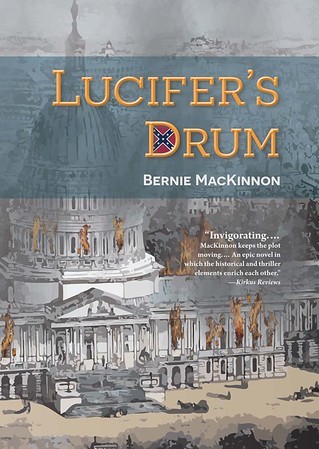

Bernie MacKinnon's Blog - Posts Tagged "lew-wallace"

From Lucifer's Drum: The Battle Of Monocacy

On this day in 1864, at the Monocacy River near Frederick, MD, a Union force under Major General Lewis "Lew" Wallace faced a considerably larger Confederate force under Lieutenant General Jubal Early. Though defeated, the federals succeeded in delaying Early's drive toward Washington, D.C.—the historical centerpiece of my novel Lucifer's Drum—for a precious twenty-four hours.

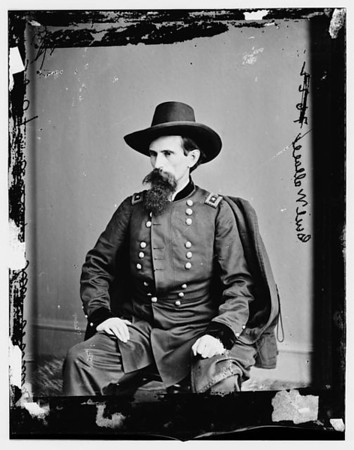

The Indiana-born Wallace led a busy and distinguished life. From small-town lawyer and Republican operative, he rose to major general in the Civil War—the Union's youngest, at the time—after which he served as governor of New Mexico Territory and then as U.S. minister to the Ottoman Empire. A writer of historical fiction, he gained lasting fame with the 1880 publication of Ben Hur, which surpassed even Uncle Tom's Cabin in sales and became the best-selling American novel of the 19th Century.

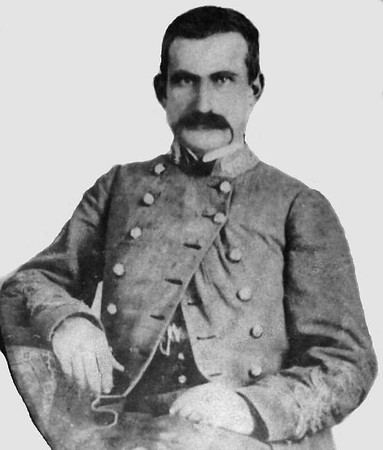

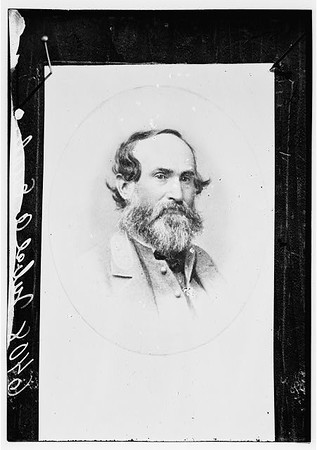

Major General Lew Wallace, USA (1827-1905). (Courtesy:

Library Of Congress)

His role in the war was more checkered, however. After Ulysses S. Grant's close call at the Battle of Shiloh, he charged Wallace with tardiness in moving his reserves forward. (Many years later, writing his memoirs and near death from cancer, Grant would be presented with new evidence from the battle and publicly retract his complaint.) Over the next two years, Wallace found himself exiled to a series of quiet sectors far behind the front lines. Though restored to active duty in March 1864, he was again given a relatively sedate appointment, commanding the VIII Corps at Baltimore. But it was in this capacity that he performed his greatest service to the nation, when Early's invasion of Maryland yanked him out of the doldrums.

Wallace never lacked for initiative. Not waiting for orders from the unaccountably listless War Department, he sped to meet Early's 14,000 rebels at the riverside rail hub of Monocacy Junction. With most of his corps sent to the epic bloodbath in eastern Virginia, he commanded a force less than 6,000 strong, comprised of green "hundred-day" volunteers but also—crucially—two brigades from the battle-hardened VI Corps, under Brigadier General James Ricketts. (Grant had sent them, spurred by the news of Harper's Ferry and Martinsburg being captured.) There was also a small Illinois cavalry detachment under Lieutenant Colonel David Clendenin.

In this gaping hour, these were the only defenders between Early and Washington City. Wallace apprised Army Chief of Staff General Henry Halleck of Early's apparent intentions, and Halleck wired Grant to rush reinforcements to the weakly garrisoned capital. For these to arrive in time, Wallace and his men would have to put up the fight of their lives—which they did on that hot Saturday, for nine blistering hours. Ricketts' left wing bore most of the fighting and eventually collapsed beneath the Confederate onslaught. In the Union center and on the right, having fiercely defended two vital bridgeheads, less experienced units at last had to race back across the river as the attackers bore down. In nearby Frederick, meanwhile, Early secured a $200,000 "levy"—a ransom from civic leaders, against the town being torched.

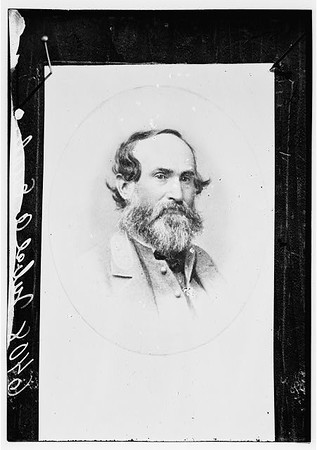

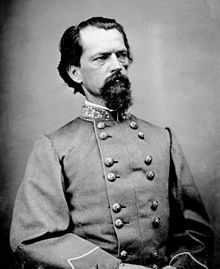

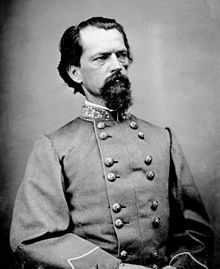

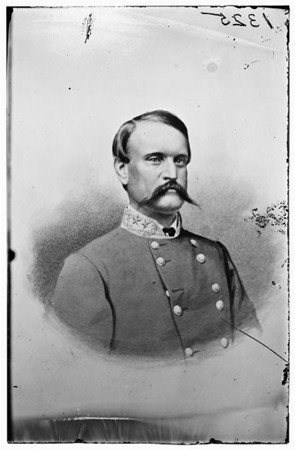

Lieutenant General Jubal Early, CSA (1816-1894).

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Wallace's troops began a limping retreat toward Baltimore, leaving hundreds of dead across the rolling farmland. But they had cost Early a full day's march. On July 11, Early's straggling, sun-beaten raiders reached the capital's fortified perimeter and started probing it. He did not launch his main assault until the next day, at Fort Stevens—and ran up against the rest of Major General Horatio Wright's VI Corps, which had in fact arrived just in time. Early withdrew his force the day after, headed back to the Shenandoah Valley. Union elements pursued but did not catch him.

Margaret Leech wrote in her classic Reveille In Washington, "It was only in contemplation of what might have been that Wallace's stand on the Monocacy assumed the proportions of a deliverance . . . Washington shuddered at a narrow escape." Upon hearing of Wallace's defeat, Grant replaced him as corps commander but soon reinstated him, when his role in saving the capital became clear. In his memoirs, Grant would write, "If Early had been but one day earlier, he might have entered the capital before the arrival of the reinforcements I had sent . . . General Wallace contributed on this occasion by the defeat of the troops under him, a greater benefit to the cause than often falls to the lot of a commander of an equal force to render by means of a victory."

Lucifer's Drum depicts Lew Wallace as a friendly acquaintance of my central character, federal agent Nathaniel Truly, with whom he shares a passion for literature. But it depicts the Monocacy battle from the perspective of Jubal Early. Here it is:

MONOCACY RIVER, MARYLAND, JULY 9

From the town of Frederick, Early’s party rode southeastward along the Washington Pike. Ahead of them, the artillery duel grew louder, resounding over the lush summer farmland. One river bend and then another appeared, intermittently brilliant beneath the high sun, while drifting white smoke marked the battle front. Early turned off the macadam surface, entered a pasture and slowed to a halt, digging for his field glasses. The others reined up around him.

“That’s a mighty strong position,” Sandie Pendleton observed.

At first, Early did not entirely grasp it as he peered at the enemy center. Ramseur’s men had swept through Frederick a few hours ago and were now pushing across wheatfields along the railroad spur. Before them, offering desultory fire, Yankee skirmishers fell back toward the sluggish Monocacy. On the river’s near bank, a tight bluecoat formation guarded a railroad bridge where the spur and the main B & O line merged, continuing eastward. A stone’s throw to the right, a similar formation shielded a covered bridge that served the pike. A fortified blockhouse stood between the bridges, anchoring the whole position like a spike-head while, on the far bank, other Yankee elements waited to frustrate any crossing.

From the north, a clatter of small arms told him that Rodes had deployed, pressing the enemy right wing astride the Baltimore Pike. But the main assault would have to be against the left, to secure the route to Washington. Scanning that way, Early saw that the Union commander had anticipated well, placing the bulk of his infantry along hilly ground east of the river.

Early handed Pendleton the glasses. “Your eyes are younger. Tell me if you see any sign of reserves back there.”

The adjutant gazed for half a minute. “None, Genr’l. Not in large numbers. I’d estimate their total strength at seven, maybe eight thousand.”

“That sounds right to me.” Taking the glasses back, Early gestured south. “If we can get a division or more across, then extend our right and mount a strong attack, they’ll have to change fronts in order to face it. At which point we can exploit any confusion and roll ‘em up.”

Two other staff officers had dismounted and gotten out the map, each holding a side of it. One traced the Monocacy with his finger. “Don’t see any fords or bridges that way, sir. None that’s close enough, according to this.”

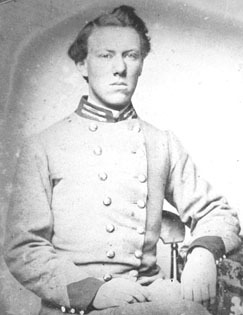

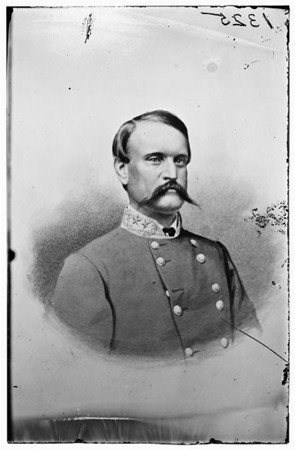

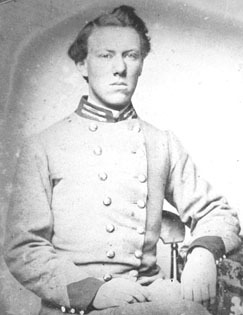

Lieutenant Colonel Alexander "Sandie"

Pendleton, CSA, (1840-1864), aide to

Early, said to have been the finest staff

officer on either side. (Courtesy: Library

of Congress)

“There must be one, damn it! We need scouts. Anyone know if McCausland’s back yet?”

“Barring any real troubles, he ought to be,” said Pendleton.

Early scowled. Too often, with McCausland, “ought to be” fell shy of “is.” The cavalryman’s assignment had been simple enough: cut telegraph wires, rip up more of the B & O and then return as fast as possible. “We’ll have to do our own scouting, then. Let’s get at it.”

The party rode on, turning down a divergent road. The road and tracks ran parallel to the river until, separately, they bridged a curling creek. On the creek’s near side, Breckinridge’s corps lay in wait. Early signaled a halt. From a grassy rise across the river, a Yankee battery let loose and frightened the horses. Early nearly dropped the glasses as he steadied his mount, wondering if they were out of range.

“Genr’l–look yonder!” Pendleton pointed.

From the west, along the creek’s far side, Early saw a cloud of dust and then flapping guidons, followed by a large body of horsemen: McCausland’s battalion. They crossed the road and then the tracks, headed straight for the Monocacy. Through the glasses, Early watched as three lead riders—tawny men in buckskin, probably Cherokee—reached the creek’s point of confluence and dismounted, then waded into the mud-brown river. The water came up only to their waists. Holding their carbines high, two of the scouts kept on while the remaining one motioned for the rest to follow. Rider after rider dismounted, plunged in and started wading toward the opposite bank.

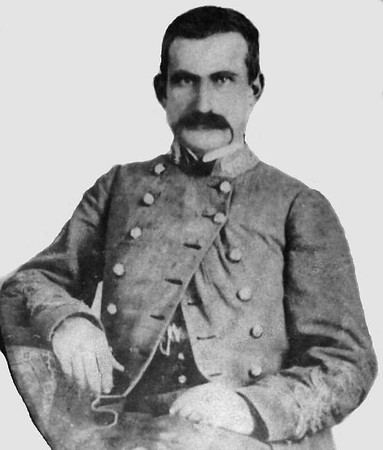

Brigadier General "Tiger" John McCausland, CSA (1836-1927).

An object of Early's repeated scorn, he performed magnificently

at Monocacy. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

“God-a-mighty!” cried Early. “He’s gone and done something right!” Checking the Yankee gun, he saw its crew manhandling it to a new position while some infantry moved up, lying on their stomachs or crouching. Again Early peered downriver. McCausland was holding back about a third of his brigade to tend the riderless horses. The rest of his men continued to pour across, vanishing into foliage along the Monocacy’s east bank. Not far beyond it, they began to reappear in a gently sloping cornfield. With sabers, carbines and pistols drawn, the wet troopers were forming a battle line. Near their right, an enemy shell sent up a spout of earth.

“Foot charge,” Early muttered.

Another shell struck in front of McCausland’s line, but with no sign of faltering it started through the corn. Onward it pushed, quick and then double-quick, headed for the battery atop the grassy rise. An enemy fusillade crackled. Several gray-clad bodies fell but the rest surged on, their order commendable as a shell sailed over their heads and exploded uselessly. Thinking of McCausland, Early granted himself some credit. Since Lynchburg he had made his disapproval of the cavalry chief well known, thereby holding him to a stern standard. Surely it had helped drive McCausland to this startling deed of valor, rash though it was. And at least a suitable ford had been located. Early passed the glasses to Pendleton. From his saddlebag he took a pencil, a book and a piece of writing paper. The book was a signed gift from Jackson, a collection of religious essays which Early had never even glanced at; its cover provided a writing surface.

“Pendleton—Gordon’s division is closest down there, correct?”

“Yes, Genr’l . . . My God, they’re going to take the battery!”

Major General John Brown Gordon,

CSA (1832-1904). One of the war's

greatest field commanders, he

survived five wounds at Antietam.

(Courtesy: National Archives and

Records Administration)

Early looked up. Even without the glasses, he could see that the Yankee gun crew had fled. The supporting infantry began to waver, their volleys degenerating to random pops as McCausland’s men broke out of the cornfield, closing the last fifty yards. The bluecoats retreated. The gray troopers swarmed over the rise, a few stopping to turn the gun on the enemy.

“Bully for them!” cried one officer.

Pendleton shook his head. “They can’t hold it. Without support, they’ll be driven back.”

Even as the adjutant said this, a solid line of blue materialized along a ridge farther on. The retreating Yankees halted, rallying as the new line swept down from the ridge. Before the counterattack, the Confederates finally stalled, spitting fire as they lurched back toward the captured gun. The gun’s would-be crew gave up trying to fire it and rejoined the fight.

“McCausland will get his support,” Early declared. He finished writing his dispatch and handed it to a lieutenant. “To Gordon—fast. And ask Breckinridge to join us, if he’s ready.”

The lieutenant galloped down the road.

Early jotted a second note, this one ordering up a couple of General Long’s batteries. A second junior staffer took it and rode off. Now there was little to do but wait and watch. Dismounting, Early unbuttoned his tunic, and most of the others followed suit. Pendleton stayed mounted, gazing across the river as McCausland’s men fought on, disputing every blade of grass. With its flanks threatened and men dropping, the battalion fell back to the rise in fair order.

In this painting by Keith Rocco, Ricketts' troops try to stop Gordon's advance at the

Battle of Monocacy. (Courtesy: National Park Service)

Down by the creek, dust stirred as Gordon’s division lumbered forth, leaving gear strewn and tents unstruck. Within minutes, platoons and whole companies were splashing across the ford, rifles held aloft, men wading waist-deep to the east bank and pawing their way up.

“Gordon always gets ‘em moving,” said Pendleton.

Early gave his adjutant a glance. On the noble, long-chinned face, a smile had surfaced—an admiring smile for Gordon. Everyone seemed to admire the fierce son of Georgia. Raising the glasses, Early grunted—"That’s only what’s expected of him.” Down by the ford, the red-shirted Gordon was easy to spot atop his black charger, urging his men across. He did look fine.

Tending the horses on the west bank, McCausland’s remaining men could only watch while, on the east side, their hard-pressed comrades fought to buffer Gordon’s movement. Nevertheless the infantry too drew fire as it fanned out and deployed in echelon. By the railroad, one of Long’s Napoleons unlimbered and commenced shelling, while another was rolled with some difficulty across the ford.

Swift and efficient though the crossing had been, time slowed as Gordon’s still-forming division began sidling to the right. The sun grew hotter. Early paced, stroking his beard and chewing his tobacco. Looking at his pocket watch—one o’clock already—he wondered how things were progressing back in Frederick. There, under the eyes of a Confederate officers’ delegation, town fathers were scrambling to raise two hundred-thousand dollars from the citizenry. Early hoped the effort would succeed. Torching the town would cause more delay, given that so many of its homes were of brick. And a wagon full of Yankee gold would please Richmond.

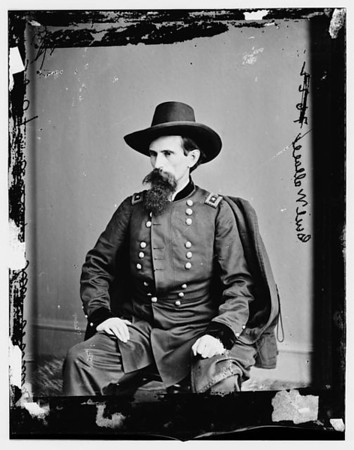

Brigadier General James Ricketts, USA

(1817-1887), whose two brigades bore

the brunt of the Confederate attack at

Monocacy. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

At the rail junction upriver, the cannonade and rifle clash had intensified. Scanning that way, Pendleton rose in his stirrups. “Genr’l, they’ve fired the bridge. The blockhouse too.”

Early seized the glasses and observed twin columns of black smoke rolling skyward, flames leaping from the blockhouse and the covered bridge. Under steady fire, Ramseur’s men moved in. The federal center had withdrawn across the Monocacy, though it still held the iron railroad bridge. “Fine,” said Early. “Billy Yank is good and nervous.”

He swung his gaze back to Gordon’s division, still maneuvering slowly to the south, its extreme right having vanished beyond some woods. The Union line had moved forward in that sector, thinning as it strained to meet the threat. Mounted officers cantered back and forth, gesticulating. Sweeping the higher ground, Early realized the full difficulty of the command he had given. A network of wooden rail fences traversed the sloping fields; studding the fields were stacks of harvested grain, like orderly brown hillocks. When the Yankees inevitably pulled back, these would obstruct attack while supplying good defensive cover.

The two couriers returned, soon followed by Breckinridge and his staff. The Kentuckian announced that his other divisional chief, John Echols, was preparing to lend any needed support. He had no sooner said this when an eruption of shell and musketry heralded Gordon’s assault. Mounting for a better view, Early saw a thin curtain of skirmishers appear from the trees. Massed infantry followed—so dense, for an instant, that it looked like a surge of gray lava. Fire flashed from the Union line. The oncoming brigades slowed but did not pause, pouring out and expanding in a great wave—rifles bristling, blades gleaming, flags like ship-masts in the smoke. The roar of guns stoked the general thunder, a pummeling monotony that devoured the minutes.

Two hours later, with the entire Union left collapsing, Early rode with Breckinridge and the others toward the rail junction. They had drawn alongside the tracks when Early dug his spurs in and broke ahead. In the smoke and flash from across the river, he caught jarred glimpses of the enemy in reeling retreat. His back felt nothing. Like a dream of youth, his whole body sang and he heard himself cackle. “Go it!” he yelled. “Go it, Gordon!” The breeze having shifted, black smoke traveled down from the blockhouse and the covered bridge and began to obscure his vision. The din of war enveloped him: the cataract of rifles, the whistle of minie-balls, the yells and screams, the shell shriek and cannon thunder. And through and above it all, floating, that Rebel cry—shrill as falcons, ice to the spine, the sound of one nightmare engulfing another. Tossing his head back, Early crowed.

Major General John Cabell Breckinridge, CSA

(1821-1875). Early's second-in-command on

the drive toward Washington, D.C., he had

served as U.S. congressman, senator and

vice-president. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

He emerged coughing from the smoke. Slowing his horse, he saw federals flying back across the eastward rail line, Confederates scrambling over the last fences in pursuit. Up at the junction, Yankee artillery had gone silent. Early stopped and got out his binoculars. He watched Ramseur’s men pour across the river shallows and the iron bridge, the enemy center crumbling. Early’s staff clustered around him, all nods and smiles. At the head of Ramseur’s skirmish line he spied a familiar tan horse, its rider waving his hat in celebration. Kyd Douglas had evidently joined the final assault, spurning his duties as Frederick’s provost marshal. Three thoughts struck Early at once: he could court-martial Douglas; he would not court-martial him; he would have liked having a son like him—brave, capable, insufficiently solemn.

“Lord above, Gordon’s a wonderment!” someone exclaimed.

Pulled from his reverie, Early cleared his throat and turned to Pendleton. “Head back to Frederick. Find out about the levy. If they’re still stalling, prepare to fire the town.”

“I don’t think they’ll need convincing now,” said Pendleton, heading off.

Soon afterward, Early was riding among Gordon’s sweaty, powder-blackened infantry as they gathered prisoners. Some stopped to jeer Echols’ men as they streamed tardily past. To the north, stuttering rifle fire persisted. Corpses littered the fields and hillsides and dangled from fences, with carrion birds circling above. Along the riverbank, commandeered boats ferried wounded to the Frederick side, where they were loaded into ambulance wagons.

(Below: a trailer link for the 2006 docu-drama "No Retreat From Destiny: The Battle That Rescued Washington," from Lionheart Filmworks.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zWRpT...

Early’s staff had dispersed for the moment. In the middle distance, Gordon sat atop his charger, looking more grim than triumphant. Breckinridge rode up to him, hand extended in congratulation. Closer by, Early recognized one of Gordon’s aides, a gangly major who was supervising the collection of dead. At Early’s approach, the major gave a dazed salute.

“What can you tell me about your losses?” Early demanded.

The major looked side to side. “I’d reckon about a third of the division, sir.”

Early gazed down the row of outstretched bodies, some already bloating in the heat—limbs stiff and clothes disheveled, some with eyes wide to the afternoon sun, mouths open as if they had died in conversation. Even the bearded ones looked no older than twenty.

“Make sure to collect weapons and cartridges,” said Early. “Shoes, too.”

Squinting up, the major seemed to sway a bit. “Yessir, Genr’l.”

Early watched a cartload of captured flags and rifles roll by. Hanging over the side, a white-and-blue guidon caught his eye. “Hold up there!” he called. The teamster yanked the reins. Leaning down from his horse, Early grabbed the little flag by its swallowtail and examined it. It displayed the Greek Cross. Waving the teamster on, he watched a line of guarded prisoners stumble by, some of them daring an upward glance at their conqueror. He eyed the badges on their caps—again, the Greek Cross. A set of hoofbeats distracted him, and he turned to see Breckinridge cantering up.

(Below: a link for a video on the Battles of Monocacy and Fort Stevens, with historian Marc Leepson.)https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OFQVp...

“Where’s Gordon?” Early asked.

“Gone back to town,” said Breckinridge. “To personally check on medical supplies. His brother’s badly wounded and so’s his senior brigadier.”

“I see.” Early pointed to the prisoners filing past. “Look at those insignias.”

Breckinridge looked, narrowing his eyes. “The Sixth Corps!”

“Part of it, anyhow,” said Early. “Last seen at Petersburg.”

The Kentuckian smiled. “Then Grant’s pulling troops from the main front.”

Yes, Early thought—and that was good for Lee. Yet it conflicted with what had become Early’s most fearsome hope, his blazing vision of what lay ahead. “If Grant sees the full threat we pose, he’ll be sending the rest of the Sixth. More, possibly. I’d wager they’ll be in Washington mighty soon, if not already. And we can’t afford a bloody repulse.”

Breckinridge mulled it over. “Once we’re there, we can determine enemy strength. If it’s too much, we can withdraw—but we won’t know till then. We’ve just over thirty miles left to go. This fight cost us a day’s march, but the race may still be won.”

However quiet and cryptic Breckinridge had been on the subject of Washington, he seemed game about it now. Boldness was catching. “Very good, then,” said Early, heartened. “And lest we forget, a hidden advantage awaits us.” In his side-vision, soldiers dragged more battered corpses into line. He turned his gaze to the pike, following it till it vanished in the low distant hills. “At dawn, your troops will lead the column out. Drive them hard, Breck. By tomorrow night, we need to be on Washington’s doorstep.”

Monument to the Battle of Monocacy, dedicated

on its 1964 centennial. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

“Then we shall be,” said Breckinridge.

They spent a minute discussing Bradley Johnson’s expedition. Johnson’s eight hundred horsemen had left at sunup, aiming for the Baltimore vicinity and thence down the cape to Point Lookout, where thousands of Southern captives needed liberating. On their way, the troopers would spread more panic and destruction.

Pendleton arrived at a gallop, announcing that Frederick would not have to burn; its leading citizens had agreed to scrounge up the two hundred-thousand in bank loans. Apart from that, the town’s supply depot abounded with clothes, blankets, foodstuffs, medicine and horse livery. Best of all, someone’s cellar had yielded a cache of that rarest delicacy, ice cream, packed in ice and woodchips. “If we head back now, we can get ourselves a heap of it!” cried Pendleton.

Breckinridge chuckled. “A good day for the South, all-round.”

Early grunted agreement. Riding off, he cast another glance toward Washington. The way was open. Everything now depended upon speed—speed and, quite possibly, a single Yankee traitor.

The Indiana-born Wallace led a busy and distinguished life. From small-town lawyer and Republican operative, he rose to major general in the Civil War—the Union's youngest, at the time—after which he served as governor of New Mexico Territory and then as U.S. minister to the Ottoman Empire. A writer of historical fiction, he gained lasting fame with the 1880 publication of Ben Hur, which surpassed even Uncle Tom's Cabin in sales and became the best-selling American novel of the 19th Century.

Major General Lew Wallace, USA (1827-1905). (Courtesy:

Library Of Congress)

His role in the war was more checkered, however. After Ulysses S. Grant's close call at the Battle of Shiloh, he charged Wallace with tardiness in moving his reserves forward. (Many years later, writing his memoirs and near death from cancer, Grant would be presented with new evidence from the battle and publicly retract his complaint.) Over the next two years, Wallace found himself exiled to a series of quiet sectors far behind the front lines. Though restored to active duty in March 1864, he was again given a relatively sedate appointment, commanding the VIII Corps at Baltimore. But it was in this capacity that he performed his greatest service to the nation, when Early's invasion of Maryland yanked him out of the doldrums.

Wallace never lacked for initiative. Not waiting for orders from the unaccountably listless War Department, he sped to meet Early's 14,000 rebels at the riverside rail hub of Monocacy Junction. With most of his corps sent to the epic bloodbath in eastern Virginia, he commanded a force less than 6,000 strong, comprised of green "hundred-day" volunteers but also—crucially—two brigades from the battle-hardened VI Corps, under Brigadier General James Ricketts. (Grant had sent them, spurred by the news of Harper's Ferry and Martinsburg being captured.) There was also a small Illinois cavalry detachment under Lieutenant Colonel David Clendenin.

In this gaping hour, these were the only defenders between Early and Washington City. Wallace apprised Army Chief of Staff General Henry Halleck of Early's apparent intentions, and Halleck wired Grant to rush reinforcements to the weakly garrisoned capital. For these to arrive in time, Wallace and his men would have to put up the fight of their lives—which they did on that hot Saturday, for nine blistering hours. Ricketts' left wing bore most of the fighting and eventually collapsed beneath the Confederate onslaught. In the Union center and on the right, having fiercely defended two vital bridgeheads, less experienced units at last had to race back across the river as the attackers bore down. In nearby Frederick, meanwhile, Early secured a $200,000 "levy"—a ransom from civic leaders, against the town being torched.

Lieutenant General Jubal Early, CSA (1816-1894).

(Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Wallace's troops began a limping retreat toward Baltimore, leaving hundreds of dead across the rolling farmland. But they had cost Early a full day's march. On July 11, Early's straggling, sun-beaten raiders reached the capital's fortified perimeter and started probing it. He did not launch his main assault until the next day, at Fort Stevens—and ran up against the rest of Major General Horatio Wright's VI Corps, which had in fact arrived just in time. Early withdrew his force the day after, headed back to the Shenandoah Valley. Union elements pursued but did not catch him.

Margaret Leech wrote in her classic Reveille In Washington, "It was only in contemplation of what might have been that Wallace's stand on the Monocacy assumed the proportions of a deliverance . . . Washington shuddered at a narrow escape." Upon hearing of Wallace's defeat, Grant replaced him as corps commander but soon reinstated him, when his role in saving the capital became clear. In his memoirs, Grant would write, "If Early had been but one day earlier, he might have entered the capital before the arrival of the reinforcements I had sent . . . General Wallace contributed on this occasion by the defeat of the troops under him, a greater benefit to the cause than often falls to the lot of a commander of an equal force to render by means of a victory."

Lucifer's Drum depicts Lew Wallace as a friendly acquaintance of my central character, federal agent Nathaniel Truly, with whom he shares a passion for literature. But it depicts the Monocacy battle from the perspective of Jubal Early. Here it is:

MONOCACY RIVER, MARYLAND, JULY 9

From the town of Frederick, Early’s party rode southeastward along the Washington Pike. Ahead of them, the artillery duel grew louder, resounding over the lush summer farmland. One river bend and then another appeared, intermittently brilliant beneath the high sun, while drifting white smoke marked the battle front. Early turned off the macadam surface, entered a pasture and slowed to a halt, digging for his field glasses. The others reined up around him.

“That’s a mighty strong position,” Sandie Pendleton observed.

At first, Early did not entirely grasp it as he peered at the enemy center. Ramseur’s men had swept through Frederick a few hours ago and were now pushing across wheatfields along the railroad spur. Before them, offering desultory fire, Yankee skirmishers fell back toward the sluggish Monocacy. On the river’s near bank, a tight bluecoat formation guarded a railroad bridge where the spur and the main B & O line merged, continuing eastward. A stone’s throw to the right, a similar formation shielded a covered bridge that served the pike. A fortified blockhouse stood between the bridges, anchoring the whole position like a spike-head while, on the far bank, other Yankee elements waited to frustrate any crossing.

From the north, a clatter of small arms told him that Rodes had deployed, pressing the enemy right wing astride the Baltimore Pike. But the main assault would have to be against the left, to secure the route to Washington. Scanning that way, Early saw that the Union commander had anticipated well, placing the bulk of his infantry along hilly ground east of the river.

Early handed Pendleton the glasses. “Your eyes are younger. Tell me if you see any sign of reserves back there.”

The adjutant gazed for half a minute. “None, Genr’l. Not in large numbers. I’d estimate their total strength at seven, maybe eight thousand.”

“That sounds right to me.” Taking the glasses back, Early gestured south. “If we can get a division or more across, then extend our right and mount a strong attack, they’ll have to change fronts in order to face it. At which point we can exploit any confusion and roll ‘em up.”

Two other staff officers had dismounted and gotten out the map, each holding a side of it. One traced the Monocacy with his finger. “Don’t see any fords or bridges that way, sir. None that’s close enough, according to this.”

Lieutenant Colonel Alexander "Sandie"

Pendleton, CSA, (1840-1864), aide to

Early, said to have been the finest staff

officer on either side. (Courtesy: Library

of Congress)

“There must be one, damn it! We need scouts. Anyone know if McCausland’s back yet?”

“Barring any real troubles, he ought to be,” said Pendleton.

Early scowled. Too often, with McCausland, “ought to be” fell shy of “is.” The cavalryman’s assignment had been simple enough: cut telegraph wires, rip up more of the B & O and then return as fast as possible. “We’ll have to do our own scouting, then. Let’s get at it.”

The party rode on, turning down a divergent road. The road and tracks ran parallel to the river until, separately, they bridged a curling creek. On the creek’s near side, Breckinridge’s corps lay in wait. Early signaled a halt. From a grassy rise across the river, a Yankee battery let loose and frightened the horses. Early nearly dropped the glasses as he steadied his mount, wondering if they were out of range.

“Genr’l–look yonder!” Pendleton pointed.

From the west, along the creek’s far side, Early saw a cloud of dust and then flapping guidons, followed by a large body of horsemen: McCausland’s battalion. They crossed the road and then the tracks, headed straight for the Monocacy. Through the glasses, Early watched as three lead riders—tawny men in buckskin, probably Cherokee—reached the creek’s point of confluence and dismounted, then waded into the mud-brown river. The water came up only to their waists. Holding their carbines high, two of the scouts kept on while the remaining one motioned for the rest to follow. Rider after rider dismounted, plunged in and started wading toward the opposite bank.

Brigadier General "Tiger" John McCausland, CSA (1836-1927).

An object of Early's repeated scorn, he performed magnificently

at Monocacy. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

“God-a-mighty!” cried Early. “He’s gone and done something right!” Checking the Yankee gun, he saw its crew manhandling it to a new position while some infantry moved up, lying on their stomachs or crouching. Again Early peered downriver. McCausland was holding back about a third of his brigade to tend the riderless horses. The rest of his men continued to pour across, vanishing into foliage along the Monocacy’s east bank. Not far beyond it, they began to reappear in a gently sloping cornfield. With sabers, carbines and pistols drawn, the wet troopers were forming a battle line. Near their right, an enemy shell sent up a spout of earth.

“Foot charge,” Early muttered.

Another shell struck in front of McCausland’s line, but with no sign of faltering it started through the corn. Onward it pushed, quick and then double-quick, headed for the battery atop the grassy rise. An enemy fusillade crackled. Several gray-clad bodies fell but the rest surged on, their order commendable as a shell sailed over their heads and exploded uselessly. Thinking of McCausland, Early granted himself some credit. Since Lynchburg he had made his disapproval of the cavalry chief well known, thereby holding him to a stern standard. Surely it had helped drive McCausland to this startling deed of valor, rash though it was. And at least a suitable ford had been located. Early passed the glasses to Pendleton. From his saddlebag he took a pencil, a book and a piece of writing paper. The book was a signed gift from Jackson, a collection of religious essays which Early had never even glanced at; its cover provided a writing surface.

“Pendleton—Gordon’s division is closest down there, correct?”

“Yes, Genr’l . . . My God, they’re going to take the battery!”

Major General John Brown Gordon,

CSA (1832-1904). One of the war's

greatest field commanders, he

survived five wounds at Antietam.

(Courtesy: National Archives and

Records Administration)

Early looked up. Even without the glasses, he could see that the Yankee gun crew had fled. The supporting infantry began to waver, their volleys degenerating to random pops as McCausland’s men broke out of the cornfield, closing the last fifty yards. The bluecoats retreated. The gray troopers swarmed over the rise, a few stopping to turn the gun on the enemy.

“Bully for them!” cried one officer.

Pendleton shook his head. “They can’t hold it. Without support, they’ll be driven back.”

Even as the adjutant said this, a solid line of blue materialized along a ridge farther on. The retreating Yankees halted, rallying as the new line swept down from the ridge. Before the counterattack, the Confederates finally stalled, spitting fire as they lurched back toward the captured gun. The gun’s would-be crew gave up trying to fire it and rejoined the fight.

“McCausland will get his support,” Early declared. He finished writing his dispatch and handed it to a lieutenant. “To Gordon—fast. And ask Breckinridge to join us, if he’s ready.”

The lieutenant galloped down the road.

Early jotted a second note, this one ordering up a couple of General Long’s batteries. A second junior staffer took it and rode off. Now there was little to do but wait and watch. Dismounting, Early unbuttoned his tunic, and most of the others followed suit. Pendleton stayed mounted, gazing across the river as McCausland’s men fought on, disputing every blade of grass. With its flanks threatened and men dropping, the battalion fell back to the rise in fair order.

In this painting by Keith Rocco, Ricketts' troops try to stop Gordon's advance at the

Battle of Monocacy. (Courtesy: National Park Service)

Down by the creek, dust stirred as Gordon’s division lumbered forth, leaving gear strewn and tents unstruck. Within minutes, platoons and whole companies were splashing across the ford, rifles held aloft, men wading waist-deep to the east bank and pawing their way up.

“Gordon always gets ‘em moving,” said Pendleton.

Early gave his adjutant a glance. On the noble, long-chinned face, a smile had surfaced—an admiring smile for Gordon. Everyone seemed to admire the fierce son of Georgia. Raising the glasses, Early grunted—"That’s only what’s expected of him.” Down by the ford, the red-shirted Gordon was easy to spot atop his black charger, urging his men across. He did look fine.

Tending the horses on the west bank, McCausland’s remaining men could only watch while, on the east side, their hard-pressed comrades fought to buffer Gordon’s movement. Nevertheless the infantry too drew fire as it fanned out and deployed in echelon. By the railroad, one of Long’s Napoleons unlimbered and commenced shelling, while another was rolled with some difficulty across the ford.

Swift and efficient though the crossing had been, time slowed as Gordon’s still-forming division began sidling to the right. The sun grew hotter. Early paced, stroking his beard and chewing his tobacco. Looking at his pocket watch—one o’clock already—he wondered how things were progressing back in Frederick. There, under the eyes of a Confederate officers’ delegation, town fathers were scrambling to raise two hundred-thousand dollars from the citizenry. Early hoped the effort would succeed. Torching the town would cause more delay, given that so many of its homes were of brick. And a wagon full of Yankee gold would please Richmond.

Brigadier General James Ricketts, USA

(1817-1887), whose two brigades bore

the brunt of the Confederate attack at

Monocacy. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

At the rail junction upriver, the cannonade and rifle clash had intensified. Scanning that way, Pendleton rose in his stirrups. “Genr’l, they’ve fired the bridge. The blockhouse too.”

Early seized the glasses and observed twin columns of black smoke rolling skyward, flames leaping from the blockhouse and the covered bridge. Under steady fire, Ramseur’s men moved in. The federal center had withdrawn across the Monocacy, though it still held the iron railroad bridge. “Fine,” said Early. “Billy Yank is good and nervous.”

He swung his gaze back to Gordon’s division, still maneuvering slowly to the south, its extreme right having vanished beyond some woods. The Union line had moved forward in that sector, thinning as it strained to meet the threat. Mounted officers cantered back and forth, gesticulating. Sweeping the higher ground, Early realized the full difficulty of the command he had given. A network of wooden rail fences traversed the sloping fields; studding the fields were stacks of harvested grain, like orderly brown hillocks. When the Yankees inevitably pulled back, these would obstruct attack while supplying good defensive cover.

The two couriers returned, soon followed by Breckinridge and his staff. The Kentuckian announced that his other divisional chief, John Echols, was preparing to lend any needed support. He had no sooner said this when an eruption of shell and musketry heralded Gordon’s assault. Mounting for a better view, Early saw a thin curtain of skirmishers appear from the trees. Massed infantry followed—so dense, for an instant, that it looked like a surge of gray lava. Fire flashed from the Union line. The oncoming brigades slowed but did not pause, pouring out and expanding in a great wave—rifles bristling, blades gleaming, flags like ship-masts in the smoke. The roar of guns stoked the general thunder, a pummeling monotony that devoured the minutes.

Two hours later, with the entire Union left collapsing, Early rode with Breckinridge and the others toward the rail junction. They had drawn alongside the tracks when Early dug his spurs in and broke ahead. In the smoke and flash from across the river, he caught jarred glimpses of the enemy in reeling retreat. His back felt nothing. Like a dream of youth, his whole body sang and he heard himself cackle. “Go it!” he yelled. “Go it, Gordon!” The breeze having shifted, black smoke traveled down from the blockhouse and the covered bridge and began to obscure his vision. The din of war enveloped him: the cataract of rifles, the whistle of minie-balls, the yells and screams, the shell shriek and cannon thunder. And through and above it all, floating, that Rebel cry—shrill as falcons, ice to the spine, the sound of one nightmare engulfing another. Tossing his head back, Early crowed.

Major General John Cabell Breckinridge, CSA

(1821-1875). Early's second-in-command on

the drive toward Washington, D.C., he had

served as U.S. congressman, senator and

vice-president. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

He emerged coughing from the smoke. Slowing his horse, he saw federals flying back across the eastward rail line, Confederates scrambling over the last fences in pursuit. Up at the junction, Yankee artillery had gone silent. Early stopped and got out his binoculars. He watched Ramseur’s men pour across the river shallows and the iron bridge, the enemy center crumbling. Early’s staff clustered around him, all nods and smiles. At the head of Ramseur’s skirmish line he spied a familiar tan horse, its rider waving his hat in celebration. Kyd Douglas had evidently joined the final assault, spurning his duties as Frederick’s provost marshal. Three thoughts struck Early at once: he could court-martial Douglas; he would not court-martial him; he would have liked having a son like him—brave, capable, insufficiently solemn.

“Lord above, Gordon’s a wonderment!” someone exclaimed.

Pulled from his reverie, Early cleared his throat and turned to Pendleton. “Head back to Frederick. Find out about the levy. If they’re still stalling, prepare to fire the town.”

“I don’t think they’ll need convincing now,” said Pendleton, heading off.

Soon afterward, Early was riding among Gordon’s sweaty, powder-blackened infantry as they gathered prisoners. Some stopped to jeer Echols’ men as they streamed tardily past. To the north, stuttering rifle fire persisted. Corpses littered the fields and hillsides and dangled from fences, with carrion birds circling above. Along the riverbank, commandeered boats ferried wounded to the Frederick side, where they were loaded into ambulance wagons.

(Below: a trailer link for the 2006 docu-drama "No Retreat From Destiny: The Battle That Rescued Washington," from Lionheart Filmworks.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zWRpT...

Early’s staff had dispersed for the moment. In the middle distance, Gordon sat atop his charger, looking more grim than triumphant. Breckinridge rode up to him, hand extended in congratulation. Closer by, Early recognized one of Gordon’s aides, a gangly major who was supervising the collection of dead. At Early’s approach, the major gave a dazed salute.

“What can you tell me about your losses?” Early demanded.

The major looked side to side. “I’d reckon about a third of the division, sir.”

Early gazed down the row of outstretched bodies, some already bloating in the heat—limbs stiff and clothes disheveled, some with eyes wide to the afternoon sun, mouths open as if they had died in conversation. Even the bearded ones looked no older than twenty.

“Make sure to collect weapons and cartridges,” said Early. “Shoes, too.”

Squinting up, the major seemed to sway a bit. “Yessir, Genr’l.”

Early watched a cartload of captured flags and rifles roll by. Hanging over the side, a white-and-blue guidon caught his eye. “Hold up there!” he called. The teamster yanked the reins. Leaning down from his horse, Early grabbed the little flag by its swallowtail and examined it. It displayed the Greek Cross. Waving the teamster on, he watched a line of guarded prisoners stumble by, some of them daring an upward glance at their conqueror. He eyed the badges on their caps—again, the Greek Cross. A set of hoofbeats distracted him, and he turned to see Breckinridge cantering up.

(Below: a link for a video on the Battles of Monocacy and Fort Stevens, with historian Marc Leepson.)https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OFQVp...

“Where’s Gordon?” Early asked.

“Gone back to town,” said Breckinridge. “To personally check on medical supplies. His brother’s badly wounded and so’s his senior brigadier.”

“I see.” Early pointed to the prisoners filing past. “Look at those insignias.”

Breckinridge looked, narrowing his eyes. “The Sixth Corps!”

“Part of it, anyhow,” said Early. “Last seen at Petersburg.”

The Kentuckian smiled. “Then Grant’s pulling troops from the main front.”

Yes, Early thought—and that was good for Lee. Yet it conflicted with what had become Early’s most fearsome hope, his blazing vision of what lay ahead. “If Grant sees the full threat we pose, he’ll be sending the rest of the Sixth. More, possibly. I’d wager they’ll be in Washington mighty soon, if not already. And we can’t afford a bloody repulse.”

Breckinridge mulled it over. “Once we’re there, we can determine enemy strength. If it’s too much, we can withdraw—but we won’t know till then. We’ve just over thirty miles left to go. This fight cost us a day’s march, but the race may still be won.”

However quiet and cryptic Breckinridge had been on the subject of Washington, he seemed game about it now. Boldness was catching. “Very good, then,” said Early, heartened. “And lest we forget, a hidden advantage awaits us.” In his side-vision, soldiers dragged more battered corpses into line. He turned his gaze to the pike, following it till it vanished in the low distant hills. “At dawn, your troops will lead the column out. Drive them hard, Breck. By tomorrow night, we need to be on Washington’s doorstep.”

Monument to the Battle of Monocacy, dedicated

on its 1964 centennial. (Courtesy: Library of Congress)

“Then we shall be,” said Breckinridge.

They spent a minute discussing Bradley Johnson’s expedition. Johnson’s eight hundred horsemen had left at sunup, aiming for the Baltimore vicinity and thence down the cape to Point Lookout, where thousands of Southern captives needed liberating. On their way, the troopers would spread more panic and destruction.

Pendleton arrived at a gallop, announcing that Frederick would not have to burn; its leading citizens had agreed to scrounge up the two hundred-thousand in bank loans. Apart from that, the town’s supply depot abounded with clothes, blankets, foodstuffs, medicine and horse livery. Best of all, someone’s cellar had yielded a cache of that rarest delicacy, ice cream, packed in ice and woodchips. “If we head back now, we can get ourselves a heap of it!” cried Pendleton.

Breckinridge chuckled. “A good day for the South, all-round.”

Early grunted agreement. Riding off, he cast another glance toward Washington. The way was open. Everything now depended upon speed—speed and, quite possibly, a single Yankee traitor.

Published on July 09, 2017 00:02

•

Tags:

battle-of-monocacy, bernie-mackinnon, frederick-md, james-ricketts, jubal-early, lew-wallace, lucifer-s-drum