All on the Line

Getty/Al Bello

Getty/Al BelloNEW YORK – It’s a long-running tennis debate.

If you had to pick one man to play a match for your life, who gets the assignment?

For many years, it was obvious: Rafael Nadal with his whipping topspin, warrior spirit and unflagging commitment to each and every point.

Nadal, you could be certain, would not go down without quite a fight.

Then, true to form, Novak Djokovic strived and self-actualized his way to the head of most lines, transforming himself, with Nadal and Roger Federer for fuel, into a grand-match master, capable of locking down in the rallies and tournaments that mattered most.

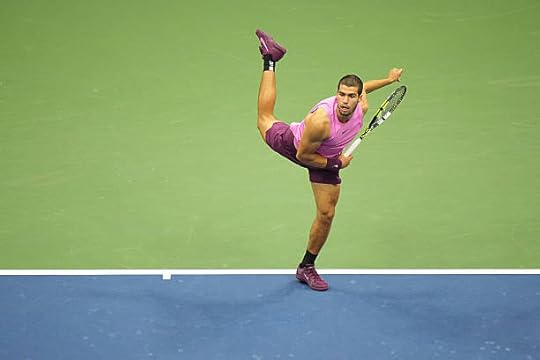

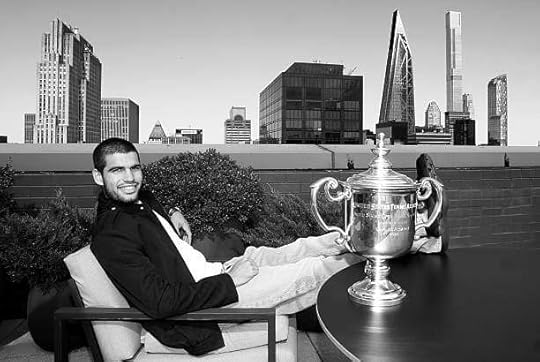

But this is Carlos Alcaraz’s time and not simply because he manhandled Jannik Sinner in Sunday’s US Open final to recover the No. 1 ranking.

It’s about more than recency bias and current form. It’s about his body of work at age 22. Though Alcaraz -- with his creative streak, crowd-pleasing instincts and shot-selection issues -- has often been viewed as less dependable than his teutonic Italian rival, he is, at this stage, clearly the best pressure player in the sport.

The proof was in his newly efficient, often clinical approach to match play in New York, where he dropped only one set and was broken just three times in the tournament with his upgraded serve setting the pace. He won more than 83 percent of his first-serve points in all but one of his seven matches. Compare that with Wimbledon, traditionally a servers’ paradise, where he was above 80 percent in only three of seven matches.

Getty

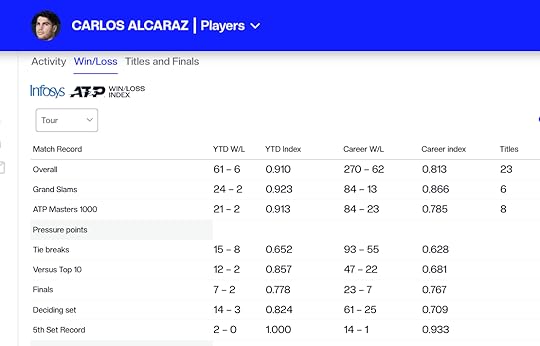

GettyBut the proof is also in the early-career numbers. Alcaraz is a glittering 6-1 in Grand Slam singles finals, the only loss coming at Wimbledon this year to Sinner. At the next tier, he is 8-1 in Masters 1000 finals, the only loss coming to Djokovic in one of the most dramatic best-of-three-set matches in memory: the 2023 Cincinnati Open final.

Sinner’s numbers are 4-2 in major finals and 4-4 in Masters 1000 finals with a 1-1 record in finals at the ATP’s year-end championships, where Alcaraz has yet to reach a final.

Their record in fifth sets is also worth considering.

Alcaraz is 14-1. Sinner is 6-10. Expand that to deciding sets, and it’s much closer, but Alcaraz still has the edge. He is 61-25 (71%). Sinner is 67-33 (67%). Both, it should be noted, remain behind Djokovic, who 218-85 (72%), but as much as I respect Djokovic’s steely will and absence of middle-aged body fat, I’m not picking a 38-year-old who has not won a major in two years to play for my life.

ATP

ATPAlcaraz has faltered on big occasions to be sure.

See the Olympic gold-medal match against Djokovic in Paris last year that left Alcaraz reeling and contributed to his second-round exit at last year’s US Open against Botic van de Zandschulp.

See his cramp-filled defeat to Djokovic in the 2023 French semis or his surprise loss in the semis to Jack Draper in Indian Wells this year when Alcaraz felt pre-match dread and played like it.

Getty/Paris Olympics

Getty/Paris OlympicsBut much more often than not, he has risen to the grand occasion, drawn to the challenge and the chance to commune with the biggest audience possible.

“His character on the court is so big,” his coach and mentor-in-chief Juan Carlos Ferrero once told me. “He loves to go for the big points and for the big moment and is one of the few guys that you can see who is like this.”

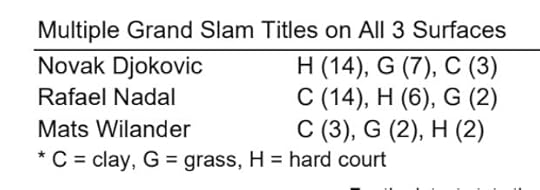

His 6-1 major final record puts him in elite company. The only men’s champion to start faster in the Open era was Federer, who went 7-0 before Nadal beat him in the 2006 French Open final.

Bjorn Borg also went 6-1 but neither Borg nor Federer quite stack up to Alcaraz’s multi-surface achievements in the majors.

Christopher Clarey's Tennis & Beyond is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The Spanish youngster already has won two Grand Slam titles on grass, two on clay and two on hardcourts. Borg never won a hardcourt major, failing to seal the deal after the US Open went to hardcourts for good in 1978 and retiring long before the Australian Open switched to hardcourts in 1988.

Federer won his lone French Open in 2009 at age 27, although he did reach four other finals on the red clay at Roland Garros.

Getty

GettyThe only men to win multiple majors on tennis’s three different surfaces are Mats Wilander, Nadal, Djokovic and Alcaraz.

It is a club that many past greats had no chance to join. Until 1975, three of the four Grand Slam tournaments were on grass, and you have to believe that the likes of René Lacoste, Henri Cochet, Tony Trabert, Manolo Santana, Roy Emerson and Rod Laver – who all won multiple clay and grasscourt majors -- could have won plenty of hardcourt majors if given the chance. The same certainly goes for Bill Tilden and Don Budge.

US Open

US OpenBut this modern-day club reflects versatility and consistency, and if Alcaraz can continue to marry the two while keeping his health and head, he is on his way to double digits in major victories.

It has been a banner year. One of the best barometers for a dominant season is a winning percentage in the 90s. Nadal and Djokovic each managed it twice; Federer did it four times, with three straight in 2004, 2005 and 2006 before Djokovic’s emergence.

Alcaraz, with the US Open in the books, is at 91 percent for 2025 with a 61-6 singles record. Until now, his top mark in a season is 85 percent. Sustaining momentum through the fall will be a challenge, and he smartly decided to skip Spain’s Davis Cup qualifier matches this week to decompress. But it won’t be much of a rest. He is expected to return next week for the big-payday Laver Cup team event, which he enjoyed in his debut last year.

Sinner, with host and reigning champ Italy already qualified for the Davis Cup finals in Bologna, does not have to worry about this round. But he does have to worry about Alcaraz and the future.

Getty

GettyFor the second straight year, he and the Spaniard have split the majors. If Sinner had converted any of his three match points in this year’s French Open final, he could have done better than a split, although there is no telling what a tough loss in Paris might have done to Alcaraz’s motivation and results at Wimbledon.

But Sinner, to his credit and our benefit, did not sound satisfied with the status quo after his defeat in New York.

He recognized that what works against the rest of the field is not sufficient against Alcaraz. He committed himself to becoming, like his rival, more unpredictable, and not just against the Spaniard.

“For example, during this tournament, I didn’t make one serve-volley, didn’t use a lot of drop shots, and then you arrive to a point where you play against Carlos where you have to go out of the comfort zone,” Sinner said. “So I’m going to aim -- maybe even losing some matches from now on – but trying to do some changes, trying to be a bit more unpredictable as a player, because I think that’s what you have to do, trying to become a better tennis player. At the end of the day, that’s my main goal, no?”

This could be more subtle than obvious: Sinner came to net nearly as often as Alcaraz on Sunday with similar success: winning 19 of 26 points compared with the Spaniard’s 20 of 27. But Sinner did change spin and pace less frequently, and even if he had wanted to drop shot more often, Alcaraz’s extreme quickness makes that quite a risk.

Though it is not easy to go against your core tennis personality, the Big Three certainly added to their games. Federer, once resistant to the drop shot, came to enjoy deploying it. Djokovic and Nadal learned to use serve-and-volley selectively but very effectively.

Getty

GettySinner, already proficient in the forecourt, surely can expand his range at age 24. But Alcaraz has been playing with great variety since his early junior years. It is part of his makeup, in line with his instincts and his understanding of how to enjoy tennis.

“The way he plays, I think it’s a little bit easier than maybe for others,” Ferrero said of the whistle-while-you-work factor.

But joy and creativity will only get you so far in pro tennis. Devastating power, extreme precision and footspeed are the trump cards, and Alcaraz put the full package on display in New York.

In the Wimbledon final, his average serve speed was about three miles per hours below Sinner’s on first and second serves. In New York, they were equal on first serve speed with Alcaraz having a two-mile-per-hour edge on the second.

At Wimbledon, Sinner had eight aces and two double faults while Alcaraz had 15 aces and seven doubles. In New York, Sinner had two aces and four doubles. Alcaraz had 10 aces and zero doubles and won significantly higher percentages of points than Sinner on both of his serves and when returning both of Sinner’s serves.

In my eyes, it was an off day for the Italian, full of imprecision and uncharacteristic errors. He had 18 groundstroke winners in the Wimbledon final; just seven in the US Open final. The forehand battle, often a spectacularly fair fight, was a rout in New York, with Sinner producing just two forehand groundstroke winners to Alcaraz’s 14. The Spaniard’s form certainly was the main factor.

“I felt like he was a bit cleaner today,” Sinner said. “The things I did well in London, he did better today. I felt like he was doing everything slightly better today, especially serving, both sides, both swings very clean.”

Though there was considerable resistance to this on social media when I suggested it early in the final, there might even have been a minor physical issue in play for Sinner despite his team’s denials. He was treated for an abdominal muscle issue during the semifinals.

If true, it would take little away from Alcaraz’s achievement. The sport is about managing the rigors of a nearly year-round schedule and staying healthy enough to compete, and Alcaraz, let’s not forget, also had a wrap around his right thigh during the final.

Playing with pain is part of pro tennis, as Nadal, Djokovic and Federer would confirm. So is playing with big-match pressure, and Alcaraz is doing that better than anyone in the men’s game.

Sign him up.

CC

Getty

Getty

Christopher Clarey's Blog

- Christopher Clarey's profile

- 30 followers