turning neighbours and friends against each other. It’s the oldest trick in the book, and it saddens me that we aren’t more resilient to it by now. We are better than this.

A new study from Patagonia shows that 2,000 years ago, nomadic hunter-gatherers took care of one another — including those who could no longer hunt, move, or contribute in traditional ways. This isn’t the first time research has shown this. Again and again, we find evidence that our ancestors helped and supported each other.

In a world where survival depended on mobility and strength, care still prevailed. We humans are wired to collaborate — and, as I discussed with Sharna Fabiano earlier this year, our greatest superpower is our ability to build what I call collaborationship.

We have always achieved more through care, collaboration, and interdependence than through division, hierarchy, and dominance. This isn’t an ethical perspective or my opinion—it’s a simple fact.

Our ability to see value in each other and collaborate is not only a skill, it’s what makes us human.

Previous posts:

September 17, 2025

Natural vs. Structural Leadership and Followership

Imagine you’re exhausted after a long day and just about to leave the office when your boss asks you to stay late to finish a report for the board of directors. Chances are you’ll agree—not because you admire your manager or care deeply about the board, but because you’ve signed a contract. That’s the deal: you give your time and effort in exchange for compensation, and in return, you accept certain limits on freedom and decision-making during work hours.

Most research on leadership and followership is conducted in non-natural settings such as schools, businesses, political parties, armies, and sports teams. While these environments differ, they share one thing in common: they are socially constructed environments—systems deliberately designed to organize people.

Take the workplace as an example. It’s an invention, created to coordinate labour in the production of goods and services. The relationship between employee and employer is based on a formal contract, and the entire system relies on laws and practices to function. We can’t, for example, force people to work for us. As employees, we agree to exchange our time and effort for compensation. But in doing so, we also give up a certain level of freedom and decision-making during work hours.

Structural Leadership

One of the main objectives of a constructed environment is to coordinate people’s actions. This can be done in different ways—through rules and regulations that control behaviour, and/or by giving certain people the authority to dictate what others should do. In a workplace, the latter are usually known as “managers.”

For decades, we’ve preferred the word leader over manager. The term manager is often seen as negative—someone who enforces rules, supervises, or simply “bosses people around.” Leader, in contrast, is framed as positive—someone who motivates, empowers, and collaborates with others to achieve shared goals.

But as I discuss in Why We Follow, the objective is ultimately the same: coordinating people to move in a certain direction. To avoid the endless “manager versus leader” debate, I use the term structural leadership to describe any process in which one individual has formal decision-making rights over others.

The challenge with structural leadership is that it relies on external factors—contracts, salaries, rules, or laws—to sustain collaboration. A team may follow their manager’s lead, but if the paycheck stops, most people will leave.

Natural Leadership and Followership

The opposite of socially constructed environments are natural environments—settings that emerge organically and aren’t shaped by design. Think of the way friends interact. These relationships are fluid, guided by instincts, trust, and shared interests rather than contracts or rules.

As I explain in Why We Follow, natural leadership and followership happen when people voluntarily choose whom to follow based on who they believe is best suited to achieve a specific goal at that moment.

Unlike structural leaders, natural leaders don’t hold permanent positions of power or influence. Leadership flows freely, shifting from one person to another depending on the situation. This makes collaboration more flexible, resilient, and effective, while avoiding the risks that come with fixed hierarchies or manipulative influence. In essence, it’s a dynamic, situational way of working together to achieve shared goals.

Why This Distinction Matters

It’s striking how much of our leadership thinking is shaped by research in structural environments. Yet these environments are human inventions—and therefore changeable. The workplace today looks very different from 150 years ago, and even now it varies widely between countries and companies.

If we understand natural leadership and followership better, we can design our schools, organisations, and societies in ways that encourage more engaging forms of collaboration. If we want healthier, more resilient systems, we need to bring the natural back into the structures we create. The challenge now is to rethink the environments we’ve built—and ask how they can better reflect the way people truly collaborate.

July 20, 2025

You Wouldn’t Eat Rotten Food—So Why Accept Rotten News?

I typically listen to books, but summer vacation is a time for reading. It means I can finally pick up the books I haven’t had time for. One of these is Ira Chaleff’s To Stop A Tyrant. I’ve just started it, and as with any great non-fiction book, it gets my mind spinning from the start.

Yesterday evening, I read the following from the book:

“If we [as followers] are not sufficiently informed, we are not prepared to make good choices. … On any issue, at either end of the political spectrum, if we only get our information from one side of that issue or one end of the political spectrum, we cannot make an independent judgment.”

Therefore, Chaleff continues, “What we can do is consciously choose to get our information from several points on the political spectrum, then assess for ourselves which we judge to have greater value.”

I completely agree with Chaleff that this is absolutely necessary. That, however, doesn’t make it easy. To objectively explore diverse perspectives requires commitment, determination, and consistency. One must continuously search for and consume different sources of information. While that may seem easy in theory, in practice it’s hard. I think it’s comparable to someone trying to lose weight or eat healthier.

Most people who want to lose weight generally know enough to achieve what they want. The problem is now knowledge but consistency. How does one maintain the positive routines again and again?

Chaleff’s comment made me think about the importance of constructing an environment that encourages the behaviours we desire. If we want people to consider different perspectives, we should look at how to simplify that process for them. That made me think of the news media.

News media play a critical role in our society. For centuries, they’ve painted a picture of the world and shared it with their readers. But what kind of image are they sharing?

In 2020, a Gallup/Knight Foundation study found that 8 out of 10 Americans believe there is a fair amount of political bias in news media. A study by the University of Rochester, covering the years 2014 to 2022, shows that major U.S. news outlets are becoming more biased. This is the precise opposite of what we would like to see.

Another problem is the lack of trust in the media. Because of the above, people are less likely to trust what is said in the news. This becomes problematic. Comparing it to weight loss again—if we don’t trust the experts, then the likelihood that we’ll take their suggestions seriously is rather low.

Interestingly, people choose what facts to believe in. The Gallup research mentioned above shows that while most people believe news media are biased, only 3 out of 10 believe their news media is biased.

Ira Chaleff’s book - To Stop a Tyrant. So what can we do?

Ira Chaleff’s book - To Stop a Tyrant. So what can we do?To begin with, we need to amplify the discussion on news media objectivity. As consumers of news, we have a responsibility to demand objectivity from our sources. You wouldn’t accept buying rotten food—so why would you accept rotten news?

Second, media must be accessible to everyone. Many news sources require payment and thus become inaccessible to people who cannot afford to subscribe to several different outlets. But this is doable. If The Guardian, YouTube, Google, and Spotify can provide free versions (albeit with advertisements), then so can other serious newspapers.

To conclude, Chaleff’s point about information diversity is key—but now we need to discuss how to create an environment where this becomes doable for everyone.

Missed previous posts?July 8, 2025

Questions Every Young Person Should Consider Before Rejecting Democracy

Yet another poll has concluded that nearly half of young Europeans are dissatisfied with democracy. According to this study, more than one in five (21%) “would favour authoritarian rule under certain, unspecified circumstances.”

It’s tempting to blame social media, disinformation, or economic stress, but as I’ve discussed before, I suspect something deeper is at work. For decades, we’ve told our children that leadership is the key to success. At the same time, we complain that democracy is messy, bureaucratic, and often inefficient. Why would any of them believe democracy is the way to go?

Do they realize what they’re willing to give up?Anyone who says they’d trade democracy for strongman rule is effectively saying, “I don’t believe my own opinions and freedom matter. I’d rather someone else decide my life for me.” Is that really what they want?

Have you ever met a teenager who claims they enjoy having their parents dictate their lives? I haven’t. Teenagers put up with certain orders from their parents because they’re dependent on them and (hopefully) because they love and respect them, knowing their parents have their best interests at heart. They also understand that one day they’ll move out and become independent, so they know their current subordination is only temporary.

Democracies may be bureaucratic, messy, and frustrating at times, but that so-called mess is exactly what protects our freedom. Among other things, it serves as a safety net, ensuring that different perspectives and opinions are considered before and during the decision-making process. As I’ve said many times before, making decisions is easy — making the right decision is not. Giving one person all the power dramatically increases the risk of bad decisions.

Questions for the youngIf you work with young people—in schools, youth organizations, or even around your own dinner table—here are some questions worth exploring. They’re not meant to shame or scold, but to spark real thinking. Please feel free to use them, share them, or adapt them to your context.

Let’s Keep the Conversation Going

Would you like your parents decide everything about your life forever—your job, partner, where you live?

If not, why?

Would you let someone else do it?

Who would you trust with absolute power over your life if you gave up that right? FOLLOW UP QUESTIONS:

Why this person?

Do you think they would always put your interests first? If they didn’t, or if they died or lost power, what would you do?

What would you do if you found out they protected your interests but harmed others?

Would you rather live where decisions are quick but only help a few, or slow but consider many perspectives? If it’s the former, are you okay being one of the people left out?

There’s a big difference between fixing democracy and rejecting it altogether. If we want to protect our freedoms, we need honest conversations — especially with young people — about what democracy gives us, and what’s at stake if we lose it. Leadership isn’t the solution; collaborative engagement is.

So I hope you’ll pass these questions along to anyone who might use them, in classrooms, workplaces, or at home. Because once democracy is gone, it’s incredibly hard to get back.

Similar postsThanks for reading Natural Followership Newsletter! Subscribe for free to receive new posts.

June 28, 2025

Saving Democracy: Are We Focusing on the Wrong Things?

We live in a time when the world is facing a tide of so-called neo-authoritarian rulers, such as the US’s Donald Trump, Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu, Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and so on.

It’s often said that dictators tend to be charismatic, luring people to trust and support them, but I believe reality is far more complex.

Voting against rather than for something

When governments and institutions fail to meet people’s needs, the people will eventually turn to anyone who takes their frustration seriously. As author Richard David Hames put it:

“People understandably gravitate toward rulers who validate their frustrations, even if they exacerbate the underlying problems. The more incompetent the leadership becomes, the more fervently it's defended by those who will suffer most from its failures. This is not just facile political polarisation; it represents something deeper and more dangerous: a collective flight from the yoke of reality.”

Hames’ point is spot on. Dictators gain ground not because of who they are, but because existing governments weren’t paying attention or couldn’t mitigate the people’s frustration. Simply put, it’s not about who these wannabe dictators are—it’s about what they promise to fix. In the end, we’re here not because people are voting for someone, but because they’re voting against something.

The quiet dismantling

Once a wannabe dictator has gained power, the next step is to dismantle the democratic systems. This is often masked by a wave of media-grabbing actions. By creating drama and conflict, these authoritarian rulers shift the spotlight away from what matters—the slow destruction of democratic systems. Many act as national or global bullies, targeting anyone or anything standing in their way. They lie, cheat, and stir up violence, often behind the vague promise of restoring their country to its former glory. In reality, they’re attacking the fundamental structures that uphold democracy. So while we’re left stunned by the actions of Trump, Putin, Erdogan, and Netanyahu, our democratic rights are being stolen behind our backs.

Focus on what matters

Those of us living in a democracy share one key responsibility: to protect our democratic systems. A crucial factor here is ensuring that democratic institutions remain independent from the government. These institutions exist to provide checks and balances on power, so that no single entity becomes too powerful or authoritarian. By functioning independently, they help prevent abuses of power, corruption, and the erosion of democratic principles.

It doesn’t matter what our stance is on taxes, schooling, immigration, or climate change. We are the protectors of our democratic systems. We cannot let ourselves be emotionally manipulated into accepting the dismantling of the very structures that were put in place to protect us.

Previous postsMay 13, 2025

Think Collaboration Is Important in Business?

Have you ever met a manager, CEO, or business owner who seriously argues that collaboration between employees is a waste of time? I haven’t. On the contrary, I’ve met plenty of managers who claim that collaboration is one of the most important factors for success. Studies confirm this—good teamwork and collaboration “significantly improve efficiency and productivity” (https://doi.org/10.30574/wjarr.2025.25.2.0343).

How well people collaborate determines what they can achieve together. Some teams defy all odds and perform far beyond what anyone thought possible. Then there are teams that, on paper, have all the qualifications for success but still manage to fail miserably.

We humans are remarkably skilled at complex collaboration, but that doesn’t mean we’re born with perfect collaborative abilities. Like any skill, collaboration must be explored, practised and refined—a lot. With that in mind, how much time have you and your colleagues spent deliberately improving your collaborative skills?

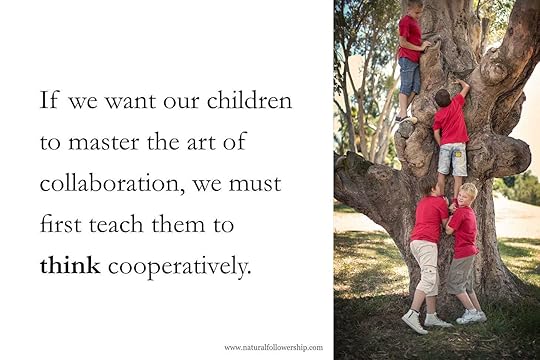

Start EarlyConsidering how important collaboration is, I’m surprised we don’t spend more time practising it. In today’s hyper-individualistic society, people are often encouraged to focus more on their own performance than on that of the group to which they belong.

It starts in school. As I state in my book, Why We Follow: Natural Followership in a World Obsessed with Leadership:

“We say we want our young to learn how to collaborate, but once our kids start school, they realize that they are evaluated, tested, graded, and compared to one another as if they’re competing in a lifelong contest. By the time they graduate, most of them will be convinced that life is all about positioning oneself in a hierarchy.”

In other words, instead of priming our children to think in terms of collaboration, we’ve built systems that encourage self-interest. Even team efforts—like group work—are often individualistic, since students know that their personal performance can either boost or drag down their individual grades.

If we want children to master the art of collaboration, we must first demonstrate that cooperation is a trait we genuinely value. That means not only teaching collaborative skills but also creating structures that reward collaborative behaviour. If students are primarily measured on individual performance, that’s exactly what they’ll focus on.

Collaboration at Work

Collaboration at WorkMost workplaces aren’t much better. For some illogical reason, companies will gladly invest in leadership training while offering little or no training on collaboration. Why?

Add to that the fact that few organizations take the time to audit their own structures for behaviours or systems that undermine collaboration. What structures do you have in place today that might encourage self-centred behaviour? Do you use individual bonus systems or competitions that pit employees against one another? Do you spotlight individuals instead of teams through initiatives like “Employee of the Month”?

My point is this: We can’t claim that collaboration is important and then make no effort to develop it. If you truly believe collaboration is vital for success, why not commit to improving it where you work?

Next step?

If you want to improve collaboration at work, start by exploring how you perform within these areas:

Shared vision and goals

Look at any high-performing team, and you’ll see members who genuinely share a common goal. What’s it like in your workplace? Do employees truly share the same vision?

Embrace differences

Don’t fear disagreement—embrace it. Differing opinions broaden a group’s perspective and provide more data points than homogeneous teams can offer.

Active listening

Pay close attention when others speak. You already know your own thoughts—start by understanding what others are thinking. Ask questions, seek clarification, and ensure everyone has the chance to contribute. Don’t interrupt, and be patient when it’s not your turn.

Strive for consensus

Reaching consensus means that everyone can accept a decision, even if it’s not their favourite. It doesn’t require full agreement—just enough alignment to move forward together. To build consensus, work backwards: eliminate the least favourable ideas first, then the second least, and so on until one viable option remains.

Natural Followership NewsletterRedefining leadership. Rethinking Followership.By Christian Monö

Natural Followership NewsletterRedefining leadership. Rethinking Followership.By Christian Monö