Leslie Patten's Blog

August 30, 2025

HOW TO TRACK A MOUNTAIN LION

“She’s close.”

Mountain lion biologist Quinton Martins holds up an antenna while listening to a series of beeps from his hand-held receiver. Martins is searching for a female mountain lion wearing a failing GPS collar that needs replacing. As he leads us across a stream towards the oak and bay hillside, these locator pings indicate she’s alternating between two areas on either side of the creek. Martins thinks she may have a kill, which would be great news. If she does, then he can place a cage trap to recollar her.

Sharon Negri of the Mountain Lion Foundation and I are tagging along, hoping to catch a glimpse of this elusive animal. The hillside is steep with no clear trail as we trudge through tight brush and poison oak, occasionally stopping as Martins rechecks the lion’s location.

“She’s very close. On the other side now, maybe forty meters away in those trees.”

This particular cat, Martins tells us, had at least one kitten who would be eight months old. But the resident male recently died of bacterial bronchial pneumonia linked to Feline Leukemia Virus, opening the territory for a new male. If that’s the case, it could mean this new male might kill the kitten in order to entice the female to breed again.

Martins unique trap system. It triggers by weight avoiding triggering non-target animals

Martins unique trap system. It triggers by weight avoiding triggering non-target animalsMartins has been running a mountain lion study in partnership with the Audubon Canyon Ranch in Sonoma County since 2016. True Wild, his company with his wife, focuses on coexistence with wildlife and offers customized African safaris as part of their conservation efforts, connecting people to nature in a profound way and working with participants to become more involved in conservation initiatives where possible.

We stop again for another location check. Now Martins’ receiver displays a significantly stronger signal, indicating the cat is on the opposite bank exactly where the second ping showed up on his computer yesterday. Sharon and I carefully navigate the streambed around an enormous jumble of jagged boulders, possibly dumped from soil preparations for the vineyard whose private lands we have permissions to be on. At the ping site there is no indication of a kill while the cat has disappeared through thick bush and over a rise. Knowing this female was so close, yet we never saw her, leaves us frustrated. It is a repeat of a common scenario: cougars watch people yet we humans never see them.

Heading back to the car, Martins points out fresh tracks in the soft dirt. “She’s been here, going back and forth. This cat has been incredibly difficult to find.”

Luckily, Martins has one other lion he wants to sleuth out. P49 has a good working collar that indicates she might have a kill. Martins’ goal with this cat is to find out if she has kittens. As we drive 45 minutes west to the opposite end of Sonoma County, Martins lays out the unique difficulty of doing a wildlife study in a highly populated rural area.

Martins getting data from a sedated lion he is collaring

Martins getting data from a sedated lion he is collaring“The males we have collared—P5 has 17,000 private properties in his territory. P31 has 11,000 private properties. How do you contact that many people and access all those properties to inspect fences or signs of prey? This dilemma is confounded by an increase in weekend private property owners. When you overlap a land parcel map it is as if you are looking at 50,000 or 100,000 mini ecosystems, so you can’t just throw a vegetation layer over it and say ‘OK, this is what the cats are doing.’ As their primary prey is deer, it might look like great deer habitat on a map, but in many cases these properties are fenced to keep deer out. So there might be no deer in areas where you expect deer, but cannot tell because you can’t access the properties very easily. And walking each individual land parcel, one finds different plant and animal resources, a variety of fence types that block or allow animals to move through, and each parcel managed differently to some degree.”

Martins tell us lions are using fences of any type to strategically block or corner and kill deer. In fact, when we approached the previous property, Martins pointed out a cougar-killed deer carcass hanging against the fence that enclosed the vineyard.

Our second property owner is an animal lover excited to discover there’s a lion hanging around his property. He has a large piece of wooded land, over 200 acres, nestled in the hills of Sebastopol. He greets us at his main house and we follow him down the road to where Martins recorded a series of GPS fixes the night before. The dense cluster of pings is a hopeful sign this cat has made a kill and is still hanging around. Cougars can spend up to three days or more consuming an adult deer. They will cover their kill to preserve its freshness as well as deter scavengers while they rest nearby.

The GPS telemetry data indicates the cat traveled along a hillside where an overgrown two-track is still visible. A short hike leads us to her kill—a yearling deer. Cougars kill with a bite to the neck, then consume the internal organs first. Big cats, along with their small domestic cousins, lost the ability somewhere in evolutionary time to convert carotenoids like beta carotene into Vitamin A, so they have to obtain it directly from these nutritious organ meats. That’s exactly what this cat has done. I also see she has begun to pull the fur away with her incisors. Although this is a small deer, Martins thinks there’s enough meat on the carcass that the cat will return, and if she does we’ll find out if she has kittens. The VHF radio signal from her collar indicates she is resting on the opposite hillside only a few hundred yards away.

“She’ll return under cover of night,” Martins tells us as he sets up three trail cameras focused on the carcass.

Even though we never did see a mountain lion, the day was exciting as well as instructive. Conducting a mountain lion study in an urban/rural area has tremendous challenges and complexities that studies in vast wilderness areas like where I live in Wyoming do not. First there is no snow, so finding tracks is as elusive as the animal itself. Second, most mountain lion studies rely on dogs to do the tracking and treeing of the animal. Once treed, biologists can easily dart the lion and lower him to the ground to be collared and released. Obviously dogs can’t be utilized in areas where there are so many people on small private land parcels. In addition, while there are some public lands in Sonoma County—mostly small county parks dotted throughout his study area—Martins’ lions live in territories encompassed by thousands of private properties, meaning he has to obtain permissions from each owner before visiting. Most, but not all owners are happy to help, but even when he has their cooperation, each visit requires one or several phone calls to gain access. It’s a lot of human PR work.

A few days later, Martins relays the good news. P49 has two healthy cubs with her and sends us a photo of the family dining on the carcass. I realize that instead of one lion, there were three nearby, none of whom we saw. But to be fair, mountain lion mothers sometimes stash their kittens while they hunt, then bring them to the kill site afterwards.

P49 with her two kittens on the kill we found.

P49 with her two kittens on the kill we found.These kittens are highly dependent upon their mother’s hunting skills throughout their first year. The span between six and eighteen months is especially important for the cubs because they are learning the art of hunting and killing prey. In addition they are exploring their natal range and learning how to deal with potential enemies. Dispersal occurs usually between 12 and 24 months. Lion dispersal is critically important for genetic diversity, as well as for geographic expansion. Females tend to stay close to their birth mother’s range, while males need to find an empty slot devoid of a dominant male. The odds are tough for dispersing males, who roam much farther than females and have to contend with other territorial males. In an urban/rural landscape, these kittens will need to learn to avoic livestock plus they have a higher chance of contacting diseases from domestic cats like Feline Leukemia Virus and the H5N1 virus, commonly referred to as bird flu which cats have a higher than 70% chance of dying from.

Through Martins work we hope to have a better understanding of mountain lions living in a unique situation sharing their territories with a high density of people in a complex urban/rural landscape. Plus, this coexistence with California’s communities work will hopefully give these iconic cats increased odds of survival, ensuring their vital role in helping ecosystem integrity is maintained.

More info on Martins work and California mountain lions can be found in my book Ghostwalker

If you want to follow updates of Martins’ Sonoma study…

True Wild’s work stems from our love for wild places. We are driven to find ways for people to appreciate and make an effort to protect wild places and the wildlife that shares the world with us. We believe that people can coexist with wildlife through practical and achievable methods and in doing so, serve people, domestic animals, wildlife and the environment we are all living in.

True Wild (www.truewild.org) and Audubon Canyon Ranch in partnership with Sonoma County Wildlife Rescue , are spearheading an essential mountain lion research and education project in California’s San Francisco North Bay Region. We are a key community resource for people to be able to coexist with wildlife, particularly mountain lions. In Africa, we support high impact, coexistence-focused projects that will protect large wild places while benefitting local communities.

We want to maximize impact with minimum overhead, seeking to achieve win-win situations for everyone involved. Donations become investments, involvement leads to tangible returns. We encourage and actively seek both intellectual and financial support to offer solutions to the growing ecological issues our world is facing.

We offer impactful and extraordinary safari opportunities, connecting people to nature in the most profound way in some of the most beautiful places in the world. We view our safaris as a platform for providing a valuable life experience as well as highlighting the significance of wild places that need protection. Each safari is tailor-made to maximize the personal experience.

July 4, 2025

Hiking Northwest Wyoming – Dream Lake Wind River Mountains

THIS IS THE FIRST OF A SERIES OF SHORT STORIES AND MEMORIES FROM MY YEARS LIVING IN NORTHWEST WYOMING.

IN 2012 I hiked to Dream Lake. Dream Lake is an access point to the central Continental Divide in the Wind Rivers. I planned a 7 day backpack loop with a side trip up to Europe Canyon. The Europe Canyon trail access wasn’t marked. Instead a cryptic sign said “trail abandoned” and there was no map indication of where to turn. But using some map navigating, this was the correct route to the lake.

Cryptic Sign to Europe Lake

Cryptic Sign to Europe LakeTaking the abandoned trail, I arrived at Europe Lake, a beautiful gem that sits at the base of the crest of the Continental Divide. A fire on the east side made for a smokey view. Two backpackers from London were camped there. Experienced hikers, they’d cross-countried to the lake. They shared some stories with me of their travels. Because they in England they received 6 weeks off from work every summer, they had some great adventure stories. One story they relayed stood out of when they’d rescued inexperienced and unprepared hikers from severe altitude sickness in the Himalayas.

Two young men were hiking with a woman. All three were huddling in a rest cabin at over 15,000 feet. The woman had severe altitude sickness, yet the fellows were planning on continuing without her. This woman would die if she couldn’t get to a lower elevation immediately. These British backpackers changed their itinerary and assisted her down the mountain for medical care.

British hikers who rescued a woman in the Himalayas

British hikers who rescued a woman in the HimalayasThat night I returned near the main trail and camped among the rocks near timberline. I was awakened in the middle of the night to a strange animal sound which I couldn’t place. Come morning I checked the tracks on the trail and felt it must have been a single domestic sheep looking for the rest of its herd. Domestic sheep have since been removed from the Winds Wilderness areas.

On the way to Europe Canyon

On the way to Europe CanyonOn my final evening I camped with a group of retired Air Force fellows. They’d hiked along the Divide from the south end, probably starting at Sweetwater Gap entrance. One fellow had joined the crew from Ohio and didn’t take the time to acclimate. He had terrible altitude sickness, throwing up with a splitting headache. I suppose it ruined his trip. By the time I camped with them, he’d pretty much acclimated though he’s far from the first person I’ve encountered in the Winds that had altitude sickness. Taking time to acclimate can be essential.

A lake not far from Dream Lake. Lone horseback rider

A lake not far from Dream Lake. Lone horseback riderBut the real story here is when I made it to the take-out where my car was waiting. We all hiked down together. As the Air Force guys were meeting their ride and I was packing up, a backpacker who was loaded up with heavy gear came down the trail followed by his Labrador Retriever. That poor dog looked half crippled, limping slowly all the way to the vehicle.

I asked this hiker where he’d come from. Most backpackers only do a few days and their dogs do just fine as long as their feet are protected when necessary.

I’ve been out of a month. It’s been fantastic. I’ve hike the entire Winds.” I asked how old his dog was. “Eleven,” he said. And when I told him his dog looked in very poor shape, he just replied “He’s fine.”

I felt angry. Eleven is old for a Lab and that dog was not fine. He was suffering. His feet and joints hurt, and his owner was being completely insensitive to his dog’s needs, thinking only of himself.

There are a few lessons here. People tend to be worried about grizzly bears in Northwest Wyoming. But they are not the worry. Bears aren’t interested in people and try to keep to themselves. Mosquitos, insufficient preparation, overdoing it to yourself or your pets are more to the point. Be safe out there and have a good time.

My dog and I at Europe Lake in the Wind River Mountains

My dog and I at Europe Lake in the Wind River Mountains

May 30, 2025

Foraging with Bears

Today I took a hike along a high reef, or what they call here in NW Wyoming a “reef”, probably because at one time this limestone plateau was under one of the oceans that covered this area. It’s a flat mesa with cliffs to one side and forested ridges on the other. The soil as you can image is very thin, but allows a sparse forest of lodgepole pines and open meadows. It’s a great place to see wildflowers right now, especially before the cattle come in to free range the area.

A known place for grizzlies in the spring and fall, Wyoming Game and Fish even use this area every 4 or 5 years to set traps to collar the bears. The hike begins on a closed dirt road (not open for vehicles until mid-July to protect the bears). Elk and grizzly tracks are easily visible.

Front and back grizzly tracks.

Front and back grizzly tracks. Along the way I’m tasting the tips of young fireweed. Great crunchy texture, mild flavor until the very last then there’s a bitterness. Emerging Indian Paintbrush is also edible but pretty bitter all the way through. Vast carpets of my favorite, Spring Beauties, make a great salad addition.

We’ve had a cool and rainy May, inhibiting the emergence of a lot of spring flowers. But with the recent warm days, it seems everything is out all at once. Shooting stars, usually almost gone by now, are everywhere. Their flowers are delicious along with mountain bluebell flowers, both in the borage family and have that similar taste. White flowered onions and biscuit root (lomatian) are out. Larkspur, not edible but poisonous, is emerging. Larkspur is fatal to cattle. I’ve seen some years dozens of cattle die from eating larkspur on the national forests.

Spring Beauties

Spring BeautiesSome Pasque flowers, usually done by now, are still around, some even just opening. Even Phlox is still blooming. And my favorite shrub, Buffalo berries, are just leafing out. Buffalo berries are dioecious, meaning male and female reproductive structures are on separate individual plants, not a common thing in the plant world. Arrowleaf balsamroot, strawberries, woodland star, and fritallaria are all blooming and elephant’s head has sent its spike up, ready to open.

Woodland star

Woodland star

Lots of Woodland star mixed with larkspur

Lots of Woodland star mixed with larkspur

Fritallaria

Fritallaria

Elephant’s head

Elephant’s headWhile I forage, a bear has been busy. I’m trying to figure out what’s going on here. I think mama grizzly is clawing the bark on this tree to get at the sweet spring sap that’s flowing while her cub climbs up the tree. I’d normally say a black bear as adult grizzlies don’t climb, but this is a grizzly area and on the way up I ran into a black bear archery hunter with four llamas. He’s been camping on the reef for a few nights. He saw several grizzlies but no black bears. Black bears don’t hang around areas where there’s a lot of grizzlies.

Bear sign

Bear sign

On the plateau, a bear has been busy foraging for biscuit roots. I uses my knife to dig one up. Luckily the soil is soft since its been raining as these roots grow in tight dry soils. I have to dig pretty carefully and deep.

Biscuit root

Biscuit rootYou can see how deep these bears have to dig in order to extract the whole root. Of course, with their long claws, that’s easy for them. Bears will till up an area with biscuit roots, a favorite treat. But they always leave some. That ensures more will come back next year.

Bear scat with digs

Bear scat with digs

He won’t dig all the biscuit root up

He won’t dig all the biscuit root upSo while we humans are foraging, bears are too. In past times, humans watched bears to see what foods were good to eat. 80% of a bear’s diet is edible for humans, The other 20% are grasses, which we cannot digest. Co-existence isn’t hard. We just have to take a cue from the bears and always make sure to leave some plants for next year’s harvest.

March 6, 2025

The Infamous Ben Lily

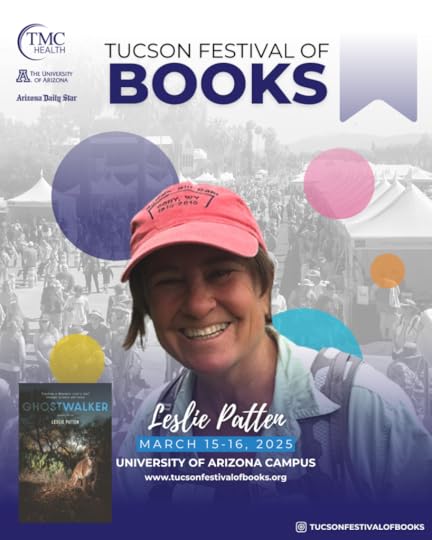

I’m in the Silver City area for a few weeks waiting until March 15th when I am speaking at the Tucson Book Fair. Hiking around the Gila National Forest (our first Wilderness thanks to Aldo Leopold), I can’t help but contemplate Ben Lilly.

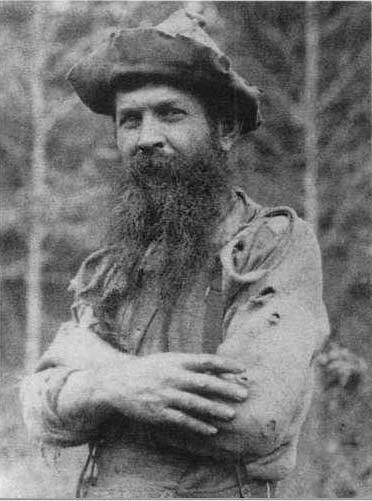

Ben Lily features prominently in the second chapter of my latest book Ghostwalker: Tracking a Mountain Lion’s Souls through Science and Story. Lily was single-handedly responsible for the deaths of 500 mountain lions, over 600 bears, and the last grizzlies in the Southwest. He was a predator-killing machine epitomizing the hatred for predators in the early 20th century.

Today I took a short hike to what locals call Ben Lilly Pond, a 1/2 mile turn-off from Highway 15 before the Ben Lily Memorial.

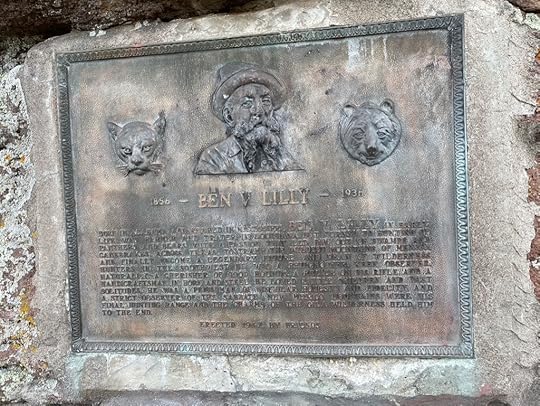

The Ben Lilly Memorial plaque in the Gila National Forest against a large boulder overlook. See the lion and bear on either side

The Ben Lilly Memorial plaque in the Gila National Forest against a large boulder overlook. See the lion and bear on either sideAt the age of forty-five, in 1901, Lilly called his second wife and three children together, kissed them goodbye, and left them everything he owned except five dollars. Leaving his home state of Louisiana, he headed west for a land where the big predators remained. His life philosophy was now well formed. He regarded himself as the policeman of the wild, “a self-appointed leavener of nature.” Bears and lions specifically were, by their very nature, evil. Lilly considered it his biblical duty to set things straight by killing these “devil” animals. He had evolved into a religious fanatic, mixed with a special kind of mysticism. As Lilly traveled west, he left behind a wake of wildlife destruction. But his folk-hero status was growing. While hunting in Texas in 1907, Lilly received a telegram summoning him to a presidential camp on Tensas Bayou for a bear hunt with President Theodore Roosevelt.

1908 Scribner’s article: Theodore Roosevelt “In the Louisiana Canebrakes,” Scribner’s XLIII (January 1908) Courtesy Avery Island Archives, Avery Island, La.

1908 Scribner’s article: Theodore Roosevelt “In the Louisiana Canebrakes,” Scribner’s XLIII (January 1908) Courtesy Avery Island Archives, Avery Island, La.In 1908, Lilly hunted grizzlies, mountain lions, and black bears in Mexico for three years, sending skeletons and skins back to the Smithsonian Institution. He returned to the United States, entering through the boot heel of New Mexico. Now in his mid-fifties, his predator killing career was waxing as a new era of government eradication programs for predators began. His reputation was widespread, his services were in high demand among ranchers, and he was finally well paid for a passion previously pursued only as a personal vendetta.

On the road to Ben Lilly Pond. An old ranch entrance now shot full of bullet holes

On the road to Ben Lilly Pond. An old ranch entrance now shot full of bullet holesWhen trailing with his dogs, Lilly would forget to eat and drink, sometimes for days on end. Then he’d gorge himself on his kill and the bit of corn meal he carried with him. He never kept the skins of the animals he killed for himself, considering them a worthless piece of clothing. He was on a mission, and that intensity of focus molded him into an expert woodsman. He had no coat, but piled on layers of shirts. If he was cold, he’d build a fire, push aside the coals, and sleep on the warm ground. At least once a week he bathed in a stream, sometimes breaking away the ice, then rolling in snow to dry off. The air in a town was toxic to him, and when offered a bed, he preferred to sleep outside on the ground with his dogs.

To the men who knew him, Lilly was a man of complete honesty and character. He never swore, drank, or smoked, and famously rested on Sunday, his holy day. If his dogs treed a cougar on Saturday night, the animal had a stay until Monday morning. But his religious beliefs extended to the supernatural. Lilly’s favorite meats were bear and especially lion, which he felt would endow him with exceptional instinct, prowess, and agility to pursue his quarry. He expected no less of his dogs than he did of himself—running them for days without food. He would go out of his way to make sure they had water before he did, took great pleasure in watching them work, and valued a dog’s intelligence rather than a specific breed. Yet ultimately, they were simply tools of his trade. If a dog began running trash or quit the trail, he had no need for him, and the dog was beaten or shot to death.

Ben Lilly was unquestionably one of the most destructive figures in North American wildlife history, contributing to the demise of the grizzly bear and the wholesale reduction of mountain lions and black bears in the Southwest. The plaque above was erected by friends who knew him, back in the 1930s. But there are some folks today that revere Lily as the ultimate hunter, apparently ignorant of the havoc and destruction he left behind in the Southwest.

The terrain and vegetation of the Gila

The terrain and vegetation of the GilaWalking the jeep road to the pond (which was completely dry), I did have to marvel at how this strange man maneuvered these mountains. The scrubby oaks, pines and junipers are so thick they are almost impossible to pass through. The ground is rocky and the going rough. But I wonder how many people who take these short hikes even know who Lilly was and the devastation he caused to our wildlife.

Ben Lilly

Ben LillyLilly’s lack of true reverence for life is the antithesis of our values of ethical hunting and wildlife conservation—a misguided, warped sense of nature that viewed large predators as “endowed by their very nature with a capacity to wreak evil…and should be destroyed.” A misshapen, exaggerated product of his era, one could consider Lilly a vessel—a queer, half-crazed man who performed his executions as a service for others, for the government, and in his own mind, for God. Genocidal war on predators had been codified as our nation’s God-given right, and Lilly was their proxy.

If you are in Tucson on March 15th, come to the Tucson Book Fair. It’s huge with a wide variety of authors and speakers. I’ll be speaking at 10am at the Western National Parks Association Stage

November 25, 2024

Trail CamerasTrail cameras for wildlife spying have becom...

Trail cameras for wildlife spying have become a popular pastime. Not only has the video and photo quality improved, but the price point for high quality cameras is lower every year. I’ve been using trail cameras since around 2010. I thought it would be interesting to do a short post on my personal evolution of my use and what I’ve discovered.

Professional photographers and folks that are handy with manual camera adjustments have switched from store-bought trail cams to DSLR cameras. Using a DSLR camera trap requires a lot of knowledge of not just wildlife tracking but lighting positioning and camera settings, but the payoff is great. For my expanded Ghostwalker book out this year from University of Nebraska, even though I have thousands of great mountain lion photos and video, I needed to engage these experts for high quality photos that would reproduce in print. I’ve never been great with manual adjustments so point/shoot cameras, like trail cams, are my go-to.

Amazing capture by Jeff Wirth using a DSLR. Wirth graciously consented to let me use some of his photos in Ghostwalker: Tracking a Mountain Lion’s Soul through Science and Story

Amazing capture by Jeff Wirth using a DSLR. Wirth graciously consented to let me use some of his photos in Ghostwalker: Tracking a Mountain Lion’s Soul through Science and StoryWhen I first started using trail cameras their quality was very poor, but I was mainly interested in who was visiting the nearby forest. I caught grizzly and black bears on the animal trails, along with deer, coyotes, and wolves. I was anxious to catch martens who don’t follow trails. To that end I built a box trappers use, baited it, and put a camera on it (of course I didn’t put a trap inside!). Bobcats also don’t follow trails very much and since I do have bobcat trapping in my area in winter, the animals were rare on the landscape. I hung shiny objects to attract the cats with a camera positioned on it. Still, I almost never captured a photo of a bobcat.

After two years of camera trapping, I had several epiphanies that changed the course my experiments. First, after watching trapping in my area, I became aware that my baiting was contributing to these animals becoming less wary of actual kill traps. Therefore I stopped all baiting and scenting. But the biggest revelation was how to reliably capture animals on camera.

Elk on frozen river at a crossing point. I could see the crossing using track I.D.

Elk on frozen river at a crossing point. I could see the crossing using track I.D.I had been lucky to capture several mountain lions, and found lion tracks in different areas. That piqued my interest so I attended a class on mountain lions by researcher Toni Ruth in Yellowstone. During that class I watched a video of wildlife on a mountain lion scrape site. I knew about scrapes but had never seen one nor did I know how to find them. A scrape is made by a male lion with his back feet, usually urinated on, to mark territory. Lion scrapes apparently are big attractants for all sorts of wildlife. Once I learned where to find scrapes, I sought these out and placed cameras on them. Scrapes draw almost all the prey and predators in an ecosystem. By continuing to use these same locations for over 15 years, I’ve captured amazing photos, but the real gold here is monitoring sites for so long that you get a read on the ebb and flow of wildlife activity.

(ABOVE VIDEO OF WOLVES HAD CAMERA PLACED ON A TRAIL HEAVY WITH SCRAPE SITES)

A friend who is a feline researcher told me keeping cameras at the same location for many years provides a good indication of the health of the local mountain lion population. Houndsmen and researchers use dogs to find lions, which gives a good clue to the waxing and waning of lions in a designated area. Would monitoring scrape sites alone give me a general idea of lion health?

Lions are impossible to identify. Puma concolor, their latin name, means cat of one color. Unless they have scars such as nicks in an ear, etc. they look alike. And in a hunted area, males usually don’t last long; but another young male will come to fill the void. I did get an indication that I could monitor lions this way a few years ago. In 2015-2016 we had record snows. Our mule deer population crashed. By early spring when the first grass emerged, the landscape was littered with dead deer. Predator populations lag behind prey drop, but it wasn’t long before I noticed I wasn’t catching females with kittens on my camera. Without sufficient prey, females will have smaller litters or none at all. 2017 was the last photo of a mom with young kittens. Although I did catch young dispersers, there seemed to be a dearth of females in my area until 2021. coinciding with a rebound in the mule deer population.

Additionally, the same thing was going on with cottontails and bobcats. Bobcats also visit lion scrape sites, and male bobcats like to scrape over lion scrapes. Rabbits go through seven year cycles and sometime around 2014 I noticed fewer and fewer rabbit tracks in my study area. I also stopped picking up bobcats on my cameras. The rabbit population had crashed and with it bobcat food. Then around 2020 a rabbit took up residence at one of my camera sites. Within a year, more rabbits at other sites, and soon there were rabbits everywhere. The bobcat population rebounded. Now I was catching bobcats with kittens frequently. An indication of how keeping cameras in situ for an extended period can tell the story of the land’s health.

Bobcat visits lion scrape site

Bobcat visits lion scrape siteIn summary, there are many ways to use trail cams. Research, exploration, pleasure. For me it’s become a tool not just to see who is visiting, but to monitor over time the swings of the ecosystem: how weather patterns, food availability, habitat health, and natural cycles affect the wildlife in my study area.

For more videos from my trail camera captures, see my YouTube site

November 22, 2024

From the Desk of Leslie Patten: Searching for ‘One-Eye’

For those of you who follow my blog, I recently wrote a guest post for University of Nebraska, the publisher of my most recent book Ghostwalker, Expanded Edition.

Here is the link. Please comment at the link site, share, and enjoy the story

One Eye. Notice the bluish tinge on her blind eye

One Eye. Notice the bluish tinge on her blind eye

September 27, 2024

Grizzly Bears and Delisting

It’s pretty well known that unless you see a grizzly with cubs, its extremely difficult, if impossible, to tell male from female grizzly bears. Recently this was confirmed to me on a trip to Alaska to bear watch. We flew to a small lake contained within the vast wilderness of Lake Clark National Park. The flight took about an hour leaving from Anchorage, landed on the lake, where about fifteen of us boarded pontoons and spent the day circling the lakeshore watching grizzly bears catch salmon.

Mom with 2 cubs fishing for salmon

Mom with 2 cubs fishing for salmonBecause these bears are in hyperphagia and also very used to the boat, we could approach quite close, say fifty feet away while the bears fished. Our boat captain was a veteran with thirteen summers under his belt of guiding and watching these bears. He knew the best spots around the lake where the fishing was good for the bears. And he told us something interesting. When we’d see a single bear (versus a mom with cubs), he had no way of knowing if that bear was a male or female. There was no size comparison to use or any other metric, and he’d been watching these bears for over a decade. In all, we saw over thirty bears in one day.

Bear catches a salmon

Bear catches a salmon Pontoon boats left. This small lake was where we watched grizzly bears fishing all day

Pontoon boats left. This small lake was where we watched grizzly bears fishing all dayThat brings me to the status of grizzly bears in the Northern Rockies. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Agency is setting the stage to delist the Great Bear next year. Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho are actively pushing for a hunt. The local media is telling stories to encourage a hunt. (“While he doesn’t want grizzlies gone, he thinks hunting them would control their numbers and deter them from attacking people and livestock.”)

If delisting didn’t automatically include hunting, I’d be all in. We delisted bald eagles but don’t hunt them. The narrative around “a hunt” is that grizzly bears will “learn” to stay away from humans, or as the quote above, “control their numbers”.

Let’s take the second one first, “control their numbers”. Females don’t begin to have cubs until their 5th or 6th year. Cubs are born in the den the first winter, then stay with mom for 2 more winters. That brings a reproducing female to almost 10 years of age before she can hopefully replicate herself with another female. Grizzlies were the first mammal listed under the ESA in 1975. Fifteen years later, in the mid-80s, most biologists felt they were going to go extinct in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). It took almost fifty years to go from about 200 grizzlies in the GYE to 1000 bears! Every year about fifty grizzlies are killed for a variety of reasons, mostly human caused (euthanized for livestock depredation, killed by hunters, killed by other bears. 53 so far this year 2024). Add a hunt to that and we can very quickly decimate the population once again.

Does killing a solitary animal communicate to other solitary bears to stay away from livestock and human? There’s a sub-adult grizzly that’s been foraging clover this fall in the meadow on the Game Management Area. You can drive your car and watch that bear. If you drive too close, he runs away. But if there’s a hunt, one can legally shoot from a dirt road in Wyoming and he’s certainly close enough, and busy enough foraging, that shooting him would be like shooting fish in a barrel (which is how I see grizzlies in the fall, very absorbed in rooting around because they are in hyperphagia). An easy target for a bear hunter and would killing that sub-adult teach other bears a lesson? Of course not.

Do we need to control grizzly bear numbers? Besides the fact that in the GYE we are already killing over fifty bears a year without a hunt, if GYE grizzlies are to survive long term, they MUST connect naturally with bears in Montana (Northern Rockies). So far they haven’t done this. Wyoming’s plan is to keep killing bears on the edges, the very place where grizzlies must venture in order to connect and foster genetic diversity. Montana’s “plan” is to fly bears into the GYE to maintain genetic diversity, a completely absurd idea!

Anyone who has watched grizzly bears, and any bear biologist will tell you, that these animals are as smart (or smarter) than the Great Apes. They are on par with humans in terms of shear intelligence. Hunting them is simply painful and mean-spirited. Over 100 tribes signed a treaty against a hunt. Grizzly bears are sacred to these tribes. Moving “problem” bears to tribes that want them make more sense. As well as…

Protect your livestock, feed and garbageMost maulings take place in the fall when hunters are prowling quietly through the woods and bears are getting ready for winter. Carry bear spray and if you are not familiar with hiking/hunting in grizzly country, there are plenty of deer and elk all over this country where there are no grizzly bears. What was shocking to me in this article was that these guys had been charged three times over the last several years. I’ve hiked in grizzly country for twenty years and haven’t had an encounter like they described. I don’t know the details of their situation, but it does make me wonder what they are doing wrong.I certainly have sympathy for small producers who lose stock to grizzlies on public lands. But public lands are all that our wildlife have and free range cattle should be “at your own risk”, though those risks can be minimized. As noted in my previous post, the ballooning of maximum stock levels on public lands provides a reason for bears to stay low during summer months instead of ranging to higher ground. Are we just feeding these bears with easy prey? There’s been a lot of recent research on non-lethal deterrents. It’s time that the state provides support for that instead of Wildlife Services or direct compensation for losses (grizzly kills in WY are compensated at 3 times the going rate of a cow).

August 26, 2024

Public Lands, Grizzly Bears, Cattle

I’ve got a theory. Bear with me as I tell my story.

This last June I was exploring a drainage that burned in the 1988 Yellowstone fires. There’s no trail but I’ve encountered coyotes denning farther up the draw; a place I like to go and investigate. The northeast side of the draw is filling in fast with a thick cover of young lodgepole tree. The ground, however, is a maze of burnt and rotting timber you have to clamber over.

June is when the free-ranging cattle are trucked into the valley. The major livestock producer runs several thousand head of cattle, all yearling males, which he rotates through a range of Forest Service allotments throughout the summer. Mid-June is a time when grizzly bears are foraging at lower elevations. By early July, summer heat and the lure of Army Cutworm moths drives the bears to higher elevations. These young naive yearling cattle roaming freely, especially in heavy timber, are easy Spring prey for hungry grizzlies.

The access to this side draw begins on an open hillside. Right away I notice fresh cow pies indicating that the yearlings have been here recently. As soon as I enter the dense lodgepole pine forest, something didn’t feel right. I pull my bear spray out of its holster, release the safety, and keep my dog at a heel. A large pile of grizzly scat—soupy, wet, and clearly from a meat meal—greets me amidst the tight tree cover. Then a waft of a dead animal fills my nose. The air is still but as the aroma is getting stronger, I can tell it’s coming from somewhere ahead of me. That was my cue to move swiftly to the open meadow on the other side of the creek and high-tail out of there. But I determined to return in a few months to see if what I sensed was correct. Months later in mid-August when I know the bears are up high and the cows are out of that area, I return to see if my instincts were correct. Sure, enough, in short order, after combing the timber, Hintza, my dog, easily locates the dead animal I smelled months ago. Yes, it was a cow. And yes, with all that fresh meaty bear scat, that had been a bear on it.

What was left of the smell from June.

What was left of the smell from June.But this wasn’t the first freshly killed cow by a grizzly I’d encountered in the month of June. A few years ago, in an adjacent drainage, I was walking along the gravel road when I saw a strange unnatural hump of dirt and sagebrush. There were drag marks across the road as well. The dirt hump was a covered cow, freshly killed by a bear, one of the most dangerous circumstances you can come across. Bears will defend their kills. The following year and in the same area, the warden rode by on an ATV and warned me I was heading for a dead grizzly-killed cow which he was about to remove. That’s three fresh grizzly kills, a very dangerous situation for a hiker or a horseman. But every summer on hikes I run into dead cattle fully consumed after they’d been predated on—stiff hides with bones scattered.

Those of us who live and recreate in grizzly bear country are instructed to secure our food. I use a bear-proof trash can. Others in the valley keep their garbage locked in their garage. Residents are very conscious of not feeding bears. Yet putting cattle out on public lands in early spring, when grizzlies are hungry and foraging down low, seems akin to putting food out for the bears, especially young naive yearlings. Bears are smart and I’m betting grizzlies here are learning there’s a good source of easy meat. It may even be possible that instead of heading to moth sites and higher elevations, some bears are sticking around throughout the summer. Yearlings who are free-ranging, unfamiliar with the landscape and its risks, are akin to leaving easy food out for bears. That linked article discussing two relocated bears for killing cattle says “bears that are determined to be a threat to public safety are not relocated and might be killed.” But who is creating that risk? If cattle, like our garbage, are not managed correctly, we humans only have ourselves to blame.

Caught this grizzly on my camera August 2, 2024. I know this bear. He usually comes around in the fall. Here he is below in 2016 early September on ripe chokecherry bushes.

Caught this grizzly on my camera August 2, 2024. I know this bear. He usually comes around in the fall. Here he is below in 2016 early September on ripe chokecherry bushes.

If cows are going to be free-ranging on our forests, consideration needs to be given to where and when. Don’t put cattle out in June when grizzlies are down low and hungry. As an alternative, livestock trucked in in June can be placed in areas that are highly visible with a cowboy checking them frequently. Free-ranging cattle in highly populated bear areas are not only endangering the bears (Wyoming has a 3-strikes rule) and livestock, but also hikers, cyclists, horse people and other recreationists.

So are we training grizzlies to hang around while the pickings are easy, akin to leaving garbage out for them? I think the Forest Service, who manages timing and allotments, can do a much better job for the bears, the cattle and the people. Ironically, jurisdiction is split. The Forest Service does the range management, but it’s the Game and Fish, through state mandates, that pays producers compensation for cattle killed by grizzly bears. But I think it all comes back to the first defense of proper range management to reduce cattle and grizzly deaths. A radical thought would be to have no free-ranging cattle in grizzly country. Why not! But if the status quo must continue, then shift and limit the timing of when and where cattle are located across the forest

June 21, 2024

What’s the Story? Cougars, Wolves, Grizzlies

There’s one place in my area where I’ve seen Glacier Lilies, but as soon as the melt starts the access road usually closes due to flooding. Since the weather has been cool, and next week predictions say it will be in the 70s, I decided to check out the spot to see if the lilies are up yet before the road closure. It’s a fairly remote less traveled trail and this time of year grizzlies are down low foraging while wolves are denning. The trail begins at the road’s end with a stream crossing, winds through a burnt valley before turning up a small drainage where the trail heads to a ridgeline pass.

Immediately grizzly tracks began faintly appearing on the dry ground.

When I turned into the forest drainage, the wet ground revealed two grizzly bears. That could only mean a mom and cub. The grizzly cub footprint appeared to be at least a one year old. I became more alert, unlocked my bear spray.

Smaller bear on the left

Smaller bear on the leftThe area I’d seen the lilies years before was about a mile up the trail near the pass. Bear tracks followed the trail plus revealed a 2 day old scat that said they’d been eating grass mixed with fur.

Closing in on my lily hillside, I found a clear wolf print in the mud. I hadn’t seen wolf tracks earlier on the trail.

wolf track

wolf trackAbout 150 yards before the lily area , I came upon what these bears (and wolves) were doing here. An elk kill right by the trail, completely consumed but about a week or less old. Clearly a cougar kill. I searched around the site a bit. No skull, only one leg left plus the spine and pelvis.

What a cougar kill looks like. Rumen pulled out to the left. The fur in a neat circular pattern cut off with the cat’s incisors

What a cougar kill looks like. Rumen pulled out to the left. The fur in a neat circular pattern cut off with the cat’s incisorsWhat did the tracks and the kill sign say about the story here? Of course, the only thing I can be certain of was this elk was killed by a cougar. But let’s think about what might have happened. Wolves and bears (grizzlies and black) push lions off their kill. With only one leg, and few fresh wolf prints, I imagined the wolves kicked the lion off the kill site, and hauled the other legs off, maybe to their den site over the ridge. The wolves probably consumed most of the elk before the grizzly mom and cub came along (their tracks fairly fresh) to finish off what was left. The fresh wolf track I found was probably a wolf returning to check on any left-overs, and maybe even encountering the grizzlies.

Unfortunately, I didn’t find my Glacier Lilies. Maybe just too early or maybe those bears ate them. But here is some other cool bear sign I found along the trail.

Bears use their claws to strip bark from a tree, then feed on the sapwood by scraping it from the heartwood with their teeth.

Bears use their claws to strip bark from a tree, then feed on the sapwood by scraping it from the heartwood with their teeth.

To learn more about mountain lions and their interactions with wolves and bears, read my upcoming book Ghostwalker: Tracking a Mountain Lion’s Soul through Science and Story out this fall University of Nebraska Bison Books. To pre-order a copy and receive a 40% discount, go to this link and use the code 6AF24 Open publish panel

May 17, 2024

Mountain Lion NewsI recently attended a presentation by W...

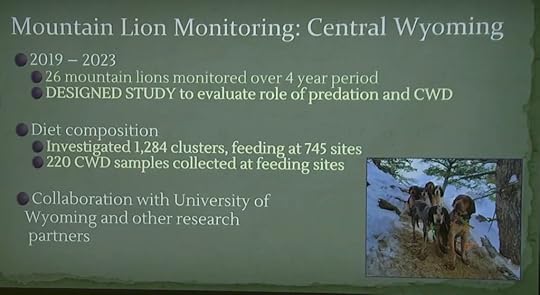

I recently attended a presentation by Wyoming Game and Fish large carnivore biologist Luke Ellsbury on, what else, large carnivores. I was mostly interested to know any results from Justin Clapp’s study on CWD and mountain lions. The field research is done but the analysis hasn’t been published yet. Luke confirmed that mountain lions were definitely targeting CWD deer and elk.

Another study measured the amount of prions in scat from mountain lions intentionally fed CWD infested deer meat. On the first defecation, the meat contained only 3% prions. And no detection on defecations after that. Luke said with these results in hand, the Service is definitely looking at adjusting mountain lion quotas in areas where they want to target reducing CWD in deer and elk. They are also planning on repeating this study with other predators—wolves and bears—and are presently testing CWD meat on bobcats in the field.

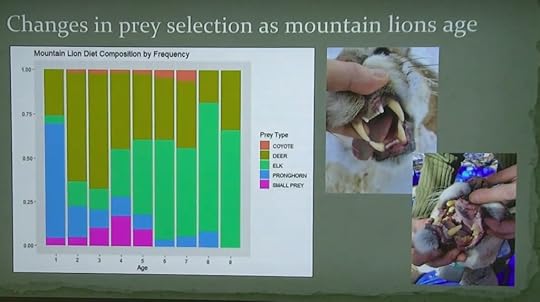

The study also corroborated findings from Elbroch’s Jackson study that as lions age they tend to prey switch to elk more heavily. That means if WGF wants to reduce elk CWD through mountain lion predation, reducing hunt quotas will allow more older mountain lions on the landscape. The critical age for prey switching seems to be five years old.

In other more personal mountain lion news, Luke confirmed for me that my one-eyed female lion was not harvested this year. In my area which is the northern end of Hunt Area 19, only one female was harvested this winter. I showed Luke the last video I captured of one of One-Eyed cubs. I thought he looked pretty rough. Luke agreed he didn’t look in good shape, confirming to me that most likely the mother and other cub are dead. And this cub, probably a male because he was always the bigger of the two cubs, isn’t likely to survive either. Cubs under one year old that lose their mother have a very low survival rate as they haven’t developed their hunting skills yet.

Lone Kitten of One-Eye captured early March 2024

Lone Kitten of One-Eye captured early March 2024Luke told me that this winter one lion was killed by wolves in my area, and that he had a call about another lion recently killed by wolves. Lions in my area aren’t collared, so these would be lions that hunters or hikers encounter and report. We’ve also had one report of a mountain lion dying of bird flu in the North Fork area of Cody.

One-Eye with her kittens during happier timesI’ll continue to check cameras and hope to see One-Eye. I’ve followed her since she arrived in my area in 2021 as a young lion. She was probably born with her blindness. This was her second litter and I thought she was going to be really successful. The last time I saw the family together, those cubs looked happy and healthy at probably around seven or eight months old. Life is definitely rough out in the wild.

Here is One-Eye in 2021 when she first arrived here as a young lion. Listen to her caterwaulingTo pre-order the expanded edition of Ghostwalker out this fall, and to be receive a 40% discount, go to https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/bison-books/9781496238474/ and enter code 6AF242021