Joseph Horowitz's Blog

January 22, 2026

Trump and the Arts

The following article is an abridged adaptation of my January 22 NPR report on recent developments in government and the arts — at the NEA, the NEH, and the Kennedy Center — under President Donald J. Trump. I write: “The arts sector feels invaded by aliens. The incursion is so abrupt, so rude, that it parallels the startling empowerment of Trump loyalists like Kristi Noem and Pete Hegseth. John F. Kennedy and Leonard Bernstein, who once jointly promised a more civilized America, have become ghosts hovering above a scene of chaos.” I also recall the arts advocacy of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy, and take a trans-Atlantic look at a pertinent controversy at the Arts Council England. My “More than Music” program was broadcast via the daily newsmagazine “1A.” I’ve bold-faced some of my findings and assertions. To hear the show, click here.

Last December 7, Donald J. Trump became the first President to present the Kennedy Center Honors. He also played a dominant role in choosing the honorees. Around the same time, the Kennedy Center was renamed the Donald J. Trump – John F. Kennedy Memorial Center for the Performing Arts. Prior to that, President Trump replaced the Kennedy Center board with his appointees and named himself chairman. Richard Grenell, Trump’s onetime Ambassador to Germany, was named the Center’s new President. More recently, the Trump-Kennedy Center and the Washington National Opera, resident at the Kennedy Center since 1971, jointly announced their disaffiliation.

On top of all that, grants and jobs were abruptly cancelled at the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities by Elon Musk’s DOGE task force. A substantial re-allocation of funds was directed toward a National Garden of Heroes. And the latest round of NEH grants included projects awarded non-competitively, and serving a conservative ideological agenda.That’s a radical departure from past practice, a departure that’s provoked Representative Chelie Pingree of Maine to accuse the Trump administration of turning the NEH into a “slush fund.”

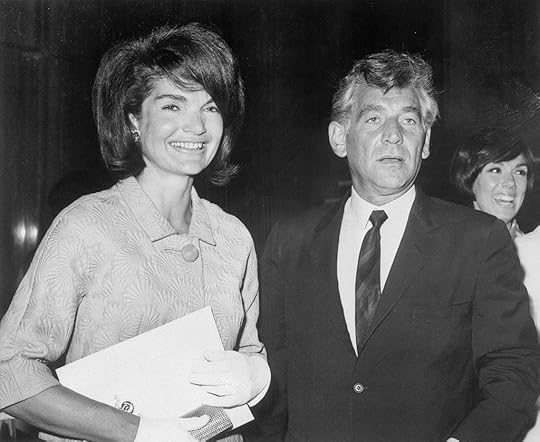

These developments have sent shockwaves through the arts community. While no one can predict what will happen next, the unifying feature of this story is a culture clash – mutual disaffection. The arts sector feels invaded by aliens. The incursion is so abrupt, so rude, that it parallels the startling empowerment of Trump loyalists like Kristi Noem and Pete Hegseth. John F. Kennedy and Leonard Bernstein, who once jointly promised a more civilized America, have become ghosts hovering above a scene of chaos.

As someone who has worked in the arts for more than half a century — who has run a couple of orchestras, who has received innumerable grants from the NEH and the NEA, who has produced concerts at the Kennedy Center – I bring to bear countless personal experiences. Until recently I directed “Music Unwound,” funded four times by the NEH. The last grant, for $400,000, was terminated by DOGE, without explanation, before it was fully expended. In fact, the grant category was eliminated, so there’s no possibility of renewal. According to a notification from the NEH, the termination of Music Unwound represented “an urgent priority for the administration.” It was ended “to safeguard the interests of the federal government, including its fiscal priorities.” A crowning irony is that in a moment when the White House is emphasizing “America 250” – the celebration of American virtues on the occasion of our 250th birthday – it would be hard to find a better example than the NEH Music Unwound project that now no longer exists.

The goal of Music Unwound was to infuse the humanities into the symphonic experience. We mounted thematic orchestral festivals – many dozens of them, in all parts of the United States — that linked to high schools and universities. All the themes asked what it means to be American. There were festivals about Aaron Copland in Mexico, about Antonin Dvorak in New York, about the legacy of Charles Ives. The sleeper turned out to be “Kurt Weill’s America.” It was a story of immigration – how a famous German Jewish composer, fleeing Hitler, turned himself into a leading Broadway composer.

The biggest impact was in El Paso, Texas, where the participating partners were the El Paso Symphony, the University of Texas/El Paso, and the El Paso public schools. One of those schools – East Lake High School – was located in a semi-rural “colonia” in which the vast majority of the residents are categorized as “economically disadvantaged.” Because East Lake High had participated in previous Music Unwound festivals, the groundwork was in place when I showed up to talk about Kurt Weill. Three hundred students assembled in the auditorium. Though very possibly none of them had ever heard of Kurt Weill, I have never known a hungrier audience. Weill was a man who insisted on speaking English from the day he docked in Manhattan in 1935. He revisited Europe once after World War II and reported: “Every time I found decency and humanity, it reminded me of America.”

I shared with the students a film clip of FDR declaring war and played a recording of a song Kurt Weill composed, setting Walt Whitman, in response to Pearl Harbor. It’s called “A Dirge for Two Veterans.” A girl raised her hand to tell us that she had wept twice during the song, at the two places where Whitman and Weill describe moonlight shining on the twin graves of two Civil War soldiers, a father and son. Other songs and stories were shared. When the assembly was over, students crowded the stage. It turned out that the East Lake Chorus wanted to sing for me. They chose “The Star-Spangled Banner.” (You can see and hear that here.)

My visit to East Lake High School was arranged by Lorenzo Candelaria, at that time an Associate Provost at the University of Texas El Paso. It was he who secured the festival partnerships, who arranged for hundreds of high school and university students, and their parents, to attend an El Paso Symphony concert for the first time, who initiated supplementary events – lots of them, in multiple departments – on the university campus. It bears mentioning that the student body at UTEP is 88 per cent Hispanic. More than 90 per cent of the students are local. Anyone with a high school diploma is guaranteed admission.

After the NEH Weill festival, Candelaria invited students to submit written testimonials. One said that she had acquired “a new perspective on my citizenship. I need to be doing way more for my country and its music. I have no excuse, because Weill, an immigrant, devoted his life to it.” Candelaria was reminded of John Kennedy’s iconic admonition: “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.” He told me: “What was really amazing about that student’s comment is that it arose without any prompting or exhortation. It’s something that sprung up very naturally.”

Another Music Unwound topic was “Copland and Mexico.” It tracked Aaron Copland to Mexico in the 1930s, exploring the Mexican Revolution and the cultural efflorescence it inspired. Other Americans seduced by Mexico in those years – by the Mexico of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo – included John Steinbeck and Langston Hughes. The festival – which was mounted in El Paso as well as North Carolina, Texas, Kentucky, Nevada, and upstate New York – also served to celebrate a great Mexican composer, still little known in the United States: Silvestre Revueltas. The audience included more than 650 members of Sioux Falls’s Hispanic community, who received free tickets subsidized by the NEH. Many of them – high school students new to symphonic music — created art projects about the Mexican Revolution. They were displayed in the lobbies of the concert hall. Candelaria commented: “That trip to Mexico was such a transformational experience for Copland. For the students, it’s a story of crossing the border in the other direction for artistic betterment, for intellectual growth. It’s a very important story for them to have heard and learned and experienced. The arts bring people together the way nothing else can. The arts are where people meet.” (You can see an excerpt from “Copland and Mexico” here.)

Another longstanding NEH project, terminated by DOGE, was MUSA — Music of the United States. It’s administered by the American Musicological Society, and to date it’s funded 41 scholarly editions of American music of all kinds – a New World cacophony including spirituals and Native American songs, blackface minstrelsy, early American symphonies and choral works, transcriptions of piano solos by Fats Waller and Earl Hines, and you name it. MUSA began with the American Bicentennial in 1976, which triggered a surge of interest in American music of all kinds among American musicologists who, habitually, had focused on European classical music. That led to a planning conference, funded by the NEH, out of which MUSA was born in 1988. MUSA was the recipient of seventeen consecutive NEH grants, covering half its costs. Individual MUSA editions are elaborately annotated to link to a larger American historical narrative. And of course they make the music itself readily available for performance. A 2018 MUSA edition of Joseph Rumshinsky’s Di Goldene Kale resuscitated a 1923 Yiddish musical, subsequently staged by New York’s National Yiddish Theater – the first complete performance of a Yiddish musical in over half a century. A forthcoming MUSA edition restores the original orchestral score for D. W. Griffith’s 1920 classic silent film Way Down East. The premiere screening with live orchestra will take place at New York’s Museum of Modern Art this coming August.

NEH grants are now up and running again. What happens next? The most recent funding round included a flurry of grants to classical humanities institutes and civic leadership programs positioned to counteract liberal bias in higher education. Mark Clague, the current editor-in-chief of MUSA at the University of Michigan, told me: “For a long time the NEH has been a premier funding source for studying American culture. The shake-up and the cancellation have created uncertainty and ambiguity — a lack of trust in the money, where it’s coming from, how it’s coming, what the purpose is. It’s shaken confidence in the National Endowment for the Humanities.”

Many at the NEH have been let go. One prominent former staff member describes the incursion of DOGE last April as a “bloodbath.” The logic behind it – if any, other than saving money – remains unclear. Over at the NEA, a similar scenario transpired: of staff departures and of cancelled grants – not only of grant applications and grant offers, but, remarkably, of funded grants in mid-cycle. It’s the NEA that, for instance, annually supports institutions of performance like orchestras, theaters, and opera companies. These grants are not large, but for a small orchestra with a budget of $300,000, they can be vital – they can represent up to 10 per cent of an orchestra’s annual income.

As at the NEH, NEA grant opportunities have been reinstated . A complicating consideration is the Administration’s campaign against woke – its rejection of ideological emphasis on diversity, equity, and inclusivity. The language in play can seem chauvinistic, as in a Presidential Action a year ago for “ending radical indoctrination in K-12 Schooling.” “Patriotic education,” it reads, is “grounded in a unifying, inspiring and ennobling characterization of America’s founding and foundational principles, and a clear examination of how the United States has admirably grown closer to its noble principles throughout its history.” That is: grant applicants, right now, feel encouraged to undertake patriotic projects. But some patriotic projects risk seeming insufficiently patriotic.

Typically – up to now – NEH and NEH grants have been adjudicated by panelists. Judging from the latest round of NEH awards, that’s changing. The idea – in the past – has been to insulate the process from political interference. The panelists are picked by the NEH and NEA chairmen and staff members, and – as anyone with experience dealing with NEA and NEH panel comments knows – they can vary widely in expertise and disposition. In the symphonic field, always financially strapped, the climate of anxiety is thick – and it’s difficult to find anyone – any conductor or orchestra administrator – willing to speak out publicly.

An exception, over in Opera, is Francesca Zambello, one of the nation’s most prominent opera directors. In fact, she happens to be the artistic director of the Washington National Opera. As that’s been the resident opera company of the Kennedy Center – now renamed the Trump Kennedy Center – she’s facing an immense challenge. In November, Zambello told The Guardian, in the UK, that donor confidence in the Washington National Opera had been – quote — “shattered,” that the building itself was “tainted,” that patrons were returning shredded season brochures with notes vowing not to return to the Kennedy Center so long as President Trump was in office. Then, on January 9, the Washington National Opera, which annually produces 100 Kennedy Center events, announced that it was disaffiliating and relocating elsewhere. Though both the Opera and the Center said they were parting ways “amicably,” everyone knows there is mutual disaffection, with the Kennedy Center insisting that the relationship had become fundamentally untenable — financially. Working out the details will be immensely complicated, because the affiliation agreement in place since 2011 established that the Center would handle marketing, fund-raising, and public relations for the Opera. There is also the matter of the Opera’s endowment – and who gets that.

Richard Grenell, appointed President of the Kennedy Center last February 10, is a former US Ambassador to Germany without previous experience in arts management. He has been outspoken in the face of the present upheaval. Grenell is critical of what he calls the center’s “previous far left leadership” “Their actions,” he has said, were “more concerned about booking far left political activists rather than artists willing to perform for everyone regardless of their political beliefs.” Above all, Richard Grenell has stressed that he’s inherited a Kennedy Center in financial trouble, that the Center must opt for more popular, less “woke” programs – programs that will excite donors. Retaining the current partnership with the Washington National Opera, in his opinion, would not be “financially smart” for the Kennedy Center. He also maintains that the Opera has long been financially weak, that that’s why it affiliated with the Kennedy Center in the first place, and that it finished fiscal 2025 with a $7.2 million deficit.

His formal statement to the press read: “The Trump Kennedy Center has made the decision to end the EXCLUSIVE partnership with the Washington Opera so that we can have the flexibility and funds to bring in operas from around the world and across the U.S. Having an EXCLUSIVE relationship has been extremely expensive and limiting in choice and variety. We approached the Opera leadership last year with this idea, and they began to be open to it.”

Francesca Zambello denies that the Washington Opera was running a deficit. She also says that the Kennedy Center had not previously impacted on casting and repertoire at the Opera. Like others in the arts sector, she questions Richard Grenell’s repeated insistence on “revenue neutral” programing that will not run a deficit. “He is using a term that we don’t traditionally use. I don’t think that Ambassador Grenell really has taken on board how not-for-profit sector works for the performing arts at the Kennedy Center. The model that he’s proposing does not accommodate our artistic mission, where we balance popular works with lesser known operas. Revenue from major productions traditionally subsidizes the smaller, let’s say, more innovative works. And that has been our model since I have been at the Kennedy Center for 14 years.

“We found that our audiences and our donors dropped off significantly since the management change. And so when you’re losing 40% of your audience or 50% and your contributions are down as much, of course, it’s very difficult to sustain the model. Also, the development staff of the Kennedy Center was greatly depleted, as was PR and marketing. So if you don’t have that staff, it’s very hard to fundraise. But in the end, all performing arts organizations rely on their audiences. And if your audience is there, they are there to support you. And if they’re not there, then you have to change your model.”

Meanwhile, the National Symphony Orchestra, the Kennedy Center’s most prominent constituent, is also experiencing plunging ticket sales. Grenell has instructed the orchestra to begin every concert with the Star-Spangled Banner in celebration of “America 250.” And the National Symphony has done so, usually without a conductor. Many would consider prefacing a Mahler symphony or Brahms concerto with the national anthem an aesthetic gaffe. Meanwhile, the Kennedy Center is being hit with cancellations – artists who have decided not to perform there. Washington Performing Arts – the city’s biggest classical music presenter, aside from the Opera and the Symphony – is also taking its concerts to other venues.

If there’s a positive spin here, it’s that the new management of the Kennedy Center has demonstrated impressive access to corporate and individual wealth, including $23 million raised by the Trump Kennedy Center Honors and a gala for the National Symphony, with 450 attendees, that raised $3.45 million. Many new donors, the Center says, are newcomers excited by – quote – “commonsense” reforms. According to Richard Grenell, the implications for programing are significant.

***

A rather famous sentence from President John F. Kennedy’s most celebrated address extolling the American arts, delivered at Amherst College mere weeks before he died, reads: “ I look forward to an America which commands respect throughout the world not only for its strength but for its civilization as well.”

Kennedy was an eloquent advocate for the arts – and this feature of his Presidency was gathering momentum at the very moment he died. He was about to name Richard Goodwin – a young activist, part of the inner circle of Kennedy’s New Frontier – his arts advisor. And the First Lady, Jackie Kennedy, was herself a passionate and influential enthusiast for the performing arts. The topic is complicated, because Kennedy himself, though an avid reader and an impressive thinker, was no aesthete. And he was ideologically disposed to oppose government arts grants. Instead – remember, this was during the Cold War – he emphasized the achievements of free artists in free societies. In his view, the artist was ideally autonomous, unencumbered, not beholden to government or any other external impingement on the creative act.

Fredrik Logevall is midway through a landmark Kennedy biography. I asked him to speculate what a full-term Kennedy presidency might have meant for the nation’s cultural life. “We know he was proud of that Amherst speech. In my view, the arts would likely have been elevated in the remainder of his first term. He had a lifelong interest in poetry, in literature, in the spoken word. He was a voracious reader. Jackie often marveled at his incessant love of reading. Even though he wasn’t somebody who loved, say, classical music or art per se, he understood the importance of it.” Logevall speculates that Kennedy would have changed his mind about opposing direct government arts subsidies. And he stresses Richard Goodwin’s eloquence as a speechwriter, and the energy that Goodwin had brought to the Administration’s Latin America policy. Goodwin would have made a difference. The Goodwin appointment, which the New York Times reported the day Kennedy was shot, is a wild card in any American narrative tracking government and the arts. The reason it looms immensely is that, after Kennedy, no President undertook a comparable initiative to integrate arts policy as a White House priority.

And today the American arts are in crisis. The crisis has many aspects. One is the shortness of American memory – a condition of pastlessness, never more pronounced than today, that stifles lineage. Creative achievement feeds on past achievement, on roots and tradition. More prosaically, there is a funding crisis little known or understood outside the arts sector. There was a time when wealthy philanthropists subsidized American orchestras and museums as a matter of course – it was part of their lifestyle. And there was a time, after that, when American corporations fulfilled a similar opportunity. And then there came a time when the major national charitable foundations – like the Ford Foundation when it gave over $80 million to 61 American orchestras in the 1960s – undertook to fund innovation in the arts.

To a remarkable degree, those times are behind us now. Young Americans of vast wealth are less likely to support orchestras and museums. And over the past decade the foundation community has emphasized social justice initiatives over arts institutions. These are developments that logically mandate a bigger role – even a much bigger role – for government. But nothing of the kind seems remotely imminent.

To glimpse the magnitude of this sea change, consider the case of Henry Higginson. It was his life ambition to create a permanent orchestra for the city of Boston. He went into banking, and at the moment he could afford it, in 1881, he announced the creation of the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Because Higginson happened to be musically trained – in Vienna, no less – he could do everything himself – he chose and hired the conductors. He paid the musicians. He made up the deficits. He also built Boston’s Symphony Hall. There was no board of directors. This colossal achievement stands alone. It is something unthinkable today.

Here’s another story. In the early days of commercial television, the CBS network notably produced a series of arts showcases beginning with Omnibus in 1952. That was how Leonard Bernstein first wound up on national TV. Its successors were Ford Presents and Lincoln Presents – arts programing, paid for by the Ford Motor Company, in which Bernstein continued to play a featured role. Bernstein was at the same time touring with the New York Philharmonic as a cultural ambassador. Charles Moore, a vice president of the Ford Motor Company, happened to visit Berlin, where he decided that the United States would be inadequately represented at the forthcoming West Berlin Music, Drama, and Arts Festival. At the time, West Berlin a crucial Cold War outpost, a fraught West German island surrounded by Communist East Germany. As Ford was the ongoing sponsor of Bernstein’s TV specials, and as Bernstein was now an accredited diplomat, Ford put up $150,000 to send Bernstein and the Philharmonic to Germany.

When he returned home, Bernstein said: “I think government support of the arts is on the way, and I’m all for it. Meanwhile, it is the responsibility of the wealthy corporations to support our artistic institutions privately – that is, until generous government support, with a minimum of strings attached, is forthcoming. Someone has to do the work the government should do, otherwise we’ll be in an arts vacuum.” Bernstein’s Berlin visit also generated a 1959 “Ford Presents” special on CBS.

So here we are 66 years later. We now have government support for the arts. But it could not be described as “generous,” and whether there’s still “a minimum of strings attached” is suddenly open to question. It bears remembering that the NEA and the NEH, signed into law by Lyndon Johnson two years after John Kennedy died, were not the first direct US Government arts subsidies. During Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Works Progress Administration – the WPA – undertook to employ writers, composers, visual artists, and performers via Art, Music, and Theater Projects. The Music Project alone gave 225,000 free or popularly priced performances, attended by 150 million people, many of whom had been strangers to live concert music. American music was stressed. Among the many orchestras started under WPA sponsorship was today’s Utah Symphony.

Then, following the Great Depression, came World War II. What might have happened to New Deal arts subsidies had Roosevelt survived the war and completed his fourth term? Might government support of the arts have resumed? I asked David Woolner, who’s an historian of the New Deal. “I think it’s quite possible,” he said. “Roosevelt was a great lover of history and a great lover of culture. He was the one who came up with this idea of putting murals in public places, and there was a wonderful program involved in having murals painted on post offices across the country by local artists, which would depict the local history of the community.”

Woolner contrasted the WPA’s dedication to documenting American life with the current Administration’s emphasis on celebrating American greatness: “I think there’s a great differences between an ideological use of history as a means for promoting a particular political point of view and what was happening in the 1930s. The government was asking the Farm Security Administration photographers to go out and photograph terrible conditions so as to help propel reforms that would alleviate poverty in the United States. That’s quite different than saying to the Smithsonian Museum, ‘Your depiction of slavery is too harsh.’”

For a final perspective on what’s going on, I talked to Nicolas Kenyon. He’s been a seminal figure in British musical life. He’s run the BBC Proms. He’s run London’s Barbican Center. Britain has been weathering a volatile arts crisis of its own, focused on the body that oversees government arts funding: the Arts Council England. And the outcome of that crisis, to date, seems instructive, not least for the United States. Here’s what Nick told me about the Arts Council:

“It’s supposed to make its own decisions, it’s supposed to be answerable to government, of course, for the money that it spends, but it is not meant to be something which the government instructs. And that was called into question a couple of years ago now by a very conservative Secretary of State for Culture, Nadine Dorris, who started telling the Arts Council what it ought to be spending its money on. And that’s an immediate red flag here. And the principle that she was trying to instruct them to follow wasn’t something that was necessarily a bad thing. She wanted more of the Arts Council’s money to be spent out of London, around the UK, offering more opportunities for more people who were not in the big metropolitan centers to encounter the arts. Absolutely fine, but what happened as a result was a complete shambles of peremptory withdrawing of grants to, say, Glyndebourne Touring Opera, or Welsh National Opera, or English National Opera in London, which was told overnight that they would lose their grant unless they moved from London to Manchester. A very worthy aim, no doubt, but something impossible to achieve overnight and something that should have been consulted on, planned, and considered carefully before making any decisions.

“So that was a moment for the UK to get very concerned about where government funding of the arts was going, particularly since those funds themselves had, like so many other areas in so many other countries, been diminishing over the years. So each pound was more precious, if you like. And that gave rise to a real lack of faith by arts bodies in the Arts Council. And in the end, the government had to order a review of the Arts Council.

“Now, in between these two events, the government had changed from Conservative to Labour. So it was a different Department of Culture ordering this investigation into what had gone wrong at the Arts Council. And that was undertaken by a very experienced lady called Dame Margaret Hodge, who reported just before Christmas. So we’re talking just a couple of weeks ago and produced a pretty devastating report on the state of the Arts Council.”

Kenyon went on to say that the Hodge Report turns out to be, in his opinion, a very good thing. Not only does it frankly criticize the Arts Council for the way it’s been spending money; it’s full of constructive suggestions, including new strategies to incentivize corporate and philanthropic giving. The analogies here to what’s happened at the NEA and NEH, and at the Kennedy Center, couldn’t be louder – the peremptory decisions, the loss of confidence. And the kicker, more important, is: the British government ordered a considered follow-up: an honest inquiry into what went wrong, how to fix it, and more generally how to attend to growing concerns about funding the arts – and the place of government.

It all brings back to mind John Fitzgerald Kennedy’s advocacy of the arts, and his pending appointment of Richard Goodwin to be his arts advisor. That appointment – something I didn’t mention before – was the result of a 36-page report, “The Arts and the National Government” commissioned by Kennedy. Everything was in place for a comprehensive attempt to figure out, for the first time, how the various agencies of the federal government impact on the arts, to assess that, and to plot strategies for the future. It never happened.

The entire saga of government and the arts, as it’s unfolded in the United States beginning with the New Deal, is partly a saga of leadership. FDR and JFK were leaders who cared about the arts. So did Nelson Rockefeller, when the New York State Council of the Arts, a precursor to the NEA, was created during his governorship. Kennedy had a partner in arts advocacy who must also be mentioned. It was Leonard Bernstein, for whom the Kennedy White House signified the more civilized America the President anticipated. Kennedy and Bernstein bonded; they were incipient comrades in arms. For Bernstein, the Kennedy assassination was a linchpin event in American decline. But he maintained a close relationship with Jackie Kennedy, who urged him to take over the Kennedy Center. Bernstein thought that job was not for him – but he did agree to compose something for the opening, in 1971. It turned out to be an anti-war, anti-Vietnam Mass.

Bernstein embodied a style of fearless arts leadership unknown in the United States today. It was first apparent when he took his New York Philharmonic to Soviet Russia in 1959, and refused to do the Russians’ bidding. Were he around now, he would be speaking up about the cancellation of arts grants. He would be apoplectic about the renaming of the Kennedy Center.

Another matter, however, are accusations – from Richard Grenell and many others – that the endowments and the Kennedy Center are too “woke.” In my world of classical music, no one disputes the validity of the goals: diversity, equity, inclusivity. But many feel – privately – that implementation is too often ill-informed. As for the endowments – in my experience, as a frequent applicant and recipient going back to the 1980s, as someone who’s dealt for decades with staff members and who’s read countless panel reports adjudicating grants – I think the NEA and NEH are less distorted by so-called wokeness than our major charitable foundations, which used to generously fund orchestras and were a crucial support for innovation in a very conservative field. The tipping point was in 2011, when a 40-page position paper persuaded philanthropists that the arts, historically, are essentially instruments of social justice.

“Music Unwound” as in El Paso, cancelled by DOGE, showed how the arts can be a unique instrument for mutual understanding, for personal identity and national identity. It aspired to curate the American past without special pleading to the left or right, to celebrate America honestly.

When the Kennedy Center decreed that every National Symphony Orchestra performance begin with the Star-Spangled Banner, that was a top-down edict. It tarnished the gesture. When, during a Kurt Weill festival supported by the NEH, the student chorus at El Paso’s semi-rural East Lake High School mounted their auditorium stage to sing the Star-Spangled Banner for me, that was a spontaneous affirmation of gratitude for the opportunities they enjoyed as Americans. It wasn’t scripted. It was utterly sincere.

My book on government and the arts is “The Propaganda of Freedom: JFK, Shostakovich, Stravinsky, and the Cultural Cold War“

January 14, 2026

My New Novel: “The Disciple”

My forthcoming novel, The Disciple: A Wagnerian Tale of the Gilded Age, may be my best book. A prequel to The Marriage: The Mahlers in New York (2023), it’s already available via pre-order. (And if you order both books, you get a discount.)

My story tracks the prodigious American impact of Richard Wagner’s protégé Anton Seidl. It challenges obstinate stereotypes of Gilded Age luxury and decadence. Publication, on March 24, coincides with the Metropolitan Opera’s new production of Tristan und Isolde – whose 1886 American premiere, conducted by Seidl, begins my chapter one.

Cloaked in mystery, Seidl materialized in the New World as Wagner’s personal emissary. He commanded musical New York and toured widely, everywhere received with awed deference. In Brooklyn, Laura Langford’s Seidl Society presented summertime Seidl concerts on Coney Island fourteen times weekly. Working women arrived in special railroad cars; Black orphans were regaled with roast chicken, ice cream, and the Tannhäuser March. A clairvoyant theosophist, Langford identified Seidl as a “chela” and traced the ceremonies of Parsifal to the Himalayas. Seidl’s appeal was uncanny; at the American premiere of Tristan und Isolde, women stood on their chairs and “screamed their delight.” At his funeral, women clasped elbows to force their way into the mobbed Metropolitan Opera House, a spectacle of chaos. His Manhattan friends—including Antonin Dvořák, whose New World Symphony he premiered—were legion. And yet Seidl remained a man apart, afflicted with secret sorrows.

ADVANCE PRAISE:

“Joseph Horowitz’s captivating novel of the Gilded Age comes alive through the saga of an overlooked genius: Wagner’s protégé Anton Seidl. He transfigures the vibrant world of American classical music at the dawn of the 20th century into a compelling narrative commanding in detail. And he yet again challenges our mounting cultural amnesia.” — Thomas Hampson

“For several decades now, Joseph Horowitz has been our Cicerone through the vibrant scenery of classical music in Gilded Age America. Such is his love for that almost forgotten chapter of our history that he felt moved to transpose his unmatched knowledge of the era to the more easily accessible plane of fiction. The Disciple moves dexterously among New York, Bayreuth, and Brooklyn, glimpsing a memorable rendezvous of Wagnerism and Feminism. Those who love the cultural history of New York will come away both enriched and enlightened.” — Hans Rudolf Vaget (Shedd Professor of German Studies and Comparative Literature Emeritus, Smith College)

“The Disciple will astonish readers with its insights into an extraordinary but little-known American artistic epoch. The re-creation of Antonin Dvorak is absolutely magical – poetic, tender, funny, irresistible. It evinces Horowitz’s love for the man and his music, brought to life in the most fascinating and beautiful way.” –JoAnn Falletta, Music Director, the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra

“Joseph Horowitz’s knowledge of the great Anton Seidl—one of the most charismatic figures of the Gilded Age—is second to none. He also possesses a remarkable capacity to weave a compelling fictional narrative. I learned a lot about Seidl, about the social milieu that he seduced, and about the thrilling musical life that he dominated.” — Barry Millington (chief music critic for The London Evening Standard and editor of The Wagner Journal)

January 9, 2026

John Luther Adams on “Why I Moved from the US to Australia”

A couple of my recent blogs – here and here — have saluted John Luther Adams as “among the most esteemed present-day American composers for orchestra. . . . Encountering Adams’s Become Ocean on a 21st-century symphonic program is so fundamentally enthralling that it risks cliché. It is the proverbial oasis in the desert. The Sahara here is contemporary American concert music inscribed in sand.”

Long a resident of Alaska, then of the American southwest, Adams moved to Australia two years ago. In a recent piece for Australia’s The Saturday Paper, he addresses “Why I moved from the US to Australia.” You can read it here.

Some excerpts worth pondering:

–“The culture creates the politics and, with tongue lightly in cheek, I’ve taken to referring to my wife and myself as ‘cultural refugees.’ The relentless commercialization, rising tides of xenophobia, the strident acrimony of social discourse, the violence and the increasingly hysterical tenor of life in the USA have simply worn us down. We are among the few privileged enough to be able to leave.”

–“I’ve come to believe that ultimately art does more than politics to change the world. Music is not what I do, it’s how I understand the world.”

–“I don’t believe that politics will change fundamentally until culture changes. Throughout history, the ideas that transform societies have come from writers, painters, novelists, poets, even composers. From scientists, philosophers, theologians and others whose lives are dedicated to asking new questions, to seeking beauty and truth, not power.”

January 7, 2026

“Ur Kind of Music?”

I cannot think of a better conversationalist about music, and about the state of things musical today, than the conductor Kenneth Woods. Ken is an American based in the UK, where he conducts the English Symphony Orchestra in Worcester and resides in Wales. He programs bravely and insightfully. He presides over a Mahler festival in Boulder and an Elgar festival in Worcester.

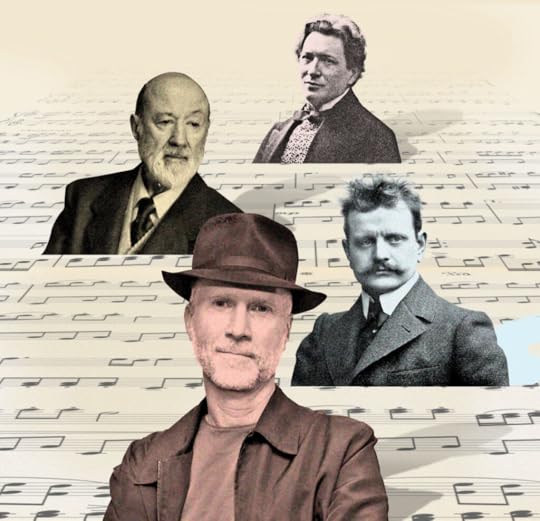

Ken just posted our second podcast: “Is This Ur Kind of Music?” The starting point is my recent rant about the music of the future, pondering the pertinence of Ferruccio Busoni’s notion of a primal “Ur-Musik” – and applying it to music by Sibelius, Busoni, Ives (his Universe Symphony) and John Luther Adams.

To revisit our first, no-holds-barred podcast, “The Making and Unmaking of Classical Music in America,” click here.

January 6, 2026

Was Sid Caesar’s Cancellation a Media Parable for Today?

It must mean a lot that I can remember watching Sid Caesar’s “Show of Shows” on TV with my parents as a young child. For one thing, I don’t recall watching anything else as a family. For another, Caesar’s “Show of Shows” went off the air in 1954 and I was born in 1948. So I was all of six years old. The memory stuck.

Caesar virtually disappeared from television when “Caesar’s Hour” – his sequel show — was cancelled by NBC in 1957. But Caesar’s reputation as a comic genius, a talent to set beside Chaplin and Keaton, more than lingered. Then in 1973 “Ten from ‘Your Show of Shows’” – grainy kinescopes – turned up in movie theaters. To this day, no other comedian makes me laugh myself prostrate to the floor.

The Caesar career was famously short-lived; he was all of 35 when he lost his weekly TV berth. It was always my understanding that he simply burned out, that doing live TV full tilt every week — the ruthless schedule, the manic energy – was just too much. And Caesar was visibly high-strung: he stammered, he coughed, he frayed. The desperation he enacted was both funny and real.

From David Margolick’s new biography When Caesar Was King I now learn, however, that the king was partly dethroned by Lawrence Welk, who showed up nationally on ABC in 1955 and slaughtered Caesar’s ratings. Consciously and strategically, Welk embodied the bland. His band’s “bubble music” was engineered to smooth and soothe. Sampling Welk on youtube, I discovered a single Black guest artist – a smiling tap dancer who made the show seem even whiter.

That Welk’s own delivery was blank was his very signature. His instrument was the accordion. His core audience included elderly ladies for whom Caesar was a neurotic anomaly. One Iowa dentist claimed that NBC was trying to “ram” Caesar “down our vision.” “In some magazine I noted that Sid Caesar was rated the wit of the year,” she told the Chicago Tribune. “Should that be so, I’m Samuel L. Clemens’s twin sister.” The Nashville Banner invited readers to chime in. “I don’t like ‘Your Show or Shows’ either and don’t know anyone who does,” wrote Mrs. Gladys Miller. “If all of TV was like ‘Your Show of Shows,’ there would be no market for TV sets,” testified Mrs. R. E. Farris.

At the same moment, NBC’s press department boasted: “The small town this generation has known has ceased to exist. Television has created similar tastes in all sizes of communities. Sectionalism and regionalism are vanishing as people sit in their living rooms, looking into the magic window of television.” Margolick comments that it proved hard to abandon the “starry-eyed notion that folks outside big eastern cities would be thrilled to have sophisticated entertainment dumped on their doorstep. But in what one advertising derisively called ‘East Cupcake, Iowa,’ this wasn’t necessarily so. Far from binding together two different Americas, television only heightened – and, maybe, even widened – the chasm.”

Was Sid Caesar’s cancellation by NBC some kind of parable? Is it pertinent to Donald Trump’s America? To the impending cancellation of Stephen Colbert by Paramount? To the ongoing conglomeration of big media?

Newton Minow, as JFK’s chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, in 1961 famously called TV “a vast wasteland.” That was half a century before Trump’s FCC chairman, Brendon Carr, threatened to revoke the licenses of ABC affiliates who carried Jimmy Kimmel. As I happen to know a thing or two about cultural programming during the early decades of commercial television, I can put Minow’s complaint in another context: the wasteland was not uniform. Caesar actually fit into a corner of creativity.

When we think of television heroes from the 1950s, the marquee name is CBS’s Edward R. Murrow, who stood up to McCarthy and in 1958 warned that commercial TV, driven by profit, was insulating Americans. Six years before that, “Omnibus” debuted on CBS. It was an arts showcase urbanely hosted by Alistair Cook. Leonard Bernstein’s TV career – a landmark in musical pedagogy — began on “Omnibus” with an exploration of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony in which he pondered the composer’s discarded sketches.

But what first bears mentioning is that Bernstein was blacklisted when in 1954 Robert Saudek invited him onto “Omnibus.” More than an enlightened arts initiative, his engagement was an act of defiance that effectively reactivated Bernstein’s American career, and not only on TV. Bernstein’s “Young People’s Concerts,” also on CBS, began in 1958 and ran until 1972 – 53 programs in all. Bernstein’s YPC producer was Roger Englander. When President Kennedy was shot, Englander was instantly on the phone. CBS scheduled Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic in a memorial concert — a performance of Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony, with soloists and chorus – that was aired live just two days later.

The most prominent commercial sponsor of Bernstein’s early TV work was the Ford Motor Company. At one point in the relationship, Charles Moore, a Ford vice president, visited West Berlin, then a West German island surrounded by Communist East Germany. Moore decided that the United States would be inadequately represented at a forthcoming festival. Ford put up $150,000 to send Bernstein and the Philharmonic to the West Berlin Music, Drama, and Arts Festival – and turned it into a 1960 “Ford Presents” special on CBS.

Over at NBC television, David Sarnoff’s prime cultural initiative was a series of live concerts, including complete operas, featuring Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony (1948 to 1952). Sarnoff also created an English-language NBC Opera stressing contemporary and American repertoire. Born in a Russian shtetl, Sarnoff was a driven, self-made tastemaker without formal education. In his youth, he acquired a reverence for symphony and opera. But for Sarnoff Sid Caesar must have seemed a mere comedian.

As Margolick makes clear, Caesar on NBC was pegged by many Americans as “elitist,” even “intellectual.” He was also (like Leonard Bernstein) self-evidently Jewish. His producer was Max Liebman. His writers included Mel Brooks and Woody Allen. His fans included Bernstein, who would re-enact Caesar’s parody of insomniacs for his children. Though it would not have occurred to me to group Caesar and Bernstein together, on second thought many Caesar skits parodied high culture. For instance: they assumed audiences knew the fashionable Japanese art films that inspired “U-Bet-U,” in which Caesar plays a clumsy samurai warrior.

Most notably, Caesar – himself a trained musician who once played his saxophone professionally — took on classical music and opera, a specialty that peaked during his last seasons as a TV regular. I am thinking, for instance, of “Gallipacci,” the Pagliacci spoof that opens with a mercilessly banal production number: “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town” rendered in Italian double talk.

But the coup de grace was Caesar performing Grieg’s Piano Concerto. Though I adore Victor Borge, Caesar’s parody is supreme. Working with his in-house pianist, the formidable Earl Wild, Caesar sits on a piano bench facing the audience, playing an invisible keyboard on an otherwise vacant stage. The manic hilarity of this act was predicated on a labor of love: split second coordination of Caesar’s hands and fingers with Wild’s off-stage manipulations of virtuoso passagework, including planned wrong notes and tasteless sentimental rubatos. It was all choreographed in a matter of days, then flawlessly executed on live TV. There exist several versions; the one to watch is here.

Caesar’s comedy was never political. It was never explicitly Jewish. But it was fundamentally disruptive, with everything else fair game: Hollywood films, Broadway plays, health food restaurants, rock ‘n roll, progressive jazz, corporate boardrooms, and popular TV shows not excluding Lawrence Welk. A spirit of demolition reigned unchecked. Many sensed this and objected. For others, Caesar’s humor was as cathartic as any other form of sublime artistic expression.

I assume that Sid Caesar would not appeal to today’s emerging national culture tsar. Caesar was too fundamentally irreverent and hence dangerous. Scanning the more than 250 names proposed for Donald Trump’s impending National Garden of Heroes, I find a single comedian: Bob Hope. In fact, Caesar is not even among the comedians awarded Kennedy Center [sic] Honors, a long list including Danny Kaye, Bill Cosby, Steve Martin, Mel Brooks, Billy Crystal, and Lily Tomlin. Perhaps that’s incidental. Or perhaps it registers the “chasm” dividing two Americas that David Margolick links to television in his biography of TV’s most original star.

For a related blog on Trump, JFK, Bernstein, and the arts, click here.

December 23, 2025

Who Wrote “Porgy and Bess”?

It must mean something that the highest creative achievement in American classical music is permanently controversial. When Porgy and Bess premiered on Broadway in 1935, a typical critical reaction was: “What is it?” American-born classical musicians (unlike their European-born brethren) marginalized George Gershwin as an interloper, a gifted dilettante. Later, in the 1950s, Porgy and Bess was widely criticized for “stereotyping” African-Americans. But this is a decade during which Porgy and Bess was not much seen, excepting a mis-cast, misconceived Hollywood version mangled by Samuel Goldwyn as a labor of love. Beginning in the 1970s, it belatedly entered the mainstream operatic repertoire – yet still excited discomfort (but not among singers who actually sang it).

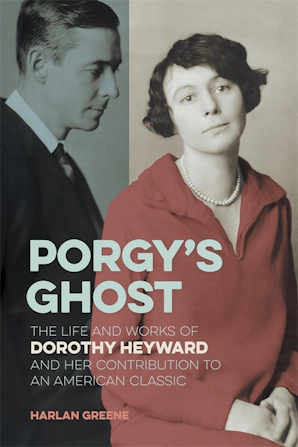

Not the least controversial aspect of Porgy and Bess remains: who created it? The Gershwin Estate mandates that all performances be billed “The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess.” But that’s not right. First there was the 1925 novel Porgy – a glimpse of Carolina’s creole Gullah culture. It was written by DuBose Heyward, a genteel southerner whose curious arms-length view of the Gullahs was part cultural anthropology, part awed mythology. Then came the 1927 play Porgy, until now attributed to Heyward and his wife Dorothy; its success, however, was partly due to the machinations of its 29-year-old immigrant director, Rouben Mamoulian. Mamoulian’s elaborately stylized production, which spurned verisimilitude, was packed with music. Then Gershwin turned Porgy into an opera, also Mamoulian-directed, whose libretto closely followed the script of the play. The lyrics for its songs were mostly composed by DuBose Heyward, with an assist from Ira Gershwin. Thanks to Harlan Greene’s beautiful new biography – Porgy’s Ghost: The Life and Works of Dorothy Heyward and her Contribution to an American Classic — we now know that the play Porgy was essentially written by Dorothy Heyward. That means that the opera libretto, too, is basically hers.

Beyond correcting attribution, does it matter? Well, yes – because the genealogy of Porgy and Bess helps us understand its content and its tone. As Greene makes abundantly clear, Dorothy was a northerner whose attitude toward Black Americans was more enlightened than her husband’s. DuBose’s novel ends with Porgy drifting into obscurity after Bess has dropped him. Dorothy’s play ends with Porgy exclaiming “Bring my goat!” – he’s going to find her. DuBose’s Porgy is a curiosity, a loser; Dorothy’s attains stature as a cripple made whole, the moral compass of the community. This difference correlates with changes in plot and perspective both numerous and fundamental. Greene writes: “Her play is no longer just a peep over the color wall into an ’exotic’ community . . . The whole trajectory of the piece is changed, uplifted to loftier art and social commentary.” Greene also shows how Dorothy’s modesty, the eager self-abnegation with which she endeavored to ensure that her husband’s contributions to the opera were not overlooked, ultimately backfired. This excruciating tale, whose villains include Goldwyn, the Hollywood agent Swifty Lazar, and Ira’s wife Lee, culminated in Dorothy’s nervous breakdown.

Greene’s empathy for his subject, and the tenacity of his research, are beyond praise. At the same time, his loyalty to Dorothy inescapably colors his view of Ira Gershwin and also of Mamoulian. He regrets that Sporting Life, the snake in the grass who lures Bess away, is handed an irresistible Gershwin/Ira Gershwin song: “It ain’t necessarily so.” For Dorothy, Sporting Life is a darker force. For the Gershwins, for Mamoulian, for John Bubbles who first sang and danced the role, Sporting Life does not lack charm (in later life, criticizing a Los Angeles production, Bubbles insisted that Bess deserved a credible seducer). And Dorothy’s perspective was at odds with the epic showman in Mamoulian, whose template for both play and opera was indebted to his 1926 Rochester production of Maurice Maeterlinck’s Sister Beatrice: a miracle play with music yielding an ecstatic redemptive ending.

The Heywards did not want Mamoulian to direct Porgy and Bess. Gershwin did. These entanglements will never be wholly untangled: the opera’s vicissitudes are baked in, and archival documentation fails to clarify whether late changes to the play in Mamoulian’s hand – crucial changes — are his or Dorothy’s or a combination of both.

In later life, Dorothy’s output notably included Set My People Free (1948), about a free Black man convicted of planning an 1822 slave revolt. But she never wrote another play nearly as successful as Porgy. In Greene’s portrait of a creative woman caught in a man’s world, her failure to adequately assert herself is an ongoing motif. His biography ends: “Dorothy Heyward remains . . . the ghostwriter of the opera who flits past the audience to haunt Porgy and Bess. . . Her specter is present whenever the curtain goes up, and it is most especially present when it goes down on the transcendent ending she crafted for it, an ending so vastly different from the self-effacing one she fashioned for herself. But that, in the end, is how she wanted it.”

My pertinent book is “‘On My Way’ — The Untold Story of Rouben Mamoulian, George Gershwin, and ‘Porgy and Bess.'”

For a pertinent blog linking to my NPR show arguing that it’s OK for white baritones to sing Porgy, click here.

December 20, 2025

The Music of the Future?

The current issue of The American Scholar includes a long piece of mine suggesting a possible new direction for contemporary classical music – versus the “makeshift music” that deluges our concert halls. I make reference to John Luther Adams, Charles Ives, Jean Sibelius, and Ferruccio Busoni. To read the whole piece, click here. To sample it, read on:

The American arts are receding and blurring. Cultural memory—a prerequisite—is fast disappearing. American orchestras, espousing the new, privilege a surfeit of makeshift eclectic music dangerously eschewing lineage. American opera companies flaunt new American operas that are here today and gone tomorrow. What is needed is an informed quest for orientation, for future direction.

The Italian-born composer-pianist Ferruccio Busoni was a clairvoyant who will never cease to magnetize a coterie of adherents. In his Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music (1907), Busoni proposed the notion of “Ur-Musik.” It is an elemental realm of absolute music in which composers have approached the “true nature of music” by discarding traditional templates. Sonata form, since the times of Haydn and Mozart a basic organizing principle governed by goal-directed harmonies, would be no more.

Half a century ago, Ur-Musik could be written off as a faint footnote to twin seminal 20th-century currents: Igor Stravinsky’s neoclassicism and Arnold Schoenberg’s serial rigor. But no longer. John Luther Adams, among the most esteemed present-day American composers for orchestra, embraces something like it. And his forebears include composers of renewed consequence: Jean Sibelius in his primordial tone poem Tapiola (1926) and Charles Ives in his unfinished Universe Symphony (begun in 1915).

Around the same time, before locking on his 12-tone rows, Schoenberg experimented with an unmoored nontonal style. He was concurrently corresponding with Busoni, who also conferred with Sibelius. In an email exchange, I learned from Adams that, while composing his Pulitzer Prize–winning Become Ocean (2013), “the only music I was listening to was Tapiola.” I brought up Ives’s Universe Symphony and suggested that Adams was “post-Ivesian.” He readily agreed. So there are dots—big ones—to connect.

Might there not be lineage here?

For much more on Busoni, click here .

December 18, 2025

Trump vs. the Kennedy Center

Mere hours before its board renamed the Kennedy Center for Donald Trump, Persuasion ran my online piece on Trump, the Kennedy Center, JFK, and Leonard Bernstein. I will be following up with a 50-minute “More than Music” feature on NPR, to run in January. Here’s the Persuasion article:

When people today ponder the assassination of John F. Kennedy 62 years ago, possibly the question most asked is: Would Kennedy have pulled American troops out of Vietnam? But in light of President Donald Trump’s makeover of D.C.’s Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, it becomes equally pertinent to inquire: What might have been the consequences of Kennedy’s espousal of a “more civilized” America?

Twenty-seven days before he died, President Kennedy delivered an arts address at Amherst College. He said in part: “I see little of more importance to the future of our country and our civilization than full recognition of the place of the artist.” Four weeks later Kennedy was poised to announce the appointment of Richard Goodwin, an inner-circle New Frontier activist, as his arts advisor. Though the president was no aesthete, he was a cultural Cold Warrior intent on challenging Soviet Russia in every department of human activity—including the performing arts in which Russia excelled. And he respected and admired his First Lady’s impassioned engagement with music and dance.

A notable third party in this endeavor was Leonard Bernstein, then music director of the New York Philharmonic. Bernstein tirelessly advocated for a more sophisticated America. When Pablo Casals and Igor Stravinsky were fêted at the Kennedy White House, Bernstein was there. He also socialized with Jack and Jackie. He saw Kennedy’s New Frontier as a beacon light for an American artistic future that could stand up to Old World traditions.

Here’s a Bernstein anecdote: In 1959, when the State Department sent him to Soviet Russia with his New York musicians, Bernstein was counselled by a Russian bureaucrat not to perform Charles Ives’ The Unanswered Question. According to an eyewitness, Bernstein arose, said “Fuck you!”, and left the room. He proudly performed (and encored) the Ives piece, introducing Russian audiences to an American musical genius. Fourteen years later, at the second Nixon inauguration, he mounted an anti-Vietnam concert at the same moment the president hosted the Philadelphia Orchestra in a program including Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture (with cannon blasts). Bernstein chose Haydn’s pacifist Mass in Time of War, performed to an overflow audience at the National Cathedral. He was a man who seized center stage fearlessly and effortlessly.

Neither Kennedy nor Bernstein could have envisioned the arts initiative transpiring in D.C. right now: the apparent redirection of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the presidential plan for an NEH-funded Garden of Heroes, and the performance of the Star-Spangled Banner at all 2025-26 National Symphony concerts. Meanwhile, the president has purged the Kennedy Center board and made himself chairman. And he’s replaced the Center’s president with Richard Grenell, once a controversial ambassador, and now engaged in re-targeting arts programing “for the masses.” Among other things, Grenell has reportedly mandated a “break-even policy” for every performance. In arts administration, this is a formula bound to kill inspiration.

Most recently, Trump’s “Vision for a Golden Age in Arts and Culture” included the flagship Kennedy Center Honors: lifetime achievements awards begun in 1978. This time, they were hosted (as never before) by the president himself. The honorees, chosen with Trump’s “98%” involvement, were actor Sylvester Stallone, disco singer Gloria Gaynor, country musician George Strait, Phantom of the Opera star Michael Crawford, and the rock band Kiss—“among the greatest artists … ever to walk the face of the earth,” Trump said. Whatever one makes of that claim, previous honorees, starting in 1978 and 1979—George Balanchine, Marian Anderson, Fred Astaire, Richard Rodgers, Aaron Copland, Ella Fitzgerald, Martha Graham, and Tennessee Williams—have contributed more to an American lineage of creativity, today imperiled as never before by the erosion of cultural memory. And all this at a time when the major national charitable foundations have pulled arts funding in favor of social justice programs, and when affluent Americans are no longer as predisposed as their parents were to underwrite orchestras and museums.

So it is pertinent to ask: What might Goodwin have accomplished? And how might Bernstein have responded, were he alive today? Certainly the New Frontier would have elevated the arts as an American priority. Kennedy himself, ever the Cold Warrior, opposed direct government arts grants in favor of “free artists” thriving in “free societies”—a naïve view. But the arts endowment was already in sight. And the First Lady was an avid Russophile. Her initial guest at the White House was Balanchine, a supreme product of St. Petersburg and Paris. She sought advice on how she could help. Balanchine urged that she become America’s “spiritual savior.”

As for Bernstein—when Jackie Kennedy invited him to take over artistic direction of the Kennedy Center, he refused, but agreed to compose something for the Center’s opening concert in 1971. This turned out to be an anti-war Mass protesting the Vietnam War. It is virtually impossible to imagine him, during the decades of Vietnam and Watergate, agreeing to lead an imposed performance of the national anthem. He would have protested—prominently, loudly—the dismantling of the endowments. When in 1977 he was invited to testify in favor of a White House Conference on the Arts, he instead urged the House Subcommittee on Select Education to prioritize musical literacy: “I am sad to say, we are still an uncultured nation and no amount of granting or funding is ever going to change that” unless “reading and understanding of music be taught to our children from the very beginning of their school life.” (It also bears remembering that in Israel—a country long dear to him—Bernstein aligned himself with Teddy Kollek and other advocates of Israeli/Arab co-existence, and worried about Jewish sectarianism.)

Memorializing her husband with—significantly—an arts initiative, Jackie Kennedy envisioned a D.C. performing arts complex of international stature. Though Trump’s complaints about woke excess are by no means unfounded, the Kennedy Center has never seemed more provincial than today.

Since this nation’s founding, some have pondered whether democracy and the arts—and also whether capitalism and the arts—are somehow inimical. Certainly there is an impressive lineage of writings analyzing an American aversion to artists and intellectuals. Alexis de Tocqueville, nearly two centuries ago, observed among the citizens of the United States “a distaste for all that is old.” Assessing an expanded “circle of readers,” he discerned “a taste for the useful over the love of the beautiful,” for the “mass produced and mediocre.” Many decades later, American politicians of note included no John Adams or Thomas Jefferson—cosmopolites of humbling intellectual attainment. In 1962, the historian Richard Hofstadter produced a Pulitzer Prize-winning study of Anti-Intellectualism in American Life. He adduced a New World stereotype that holds the “genius” to be lazy, undisciplined, neurotic, imprudent, and awkward. He blamed democratization, utilitarianism, and evangelical Protestantism. An enduring philosophical argument against the American arts was launched in the 1930s by Theodor Adorno and the Frankfurt School: capitalism embraced a mistaken notion of the artist as a distant actor, unfettered and autonomous. The very DNA of American democracy—its notion of “freedom”—was in the Frankfurt view a misguided myth.

The misgivings inherent to these critiques foresaw that the American arts would suffer neglect. Neither Tocqueville nor Hofstadter nor Adorno, however, envisioned a vigorous White House initiative that would deploy the arts as an ideological cudgel. Concomitantly, a pugnacious pseudo-history stressing white Christian roots does no more favors for the arts than its woke equivalent; both pollute a necessary seedbed for creative expression. The American past is short, fragile, controversial—and precious. Today’s arts debacle is the least noticed, least discussed, least understood American crisis.

That the arts are a necessary source of national identity became the nub of Leonard Bernstein’s American vocation—until he lost faith and decamped to Vienna. It was equally understood by John Fitzgerald Kennedy. Never have Kennedy’s words sounded timelier:

“I look forward to a great future for America, a future in which our country will match its military strength with our moral restraint, its wealth with our wisdom, its power with our purpose. I look forward to an America which will not be afraid of grace and beauty, which will protect the beauty of our natural environment … And I look forward to an America which commands respect throughout the world not only for its strength but for its civilization as well.”

I explore the topic of JFK and the arts in detail in my book “The Propaganda of Freedom: JFK, Shostakovich, Stravinsky, and the Cold War.”

December 5, 2025

“Never before has the perseverance of historical memory been more inspirational — or more necessary”

The South Dakota Symphony Lakota Music Project on October 17, 2025 ,in Wagner, South Dakota. (Photo by Dave Eggen/Inertia)

The South Dakota Symphony Lakota Music Project on October 17, 2025 ,in Wagner, South Dakota. (Photo by Dave Eggen/Inertia)Following up on my NPR story about the Lakota Music Project, I write today for “Persuasion” online:

In South Dakota, Bishop Scott Bullock of Rapid City wrote [of Pete Hegseth’s insistence on the heroism of American soldiers who slaughtered Lakotas at Wounded Knee in 1890]: “If we deny our part in history we deepen the harm. We cannot lie about the past without perpetuating injustice and moral blindness. We acknowledge the government’s intent to honor its troops, yet we reject any narrative that erases the humanity of the victims or glorifies acts of violence.”

The ongoing discourse on Native America is ultimately a discourse about origins. What Lakota origins may have to do with American origins will remain a necessary puzzle demanding diligent attention. Not a puzzle is the Lakota preservation of a cultural inheritance at various moments threatened, distorted, or denied.

Never before in American history has the perseverance of cultural and historical memory been more inspirational — or more necessary.

To read the whole piece, click here.

To hear the NPR show, click here .

December 4, 2025

Cho Plays Rachmaninoff — An Astonishing Paganini Rhapsody

I distinctly remember when I discovered that Rachmaninoff was a great composer. It happened decades ago, when twentieth century music meant Stravinsky and Schoenberg. I was driving and the Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini came up on the radio. The piece was hardly new to me, but I had never paid much attention. This music has all the Stravinsky virtues, I thought: concision, originality, wit. And yet the range of color and feeling is more expansive. And – as almost never in Stravinsky – the inspiration never sags. As I have subsequently discovered, it also wears well. It’s a twentieth century masterpiece.

Rachmaninoff himself regarded Benno Moiseiwitsch as the supreme interpreter of his Rhapsody. And Moisewitsch’s 1938 recording, notwithstanding a scrappy accompaniment by the London Philharmonic under Basil Cameron, remains magical. This pianist’s distinctive touch is soft, subtle, lucid. His elegance and sophistication are bewitching. But the recording’s coup is the Rhapsody’s most famous moment (start at 13:30): the transition from the Hades darkness of the seventeenth variation to the healing D-flat major of variation eighteen. Independently savoring every melodic strand, Moiseiwitsch navigates the immortal tune toward its climax – and then, unforgettably, inverts the intended dynamic swell and drops to pianissimo. Never in recorded history was a piano more beautifully played.

Rachmaninoff’s own premiere recording, four years earlier with Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra, is notably different: heavier, more heroic, sometimes acerbic, rigorously unsentimental. No other pianist in my experience attains a comparable gravitas in this music.

Wednesday night at Carnegie Hall, Seong-Jin Cho assayed the Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini in collaboration with Manfred Honeck and the Pittsburgh Symphony. Born and raised in Korea, now 31 years old, he is perhaps the most knowingly acclaimed pianist of his generation. I was hearing him in live performance for the first time. What first impresses is the keenness and subtlety of his ear: his precise calibration of voicing and tone, of pedaling and dynamics. Pummeling the keys at full throttle, sustaining a rapt quietude at the softest possible volume, his poise remains imperturbable. In comparison to the recordings of Moiseiwitsch or Rachmaninoff, Cho was super-fast in the faster variations. Perhaps something was lost in clarity of articulation (I was sitting downstairs, where the sound swims). But because Cho never seemed rushed or pressed, the thrill of the chase prevailed. The lyric variations were breathtaking.

In a series of recent blogs, I’ve found myself pondering the rapid disappearance from the keyboard world of “national” schools of interpretation. To my ears, Jean-Efflam Bavouzet’s Ravel thrives on “French” clarity of rhythm and articulation, enforced with aesthetic rigor. Sergei Babayan’s heroic sonorities and sweeping rubatos sustain a “Russian” school. Yunchan Lim – a 21-year-old Korean already as famous as Cho – also goes his own way with poetic sincerity. But his new recording of Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons is a mistake – these are pieces, it seems to me, that need to sound “Russian” in order to cast a spell.

Cho’s Rach/Pag is original, not remotely “Russian.” But I find that I do not care: even juxtaposing Moiseiwitsch and Rachmaninoff, it’s evident that the Paganini Rhapsody (composed in 1934, by which time Rachmaninoff had long been abroad and even absorbed a whiff of American jazz) invites a range of approaches. Crucially, Wednesday’s performance was deeply collaborative. Cho’s sonic imagination, his quicksilver range of color and sensibility, his affinity for stillness on the verge of silence, were acutely partnered by Honeck and his players.

The concert closed with Shostakovich’s Fifth. This 1937 symphony, composed in a spirit of repentance, is often regarded as a kind of cop-out. Re-encountering it for the first time in years, I have to agree. It’s tighter and simpler than the sprawling Shostakovich of Nos. 4, 7, 8, and 10 – and less enveloping. Its most remarkable feature – also its most controversial – is a slow-motion stentorian ending. An unforgettable description, by the composer himself (in Solomon Volkov’s Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich), likens these final pounding measures to “forced rejoicing.” To fully register in performance, they demand a bleak machine intensity from the violins, itself predicated on a condition of hyper-commitment that I do not associate with today’s American orchestras. For hyper-commitment, listen to old broadcasts by Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony (try their Francesca da Rimini), or Dmitri Mitropoulos in Minneapolis or New York, or Toscanini with his NBC Symphony, or the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra under Ettore Panizza and Artur Bodanzky. The most astounding orchestra I ever encountered in live performance was Evgeny Mravinsky’s Leningrad Philharmonic when it toured the US in 1962. I missed the program with Shostakovich’s Eighth – but I’m sure it was the real deal. Today’s Berlin Philharmonic has a first violin section that looks and sounds like a congregation of concertmasters. That’s what can clinch Shostakovich’s Fifth. Otherwise, Honeck and his Pittsburgh players were formidable. They have forged a unity. Their purposes, moment to moment, are never in doubt. In my experience, no other American orchestra regularly enjoys the services of a conductor as gifted in the standard repertoire.

A cavil: the concert began with a New York premiere: Lera Auerbach’s Frozen Dreams, 12 minutes long. That is: it hewed to a tired template: a token new work, then furniture moving, then a concerto, intermission, and a symphony. The first half might have begun with the piano already onstage, and Rachmaninoff’s Vocalise as a magical prelude to the Rhapsody.

P.S. – Seong-Jin Cho returns to Carnegie for a solo recital on April 12. His program is nothing if not original:

Bach B-flat Partita

Schoenberg: Suite, Op. 25

Schumann: Faschingsschwank aus Wien

Chopin: Waltzes (complete)

For a related blog about Yunchan Lim, click here .

About Sergei Babayan, here

About Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, here

About Yuja Wang, here

About Rachmaninoff – use this blog’s finding aid. I am still recuperating from modernist caricatures of a great composer who was also a great man.

Joseph Horowitz's Blog

- Joseph Horowitz's profile

- 17 followers