Christopher Clarey's Blog

September 9, 2025

All on the Line

Getty/Al Bello

Getty/Al BelloNEW YORK – It’s a long-running tennis debate.

If you had to pick one man to play a match for your life, who gets the assignment?

For many years, it was obvious: Rafael Nadal with his whipping topspin, warrior spirit and unflagging commitment to each and every point.

Nadal, you could be certain, would not go down without quite a fight.

Then, true to form, Novak Djokovic strived and self-actualized his way to the head of most lines, transforming himself, with Nadal and Roger Federer for fuel, into a grand-match master, capable of locking down in the rallies and tournaments that mattered most.

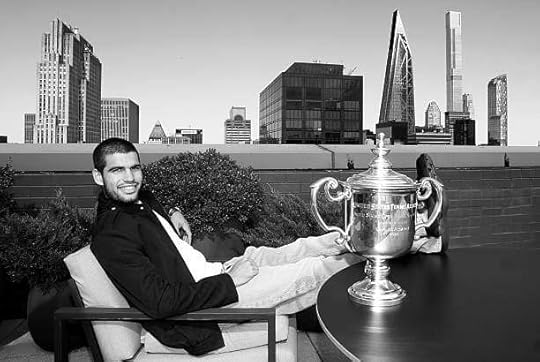

But this is Carlos Alcaraz’s time and not simply because he manhandled Jannik Sinner in Sunday’s US Open final to recover the No. 1 ranking.

It’s about more than recency bias and current form. It’s about his body of work at age 22. Though Alcaraz -- with his creative streak, crowd-pleasing instincts and shot-selection issues -- has often been viewed as less dependable than his teutonic Italian rival, he is, at this stage, clearly the best pressure player in the sport.

The proof was in his newly efficient, often clinical approach to match play in New York, where he dropped only one set and was broken just three times in the tournament with his upgraded serve setting the pace. He won more than 83 percent of his first-serve points in all but one of his seven matches. Compare that with Wimbledon, traditionally a servers’ paradise, where he was above 80 percent in only three of seven matches.

Getty

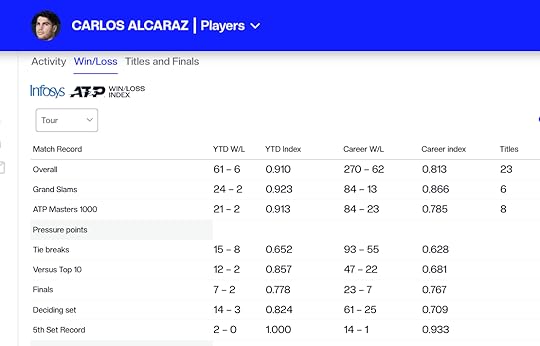

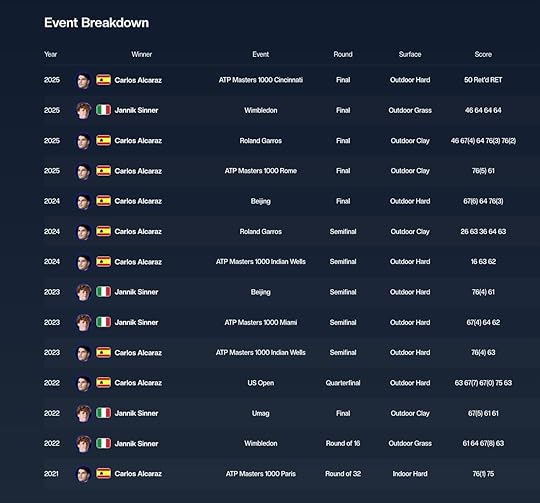

GettyBut the proof is also in the early-career numbers. Alcaraz is a glittering 6-1 in Grand Slam singles finals, the only loss coming at Wimbledon this year to Sinner. At the next tier, he is 8-1 in Masters 1000 finals, the only loss coming to Djokovic in one of the most dramatic best-of-three-set matches in memory: the 2023 Cincinnati Open final.

Sinner’s numbers are 4-2 in major finals and 4-4 in Masters 1000 finals with a 1-1 record in finals at the ATP’s year-end championships, where Alcaraz has yet to reach a final.

Their record in fifth sets is also worth considering.

Alcaraz is 14-1. Sinner is 6-10. Expand that to deciding sets, and it’s much closer, but Alcaraz still has the edge. He is 61-25 (71%). Sinner is 67-33 (67%). Both, it should be noted, remain behind Djokovic, who 218-85 (72%), but as much as I respect Djokovic’s steely will and absence of middle-aged body fat, I’m not picking a 38-year-old who has not won a major in two years to play for my life.

ATP

ATPAlcaraz has faltered on big occasions to be sure.

See the Olympic gold-medal match against Djokovic in Paris last year that left Alcaraz reeling and contributed to his second-round exit at last year’s US Open against Botic van de Zandschulp.

See his cramp-filled defeat to Djokovic in the 2023 French semis or his surprise loss in the semis to Jack Draper in Indian Wells this year when Alcaraz felt pre-match dread and played like it.

Getty/Paris Olympics

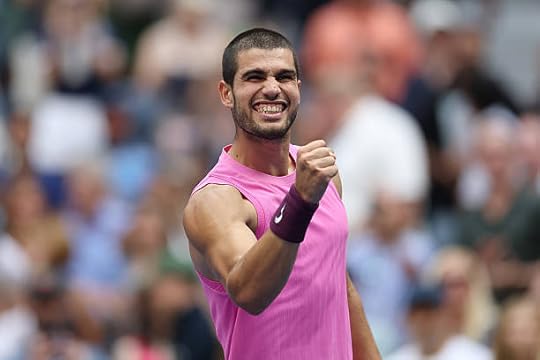

Getty/Paris OlympicsBut much more often than not, he has risen to the grand occasion, drawn to the challenge and the chance to commune with the biggest audience possible.

“His character on the court is so big,” his coach and mentor-in-chief Juan Carlos Ferrero once told me. “He loves to go for the big points and for the big moment and is one of the few guys that you can see who is like this.”

His 6-1 major final record puts him in elite company. The only men’s champion to start faster in the Open era was Federer, who went 7-0 before Nadal beat him in the 2006 French Open final.

Bjorn Borg also went 6-1 but neither Borg nor Federer quite stack up to Alcaraz’s multi-surface achievements in the majors.

Christopher Clarey's Tennis & Beyond is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

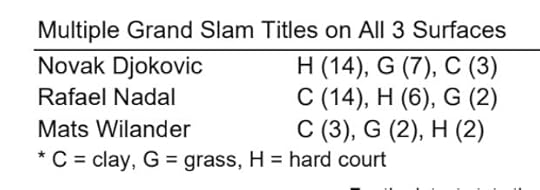

The Spanish youngster already has won two Grand Slam titles on grass, two on clay and two on hardcourts. Borg never won a hardcourt major, failing to seal the deal after the US Open went to hardcourts for good in 1978 and retiring long before the Australian Open switched to hardcourts in 1988.

Federer won his lone French Open in 2009 at age 27, although he did reach four other finals on the red clay at Roland Garros.

Getty

GettyThe only men to win multiple majors on tennis’s three different surfaces are Mats Wilander, Nadal, Djokovic and Alcaraz.

It is a club that many past greats had no chance to join. Until 1975, three of the four Grand Slam tournaments were on grass, and you have to believe that the likes of René Lacoste, Henri Cochet, Tony Trabert, Manolo Santana, Roy Emerson and Rod Laver – who all won multiple clay and grasscourt majors -- could have won plenty of hardcourt majors if given the chance. The same certainly goes for Bill Tilden and Don Budge.

US Open

US OpenBut this modern-day club reflects versatility and consistency, and if Alcaraz can continue to marry the two while keeping his health and head, he is on his way to double digits in major victories.

It has been a banner year. One of the best barometers for a dominant season is a winning percentage in the 90s. Nadal and Djokovic each managed it twice; Federer did it four times, with three straight in 2004, 2005 and 2006 before Djokovic’s emergence.

Alcaraz, with the US Open in the books, is at 91 percent for 2025 with a 61-6 singles record. Until now, his top mark in a season is 85 percent. Sustaining momentum through the fall will be a challenge, and he smartly decided to skip Spain’s Davis Cup qualifier matches this week to decompress. But it won’t be much of a rest. He is expected to return next week for the big-payday Laver Cup team event, which he enjoyed in his debut last year.

Sinner, with host and reigning champ Italy already qualified for the Davis Cup finals in Bologna, does not have to worry about this round. But he does have to worry about Alcaraz and the future.

Getty

GettyFor the second straight year, he and the Spaniard have split the majors. If Sinner had converted any of his three match points in this year’s French Open final, he could have done better than a split, although there is no telling what a tough loss in Paris might have done to Alcaraz’s motivation and results at Wimbledon.

But Sinner, to his credit and our benefit, did not sound satisfied with the status quo after his defeat in New York.

He recognized that what works against the rest of the field is not sufficient against Alcaraz. He committed himself to becoming, like his rival, more unpredictable, and not just against the Spaniard.

“For example, during this tournament, I didn’t make one serve-volley, didn’t use a lot of drop shots, and then you arrive to a point where you play against Carlos where you have to go out of the comfort zone,” Sinner said. “So I’m going to aim -- maybe even losing some matches from now on – but trying to do some changes, trying to be a bit more unpredictable as a player, because I think that’s what you have to do, trying to become a better tennis player. At the end of the day, that’s my main goal, no?”

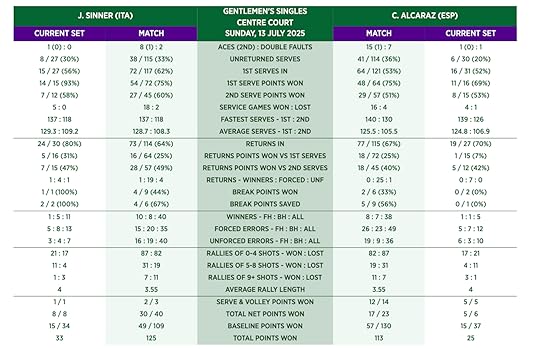

This could be more subtle than obvious: Sinner came to net nearly as often as Alcaraz on Sunday with similar success: winning 19 of 26 points compared with the Spaniard’s 20 of 27. But Sinner did change spin and pace less frequently, and even if he had wanted to drop shot more often, Alcaraz’s extreme quickness makes that quite a risk.

Though it is not easy to go against your core tennis personality, the Big Three certainly added to their games. Federer, once resistant to the drop shot, came to enjoy deploying it. Djokovic and Nadal learned to use serve-and-volley selectively but very effectively.

Getty

GettySinner, already proficient in the forecourt, surely can expand his range at age 24. But Alcaraz has been playing with great variety since his early junior years. It is part of his makeup, in line with his instincts and his understanding of how to enjoy tennis.

“The way he plays, I think it’s a little bit easier than maybe for others,” Ferrero said of the whistle-while-you-work factor.

But joy and creativity will only get you so far in pro tennis. Devastating power, extreme precision and footspeed are the trump cards, and Alcaraz put the full package on display in New York.

In the Wimbledon final, his average serve speed was about three miles per hours below Sinner’s on first and second serves. In New York, they were equal on first serve speed with Alcaraz having a two-mile-per-hour edge on the second.

At Wimbledon, Sinner had eight aces and two double faults while Alcaraz had 15 aces and seven doubles. In New York, Sinner had two aces and four doubles. Alcaraz had 10 aces and zero doubles and won significantly higher percentages of points than Sinner on both of his serves and when returning both of Sinner’s serves.

In my eyes, it was an off day for the Italian, full of imprecision and uncharacteristic errors. He had 18 groundstroke winners in the Wimbledon final; just seven in the US Open final. The forehand battle, often a spectacularly fair fight, was a rout in New York, with Sinner producing just two forehand groundstroke winners to Alcaraz’s 14. The Spaniard’s form certainly was the main factor.

“I felt like he was a bit cleaner today,” Sinner said. “The things I did well in London, he did better today. I felt like he was doing everything slightly better today, especially serving, both sides, both swings very clean.”

Though there was considerable resistance to this on social media when I suggested it early in the final, there might even have been a minor physical issue in play for Sinner despite his team’s denials. He was treated for an abdominal muscle issue during the semifinals.

If true, it would take little away from Alcaraz’s achievement. The sport is about managing the rigors of a nearly year-round schedule and staying healthy enough to compete, and Alcaraz, let’s not forget, also had a wrap around his right thigh during the final.

Playing with pain is part of pro tennis, as Nadal, Djokovic and Federer would confirm. So is playing with big-match pressure, and Alcaraz is doing that better than anyone in the men’s game.

Sign him up.

CC

Getty

Getty

September 7, 2025

Justice is Served

Getty

GettyNEW YORK – Aryna Sabalenka is full of life and mirth. A US Open champion anew on Saturday, she played a drum solo with her palms on her fitness trainer Jason Stacy’s bald pate, where, in honor of his employer, he had affixed a temporary dragon tattoo.

Talking with Sloane Stephens on the ESPN set, she made plain her celebration plans -- “Oh girl, we’re gonna drink!” -- then arrived at her news conference with a bottle of Champagne in hand and protective goggles perched on her forehead.

“Cheers, guys!” she said at one merry stage.

But she knows the dark side, too.

September 6, 2025

Duopoly

Getty/Clive Brunskill

Getty/Clive BrunskillNEW YORK – Let’s start with the remarkable photograph above to remind ourselves what we are dealing with.

Novak Djokovic is close to 40 years old, competing against players like Carlos Alcaraz, who was not born when he turned professional. And yet the Serbian, with flecks of gray in his hedgehog hair, is still able to take flight and contort himself into ball-striking positions that would leave most of his actual peers in need of physical therapy.

He is a marvel and an outlier among outliers, the most successful men’s tennis champion of the Open era and forever on the short list of the greatest players of all time. But he is not going to win any more major singles titles, as this season has made abundantly clear.

Friday provided the latest evidence as he ran out of steam and solutions against Alcaraz, falling in straight sets in the semifinals of the US Open, which remains the last place where Djokovic won a Grand Slam title.

That was in 2023, a year when he took three of the four majors, only losing in five sets to Alcaraz in a thriller at Wimbledon.

But since that season, Djokovic has won just two titles: the Olympic gold in Paris and an ATP 250 in Geneva, bringing his career total in singles to a nice round 100. The desire to conquer may still be there, but the total commitment is not. He is playing a limited schedule, and it is difficult to see him changing that with a young family and a body in constant need of care and repair. Even with total commitment, the power dynamic has shifted for good. Alcaraz and Jannik Sinner now rule.

“They’re just too good, you know, playing on a really high level,” Djokovic said after Alcaraz’s 6-4, 7-6 (4), 6-2 victory on Friday. “Unfortunately, I ran out of gas after the second set. I think I had enough energy to battle him and to keep up with his rhythm for two sets. After that I was gassed out, and he kept going. That's kind of what I felt this year also with Jannik. Yeah, best-of-five makes it very, very difficult for me to play them. Particularly if it’s like the end stages of the Grand Slam.”

Djokovic, who said he intends to play on, has often looked down and out in big matches during his career, only to revive and find a way: see the classic 2012 Australian Open marathon versus Rafael Nadal.

Getty

GettyBut appearances were not deceiving on Friday as he gasped for breath between rallies and leaned on the towel box, his features drawn and his signature returns off target when he needed them most. He has hit many a brilliant shot on the full stretch over the last 20 years, shoes squeaking as he transformed defense to offense out of a near split. But he was late to the ball and the target too often on Friday, particularly on his forehand wing.

“Of course, it's frustrating on the court when you are not able to keep up with that level physically, but at the same time, it's something also expected, I guess,” Djokovic said. “It comes with time and with age.”

Christopher Clarey's Tennis & Beyond is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

He is still, at 38, the third best men’s player in the world. The rankings don’t reflect it – he will be No. 4 on Monday -- but his major tournament results certainly do. And though 2025 will hardly go down as his annus optimus it is a remarkable achievement to reach the semifinals in all four Grand Slam events at this late stage of the game.

“Impressive,” Alcaraz said of Djokovic after his 6-4, 7-6 (4), 6-2 victory. “Challenging the Next Gen, challenging us, the way he’s doing it is impressive. I tell him always he looks like 25 years old physically.”

What is missing is the 25-year-old’s staying power. And yet the only other players to reach the final four in all majors this season are Sinner, who is No. 1 and about to face Alcaraz for the US Open men’s title, and Aryna Sabalenka, who is No. 1 and just defeated Amanda Anisimova for the women’s title.

There is of course another way to look at Djokovic’s continued success as a part-timer. It shows how steep the dropoff is after Sinner and Alcaraz. For me it is more about their brilliance — and Djokovic’s skill and drive — than their pursuers’ mediocrity. Their rise has been demoralizing to establishment figures who expected their turn to come after the Big Three: see Daniil Medvedev, Alexander Zverev, Stefanos Tsitsipas et al.

Sinner’s and Alcaraz’s consolidation of power has to be daunting to their own generation who know how much they will have to lift to join the conversation, how much they will have to stretch and strain to maximize their own talent (let’s all send good vibes to Ben Shelton’s left shoulder).

Sinner and Alcaraz are the total packages, capable of imposing a torrid pace that the pack, for now, cannot follow.

Getty

GettySinner is relentless; Alcaraz less reliably on task. But they both possess a top gear that only the other can match, and this will be the eighth straight major where one of them will walk away as the champion.

The Big Three raised the bar on longevity, no doubt, but in traditional tennis terms, this is already an era. Bjorn Borg and John McEnroe played all their Grand Slam finals against each other over two years: 1980 and 1981. Boris Becker and Stefan Edberg played all of theirs over three: 1988, 1989 and 1990.

At this stage, it is hard to imagine that Alcaraz, age 22, and Sinner, age 24, will not extend their rivalry over a considerably longer span.

But injury and ennui can spring surprises, so it is best to relish what we have while we have it: a third straight Grand Slam final between sparkling talents who can do damage from just about anywhere and who have shown a welcome propensity for bringing out the best in each other.

Thanks for reading Christopher Clarey's Tennis & Beyond! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Their rivalry already has quantity and quality. This will be their 15th tour-level meeting: one more than Borg and McEnroe.

ATP

ATPOf those 15 matches, seven, in my view, have been genuinely special with the 2022 US Open quarterfinal and 2025 French Open final the standouts.

Both went five sets and over five hours, and Alcaraz won them both after facing match point: he saved one in New York and three in Paris.

Alcaraz holds a 9-5 edge over his elder and has won six of their last seven matches, including last month’s anticlimactic final in Cincinnati when Sinner, ill and suffering in the heat, tapped out before the end of the first set.

He, not Alcaraz, remains the hardcourt master until proven otherwise: winning the last two Australian Opens and last year’s US Open. His short-hop timing from the baseline is unmatched, and he has improved his explosive moment and endurance. He is not as balletic and obviously acrobatic as Alcaraz, but he can get so low at 6-foot-3 and create so much racket-head speed with his whipping groundstrokes.

In real time, his forehand looks flat but slow it down on a replay and you can see how much topspin he is generating to go with the pace. That explains the late dip as his shots near their target: a dip that so often surprises the opposition.

Getty/Matthew Stockman

Getty/Matthew StockmanBut Alcaraz gets my nod this time.

Unlike Sinner, he has not dropped a set coming into the final: a first for him at a major. He looks fresher physically and is perhaps healthier considering that Sinner needed treatment off court on Friday for a possible abdominal strain during his surprisingly rugged four-set semifinal victory over an inspired Felix Auger-Aliassime.

Sinner has been broken four times in the tournament; Alcaraz just twice, and the Spaniard seems now to have fully assimilated the changes to his serving motion. He has won 84 percent of his first-serve points here, putting 63 percent in play. Sinner, typically the better server, is at 82 percent and 57 percent.

Fine margins to be sure, and Sinner has been the more devastating force when returning, particularly against second serves, winning 65 percent of the points to Alcaraz’s 56.

If Sinner is fit, it should again be close, very close, and there is more at stake than a US Open title. The winner will be No. 1 come Monday. Whoever rules, spare a thought, or something more expansive, for the former king, who spent a record 428 weeks in the top spot before time and the new wave of tennis geniuses caught him from behind.

CC

Getty

Getty

September 4, 2025

All Out of Bagels

Getty

GettyNEW YORK – What a difference 53 days makes.

After freezing in the white-hot spotlight of the Wimbledon final, Amanda Anisimova rose to the occasion on Wednesday at the US Open, taking down Iga Swiatek, the same serial champion who had routed her 6-0 6-0 at the All England Club.

Seeing Anisimova swing away and do justice to her talent was reassuring for anyone who sat through that July mismatch, which was more implosion than demolition; an anticlimax that was gripping only for its unlikely storylines.

Was Swiatek, long suffering on grass, really going to win Wimbledon with a double bagel and barely a tussle? Was Anisimova, triumphant against No. 1 Aryna Sabalenka in the semifinals, truly not going to win a single game on the same patch of well-tended grass?

Though the 57-minute humiliation could easily have left Anisimova reeling for months (or seasons), she has instead roared back just a few weeks later in New York: reaching her first US Open semifinal -- and a matchup with Naomi Osaka -- by showcasing her fearsome easy power, elite backhand, bold returns and resilience.

Anisimova literally stared down her demons: forcing herself to watch a replay of the Wimbledon final the night before facing Swiatek in New York.

What did she see on screen?

July 16, 2025

Images from Wimbledon 2025

Taylor Fritz pumps up/Henry Nicholls of AFP via Getty

Taylor Fritz pumps up/Henry Nicholls of AFP via GettyLONDON — It was a sunbaked Wimbledon, more like the Australian Open than the buttoned-up Grand Slam tournament where rain has been delaying play since the 1800s.

This time around, fans fluttered fans in the Royal Box, and ice towels were must-have accessories on changeovers for the stars, including Jannik Sinner, the first Italian to win the Wimbledon singles title.

The photographers, as usual, stayed cool under pressure. Here are some of their shots that will stay with me:

Julian Finney/Getty Images

Julian Finney/Getty ImagesAfter the upsets.

July 13, 2025

Forgetting Paris

Getty

GettyWIMBLEDON – Pop!

It was early in the second set of the Wimbledon final, and perhaps a reveler in the Centre Court crowd knew something that Jannik Sinner and Carlos Alcaraz did not.

The Champagne cork flew far enough to land on the grass below, just a few paces from where Sinner was preparing to serve. I have never seen anything quite like it in all my years of covering Grand Slam finals, but the Italian, a ball still in his left hand, calmly plucked the projectile off the lawn with two fingers and handed it to a ball girl for disposal.

“Only here at Wimbledon,” Sinner said. “It’s an expensive tournament.”

Getty

GettyAt the time, a Sinner celebration at the All England Club was far from a sure thing. He was already down a set to Alcaraz, the same acrobatic and improvisational Spaniard who had beaten him five times in a row, canceling Sinner’s victory party in Paris last month by saving three match points and winning the French Open in five thrill-filled sets.

But Sinner was about to prove on Sunday that his dramatic Roland Garros setback did not break his spirit. Quite the contrary. It taught him valuable lessons, one of which was to seize the day before Alcaraz seized it instead. Holding back and waiting for an error would not get this job done.

“Today’s match, I think, was a match of moments,” said Darren Cahill, one of Sinner’s coaches. “Of just who was going to step up in the big moment and make something happen. At Roland Garros, it was Carlos, and today it was Jannik. So we could not be more proud of him.”

Sinner looked pretty pleased himself as he finished off this bounceback 4-6, 6-4, 6-4 6-4 victory, thrusting his long arms into the air after his final big first serve down the T sealed the deal on his second championship point.

Getty

GettyHe could have cracked after losing a 4-2 lead in the opening set. He could have cracked when it came time to serve for the second, or the third, or the match.

Nothing doing. He was as cool as the snow that covers his hometown of Sexten in the Dolomites in winter.

“I had a very tough loss in Paris,” he said, with the gilded Wimbledon men’s singles trophy glittering in his grasp. “But at the end of the day it doesn’t matter how you win or you lose, especially important tournaments. You just have to understand what you did wrong and try to work on that, and that’s exactly what we did. We tried to accept the loss and just kept working, and that is for sure one of the reasons why I hold this trophy here.”

He is the first Italian to win a Wimbledon singles title, succeeding where Matteo Berrettini and Jasmine Paolini came up just short in recent years. But then Sinner, still only 23 years old, is already the most successful Italian tennis player ever.

He has been No. 1 for 57 weeks and counting and now has four major singles titles: two Australian Opens, one US Open and one Wimbledon, which is his first on a surface other than hardcourt. If not for Alcaraz’s great escape in Paris, Sinner might well have been in position to aim for the true Grand Slam — the calendar-year Grand Slam — in New York this year. But we will of course never know how the pressure that goes with that quest might have affected him at Wimbledon.

Christopher Clarey's Tennis & Beyond is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Sinner once risked not being here at all. His three-month ban for a doping violation, served earlier this year, came after the World Anti-Doping Agency appealed a ruling by an arbitration panel that had imposed no suspension. WADA initially said it was seeking “a period of ineligibility of between one and two years” with its appeal. Instead, it backed away from that, entered into negotiations with Sinner’s legal team, and imposed a shorter ban whose timing did not require him to miss any majors.

Once at Wimbledon, things also fell Sinner’s way. He was two sets down to Grigor Dimitrov in the fourth round when Dimitrov tore a pectoral muscle and had to retire at 2-2 in the third.

“The way Grigor was playing, if he continued to play at that level, then he was a good chance to close it out,” Cahill said. “But we in the box always had faith that Jannik was going to get himself out of that match. But yes, he caught a break. We kept reiterating to him that a Grand Slam, in men’s tennis, it’s seven matches best-of-five. Nobody goes through a tournament without a hiccup, whether it be an injury or a little bit of luck or you get yourself out of an early-round problem. Everybody has a story in a Grand Slam. Maybe this was going to be his story.”

So it turned out. Sinner never had to save a match point at this Wimbledon, never even got pushed to a fifth set, but it did feel like he had been given a second chance at splendor on the grass.

He capitalized yet did so the hard way: beating Novak Djokovic, a seven-time Wimbledon champion, in the semifinals and then Alcaraz, the two-time defending champion. Between them, Djokovic and Alcaraz had won the last six editions of the tournament, and Alcaraz was on a 20-match winning streak at the All England Club.

“You cannot win all the time,” Alcaraz said. “You have to accept that the other player sometimes can do much better than you.”

Thanks for reading Christopher Clarey's Tennis & Beyond! This post is public so feel free to share it.

Alcaraz could and should have some regrets, however. He and Sinner both came into the final putting 63 percent of their first serves in play. Sinner essentially maintained that on Sunday, finishing at 62 percent for the final, but Alcaraz slipped to 53 percent. That allowed Sinner too many chances to do what he does best -- return second serves – and he won nearly half of those points.

“I played against one of the best returners on tour, without a doubt,” Alcaraz said. “With the nerves and everything, it was difficult to serve better. I just have to improve that, yeah, absolutely.”

IBM

IBMAlcaraz also missed some critical returns in his wheelhouse and probably should have found a way to spend more time at net, considering Sinner’s baseline prowess and Alcaraz’s phenomenal touch in the forecourt. The Spaniard won 12 of 14 serve-and-volley points, a tactic that has been a successful niche play for him during his reign at Wimbledon. But another of his signatures, the drop shot, was not as consistently effective on Sunday, even if he twice brought Sinner to his knees: the Italian slipping behind the baseline as he tried to push off and give chase.

But Sinner did not stay down for long, and this young rivalry is now even more irresistible. Lose on Sunday and Sinner would have trailed 3-6 in Grand Slam titles. Instead it is 4-5 heading into the US Open, a major that both men have won once but where Sinner will likely be the favorite given his hardcourt prowess.

“Today was important for many, many reasons,” Cahill said. “Jannik needed that win today, so he knew the importance of closing this one out when he had the opportunities. With that, I think you saw a bit more energy from him in the big moments and a bit more focus to knuckle down and make sure that when he had his nose in front that he kept closing the door against Carlos.”

Sinner slammed shut the second set with a brilliant, bold game that featured three groundstroke winners, including a backhand off the slide on the opening point after he tracked down a fine Alcaraz drop volley.

Serving at 2-3 in the third, Sinner shrugged off missing an overhead after making a highlight-reel reflex volley between the legs and finished off the hold with an ace. At 3-4, Alcaraz got to 30-all on Sinner’s serve with a drop-lob combination but Sinner came up with a second-serve ace wide on the next point and then a first-serve ace wide to hold before breaking Alcaraz in the next game.

Getty

GettyIn the fourth, Sinner broke Alcaraz in the third game with consecutive backhand winners down the line, the last a bolt of a return off a second serve. Sinner maintained that slim edge, fighting off two more break points from 15-40 in the eighth game.

That put the Italian up two sets to one and 5-3, the same lead he had held and surrendered at Roland Garros. Watching from the press seats, it was impossible not to wonder if Sinner was as acutely aware of the symmetry. But while Alcaraz did hold to 5-4, Sinner put an end to the parallels by jumping out to a 40-0 lead and finishing off the victory two points later.

What happens in Paris apparently stays in Paris, and Alcaraz was soon offering his warm congratulations to Sinner at the net. They are, for now and maybe much longer, friendly rivals: taking their cue from Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal, the last men to play in back-to-back French Open and Wimbledon finals.

Like Federer and Nadal for much of the 2000s, Sinner and Alcaraz are a duopoly. A third man, Djokovic, changed the power structure for Federer and Nadal, and a third or fourth man could do the same again in the 2020s.

“The rivalry I think is amazing already, and I think it can get better with both these players pushing each other,” Cahill said. “I do think there’s some other younger players coming through that will punch their way through the door, so it won’t just be a two-man show.”

Perhaps Jack Draper, Jakub Mensik, Ben Shelton, Lorenzo Musetti, Arthur Fils or Joao Fonseca. Perhaps someone even younger still working his way up to the tour. But for now Sinner and Alcaraz are hoarding the loot. They have combined to win seven majors in a row, and on Sunday evening, it was Sinner’s turn to show off the spoils on the balcony of the All England Club to the cosmopolitan throng gathered below.

It is one of the most stirring views in sports, and when Sinner returned indoors, Sally Bolton, the club’s chief executive, respectfully informed the new champion (and new club member) that she would need to repossess the trophy but that he would soon be given the customary replica.

“No rush,” Sinner said politely. “But I would like to have it.”

Until then, Champagne all around.

CC

Getty

Getty

July 12, 2025

Bagels at Wimbledon

Getty

GettyWIMBLEDON – A light breeze. Sunshine in abundance.

It was a beautiful day for an outing in London, perhaps a picnic by the Thames or a long, leisurely Saturday stroll through Kew Gardens.

A beautiful day, too, for a Wimbledon final, but the match did not meet the moment as Iga Swiatek, long tennis’s baker in chief, double-bageled American Amanda Anisimova to win her first Wimbledon women’s title.

It required just 57 minutes: not much value for money considering the price and scarcity of Wimbledon tickets. It was the first 6-0, 6-0 victory in a major final since Steffi Graf’s demolition of Natasha Zvereva at the 1988 French Open; the first 6-0, 6-0 victory in a Wimbledon singles final since the pre-war era and we’re talking about World War I, not World War II.

If you’re going to lose big, you might as well make history, but that is surely too flippant. It was a struggle to see the lighter side on Saturday as you sat in Centre Court watching the gifted Anisimova, who has been through so much in her 23 years, struggle unremittingly with nerves, missing again and again (and again). Sports is entertainment after all, and this was often as much fun as watching a youngster forget their lines in a school play.

It was very tempting to avert the gaze no matter how lovely the stretch of lawn below, but that would have been a disservice to Swiatek, who was rising to the occasion as much as Anisimova was sinking beneath the weight of it.

One-Way Traffic at Wimbledon

Getty

GettyWIMBLEDON – A light breeze. Sunshine in abundance.

It was a beautiful day for an outing in London, perhaps a picnic by the Thames or a long, leisurely Saturday stroll through Kew Gardens.

A beautiful day, too, for a Wimbledon final, but the match did not meet the moment as Iga Swiatek, long tennis’s baker in chief, double-bageled American Amanda Anisimova to win her first Wimbledon women’s title.

It required just 57 minutes: not much value for money considering the price and scarcity of Wimbledon tickets. It was the first 6-0, 6-0 victory in a major final since Steffi Graf’s demolition of Natasha Zvereva at the 1988 French Open; the first 6-0, 6-0 victory in a Wimbledon singles final since the pre-war era and we’re talking about World War I, not World War II.

If you’re going to lose big, you might as well make history, but that is surely too flippant. It was a struggle to see the lighter side on Saturday as you sat in Centre Court watching the gifted Anisimova, who has been through so much in her 23 years, struggle unremittingly with nerves, missing again and again (and again). Sports is entertainment after all, and this was often as much fun as watching a youngster forget their lines in a school play.

It was very tempting to avert the gaze no matter how lovely the stretch of lawn below, but that would have been a disservice to Swiatek, who was rising to the occasion as much as Anisimova was sinking beneath the weight of it.

July 11, 2025

Another Major Moment

Getty

GettyWIMBLEDON – As Amanda Anisimova handled the pressure and No. 1 Aryna Sabalenka at Wimbledon to reach her first Grand Slam final, I flashed back to a time before Anisimova had played any Grand Slam tournaments.

She was 15, and I caught a plane to Miami on short notice to spend a day with her and her parents for The New York Times ahead of her trip to Paris. She had secured a reciprocal wildcard into the main draw of the 2017 French Open by doing better than her American elders in a series of spring tournaments.

I was intrigued by her precocity: She was about to become the youngest player in 12 years to compete in singles at Roland Garros.

I was intrigued by her backstory: The youngest daughter of Russian immigrant parents, she had developed her game in Florida and then decided to represent the USA instead of sticking, Sharapova-style, with Russia.

As a Springsteen fan, I was also intrigued by her birthplace: Freehold, N.J., Springsteen’s hometown, even if I soon learned that Anisimova and her family had actually lived in nearby Colts Neck.

Anisimova at 15 was tall, blonde and leggy: already 5-foot-10. Though she spoke softly and carefully, her two-handed backhand was even then a force of nature, and she was happy to share her big dreams, however sotto voce.

“I definitely want to become No. 1 in the world and win every Grand Slam,” she told me at her family’s apartment in Aventura, Fla.. “One of each would be, like, super awesome. I hope to do that one day.”

Eight years later, she is on the brink of winning her first major and guaranteed to break into the top 10 for the first time with her run at Wimbledon. It has hardly come easy. Her career has been an all-in family project from the start, and her father and longtime primary coach Konstantin died suddenly of a heart attack in August 2019 at age 52. That was a colossal blow to Anisimova, who was 17 and had just reached the semifinals of the French Open. Though she soon returned to the tour, she took an eight-month break from competition in 2023 for her mental health. She was burned out and depressed and found it “unbearable” to be at tournaments.

For the first time since starting to play at age 2, she put the racket aside and lived a more conventional existence: attending university classes in person and prioritizing friends and her social life.

Though she says now that she intended to return to the circuit, Max Eisenbud, her agent at IMG who also represents Sharapova and Li Na, was far from certain.

“When someone takes nearly a year off like that, you don’t know if they’re going to come back or want to come back or can they play at this level?” he said recently. “So, I’m very proud of her.”

“I think we’ve all known her level is top five in the world. She’s so good, It’s just all the other things around her, but just on a personal level for a client I’ve managed for a long time, I’m happy to see she’s happy. At the end of the day, that’s all you can ask for, and if she’s also winning tennis matches that’s great. And honestly, if she doesn’t want to play tennis and she’s happy, that’s good too.”

Christopher Clarey's Tennis & Beyond is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

It is all coming together in 2025, a season in which Anisimova won her first WTA 1000 title in Doha and has found sparkling form again on the grass, reaching the final at Queen’s Club before losing to veteran slicemeister Tatjana Maria and now getting to the title match at the Big W.A

Anisimova’s easy power, penetrating serve and relatively flat, fluid groundstrokes are a great fit for grass, just as they were for Lindsay Davenport, the towering American ball-striker supreme to whom Konstantin often compared his daughter. Like Davenport, a former No. 1 and Wimbledon champion, Anisimova will never be a speedster, but she has improved her court coverage and ability to recover quickly out of the corners.

Davenport 1999

Davenport 1999Anisimova, still just 23, has had star coaches in her career, including Nick Saviano, Carlos Rodriguez and, for a very brief period, Darren Cahill. But she has managed this renaissance with a lower-profile team: coach Rick Vleeshouwers, strength and conditioning coach Rob Brandsma and physiotherapist Shadi Soleymani.

Brandsma worked with Anisimova before her long break from the game and returned to her team after splitting with Chinese star Zheng Qinwen last year. He recommended Vleeshouwers, who had coached Belgian stars Elise Mertens and Yannick Wickmayer. Soleymani, who worked with Zheng during her run to the Australian Open final and Olympic singles gold in 2024, joined Anisimova’s team in April.

Instagram. Left to Right: Soleymani, Brandsma, Vleeshouwers, Anisimova

Instagram. Left to Right: Soleymani, Brandsma, Vleeshouwers, AnisimovaAll that stands between them and a first major is former No. 1 Iga Swiatek, and though Swiatek has never been this deep at Wimbledon either and has not won a title in over a year, she deserves to be the favorite. She has a 5-0 record in Grand Slam finals and has been dynamic and convincing on the grass, which has long been her least favorite surface despite her Wimbledon girls title. She is serving particularly well, holding 90 percent of the time, the best rate of any woman who reached the second week.

Though she and Anisimova have known each other for nearly a decade, they have never played on tour. They faced off only as juniors, with Swiatek defeating Anisimova in straight sets in Poland’s win over the United States in an international team competition, junior Fed Cup, in 2016.

“She was a great junior,” Anisimova said. “I remember a lot of coaches were saying that she’s going to be a big deal one day. Obviously they were right.”

Others were saying much the same about Anisimova at 15, including veteran coaches like Saviano and Martin Blackman who had seen many a prodigious prospect and learned to be cautious.

Thanks for reading Christopher Clarey's Tennis & Beyond! This post is public so feel free to share it.

“Amanda is a very special player,” said Blackman, then the general manager for player development at the United States Tennis Association.

“The ball kind of explodes off her racket,” said Saviano. “So she tends to hit a lot of winners naturally when just hitting normal groundstrokes. But she also has the will and determination to be someone who wants to be absolutely as good as they can possibly be.”

Though Anisimova’s mother Olga taught her the fundamentals until Amanda was 7, the family relied heavily for her early development on Saviano, a gifted technician who has worked with Genie Bouchard and Sloane Stephens and many others.

The Anisimovs had a clear plan, one they developed, as is often the case in tennis families, by learning from their eldest child’s career.

Amanda’s only sibling, Maria Egee, is 13 years older and played tennis in the Ivy League at the University of Pennsylvania, a remarkable feat considering that she started playing the game at age 11. She has gone on to a notable career in finance as a vice president at Goldman Sachs and a director of credit trading at Bank of America before joining Loop Capital in Miami.

Getty/Maria Egee, at this year’s Wimbledon, is in the upper left corner

Getty/Maria Egee, at this year’s Wimbledon, is in the upper left cornerMaria and her parents moved to the United States in 1998 during a financial crisis in Russia (Konstantin told me he and his wife both worked in the banking sectors). Maria was 10 and none of the family spoke much English. Konstantin told me they had seriously considered moving to Spain but had decided at that stage in world affairs that there was more opportunity in the U.S. and more chance to truly assimilate.

“We really like Spain, but then we recognized when we visited America that everybody who comes here is going to feel like home,” he said. “In Europe, you always feel like a foreigner because it’s a completely different culture. America is a united country where people come from all over the world, and after a couple of years, they feel this is home, you know?”

Amanda was born in 2001 and was soon mimicking her much older sister’s strokes with a miniature racket as she watched from courtside. The family relocated to Florida in 2004 for the weather and to help advance Maria’s tennis career, but it was Amanda’s tennis that benefited most. She was home-schooled from an early age, and Olga started teaching tennis to other youngsters in the area in part so that Amanda would have a circle of peers.

“We didn’t want to take her whole childhood away from her,” Maria told me in an interview for the New York Times in 2020. “It was important to have regular social interactions, so mom had lessons for kids and Amanda would train on the court next to them, and all the lunch breaks and pool time and interactions after that, they would be together. Some of her best friends are still people she met at that time, but I was watching the kids and just knew Amanda was different and special. I never met anyone that age that had that work ethic and maturity level. She is also just physically very gifted.”

Maria, who sometimes served as a sparring partner, also sensed the strong will of her mother.

“You could tell she was willing to sacrifice her whole life for my sister to have this American dream, which is actually a world dream,” Maria said. “I had faith in them. Never a doubt in my mind.”

Konstantin, a strapping and expansive man, also played a crucial role. During our interviews, he seemed attuned to the pitfalls of raising a child prodigy, particularly after early success.

“I saw a lot of parents who got immediately delusional, and those stories end up in a very bad way,” he said. “You can’t overtrain. You can’t over-push.”

Konstantin and Amanda in 2017/Getty

Konstantin and Amanda in 2017/GettyHe was intent on Amanda avoiding burnout. Sadly, it happened anyway, even though he did not live to see it. He and Olga separated in 2018 but remained on good terms, according to Maria. He died at their home in Aventura when Amanda was in New York preparing for the 2019 US Open with Olga.

Amanda withdrew from the Open, and I traveled to Florida again later that year to meet with her ahead of the 2020 season.

“This is obviously the hardest thing I’ve had to go through and the hardest thing that’s ever happened to me, and I don’t really talk about it with anyone,” she said then. “The only thing that has helped me is just playing tennis and being on the court. That’s what makes me happy, and I know it would make him happy, so that’s the way it is.”

At that stage, she was already a Grand Slam semifinalist, losing to Ashleigh Barty in Paris in 2019. It has taken another six years for Anisimova to go one step further at a major, and it has been poignant to watch her not only fulfilling her potential at Wimbledon but reveling in it: beaming in the sunshine or tumbling to the grass after her nervy victory over Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova in the quarterfinals and then celebrating with Maria’s young son Jackson in tow.

“When I took my break, a lot of people told me that you would never make it to the top again if you take so much time away from the game,” Anisimova said. “That was a little hard to digest, because I did want to come back and still achieve a lot and win a Grand Slam one day. Just me being able to prove that you can get back to the top if you prioritize yourself, that's been incredibly special to me.”

CC

Another Major Moment in the Sun

Getty

GettyWIMBLEDON – As Amanda Anisimova handled the pressure and No. 1 Aryna Sabalenka at Wimbledon to reach her first Grand Slam final, I flashed back to a time before Anisimova had played any Grand Slam tournaments.

She was 15, and I caught a plane to Miami on short notice to spend a day with her and her parents for The New York Times ahead of her trip to Paris. She had secured a reciprocal wildcard into the main draw of the 2017 French Open by doing better than her American elders in a series of spring tournaments.

I was intrigued by her precocity: She was about to become the youngest player in 12 years to compete in singles at Roland Garros.

I was intrigued by her backstory: The youngest daughter of Russian immigrant parents, she had developed her game in Florida and then decided to represent the USA instead of sticking, Sharapova-style, with Russia.

As a Springsteen fan, I was also intrigued by her birthplace: Freehold, N.J., Springsteen’s hometown, even if I soon learned that Anisimova and her family had actually lived in nearby Colts Neck.

Anisimova at 15 was tall, blonde and leggy: already 5-foot-10. Though she spoke softly and carefully, her two-handed backhand was even then a force of nature, and she was happy to share her big dreams, however sotto voce.

“I definitely want to become No. 1 in the world and win every Grand Slam,” she told me at her family’s apartment in Aventura, Fla.. “One of each would be, like, super awesome. I hope to do that one day.”

Eight years later, she is on the brink of winning her first major and guaranteed to break into the top 10 for the first time with her run at Wimbledon. It has hardly come easy. Her career has been an all-in family project from the start, and her father and longtime primary coach Konstantin died suddenly of a heart attack in August 2019 at age 52. That was a colossal blow to Anisimova, who was 17 and had just reached the semifinals of the French Open. Though she soon returned to the tour, she took an eight-month break from competition in 2023 for her mental health. She was burned out and depressed and found it “unbearable” to be at tournaments.

For the first time since starting to play at age 2, she put the racket aside and lived a more conventional existence: attending university classes in person and prioritizing friends and her social life.

Though she says now that she intended to return to the circuit, Max Eisenbud, her agent at IMG who also represents Sharapova and Li Na, was far from certain.

“When someone takes nearly a year off like that, you don’t know if they’re going to come back or want to come back or can they play at this level?” he said recently. “So, I’m very proud of her.”

“I think we’ve all known her level is top five in the world. She’s so good, It’s just all the other things around her, but just on a personal level for a client I’ve managed for a long time, I’m happy to see she’s happy. At the end of the day, that’s all you can ask for, and if she’s also winning tennis matches that’s great. And honestly, if she doesn’t want to play tennis and she’s happy, that’s good too.”

Christopher Clarey's Tennis & Beyond is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

It is all coming together in 2025, a season in which Anisimova won her first WTA 1000 title in Doha and has found sparkling form again on the grass, reaching the final at Queen’s Club before losing to veteran slicemeister Tatjana Maria and now getting to the title match at the Big W.A

Anisimova’s easy power, penetrating serve and relatively flat, fluid groundstrokes are a great fit for grass, just as they were for Lindsay Davenport, the towering American ball-striker supreme to whom Konstantin often compared his daughter. Like Davenport, a former No. 1 and Wimbledon champion, Anisimova will never be a speedster, but she has improved her court coverage and ability to recover quickly out of the corners.

Davenport 1999

Davenport 1999Anisimova, still just 23, has had star coaches in her career, including Nick Saviano, Carlos Rodriguez and, for a very brief period, Darren Cahill. But she has managed this renaissance with a lower-profile team: coach Rick Vleeshouwers, strength and conditioning coach Rob Brandsma and physiotherapist Shadi Soleymani.

Brandsma worked with Anisimova before her long break from the game and returned to her team after splitting with Chinese star Zheng Qinwen last year. He recommended Vleeshouwers, who had coached Belgian stars Elise Mertens and Yannick Wickmayer. Soleymani, who worked with Zheng during her run to the Australian Open final and Olympic singles gold in 2024, joined Anisimova’s team in April.

Instagram. Left to Right: Soleymani, Brandsma, Vleeshouwers, Anisimova

Instagram. Left to Right: Soleymani, Brandsma, Vleeshouwers, AnisimovaAll that stands between them and a first major is former No. 1 Iga Swiatek, and though Swiatek has never been this deep at Wimbledon either and has not won a title in over a year, she deserves to be the favorite. She has a 5-0 record in Grand Slam finals and has been dynamic and convincing on the grass, which has long been her least favorite surface despite her Wimbledon girls title. She is serving particularly well, holding 90 percent of the time, the best rate of any woman who reached the second week.

Though she and Anisimova have known each other for nearly a decade, they have never played on tour. They faced off only as juniors, with Swiatek defeating Anisimova in straight sets in Poland’s win over the United States in an international team competition, junior Fed Cup, in 2016.

“She was a great junior,” Anisimova said. “I remember a lot of coaches were saying that she’s going to be a big deal one day. Obviously they were right.”

Others were saying much the same about Anisimova at 15, including veteran coaches like Saviano and Martin Blackman who had seen many a prodigious prospect and learned to be cautious.

Thanks for reading Christopher Clarey's Tennis & Beyond! This post is public so feel free to share it.

“Amanda is a very special player,” said Blackman, then the general manager for player development at the United States Tennis Association.

“The ball kind of explodes off her racket,” said Saviano. “So she tends to hit a lot of winners naturally when just hitting normal groundstrokes. But she also has the will and determination to be someone who wants to be absolutely as good as they can possibly be.”

Though Anisimova’s mother Olga taught her the fundamentals until Amanda was 7, the family relied heavily for her early development on Saviano, a gifted technician who has worked with Genie Bouchard and Sloane Stephens and many others.

The Anisimovs had a clear plan, one they developed, as is often the case in tennis families, by learning from their eldest child’s career.

Amanda’s only sibling, Maria Egee, is 13 years older and played tennis in the Ivy League at the University of Pennsylvania, a remarkable feat considering that she started playing the game at age 11. She has gone on to a notable career in finance as a vice president at Goldman Sachs and a director of credit trading at Bank of America before joining Loop Capital in Miami.

Getty/Maria Egee, at this year’s Wimbledon, is in the upper left corner

Getty/Maria Egee, at this year’s Wimbledon, is in the upper left cornerMaria and her parents moved to the United States in 1998 during a financial crisis in Russia (Konstantin told me he and his wife both worked in the banking sectors). Maria was 10 and none of the family spoke much English. Konstantin told me they had seriously considered moving to Spain but had decided at that stage in world affairs that there was more opportunity in the U.S. and more chance to truly assimilate.

“We really like Spain, but then we recognized when we visited America that everybody who comes here is going to feel like home,” he said. “In Europe, you always feel like a foreigner because it’s a completely different culture. America is a united country where people come from all over the world, and after a couple of years, they feel this is home, you know?”

Amanda was born in 2001 and was soon mimicking her much older sister’s strokes with a miniature racket as she watched from courtside. The family relocated to Florida in 2004 for the weather and to help advance Maria’s tennis career, but it was Amanda’s tennis that benefited most. She was home-schooled from an early age, and Olga started teaching tennis to other youngsters in the area in part so that Amanda would have a circle of peers.

“We didn’t want to take her whole childhood away from her,” Maria told me in an interview for the New York Times in 2020. “It was important to have regular social interactions, so mom had lessons for kids and Amanda would train on the court next to them, and all the lunch breaks and pool time and interactions after that, they would be together. Some of her best friends are still people she met at that time, but I was watching the kids and just knew Amanda was different and special. I never met anyone that age that had that work ethic and maturity level. She is also just physically very gifted.”

Maria, who sometimes served as a sparring partner, also sensed the strong will of her mother.

“You could tell she was willing to sacrifice her whole life for my sister to have this American dream, which is actually a world dream,” Maria said. “I had faith in them. Never a doubt in my mind.”

Konstantin, a strapping and expansive man, also played a crucial role. During our interviews, he seemed attuned to the pitfalls of raising a child prodigy, particularly after early success.

“I saw a lot of parents who got immediately delusional, and those stories end up in a very bad way,” he said. “You can’t overtrain. You can’t over-push.”

Konstantin and Amanda in 2017/Getty

Konstantin and Amanda in 2017/GettyHe was intent on Amanda avoiding burnout. Sadly, it happened anyway, even though he did not live to see it. He and Olga separated in 2018 but remained on good terms, according to Maria. He died at their home in Aventura when Amanda was in New York preparing for the 2019 US Open with Olga.

Amanda withdrew from the Open, and I traveled to Florida again later that year to meet with her ahead of the 2020 season.

“This is obviously the hardest thing I’ve had to go through and the hardest thing that’s ever happened to me, and I don’t really talk about it with anyone,” she said then. “The only thing that has helped me is just playing tennis and being on the court. That’s what makes me happy, and I know it would make him happy, so that’s the way it is.”

At that stage, she was already a Grand Slam semifinalist, losing to Ashleigh Barty in Paris in 2019. It has taken another six years for Anisimova to go one step further at a major, and it has been poignant to watch her not only fulfilling her potential at Wimbledon but reveling in it: beaming in the sunshine or tumbling to the grass after her nervy victory over Anastasia Pavlyuchenkova in the quarterfinals and then celebrating with Maria’s young son Jackson in tow.

“When I took my break, a lot of people told me that you would never make it to the top again if you take so much time away from the game,” Anisimova said. “That was a little hard to digest, because I did want to come back and still achieve a lot and win a Grand Slam one day. Just me being able to prove that you can get back to the top if you prioritize yourself, that's been incredibly special to me.”

CC

Christopher Clarey's Blog

- Christopher Clarey's profile

- 30 followers