Joseph Horowitz's Blog

November 23, 2025

Happy Hundredth Birthday to Gunther Schuller (1925-2015)

On November 22, Gunther Schuller would have been 100 years old. It was my pleasure to contribute an encomium to the new Gunther Schuller Festschrift:

I am privileged to have known three sui generis American musicians of Gunther Schuller’s generation. All three both composed and performed. It was always my opinion, my frustration, that they were not sufficiently esteemed and utilized. They could have contributed more had American classical music been less provincially attuned to European pedigrees.

One was Lukas Foss, who was my Conductor Laureate when I ran the Brooklyn Philharmonic in the 1990s. Previously, during my brief tenure as a New York Times music critic, it was I – because so low on the totem pole — who was assigned to review Lukas’s Brooklyn Philharmonic concerts at BAM. They towered over the performances being given by Zubin Mehta and the New York Philharmonic across the river. As was equally little-known, Lukas was also one of the pre-eminent American pianists of his generation. And his crazy compositions always worked so long as he participated in their performance.

Lukas would have made a bracing successor to his friend Leonard Bernstein when Bernstein resigned from the Philharmonic. In fact, as a darkhorse candidate, he was entrusted with a full month of New York Philharmonic subscription concerts in 1966. One of his soloists was Leon Kirchner, in Mozart’s C minor Piano Concerto. I met Leon at the 92nd Street Y in the 1980s. He partnered Jaime Laredo in Mozart’s E minor Violin Sonata – the most heedlessly expressive Mozart playing I have ever heard. And he conducted Schoenberg’s First Chamber Symphony. After that revelatory performance, which treated the music as an old friend, the participating clarinetist told me: “I wish I’d had that experience before I recorded the Schoenberg Chamber Symphony with Orpheus.” Late in his life, Leon moved to the Upper West Side. He would regale me with his impressive Boston recordings, conducting Schoenberg and Sessions. One of the last times I saw him he was being visited by Carl Reiner, whom he knew from his days in Los Angeles studying composition with Schoenberg. (Reiner didn’t remember his stellar performance in one of my favorite “Show of Shows” sketches, lampooning Ted Mack’s “Amateur Hour.”)

Gunther is of course the third sui generis musician on my list. He commanded the widest and most complete knowledge of American music of anyone I ever encountered. Decades before the internet and AI, I would ply him with questions over the phone. His answering voice invariably sounded careworn and fatigued – it meant nothing; he was always eager to talk. When writing Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall, I needed to quickly acquire reliable impressions of all the conductors he had experienced in his horn-playing days. He especially loved to recall Dimitri Mitropoulos – how Mitropoulos’s eyes would cross when his intensity peaked; how (contradicting conventional wisdom) the New York Philharmonic’s standards of performance declined during the early Bernstein years, post-Mitropoulos. (These impressions, and so many others, may be found in Gunther’s autobiography.) When I tried querying him about Fritz Reiner and George Szell, he told me to do some homework. I phoned back in a week or two to report that I had been listening to broadcasts and enjoyed Reiner but not Szell. Gunther shot back: “Attaboy!”

Twice I was able to engage Gunter to conduct. The first occasion was a 1995 Brooklyn Philharmonic weekend I called “From Gospel to Gershwin.” This was an excavation of Black classical music long before it became fashionable. Gunther was apparently so little accustomed to being invited to guest-conduct that when I phoned him he was at first incredulous. I explained that I wished to entrust him with a pair of subscription concerts plus an additional Sunday afternoon “Interplay” at the BAM Playhouse (since converted into a movie theater). On the main program, I intended to situate Robert Russell Bennett’s Porgy and Bess Suite on part two. And I had engaged the Morgan State University chorus to participate in that, and also to open the second half with a cappella spirituals. Part one was a blank slate upon which Gunther inscribed Scott Joplin’s Treemonisha Overture, James P. Johnson’s Yamekraw (as reconstructed by Gunther Schuller), and William Grant Still’s Sunday Symphony (in Gunther’s opinion, the strongest of Still’s five symphonies, all of which he had perused).

For the Interplay I had engaged Steve Mayer to do an Art Tatum set and needed a second act. Gunther chose to disassemble Duke Ellington’s Reminiscing in Tempo and put it back together again. He arrived with a set of parts, a set of excerpts, and did precisely that. His program note read in part:

“Reminiscing is one of the most successful of Ellington’s extended works, not only for its time but even as measured retrospectively against his numerous other major creative efforts through the years. Reminiscing was innovative not only in its duration – some thirteen-minutes stretched across four 10-inch sides – but in the way its several themes and episodes were integrated in to a single unified whole. Nothing quite that challenging had ever been attempted in jazz composition – and with a jazz orchestra.”

The weekend’s other participants included the music historian Carol Oja and the literary historian Robert O’Meally (on the Harlem Renaissance). It linked to a conference at Brooklyn College. I dedicated it all to Gunther’s “Seventieth Birthday Season” and we had a birthday party with a proper cake. I mention all this because nothing comparable seems remotely conceivable today – I enjoyed a BAM audience that was ready and willing. Also, because I felt it was the least I could do to honor Gunther.

Nine years later, in 2004, Bob Freeman invited me to curate a Dvorak/America festival at the University of Texas’s Butler School of Music. This was a considerable undertaking, lasting fifteen days and including major scholars. The centerpiece was to be an orchestral program beginning with George Chadwick’s terrific Jubilee (1895), which has always sounded to me like his version of Dvorak’s Carnival Overture (and Chadwick was unquestionably influenced by Dvorak). A faculty cellist would do the Dvorak concerto. The third work – the main event – would be Frederic Delius’s Appalachia: Variations on an Old Slave Song (1896-1903): a fascinating 40-minute New World symphony for orchestra, baritone and chorus, with a “slave song” composed by Delius himself. But the conductor of the Butler School orchestra wished to replace the Delius with Debussy’s La Mer – a suggestion that a wag in Freeman’s office dubbed “Dvorak at Sea.” Miraculously, the conductor resigned – and Bob and I needed a quick replacement. It was agreed that I would contact Gunther.

I was in the midst of explaining all of this to Gunther, over the phone, when I got to the part about Appalachia and the Butler conductor’s refusal to conduct it. Gunther interrupted:

“WHAT AN IDIOT!!!”

– and proceeded to inform me that all his life he had wanted to conduct Appalachia, that he regarded Delius and Scriabin as the two composers who had most ingeniously devised a post-Wagnerian chromatic tonal language of their own.

We added to the program “Lasst mich allein” – the Dvorak song cited in the Cello Concerto, where it ultimately bids farewell to Dvorak’s beloved sister-in-law Josefina. There were two performances, the second being a run-out at the Round Top Festival. At the Austin performance I happened to be sitting directly behind the late Richard Crawford, then the central historian of the American musical experience. Richard had never before heard a live performance of Jubilee. He listened, beginning to end, literally on the edge of his seat. And Gunther revisited this work – as Leon had the Schoenberg — as an old friend. It was the most persuasive performance of Jubilee I will ever hear.

Not long after I returned to New York City, I received in the mail a bulging envelope from Gunther. It contained a handwritten letter eight pages long, plus an annotated score of the Dvorak concerto. As the letter was marked CONFIDENTIAL, I feel constrained to quote it at any length. Gunther’s gist was that the “distortions” inflicted on Dvorak’s Cello Concerto by his Texas soloist were so upsetting that he felt impelled to document in full what he had endured. Here’s an excerpt:

M. 120: first two beats very slow, following by a 1 ½ bar accel., then in mm. 122/3 even faster accelerations. . . . m. 128-131, big slow down (to about quarter note = 72, instead of Dvorak’s 116). M. 140, not pp, but a big fat f. M. 142 a big accel, m. 143 a big ritard. M. 147 I had to make a huge rit. so that his super-slow m. 148 made some kind of logical sense. M. 154-5 a huge accel. (the cellos and basses never could catch up with me and him).

There was also a P.S.: “Not any other cellists pay much attention to Dvorak’s score and meticulous notation. I think it was Rostropovich who first led everyone down the primrose path.”

I most recently had occasion to remember Gunther when I accompanied the University of Michigan Symphony Orchestra, and its terrific conductor Ken Kiesler, to South Africa. Recounting this experience in The American Scholar, I wrote in part:

“In 1979, the composer-pedagogue Gunther Schuller . . . delivered a rather famous lecture at the Tanglewood Music Center. He warned the students, most of them fledgling symphonic musicians, that American orchestras had fallen prey to apathy, cynicism, and bitterness. He said boredom was rife in the ranks of the most affluent, most prestigious orchestras. He complained of a ‘union mentality’ and ‘absentee’ music directors. The University of Michigan players I observed in South Africa comprised one of the least jaded orchestras I have encountered in years. They retained attention even when they were not playing. They drew mounting energy from the audiences in Pretoria, Johannesburg, Soweto, and Cape Town. I heard one violinist, at Soweto, impulsively declare that she did not want to return to the United States, that the concert had been ‘life-changing.’”

The emotion behind Gunther’s “rather famous Tanglewood lecture” can only be adequately appreciated if one happens to listen to broadcasts of Mitropoulos’s New York Philharmonic, in which Gunther subbed.[1] The intensity of commitment isn’t just a function of podium leadership. It evinces a tireless passion for music.

Gunther loved the Dvorak Cello Concerto so much that he literally had to expel the memory of that Texas performance.

[1] To sample Mitropoulos’s Philharmonic at full throttle, try their January 29, 1950, broadcast of Rachmaninoff’s Symphonic Dances – and ask yourself when you last heard a professional American orchestra play with such abandon.

November 18, 2025

Maurice Ravel, Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, and the Vanishing Authority of French Pianism

In Western classical music, the iconic composers disappeared sometime midway through the twentieth century, with Dmitri Shostakovich the final contributor to the symphonic canon. Such things happen. But a plethora of inspired interpreters – conductors, singers, instrumentalists – played and sang on, sustaining the lineage of composers Russian, German, Italian, and French. When I began attending concerts in the 1950s, the supply seemed inexhaustible.

No longer. Today’s important young pianists, however sensitive and sincere, may evince no performance tradition whatsoever. And that can work, too. (In a recent blog, I explored the consequences when Yunchan Lim broaches Tchaikovsky without attempting to sound “Russian.”) That said, to encounter a ripe exponent of the Russian piano school nowadays is an event – and so it was when I’ve experienced Sergei Babayan performing Rachmaninoff (cf a couple of blogs here and here).

Which brings me to Jean-Efflam Bavouzet’s triumphant traversal of the complete solo piano works of Ravel – a mega-program he’s widely touring, and which arrived at New York City’s Tully Hall earlier this evening. Bavouzet is a supreme embodiment of a keyboard species perhaps nearly extinct: the French Pianist. His attributes align with the French language: tactile articulation, precise rhythm, clarity of texture. French pianism can seem a cerebral acquired taste. But for Bavouzet, it’s memorably empowering. He excels in Haydn (has recorded the complete sonatas). He adores Bartok. He knows jazz. He has ventured into Boulez. His Ravel sounds right to me.

Here is a composer mired in paradox and enigma. Ravel the man will forever remain a mystery. His musical aesthetic combines classicism with a heady aroma of evanescence. One result is an omnipresent patina of sadness. Though himself a pianist of limited technical ability, he expanded the instrument’s sonic possibilities with clairvoyant assurance.

Bavouzet’s mega-program (with two intermissions) chronologically tracks a subtle evolution of style and sentiment. Early on, in the Sonatine (1903-05), Bavouzet discovered in the coda to the minuet a moment of sublime levitation forecasting the composer to come. In Scarbo (1908), every virtuoso’s Ravel test piece, he calibrated the elemental surge with miraculous precision. In the Menuet from Le Tombeau de Couperin (1914-1917), Ravel’s sadness – now resonating with the horror of the Great War — is intensified by acrid harmonies and austere textures. Bavouzet rose to the occasion with harrowing intensity, then finished off the printed program with a blazing rendition of the ensuing Toccata.

***

I first met Jean-Efflam Bavouzet at the 1989 Van Cliburn Competition, about which I wrote a book: The Ivory Trade (1990). Disregarding the jury, I picked my own favorites – including Bavouzet, who failed to make the final round. I wrote: “Of four renditions of Prokofiev’s curt, violent Third Sonata, Jean-Efflam Bavouzet’s is on every level the most gripping. The Allegro tempestoso main material is both superpowered and precisely sardonic; the bittersweet moderato second subject is the most poignant for remaining taut. In two movements from Schumann’s F minor Sonata, Bavouzet confirms what his phase-one Schumann Toccata intimated: if his crystalline sonority is not conducive to an idiomatic tenderness, he conveys this composer’s psychological instability with unusual authority, and also a paradoxical Gallic poise. His playing is mercurial and elegant, forceful and specific. . . . In conversation, Bavouzet evokes the actor Jean-Pierre Leaud. He is small, pale, and fine-featured; clever, quick, and sincere. The main surprise is his eyes, which are huge and lucid under high, dancing eyebrows. A shock of black hair [today white] falls over his forehead, a la Napoleon. He can juggle and imitate the sounds of cars. He knows about miniature trains. . . . He has chosen the astringent Bartok Second as one of his concertos – even though he has never performed it. . . . ‘I know it is a completely crazy idea for a competition. But I thought: The day I will play it will be one of the best days of my life.’”

I also wrote, in my Introduction: “At the Cliburn competition Jean-Efflam Bavouzet was my Ping-Pong partner. Rather than attempting to neutralize this intervention, I let him win a few games just before the chamber music round, in which he excelled” – a claim he vividly recalls and disputes (also vividly).

Over the years, I have enjoyed the privilege of playing piano duets with Jean-Efflam – and experiencing first-hand his dismissal of music he does not find “musical.” His musical discoveries, however, are tidal. When I introduced him to Schubert’s Lebensturme – for me, the summit of the entire four-hand literature – his incredulous delight at the unlikely modulations ensnaring the recapitulation impelled him to insist that we play this passage again. And again. And again. And again. And again.

Jean-Efflam’s joy in performance includes flamboyant verbal sallies. Had his Ravel program been a little shorter, he surely would have succumbed to the temptation of sharing with the audience his exasperation at Ravel’s instruction espressiv. And yet Ravel is ever the classicist. “How much espressiv???” he exclaims. “Should I slow down? Should I use rubato?” (An act: he knows the answers.)

I once had occasion to accompany him to a recital at the 92nd Street Y by my great friend, now deceased, Alexander Toradze. Jean-Efflam could barely endure Lexo’s heroically expansive rendition of Gaspard de la nuit. But his encore – Oiseaux triste from Miroirs – was simply too much. “I cannot recognize this piece!!!” Bavouzet exclaimed. Loudly. And he actually meant it.

At Tully Hall Tuesday night, the happiest person in the room, following a searing encore rendition of La valse, was Jean-Efflam himself, beaming pleasure, parading across the lip of the stage. It had to be the piano event of the season.

October 30, 2025

“Parsifal” Then and Now — A DEI Blitz

Amfortas raises the Grail Cup (act one, scene two). Photo by Cory Weaver/San Francisco Opera

Amfortas raises the Grail Cup (act one, scene two). Photo by Cory Weaver/San Francisco OperaSo protean are the operas of Richard Wagner that they mirror not merely their own time and place – Germany of the Romantic era – but their time and place of performance. In Hitler’s Germany, they embodied creeds of national and racial supremacy. In fin-de-siecle America, they excited melioristic fervor. During this trans-Atlantic heyday of Wagnerism, peaking in the 1880s and 1890s, the enthralled Wagnerites of New York City were not patriots or anti-Semites, decadents or proto-modernists; they preached or practiced uplift. Parsifal, accordingly, acquired supreme status in the Wagner canon. It registered as a religious drama invoking Christian iconography. Its obsession with race – with purity of blood – passed unnoticed.

Two recent Parsifal manifestations sharply focus the subsequent American history of this valedictory opus – not a grand opera or music drama, but a “sacred festival play” which summarizes and complicates Wagner’s artistic legacy in equal measure. The first is the appearance, on four CDs, of a legendary Metropolitan Opera Parsifal broadcast: the Good Friday matinee of April 15, 1938. The other is a new Parsifal production at the San Francisco Opera. The 1938 Met broadcast was previously only available in wretched sound; the new restoration, by Ward Marston (who specializes in scrubbing old recordings), may be the Wagner event of the year. It documents in full the role of Parsifal as sung by the supreme Wagner tenor of his generation: Lauritz Melchior. It also happens, not so incidentally, to include the participation of no fewer than five Jewish artists. If the Met Parsifal documents wartime intensity and displacement, the San Francisco Parsifal (October 25 to November 13) equally betokens today. Its obtrusive emphasis on diversity, equity, and inclusivity mangles the opera’s central sermon: that only innocence breeds true compassion.

The Met’s Wagner lineage is long and august. Four successive Wagner conductors of high consequence presided: Anton Seidl (who arrived in 1885 as Wagner’s onetime protégé and surrogate son), Gustav Mahler (who quit the Vienna Opera for New York), Arturo Toscanini (who pushed Mahler aside in 1908 and stayed through 1915), and Artur Bodanzky (who died one year after the 1938 Parsifal now restored). If the company’s stagings were often indifferent, its international casts were at all times stellar. Considered musically, the Met could credibly be called the world’s leading Wagner house for fully half a century. It is a claim difficult to absorb because Bodanzky is today little remembered – and because the enveloping intensity of engagement driving Bodanzky’s Wagner broadcasts quickly became a thing of the past. If recalled at all, he is notorious for brisk tempos and bulky abridgements (undertaken in consideration of an audience that mainly spoke no German).

But Bodanzky’s 1938 Parsifal is neither fast nor trimmed . The Prelude – this opera’s keynote, emanating from existential darkness to predict a vast trajectory of quest and redemption – is exceptionally slow. Its sustained gravitas is humbling. The entirety of the first act, lasting 107 minutes, is so raptly focused that the curtain falls in silence: there are no applause. Even more remarkable is act three, a reading of awesome weight and breadth, in which Wagner’s “Good Friday Spell” transfigures a mythic forest on Easter Sunday morning. Parsifal is here a holy fool returned from wandering the world. He brings with him the Speer that once wounded Christ on the cross. Empowered by compassion, he redeems the brotherhood of knights who safeguard a second holy relic: the Grail Cup from which Christ drank at the Last Supper.

As the protagonist in this drama, Melchior is sui generis, his tenor fresh and true, heroic and intimate, a bearer of clarion proclamations and whispered intimacies, a purveyor of words and thoughts. The swelling refulgence of his final invitation — “öffnet den Shrein!” — is itself a vocal miracle. He is partnered by Emanuel List as Gurnemanz, Friedrich Schorr as Amfortas, and Arnold Gabor as Klingsor. That all three, and also Bodanzky, were Jews born abroad is not irrelevant. Three of the roles they here enact are studies in displacement by the composer who most complexly understood the outsider: Klingsor, who has castrated himself to cancel erotic desire; Amfortas, whose bleeding wound Klingsor inflicted when he stole the Holy Speer; Parsifal, who knows nothing of his history, not even his name. Most remarkably, the opera’s sole female participant, Kundry, alternates between polar extremes of estrangement: when not deferentially tending the knights, she becomes a whore beholden to Klingsor’s power mania. Willa Cather, a devoted Wagnerite, unforgettably called Kundry “a summary of the history of womankind. [Wagner] sees in her an instrument of temptation, of salvation, and of service; but always an instrument, a thing driven and employed. . . . She cannot possibly be at peace with herself. . . . A driven creature, [she is] made for purposes eternally contradictory.” The inspiration for this characterization was the soprano Olive Fremstad, the Callas of her day, and a personal acquaintance of Cather’s. In the 1938 Met performance, the role of Kundry is lost on Kirsten Flagstad, who better knows Brunnhilde and Isolde.

In 1938, Wagner at the Met dominated the repertoire. No orchestra abroad possessed a more potent Wagner lineage. Absorbing the robust exaltation of the playing, one is amazed by the sheer expenditure of energy sustaining these four- and five-hour dramas. It would be simplistic merely to credit Bodanzky and his predecessors with powers of inspiration they doubtless possessed, or to cite the galvanizing singers with whom the players interact (in Parsifal, the effortless precision with which everyone breathes together, even in passages of great deliberation, constitutes a master class in Wagner interpretation). Simply put: the works are known and loved. They are felt.

And Parsifal maintained a special place. Jeffery McMillan, in the copious booklet inserted in Marston’s Parsifal CD box, recounts a four-decade history of Good Friday Parsifal matinees at the Met beginning in 1907. Following the practice at Wagner’s Bayreuth Festival, applause and curtain calls were forbidden following the first and third acts. In a recent blog post reviewing the Marston Parsifal, Conrad L. Osborne – an unsurpassed chronicler of operatic performance in New York City beginning in the 1950s – writes of his own experience of “those Good Friday [Parsifal] matinees, when the tradition was still in full force.”

“It was reverent and church-like, with the attention and obedient patience of the true believers setting (indeed, enforcing) the tone for everyone, even the skeptical and bewildered—exactly as at a service. . . . That was a uniquely intense experience, magnified in Act 3 by the awareness that Good Friday reigned both inside and outside the theatre. Mostly inside, though, and the intensity was followed by a matchingly celebrative sense of relief and release upon discharge into the relatively fresh air and late-afternoon light of West 40th Street, with its oblivious semi-holiday passersby and lazy automotive traffic.”

The subsequent fate of Wagner at the Met is unwittingly documented, in the 1938 Parsifal broadcast, by a further Jewish participant arrived from abroad: the twenty-six-year-old Erich Leinsdorf. Bodanzky, increasingly infirm, relinquished his baton to Leinsdorf for act two, the shortest and most operatic of Parsifal’s three acts. In this cruel juxtaposition, Leinsdorf is no Bodanzky. The orchestra’s impassioned weight of utterance is lifted. The singers are sometimes rushed. The elemental groundswell is absent. When upon Bodanzky’s death in 1939 Edward Johnson, running the house, appointed Leinsdorf in his place, both Melchior and Flagstad threatened to quit. But Leinsdorf and Johnson prevailed. Ever after, the house’s Wagner tradition lapsed and thinned. Beginning in the 1980s, Speight Jenkins’ Seattle Opera eclipsed the Met as America’s premiere Wagner venue. More recently, the Met’s current Parsifal production, new in 2013, was briefly redemptive. Its salvation was not the cast or director, but a master conductor – Daniele Gatti. Remounted five years later under the baton of Yannick Nezet-Seguin, the production failed to ignite.

***

The San Francisco Opera was founded in 1923 – forty years after the Met. It enjoyed a Wagnerian heyday in the 1970s under Kurt Herbert Adler, an Austrian/American conductor and impresario who expanded the season to as many as 16 operas. For Wagner, Adler assembled the biggest names abroad, beginning with Birgit Nilsson. The orchestra was mediocre and at times under-rehearsed. In compensation, Adler landed a major conductor from East Germany: Otmar Suitner. The company was for many the city’s cultural crown jewel.

These days, the San Francisco Opera seems a shrunken remnant. The present season includes only six operas. Meanwhile, across the street, a San Francisco Symphony music director of high prestige, Esa-Pekka Salonen, in 2024 abruptly quit the orchestra when its board failed to back artistic initiatives he regarded as vital. The symphony’s current repertoire, reversing course, is startlingly provincial. The opera, in comparison, is by no means without ambition. Its new Parsifal comes on the heels of new Wagner productions – Lohengrin and Tristan und Isolde — the two seasons previous. The conductor of all three is the company’s music director since 2021: Eun Sun Kim. A Wagner Ring cycle is projected. In short: San Francisco is intent on taking Seattle’s relinquished place as a West Coast Wagner mecca.

Their Parsifal is self-evidently a labor of love. Kim’s interpretation is fluent and assiduously prepared. The orchestra of 77 players, while smallish for a 3,000-seat house, is superior to the Wagner orchestra Adler assembled. The chorus is sound. Of the principal singers, the Kundry – Tanja Ariane Baumgartner – is overmatched vocally and dramatically (most Kundrys are). Otherwise, the cast is shrewdly chosen. A pair of veteran Wagnerians – Kwangchui Youn and Falk Struckmann – sing Gurnemanz and Klingsor. Brandon Jovanovich’s tenor, more plangent than heroic, commands sufficient heft to clinch Parsifal’s climactic outbursts. Brian Mulligan is a lyric Amfortas. Though bigger voices – such as Melchior, List, Schorr, and Flagstad – could potentially have accommodated a reading of greater breadth and weight, the instruments at hand get the job done.

That these singers participate as believers is a credit to the director, Matthew Ozawa. But he concludes with a fatal faux pas. Wagner here furnishes an enraptured ending perfectly mated with sonic radiance: “A beam of light: the Grail glows at its brightest. . . . Kundry slowly sinks lifeless to the ground in front of Parsifal, her eyes uplifted to him. Amfortas and Gurnemanz kneel in homage to Parsifal, who waves the Grail in blessing over the worshipful brotherhood of knights.” Ozawa not only cancels Kundry’s death – she partners Parsifal’s possession of the cup. The result resembles a prosaic marriage tableau.

A greater miscalculation is the engagement of a prominent choreographer, Rena Butler, to add dancers. When in 2019 the Met brought a new production of Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess from London to New York, someone noticed that a Black cast had been entrusted to a white director and white conductor. And so a Black choreographer, Camile A. Brown, was added to the show along with her company of African-American dancers. Their presence proved wholly superfluous and mildly obtrusive. In Parsifal, Butler’s dancers are wholly obtrusive. The first, introduced in act one, impersonates Parsifal’s mother Herzeleide. When in act two Wagner strategically leaves Parsifal and Kundry alone on stage, the addition of Herzeleide as a mimed presence vitiates the opera’s pivotal confrontation. Klingsor’s Flower Maidens, who have just been banished from the premises, in Butler’s rendering include men as well as women. And she repeatedly foregrounds a trio of red-clad dancers, two women and a man. When Klingsor hurls the Spear at Parsifal, it is they who guide its trajectory. When Amfortas raises the cup to end act one, the dancers interpose their gyrations. In the program book, Butler explains that she has drawn inspiration from “the restrained, poetic gestures of Noh, the visceral, soul-searching impulses of Butoh,” and the “ritual gestures found in Christianity . . . When these traditions intersect, they create an eclectic and abstract movement vocabulary that seeks to bridge the human and the divine. . . . The choreography invites audiences to experience Parsifal as a collective ritual — immersed in wonder, reverence, and the possibility of transcendence.” I’m not sure Wagner requires any help in this department. Butler also has a supplemental agenda: genderless choreography. I cannot, however, think of an opera more intent on exploring gender disparities than Parsifal, with its celibate Knights, castrated villain, and Ur-feminine protagonist/antagonist “summarizing womankind.” So extrinsic are Butler’s dancers that their removal would leave no holes. It is only the corrupting ideological moment at hand that makes them seem essential.

Though elderly, San Francisco’s Parsifal audience is robust and rapt, including (according to the company) a substantial proportion of newcomers. And subscriptions are up. Jovanovich, in the program book, testifies that singing Parsifal makes him feel “a better person.” I am sure many in the house felt similarly.

Wagner endures.

RELATED BLOGS:

Celebrating Artur Bodanzky ‘s Wagner broadcasts: click here.

The San Francisco Symphony loses Esa-Pekka Salonen: click here and here.

Daniele Gatti conducts a magnificent “Parsifal” at the Met (2013): click here for my Times Literary Supplement review.

Yannick Nezet-Seguin takes over the Met “Parsifal” (2018): click here.

A superb Seattle Opera “Parsifal” (2003): click here (scroll down for my Times Literary Supplement review).

October 15, 2025

“Cheapening Freedom by Over-Praising It”

The journal H-Diplo Review, addressing scholars of diplomacy, foreign relations, and international history, has graciously published a little something I was invited to write about my 2023 book “The Propaganda of Freedom” in an attempt to foster cross-disciplinary inquiry:

As a cultural historian specializing in the history of American music, I have long been aware of disciplinary boundaries that can throttle understanding of the American experience. In part, I wrote The Propaganda of Freedom: JFK, Shostakovich, Stravinsky, and the Cultural Cold War to invite cross-disciplinary dialogue. My topic is a dysfunction in American diplomacy that has been widely overlooked, comparable in some ways to intelligence failures in, say, Cuba or Iraq when the wrong informants were trusted. I also discovered that the cultural aspirations of the Kennedy White House, though pertinent to the Cold War, had been little explored.

My book was born in 2013 when I happened to attend an event at the National Archives toasting the sophistication of the Kennedy White House. I learned that, when eloquently extolling culture as a civilizing influence, President John F. Kennedy would typically declare that only “free artists” in “free societies” could produce great art. I was stunned by this counter-factual assertion. And yet it was the ideological bedrock of the cultural Cold War as pursued by the US. I wanted to trace its origins and assess its impact on American policy.

The first task proved surprisingly simple – and surprising. Kennedy’s central iteration of the propaganda of freedom (at Amherst College on October 26, 1963 – by which time such Soviet artists as Andrei Tarkovsky, Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, and the late Boris Pasternak were widely hailed in the West) was scripted by Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. Schlesinger was influenced by his friend Nicolas Nabokov (as were George Kennan, Charles Bohlen, and other practitioners of Cold War foreign policy). A composer, Nabokov venerated Igor Stravinsky. Stravinsky’s decades in exile from his native Russia had resulted in a polemic denying that music “can express anything at all” and dismissing the pertinence of “inspiration.” It was his way of insisting that, as a “free artist” in Paris or Los Angeles, he did not need his roots in Mother Russia. Nabokov, also in exile from a Russian cultural homeland, suffered a trauma of displacement so severe that he insisted that Soviet Russia was a cultural wasteland and its most famous musician, Dmitri Shostakovich, a cipher and a stooge.

When Nabokov became general secretary of the CIA-funded Congress for Cultural Freedom, this preposterous opinion prevailed at the CIA, the White House, and the State Department. Because the most influential accounts of the CCF are framed by authors, e.g., Frances Stonor Saunders and Hugh Wilford, whose books demonstrate scant knowledge of music, the extremism of the propaganda of freedom as pursued by Nabokov has been insufficiently appreciated. Nabokov’s most lavish CCF festival, “Masterworks of the Twentieth Century” in Paris in 1952, was accordingly denounced by the French artists and intellectuals on the left that the CCF sought to court. Successful propaganda must be credible.

A vignette: In 1958 Van Cliburn won the Tchaikovsky International Piano Competition in Moscow. He became a hero to the Soviets – and not least to Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and his family, who invited him to their dacha. All America knew this story (but notd that the State Department refused to subsidize Cliburn’s expenses even though he could not pay his phone bills). The conductor of Cliburn’s competition performances was Kirill Kondrashin – among the most prominent Soviet musicians; upon defecting, he became conductor of the Concertgebouw Orchestra in Amsterdam. Cliburn was so impressed by Kondrashin that he brought him to the United States to conduct his concerto performances at Carnegie Hall and on tour. Cliburn and Kondrashin also recorded Tchaikovsky and Rachmaninoff in New York for RCA. Their recording of Tchaikovsky’s First Concerto became the first classical LP to sell more than one million copies. In 1964, Nabokov reported that he had never heard of Kirill Kondrashin, and that he was “little-known” outside the USSR. At the same time, Nabokov knew so little about American music, which he was charged to promote abroad, that he spelled Charles Ives’s last name “Yves.” Ives is arguably the supreme genius of American classical music.

A turning point was the Lacy-Zarubin Agreement of 1958. On the US side, it began by sending Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic to Moscow, Leningrad, and Kiev in 1959. Bernstein proved an exemplary cultural ambassador, not least because he obeyed no rules. When Soviet bureaucrats advised him not to program Ives, he exclaimed “f*ck you!” and left the room (this eyewitness vignette was imparted to me by the late Hans Tuch, who assisted Bernstein as an officer of the State Department). In the following years, cultural exchange with the Soviet Union superseded the tendentious tactics of the CCF. Rather than demonizing Soviet Russia, it preached mutual understanding. Nabokov, meanwhile, hysterically attempted to dissuade Stravinsky from visiting Moscow and Leningrad. Stravinsky did so in 1962, to triumphant acclaim. Nabokov himself finally journeyed to Soviet Russia five years later and discovered that composers he had vilified were absorbing and entertaining.

Processing this tale, I explore “survival strategies” pursued by Nabokov and Stravinsky, who were displaced in the US, and also by Shostakovich, who was both cherished and persecuted in the USSR. I suggest that Stravinsky, in residing in Hollywood, enjoyed a “freedom not to matter.” In a fascinating 1954 interview with Harrison Salisbury of the New York Times, Shostakovich volunteered his own notion that “the artist in Russia has more ‘freedom’ than the artist in the west.” The reason, Salisbury paraphrased, was “what might be described as a ‘principled’ relationship to society and to the party,” versus a “haphazard” relationship to society, as in Western nations. He is accorded “status” and “a defined role.” If a composer, his music is paid for, published, and performed. The Times saw fit to publish a “contrasting view” alongside Salisbury’s “Visit with Dmitri Shostakovich”: “Music in a Cage” by Julie Whitney, who proposed as a “very serious question” whether Soviet composers “might not use their talent more successfully if they were out of the ‘gilded’ cage in which Shostakovich declared they are so content.” Similarly, when Shostakovich visited the US in 1949, he was sagely advised to defect. Shostakovich’s tribulations in Stalin’s Russia were immense, but so was his self-identification as a “people’s artist” who bore witness for his countrymen. In retrospect, the cultural Cold War furnishes an inexhaustible exercise in mutual misunderstanding.

My book also more broadly contrasts classical music in the US and USSR. With regard to cultural exchange, the Russians took the first initiative, sending their leading instrumentalists to the US along with major Shostakovich compositions and an orchestra of bewildering accomplishment: Yevgeny Mravinsky’s Leningrad Philharmonic. This was not merely a foreign policy ploy: classical music mattered more to Soviet Russians than it did to Cold War Americans. Commensurately, I compare the interwar popularization of classical music in both countries. In the US, “music appreciation” was dominated by commercial interests. In Russia, where factories deployed orchestras, choirs, and even opera troupes, ideology dominated. Both approaches were potently pursued and potently flawed.

I conclude in part: “That so many fine minds could have cheapened freedom by over-praising it, turning it into a reductionist propaganda mantra, is one measure of the intellectual cost of the Cold War.” I also write that, though the US won the Cold War, the cultural Cold War “did not yield a victor.” My book’s final chapter ponders “culture and the state” yesterday and today. The vexed relationship between culture and democracy, even the elusive nature of democracy itself, have never been more pertinent.

For more about “The Propaganda of Freedom,” including a podcast and an NPR feature, click here.

October 9, 2025

Yunchan Lim and the Scent of Nostalgia

I am old enough to remember a time when famous pianists were great pianists. It is a topic I rehearse with pianists of my acquaintance who like myself began attending recitals in the 1960s. So we heard Argerich, Arrau, Cliburn, Curzon, Gilels, Horowitz, Moravec, Serkin, Richter, Rubinstein. Some of us (not me) were lucky to hear Kempff and Michelangeli, who were not regular visitors to the US. These artists were very different from one another – which is the point. They were personalities. (I also discover joking agreement that Pollini, though famous, was an exception proving the rule.)

Today – our discourse continues – anyone can be a famous pianist. Attire and social media play a disproportionate role. Lately, however, a couple of young Koreans – Yunchan Lim and Seong-Jin Cho — seem the genuine article: young pianists who might become both famous and great. They cultivate a personal style. And it seems driven from within, not imposed from without.

But Lim has stumbled. His new Decca release – his first studio recording – is a mistake. The music is Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons: a collection of twelve cameos, one for each month. I learned about it from Dave Hurwitz’s rambunctious “Classics Today” review on youtube. “The tunes are broken up into globular little gestures,” Hurwitz (who has a sense of humor) intones. “A fetish for articulation draws attention to itself.” The interpretations are crushed by “mannerism and gesture.” Amateur pianists “would do it better because they would do less.”

My curiosity was aroused because I adore these little Tchaikovsky pieces. I have played them myself for decades. My favorite is “October” – the mind’s eye envisions an iconic Russian vignette of red and yellow leaves adrift above a solitary forest path. A leisurely performance lasts five minutes. Lim’s recorded performance lasts six minutes. His personal inflections, coloring every sad leaf, fracture Tchaikovsky’s picture into a mosaic of subjective detail. As the playing, per se, is beautifully nuanced — Lim is unquestionably a poet whose every gesture is sincere — this failure becomes interesting. Why is “October” so fragile?

The answer, I would say, is that it exudes an intimate scent of nostalgia, a yearning for days bygone, that the 21-year-old pianist doesn’t share. It is in fact an exquisite exercise in memory no longer accessible to composers and – given the nature of the times in which we now live — increasingly alien to performers and audiences.

The earlier Romantic keyboard cameos of Schumann, though a likely influence on Tchaikovsky, can be wistful. But they’re not stranded in the past. The composer who most parallels Tchaikovsky is Grieg, in his 65 Lyric Pieces for piano. On a grand scale, there is the nostalgia of Rachmaninoff. The musical retrospection of these composers traverses long corridors of time past. It builds upon itself.

I would call Tchaikovsky’s “October” a double act of retrospection. It begins impersonally, with its forest tableau. But the middle section introduces a second, more personal voice, in dialogue with the tune at hand. This interaction rapidly drives to a piercing climax. A reprise follows. The morendo (“dying”) coda — seven measures long, diminishing to pppp — is tragic. And so we have remembered both the forest path and a further stabbing memory occasioned by those falling leaves.

You can sample Lim’s performance here. An extraordinary version of the same music, in live performance, is that of Mikhail Pletnev, here. Pletnev is an idiosyncratic artist invested in Romantic liberties of voicing and rubato. He is also, obviously, keenly cognizant of his Russian cultural inheritance. I would be surprised if he were not a devoted reader of Russian literature and a connoisseur of Russian visual art.

Pletnev also excels in Grieg’s Lyric Pieces. Among the biggest of these is “Vanished Days” (Op 57, No. 1). Its falling motion, in D minor, limns a chromatic haze of memory. Misted ascents in the left hand streak the tune as it recedes ever deeper into the past. An Allegro vivace middle section, in D major, discloses an earlier memory – of youth. It gathers strength before sinking back into the minor. A fortissimo climax ensues, then a hopeless Adagio terminus. You can hear Pletnev play “Vanished Days” here. Many another Lyric Piece layers memories in similar fashion. The titles include “Homesickness,” “From Days of Youth,” “Gone,” and – coming last — “Remembrances.”

Grieg was born in Bergen. He remained there, late in life, even though the climate proved fatal to his health. There were 30,000 residents, with his Troldhaugen on the outskirts of town. He called his Norway “north of civilization.” This was said in frustration, but it was a lover’s frustration. Rustic Norwegian dance and ceremony were his musical lifeblood. He also drew on Nordic myth. In 1905 he read (in English) Tchaikovsky’s Life and Letters (the book by the composer’s brother Modeste) and recorded: “What a noble and true person! And what a melancholy joy to continue in this way the personal acquaintance established in Leipzig in 1888! It is as if a friend were speaking to me.” Tchaikovsky wrote of Grieg’s music: “What enchantment, what spontaneity and richness in the musical inventiveness! What warmth and passion in his singing phrases, what a fountain of pulsating life in his harmonies, what originality and entrancing distinctiveness in his clever and piquant modulations.”

Tchaikovsky died in 1893, Grieg in 1907. Then came the Great War – its senseless origins and peculiar ferocity. It introduced gas warfare, barbed wire, and the machine gun. It cost eight million soldiers’ lives. At the Battle of the Somme, the largest military engagement in recorded history, eleven British divisions arose along a thirteen-mile front and began walking forward. Out of 110,00 attackers, 60,000 were killed in the first day. As early as 1915, The New Republic pertinently inquired, “Is it not a possibility that what is today taking place marks quite as complete a bankruptcy of ideas, systems, society, as did the French Revolution?” Americans were left pondering why men had died, as Ezra Pound wrote, “for a botched civilization.” “The plunge of civilization into this abyss of blood and darkness,” wrote Henry James, “is a thing that . . . gives away the whole long age during which we have supposed the world to be, with whatever abatement, gradually bettering.” The cost to the arts has many times been surmised. The war discredited cultural nationalism. It erased nobility of sentiment. It cluttered with obstacles the long corridors of memory that Tchaikovsky and Grieg had gently suffused with nostalgia.

One of the reasons Charles Ives is the supreme American concert composer is that, unlike Aaron Copland, he was fortunate to come of age before World War I. He was profoundly invested in American cultural memory: the Civil War and slavery; the Founding Fathers and the Revolution. His memories of Danbury were pre-war memories: the circus band marching down Main Street, the sentimental songs of the parlor.

It is in the bygone parlor that The Seasons and the Lyric Pieces best belong. We can still reconnect to these pieces at Carnegie Hall — but they grow ever more elusive.

I can still remember my bedtime song, as a baby. My mother would sing it wordlessly – Grieg’s Second Norwegian Dance.

Some more piano blogs:

–On “ripeness,” Claudio Arrau, and Yunchan Lim, click here

–On Sergei Babayan, click here

–On Babayan, Danill Trifonov, and Yuja Wang, click here

–On Vladimir and Bernie Horowitz, click here

–On Alexander Toradze, click here

–On Pedro Carbone and Spanish music, click here

Lexo’s Journey

A new CD pays tribute to Alexander Toradze and his father, the composer David Toradze. For those of us who loved Lexo, this feels like a necessary way of keeping his memory alive. I am personally grateful to Ettore Volontieri for making this happen, and to Behrouz Jamali for permitting us to excerpt audio from his exceptional film “An Hour with Alexander Toradze and Joseph Horowitz.” For the CD booklet, I wrote:

I have never met anyone more gifted at thinking while speaking than Alexander Toradze. It was doubtless in his native Tbilisi, where toasting is a competitive creative act, that Lexo acquired his understanding of conversation as an art. A Toradze story required an introduction, a climax, and a coda, suitably interspersed with digressive footnotes and annotations. At the piano, his mettlesome intellect engaged in fraught interaction with a volcano of feeling.

As a Toradze tale could not possibly be abridged or excerpted, a Toradze “interview” was invariably a false experience. For years I attempted to sit him down to speak, unimpeded, in front of a camera. Finally, during a Shostakovich festival in Washington, D.C., with my PostClassical Ensemble, I shoved him into a cramped office in which Behrouz Jamali awaited with his equipment. My goal was to have Lexo tell only two stories – one about his father, one about Ella Fitzgerald – and then to describe the manner in which he interpreted Prokofiev’s Seventh Piano Sonata (which he was performing that week).

Behrouz phoned the next day to inform me that there was no possibility of editing this footage into a film. This did not surprise me; the tempo of Lexo’s discourse, its ebb and flow, accelerations and diminuendos, was inviolable. I told Behrouz to take a deep breath. He phoned the next day and announced that he now discovered that the film was already there. And so it was. Behrouz proceeded to elegantly undertake some snipping, then to add some supplementary footage, and it was done. You can see it, all 59 minutes, on youtube. And you can hear two excerpts on the present CD.

The first excerpt is a story about Lexo’s father. The second is an exegesis on Interpretation. Initially, Lexo focuses on the first movement of the Prokofiev sonata, in which he heard the sobs of wartime mothers. Lexo always required a story – even for Beethoven’s Op. 109 Piano Sonata, his eventual topic here, in which he glimpses Beethoven’s vicissitudes in love. As he once told me:

“I can’t just look at a score and think: Gosh, what a beautiful concerto; I’m going to make it just delicious. That doesn’t interest me. Composers, if they are expressing something, they do it because they cannot express it in other ways, because there is something they need to get out of their system. You don’t need to get out of your system pure happiness and joy. No, because it’s comfortable. So you need an element of discomfort, of irritation, certain spiritual urges that make you create this or that. That’s where our real differences are – in pain. Tolstoy, at the beginning of Anna Karenina, says, ‘All happy families resemble one another; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.’ So I have to find this element. I have to find two or three pages of pain. Then I use that, because I can associate with that, and elaborate. I can use my own experience. And fortunately, my own experience with pain is quite considerable. It has been enough.” [Quoted from The Ivory Trade (1990), p. 100]

The Ella Fitzgerald story that Lexo told Behrouz, missing from our CD, is about the urgency of jazz in Soviet Russia – and how jazz vitally infiltrated the Toradze piano style. All this pertains to his interpretation of his father’s Piano Concerto (which Lexo premiered and performed three times). Its jazzy pages are electrified by the physicality of Lexo’s stabbing accents and syncopations. And doubtless Lexo found a story in the narrative pages. If he is no longer around to tell us what that story happened to be, and if the story actually coincided with what his father told him about the piece, it really doesn’t matter – what matters (as I remark on film) is that Lexo’s stories mattered to him.

***

Notwithstanding Lexo’s enduring passion for the piano works of Ravel, his repertoire concentrated on four Russians: Rachmaninoff, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Shostakovich. They have in common Russian turmoil. The first two lived in an exigent condition of exile they differently negotiated. The third quit his exile to return, controversially, to Mother Russia. The fourth experienced a kind of internal exile as a people’s artist, a beneficiary and victim of the state.

The turmoil of Lexo’s own exile was intermittent but cruel. He was born in 1952 to a family anchored in art. At the Moscow Conservatory, he thrived on the support of inspired pedagogues, but loudly feuded with others. Touring as a Soviet pianist, he was enthralled by new experience and infuriated by restrictions placed on his activities. He defected suddenly, in Spain in 1983, when he discovered himself travelling with a Russian orchestra and yet not permitted to perform. He wound up, incongruously, in South Bend, Indiana, where he created the Toradze Piano Studio. It toured widely, only to implode. His prolonged American honeymoon ultimately stranded him, a stranger in a strange land.

The final chapter of Lexo’s life transpired in relative self-seclusion: in loving partnership with Siwon Kim, his final protege. When Vladimir Putin’s Russia invaded Ukraine, Lexo’s response was unique: he instantly foresaw that the Russian artistic environment in which he had been raised, and which had been his cherished inheritance for more than half a century, would be poisoned for decades to come. I have no doubt that this intuition hastened his death in 2022.

It was the magnitude of Lexo’s presence – his particular breadth of experience and understanding – that ultimately sealed his contribution to the tumultuous decades he inhabited.

To read my eulogy for Lexo, click here.

September 17, 2025

Bernstein and Shostakovich — A Rosetta Stone?

The new online issue of “Prelude, Fugue, and Riffs,” the newsletter of the Leonard Bernstein Office, publishes an essay of mine suggesting that Bernstein’s relationship to Dmitri Shostakovich is a “Rosetta Stone” in the Bernstein odyssey. It’s a glimpse of my book-in-progress: “Bearing Witness: The American Odyssey of Leonard Bernstein.” You can read the whole thing here. What follows is an excerpt:

Twenty-eight years [after Leonard Bernstein took the New York Philharmonic to Soviet Russia], the expatriate Russian pianist Vladimir Feltsman talked to Bernstein about his impressions. “Bernstein’s visit to Russia was very important at that particular time — the scent of freedom was beguiling and irresistible,” Feltsman remembered, and added: “His most precious memory was meeting Boris Pasternak.” But Dmitri Shostakovich’s validating handshake proved a more lasting influence.

In the long view, Bernstein’s significance is broadly humanistic. An exemplary cultural missionary, he served a function never as necessary as today, and never before as absent.

Bernstein the humanist was acutely prescient. He prophetically understood that classical music would dissipate from the American experience unless or until it struck deeper New World roots. He foretold the erosion of the American arts. He fought the erasure of American cultural memory. The demise of the Kennedy White House, in which he had been a guest, tarnished his American dreams. Then came Vietnam and Watergate. His signature concerts included memorials for JFK and RFK. . . .

As Bernstein appreciated earlier than others, Shostakovich’s ultimate genius was to bear witness. The Bernstein odyssey, in its many dimensions, equally bore eloquent witness to a twentieth century of American ferment and travail. In the Bernstein saga, the Bernstein/Shostakovich nexus is a neglected Rosetta Stone.

August 24, 2025

What’s An Orchestra For? – Mulling Salonen’s Resignation and a Dispiriting San Francisco Sequel

Esa-Pekka Salonen

Among my most-read blogs is “What’s An Orchestra For?” – Mulling Esa-Pekka Salonen’s Resignation from the San Francisco Symphony.” I posted it on March 26, 2024, and it still attracts readers practically every day. The topic is the abrupt departure of a genuine music director propagating a tangible and timely artistic vision. I wrote that this story was “dominating classical-music news because Salonen made no secret why he quit: a falling out with the board over his elaborate artistic plans and their cost.”

That would seem a terminus but alas there is a sequel. Because my daughter Maggie happens to live in San Francisco, I went on the web the other day to have a look at the San Francisco Symphony’s upcoming season. What I think I discovered was a dispiriting provincialism driven by evident or imagined desperation.

Desperate orchestras hug three survival strategies. They engage big-name soloists with enormous fees. They program a bloat of standard repertoire. They schedule as many pops events as their institutional conscience can tolerate. Cumulatively, this is a short-term fix that risks destructive longterm consequences.

San Francisco’s biggest stars for 2025-26 are Itzhak Perlman, Yo-Yo Ma, Joshua Bell, and Yuja Wang. Meanwhile, the orchestra is conducting a music-director search. There are 24 guest conductors, many of whom are young (it matters little these days that conductors ripen with age). One who is not, Jaap van Zweden, has the most assignments. Judging from his brief New York Philharmonic tenure, he is not a likely cultural leader.

Though a plethora of magnificent silent films invite live orchestral accompaniment, the San Francisco Symphony’s countless movie nights include not a single ambitious choice. Here’s a sampling: Vertigo, Barbie, Home Alone, Pirates of the Caribbean, Crouching Tiger– Hidden Dragon. (The South Dakota Symphony this season screens the 1929 Soviet classic The New Babylon with a pit orchestra performing Shostakovich’s hilarious yet shattering score, surely one of the most formidable ever to mate with the moving image.)

For San Francisco’s subscription concerts, the major repertoire at hand includes:

–Tchaikovsky Symphonies Nos. 4 and 5 plus the Violin Concerto and First Piano Concerto

–Grieg’s Piano Concerto

–Vivaldi’s Four Seasons

–Beethoven Symphonies 2, 5, 7, 9

–Mozart Prague and Jupiter Symphonies

–Dvorak’s New World Symphony, Symphony No. 7, and Cello Concerto

–Berlioz Symphonie fantastique

–Rimsky-Korsakov Scheherazade

—Gershwin Piano Concerto and An American in Paris

–Mahler Symphonies 1 and 9

–Brahms Symphony No. 2

I lived in the Bay Area during the early 1970s, when the San Francisco Symphony and (especially) San Francisco Opera were civic signatures, hosted with pride. Kurt Herbert Adler managed to assemble casts comparable to the Met’s in New York. The house specialized in Wagner, typically under-rehearsed yet ignited by a first-rate East German-based conductor, Otmar Suitner. The singers included Birgit Nilsson, Leonie Rysanek, Jess Thomas, Thomas Stewart. I less often attended Seiji Ozawa’s San Francisco Symphony concerts, but remember Arnold Schoenberg’s massive Gurrelieder – a bolder undertaking than anything today’s San Francisco Symphony attempts over the course of nine months.

Before and after Ozawa, the orchestra’s music directors included Pierre Monteux, Josef Krips, Herbert Blomstedt, Edo de Waart, and Michael Tilson Thomas. San Francisco today – a software mecca — is not the San Francisco I once knew. That may be the main story here. And yet Salonen’s were very likely the most sophisticated programs of any American orchestra. That legacy isn’t just being ignored; it’s likely to be erased.

As for the San Francisco Opera, its season is drastically shorter than half a century ago. But they’re presenting a new production of Wagner’s Parsifal – compared to the Symphony’s diner menu, no small feat. And if there are no glossy names, that may be a sign of health.

Maggie has never had an opportunity to attend Parsifal. I told her that it was the one San Francisco musical event she couldn’t afford to miss.

To read my previous blogs about Salonen and San Francisco, click here, here, and here.

To read a blog questioning the Chicago Symphony’s decision to engage Klaus Makela as “music director,” click here .

August 17, 2025

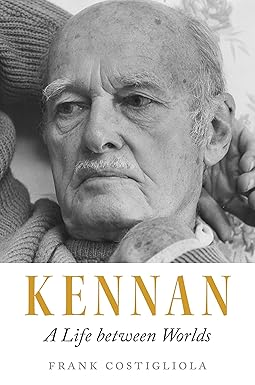

Re-Encountering George Kennan — and “From the River to the Sea!”

I felt impelled to write the long essay that follows after discovering Frank Costigliola’s acclaimed new biography of George Kennan. The initial topic is “the most extreme display of public effrontery I have ever encountered” — Kennan excoriating my fellow students at Swarthmore College in 1967, then refusing to take questions. My eventual topic is today’s students, whom I compare unfavorably with my sixties generation. I conclude: “Pace Kennan, at Swarthmore we ‘rebels’ never disrupted classroom instruction with chants. When I hear ‘From the River to the Sea!’, when Zionism is equated with colonialism, I become Kennan and Allan Bloom both. French Indochina was an example of colonialism. Israel – whatever one makes of its implementation or of its sorry fate today – was created in the wake of the holocaust, a logical beneficiary of the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire. What, exactly, does today’s chant of the moment signify? ”

The most extreme display of public effrontery I have ever encountered was on December 9, 1967 — the day George Kennan came to Swarthmore College. The entire student body was required to attend. We duly proceeded to Clothier Hall to hear him anathematize us as lazy and stupid. When that was over, he took no questions and was whisked off campus while we gaped and shouted on the sidelines. Then approximately one-third of the student body (the total enrollment was only 1,200) converged on the administration building. The campus engineer appeared and said that if we did not vacate the second floor common room, the floor might collapse. As this was not a ruse, we left in a rage.

Not until the publication of Frank Costigliola’s new biography – Kennan: A Life between Worlds – did I realize that the Swarthmore speech of America’s most famous and influential Cold War foreign affairs officer was subsequently published in the New York Times Magazine. Or that a book ensued – Democracy and the Student Left – reproducing the speech in tandem with two addenda: 39 letters written in response, mainly by students and teachers from 21 institutions of higher education (not including Swarthmore), and a 100-page essay, “Mr. Kennan Replies.”

Re-encountering Kennan’s address, now titled “Rebels Without a Program,” I find it even more obnoxious than I remembered. But the greater surprise is Kennan’s “reply” — his discontents with America and with Americans, I discover, were substantially more profound than ours had been during the years of Vietnam and Watergate. And these anxieties and misgivings – he clearly foresaw the depredations of contaminated air and water, of media and social media, of politics and government — were prescient, even prophetic.

As I now appreciate, that “Rebels Without a Program” misdescribed his Swarthmore audience mattered not in the least to Kennan. His ostensible topic was a smokescreen. Neither then nor afterwards did he seriously attempt to ascertain who we were or what we thought. He had received a timely invitation to help celebrate the opening of the new Swarthmore College library. And his agenda was already set.

It’s a truism that each generation debunks the next as callow. Kennan subscribed to that axiom in 1967. And so do I in 2025. I cannot help it.

***

With “Rebels” at hand, I can succinctly document its contents.

We violated a university ideal: “the association of the process of learning with a certain remoteness from the contemporary scene.” In place of self-possession, we manifested “screaming tantrums and brawling in the streets.” We brandished “banners and epithets and obscenities and virtually meaningless slogans.” Our eyes were “glazed with anger and passion, too often dimmed as well by artificial abuse of the psychic structure that lies behind them.” We were “full of hatred and intolerance and often quite prepared to embrace violence as a source of change.” We threw stones, broke windows, overturned cars. As for those of us who were “hippies” and “flower people,” Kennan expressed “pity . . . not unmixed, in some instances, with horror.” Whereas we indulged in “certain sorts of stimuli” provoked by “chemical agencies,” only “through effort, through doing, through action – never through passive experience – [could] man grow creatively.” Kennan even disavowed “civil disobedience” as an instrument of protest in democratic societies. He concluded: “I know that behind all the extremisms – all the philosophical errors, all the egocentricities and all the oddities of dress and deportment – we have to do here with troubled and often pathetically appealing people, acting, however wisely or unwisely, out of sincerity and idealism.”

Of this list of attributes, the only ones recognizably pertinent to Kennan’s Swarthmore audience, I would say, were the widespread use of “chemical agencies” and the prevalence of “oddities of dress” – neither of which interfered with a regime stressing reading, writing, and talking. In fact, never since have I encountered a community as fundamentally benign as my Swarthmore classmates.

In his “reply” to the 39 letters, Kennan added his own reminiscence of his Swarthmore visit: “I came away from the podium . . . feeling that I had done my best to speak honestly about matters that might be presumed to be on the minds of other people present. But no sooner had I emerged from the stage door of the College’s auditorium that I was made aware – by the presence there of a group of angry young men, mostly bearded, who hissed their disagreement and resentment at me like a flock of truculent village geese – that I had stepped on some tender nerves.”

I was one of those. What trampled our nerves was less his speech than his refusal to engage in the very “process of learning” he had preached. Had he done so, he might have absorbed from our testimony that, notwithstanding its reputation of as the nation’s pre-eminent liberal arts institution, Swarthmore in 1969 was languishing in a state of advanced obsolescence. In my four years of study (notwithstanding my beard, I graduated in 1970 with Highest Honors), I did not have a single teacher who was not a white male. Though I majored in American History, there was no mention of Fredrick Douglass or W. E. B. Du Bois or Crazy Horse. Though my interests were broad, no interdisciplinary majors were permitted. Though I minored in Music, played the piano, and sang in the chorus, no academic credit was allowed for creative pursuits. As of 1967, neither the Political Science nor the Philosophy Department offered courses in Hegel or Marx. The Sociology/Anthropology Department was new and weakly staffed. The Frankfurt School did not penetrate the curriculum. So far as I could ascertain, the college’s major asset was its student body. The biggest personalities on campus were not the professors.

The administration was not insensitive to the challenges at hand. In 1966, it had convened a Commission on Educational Policy (C. E. P.) with a mandate to recommend specific proposals for change. But implementation proved slow and obtuse. I remember being interviewed about the “intellectual content” of playing a musical instrument. That the arts contribute to character and personality, to emotional and psychological well-being, was deemed irrelevant. Though the C. E. P. determined that “artistic activity is intelligent activity,” dance and film were exempted from this finding, and credit for work in the creative arts was only sanctioned on a limited basis. In 1969, two years after Kennan’s speech, Swarthmore African-American Students Society (SASS) lost patience and occupied the admissions office to demand that the college enroll more Black students (there were 47), Black teachers (where was one), and Black administrators (there were none). This was a considered act of civil disobedience, sans violence or threats, fortified by extensive discussion and negotiation.

Spring 1970 was a time of nation-wide student strikes and teach-ins. At Swarthmore, a new hire in the Philosophy Department took charge. He was a Socratic Hegelian – and Hegelian epistemology, rejecting Anglo-American empiricism, proved a Swarthmore intellectual epiphany (I still treasure my densely marked copy of his Philosophy of History). A handful of students dropped out and migrated to the militant far left. On campus, the only individual who advocated violence was an outsider doubtless in the employ of the US Government. Though many skipped final exams, the Kennan critique remained mostly irrelevant – our political arousal was also formidably intellectual. The chairman of the Sociology Department counselled that we return to the classroom, oblivious to the absorbing sociological phenomenon of a popular uprising at hand. I was myself delegated to propose to the Political Science Department that a course in Marxism be offered. I was informed by a sneering Associate Professor that a mini-course for one-quarter credit might be considered – and expanded if there was anything left over to teach. Notwithstanding a Thermidor during which dissident faculty members were purged, the students ultimately prevailed. A 1986 history of the college painstakingly concluded that “it is generally agreed that Swarthmore had not . . . done enough” – that SASS, in retrospect, was an agent of necessary change.

***

Looking back, were we “Rebels without a Program”? We were right about Vietnam and right about Richard Nixon. But we were also undeniably callow: we lacked a long view. This was George Kennan’s calling card: his signature as a foreign policy analyst steeped in historical learning and philosophical repose. When he wasn’t being short-sighted and presumptuous, he became reflective and wise. It’s all in Democracy and the Student Left.

Pondering the 39 letters, Kennan at first remained maddeningly supercilious. As if the letters – in fact, a miscellany of self-appointed responses – furnished empirical corroboration, he redoubled his ostensible observations. “Today’s radical student” is “anxious, angry, humorless, . . . over-excited and unreflective . . . His nostrils fairly quiver for the scent of some injustice he can sally forth to remedy.” The writers at hand manifested “the lack of interest in the creation of any real style and distinction of personal life [which] enters into manners, tidiness . . and even personal hygiene.” Their avowal of civil disobedience furnished further evidence of immaturity: “I am affected, I must admit, by an inability to follow the logic of pacifism and nonviolence as the bases for a political philosophy.” With astounding presumption, Kennan even inferred: “The politics, like what one suspects to be the love life of many of these young people, is tense, anxious, defiant and joyless.” In sum, the Rebels Without a Program did not belong in any place of learning. “If the respect for intellectual detachment . . . is really as small as it would seem to be from these letters . . . , then the contemporary campus is no place for the odd man who might like to devote himself to the acquisition and furtherance of knowledge.” Addressing the rebels directly, he inquired: “What in the hell – if we might be so bold as to ask – are you doing on a university campus?” What is more: “They jump to the conclusion that they ought to run the place.”

Other assertions are simply counter-factual. Though opposed to the war in Vietnam, Kennan inferred that “the alternative to our effort there would be the subjection of the South Vietnamese people” to a “dictatorship ruthless, bloody and vindictive.” Is that what Vietnam became? And Kennan loftily asserted: “It is not an exaggeration to say that an abandonment of the draft would alone cure a large part of the troubles of the present generation of students.” At Swarthmore, we did not greatly fear being drafted – we knew there were ways out.

Then Kennan asked himself whether there were further, underlying maladies at hand. This inference of “some inner distress and discontent” at first seems patronizing. But 216 pages into Democracy and the Student Left, it ultimately powers an authentic inquiry so impressive as to practically redeem the book. Adopting a different tone – virtually a different persona – he extrapolates five “dangers within ourselves, within our civilization, that cast . . . a cloud over the future of our society.”

The first is “the question of what is happening, physically, to the natural environment necessary not only to sustain life in this country to but to give it healthfulness and meaning. . . . As the world’s greatest industrial nation, as the possessor of the largest single component of its industrial machinery, also as its most wasteful and industrially dirty society, and finally as the world’s foremost nuclear power and one which has yet to give any very satisfactory explanation of the manner in which it disposes of its nuclear wastes, we have a very special responsibility here.” This 1968 warning also references the destruction of topsoils, the slashing of forests, the exhaustion of fresh water, the poisoning of ocean beds, and the destruction of the ecology of plant and inset life.

Second on Kennan’s list is the extent to which advertising has permeated “the entire process of public communication in our country.” Mass communication, he writes, is made “trivial” and “inane.” “We will not, I think, have a healthy intellectual climate in this country, a successful system of education, a sound press, or a proper vitality of artistic and recreational life, until advertising is rigorously separated from every form of legitimate cultural and intellectual communication – until advertisements are removed from every printed page containing material that has claim to intellectual or artistic integrity and from every television or radio program that has these same pretensions.” He advocates “a revolution in the financing and control of the process of communication generally” – even if that means “bringing in the government.”

The third danger is the private automobile. “It is a dirty, noisy, wasteful, and lonely means of travel. It pollutes the air [and] ruins the safety and sociability of the street. . . . It has already spelled the end of our cities as real cultural and sical communities. . . . Together with the airplane, it has crowded out other, more civilized and more convenient means of transport.” And it creates a problematic dependency on oil.

Fourth: “the state of the American Negro,” the nation’s “greatest social and political problem.” “I see the possibilities for progress . . . much less in the concepts of integration – much less in the possibility of creating a homogenized society – than in some sort of a voluntary segregation and autonomy for large parts of the Negro community.” He is surprised to find common cause with advocates of “black power” whose “methods and spirit” he otherwise abhors.

Finally, addressing the American political system, Kennan decries “the bloated monstrosity and impersonality of the federal government” and the related decay of state governments. He favors “new regional organs of government.” He wants to reduce the cost of running for public office. He deplores “the tone and rhetoric of American public life.” He wishes for a third national political party that would be content to remain a minority, and “place ideas and convictions ahead of electoral success.”

The totality of Kennan’s prescriptions for America could readily be dismissed as the pipedream of a disenfranchised aristocrat. Not only is he a man in love with the past; the past he idealizes is European or Russian. He identifies not with Jefferson, Adams, and Madison, but with Tolstoy and Chekhov. His diagnoses are more impressive than his proposed solutions. Even so, the timeliness of this culminating jeremiad is stunning. An America weakened in spirit, shallow in feeling, Kennan warns, is an America at risk. “I fear the loss of our liberties through a descent into fascism in strict accordance with law far more than I fear the protesting ‘lawlessness’ of our youth. . . . Majorities are not to be trusted. They are apt to resign their powers to the tyrant.”

As for today’s collegiate youth, are they not victims of the fundamental conditions that Kennan extrapolated in 1967? When – setting aside pompous complaints about rebellious attire and deportment, violence and drugs — he decries a “world of gadgetry” that captivates the young, when he paradoxically finds them “more childlike than students of an earlier and simpler age,” when he worries that they are manipulable, adrift from cultural memory, crippled by shallow pleasures, I discover myself morphing into George Kennan. And I am further reminded of Allan Bloom, whose Closing of the American Mind aggravated my generational loyalties in 1987 – but now seems prescient. Subtitled How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today’s Students, Bloom’s polemic was a national sensation, a trigger-point for debate over the legacy of the sixties and its “counter-culture.”

No less than Kennan in 1967, Bloom in 1987 caricatured my generation. His disparagement of listeners to rock music (“it artificially induces the exaltation naturally attached to the completion of the greatest endeavors”) and devotees of recreatinal drugs (“their energy has been sapped and they do not expect their life’s activity to produce anything but a living”) were instantly notorious. He maintained that a generation out of touch with great music, great literature, great traditions of philosophic thought – all unabashedly Western – was a generation afflicted with “closed minds” and “impoverished souls.” Swarthmore in the late 1960s was nothing like that.

But no less than Kennan, Bloom – read today — extrapolated fatal longterm trends – unwanted, unanticipated consequences of “rebellion” at hand. Debunking “cultural relativism,” Bloom fingered what we now call identity politics and a linked discourse stigmatizing “cultural appropriation” – a discourse that, to many my age, seems more impoverishing than nourishing for students’ souls. He discerned that a mounting failure to appreciate Western traditions was eviscerating the academy. He deplored a tendency to ecumenically equalize all cultural endeavor, old and new, East and West. He foresaw an exaggerated regard for the other and otherness fracturing democratic community. Even Saul Bellow’s introduction to The Closing of the American Mind reads as if written yesterday: “The heat of dispute between Left and Right has grown so fierce in the last decade that the habits of civilized discourse have suffered a scorching. Antagonists seem no longer to listen to one another.”