Bernie MacKinnon's Blog - Posts Tagged "civil-war"

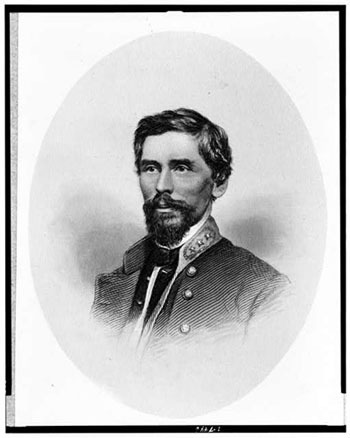

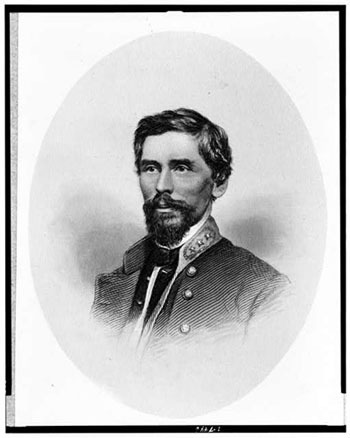

Pat Cleburne

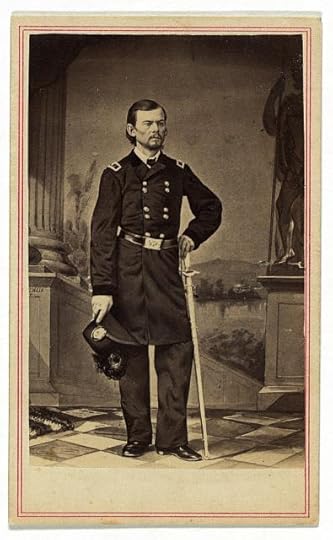

In my last post I was talking about the Battle of Franklin and its depiction in Howard Bahr's dark gem of a novel, The Black Flower. I can't think about that battle without recalling its most distinguished casualty, Confederate General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne. Among the 6200 Southern casualties were six dead generals plus seven wounded and one captured. None, however, represented as big a loss to the South as Cleburne, who was called "The Stonewall Of The West." Tough, smart, resourceful and loved by his men, Cleburne had been born in County Cork, Ireland and emigrated to the United States at the age of 21, settling in Helena, Arkansas. There he worked as a pharmacist and later as a newspaper publisher. When the war threatened, his personal qualities and military experience (three years in the British army) made him a natural choice as captain of a militia company, which he led in January 1861 to capture the Union arsenal at Little Rock.

Three tumultuous years later, Cleburne figured in a quiet but very telling episode of the war. Recognizing the South's great manpower disadvantage and the urgent need to address it, Cleburne proposed to General Joseph Johnston and the rest of the Army of Tennessee's leadership that the South begin freeing slaves in return for their enlistment in the Confederate forces. A crucial passage of his address reveals both his knowledge of history and his blindness to what he was up against:

Born and raised in another country and not arriving in the South till early manhood, Cleburne had never grasped how fundamental slavery actually was to the war and to his adopted region, even though it was the threat to slavery's spread that had triggered secession in the first place. (In the research for my novel Lucifer's Drum, one thing was clear: slavery imbued the pre-war years like no other issue. Nothing else came close.) The other generals listened quietly and respectfully, but Johnston was reportedly shocked. And—no surprise—Cleburne's proposal was not discussed, let alone acted upon. The basic idea persisted, however, as Confederate desperation intensified. And in early 1865—truly the 11th hour, long past the point where it could have had any effect—the Confederate Congress authorized the first feeble steps for slave recruitment. Within a few weeks, the Union had triumphed.

At Franklin on November 30, 1864, Cleburne correctly judged General John B. Hood's assault plan as foolhardy but followed orders, exposing himself to maximum danger as the charge proceeded. His troops momentarily breached the Union line but were thrown back. Cleburne died while charging on foot after his horse was shot out from under him. His body was found plundered, without boots, watch or sword. He deserved far better. Then again, there were so many others of whom you could say that—on any side, in any war.

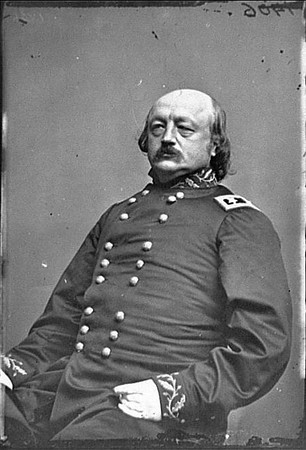

Portrait of General Cleburne. (Courtesy:

Library of Congress)

Three tumultuous years later, Cleburne figured in a quiet but very telling episode of the war. Recognizing the South's great manpower disadvantage and the urgent need to address it, Cleburne proposed to General Joseph Johnston and the rest of the Army of Tennessee's leadership that the South begin freeing slaves in return for their enlistment in the Confederate forces. A crucial passage of his address reveals both his knowledge of history and his blindness to what he was up against:

Satisfy the negro that if he faithfully adheres to our standard during the war he shall receive his freedom and that of his race ... and we change the race from a dreaded weakness to a position of strength.

Will the slaves fight? The helots of Sparta stood their masters good stead in battle. In the great sea fight of Lepanto where the Christians checked forever the spread of Mohammedanism over Europe, the galley slaves of portions of the fleet were promised freedom, and called on to fight at a critical moment of the battle. They fought well, and civilization owes much to those brave galley slaves ... the experience of this war has been so far that half-trained negroes have fought as bravely as many other half-trained Yankees.

It is said that slavery is all we are fighting for, and if we give it up we give up all. Even if this were true, which we deny, slavery is not all our enemies are fighting for. It is merely the pretense to establish sectional superiority and a more centralized form of government, and to deprive us of our rights and liberties.

Born and raised in another country and not arriving in the South till early manhood, Cleburne had never grasped how fundamental slavery actually was to the war and to his adopted region, even though it was the threat to slavery's spread that had triggered secession in the first place. (In the research for my novel Lucifer's Drum, one thing was clear: slavery imbued the pre-war years like no other issue. Nothing else came close.) The other generals listened quietly and respectfully, but Johnston was reportedly shocked. And—no surprise—Cleburne's proposal was not discussed, let alone acted upon. The basic idea persisted, however, as Confederate desperation intensified. And in early 1865—truly the 11th hour, long past the point where it could have had any effect—the Confederate Congress authorized the first feeble steps for slave recruitment. Within a few weeks, the Union had triumphed.

At Franklin on November 30, 1864, Cleburne correctly judged General John B. Hood's assault plan as foolhardy but followed orders, exposing himself to maximum danger as the charge proceeded. His troops momentarily breached the Union line but were thrown back. Cleburne died while charging on foot after his horse was shot out from under him. His body was found plundered, without boots, watch or sword. He deserved far better. Then again, there were so many others of whom you could say that—on any side, in any war.

Portrait of General Cleburne. (Courtesy:

Library of Congress)

Published on December 06, 2014 16:29

•

Tags:

battle-of-franklin, civil-war, lucifer-s-drum, patrick-cleburne

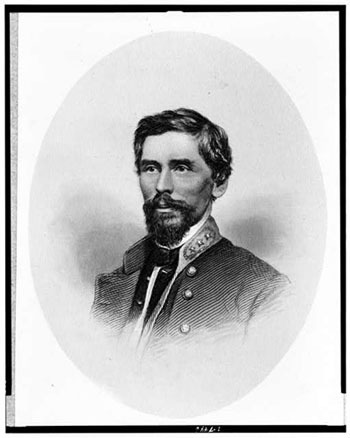

The Copperheads

In the opening chapter of my novel Lucifer's Drum (which I hope to post here presently), the hack newspaper publisher Gideon Van Gilder meets an especially unpleasant end. Van Gilder is a Copperhead, or "Peace Democrat"—one of that loud Northern political faction opposed to Lincoln, the Draft and Emancipation. Most Copperheads favored preservation of the Union but proclaimed the right of the Southern and border states to maintain slavery. And they opposed black advancement on principle, whether free or slave, portraying the white majority as besieged by evil forces. They identified as Democrats and strongly influenced the direction of that party, whose 1864 presidential platform was wholly Copperhead. Still, it has to be stated that many thousands of non-Copperhead Democrats ("War Democrats") fought in the federal ranks.

The name came about as an epithet, when Republicans and Union loyalists in general compared these dissenters to venomous snakes. As with many such movements, supporters reacted by taking the name as a badge of honor—quite literally, in this case, cutting the Liberty symbol from copper pennies and proudly wearing them. They were strongest in areas just north of the Ohio River and in urban ethnic neighborhoods. Anyone who thinks that today's level of political vituperation is unmatched should check out the editorial commentary (and the cartoons) from Copperhead newspapers, especially during the '64 election season. The editor of Wisconsin's LaCrosse Democrat, Marcus "Brick" Pomeroy, branded Lincoln "fungus from the corrupt womb of bigotry and fanaticism . . . a worse tyrant and more inhuman butcher than has existed since the days of Nero." Pomeroy declared that anyone who voted for the President was "a traitor and murderer," and that "if he is elected to misgovern for another four years, we trust some bold hand will pierce his heart with dagger point for the public good." (As is often the case in times of civil tumult, men like Pomeroy defined treason and fanaticism as anything short of their own views—practically a textbook definition of true fanaticism.)

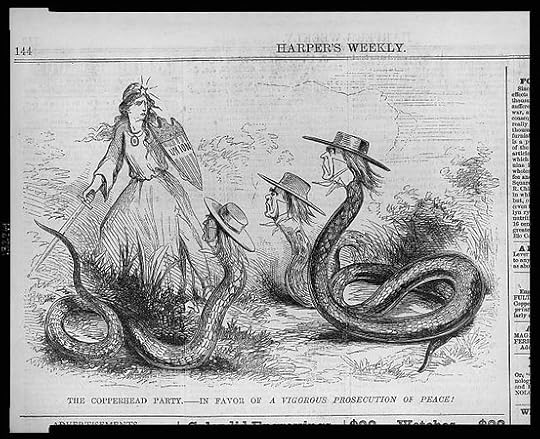

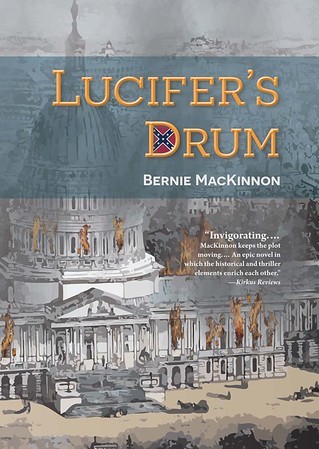

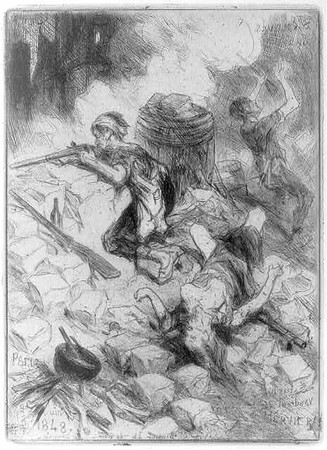

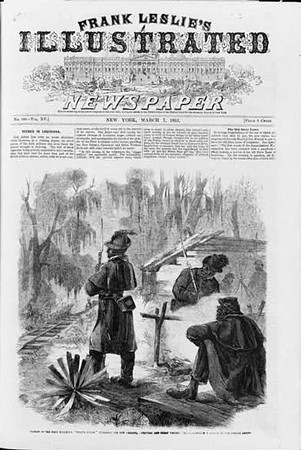

Anti-Copperhead cartoon, February 1863. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

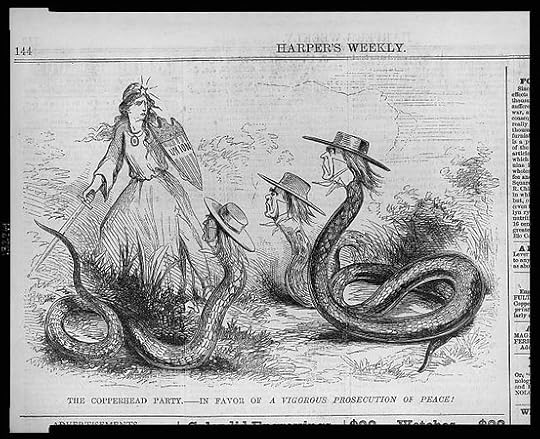

In New York, the official Catholic paper The Metropolitan Record championed draft resistance and helped ignite the July 1863 riots, still the bloodiest such event in U.S. history. Largely Irish immigrant mobs lynched a number of black men in the street and burned black-owned businesses. They also burned and looted the Colored Orphan's Asylum, whose terrified residents (233 children plus staff) had to be shepherded to safety by police. Many of the troops called in to quell the riots had fought at Gettysburg just two weeks earlier, arriving exhausted and no doubt disoriented by the scorched urban setting. (Gideon Van Gilder is depicted as having played a similar role in inciting this mass violence.) The editor of The Record, John Mullaly, was arrested a year later for his anti-draft activities. For the most part, however, Union authorities had to put up with high-profile Copperheads like New York's mayor and later congressman Fernando Wood, who once proposed that the city secede and thereby maintain its lucrative cotton trade with the South. (Generally speaking, it has always seemed to me that where money goes, heartfelt conviction follows.)

The core of the Copperhead movement grew from The Knights Of The Golden Circle, a pro-slavery and pro-expansionist secret society formed in the 1850's. During the war it changed its name to The Order Of American Knights and then The Order Of The Sons of Liberty, headed by the Copperheads' most prominent spokesman Clement L. Vallandigham. Given the thrill of secrecy and the sense of their own historic role, the Knights and their successors tended toward the grandiose, calling their branches "castles" and sometimes using secret handshakes. (The Ku Klux Klan would later take this sort of stuff to unexplored heights.)

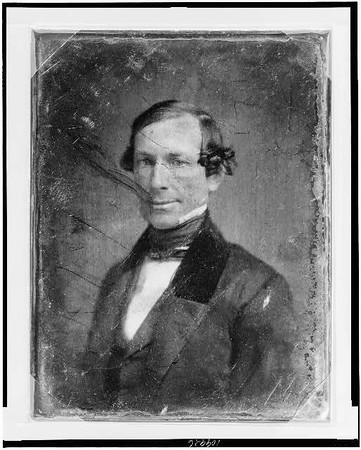

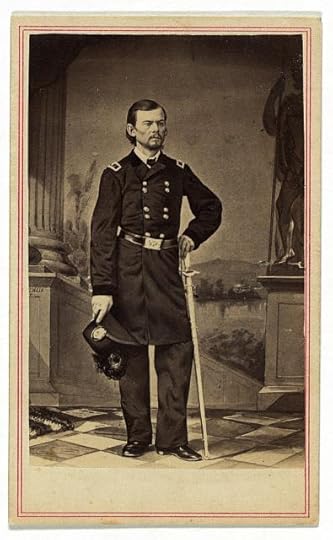

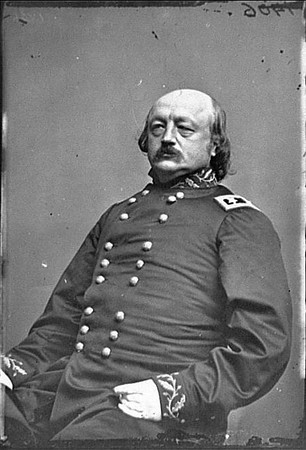

Fernando Wood, Mayor of New York City (1855-58,

1860-62), pro-Confederate and post-war U.S. Congressman.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

The Copperheads' fortunes ebbed and flowed along with that of the Union military cause, but reached their high-water mark in '64. What effectiveness they had evaporated on Sept. 2, when the fall of Atlanta made eventual Union victory look certain. Shortly before this, the Democrats had nominated George B. McClellan for president; however much McClellan despised Lincoln, who had sacked him as commanding general in the East, he did not embrace the Copperheads—contradicting the platform on which he supposedly ran and leaving his candidacy hamstrung. Among the Copperheads, only a minority were radical and nervy enough to actually participate in anti-Union schemes, such as encouraging soldiers to desert. And it is probably true that the Republicans exaggerated the Copperhead threat for political gain. Yet movement leaders like Harrison H. Dodd did in fact advocate the violent overthrow of certain state governments. Dodd and others were implicated in a plot to help Confederate prisoners escape from a POW camp in Indiana—and when federal authorities foiled it and made arrests, the evidence was compelling. Several Copperheads were sentenced to hang, but the Supreme Court eventually freed them after deciding that they should have had a civil and not a military trial.

I can't end this without a quick focus on Clement Vallandigham. He was a two-term Ohio congressman who blamed the war on the Abolition movement and railed against Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus. By the time he was voted out of office, he was the acknowledged leader of the Copperheads. Back in Ohio, he confronted General Ambrose E. Burnside's ham-fisted General Order No. 38, which mandated arrest for anyone expressing Confederate sympathies. (Burnside had acted on this when he shut down the pro-Copperhead Chicago Times, only to have Lincoln reverse the ban as soon as he heard of it.) Vallandigham was arrested under this order in May 1863 and sentenced to prison for the duration of the war. Facing loud protests from Democrats, however, Lincoln altered the sentence to banishment behind Confederate lines.

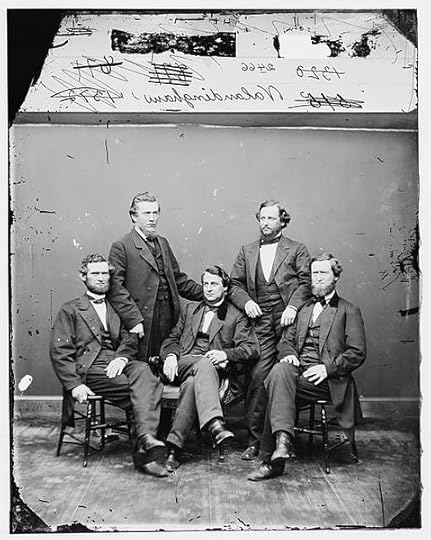

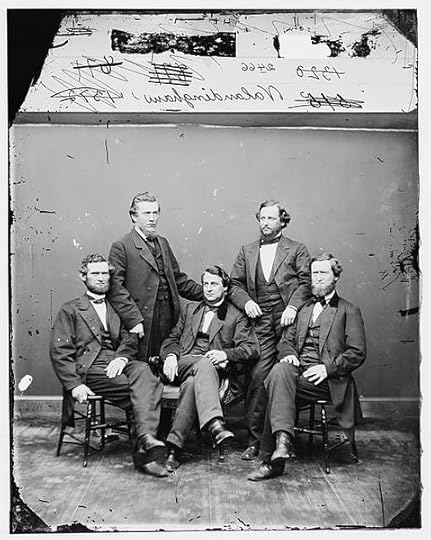

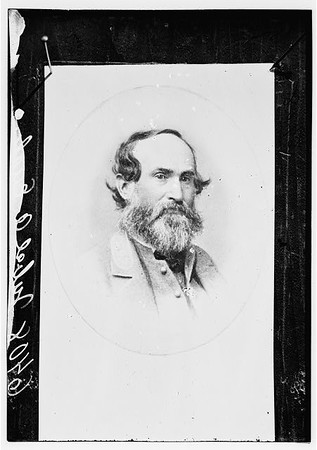

Clement Vallandigham (seated center) with other prominent

Copperheads, circa 1865. Several years later, he would accidentally

shoot himself. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In time, Vallandigham left the South by blockade runner and ended up in Windsor, Ontario, from which he ran in absentia for the Ohio governorship. His campaign was strong but unsuccessful. Meanwhile, in the same trial that convicted Harrison Dodd and other Copperheads, testimony implicated Vallandigham in a plan for armed revolt—the so-called Northwest Conspiracy. He had allegedly sought funds from a Confederate agent for this purpose, but the charge was never pressed. By now he had slipped back into the United States and was being monitored by Union authorities; Lincoln with his usual shrewdness declined to have Vallandigham arrested again and made a martyr. Vallandigham even attended the Democatic convention as a delegate in Chicago. Despite strong disagreements with McClellan, he would have been named Secretary of War had Little Mac not been crushed at the polls that autumn.

After the war, Vallandigham ran losing campaigns for senator and congressman before resuming his law practice. He opposed black suffrage and anything hinting at racial equality but then endorsed the Democrats' "New Departure" policy, which basically discouraged all public mention of the war. In Lebanon, Ohio in June, 1871, he took up the case of Thomas McGehan, who was charged with shooting another man in a barroom brawl. At the Golden Lamb Inn, Vallandigham sought to demonstrate for fellow defense lawyers how the victim might have accidentally shot himself during the melee. Picking up a pistol he thought to be unloaded—but was not—Vallandigham pocketed the weapon but snagged it on his clothes, shooting himself in the stomach. He died the next day, aged 50, expressing faith in the Presbyterian concept of predestination. Needless to say, Thomas McGehan got off—only to be shot dead in another brawl four years later. Say what you want about Vallandigham's political beliefs—has any attorney ever gone quite so above and beyond for his client? And at least his death wasn't as bad as Van Gilder's.

The name came about as an epithet, when Republicans and Union loyalists in general compared these dissenters to venomous snakes. As with many such movements, supporters reacted by taking the name as a badge of honor—quite literally, in this case, cutting the Liberty symbol from copper pennies and proudly wearing them. They were strongest in areas just north of the Ohio River and in urban ethnic neighborhoods. Anyone who thinks that today's level of political vituperation is unmatched should check out the editorial commentary (and the cartoons) from Copperhead newspapers, especially during the '64 election season. The editor of Wisconsin's LaCrosse Democrat, Marcus "Brick" Pomeroy, branded Lincoln "fungus from the corrupt womb of bigotry and fanaticism . . . a worse tyrant and more inhuman butcher than has existed since the days of Nero." Pomeroy declared that anyone who voted for the President was "a traitor and murderer," and that "if he is elected to misgovern for another four years, we trust some bold hand will pierce his heart with dagger point for the public good." (As is often the case in times of civil tumult, men like Pomeroy defined treason and fanaticism as anything short of their own views—practically a textbook definition of true fanaticism.)

Anti-Copperhead cartoon, February 1863. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In New York, the official Catholic paper The Metropolitan Record championed draft resistance and helped ignite the July 1863 riots, still the bloodiest such event in U.S. history. Largely Irish immigrant mobs lynched a number of black men in the street and burned black-owned businesses. They also burned and looted the Colored Orphan's Asylum, whose terrified residents (233 children plus staff) had to be shepherded to safety by police. Many of the troops called in to quell the riots had fought at Gettysburg just two weeks earlier, arriving exhausted and no doubt disoriented by the scorched urban setting. (Gideon Van Gilder is depicted as having played a similar role in inciting this mass violence.) The editor of The Record, John Mullaly, was arrested a year later for his anti-draft activities. For the most part, however, Union authorities had to put up with high-profile Copperheads like New York's mayor and later congressman Fernando Wood, who once proposed that the city secede and thereby maintain its lucrative cotton trade with the South. (Generally speaking, it has always seemed to me that where money goes, heartfelt conviction follows.)

The core of the Copperhead movement grew from The Knights Of The Golden Circle, a pro-slavery and pro-expansionist secret society formed in the 1850's. During the war it changed its name to The Order Of American Knights and then The Order Of The Sons of Liberty, headed by the Copperheads' most prominent spokesman Clement L. Vallandigham. Given the thrill of secrecy and the sense of their own historic role, the Knights and their successors tended toward the grandiose, calling their branches "castles" and sometimes using secret handshakes. (The Ku Klux Klan would later take this sort of stuff to unexplored heights.)

Fernando Wood, Mayor of New York City (1855-58,

1860-62), pro-Confederate and post-war U.S. Congressman.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

The Copperheads' fortunes ebbed and flowed along with that of the Union military cause, but reached their high-water mark in '64. What effectiveness they had evaporated on Sept. 2, when the fall of Atlanta made eventual Union victory look certain. Shortly before this, the Democrats had nominated George B. McClellan for president; however much McClellan despised Lincoln, who had sacked him as commanding general in the East, he did not embrace the Copperheads—contradicting the platform on which he supposedly ran and leaving his candidacy hamstrung. Among the Copperheads, only a minority were radical and nervy enough to actually participate in anti-Union schemes, such as encouraging soldiers to desert. And it is probably true that the Republicans exaggerated the Copperhead threat for political gain. Yet movement leaders like Harrison H. Dodd did in fact advocate the violent overthrow of certain state governments. Dodd and others were implicated in a plot to help Confederate prisoners escape from a POW camp in Indiana—and when federal authorities foiled it and made arrests, the evidence was compelling. Several Copperheads were sentenced to hang, but the Supreme Court eventually freed them after deciding that they should have had a civil and not a military trial.

I can't end this without a quick focus on Clement Vallandigham. He was a two-term Ohio congressman who blamed the war on the Abolition movement and railed against Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus. By the time he was voted out of office, he was the acknowledged leader of the Copperheads. Back in Ohio, he confronted General Ambrose E. Burnside's ham-fisted General Order No. 38, which mandated arrest for anyone expressing Confederate sympathies. (Burnside had acted on this when he shut down the pro-Copperhead Chicago Times, only to have Lincoln reverse the ban as soon as he heard of it.) Vallandigham was arrested under this order in May 1863 and sentenced to prison for the duration of the war. Facing loud protests from Democrats, however, Lincoln altered the sentence to banishment behind Confederate lines.

Clement Vallandigham (seated center) with other prominent

Copperheads, circa 1865. Several years later, he would accidentally

shoot himself. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In time, Vallandigham left the South by blockade runner and ended up in Windsor, Ontario, from which he ran in absentia for the Ohio governorship. His campaign was strong but unsuccessful. Meanwhile, in the same trial that convicted Harrison Dodd and other Copperheads, testimony implicated Vallandigham in a plan for armed revolt—the so-called Northwest Conspiracy. He had allegedly sought funds from a Confederate agent for this purpose, but the charge was never pressed. By now he had slipped back into the United States and was being monitored by Union authorities; Lincoln with his usual shrewdness declined to have Vallandigham arrested again and made a martyr. Vallandigham even attended the Democatic convention as a delegate in Chicago. Despite strong disagreements with McClellan, he would have been named Secretary of War had Little Mac not been crushed at the polls that autumn.

After the war, Vallandigham ran losing campaigns for senator and congressman before resuming his law practice. He opposed black suffrage and anything hinting at racial equality but then endorsed the Democrats' "New Departure" policy, which basically discouraged all public mention of the war. In Lebanon, Ohio in June, 1871, he took up the case of Thomas McGehan, who was charged with shooting another man in a barroom brawl. At the Golden Lamb Inn, Vallandigham sought to demonstrate for fellow defense lawyers how the victim might have accidentally shot himself during the melee. Picking up a pistol he thought to be unloaded—but was not—Vallandigham pocketed the weapon but snagged it on his clothes, shooting himself in the stomach. He died the next day, aged 50, expressing faith in the Presbyterian concept of predestination. Needless to say, Thomas McGehan got off—only to be shot dead in another brawl four years later. Say what you want about Vallandigham's political beliefs—has any attorney ever gone quite so above and beyond for his client? And at least his death wasn't as bad as Van Gilder's.

Published on February 07, 2015 13:06

•

Tags:

civil-war, copperheads, knights-of-the-golden-circle, lucifer-s-drum, peace-democrats, vallandigham

My Lost Prologue

When a novel is already fat, its author would do well *not* to include a prologue, those leisurely opening pages that give readers a bird's-eye view of time and place. Some works of fiction benefit from a prologue—a short one, preferably—but most do fine without one. I confess that when I open a book and see one, my heart sinks a little, since it means a delay of action. Still, my novel Lucifer's Drum once had a prologue. The story did seem to call for it at the time—a panoramic update, a hold-onto-your-hat overture as the Civil War lurched into its last and most horrific year.

But as I wrestled with a big story that threatened to become too big, those pages proved highly expendable. I put a lot into them, though, and am therefore posting them today, the 150th anniversary of Richmond's capture. The Confederate capital's fall was the culmination of events that started eleven months earlier, when Grant and Lee began their death struggle and the blood tide crested. All of which I tried to evoke here:

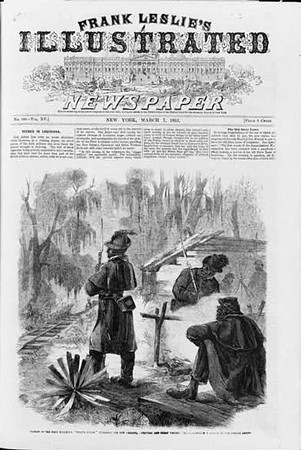

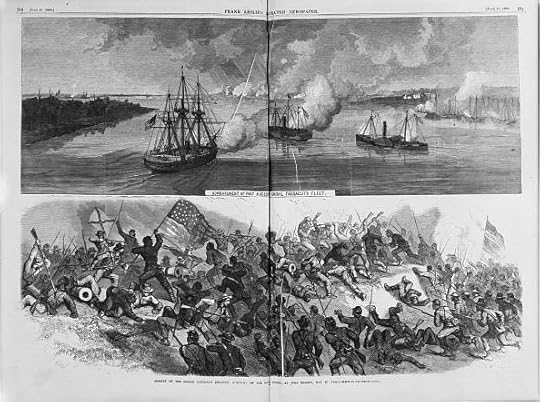

PROLOGUE: SPRING, 1864

Deep into the war, survivors found themselves looking back to the beginning. Each had a sudden, private urge to reclaim that moment, now so distant, before it too was lost. Few spoke of it, so memories groped in silence. And the more they remembered, the stranger they felt, realizing that madness and innocence are sometimes impossible to tell apart.

It had begun in fever and delirium, in shrill song and deafening cheer. With an eruption of bands and banners, with ornate cavalry and shiny black cannon rattling down the avenues. With brave, endless volunteer columns trying to look smart and march straight for the weeping girls. And with speeches: On to Richmond, God points the Way, Victory before Christmas, let him whose heart is faint turn back. A Union forever. Now, with the roar of Gettysburg not a year past, a generation of ghosts thronged the woods, hills and fields from Pennsylvania to the Trans-Mississippi.

People had at first been the manifest agents of conflict, actively willing events toward a vast and inescapable collision. Responding to the scope of the hour, they appeared somehow magnified to themselves and one another, their deeds and assertions grand as never before. Noble resolve covered everything in hues of gold, even the first homeward coffins and the humble tents dotting the hillsides. Minds, bodies, convictions—these, overnight, were galvanized for a single severe purpose, pushing and not driven, sweeping and not swept to the forward lines.

Yet at some otherworldly juncture, as the cemeteries grew and then spilled over, that purpose left the realm of human design—gone into the earth, into the smoky sky, somewhere else. A war launched in righteous certitude, by humans, had become a colossal organism that thundered of its own power. It was a creature undreamed of. Deaf to protest and opinion, it dwarfed the legions and drowned out the bands, banishing the golden light forever. Amid its heaving, unstoppable shocks, men cowered and scrambled. Armies were its beasts of burden, battalions food for its maw, each soldier a windblown seed. People had in fact never looked so small.

Deep inside the din, speeches could still be heard—Abolitionists, Constitutionalists, War Democrats, centrist Republicans and Copperheads were no less strident. But invocations of the Deity were more frequent, as if the speakers knew instinctively that mortal arguments alone would rally no one, would sound shriveled and obscene to ears grown hard. Street conversations were more clipped, more distracted, and one might note a cast of shadow in another's eye. Yesterday's expressions and sentiments remained like stumps in a hurricane and people clung to them, grasping at the same time for new certitudes. They tried to predict. They tried to envision the end. But in the fury of this storm, no eye could penetrate. And at solitary moments, all but the most flinty and partisan of souls wondered what it was they had done, what had been done, what they would do now. In the Executive Mansion, a gaunt President wondered this continually.

The opposing forces had hibernated through the winter. Greatcoated sentries leaned on their rifles and gazed across the river. For its part, the population marked time and kept busy. Women rolled bandages when they weren't cooking or mending. Children played, did chores or school work and said their prayers. But at night, clocks struck louder upon the ear. Lying awake in barracks, or in feather beds, people listened to the wind moan prophecies they could not decipher.

By daylight, many spoken prophecies centered on Ulysses S. Grant. The general's air of scruffy competence heartened Northerners, who had seen their boast trampled on too many fields. Betrayed by their own optimism, gorged sick on debate and mistrustful of appearances, they welcomed a man who was plain in speech, manner and appearance but a virtuoso in warfare. Grant came east with his record of western victories and did not boast. He went to work planning his spring campaign and assembling one of the largest forces in world history. In early May, chewing his cigar, he watched his great army cross the Rapidan into the Wilderness, into the scrub oak and blooming dogwood. Into Confederate hellfire. On the second night, with flames racing through dry undergrowth, the woods torn by the screams of wounded unable to crawl fast enough, Grant excused himself from his staff, entered his tent and wept.

What followed was armed combat as the world had never seen it. Grant did not withdraw but sent his blue leviathan hulking southeastward. Robert E. Lee's gray one followed, and the antagonists remained in daily, bludgeoning contact as the month wore on. Along with the dead and wounded, men returned wide-eyed and gibbering from the front, struck with a madness yet unnamed. Crows and wild pigs fed upon the dead before they could be carted off, and as accounts of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor bled into newsprint, the casualty rosters unfurled. Memorial portraits decorated parlors draped in black. Embalmers put up their signs. Diarists sat with nibs poised above blank pages. In school and church, children's attention strayed as they tried to picture that paradise to which their martyred fathers had gone.

June's arrival found towns and cities in a growing state of shock. Draftees fled or scraped up the $300 substitute fee. "Bounty-jumpers" prospered by enlisting for cash bonuses, deserting, then repeating the process. Urging calm, local pro-Union leaders gave pallid homilies about honoring the dead through renewed commitment.

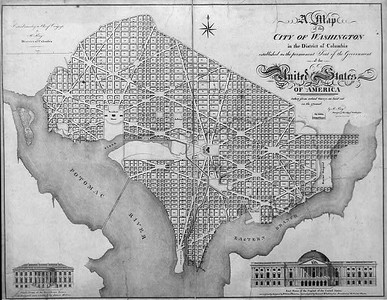

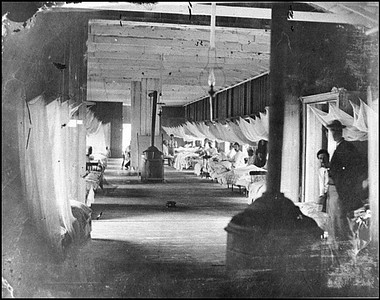

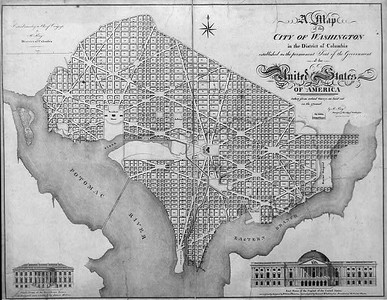

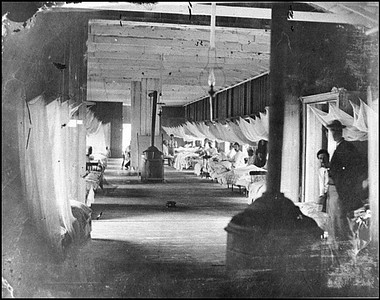

Washington, D.C., had more experience than most in the practice of calm. While the rest of the North sank from frenzied hope to bitter dismay, Washington sought to emulate its own statues and not flinch. It took reassurance from its grand, unfinished government buildings and its unrivaled ring of forts. It kept about its business despite daily boatloads of wounded at the Sixth Street wharf. Wounded languished in hospitals, converted churches and private homes; in hotels, warehouses and fraternal lodges. But the summer heat swelled, dulling alarm and bringing out something of the city's languid Southern character. Much less of that character survived these days. For Washington, the firing on Fort Sumter had signaled not just war, not just the swarming encampments, but also an influx of merchants and poor folk. War meant business for shops, markets, taverns, theaters, hotels, brothels and livery stables, and these had multiplied while troops paraded and battles quaked upriver or to the south. Confederate spies moved within the burgeoning population, drawing support from the city's strong pro-Southern element, passing information despite the War Department's draconian measures. Ridiculously young for its size, ridiculously divided and unready for its role as the Union's martial crux, Washington strained to meet the challenge of its transfiguration. But while it aped the smugness of older, greater cities, foreign diplomats eyed its imperial pillars and snickered. Away from the fashionable districts, shanties huddled along brawling, mud-holed streets where police chased thieves and battled ruffian gangs.

Still, as the murderous tumult continued elsewhere, the capital's summer heat slowed everything. It conjured flies from the fetid marsh and aqueduct and from the government slaughter pens. To many, a worse stench emanated from the Capitol Building, where Copperhead congressmen declared Grant a mass murderer and cried for peace while Republicans cried for censure. All looked forward to the summer recess, though it would not be much of one. A presidential election loomed with the promise of more dirt, more acrimony than the campaigns of 1860, and the parties had to marshal their forces. It was widely expected that the Lincoln administration would fall. Of the last eight Presidents, none had seen a second term, claimed either by death or factional strife.

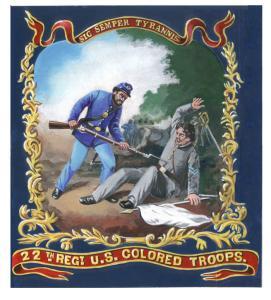

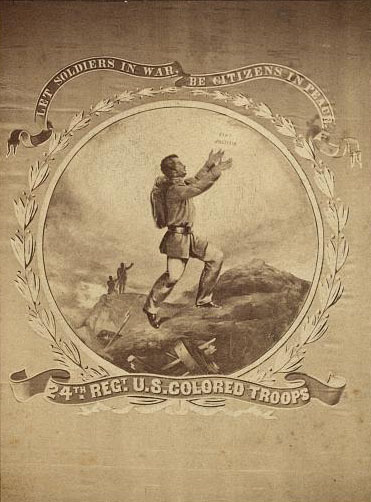

Increasingly, dark-skinned refugees turned up—bedgraggled men, women and children liberated in Grant's wake and drawn by the capital's safety. "Contrabands," the authorities called them, ranking them with captured livestock and cotton bales. Up from the Virginia fields they came, stunned and hopeful, to scrounge some kind of living, to gaze at the monuments and at the white citizenry who glanced and kept walking. Some were taken in by the Freedman's Aid Society or the quietly industrious community of free blacks. Others slept on the street or in woodlots, or settled in shack towns along the city's northern fringe. Many of the men soon left to join their lettered, Northern-raised brethren in Negro regiments. To any white who cared to ask or listen, the ex-slaves would evince no doubt of the war's mystical dimension. They might show a ragged scar or two, indicating time spent under the devil's will and a sure preference for God's, however terrible.

But everyone knew that the story was being blasted and re-written even as they breathed. The imponderable creature roared louder than ever, taking all in its reach. On clear days near the capital's outskirts, one could catch the far-off rumble of shelling. And certain people sensed that motives had sunk beneath the level of language, beneath the phrases about God, Honor, Freedom and Country, to the darkest region of the heart.

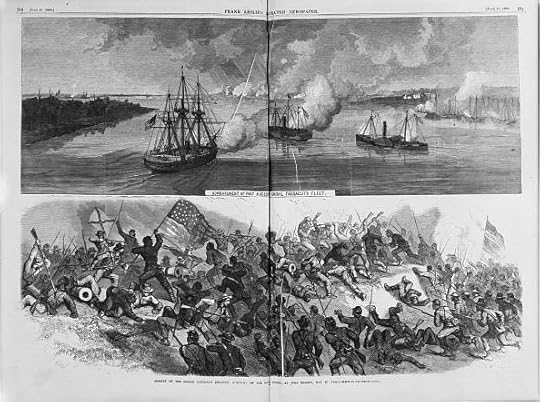

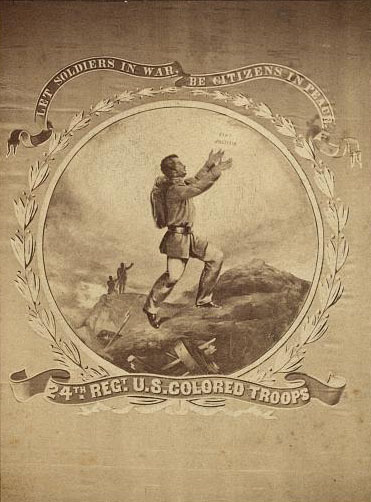

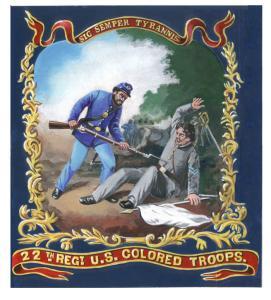

(Photos Courtesy: Library of Congress)

But as I wrestled with a big story that threatened to become too big, those pages proved highly expendable. I put a lot into them, though, and am therefore posting them today, the 150th anniversary of Richmond's capture. The Confederate capital's fall was the culmination of events that started eleven months earlier, when Grant and Lee began their death struggle and the blood tide crested. All of which I tried to evoke here:

PROLOGUE: SPRING, 1864

Deep into the war, survivors found themselves looking back to the beginning. Each had a sudden, private urge to reclaim that moment, now so distant, before it too was lost. Few spoke of it, so memories groped in silence. And the more they remembered, the stranger they felt, realizing that madness and innocence are sometimes impossible to tell apart.

It had begun in fever and delirium, in shrill song and deafening cheer. With an eruption of bands and banners, with ornate cavalry and shiny black cannon rattling down the avenues. With brave, endless volunteer columns trying to look smart and march straight for the weeping girls. And with speeches: On to Richmond, God points the Way, Victory before Christmas, let him whose heart is faint turn back. A Union forever. Now, with the roar of Gettysburg not a year past, a generation of ghosts thronged the woods, hills and fields from Pennsylvania to the Trans-Mississippi.

People had at first been the manifest agents of conflict, actively willing events toward a vast and inescapable collision. Responding to the scope of the hour, they appeared somehow magnified to themselves and one another, their deeds and assertions grand as never before. Noble resolve covered everything in hues of gold, even the first homeward coffins and the humble tents dotting the hillsides. Minds, bodies, convictions—these, overnight, were galvanized for a single severe purpose, pushing and not driven, sweeping and not swept to the forward lines.

Yet at some otherworldly juncture, as the cemeteries grew and then spilled over, that purpose left the realm of human design—gone into the earth, into the smoky sky, somewhere else. A war launched in righteous certitude, by humans, had become a colossal organism that thundered of its own power. It was a creature undreamed of. Deaf to protest and opinion, it dwarfed the legions and drowned out the bands, banishing the golden light forever. Amid its heaving, unstoppable shocks, men cowered and scrambled. Armies were its beasts of burden, battalions food for its maw, each soldier a windblown seed. People had in fact never looked so small.

Deep inside the din, speeches could still be heard—Abolitionists, Constitutionalists, War Democrats, centrist Republicans and Copperheads were no less strident. But invocations of the Deity were more frequent, as if the speakers knew instinctively that mortal arguments alone would rally no one, would sound shriveled and obscene to ears grown hard. Street conversations were more clipped, more distracted, and one might note a cast of shadow in another's eye. Yesterday's expressions and sentiments remained like stumps in a hurricane and people clung to them, grasping at the same time for new certitudes. They tried to predict. They tried to envision the end. But in the fury of this storm, no eye could penetrate. And at solitary moments, all but the most flinty and partisan of souls wondered what it was they had done, what had been done, what they would do now. In the Executive Mansion, a gaunt President wondered this continually.

The opposing forces had hibernated through the winter. Greatcoated sentries leaned on their rifles and gazed across the river. For its part, the population marked time and kept busy. Women rolled bandages when they weren't cooking or mending. Children played, did chores or school work and said their prayers. But at night, clocks struck louder upon the ear. Lying awake in barracks, or in feather beds, people listened to the wind moan prophecies they could not decipher.

By daylight, many spoken prophecies centered on Ulysses S. Grant. The general's air of scruffy competence heartened Northerners, who had seen their boast trampled on too many fields. Betrayed by their own optimism, gorged sick on debate and mistrustful of appearances, they welcomed a man who was plain in speech, manner and appearance but a virtuoso in warfare. Grant came east with his record of western victories and did not boast. He went to work planning his spring campaign and assembling one of the largest forces in world history. In early May, chewing his cigar, he watched his great army cross the Rapidan into the Wilderness, into the scrub oak and blooming dogwood. Into Confederate hellfire. On the second night, with flames racing through dry undergrowth, the woods torn by the screams of wounded unable to crawl fast enough, Grant excused himself from his staff, entered his tent and wept.

What followed was armed combat as the world had never seen it. Grant did not withdraw but sent his blue leviathan hulking southeastward. Robert E. Lee's gray one followed, and the antagonists remained in daily, bludgeoning contact as the month wore on. Along with the dead and wounded, men returned wide-eyed and gibbering from the front, struck with a madness yet unnamed. Crows and wild pigs fed upon the dead before they could be carted off, and as accounts of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor bled into newsprint, the casualty rosters unfurled. Memorial portraits decorated parlors draped in black. Embalmers put up their signs. Diarists sat with nibs poised above blank pages. In school and church, children's attention strayed as they tried to picture that paradise to which their martyred fathers had gone.

June's arrival found towns and cities in a growing state of shock. Draftees fled or scraped up the $300 substitute fee. "Bounty-jumpers" prospered by enlisting for cash bonuses, deserting, then repeating the process. Urging calm, local pro-Union leaders gave pallid homilies about honoring the dead through renewed commitment.

Washington, D.C., had more experience than most in the practice of calm. While the rest of the North sank from frenzied hope to bitter dismay, Washington sought to emulate its own statues and not flinch. It took reassurance from its grand, unfinished government buildings and its unrivaled ring of forts. It kept about its business despite daily boatloads of wounded at the Sixth Street wharf. Wounded languished in hospitals, converted churches and private homes; in hotels, warehouses and fraternal lodges. But the summer heat swelled, dulling alarm and bringing out something of the city's languid Southern character. Much less of that character survived these days. For Washington, the firing on Fort Sumter had signaled not just war, not just the swarming encampments, but also an influx of merchants and poor folk. War meant business for shops, markets, taverns, theaters, hotels, brothels and livery stables, and these had multiplied while troops paraded and battles quaked upriver or to the south. Confederate spies moved within the burgeoning population, drawing support from the city's strong pro-Southern element, passing information despite the War Department's draconian measures. Ridiculously young for its size, ridiculously divided and unready for its role as the Union's martial crux, Washington strained to meet the challenge of its transfiguration. But while it aped the smugness of older, greater cities, foreign diplomats eyed its imperial pillars and snickered. Away from the fashionable districts, shanties huddled along brawling, mud-holed streets where police chased thieves and battled ruffian gangs.

Still, as the murderous tumult continued elsewhere, the capital's summer heat slowed everything. It conjured flies from the fetid marsh and aqueduct and from the government slaughter pens. To many, a worse stench emanated from the Capitol Building, where Copperhead congressmen declared Grant a mass murderer and cried for peace while Republicans cried for censure. All looked forward to the summer recess, though it would not be much of one. A presidential election loomed with the promise of more dirt, more acrimony than the campaigns of 1860, and the parties had to marshal their forces. It was widely expected that the Lincoln administration would fall. Of the last eight Presidents, none had seen a second term, claimed either by death or factional strife.

Increasingly, dark-skinned refugees turned up—bedgraggled men, women and children liberated in Grant's wake and drawn by the capital's safety. "Contrabands," the authorities called them, ranking them with captured livestock and cotton bales. Up from the Virginia fields they came, stunned and hopeful, to scrounge some kind of living, to gaze at the monuments and at the white citizenry who glanced and kept walking. Some were taken in by the Freedman's Aid Society or the quietly industrious community of free blacks. Others slept on the street or in woodlots, or settled in shack towns along the city's northern fringe. Many of the men soon left to join their lettered, Northern-raised brethren in Negro regiments. To any white who cared to ask or listen, the ex-slaves would evince no doubt of the war's mystical dimension. They might show a ragged scar or two, indicating time spent under the devil's will and a sure preference for God's, however terrible.

But everyone knew that the story was being blasted and re-written even as they breathed. The imponderable creature roared louder than ever, taking all in its reach. On clear days near the capital's outskirts, one could catch the far-off rumble of shelling. And certain people sensed that motives had sunk beneath the level of language, beneath the phrases about God, Honor, Freedom and Country, to the darkest region of the heart.

(Photos Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Published on April 03, 2015 21:38

•

Tags:

1864, civil-war, fall-of-richmond, lucifer-s-drum, prologue

"Blue As Hell's Brimstone!"

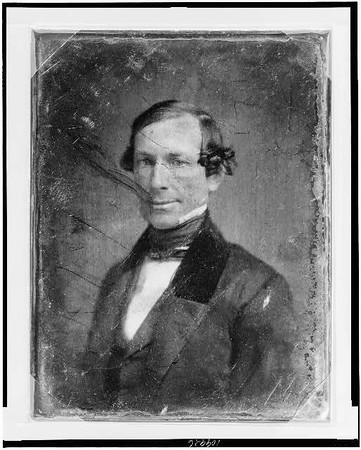

I can't spend the 150th anniversary of Appomattox without posting something. This time it concerns a historical figure who plays a minor but colorful role in my novel Lucifer's Drum, Henry Kyd Douglas. Douglas served as a trusted aide to Stonewall Jackson and later to Jubal Early. At Appomattox, where he was a brigade commander, his troops fired the last shots and were last to surrender.

Douglas hailed from Shepherdstown, Virginia (later West Virginia), though his family's home Ferry Hill stood across the Potomac, on the Maryland side. Enlisting as a Confederate private at the war's outbreak, the 22-year-old fledgling lawyer rose rapidly through the ranks and by mid-1862 was on Jackson's staff, participating in the Valley Campaign, Cedar Mountain, Second Manassas and Antietam. He filled the extra role of guide at Antietam, given his first-hand knowledge of the area. At Gettysburg he was captured and sent to the officers' prison camp at Johnson's Island, Ohio, but was freed by exchange in March, 1864. Lucifer's Drum depicts him as smart, daring and high-spirited, almost a surrogate son to his superior Jubal Early, whose mid-summer thrust down the Shenandoah brought them to the doorstep of Washington, D.C.

Many of the incidents and conversations in the novel are of course imaginary, informed by history but no more than that. One particular moment, however, is taken directly from the historical record. As Early gives orders for the Confederate host to withdraw from Washington's outskirts, following the Union counterattack, he stops to boast that they have "scared Abe Lincoln like hell." To which Douglas, then a major, responds, "Yes, General, but this afternoon when that Yankee line moved out against us, I think some other people were scared blue as hell's brimstone!" Reacting to his young aide's brash modesty, Early reportedly declared, "That's true, but it won't appear in history!" Early was no prophet.

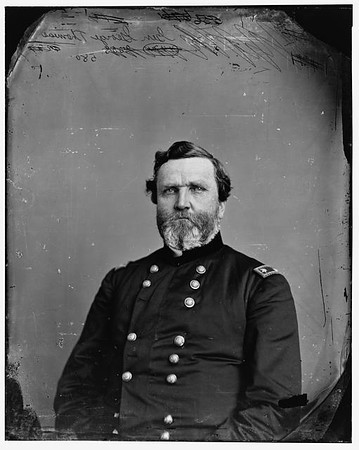

Henry Kyd Douglas, last to surrender

at Appomattox. (Courtesy: Library

of Congress)

Novels are by definition works of invention—but for historical ones, true events and true moments provide a mother lode of drama. Lucifer's Drum uses plenty of them: the solemn parade of Rebel troops past Stonewall Jackson's grave; the 4th of July picnic for the free black community of Washington, on the grounds of the President's House; Lincoln under fire on the parapet at Fort Stevens. Often, when you have researched these incidents, you are left feeling that only real life could have scripted them. Fiction pales.

Douglas saw action in nearly every Eastern campaign and survived six woundings. Varina Davis, wife of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, called Douglas, "with one exception, the handsomest man I ever met." After the war, he published his memoir I Rode With Stonewall, often cited as one of the most engaging and best-written of its kind, though not necessarily the most reliable. (You wouldn't think Douglas would have had to embellish, but it's a good bet that he did. Well, he definitely wasn't alone in that.)

Never marrying, he ended up a respected attorney in Hagerstown, Maryland, the very Unionist town that his Confederate brethren had shaken down for a "levy" during Early's Raid. Maybe its citizenry were more forgiving because of the mistake the Rebel cavalry had made on that occasion, misunderstanding Early's demand for $200,000 and snagging only $20,000 instead. History is plenty tragic, but once in a while it's funny.

Douglas hailed from Shepherdstown, Virginia (later West Virginia), though his family's home Ferry Hill stood across the Potomac, on the Maryland side. Enlisting as a Confederate private at the war's outbreak, the 22-year-old fledgling lawyer rose rapidly through the ranks and by mid-1862 was on Jackson's staff, participating in the Valley Campaign, Cedar Mountain, Second Manassas and Antietam. He filled the extra role of guide at Antietam, given his first-hand knowledge of the area. At Gettysburg he was captured and sent to the officers' prison camp at Johnson's Island, Ohio, but was freed by exchange in March, 1864. Lucifer's Drum depicts him as smart, daring and high-spirited, almost a surrogate son to his superior Jubal Early, whose mid-summer thrust down the Shenandoah brought them to the doorstep of Washington, D.C.

Many of the incidents and conversations in the novel are of course imaginary, informed by history but no more than that. One particular moment, however, is taken directly from the historical record. As Early gives orders for the Confederate host to withdraw from Washington's outskirts, following the Union counterattack, he stops to boast that they have "scared Abe Lincoln like hell." To which Douglas, then a major, responds, "Yes, General, but this afternoon when that Yankee line moved out against us, I think some other people were scared blue as hell's brimstone!" Reacting to his young aide's brash modesty, Early reportedly declared, "That's true, but it won't appear in history!" Early was no prophet.

Henry Kyd Douglas, last to surrender

at Appomattox. (Courtesy: Library

of Congress)

Novels are by definition works of invention—but for historical ones, true events and true moments provide a mother lode of drama. Lucifer's Drum uses plenty of them: the solemn parade of Rebel troops past Stonewall Jackson's grave; the 4th of July picnic for the free black community of Washington, on the grounds of the President's House; Lincoln under fire on the parapet at Fort Stevens. Often, when you have researched these incidents, you are left feeling that only real life could have scripted them. Fiction pales.

Douglas saw action in nearly every Eastern campaign and survived six woundings. Varina Davis, wife of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, called Douglas, "with one exception, the handsomest man I ever met." After the war, he published his memoir I Rode With Stonewall, often cited as one of the most engaging and best-written of its kind, though not necessarily the most reliable. (You wouldn't think Douglas would have had to embellish, but it's a good bet that he did. Well, he definitely wasn't alone in that.)

Never marrying, he ended up a respected attorney in Hagerstown, Maryland, the very Unionist town that his Confederate brethren had shaken down for a "levy" during Early's Raid. Maybe its citizenry were more forgiving because of the mistake the Rebel cavalry had made on that occasion, misunderstanding Early's demand for $200,000 and snagging only $20,000 instead. History is plenty tragic, but once in a while it's funny.

Published on April 09, 2015 13:42

•

Tags:

1864, appomattox, civil-war, early-s-raid, henry-kyd-douglas, lucifer-s-drum

Dark Road, June Night: It Begins

Lucifer's Drum starts its journey in the wee hours of June 6, 1864, on a lonely road in northern Virginia. So I am marking this particular June 6 by posting the novel's first chapter. Here the Copperhead (pro-Confederate) newspaper publisher Gideon Van Gilder is fleeing through the night, pursued by something terrible.

CHAPTER ONE

NORTHERN SHENANDOAH VALLEY

JUNE 6, 1864

Gideon Van Gilder had left his dignity far behind, like an expensive topcoat forgotten in haste. He did not mourn its loss—had not mourned it even at the last roadside inn, when he started awake and spied his stricken face in a shaving mirror. Now, huddled again inside the rocking coach, he could think only of escape. Escape—southward, southward by moon and carriage light, along this road so rough that it threatened to break the axles. Up the hill-haunted Shenandoah lay sanctuary, some haven behind the booming, gargantuan battle lines. Only there could he know rest once more. Rest, and perhaps the luxury of pride.

The lump of the derringer beneath his vest was small comfort–he had never fired a pistol in his life. At times in the jouncing blur of his journey, he had found himself gripping his cane between his knees like a talisman of dubious power. More frequently than ever he yelled at his hunchbacked coachman, calling him a sausage-eating monkey or a deformed German half-wit. The coachman said little.

Awaking from a fitful doze, Van Gilder realized that the coach’s rocking had ceased. He shuddered as he blinked out of the window into a mass of tall black shapes that hid the moon. He heard a ragged breathing sound. After a disoriented moment, he identified the sound as that of the horses and the obstruction as a stand of pine. He shifted to the other side and elbowed the door open. In the carriage lamp’s glow he discerned the misshapen form of the coachman. He was carrying two pails down an embankment, headed for the ripple of an unseen creek.

Van Gilder drew a breath to holler, but in the dark his voice came as a hushed rasp. “Kirschenbaum!”

Maintaining his balance on the slope, the coachman made an awkward turn. “Horses are tired, you makes them run all night. Tired like me, sir. I get vater.”

“Do it, then, imbecile! But no more stops!”

The hunched form started to turn away, then hesitated. “Herr Van Gilder?”

“Get the damned water!”

“We gets closer to the secesh.”

“Yes!” Van Gilder hissed “Yes—and I’ve paid you! Get the water!”

“I did not know I must take you five days and now all night. And we gets closer to the secesh.”

Though still hushed, Van Gilder’s voice began its climb toward full fury. “Fool! I know where we’re going! I’ve paid you!”

“You pay me more, I think.”

In the rippling stillness, one of the animals snorted. Van Gilder sputtered a curse. “Three dollars more, when we reach the place!”

“Ten.”

From the creek, a bullfrog let out a deep “bong” sound. Van Gilder thought of the derringer—wishing, thwarted. This time he spoke in just a murmur. “Ten, when we get there.”

“I thank you,” said the hunchback, who resumed his descent.

Dense with cricket noise, the warm, still air pressed in on Van Gilder, worsening his agitation. He took up his map, rattled it open and lit a match. In the match’s flutter he followed the black line of his route to the town of Strasburg, marked by a tight circle. Twenty-five miles to go, more or less. He blew out the match, folded the map and again peered outside.

“Kirschenbaum!” he called in a hoarse whisper.

From the embankment, the hunchback’s laboring form reappeared with the pails, slopping water. Kirschenbaum began watering the first pair of horses. When they got to Strasburg, Van Gilder thought, he would stick his derringer in the face of this insolent moron. Then he would drop a single coin at his feet and tell him to get out of his sight forever.

“Van Gilder!” came a deep-throated call.

Van Gilder jerked upright. For a crazed moment, he could neither move nor think nor breathe. Then, blindly, he began fumbling for his derringer.

“Don’t fret,” came the voice. “I am here to see that you pass safely through our lines.”

Van Gilder stopped pawing at his vest. Shaking, he leaned slowly out the side. He saw Kirschenbaum standing motionless, staring past the back of the coach. From that direction he heard a crunch of pebbles, very close. How—how could anyone have come upon them with such stealth? Leaning out farther, he forced his head to turn. Out of the gloom, the shape of a horse and rider emerged. The man wore a military cap, cape and double-breasted tunic, its brass buttons winking like sparks. With the oil running low, the lamps cast a meager halo about the coach—and as the stranger entered it, his uniform proved to be Union blue. He held a revolver and the reins in one hand, an extinguished lantern in the other.

Van Gilder gazed, open-mouthed as the intruder guided his mount forward and then halted–a bearded, powerful-looking officer, the right side of his face hidden by bandages. In an attitude of dutiful ease, he slouched in the saddle, his revolver held loosely away. His one visible eye peered down at Kirschenbaum, though it was Van Gilder whom he addressed:

“Major Henry Spruce, Army of the Potomac, currently on detached service. I am your official escort—to ensure that you make your rendezvous in Strasburg. That you do so without being fired upon by federal pickets, who perhaps know a traitor when they see one.”

There was something odd about the major’s low-in-the-throat intonation. Still gaping, Van Gilder fidgeted with the buttons of his coat. “How did you know . . . ?”

“For reasons that are plain enough, our government has observed you closely for some time. We welcome your decision and wish to aid you in carrying it out. The Union is well rid of you, don’t you think?”

Van Gilder’s ire stirred, eating through his fear. “And I, sir . . . I am well rid of the Union!”

The major passed the lantern down to Kirschenbaum, who distractedly placed it in the coach’s boot, along with the empty pails. Holstering his weapon, Spruce dismounted with a grace unusual for a man his size, let alone an injured one. His whiskers were cinnamon brown and the bandages new, with no trace of dirt or blood. The horse complemented him entirely–a sleek black stallion whose forehead bore a patch of white, like a chipped diamond.

Spruce held his palm out to Van Gilder. “I’ll take your piece, for now.”

Van Gilder hesitated, teetering between caution and resentment. Then, with a quivering hand, he reached under his vest, withdrew the pistol and gave it up.

The major stuck the weapon in his saddlebag, from which he then took a bundled hitching strap. Unfurling it, he fastened one end to his horse’s bridle ring and the other to the coach’s roof railing.

“What are you doing?” Van Gilder demanded.

Spruce took out a little sack, then placed his booted foot on the coach’s step plate. “My mount can trot along behind. It’ll be daylight soon, and I don’t mean to be picked off when your secesh friends see us coming.” He signaled for Van Gilder to move his legs. “You’re stuck with me for the last few miles, good sir.”

Van Gilder budged over.

The major glanced over at Kirschenbaum. “Drive on.”

“Ja, sir.”

The hunchback hoisted himself up to the driver’s box as Spruce climbed in.

At the sound of the lash, the vehicle lurched, rocked and continued along the rutted road. Van Gilder’s heart still thudded. Longing for daylight, he averted his gaze from the major who sat opposite, one hand playing with the cord of the window blind.

“A Concord Coach,” said Spruce. “You do travel in style, don’t you?”

Van Gilder granted himself a look, taking in the holstered revolver, the bayonet in its leather scabbard, the broad shoulders with epaulettes. Spruce had not seen fit to remove his hat, under which tufts of cinnamon hair protruded. However noxious, his military aspect made him a known quantity, nudging Van Gilder toward sullen acquiescence. Still it unsettled him to sit facing a man with half a face. Then Van Gilder noticed the one pale eye looking straight at him.

“You will pardon my appearance,” said Spruce. “This little addition to my features was made a few weeks ago at Spotsylvania, courtesy of one of your fine compatriots.”

Van Gilder cleared his throat. “A misfortune I would have wished to prevent. As with this war.”

Arms crossed, the major gave a shrug, barely detectable amid the jarring of the dim coach.

Van Gilder felt satisfied with his own response. Beneath the lingering shock, he was settling down. He reached for his cane. Holding it firmly, he raised his double chin and tried to meet Spruce’s eye. Instantly his stomach tightened again. Even in this gloom, the look on the rugged, half-concealed face seemed too knowing.

Van Gilder struggled for an airy tone. “Through your lines, eh? I didn’t think there were lines to speak of in this region.”

“Your information is faulty, sir. Like your politics.”

Van Gilder managed an authentic glare.

“The Valley’s in federal hands,” said the major. “General Hunter’s on the march.” With a hint of smile, he reached under his cape and withdrew a flask, which he uncorked. “It helps the pain as well as anything,” he said, and took a quick swallow.

Van Gilder’s tension eased a bit. The coach bumped along beneath him, headed toward safety. He would make Strasburg, albeit with an unwelcome companion. “So you’re all they sent,” he observed.

Spruce chortled. “Ho-ho! First you’re indignant that we knew your movements—and now you complain of insufficient escort? Thanks in no small part to you and your kind, our forces are fully engaged throughout Virginia. We can scarcely spare men for duties so . . . minor.” He took another swallow, then wiped his lips on his cuff. “My regrets, sir, but one loyal convalescent is all we can afford you.”

Looking out at the bumpy darkness, Van Gilder sneered. “In truth, Major, you’re more than enough.”

Spruce let out a comfortable sigh. “I reckon I’ll suffice.”

Van Gilder sat back. He didn’t need to look at Spruce again. For him, in these cramped shadows, the scales had balanced. Patience had never been his strong card, but he could stand the presence of a tippling bluebelly for a while. So long as it meant asylum in the great gray bosom of Dixie.

“But come, Van Gilder—credit me with restraint. I’ve been told of your career and yet refrained from calling you any number of names. Treasonous dog, reptilian Judas, Copperhead scum . . . "

Van Gilder straightened in his seat. His face grew warm as he forced a glare into Spruce’s lone eye, and for a moment he became the self that he fancied best: champion of states’ rights, arch-foe of miscegenation, battler of the tyrannical federal serpent. “Then credit me, sir! Credit me with the ardor of my convictions! The prospect of despotism and half-nigger infants may not worry you. The plague of freed black bucks robbing honest white men of their livelihoods may not concern you. But for my part I’ve endured intrigue, vilification and all manner of devilry for merely wishing peace. Peace, Major! An end to the wounds and killing! Your face, sir, would be whole now if my words and those of my fellow believers had been heeded!”

Holding a hand up, the big officer looked into his lap and slowly shook his head. “And you have many words, I’m sure. I cannot hope to match their eloquence, certainly not at this late hour.” The hand fell. “In fact and at heart, I’m a humble soldier. Besides, I’ve heard the Copperhead gospel so many times it makes my senses fog. So let’s simply enjoy the ride, eh?”

Van Gilder looked down at the major’s boots and smirked. Spruce’s voice was as odd as the man himself, sounding as if he had a pebble in his throat or needed to burp. Now it throbbed with false conciliation, its owner taking refuge from Van Gilder’s impassioned tongue. Whiskey was rapidly dulling this warrior’s spirit. The man had just pleaded for mercy, after a fashion, and Van Gilder supposed he might soon be hearing maudlin tales of a wife and children left behind. This was by no means the sort of exit he had planned, but at least he would depart Northern soil on a note of moral victory. Miraculously he was no longer afraid.

“You do well enough, Major,” he said, “—for a humble soldier. Though you rely on snideness overmuch.”

“War hardens us overmuch, Van Gilder.” Spruce took another nip and then reached into his little sack, from which he produced a silver folding cup. “I propose that this trip be made not in the spirit of rancor, but in recognition of opposing ends achieved at a single stroke.” He raised the cup, its rim glistening. “For you the South opens its grateful arms, while the North may now turn its intrigue and vilification upon other worthy targets. This journey, sir, is celebratory.”

Van Gilder leaned forward on his cane. He sniggered. “You propose that I drink with you, Major Spruce?”

Looking thoughtful, Spruce lowered the cup, then used it to push back the brim of his hat. “I . . . I propose that we honor the one objective, the one prayer we find mutually agreeable. To this sorrowful conflict’s end.”

Van Gilder arched an eyebrow.

Spruce raised the flask and the cup, poured two fingers’ worth and offered it to Van Gilder. Sneering at the cup, Van Gilder let Spruce’s hand hold it there for a moment, vibrating with the road. Then he took it. He could humor a jabbering Unionist fool. Perhaps he could even squeeze the man for an answer or two—answers that he could impart to Richmond officials, when he told them how outrageously sloppy their agents were.

“Not that it matters now,” Van Gilder said, “—but how were my movements made known to you?”

Now it was Spruce who smirked. He drew his hat down till it hid his eye. “Let it just be said that the government has its ways. More than either of us can know.”

Van Gilder shifted position, frowning at his drink. After all the tense planning for this contingency, his Southern friends—maybe even Cathcart, his most trusted—stood guilty of some idiotic lapse, the exact nature of which he would probably never know. The thought made him sullen once more.

Spruce held the flask up. “To war’s end!”

Van Gilder squinted at the hat’s brim, hoping the major could feel the heat of his contempt. “To peace!” he declared, and downed the liquor.

Smacking his lips, he gazed out at the night again. In the deep black of the east he sensed the Blue Ridge Mountains, soon to be fringed red with dawn. Sooner than that, this road would join the Valley Pike, taking him through Winchester and on to Strasburg. Surely he was in Virginia by now.

The coach slowed as it started on an uphill grade. Through the door seam came a breeze, clammy on Van Gilder’s face. He was perspiring. He realized that he had dropped both the cup and the cane and that his fingers had gone limp. As he turned his head, the fear began—a quiet explosion of cold, all over.

On the seat beside his companion he saw the corked flask. Next to that lay the major’s hat, upside down, the cinnamon wig like some dead creature in its hollow. And he saw the man watching him—fingertips together, elbows out, cape spread. A man of shadows—half-faced, dark-maned, somehow larger than before. Van Gilder knew the patient mannerism of the fingertips. He knew the lone steady eye, the barely visible scar along the scalp. And when the voice came, the true voice, he knew that too—smooth and distant yet horribly intimate, as in his nightmares.

“How do you feel, Gideon?”

Van Gilder understood at last that fear had been a presence throughout his life. Fear of many things, played out in bluster and vitriol. But the terror that struck him now dwarfed the sum of every fear he had known, quaking him in a tide of nausea. His eyelids fluttered, but if he blacked out it was only for a few seconds. In his swimming vision he beheld the half-faced specter, waiting there. Van Gilder could not move. His lips emitted a low whine.

“Nothing fatal,” said the voice. “The cup was coated with a substance derived from the glands of a large Caribbean toad. Hard to obtain, but within our means. It will simply . . . hold you in place.”

Wide-eyed, his insides bucking, Van Gilder strained against the near-complete paralysis.

“It was easy, mind you. I just had to wait, watch, trail you for a bit.”

Van Gilder stared, choked.

The fingertips parted, then came to rest on his knees. “And if you could speak, Gideon, what would the words be? A plea, I suppose. But you recall our last session and what passed between us then. A whole year ago—could that be?” Reaching out with his index, he flicked Van Gilder’s hair beside his right ear. “A covenant broken is a kind of death.” His caped bulk leaned forward, looming. “It is death. Death, precisely. With death as its only atonement.”

The coach started down a grade, speeding up with a clacking of wheels. Blood thumping in his ears, Van Gilder fought to breathe. For an instant, horror transported him back to the night that he had entered into the contract and doomed himself—a howl within his memory, unfathomable. Then he returned, though the howl could not break free. His eyes bulged at the one pale eye and he knew that he was in hell—a cramped, dim, rocking hell prepared for him alone, with the darkest of angels presiding. The specter looked down, contemplative. Next to his upended hat sat a jar full of clear fluid labeled “Formaldehyde.” Then, with that casual elegance, he drew his bayonet. If Van Gilder’s soul had harbored any small hope of reprieve, it died now. There would be no reprieve, no mercy.

The dark angel sighed. “Gideon—your atonement begins.”

CHAPTER ONE

NORTHERN SHENANDOAH VALLEY

JUNE 6, 1864

Gideon Van Gilder had left his dignity far behind, like an expensive topcoat forgotten in haste. He did not mourn its loss—had not mourned it even at the last roadside inn, when he started awake and spied his stricken face in a shaving mirror. Now, huddled again inside the rocking coach, he could think only of escape. Escape—southward, southward by moon and carriage light, along this road so rough that it threatened to break the axles. Up the hill-haunted Shenandoah lay sanctuary, some haven behind the booming, gargantuan battle lines. Only there could he know rest once more. Rest, and perhaps the luxury of pride.

The lump of the derringer beneath his vest was small comfort–he had never fired a pistol in his life. At times in the jouncing blur of his journey, he had found himself gripping his cane between his knees like a talisman of dubious power. More frequently than ever he yelled at his hunchbacked coachman, calling him a sausage-eating monkey or a deformed German half-wit. The coachman said little.

Awaking from a fitful doze, Van Gilder realized that the coach’s rocking had ceased. He shuddered as he blinked out of the window into a mass of tall black shapes that hid the moon. He heard a ragged breathing sound. After a disoriented moment, he identified the sound as that of the horses and the obstruction as a stand of pine. He shifted to the other side and elbowed the door open. In the carriage lamp’s glow he discerned the misshapen form of the coachman. He was carrying two pails down an embankment, headed for the ripple of an unseen creek.

Van Gilder drew a breath to holler, but in the dark his voice came as a hushed rasp. “Kirschenbaum!”

Maintaining his balance on the slope, the coachman made an awkward turn. “Horses are tired, you makes them run all night. Tired like me, sir. I get vater.”

“Do it, then, imbecile! But no more stops!”

The hunched form started to turn away, then hesitated. “Herr Van Gilder?”

“Get the damned water!”

“We gets closer to the secesh.”

“Yes!” Van Gilder hissed “Yes—and I’ve paid you! Get the water!”

“I did not know I must take you five days and now all night. And we gets closer to the secesh.”

Though still hushed, Van Gilder’s voice began its climb toward full fury. “Fool! I know where we’re going! I’ve paid you!”

“You pay me more, I think.”

In the rippling stillness, one of the animals snorted. Van Gilder sputtered a curse. “Three dollars more, when we reach the place!”

“Ten.”

From the creek, a bullfrog let out a deep “bong” sound. Van Gilder thought of the derringer—wishing, thwarted. This time he spoke in just a murmur. “Ten, when we get there.”

“I thank you,” said the hunchback, who resumed his descent.

Dense with cricket noise, the warm, still air pressed in on Van Gilder, worsening his agitation. He took up his map, rattled it open and lit a match. In the match’s flutter he followed the black line of his route to the town of Strasburg, marked by a tight circle. Twenty-five miles to go, more or less. He blew out the match, folded the map and again peered outside.

“Kirschenbaum!” he called in a hoarse whisper.

From the embankment, the hunchback’s laboring form reappeared with the pails, slopping water. Kirschenbaum began watering the first pair of horses. When they got to Strasburg, Van Gilder thought, he would stick his derringer in the face of this insolent moron. Then he would drop a single coin at his feet and tell him to get out of his sight forever.

“Van Gilder!” came a deep-throated call.

Van Gilder jerked upright. For a crazed moment, he could neither move nor think nor breathe. Then, blindly, he began fumbling for his derringer.

“Don’t fret,” came the voice. “I am here to see that you pass safely through our lines.”

Van Gilder stopped pawing at his vest. Shaking, he leaned slowly out the side. He saw Kirschenbaum standing motionless, staring past the back of the coach. From that direction he heard a crunch of pebbles, very close. How—how could anyone have come upon them with such stealth? Leaning out farther, he forced his head to turn. Out of the gloom, the shape of a horse and rider emerged. The man wore a military cap, cape and double-breasted tunic, its brass buttons winking like sparks. With the oil running low, the lamps cast a meager halo about the coach—and as the stranger entered it, his uniform proved to be Union blue. He held a revolver and the reins in one hand, an extinguished lantern in the other.

Van Gilder gazed, open-mouthed as the intruder guided his mount forward and then halted–a bearded, powerful-looking officer, the right side of his face hidden by bandages. In an attitude of dutiful ease, he slouched in the saddle, his revolver held loosely away. His one visible eye peered down at Kirschenbaum, though it was Van Gilder whom he addressed:

“Major Henry Spruce, Army of the Potomac, currently on detached service. I am your official escort—to ensure that you make your rendezvous in Strasburg. That you do so without being fired upon by federal pickets, who perhaps know a traitor when they see one.”

There was something odd about the major’s low-in-the-throat intonation. Still gaping, Van Gilder fidgeted with the buttons of his coat. “How did you know . . . ?”

“For reasons that are plain enough, our government has observed you closely for some time. We welcome your decision and wish to aid you in carrying it out. The Union is well rid of you, don’t you think?”

Van Gilder’s ire stirred, eating through his fear. “And I, sir . . . I am well rid of the Union!”

The major passed the lantern down to Kirschenbaum, who distractedly placed it in the coach’s boot, along with the empty pails. Holstering his weapon, Spruce dismounted with a grace unusual for a man his size, let alone an injured one. His whiskers were cinnamon brown and the bandages new, with no trace of dirt or blood. The horse complemented him entirely–a sleek black stallion whose forehead bore a patch of white, like a chipped diamond.

Spruce held his palm out to Van Gilder. “I’ll take your piece, for now.”

Van Gilder hesitated, teetering between caution and resentment. Then, with a quivering hand, he reached under his vest, withdrew the pistol and gave it up.

The major stuck the weapon in his saddlebag, from which he then took a bundled hitching strap. Unfurling it, he fastened one end to his horse’s bridle ring and the other to the coach’s roof railing.

“What are you doing?” Van Gilder demanded.

Spruce took out a little sack, then placed his booted foot on the coach’s step plate. “My mount can trot along behind. It’ll be daylight soon, and I don’t mean to be picked off when your secesh friends see us coming.” He signaled for Van Gilder to move his legs. “You’re stuck with me for the last few miles, good sir.”

Van Gilder budged over.

The major glanced over at Kirschenbaum. “Drive on.”

“Ja, sir.”

The hunchback hoisted himself up to the driver’s box as Spruce climbed in.

At the sound of the lash, the vehicle lurched, rocked and continued along the rutted road. Van Gilder’s heart still thudded. Longing for daylight, he averted his gaze from the major who sat opposite, one hand playing with the cord of the window blind.

“A Concord Coach,” said Spruce. “You do travel in style, don’t you?”

Van Gilder granted himself a look, taking in the holstered revolver, the bayonet in its leather scabbard, the broad shoulders with epaulettes. Spruce had not seen fit to remove his hat, under which tufts of cinnamon hair protruded. However noxious, his military aspect made him a known quantity, nudging Van Gilder toward sullen acquiescence. Still it unsettled him to sit facing a man with half a face. Then Van Gilder noticed the one pale eye looking straight at him.

“You will pardon my appearance,” said Spruce. “This little addition to my features was made a few weeks ago at Spotsylvania, courtesy of one of your fine compatriots.”

Van Gilder cleared his throat. “A misfortune I would have wished to prevent. As with this war.”

Arms crossed, the major gave a shrug, barely detectable amid the jarring of the dim coach.

Van Gilder felt satisfied with his own response. Beneath the lingering shock, he was settling down. He reached for his cane. Holding it firmly, he raised his double chin and tried to meet Spruce’s eye. Instantly his stomach tightened again. Even in this gloom, the look on the rugged, half-concealed face seemed too knowing.

Van Gilder struggled for an airy tone. “Through your lines, eh? I didn’t think there were lines to speak of in this region.”

“Your information is faulty, sir. Like your politics.”

Van Gilder managed an authentic glare.

“The Valley’s in federal hands,” said the major. “General Hunter’s on the march.” With a hint of smile, he reached under his cape and withdrew a flask, which he uncorked. “It helps the pain as well as anything,” he said, and took a quick swallow.

Van Gilder’s tension eased a bit. The coach bumped along beneath him, headed toward safety. He would make Strasburg, albeit with an unwelcome companion. “So you’re all they sent,” he observed.

Spruce chortled. “Ho-ho! First you’re indignant that we knew your movements—and now you complain of insufficient escort? Thanks in no small part to you and your kind, our forces are fully engaged throughout Virginia. We can scarcely spare men for duties so . . . minor.” He took another swallow, then wiped his lips on his cuff. “My regrets, sir, but one loyal convalescent is all we can afford you.”

Looking out at the bumpy darkness, Van Gilder sneered. “In truth, Major, you’re more than enough.”

Spruce let out a comfortable sigh. “I reckon I’ll suffice.”

Van Gilder sat back. He didn’t need to look at Spruce again. For him, in these cramped shadows, the scales had balanced. Patience had never been his strong card, but he could stand the presence of a tippling bluebelly for a while. So long as it meant asylum in the great gray bosom of Dixie.

“But come, Van Gilder—credit me with restraint. I’ve been told of your career and yet refrained from calling you any number of names. Treasonous dog, reptilian Judas, Copperhead scum . . . "

Van Gilder straightened in his seat. His face grew warm as he forced a glare into Spruce’s lone eye, and for a moment he became the self that he fancied best: champion of states’ rights, arch-foe of miscegenation, battler of the tyrannical federal serpent. “Then credit me, sir! Credit me with the ardor of my convictions! The prospect of despotism and half-nigger infants may not worry you. The plague of freed black bucks robbing honest white men of their livelihoods may not concern you. But for my part I’ve endured intrigue, vilification and all manner of devilry for merely wishing peace. Peace, Major! An end to the wounds and killing! Your face, sir, would be whole now if my words and those of my fellow believers had been heeded!”

Holding a hand up, the big officer looked into his lap and slowly shook his head. “And you have many words, I’m sure. I cannot hope to match their eloquence, certainly not at this late hour.” The hand fell. “In fact and at heart, I’m a humble soldier. Besides, I’ve heard the Copperhead gospel so many times it makes my senses fog. So let’s simply enjoy the ride, eh?”