AngryWorkers's Blog

January 28, 2026

‘Chinga la migra!’ – Wildcat on undocumented workers and the struggle against ICE

The next issues of the magazine Wildcat will focus on the question of who can stop Trump. To this end, we will examine class relations in the USA: ‘the lumpen,’ ‘the service proletariat,’ ‘tech workers,’ ‘industrial workers’ and ‘the undocumented,’ i.e. migrants without identity papers or legal residence status. In light of the dramatic escalation in Minneapolis, we are publishing this section in advance as a work in progress. (This section does not deal with Trump’s radical restructuring of the state; that will be covered elsewhere.)

Undocumented workersIn the United States, people without official residence permits are referred to as ‘undocumented’. Most of them are refugees from Latin America, Asia and Africa who can be easily deported, at least according to their status. Depending on the source, there are between 10 and 15 million undocumented. The latest estimates from the Pew Research Center and the Migration Policy Institute put the figure at 14 million (2023) – four per cent of the population. A study conducted in August 2025 was able to assign 8.5 million to specific sectors: 20 per cent in construction, 12 per cent in hospitality, 11 per cent in manufacturing, 10 per cent as support staff in public infrastructure, 8 per cent in retail and 3 per cent in agriculture. Although 95 to 99 per cent of the 8.5 million work continuously, only 53 per cent have health insurance. 52 per cent have been living in the US for at least ten years, 28 per cent for at least 20 years. Only a third of these workers have almost no formal education. The study assumes that the figure for agriculture (3 per cent or 300,000 undocumented migrants) is too low.1 According to data from the US Department of Agriculture, foreign-born undocumented migrants make up about 40 per cent of the total 1.2 million workers in the industry, which would be 480,000.2

In recent decades, undocumented immigrants have fought for and achieved significant improvements – not only ‘tolerated stay’, but recognition through the so-called ‘sanctuary policy’. This dates back to the church asylum movement of the 1980s, which supported civil war refugees from Central America under Reagan. ‘Sanctuary’ is a formal term and consists of laws, statutes, administrative orders, guidelines, resolutions and regulatory documents from various institutions, such as city governments, universities, states, company premises, etc. The degree of legal binding and formality is often related to the degree of legal autonomy of the respective institution. Many rules are informal and highly contested.3 Roughly summarised, a ‘sanctuary policy’ means that immigration enforcement agencies have been decoupled from social and legal infrastructures. In 2025, over 150 cities, counties and states practised this. ‘Sanctuary cities’ (New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, etc.) have established themselves as relatively safe places for undocumented immigrants. There, they can obtain health and social insurance as well as government benefits (Medicaid, SNAP food assistance, etc.). Police officers and other officials do not ask about residence status or request documents. The police-military ‘deportation complex’ has no access to social security numbers.

Trump’s attack on the ‘sanctuary policy’It is true that ‘Deporter-in-chief’ Obama, US President from 2009 to 2017, had already reversed the ratio between “returns” (rejections at the border or voluntary departures) and ‘removals’ (deportations) in favour of the latter. But Obama and others before Trump II did not organise raids and systematically deport people who had been living in the US for a long time and were integrated into social life there.

The ‘Project 2025’ paper, published in 2023, which serves as a blueprint for Trump’s second term, makes a clear statement on the ‘sanctuary policy’: ‘All ICE memoranda identifying “sensitive zones” where ICE personnel are prohibited from operating should be rescinded.’ 4 Trump is attacking the ‘sanctuary policy’ head-on.

According to the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS), 605,000 people were deported in 2025, 66,000 are in deportation detention centres, and 1.9 million left voluntarily. 4,250 people have gone missing since their arrest, 30 people have died in deportation camps, four during arrests and one during deportation. The number of deportations in 2025 was twice as high as the average for the years 2014-2024.5 However, there are indications that this figure has been artificially inflated by the ministry.

Over two-thirds of those arrested by the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency have not committed any crimes. Many others have been targeted for traffic tickets or drug use.

Trump’s SA?Ten years ago, members of the right-wing militia Patriot Prayer threatened to ‘clean up’ the left-liberal sanctuary city of Portland. The Portland Bureau of Police was in close contact with Patriot Prayer and its leader Joey Gibson, who ran for the Republicans.6 For his attack on the undocumented, Trump has institutionalised right-wing militias such as the Proud Boys under the banner of ICE (the second immigration agency in the Department of Homeland Security is CBP, Customs Border Protection, the border protection agency). He pardoned Proud Boys boss Enrique Tarrio, like many others who took part in the storming of the Capitol. Tarrio introduced the ‘Iceraid’ app, which allows users to report illegal immigrants and receive cryptocurrency as a reward.7 Hardliner Tom Homan was ICE director under Trump I. After Trump’s re-election, he became border protection commissioner and met with Proud Boy Terry Newsome to discuss mass deportations.8

The current ICE director, Todd Lyons, wants to establish efficient deportation logistics ‘modelled on Amazon’ for the planned 3,000 arrests per day. The government is spending over 150 billion USD on this: investments in infrastructure and new personnel, the large US prison companies GEO Group and CoreCivic are building new deportation prisons, Palantir is programming anti-immigrant software called ImmigrationOS, and ICE is buying mobile phone data from advertising companies to track people using their location data9. They are all earning very well under Trump II (a third of all CoreCivic‘s revenue comes from deals with ICE alone). During the government shutdown from the 1st of October to the 12th of November 2025, Trump wanted to withhold money for food aid and thousands of civil servants were no longer paid – but he continued to pay the ICE and CBP thugs and gave new recruits a 40,000 USD hiring bonus, above-average health insurance and repayment of student loan debts over 60,000 USD. In order to get as many armed troops on the streets as quickly as possible, Trump has reduced the training period for new ICE recruits from 13 to six weeks and cancelled Spanish language courses. In October 2025, NBC revealed that new ICE personnel had been sent into service before the completion of official screening procedures and that some had failed drug tests.10

Even during the George Floyd rebellion, former Bush homeland security chief Michael Chertoff warned against the ‘politicisation’ of the Department of Homeland Security. The then NBPC president, Brandon Judd, had said in 2016 that immigrants were ‘worse than animals’ – under Trump II, he has now become ambassador to Chile! The NBPC (National Border Patrol Council) and NIC (National ICE Council) are the two unions in the Department of Homeland Security. Even back then, they were demanding more money and an expansion of their powers. They saw Trump as their natural ally, and Trump saw them as a potential power base. After losing the 2020 election, Trump tried to use the NIC and NBPC against Biden. The then Deputy Secretary of Homeland Security, Ken Cuccinelli, wanted to strengthen both unions. When that failed, ICE officials opposed the Biden administration. In 2022, they filed a complaint with the Department of Labour demanding more autonomy from the umbrella unions AFGE (American Federation of Government Employees) and the AFL-CIO, which they saw as ‘far-left organisations’.11 Cuccinelli then wrote the section on homeland security in the Project 2025 paper, where he calls for the abolition of ‘sanctuary cities’. Michael Macher, author of the online newspaper Phenomenal World, sees the right-wing hardliners organised in NIC and NBPC as ‘incubators for right-wing projects’ in the department.12

When Trump wanted to stop the raids in June 2025 after complaints from the agricultural sector, his fascist security adviser Stephen Miller allowed them to continue. After the raid on a Hyundai factory construction site in Georgia on the 4th of September, Trump was forced to apologise. ‘The close relationship between ICE/CBP and Trump has paradoxically begun to limit Trump’s own room for manoeuvre.’ (Michael Macher)

On the 14th of January 2026, journalist Ken Klippenstein published leaked documents showing that ICE is conducting secret operations. Among other things, they are trying to recruit informants within the immigrant community. ICE is even splitting the FBI over this.13

ResistanceUndocumented workers have repeatedly fought important battles throughout history: at the beginning of the 20th century, the immigrants, day labourers and migrant workers who built the US infrastructure (wood and railways) organised themselves as the IWW (Wobblies). The Wobblies were strong because they were incredibly mobile and well organised, but also because the capitalists could not build the transport routes without them. During and especially after the First World War, they were wiped out. In the 1960s and 1970s, workers in the fields of industrial agriculture organised themselves under the slogan ‘Sí se puede!’ (‘Yes, it is possible!’) into a large trade union, the United Farm Workers. In the mid-1990s and 2006, the undocumented mobilised once again for their interests, including mass demonstrations in major cities. In 2006, one of the slogans was: ‘We are workers, not criminals!’ During the mobilisations, millions of people took part in rallies in Los Angeles and Chicago for legalisation and against tougher immigration laws.

After Los Angeles and Chicago, Portland was the next major city that Trump declared a war zone and training ground for deportations and riot control in 2025. Broad social opposition to this developed in the cities. Depending on the context, people organise themselves in different ways: in Portland, left-wing groups and anti-fascists stand in the way of ICE troops14, while in Chicago and Los Angeles, this is done by large parts of the neighbourhoods and Hispanic community (including lawyers, etc.)15. In Seattle, Boeing union members, among others, are organising rallies in front of deportation centres to demand the release of one of their colleagues.16

The vast majority of sanctuary cities are administered by Democratic Party mayors. This is part of the picture, but it is not the decisive factor in why Trump chose Los Angeles as the first place to launch his attack. It is the melting pot where immigration and labour and community struggles mix in a politically highly effective way; in LA in particular, migrant and labour struggles are constantly present and often indistinguishable. On the 6th of June 2025, ICE arrested a migrant day labourer organiser and SEIU trade unionist (Service Employees International Union, the largest US trade union in the service industry) in LA. Thousands of people immediately showed their solidarity in their own ways – some set cars on fire and blocked roads, others programmed warning apps, and many used encrypted social media channels such as Signal to organise new blockades. Neighbours warned each other and set up telephone chains and hotlines, while motorists honked their horns and blocked ICE SUVs. From the 8th of June onwards, the protest spread across the country. Demonstrations and blockades were reported in San Francisco, Austin, Dallas, New York, Philadelphia, Tampa, Seattle, Atlanta, Santa Ana, New Orleans, Chicago and Louisville. The last anti-ICE action in this wave of protests took place on the 19th of June in downtown LA.

In December 2025, DHS operations and raids in cities were banned by the courts, but Trump and the DHS don’t care. ICE and CBP are not backing down and continue to rage.

Metro Surge: Attack on MinneapolisThe twin cities of Minneapolis and Saint Paul are located in the state of Minnesota. Minneapolis, with a population of 430,000, is governed by Democratic Mayor Jacob Frey, and the state of Minnesota by Democratic Governor Tim Walz, Kamala Harris’s 2024 vice-presidential campaign candidate. Minnesota voted against Trump in 2016, 2020 and 2024.

The metropolitan area, with four central ‘sanctuary counties,’ is home to 3.7 million people, including one of the largest groups of indigenous people and refugees from all over the world. Minneapolis is also home to an above-average number of descendants of slaves who were brought from Africa, as well as refugees from the African civil wars of the 1990s. Most of these have been naturalised; of the 100,000 Somalis throughout Minnesota, 90 per cent are US citizens (58 per cent of all US Somalis were born in the US, and 87 per cent have citizenship).

Relative to the population, the proportion of undocumented immigrants in the state is below the national average at 2.2 per cent, or 130,000 people, according to the Pew Research Centre, and well below the figures in Republican-governed states such as Texas and Florida. 17 But Minneapolis in particular has been the hotspot for large grassroots mobilisations more often than other places, unionisation rates are much higher than in other parts of the US, and non-profit organisations and social services are above average by US standards. Since 2018, workers who have immigrated from Somalia in particular have been organising strikes. The centre of the mobilisation is the Amazon warehouse in Shakopee, a suburb south of Minneapolis with a population of 44,000.

In May 2020, George Floyd was murdered by officers of the Minneapolis Police Department. Some people were so angry that they quickly reacted by setting fire to the police building. This was followed by the largest street mobilisation in US history. One of the slogans was ‘Defund the Police,’ meaning no more money for the apparatus of repression. Little has changed in material terms; statistically, police officers in Minneapolis and St. Paul are still above average in terms of violence.

In early December, the Department of Homeland Security announced that it would carry out ‘Operation Metro Surge,’ ‘the largest operation ever,’ in Minneapolis-Saint Paul. Trump kicked things off by declaring the 35,000 Somalis living in Minneapolis to be ‘garbage,’ literally ‘low-IQ garbage.’ He did so against the backdrop of a social welfare fraud case in Minnesota that has been under investigation for five years and involves Somalis. Some of those convicted so far had contact with Frey and other Democrats, at least two of whom are of Somali descent.18 In October 2025, Trump organised the ‘Roundtable on Antifa,’ to which he invited right-wing extremist influencer Nick Shirley. He then travelled to Minneapolis and produced a report on social security fraud by Somalis.19 Vice President JD Vance and Elon Musk shared the video.

In mid-December 2025, 2,000 armed and masked ICE and CBP officers descended on the Twin Cities (ICE and CBP carry out most operations jointly; and, as during the George Floyd protests, right-wing militias came from far and wide to support them). They went door to door, interrogating residents to find out if they knew of any places where illegal immigrants could be found. They smashed the windows of houses and cars where they suspected illegal immigrants were staying. They pursued cars and used flashbang grenades. Comrades report that ICE even arrested Native Americans!

The widely organised defence‘ICE has made the classic Nazi mistake. They’ve invaded a winter people in winter.’

(someone on the ground)

Federal officials had not anticipated such strong resistance from the population. Left-wing groups have reactivated organisational structures from the George Floyd movement. Existing migrant solidarity, neighbourhood and church groups, NGOs and tenants’ unions have organised support, blockades, legal aid, behavioural training, etc. In addition, there was direct solidarity in the workplace: colleagues in hospitals and schools organised alarm groups, and self-protection was also organised in small migrant-owned businesses; guards were posted in places where many immigrants traditionally work, such as supermarkets and DIY stores. Local trade union chapters supported the actions. There were and still are attempts to organise wildcat strikes. And many are specifically seeking out the hotels where ICE personnel are staying in order to deprive them of sleep with music and other actions.20

Added to this is the weather, with temperatures well below zero degrees Celsius being normal for a winter in Minnesota. This causes problems for the ICE thugs, who often slip and slide on the ice sheets themselves and their SUVs when patrolling from house to house. The local population is better equipped for these temperatures and can endure being outside for longer.

The brutality of the repression has brought many people together. In the fight against the raids in Los Angeles and Chicago, ICE Watch Rapid Responder Groups have been formed to disrupt ICE operations and help those affected. This model has been adopted in Minneapolis. They are able to organise blockades and legal protection within two to twelve minutes (ICE Watchers in Minneapolis report new ICE actions every 15 minutes on average). There are Safety Brigades, Neighbourhood Rapid Response Groups, Business Safety Brigades, Native-led Community Defence, etc. Even the local police escort school buses to protect them from ICE raids!

To avoid being recognised, ICE thugs have plastered their cars with ‘Free Palestine’ stickers, attached toy trailers, affixed disabled stickers, frequently changed their number plates, etc. People who film ICE operations and responder group activists are beaten up, seriously injured with broken bones and eye injuries leading to blindness – and now they are even killed.

On the 7th of January 2026, ICE officer Jonathan Ross shot and killed Rapid Responder Group activist Renée Nicole Good, 37 years old and mother of three children. Good lived in a neighbourhood with Somalis and Hispanics.21 Her shooting was the sixth ICE murder,22 but the first execution. Her killer served in Iraq and has been working for ICE since 2016. He is described as a Christian fundamentalist and staunch MAGA supporter.

The videos of the murder show the agency’s tactics: as two ICE officers approach Good’s car, one tells her to drive away while the other shouts, ‘Get out of the fucking car!’ No matter how you react, you violate one of the instructions and thus provide the pretext for escalation.

JD Vance announced on the 8th of January that Ross enjoys ‘absolute immunity’. On the 9th of January, CBP officers shot and seriously injured two immigrants in Portland; On the 14th of January, an ICE officer shot a Venezuelan man in the leg in Minneapolis.

By early January 2026, there were already at least 2,800 armed federal officers in Minneapolis. The Minneapolis Police Department employs 600 police officers. Trump reserves the right to invoke the Insurrection Act so that he can deploy the military and the National Guard; this act was last used during the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Homeland Security Secretary and ICE chief Kristi Noem has hinted that she wants Governor Walz out of office. The Justice Department has launched investigations against him, Mayor Frey and others. As of mid-January, ICE had arrested nearly 3,000 people in Minneapolis-St. Paul.

But demonstrations continue to take place under the slogan ‘Chinga la migra!’, which means ‘Fuck ICE’. After Renée Good was shot on the 7th of January, the protests intensified. On the 8th of January, 10,000 people took to the streets. Six prosecutors resigned because the US Department of Justice wanted to force them to launch a police investigation against Good’s widow. At the end of January, the FBI agent who investigated Ross resigned after the Department of Justice demanded that she drop the investigation.

‘ICE out!’ The day of action on the 23rd of JanuaryThe day before the day of action, JD Vance had come to Minnesota especially for this purpose. In a press conference, he blamed the local authorities and the Democrats. Because they did not cooperate with ICE, he said, things had gotten ‘out of control.’ By this he probably means that ICE and CBP can no longer take a step without being disturbed.

The 23rd of January was the biggest day of protest so far. Hundreds of shops remained closed, employees stayed away from work, and students and pupils stayed away from school. With temperatures as low as minus 25 degrees Celsius, more than 50,000 people took to the streets. The four demands: ICE out of Minnesota (‘ICE out!’); charges against Jonathan Ross; no additional money for ICE; companies should no longer do business with ICE. Many small business owners closed their shops, some served only food in support, and many in the education and health sectors went on de facto strike. Religious leaders and supporters attempted to block the airport which ICE and CBP use to deport people. In the run-up to the protest, some voices called for a general strike, but most trade unions prevented this because they adhere to existing collective agreements that prohibit strikes. There is no evidence or figures yet on mass sick leave. Some institutions have announced that they will waive sanctions if people stay away from work. Solidarity demonstrations took place in New York, among other places; Payday Report counted 300 solidarity actions across the United States.

What was special about this day of protest was that it was almost exclusively supported by ‘documented’ individuals. For their own protection, undocumented individuals remained at home. Local authorities have introduced virtual lessons for vulnerable pupils (half of Spanish-speaking children and a quarter of students with Somali roots are currently not attending classes). Even UN Human Rights Commissioner Volker Türk said on that day that he was ‘dismayed by the now daily mistreatment and degradation of migrants and refugees’ in the USA.

The next day, CBP officers executed a second person: Alex Jeffrey Pretti, a 37-year-old intensive care nurse at a hospital for veterans, US citizens and city residents. Pretti was filming an ICE operation; when the cops knocked a woman down, he stepped in between them. At least six officers pinned him to the ground, beat him and fired ten (!) shots at him. Then came the usual bullshit from the government and DHS: the officers had to defend themselves, Alex was about to commit a ‘massacre of the officers,’ he was a ‘domestic terrorist.’, which is how they had described Renée Nicole Good, as well. Alex was a legal gun owner and apparently had a gun with him. But he wasn’t holding a gun in his hand, he was holding his smartphone. As early as June 2025, a paper was circulated within the Department of Homeland Security criminalising the filming of ICE officers as an ‘illegal tactic of civil disobedience’.

Attorney General Pam Bondi wrote a letter to Governor Walz on the same day, saying that his “rhetoric” was promoting “lawlessness on the streets”. She demands that Walz hand over all documents relating to the federal programmes (Medicaid, SNAP) affected by the above-mentioned fraud to the Department of Justice, that the Minnesota police cooperate with ICE, and that the Minnesota voter registry be handed over. (In early January, Trump claimed that the elections in Minnesota were rigged and that he had done ‘greatly’ there.)

Trump has now sent Tom Homan to Minnesota to lead the operations there. After Renée Good’s death, Homan had called for ‘further consistent action without apology.’

Civil war or class struggle?Hundreds of people quickly gathered at the scene of the murder. Walz has now called in the National Guard to de-escalate the situation. National Guard soldiers are to wear neon vests so that they can be distinguished from ICE/CBP. This further militarises the conflict.

In armed street fighting, ‘civil society’ doesn’t stand a chance. It looks like Trump, who’s under massive pressure on many fronts, is banking on armed conflicts escalating into a civil war scenario. After the 23rd of January, ICE wants to be able to raid homes without a search warrant – until now, people have been safe in their homes. Now the primary task is to confront the right-wing extremist shock troops en masse and defend the ‘sanctuary cities.’ Residents are preparing for a tough fight. According to information from hotel employees, ICE has booked rooms until the end of June 2026.

As after the murder of George Floyd, many people have become newly politicised and want to ‘get involved’; they show incredible acts of solidarity. Leftists are discussing what they need to do better after the experiences of 2020, what forms of organisation can make the protests stronger. The emerging self-organised infrastructure of networked initiatives will play an important role.

Would undocumented workers have the power not only to stop the ICE raids, but even to challenge the Trump administration? A ‘general strike’ by all undocumented workers is probably a utopian dream, but even a significant proportion of them could paralyse many sectors and confront those fellow workers who have citizen status with the intolerable conditions that the undocumented have to deal with. In an escalated situation, many would have to decide which fate they share: duck away or fight together? The advantage at the moment is that many of the Hispanics who voted for Trump are turning away from him.

Organising in these areas is difficult. In the harsh winter, there is no work in the fields or on construction sites. But migrant hotel employees could refuse to accommodate ICE officials. Employees of car rental companies, where ICE thugs pick up their neutral SUVs, could refuse to give them the keys. These suggestions are not fictional; initial attempts have been made and they are being discussed.23 Blockading important transport infrastructure such as the airport could build pressure. The Minneapolis-St. Paul region is also an important hub for parcel and rail logistics. Trump’s thugs do not care about law and order; they use the state terrorist methods of narco-states and military dictatorships. People must find their way in this situation and come up with new answers.

Stopping Trump will require more than neighbourhood mobilisations and a courageous civil society. Many called the combination of street protests, blockades and walkouts on the 23rd of January a ‘21st century general strike’.24 But without extending the strikes to large businesses, transport and warehouse logistics, Trump’s troops cannot be stopped.

Part of the class is threatened with deportation and death, and supporters are to be deterred with executions. Trade unions are likely to find it difficult to maintain industrial peace – initial meetings to organise genuine work stoppages across the US are now taking place.

The Minnesota Post has current pictures of the protest

The Guardian on US-wide protests

—————————–

Footnotes:[1] Centre for Migration Studies, 27 August 2025

[2] Economic Research Service of the Department of Agriculture, 18 November 2025

[3] Janika Kuge: Bleiberecht jenseits des Nationalstaats: Kämpfe um Sanctuary Policy in den USA (Right of residence beyond the nation state: struggles over sanctuary policy in the USA), Westfälisches Dampfboot 2025, p. 22ff.

[4] Project 2025 (p. 174 in the PDF)

[5] Economic Policy Institute, 10 July 2025

[6] The New Republic, 19 August 2025

[7] The Atlantic, 5 August 2025

[8] Jeff Tischauser, SPL Center, 7 February 2025

[9] Joseph Cox, 8 January 2026 on 404media

[10] NBC News, 22 October 2025

[11] Washington Times, 21 June 2022.

[12] Michael Macher, Enforcement Regime – Immigration hardliners in the US state, 9 January 2026

[13] Ken Klippenstein, 14 January 2026

[14] Die Zeit, 19 October 2025

[15] The American Prospect, 22 October 2022

[19] The Intercept, 31 December 2025.

[20] YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CRwbQ..., https://www.youtube.com/shorts/K731Qs..., https://www.instagram.com/reel/DTUJ0Q...

[21] Labor Notes, 1/2026.

[22] On the 10th of July 2025, farmworker Jaime Alanís Garcia fell to his death while fleeing ICE agents during a raid in California; on the 14th of August, day labourer and trade unionist Roberto Carlos Montoya Valdez was run over by an SUV as he fled from ICE officers who were raiding a Home Depot store in Southern California. On the 12th of September 2025, ICE officers shot and killed Silverio Villegas González during a traffic stop in Chicago. On the 23rd of October, gardener Josué Castro Rivera was run over by a truck in Virginia as he attempted to flee during an ICE traffic stop. In mid-January 2026, an autopsy revealed that Cuban Geraldo Lunas Campos did not die by suicide on the 3rd of January in the largest deportation prison in El Paso, as claimed by the DHS, but by murder.

[23] Counterpunch, 9 January 2026

[24] The Intercept, 24 January 2026

The post ‘Chinga la migra!’ – Wildcat on undocumented workers and the struggle against ICE first appeared on Angry Workers.

January 25, 2026

An organisation of workers’ autonomy? – Historical texts and current considerations (1)

The question of political organisation is pressing and we have to pose it precisely: how should a political organisation relate to the class movement?

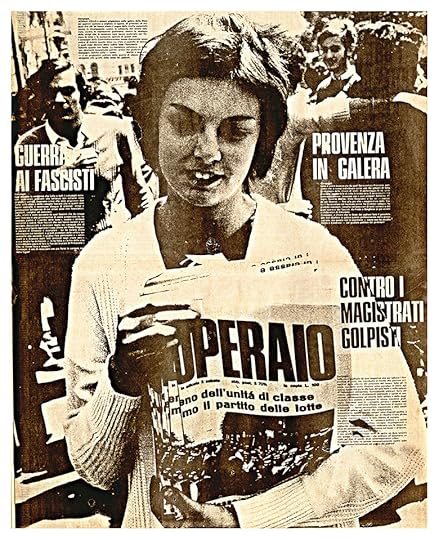

In order to approach this question we have a look at the organisational efforts that existed at a peak moment of class movement, the 1970s in Italy and try to draw conclusions from that. We find a seemingly contradictory situation. The two national extraparliamentarian organisations that were formed after the upheaval of 1968/69, namely Lotta Continua and Potere Operaio, entered a deep crisis exactly at a point when the class conflict intensified in the 1970s. Both organisations were questioned from within, primarily by local autonomous organisations of workers’ committees, and in the case of Lotta Continua, also by the emerging feminist movement. These committees criticised the national political organisations in two ways: in class terms (“against the leadership of intellectuals”) and politically (e.g. regarding the shift towards electoral politics and alliances of Lotta Continua). The autonomous organisations represented the working class core of the political organisations. They were also most closely engaged in actual practical efforts, from factory struggle to housing occupations to self-reduction of energy and transport prices to militant antifascist actions. It was not surprising that their experiences started to clash with the central lines of Potere Operaio and Lotta Continua, e.g. their abstract claim of party leadership and program or the decision to enter into alliances with more moderate ‘antifascist’ forces, who, like the Communist Party PCI, would oppose and denounce autonomous workers’ activity.

The workers’ committees contributed to the dissolution of the two main national organisations of the radical left, as they had lost touch with the more radical parts of their proletarian base, but, as often noted, the ‘workers’ autonomy’ was not able to ‘solve the organisational question’ either. This doesn’t mean that they were not aware of the fact that localism or sectorial boundaries would have to be overcome and that a coordinated and centralised political body was necessary. There were several larger organisational efforts to coordinate the autonomous bodies nationally and to intensify the debate around a common strategy. With this small series we want to retrace these efforts.

This first part of the series is a translation from 2022 that sets the scene of the first larger national congress of autonomous workers’ committees in Bologna in 1973 and the relation of the autonomous committees to Potere Operaio. The upcoming second part consists of a translation of an organisational proposal put forward by the committees and workers’ assembly at Sit Siemens, Pirelli and Alfa Romeo in 1973. In terms of chronology we suggest also reading the following article on Senza Tregua, which was a project of various autonomous committees to form a national structure and common strategy around 1975. The third part will be a strategic paper by comrades from Via Volsci in Rome, written after the movement of 1977, which sketches out their perspective on organisation, dual power and revolution. The final article of the series will try to summarise these developments politically and relate them to our organisational question today.

————————-

The “area” of workers’ autonomy

The first autonomous factory organisations began to form in 1971, taking the form of assemblies, committees and collectives. Many militants who had gradually left the political groups joined these autonomous organisations. This happened either as a result of an individual choice or because the grassroots structures, in which they carried out their political activities, gradually became distant from the extra-parliamentary organisation. For example, between 1972 and 1973 in Rome, the Enel Political Committee, the Policlinico Workers’ Collective and other autonomous organisations left the group Manifesto (partly due to a critique of Manifesto’s electoral plans – the translator); in Milan, the Alfa Romeo Autonomous Assembly broke with the Lotta Continua group to oppose the latter’s claim to hegemony over its line [1]; in Porto Marghera, the Autonomous Assembly, which arose in the aftermath of the rejection of the contract by the chemical workers of Petrolchimico and Chatillon in November 1972 [2], gradually distanced itself from Potere Operaio. An article published in ‘Potere Operaio del Lunedì’ in November 1972 stated:

“Even before the contract disputes of 1972, workers’ autonomy had felt the profound unease of not being able to express, either within the groups of the revolutionary left or in the (factory) councils where trade union control was strong, the content and forms of struggle that it potentially contained. Just as the Autonomous Assembly was formed in Marghera, so too are autonomous organisations springing up in many other situations in factories, neighbourhoods, towns and schools.”

This was followed by polemical tones towards the political groups:

“For this reason, we think it is wrong to see these organised moments of autonomy as mere instruments for the mass transmission of pre-established political lines, or as instruments for the organisation of sectoral struggles that are reunified by the political position of a group. In other words, we are against those groups that believe they are the revolutionary party and that autonomous organisations should become their mass organisations [3].”

The autonomous organisations also expressed the need to find moments of organisational centralisation that would prevent the confinement of struggles to their specific sphere, that would create a link between the factory and the social sphere, that would break the isolation of the working class by involving other subjects, such as students, the unemployed and women, in the struggle.

With this intention, on the initiative of the organised groups of Rome and Naples, a conference was held in Naples on the 25th and 26th of November 1972 to discuss the question of workers’ autonomy and the problems of the South. The themes of the need for revolutionary violence and a guaranteed wage were taken up again as central objectives (articulated in the struggles against “enforced mobility and flexibilisation, dismissals, work rhythms, high rents and high bills”) around which to unify different social sectors: workers, students, migrants and the unemployed. Finally, the problem of centralisation was addressed, putting it in the following terms:

“The organisation of workers’ autonomy is achieved not through the simple coordination of multiple struggles, but through the centralisation of the autonomous vanguards around a programme they set themselves and through the choice of appropriate tools. Centralisation is an indispensable condition in the process of building a revolutionary party [4].”

Once again, the key issue was the absence of an overall workers’ organisation, characterised by a genuine revolutionary will, resulting from a process of aggregation from below of existing assemblies and autonomous committees, capable of providing individual struggles with a general political meaning. To address this problem, some autonomous bodies organised a series of joint conferences in an attempt to develop a common line and overcome the fragmentation of the various situations of conflict. The first was the “pre-conference” held in Florence on the 27th and 28th of January 1973, in preparation for the “national meeting of organised workers’ autonomy” [5] in Bologna, scheduled for the 3rd and 4th March of 1973.

Potere Operaio gave ample space in its newspaper to the debate that took place at the Florence conference, showing curiosity and attention towards the proliferation of autonomous mass organisations, independent of the initiatives of extra-parliamentary left-wing groups and often taking positions that contrasted with, if not surpassed, those of the groups themselves.

Numerous interventions were reported in ‘Potere operaio del lunedì’ [6], and all of them highlighted the same issues, albeit in different contexts: the impossibility of resorting to trade unions in times of struggle, because they were now considered irretrievably subservient to the logic of capitalist restructuring; the need to “socialise” the conflict, i.e. to link factory struggles with those in the local area (house occupations, rent strikes, non-payment of transport), in order to unify the different proletarian categories on the basis of “material needs”; the urgency of creating a process of centralisation of the workers’ vanguards, which could give the struggles political and not just economic significance. The issues highlighted had to be resolved by overcoming the “logic of groups”, their claim to provide the line from outside [7] and the tendency to consider autonomous organisations as their own mass movement. Potere Operaio was explicitly invited to take a clearer stance:

“The problem remains, perhaps, for the comrades of Potere Operaio, who still have to decide on the long-term organisational issue of workers’ autonomy. There cannot yet be a relationship external to workers’ autonomy, but there must be interpenetration. Since its inception, Potere Operaio has been able to articulate slogans that have become part of the movement. For this reason, I believe that Potere Operaio must come to terms with the growing reality of workers’ autonomy. It must work to organise it, to build it, to make it the point of reference against the state [8].”

The attitude of the autonomous organisations towards the groups was not uniform: it included positions of decisive rejection [9], a willingness to engage in dialogue [10], and a willingness to open up and integrate. The meeting in Florence was followed by the national conference in Bologna. [11] The objectives to be pursued were set out in the conference announcement:

“What is under discussion is a project to centralise the organised forms of workers’ autonomy which – within the crisis of the system – will become the movement’s organised response to the concentrated attack by the bourgeoisie, providing a positive solution to the crisis of the groups and the sectoral nature of individual struggles and experiences.”

It also specified:

“It will not be a conference of workers’ autonomy (we do not claim the right to represent workers’ autonomy) […]. The national meeting in Bologna will have to decide on the date of a conference open to all organised autonomy (neighbourhood committees, proletarians, student-worker collectives, peasants, labourers, construction workers) and to those groups that make discussion and involvement in the programme of autonomy a long-term rather than a tactical choice [12].”

Potere Operaio was forced to confront the emergence of organisational attempts that were taking place outside the influence of the main left organisations. From an initial attitude of mistrust, it came to recognise the importance of these attempts for the future construction of the workers’ party, in light of the clear desire to overcome the limited scope of the committee in favour of a broader political organisational synthesis.

Potere Operaio appeared optimistic in feeling that the solution to the problem of the “workers” leadership’ of the movement was now close at hand, identifying it precisely in the experiences of the political committees and their attempts at aggregation:

“A political programme and an organisation capable of implementing it. This can and must lead to the overcoming of the experience of the committees and groups and their convergence and merging into a single political project and practice [13].”

Not all autonomous organisations were present at the Bologna conference. Many mass organisations were excluded. Only those groups that had already shown a shared set of objectives and a willingness to act according to a common approach, aimed at centralising the experiences of struggle, participated.

Despite initial caution, differences emerged at the meeting both on the timing of a possible national organisational process of workers’ autonomy and on the political line to be followed. Two positions emerged on the first point: on the one hand, there were the autonomous organisations of the south, particularly those in Rome and Naples, which were pushing for an accelerated organisational process; on the other, there were the autonomous organisations of Milan, which considered it necessary to proceed with a preliminary consolidation of action within their respective areas of intervention. On the second issue, the debate saw the committees in Marghera and Rome on one side

“with a political line inspired by the theses of Potere Operaio […] which starts from an assessment of the crisis of the bourgeoisie and the need to accentuate this crisis by introducing into the movement a whole series of objectives that cannot be integrated by capital, and then organising the movement to face the inevitable clash in the struggle for these objectives [14]”

on the other, the autonomous organisations of Milan, namely the assemblies of Sit-Siemens, Pirelli and Alfa Romeo, which argued that “the political line is the result of the real experiences of the working class, which the autonomous organisations interpret and guide, and not a pre-established platform”. They therefore opposed the “crystallisation of a pre-established political line that risks becoming ideology in the current situation, in which each organisation must deal with the particularities of its own situation” [15]. In the end, the debate saw the substantial affirmation of the positions supported by the organisations in Milan, with a scaling back of the organisational process and a commitment to intervene in concrete situations without first establishing a mandatory and abstract line to follow.

In Bologna, the ‘national coordination of autonomous assemblies and committees’ was established, a provisional commission tasked with dealing with mutual relations between the various organisations. The first product of this coordination was the ‘Bulletin of Autonomous Workers’ Organisations’, which was published in May 1973 and of which only two issues appeared [16].

Potere Operaio, which among its positive comments on the conference had noted the absence of the triumphalism usually present at meetings between workers’ vanguards, did not want to be excluded from what was happening. After stating that responsibility for the organisational process could not be placed solely on the autonomous committees, but rather “within the revolutionary camp as a whole”, it declared its “willingness to work together to build the workers ‘ network of work refusal, the party in the communist revolution” [17].

The internal debate within the autonomy area profoundly influenced the history of Potere Operaio. According to Judge Palombarini [19], based on witness statements given at the “7th of April” trial, the real break-up of Potere Operaio occurred after the third organisational conference in September 1971, around the issue of the formalisation of the party. Many militants, disagreeing with the position expressed by the national leadership, distanced themselves from it, continuing to carry out political activities as individuals or as part of grassroots organisations within the area of workers’ autonomy that was being organised. This satisfied the demands of those who, while wishing to create a national workers’ organisation that would unify the various local realities, did not believe in the possibility of a single group representing that moment of centralisation and saw Potere Operaio’s claim to become such a group as leading only to the progressive bureaucratisation of its structures and a loss of contact with the real situation.

Footnotes

[1] “We do not believe that the revolutionary workers” party can be formed in the traditional way: intellectuals setting a line which is then taken down to the factories to seek out the vanguards who will carry this line forward. This is not possible. The various autonomous movements must contribute directly to building the party of the working class. And we do not recognise this party in any group”. (Statement by a comrade from the Alfa Romeo Autonomous Assembly, “Potere operaio del lunedì”, no. 42, 25 February 1973, also reported in Autonomia operaia, edited by the Autonomous Workers’ Committees of Rome, Rome, Savelli, 1976, p. 25.

[2] See Marghera, oltre il bidone, Potere operaio del lunedì, no. 19, 19 November 1972, and L’Assemblea autonoma di Porto Marghera, Potere operaio del lunedì, no. 26/38, 28 January 1973.

[3] Document from the Naples conference of the 25th and 26th of November 1972, in Autonomia operaia, cit. p. 27.

[4] Communiqué from the Organising Committee of the Conference of Autonomous Committees and Assemblies, Potere operaio del lunedì, no. 43, 4 March 1973.

[5] The speeches are reported in issues 41 (18 February 1973), 42 (25 February 1973) and 43 (4 March 1973) of Potere operaio del lunedì.

[6] “Above all, the organs of workers” autonomy must be a point of convergence between the economic struggle and the political struggle: this division […] which traditionally gave rise to the trade union on the one hand and the party on the other, has been rightly criticised by a number of groups that have contributed to the birth of a revolutionary movement. But today we are witnessing the fact that these groups are reproducing this logic of dividing the economic and political spheres: they also want to promote the formation of autonomous mass organisations, but these are subordinate to the general line of the group, which claims to be the repository of the general vision” (statement by a comrade from the Sit-Siemens committee, Potere operaio del lunedì, no. 41, cit.).

[7] Statement by a comrade from the Enel committee in Rome, Potere operaio del lunedì, no. 41, cit.

[8] “As far as the groups are concerned, it must be said that, within the discourse on autonomy, the role of the groups has objectively come to an end. We must not fight them, but do them political justice” (statement by a comrade from the Workers-Students Collective of the Policlinico di Roma, “Potere operaio del lunedì”, no. 42, cit.).

[9] “The relationship with the groups must be seen solely in terms of these comrades’ willingness to actively pursue the workers’ objectives. I do not mean that the groups must in turn be at our service and do what we workers do not want to do in the factory. They must join our organisations and share their experiences with us, acting as a link between the struggle in the factory and that in the neighbourhood. The autonomous assembly does not present itself as an alternative to the union and the groups; it must present itself as a directly working-class organisation, and on this there is room for discussion with the groups and with certain factory councils” (statement by a comrade from Chatillon in Porto Marghera, “Potere operaio del lunedì”, no. 42, cit.).

[10] “For this reason, while recognising the profoundly different needs of the movement, today we cannot do without a political relationship with the organised vanguards, with the sections of organisation which, when they do not eliminate themselves by arrogating to themselves the role of the party of the class, are indispensable in the construction of what will be the workers” organisation of the communist revolution’. (statement by a comrade from the autonomous assembly of Porto Marghera,Potere operaio del lunedì, no. 42, cit.).

[11] The following autonomous organisations participated in the conference: the Autonomous Assembly of Alfa-Romeo, Pirelli, the Sit-Siemens Struggle Committee of Milan, the Autonomous Assembly of Porto Marghera, the Fiat-Rivalta Workers’ Committee of Turin, the Enel Political Committee and the Workers’ and Students’ Collective of the Policlinico of Rome, the Workers’ Committees of Florence and Bologna, the USCL (Trade Union of Struggle Committees) of Naples, the Red Leagues of the farmers of Isola Capo Rizzuto and Crotone, and the “Raniero Panzieri” Circle of Modena.

[12] Communiqué from the Organising Committee of the Conference of Autonomous Committees and Assemblies, “Potere operaio del lunedì”, no. 43, cit.

[13] Potere operaio del lunedì, no. 44, 11 March 1973. Editorial. However, Potere Operaio issued a stern warning: ‘It therefore seems essential to us that the comrades of the Committees address these issues at the conference and afterwards, not only in speeches but also in their political work. […] Otherwise, the controversy with the groups, with which some comrades of the Committees are so obsessed with, ends up being the pointing finger behind which to hide one’s own ineptitude. Because, let it be clear that in the absence of new things, the experience of some revolutionary groups remains the only fixed point from which to start in Italy”.

[14] Interview with a comrade from the Alfa autonomous assembly, ‘Potere operaio del lunedì’, no. 45, 18 March 1973.

[15] Dito

[16] The bulletin bore the signatures of the following organisations: Alfa Romeo Autonomous Assembly, Pirelli Autonomous Assembly, Sit-Siemens Struggle Committee, Fiat Workers’ Group, Porto Marghera Autonomous Assemblies, Enel Political Committee, Policlinico Workers-Students Committee, Trade Union Struggle Committees. On this subject, see Aut. Op.La storia e i documenti: da Potere operaio all’Autonomia organizzata, edited by Lucio Castellano, Rome, Savelli, 1980, p. 83.

[17] Il convegno dei comitati, ‘Potere operaio del lunedì’, no. 45, cit.

[19] G. Palombarini, op. cit., pp. 111–112.

The post An organisation of workers’ autonomy? – Historical texts and current considerations (1) first appeared on Angry Workers.

January 14, 2026

The Political Economy of the Current Uprising in Iran

Neoliberalism and the Architecture of Disaster, by Iman Ganji

We document a text sent to us by a comrade

Lead: With hundreds of protesters killed within days in Iran, amid a blackout imposed by a state that blocks any flow of information, parts of the international Left have rushed to pronounce judgments in a mode of immediacy that ignores history and misreads the situation. This article addresses one such claim: that Iran “is not capitalist,” has not undergone neoliberalization, and that sanctions alone explain its economic crisis—a statement that would bewilder any Iranian worker, but circulates unhindered among leftists in the imperial core. This text does not address two other determinants of the conjuncture: the reactionary political hegemony over the uprising and the role of imperialist intervention—both targets of other uninformed assessments in recent days. Denying massacres and neoliberal austerity does not serve the cause of anti-imperialism in the long term, even if realpolitik and geopolitical considerations push some toward immediate discursive interventions in the current situation. Statism is not internationalist solidarity. Nor does the immediate embrace of the situation as “revolutionary,” coupled with the dismissal of imperialism and fascism, serve the cause of revolution.

Iran, Angola, Ecuador, Bolivia in 2025. Angola in 2023. Kazakhstan and Jordan in 2022. Iran, Lebanon, Ecuador, and Zimbabwe in 2019. France, India, and South Africa in 2018. Mexico in 2017. Sudan in 2013. Nigeria in 2012. Bolivia in 2010. The United Kingdom, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Spain, and Russia in 2008. Iran in 2007. Yemen in 2005.

This is an incomplete list of countries where, over the past two decades, fuel price hikes and the removal of state subsidies have been among the triggers of subsequent protests and uprisings. Raising fuel prices is one of the recurring markers of neoliberal structural adjustment, and almost everywhere governments have taken this step, they have encountered popular resistance.

One country appears three times on that list: Iran. Do not listen to so-called regime experts who present gasoline price hikes under Mahmoud Ahmadinejad as a success story and count on our historical amnesia. On the night increases to the price of fuel were announced, people set fire to 12 gas stations in Tehran and chanted slogans against the president. Hence, the question naturally arises: given that historical experience, and in the midst of a suspended wartime situation with Israel, by virtue of what criteria and on what basis does the Iranian state decide to raise gasoline prices once more?

An increase in the price of gasoline was not even the sole element in the government’s structural adjustment policy: Currency devaluation and the removal of the preferential exchange rate for essential goods are two other key factors that have intensified the mass impoverishment of the population in Iran and have fed into the ongoing uprising in the streets of cities across the country.

Other, equally prominent, determining factors are at play in the situation in Iran. [1] None of this, however, negates the simple fact that the neoliberal policies implemented by Masoud Pezeshkian’s government — as with all previous governments since the end of the war with Iraq — with the cooperation of the rest of the state apparatus has provided both the primary social cause and the genetic grounds for the affective contagiousness of the ongoing uprising. Just as they have repeatedly done in the past, populations resist these policies, and do so with varying degrees of intensity. And the fact that state-repression successfully truncated previous waves of resistance does not mean that they will not resist again.

Poverty and misery, even when widespread, do not by themselves lead to uprising; and those who think that “sanctions” alone succeeded in driving the poor into the streets cannot explain the counterexamples. It is true that international sanctions have further worsened the economic situation on multiple fronts, though not in the reductionist way the received accounts portray. The decline in government revenues has produced a structural budget deficit, while efforts to bypass sanctions have generated rents that have transformed Iran’s political-economic order into an oligarchic system. Shock therapy, however, by deliberately producing a crisis of social reproduction (independently of sanctions, but especially under sanctions), leads to resistance and revolt — this is the first law of social thermodynamics. And do not imagine that the so-called economic experts who design these policies are unaware of this law. On the contrary: many policymakers and technocrats influenced by neoliberal economics and the Chicago tradition — including the current minister of economy, a graduate of the University of Chicago — are fully aware that anti-welfare reforms and shock therapy generate social resistance and political crises. Historical experience shows that in such models, reliance on police and security power is not accidental but a structural component of how these policies are implemented. The core idea is simple: the crisis produced by these reforms is not meant to be prevented; it is meant to be managed.

Yet the central question remains: how — in a wartime situation, and after rhetorically praising “popular unity” in the face of Israeli attacks — does the Iranian state decide to raise gasoline prices and abolish the preferential exchange rate? How does a government at war with an external power choose to wage economic war against its own populations rather than purchasing domestic peace through social welfare policies?

Pezeshkian has argued that he will carry out any policy with socio-political consequences; any “hard decision” that leads to “public dissatisfaction;” because he is only supposed to serve a single presidential term. This, however, is not merely a case of strapping a grenade to oneself and blowing up as an individual; it is a structural sign of what the author has previously analyzed, in terms of political economy, as a “suicidal state.”

The answer to this central question should be pursued in two parts. First — this article — we examine the recent genealogy of the current political economy and the policies of the past several years. This should be read while we keep in mind that There is a long trajectory behind Iran’s neoliberalization policies. Since the start of the revolution, para-statal military and religious foundations absorbed the assets of the previous regime, forming a parallel economic body. This body operates outside the legislative and administrative authority of the government, including the central bank, and is directly supervised by the Office of the Supreme Leader.

The parasitic relationship such foundations initially formed with the government reversed somewhere along the way, such that today it is the government itself that parasitizes these foundations, now transfigured into giant holdings, together controlling over 55% of the total GDP. [2] The turn towards privatization of the entire economy was implemented just as the eight year war with Iraq came to a close, and over the course of the next six presidencies, it came to exhibit all the hallmarks of neoliberalization – welfare retrenchment, the erosion of public infrastructure, and labor flexibilization. Crucially, structural adjustment was designed in such a way that the very foundations already dominating the largest shares of public property were able to consolidate and expand their control through opaque auction mechanisms in collusion with each successive government. This is the picture in which mechanisms of immiseration, impoverishment, and the accelerating class divide in contemporary Iran must be understood, lest we stay with broad unhelpful abstractions.

From Currency Policy to Structural Adjustment: Madani-Zadeh’s Suicidal Prescription for a “Sick Economy”

In this first section, we must turn to Seyed Ali Madani-Zadeh, a professor at Sharif University of Technology and a central figure for understanding the political economy that has led to both the current uprising and that of Aban 1398 (November 2019). Included among Madani-Zadeh’s achievements are the drafting and formulation of the ‘Framework for Structural Reform of the Budget with an Approach to Cutting the Budget’s Direct Dependence on Oil,‘ issued by the Plan and Budget Organization in Khordad 1398 (June 2019). This is a, high-level, policy document whose proposals began being implemented under Hassan Rouhani’s government, continued under Ebrahim Raisi, and is currently being carried out at full speed under Masoud Pezeshkian’s administration.

Among those responsible for Iran’s economic disaster, Madani-Zadeh has, in recent years, been its chief architect. For this reason, what follows will focus on this latest contemporary heir to the Chicago boys, in order to arrive at one part of an answer to our central question.

Structural Reforms

The Plan and Budget Organization’s document, “Framework for Structural Budget Reforms,” presents itself as a technical and unavoidable response to the state’s fiscal crisis compounded by economic sanctions. Its dominant language is one of necessity, discipline, and technocratic rationality — as if economic policy were not a terrain of conflicting social interests but merely a matter of calculation and management. Yet behind this neutral language lies a project that, both theoretically and in terms of policy design, clearly continues the model of IMF-style structural adjustment and the assumptions of neoliberal economics—especially in the Chicago tradition—albeit wrapped in localized terminology and the rhetoric of a “resistance economy.”

In fact, it is enough to compare Madani-Zadeh’s document with the IMF’s most recent Iran’s Article IV consultation report (2018) to see how, without ever citing the IMF, it structurally reproduces the same policy logic, priorities, and sequencing of interventions. The core of these recommendations rests on fiscal discipline, cuts to public spending, the primacy of austerity over growth, the weakening of universal social policy, and the transformation of social justice into a technical, targeted issue. The Plan and Budget Organization’s framework proceeds on precisely these assumptions. The main difference lies not in substance but in political context: what in Europe and Latin America was imposed through pressure from supranational institutions and financial markets is, in Iran, implemented within an authoritarian setting and through reliance on the state’s administrative and security capacities. From this perspective, we are facing a kind of “Article IV economics without the IMF”: the same structural adjustment logic, but without the IMF label and without the need for social consensus. Iran has followed IMF prescriptions before as well, and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was once praised by that notorious international institution for cutting subsidies and raising energy prices.

Let us now look more closely at the substance of the structural reform document. Its point of departure is the identification of a “core problem” — or, in Madani-Zadeh’s terms, the diagnosis of the Iranian economy’s main disease: the structural budget deficit. Inflation, economic instability, declining welfare, and even threats to people’s livelihoods are all reduced to this single variable, to this supposed “root evil.” This reductionism is not accidental. Within this framework, inflation is not understood as the product of distributive conflicts, power structures, sanctions, rent-seeking, or modes of accumulation, but as the mechanical outcome of the state’s fiscal indiscipline. And that, first and foremost, means removing politics from the analysis and reducing the economy to a technical domain.

From this diagnosis follows the prescribed cure: the establishment of a binding “fiscal rule” that pre-sets ceilings on government spending, deficits, and debt for several years in advance. This instrument, presented in neoliberal discourse as a guarantor of “credibility” and “stability,” in practice means tying the hands of future policymaking. Budgetary decisions — which should by their nature be political, distributive, and contested — are turned into quasi-constitutional rules that operate beyond social interests. Greece’s experience after the 2010 debt crisis clearly showed how such rules, even in formally “democratic” systems, can strip society of economic sovereignty and hand it over to technocratic and supranational institutions.

Subsidy reform and the “realignment of prices” constitute another pillar of this framework. Subsidies for energy and basic goods, along with non-cash forms of support, are all treated as “distortions” — distortions that must be eliminated so that prices can send the “right” signals. To contain the social fallout of this removal, targeted cash transfers are proposed — the very approach Pezeshkian’s government has pursued in the midst of protests. But this logic is exactly the same model implemented across Latin America since the 1980s, from Mexico and Argentina to Brazil: price liberalization, cuts to universal support, and minimal compensation for the poor, not as a social right but as a tool for managing discontent.

Within this framework, social justice is reduced to an administrative problem. The issue is no longer structural inequality, but “inclusion and exclusion errors;” not the concentration of wealth and power, but databse deficiencies. Social policy is downgraded from a redistributive project to a mechanism for managing the effects of austerity. Egypt’s experience after 2016 — combining currency liberalization, the removal of energy subsidies, and the expansion of cash-transfer programs — offers a clear example of how this combined set of policies can produce fiscal stability at the cost of rising poverty, food insecurity, and social dependency.

The institutional section of the document — performance-based budgeting, a treasury single account, a medium-term expenditure framework, asset sales through exchange-traded funds (ETFs), and the expansion of the debt market — aligns almost entirely with the IMF’s public financial management reform agenda. These reforms render the state more “legible” — thus, easier to monitor and discipline — at the cost of reducing politics to performance management and indicators. Hence, ministries become cost centers, programs become measurable outputs, and the budget turns into a managerial document. What is lost in the process is the conflict of social interests and the most fundamental question of social justice: who pays the price for these structural reforms and who repeats their benefits?

What is absent from the Plan and Budget Organization’s document is as telling as what it contains. Madani-Zadeh offers no serious analysis of the labor market, wage suppression, capital–labor relations, or the role of monetary and exchange-rate policy in wealth redistribution. In his framework, society appears not as a political actor but as a source of social risk that must be managed through “transparency” and “persuasion.” Sanctions, meanwhile, are treated merely as an “external shock,” rather than as a mechanism that reshapes accumulation patterns and rent extraction. Put more plainly, the document as a whole is a class project aimed at stabilizing the dominant class.

This framework implicitly relies on an authoritarian setting. In the absence of mechanisms for social bargaining, independent unions, and democratic accountability, austerity reforms do not proceed through social agreement but through administrative capacity and coercive power. The document’s repeated emphasis on “policy consensus” makes clear that the consensus that matters is not between state and society, but within the ruling elite — what, in the regime’s newer vocabulary is called vafaq (“unity” or “accord”). The reason is not hard to grasp: every historical experience, from Greece to Latin America to Egypt, shows that the costs of structural adjustment are systematically shifted onto the most immiserated segments of society.

In light of all this, the Plan and Budget Organization’s document—contrary to the neoliberal rhetoric of its advocates about “economic surgery”—does not mean a smaller state. Rather, as Michel Foucault showed in The Birth of Biopolitics with regard to the neoliberal state, it represents a reconfiguration of the state: a large, interventionist, yet disciplined, state; one that retreats from redistributive intervention while strengthening its instruments of control and surveillance. This model can be called “authoritarian austerity:” a model in which the global doctrines of structural adjustment are implemented in a non-democratic context, and social discontent is treated as a predictable cost. In other words, the structural budget reform framework normalizes crisis and turns austerity into permanent policy. Poverty, inequality, and livelihood pressure are not policy failures; on the contrary, they are manageable side effects of “good governance” — the very logic underlying Pezeshkian’s proclaimed “self-sacrifice” and his promise of a single-term presidency.

Exchange-Rate Policy

Like many economists who share his outlook, Madani-Zadeh identifies the budget deficit and the inflation it generates as the core disease, but treats price controls as the underlying cause of that disease. This view extends from basic goods and services all the way to the exchange rate. In one of his final interviews before taking office as minister of economy, he explained the Islamic Republic’s exchange-rate problem in precisely these terms: just as all prices should be left to the market, the price of foreign currency should not be set through mechanisms such as the NIMA exchange system or the preferential exchange rate. And if high inflation is the main problem, then it will necessarily be reflected in the exchange rate as well. In other words, for him and his allies, foreign currency is a commodity like any other — a claim fundamentally at odds with the realities of Iran’s political economy.

This discrepancy is not lost on Madani-Zadeh. In one study published under his supervision — where he appears as second author — this very inconsistency is, in fact, emphasized. The study, published in 2015, reaches conclusions that run directly counter to the policies he now advocates, and to those currently pursued by Iran’s economic system more broadly. In “Exchange Rate Pass-Through and Its Determinants in Iran,” Sajad Ebrahimi and Seyed Ali Madani-Zadeh examine the impact of rising exchange rates on producer and consumer prices — that is, the exchange-rate pass-through. In this research, they set aside the effect of the budget deficit — the same “supreme evil” said to drive inflation — and defend a multiple exchange-rate system under Iran’s specific conditions, precisely because it keeps pass-through low and avoids costly socio-political consequences:

In a multiple exchange-rate system, some imported goods and services enter through the official exchange-rate channel. As a result, changes in the unofficial exchange rate have little effect on the domestic prices of goods imported via the official channel. This implies a low exchange-rate pass-through.

They identify exchange-rate volatility as a key driver of higher pass-through, noting that “importers of goods and services respond more strongly to exchange-rate changes in order to hedge against the risk and uncertainty generated by exchange-rate movements, which leads to higher exchange-rate pass-through.” Another finding of the study is that, whether inflation is high or low, it has “no significant effect on exchange-rate pass-through.”

In short, maintaining access to foreign currency for importing essential goods and striving for exchange-rate stability — minimizing volatility — are crucial for limiting the impact of exchange-rate increases on consumer and producer prices, regardless of whether inflation at a given moment is high or low.

These findings stand in stark contradiction to all of Madani-Zadeh’s recent policies and recommendations. Eliminating preferential currency for importing essential goods will raise exchange-rate pass-through and lead to sharp increases in the prices of basic commodities — effects that will become visible within one or two quarters.

Moreover, Madani-Zadeh now argues that if an external shock hits the exchange rate, the price of foreign currency should be allowed to rise to its peak, after which the central bank should bring it down through a Dutch auction of dollars. He also insists that the exchange rate should be allowed to fluctuate, so that no one has an incentive to buy foreign currency — all policies that, according to his own 2015 research, will increase the impact of exchange-rate changes on domestic prices in Iran. Finally, his central focus on the budget deficit and high inflation has no bearing whatsoever on this pass-through effect.

These policies, however, have other consequences as well. The government claims that eliminating the preferential exchange rate will harm rent-seekers, who will no longer be able to profit from the gap between the subsidized dollar and the free-market rate. On paper, this claim is correct. What officials do not tell you is the policy’s real effect. After years of rent allocation, the import and export of many goods has already become highly concentrated and quasi-monopolistic. As the dollar price rises, this concentration intensifies, because a more expensive dollar pushes smaller players out of the market and leaves only large actors — capitalists with deep pockets — standing. They are the only ones able to afford the higher prices. Those who once operated at the level of hundreds of thousands of dollars in trade are forced out in favor of those dealing in millions. Moreover, as imported goods become more expensive, the profits these large players extract from selling them compensate for, if not exceed, the rents lost from the exchange-rate gap.

The policy of Dutch auctions in the currency market has similar effects. In these auctions, where the price starts high and sales occur where demand finally materializes, large players enjoy a clear advantage. Actors with deeper pockets, by they institutions or private capital, can tolerate more risk and make faster decisions, leading to further concentration of ownership in the hands of a few. The result is nothing but greater state dependence on a narrow financial network and the reproduction of rent. Dutch auctions are a crisis-management tool for financial markets, not a sustainable policy framework.

So Why?

The policies being implemented are not a response to the profound crisis of social reproduction as experienced by Iran’s proletarian and surplus populations, and at a moment when food inflation has exceeded 70 percent while prices for basic goods have risen by as much as 110 percent. Instead, these policies constitute a class-based project aimed at reproducing the state under crisis conditions.

The Iranian state has repeatedly gambled on shock. The subsidy-targeting plan under Ahmadinejad was on the agenda as early as 2008, but it was likely the burning of twelve gas stations that delayed its full implementation until 2010, during the Green Movement protests. The assumption was that society was already in shock, and that this was therefore a good moment to push through the reforms. During the 2022 protests, the exchange rate hit a historic high in Mehr of that year. This time, following Israel’s attack and amid a suspended wartime situation, the state placed yet another bet: assuming a state of shock, it moved to liberalize gasoline prices and raise the dollar, and amid the protests, eliminated the preferential exchange rate.

The current protests are not merely “economic.” Political economy gives shape to their political, social, and class dimensions. The suicidal state is not irrational; its rationality is simply limited to reproducing the state itself and its class relations, at the cost of producing death for the populations it is meant to manage. Till now, security forces have reportedly killed hundreds of protestors in the ensuing uprising.

Footnotes

[1] Including: the competitions among oligarchies; imperialist influence; and so on. In any case, the political hegemony of the protests currently lies in the hands of reactionary right-wing forces, and it does not yet appear that other forces will be able, in the very near future, to exercise counter-hegemonic agency and overcome the right. But these factors influencing the uprising’s outcome do not erase the class struggle that defines this revolt.

[2] Vahabi, Mehrdad. Destructive Coordination, Anfal and Islamic Political Capitalism. Cham: Springer International Publishing (Palgrave Macmillan), 2023, p. 300

The post The Political Economy of the Current Uprising in Iran first appeared on Angry Workers.

January 4, 2026

Venezuela – Class struggle against imperialism and the myth of national independence

The attacks of the US army in Venezuela are an expression of imperialism, but how can we respond to them? Understandably, the reaction of many people is to rally for ‘national independence’. From a working class perspective and the perspective of international emancipation, the battle cry for ‘sovereignty’ is a dangerous myth. The situation in Venezuela is part of a global panorama of block confrontation and as international workers we have to find ways not to get crushed in the middle.

Venezuela and China

One of the reasons given by the US government for fighting ‘communism’ in Venezuela is its close ties to ‘enemies of the US’: China and Iran. On the evening before his abduction, Maduro received a high-ranking Chinese delegation. Shortly after the meeting ended, he was sitting in a US army helicopter. China is now effectively the only relevant factor countering the current march of the US and US-aligned movements in Latin America (Milei/Argentina, Bukele/El Salvador, Nasrallah/Honduras, Kast/Chile, Mulino/Panama, etc.).

China currently imports approximately 80% of Venezuela’s daily oil production of 950,000 barrels per day (as of November 2025, i.e. before the first tanker was seized by US troops). There is no data whatsoever on the actual prices at which China has been buying Venezuelan oil over the last 10 years or at which the ‘enormous collection of goods’ delivered from China to Venezuela on credit (house hold appliances from Haier, Yutong buses, cars) is being charged. Even a factory for assembling Yutong buses was set up in Yaracuy in 2015.

In Chancay, Peru, the Chinese logistics giant COSCO operates a large deep-sea port 100 km north of the capital Lima. From there, the voyage to China takes 23 days, down from 40 days previously. In Panama, the US wants to oust China from the two ports at either end of the canal (Colón and Balboa). Meanwhile, Black Rock/MSC and COSCO are fighting over the shares. Panama has left the Chinese supply-chain project ‘Silk Road’ again.