Bernie MacKinnon's Blog - Posts Tagged "fall-of-richmond"

My Lost Prologue

When a novel is already fat, its author would do well *not* to include a prologue, those leisurely opening pages that give readers a bird's-eye view of time and place. Some works of fiction benefit from a prologue—a short one, preferably—but most do fine without one. I confess that when I open a book and see one, my heart sinks a little, since it means a delay of action. Still, my novel Lucifer's Drum once had a prologue. The story did seem to call for it at the time—a panoramic update, a hold-onto-your-hat overture as the Civil War lurched into its last and most horrific year.

But as I wrestled with a big story that threatened to become too big, those pages proved highly expendable. I put a lot into them, though, and am therefore posting them today, the 150th anniversary of Richmond's capture. The Confederate capital's fall was the culmination of events that started eleven months earlier, when Grant and Lee began their death struggle and the blood tide crested. All of which I tried to evoke here:

PROLOGUE: SPRING, 1864

Deep into the war, survivors found themselves looking back to the beginning. Each had a sudden, private urge to reclaim that moment, now so distant, before it too was lost. Few spoke of it, so memories groped in silence. And the more they remembered, the stranger they felt, realizing that madness and innocence are sometimes impossible to tell apart.

It had begun in fever and delirium, in shrill song and deafening cheer. With an eruption of bands and banners, with ornate cavalry and shiny black cannon rattling down the avenues. With brave, endless volunteer columns trying to look smart and march straight for the weeping girls. And with speeches: On to Richmond, God points the Way, Victory before Christmas, let him whose heart is faint turn back. A Union forever. Now, with the roar of Gettysburg not a year past, a generation of ghosts thronged the woods, hills and fields from Pennsylvania to the Trans-Mississippi.

People had at first been the manifest agents of conflict, actively willing events toward a vast and inescapable collision. Responding to the scope of the hour, they appeared somehow magnified to themselves and one another, their deeds and assertions grand as never before. Noble resolve covered everything in hues of gold, even the first homeward coffins and the humble tents dotting the hillsides. Minds, bodies, convictions—these, overnight, were galvanized for a single severe purpose, pushing and not driven, sweeping and not swept to the forward lines.

Yet at some otherworldly juncture, as the cemeteries grew and then spilled over, that purpose left the realm of human design—gone into the earth, into the smoky sky, somewhere else. A war launched in righteous certitude, by humans, had become a colossal organism that thundered of its own power. It was a creature undreamed of. Deaf to protest and opinion, it dwarfed the legions and drowned out the bands, banishing the golden light forever. Amid its heaving, unstoppable shocks, men cowered and scrambled. Armies were its beasts of burden, battalions food for its maw, each soldier a windblown seed. People had in fact never looked so small.

Deep inside the din, speeches could still be heard—Abolitionists, Constitutionalists, War Democrats, centrist Republicans and Copperheads were no less strident. But invocations of the Deity were more frequent, as if the speakers knew instinctively that mortal arguments alone would rally no one, would sound shriveled and obscene to ears grown hard. Street conversations were more clipped, more distracted, and one might note a cast of shadow in another's eye. Yesterday's expressions and sentiments remained like stumps in a hurricane and people clung to them, grasping at the same time for new certitudes. They tried to predict. They tried to envision the end. But in the fury of this storm, no eye could penetrate. And at solitary moments, all but the most flinty and partisan of souls wondered what it was they had done, what had been done, what they would do now. In the Executive Mansion, a gaunt President wondered this continually.

The opposing forces had hibernated through the winter. Greatcoated sentries leaned on their rifles and gazed across the river. For its part, the population marked time and kept busy. Women rolled bandages when they weren't cooking or mending. Children played, did chores or school work and said their prayers. But at night, clocks struck louder upon the ear. Lying awake in barracks, or in feather beds, people listened to the wind moan prophecies they could not decipher.

By daylight, many spoken prophecies centered on Ulysses S. Grant. The general's air of scruffy competence heartened Northerners, who had seen their boast trampled on too many fields. Betrayed by their own optimism, gorged sick on debate and mistrustful of appearances, they welcomed a man who was plain in speech, manner and appearance but a virtuoso in warfare. Grant came east with his record of western victories and did not boast. He went to work planning his spring campaign and assembling one of the largest forces in world history. In early May, chewing his cigar, he watched his great army cross the Rapidan into the Wilderness, into the scrub oak and blooming dogwood. Into Confederate hellfire. On the second night, with flames racing through dry undergrowth, the woods torn by the screams of wounded unable to crawl fast enough, Grant excused himself from his staff, entered his tent and wept.

What followed was armed combat as the world had never seen it. Grant did not withdraw but sent his blue leviathan hulking southeastward. Robert E. Lee's gray one followed, and the antagonists remained in daily, bludgeoning contact as the month wore on. Along with the dead and wounded, men returned wide-eyed and gibbering from the front, struck with a madness yet unnamed. Crows and wild pigs fed upon the dead before they could be carted off, and as accounts of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor bled into newsprint, the casualty rosters unfurled. Memorial portraits decorated parlors draped in black. Embalmers put up their signs. Diarists sat with nibs poised above blank pages. In school and church, children's attention strayed as they tried to picture that paradise to which their martyred fathers had gone.

June's arrival found towns and cities in a growing state of shock. Draftees fled or scraped up the $300 substitute fee. "Bounty-jumpers" prospered by enlisting for cash bonuses, deserting, then repeating the process. Urging calm, local pro-Union leaders gave pallid homilies about honoring the dead through renewed commitment.

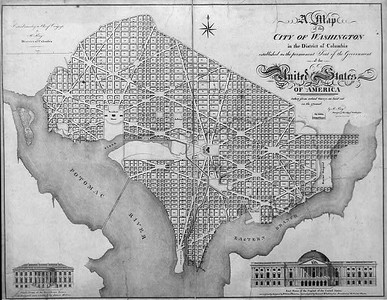

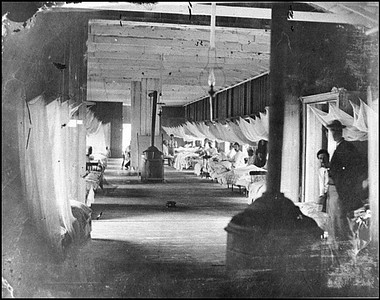

Washington, D.C., had more experience than most in the practice of calm. While the rest of the North sank from frenzied hope to bitter dismay, Washington sought to emulate its own statues and not flinch. It took reassurance from its grand, unfinished government buildings and its unrivaled ring of forts. It kept about its business despite daily boatloads of wounded at the Sixth Street wharf. Wounded languished in hospitals, converted churches and private homes; in hotels, warehouses and fraternal lodges. But the summer heat swelled, dulling alarm and bringing out something of the city's languid Southern character. Much less of that character survived these days. For Washington, the firing on Fort Sumter had signaled not just war, not just the swarming encampments, but also an influx of merchants and poor folk. War meant business for shops, markets, taverns, theaters, hotels, brothels and livery stables, and these had multiplied while troops paraded and battles quaked upriver or to the south. Confederate spies moved within the burgeoning population, drawing support from the city's strong pro-Southern element, passing information despite the War Department's draconian measures. Ridiculously young for its size, ridiculously divided and unready for its role as the Union's martial crux, Washington strained to meet the challenge of its transfiguration. But while it aped the smugness of older, greater cities, foreign diplomats eyed its imperial pillars and snickered. Away from the fashionable districts, shanties huddled along brawling, mud-holed streets where police chased thieves and battled ruffian gangs.

Still, as the murderous tumult continued elsewhere, the capital's summer heat slowed everything. It conjured flies from the fetid marsh and aqueduct and from the government slaughter pens. To many, a worse stench emanated from the Capitol Building, where Copperhead congressmen declared Grant a mass murderer and cried for peace while Republicans cried for censure. All looked forward to the summer recess, though it would not be much of one. A presidential election loomed with the promise of more dirt, more acrimony than the campaigns of 1860, and the parties had to marshal their forces. It was widely expected that the Lincoln administration would fall. Of the last eight Presidents, none had seen a second term, claimed either by death or factional strife.

Increasingly, dark-skinned refugees turned up—bedgraggled men, women and children liberated in Grant's wake and drawn by the capital's safety. "Contrabands," the authorities called them, ranking them with captured livestock and cotton bales. Up from the Virginia fields they came, stunned and hopeful, to scrounge some kind of living, to gaze at the monuments and at the white citizenry who glanced and kept walking. Some were taken in by the Freedman's Aid Society or the quietly industrious community of free blacks. Others slept on the street or in woodlots, or settled in shack towns along the city's northern fringe. Many of the men soon left to join their lettered, Northern-raised brethren in Negro regiments. To any white who cared to ask or listen, the ex-slaves would evince no doubt of the war's mystical dimension. They might show a ragged scar or two, indicating time spent under the devil's will and a sure preference for God's, however terrible.

But everyone knew that the story was being blasted and re-written even as they breathed. The imponderable creature roared louder than ever, taking all in its reach. On clear days near the capital's outskirts, one could catch the far-off rumble of shelling. And certain people sensed that motives had sunk beneath the level of language, beneath the phrases about God, Honor, Freedom and Country, to the darkest region of the heart.

(Photos Courtesy: Library of Congress)

But as I wrestled with a big story that threatened to become too big, those pages proved highly expendable. I put a lot into them, though, and am therefore posting them today, the 150th anniversary of Richmond's capture. The Confederate capital's fall was the culmination of events that started eleven months earlier, when Grant and Lee began their death struggle and the blood tide crested. All of which I tried to evoke here:

PROLOGUE: SPRING, 1864

Deep into the war, survivors found themselves looking back to the beginning. Each had a sudden, private urge to reclaim that moment, now so distant, before it too was lost. Few spoke of it, so memories groped in silence. And the more they remembered, the stranger they felt, realizing that madness and innocence are sometimes impossible to tell apart.

It had begun in fever and delirium, in shrill song and deafening cheer. With an eruption of bands and banners, with ornate cavalry and shiny black cannon rattling down the avenues. With brave, endless volunteer columns trying to look smart and march straight for the weeping girls. And with speeches: On to Richmond, God points the Way, Victory before Christmas, let him whose heart is faint turn back. A Union forever. Now, with the roar of Gettysburg not a year past, a generation of ghosts thronged the woods, hills and fields from Pennsylvania to the Trans-Mississippi.

People had at first been the manifest agents of conflict, actively willing events toward a vast and inescapable collision. Responding to the scope of the hour, they appeared somehow magnified to themselves and one another, their deeds and assertions grand as never before. Noble resolve covered everything in hues of gold, even the first homeward coffins and the humble tents dotting the hillsides. Minds, bodies, convictions—these, overnight, were galvanized for a single severe purpose, pushing and not driven, sweeping and not swept to the forward lines.

Yet at some otherworldly juncture, as the cemeteries grew and then spilled over, that purpose left the realm of human design—gone into the earth, into the smoky sky, somewhere else. A war launched in righteous certitude, by humans, had become a colossal organism that thundered of its own power. It was a creature undreamed of. Deaf to protest and opinion, it dwarfed the legions and drowned out the bands, banishing the golden light forever. Amid its heaving, unstoppable shocks, men cowered and scrambled. Armies were its beasts of burden, battalions food for its maw, each soldier a windblown seed. People had in fact never looked so small.

Deep inside the din, speeches could still be heard—Abolitionists, Constitutionalists, War Democrats, centrist Republicans and Copperheads were no less strident. But invocations of the Deity were more frequent, as if the speakers knew instinctively that mortal arguments alone would rally no one, would sound shriveled and obscene to ears grown hard. Street conversations were more clipped, more distracted, and one might note a cast of shadow in another's eye. Yesterday's expressions and sentiments remained like stumps in a hurricane and people clung to them, grasping at the same time for new certitudes. They tried to predict. They tried to envision the end. But in the fury of this storm, no eye could penetrate. And at solitary moments, all but the most flinty and partisan of souls wondered what it was they had done, what had been done, what they would do now. In the Executive Mansion, a gaunt President wondered this continually.

The opposing forces had hibernated through the winter. Greatcoated sentries leaned on their rifles and gazed across the river. For its part, the population marked time and kept busy. Women rolled bandages when they weren't cooking or mending. Children played, did chores or school work and said their prayers. But at night, clocks struck louder upon the ear. Lying awake in barracks, or in feather beds, people listened to the wind moan prophecies they could not decipher.

By daylight, many spoken prophecies centered on Ulysses S. Grant. The general's air of scruffy competence heartened Northerners, who had seen their boast trampled on too many fields. Betrayed by their own optimism, gorged sick on debate and mistrustful of appearances, they welcomed a man who was plain in speech, manner and appearance but a virtuoso in warfare. Grant came east with his record of western victories and did not boast. He went to work planning his spring campaign and assembling one of the largest forces in world history. In early May, chewing his cigar, he watched his great army cross the Rapidan into the Wilderness, into the scrub oak and blooming dogwood. Into Confederate hellfire. On the second night, with flames racing through dry undergrowth, the woods torn by the screams of wounded unable to crawl fast enough, Grant excused himself from his staff, entered his tent and wept.

What followed was armed combat as the world had never seen it. Grant did not withdraw but sent his blue leviathan hulking southeastward. Robert E. Lee's gray one followed, and the antagonists remained in daily, bludgeoning contact as the month wore on. Along with the dead and wounded, men returned wide-eyed and gibbering from the front, struck with a madness yet unnamed. Crows and wild pigs fed upon the dead before they could be carted off, and as accounts of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania and Cold Harbor bled into newsprint, the casualty rosters unfurled. Memorial portraits decorated parlors draped in black. Embalmers put up their signs. Diarists sat with nibs poised above blank pages. In school and church, children's attention strayed as they tried to picture that paradise to which their martyred fathers had gone.

June's arrival found towns and cities in a growing state of shock. Draftees fled or scraped up the $300 substitute fee. "Bounty-jumpers" prospered by enlisting for cash bonuses, deserting, then repeating the process. Urging calm, local pro-Union leaders gave pallid homilies about honoring the dead through renewed commitment.

Washington, D.C., had more experience than most in the practice of calm. While the rest of the North sank from frenzied hope to bitter dismay, Washington sought to emulate its own statues and not flinch. It took reassurance from its grand, unfinished government buildings and its unrivaled ring of forts. It kept about its business despite daily boatloads of wounded at the Sixth Street wharf. Wounded languished in hospitals, converted churches and private homes; in hotels, warehouses and fraternal lodges. But the summer heat swelled, dulling alarm and bringing out something of the city's languid Southern character. Much less of that character survived these days. For Washington, the firing on Fort Sumter had signaled not just war, not just the swarming encampments, but also an influx of merchants and poor folk. War meant business for shops, markets, taverns, theaters, hotels, brothels and livery stables, and these had multiplied while troops paraded and battles quaked upriver or to the south. Confederate spies moved within the burgeoning population, drawing support from the city's strong pro-Southern element, passing information despite the War Department's draconian measures. Ridiculously young for its size, ridiculously divided and unready for its role as the Union's martial crux, Washington strained to meet the challenge of its transfiguration. But while it aped the smugness of older, greater cities, foreign diplomats eyed its imperial pillars and snickered. Away from the fashionable districts, shanties huddled along brawling, mud-holed streets where police chased thieves and battled ruffian gangs.

Still, as the murderous tumult continued elsewhere, the capital's summer heat slowed everything. It conjured flies from the fetid marsh and aqueduct and from the government slaughter pens. To many, a worse stench emanated from the Capitol Building, where Copperhead congressmen declared Grant a mass murderer and cried for peace while Republicans cried for censure. All looked forward to the summer recess, though it would not be much of one. A presidential election loomed with the promise of more dirt, more acrimony than the campaigns of 1860, and the parties had to marshal their forces. It was widely expected that the Lincoln administration would fall. Of the last eight Presidents, none had seen a second term, claimed either by death or factional strife.

Increasingly, dark-skinned refugees turned up—bedgraggled men, women and children liberated in Grant's wake and drawn by the capital's safety. "Contrabands," the authorities called them, ranking them with captured livestock and cotton bales. Up from the Virginia fields they came, stunned and hopeful, to scrounge some kind of living, to gaze at the monuments and at the white citizenry who glanced and kept walking. Some were taken in by the Freedman's Aid Society or the quietly industrious community of free blacks. Others slept on the street or in woodlots, or settled in shack towns along the city's northern fringe. Many of the men soon left to join their lettered, Northern-raised brethren in Negro regiments. To any white who cared to ask or listen, the ex-slaves would evince no doubt of the war's mystical dimension. They might show a ragged scar or two, indicating time spent under the devil's will and a sure preference for God's, however terrible.

But everyone knew that the story was being blasted and re-written even as they breathed. The imponderable creature roared louder than ever, taking all in its reach. On clear days near the capital's outskirts, one could catch the far-off rumble of shelling. And certain people sensed that motives had sunk beneath the level of language, beneath the phrases about God, Honor, Freedom and Country, to the darkest region of the heart.

(Photos Courtesy: Library of Congress)

Published on April 03, 2015 21:38

•

Tags:

1864, civil-war, fall-of-richmond, lucifer-s-drum, prologue