Bernie MacKinnon's Blog - Posts Tagged "battle-of-franklin"

Grim Anniversaries

Hi Everybody—

One thing that spurred me to publish Lucifer's Drum this past summer was that fact that the event it's based on—Jubal Early's nearly successful attack on Washington DC—was marking its 150th anniversary. But over the past three and a half years, practically any given day has commemorated the 150th anniversary of something bloody. Case in point: today marks 150 years since the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado, when Col. John Chivington and his soldiers attacked a peaceful encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho. They killed approximately 130 of them, including many women and children. The Cheyenne chief Black Kettle survived somehow, only to die in a similar sneak attack four years later, at the Washita River in present-day Oklahoma. This time the attacker was George Armstrong Custer, who that day earned a new nickname among the Cheyenne: Creeping Panther. It was during the Civil War that western expansion and consequent conflict with the western tribes entered its final and worst phase, a phase that would end in the freezing cold of Wounded Knee Creek in 1890.

And tomorrow will mark the sesquicentennial of the Battle of Franklin, south of Nashville. Which gives me the opportunity to speak of Howard Bahr's darkly beautiful gem The Black Flower. Franklin is the centerpiece for that novel. Unlike another work of Civil War fiction which had a big impact on me—Michael Shaara's The Killer Angels, with its classic depiction of Gettysburg—The Black Flower unfolds through the eyes of rank-and-file soldiers and of civilians, not colonels and generals. Its chief character is a Confederate rifleman, Bushrod Carter, who is mulling the possibility of becoming a deserter (a common thought, then, I'm sure, given what these men had been through and the growing sense of hopelessness) while events tumble toward grand-scale tragedy.

I don't think I can adequately convey the effect of Mr. Bahr's quiet restraint. Out of it rises something like an epic fugue, an anthem of sorrow. I am not saying it is all tone—the story is plenty gripping. The sense of what it was like—the texture of time and place, the sights and smells—is so potent that it makes you feel you have been teleported to Nov. 30, 1864. And the depiction of the battle—again, no general's eye-view but a foot soldier's—thrusts you into clamor, terror and chaos in a way I have never seen done. The moment before the doomed Confederate assault—a moment stretched to dreamlike infinity in the soldiers' minds—leaves you feeling, "Yes, it must have been like that." At the end you feel the satisfaction that comes with experiencing a fully realized work of art—but you also mourn, for people long dead.

For anyone who's interested, here is the Amazon link for The Black Flower:

http://www.amazon.com/Black-Flower-No...

Well, folks, gotta move. Talk at you again soon.

—Bernie

One thing that spurred me to publish Lucifer's Drum this past summer was that fact that the event it's based on—Jubal Early's nearly successful attack on Washington DC—was marking its 150th anniversary. But over the past three and a half years, practically any given day has commemorated the 150th anniversary of something bloody. Case in point: today marks 150 years since the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado, when Col. John Chivington and his soldiers attacked a peaceful encampment of Cheyenne and Arapaho. They killed approximately 130 of them, including many women and children. The Cheyenne chief Black Kettle survived somehow, only to die in a similar sneak attack four years later, at the Washita River in present-day Oklahoma. This time the attacker was George Armstrong Custer, who that day earned a new nickname among the Cheyenne: Creeping Panther. It was during the Civil War that western expansion and consequent conflict with the western tribes entered its final and worst phase, a phase that would end in the freezing cold of Wounded Knee Creek in 1890.

And tomorrow will mark the sesquicentennial of the Battle of Franklin, south of Nashville. Which gives me the opportunity to speak of Howard Bahr's darkly beautiful gem The Black Flower. Franklin is the centerpiece for that novel. Unlike another work of Civil War fiction which had a big impact on me—Michael Shaara's The Killer Angels, with its classic depiction of Gettysburg—The Black Flower unfolds through the eyes of rank-and-file soldiers and of civilians, not colonels and generals. Its chief character is a Confederate rifleman, Bushrod Carter, who is mulling the possibility of becoming a deserter (a common thought, then, I'm sure, given what these men had been through and the growing sense of hopelessness) while events tumble toward grand-scale tragedy.

I don't think I can adequately convey the effect of Mr. Bahr's quiet restraint. Out of it rises something like an epic fugue, an anthem of sorrow. I am not saying it is all tone—the story is plenty gripping. The sense of what it was like—the texture of time and place, the sights and smells—is so potent that it makes you feel you have been teleported to Nov. 30, 1864. And the depiction of the battle—again, no general's eye-view but a foot soldier's—thrusts you into clamor, terror and chaos in a way I have never seen done. The moment before the doomed Confederate assault—a moment stretched to dreamlike infinity in the soldiers' minds—leaves you feeling, "Yes, it must have been like that." At the end you feel the satisfaction that comes with experiencing a fully realized work of art—but you also mourn, for people long dead.

For anyone who's interested, here is the Amazon link for The Black Flower:

http://www.amazon.com/Black-Flower-No...

Well, folks, gotta move. Talk at you again soon.

—Bernie

Published on November 29, 2014 13:48

•

Tags:

battle-of-franklin, bernie-mackinnon, civil-war-anniversaries, howard-bahr, lucifer-s-drum, sand-creek

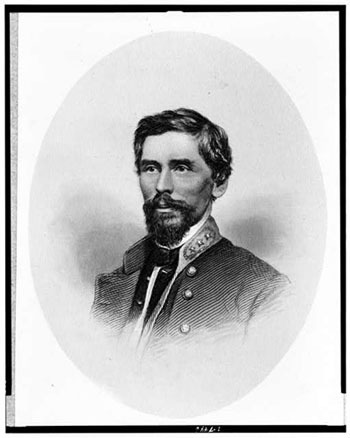

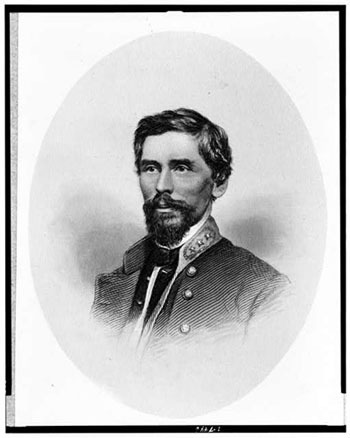

Pat Cleburne

In my last post I was talking about the Battle of Franklin and its depiction in Howard Bahr's dark gem of a novel, The Black Flower. I can't think about that battle without recalling its most distinguished casualty, Confederate General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne. Among the 6200 Southern casualties were six dead generals plus seven wounded and one captured. None, however, represented as big a loss to the South as Cleburne, who was called "The Stonewall Of The West." Tough, smart, resourceful and loved by his men, Cleburne had been born in County Cork, Ireland and emigrated to the United States at the age of 21, settling in Helena, Arkansas. There he worked as a pharmacist and later as a newspaper publisher. When the war threatened, his personal qualities and military experience (three years in the British army) made him a natural choice as captain of a militia company, which he led in January 1861 to capture the Union arsenal at Little Rock.

Three tumultuous years later, Cleburne figured in a quiet but very telling episode of the war. Recognizing the South's great manpower disadvantage and the urgent need to address it, Cleburne proposed to General Joseph Johnston and the rest of the Army of Tennessee's leadership that the South begin freeing slaves in return for their enlistment in the Confederate forces. A crucial passage of his address reveals both his knowledge of history and his blindness to what he was up against:

Born and raised in another country and not arriving in the South till early manhood, Cleburne had never grasped how fundamental slavery actually was to the war and to his adopted region, even though it was the threat to slavery's spread that had triggered secession in the first place. (In the research for my novel Lucifer's Drum, one thing was clear: slavery imbued the pre-war years like no other issue. Nothing else came close.) The other generals listened quietly and respectfully, but Johnston was reportedly shocked. And—no surprise—Cleburne's proposal was not discussed, let alone acted upon. The basic idea persisted, however, as Confederate desperation intensified. And in early 1865—truly the 11th hour, long past the point where it could have had any effect—the Confederate Congress authorized the first feeble steps for slave recruitment. Within a few weeks, the Union had triumphed.

At Franklin on November 30, 1864, Cleburne correctly judged General John B. Hood's assault plan as foolhardy but followed orders, exposing himself to maximum danger as the charge proceeded. His troops momentarily breached the Union line but were thrown back. Cleburne died while charging on foot after his horse was shot out from under him. His body was found plundered, without boots, watch or sword. He deserved far better. Then again, there were so many others of whom you could say that—on any side, in any war.

Portrait of General Cleburne. (Courtesy:

Library of Congress)

Three tumultuous years later, Cleburne figured in a quiet but very telling episode of the war. Recognizing the South's great manpower disadvantage and the urgent need to address it, Cleburne proposed to General Joseph Johnston and the rest of the Army of Tennessee's leadership that the South begin freeing slaves in return for their enlistment in the Confederate forces. A crucial passage of his address reveals both his knowledge of history and his blindness to what he was up against:

Satisfy the negro that if he faithfully adheres to our standard during the war he shall receive his freedom and that of his race ... and we change the race from a dreaded weakness to a position of strength.

Will the slaves fight? The helots of Sparta stood their masters good stead in battle. In the great sea fight of Lepanto where the Christians checked forever the spread of Mohammedanism over Europe, the galley slaves of portions of the fleet were promised freedom, and called on to fight at a critical moment of the battle. They fought well, and civilization owes much to those brave galley slaves ... the experience of this war has been so far that half-trained negroes have fought as bravely as many other half-trained Yankees.

It is said that slavery is all we are fighting for, and if we give it up we give up all. Even if this were true, which we deny, slavery is not all our enemies are fighting for. It is merely the pretense to establish sectional superiority and a more centralized form of government, and to deprive us of our rights and liberties.

Born and raised in another country and not arriving in the South till early manhood, Cleburne had never grasped how fundamental slavery actually was to the war and to his adopted region, even though it was the threat to slavery's spread that had triggered secession in the first place. (In the research for my novel Lucifer's Drum, one thing was clear: slavery imbued the pre-war years like no other issue. Nothing else came close.) The other generals listened quietly and respectfully, but Johnston was reportedly shocked. And—no surprise—Cleburne's proposal was not discussed, let alone acted upon. The basic idea persisted, however, as Confederate desperation intensified. And in early 1865—truly the 11th hour, long past the point where it could have had any effect—the Confederate Congress authorized the first feeble steps for slave recruitment. Within a few weeks, the Union had triumphed.

At Franklin on November 30, 1864, Cleburne correctly judged General John B. Hood's assault plan as foolhardy but followed orders, exposing himself to maximum danger as the charge proceeded. His troops momentarily breached the Union line but were thrown back. Cleburne died while charging on foot after his horse was shot out from under him. His body was found plundered, without boots, watch or sword. He deserved far better. Then again, there were so many others of whom you could say that—on any side, in any war.

Portrait of General Cleburne. (Courtesy:

Library of Congress)

Published on December 06, 2014 16:29

•

Tags:

battle-of-franklin, civil-war, lucifer-s-drum, patrick-cleburne