Hélio Pires's Blog

February 15, 2021

Of gods, rites, culture and sites

From Norse to Roman

When I left wicca, roughly two decades ago, and stepped into neopagan reconstructionism, my choice fell upon Norse polytheism. And it brought me enriching experiences. But after about a year living in Sweden and having been in daily contact with a culture different from the one I grew up in, I started leaving that initial choice in favour of a convergence between native culture and religion. It was my departure from Norse towards Roman polytheism. Of the former, two things remained: an ongoing academic interest and the worship of Norse deities, initially a considerable number of them, but eventually narrowed down to a more limited group focused around Freyr.

Originally, that worship of northern gods kept the traits with which I had practised it for years and there was a period when my religious practice was, so to speak, bicephalous: part Norse, part Roman. But as the latter cemented itself and the convergence between culture and religion accentuated, I started Romanizing the way I paid tribute to Freyr and others. At first, by creating a separate, Roman-inspired rite, but more recently by simply using the standard Roman rite in full. From the initial Norse adaptation there remains an offering to Freyja at the opening and closing, a toasting section and, rarely, the use of a small hazel wand to consecrate offerings that are later ritually made profane.

That’s where I am at the moment. And it reflects a set of basic principles: 1) the definition of religion not by belief or faith, in the Abrahamic fashion, but by ritual praxis or orthopraxy, which is closer to the pre-Christian model; 2) the same gods can be worshipped in different ways or, to use another formulation of the same idea, the general principle according to which deities are universal and religious traditions ethnic; 3) approaching a revived ancient religion by way of a modern, historically-relevant identity (i.e. linked to the original cultural context of said religion) and thus the integration of the former into the latter; 4) and the resulting modern definition of Roman polytheism as the worship of many gods, Roman and others, according to Roman ritual tradition, in a romance cultural context. Hence why I, a Portuguese cultor deorum, worship Freyr, Freyja, Njord and Ullr using Roman rite, within a Latin culture, employing Portuguese as a ritual language.

More Ibero-romance

The same impulse that led me to switch from Norse to Roman polytheism also originated a new focus on pre-Roman Iberian deities. Which may seem like a contradiction – I go for something and then take a look at an older thing? – but it’s linked to the third of the four principles listed above, that of approaching a revived ancient religion – in this case, Roman – by way of a modern, historically-relevant identity – in my case, Portuguese – integrating the former into the latter. Now, the Portuguese cultural matrix is predominantly Latin (and hence romance), but it is not pure, as virtually no culture is. It also has Celtic, Germanic, Hebrew and Arab layers, no doubt that in different degrees, but they’re there. They’re part of the language, History, customs and land; on that note, the Germanic stratum adds another side to me worshipping Norse deities. Also, the cults of many of the Iberian gods were Latinized during the Roman period, and so, in the convergence between native culture and religion, my practices came to include deities of Celtic origin tied to the territory that is now that of my country, worshipped the Roman way and in a Latin context, just as they were for several centuries in the pre-Christian period.

The first I integrated was the goddess Nabia, followed by Quangeio, the pair Arentio and Arentia and finally Reue. And far from just worshipping Them, I placed Them at the heart of my religion: to Nabia I started making monthly offerings and gave Her a local epithet I later identified with my Family Lar; to Quangeio, which scholars believe to have been a canine god, I equally awarded a day for monthly offerings and associated Him with Mercury, which also plays into the Iberiazation of my cult to the Son of Maia; and Reue, apart from integrating my morning and night prayers (just like Nabia and Quangeio), also began receiving offerings on the Ides of every month. And I’m not setting aside the addition of further Iberian deities to my religious practice. The god Crouga, for instance, is a possibility under consideration.

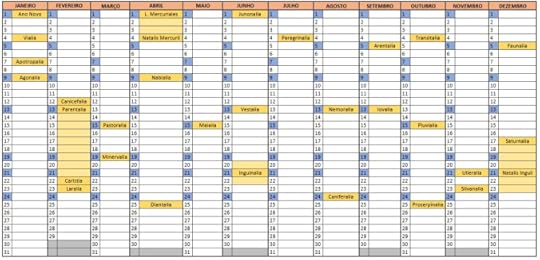

The calendar

Unsurprisingly, the convergence between cultural identity and religion had an impact on my festive calendar, too. Actually, the correct verb tense is more present than past, since that impact wasn’t an isolated moment in time, but an ongoing process that recently contributed to new changes, motivated also by a desire for some simplification.

Thus, I’m removing from my calendar the separate tributes to Freyja and Njord and instead make them a part of my two annual sacrifices to Freyr around the time of the solstices, in accordance with evolution of who I worship among the Norse gods. The only other northern deity that retains a festive day of its own is Ullr, by virtue of being a god of yews, a tree for which I have a particular fascination; enough at least to consider a tattoo and go through the effort of resorting to friends and contacts to acquire two common yews from a tree nursery over 100 kilometres away and add them to a small grove I’m planting. But if Ullr’s annual sacrifice remains, its date changes from December 12th to November 21st, so as to be aligned with Freyr’s and close to Silvanus’, on the 23rd of November, which is also Portugal’s Native Forest Day. In that, too, there’s an element of integration of a cult to a Norse god into a romance cultural context.

Simultaneously, I’m adding a separate festive date to Reue, given His growing presence in my religious life, but in order to accommodate it I had to move the day of Nabia’s sacrifice, which is now on April 9th, also the exact date of a tribute paid to Her in ancient times, according to the inscription on the altar of Marecos. Reue is thus to be honoured individually on March 15th – He’s also already worshipped on October 15th as part of a rain-making triad – and the new festivity will be called Pastoralia, from Latin/Portuguese pastor, in reference to His (modern) role as Shepherd of Clouds. And also stressing the Ibero-romance side of my practices, Arentio and Arentia will receive offerings on the Nones of every month.

Finally, I’m also removing the annual sacrifice to Hercules, which will still happen this year, since He was given tribute in the New Year ceremony, but it probably won’t be repeated next year; the monthly libations to Thor will likewise be discontinued, since they’re a trace of when I wore a hammer and had a half-Norse practice, but may remain as ad hoc; offerings to the Portuguese Lares, seen as communal ancestors or heroes, will be added to those to the Family Lares during Caristia; the end-of-year ceremony will be dropped, too, with only the cleaning of shrines on the 31st of December remaining; and I’ll also remove my annual sacrifice to the Egyptian god Khnum, which started at a time when I did clay figures with some regularity, though that hasn’t been the case at all for several years now. As with Thor, offerings to Khnum will become ad hoc, whenever I take up home pottery. The result, already published in the calendar section in the top menu, is the following:

The Egyptian exception

The only deity to whom my practices remain non-Roman is Anubis. At first, it was because I didn’t know enough about ancient Egyptian religious customs in order to adapt them; then, because the simple format that I had improvised ended up sticking. A candle, some incense and water (part of which I then pour on the graves of some of my ancestors), bows with bent knees so that the forehead touches the floor, em hotep as a salute, food offerings later consumed in full – by me and my dogs. So it was and so it remains. The only element of Romanization in it is the date of the annual sacrifice, on February 12th, on the eve of Parentalia. Not that that changes who I am, a Roman polytheist, because, again, it is not faith, creed, belief or simply which gods one worships that determines my religion. It is ritual praxis! And given that out of roughly thirty yearly sacrifices, plus over eighty sets of monthly offerings, only one is performed in a non-Roman way, there’s no doubt about what I am, religiously.

Why Anubis? For nothing more than being a canine god; and dogs are a significant part of what I practise. For instance, the addition of an annual sacrifice to Diana to my festive calendar was born out of a vow I made to Her about a decade ago, when one of my dogs underwent surgery. She survived and recovered and, as such, I fulfilled my vow and Diana later became a part of my religious practices. Quangeio is another canine element and, in the yearly sacrifice to Him, I include dog food I then consecrate, ritually make profane and then give to my dogs. My Family Lares include deceased pets – like the one behind my vow to Diana – including photos of them on my Lararium and offerings three times per month. Silvanus, too, has a connection to dogs, judging at least from the traditional iconography, and I’m not above lighting a candle to Saint Roch if I happen to find a chapel or church dedicated to Him.

Little wonder then that Anubis ended up becoming part of my religious practice. It doesn’t mean that He will remain so for the next ten or twenty years, but it wasn’t by chance and, presently, my annual sacrifice to Him is already a special religious moment I share with my dogs.

And then there are the southern waves

Will I ever use Roman rite to worship an Egyptian deity? Likely not in Anubis’ case, but it may happen with another and the reason is one: the climate! See, droughts and heatwaves in southern Europe can be caused by hot air coming in from north Africa (even sand blown from the Sahara desert hasn’t been rare) and the phenomenon is expected to become increasingly common as climate change rages on. Also, changing weather conditions mean that diseases that have thus far been largely confined to Africa may start moving north and I’ve wondered about the religions ramifications of all of this as I reflected on my practices these past few months. As a result, I started looking into heat and desert deities, which are virtually absent from traditional European pantheons, but can be found in north-African and Middle-eastern ones. Gods one could, perhaps, petition for a short or light presence so that cooler weather may return or remain, in a type of apotropaic cult where the source of affliction is addressed and placated directly, not driven out by an antagonist or adversary.

To that effect, one of the deities that’s at the top of my list of possibilities is Sekhmet. Because She’s the goddess of the fiery breath and of the sun’s aggressive aspects, maker of deserts, and She’s also connected to diseases, both as a bringer and as a healer. And in the surviving myths about Her, She’s placated out of a rampage, which strikes a very similar tone to the apotropaic cult that I have in mind. She’s thus a strong possibility, but I’m facing it with caution, because She is an old and powerful goddess and I don’t want to make a decision lightly. Especially since I could include Her in my practices in a Romanized fashion, as Dea Leonina, and worship Her using Roman rite. The next several months will tell.

If I do end up worshipping Sekhmet, would that contradict the convergence of native culture and religion mentioned at the start of this blogpost? Happily, no; and I say it’s a happy thing, since the fact that it makes sense is yet another reason that pushes me towards Her. Because the Mediterranean has been a cultural melting pot for millennia and, while western Iberia is technically located beyond the Strait of Gibraltar, it nonetheless has a long History of being part of that mixing dynamic: Phoenicians sailed along what today is the Portuguese coast and founded or developed several settlements, Lisbon among them; the Iberian Peninsula was not foreign to north-Africans, even before many of them entered and settled in following the Islamic invasion of 711; and Jewish presence in Iberia is old, like really old, perhaps even pre-Roman! That, too, is part of the mix of peoples and cultures on which Portugal was later formed. In short, the Iberian Peninsula is so close to the north of Africa that it is impossible to radically separate the two places, not only regarding people and cultures, but also the climate. Which is why taking an Egyptian deity in order to religiously translate an Iberian reality that originates in the deserts of the southern half of the Mediterranean is not just in line with a millennia-old dynamic of mixing and interchanging. It is also a natural option.

Whoever claims that Europe is white or that it stands radically apart from the north of Africa and the Middle East – culturally, genetically, religiously – is either focusing on a very particular (real or imagined) part of the European continent or doesn’t know the History of Europe. No matter how much he or she pays lip-service to “European pride” and identity.

June 2, 2020

An Iberian Jupiter

Yet don’t blame Christianity for it, or at least not for the most part. The erasure and assimilation of the Iberian Peninsula’s older religious traditions was first and foremost a result of the Roman conquest of the territory. The pre-Christian Roman conquest. Because as the new rulers settled in, so did their ways and customs, from language to laws to, yes, religion. There’s a reason why almost every one of those altars that preserve the names and titles of older Iberian deities bear not inscriptions in a Celtic or an ancient native language, but in Latin and are shaped like traditional Roman altars. One word sums up the process in its various forms: Romanization! A reminder that not every cultural-religious erasure is the work of proselyte monotheism.

This is important, because before moving into the core of this post, I want to make two things crystal clear. The first is the extent of what was lost and hence how much needs to be created from scratch if one’s to give older Iberian deities a religious place in the modern world. For with generally nothing to go by other than names and titles, a simple reconstruction just isn’t an option. You have to create! And yet – and this is the second point I want to make clear – I bear no grudge towards ancient Rome for it. Honestly, it feels ridiculous just saying it, because of course I don’t! What would be the point of harbouring ill-feelings towards a long-gone civilization whose actions took place over two millennia ago? It’s no-brainer, but… don’t underestimate the ability of some polytheists to hold deep historical grudges. And additionally, I practise my polytheism as an extension of my native culture, and since Portuguese is a product of the Romanization of the Iberian Peninsula, it would be non-sensical for me to reject my country’s Latinity in favour of some anachronic re-enactment of a lost tribe or civilization that has long been subsumed into later, multiple layers of identity.

So having said that, what follows is focused on the pre-Roman Iberian god Reue, on whom I wrote a post a few years ago, when I refurnished this blog, summing up the surviving data, what scholars make of it and my own work hypothesis. I’ve had a few more ideas since then and have come to construct a more elaborate view of Reue, which is now a full part of my religious practices and the object of a growing attention of mine.

Celestial shepherd

A few known or proposed things about Reue serve as the starting point: archaeological findings suggest a link to mountainous areas and theological closeness to Jupiter, though the Iberian theonym is never employed as an epithet of the Roman one. Rather, Larauco (of the Larouco mountain in northernmost Portugal) is used as a title of Reue or as a stand-alone with the words deo Maximo (highest god), which also serve to describe Jupiter. So we’re dealing with a jovian god, but one who, by virtue of his name and according to several scholars, also has a watery connection, which is not incompatible with known roles of Jupiter or Jupiter-like deities throughout the old Roman world.

Another contextual point is the rural nature of ancient western Iberia, as there were virtually no civitates, just oppida or fortified hilltops. Granted, by some modern standards, even a lot of Roman cities would be villages, but in the ancient Latin world there was a legal and structural distinction to be made and which I took into account.

From this arose a concept: the Shepherd of Clouds! Part of the inspiration came from one of Zeus’ epithets in the Iliad – Gatherer of Clouds – and it holistically encapsulates what little is known of Reue – the Jovian nature, connection to water and rural context – while also serving as a fertile catalyst for a cascade of new ideas about him.

Think about it: clouds are his flock, which not only makes him a celestial god, but one who’s particularly connected to rain and thus water. In his beneficial role, he helps sustain rivers and springs, mountainous and others, but if you get torrential rain and sudden flooding, that can be envisioned as his flock running amuck. The sound of a rushing wall of water is not unlike that of a stampede. Also, if you hear thunder, that too can be translated as Reue’s cattle on the move, but because clouds advance with the wind, it too falls under the god’s influence. Think of the soft breeze as air coming out of Reue’s shepherd flute or of strong gusts as his dogs. Also, because water is fundamental for life and prosperity, he appears as a fertility god as well, a side of his reinforced by the connection to cattle. And if mountain tops are covered in clouds, yet no rain falls on lower lands and there’s even a partly blue sky in the surrounding area, take it as Reue’s flock grazing on the summit, with the god sitting among his cattle and walking on the mountainous ground.

Thus a simple rural concept, which may not have seem much at first, breathes new, rich life into an old god who initially appeared so distant, so abstract, by virtue of there being so little about him in the historical record.

Trees and animals

Of course, if he’s a Jupiter-like deity, then Reue’s tree will naturally be the oak. But because he’s a west-Iberian god, one can get specific and link him not with the more famous Quercus robur, but with the Quercus faginea or Portuguese oak. Alternatively, there’s also the Quercus suber or cork oak, which is Portugal’s national tree.

And as for animals, the white bull or ox is an obvious choice, but so is the sheep and ram, plus the dog, which are all part of the shepherd’s realm. Birds are still an unclear point to me, though naturally there’s the eagle, both the Aquila chrysaetos and the Buteo buteo, and I’m also considering the black kite (Milvus migrans) and even the black stork (Ciconia nigra).

Now, there’s some divergence here from traditional animal associations of Jupiter, but that’s okay. For one, I expect the rural emphasis of Reue to result in differences and, secondly, I don’t see them as the same deity, so again, distinctions are to be expected.

King and court

Which leads to the next point, for if Reue and Jupiter are to be understood as different gods, albeit similar in several ways, how does one integrate them pantheon-like? And the answer is hierarchically and functionally. That is to say, picture Jupiter as a celestial king with an entourage or heavenly court, of which other, similar gods are members to a varying degree. This is not unlike how Greeks and Romans saw the relationship between various deities, and so one only has to insert Reue into the fold as a sort of princely figure with a more rural, even rustic identity in the celestial realm. Hence the similarities and even overlap with Jupiter, but also the distinctions, with the end-result of fully integrating into a modern Roman polytheism of a present-day Latin country and culture a native pre-Roman god from that country’s territory.

The lady by the spring

There’s also the native goddess Nabia, with whom one can make a connection with Reue both on the basis of realms of influence and the view of him as a shepherd. She’s not without a Jovian link herself, since she’s mentioned together with Jupiter in one altar found in northern Portugal. But because she’s often associated with springs and rivers, the stage sort of sets itself up for a meeting with Reue: they both exert influence on the sources and availability of water, even complementing each other; and following on the idea of him as a shepherd, picture the bucolic scene where a keeper of flocks meets a fair lady by the well or spring and they become enamored, thus forging a link between the two.

This is not without historical basis and I don’t mean Nabia’s Jovian association. In one inscription from Cabeço das Fráguas, in the Portuguese northern interior, a sacrifice of livestock is listed, together with the gods to whom it was given, and among them is Reve Tre…. One possibility being that the final letters are part of an epithet that linked Reue with the native goddess Trebaruna, who’s also mentioned in the inscription and, judging from the theonym, may have been a deity of the village well or spring. If the two were paired, it would make sense, but given that their names don’t appear together anywhere else in the archaeological record, it could have been a geographically limited pairing. In any case, the hypothesis supplies something of a precedent for a link between Reue and Nabia.

Like a letter and a sound

Before I finish, and just so we’re clear, I don’t actually believe that clouds are flocks, thunder is the sound of moving cattle and a god is walking it around somewhere in the sky. The notion of Shepherd of Clouds is a means to understand and codify.

If you want a very simple analogy, I don’t believe the sound /a/ actually looks like the letter a, yet I’m content with the traditional Latin grapheme and engage with the sound through it. It’s a way to grasp, depict and make use of something that we can hear, but not see or touch. And the fact that the letter is a human-made representation of a phoneme doesn’t make it false – its everyday usefulness and shared understanding makes it true.

Something similar applies to Reue: I believe him to be a real entity with agency, able to exert influence on certain phenomena and activities, and his depiction as a Shepherd of Clouds is a way of engaging with him. Of making sense and thus interact. Just as grapheme is a way of reaching out to a phoneme, of giving it form it and using it, without it meaning that the former actually is the latter or truly looks like it.

So salve to Reue,

the Rustic Jupiter, Iberian Jove,

the Shepherd of Clouds and Thundering Flocks,

He of Breezes and Gusts,

of the Flute and Hounds,

Nabia’s Divine Friend!

August 9, 2019

Roman polytheism: an extended definition

Roman polytheism is the worship of many gods, Roman and others, according to Roman ritual tradition, without a prescribed orthodoxy, without a defined moral doctrine and within a romance cultural context.

There’s a lot to unpack here, so let’s take it bit by bit:

1. Worship of many gods, Roman and others

It’s not a religion restricted to a single pantheon, but open to any deity from anywhere, though one may, if one so wishes, focus solely on traditionally Roman gods. And this trait means that it cannot be defined as the religion of those who worship, follow or work with the Roman gods, since that would be incomplete – it can equally be the worship of other deities – and also non-sensical, since those same gods can and are worshipped in other religions as well.

I keep insisting on this point, but clearly I need to: we’re not in a Abrahamic-like context where belief in one set of gods excludes belief in all others and therefore if you believe in them and/or worship them, then you’re necessarily of a specific religion. This is rather an open game, not a zero-sum one. Belief alone may not be sufficiently indicative – it may not even be enough to qualify you as a polytheist – and the same gods can be worshipped differently in different traditions. Therefore, belief in and worship of Roman gods doesn’t automatically make you a Roman polytheist. It can just as easily make you a wiccan, if you do it the wiccan way.

2. According Roman ritual tradition

What makes one a Roman polytheist is, simply put, how one worships the gods, i.e., what are the ritual rules that shape one’s religious practices. In other words, it’s an orthopraxic religion, but what exactly is meant by a modern Roman praxis is still somewhat fluid and my own views on some details have changed. This is, after all, something that’s being revived, not inherited from the past in an unbroken tradition, so there are gaps in our knowledge and changes in context – political, social and cultural – that are bound to have an impact. Still, if I had to list what makes a modern Roman orthopraxy, based on History and present practices among fellow cultores, I’d say the following:

a) Marking the Calends, Nones and Ides of each month, determined either through lunar phases or fixed solar dates, as per the Julian calendar or the Gregorian one. And honouring particular deities on each of those days: Janus and Juno on the Calends, Jupiter on the Ides, the Family Lares on all three. This is just the bare minimum and there’s nothing preventing one from adding other deities to those being worshipped on any or all of those dates or even from having other monthly sacrifices, according to one’s personal devotions, local or regional traditions, domestic or communal practices, culture or philosophical persuasion;

b) In every ceremony in Roman rite, even if only a semi-formal one, the head must be covered with a piece of cloth, Janus is one of the first deities being honoured and Vesta one of the last. Again, this is just the bare minimum and there’s nothing preventing one from adding other deities to the opening and closing sections of a ceremony, as per personal, local, regional, domestic or communal devotions or traditions, culture and philosophical persuasion;

c) Maintaining a distinction between celestial, terrestrial and domestic deities or divine aspects on one side, and infernal ones on the other: the main hand with which ritual gestures are performed for the former is the right, for the latter it’s the left hand; food given to the former can be consumed by the living after being deconsecrated, that given to the latter cannot; offerings to the former are burned either at home or on a raised altar or fire, those to the latter are burned or buried in a pit;

d) Ritual fire is preferred for burning offerings to most deities – watery ones may be an exception – and should be used whenever possible. If resorting to fire is truly impossible, consecrated offerings should be deposited in meaningful and appropriate places;

e) Before a ceremony is concluded, one must ascertain the gods’ (dis)satisfaction through divination or simply give an expiatory offering;

f) And at least in more formal ceremonies, the main offerings – i.e. those given to the deity to whom the sacrifice is dedicated – are consecrated by being sprinkled with wheat, wheat flour or salted wheat flour, together with a small prayer that is up to you, your family or community to construct;

g) Finally, ceremonies call for physical cleanliness, so at the very least you should previously wash your hands and face.

If you do all of these things – not just some, but all – and if they constitute at least the majority of your religious practices, than in my book at least you’re a Roman polytheist, even if the gods you worship are almost all of them non-Roman. Though, mind you, some of them will necessarily be, because, as listed above, the orthopraxy requires monthly sacrifices to Janus, Juno and Jupiter, as well as opening and closing offerings to Janus and Vesta, so even if all others are of different traditional pantheons, you’ll still be worshipping many gods, Roman and others.

3. Without a prescribed orthodoxy

If ancient Roman polytheism had an orthopraxy, it did not have an orthodoxy and the same should hold true for the modern version of the religion. It doesn’t mean there were and are no religious beliefs, no faith, but simply that they’re not regulated and can vary depending on individual or group experiences, traditions, culture and philosophical persuasion.

Are the gods mortal or immortal? Are they morally perfect or imperfect? Do they communicate with us humans, how so and to what end? Are there other gods of which we know nothing? Is deity A the same as deity B or are they distinct? How do you define a deity and what entities do you include in the definition? Is there a soul? If so, what is it and how does it operate? Is there an afterlife? If so, how does it work and what does it entail?

These and other questions are open to interpretation and different cultores will have different answers for them. And that’s okay! They’ll still be polytheists if they believe in and worship many gods, they’ll still be my coreligionists if they worship them the Roman way and that constitutes the majority of one’s religious practices. Simply put, Roman polytheism is a religion that can include many philosophies and theologies, not just one that’s elevated to the status of universal orthodoxy. Different individuals, groups, families and communities will have theirs.

Now, in case you’re wondering, doesn’t the necessary belief in many gods in order for one to be a polytheist constitute a regulated doxa? And the answer is that believing in many deities relates to the basic concept of the religious category that is polytheism. In other words, it precedes the definition of Roman polytheism, which is born out of that category and its defining criteria, so belief is already assumed. If you – freely and legitimately – do not fit those same criteria, then you’re not in the general category of polytheism; if you do, the next step is to determine which type of polytheism, which is where specific religions and their definitions come in.

4. Without a defined moral doctrine

This is perhaps the most contentious point, because we’re used to equating religion with morality. But ancient Roman polytheism had no sacred scriptures and so lacked a mechanism by which it could fix a moral doctrine – and hence an orthodoxy, by the way. Sure, there were plenty of people who would write texts praising or admonishing human behaviour and there were traditional customs and norms that determined what was (im)proper. Here’s the thing, though…

There’s a tendency to mistake the part for the whole. Often, we read someone like Cicero or Seneca and assume what they say about gods and morals to be a universal doxa of Roman polytheism, but that’s a fallacy. What Cicero and others wrote were their perspectives, those of members of the elite. They were certainly shared by others, but were not universal, not mandatory. They were not the official teachings of Roman polytheism.

In other words, those texts people wrote were not scripture, but individual opinions based either on the philosophical school the author adhered to or on the traditional norms and customs of his community. But different people had different philosophical persuasions, so just like in the matter of orthodoxy this would result in theological diversity, you could get different views on what was (im)proper. Or if views on morality were based on traditional norms, apart from the possibility of clashing with philosophical perspectives, they are naturally open to change as society itself changes.

So no crystallization, no universal source, no absolute views. Whatever values were upheld could of course be religiously expressed, as in the cult to specific virtues, but as mentalities and thus values evolve, so does its religious expression, either through a reinterpretation of old forms or a creation (or calling) of new ones.

Just as a lack of orthodoxy simply means that Roman polytheists have no regulated beliefs, so too the lack of a defined moral doctrine merely results in the absence of regulated, universal gods-given code of conduct for everyday behaviour. Rather, it varies along the same lines as belief. Divine inspiration is a factor, granted, but it’s inspiration, not decrees, and different deities inspire different things, together with inputs of a philosophical, cultural, communal or social nature. And if morality is not a matter of divine commandments, of what the gods (don’t) want us to do in our everyday lives, then it becomes an issue of human society, to be discussed and determined by its members in all their diversity. Simply put, morality is a social issue, not a religious one, not one that is determined by religion – though it can be expressed through it.

5. Within a romance cultural context

Here’s another thing about ancient Roman polytheism: it was indistinguishable from communal life and identity. It wasn’t a religion one picked and thus converted to, but one you were born into, inheriting the corresponding family and hence religious and civic duties. And by that measure, it was a culturally tied religion. Having it meant having specific social and political ties, but also, at least to some extent, a specific language and culture.

This poses challenges to the modern Roman polytheist. For one, the idea that it’s something inherent to one’s family, State and culture clashes with modern religious liberty, which is predicated on the individual’s right to chose a religion or none and on a separation between citizenship and religious affiliation. And then there’s the historical fact that Roman political and cultural unity no longer exists: what used to be the empire fragmented into multiple States and the Latin language and culture followed suit, fragmenting into regional dialects out of which were born the modern-day romance languages.

In practical terms, this dissolves whatever one-on-one link one might want to establish between religion, culture and nationality. Whereas the term Hellene is tied to a single country (Greece) or ethnicity (Greek), thus allowing for an overlap of different layers of identity – religious, cultural and national – no such simple correspondence exists in the case of Roman polytheism, because there is not just one, but many Latin languages and cultures: Portuguese, Asturleonese, Castilian, Aragonese, Catalan, Occitan, French, Romansh, Sardinian, Ligurian, Italian, Romanian – and several others, plus extra-European varieties brought about by Europe’s colonization of Africa, Asia and America. If one is to have modern Roman polytheism culturally tied, then it will be a much more universal religion than its ancient version thanks to the development and geographic expansion of multiple Latin languages and cultures.

But should it be culturally tied? My answer is yes. Unlike a political connection, which might clash with modern freedom of religion, a cultural link is both consistent with the past and entirely possible within the modern context, especially when one considers that culture isn’t genetic, but acquired, and so anyone who isn’t native to one can put the effort to adopt it.

Mind you, having a Latin culture alone won’t make you a Roman polytheist, otherwise every single Portuguese, Spanish, French or Italian person would inherently be one. The defining criterion is following the orthopraxy, not your nationality, ethnicity or even beliefs. But culture provides you with a context: a Latin language to use in religious ceremonies, a net of traditions and customs that blend with your practices and infuse them with an everyday quality by virtue of being part a living, everyday culture, not a recreation or re-enactment of a long-gone city-State and its social apparatus.

A note on colonialism

Whereas the cultural link may come naturally for Europeans, it may not be so for those elsewhere in the world, because there European languages and cultures are the product of colonialism and its violent erasure of native civilizations. For those in that situation, the options are multiple: not be a Roman polytheist, which is legitimate; be of dual tradition, practicing Roman polytheism along side, but separate from native religions; or go for a blending of the two at some level, where you resort to the orthopraxy, contextualize it in a Latin culture (e.g. Spanish) and worship Roman and non-Roman gods together.

As an example, that’s kind of what I do, though at a much longer chronological distance. You see, Latin wasn’t native to the Iberian peninsula, but was brought over by conquering Roman armies and settlers, who supplanted native identities, languages and cultures. Basques are probably all that remains of pre-Roman Iberia, and then there were later invasions and subsequent additional cultural layers being added. So by linking my Roman polytheist practice with my native Portuguese context, the result is naturally a blend: there are elements of Arab culture in it (namely in vocabulary and cooking), because the Portuguese are partly Arabized Latinos, and the pantheon is naturally mixed, with traditional Roman deities being worshipped alongside pre-Roman ones. Take Reue for instance, whom I see as a member of Jupiter’s retinue, or Quangeio, Mercury’s companion in my western Iberian cult to Maia’s son.

And just to add a picture

[image error]

So to sum it up, belief in and worship of many gods makes you a polytheist as a general category, worshipping according to the Roman ritual praxis makes you a Roman polytheist and a Latin language and culture, either native or acquired, provides for a cultural context that ties your religious practice to a living, everyday culture derived from that of the ancient version of the religion. As expressed in a simplified form in the scheme above.

Will this result in a very diverse religion, with different theologies, different philosophies, different views on what’s moral and immoral and tied to different cultures and languages, since there so many options, and thus with national or regional specificities? Certainly! But why should that be a problem? And how does that break with a past that was also diverse, with different families, cities, provinces and communities having their specific practices? This is unity in diversity, unity through a common basic ritual practice, not unity in uniformity.

April 15, 2019

Mercurial devotion

1. The fourth day of the fourth month

As said in other occasions, there’s no historical record of a Ludi Mercuriales or that at any time ancient Romans celebrated the anniversary of Mercury. But because I’m not talking about a fossilized religion, nor do I practice a re-enactment of the past, it is natural that time, devotions and religious experiences make way for new festivities. The 4th of April – the fourth day of the fourth month – is one such case: based on the historical link between Hermes/Mercury and the number four, I picked that day to celebrate the birth of that god. And I strengthened the symbolic charge by expanding it in order to include the first four days of April, a month that begins with April Fool’s, which is another appropriate date to honour a trickster.

Last year, April 4th was also a Wednesday, the old Dies Mercurii, and for that reason my offerings and tributes came in packs of four as much as possible: four sweet dishes, four toasts, four cairns on which I poured four offerings, four lottery tickets, four mourning offerings during four days, four floral tributes, etc. This year, the date fell on a Thursday and so the numerical emphasis was less stressed

[image error]

This year, for Mercury’s anniversary, I made two sweet dishes – aletria and a crackers’ cake – along with several sugar-free pancakes so my dogs could eat them and thus have a seat at the god’s table. All consecrated to Mercury during the ceremony on the morning of April 4th, with the first portion of each being given to the deity and then rest was returned to the human sphere so my family and I could eat it. There were also libations of medronho strawberry and honey liquor and offerings of fennel, cinnamon, wine and honey, a wreath for the shrine, another to hang on the front door and a strawberry tree to plant in a family plot of land this month, it too consecrated to Mercury with portions of salted flour, honey and liquor. And to top it off, adding to small walk, cairns and offerings from the previous day, as well as the sacrifice to Maia on April 2nd, I also bought a lottery ticket.

In the end, there was the expected feeling: the sense of work done, duty fulfilled, devotion piously expressed and nurtured bonds. And joy.

2. The triad and the family

My devotion to Mercury doesn’t come alone. It’s part of a greater whole, of a modern cult still in construction and focused on the roads, trails and pathways, in the perpetual movement and interconnectedness of all things, linked to the Iberian west and, when it comes to philosophy, consciously influenced by the Buddhist school of Madhyamaka. At the heart of its pantheon is of course Mercury, together with his mother Maia and his companion Quangeio, the Iberian dog god, and together they form the central triad of said cult. Around them orbit other deities: Faunus, Silvanus, Proserpina and the Lares Viales, who are the divine host of Mercury Vialis – the Wayfaring Lord of Pathways. And because the cult is meant to be an Iberian branch of modern Roman polytheism, there’s also Janus, Jupiter, Juno and Vesta, the Family Lars and the Penates, fundamental deities of Latin orthopraxy.

As a way of deepening my mercurial devotion and with the possibility of enlarging the pantheon, I’ve been looking into Mercury’s maternal relatives, particularly Pleione and Atlas. The former, by being of the Oceanids, poses a dilemma, in that I must choose one of the versions of Okeanos, if the oldest, according to which he was understood as the titan of the great river that enveloped the world and origin of all its sources of fresh water, earthly and celestial, if the later version, according to which he’s the titan of the oceans and hence salt water.

Given that the theonym Pleione carries the many of increasing in number, particularly flocks, both senses have merit, at least in a Portuguese context, since clouds can be religiously understood as a celestial flock – in which case Mercury’s grandmother would be a multiplier of clouds and as such a deity of mist and rain – but in Portugal the foam on the top of sea waves is colloquially called “little rams”, and in that case Pleione would be a stirrer of maritime waters. But given that her daughter Maia is a mountain nymph, my preference goes for the former hypothesis.

Reinforcing it is the idea of Atlas as a god of astronomy, an interpretation that’s rich in possibilities, since it awards the titan the responsibility for the movement of the sky, which in a modern sense that takes into account the present knowledge about the planet and the solar system makes Atlas the god of the Earth’s axis. And that amounts to a celestial aspect that thus touches Pleione’s sphere as a goddess of heavenly flocks, and Maia, daughter of the two of them, is a mountain nymph, i. e. of the earthly extremities where mist and clouds settle – where Pleione’s flock grazes – and touch the sky that turns around Atlas.

These are still preliminary ideas, but at the moment it’s the mental course that I’m following.

3. One for all…

Finally, there’s a small ritual habit that I’ve been acquiring: that of, whenever I perform a monthly sacrifice to one of the elements of the aforementioned triad, adding an offering to the other two. In other words, when paying tribute to Mercury on the first Wednesday of every month, I offer to Maia a portion of honey and another to Quangeio. Whenever I honour the daughter of Pleione on the Ides, I pour an offering to Mercury and another to the Iberian dog god. And when, on the 24th of every month, I perform a small sacrifice to Quangeio, I offer a spoon of honey to Maia and another to her son.

It’s something that adds to the inclusion of Mercury’s mother and companion in my prayers to him every morning and every night and to the portions of wheat that I sometimes dedicate to the two of them whenever I paying tribute to the Fleet-Footed God on a cairn or by a road. Ritual expression of a connection between them and of a devotion that does not exist alone, but as part of a greater whole.

February 2, 2019

Where I stand

For that reason, for future reference and so that there are no doubts on where I stand on the field of ideas, I’ve decided to write the essentials of some of my ideological positioning, though a lot of what I’m about to say is public knowledge, since it’s published and freely available to anyone in this blog’s menu. But it seems a clearer and more direct approach is needed.

1. I like philosophy, but…

I like philosophy. I read philosophy, western and eastern, ancient and more recent. I tutor philosophy to high school kids. And there are philosophical doctrines of which I’m fond of and have been integrating in my theological views and religious practices. Therefore, it’s not a subject that’s deprived of interest to me, but it’s also not one I’m particularly focused on.

What I mean by that is that, generally speaking, I don’t particularly care where other polytheists stand, philosophically. So long as they believe in and worship many gods – not many as masks of a One or honour exclusively one out of many – they’re polytheists in my book, regardless of how distant their choice of philosophy is from mine.

2. I’m not in search of the metaphysical truth

As a result of that, I generally also don’t engage in theological or philosophical debates on who’s right or wrong about the metaphysical truth of things. I see such matters as speculative and thus, ultimately, they’re up to each individual to decide, which is why I don’t particularly care if other polytheists are Platonists, Stoics, Epicureans or of any other philosophical persuasion, western or eastern, pre-Christian or later.

At best and generally speaking, I may join conversations on the subject so as to understand other people’s worldviews, the ideas they’re comprised of, perhaps exchange notes and test thoughts, but without the final goal of arriving at an ultimate metaphysical and spiritual truth. I don’t particularly care where others stand on the principle of do ut des, the gods’ immortality, the number and nature of human soul(s), the existence or not of fate, etc. I have my beliefs, others have theirs. So long as they believe in and worship many gods as individual entities, they’re polytheists as far as I’m concerned.

Whether or not I find other people’s philosophical position interesting, enlightening, optimistic, convincing or conducive to a relationship with the gods is generally irrelevant. They’re other people’s beliefs and philosophical conceptions, not mine. It’s up to them to decide where they stand and how they feel about it.

3. My exceptions

I’ve been saying “generally”, because there are exceptions. One of them concerns basic definitions and their meaning. I therefore have no problem, for instance, disputing and correcting those who claim to be polytheists, but believe in no gods, one god, worship only one or define polytheism in a skewed manner.

I also dispute and correct erroneous ideas on History or opinions on the past that lack support from the historical record. The same applies to other modern scientific topics, generally speaking, though I’m more comfortable with some than others.

And I oppose racist, xenophobic, homophobic or supremacist ideas, whether they’re blended with religious views or not. I draw a line at basic human decency and sanity, just as I do at basic definitions.

4. My definition of Roman polytheism

The ideas above are to me fundamental and are reflected on the value I place on ritual orthopraxy and my definition of Roman polytheism as worship of many gods, Roman and others, according to Roman ritual practice.

Notice that it says nothing about belief – outside the basic concept of polytheism (see above) – nor does it mention moral values, political ideology, social organization and philosophical persuasion. And that is so because those things are to me irrelevant for the basic definition of Roman polytheism.

In practical terms, this means, for instance, that I have no problem with Roman polytheists who subscribe to Platonism and would worship alongside them, even though I’m not a Platonist myself and the more I read about it, the less keen I am on it. And in another example, I believe the gods interfere in human affairs and that there is efficacy in ritual, but I have no problem with Roman polytheists who are sceptical about do ut des, but still worship the gods, for whatever reason, and I would worship alongside them.

5. I value orthopraxy more

For me, what makes one a Roman polytheist is how one worships, regardless of one’s theology and choice of philosophy, generally speaking. The gestures, the structure of both rite and month, the basic how-to. Everything else is entirely up to the individuals, families and groups.

And yes, this is based both on the historical example of ancient Roman polytheism, which was orthopraxic and non-orthodox, and the personal conviction that its modern version must detach itself from political, tribal and social realities of a bygone period.

My approach is that of identifying the fundamental traits of ancient Roman religion – like orthopraxy and non-orthodoxy – and then apply them as much as possible and desirable to the modern context, instead of trying to replicate or re-enact the specific product of that combination of traits and context that was in existence in the past. Fossilization is not my goal.

6. I’m a conventionalist

It is for that exact reason that when defining Roman polytheism I also say nothing about moral values. If there was no orthodoxy, then there was no doctrinal position regarding philosophy and everyday behaviour. Simply put, Roman polytheism had no moral principles, just ritual traditions. And what morality it presented, it was of social origin, though it could be expressed and codified in a religious manner.

There’s nothing historically new in this. A common feature in pre-Christian cultures of ancient Europe was a full merger of the social, political and religious aspects of life, with no real distinction between them, contrary to what´s common today. They were different sides of traditional customs. As a result, tribal and civic identity was one with religious identity and the performance of priestly roles often fell on political leaders and magistrates. And hence also why religiously expressed moral values were those prevalent in the society where the religion was practiced.

This doesn’t mean that I believe that the revival of Roman polytheism should imply a reconstruction of past social, tribal and political structures, because that would be a form of fossilization. As already mentioned, my position is that one should identity fundamental traits and then apply them to the modern context. In this case, if ancient Roman polytheism had no orthodoxy nor moral codes of a religious nature, just reflections of the socially prevalent values, then the correct course of action is to maintain the non-doctrinal dynamic and let it mix with the modern world, including on moral values, instead of, I say again, replicating or re-enacting the past product of that mix of traits and context.

You may therefore call me a conventionalist: morality is the product of mutable social ideas and conventions, not of divine decrees handed down from above. It can certainly be expressed in a religious fashion – through myths, proverbs or manifestations of belief – but as convention changes, so does its religious reflection. Otherwise, either the gods were amiss in the past regarding things like the value of human life or being a Roman polytheist today means having a set of fossilized values. Since I subscribe to neither of those two views, I attach no moral commandments to the gods.

Some see in that a recipe for chaos, but I see it as something liberating and an opportunity to discuss norms, laws and values in a free and rational manner without being limited by dogmatisms or fossilized sacred scriptures. And that’s a good thing! It’s a recognition that things change, including the values by which a society is governed, and it’s taking part in that change in an open manner. It’s not about submitting to modern morals in an acritical fashion, but looking at it freely and critically, preserving it where it must be preserved, treasuring it where it must be treasured, criticizing and demanding changes where it must be changed. Without the goal of freezing it, of simply turning back the clock, of changing it for the sake of change or because the gods say so or a sacred book commands it. You won’t see me using arguments like X should be unlawful because deity A forbids it.

It doesn’t mean that I don’t think that gods inspire human action and behaviour, but different deities inspire different things (e.g. virginity or lust, war or peace, order or trickery) and that inspiration comes on a personal level, not by means of a universal decree. It is my belief that divine communities operate with their own rules, humans with theirs, and though there may be an exchange of ideas, the two work autonomously.

The only area where I admit the possibility of divine instructions are rites, the management of sacred spaces and human conduct within them, here too with elements that may be diverse depending on the deity. And even on that note…

7. How conventionalist am I?

I’m such a conventionalist, that I even propose that orthopraxy should take into account social morals and adapt itself in cases where ritual tradition clashes significantly with laws and social conventions. In other words, a renegotiation with the gods when that which traditional in their cult goes substantially against what is acceptable in the society where the religion is practiced. One can certainly try to change laws and social conventions, if there are motives, support and a real need for it, but one can also adapt religious practices.

For instance, if it’s traditional to sacrifice dogs to a given deity, I hope – indeed, emphatically defend – that there’s an adaptation of the ritual practice considering the value and protection awarded to canines in western societies, replacing the animal offering with a figure of a dog.

And also as an example, if Roman ritual tradition awards the paterfamilias a leading role in domestic ritual practices, I hope – indeed, emphatically defend – there’s a transition to a modern dynamic that’s more equalitarian and not only awards an equally important role to the mater familias, but also goes beyond a relationship between male and female and includes same-sex couples.

8. I’m a Roman polytheist because…

In the end, it’s fair to ask why am I a Roman polytheist, even more so if, as is my case, one believes that the same gods can be worshipped in different ways and so there’s nothing compelling me to follow Roman tradition in order to honour Mercury or Minerva. I’m not interested in rebuilding ancient Rome and its civic institutions, in reproducing the values that were prevalent there two thousand years ago, not even in restricting myself to the schools of philosophy there were current among ancient Roman elites. So why am I a Roman polytheist?

The answer is threefold, starting with a theological reason, in that I genuinely believe there are many individual deities and want to worship several of them. That makes me a polytheist, but what type or of what tradition?

That’s where the second reason kicks in: culture! I’m Portuguese, born, raised and living in Portugal, and since my native language derives directly from Latin, just like my country’s culture is predominantly of the same matrix, I decided that take that to the next level and go for a religion that’s equally Latin. Ergo, Roman polytheism!

But then one needs to ask: am I comfortable with it? Do I feel at home or is it kind of a mismatch? Just because you’re a European Latino doesn’t mean you have to go for a Latin religion. After all, a lot of Portuguese pick other traditions, including monotheisms, or none, freely and legitimately, so it’s not in any way compulsory. And yet, a decade after making my choice, I can honestly say that yes, I feel at home. More than comfortable, I’m happy in a religion that embraces diversity, is non-exclusivist, has no orthodoxy and no moral doctrine, thus awarding me the freedom to worship many gods, be they traditionally Roman or not, adhere to a philosophical school of my choosing and face the challenges of the society I’m part of without dogmatic constrains of religious nature.

Other people may of course have different reasons, but these are mine. And this is who I am, religiously, ideologically. How you choose to react to it is up to you.

January 7, 2019

New Year, all year (and ritual forms)

All in the first step

In late December, while preparing things for the end of the month, I realized that my New Year ceremony, which follows the same structure for sometime now, includes almost all of the deities I honour yearly. It wasn’t intentional, but something that was built throughout the years, as I’ve added gods and goddess who, besides Janus, are auspicious or relevant to me and my parents, like Minerva, Jupiter, Diana, Mercury, Maia, Fortuna and Spes.

And then I thought: what if I took that accidental reality to its full intentional consequences, honouring, after the sacrifice to Janus and calends’ tributes, all the deities to whom I dedicate an annual ceremony? If, for instance, on September 5th I pay tribute to Arentio and Arentia, why not add them to the list of supplementary New Year offerings? It makes sense, it’s meaningful and so I did it. And the result was the following sequence of individual and collective deities:

Family Lares, Penates, Vesta, Nabia, Silvanus, Mercury, Maia, Quangeio, Juno, Hercules, Minerva, Diana, Apollo, Arentio e Arentia, Faunus, Reue, Jupiter, Fortuna, Spes and Ingui-Freyr.

There’s a logic to the sequence, which starts with the domestic realm, that naturally includes one’s ancestors, housewights, the goddess of the domestic hearth and then, via my personal theology, Nabia and Silvanus, the former because my Family Lar is a local aspect of Her and the latter because He presides over of the local Lares of my home city and ancestral land. Then one leaves the home and at that stage come offerings to the god of roads, Mercury, as well as to His mother and companion, Maia and Quangeio, with specific requests for me and my dogs. Then follows Juno, with prayers in my mother’s name, and Hercules, with prayers in my father’s name. And then, with more general requests for blessings, luck, health and protection, come tributes to the remaining deities on the list, with a Norse guest at the end.

Multiplication

There are however two deities on the sequence to whom I have no annual ceremony – Fortuna and Spes. The most obvious solution would then be to add two dates to my festive calendar, but it occurred to me that there’s an alternative with symbolic value as well: that of, in each sacrifice in the first nine days of the year, pouring an offering of honey to Fortuna and another to Spes.

Note that to me New Year isn’t just a day, but a whole festive season that extends from day 1 to the Agonalia of January 9th, which I dedicate to Janus, who thus presides over the beginning and end of the celebrations at the start of a new cycle of twelve months. In between, there’s Vialia, dedicated to Mercury and the Lares Viales for the opening of ways, literal and figurative, in the starting year, and Apotropalia, dedicated to Apollo with requests for protection and health. Note that all of these gods are linked in some way to door and entryways, for which reason they mark my celebrations at the doorways of a new year.

A growing list

But the number of deities honoured in the New Year ceremony will grow past the list above. The idea of paying tribute to all the gods and goddesses I worship throughout the twelve months had the unintended consequence of making me reconsider the rite I use for Norse deities, which is a mixture of Scandinavia and Roman elements, but not to the point of allowing a jump from one ritual praxis to another. They require separate openings and foci, so it wouldn’t be easy to annex a Norse section to the New Year ceremony.

The solution, in all likelihood, will be the construction of a new rite that must be essentially identical to the Roman, though with some particulars, just like the ritus graecus

Changes to the calendar

There’s another unintended consequence of the decision to add to the New Year ceremony all the gods I worship annually: by changing the type of rite used for Norse deities so as to include them fully in a Roman ceremony, I can honour them on the Calends or Nones without having to light an additional ritual fire and thus with the freedom to perform Freyja’s annual sacrifice on May 1st and Njord’s on July 7th.

Which adds to a review I already had in mind, namely changing the name of the festivity of December 31st so as to use Transitalia for the October 4th sacrifice to Mercury and the Lares Viales (a topic for another post), shifting Anubis’ offering day to February 12th so as to be on the very eve of Parentalia and adding Hephaestus to my religious practices, with a sacrifice on January 19th. But more on that in a few days.

In the meantime, happy New Year!

October 20, 2018

Check your assumptions

So every now and then, in conversations with pagans and polytheists or by reading what they write, I find ideas and expressions that are seen as natural or obvious in religious matters, but which can make no sense when one is discussing traditional polytheisms. They’re not used maliciously or even by conviction – though correcting them can sometimes lead to heated resistance – but mostly out of habit, because they’re ideas and expressions one hears often in everyday life. Yet, just because they’re habitual or deemed obvious doesn’t make them right, just harder to deconstruct by reason of being so deeply rooted in our thinking. And because of that, though I’ve already addressed them before, I’ll go through it once again.

Abrahamic features

I’m speaking specifically about a set of characteristics of the Abrahamic monotheisms – Judaism, Christianity and Islam – that have shaped the vocabulary we commonly use. And they’ve done so thanks to the cultural predominance they’ve enjoyed in the western world for more than a millennium, due to which it is only natural that the way Abrahamic monotheisms conceive religion is, by default, the very same that Europeans or North-Americans usually resort to when thinking and talking about the subject. It’s what is obvious to us, not because it’s necessarily true, but because it’s was we’re used to by virtue of the culture we grew up in.

Case in point: the assumption that one is a Hellenic polytheist just because one believes in the Greek gods. It’s a reasoning that works very well in religions where belief in one or in a set of deities immediately excludes the belief in other(s), so if I have a belief in them, then I’m automatically of that religion. Thus, if I believe that Jesus Christ is the son of God, that makes me a Christian, because such a belief is not shared by Jews and Muslims. Or if I believe in Allah and that Muhammed is its prophet, that will make me a Muslim, because that belief isn’t shared by Christians and Jews.

This is a zero-sum game that’s at home in the exclusivist nature of Abrahamic monotheisms, which, by virtue of their cultural predominance, have become a full part of how one normally thinks and discusses religion in the western world. It’s the underlying assumption in simple questions like “which gods do you believe in?”, by which one tries to uncover the religion of the person being asked. And it’s so deeply rooted – or is so common in everyday life – that even militant atheists, who fashion themselves as staunchly anti-religious, nonetheless follow the Abrahamic line of reasoning when criticizing the exclusivist posture of “every religion”: why is yours true and all others false, which is your god real and the others not, etc.

Here’s another example: the assumption that one is a Norse polytheist if one worships Norse gods. Once again, this sort of reasoning is at home in Abrahamic monotheisms, where belief in a deity by exclusion of all others easily amounts to its cult. It’s an exclusivist dynamic that says that if I want to worship a particular god, then I have to join the religion that defends his existence, upholds his commandments and pays homage to him, because all others do not believe in him, do not follow his teachings and therefore do not respect him and do not worship him. An expression of this idea that I know from personal experience is some people’s reaction whenever I say I’m a Roman polytheist: “that means you worship the Roman gods!” (which is only partially true) or “you uphold the values of the gods of Rome” (which does not compute).

Plurality isn’t just a word

Why are these and other assumptions nonsensical in a polytheist context? Because, simply put, polytheism is not monotheism with more gods! Divine plurality has consequences that result in a notion of religion that’s different from the Abrahamic one and thus requires the usage of a vocabulary that’s also different from the one we’re accustomed to.

For instance, using the word “faith” as synonymous of religion. It’s something that’s tremendously widespread in the anglophone world (e.g. interfaith) and it makes perfect sense in the case of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, because they have an orthodoxy emanated from sacred scriptures and are thus religions with declarations of faith! I believe as a fundamental feature! For that reason, and once again due to the cultural predominance of Abrahamic monotheisms that makes their conceptions natural in our eyes, it is equally common to define religions and religious categories mostly if not exclusively by belief. Take, for instance, the idea that a henotheist who believes in many gods, but worships only one, is nonetheless a polytheist because she/he acknowledges divine plurality in principle. That amounts to saying that religious cult is indifferent, that belief or faith is everything! I believe as a fundamental feature!

Though polytheism is a diverse category and not a single religion and there are therefore internal differences, it is nonetheless a category where multiple religions have an orthopraxy – correct ritual practice, ritual rules – but lack an orthodoxy. It doesn’t mean that there are no beliefs, just that they are not regulated, varying freely depending on the individual, groups, theological currents or philosophical convictions. Additionally, not only is belief free, it can also be open, lacking the exclusivism that characterizes Abrahamic monotheisms. Which means that, apart from not denying the existence of any god, regardless of whether or not one worship it, it also entails the possibility of worshipping any deity, no matter the pantheon it comes from.

This, in the end, is an ultimate consequence of the divine plurality that’s present in the meaning of the word polytheism: many gods and thus many beliefs, many cults, many forms of conceiving and worshipping many deities. Legitimately and freely. And it explains why the aforementioned assumptions, while logical in the Abrahamic monotheisms, may be non-sensical when talking about polytheisms.

One is not a Hellenic polytheist if one simply believes in the Greek gods, because that belief is not exclusive of that religion. Similarly, one is not a Norse polytheist if one simply worships the Norse gods, because they can be worshipped in different religions and in different ways. A religion that has no orthodoxy cannot be called “a faith”, because by not having regulated beliefs, but free and thus diverse ones, it has no uniform doctrine that can speak for the whole of that religion. What would, for instance, be the “Hellenic faith”? Believing in the Greek gods? That’s not sufficiently specific, because polytheists from other traditions may share that belief. A better criterion would be ritual practice – the orthopraxy – where the manner of worshipping the gods determines to which religion one belongs: Wicca if you do it the wiccan way, Roman if you do it the Roman way, Norse if you do it the Norse way, even if the deities being honoured originate from different pantheons. But in that case, we’re in the realm of religions that are defined not by an orthodoxy, but an orthopraxy – and that was true for many of the traditional polytheisms of the ancient word. Which means that a henotheist who worships a single god is not a polytheist, because even if there’s a belief in many, we’re not talking about a religion defined by a faith or an orthodoxy, but by an orthopraxy. Meaning, that henotheist lacks the criterion of plurality in worship, which is as or more important than belief in religions defined by ritual practice.

The tip of the iceberg

These are just a few examples of how, often without realizing it, we project features and dynamics of Abrahamic monotheists onto the way we speak of and think about other religions, in this case orthopraxic, non-orthodox and non-exclusivist polytheisms. There are similar issues with the notions of sacred space, for a temple is not necessarily a building where groups of worshippers enter to pay homage, as if it were a synagogue or a mosque. Or with the idea of moral codes, because we’re used to seeing religious leaders pontificating about people’s daily behaviour, stipulating what should and shouldn’t be allowed based on a moral code believed to be divine in origin. Or with the idea of scriptures, because we’re used to the practice of discerning a higher will in particular texts. The list goes on.

Deconstructing the habit of using terminology and frameworks seen as obvious for being common isn’t easy, because it demands change in how we think and a constant attention to what’s being said and done until new habits are created. But it’s something that has to be done if one is serious about reviving ancient religions in a modern world. It’s not enough to believe in or worship the same gods as in the past. One will not be doing a good job by creating, for instance, a Church of Odin where “believers” gather every week to pray, read passages from the Eddas, toast and hear sermons about faith, values and exclusive unwavering loyalty to the Norse gods. That would essentially be monotheism with more gods or with a different god: same dynamics, same ideas – the ones we’re used to – but with other deities.

One final and important note, just so I’m clear: I’m not saying this out of a view that Abrahamic monotheisms are evil and should be eliminated from our lives. They’re different religions entitled to the same tolerance and fundamental rights as polytheisms. But because they’re different, you can’t expect their features to be equally valid in a polytheist context. You have to review your thought process, check your often unconscious bias and construct a more apt terminology and framework.

September 14, 2018

Slowly, but surely – always & everywhere.

Anyway, short of a good pendant with an actual depiction of Mercury or Hermes – coin or other – and at a reasonable price, I considered other options. The ideal would be a scallop, because it’s commonly used by pilgrims in Galicia and could therefore easily stand for wayfaring, the Lares Viales and the Iberian aspect of Mercury. But again, the options available online are either disappointing or expensive and the best place to find them in abundance and at a good price is Santiago de Compostela. Ironically, I lived there for four months back in 2010 and what scallops I bought at that time I give them away as gifts, ignoring their mercurial value. Which is understandable, since Mercury only stepped into my life after I came back from Santiago, in what was the start of the ways-and-Lares-Viales-focused path that I’m currently on. So I’m going to wait for things to come full circle and one day return to Compostela, at which point, in a manner of symbolic milestone, I’ll buy two small silver scallops, one for me and another for Mercury. In the meantime, I opted for a turtle pendant.

[image error]

The pendant – not actually made from turtle!

Obviously, the choice wasn’t random. It’s an animal with a mercurial link by way of the myth of Hermes’ birth and of how He invented the first lyre using a turtle shell. But in the Iberian cult of Mercury that I’m constructing, it’s also an animal representative of the notions of movement and change. Which may seem odd, given that the turtle is far from being the fastest of species, especially on land, but that’s exactly where its symbolic value resides: however slow, however seemingly non-existent, things are constantly moving and change is a permanent part of life. There are no final destinations, just stops and stages in a perpetual journey.

Granted, the turtle from the myth is a tortoise, a fully terrestrial animal, whereas the pendant, as seen in the photo, depicts at best a sea turtle or a terrapin, but that is nonetheless appropriate, since those are the two branches of the species that are native to Portugal. So there’s an Iberian note there, in line with an equally Iberian cult and similarly to what I had in mind with the scallop.

[image error]

The Mauremys leprosa, also known as Spanish, Mediterranean or Moorish terrapin, is a member of the turtle family that’s native to Portugal. Photo by David Germano (source)

Thus, on the final days of August, I bought two pendants, one for me and another for Mercury, and placed them by His image in the domestic shrine dedicated to Him. There they stayed until the first Wednesday of September, at which time I removed them and kept them by the fireplace as I burned the offerings I make to Maia’s Son every month – cinnamon, fennel and wine, together with a candle that’s left burning on the shrine. And then I consecrated the pendants, sprinkling them with cinnamon and adding a portion of dark chocolate as an additional offering to signal the moment.

After the ceremony was over, one of the pendants was returned to the shrine, where it now stands next to god’s image. And the other I’ve been using every since as a symbol of luck, protection, of the perpetuity of movement and change and as a physical expression of a bound with Mercury, with whom I now share a small object.

July 15, 2018

Khosh amadid!

That’s why I was somewhat disgusted when I heard the orange idiot who occupies the White House say, during his visit to the UK, that immigration is changing Europe’s culture, which in the slang of the nativist right is code for the threat of Islam. And I say somewhat, because there’s not much that’s truly surprising in the words of a narcissistic, wilfully ignorant and deeply insecure clown.

As a native Portuguese whose family has been in Portugal for at least four centuries, whose native language has as much as one thousand words of Arab origin, whose native land is marked by numerous Arabic placenames and where bakeries, restaurants or traditional celebrations include various dishes of Arab origin or influence, all of it a product of the Islamic period of Iberian History, I can only classify as ignorant the idea that immigration from the Middle East or north Africa is a threat to European culture. Utter ignorance, raw stupidity, ridiculous fear-mongering. Europe is not monolithic and, when it comes to the southwestern end of the continent, Islamic civilization is one of its cultural matrixes.

[image error]

The Arab room in the Palace of Sintra, once the residence of Moorish rulers and later of Portuguese royalty (source)

But that was also why, last week, I happily accompanied through the media the visit to Portugal of Aga Khan IV, spiritual leader of the Naziri Ismaili Muslims, who was received with State honours by the President and Prime-Minister and, starting from the middle of next year, will have an official residence in Lisbon, where the world headquarters of the Ismaili Imamat will be located. At a time when many call for an imaginary cultural purity, close themselves up in a siege mentality or strive to deny layers of European culture, it’s good to know that my country, despite all its problems, manages to remain open to the Islamic world, to which it owes a part of its national identity.

Welcome, Imam!

[image error]

July 6, 2018

Peregrinalia – hitting the road

Connected dates

There are two modern celebrations of mine to Mercury that I’ve mentioned several times before and both have been incorporated by other polytheists into their festive calendars. They are Vialia on January 4th and the anniversary of Maia’s Son on April 4th, the former focused on Mercury’s divine host and the latter on his birth.

Both have an individual sense, with Vialia addressing the opening of ways at the start of a new year, while the birthday of the god evokes his connection to the number four and thus takes place on the fourth day of the fourth month. But there’s also a continuum between them and it connects to two other modern festivities, the third of which is Peregrinalia on July 4th.

Essentially, it flows as follows: in January, the opening of the ways amounts also to a preparation for the birth of Mercury, who’s destined to become Lord of Pathways and hence of the Lares Viales. Trails and roads are thus cleared and made ready and, after the coming of the god, the next stage in the festive cycle are the journeys in which he encounters other deities and acquires an awareness of the world. Following that is the perception of the constant flux and finite nature of things, which then links up with the end of the year and the Lares Viales again, though that’s a subject for another time. In short: the ways, the Lord of Ways, the use of pathways and the perpetual destination.

[image error]

A forest trail in Sintra, Portugal (credit)