David Gessner's Blog

January 19, 2023

Mark Spitzer

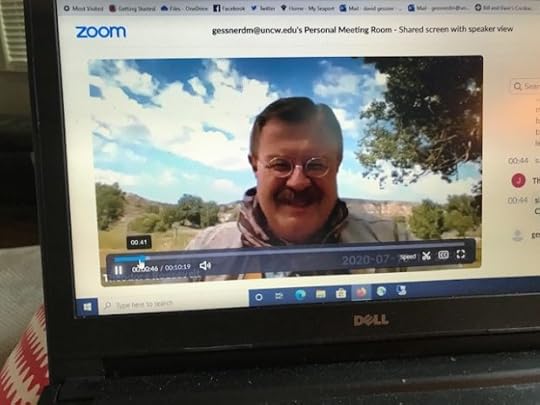

Mark is gone and the world is less wild, less joyous, less creative, less fun.The Mark Spitzer I met in 1991 was a whirlwind of creative energy, of wildness and wackiness, a guy who like his hero Mr. Kerouac, was if not always on the road then always on the move. In his excitement he couldn’t wait to scribble down the fervid thoughts in his head, and sometimes that meant whipping out his trusty orange felt pen and writing sentences right on his pants, sometimes right on his arms. He was the first person I met who was as obsessed with making books as I was, but he was braver than I. Until I met Mark I had been a scared perfectionist, working forever on a novel and not letting anyone, and I mean anyone, see it. Mark was the opposite. He not only blasted out inspired stories and poems and essays, he then turned around and sent them out into the world with the same near-manic energy. With that trusty orange felt pen he mailed his stuff everywhere, from the New Yorker to the Lunar Dog-Fang Journal. He was not afraid and he was awarded with publication—an idea that seemed miraculous to me back then, that someone might actually read your work!His energy was contagious. Like the nouveau beat he was, he drove back and forth across the country in a van called the Unit, catching trash fish and later monster fish, then bunked up for a while in Shakespeare & Company in Paris, where he translated Genet and had doomed love affairs (his specialty until he at last found his great love), creating a fullness to life that combated the existential emptiness that always lurked. “You’re the guy who writes books,” he said to me when we met, though he already was that. His words had a Wizard of Oz effect on me, making me believe. We took many bong hits and drank many beers and went to Ed Dorn’s class to hear him monologue about the High West. Mark moved up to what he called The Mountain Palace in the foothills above Boulder with his Mountain Gals Nina, Melinda, and Beth, where he would make them pancakes and reach things on the upper shelves they couldn’t reach. We all became characters in his books. Nina was Sweet Nina, I was Gruff Dave. He wasn’t crazy about the idea of Gruff and Sweet intermingling, and he would sometimes growl (an actual growl) at me when I got too close to my future wife. He was right to be wary. During one of his many road trips, I moved into the Mountain Palace and turned his tiny bedroom into my office. When he came back he made camp in the cold basement where he tied a line to the light switch and turned it on and off with his fishing pole.He wrote and he wrote and he wrote. It wasn’t just for the finished products (though there was plenty of finished product). It was a way of being. As he made books, he wove a net above oblivion. That was why the recent text that Nina posted last night is so heartbreaking. It reads in part: “It’s strange to suddenly not be planning the details of a book in my head or even on the computer or paper for the first time in my life.”“I can’t imagine it,” I said when we spoke a few days ago. “I can’t imagine it either,” he said back.Mark belied the old idea of the asshole artist. He was obsessed but he was sweet. A wild man but a good man. When I saw him in October he was proud that he had finally gotten his hair just wildly right (see first comment below). Lea says that as late as last Saturday he was working, which doesn’t surprise me. Last week we were brainstorming about a final podcast and he was trying to set up a series of what he called deathbed readings.Monster Fishing comes out in June at the same time my book does and I plan on reading from both books. Mark, being Mark, has two or three more books coming out after that. We both thoughtMonster Fishing was a culmination and capstone of his career. The sentences are alive, spilling over with energy, electricity, occasional ecstasy, and always, raw fun. If you read it for the fishing alone you will be inspired, as well as impressed by the description of the internal ethical wrestling match that is the work of a true essayist. But the art of monster fishing is also a metaphor for a certain kind of life, Mark’s sort of life, a vital and elemental life close to the currents of nature, a life beyond the merely human, a life that is no mere trudge from birth to death, but an embrace of the wild world and all it offers.I hate to end something heartfelt with an advertisement. But if you want to honor Mark, consider pre-ordering the book. Let’s make it a fucking bestseller. He would like that. Here’s a link:https://www.amazon.com/Monste…/dp/1948814773/ref=sr_1_1…

Mark is gone and the world is less wild, less joyous, less creative, less fun.The Mark Spitzer I met in 1991 was a whirlwind of creative energy, of wildness and wackiness, a guy who like his hero Mr. Kerouac, was if not always on the road then always on the move. In his excitement he couldn’t wait to scribble down the fervid thoughts in his head, and sometimes that meant whipping out his trusty orange felt pen and writing sentences right on his pants, sometimes right on his arms. He was the first person I met who was as obsessed with making books as I was, but he was braver than I. Until I met Mark I had been a scared perfectionist, working forever on a novel and not letting anyone, and I mean anyone, see it. Mark was the opposite. He not only blasted out inspired stories and poems and essays, he then turned around and sent them out into the world with the same near-manic energy. With that trusty orange felt pen he mailed his stuff everywhere, from the New Yorker to the Lunar Dog-Fang Journal. He was not afraid and he was awarded with publication—an idea that seemed miraculous to me back then, that someone might actually read your work!His energy was contagious. Like the nouveau beat he was, he drove back and forth across the country in a van called the Unit, catching trash fish and later monster fish, then bunked up for a while in Shakespeare & Company in Paris, where he translated Genet and had doomed love affairs (his specialty until he at last found his great love), creating a fullness to life that combated the existential emptiness that always lurked. “You’re the guy who writes books,” he said to me when we met, though he already was that. His words had a Wizard of Oz effect on me, making me believe. We took many bong hits and drank many beers and went to Ed Dorn’s class to hear him monologue about the High West. Mark moved up to what he called The Mountain Palace in the foothills above Boulder with his Mountain Gals Nina, Melinda, and Beth, where he would make them pancakes and reach things on the upper shelves they couldn’t reach. We all became characters in his books. Nina was Sweet Nina, I was Gruff Dave. He wasn’t crazy about the idea of Gruff and Sweet intermingling, and he would sometimes growl (an actual growl) at me when I got too close to my future wife. He was right to be wary. During one of his many road trips, I moved into the Mountain Palace and turned his tiny bedroom into my office. When he came back he made camp in the cold basement where he tied a line to the light switch and turned it on and off with his fishing pole.He wrote and he wrote and he wrote. It wasn’t just for the finished products (though there was plenty of finished product). It was a way of being. As he made books, he wove a net above oblivion. That was why the recent text that Nina posted last night is so heartbreaking. It reads in part: “It’s strange to suddenly not be planning the details of a book in my head or even on the computer or paper for the first time in my life.”“I can’t imagine it,” I said when we spoke a few days ago. “I can’t imagine it either,” he said back.Mark belied the old idea of the asshole artist. He was obsessed but he was sweet. A wild man but a good man. When I saw him in October he was proud that he had finally gotten his hair just wildly right (see first comment below). Lea says that as late as last Saturday he was working, which doesn’t surprise me. Last week we were brainstorming about a final podcast and he was trying to set up a series of what he called deathbed readings.Monster Fishing comes out in June at the same time my book does and I plan on reading from both books. Mark, being Mark, has two or three more books coming out after that. We both thoughtMonster Fishing was a culmination and capstone of his career. The sentences are alive, spilling over with energy, electricity, occasional ecstasy, and always, raw fun. If you read it for the fishing alone you will be inspired, as well as impressed by the description of the internal ethical wrestling match that is the work of a true essayist. But the art of monster fishing is also a metaphor for a certain kind of life, Mark’s sort of life, a vital and elemental life close to the currents of nature, a life beyond the merely human, a life that is no mere trudge from birth to death, but an embrace of the wild world and all it offers.I hate to end something heartfelt with an advertisement. But if you want to honor Mark, consider pre-ordering the book. Let’s make it a fucking bestseller. He would like that. Here’s a link:https://www.amazon.com/Monste…/dp/1948814773/ref=sr_1_1…

December 30, 2022

Writers for the Wild: Five Days in May

Next May the great Craig Childs and I will be in the shadow of the majestic 14,000-foot peaks of the Sangre De Cristo Mountains at the Zapata Ranch. You are invited to join us. We won’t be teaching, I hope, so much as leading an experience. I’ll post the official description below but the idea is to have a morning of generative writing (though we hope to include scientists and environmentalists and other folk as well as writers), hike some trails, watch some birds, dip in some cold water, and have vigorous salon-like discussions about the fate of the world (during cocktail hour).This is the first of what I hope are a series of retreats we are calling Writers for the Wild.Here’s the link: https://ranchlands.com/pages/writers-for-the-wild?fbclid=IwAR2aAPv62GCwVs5dgUdBmMeLAZJMV116VrgyNYa1-H0OmLEVgDtdj1Q2Hqo Here is the official description:The ProgramWe will start each day with a generative writing exercise and discussion. Writers of all stripes are welcome, from beginners to published authors, but also scientists, environmentalists or anyone else concerned with the fate of our threatened world. The idea is to dig deep and begin to work on what is most important to you. This will be less a traditional workshop than a prod to thinking creatively about your own work and life. What do you want to do with yourself during your brief time on planet Earth?“First be a good animal,” said Ralph Waldo Emerson. Exactly, though for us it will be second. Having exercised our minds, it is time for our bodies. Daily activities will include mountain hikes, natural history walks, horseback riding, birdwatching, and, for the brave, Wim Hoff-style cold dips and breathing/mediation sessions.In the evening (cocktail hour) we will hold informal salon-style discussions about a wide-ranging series of issues from writing to climate change to the challenge of being a good animal in a virtual world to whatever the hell else we all feel like talking about. This can include readings from books that we love. A few brave folks may even be willing to read their own writing.Then we will sleep well.

March 9, 2021

December 10, 2020

A Daunting Time: 13 UNCW students on being the Class of December, 2020

A Daunting Time: 13 UNCW students on being the Class of December, 2020

[image error]

Intro by Nina de Gramont

What is it like to graduate into this broken world? What are the prospects for a future in a pandemic? These are the question my students and I have been asking in the Fall semester of 2020.

As a professor of creative writing at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, one of my favorite classes to teach is Senior Seminar, where graduating students complete their theses and write an analysis of the work they’ve done while in our BFA program. We also talk about career opportunities, how to apply to grad school, and how to continue a creative life when there are bills to pay. The class ends with a public reading of the students’ work, to which friends and family from all over the state – sometimes from all over the country – travel.

In usual times, much of the class is taken up with my exhortations to be brave. In one class a few years ago, I showed base jumping videos to highlight the value and excitement of risk. It’s a time in their life, I tell them, when taking risks is appropriate and necessary.

But these aren’t usual times. Instead of sitting together in a classroom, we’re a collection of tiny heads on Zoom. There’s no public reading to look forward to, or even a graduation ceremony. Taking risks isn’t what it used to be. How do we create excitement about venturing forth into a world that’s ground to a halt?

Covid-19 was an unforeseen event for the students who graduated last May. But our December graduates entered this semester knowing what it would look like. They gritted their teeth and faced it anyway. I asked each of them to write about Senior Year in the Time of Corona Virus. When I read their dispatches I knew this would be the year I didn’t need to tell my students to be brave. They had already told themselves.

Joe Bowling

I have to look at the funny side of graduating college during the COVID-19 pandemic. After all there’s only one other option, and that’s just grim.

I’ve been going to college off and on—definitely more the former than the latter—for the last ten years. I’ve quit many times before for many reasons, but there’s something about this semester that I just don’t want to let go of. I find it hilarious on a cosmic scale that I’ve finally decided to buckle down and get school done just in time for the universe to bring everything to a screeching halt.

With so much instability in the world, it’s nice to have something that I can control. If I take these five classes, show up on time, and do all of the assigned work, I will graduate in December. Whatever that looks like now. Even in dark, divisive political and social times like these, I have the chance to do something that no one in my immediate family did before me. At the same time, it’s a bit like life has handed us lemons and asked us to make lasagna.

This is a huge struggle for me, but I am aware it’s a huge struggle for all of us. I draw upon my military training to get myself through. I have the benefit of perspective. We unite through struggle. We bond together and bear the burden not as individuals, but as a single cohesive unit. We will come through the other side of this stronger than we would if things were still going according to plan. I know this final semester is going to be a roller coaster ride full of ups, downs, and de-railings. Those are just the facts. In the face of them, I’ve made the conscious decision to carry on. To lift up my classmates when they’re down. And, most importantly, to step out of the grim reality of the pandemic and take some time to laugh—even if it’s just to keep from crying.

Jules Miller

It wasn’t meant to be like this, but graduating during COVID is exactly how you think it would be. Uncertainty does not begin to explain the depth of my feelings. I am missing people—people who were supposed to be at my graduation. It’s like making a fancy sandwich and biting into it only to get a mouthful of stale bread that, to top it all off, was secretly stowing mold inside. No meat, no cheese, no vegetables. Just mold and the ghost of what bread used to taste like.

The Zoom calls have backed everyone into a quiet corner of politeness, afraid their voice might break audibly into someone else’s. We cannot overlap anymore. It is not the education I knew; it is not the education anyone expected when they entered this program with hopes of graduating on time.

It is, though, a different kind of normal. Private message chats between peers bring them closer without risk. Are we paying attention in class? No. Our brains are beyond it at this point. We crave connection and touch, and we hope another person will be there—will not be missing. We yearn for the end of this. We long to be unafraid to interrupt again. To overlap. To be heard. And we wait together.

Saifey Maynor

My life didn’t really begin till March. When quarantine started my boyfriend, who was visiting for spring break, got stuck here. We’d talked about cohabitation before and decided we weren’t ready for it, but when we realized that this all was never going to end he moved in. Having his support means not relying on my grandparents as much, which is great, but it also means I don’t really get the feeling of entering a new phase of my life that graduation is supposed to bring. It’s not like my personality is any less based around my grades than it always has been, but having another person sharing my bed has really put everything in perspective. There’s a man in my apartment and y’all want me to care about the world outside? Nope. People drive themselves crazy by caring about real shit right now, and I’m already crazy. I’m not falling for that.

I’m staying in the same apartment come spring, so it’s not like the landscape is changing. The only thing I’m losing is the ceremony, and I was not looking forward to the ceremony. I killed myself to keep my GPA such that I’d graduate with honors, and the stress of knowing I’d hear “cum laude” instead of “(x) cum laude” was making me want to kill myself again. Now, nobody knows my GPA is between a 3.5 and a 3.7 and none of y’all know me, so none of y’all care!

I’m still not “in” the “workforce,” I still don’t use subject lines in emails, I still don’t have an instagram or twitter or whatever young professionals are doing now. But I do have a man in my apartment. And I don’t have to cope with being an undergrad anymore. Think on that.

Kayla Benson

The smell of a fresh funnel cake at the county fair on a cool Autumn day. The feeling of shoulders brushing against one another at a crowded concert on a starry Summer night. The sound of sneakers squeaking on the floor of a polished college gymnasium. The taste of a perfectly cooked steak while catching up with old friends at a busy restaurant. The sight of returning students greeting one another with warm hugs and big smiles. I wish I could have known how much these miniscule moments would mean to me while I was living them.

I’m not going to lie and say I’ve dreamed of graduating college since I was a little girl. The most I’ve thought about graduation becoming a reality is in the Fall of 2020 when I realized what it will actually be like. There won’t be a building full of teary-eyed loved ones and soon-to-be alumni excited for the future. There won’t be big celebrations after a long list of names get called. No one will hug and take pictures as a group, or get to say their last goodbyes face to face. In the world we currently live in, graduation will mean sitting alone while names are announced through a tiny computer speaker. Our diplomas will come in the mail weeks later. The darkness of a screen and the close of a laptop will represent four years of college completed. This is as good as it gets. At least, for now.

Chris Dixon

It feels daunting to be graduating in Winter 2020 but I’m still looking forward to it. I’ve been in college since 2010 and I simply want to move on with my life. I’ve had to deal with red tape, bad teachers, and personal struggles just to get to this point. I’m happy to be finally done with college so I can move on to the next chapter.

I dropped out of college for three years and gave up on ever being where I am now. Graduating felt like a pipe dream and I thought I should move on and get used to staying in my hometown. Eventually I got out of a dark place and got my life together on my own. I have been taking care of myself in spite of my many personal problems. I can’t stress how good it feels to be this close to graduating with everything I’ve gone through to get here. It’s not a dream anymore.

Yes, I know things are bad right now, and there’s not much I can do about it so, I won’t stress myself out over things I can’t control. I’ve seen a lot of bleak, depressing, borderline nihilistic opinions that everything is bad and isn’t going to improve and I don’t find that outlook to be helpful in an already bad situation. I’d rather take what comforts and good news I can and not let the world or news beat me down and put me in a negative state. It doesn’t feel good and it’s difficult to get out of.

Kaila Byram

Contrary to the popular belief, graduating during a pandemic is exciting! What could be better than wearing a blouse with sweatpants for a Zoom meeting? The pandemic is a great way to save money, save time, and get things done. Got fifteen minutes in between Zooms? Wash those dishes that have been sitting in the sink for two weeks. Need to catch up on laundry? You’ve got time, especially without driving that commute. Always wanted to move to Spain but couldn’t because there’s no work opportunities? Great. Well, actually, no. They won’t let Americans in now. Unsightly pimple on your upper lip? No worries! COVID has you covered! Just wear your prettiest mask and no one will know.

In all seriousness, this pandemic hasn’t been easy. I’ve had my ups and downs this year like everyone else but one thing I’m completely terrified of is not being able to get a job and support myself. I have $25,770.34 in student loan debt, a car payment, and other bills that need to be paid. I’m probably going to have to move in with my parents. The world is in a state of flux, just as my life will be when I graduate from college. The world is changing, and there’s nothing anyone can do to stop it. What choice do I have but to roll with the punches and grow with whatever this world is turning into?

Chadstity Copeland

It’s been a daunting time. I’ve been in a slump that heavily affected my mental health and it’s been a struggle to seriously focus on anything. Early on I had a bit of optimism, when I could mull over how things might improve by summer. Things didn’t improve, and as my final semester crawled closer, I decided to ignore the pandemic. Not to become oblivious, but not to let it dampen my mind.

I decided to pour my anxieties into what I loved most: reading, writing and music. I consumed so much K pop, rock, alternative/ nu metal and even American pop albums that it became a pseudo soundtrack for my creative writing. This music fueled me to write more and more about my own fictional worlds. Instead of lingering on the troubles of the real world, I turned toward an outlet that not only improved my mental health, but also made me fall in love with my creative work again. This pandemic made me reflect on how I’m in charge of my creativity, and with graduation on the horizon, it gives me reassurance that I’m in charge of my own destiny too.

Jessika Hicks

Although I don’t know anyone who’s had COVID-19, this virus alters my life every day. Despite the isolation I know I am not alone. This pandemic is leading the future in a new direction.

I haven’t had a normal school year since I transferred to UNC Wilmington. First, hurricane Florence devastated our school. I was forced to stay home in Charlotte for a month. The following year hurricane Dorian hit and the school issued a mandatory evacuation. I was so worried about how long Dorian would be last and how much destruction it would cause.

Dorian was nothing compared to Florence, but then came COVID-19. I spent most of my summer watching TikTok to try and distract myself. The videos made me laugh so hard I cried, but mostly, they inspired me. I saw so many people finding hobbies and passions and starting small businesses. My best friend chose to pursue a Masters degree; quarantine gave her the self-reflection and space to make this decision. I’m realizing the importance of slowing down and not pushing myself too hard. I started drawing again for the first time in years.

Now I’m back on campus, but it’s not the same. The increasing COVID clusters scare me. We’re all doing our best to wear masks and stay safe. I feel like my senior year has been stolen; all my classes are on Zoom and I miss interacting in person. With the current job market I’m scared I won’t find work in the career I want. It makes me anxious to see how COVID-19 shapes my future. I’m focusing on finding what and who makes me happy while trying to remain hopeful.

Will Robertson

I’d love to hear the clink of a glass with my classmates, but how are we supposed to truly cheers to graduation and all of our accomplishments six feet apart or over a virtual meeting? Usually, there are people to blame for the madness in our world, but we don’t have that. I’m forced to accept the reality that this world doesn’t work the way I thought it did—it’s subject to change and about as reliable as toilet paper sitting on the shelf when the virus was starting its engine.

All of us students at UNCW have had to be extremely adaptable these past years, dealing with fallen trees and cancelled classes because Wilmington seems to be a hurricane’s favorite spot. We’ve become accustomed to interruptions, but now are pushed to a limit that no meteorologist could have predicted. It takes time for our city to repair from storms, but it takes even more time for our world to get through a pandemic.

Especially in the Creative Writing program, I feel like we are a community—all trying to be the best writers we can be. The privilege of being on campus with my talented classmates has been, for the most part, taken away. I never would have imagined that my last semester would mean my eyes always fixed on a screen.

What keeps me optimistic is looking at this time in our lives as an international meditation, and hopefully, once everyone is safe again, we can go out into the world refreshed with an uncovered smile—healthy, inspired, and ready to share our minds with the world.

Kalya Greene

Graduating during a pandemic is surreal. The near constant terror from the first month has dulled into a general blanket of misery and fear. School feels ridiculous. Everything in me hangs heavy, but it seems that all anyone wants is normalcy. A smile and a job well done. It’s hard for me to summarize everything in my head when it comes to this topic. I am sad, anxious, afraid, but mostly tired.

I feel as if writing my true feelings will be perceived as negative. I have no “It will get better” or “We’ll get back to normal soon” for anybody. I’m graduating in December, and I don’t know how to feel about it. I don’t think I’ll notice until deep into January when I feel the absence of that unyielding structure that has been omnipresent in my life since grade school. All I have right now is hope that I’ll find a way to exist in this world, while I’m here.

Mel Newcity

I imagined my final semester very differently when I returned to college. At twenty, I had dropped out due to financial complications, and I worked full time in various offices until I could resume my courses part time. For five years, I slowly chipped away at my degree. As my younger classmates graduated, I watched with anticipation barely outmatching my envy. Surely, I thought, my labor would culminate into a celebration of patience, diligence, and perseverance. I imagined a thesis reading surrounded by friends and family, flowing robes, and a final product I could send off for publication.

Graduating during COVID means family and friends can’t travel. I have no desire to pick up my graduation gown. My thesis is as exhausted as I am. I cannot fully express my disappointment with the reality of my final semester during the pandemic. I can only depict today. This morning, I sit on the porch before my next virtual meeting, reflecting on the poets who’ve influenced me over the years. A pair of cardinals perches on a nearby telephone wire. The autumn breeze rolls in just as it did last year and the year before. My cat paws at the sliding door. Each moment brings about its own reason for commemoration. If I pare back my expectations, my final semester isn’t too far off from what I imagined. I may be tired, overwhelmed, and bouncing on the emotional spectrum, but I have my health, my pen, and reason to celebrate.

Sarah George

Being a college student during COVID is, in a word, difficult. I feel a bit as though I’ve been robbed of a truly comprehensive, full final semester here at the university I have grown to love. Not to mention the worry about a graduation ceremony (or the potential lack thereof). When quarantine began last March, I had no idea things would get this bad, and as it dragged on I became more and more depressed and unmotivated. Depression is something I struggle with anyway, so world events exacerbated it. While I was at home, I would just get up to eat and go to work, and the rest of the time I didn’t even feel like leaving my bed. At first I thought I could turn it into a good opportunity to get writing done, but I didn’t write hardly anything at all, which made me feel even more like a failure. I was completely miserable.

Once campus finally opened up this semester, coming back to UNCW helped my mental state considerably. I was able to get out a bit and see my dear friends again. COVID scares on campus were worrisome, but now it seems that we are on the right track and will finish just fine. Getting back to a routine has helped me get back to writing, too. So, really, I’m doing better every day. I can’t wait until this whole mess is just a bad chapter in a history book. I’ll be able to look back on it and be grateful for my close friends who helped me so much during all this. I feel as though graduation itself will be a blur; something considered only long after it’s over.

Kristen Dorsey

Years ago, when my high school friends headed to college, I got on a plane to Parris Island, South Carolina, to USMC boot camp. My four-year military tour had less to do with patriotism (although I am proud to have served) and more to do with 1980s Reagonomics: my family couldn’t afford to put four kids through college.

I don’t regret my service. I traveled overseas, got physically and emotionally strong, and learned skills that resulted in ten exciting years in the Intelligence field within the Department of Defense. The Marine Corps gave me the discipline needed to run my own business after I left the DoD.

In 2017, I took a risk: I moved to Wilmington, and enrolled at UNCW as a full-time student in the Creative Writing Department.

As I approach my later-in-life graduation, I seesaw back and forth between excitement and terror. I let go of everything I used to be at an age where many people find new beginnings—and that’s exciting.

However, like all my classmates, I’m joining a workforce where almost half the adult population is underemployed or unemployed. Add that to 2020 statistics from the National Bureau of Economic Research that found that workers over age forty are only about half as likely to get a job offer as younger workers.

Sometimes I lose my breath, thinking, “What have I done?” But writing, I’ve discovered, gives voice to my life experiences in a deeply satisfying way. There’s no going back, anyway, and while this is an unprecedented ordeal in our history, I’ve been through tougher times.

September 10, 2020

FIRE

As the peak of hurricane season arrives, and seven tropical systems make their way across the Atlantic, I am thinking about big water. But I am also thinking about fire and my friends, and the land I love, in the West . This is an excerpt about western fires from All the Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner and the American West:

After we cleared the plates, Elena volunteered her babysitting services, and Emily and I drove up into the foothills above Fort Collins to see the scars from the recent fires. The fires had just died down, after raging for a month, and would have ended up being the most costly fires in the state’s history were it not for the almost-simultaneous conflagration down in Colorado Springs. It was a summer for the history books with the Front Range ablaze and often blanketed in smoke.

We drove following the river up into the hills, but the river was so dry it seemed no more than a red stain of itself. Soon we were staring up at miles of charred ridgeline. In Soldier Canyon we saw an entire charcoal hillside of blackened trees, the spindly remains looking like black skeletons. Emily told me that the high winds had caused the fire to jump from tree to tree, at one point actually jumping the river. She related the story of an acquaintance who was carefully evacuating, knowing the fire was miles away, when suddenly his house was aflame.

We drove past the Rist Canyon Volunteer Fire Department and to another charred ridge of forest. Dark gnarled hands grasped at the sky. About seventy percent of the homes in the area had burned.

I asked Emily if I could get out of the car and walk up the ridge a bit. The land smelled of ash, the trees blackened. My footfall made a sibilant hiss as I moved through the crisp, ashen landscape. The ridge above looked like a porcupine’s back, the spikes consisting of black trees with only the slightest color from dead yellow foliage.

I knew that as historic and tragic as that summer’s fires were, there was a very good chance they were just a preview. I thought of the way that the fight to tell the truth, and to get westerners to see the facts about their land, ultimately wore Wallace Stegner down. It isn’t hard to see why. Stegner understood the necessity of hope, but in the end the facts painted a less than hopeful picture.

The facts have grown more depressing. Over the last decade the cost of fighting fires has gone from making up 14% to 50% of the Forest Service’s budget, and both firefighters and scientists tell us that we have entered a new era of fire in the American West. These recent fires, called “megafires” by some, are certainly exacerbated by climate change, but they are also aided by historic factors apart from rising temperatures and increased aridity. Primary among these is the long history of fire suppression in the West.

Fire suppression, of course, was supposed to be a good thing. Like the introduction of erosion-aiding tamarisk on the banks of western rivers, it was meant to help with an existing problem. In this case the problem was the “Big Blowout” fires that ravaged the west in 1910 and that gave weight to Bernard DeVoto’s idea that in the West catastrophe might destroy a whole region. Millions of acres were burned and the flames eventually ignited not just forests but the country’s imagination. Fire fighters became national heroes, and fighting fires, all fires, became the driving purpose, the idee fixee, of the Forest Service. But as often happens when we intrude on natural processes, this created a problem. It turned out that by suppressing fires, we stamped out even the smaller fires that had beneficially rid forests of excess fuel in the form of deadfall, scrub growth, and other organic debris. It is as if a giant had come along and arranged things perfectly in the fireplace of our forests, with plenty of kindling and paper below the big logs.

Finally, the trees have changed in another way. The changing climate is effectively turning the West into a powder keg by reducing snowpacks and lifting temperatures, with these extreme temperatures effectively sucking the moisture out of trunks and branches. This means that the trees are perfectly built for ignition, the wood so dry that they are always a spark away from burning. The result has been that in recent years we have had our own Big Blowouts, and have witnessed the largest and hottest fires that have ever been recorded in the West.

Over the last few decades the Forest Service and other organizations has begun to understand the combination of factors that aid these fires, and have tried to reduce the fuels that feed them by clearing the forests of excessive deadfall. Policies of fire suppression have also loosened, though in the current climate of understandable fear, there have been renewed cries for the old ways of stamping out every spark. Of course in places like this hillside the houses themselves help provide the fuel, going up like torches.

When I visited with him in Kentucky Wendell Berry urged me to consider land use as I explored the West. This meant understanding which places are fit for farming, for homes, for mining , for recreation. To begin, we must question some basic assumptions. In this summer of fires, one of those questions is simple enough: is it wise to build wooden homes, or any homes, near national forests or in the fire-prone foothills above mountain towns? Then there is a larger question of land-use, one unique, in our country at least, to the West. When you build a house in the western wilderness you are not building a cabin in the Berkshires. You are laying claim to land that is at once vulnerable to human incursion and often inherently risky to settle.

Homeowners will soon be re-building in these burnt hills, but, while they don’t want to hear it, there is little question that the land would be better off left alone. When people do build near forest land, they wisely fear the slightest sign of fire. Which means that they have little tolerance for even small blazes, those beneficial blazes that have been a historic part of the cycles of western forests. And more people always means one more thing: a greater chance of sparking a fire.

Throughout the West, the human population will increase, that is a given. But even as it does we had better keep in mind the particulars of the place. There are landscapes in the West that are naturally ornery, that ask, in all but words, to be left alone. More specifically, what the land here asks for is a clustered population with large buffers where there are no humans at all. To our credit we have done just that, as a people, in establishing parks and national monuments and forests and other public lands. But as more of us crowd in, and put more demands on this land and its water, and as more people attempt to pry away protected land and “put it to use,” we had better remind ourselves of why large sections must remain free of human intrusion.

If parts of these western lands are really as vulnerable and difficult to inhabit as Stegner and others have suggested, as open to disaster, then perhaps to leave them alone is simply practical. We don’t put land aside only because it makes for a pretty park. We put it aside because it makes sense. It is how it should be. Much of this land is properly wild.

* **

From a passage earlier the book from my visit to Boulder:

We reached the Flagstaff summit and took the bikes off the back of my car. Though it was the summit of that particular mountain, there was plenty of up left. We pedaled the steep section above the summit that we used to call “Old Bill.” Rob seemed to get some slight sadistic pleasure in seeing me gasping for air like a landed fish. I made it to the top, just barely, and only after Chris pedaled up and shouted encouragement, finally pushing my bike from behind during the steepest section.

After we reached the top we rode down the mountain’s other side so we could get a good look at the area that had burned. A charred ridgeline greeted us. Chris told me that all June Boulderites had stared up at the smoke, praying that winds wouldn’t blow toward town.

“It’s so dry that the mountain houses would be like kindling,” Rob said.

Of course what went unsaid is that Boulder had been lucky, at least compared to other front range towns. Less than two weeks before, the Waldo Canyon fire in Colorado Springs had leapt over two lines of containment to torch houses in the city proper. It became the most destructive fire in the state’s history, its 350 homes destroyed passing the record of 259, a record just set only days before by the High Park fire in Fort Collins. A decade earlier when Colorado experienced a similar if less destructive fire season, those in the fire-fighting community were skeptical of the role that climate change played in the fires. No longer. With record temperatures and light snowpack the fire season now regularly starts almost two months earlier than it did just a decade ago. A century of fire suppression has led to forests unpurged by smaller fires, and therefore packed with deadfall and groundcover that helps light up the drought-dried wood like torches. And with more people building houses in fire prone areas there is plenty of added fuel. I couldn’t help but be reminded of the trophy homes that line the beaches in the Outer Banks in coastal North Carolina, houses that have been set up like bowling pins to be knocked down by the next hurricane. In both places it is most often the wealthy who build homes that are endangered, and frequently these are second homes. I thought of how, back in Carolina, summer is always an anxious time, with people awaiting the beginning of hurricane season. Here they awaited fire. There was also another similarity. The same fervent belief in rebuilding infects both the homeowners who have seen their homes burned down and those who have seen theirs slammed by the sea.

“Re-build!” they all shout. But there are other voices, too, and more than there used to be, voices that suggest that perhaps it would be better not to re-build. You could argue that, with the embers barely cooled and whole towns engulfed in tragedy, this wasn’t the right moment to question the wisdom of re-building in the dry Colorado hills. Or maybe it was the exact right moment. In the fervor after a disaster there is always talk first of loss, then of hope and re-building. What there is not a lot of is cold-eyed clarity.

Which is where DeVoto and Stegner help. In this burning summer, these two dead writers couldn’t be more alive. In a time of drought and fires it is hard not to return to their central contention: that this land that we are treating like the land of any other region is in fact quite different, a near desert, and that its life depends on that not-always-reliable snowpack. Much more reliable are the cycles of drought, which have been a part of the West forever. As it happens we are now in the midst of one of those cycles. It would be wise to acknowledge this and deal accordingly.

What would that mean? For starters, acknowledging that there is a reason that the West has always been relatively unpeopled. Large stretches of it are simply not fit for human habitation. The booster says, “Well, let’s make them fit!” The Stegnerian realist says, “Well, maybe we shouldn’t live there.” Don’t move to a place where your houses are likely to serve as kindling. There are some places that are better left alone.

But what’s the point of saying this now, when the houses are already built and when those burned will surely be re-built, the genie already out of the bottle? Because we are at this moment seeing many of the things that Stegner and DeVoto warned about coming home to roost. And because even if warnings are not heeded, they still must be given.

Stegner understood well the necessity of hope, but in the end knew that cold-eyed clarity was more important. Today cold-eyed clarity tells us this: the world is warming and some of the places that the world is least ready to adapt to that warming are places that are already, as Stegner called them, “subhumid and arid lands.” In a place already on the edge, a slight tip puts you over. In a place where drought is already commonplace, more heat and less rain are killers.

The majority of climatologists believe that, along with low-lying coastal areas, it will be the water-stressed areas of the world that will be most affected by climate change. At first this sounds simple to the point of being a tautology. It isn’t. They are not merely saying that the dry places will be hardest hit. They are saying that the driest places, like the American Southwest, will change the most compared to their baseline. And how will they change? The predictions are consistent. Drought is by definition an anomalous word, but what we now call drought will become the norm. And with that as a new baseline, the droughts will be of a sort the region hasn’t seen since the Middle Ages, when so-called megadroughts drove the Puebloan people from the region.

For Wallace Stegner, real knowledge of a place, and science, trumped myth. And what science is now telling us is straightforward: that a place that historically had little water will have less.

August 31, 2020

August 9, 2020

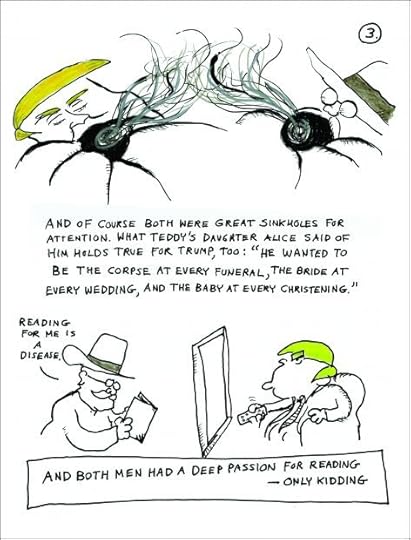

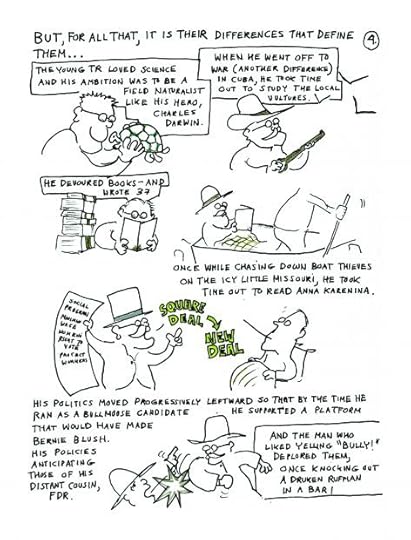

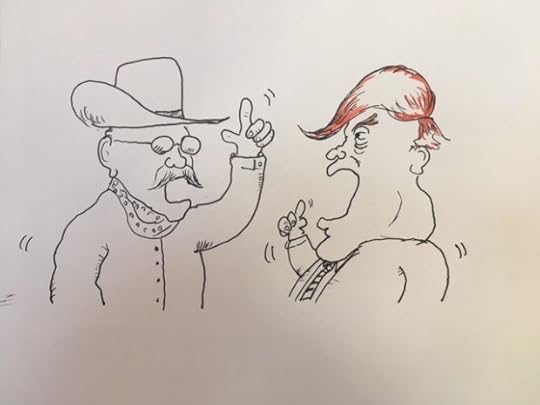

Trump vs. TR: The Big Fight

Leave it as it is!

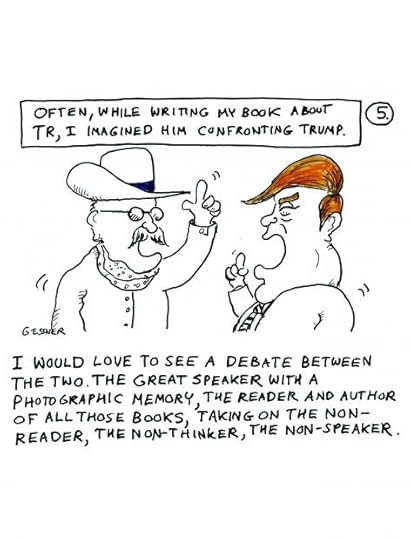

I imagined our twenty-sixth president saying those words, sharply and emphatically and confidently, to our forty-fifth. I wanted to see the fight that would ensue if 45 tried to take away the land that 26 had saved.

Though taller and certainly heavier than TR, Mr. Trump would have his hands full with a president who boxed and studied jujitsu while in the White House.

But if witnessing a physical confrontation might be fun, a mental and verbal battle would be even better. The great thinker and speaker, the author of all those books, whose mind ranges throughout history and whose photographic memory can conjure up full pages of the books he reads, debating the non-reader, the non-speaker, the non-thinker. The match would be competitive only in terms of raw belligerence and self-confidence, but unequal in all other ways. Particularly since TR was most eloquent when spurred to outrage and since nothing drove him to outrage like the rising tide of commercialism and crassness that was flooding the America he loved. He hated nothing more than “the wealthy criminal class” and “predatory wealth.”

August 2, 2020

Shack as Metaphor

For a pretty humble building, the shack has done a lot of metaphoric lifting for me over the last few years. Tonight, as the storm approaches, I am thinking about it as a stand-in for all the writing the world doesn’t see. “Four fifths of his productive iceberg was under water,” Wallace Stegner wrote in The Uneasy Chair, his biography of Bernard DeVoto. With Thoreau that might have been closer to nine tenths, maybe more. If we define “under water” as writing unseen by the public and we reason, not unreasonably, that had Thoreau’s reputation not been revived, somewhat miraculously, the journal would have been left unread, maybe we are talking closer to 99/100ths. This is something non-writers don’t understand. The real work is not always the work the public sees. The real work goes on daily, unseen, unappreciated. Which doesn’t make writers special. It makes their profession similar, in this way at least, to every other.

So back to the shack. I’ve spent the last 8 months re-building it, shingling it, fixing it up, making it so that it looks completely unlike its truly shack-like predecessor. “A fancy little house,” Nina calls it. But this fancy house is still at sea level and basically in the marsh. And now another storm has taken aim at us. Hence the shack as writing metaphor. All that work. For what?

Not for naught, I would say. I’ve poured time into it and not a little money (cedar shingles are expensive), but I’ve also gotten a lot out of it. Absorbed hours of work and problem-solving. Good chunks of time when I was worried, not about my own troubles, and not focused inward on my own neuroses, but outward into a project that fills up my hard-to-fill mind. I don’t need to say “Just like writing,” do I? You get it. Well more than half the pleasure of it, whatever the worldly results, is in the doing of the thing. The fact that wind may now come and blow my little house down is incidental. In fact, in the long run, it may be advantageous. That way I can build the shack again. How could I get so lucky?

August 1, 2020

July 9, 2020

Exiles (For Brad Watson)

Gessner

EXILES

In Honor of Wilton Brad Watson 1955-2020

In 2003 I underwent a sea change, though I still live by the same sea. That was when I left my home beach on Cape Cod and moved a thousand miles south to an overdeveloped island off the Carolina coast. It was a hard goodbye, one necessitated by money, work, and health insurance, paralleling a career move my father made, from Massachusetts to North Carolina, at exactly the same age. Though in moments of melodrama I felt I had made myself into an exile, I knew it wasnât all that bad. But there was something in the way of surrender to the move.

This is overly-dramatic, I know, but during those first years I couldnât seem to shake thoughts of displacement. I remember one morning on the beach I heard a loon cry, and though my field guide told me that those birds winter as far south as Florida, the eerie yodeling sounded out of place, a melancholy song of the north. I watched the pelicans dive for a while, twisting down into the water, following their divining rod bills, and thought about how exotic they would look plunging into Cape Cod Bay (though the rumor is they have now made it as far north as Long Island.) Then I headed back home and made some coffee and got to work on my novel, a book set in the North that I was writing in the South. I had trouble dredging up the specifics of my old home, despite combing the dozen or so journals on the bookshelf next to my desk, and so, procrastinating, I checked my e-mail.

What I found online was not so different than what I’d found on the beach: It was clearly going to be one of those days full of coincidence, the kind you’re not allowed to have in fiction but that happen often enough in life, when many of your worlds–in this case electronic, avian, and emotional–insist on playing the same theme. And there it was. An email from my old friend, Brad Watson, who had written a beautiful Southern novel while living in the North. The e-mail was an exciting one: he had quit his teaching job and moved to a cabin in Foley near the Gulf in Southern Alabama to be close to his son, Owen. He wrote:

I am now officially a hermit, and man you’re right, it feels good, feels right. The beard’s back after an eight month absence, hair sticking up all around the bald spot like wild grass on the rim of a blighted field. This old house smells like woodsmoke. The other night, Owen said, “The smell of this house reminds me of the smell of a house on Cape Cod,” and he was talking about the old Gessner house. So I suppose right now I’m the southern version of you in those days.

In another parallel, it had been Brad’s first book of Southern short stories that had led him north, when he was offered a five-year position as a Briggs-Copeland lecturer at Harvard. Brad liked to play up the Beverly Hillbillies aspect of this move, the country bumpkin strolling into Harvard Yard with a piece of straw between his teeth. Of course he was anything but a rube, and became one of the school’s most popular teachers, though he did make one bumpkin-like decision in choosing to live, not in the urban mix of Cambridge, but down near me in the wilds of Cape Cod. We were introduced by a mutual friend, a Southern writer in fact, and met at a drunken dinner at Bradâs house with our wives where he served Coq au vin, a slow-cooked brothy chicken that you could gum off the bone. We drank too much–this would become a repeated theme–and at one point he admitted he had a 26 year old son, Jason, from his first marriage. I did a little math and figured that meant he’d had his son when he was 16. “You really are a Southerner,” I blurted. Not the kind of thing you want to ever say but especially not on a first friend date. When he laughed instead of scolding me for my stereotyping–a scolding that might have actually happened with other oversensitive Southern writers of my acquaintance–I knew it was the beginning of a beautiful friendship.

At the time we were living a half hour away in East Dennis on the Bay side of Cape Codâagain playing north to his southâbut the next year Brad rented a house less than mile away from us, right on the beach. It was a spectacular house where you could lie in bed and stare out at the rocks and the ocean and every now and then see a breaching whale, and where, on the rocky beach below, you could find stranded loggerhead or Kempâs ridley turtles and the cadavers of coyotes and winter shorebirds like dovekies and gannets. The bluff, which you could see out of the western windows of the house, was where I would eventually set my Cape Cod novel, and the wind would be more than a minor character in that novel, since it never stopped whipping across the Bay and hitting the leeward side of the house with enough force to make it hard to open the door in winter. The wind drove Brad’s wife crazy and made her miss the South, but it also leant a drama to the place that verged on melodrama, as if they were living inside the pages of Wuthering Heights.

It’s hard not to romanticize the year we lived down the street from each other, and I need to remind myself that there were problems for all of us–career-related, familial, marital, even chemical–that made the year less than romantic. But I still can’t help but look back somewhat hazily on that time: I had spent my twenties writing in isolation with no literary community at all, and now, suddenly, I was part of a tiny writing community, a Bloomsbury on the beach. Brad and I would go for runs around the cranberry bog and bat back and forth the various plots of the various books that were obsessing us, and often I would find that he understood the literary allusion I was making or that I understood his, or that we had read the same book, or would soon read that book on the other’s suggestion, and before I knew it we were having, between heavy breaths and plodding steps, a real-live bona fide literary discussion. One thing I loved about those runs is the way our talk ranged from the high to the low. Low crude jokes, occasional high insight. And plenty of shoptalk too: books, sure, but also ways to get ourselves started, that is to make sure we sat ourselves down and got to  typing each day.

There is no Algonquin Round Table without booze, and drinking was also part of the year’s ritual. (I later suggested that Bradâs biography should be called The Sodden Heart.) As it happened there was already a great tradition of Cocktail Hour on that part of Cape Cod. Not much more than a mile way from where we lived the great New England nature writer John Hay had shared drinks with the displaced Southern poet Conrad Aiken in 50s, back when Aiken was collecting the second of his Pulitzer Prizes and still considered on par with T.S. Eliot. No living writer–not Bernard DeVoto with his evocation of the perfect martini or the liquor-soaked Hemingway or even Aikenâs protégé Malcolm Lowry–could match Conrad when it came to the daily glorification of booze. “The ritual of cocktail hour represents the communion of all friendly minds separated in time and space,” wrote Aiken. His poetic elevation of cocktail hour grew so famous that even the napkins used for the Aiken’s pewter drinking goblets later found their way into an Updike novel.

Our nightly boozing wasn’t quite so glamorous. Brad would sip whisky, slouched in his chair and I would swill many beers, and my wife Nina would drink wine. If this wasnât the stuff of literary legend, it worked okay for me. There I was, living on my favorite place on earth, the closest thing I had and would ever have to a Walden, and now I also had a new and dear–and bookish!–friend right down the road, someone who also understood the daily wrestling match with words, and also understood the constant career disappointments–the envy and bitterness and failure, the way the game was so obviously rigged–and who I could drink and laugh about all of it with.

Of course nothing this simple exists for long, if it ever did exist at all outside of stray and random moments. It’s easy enough to make a golden age once the sloppiness of the actual time has passed. By the next year Brad had finally moved up to Cambridge and our friendship had begun to become a long distance one, which it would remain. Brad’s time at Harvard was too complicated to call a triumph, but there were moments of triumph. One was when he imported two of his favorite Southern writers, Barry Hannah and Padget Powell, to speak to a packed house in the Thompson Room below a portrait of Teddy Roosevelt. Hannah, who was very sick at the time, teared up at the podium, saying that he felt “like Quentin Compson come to Harvard,” and that now he knew “this southern boy has made good.” A year later Brad’s five year stint in Cambridge ended and he headed back to the South to teach. Since then I have seen him only occasionally and for very short periods of time.

In the meantime Brad had gone a good while between books, not out of any traditional version of writer’s block–that is out of paucity–but rather out of excess, many different plots competing for prominence in his mind. He finally bore down, and finished his novel, The Heaven of Mercury, during his last two years in Cambridge. Of course, strategically speaking, Iâve gone about this essay all wrong, and by so excessively romanticizing my early friendship with Brad you will never believe me when I tell you that the book he produced during those years on the Cape and in Cambridge is one of our greatest contemporary novels. It will sound like hokum, like nonsense, or, even worse, like that lowest and most deceitful of things: a blurb.

But it’s true. Writers tend to be friends with other writers–it just eventually ends up working out that way–but it doesn’t always happen that your favorite books come from your favorite people. I’ve read a lot of friends’ work that I’ve had to politely praise, but Brad’s book was an exception. I had heard him talk about it often enough on those runs around the bog, but even bad writers can sometimes talk beautifully about their work in abstract. But the thing itself, the final book, was, and remains, a delight. The bookâs main character, Finus, is a man of deep wistfulness and melancholy, a man who admits his own “inability to see the world except through the crinolated filters of self-consciousness need.” But within the bookâs pages Brad himself, as if fulfilling Finus’s wish to “not be who he was” flies from character to character, inhabiting each deeply, from Finus to his unrequited love, Birdie Wells to Birdie’s maid, Creasie, until we experience a full and varied, and yes, slightly sodden, world. There is an element of caricature–like Finus’s mother a “poor God-ravaged grackle of a woman,” or the horse named Dan: “A long, slow fart flabbered from the proud black lips of Dan’s hole…,” or Mrs. Urquhart’s heart, like a “shriveled potato”âand an element of the grotesque, like the scenes of necrophilia or the final mystery of an actual shriveled heart. But this is a humanized grotesquerie. Critics drew comparisons to the usual Southern suspects, Faulkner and O’Conner and Welty, as well as throwing the name Marquez around, due to the magical scenes at the end. But I was reminded of the early Cormac McCarthy, not the cowboy stuff, but the books Brad had turned me on to, the McCarthy of Child of God and, less so, of Suttree. The difference, to my mind, was that Brad’s stuff was better: it scumbled the surface of language and surprised in a similar fashion, but as well as being a pleasure on a language level, it told a story about very human characters, something McCarthy, for all his achievement and renown, does not.

Happily, Bradâs accomplishment did not go unrecognized. Heaven was a great critical success and was a finalist for the National Book Award. For my money, it should have won.

I was quite proud to be mentioned on the acknowledgements page, with a phrase that might have easily come directly from one of our runs. Bradâs nod to me was a simple and practical one: “Thanks to David Gessner for urging me to get on with it.”

* * *

And so Brad was a role model as I sat at my Southern desk staring at my newly-purchased Southern Computer in my Southern Town and trying to resuscitate the dead journal details and to create or re-create my days on Cape Cod. I wanted to write of my fictional Cape Cod in a gritty and particular way and I could think of no better models than the quirky Southern novels I admired, Bradâs not the least among them. Of course there is a tradition of writing about places after you have left them, a tradition every bit as strong as that of writing while in a place. Itâs just that Iâve never been of the Hemingway school, the exile school, evoking childhood Michigan from Paris, but of the Thoreauvian one, writing of a place while still in the infatuated midst of it. So some adjustment was necessary. But there I was, after all, and I wasnât going to be going back any time soon, so I thought I might as well make something of my exile.

The truth is that the more I worked, the more I saw the advantages of holding a place at armâs length. For one thing, now that it was in the past tense, I could see the time we were on Cape Cod as a kind of story with a beginning and end, an epoch in our lives, and could make sense of it in a way I never could while in its midst. And mine wasnât really much of an exile: We would be going back North in the summers, after all, and I could imagine a benefit to this pulsing, to going away and coming back, to seeing a place from afar, and so seeing it new. And this annual cycle included the re-infatuation of seasonal return: my own return right after the bank swallows come back, then the white clouds of beach plum blossoms in later May, the prairie warbler with its xylophone song, the fox kits scampering up the jetty rocks to their den. In fact, thinking about these things made me decide it was time to stop equivocating and get down to my real business, that of imagining Cape Cod. Enough throat clearing. Exile is just another excuse for stopping at the imaginative threshold, the sort of excuse we are always using to stop ourselves short. As Samuel Johnson said, anyone can write anywhere and any time, as long as they set themselves âdoggedly to it.â Or, as Brad might have advised me: time to get on with it.

P.S. I wrote the above a while ago, Iâm honestly not sure how long. About a year ago, in fact very close to exactly a year ago, Brad came down to visit me from his home in Laramie to the house where I was staying in Boulder, Colorado. With Boulder friends our get-togethers usually involve some sort of vigorous hike or bike, followed by a couple beers. But Brad would be arriving at noon and not leaving until the next morning and he had not brought any work out clothes. What would we do for all that time, I wondered. Of course the answer should have been obvious: we would drink. Drink and tell stories.

At one point a Boulder friend, Dave Smith, came over for a visit and ended up listening to us for a while. Brad and my topic was a competitive one and the competition hinged on which of us had written more unpublished books. We werenât talking about mere drafts. We were talking about books that we had worked on over the course of years and had, in our minds at least, finished but that were never published. As I remember it, I âwonâ with something like eight books to his seven. My list included the novel I mention in the essay above. Iâd like to find out more about what Bradâs list included.