Nigel Foster's Blog

September 15, 2025

Puzzling Color

I have long been curious about water. It is such an enigmatic fluid. It falls from the sky, flows in rivers to the seas and oceans where it circulates, its surface blown into waves by the wind. Water evaporates and condenses as clouds.

Water looks clear in a glass.

Water looks clear in a glass. Our bodies are about sixty percent water. We drink it, swimin it, bathe in it. I like to paddle my kayak over its surface. But what coloris it? Is it colorless, as it sometimes appears in a glass? If so, why does thesea sometimes look blue, sometimes green, sometimes grey?

Water sometimes looks green, or blue.

Water sometimes looks green, or blue.I am not alone in pondering. More than two thousand yearsago, in the 1st Century BC, the poet Lucretius puzzledover the nature of water. He wrote in his poem, De Rerum Natura Book II,(translated as ‘On the Nature of Things’), “If the oceans are made up ofblue matter, however we manipulated them we would never see them in othercolors. How can we see water as white if it is made up solely of azure, blue?Yet on rough days, do we not see the oceans marble white?”

Water can look white.

Water can look white.The surface of water reflects light, but light alsopenetrates. Short wavelengths of light penetrate farther than long wavelengthsbefore being absorbed, the light energy converted to heat.

Long wavelengths, such as red light, penetrate only thesurface layers of water, while shorter wavelengths, such as blue and violetpenetrate deeper before being completely absorbed. Divers at depth must carrylights to reveal colors other than shades of blue. Blue light scatters withinwater, bouncing off the water molecules, so when we look down into deep clearwater, we see it as blue. It is blue from within, not just from reflected bluesky.

Deep, clear water can appear blue, not in shallows.

Deep, clear water can appear blue, not in shallows.The water I kayak on seldom appears blue when I look closely. Sometimes it looks green, cyan, yellow, or orange

Orange tannin-rich water in Florida.

Orange tannin-rich water in Florida.Artists employ a wide palette of colors to realisticallydepict water.

Monet: 'Cliff Walk at Pourville, with detail, left.

Monet: 'Cliff Walk at Pourville, with detail, left.The detail, above left, reveals that Monet used at least white, twoshades of green, teal, two of blue and a lilac color, in short brushstrokes, toachieve the overall impression of a choppy sea. The colors change with waterdepth, and with distance.

Turner:Venice, the Dogana and San Giorgio, with detail, left.

Turner:Venice, the Dogana and San Giorgio, with detail, left.In the detail from Turner’s painting of Venice, the water ispea-green, yellow, and blue, indicating the shallow depth and the reflectivesurface. Elsewhere on the full picture Turner used additional colors to representreflections of boats and buildings.

When we look at the sea, sometimes we see it as monochrome blue, or green, but is it really? Both these artists recognized that water is not monochrome. The colors are complex: a mixture of what lies on the surface, what is within and what lies beneath, with reflections adding complexity. So, what color is water?

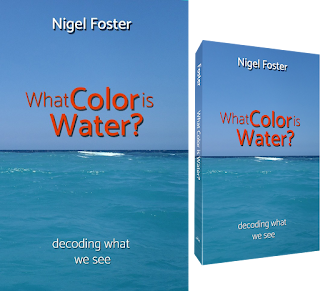

The book: 'What Color is Water?' explains the chameleon nature of water. Lavishly illustrated, it highlights the properties of water and questions how reflections, and what lies on, and under the water, affect the colors embodied in sunlight.

Interested in: 'What Color is Water?' Order a copy from your local bookstore, or purchase online.

What Color is Water? by Nigel Foster

What Color is Water? by Nigel Foster

November 21, 2023

Writing and Publishing Books

Always writing; one of my “bucket list” dreamswas to publish a book. It’s the kind of project that requires time, and acertain amount of persistence.

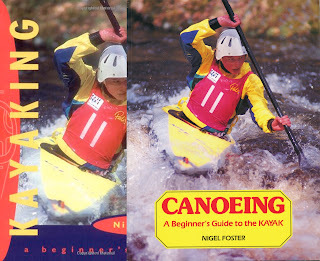

Some of my titles on my parents' bookshelf

My first book was a technical kayaking manual for beginners.It presented me with two major challenges. First, how to explain how to performeach maneuver, in as much detail as seemed appropriate, and to arrange everythingin logical order throughout the book. Second, how to best demonstratethe essential points of each maneuver, in my kayak, for a photographer tocapture in a sequence of photos.

I wrote my first books longhand, ink on paper

Cut and Paste

My publisher requested each chapter, typed, double-spaced,as soon as completed, so he could follow my progress. I wrote longhand onpaper, crossing out and writing between the lines until the page became toooverwritten to be usable, at which point I made a clean handwritten copy.Sometimes I cut out sections and pasted them onto a sheet of paper in adifferent order. I used a pen, paper, scissors and glue.

When I was satisfied with what I had written. I typed out eachpage carefully, on a typewriter. No typist, I worked slowly using just two fingers,so the typewriter arms/keys would not jam, and with plenty of white correctionfluid painted over mistakes.

Inevitably I made last-minute changes to almost every page, rendering them too messy to send. That typing stagetook a long time. I duly folded the sheets of each finished chapter into anenvelope, addressed it, attached a postage stamp, and mailed it.

PhotographsAfter I had submitted the whole manuscript, my publisherbrought a photographer to North Wales. Over the course of three sessions, she shotall the technical sequences to illustrate the book.

In those pre-digital days, there was no way to view anyimages until the rolls of film had been sent away to be developed, and contactprints made of each roll. The film was 135, commonly called 35mm. The contactprints, which arrived by mail, were positives of exactly the size of theoriginal negative, each monochrome image just 24 by 36mm, although they wouldbe enlarged for the book.

35mm camera film contact print sheet

35mm camera film contact print sheetWith a magnifying glass, I identified all the photographs,cut them out and pasted them onto paper, in the correct order for the chaptersof the book. I then labeled the frames we should use from each sequence andadded captions. With 13 chapters, the book was lavishly illustrated with 280photographs, including inspirational action shots.

Canoeing was released in 1990with an initial print run of 5,000 copies. Sold out and reprinted within 6months, the book’s success prompted the publisher to ask if I had any otherbook ideas. Sea Kayaking, Open Canoe Technique and NigelFoster’s Surf Kayaking followed. It was the book on canoeing technique thatfinally sparked my first book to be less ambiguously retitled Kayaking.

My first books were published by Fernhurst Books in UK

My first books were published by Fernhurst Books in UKFernhurst Books collaborated with Globe Pequot Press to increase visibility inthe USA, and Globe Pequot opened up new opportunities for me.

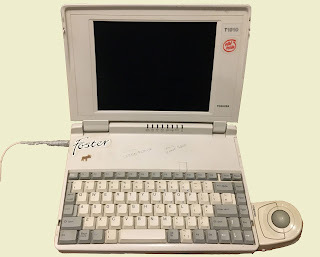

ComputersFor me, the writing process became easier when I bought alaptop. It was a Toshiba PC with 4MB RAM and 120MB hard disk, running both DOSand Windows 3.1 operating systems. It had a version of a mouse, or touchpad, which clipped onto the side of the laptop, with a ball on the top.

The screen was mono. The battery typically lasted for 8hours of use on one charge. I carried a spare battery and a portable printer whenI traveled.

My first laptop, mono screen, 120MB hard drive.

My first laptop, mono screen, 120MB hard drive.Typing on a computer keyboard was much easier than typing on a typewriter even though at that stage I still found it easier to arrange my thoughts with pen and paper first. The ability to print out the complete requisite physical copy of a book manuscript, double-spaced, for a publisher, was a huge saver of time and effort. But a book, albeit without the color slides or prints, would fit on a single floppy disk which was easier to mail. The publishing industry seemed reluctant to change.

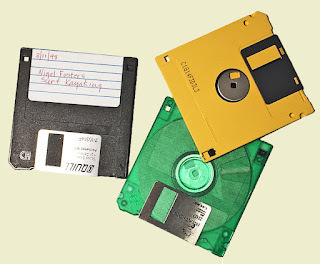

But, although a double-sided high density 3.5-inch floppydisk, with 1.44MB, could store the draft of a book, that would be withoutimages. Color slides and film negatives still had to be physically mailed. Ofcourse, optical storage in CDs and DVDs, with their far greater memorycapacity, superseded the magnetic storage on floppy disks, and digital camerasbecame more available and affordable.

Nowadays it is possible to email a manuscript. Photography is digital and images can be shared from computer to computer. Nothing needs to be physically mailed until a book is in print. 3.5 inch floppy disks

3.5 inch floppy disksSelf-publishing option

My next experiment in authoring came when, failing to find apublisher, I considered self-publishing the story of my kayaking expeditions toBaffin Island and Labrador, as Stepping Stones. I found a company, Outskirts Press, whichoffered self-publishing for a price, with a menu of options to choose from,such as cover design, interior layout, indexing, and so on. Each book sold wasprinted on demand and shipped by the company, with a royalty paid to theauthor.

I was curious to discover whether that was a viablealternative to using a mainstream publisher. Each appeared to have pluses andminuses. Mainstream publishers paid in-house editors, and designers for coversand book layout, and had all the marketing and bookstore distribution set up. Publisherspaid an author an advance of royalties, which reflected their commitment togetting the book out there to be sold. But each book inevitably took on thepersonality of the publisher and its staff to a varying degree, with give andtake. Was that an advantage or disadvantage? I would prefer my books to expressonly my own thoughts in my own words.

Stepping Stones, and later, On Polar Tides

Stepping Stones, and later, On Polar Tides

With a self-publishing service, I would have to pay upfront for any editing,help with cover design, and interior page layout. I would be responsible forall my own marketing. I would accrue higher royalty rates, but would that overcomethe extra outgoings? I could buy and sell books myself but would also benefitfrom the company’s own distribution. I would run the risk of the book not beingconsidered credible if self-published.

In my favor, I had several books already published bymainstream publishers, and I was well known in my field. For different price points,I calculated how many books I would have to sell to break even, and how many moreI would have to sell to match what I might otherwise expect in advance. It isimpossible to foresee sales figures, but I decided to give self-publishing mybest try. At the least it would be useful research. I considered the results asuccess.

I often wonder how Stepping Stones would have sold iforiginally published by a mainstream publisher. As it happens, it was later releasedby Falcon Guides as On Polar Tides. With the additions of story elementsFalcon recommended, and an insert of color images on glossy high-quality paper,the finished book is better designed and produced than its predecessor. Publisherscertainly have skilled and experienced staff. Falcon published my next twobooks. My best book on kayaking technique so far was one of them: The Art of Kayaking.

Amazon print on demandAt the onset of covid19, I returned from Sumatra, Indonesia,having agreed to write something about kayaking on Lake Toba, the biggestcaldera lake in the world. At 60 miles long, Lake Toba sits in the bottom ofthe crater of a super-volcano in Sumatra. The expedition I had been invited tojoin, and write about, was supported by National GeographicIndonesia, among others.

Initially envisaging a magazine article, I soon becameengrossed in my research of the Batak people around the lake, with their rich culture and history. Faced with travel restrictions, I took time to dig for hard-to-find information,and soon had more than enough material for a book.

I had no illusions about my chances of a positive responsefrom a publisher to a proposal about an expedition on a lake in a remote placefew people have heard of. Besides, at that time, which aspiring writer wouldnot be taking advantage of a Covid lockdown to send off multiple book proposals?Acquisition editors must surely have been inundated.

Having completed my draft, I learned, with the help of aretired book publisher friend, how to format a book ready for publication usingMicrosoft Word. I planned the interior layout, designed a cover, bought myISBN, and uploaded my files onto Amazon KDP.

Heart of Toba was the first book I published with Amazon KDP

Heart of Toba was the first book I published with Amazon KDP

Amazon’s print-on-demand service is an interesting way topublish a niche book. There is no upfront charge for anything. If you, as anauthor, can do all the grunt work, writing, editing, formatting, indexing etc.,you can upload just two PDF files and publish without any expense. I orderedproof copies of Heart of Toba, to see exactly how the cover and interior would look, in time to makeany adjustments before publishing.

Amazon prints books in various locations around the globe. Abook bought in Australia will be printed there. Purchase in Germany and thebook will be printed in Germany. This reduces shipping time and cost.

The traditional publishing model would be to print, often inAsia, a predetermined number of books, based on anticipated sales, and to deliverto customers via a distribution center in the home country. An internationalbook distributor would handle overseas orders, but that could affect theavailability, price, and delivery time. With a wide variety of paper types andbook bindings to choose from, offset printing offers more options and can produce higher quality results,but I have been happy with the print on demand quality of the three titles Ihave with Amazon.

With my first Amazon title successfully launched, and and still travel restricted, I next wrote Kayak across France, preparingmonochrome images from my digital color photographs to illustrate the story ofthe journey across France from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, via theseventeenth century canal du Midi and onward. I would now discover how well print-on-demand tackled images.

Kayak across France, best appreciated with a glass of wine!

Kayak across France, best appreciated with a glass of wine!

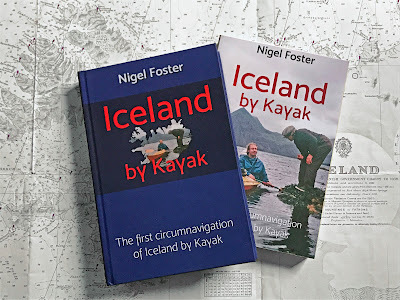

Iceland by Kayak

I have since published my third book with Amazon KDP: Icelandby Kayak, about the first circumnavigation of Iceland by kayak. I began preparing the book with the help of the books and charts Iused when planning the trip, and the journals I wrote along the way. Myoriginal color slides and monochrome 35mm film needed cleaning and scanning. When I published, I realized it had taken me 46 years to transform my journal and subsequent research into a book.

Since Amazon now offers hardback in addition to paperbackand digital options, I chose to publish Iceland by Kayak in hardback first, issuingthe paperback later. I am particularly pleased with the quality of the hardback.

Iceland by Kayak, a fun trip and a fun story!

Iceland by Kayak, a fun trip and a fun story! Conclusion

Having crafted multiple books over the years, the first withpen and paper, I have benefited from the advances which technology offers thewriter. Yet the basic process remains the same. We need to find the right story,the appropriate words to tell it, and a way to present everything in an attractiveand engaging way.

BUY Iceland by Kayak

BUY Iceland by Kayak

November 1, 2023

What Happened to the Royal Sovereign Lighthouse?

The Seven Sisters Country Park, inthe south of England, features precipitous chalk cliffs, where the sea has cutinto the undulating dry valleys and ridges of the south downs. To the east ofthe seven sisters, the cliffs peak at Beachy Head. At 530 feet high, this isthe tallest chalk cliff in England. Diminutive by comparison, a red and whitepainted lighthouse stands below on a wave-cut ledge.

This elegantly taperedgranite tower was the last traditional offshore lighthouse to be built by TrinityHouse in this tower style. Starting operation in 1902, it replaced the earlier,1834, clifftop Belle Tout lighthouse. Belle Tout was frequently obscured by seamist, and, inconveniently, was out of sight of ships passing close to the rocksbelow. The newer lighthouse was better placed.

Belle Tout,however, is still there, currently operated as bed-and-breakfast accommodation.In 1999, when threatened by cliff erosion, the 850-ton structure was movedinland 56 feet. The cliff erodes with abig collapse periodically, at an average of about two feet per year. Sooner orlater the lighthouse will need to move again, or it will end up at the bottomof the cliff.

Kayaking beneaththe cliffsWhen I lived insoutheast England, I rated Beachy Head and the Seven Sisters as one of the mostscenically attractive sections of the coast within easy reach by kayak.Launching onto the River Cuckmere at Exceat Bridge, to the west, a round tripto Eastbourne beneath these amazing chalk cliffs measured about fifteen miles.

In those days,three keepers manned the lighthouse which was powered by paraffin (Kerosene),until a supply of electricity reached the lighthouse in 1975. I moved away fromsoutheast England before 1983, when the lighthouse became fully automatic, andthe keepers were no longer needed.

Birling GapAt Birling Gap,between the Seven Sisters cliffs and Beachy Head, a hamlet with road access perchesin a dry valley at the cliff-edge. Many of the original buildings have already beentaken by cliff falls.

There wasusually a temporary flight of steps of some kind from the cliff top toaccess the beach. Since the sea frequently damaged or washed away the steps,access was never guaranteed. The carry down, and back up was often awkward tonegotiate with kayaks, especially when replacement steps took tight turns. We used this launch place to catch the tide eastpast the Beachy Head lighthouse, with its ledges and overfalls, toward theRoyal Sovereign shoals offshore Eastbourne.

The RoyalSovereign Shoals.The Royal Sovereignshoals are littered with wrecks. From 1875 onward, a lightship was mooredthere to alert ships of the dangers. The most recent lightship to serve there resembledthe Varne lightship, shown. The Varne marked a point roughly midway betweenEngland and France, a comforting confirmation of our progress when I first crossedthe English Channel with friends in 1974.

Varne lightship, Mid-English Channel

Varne lightship, Mid-English Channel

The RoyalSovereign lightship was replaced by a lighthouse in 1970. As a teenager at that time, I was fascinatedby the plans for how that lighthouse would be constructed, and how it would bepositioned on these always underwater shoals. It would look quite different from a traditionaltower lighthouse.

1967 Admiralty chart shows Beachy Head and Royal Sovereign shoals

1967 Admiralty chart shows Beachy Head and Royal Sovereign shoals

The structure was built intwo parts, on the beach at Newhaven. The hollow base, with the column attached,was towed out to the shoal. The base, once flooded, sank onto a leveled area ofshoal.

The second part of thelighthouse, a rectangular cabin section with a helicopter landing pad, andlight tower, was towed out later. At high tide, this structure was held abovethe base until the falling tide dropped it into position on the column.Finally, the telescoping inner section of the column was jacked up by 43 feetand cemented into its elevated position.

The lightship was towed away when the lighthouse began service in September 1971. The lighthouse, provisioned by helicopter, was manned by three keepers. The whole construction procedure was filmed and can be seen on YouTube (22 minutes)

Royal Sovereign Lighthouse

Royal Sovereign LighthouseA closer look

This unusual lighthouse stood tantalizingly within reach by kayak, just 6 miles offshore from Eastbourne. In March 1976, I left from Eastbourne to see it up close, timing my crossing to arrive at slack tide. Eastbourne offered an easier solo beach launch than Birling Gap with its steps.

The tides may have run as forecast that day, but the weather certainly did not. The wind picked up from the southwest, kicking up a sea. My spray deck leaked, and with so much water washing over, my cockpit began to fill. I carried a sponge, but when I unsealed my spray deck, waves flooded the cockpit faster than I could bail. I gave up and pushed on.

My kayak had a bulkhead immediately behind the seat, and another beyond my feet, so although water could not flood the whole kayak, it drained forward. The deeper the water grew in the cockpit, the more it weighed down the bow, and the more forcefully the kayak weather cocked away from where I wanted to go. It was a tough paddle back.

A lesson learnedThat experience got me thinking not only about a better spray deck, but also about bilge pumps. Preparing to circumnavigate Iceland by Kayak the next year, 1977, I deck-mounted a Henderson Chimp pump on my new kayak.

Deck-mounted bilge pump with red and black handle

Deck-mounted bilge pump with red and black handleThis kind of pump made it possible to empty a cockpit without removing the spray deck. Easy enough to operate when rafted to another kayak, it was challenging to use when balancing in rough seas, solo. I next experimented with foot-operated pumps which let me continue paddling while pumping.

Kayaks approach lighthouse

Kayaks approach lighthouseVisiting the keepers on the platform

In April 1976, I paddled out to the Royal Sovereign lighthouse again, this time with friends. With visibility limited to four miles, I called the coastguards beforehand to inform them of our plan. With gifts of newspapers and fresh milk, we paddled into the fog on a compass bearing. On reaching the lighthouse, we climbed out onto the ladder on the outside of the column. Having tied our kayaks, we scaled the ladder to knock on the door. Welcomed, we were invited inside and treated to a tour of the lighthouse, and a cup of coffee.

By the time we clambered back down the ladder, the tide had turned, carrying our kayaks out of sight behind the pillar. Anxiously, we hauled on the lines, relieved to find the kayaks still firmly tethered.

When crossing from Eastbourne, the tide offered little assistance. But on the 18-mile round-trip from Birling Gap it gave us a helpful boost, especially past Beachy Head. The extra miles compared to a round trip from Eastbourne were more than compensated for by the assistance of a spring tide. We timed our launch from Birling Gap, on the flood tide, to round the lighthouse at high water slack and return with the ebb. Birling Gap became my favorite launching place.

The Royal Sovereign lighthouse was a great target for a fun day trip by kayak, but times change. The light was automated in 1994, and from 2006 onward everything was controlled from shore. Full-time keepers were no longer needed, and the lighthouse remained unoccupied except, occasionally, for maintenance.

The concrete Royal Sovereign lighthouse, state-of-the-art when built, deteriorated more rapidly than the granite Beachy Head light tower. It was only designed to last for 60 years. Royal Sovereign was taken out of service on March 21, 2022, and scheduled for removal.

Removal is expected to take three summers, while buoys, north, south, east, and west cardinals mark the shoals. Will there be another lighthouse there? Unlikely. Since ships carry far better navigation systems than in the past, a lighthouse here is considered redundant.

The first stage of deconstruction began in October 2023, with the removal of the rectangular top section. For now, only the column, on its base, remains. Has anyone been tempted to paddle out to see it before the column is removed?

If you are interested in learning more about the lighthouse, Bexhill Maritime offers a wonderful description.

July 22, 2023

Sculling

What is Sculling?

I don't mean saying cheers in Swedish: skål, or Icelandic: skál. Sculling is a term used to describe two ways of propelling aboat using oars. One of those can also be used to propel a boat using apaddle. As a kayaker and canoeist, I'll focus on efficient paddle technique, but here is some context first.

Sculling or rowing?Technically, there is a difference between sculling androwing, particularly in competition, although the two terms are often used indiscriminately. Rowing (or sweep rowing) requiresat least two oars, one oar for each rower. In other words, at least two people are needed to row, one oar each side. Only one person is needed to scull, using a pair of oars, one ineach hand. But there is another way to scull. A single person can propel aboat using a to-and-fro movement with one oar, usually over the stern, although sometimes at the bow or over the side.

Grab and pull method. (Or grab and push).The sculler, facing the stern of the craft, grabs the waterwith both blades and pulls against them to propel the boat forward. Thefamiliar sight of racing sculls with the scullers sitting low to the water, facing the stern using two oars, is a classic example, but many people scullsmall boats using two oars while facing forward. In this case the sculler grabsthe water with both blades and pushes the craft forward.

The three scullers facing the stern of the green boat worktwo oars each. The helmsperson (coxswain) in the back faces forward. Venice Italy.

The three scullers facing the stern of the green boat worktwo oars each. The helmsperson (coxswain) in the back faces forward. Venice Italy.

Side-to side method, single oar.

The sculler swings a single oar thwartwise (from side toside) with the blade aligned to push the boat forward with every sideways swing.

Sculling a sampan with a single oar over the stern, using aside-to-side movement. Suzhou China.A combination of the two techniques

Gondoliers use a modified version of sculling, using asingle oar while standing in the stern facing the bow. They use the scull witha rowlock (the forcola) to one side of the stern, using a combination of the “grabthe water and pull” action, and the “to-and-fro” movement. They never switchsides and mostly keep the blade in the water during recovery between strokes.The gondola is asymmetrical to make steering easier since the gondolier usesthe oar to both propel and steer, always on the same side. The elevatedposition of the gondolier allows the oar blade to stay closer to the hull, makingthe gondola easier to navigate through the narrow Venetian canals. A sculler ina racing scull sits low, the oars reaching wide.

A gondolier sculls using a single oar to one side of the hull near the stern. Venice Italy.Over-stern sculling

A gondolier sculls using a single oar to one side of the hull near the stern. Venice Italy.Over-stern scullingAll over the world, especially in Asia, a similar scullingmovement is used over the stern of the boat. The back of a single oar or paddle,whichever is used, is engaged in a pushing mode. The leading edge of the oar isslightly closer to the stern than the trailing edge.

Sculling a Sampan with single oar blade in pushing mode atstern, Suzhou China (Above and in Video below)

Sculling a Sampan with single oar blade in pushing mode atstern, Suzhou China (Above and in Video below)Over the bow sculling

Coracles are circular, bowl shaped, so the bow in this case is more of aconcept rather than a design feature. The paddler kneels or sits, sculling thecraft with the face of the blade engaged, in pulling mode at the front. Thecoracle is used for fishing with a net, when the short paddle used single-handedlyfrees the other hand to work the net. Coracle - Wikipedia.

The sculling draw, to move sideways.Canoeists and kayakers use sculling to pull their craftsideways with the face of the blade engaged. (We also use a similar blade actionbut starting with the blade flat on the water and moving the blade across thesurface in the manner of a knife spreading butter, to aid or to recover balance.I’ll go into how to use that, another time.)

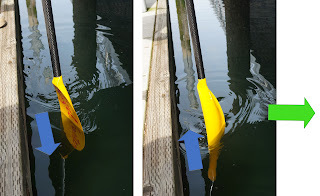

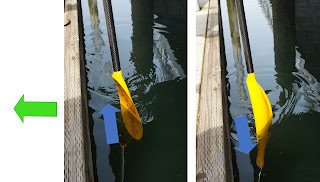

The blade action is a to-and-fro movement, with a slightadjustment of blade angle with each swing. The blade movement is most easilyunderstood if we first imagine a pendulum action with the blade in neutral. Thatis, sliced edge-first with no pressure on either the face or the back of theblade.

If we angle the leading edge of the blade slightly away duringeach swing of the pendulum, the blade will try to climb sideways away from us.This is the pulling mode. This is the style used to pull a canoe or kayaksideways, or a coracle forward.

Pulling mode, heredragging the dock toward the right. For clarity, blade is shown partly immersedbut it should be fully immersed when in action

Pulling mode, heredragging the dock toward the right. For clarity, blade is shown partly immersedbut it should be fully immersed when in actionIf we angle the leading edge of the blade slightly closerto us than the trailing edge, the blade will try to climb sideways closer tous. This is the pushing mode, used for over-stern propulsion, and also to pusha kayak or canoe sideways.

Pushing mode, here pushing the dock toward the left. Forclarity, blade is shown partially immersed. It should be fully immersed inaction.Refining the paddle stroke.Keep blade upright to go sideways, or flat to aid support.

Pushing mode, here pushing the dock toward the left. Forclarity, blade is shown partially immersed. It should be fully immersed inaction.Refining the paddle stroke.Keep blade upright to go sideways, or flat to aid support.The stroke is most effective at pulling the craft sidewayswhen the blade is held upright: perpendicular to the water, with the bladefully immersed. The closer the bladeangle approaches horizontal, the less effective it gets at pulling sideways; itclimbs to the surface rather than sideways from the craft. When it climbs tothe surface it may be used to aid balance or recover it. A 45-degree angle tothe water surface will offer a lot less sideways pulling effectcompared to a 90-degree angle.

Here, the blade is used one-handed in pulling mode, the shallow waternecessitating a low blade angle to the water of about 45°. While less effective at this angle, you'll notice it did offer some balance support. Lake Toba Indonesia

Positioning the top hand directly above thebottom hand throughout the stroke will prioritize the sideways pull, while lowing the top hand to thelevel of the deck will make the blade more useful in maintaining balance.

To maximize sideways movement, rotate your torso to faceyour direction of travel, hold your top arm straight, horizontal at shoulderlevel, over the water perpendicular to the side of the kayak. Control the blade angle withyour lower hand. Pause momentarily at the end of each swing while you changethe blade angle.

Try using the paddle in the manner of a pendulum, with the tophand in a fixed position and compare the effectiveness to when you move botharms together, keeping the top hand vertically above the bottom hand. Doestorso rotation help your draw stroke?

Figure of eight. Watch your blade carefully throughout the stroke. During thepause at the end of each swing, when you change the blade angle ready for thereturn swing, your kayak or canoe will slide closer to the blade. To allow forthis, the blade must creep a little farther from the hull during the followingswing. This makes the motion of the paddle naturally describe a figure of 8, (8 onits side against the hull as shown) even when you try to simply pendulum the blade in straightlines.

Watch your blade carefully throughout the stroke. During thepause at the end of each swing, when you change the blade angle ready for thereturn swing, your kayak or canoe will slide closer to the blade. To allow forthis, the blade must creep a little farther from the hull during the followingswing. This makes the motion of the paddle naturally describe a figure of 8, (8 onits side against the hull as shown) even when you try to simply pendulum the blade in straightlines. There is no need to deliberately focus on describing a figure of 8 withthe blade, as this will occur naturally. Any deliberate pull toward the hull at the end of each swing will tend to makethe kayak yaw while moving sideways.Steering while moving sideways

You can steer by sculling with a lesser blade angle in onedirection than in the other. You can also turn by sculling only at one end ofthe craft, leaving the other end almost stationary. Play with it!

Find more tricks and tips in my book, The Art of Kayaking.

Learn more about the author at nigelkayaks.com

March 8, 2023

Listen to your paddle. Kayaking and canoeing tips.

Learning to feel. Blind people learn to read Braille with their fingertips, rapidly scanning patterns of bumps, gathering meaning as I do when I sight-read a book. On the street, a blind person surveys their surroundings with a cane.

So, how much information about the water does a kayaker or canoeist gather in this way from their paddle? As a beginner, only a little, but more with practice.

Imagine standing with your paddle on the end of a dock with your eyes shut. You reach down to dip your paddle into a current flowing past the end of a dock. You should be able to feel the direction of the current, and whether the current is fast or slow, and if the water is turbulent. Would you be able to feel if there are waves? If so, could you gauge their size, and direction? Imagine holding your paddle lightly in your fingers, and then with a fist grip. Which offers the more sensitivity?

A light grip offers most sensitivity.

A light grip is key to fine blade control. It allows us to tweak the blade alignment to get the maximum grip against the current. Holding gently, we feel whenever the blade starts to pendulum, or trembles dragging against the current. We can twist the blade, edge-on to the current to find its angle of least resistance and steer it through tumbling currents while maintaining least resistance. It is easier to be accurate when we have a loose rather than tight grip.

Keep a loose hand grip.

Just as we rarely look at our feet when walking, we do not watch our paddle constantly when we kayak; we mostly look ahead. We feel the water through the paddle. Sure, our sight and hearing reinforce or confirm what we feel, but we cope surprisingly well in the dark, or when our hearing is impaired by hat or helmet, or when we paddle with our eyes shut.

So, how different will the water feel when we transfer from dock to kayak? While the dock stays fixed, our kayak moves. We place the blade to pull ourselves forward, to push back, or to turn. When we do this, do we feel the water as if it were something solid to lever against, or something that gives, letting our blade drag as it did when we stood on the dock? Or do we feel a bit of both? What happens when we pull our paddle hard against the water, compared to when we pull gently?

Feel how the blade interacts with the water.

Confronting such questions will help us understand what is going on and help us maximize the effect of our paddle. Pull or push the paddle hard and the water moves. Better use that energy to move the kayak, not the water. To be efficient, we should minimize how much water we move, while maximizing how much we move the kayak. We find that balance by feel.

Only then can we can choose whether to use our energy to move water or not. Beyond a certain point, more exertion churns the water, making noise but adding little to our speed. When we ease off until our paddle strokes become quiet, we move very little water, sacrifice only a little speed, and save a lot of energy.

Feel how the blade reacts in the water, and how the kayak responds, then tweak the angle accordingly.

Blade alignment

Whitewater slalom competitors work to maintain optimum blade alignment through complex turns in turbulent water. Imagine underwater you are trying to catch the current in your hand. You can move your hand to find the angle at which the pull of current is strongest. Whitewater paddlers feel and take advantage of the changing direction and strength of currents, feeling the water through the palms of their paddle blades. To cross an eddy line, they must get their angle of approach right, make precision blade placements, and nail their timing. They constantly adjust blade angles to best catch the currents, which swirl and surge. With experience, they anticipate those currents, but they fine-tune by touch.

Look where you are going and feel the water with your blade.

With practice, many of the details they feel, and act upon, become so familiar they blend to become automatic. The changes in water pressure on the blade trigger unconscious responses.

You rarely need a fist-tight grip.

Watch an expert play on a rapid and everything looks effortless, as if the current slows down for them. Most of their sensing and responding is done unconsciously. They work with the water. In contrast, a beginner in the same space often fights the water. Overwhelmed by the burden of consciously gathering and processing all the details, paddling become crisis management. So, how do we best progress from fighting the water to working with it?

Here are some tips:

1. Much of paddle control is done by feel. Learn what to feel for. A good instructor should be able to guide you.

2. Listen to your paddle. It makes more noise when you move water.

2. Focus on feeling the water through your paddle with every stroke. A light grip with fingertip control will enable the most feedback.

3. Note what you feel, then try to put it into words. For example, you might observe: “the paddle starts to shake toward the end of my paddle stroke”. Or: “I splash water at the start of each stroke.” Awareness is crucial.

4. Question each effect you notice and decide if it is desirable. Will your stroke be more effective if you try to make this happen more, or less? How would you achieve either outcome?

5. Aim to move the kayak rather than the water.

When you apply your skills to the waters you wish to paddle, whether calm or rowdy, always question what is going on. Once you can interpret, evaluate, and respond to all the signals that come from the water through the paddle, the paddle will become an extension of your body. Use your paddle to seek maximum effect for minimum effort, and work in harmony with the water.

You can learn a lot even without your kayak.

Learn more from my book The Art of Kayaking, Find me at nigelkayaks.com.

November 18, 2022

Inspired by books: The Northern Lights

I began to read books about kayaking adventure, and on kayaking technique, in my teenage years. Nowadays, many of the books, both old and new, on my shelves are about travel exploration, and often relate in some way to kayaking, sailing, mountaineering, or the arctic. Inevitably one adventure leads to another, just as one explorer inspires others. The stories in these books frequently overlap, or cross reference the adventures of others. I enjoy following the links; those little cross-references that spring up unexpectedly between them. In that way my collection has grown and diversified.

The northern Lights begin to glow over northern Labrador

The northern Lights begin to glow over northern Labrador

I am not alone in my delight. My friend Kevin Mansell, from Jersey in the Channel Islands, has a similarly diverse and prized collection, although most likely fuller than mine.

In New Zealand, I have seen Paul Caffyn's enviable library. Both Mansell and Caffynl are personally familiar with adventure, embarking on early groundbreaking kayak expeditions, and both also collect kayaking related stories among other subjects. Caffyn has written several books. But it was seeing a photo of Kevin’s bookshelves that made me question my hoarding. Sure, I refer to them all the time in research for writing. Is that why I surround myself with books in my tiny office?

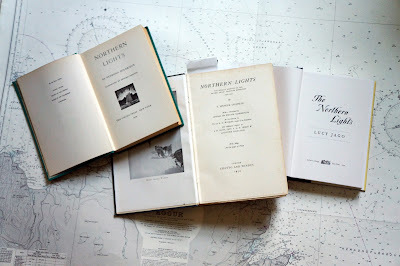

To ponder this question, I pulled a book from the shelf. The explorer Gino Watkins having recently cropped up in conversation, the book I chose was “Northern lights”. I knew where it was located, but if I had asked someone else to find it, they might have pulled any one of three books from the shelves, each with a similar title.

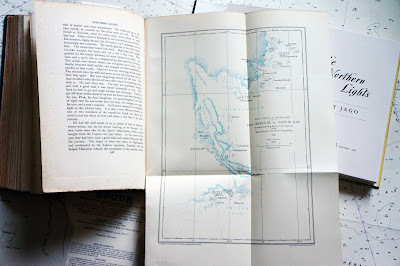

Three books with similar titles

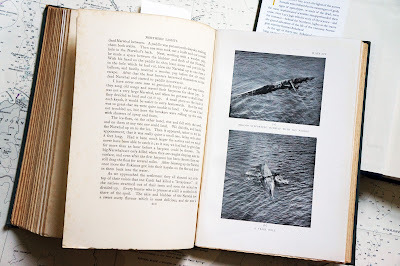

Three books with similar titles“Northern Lights”, published in 1932, recounts the British Arctic air route expedition from 1930 to 1931, Written by Spencer Chapman, it is a revealing book about British Arctic exploration in Greenland, illustrated with black and white photographs. It offers a fascinating insight into their use of small, lightweight, Moth biplanes, fitted as needed with floats or skis, which helped with their mapping. It was in a Gypsy Moththat my father later learned to fly.

Northern Lights: about Greenland

Northern Lights: about Greenland

Chapter XII about The Art of Kayaking

Chapter XII about The Art of KayakingDuring their stay in Greenland, Gino Watkins' team learned from the Inuit how to fish from the ice, hunt from kayaks, and handle sled dogs. As a kayaker, I was delighted to find a whole illustrated chapter titled “The Art of Kayaking”, which title, coincidentally, I chose as the title for my recent book on kayaking technique. Chapman’s chapter begins with the focus on hunting seals.

The Greenland expedition used Moth aircraft for aerial surveys

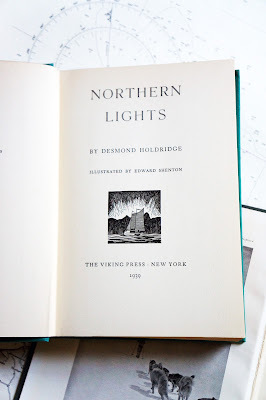

The Greenland expedition used Moth aircraft for aerial surveysThe second book, also “Northern Lights”, was written by Desmond Holdridge and published in 1939. It narrates the story of a 1925 sailing trip to northernmost Labrador. What inspired Holdridge to write about his adventure thirteen years later was the book he had just read. That was “Northernmost Labrador, mapped from the air” by Alexander Forbes, about his exploration and mapping from the air around the entrance to Hudson Strait, a book also on my shelf not gathering dust.

Northern Lights, about Labrador

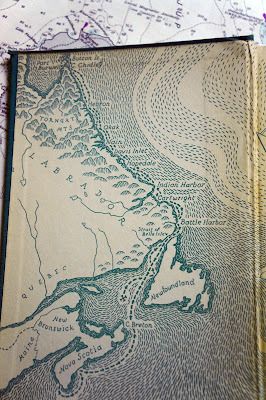

Northern Lights, about Labrador Inside cover maps Labrador sailing route

Inside cover maps Labrador sailing routeIn 1925 Holdridge, with two companions, sailed a small schooner from Nova Scotia to Killiniq Island at the northernmost tip of Labrador, (now part of Nunavut) and most of the way back, before sinking. His account describes many of the Inuit settlements that at that time populated Labrador, describing the people and the nature of the coast. The story, wonderfully descriptive and easy to read, is a treasure trove of information about Labrador, a precious resource to me. I describe my own, much later adventures to the northern tip of Labrador, by kayak in the book: On Polar Tides

Northern Lights over Labrador from the book On Polar Tides

Northern Lights over Labrador from the book On Polar TidesOne of the wonders of traveling in that part of Labrador is the nightly spectacle of the aurora borealis; the northern lights, after which these books were named. Vast dancing curtains of green and red lights play across the backdrop of starry skies. Having seen the spectacle, who would not yearn to learn more? So, on target, the third book, titled "The Northern Lights” was written by Lucy Jago and published in 2001.

The Northern Lights, about the Norwegian scientist who unlocked the mystery of the auroras.

The Northern Lights, about the Norwegian scientist who unlocked the mystery of the auroras.It is the story of the man who unlocked the secrets of the Aurora borealis. Jago’s research revealed the fascinating life of Norwegian scientist, and inventor, Kristian Birkeland who lived from 1867 to 1917. He successfully predicted that plasma was present everywhere in space, and he was the first to explain the nature and behavior of the solar wind. His theory of the cause of the auroras was proven to be correct in 1967 after a probe was sent into space. Of course, much more has been learned about space and the universe since 1917. Brian Greene’s books, also on my shelf, offer more recent perspectives. But his subject matter leads me into other wormholes.

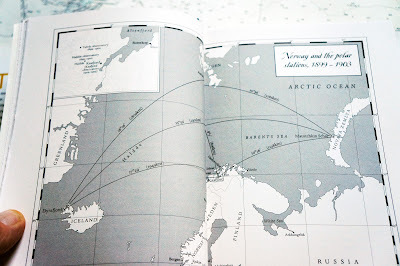

Birkeland set up arctic stations to study the northern lights

Birkeland set up arctic stations to study the northern lightsEach of these three “Northern Lights” volumes is precious to me, but collectively they are even more so for the ways they knit themselves together, while also pointing me off in new directions. The questions they inspired led me down myriad paths into other books that now grace my shelves. All are interconnected by that invisible web. I need only open one book to recall the links to many of the others.

I owe so much to books, I offer my thanks to those who take the time to write them.

September 17, 2022

One Big Asteroid affected Denmark

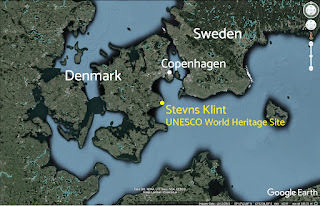

Stevns Klint, in Denmark:

When my friend Mette Carr invited me to join a Køge Kajak Klub kayaking tour along Stevns Klint, I leapt at the chance. These club members know their spectacular white cliffs well, so as we paddled, I was treated to a host of details about this UNESCO World Heritage site.

Stevns Klint, Denmark

Stevns Klint, DenmarkThe Greenland-paddle maker Erik Vangsgaard, and his wife, also Mette, pointed out rickety ladders dangling from the cliffs here and there. These were structures, built by landowners above, to access the hidden cobble beaches at the base of the cliffs. I wonder how often these ladders fail. Each appeared to be a hodgepodge of steps and sections of ladder roped together, spidering down the face.

Rickety steps and ladders dangle from the cliff

Rickety steps and ladders dangle from the cliff"Mette grew up here." Erik pointed up the cliff. "Her father built a staircase down the cliff, and when she was little she used to have a hut on the beach, where she kept chickens and rabbits. There was nowhere for them to escape to, so they could run free on the beach."

Erik in his paddle-making workshop

Erik in his paddle-making workshop

Stevns Klint has been recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2014. These chalk and limestone cliffs to the south of Copenhagen Denmark, mark the place where Luis and Walter Alvarez, father and son, analyzing the dark fish clay layer above the Cretaceous chalk, found the inches-thin thin layer enriched with iridium.

Geologically, the fish clay layer represents the end of the Cretaceous, the demise of the dinosaurs and the start of the Tertiary (Paleogene) at one of the five major known extinction events in the history of life on Earth. Iridium is associated with meteorite impact. Alvarez argued that this layer represented the deposited remains of the creatures killed when an asteroid hit Earth at what is now Chicxulub, on the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico.

Stevns Klint: located south of Copenhagen, Denmark

Stevns Klint: located south of Copenhagen, DenmarkThe fish clay layer traces a narrow line across the cliff, sandwiched between the Cretaceous chalk below, and the Tertiary limestone above. The chalk below the fish clay, and the limestone immediately overlying it, erodes more readily than more recent limestone, which overhang like a shelf.

Hard Tertiary limestone juts out like a shelf

Hard Tertiary limestone juts out like a shelf  A thin wavy orange line here is the fish clay

A thin wavy orange line here is the fish clayThe hard overlying limestone shows evidence of earlier quarrying. At one time, workmen cut rectangular blocks from the cliff. Lowered down and transported by small boats, many of these blocks were used for building in Copenhagen.

Højerup church was built from local limestone in 1200.

Højerup church was built from local limestone in 1200.Built from this local limestone in about the year 1200, the Højerup church was not always this close to the cliff. Over the centuries, the sea eroded the cliff back first to the graveyard and eventually to the church until, in 1928, the chancel collapsed and fell with the cliff edge. The rest of the church still stands, now bulwarked to delay further loss, offering a sweeping view of the bay below. Meanwhile, a new church, completed in 1913 to replace it, stands well back from the edge.

Højerup church perches on the edge above the bay.

Højerup church perches on the edge above the bay.  Face carved into limestone at Højerup church

Face carved into limestone at Højerup church There are shallow natural caves beneath the cliff, which echo with the hollow sounds of waves tumbling flints. But there are also man-made holes that penetrate the cliff, albeit gated from access. These offer the only visible evidence, from the seaward, of the fortress that hides within.

Entrance to natural sea cave

Entrance to natural sea cave

White eroded chalk at rear of cave above flint beach

White eroded chalk at rear of cave above flint beach Cliff entrance to underground fortress

Cliff entrance to underground fortressAlmost a mile of tunnels run through the cliff, 60 feet beneath the surface, forming the once top-secret fortress. Built in 1953 during the Cold War, the fortress was designed to withstand a nuclear attack. It remained operational until the year 2000. Now it is open to visitors as a museum with guided tours showing former underground living quarters, command centers, and military equipment.

Asteroids do still hit earth occasionally. Will Earth’s next mass extinction be due to such a collision? The asteroid that caused the K-T extinction event, (K for Cretaceous and T for Tertiary), responsible for the fish clay layers, was estimated to be about 12Km across. NASA keeps track of several hundred of more than 2,000 asteroids it identifies as potentially hazardous. What will happen when they spot one on a collision course with earth? Rather than waiting, hoping for the best, in July NASA launched the DART mission. A half-ton spacecraft aims to meet the 500 feet wide moon of the asteroid Didymos as it passes seven million miles from earth.

Taking a break beneath the cliff. Fish clay is at shoulder height.

Taking a break beneath the cliff. Fish clay is at shoulder height.If all goes as planned, the spacecraft will eject a camera to document what happens when a half-ton spacecraft slams into an asteroid at 14,700 miles per hour. The collision should occur in October 2022, and the result should give scientists the first hint of how effective the technique might be in deflecting an asteroid from a path toward earth.

If you enjoyed my post, you may appreciate my book: Encounters from a Kayak.

(Thanks to Køge kayak club for such a fun trip, and especially Erik Agertoft for loaning me his Whisky16 kayak.)

August 22, 2022

The Bridge: A twenty-four-hour snapshot from Denmark

Denmark's Great Belt Bridge from Sjaelland to Fyn.

Denmark's Great Belt Bridge from Sjaelland to Fyn. The water became so quiet we could hear every breath of the harbor porpoises. We were guests of our friends Mark and Jane, in kayaks courtesy of Korsør rowing and kayaking club. As the sun slipped slowly down, the water reflected like a sheet of silver.

The water became so quiet we could hear every breath of the harbor porpoises. We were guests of our friends Mark and Jane, in kayaks courtesy of Korsør rowing and kayaking club. As the sun slipped slowly down, the water reflected like a sheet of silver.

Silvery reflections of evening

Silvery reflections of eveningNext morning Mark drove us across the 18-kilometer-long Great Belt Bridge to Nyborg on the island of Fyn (Funen), gateway to the west of Denmark. Yellow painted bicycles propped around the town reminded me that the second leg of the 2022 Tour de France cycling race finished here a month earlier. This, one of three stages of this year’s race to be held in Denmark, was an early stage of the Tour won this year by a Dane: Jonas Vingegaard.

Vendor tents beside cobbled road to Nyborg castle

Vendor tents beside cobbled road to Nyborg castleIf the town had been disrupted by the cycling event, something was up today too. Despite the heat, men, and women in costumes from the Middle Ages strolled the streets past ancient timber framed houses, past lines of tents with red-striped canvas standing ready for street vendors. Up the hill stood the newly renovated tall brick Nyborg Castle founded in the 1170’s. There was an air of something about to happen, like thunder in the forecast, so we asked a woman in costume. She seemed eager to tell us.

Passing Nyborg museum: a farm built in 1601

Passing Nyborg museum: a farm built in 1601The preparations were for the coming weekend of medieval reenactments, she said, with archery contests and jousting with lances on horseback. There would be a grand battle on the knights’ tournament site, along with foods prepared as they had been back then, music, and costumes from the past. It will be an exciting weekend ahead, she promised, but we were a little early. And the day was stiflingly hot. Too hot for fighting medieval style, and much better suited to modern-day ice-cream. We made our way, limp as lettuce, toward the harbor.

Getting ready for a beer bar

Getting ready for a beer barAt the waterfront, a big canvas teepee hung, still in the process of setup with one side drooping toward the makings of a beer bar. No, they were not ready to serve beer yet. By the water, a man in Viking costume was casually tying up the replica of a Viking dragon ship beside a pontoon. We joined the small crowd hurrying to look closer look at the new arrival. The ship was the replica of a death ship, the original found buried some 20 kilometers from here at Ladby. This, the only Viking ship burial discovered so far in Denmark, had been buried with the body of a local king with his weapons and other possessions, including horses and dogs, around 925AD.

Viking dragon ship visits Nyborg

Viking dragon ship visits NyborgThe ship, at 25.5 meters long, (84 feet) with a maximum beam of 2.9 meters (9.5 feet) and a draft of 0.5 meters, was considered a medium sized, narrow, fast longship. It was a warship that could be powered by a sail of an estimated 60 square meters (think more than 30 x 20 feet) plus by 32 men rowing, sixteen along each side. I saw no sign of such a crew today: just one man and one woman, both dressed in period costume. Did they need crew? But they had only just arrived.

Woman in Medieval costume guards Viking ship

Woman in Medieval costume guards Viking shipThe water looked calm and inviting, but I am not a fan of swimming. I prefer kayaking. As good fortune would have it, a Kayakomat stood near the beer tent. I had seen several of these rental booths in the last three weeks in Denmark and was curious to discover how they worked. Considering my association with Point65, I should at least try one. There was a website address on the banner: easier for me than the Danish instructions on the board.

Kayakomat at Nyborg harbor

Kayakomat at Nyborg harborOn-line it proved ridiculously easy to select the country: Denmark, and the location: Nyborg. There it was on the map: Nyborg. Up popped up suggestions of where to paddle, with local tips and information. Choose a kayak solo, or tandem? Or SUP? Selecting from the craft available, and checking date and time, it took just moments to fill in the required details and pay by credit card. Now to see if it all worked. Numbered berths held the kayaks locked on the rack. A code by text freed the lock and we slid each kayak out. We found the PFD, spray deck, paddle… and bailer and sponge stowed inside.

A texted code unlocks the kayak

A texted code unlocks the kayak A quick glance at the laminated map on the rack helped orient us before we carried to the water to launch. Ha! Freedom, sweet freedom! There is nothing–absolutely nothing–half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats. (Kenneth Grahame: Wind in the Willows.).

Steering on port side of kayak?

Steering on port side of kayak? Steering should be on starboard side!

Steering should be on starboard side!Afterwards, sponging out, stowing the gear, and locking the kayaks in the rack to verify their return was easy, in fact far easier than if we had brought our own kayaks. And after our exercise, surely, a beer at the tent would be perfect.

The beer tent not ready to serve yet.

The beer tent not ready to serve yet.The teepee bar’s not ready yet? NO! NO! Cried Mark! Oh well, back to Jane’s. We’ll have a cold beverage in her garden.

April 11, 2022

Baffin Island Adventure

In 1981 I had a plan!

My Vyneck sea kayak ready to leave.

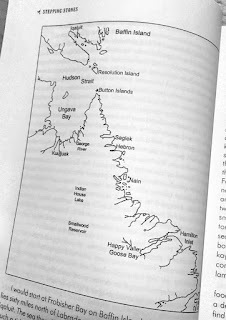

My Vyneck sea kayak ready to leave.I would airfreight my kayak to Iqaluit on Baffin Island, Arctic Canada, and follow some weeks later. Launching my kayak into Frobisher Bay, I would head south to Resolution Island. From there I would cross Hudson Strait to northern Labrador and continue south as far as Labrador’s northernmost village Nain. From there I could catch a coastal steamer south to Goose Bay, to a flight home.

The best laid plans of mice and men often go awry. Robert Burns, the Scottish poet wrote something like that in his poem To a Mouse. So, am I a man or a mouse? Either way, I was about to learn how plans can unravel.

The first hitch was a bomb scare at London airport. We passengers were directed to a different plane, but my checked baggage must have remained on the ground. Arriving in New York with only my carry-on bag, I filed the necessary paperwork for the missing bags to be forwarded. Since filing involved customs, as well as two different airlines, I missed my connecting flight. Did I mention that it was August, and I was in New York, wearing my arctic clothing to lighten my luggage?

With no seat available standby on any flights, I slept at the airport, to be awoken by a commotion. The news: 13,000 air traffic controllers had just gone on strike. It became clear there would be no flights leaving. I cashed in my ticket and hitched a ride to Montreal. A day later I flew to Iqaluit.

My sea kayak, air-freighted some weeks earlier, had not yet arrived. As the days trickled by with no sign of either kayak or gear, my plans seemed doomed.

Streets of Iqaluit, Baffin island, 1981.

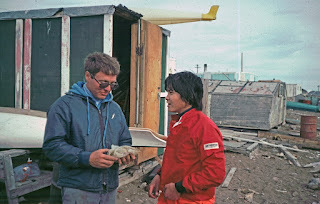

Streets of Iqaluit, Baffin island, 1981.But when the best laid plans of mice and men go awry, we should not be afraid to give alternatives a try. A local man, Peter Baril, rescued me and found me somewhere to stay. A kayaker himself, originally from Ontario, he asked if I ever paddled whitewater. He had always wanted to paddle the Grinnell River from its source, Grinnell Lake, some sixty miles away in the barrens. The river enters Frobisher Bay at Iqaluit. With no news of my baggage, I leapt at the chance to paddle with him.

Peter, left before the Grinnell trip

Peter, left before the Grinnell tripPeter’s friend, a Danish pilot, agreed to fly Peter’s plastic whitewater kayaks to the lake. He decided to see how the plane handled with kayaks first, flying alone with two kayaks strapped to the fuselage.

Iqaluit, we tie the kayaks to the fuselage

Iqaluit, we tie the kayaks to the fuselage

Returning from the rough landing place he had marked out near the lake, he next ferried passengers, before fetching the remaining kayaks.

Airplane landing with kayaks near Grinnell Lake

Airplane landing with kayaks near Grinnell LakeThis plan, not of my making, had worked perfectly. Now all we had to do was skirt the edge of the lake until we found the river. By nightfall we had set our first camp where the lake ran into the river.

Two long fun days on the river carried us back to Iqaluit. There, first my kayak, and then my gear turned up. I was free to leave, but I had mixed feelings. I liked the wonderful people of Iqaluit and felt sad to leave. I also felt trepidation. I would be leaving two weeks later than planned. I had already seen the rapid change in daylight hours. I would soon experience how changeable the weather became at the end of summer. Peter’s planned river descent had gone without a hitch. Little did I know that my own plans would continue to unravel.

On the nineteenth of August I loaded my kayak and said goodbye to my friends.

Nigel Foster leaving Iqaluit

Nigel Foster leaving Iqaluit Riding the outgoing tide along Frobisher Bay, I felt lonely. I focused each new target, crossing the bay to the steep mountainous western side, detouring to see icebergs, running the rapids between the islands. But loneliness and uncertainty eases after setting the tent, cooking, and getting a good night’s sleep. Waking to a stunning scene of cliffs and mountains, I soon became at ease with myself.

Camping,Frobisher Bay, Baffin Island

Camping,Frobisher Bay, Baffin IslandIt would take me a few days to reach the end of Frobisher Bay, where I would leave the Baffin shore for the Lower Savage Islands, and resolution Island. For those few days I could settle into a paddling routine, puzzle how to find good landing spots when the forty-foot tides reached their low point and begin to savor my solitude.

Eroding iceberg, Frobisher Bay

Eroding iceberg, Frobisher BayIn the back of my mind, I held two alternative scenarios. I could circle Resolution Island and return to Iqaluit. That would make a shorter, but very interesting trip. On the other hand, I could continue with my original plan, despite the late start, and head south across the Hudson Strait, some forty miles to northern Labrador. There I would begin the coastal journey south toward Nain.

Map of Stepping Stones route

Map of Stepping Stones route

Which alternative did I choose? Would my plan finally come together, or would it continue to unravel?

Recently I sat down to a conversation with John Chase. John produces a podcast series, interviewing kayakers from around the world. He asked me about my early paddling experiences and was especially eager to hear about this trip. You can hear our conversation at www.paddlingtheblue.com.

October 1, 2021

Reflections on canal travel: Kayak across France.

Reflections fascinate me. They invert my world and offer me an alternative view. There is an above-surface world and another below: reflections appear as the latter. Across a motionless mirror, my gliding kayak creates a wake that visually buckles the virtual clouds.

Plane trees reflected in Canal du Midi at sunset

Plane trees reflected in Canal du Midi at sunsetWhen water moves, it animates the sleeping reflections, constantly scattering and reassembling the view.

Ripples make reflections jiggle.

Ripples make reflections jiggle.If a city street shows me reality, then a canal offers me augmented reality. I catch the movement of a cloud, or a hawk, whether I look down or look up.

If a city street is reality, a canal offers augmented reality

If a city street is reality, a canal offers augmented reality There’s a reason we speak of times of contemplation as reflection. Reflections inspire contemplation, just as they offer a way to discover abstract art, both in still-life and as motion picture. When we stand before an abstract painting our eyes interpret what we see, discovering familiar shapes and returning to find they remain. But on the water, a breath of wind is sufficient to rearrange the patterns. The image constantly pulls back toward what it was, but so long as the effect of the wind lasts, it cannot reassemble. As the motion settles, the dancing patterns never repeat in the same way twice. I am not surprised when I find the animated reflection more interesting to watch than the view it inverts.

Under rainfall, reflections shatter: the water-mirror becomes a maelstrom of intersecting, concentric-ring, ripples. As the surface mists with activity, the reflection of the falling raindrops becomes obscured by the frenzied bounce and jiggle motion. The reflections of larger, more distant, objects now appear glazed as if beneath a grease-smeared lens.

Reflections add depth to the view.

Reflections add depth to the view.

What a treasure, and such a pleasure, to float so close to the surface, so close to the visual dance.