Kristine H. Harper's Blog

September 3, 2025

Decolonizing Fashion

A vital part of the practice of rewilding fashion is to embrace local knowledge, and empower marginalized communities. Central is the departure from the exploitative, hegemonic systems that tend to dominate the fashion industry. By fostering an environment where local traditions, craft practices, and materials flourish organically, fashion can move beyond the homogenization imposed by globalized, top-down systems.

This shift is a crucial step towards decolonizing fashion, as it offers an approach that allows for indigenous communities and artisans to reclaim their autonomy, elevating their cultural practices in ways that resonate with sustainability, equity, and the potential for transformation.

Fashion shouldn’t be a product to be consumed, but a living practice rooted in culture and environment!

Naturally dyed yarn, Nisa Penida, Indonesia.

Naturally dyed yarn, Nisa Penida, Indonesia.Rewilding in fashion aligns with decolonial thought by rejecting the notion that indigenous cultures and practices should remain static or are in need of preservation. Drawing from the theories of the previously mentioned book Feral by British biologist and activist George Monbiot, rewilding emphasizes that preservation can sometimes be destructive, stifling the flow of what should naturally evolve.

Rewilding supports development while maintaining ecological balance.

When applied to cultural sustainability, particularly in relation to fashion and garment-creation, this involves respecting the region’s resources, competences, and traditions. However (and importantly!), respect is not the same as preservation. Traditions should not be frozen in time; rather, they should be allowed to flow and evolve, with deep respect for past insights and wisdom. As the saying goes: you cannot step into the same river twice. Everything is always in flux.

There is a somewhat colonial thought in wanting traditional crafts to stay the same — an “Oh, we find it so interesting, so beautiful, and we want it left unchanged so that we can study it and admire it,” as if looking at ancient artifacts behind museum glass.

But living traditions are not meant to be static. To rewild craft traditions is to open them up so that time can flow through them naturally. It means creating the right circumstances for them to develop with integrity and relevance, because static is never natural.

Traditionally handwoven textile pattern Nusa Penida, Indonesia.

Traditionally handwoven textile pattern Nusa Penida, Indonesia.Empowering artisans through the revival and innovation of traditional practices can open up creative avenues within communities. For instance, teaching weavers how to dye with food waste or explore bacterial dyeing, offers a way to reconnect with local, sustainable materials while fostering creativity. Instead of ready-made fixes, this approach builds capacity: artisans rediscover and reinvent techniques, keeping agency over their craft. As the proverb goes, “Give someone a fish and they’ll eat today; teach them to fish and they’ll eat for a lifetime.”

As fashion becomes more globalized, with production methods and designs homogenized across continents, decolonial practices in fashion grow ever more urgent. These practices challenge the commodification of indigenous cultures and the extraction of cultural capital by outside forces. Instead of being absorbed into globalized trends that erase their histories and identities, marginalized communities can reclaim their cultural narratives through fashion.

The rewilding process helps to center the voices and values of indigenous communities, allowing them to define their own aesthetic futures, not through the lens of colonialism, but as expressions of vitality, creativity, and sustainability.

The rewilding approach to fashion also emphasizes tactile beauty. The tactile experience of materials, the embodied relationship with objects, and the slow, intentional creation of garments can offer a profound means of cultural nourishment. Fashion is not just a visual or consumable object but an experiential, multi-sensory journey. By embracing materials and techniques that honor cultural and environmental connections, fashion can offer aesthetic nourishment of the wearer’s senses, body, and spirit, all while giving the wearer the opportunity to engage with the deeper cultural narratives that these materials represent.

Weaver in Nusa Penida (Indonesia) showing me one of her beautiful handwoven pieces.

Weaver in Nusa Penida (Indonesia) showing me one of her beautiful handwoven pieces.This shift in fashion is supported by the principle of reciprocity found in e.g. the beautiful book Braiding Sweetgrass, in which American botanist Robin Wall Kimmerer speaks of the relationship between humans and the earth — an exchange in which we should give as much as we take. Rewilding fashion, like rewilding in nature, asks for a relationship with materials and processes that respects the land and communities.

Instead of exploiting natural resources, we can return care and intention to them. And by doing so, fashion is not just a passive process of consumption, but one that is in active dialogue with the earth, allowing both the land and its people to thrive.

Rewilding also offers a framework to challenge the inequalities deeply embedded in the fashion industry — particularly the exploitative labor practices and the extraction of cultural capital from indigenous communities. The colonial structures that have dominated fashion for centuries are built on these inequalities, but the process of rewilding can provide a counterforce: a way to honor and uplift indigenous knowledge and practices in a contemporary context. The opportunities for empowerment are created not by isolating these practices or keeping them in a romanticized past, but by allowing them to evolve, grow, and transform in line with global needs for sustainability and cultural equity.

The practical and philosophical side of rewilding concerns ensuring that what we produce is rooted in a deep respect for the environment, the culture, and the people who create it. This contrasts sharply with the linear, exploitative systems of the dominant fashion industry, which prioritize profit over cultural significance, sustainability, and ethical practices.

The integration of rewilding and decolonial thought into fashion challenges the colonial legacies of cultural appropriation and exploitation. It offers an alternative vision — one where cultural practices, ecological knowledge, and community empowerment are central to the design process. Rewilding fashion moves beyond simply reinterpreting indigenous practices; it creates the space for these practices to evolve into something meaningful for today’s world, without losing their connection to tradition and cultural wisdom.

When rewilding fashion is seen through both aesthetic and ethical lenses, it opens a path toward sustainability, resilience, and deeper meaning. This vision goes beyond mere adornment; it invites everyone who engages with it to actively participate, preserve, and transform.

July 31, 2025

Rewilded Fashion

You don’t force a river to flow—you restore the landscape so it can find its course.

I listen to myself talk a lot about rewilding lately. Maybe too much. Probably too much actually (I see those eyes gaze at time). But I have fallen deeply in love with the concept of rewilding.

In this article I will discuss the benefit of rewilding fashion. Not too look wild or trendy or anything like that, but to massage away the tension between preservation and innovation (so to speak). This is the first of a small series of articles. I hope you will enjoy.

I have been working for some years now on crafts preservation in Indonesia. This has made me aware of an array of obstacles and humbled me to the reality that preserving traditional crafts is not simply a matter of storytelling, financial support, or boosting sales.

When examining traditional practices and materials, the ethics of using cultural heritage in contemporary design become critical. Often, these practices are intertwined with the desire to preserve and protect them from extinction, but this approach can inadvertently lead to the stagnation of the very creativity they were meant to nurture, and at times even to exploitation. In contrast, rewilding offers an alternative framework—one that embraces evolution and natural growth, while resisting the urge to freeze cultural traditions in time.

Rewilding is a concept known from ecological practices and the regeneration of fauna and flora. Rewilding nature is however not the same as restoration (!); it involves creating ideal conditions and then stepping back to let nature adapt and shape itself in free, often unexpected ways. Perhaps rewilded nature won’t resemble the landscapes we know; it may not take the form of a rainforest or a savannah. Instead, it might give rise to new ecosystems and bio-communities that sustain plants and animals in ways we cannot yet imagine. This rewilded nature may function in ways that promote the emergence of new life forms and celebrate diversity by merging different plant species. Restoration, on the other hand, is focused on reconstructing what has been lost due to decay, exploitation, climate change, pollution, or other negative influences.

Me and my tiny cat Rumble when I first started my vegetable garden in Bali not having a clue about tropical gardening. Rewilding in practice!

Me and my tiny cat Rumble when I first started my vegetable garden in Bali not having a clue about tropical gardening. Rewilding in practice!The concept of rewilding can be “translated” to fashion theory and practices as a process of rejuvenation rather than preservation. British ecologist George Monbiot stresses (in his very recommendable book Feral) that rewilding is the equivalent of halting progress or idealizing the past, but that it involves creating the conditions for natural systems to unfold. Rewilding hence invites us to embrace both novelty and tradition, recognizing life as an ever-flowing, dynamic force that exists in cycles ensuring stability and durability.

Whether we are discussing nature or fashion, the process of rewilding is an ode to development. It does not romanticize the past or advocate for stagnation; rather, rewilding celebrates rawness, the beauty of imperfection, and the vibrant rhythms of diverse, flourishing life.

It is therefore important to emphasize that the process of rewilding is not the same as rewinding, and in the context of cultural sustainability and sustainable fashion, the aim should never be to return to an idealized past or “preserve” cultural practices as static traditions. Instead, rewilding offers a chance for these traditions to evolve naturally. This mindset fosters innovation while maintaining the essence of traditional craft, allowing it to continue to develop as a living, breathing practice. Just as environmental rewilding works to restore ecosystems by encouraging natural processes to take their course, rewilding in fashion allows materials, techniques, and cultural elements to develop organically, free from the constraints of preservationist thinking.

Rewilding fashion requires designers to initiate the aesthetic experience but then step back, allowing garments to evolve through use. Rather than reverting to past methods, organic growth is embraced, which can lead to using materials and techniques that evolve naturally with time and minimal intervention.

The most sustainable design object is raw, changeable, and unfinished. This may seem counterintuitive, as sustainability is often linked to durability, completeness, and strength. Yet, I argue that true sustainability lies in flexibility and openness to change. Polished, rigid objects tend to lose appeal over time as wear and tear diminish their value. They peak at completion and decline from there, resistant to change and detached from human connection. Marks and stains signal decay rather than character. This, of course, is not very sustainable.

So, why not create objects that evolve, grow more intriguing, and become more beautiful through use? Why not integrate the user experience into the design process, allowing the object to reach its full expression over time? Could this approach foster a deeper connection with materials and encourage a rewilded, aesthetically nourishing relationship with fashion—one that values transformation rather than perfection?

Opening up a fashion piece naturally aligns with the process of rewilding and efforts to sustain endangered craft traditions—such as the textile weaving I research in Indonesia, where my focal areas are Bali, Nusa Penida, Lombok, and Sumba. These regions are home to intricate weaving traditions like ikat, rang rang, cepuk, songket, saudan, and endek, woven on both large looms and narrow backstrap looms in villages across the archipelago.

With time, I have come to understand that a core aspect of rewilding fashion is recognizing that traditional practices—such as weaving, dyeing, and garment-making—have never been static!

Sustainable fashion often emphasizes the preservation of endangered craft traditions, but a rewilding perspective shifts the focus toward creating the right conditions for artisans to thrive. Rather than simply restoring patterns or techniques, the practice of rewilding ensures that craftsmanship remains dynamic by supporting fair wages, access to high-quality materials, and the time needed to refine and innovate techniques. When artisans are empowered in this way, tradition does not merely survive—it evolves and thrives, allowing cultural heritage to remain a living, breathing force rather than a fixed representation of the past.

Weaver in the island of Nusa Penida

Weaver in the island of Nusa PenidaRewilding, in this sense, nurtures a fluid relationship between tradition and modernity—one where cultural knowledge is not preserved as a relic but continuously adapts to contemporary needs and opportunities. True sustainability in craft does not just mean safeguarding techniques; it involves sustaining the artisans themselves. By fostering conditions that encourage innovation, experimentation, and long-term resilience, rewilding ensures that these traditions remain relevant, evolving organically rather than being confined to the past.

Sustaining endangered craft traditions requires a delicate balance between preservation and evolution. The core of a craft—the hands-on wisdom, intricate techniques, and tactile qualities of traditional textiles—holds immense cultural and aesthetic significance. Yet, this very strength can become an Achilles’ heel when rigid adherence to historical forms prevents adaptation. Traditional motifs, patterns, and textures carry deep symbolic meaning, often tied to specific ceremonies, social status, or life phases. While artisans are trained to replicate these with precision, cultural shifts can render original functions and aesthetics less relevant beyond their immediate communities. In many cases, labor-intensive techniques struggle to compete in a world that prioritizes efficiency over artistry, leaving artisans unable to sustain themselves financially.

This is where fashion can become a vital force in the ethical renewal and revitalization of traditional crafts. Rewilding fashion offers a way forward—one that nurtures artisanal practices while ensuring their relevance in a changing world. Just as ecosystems adapt to shifting conditions, crafts can evolve without losing their essence. The key lies in identifying the core elements that define a craft—its materials, techniques, and creative energy—and allowing these to inform contemporary expressions.

This approach fosters a dynamic relationship between past and present, keeping craftsmanship alive not as a static relic but as a living, breathing practice embedded in both culture and nature.

April 10, 2025

Rewilded Design

My fascination with rewilding began when I first read the previously mentioned book Feral by George Monbiot, where the concept is deeply rooted in ecological restoration—allowing nature to evolve freely, without human-imposed constraints. Over time, I have come to see rewilding as a principle that extends far beyond ecology. It has become a guiding force in my research, my creative work, and my daily existence. Rewilding means stepping away from rigid structures and reclaiming the fluidity of natural rhythms. It is at times an act of unlearning, of shedding the cultural conditioning that tames and constraints, allowing intuition and curiosity to lead the way.

Wearable Art, rewilded by Southeast Saga

Wearable Art, rewilded by Southeast SagaIn my research on rewilded product design and aesthetics, I have come to the realization that creating rewilded design objects requires a release of control. Just as rewilding in nature involves creating favorable conditions and then stepping back to let ecosystems take over, rewilding in design means moving away from objects that are rigidly finished at the point of creation. Instead of producing objects that degrade the moment they leave the designer’s hands, we should be designing things that evolve and mature—things that grow more beautiful with use, wear, and time.

Rewilded design objects should be designed with the potential for transformation embedded within them: their “final” expression never truly being final but unfolding through interaction, iterations, aging, and adaptation. I imagine the aesthetic of the rewilded design object being a celebration of the passage of time, of wear caused by frequent (loving) use, and of the maturing, raw, and imperfect. Surrendering to the material and letting it take the lead could, aligned herewith, be a way of working with rewilding as a part of the design process. A rewilded object, like a rewilded landscape, carries the traces of the creation time and is open to the imprint of use and the story of its existence.

I have previously, on the blog and in my books, written extensively about the oddity of fully completing a design object before it is ever used. If an object is meant to be lived with—to be used, worn, touched, interacted with—why make it so “picture perfect” that any trace of use diminishes its value? Why design impeccably sleek chairs that lose their allure at the first scratch, or pristine garments that become flawed with the stain or the first loose thread? Such objects are closed—sealed off from the possibility of flexibility and development, unable to form a lasting bond with their users. Closed, smooth design objects begin a slow decline the very moment they are put to use, moving toward inevitable rejection.

But imagine for a second if decay and user traces weren’t seen as damage but as transformation, a natural part of an object’s lifecycle?

Reborn Kimono by Southeast Saga

Reborn Kimono by Southeast SagaAligned with ecological rewilding, rewilding design objects requires relinquishing a degree of control. Of course, a designer should have intentions and infuse objects with thoughtful aesthetics and storytelling. But instead of dictating a fixed, final form, the truly sustainable designer should allow space for evolution; work it into the object from the start. This could be a way of welcoming the marks of use, the patina of time, and the individual imprint of the user.

Designing with openness and creating objects that are raw, adaptable, and receptive to change and usage is a way of welcoming a new kind of beauty. A beauty that does not rely on smoothness or perfection but finds its depth in wear, in texture, in imperfection. The aesthetics of the rewilded design-object celebrate diversity, decay, and the richness of lived experience—offering a much-needed alternative to the sterile, disposable culture of mass consumption.

March 13, 2025

Rewilding Comsumption

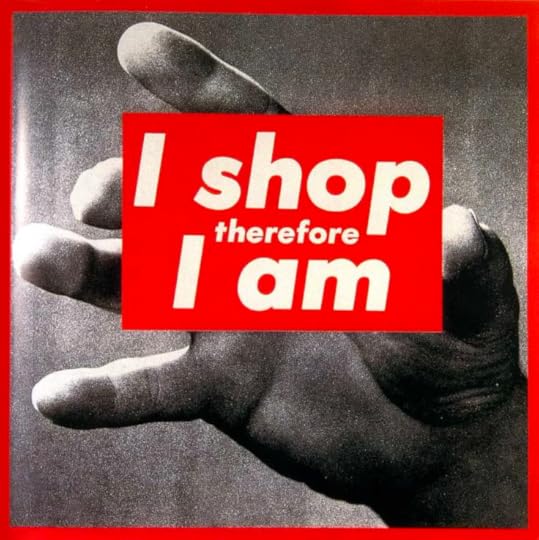

I clearly remember the first time I saw Barbara Kruger’s iconic photolithograph, I shop therefore I am (1990). As a rewriting of French philosopher René Descartes’ (1596-1650) seminal statement, I think therefore I am (Cogito ergo sum), it is a powerful and symptomatic reflection of modern consumerism.

We are first and foremost consumers. Consumption has become our primary mode of engagement, our expression of identity, our means of belonging. We hoard glittering things like magpies, collecting and displaying them as proof of status, taste, or trend awareness. Consumption has long since outgrown its roots in necessity; it has become our source of entertainment, self-expression, and even our primary form of interaction with the world. Even the most basic acts of survival—eating, drinking, sleeping—have been reshaped into lifestyle choices, marketed as extensions of personal identity. What we consume, when we consume, and even the decision to abstain from consuming something have become statements, signaling status, identity, or awareness. Even rest is now a commodity, with sleep trackers and silent retreats turning fundamental human needs into aspirational goals.

This all raises an unsettling question: if modern identity is built around consumption, who are we without it?

Refraining from purchasing fast fashion has itself over the past years become a cultivated choice—one that assumes the privilege of already having enough. It’s a quiet luxury, out of reach for those who buy clothes simply because they have to cover their bodies, not because they’re making a statement. And that’s the problem. Sustainability has become an exclusive club, reserved for the privileged few, who can afford to step away from overconsumption. But if sustainable living isn’t realistic for the majority, then what’s the point? If it’s not for the many, does it even make a difference? For a lot of us, shopping isn’t just about getting what we need—it’s a way to feel included and to have a sense of power and relevance. If we ignore that, we’re missing the bigger picture of why overconsumption happens in the first place, making it even harder to address.

Shopping sure is a potent drug. It promises hope, a feeling of abundance, novelty, and often provides a boost of confidence; and not only because of the approving gazes that might follow new belongings. The pandemic made that painfully clear. Even when our world shrank to four walls, online shopping soared—not for books, mind you; no, for fast fashion and tech gadgets, even though there was no one to show these things to! The act of acquiring became a form of interaction, a way to affirm our existence. What does this reveal about our consumption patterns? If we’re not consuming to be well-dressed for work or to impress our peers, then the acquisition of new, fashionable, tech-trendy, glittery things has become essential to our personal well-being. This reminds me of a sign I often see in a shop in Ubud that reads: “Shopping is cheaper than therapy.” I find that sign so depressing.

We need an alternative to consumerism—an anti-consumerist manifesto that can attract a following and infuse our late-modern lives with meaning and direction. And we need it urgently.

Why?

Well, because overconsumption is a ticking time bomb, an ecological disaster in motion. I’m not one for doomsday scenarios, but the overconsumption of insignificant, unsustainable, short-lived items wrapped in cheap plastic—meant to be discarded after use but never really disappearing—is one of the primary culprits of pollution. I witness this daily here in Bali. There is trash everywhere! Piles of plastic waste line the ditches, dirty brown rivers choked with plastic flow down the mountains during the rainy season, and heaps of flip-flops, toothbrushes, ice cream wrappers, shampoo bottles, and polyester shirts wash ashore, transforming the beaches into colorful patches of disaster. Discarded clothing from around the world accumulates in landfills, slowly releasing clouds of methane into the environment, and the same applies to hard plastic waste from computers, washing machines, and televisions.

Digging into the soil recently on my own little piece of land here (with the intention of making a vegetable garden), I discovered generations of plastic, preserved in layers like the remnants of a lost civilization. With virtually no waste management infrastructure in Bali, most people simply discard their trash in nature or burn it in sticky bonfires along the roads. And when a piece of land, like ours did before we leased it, sits uninhabited for a time—often occurring next to a village—it tends to become the local dump.

One might argue that this is only true in developing countries like Indonesia, and that in wealthier countries the situation is different: that waste is primarily recycled, repurposed as fuel, or transformed into a resource. But while this may hold some truth, I would like to emphasize two key points: 1. A significant portion of the waste that ends up in large landfills here in Indonesia is shipped from Europe, America, or Australia—this, as a subtle side note, represents a modern form of colonialism. While exporting waste may alleviate the consumption problem in developed countries, it exacerbates global inequality. Moreover, just because waste is out of sight doesn’t mean it’s gone. We inhabit a globe with interconnected continents and oceans, making the pollution generated by these landfills a concern for everyone! This leads to my second point: 2. Even though the worldwide waste problem may not be immediately visible in developed countries—and one may not experience the discovery of decades of plastic waste layered in the soil as I did here—there is no recycling system or process for turning waste into a resource that can keep pace with the staggering amounts of waste produced each year. Last time I checked, the figure was an astounding 2.12 billion tons of waste annually! If all that waste were loaded onto trucks, they would circle the globe 24 times.

So, while the mental image of my plastic-polluted backyard might be appalling, the layers of pollution I encounter in our garden and in our small village—plastic bottles littering the roadside, sweet wrappers scattered in the fields, diapers floating down the river—pale in comparison to the mountains of waste generated by a similarly sized European village. The primary difference lies in visibility (and, trust me, it isn’t pretty).

This is not just an environmental crisis; it is a crisis of being. To overconsume is to deplete and erode. It stands in direct opposition to sustainability, which requires slowness, repair, longevity. The churn of endless production and disposal is not just exhausting our ecosystems—it is reshaping our very understanding of value, turning disposability into a default mode of existence. If consumption defines our rhythm of life, what happens when we stop?

Upcycled kimono from Southeast Saga

Upcycled kimono from Southeast SagaRewilding might offer a (positive) answer to this question. To rewild consumption is to break free from the cultivated, modern insatiable need for more. It is to reject the idea that our worth is measured by what we acquire and instead embrace a different kind of abundance—one rooted in resilience, self-sufficiency, and deep connection. It means choosing quality over quantity, mending instead of discarding, seeking nourishment rather than novelty. It is a shift from a mindset of extraction to one of reciprocity, where what we take, we give back, and where value is measured not by accumulation but by the richness of our relationships with the world around us.

I view shopping addiction as a symptom of aesthetic starvation. When our senses are dulled by smooth and monotonous surroundings and things, we tend to overindulge in new, shiny, glittery knickknacks to fill an aesthetic void we may not even recognize. We become aesthetically malnourished, seeking empty calories to satisfy us.

As cultural anthropologist Grant McCracken observes in his recent, very recommendable book The Rise of the Artisan, a shift away from empty overconsumption is already underway—driven, in part, by an aesthetic malnutrition caused by an excess of smooth, mass-produced sameness. For decades, globalization and industrialization have pushed the world toward homogeneity, erasing cultural distinctions in favor of efficiency and standardization. Cities now look alike, their restaurants serving near-identical menus. Crafts traditions have been undermined by the flood of cheap, machine-made products.

But the hangover from this relentless uniformity is beginning to show.

As with all cultural tendencies, an excess of one thing tends to spark a longing for its opposite. The more convenience, sameness, and artificial smoothness we consume, the more we crave tactility, slowness, and variation. Increasingly, status is no longer signaled by accumulation or excess but by engagement with the handmade, the seasonal, the imperfect. The rise of the artisan reflects a deeper yearning—not for more, but for meaning.

The key to breaking the addictive cycle of overconsumption lies in changing our status symbols (easier said than done, of course, but definitely not impossible). If engaging in sourdough bread-making, growing tomatoes, reading novels, cherishing handmade products, or listening to lengthy podcasts is suddenly viewed as more status-enhancing than purchasing smartphones, scrolling on TikTok, or flaunting expensive designer clothing, the necessary radical reduction in product consumption will naturally follow.

But for this transition to take hold, it must extend beyond aesthetics into a fundamental rethinking of value. If we rewild our desires—redirecting them from passive consumption toward active creation, from disposability toward longevity—the need for endless production will naturally diminish.

A rewilded relationship with material things does not have to mean deprivation; it can actually be rather liberating! When we cease to chase the latest trends, we free ourselves from always having to keep track (yes there is a deliberating degree of JOMO, the joy of missing out, to trace here). When we let wear and tear tell a story of use rather than obsolescence, we redefine beauty. When we resist the pressure to accumulate, we make space for presence, almost quite physically actually.

Surround yourself with tactilely stimulating, visually exhilarating objects. Fill your home with (few but good, well-made) things you want to engage with repeatedly—objects to touch, wear, observe, sit on, drink from, and “share time” with. Feed your senses! Keep them alive and alert. In doing so, your need to purchase insignificant knickknacks will vanish. It’s a promise.

Perhaps this kind of shift in our view on value and abundance is the true marker of late-modern rebellion—not consuming less as a curated lifestyle choice, but stepping entirely outside the paradigm of consumer-driven identity. To rewild consumption is to reclaim our agency. And in doing so, we may rediscover a life enriched by depth, durability, and aesthetic nourishment.

January 21, 2025

Why Holding Onto Craft Traditions Might Be Killing Them

(a tale of my, somewhat depressing, journey working with endangered crafts in Indonesia)

After two or three months of regular visits to the weavers, it felt as if I was the only one who found it important to preserve the patterns and dyeing techniques that defined weaving on the small island that served as my research area.

The island was ravaged by water shortages following a prolonged drought, making it nearly impossible to dye textiles with the wild plants that the weavers typically used. Almost all the plants had withered, leaving the island brown and dry. I sailed over once a week and rode a rented motorbike through the parched mountainous landscape, where the air was so dry and warm it reminded me of a sauna, until I reached the weaving village I was writing about.

My focus in the article was on ‘women’s empowerment,’ as textile weaving was traditionally a female craft. Initially, I approached the task with a bold and uplifting sense of fighting for women’s rights, which, I must admit, inflated my ego quite a bit.

However, during my numerous visits to the island, both my enthusiasm and my ego became nearly as dried up as the dye plants. The women appeared indifferent to my mission — some quite openly so — and they seemed to use the drought as a reason to embrace synthetic colors, which required far less water than developing plant-based dyes from scratch. Given that most of the plants had also perished due to the drought, it was a no-brainer to seek alternative solutions. Furthermore, they all seemed to agree that the vibrant synthetic colors were far more beautiful than the muted hues of plant dyes.

“But the waste dye you pour into the ground is extremely polluting,” I piped up cautiously during what would become my last visit with the weavers.

One of the oldest weavers, a beautiful tall woman of about 65 with an impressive mane of jet-black hair, loosely rolled into a bun, dressed in a long indigo colored handwoven skirt and smoking a curved wooden pipe, looked at me with a condescending expression and said in her deep voice, “With all due respect for what you’re trying to do for us, you shouldn’t talk to us about pollution. I’ve seen pictures of all the clothing that gets thrown away in countries like yours and ends up in large, steaming piles in places like ours. Compared to that, our pollution is minimal, and I know you understand that.”

I could feel my cheeks burning.

“But what about aesthetics?” I piped up again.

“What do you mean? The new colors are much prettier than the old ones,” laughed one of the middle-aged weavers as she pulled out a sarong in a bright red and pink pattern. “Just look at this! It’s something entirely different from that!” She pointed to a wooden stand where two handwoven pieces of fabric in a jagged pattern hung, colored in dusty light brown, pale yellow, and soft pink.

I knew that the delicate colors were the result of a painstaking process involving the development of dye powders made from coconut shells, mango leaves, and avocado pits.

The patterns woven by the women had grown less intricate over the years, highlighting the distinction between their new creations, the slightly older ones, and the very old textiles passed down from their mothers and grandmothers. There was a noticeable and gradual dissolution of complexity, a smoothing out of designs. The very old textiles must have taken months to create, showcasing a sublime mix of zigzagged lines, wavy shapes, and figures.

In contrast, the new pieces, which lacked any recognizable figures and consisted only of jagged lines or simple lines — never both — probably took just a couple of weeks to complete.

In keeping with the capitalist spirit that even the women in this remote village faced, everything had to be measured in terms of profit and loss. Whether something was worth pursuing depended on how much one could earn from it. Spending several months creating a single piece of fabric simply couldn’t be justified when the financial rewards were so limited, especially when competing with machine-made textiles that, to the untrained eye, looked indistinguishable from handmade ones. This reality was unyielding and incredibly difficult to counter.

The tsunami of uniformity brought about by globalization was so overwhelming that it had nearly eradicated the diversity of local expressions, along with the irregular, jagged, and raw beauty that accompanied them. I understood this well, yet during the months I spent visiting the women, I endeavored to plant that seed of truth and advocate for my cause, which could be largely summarized as follows: by raising awareness of the treasure trove of jagged, nourishing beauty and cultural diversity inherent in traditional craftsmanship, many would awaken to the importance of supporting, investing in, and preserving local craft traditions.

I convinced myself I was fighting this cause for the sake of the weavers.

However, the young women were leaving the village — they preferred working in hotels along the coast or in bars and restaurants on the main island. It seemed far more glamorous and exciting than sitting in a remote village with a bunch of snot-nosed kids clinging to their skirts while weaving day in and day out. Submitting to the painstaking, slow process. In small, far too warm rooms with poor lighting. With limited earning opportunities. Without a strong community. And without comforting, affirming glances.

I believe the death knell came when one of the few younger weavers, a pretty, round-faced woman of about 25 who had three small children and lived in a small wooden house without running water, looked up from her phone, which she and her three kids had their eyes glued to almost constantly (perhaps because everything pouring in from the big world through that small screen seemed more interesting than life in the village), and said with an indifferent expression: “No one reads anymore, so I can’t really see how your article is going to help us.”

She was absolutely right! No one cared to read more than the few lines that accompanied a social media post — and even that was stretching it. If I wanted to reach a broad audience with my message about dying craft traditions, I would need a completely different approach — preferably a flashy one in the form of short entertaining videos with music or sound effects. Maybe even spiced up with a few special effects. And that was far beyond both my abilities and my willingness.

Moreover, my “here I come to save you” attitude left an increasingly bitter taste in my mouth. There was something almost colonizing or missionary-like about it that I couldn’t bear to think about without feeling nauseous.

Ugh.

As I drove away from the village that afternoon, I knew I wouldn’t continue working on the project. I realized the women’s skepticism was justified, and what I was up against here was so extensive that my awareness campaign in the form of an article in a relatively insignificant academic journal wouldn’t even create small ripples in the water.

I would finish my article and receive my fee (for I, too, was part of the capitalist age), and then I would abandon my arrogant mission to uphold traditional weaving.

“Yes, that must be it,” I thought as I drove through the parched landscape with the wind in my hair and the dry, sauna-like air in my nostrils.

And then it started to rain.

It felt as if the rain was giving up too, releasing its life-giving drops with a resigned, or perhaps rather a relieved, sigh. The drops were heavy and large. When they hit the warm asphalt, I could almost hear them sizzle. Tsssss, tssss.

Had the rain held onto its water to emphasize something or punish someone? To punish me? No, how egocentric could one be?! I scoffed at myself.

But as I continued driving, I couldn’t shake the feeling of resignation reflected in the raindrops, oddly mirroring my state of mind. It truly felt as if the rain sighed with relief when I finally surrendered, allowing it to follow its most natural impulse — to trickle, flow, and stream.

The drops quickly transformed into a downpour that drenched me within minutes, as if the rain were conveying a message I already understood. Namely, that if you try to prevent the changes that occur around you, whether subtly like the babbling of a brook or loudly like the crashing of waves, you will ultimately be the loser. Believing that salvation can only be found in what once was, elevating the past to a pedestal of truth, light, beauty, and goodness, is as unnatural as attempting to stop water from flowing.

Why impose guilt on the weavers for simplifying, optimizing, and developing their craft in a way that perhaps contained the seeds of its destruction but was simultaneously the only way forward in the specific situation they found themselves in? The dissolution was inevitable. It had to happen.

Perhaps something was being lost when the weavers simplified their traditional patterns and substituted natural dyes with synthetic textile colors to increase their earning potential. And undoubtedly, transforming their traditional craft into a business would lead to its demise.

But perhaps that was exactly what needed to happen for something new to emerge — something new that might be based on passion and the urge to create. New forms of craftsmanship might arise. And perhaps they would lay the foundation for new forms of collaborative work, the emergence of new materials, new ways to create with their hands, new methods, new patterns and color combinations, new rituals, and new traditions.

The only constant is change, as a wise man said thousands of years ago. How could I have forgotten that?

December 15, 2024

The Power (and beauty) of open design

Everything in our world is in constant flux — our inner feelings, moods, and sensations, as well as the outer world: seasons, weather, physical environments, and even political, economic, and societal circumstances.

So why design objects that stagnate?

Why create static items intended for only one use, one look, and one ambiance?

When an object is designed to be “picture-perfect” and fixed at the time of release, its trajectory becomes inherently linear — each trace of use pulling it further from its original perfection. This linear path leads toward obsolescence, as every scratch or mark is seen as a flaw, signaling rejection.

In contrast, the resilient design-object embraces openness. It is created to adapt to the user, to integrate with their routines, and to become more “right” the more it is used.

Open design-objects are flexible, unfinished at the time of release, and designed to evolve over time. Like the copper roofs of my former hometown of Copenhagen that develop their verdigris patina with exposure to the elements, these objects are intended to transform and gain character through use and weathering.

Their “final” appearance is not predetermined but shaped by randomness — telling a story of their journey and interaction with their user.

The open design-object invites interaction and transformation. It may allow the user to alter, or complete it, adapt to changing needs or physical forms, or accommodate shared use within a community.

Flexibility is key, enabling these objects to evolve alongside their owners’ lifestyles and circumstances. This is particularly relevant in the context of a nomadic lifestyle, which demands minimalism and multifunctionality.

Nomadic living, traditionally associated with indigenous tribes, involved moving when resources became scarce, weather turned harsh, or the tribe faced threats.

Today, nomadism has taken on a new form: the digital nomad. Enabled by remote work and connected by shared values, digital nomads represent a modern tribe, unbound by permanent homes or workplaces. For the new nomads, owning a large number of belongings is neither practical nor sustainable. The objects they do own must perform in multiple ways.

Clothing is often a digital nomad’s most significant possession beyond a laptop. However, clothing presents unique challenges. Practical needs vary across climates and seasons, and wearers quickly tire of wearing the same styles repeatedly. Additionally, garments wear out, requiring frequent replacements.

One way to combat the unsustainability of perceived obsolescence — when an item feels outdated despite being functional — is to design garments for sharing or co-ownership.

Within a digital nomad tribe, shared ownership could create a sustainable flow of new looks, reducing waste and encouraging community engagement. This concept can extend beyond clothing to include practical items such as kitchenware, electronics, and even decorative objects, forming a portable “survival kit” of shared essentials.

For shared garments to work, they must be adaptable to different body shapes, durable, and aesthetically nourishing for a diverse group of users. Minimalistic or subtle designs can serve as starting points, allowing wearers to personalize the garments over time. Each user could leave their mark — through repairs, embroidery, or subtle alterations — turning the garment into a living canvas of shared creativity and history.

These marks could include names on an inner lining, personalized decorations, or functional modifications. The design must guide the personalization process, creating a framework that balances structure with freedom, allowing for random, organic contributions to flourish. Such garments become stories in themselves, chronicling the lives and creativity of their users.

The resilient, sharable design-object embodies a way of overcoming the cycle of perceived obsolescence. By celebrating usage, diversity, and inventiveness, these objects remain relevant and meaningful, offering users a sense of connection and significance. Shared ownership fosters camaraderie, while the wear and traces of use imbue each object with tactile nourishment and stories of belonging.

This approach transforms the act of shedding old belongings into a sustainable practice, enabling users to feel at home wherever they are, through the tangible evidence of their shared narratives. Open, adaptable design encourages us to rethink the way we own and use objects — creating not just tools for living, but vessels for storytelling and connection.

By rejecting static perfection in favor of dynamic evolution, open design offers a pathway to significance, sustainability, and shared creativity. It allows us to embrace flux and unpredictability as intrinsic to the objects we own and the lives we lead.

November 13, 2024

Artfully worn

I’ve been reflecting a lot lately. After years of working with and researching sustainable fashion, I feel ready for a deeper shift—something more significant. What began as a mission to create eco-conscious, beautifully crafted clothing has evolved into something I now think of as wearable art. This idea goes beyond sustainability; it’s about creating pieces that resonate on a soulful level, that feel like stepping into art itself.

When I started Southeast Saga, one of my guiding principles was to never ever challenge the price set by the skilled craftswomen and seamstresses I collaborate with, nor to bargain for the discarded jeans I buy from a large secondhand market here in Bali. Because if I start haggling over the cost of these materials or undervaluing the labor behind them, it goes against everything I stand for.

But I’ve realized that there’s a challenge!

We’ve all become so used to clothes costing next to nothing that this mission can be hard, really hard. Quality, handcrafted textiles and thoughtful design are time-consuming to create—and they should come with a price, perhaps even a high one. Such pieces should be ideally be viewed as an investment, not just a purchase.

I understood that I had two choices: I could start bargaining with the amazing people I work with here—asking the weavers to “optimize,” pressuring my seamstresses to work faster, and cutting down on my own research and design time. Or I could reframe these pieces as wearable art. Art, unlike everyday clothes, is something we expect to invest in. Art is exclusive, carefully crafted, and worthy of a high value. And so are the creations of the artisans I collaborate with.

In my book, Aesthetic Sustainability, I explore the idea that sustainable design should mean more than just eco-friendly materials—it should provide lasting visual and emotional value. Because honestly, what good is “sustainable” if a piece loses its allure in just a few months?

Wearable art takes this idea a step further.

Creating wearable art isn’t just about crafting clothing that respects the environment. It involves creating garments that feel like an extension of the wearer: pieces you reach for time and again because they’re meaningful. Pieces to be cherished, loved, and worn over years, not just for a season. Pieces that are thoroughly designed and crafted, that hold the essence of the time they’re charged with, becoming carriers of time. Pieces that evolve with the wearer, telling stories that deepen and expand over time—becoming more beautiful as they gather presence and meaning, and as they are worn and weathered.

Wearable art can be bold and provocative—a way of dressing that expresses style, attitudes, and opinions. It invites boundaries to be pushed, embodying art in a way that challenges norms and sparks conversation. It’s not only about adorning the body but about making a statement, showing the world who one is and what they stand for through what they wear. For example, what does it mean to be well-dressed? Could it involve repairs, or holes that come from years of loving wear? Carefully curated outfits that break conventions, with unexpected patterns and bold color combinations?

The idea of wearable art makes space for these questions and allows us to redefine style—not as perfection, but as an honest reflection of individuality and life’s aesthetically nourishing imperfections.

This thought has radically reshaped how I think about building a wardrobe—and how I think about creating garments. For me, it’s not just about crafting beautiful clothing; it’s about honoring the incredible skill and dedication of the talented craftswomen I collaborate with. I don’t want to bargain with them or push them to lower their prices! On the contrary, I want to give them more than they ask for and support the development of their craft. Without this, the mission of Southeast Saga loses its heart and meaning.

Investing in garments shouldn’t mean surrendering to fleeting trends or fast fashion. It should feel more like curating a home, selecting pieces with a sense of purpose, and creating a space where true expression lives. Every wardrobe has its essentials—quiet, dependable garments that offer comfort and ease, grounding a personal style. Pieces that provide a steady foundation, fitting seamlessly into daily life without demanding attention. And then, there are the pieces that transcend function, that nourish the soul. These are the wearable art pieces, chosen to elevate, to express something deeply personal. Pieces that transform a wardrobe as a bold painting or sculpture transforms a room—infusing it with spirit, meaning, and life.

A wardrobe isn’t just clothing; it’s a reflection of how we construct our lives. Like a home, it balances the practical and the artful, holding the everyday essentials and the pieces that express who we are. It’s about a harmony—a yin and yang of garments that carry us through daily life and those that tell a story, that make us feel, that communicate our essence.

Creating wearable art is about creating a garments that reflects values, creativity, and self-expression. I like to think of wearable art as a canvas—sometimes a complete expression on its own, but maybe, more radically, it could also be a blank canvas that invites the wearer to shape it, to bring in their own style, attitudes, beliefs, opinions, love.

Wearable art is more than clothing; it’s a bridge between maker and wearer, a shared vision. Or maybe even a collaboration.

Against time we stand defeated

The other morning, I noticed that a large cocoon, which had been stuck to our bathroom wall for some time, was empty; the brand-new butterfly had emerged.

Such are the cycles of nature: flora and fauna change, decay, and perish. The beauty and magic of nature lie in these transformations and in decay. The shifting light of the sky, thunderclouds that drift in to darken everything, rainbows that briefly create colorful streaks above ground, fog that dissipates, and rain that thickens. All heralding the arrival of autumn and remind us of nature’s ebb and flow. The fruit that is at its ripest and most aromatic is often teetering on the brink of rot, while the fragrant scent of hyacinths culminates just before they wither. Leaves decay, turning into soil and nourishment for other plants while bubbling spring buds herald new beginnings.

These are the motifs that inspire still-life and landscape painters alike.

Why?

Because change offers the possibility of seeing and understanding; contrasts and contradictions are prerequisites for insight and wisdom — and within decay lies the seed for something new.

However, decay and perishability are not exactly favored themes in the lives of cultivated modern humans. These aspects of life are often resisted and denied, polished and smoothed over. The prevailing consensus seems to be that the ravages of time are disfiguring.

Yet against time, we ultimately stand defeated. By insisting on immutability and smoothness, we act against one of the most liberating truths: everything is always changing.

The only constant in human life is change. I choose to see this as liberating because it embodies dynamism and vitality. It stands in stark contrast to stagnation and immobility. While there’s nothing inherently wrong with a certain degree of stillness or grounding in one’s life, clinging convulsively to the status quo — believing that everything remaining the same equates to balance and harmony — risks overlooking the freeing beauty of allowing oneself to float along the currents of life, openly and freely. Moreover, it often leads to a disregard for the beauty of the raw and weathered, the enhancing traces of use on beloved objects, and the rhythms of blooming and withering in nature.

Decay is intensely detested by the cultivated modern human being, as it is often linked to aging. Being old seems to be something to be embarrassed about. But being old is not a disease. I feel grateful each year for having survived another cycle on this planet, and for experiencing another year filled with joy, disappointments, hardships, aesthetic pleasures, knowledge, love, friendships, and sensual experiences.

Some of my friends, particularly my female friends, feel embarrassed to talk about their age. I can feel the discomfort myself when asked about it — along with the joy of responses like, “No way! Are you really that old? You don’t look it!” This seems to be the ultimate compliment for women today. It’s as if our value decreases with age — just like trendy, smooth, flashy products lose their allure. Women aren’t allowed to age. It’s a strange situation.

Being a woman over 40, or 50, or even worse, over 60 or 70, is treated as something to be hidden away, smoothed over, or lied about. Only if you appear to defy age — typically through plastic surgery, Botox, or rigorous exercise — can you find some measure of pride in looking youthful.

This phenomenon brings to mind the concept of graywashing, which echoes the idea of greenwashing, where brands make superficial gestures toward inclusivity without addressing the deeper issue. In this case, graywashing occurs when companies use older models with gray hair or wrinkles to create an illusion of embracing aging — while still clinging to a youth-centered beauty standard. It’s like saying, “Aging is acceptable, but only if you don’t really look your age.”

The problem with graywashing is that it doesn’t truly challenge our culture’s obsession with youth. Instead, it reinforces the notion that aging is only admirable if it’s polished, curated, and hidden as much as possible. It’s still about trying to appear youthful rather than genuinely celebrating the natural process of growing older.

True change would mean embracing age for what it is — celebrating wrinkles as marks of experience, seeing gray hair as a sign of wisdom, and valuing people for their depth and insight, not just for how well they can conceal the signs of aging. Graywashing, like greenwashing, is surface-level change. What we really need is a shift in how we perceive beauty and worth, one that honors the richness of life at every stage, without the need to smooth out or hide the passage of time.

Do we really want to live in a world where eternal youth is the norm and where eliminating the natural traces of time is seen as an achievement? There’s nothing more life-denying!

Nothing is more life-denying than fighting against the law of life: everything is on the way, and not in its final form. — Daniel Quinn

This statement from the imfamous eco-author Daniel Quinn’s thought-provoking book The Story of B holds profound wisdom that appears to have been forgotten in the predominant culture of our era.

“Everything is on its way, not in its final form.” This is the law of life. As much as we may view our culture as the most evolved and accomplished in human history, it is, paradoxically, the most stagnant that has ever existed — thus the most life-denying and rigid, the most unsustainable.

Why is that?

Because it goes against the fundamental principles of life: the idea that everything is always evolving and that that is where true beauty lies.

October 6, 2024

Luxury redefined

Today’s luxury is not ostentatious and does not reflect status-driven purchasing power. Instead, luxury is associated with sustainability, the need for value-based communities, and a preference for the imperfect and the human. The new forms of luxury, which will be explored here, also focus on sensibility, slowness, and time.

Luxury in 2024 is interconnected with sensory, tactile experiences. As many of us spend countless hours daily in front of screens and on smartphones or tablets, our need for varied tactile experiences is not being fulfilled. We are, quite simply, tactilely malnourished. And for this very reason, there is an increasing demand for products that, in one way or another, stimulate our sense of touch; for example, handmade products, or products that imitate handcrafted details. Such items are often associated with time. Either with the time it took to make them (and the hands that shaped them) or with the time and traces of use that accumulate in them when they are used.

There is a longing for the imperfect in the need for tactility; for the antithesis of the clean, smooth, and homogeneous. As the Canadian anthropologist Grant McCracken writes in his book Return of the Artisan, in which he elaborates on what he calls “the artisan economy,” which he predicts will (or rather, is already beginning to) challenge and revolutionize the way we develop, produce, and consume things:

“For the artisans, the imperfect has life. Perfection on the other hand, is easy, and that makes it untrustworthy. Perfection is uniform, and that makes it a little tedious.”

The artisan economy represents an economic transformation driven by small, personal businesses. There is a high degree of hands-on and offline engagement in the emerging era of the artisan economy. Furthermore, it is rooted in a return to an old-fashioned local economy, where people shop in small privately-owned stores, know the shopkeepers personally, and focus more on loyalty and community than on getting a good deal or outside influences.

Thus, the artisan economy, in line with the original slow movement, is an antithesis to globalization and large homogeneous chain stores. And it not only presents an antithesis but also a real challenge for the large producers. The fast fashion industry and fast food chains must take the quiet revolution that the artisan economy represents seriously if they want to avoid a real coup d’état. Increased sustainability awareness and a growing need for unique, sensory-stimulating aesthetic products are fueling this already smoldering fire.

And it seems that many of the large chains have begun to recognize this looming threat. This awareness is manifested in their imitation of the artisan economy’s aesthetics; everything from embroidery to patterns that exude the charm of local, near and distant regions, as well as “unique” elements in the form of simulated irregularities (meant to evoke a sense of the handmade) and artificial wear and tear that forcibly adds a touch of vintage and upcycling to mass-produced clothing, demonstrates that the fast fashion industry has noticed that today’s trendsetters are part of the artisan movement.

Me working on imperfect block printing of discarded tent canvas for upcycled rain ponchos for Southeast Saga

Me working on imperfect block printing of discarded tent canvas for upcycled rain ponchos for Southeast SagaIt is still relevant to talk about slow living. Even though the slow movement has been around for many years, it continues to thrive. Likely because it is constantly evolving. The core remains the same: less, but better, with slowness as a mark of quality. But its expression has changed and has branched out into a wide range of industries and products since the slow food movement first put the concept of “slow” on the agenda decades ago as a reaction against fast food and globalization.

Today, slow living is much more than slow-risen bread and anti-globalization. One might perhaps consider slow living not so much a lifestyle trend but a philosophy, as it represents a way of being in the world where presence, attention to detail, and sensibility are in focus. And slow living is a highly relevant concept to highlight when discussing luxury and status symbols in 2024.

For example, what it means to be well-dressed is influenced by the slow living trend. It’s no longer about flaunting well-known luxury brands that, in an old-school capitalist sense, signal purchasing power. Being well-dressed now means wearing (slowly crafted) hand-knitted items, “showcasing” your creative repairs, and investing in handmade clothes, upcycled garments, or carefully selected vintage outfits.

And then there’s time. Time is perhaps the ultimate luxury in our era. Anything related to time exudes luxury; items that are imbued with time because they are crafted carefully and slowly — whether it be artisanal work or products that incorporate handmade elements, or products, concepts, or services that encourage cherishing one’s time or taking time to be present.

Time is a luxury because it is scarce. Knitting and embroidery, cooking from scratch, growing a kitchen garden, etc., signal that one has time, or has taken the time, which is a status symbol in an age of stress. Just as sensory, tactile, varied lifestyle products are in the era of smooth surfaces.

In this context, it is thought-provoking, and affirming, to notice how podcasts are getting longer and longer (the podcasts I listen to have gone from being around 30 minutes to two, three, or sometimes even up to four hours long), and how extremely long novels are enjoying great popularity (I just finished reading my second 800+ page novel since summer, The Wolves of Eternity by Karl-Ove Knausgård, and I am far from the only one who enjoys lingering over fiction that takes its time with atmospheric descriptions and thorough character development). Popular literature in the self-help genre is also increasingly concerned with time and becoming master of one’s own time, for example by scaling down consumption and working less (I’ve just read the brand new Saving Time by American bestselling author Jenny Odell, which, in line with the zeitgeist, advocates a return to nature’s rhythms and a departure from the idea that time is money).

Movies are also getting longer and longer; 3.5-hour movies are no longer unheard of (recent examples include Killers of the Flower Moon and Oppenheimer). This trend can be seen as a reaction against TikTok and YouTube shorts, which are by definition the antithesis of deep engagement, and which have contributed to a collective attention deficit. Or it may stem from the status and luxury of taking the time to go to the cinema and watch a full-length feature film.

Finally, a noteworthy Instagram trend right now is homesteading. Homesteading is a concept linked to off-grid living and self-sufficiency, but it spans a spectrum that includes everything from growing one’s own tomatoes to homeschooling and fermenting. For example, check out the profile Motherhens Homestead, which, with statements like “The goal isn’t Gucci bags, it’s acres of land,” taps directly into the new concept of luxury, or Ballerinafarm, which, with its 10 million followers and its imperfect images of everyday life on a remote farm with a large family, offers an alternative to minimalist homes with designer furniture and impeccably groomed children.

Modern luxury is not ostentatious and polished. Quite the opposite, in fact. Luxury is associated with authenticity; with real people talking about things that matter to them, often about how they escaped the rat race. It is also associated with having the time to read 800-page novels, listen to 3-hour podcasts, bake sourdough bread, spend time with one’s children, and grow tomatoes. And with investing in well-made, beautiful things that last, both functionally and aesthetically, and that can endure wear and be repaired.

The artisan economy is connected to the experience economy — but not in its original version, defined by the sale of exceptional, exclusive (product- or service-related) experiences focused on individual purchasing power and personal branding. No, rather, it is an iterated version of the experience economy, largely based on a simple “back to nature” narrative, mixed with a little good old-fashioned joy of cooking and crafting, as well as a generous dose of community and local romanticism. And it is this scenario that designers, producers, and storytellers need to tap into.

Aesthetic examples of such an experience economy include the Danish-Swedish Stedsans, an off-the-grid forest resort offering stress-relieving nature stays with a focus on slow food and community, and the American Outstanding in the Field, which organizes large communal dinners in carefully selected locations around the world, focusing on local food and beverages, nature experiences, and community.

What is considered luxurious today reflects the beginning of a sympathetic era focused on presence, connections, ethical production, and humanity.

June 10, 2024

Perfection is the most unnatural way of life

Nothing is more life-denying than fighting against the law of life: everything is on the way, and not in its final form.

Daniel Quinn, The Story of B

This quote from Daniel Quinn’s book The Story of B might appear simple, but it contains deep wisdom that seems to have been forgotten in the mainstream culture of our time-era.

Everything is on its way, and not in its final form. This is the law of life. And as much as we might view our time-era as the most evolved and accomplished in human history, it is the most stagnant one ever to have existed — and hence the most life-denying and rigid, and the most unsustainable.

Why?

Because it goes against the law of life: the law of everything always being on its way and the law of abundance.

Because it goes against the law of life: the law of everything always being on its way and the law of abundance.

We are concurrently getting surpassed by technology; AI and robots can do many things better, quicker and smarter than us. So, finding out (and improving and honoring) what is uniquely human should be our focal point.

Maybe this involves nourishing the senses and sense-experiences that make us human; touch, tastes, scents. Because whereas robots can be created to see and listen, the senses of touch as well as our ability to taste and smell and get aesthetically nourished herefrom is uniquely human.

It could also include a renewed focus on and respect for crafts, the perfectly imperfect creations made by human hands for human hands. Or creation of music, literature, art that isn’t perfectly polished, but due to is playfulness, such as the creation of new words or sentences, or of asymmetrical compositions.

My garden

My gardenA sustainable way of life is a justifiable way of life, and fighting against the natural development of things and natural abundance is not justifiable. It is stagnant and unmaintainable. This stagnancy manifests as climate change, as overpopulation, as natural disasters, as famine, as pandemics, as pollution, as depression, as exploitation of humans, animals and natural resources, as overconsumption, as extinction of species, as devastating homogeneity, as inequality, as cultural poverty, as despair, and as arrogance.

We tend to think that our time-era favors development and innovation, but actually, the way we innovate and develop is disrespectful to the law of life. Our most innovative products are not made to support development and to be on their way; they are designed to be experienced as obsolete after a short period of usage so that the wheel of consumption can keep turning.

Our modern way of life is stagnant as it is filled with unsatisfying routines and empty calories in the shape of mindless entertainment and overpriced convenience food, and hence not built up around abundance and natural growth. We have sacrificed the colorful variation of cultures, ways of life, and the abundance of nature on the altar of homogenization, convenience and perfection.

My son walking to school

My son walking to schoolIf nothing is in its final form why seek perfection — or why even talk about perfection? What is perfection? The perfect face, the perfect body, the perfect mind? The perfect tree, the perfect apple, the perfect egg? The perfect dog, the perfect ant, the perfect butterfly? Why seek clones of the “perfect being” (whether that being a farmed pig, a flawless apple, or the perfectly shaped and smoothened human face and body) when that is the most unnatural way of life — well, even life-denying?

The law of life is abundance, Quinn also states in The Story of B, and abundance involves diversity: there aren’t two leaves, ants, cats, birds, mites, cows, apples, oak trees, or humans that are the same, so why seek a uniform look and shape and name it perfection? The smooth, symmetrical, impersonal look that characterises each artificially modeled, gene modified, and smoothened fruit, animal or tree (or human face for that matter) is not justifiable, is not sustainable. It constitutes the opposite of life, of abundance. It is stagnant.

Rewilding nature doesn’t mean returning to an “original” perfect stage. It isn’t possible as everything is always in process, and is always on its way. And, rewilding the late-modern human being does not include maintaining an eternal state of youth — or returning to a perfect, smooth, unblemished starting point. That is not life, that is not development, that is not progress.

Our approach to sustainability has stagnated, and is stuck. Sustainability is about sustaining, not about perfection — because there is no such thing as perfection.

Sustainability is furthermore not about circularity — because circular economy and development comprises an immense strain on the natural environment; breaking things down and reconstructing them into new, perfect objects is not natural, is not justifiable, is not natural.

Rather, sustainable development should be focused on iterations; on being in motion, on always evolving and getting better, but never on becoming perfect.

Because perfection is the end, and there is no end.