Bernie MacKinnon's Blog - Posts Tagged "jubal-early"

The German Americans

In Manfred Kirschenbaum, my novel's main hero Major Nathan Truly has a hugely valuable asset. Kirschenbaum is a hunchbacked German immigrant, a veteran of the 1848 revolutionary movement that rocked the German states, along with much of Europe. He is working as a hack driver in New York City when he and Truly first meet, in the aftermath of that city's July 1863 Draft Riots (still the most deadly and costly such event in U.S. history.) Kirschenbaum's physical limitation prevents him from joining the Union cause as a soldier—but not as an intelligence operative. In that capacity, under Truly's direction, he shines, displaying wily resourcefulness and an observant eye. Working as coachman for Gideon Van Gilder, a venomous Copperhead newspaper publisher, he gathers information on anti-Union activities in NYC, which was then a hotbed of pro-Southern sentiment. And when Van Gilder mysteriously flees the city in terror, it is Kirschenbaum who drives his horse-drawn coach through the night, toward a fateful rendezvous in the Shenandoah Valley. With that rendezvous, the increasingly dire events of Lucifer's Drum are set in motion.

German Americans remain the largest distinct ethnic group in the U.S.—and in the Civil War, were the largest such group represented in Union military ranks. German-speaking people were settling in British North America from the earliest colonial times, the very first being Dr. Johannes Fleischer at the 1607 founding of Jamestown, Virginia. In the North, they played a conspicuous role in the settling of New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa and Missouri; in the South, many set roots in Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, French Louisiana and eventually Texas (where, in a fine example of cultural cross-fertilization, they introduced Mexican residents to the accordion.) They were drawn by the classic immigrant visions—rich land for farmers and a burgeoning economy for shopkeepers and artisans, as well as freedom from religious and political oppression.

Germany would not exist as a coherent nation until the Franco-Prussian War, 1870-71, when Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck engineered a stunning victory over France. Simultaneously, the loosely run German Confederation—founded by the 1815 Congress of Vienna, comprising thirty-nine principalities—was galvanized into the German Empire. But before von Bismarck's triumph, these German states chafed under the autocratic domination of Austria; they were therefore fertile ground for liberal political agitation. In early 1848, an anti-monarchist revolution broke out in Paris and ignited several concurrent uprisings throughout the Confederation, throwing many crowned heads into panic. Working and middle class Germans held massive street demonstrations, demanding better living and working conditions, as well as universal male suffrage, freedom of assembly, freedom of the press and a united Germany. In many instances, royalist troops fired on unarmed demonstrators, who reacted by arming themselves and taking the crisis to a new and bloodier level.

Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I, Prussian King Fredrick William IV and the many German princes made nervous concessions. A National Assembly was called in the free city of Frankfurt am Main—in the novel, Kirschenbaum's home city—and drew up a constitution enshrining the principle of equal rights. Its primary goal was to unite the states as a constitutional monarchy—but as the revolution's working and middle class factions gradually split, and as advocates of Austrian vs. Prussian hegemony failed to agree, royalty and aristocracy realized that the liberal peril was receding. The Assembly at Frankfurt was dissolved in May 1849. Full-fledged war broke out between the revolutionaries and the Kingdom of Prussia, and the revolutionaries lost big.

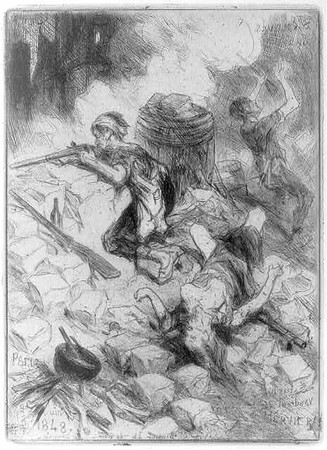

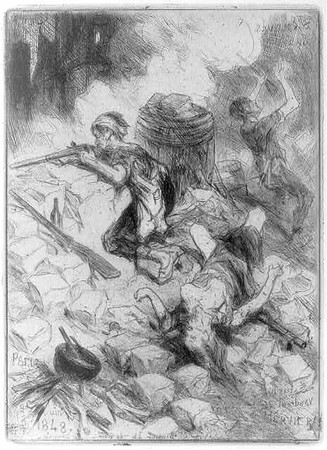

Street-fighting scene from the Revolutionary Year

of 1848, Adolphe Hervier (1821-1879).

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In a dispiriting anticlimax, concessions were cancelled, rights abolished and protests violently suppressed. Arrests, executions and imprisonments followed. One consequence of this was a great wave of German immigration—disappointed exiles known as "The Forty-Eights," seeking the political freedom they had failed to achieve in their homeland. For the United States, this brought an infusion of people who, however hardscrabble their lives, were beneficiaries of the German primary school system—at that time, probably the best and most inclusive in the world. Overall highly literate and well-read, they took a robust interest in current events—and when the Civil War commenced, they overwhelmingly supported Lincoln and then Emancipation.

Several all-German units did fight for the South, though none reached regimental strength. In Texas, the community of Forty-Eighters steadfastly opposed both slavery and secession. Threatened with the draft in August of 1862, one armed group of them attempted an escape to Mexico but were caught and crushed by a Confederate force on the Nueces River. The North, by contrast, raised many all-German regiments—five from Pennsylvania, six from Ohio and eleven from New York, as well as others from Indiana and Wisconsin. More than 200,000 Union soldiers were German-born. In war-riven Missouri, the pro-Union German community was a crucial factor in preventing secession. (It was a largely German unit under Captain Nathaniel Lyon, in May 1861, that kept Confederates from capturing the federal arsenal at St. Louis.)

Prominent among German Americans was Carl Schurz, a Forty-Eighter who threw his legal and journalistic skills behind the early Republican Party, and whose wife Margarethe was a pioneer in the field of early childhood education. Appointed ambassador to Spain by Lincoln, Schurz tactfully influenced that country against supporting the Confederacy. Later, he served as Brigadier-General and earned a reputation for bravery, serving at the Union defeats of Second Bull Run and Chancellorsville and then the victories of Gettysburg and Chattanooga. After the war, he edited newspapers at Detroit and St. Louis. In 1868 he was elected Senator for Missouri, becoming the U.S. Senate's first German American. He later served as Secretary of the Interior under President Rutherford B. Hayes.

Just as prominent was Schurz's friend and fellow Forty-Eighter Major-General Franz Sigel. Sigel's mention in Lucifer's Drum is not complimentary, referring to the whipping he took at the Battle of New Market (May 15, 1864) in the Shenandoah. But Sigel was a man of proven valor, whose reputation helped attract German recruits throughout the war—"I fights mit Sigel!" was their proud declaration. Early on, he was instrumental in keeping the Union's grip on Missouri. And on March 8, 1862, Sigel's counterattack at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, sealed an important Union victory.

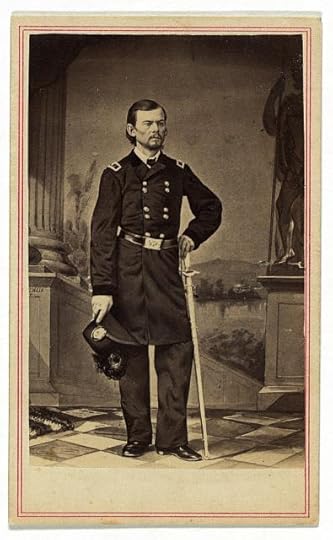

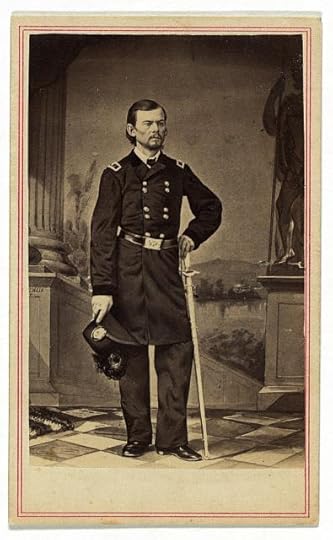

Major-General Franz Sigel, victorious at Pea Ridge

but crushed at New Market; throughout the war, a

powerful symbol of pro-Union German Americans.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Max Weber, who had served under Sigel in the '48 revolutionary forces, raised a German American unit called the Turner Rifles and became a Brigadier-General of Volunteers. At Antietam, assaulting John Brown Gordon's position along the Sunken Road, Weber was grievously wounded. He too gets brief mention in Lucifer's Drum, for his hasty evacuation of Harper's Ferry during Early's Raid. (True to the time and place, Sigel and Weber are referred to in the book as "Dutchmen," a common corruption of "Deutsch.")

Lawyer, revolutionary and politician Friedrich Heckler escaped royalist authorities in Europe and settled in Illinois, where he had a major role in founding the Republican Party and focusing its abolitionist principles. He became a regimental colonel of largely German immigrant troops and was badly wounded at Chancellorsville, though he recovered to participate in the victory of Missionary Ridge and the capture of Knoxville.

Seventeen German immigrants serving under the Union banner received the Medal of Honor.

Rich and poor, male and female, Catholic and Protestant and Jewish, these German Americans represented a vast and obvious benefit for the United States, given their literacy, industriousness and idealism. Poignantly, they were just the sort of German that Germany itself, some seventy years after the U.S. Civil War, could have used to combat Hitler's rise. And when the U.S. army landed in occupied Europe, its ranks again featured German names from top to bottom—from future novelist Private Kurt Vonnegut to Allied Supreme Commander General Dwight Eisenhower. Thus, often, is one nation's catastrophe another nation's gain.

German Americans remain the largest distinct ethnic group in the U.S.—and in the Civil War, were the largest such group represented in Union military ranks. German-speaking people were settling in British North America from the earliest colonial times, the very first being Dr. Johannes Fleischer at the 1607 founding of Jamestown, Virginia. In the North, they played a conspicuous role in the settling of New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa and Missouri; in the South, many set roots in Virginia, North Carolina, Georgia, French Louisiana and eventually Texas (where, in a fine example of cultural cross-fertilization, they introduced Mexican residents to the accordion.) They were drawn by the classic immigrant visions—rich land for farmers and a burgeoning economy for shopkeepers and artisans, as well as freedom from religious and political oppression.

Germany would not exist as a coherent nation until the Franco-Prussian War, 1870-71, when Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck engineered a stunning victory over France. Simultaneously, the loosely run German Confederation—founded by the 1815 Congress of Vienna, comprising thirty-nine principalities—was galvanized into the German Empire. But before von Bismarck's triumph, these German states chafed under the autocratic domination of Austria; they were therefore fertile ground for liberal political agitation. In early 1848, an anti-monarchist revolution broke out in Paris and ignited several concurrent uprisings throughout the Confederation, throwing many crowned heads into panic. Working and middle class Germans held massive street demonstrations, demanding better living and working conditions, as well as universal male suffrage, freedom of assembly, freedom of the press and a united Germany. In many instances, royalist troops fired on unarmed demonstrators, who reacted by arming themselves and taking the crisis to a new and bloodier level.

Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I, Prussian King Fredrick William IV and the many German princes made nervous concessions. A National Assembly was called in the free city of Frankfurt am Main—in the novel, Kirschenbaum's home city—and drew up a constitution enshrining the principle of equal rights. Its primary goal was to unite the states as a constitutional monarchy—but as the revolution's working and middle class factions gradually split, and as advocates of Austrian vs. Prussian hegemony failed to agree, royalty and aristocracy realized that the liberal peril was receding. The Assembly at Frankfurt was dissolved in May 1849. Full-fledged war broke out between the revolutionaries and the Kingdom of Prussia, and the revolutionaries lost big.

Street-fighting scene from the Revolutionary Year

of 1848, Adolphe Hervier (1821-1879).

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

In a dispiriting anticlimax, concessions were cancelled, rights abolished and protests violently suppressed. Arrests, executions and imprisonments followed. One consequence of this was a great wave of German immigration—disappointed exiles known as "The Forty-Eights," seeking the political freedom they had failed to achieve in their homeland. For the United States, this brought an infusion of people who, however hardscrabble their lives, were beneficiaries of the German primary school system—at that time, probably the best and most inclusive in the world. Overall highly literate and well-read, they took a robust interest in current events—and when the Civil War commenced, they overwhelmingly supported Lincoln and then Emancipation.

Several all-German units did fight for the South, though none reached regimental strength. In Texas, the community of Forty-Eighters steadfastly opposed both slavery and secession. Threatened with the draft in August of 1862, one armed group of them attempted an escape to Mexico but were caught and crushed by a Confederate force on the Nueces River. The North, by contrast, raised many all-German regiments—five from Pennsylvania, six from Ohio and eleven from New York, as well as others from Indiana and Wisconsin. More than 200,000 Union soldiers were German-born. In war-riven Missouri, the pro-Union German community was a crucial factor in preventing secession. (It was a largely German unit under Captain Nathaniel Lyon, in May 1861, that kept Confederates from capturing the federal arsenal at St. Louis.)

Prominent among German Americans was Carl Schurz, a Forty-Eighter who threw his legal and journalistic skills behind the early Republican Party, and whose wife Margarethe was a pioneer in the field of early childhood education. Appointed ambassador to Spain by Lincoln, Schurz tactfully influenced that country against supporting the Confederacy. Later, he served as Brigadier-General and earned a reputation for bravery, serving at the Union defeats of Second Bull Run and Chancellorsville and then the victories of Gettysburg and Chattanooga. After the war, he edited newspapers at Detroit and St. Louis. In 1868 he was elected Senator for Missouri, becoming the U.S. Senate's first German American. He later served as Secretary of the Interior under President Rutherford B. Hayes.

Just as prominent was Schurz's friend and fellow Forty-Eighter Major-General Franz Sigel. Sigel's mention in Lucifer's Drum is not complimentary, referring to the whipping he took at the Battle of New Market (May 15, 1864) in the Shenandoah. But Sigel was a man of proven valor, whose reputation helped attract German recruits throughout the war—"I fights mit Sigel!" was their proud declaration. Early on, he was instrumental in keeping the Union's grip on Missouri. And on March 8, 1862, Sigel's counterattack at the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, sealed an important Union victory.

Major-General Franz Sigel, victorious at Pea Ridge

but crushed at New Market; throughout the war, a

powerful symbol of pro-Union German Americans.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Max Weber, who had served under Sigel in the '48 revolutionary forces, raised a German American unit called the Turner Rifles and became a Brigadier-General of Volunteers. At Antietam, assaulting John Brown Gordon's position along the Sunken Road, Weber was grievously wounded. He too gets brief mention in Lucifer's Drum, for his hasty evacuation of Harper's Ferry during Early's Raid. (True to the time and place, Sigel and Weber are referred to in the book as "Dutchmen," a common corruption of "Deutsch.")

Lawyer, revolutionary and politician Friedrich Heckler escaped royalist authorities in Europe and settled in Illinois, where he had a major role in founding the Republican Party and focusing its abolitionist principles. He became a regimental colonel of largely German immigrant troops and was badly wounded at Chancellorsville, though he recovered to participate in the victory of Missionary Ridge and the capture of Knoxville.

Seventeen German immigrants serving under the Union banner received the Medal of Honor.

Rich and poor, male and female, Catholic and Protestant and Jewish, these German Americans represented a vast and obvious benefit for the United States, given their literacy, industriousness and idealism. Poignantly, they were just the sort of German that Germany itself, some seventy years after the U.S. Civil War, could have used to combat Hitler's rise. And when the U.S. army landed in occupied Europe, its ranks again featured German names from top to bottom—from future novelist Private Kurt Vonnegut to Allied Supreme Commander General Dwight Eisenhower. Thus, often, is one nation's catastrophe another nation's gain.

Published on September 07, 2015 17:27

•

Tags:

1848, bernie-mackinnon, civil-war, german-americans, jubal-early, lucifer-s-drum, new-york-city-draft-riots

The Irrepressible Conflict: 2015

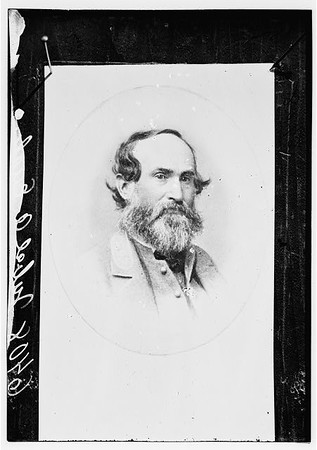

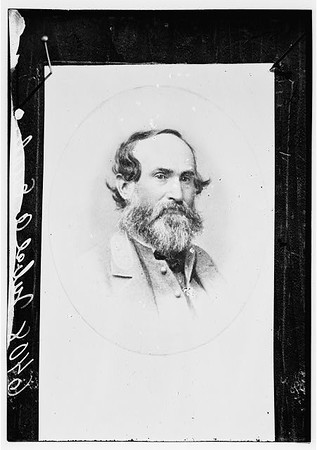

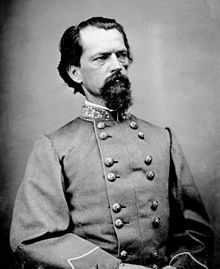

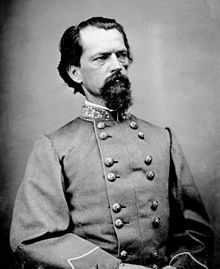

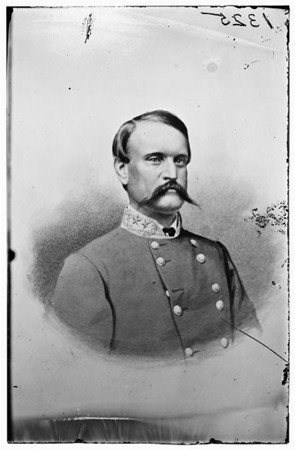

Confederate Lnt.-Gen. Jubal Early, pre-war moderate/post-war zealot. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

On the military side of my novel Lucifer's Drum, Lnt.-Gen. Jubal Anderson Early (1816-1894) stands center stage. His thrust against Washington, D.C. in the summer of 1864 gave the North a bad scare, and so gives the novel much of its tension. Before and during the war, Early typified an outlook that the war ended up burying—one that prized loyalty to state over national loyalty. It was a feeling and a concept steeped in the past—several steps beyond tribes, a step or two beyond city-states, but well short of full-blown nationalism. Early's chauvinistic love for his home state of Virginia led him to join the Confederate forces. He never missed a chance to extoll Virginia, sometimes at the expense of other states under the Confederate banner—and to the exasperation of fellow officers from those states. Still, for professional military men, birthplace did not necessarily determine which side they chose.

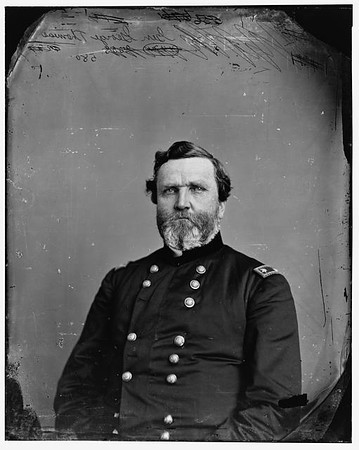

Following the War of 1812, continued reliance on state militias seemed a lousy idea, given that war's many battlefield humiliations for the U.S. Resources were committed to upgrading the Military Academy at West Point and to building a truly national army. This enabled a devastating U.S. victory in the 1846-47 war with Mexico. On the eve of the Civil War, however, the standing army numbered only 16,000—but within its ranks, an identification with country over state or region was inevitably fostered. It may not have prevented Early, Robert E. Lee and 60% of their fellow Virginians from going South, but there was still that 40% who went the other way. Prominent among them was Union General George "Pap" Thomas, one of the ablest leaders of the conflict, who saved the Union position at Chickamauga and shattered John Bell Hood's Confederate force at Nashville. In November, 1863, following the Northern victory at Chattanooga, Thomas ordered a new cemetery laid out for his dead. Asked whether he wanted them buried according to state, the general famously replied, "No—mix 'em up. I'm sick of states' rights." Thomas stood for this dawning nationalist perspective, just as Early stood for his obsolete state-centered one. The two men were fellow Virginians and contemporaries but really signified different eras, an outgoing and an incoming. Ken Burns, in his monumental The Civil War series, observed how the war transformed the country in people's minds from a plural to a singular—from "the United States are" to "the United States is." In that linguistic shift, you hear a new worldview swallowing an old one—something that happens all the time in history, though seldom so suddenly or violently.

In the pre-war years, Jubal Early was no fanatic. As Franklin County prosecutor, he was named delegate to the state convention that had been called to decide on secession, which he opposed until very late in the crisis. He showed little patience for the rabid pro-slavery element. As an attorney ten years earlier, in 1851, he had successfully represented an ex-slave woman named Indiana Choice. (Choice had been freed by her widowed mistress, whose second husband later tried to negate the manumission.) But the war left Early bitter and recalcitrant. Following exile in Canada, he returned to Virginia and resumed his law practice. The mid-1870’s found him virulently white-supremacist, refusing to participate in any commemorative ceremony that included black veterans. In word and in writing, he also did much to promote the cult of Robert E. Lee, which raised that great, now-deceased general to godlike status (much as the cult of Lincoln did for that greatest, most mysterious of Presidents.) Early never married, though he sired four children by Julia McNealey of Rocky Mount, VA. Disdaining the loyalty oath, he died “unreconstructed” in 1894, aged 77.

{A postscript on "Pap" Thomas: During Reconstruction, he commanded occupying troops in the South, often deploying them to defend black communities against the Klan. He also set up military commissions to enforce labor contracts with black citizens, circumventing the bigoted local courts. When he died of a stroke in 1870, aged 53, his Virginia relatives all boycotted the funeral. For his allegiance to the Union and his effectiveness against Southern arms, he had long been dead to them.}

Union Maj.-Gen. George "Pap" Thomas, an American

first and a Virginian second. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

**************************************************************************

And friends—at this time, like none other, taking on the subject of Jubal Early is like drinking from a firehose. Because wartime Early leads to post-war Early, which leads to white supremacy and Jim Crow. Which leads to desegregation and the Confederate Battle Flag. Which leads to now. How many times has it been said that the Civil War is still being fought, 150 years on? And how much more pertinent could that thought be, with the AME Church in Charleston, SC now hallowed by the blood of the Nine, killed by one who sported the Confederate flag as a purely white-supremacist symbol? And with growing calls for South Carolina—the first state of the Confederacy, the war's Ground Zero—to take down said flag at its State House? And for other Southern states to do likewise? And with debate intensifying over any number of Confederate memorials? For obvious historical reasons, Lucifer's Drum bears on its cover the flag in question. It fits there. But should it be endorsed and flown by any state government? The answer cuts right to the heart of this war that—in spirit, and therefore in fact—we are still fighting.

It is hard to think of another instance where a war's losing side has been given such latitude in the writing (and re-writing) of that war's history. In the years after Appomattox and the aborted Reconstruction, the North had a considerable interest in mollifying its former enemy, recognizing that to further fuel the South's hatred would cause no end of trouble—spasmodic violence, bitter obstruction, further exhaustion. Sentimentality was invoked to cover the nation's raw scars, as in memorial pictures that showed Union and Confederate veterans shaking hands. Slavery's collapse and the emancipation of four million people—the war's biggest consequence, the sorest point for the South—was systematically de-emphasized in favor of Reconciliation, a simple Union vs. Disunion theme. But the violence, the obstruction and the exhaustion came anyway.

Attacks on black voting rights went largely unanswered. Jim Crow laws took root and would get no serious challenge for eighty years. Lynchings spiked and spiked again. Confederate monuments were erected throughout the South, not just to honor brave men but, even more, to frame the Southern cause as a straight-up defense of home and freedom. (In the lovely Oxford, MS town square stands one with the inscription, "To Those Who Died In A Just And Holy Cause.") In 1915, D.W. Griffith's masterful pro-Klan/pro-Confederate fantasy The Birth Of A Nation was honored with a screening at the White House. The film, with the apparent endorsement of Southern-born-and-raised President Woodrow Wilson, stirred anti-black violence across the country and caused a surge in Klan recruitment. (Around this same time, Wilson was busy re-segregating federal buildings and the federal civil service, which had been integrated since the 1880's. He remains to me the template for the Cerebral Racist, a variety that has arguably done more harm than any number of burning crosses—the kind that smiles down benevolently at an oppressed ethnic group and says, in effect, "Let me tell you all about yourself.")

Since the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960's, a mountain of scholarship has placed slavery—and the contributions of black Union soldiers—back at the center of Civil War history, while at the same time cultivating a nuanced, non-glorifying view of the North. The heirs to states'-rights doctrine have not taken this lying down. On the contrary, they have made a concerted effort to obfuscate slavery as the central cause and to sanitize the past. School textbooks have long been a vital part of this battlefield. In Virginia in 2010, a newly published fourth-grade history textbook described massive black enlistment in the Confederate forces, including two battalions that supposedly fought under Stonewall Jackson. But all this happened only in the fevered imaginations of neo-Confederates. Trained historians—of whom the author of this book was not one—fortunately decried the fabrication and had the passage struck. That same year, the conservative-dominated and nationally influential Texas Board of Education endorsed the idea that states' rights, not slavery, should be taught as the war's primary issue. In April of that year, at the request of the Sons Of Confederate Veterans, Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell resurrected Confederate History Month by proclamation, omitting any mention of slavery as a root cause for the war. A national protest caused the governor to back down on this point and make a statement condemning the Peculiar Institution. At that same time, however, Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour declared Confederate Heritage Month ("Heritage"—such a comfy term compared to "History," which so often proves dark, slippery and nervous-making.) Barbour defended McDonnell and stood by his own silence on slavery as a root cause: We all know it was bad, so why bring it up?

Sgt. Samuel Smith of the 119th USCT (United States Colored Troops) and family.

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Of those white Southerners who deny or downplay the connection between slavery and the Civil War, I think a majority do so mainly out of an understandable defensiveness. Defensiveness not just against hard-to-swallow historical fact, but against Northern snobbery on the subject. And as a Northern transplant, I can confirm that this snobbery persists—flattering those who indulge in it, while projecting responsibility for American racial ills ever southward. Vanity and easy judgment always seem to go together. Up North, Southern transplants routinely squeeze the Dixie accent out of themselves, just to deflect the pompous, soul-killing assumptions of Northern strangers. And I recall one particular Yankee megabrain bragging to me about snubbing an airplane seat-mate because she was from North Carolina. There were many terms to describe this action of hers, none of them nice, and maybe I should have offered her a few of them. But I swear, I was just too gob-smacked to speak.

Going farther: the most vicious, unabashed racial invective I have ever heard from whites I heard up North. It's instructive to recall that the most intense hatred that Martin Luther King said he ever encountered was not in Alabama or Mississippi but in Chicago, when he marched for housing rights; also, that slaves had a major role in building that great Northern economic engine, New York City; also, that at the Ku Klux Klan's peak in the 1920's, it boasted claverns from Maine to Washington State (where a highway was named for Jefferson Davis) and was most powerful of all in Indiana, where maybe 30% of white male residents wore the hood. Nearly 40,000 Klansmen lived in Detroit alone.

That said, the portrayal of "states' rights" as the war's main point has always left a gaping question: What state right are we talking about? Which one was perceived as being under threat? The right of who to do what—and to whom? Another question pretty much flushes it out: What was it about Abraham Lincoln that triggered secession? The well-documented answer: not that he proposed to abolish slavery, but that he opposed its expansion. That and not any plausible threat of Emancipation was enough to make eleven states secede and launch four years of slaughter. True it might be that most Confederate soldiers owned no slaves (about one in ten—they were young, after all, and didn't own much of anything; for white Southern households, though, the figure was nearly one in three) and fought primarily "because ya'll are down here." But little guys only fight wars, they don't start them. For starting them, credit nearly always goes to wealthy non-combatants—those who effectively dress up their material interests as "custom" or "tradition," as chivalric honor or regional pride.

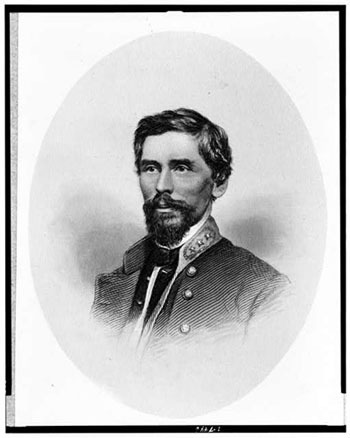

Some demonstrably noble men fought for the Confederacy. On the subject of race, a few of them were even several clicks ahead of the average Caucasian, North or South. One of them was surely Major-General William Mahone, whose counter-attacks at the Battle of the Crater inflicted a heavy federal defeat and killed a lot of Union boys, many of them black. In the early 1880's, however, he formed the Readjuster Party in Virginia, a bi-racial coalition of liberal Republicans and Democrats, meant to reduce the state's crushing debt but also to oppose the white planter elite. It advocated public funding for both black and white schools and an end to the poll tax. Though he was elected Senator, Mahone's party enjoyed only a few years' success before the forces of white supremacy crushed it. And there was Major-General Pat Cleburne, "The Stonewall Of The West," about whom I have written previously: (https://www.goodreads.com/author_blog...). Observing the South's dire manpower shortage and admiring the performance of black Union troops, Cleburne proposed that male slaves be freed in exchange for their enlistment in the Confederate cause. Irish-born and a relative outsider, Cleburne had never realized how intertwined that cause was with slavery and with white-supremacist doctrine—which is why his proposal met with awkward silence and complete inaction. No argument and no arithmetic concerning manpower could overcome the narcotic of racial hegemony.

Maj.-Gen. Pat Cleburne, out of step with

his fellow Confederates on the subject of

slavery. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Recently I was perusing a friend's book of family history and came upon this entry: "Captain Thomas Ebenezer Cummings was killed on Sept. 11, 1864 in the battle of Jonesboro near Atlanta, Georgia, after fighting three years for states' rights, not for slavery." It made me recall a bumper-sticker I saw a decade ago, bearing the image of the battle flag: "Sons of Confederate Veterans Against Racism." There is real poignance to this belief, no doubt utterly sincere—that a man's motivating fire can be kept separate from the general conflagration, and that his descendants can point to it as if this were all that mattered. Still, if the South's cause was based just on lofty notions of self-rule, it must be asked . . .

Why did South Carolina's statement of secession—the very first—complain that the North had "denounced as sinful the institution of slavery" and "encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes?" Why did it blast Lincoln as someone "whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery?" And why did Mississippi's statement of secession declare, "Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material interest in the world?" And why did Texas's statement of secession target the very notion of racial equality, blowing hard about the North's "unnatural feeling of hostility to these Southern States and their beneficent and patriarchal system of African slavery, proclaiming the debasing doctrine of equality of all men, irrespective of race or color—a doctrine at war with nature, in opposition to the experience of mankind, and in violation of the plainest revelations of Divine Law?"

Why in his infamous "Cornerstone Speech" did Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens feel it necessary to affirm "the great truth that the negro is not the equal of the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition"—and to declare his government "the first, in the history of the world, based on this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth?" And why, in the post-war years, were prominent ex-Confederates like Jubal Early so bent on imposing Jim Crow laws, meant to approximate black slavery as closely as possible? Thus there should be no wonder at all why the Confederate Battle Flag enjoyed a resurgence in the late 1950's-early 60's, when resistance to the Civil Rights Movement had it flying all across the South, including the grounds and domes of state houses—or that before hometown crowds, segregationist politicians liked nothing more than to invoke their Rebel forebears.

Nothing is more subjective than a cultural symbol, flags in particular. That is why we'd never expect a Nicaraguan to feel the same swell of emotion that an American does before the Stars 'n' Stripes, or a Pakistani to feel as an Englishman does before the Union Jack. Emotions are fully real to whoever is feeling them; they are not subject to rational justification. But when you choose to fly a flag—or build a monument, or name a park, or name a school, or design a license plate—you are publicly honoring whatever it represents. You are implying that the whole community should do likewise, if only by acquiescence. And that is when something more than sentiment is required. That is when you need a factual basis that justifies the honor.

Children in the ruins of Charleston, SC, 1865. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

For many white Southerners, the Confederate flag conjures proud defiance and the image of a magnificent gray army. Well, that's factual enough—the South was proudly defiant, its army one of the greatest in world history. Over the decades, along with dyed-in-the-wool racists, plenty of people have displayed the emblem without nasty intent—for nothing more specific than that prideful jolt, or a poke in the North's judging eye (think Lynyrd Skynyrd). It's when we go deeper and wider that the trouble starts. There are tons more quotes like the ones I gave above, each of them reinforcing a bedrock truth: slavery and white supremacy were central to the Confederacy's aims, the main reasons for its birth. Its banners were soaked in a poison wellspring. The battle flag did not "come to stand for racism" in recent times, as some in the media have suggested, but stood for it from the get-go—whatever benign meanings were projected onto it later. Long-term unawareness of this requires a truly impressive degree of denial and avoidance.

The Klan and the neo-Nazis require no such denial and avoidance. They embrace the flag's historically based meaning and wave it all the time—it represents their whole program, after all. They are tapped into its dark essence, as is the Charleston shooter, as are the toxic websites that inspired him. In the wake of the massacre, defenders of the flag complained that the murderer had "misused" or "hijacked" it. Far more accurate it would be to say he blew the cover on it, tore wide open a sentimental falsehood. Whenever the flag is hoisted over some state house—that is when it's being misused.

"Political correctness" has long been the right's go-to explanation for anything it doesn't like, a rubber stamp for easy dismissal. In lefty enclaves, PC culture does exist with its simplistic assumptions, its censoring reflex and attendant smugness. (I think every college freshman orientation should include discourse on the First Amendment and its historical relevance.) But the right has its own, better-funded and more conspicuous brand of PC—whole sets of received wisdom, zealously guarded—of which spotless Southern triumphalism is just one aspect. When a government endorses a flag with this kind of documented historical baggage, it promotes that baggage, whether or not it denies the existence of same. How welcome and respected is a black resident supposed to feel, with his/her home state's government so visibly celebrating an epic pro-slavery enterprise? "It's complicated," you often hear—and if they're talking about the whole tragic saga with its social mosaic, political cross-currents and personalities, it sure is. The South itself is complicated—downright byzantine, in ways that are both endearing and exasperating. But there's nothing complicated about what should be done here. That part is pretty straightforward.

As for private citizens who keep flying the battle flag—yes, that's free speech, no way around it. But it's telling that it has become less and less common, no longer mainstream. To be born white in the modern South is, for a great many, to be born up to your eyeballs in black culture, with black friends and acquaintances never far. Some awareness of their feelings and perspectives is bound to seep through eventually, and often has. And sometimes that awareness reaches a tipping point, as I believe it did in 2001, when Georgia voters erased the Confederate emblem from their state flag. Or just two weeks ago, when the State of Alabama quietly ran it down the pole and stashed it away.

Whatever the case, 2015 finds us way past the point where the flag can be plausibly defended. Anyone who chooses to display it should not be (or act) surprised—and above all, should not act somehow persecuted—when fellow Americans of all races react against it, white Southerners included. They will do so from solid historical fact, something that no amount of fabrication and propaganda can ever bury. Apart from the memory of the Charleston Nine and apart from the Declaration of Independence, if there is just one thing we can focus on to guide us, I would suggest that Alexander Stephens quote about the Confederacy's founding truths, so self-evident to him: "the negro is not the equal of the white man; slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition." Let that one echo, and the whole flag issue will be an easy call.

Published on July 04, 2015 00:39

•

Tags:

bernie-mackinnon, charleston-nine, civil-war, confederate-battle-flag, jubal-early, lucifer-s-drum, rebel-flag

From Lucifer's Drum: The Battle Of Monocacy

On this day in 1864, at the Monocacy River near Frederick, MD, a Union force under Major General Lewis "Lew" Wallace faced a considerably larger Confederate force under Lieutenant General Jubal Early. Though defeated, the federals succeeded in delaying Early's drive toward Washington, D.C.—the historical centerpiece of my novel Lucifer's Drum—for a precious twenty-four hours.

The Indiana-born Wallace led a busy and distinguished life. From small-town lawyer and Republican operative, he rose to major general in the Civil War—the Union's youngest, at the time—after which he served as governor of New Mexico Territory and then as U.S. minister to the Ottoman Empire. A writer of historical fiction, he gained lasting fame with the 1880 publication of Ben Hur, which surpassed even Uncle Tom's Cabin in sales and became the best-selling American novel of the 19th Century.

Major General Lew Wallace, USA (1827-1905). (Courtesy:

Library Of Congress)

His role in the war was more checkered, however. After Ulysses S. Grant's close call at the Battle of Shiloh, he charged Wallace with tardiness in moving his reserves forward. (Many years later, writing his memoirs and near death from cancer, Grant would be presented with new evidence from the battle and publicly retract his complaint.) Over the next two years, Wallace found himself exiled to a series of quiet sectors far behind the front lines. Though restored to active duty in March 1864, he was again given a relatively sedate appointment, commanding the VIII Corps at Baltimore. But it was in this capacity that he performed his greatest service to the nation, when Early's invasion of Maryland yanked him out of the doldrums.

Wallace never lacked for initiative. Not waiting for orders from the unaccountably listless War Department, he sped to meet Early's 14,000 rebels at the riverside rail hub of Monocacy Junction. With most of his corps sent to the epic bloodbath in eastern Virginia, he commanded a force less than 6,000 strong, comprised of green "hundred-day" volunteers but also—crucially—two brigades from the battle-hardened VI Corps, under Brigadier General James Ricketts. (Grant had sent them, spurred by the news of Harper's Ferry and Martinsburg being captured.) There was also a small Illinois cavalry detachment under Lieutenant Colonel David Clendenin.

In this gaping hour, these were the only defenders between Early and Washington City. Wallace apprised Army Chief of Staff General Henry Halleck of Early's apparent intentions, and Halleck wired Grant to rush reinforcements to the weakly garrisoned capital. For these to arrive in time, Wallace and his men would have to put up the fight of their lives—which they did on that hot Saturday, for nine blistering hours. Ricketts' left wing bore most of the fighting and eventually collapsed beneath the Confederate onslaught. In the Union center and on the right, having fiercely defended two vital bridgeheads, less experienced units at last had to race back across the river as the attackers bore down. In nearby Frederick, meanwhile, Early secured a $200,000 "levy"—a ransom from civic leaders, against the town being torched.

Lieutenant General Jubal Early, CSA (1816-1894).

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Wallace's troops began a limping retreat toward Baltimore, leaving hundreds of dead across the rolling farmland. But they had cost Early a full day's march. On July 11, Early's straggling, sun-beaten raiders reached the capital's fortified perimeter and started probing it. He did not launch his main assault until the next day, at Fort Stevens—and ran up against the rest of Major General Horatio Wright's VI Corps, which had in fact arrived just in time. Early withdrew his force the day after, headed back to the Shenandoah Valley. Union elements pursued but did not catch him.

Margaret Leech wrote in her classic Reveille In Washington, "It was only in contemplation of what might have been that Wallace's stand on the Monocacy assumed the proportions of a deliverance . . . Washington shuddered at a narrow escape." Upon hearing of Wallace's defeat, Grant replaced him as corps commander but soon reinstated him, when his role in saving the capital became clear. In his memoirs, Grant would write, "If Early had been but one day earlier, he might have entered the capital before the arrival of the reinforcements I had sent . . . General Wallace contributed on this occasion by the defeat of the troops under him, a greater benefit to the cause than often falls to the lot of a commander of an equal force to render by means of a victory."

Lucifer's Drum depicts Lew Wallace as a friendly acquaintance of my central character, federal agent Nathaniel Truly, with whom he shares a passion for literature. But it depicts the Monocacy battle from the perspective of Jubal Early. Here it is:

MONOCACY RIVER, MARYLAND, JULY 9

From the town of Frederick, Early’s party rode southeastward along the Washington Pike. Ahead of them, the artillery duel grew louder, resounding over the lush summer farmland. One river bend and then another appeared, intermittently brilliant beneath the high sun, while drifting white smoke marked the battle front. Early turned off the macadam surface, entered a pasture and slowed to a halt, digging for his field glasses. The others reined up around him.

“That’s a mighty strong position,” Sandie Pendleton observed.

At first, Early did not entirely grasp it as he peered at the enemy center. Ramseur’s men had swept through Frederick a few hours ago and were now pushing across wheatfields along the railroad spur. Before them, offering desultory fire, Yankee skirmishers fell back toward the sluggish Monocacy. On the river’s near bank, a tight bluecoat formation guarded a railroad bridge where the spur and the main B & O line merged, continuing eastward. A stone’s throw to the right, a similar formation shielded a covered bridge that served the pike. A fortified blockhouse stood between the bridges, anchoring the whole position like a spike-head while, on the far bank, other Yankee elements waited to frustrate any crossing.

From the north, a clatter of small arms told him that Rodes had deployed, pressing the enemy right wing astride the Baltimore Pike. But the main assault would have to be against the left, to secure the route to Washington. Scanning that way, Early saw that the Union commander had anticipated well, placing the bulk of his infantry along hilly ground east of the river.

Early handed Pendleton the glasses. “Your eyes are younger. Tell me if you see any sign of reserves back there.”

The adjutant gazed for half a minute. “None, Genr’l. Not in large numbers. I’d estimate their total strength at seven, maybe eight thousand.”

“That sounds right to me.” Taking the glasses back, Early gestured south. “If we can get a division or more across, then extend our right and mount a strong attack, they’ll have to change fronts in order to face it. At which point we can exploit any confusion and roll ‘em up.”

Two other staff officers had dismounted and gotten out the map, each holding a side of it. One traced the Monocacy with his finger. “Don’t see any fords or bridges that way, sir. None that’s close enough, according to this.”

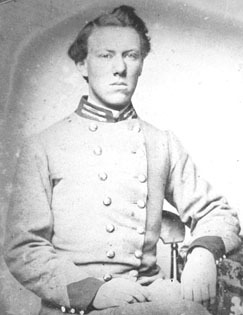

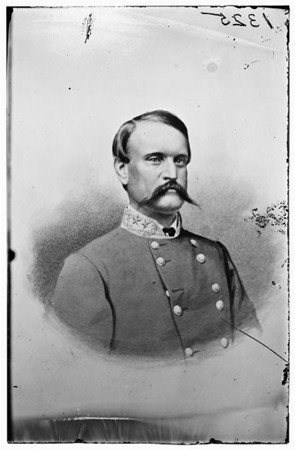

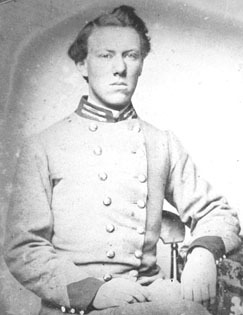

Lieutenant Colonel Alexander "Sandie"

Pendleton, CSA, (1840-1864), aide to

Early, said to have been the finest staff

officer on either side. (Courtesy: Library

of Congress)

“There must be one, damn it! We need scouts. Anyone know if McCausland’s back yet?”

“Barring any real troubles, he ought to be,” said Pendleton.

Early scowled. Too often, with McCausland, “ought to be” fell shy of “is.” The cavalryman’s assignment had been simple enough: cut telegraph wires, rip up more of the B & O and then return as fast as possible. “We’ll have to do our own scouting, then. Let’s get at it.”

The party rode on, turning down a divergent road. The road and tracks ran parallel to the river until, separately, they bridged a curling creek. On the creek’s near side, Breckinridge’s corps lay in wait. Early signaled a halt. From a grassy rise across the river, a Yankee battery let loose and frightened the horses. Early nearly dropped the glasses as he steadied his mount, wondering if they were out of range.

“Genr’l–look yonder!” Pendleton pointed.

From the west, along the creek’s far side, Early saw a cloud of dust and then flapping guidons, followed by a large body of horsemen: McCausland’s battalion. They crossed the road and then the tracks, headed straight for the Monocacy. Through the glasses, Early watched as three lead riders—tawny men in buckskin, probably Cherokee—reached the creek’s point of confluence and dismounted, then waded into the mud-brown river. The water came up only to their waists. Holding their carbines high, two of the scouts kept on while the remaining one motioned for the rest to follow. Rider after rider dismounted, plunged in and started wading toward the opposite bank.

Brigadier General "Tiger" John McCausland, CSA (1836-1927).

An object of Early's repeated scorn, he performed magnificently

at Monocacy. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

“God-a-mighty!” cried Early. “He’s gone and done something right!” Checking the Yankee gun, he saw its crew manhandling it to a new position while some infantry moved up, lying on their stomachs or crouching. Again Early peered downriver. McCausland was holding back about a third of his brigade to tend the riderless horses. The rest of his men continued to pour across, vanishing into foliage along the Monocacy’s east bank. Not far beyond it, they began to reappear in a gently sloping cornfield. With sabers, carbines and pistols drawn, the wet troopers were forming a battle line. Near their right, an enemy shell sent up a spout of earth.

“Foot charge,” Early muttered.

Another shell struck in front of McCausland’s line, but with no sign of faltering it started through the corn. Onward it pushed, quick and then double-quick, headed for the battery atop the grassy rise. An enemy fusillade crackled. Several gray-clad bodies fell but the rest surged on, their order commendable as a shell sailed over their heads and exploded uselessly. Thinking of McCausland, Early granted himself some credit. Since Lynchburg he had made his disapproval of the cavalry chief well known, thereby holding him to a stern standard. Surely it had helped drive McCausland to this startling deed of valor, rash though it was. And at least a suitable ford had been located. Early passed the glasses to Pendleton. From his saddlebag he took a pencil, a book and a piece of writing paper. The book was a signed gift from Jackson, a collection of religious essays which Early had never even glanced at; its cover provided a writing surface.

“Pendleton—Gordon’s division is closest down there, correct?”

“Yes, Genr’l . . . My God, they’re going to take the battery!”

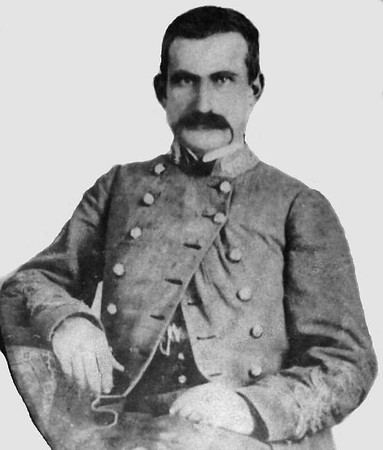

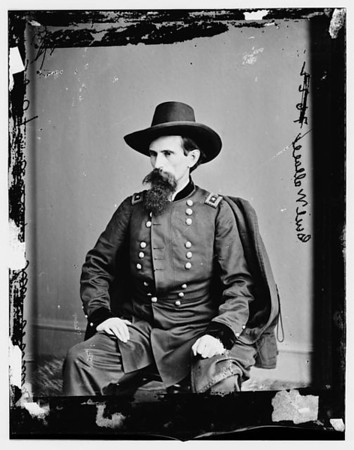

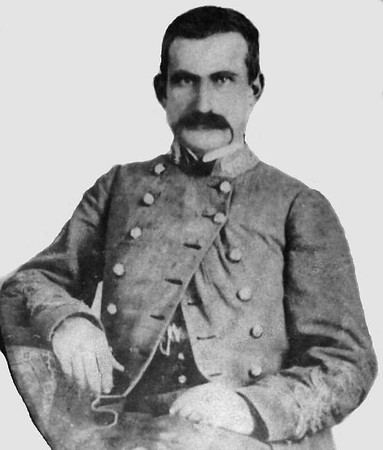

Major General John Brown Gordon,

CSA (1832-1904). One of the war's

greatest field commanders, he

survived five wounds at Antietam.

(Courtesy: National Archives and

Records Administration)

Early looked up. Even without the glasses, he could see that the Yankee gun crew had fled. The supporting infantry began to waver, their volleys degenerating to random pops as McCausland’s men broke out of the cornfield, closing the last fifty yards. The bluecoats retreated. The gray troopers swarmed over the rise, a few stopping to turn the gun on the enemy.

“Bully for them!” cried one officer.

Pendleton shook his head. “They can’t hold it. Without support, they’ll be driven back.”

Even as the adjutant said this, a solid line of blue materialized along a ridge farther on. The retreating Yankees halted, rallying as the new line swept down from the ridge. Before the counterattack, the Confederates finally stalled, spitting fire as they lurched back toward the captured gun. The gun’s would-be crew gave up trying to fire it and rejoined the fight.

“McCausland will get his support,” Early declared. He finished writing his dispatch and handed it to a lieutenant. “To Gordon—fast. And ask Breckinridge to join us, if he’s ready.”

The lieutenant galloped down the road.

Early jotted a second note, this one ordering up a couple of General Long’s batteries. A second junior staffer took it and rode off. Now there was little to do but wait and watch. Dismounting, Early unbuttoned his tunic, and most of the others followed suit. Pendleton stayed mounted, gazing across the river as McCausland’s men fought on, disputing every blade of grass. With its flanks threatened and men dropping, the battalion fell back to the rise in fair order.

In this painting by Keith Rocco, Ricketts' troops try to stop Gordon's advance at the

Battle of Monocacy. (Courtesy: National Park Service)

Down by the creek, dust stirred as Gordon’s division lumbered forth, leaving gear strewn and tents unstruck. Within minutes, platoons and whole companies were splashing across the ford, rifles held aloft, men wading waist-deep to the east bank and pawing their way up.

“Gordon always gets ‘em moving,” said Pendleton.

Early gave his adjutant a glance. On the noble, long-chinned face, a smile had surfaced—an admiring smile for Gordon. Everyone seemed to admire the fierce son of Georgia. Raising the glasses, Early grunted—"That’s only what’s expected of him.” Down by the ford, the red-shirted Gordon was easy to spot atop his black charger, urging his men across. He did look fine.

Tending the horses on the west bank, McCausland’s remaining men could only watch while, on the east side, their hard-pressed comrades fought to buffer Gordon’s movement. Nevertheless the infantry too drew fire as it fanned out and deployed in echelon. By the railroad, one of Long’s Napoleons unlimbered and commenced shelling, while another was rolled with some difficulty across the ford.

Swift and efficient though the crossing had been, time slowed as Gordon’s still-forming division began sidling to the right. The sun grew hotter. Early paced, stroking his beard and chewing his tobacco. Looking at his pocket watch—one o’clock already—he wondered how things were progressing back in Frederick. There, under the eyes of a Confederate officers’ delegation, town fathers were scrambling to raise two hundred-thousand dollars from the citizenry. Early hoped the effort would succeed. Torching the town would cause more delay, given that so many of its homes were of brick. And a wagon full of Yankee gold would please Richmond.

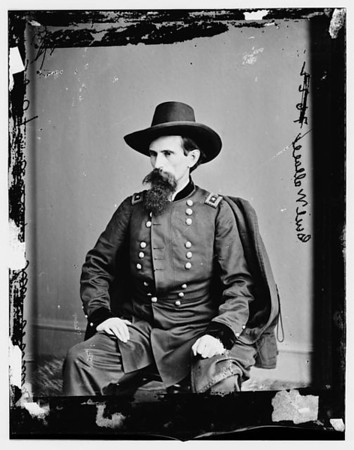

Brigadier General James Ricketts, USA

(1817-1887), whose two brigades bore

the brunt of the Confederate attack at

Monocacy. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

At the rail junction upriver, the cannonade and rifle clash had intensified. Scanning that way, Pendleton rose in his stirrups. “Genr’l, they’ve fired the bridge. The blockhouse too.”

Early seized the glasses and observed twin columns of black smoke rolling skyward, flames leaping from the blockhouse and the covered bridge. Under steady fire, Ramseur’s men moved in. The federal center had withdrawn across the Monocacy, though it still held the iron railroad bridge. “Fine,” said Early. “Billy Yank is good and nervous.”

He swung his gaze back to Gordon’s division, still maneuvering slowly to the south, its extreme right having vanished beyond some woods. The Union line had moved forward in that sector, thinning as it strained to meet the threat. Mounted officers cantered back and forth, gesticulating. Sweeping the higher ground, Early realized the full difficulty of the command he had given. A network of wooden rail fences traversed the sloping fields; studding the fields were stacks of harvested grain, like orderly brown hillocks. When the Yankees inevitably pulled back, these would obstruct attack while supplying good defensive cover.

The two couriers returned, soon followed by Breckinridge and his staff. The Kentuckian announced that his other divisional chief, John Echols, was preparing to lend any needed support. He had no sooner said this when an eruption of shell and musketry heralded Gordon’s assault. Mounting for a better view, Early saw a thin curtain of skirmishers appear from the trees. Massed infantry followed—so dense, for an instant, that it looked like a surge of gray lava. Fire flashed from the Union line. The oncoming brigades slowed but did not pause, pouring out and expanding in a great wave—rifles bristling, blades gleaming, flags like ship-masts in the smoke. The roar of guns stoked the general thunder, a pummeling monotony that devoured the minutes.

Two hours later, with the entire Union left collapsing, Early rode with Breckinridge and the others toward the rail junction. They had drawn alongside the tracks when Early dug his spurs in and broke ahead. In the smoke and flash from across the river, he caught jarred glimpses of the enemy in reeling retreat. His back felt nothing. Like a dream of youth, his whole body sang and he heard himself cackle. “Go it!” he yelled. “Go it, Gordon!” The breeze having shifted, black smoke traveled down from the blockhouse and the covered bridge and began to obscure his vision. The din of war enveloped him: the cataract of rifles, the whistle of minie-balls, the yells and screams, the shell shriek and cannon thunder. And through and above it all, floating, that Rebel cry—shrill as falcons, ice to the spine, the sound of one nightmare engulfing another. Tossing his head back, Early crowed.

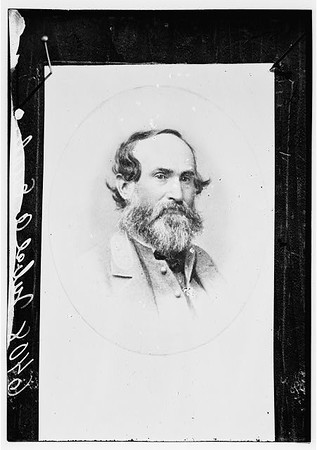

Major General John Cabell Breckinridge, CSA

(1821-1875). Early's second-in-command on

the drive toward Washington, D.C., he had

served as U.S. congressman, senator and

vice-president. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

He emerged coughing from the smoke. Slowing his horse, he saw federals flying back across the eastward rail line, Confederates scrambling over the last fences in pursuit. Up at the junction, Yankee artillery had gone silent. Early stopped and got out his binoculars. He watched Ramseur’s men pour across the river shallows and the iron bridge, the enemy center crumbling. Early’s staff clustered around him, all nods and smiles. At the head of Ramseur’s skirmish line he spied a familiar tan horse, its rider waving his hat in celebration. Kyd Douglas had evidently joined the final assault, spurning his duties as Frederick’s provost marshal. Three thoughts struck Early at once: he could court-martial Douglas; he would not court-martial him; he would have liked having a son like him—brave, capable, insufficiently solemn.

“Lord above, Gordon’s a wonderment!” someone exclaimed.

Pulled from his reverie, Early cleared his throat and turned to Pendleton. “Head back to Frederick. Find out about the levy. If they’re still stalling, prepare to fire the town.”

“I don’t think they’ll need convincing now,” said Pendleton, heading off.

Soon afterward, Early was riding among Gordon’s sweaty, powder-blackened infantry as they gathered prisoners. Some stopped to jeer Echols’ men as they streamed tardily past. To the north, stuttering rifle fire persisted. Corpses littered the fields and hillsides and dangled from fences, with carrion birds circling above. Along the riverbank, commandeered boats ferried wounded to the Frederick side, where they were loaded into ambulance wagons.

(Below: a trailer link for the 2006 docu-drama "No Retreat From Destiny: The Battle That Rescued Washington," from Lionheart Filmworks.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zWRpT...

Early’s staff had dispersed for the moment. In the middle distance, Gordon sat atop his charger, looking more grim than triumphant. Breckinridge rode up to him, hand extended in congratulation. Closer by, Early recognized one of Gordon’s aides, a gangly major who was supervising the collection of dead. At Early’s approach, the major gave a dazed salute.

“What can you tell me about your losses?” Early demanded.

The major looked side to side. “I’d reckon about a third of the division, sir.”

Early gazed down the row of outstretched bodies, some already bloating in the heat—limbs stiff and clothes disheveled, some with eyes wide to the afternoon sun, mouths open as if they had died in conversation. Even the bearded ones looked no older than twenty.

“Make sure to collect weapons and cartridges,” said Early. “Shoes, too.”

Squinting up, the major seemed to sway a bit. “Yessir, Genr’l.”

Early watched a cartload of captured flags and rifles roll by. Hanging over the side, a white-and-blue guidon caught his eye. “Hold up there!” he called. The teamster yanked the reins. Leaning down from his horse, Early grabbed the little flag by its swallowtail and examined it. It displayed the Greek Cross. Waving the teamster on, he watched a line of guarded prisoners stumble by, some of them daring an upward glance at their conqueror. He eyed the badges on their caps—again, the Greek Cross. A set of hoofbeats distracted him, and he turned to see Breckinridge cantering up.

(Below: a link for a video on the Battles of Monocacy and Fort Stevens, with historian Marc Leepson.)https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OFQVp...

“Where’s Gordon?” Early asked.

“Gone back to town,” said Breckinridge. “To personally check on medical supplies. His brother’s badly wounded and so’s his senior brigadier.”

“I see.” Early pointed to the prisoners filing past. “Look at those insignias.”

Breckinridge looked, narrowing his eyes. “The Sixth Corps!”

“Part of it, anyhow,” said Early. “Last seen at Petersburg.”

The Kentuckian smiled. “Then Grant’s pulling troops from the main front.”

Yes, Early thought—and that was good for Lee. Yet it conflicted with what had become Early’s most fearsome hope, his blazing vision of what lay ahead. “If Grant sees the full threat we pose, he’ll be sending the rest of the Sixth. More, possibly. I’d wager they’ll be in Washington mighty soon, if not already. And we can’t afford a bloody repulse.”

Breckinridge mulled it over. “Once we’re there, we can determine enemy strength. If it’s too much, we can withdraw—but we won’t know till then. We’ve just over thirty miles left to go. This fight cost us a day’s march, but the race may still be won.”

However quiet and cryptic Breckinridge had been on the subject of Washington, he seemed game about it now. Boldness was catching. “Very good, then,” said Early, heartened. “And lest we forget, a hidden advantage awaits us.” In his side-vision, soldiers dragged more battered corpses into line. He turned his gaze to the pike, following it till it vanished in the low distant hills. “At dawn, your troops will lead the column out. Drive them hard, Breck. By tomorrow night, we need to be on Washington’s doorstep.”

Monument to the Battle of Monocacy, dedicated

on its 1964 centennial. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

“Then we shall be,” said Breckinridge.

They spent a minute discussing Bradley Johnson’s expedition. Johnson’s eight hundred horsemen had left at sunup, aiming for the Baltimore vicinity and thence down the cape to Point Lookout, where thousands of Southern captives needed liberating. On their way, the troopers would spread more panic and destruction.

Pendleton arrived at a gallop, announcing that Frederick would not have to burn; its leading citizens had agreed to scrounge up the two hundred-thousand in bank loans. Apart from that, the town’s supply depot abounded with clothes, blankets, foodstuffs, medicine and horse livery. Best of all, someone’s cellar had yielded a cache of that rarest delicacy, ice cream, packed in ice and woodchips. “If we head back now, we can get ourselves a heap of it!” cried Pendleton.

Breckinridge chuckled. “A good day for the South, all-round.”

Early grunted agreement. Riding off, he cast another glance toward Washington. The way was open. Everything now depended upon speed—speed and, quite possibly, a single Yankee traitor.

The Indiana-born Wallace led a busy and distinguished life. From small-town lawyer and Republican operative, he rose to major general in the Civil War—the Union's youngest, at the time—after which he served as governor of New Mexico Territory and then as U.S. minister to the Ottoman Empire. A writer of historical fiction, he gained lasting fame with the 1880 publication of Ben Hur, which surpassed even Uncle Tom's Cabin in sales and became the best-selling American novel of the 19th Century.

Major General Lew Wallace, USA (1827-1905). (Courtesy:

Library Of Congress)

His role in the war was more checkered, however. After Ulysses S. Grant's close call at the Battle of Shiloh, he charged Wallace with tardiness in moving his reserves forward. (Many years later, writing his memoirs and near death from cancer, Grant would be presented with new evidence from the battle and publicly retract his complaint.) Over the next two years, Wallace found himself exiled to a series of quiet sectors far behind the front lines. Though restored to active duty in March 1864, he was again given a relatively sedate appointment, commanding the VIII Corps at Baltimore. But it was in this capacity that he performed his greatest service to the nation, when Early's invasion of Maryland yanked him out of the doldrums.

Wallace never lacked for initiative. Not waiting for orders from the unaccountably listless War Department, he sped to meet Early's 14,000 rebels at the riverside rail hub of Monocacy Junction. With most of his corps sent to the epic bloodbath in eastern Virginia, he commanded a force less than 6,000 strong, comprised of green "hundred-day" volunteers but also—crucially—two brigades from the battle-hardened VI Corps, under Brigadier General James Ricketts. (Grant had sent them, spurred by the news of Harper's Ferry and Martinsburg being captured.) There was also a small Illinois cavalry detachment under Lieutenant Colonel David Clendenin.

In this gaping hour, these were the only defenders between Early and Washington City. Wallace apprised Army Chief of Staff General Henry Halleck of Early's apparent intentions, and Halleck wired Grant to rush reinforcements to the weakly garrisoned capital. For these to arrive in time, Wallace and his men would have to put up the fight of their lives—which they did on that hot Saturday, for nine blistering hours. Ricketts' left wing bore most of the fighting and eventually collapsed beneath the Confederate onslaught. In the Union center and on the right, having fiercely defended two vital bridgeheads, less experienced units at last had to race back across the river as the attackers bore down. In nearby Frederick, meanwhile, Early secured a $200,000 "levy"—a ransom from civic leaders, against the town being torched.

Lieutenant General Jubal Early, CSA (1816-1894).

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Wallace's troops began a limping retreat toward Baltimore, leaving hundreds of dead across the rolling farmland. But they had cost Early a full day's march. On July 11, Early's straggling, sun-beaten raiders reached the capital's fortified perimeter and started probing it. He did not launch his main assault until the next day, at Fort Stevens—and ran up against the rest of Major General Horatio Wright's VI Corps, which had in fact arrived just in time. Early withdrew his force the day after, headed back to the Shenandoah Valley. Union elements pursued but did not catch him.

Margaret Leech wrote in her classic Reveille In Washington, "It was only in contemplation of what might have been that Wallace's stand on the Monocacy assumed the proportions of a deliverance . . . Washington shuddered at a narrow escape." Upon hearing of Wallace's defeat, Grant replaced him as corps commander but soon reinstated him, when his role in saving the capital became clear. In his memoirs, Grant would write, "If Early had been but one day earlier, he might have entered the capital before the arrival of the reinforcements I had sent . . . General Wallace contributed on this occasion by the defeat of the troops under him, a greater benefit to the cause than often falls to the lot of a commander of an equal force to render by means of a victory."

Lucifer's Drum depicts Lew Wallace as a friendly acquaintance of my central character, federal agent Nathaniel Truly, with whom he shares a passion for literature. But it depicts the Monocacy battle from the perspective of Jubal Early. Here it is:

MONOCACY RIVER, MARYLAND, JULY 9

From the town of Frederick, Early’s party rode southeastward along the Washington Pike. Ahead of them, the artillery duel grew louder, resounding over the lush summer farmland. One river bend and then another appeared, intermittently brilliant beneath the high sun, while drifting white smoke marked the battle front. Early turned off the macadam surface, entered a pasture and slowed to a halt, digging for his field glasses. The others reined up around him.

“That’s a mighty strong position,” Sandie Pendleton observed.

At first, Early did not entirely grasp it as he peered at the enemy center. Ramseur’s men had swept through Frederick a few hours ago and were now pushing across wheatfields along the railroad spur. Before them, offering desultory fire, Yankee skirmishers fell back toward the sluggish Monocacy. On the river’s near bank, a tight bluecoat formation guarded a railroad bridge where the spur and the main B & O line merged, continuing eastward. A stone’s throw to the right, a similar formation shielded a covered bridge that served the pike. A fortified blockhouse stood between the bridges, anchoring the whole position like a spike-head while, on the far bank, other Yankee elements waited to frustrate any crossing.

From the north, a clatter of small arms told him that Rodes had deployed, pressing the enemy right wing astride the Baltimore Pike. But the main assault would have to be against the left, to secure the route to Washington. Scanning that way, Early saw that the Union commander had anticipated well, placing the bulk of his infantry along hilly ground east of the river.

Early handed Pendleton the glasses. “Your eyes are younger. Tell me if you see any sign of reserves back there.”

The adjutant gazed for half a minute. “None, Genr’l. Not in large numbers. I’d estimate their total strength at seven, maybe eight thousand.”

“That sounds right to me.” Taking the glasses back, Early gestured south. “If we can get a division or more across, then extend our right and mount a strong attack, they’ll have to change fronts in order to face it. At which point we can exploit any confusion and roll ‘em up.”

Two other staff officers had dismounted and gotten out the map, each holding a side of it. One traced the Monocacy with his finger. “Don’t see any fords or bridges that way, sir. None that’s close enough, according to this.”

Lieutenant Colonel Alexander "Sandie"

Pendleton, CSA, (1840-1864), aide to

Early, said to have been the finest staff

officer on either side. (Courtesy: Library

of Congress)

“There must be one, damn it! We need scouts. Anyone know if McCausland’s back yet?”

“Barring any real troubles, he ought to be,” said Pendleton.

Early scowled. Too often, with McCausland, “ought to be” fell shy of “is.” The cavalryman’s assignment had been simple enough: cut telegraph wires, rip up more of the B & O and then return as fast as possible. “We’ll have to do our own scouting, then. Let’s get at it.”

The party rode on, turning down a divergent road. The road and tracks ran parallel to the river until, separately, they bridged a curling creek. On the creek’s near side, Breckinridge’s corps lay in wait. Early signaled a halt. From a grassy rise across the river, a Yankee battery let loose and frightened the horses. Early nearly dropped the glasses as he steadied his mount, wondering if they were out of range.

“Genr’l–look yonder!” Pendleton pointed.

From the west, along the creek’s far side, Early saw a cloud of dust and then flapping guidons, followed by a large body of horsemen: McCausland’s battalion. They crossed the road and then the tracks, headed straight for the Monocacy. Through the glasses, Early watched as three lead riders—tawny men in buckskin, probably Cherokee—reached the creek’s point of confluence and dismounted, then waded into the mud-brown river. The water came up only to their waists. Holding their carbines high, two of the scouts kept on while the remaining one motioned for the rest to follow. Rider after rider dismounted, plunged in and started wading toward the opposite bank.

Brigadier General "Tiger" John McCausland, CSA (1836-1927).

An object of Early's repeated scorn, he performed magnificently

at Monocacy. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

“God-a-mighty!” cried Early. “He’s gone and done something right!” Checking the Yankee gun, he saw its crew manhandling it to a new position while some infantry moved up, lying on their stomachs or crouching. Again Early peered downriver. McCausland was holding back about a third of his brigade to tend the riderless horses. The rest of his men continued to pour across, vanishing into foliage along the Monocacy’s east bank. Not far beyond it, they began to reappear in a gently sloping cornfield. With sabers, carbines and pistols drawn, the wet troopers were forming a battle line. Near their right, an enemy shell sent up a spout of earth.

“Foot charge,” Early muttered.

Another shell struck in front of McCausland’s line, but with no sign of faltering it started through the corn. Onward it pushed, quick and then double-quick, headed for the battery atop the grassy rise. An enemy fusillade crackled. Several gray-clad bodies fell but the rest surged on, their order commendable as a shell sailed over their heads and exploded uselessly. Thinking of McCausland, Early granted himself some credit. Since Lynchburg he had made his disapproval of the cavalry chief well known, thereby holding him to a stern standard. Surely it had helped drive McCausland to this startling deed of valor, rash though it was. And at least a suitable ford had been located. Early passed the glasses to Pendleton. From his saddlebag he took a pencil, a book and a piece of writing paper. The book was a signed gift from Jackson, a collection of religious essays which Early had never even glanced at; its cover provided a writing surface.

“Pendleton—Gordon’s division is closest down there, correct?”

“Yes, Genr’l . . . My God, they’re going to take the battery!”

Major General John Brown Gordon,

CSA (1832-1904). One of the war's

greatest field commanders, he

survived five wounds at Antietam.

(Courtesy: National Archives and

Records Administration)

Early looked up. Even without the glasses, he could see that the Yankee gun crew had fled. The supporting infantry began to waver, their volleys degenerating to random pops as McCausland’s men broke out of the cornfield, closing the last fifty yards. The bluecoats retreated. The gray troopers swarmed over the rise, a few stopping to turn the gun on the enemy.

“Bully for them!” cried one officer.

Pendleton shook his head. “They can’t hold it. Without support, they’ll be driven back.”

Even as the adjutant said this, a solid line of blue materialized along a ridge farther on. The retreating Yankees halted, rallying as the new line swept down from the ridge. Before the counterattack, the Confederates finally stalled, spitting fire as they lurched back toward the captured gun. The gun’s would-be crew gave up trying to fire it and rejoined the fight.

“McCausland will get his support,” Early declared. He finished writing his dispatch and handed it to a lieutenant. “To Gordon—fast. And ask Breckinridge to join us, if he’s ready.”

The lieutenant galloped down the road.

Early jotted a second note, this one ordering up a couple of General Long’s batteries. A second junior staffer took it and rode off. Now there was little to do but wait and watch. Dismounting, Early unbuttoned his tunic, and most of the others followed suit. Pendleton stayed mounted, gazing across the river as McCausland’s men fought on, disputing every blade of grass. With its flanks threatened and men dropping, the battalion fell back to the rise in fair order.

In this painting by Keith Rocco, Ricketts' troops try to stop Gordon's advance at the

Battle of Monocacy. (Courtesy: National Park Service)

Down by the creek, dust stirred as Gordon’s division lumbered forth, leaving gear strewn and tents unstruck. Within minutes, platoons and whole companies were splashing across the ford, rifles held aloft, men wading waist-deep to the east bank and pawing their way up.

“Gordon always gets ‘em moving,” said Pendleton.

Early gave his adjutant a glance. On the noble, long-chinned face, a smile had surfaced—an admiring smile for Gordon. Everyone seemed to admire the fierce son of Georgia. Raising the glasses, Early grunted—"That’s only what’s expected of him.” Down by the ford, the red-shirted Gordon was easy to spot atop his black charger, urging his men across. He did look fine.

Tending the horses on the west bank, McCausland’s remaining men could only watch while, on the east side, their hard-pressed comrades fought to buffer Gordon’s movement. Nevertheless the infantry too drew fire as it fanned out and deployed in echelon. By the railroad, one of Long’s Napoleons unlimbered and commenced shelling, while another was rolled with some difficulty across the ford.

Swift and efficient though the crossing had been, time slowed as Gordon’s still-forming division began sidling to the right. The sun grew hotter. Early paced, stroking his beard and chewing his tobacco. Looking at his pocket watch—one o’clock already—he wondered how things were progressing back in Frederick. There, under the eyes of a Confederate officers’ delegation, town fathers were scrambling to raise two hundred-thousand dollars from the citizenry. Early hoped the effort would succeed. Torching the town would cause more delay, given that so many of its homes were of brick. And a wagon full of Yankee gold would please Richmond.

Brigadier General James Ricketts, USA

(1817-1887), whose two brigades bore

the brunt of the Confederate attack at

Monocacy. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

At the rail junction upriver, the cannonade and rifle clash had intensified. Scanning that way, Pendleton rose in his stirrups. “Genr’l, they’ve fired the bridge. The blockhouse too.”

Early seized the glasses and observed twin columns of black smoke rolling skyward, flames leaping from the blockhouse and the covered bridge. Under steady fire, Ramseur’s men moved in. The federal center had withdrawn across the Monocacy, though it still held the iron railroad bridge. “Fine,” said Early. “Billy Yank is good and nervous.”

He swung his gaze back to Gordon’s division, still maneuvering slowly to the south, its extreme right having vanished beyond some woods. The Union line had moved forward in that sector, thinning as it strained to meet the threat. Mounted officers cantered back and forth, gesticulating. Sweeping the higher ground, Early realized the full difficulty of the command he had given. A network of wooden rail fences traversed the sloping fields; studding the fields were stacks of harvested grain, like orderly brown hillocks. When the Yankees inevitably pulled back, these would obstruct attack while supplying good defensive cover.

The two couriers returned, soon followed by Breckinridge and his staff. The Kentuckian announced that his other divisional chief, John Echols, was preparing to lend any needed support. He had no sooner said this when an eruption of shell and musketry heralded Gordon’s assault. Mounting for a better view, Early saw a thin curtain of skirmishers appear from the trees. Massed infantry followed—so dense, for an instant, that it looked like a surge of gray lava. Fire flashed from the Union line. The oncoming brigades slowed but did not pause, pouring out and expanding in a great wave—rifles bristling, blades gleaming, flags like ship-masts in the smoke. The roar of guns stoked the general thunder, a pummeling monotony that devoured the minutes.