Andrew Dubber's Blog

December 19, 2024

Albums of the Year 2024

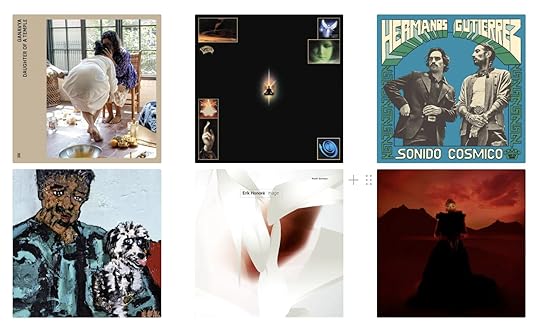

As you might know, most years I make a list of my favourite albums of the year. Sometimes there are 10, other times over 100. This year, I’ve tried to keep it to a manageable Top 20. To do that, I decided on three key criteria:

I think they are great recordsI really enjoy listening to themI would like to (or already) own them on vinylThat last point is key to this list. I listen to an awful lot of new music, mostly while out walking the dogs or in the car on my way somewhere. The shortlist of new release records I liked in 2024 was over 300 albums long. However, one of my favourite things to do is to sit down on the sofa, put a record on the turntable and just listen to side one, followed by side two.

That requires a different sort of album. It has something to do with how interesting they are, how personal, how much they work in that private space, or perhaps how much they warrant full attention.

The listHere are the records that fulfilled all three of those criteria (and while ranking is always spurious, I’m pretty happy with the order they’ve ended up in here).

As usual, my answer to why your favourite album isn’t included is that I missed it or didn’t like it as much as you did. And that’s fine.

Titles all link directly to the album on Spotify in each case – not because that’s what I use (I’m about 90% Qobuz) but because it’s probably what you use. Bandcamp [BC] links are included, where available, for the virtuous.

Daughter of a Temple – Ganavya [BC]Sonido Cósmico – Hermanos Gutierrez [BC]The Road to Hell is Paved with Good Intentions – Vegyn [BC]LAFANDAR – Heems [BC]Odyssey – Nubya Garcia [BC]Triage – Erik Honoré [BC]Novela – Céu Meaning’s Edge – Djrum [BC]Rising – Jasmine Myra [BC]Night Reign – Arooj Aftab Suite – Dan San [BC]Confidenza (Original Soundtrack) – Thom Yorke [BC]Unusual Object – Josh Johnson [BC]Piano Reverb – Jasmine Wood [BC]Wusul – Shay Hazan [BC]Mer Tan Itev – Tigran Tatevosyan [BC]Echoes of Becoming – Canberk Ulaş [BC]Mount Matsu – YĪN YĪN [BC]Passacaglia – Adam Baldych & Leszek Możdżer [BC]Touch of Time – Arve HenriksenBonus recommendationsThere were, of course, quite a few albums that only met one or two of those criteria. For instance, here are some records from 2024 that I enjoy listening to. I don’t happen to think they are great albums, necessarily, but I do like them a lot.

Freak the Speaker – The Allergies [BC]Sunbörn – Sunbörn [BC]Loopholes – Bruk Rogers [BC]Painting with John – John Lurie [BC]On the Lips – Molly Lewis [BC]Then there are the ones that I think are great records that I admire and respect, but in all honesty, I don’t actually enjoy listening to them all that much. Either the effort/reward ratio is off, or it’s just not my cup of tea. Your mileage may vary, of course. They’re not for me, but they are excellent:

Silence is Loud – Nia ArchivesLetter to Yu – Bolis Pupul [BC]Toitū to Pūoro – Alistair FraserVou Ficar Neste Quadrado – Ana Lua Caiano [BC]Y’Y – Amaro Freitas [BC]Then there are some that I happen to think are great records, AND I very much enjoy listening to them, but I don’t want to sit down and listen to them on vinyl at home, paying close attention. These are more for driving or walking the dogs. I don’t have a particular explanation for that other than that they tend to be more upbeat and pop-leaning, on average. They’re great but just intuitively fell outside the list.

BRAT – Charli XCXNotes – Nathan Haines [BC]YHWH is Love – Jahari Massamba Unit [BC]Fabiana Palladino – Fabiana Palladino [BC]Tourist – Why Kai [BC]And finally, my favourite song of the year, which was not on any of these albums:

What Now – Brittany Howard

Brittany Howard is being compared (positively, because how else?) to Prince quite regularly these days. I can sort of see that. The greatest thing about this song is that she’s essentially invented what immediately became my new favourite guitar sound. That is such a Prince thing to do. The album was, for me, just okay, but the song is pretty spectacular.

Here’s a Spotify playlist of songs representing all these records, plus one or two other bits and pieces that I thought warranted a spin. Hope you’ve had a great 2024, both musically and in general – and, whether or not that’s the case, that 2025 is better.

The post Albums of the Year 2024 first appeared on Dubber.December 11, 2024

NEB Concepts podcast

For the past couple of years, I’ve been working on a European-funded project called digiNEB, which connects the New European Bauhaus (NEB) initiative with the digital ecosystem.

For the past couple of years, I’ve been working on a European-funded project called digiNEB, which connects the New European Bauhaus (NEB) initiative with the digital ecosystem. If you’re not immersed in the European policy context, it’s possible you might have missed NEB. Essentially, it’s about addressing the green transition not by imposing a bunch of restrictions and targets, but by designing the world differently – to be sustainable, inclusive and beautiful. Things we want to move towards, in other words. It engages architects, designers, city planners and communities to address grand challenges.

Part of my role in the project was to produce a podcast series in which I interview key players in the NEB initiative. I did that, it’s called NEB Concepts, and you can listen to it here.

One of the things you do when you’re involved in European-funded projects is you write reports. As part of one of these deliverables, one of my colleagues from a partner organisation sent me some questions about the podcast. An interview about why we did interviews.

Here’s what I said.

Short introduction to the podcast

The digiNEB project has produced a modular podcast series that features conversations about sustainability, innovation, and human-centred design with leading architects, educators, and project leaders from the NEB community. NEB Concepts allows listeners to explore themes by topic tags such as climate adaptation, technology integration, and interdisciplinary collaboration – or continue with the wide-ranging thoughts of a single interviewee. Each short episode provides a collection of ideas and practices, projects and reflections, highlighting the twin transitions and the transformative potential of the New European Bauhaus for a more inclusive and sustainable future.

Motivation: Why did you choose a podcast to share knowledge about the New European Bauhaus (NEB)? What unique value does it offer?

There are three main reasons: depth, durability and repeatability. Unlike a publication, you get the richness of the experts expressing their ideas in a medium that allows for questioning. There is the space and the scope for an interviewer to explore further, ask deeper questions and respond to arrive at a fuller understanding of a topic, usually presented without jargon.

The podcast also has permanence. Unlike social media posts that are ephemeral and fleeting, podcasts can serve as a durable resource where you can return to hear – in the speaker’s own words – what they said and, importantly, how they said it.

And unlike a workshop, you don’t have to rely on your memory or your notes – you can listen again at any time. In that respect, it represents an ideal form of ‘masterclass’ – with direct access to the expert that you can replay or share – and in a format that is conversational, informal and personal.

Impact: How does the podcast format compare to other methods like workshops or publications in fostering innovation?

One of the most straightforward and primary keys to fostering innovation is to embed the understanding that making an impact is possible. That one piece of knowledge unlocks so much innovation potential. What a podcast does is to humanise the communication. It makes the person speaking relatable, and so the listener can imagine that the kinds of innovation they describe might also be possible for them.

Publications, in particular, tend to be one-way communication: expertise being presented in the formal style of the discipline. This distances the reader from the author. Despite interactive elements, workshops also tend to have a similar ‘presenter and audience’ power dynamic.

A podcast is personal and conversational, and the interviewer stands in for the listener, able to ask questions that elicit further information and interrogate the premises and conclusions of the information being presented while creating a rapport that ensures the facts presented have an emotional and not just intellectual impact.

Ecosystem Role: How does the podcast support digiNEB’s goal of creating a unified digital ecosystem?

It’s important to realise that unity is not monolithic, and a digital ecosystem is not a megaphone or just a collection of practical tools. A NEB digital ecosystem needs to reflect the community’s diversity of voices and perspectives. A podcast provides the opportunity to reflect that diversity, reveal the very human ways in which we converge, and share knowledge in a personal and approachable way. The human voice, especially when speaking about something that deeply matters, is a powerful communication tool. The podcast leverages aspects of digital technology to provide a wonderful means of knowledge exchange within the community. It is complementary to other methods, adding richness rather than replacing other forms of content or distribution methods.

Best Practices: How do you showcase innovation best practices through the podcast, and what themes resonate most?

As an interviewer, the best way to showcase innovation best practices is to lean into the expert’s enthusiasms. People are animated by the things they do that have meaning and impact. By asking them to speak about what they find important and meaningful about their work, you will inevitably come to best practices.

There is a wide range of topics that come up in the series, but the NEB values shine through – not as adherence to policy, but as shared (or significantly overlapping) personal value systems that prioritise sustainability, inclusion and aesthetics. The recurring themes throughout the series are about the value of community engagement and participation, the far-reaching impact of NEB thinking and action – even at a small and local scale – and technology’s affordances, opportunities and challenges we need to consider, not only from a technical perspective but also from a cultural and ecosystemic one.

Outcomes: What have been the podcast’s most significant results so far? How do you measure its impact?

I would say that the podcast’s biggest potential impact is its integration into curricula and the pedagogical material for the NEB Academy, so that these expert voices can reach the next generation of architects, designers and planners whose work will shape the world and our experience of it. That said, one of the more significant impacts is the NEB community getting to know itself better. The podcast helps people learn about the human beings behind the ideas and feel like they get to know that expert as a person. This is what builds the NEB ecosystem as a community and not just a group of individuals independently working on the same sorts of problems. How you measure impact is the same way you might measure the impact of a conversation – not with numeric KPIs, but by observing what happens, what lessons are applied and what ideas filter through to the community and become part of the culture.

Advice: What tips would you give to others using podcasts for knowledge sharing and innovation transfer?

As a broadcaster, I would want my advice here to be technical or professional in nature. While it’s true that anyone can start a podcast and that far more projects should include them for knowledge exchange, dissemination and community building, it is – like all other communication forms – also a skill with technical and performative dimensions that are learned and practised. Anyone can start a podcast, but nobody should have to listen to bad ones. Good sound matters. Editing matters. Being interesting matters.

Asking open questions is essential, as is listening to the answers and asking further questions based on them. Far too many people go into an interview with just a list of questions they tick off when asked. Still more simply say whatever comes into their head without any preparation, and the interview has no shape, destination or purpose.

The most important thing, perhaps, is positioning. You need to assume your listener has a level of intelligence but not that they have deep specialist knowledge. And then you need not to be afraid to ask what might seem to be stupid questions to get the kinds of answers that genuinely convey the lessons that you are there to uncover.

Key Learnings: What lessons have you learned about the role of podcasts in advancing NEB’s goals?

What these podcasts have revealed is precisely what you might expect: that the NEB community is full of intelligent, creative and interesting people who have good ideas and incredibly strong values. I believe the best way to advance NEB’s goals is to bring that community together and work collectively. Getting to know each other, and listening to a podcast that makes you think, “I really like what this person is saying, and they sound like someone I would love to work with” – that’s a fantastic start.

The post NEB Concepts podcast first appeared on Dubber.February 20, 2024

Masterclass: Emerging technologies in independent music

Last year, I was invited to speak at an event in Portugal about the (potential) impact of AI and other emerging technologies on the independent music sector. I delivered a whole-day masterclass divided into two parts and participated in an evening panel session. It was part of a two-week intensive course covering a wide range of industry issues for creative people in the independent sector, and musicians, producers, label owners and promoters from all around the world attended.

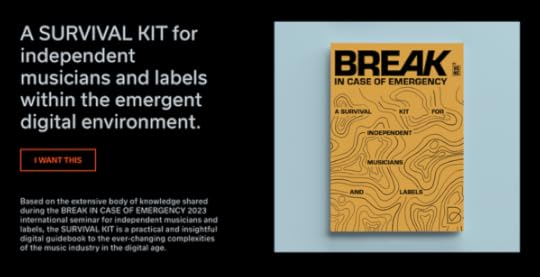

The whole series of masterclasses and workshops has now been turned into a free ebook called the Survival Kit – and it has a lot of brilliant advice and insight for people in independent music, wherever they are in their journey. A lot of good advice from a lot of smart and experienced people has been rather expertly distilled into this book.

What follows below is the Survival Kit’s summary of my own contribution. If any of this is of interest, I strongly recommend the whole thing, which you can download here. It also contains links to videos of the Masterclasses.

Emerging technologies in independent music

Notes on the Masterclass by Andrew Dubber

Technology has always played a crucial role in the evolving tapestry of the music industry. Drawing on his vast experience and diverse expertise, Andrew Dubber invites us into a rather philosophical discussion of some of the most pressing issues at the crossroads of music and emerging technologies.

Director of MTF Labs and a respected figure in the music tech sphere, Dubber has dedicated over four decades of his life to the industry. His journey began in the era of radio and record production, and he has since witnessed first-hand the seismic shifts brought about by technology. As an academic, Dubber has delved deeply into the social and cultural impact of media objects. His extensive body of work, which includes notable publications such as “Radio in the Digital Age” and “Music In The Digital Age”, reflects his thought leadership and depth of understanding.

Dubber’s age, by his own jovial admission, makes him a veteran in the field and grants him the privilege of perspective. He has seen the meteoric rise and sobering fall of various trends and technologies. But his core message remains unchanged: music as a medium has the power to transcend boundaries, heal divisions and drive social innovation.

In this masterclass, participants are invited to embark on an insightful journey through the contemporary technological landscape of the music industry. Starting with the concept of the ‘musical metaverse’, Dubber sets the context of our current technological environment. From there, he delves into the nuances of Distributed Ledger Technologies (DLTs) and Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs), exploring both their potential and their pitfalls.

These new-age technologies promise unprecedented transparency and opportunity but also come with their own set of challenges. Artificial Intelligence (AI) will also be addressed, not only as a tool for automation but also as a collaborator, composer and even critic in the music world. The fields of virtual reality (VR) and gaming are explored, providing insights into their transformative impact on live performances and fan experiences.

Beyond theoretical knowledge, this masterclass is designed to equip participants with practical tools and best practices to ensure they can effectively navigate this dynamic landscape, gain a panoramic view of the current music-tech interface and discern the horizons of future possibilities. In a world where technology can often seem like a double-edged sword, Dubber’s masterclass aims to equip, enlighten and inspire individuals to harness its power for creative innovation, social change and, above all, the love of music.

The Intersection of music and technology

The music industry has always been at the forefront of technological evolution. From the early days of the phonograph to the modern era of digital streaming, technology has consistently transformed the way we produce, distribute and consume music. This dynamic interplay between music and technology has led to ground-breaking shifts in the industry, opening up new avenues for both artists and their audiences.

While technology offers a plethora of tools and platforms, Dubber emphasises that it’s the human spirit, our innate creativity, that truly drives innovation. Music is not simply a collection of notes and rhythms – it’s a profound form of expression, a universal language that resonates across borders and cultures. Technology, on the other hand, serves as a conduit to amplify, distribute and innovate this art form.

However, the rapid advancement of technology, especially in the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI), requires a comprehensive understanding and skilful navigation. With tools like ChatGPT, what began as a rudimentary browser tool has now evolved into a sophisticated mobile application.

With the introduction of platforms such as Google’s BARD, the AI landscape in music is becoming richer and more complex. Dubber draws parallels between the current wave of AI in music and the transformative impact of platforms like Napster in the late 1990s. Just as the industry adapted to the digital distribution era, it is now on the cusp of another transformative phase with AI. The challenge and opportunity lies in the understanding and harnessing of this potential.

To truly thrive in this new landscape, artists and industry professionals should remain strongly anchored to their core motivations. What drives you? Is it the applause of an audience, the tangible metrics of streams and revenue, the deep satisfaction of creative expression, or the profound impact music has on your listeners? Defining these metrics of success can help you approach the technological landscape with clarity and purpose. In this vast technological realm, not every technology tool or platform will resonate with everyone’s unique needs. Some may be perfectly aligned with individual objectives, while others may be mere distractions. The challenge is to sift through the noise, adopt the technologies that truly align with your vision, and set aside those that do not.

The evolution of AI and its impact on music

Artificial Intelligence, with its unrivalled capacity to process vast amounts of data and recognise patterns, has carved out a significant niche in the music industry. One of the most intriguing applications of AI in music is its ability to generate compositions.

Songs created by AI in the style of iconic artists may sound remarkably authentic, but they also spark a series of debates and discussions. Can a machine-generated composition evoke the same emotions as a song written by a human? What does this mean for copyright and artist recognition?

AI vocal replacements also quickly became a thing, with famous examples such as AI Rihanna singing a Beyoncé song, AI Kanye West doing “Hey There Delilah”, or AI Kurt Cobain singing Soundgarden’s “Black Hole Sun” in post-mortem ecstasy. Or the track “Heart on My Sleeve”, which used AI versions of Drake and The Weeknd’s voices to create a “passable mimicry” that racked up millions of plays on TikTok, Spotify, YouTube and more before being removed by Universal Music.

While impressive, this technological marvel comes with its own set of challenges. The potential dilution of original works and the ethical considerations of replacing human voices with AI-generated ones are topics of intense debate.

The rapid advances of AI in music also bring challenges. Dubber highlights the significance of communication in AI and reflects on the potential for computers to “feel” with the right sensors. He draws parallels with the human brain, suggesting the profound implications of advances in human-AI interactions. At its core, music is a form of expression, a universal language that resonates with audiences around the world. Does the essence of music remain deeply human despite rapid technological progress? While technology can enhance and amplify that expression, can it replace the human touch, emotion and story that artists bring to their creations? If a song sounds good and makes you feel something, does it really matter if it was created by a human or by AI alone?

But it’s not just the creation aspect of music that AI is impacting. AI tools are being integrated into existing workflows and software, optimising processes and offering new solutions. From mastering tracks to curating playlists and even predicting music trends, AI’s footprint in the music industry is growing exponentially, and its potential to help with boring or tedious day-to-day tasks in related fields is becoming more evident every day, with examples including voice cleaning and background noise removal, automatic subtitling, automated multi-camera automatic video editing or writing web copy, among many others.

On the other hand, the way in which these technological advances are managed and dealt with raises deep concerns and challenges. AI companies are rapidly releasing their work to the public, rather than safely testing it over time – for example, AI chatbots have been added to platforms used by children, such as Snapchat. Safety researchers are in short supply, while most research is driven by profit rather than academia. The media has also failed to report on AI advances in a way that allows us to truly understand what is at stake. Corporations are in an arms race to deploy their new technologies and gain market dominance as quickly as possible. In turn, the narratives they present are shaped to be more about innovation and less about potential threats.

The misalignment caused by broken business models derived from social media that encourage maximum engagement has yet to be fixed. Large Language Models (LLM) are humanity’s ‘second contact’ moment, and we are about to make the same mistakes. In fact, half of AI researchers believe there is a 10% or greater chance that humans will become extinct due to their inability to control AI.

Every time we create a new technology, we uncover a new class of responsibility, and if that technology confers power, it will eventually start a race. Either we coordinate this very carefully, or the race may very well end in tragedy.

Embracing new technologies: streaming, blockchain and NFTs

The digital age has ushered in a plethora of technologies that have had a significant impact on the music industry. Furthermore, these emerging technologies are not just tools but actual environments that we inhabit, shaping our perceptions, experiences and interactions in profound ways.

Dubber discusses the concept of ‘affordances’, suggesting that technologies offer possibilities that can be harnessed creatively. He draws parallels with the music industry, citing seminal albums such as “Sgt. Pepper’s” and “OK Computer”. These works are still celebrated not only for their musical genius, but also for their innovative use of technology, pushing the boundaries of what was thought possible at the time.

More recently, streaming platforms have democratised access to music, allowing artists to reach a global audience without the traditional gatekeepers. Platforms such as Spotify, Apple Music and SoundCloud have revolutionised music distribution, but they also pose challenges.

The debate over fair compensation for artists and the role of algorithms in curating music experiences are at the heart of the streaming discourse. Blockchain technology was a hot topic in 2016, promising transparency and decentralisation. Dubber recounts an enlightening event at MTF, where a diverse group of experts, from cryptographers to composers, gathered to dissect blockchain’s potential in the music field. The burning question was its ability to make music more equitable. Could blockchain actually ensure fairer remuneration for artists?

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) have also recently gained significant attention in the art and music worlds. Although there are a myriad of challenges associated with music DLTs (distributed ledger technologies) – spanning ethical, technological, political and business domains – the potential benefits of these unique digital assets, verified using blockchain technology, are also immense, as NFTs can be structured to ensure artists receive a percentage of resale profits, while providing proof of authenticity and ownership. Dubber discusses the potential of NFTs in creating unique, limited edition digital assets, but also touches on the criticisms and environmental concerns associated with them.

Beyond the nuts and bolts of these technologies, part of their broader implications stem from the fact that they are not external entities but integral parts of our environment. They influence how we perceive the world, how we communicate and how we express ourselves. According to Dubber, the impact of these technologies – both positive and negative – depends more on the people who use them than on the technologies themselves. In the confluence of creativity and technology, it is important to understand both the potential of tools like blockchain and NFTs, as well as the challenges and ethical dilemmas they pose.

Rise of the metaverse: virtual reality and gaming in music

The metaverse, virtual reality and gaming have become integral parts of the modern music landscape, offering new ways for artists to engage with fans and create immersive experiences. These technologies are not just tools but environments that we inhabit, influencing how we perceive, experience and communicate within the world.

While VR’s roots go back decades, its intersection with music is particularly fascinating. While some predicted the metaverse would be the next big thing, recent narratives suggest its premature demise.

Nevertheless, the potential of the metaverse for live performances, fan engagement and immersive experiences remains huge. Gaming in particular offers a unique overlap with music. The emotional experiences that gamers have while playing, whether it be the thrill of solving a puzzle or the adrenaline rush of an action sequence, are often accompanied by music. This music becomes an integral part of the gaming experience, leading to a heightened emotional connection.

Players often want to own the music from their favourite games, leading to phenomena such as vinyl sales of indie game soundtracks. One notable example is the DJ Marshmello concert within the game Fortnite. This event was monumental, with millions of people attending a 20-minute virtual gig, making it one of the largest concerts in history. Such events highlight the potential of virtual concerts within gaming platforms.

Another interesting development was the acquisition of Bandcamp by Epic Games (the developers of Fortnite). Bandcamp, an online platform where artists can sell their music directly to fans, has been a favourite among independent artists. Its acquisition by Epic Games, a major player in the gaming industry, points to the potential synergies between music and gaming. This merger underscores the evolving landscape of the music industry, where platforms like Bandcamp can benefit from the vast user base and technological prowess of gaming giants like Epic Games.

Dubber’s mention of this acquisition underscores the importance of understanding these industry shifts and the opportunities they present.

The rise of the metaverse, virtual reality and gaming in music presents a plethora of opportunities and challenges. From creating immersive fan experiences to exploring new revenue streams, these technologies are reshaping the music industry. But while the idea of inhabiting virtual spaces – from VR goggles to potential contact lenses – is intriguing, the excessive excitement about the actual impact of such technologies – such as Facebook’s rebranding as “Meta” and Mark Zuckerberg’s vision of a virtual world where people socialise and play together – should also be met with a fair share of scepticism. As with all innovations, it is important to approach them with a balance of enthusiasm and critical analysis.

Strategies for independent musicians and labels

Defining value is a crucial debate and reflection, and artists should challenge the traditional notion that the value of music is tied solely to its price. Dubber emphasises the importance of artistic creation, expression and the intrinsic value of music beyond monetary terms. Changes in the industry, particularly with the advent of streaming and digital platforms, require a re-evaluation of how the value of music is perceived and monetised.

Integrating emerging technologies into existing workflows can be daunting. The key is to understand your goals and tailor the technology to meet them. For example, while VR concerts may be all the rage, they may not suit every artist or genre. Similarly, while NFTs have made headlines, they may not suit every artist’s ethos or brand. It’s about identifying which technologies and strategies resonate with your artistic vision and your audience. For independent musicians and labels, understanding and leveraging emerging technologies is crucial.

While the major record labels have traditionally wielded considerable influence, Dubber aptly points out that they are not the whole of the music industry. Using the analogy of lions in a zoo, he points out that while they may be the loudest and have the sharpest teeth, they’re not the only game in town. Independent musicians and labels have always been the lifeblood of the music industry, often at the forefront of innovation and experimentation.

In today’s landscape, they have the opportunity to redefine industry norms by embracing new technologies, understanding the nuances of different platforms and staying true to their artistic vision.

Another interesting perspective Dubber presents is the idea of spending less in the music industry. Rather than focusing solely on increasing revenues, artists and labels should also consider strategies to reduce costs. This could include re-evaluating deals with merchandisers, optimising distribution channels or using direct-to-fan platforms to maximise revenue.

The journey for independent musicians and labels in today’s music industry is full of challenges and opportunities. Redefining value and ensuring cost efficiency are not only strategic imperatives, but essential for survival and growth. By understanding their unique strengths, leveraging the right tools and platforms, and making informed decisions, independent artists and labels can better navigate the complexities of the industry.

Conclusion and future outlook

A recurring theme throughout the masterclass is the idea of agency. Dubber emphasises: “So it is still up to us. We are still the ones who decide. This notion underscores the importance of human agency in the face of rapid technological advances. While technology provides tools and platforms, it is the choices made by artists, industry stakeholders and audiences that will shape the future of music. He shares an anecdote from a keynote speech he attended in Dublin, where a self-styled futurist made bold predictions about the future of music. This reflection serves as a cautionary tale about the pitfalls of deterministic views. One should always question the idea that “in the future, we will all be…” and be mindful of the diversity and individuality inherent in human choices and actions.

More than ever, it is essential to connect with like-minded people — not just industry insiders, but technologists, fans and other stakeholders — to share insights and build community. These human connections are critical to navigating the complex landscape of music and technology.

Artists should embrace an open perspective, engage in discussion and remain curious. By fostering a mindset of continuous learning,exploration, adaptability, open dialogue and a balanced approach, we can better navigate the challenges and opportunities presented by new technologies.

From the rudimentary recording devices of the past to the sophisticated AI-driven tools of today, the pace of technological advancement is exponential, with each leap expanding the horizons of what’s possible.

The integration of blockchain, the rise of NFTs, the allure of the metaverse and the convergence of music and gaming are not just trends, but indicative of a broader shift. They signal a future where technology and music are inextricably intertwined, creating unprecedented opportunities for artists, labels and fans. But with these opportunities come challenges, and the industry must learn how to navigate this landscape wisely, ensuring that technology serves the art, not the other way around.

As we stand at the crossroads and look to the future of music, it’s clear that technology will continue to play a pivotal role. It may sound clichéd, but the fact that change is the only constant is particularly true in the music industry. The digital revolution, the rise of streaming, the democratisation of music production – each of these changes has been met with apprehension, scepticism and even resistance. Those who embrace these changes, who see them not as threats but as opportunities, are the ones who thrive. The future will undoubtedly bring more change, some predictable, some unforeseen. The key is to embrace these changes, understand their implications and harness their potential.

However, technology is not an end in itself, but a means to an end. The heart of music lies in its ability to evoke emotion, tell stories and connect people. As we integrate new technologies and explore the vast possibilities they offer, let’s not lose sight of that essence, while ensuring that technology amplifies art, enhances human connection and serves the greater good of the community.

You’ve read this far? You should check out the rest of the masterclasses with full videos, downloadable materials and workshop summaries from the free BREAK in Case of Emergency Survival Kit.

The post Masterclass: Emerging technologies in independent music first appeared on Dubber.September 2, 2023

Please Feed The Bear

Recently, I’ve been watching, as no doubt have you because absolutely everyone seems to be, the FX series The Bear on Disney+. If you’re anything close to representative of the broad sector of society that can be described as televisually inclined, then you’ve already finished Season Two and have moved on, satisfied, awaiting a third helping. You may have even posted about it on the platform currently known as The Platform Formerly Known As.

I’ve finished Season One (eight episodes in three consecutive days), and am just starting the second series now.

The reason I’ve lagged somewhat is probably fear. Or, I suppose, strong, visceral aversion, which amounts to the same thing. Not of bears (I understood that the title did not refer to a literal bear, though that is precisely what we see the protagonist confront right at the start of the first episode), or indeed programmes about cooking (which, at least on paper, is what this is), but of television more broadly – or rather, British and American television.

To be blunt, most (so called) Quality Television, the like of which you will often find on HBO, but extending to much of the BBC and ITV dramatic output, is something I will tend to avoid as a matter of course.

There has, for some time, been something of a toxicity arms race in US/UK TV narrative and character. I would not necessarily blame The Sopranos for this, though that, I think, was probably ground zero. It was the moment when the overarching cultural agenda seemed to shift away from heroes and villains, challenges and solutions, and instead become about filling the world’s living rooms with people you would not invite into your house, and then causing them no end of torment.

Now, I can stomach a bit of violence. Not horror or gore, necessarily and the penultimate episode of the first season of Punisher really tested my threshold on that front (I loved season one despite my intense discomfort at the carousel scene), but I do like a shooty, fighty, chasey progamme with explosions and a good bit of peril.

The Venn Diagram intersection of shooty, fighty, chasey with exceptional writing, strong characters, good acting and quality production is slim at best, but there are examples of it.

Usually, though, these programmes consist of characters taking turns explaining the plot, then fighting. Not ideal, but I’ll take it if they just clear the low bar of being fun while they are at it. If my eye-rolling becomes so pronounced it’s audible (as it did with Citadel), then I will abandon ship, but otherwise just keep up the momentum and make me smile occasionally.

There is also, an extremely popular and therefore ubiquitous category of programmes (can we call it a genre?) in which irredeemably horrible people have an entirely miserable time. I place Breaking Bad, Game of Thrones, Sons of Anarchy and Succession all in this group – not because I have watched the whole of any of them and made an objective assessment based on that, but because I have started and, usually, very quickly stopped watching. Nothing has yet contradicted my suspicions about them. This is not how I want to spend my time.

I also have a fairly low tolerance for depictions of situations designed to cause stress, tension, anxiety or upset to the viewer and not just to a selection of the characters. A thriller should thrill, not traumatise.

A middle ground might be represented by something like Fargo, in which a broadly likeable person finds themselves dragged deeper and deeper into a more ‘real’ world in which it turns out that everyone is horrible, nothing is fair and very little really matters. Fargo had its moments, but ultimately kindness is portrayed as naive and quaint. A curiosity rather than a quality.

Or perhaps Peaky Blinders, which was kind of retro not just in terms of its setting, but in the sense that it portrayed ostensibly likeable antiheroes. I mean, there were no actual ‘goodies’ in that show, but you were never unsure about who you wanted to win and, spoiler alert, you were ultimately not disappointed. I loved it, despite its ultimate bleakness, perhaps because it had more in common with, say, Raiders of the Lost Ark or a classic caper film than something like Breaking Bad, in that the denouement of each series results in cheers, rather than a need for a shower and perhaps a Roadrunner cartoon or two to take the taste away.

There’s a variety of narrative arcs and worldviews at work in these post-Sopranos prestige shows, of course. They would fail to register as good writing and great production if we were just to wallow about in a mire of misanthropy and psychosis without tight scripting, propulsive and compelling plots and masterful delivery. Quality television offers up all the very best in classic tragedy, revenge, nihilism, Kafka-esqe bleak surrealism, and outright sociopathy.

But those things, as literarily valid and de rigour as they may be, are – to put it mildly – not to my taste. A relentless portrayal of a world that is bad because people are bad, and the cycle will inevitably drag you under.

This outlook is not my bag to the extent that I have now given up starting things just because I heard they were good. I don’t want to take away from anyone else’s ‘enjoyment’, of course (if indeed that is what you call what people get from these shows), but they can have that without me. Please don’t feel I’m missing out by not viewing the Netflix series you’ve been bingeing.

But… and so it was The Bear’s dual critical public discourse (magazines, radio shows, websites, podcasts) which appeared to uniformly agree that on the one hand ‘it’s incredibly stressful – like a panic attack’ and on the other ‘it’s such great television – the writing is incredible’ (such common bedfellows that the assertion of one leads one to assume the presence of the other) that caused me to look elsewhere for entertainment. I’d heard this before and I knew it was not for me.

Until suddenly it was.

I was having brunch with a family member at a café in town – something I rarely get to do – and wondered aloud (because these are the sorts of conversations we sometimes have) whether there was any such thing as a Redemption Arc anymore – either in real life, on social media or in film and television.

“Well yes,” they said, because contradiction is rightly the default position when responding to generalisation.

An example was given of someone who had said something profoundly problematic in a public forum and was immediately sent, presumably permanently, to the online naughty step. However, this person had achieved the Herculean accomplishment of working their way back to civil society from exile through a process of humility, meaningful apology, learning and genuine empathy.

And then “oh – and also The Bear.”

The notion that The Bear contained redemption was enough for me to give it a chance. That it was entirely about redemption made it utterly compelling.

This is, to be clear, not what everyone else is getting from the series. Some reviewers come close – talking about the characters learning and growing as the show progresses – but the idea of redemption – even, in some respects, of transcendence – hasn’t, as far as I’ve seen, really come up.

Which is not only fine, but entirely unsurprising. Not everyone is as fixated on the idea that stories about people we at least want to like, and who then become people that we do like for the reason that they become better people – are stories that are not only worth telling – but urgently needed.

The truth is that most people (and therefore society at large) are mean, miserable and myopically self-serving. And the reason for this has been attributed to a lack of institutions, platforms or vehicles for what you might call “moral” education, instruction or modelling. I’m not talking about the kind of morality that forbids progressive kinds of behaviours. Or moral as in puritanical, religious or otherwise holier-than-though. I’m talking about the kind of morality that instils and privileges kindness, and teaches it as a strength.

The obvious recent example is Ted Lasso, in which a coach creates better footballers by inspiring them to become better people. That right there is a morality tale, and as a result, sounds so much more insipid than the brilliant, witty and heartfelt comedy it actually was.

But I think the comedy drama series that comes closest to what (at least Season 1 of) The Bear achieves is Northern Exposure. They are not, in tone, related. But their ultimate effect is the same. And we need much more of that effect in our society if it too is to be redeemed.

I don’t entirely know where The Bear is heading. I get the sense that Season 2 is somewhat less frenetic, perhaps even more reflective – and that will be very welcome. But if the intensity and pace of the programme continues, it is largely the kitchen environment providing the toxicity, and the people who are human and deserving of empathy and grace doing what they can to survive in that environment.

They are working to live, and making food to give – despite all that brings out in them and each other. The context provides the problem, not the individuals. The tragedy of The Bear (Mikey’s suicide) occurs before the show begins. Season 1 works towards the dismantling and rebuilding of the restaurant. It seeks to make a better world. The Bear itself is post-tragedy – and shows a possible path back.

It’s a comedy – not just because it has jokes or funny moments in it. There are plenty of comedies on television that make light of the knowledge that the world is terrible and people are bad. These comedies are resigned to the decline, the funny situations are, on reflection, tragic – and the jokes have victims. The Bear is a comedy in the Shakespearean sense. We know that despite the trials and misunderstandings, things will work out. We have hope. And either figuratively or literally, it’s not over until there’s a wedding – that most symbolic of literary forgiveness, redemption and love.

It’s not entirely alone. I’ve mentioned Ted Lasso. There’s also Reservation Dogs. There is a small but promising handful of programmes that, overtly or otherwise, rightly pinpoint the problem as societal, historical and environmental, rather than an irreversible flaw of humanity we must lean into. These programmes suggest we can change the environment. We can teach and learn. Things can be better.

These shows are not naive. They acknowledge and grapple with tough problems at both the personal and the societal scale. But they do so with what kindness and humanity they can muster. They do so because they have not given up on us.

I hope that the accolades accorded to The Bear help to encourage a new wave of what we might call hopeful media. A movement towards film and television as a vehicle for societal and moral repair. An investment in redemption programming. This is the sort of animal we should absolutely be feeding.

The post Please Feed The Bear first appeared on Dubber.August 16, 2023

Not faulty – just non-standard

In which I enumerate several of my most endearing flaws.

The Haggunennons of Azizatus Three have the most impatient chromosomes of any life-forms in the galaxy. Whereas most races are content to evolve slowly and carefully over thousands of generations – discarding a prehensile toe here, nervously hazarding another nostril there, the Haggunennons would do for Charles Darwin what a squadron of Arcturan Stunt-Apples would have done for Sir Isaac Newton. Their genetic structure, based on the quadruple-striated octo-helix, is so chronically unstable, that far from passing their basic shape onto their children, they will quite frequently evolve several times over lunch. But they do this with such reckless abandon that if, sitting at table, they are unable to reach a coffee spoon, they are liable without a moment’s consideration to mutate into something with far longer arms – but which is probably quite incapable of drinking the coffee. – Douglas Adams: The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Fit the Sixth

I told the graphic designer for our Open Minds Erasmus+ project that we should make the title of this section of the web page the same font as the yellow text in the previous section.

“That text is orange,” he said, with the kind of flat, matter-of-fact tone reserved for people who are clearly being bafflingly stupid, but also pay invoices on time.

“Ah, “ I explain, feeling the need to state the obvious: “I’m actually a bit colourblind.”

“Oh – sorry! I had no idea…”

Not his fault in the least, of course. It’s not like I wear a badge.

And nor, if I’m totally honest, is it even in the top five idiosyncrasies that people might need to accommodate when working with me. It’s a “disability” in more or less the same way that the fact I cook poached eggs quite consistently well is a superpower.

Honestly, daltonism (as I’ve discovered it’s called) is not even the worst of my visual issues, though I imagine it likely contributes to things like poor night vision, failing to see small pieces of broken glassware on polished concrete kitchen floors and not always being able to tell when my iPad screen is smudgy.

And yet, on paper, I have pretty good eyesight. I mean, I wear glasses – but the correction level on them, while necessary for critical tasks like driving or identifying small letters on optometry charts, is pretty slight as these things go.

The fact that the text on my iPhone is now set to a chunky font size and that I use varifocals on a day to day basis is simply a testament to the fact that I am 55 years old, and with that comes a degree of expected wear and tear. Broadly speaking, I function ‘properly’ in most physical respects.

Basically, what I’m saying is that my eyes are (relatively) fine, but that isn’t always enough. The main problem with my vision lies not with my eyes, but behind them.

I’m okay at seeing, not so great at looking and pretty terrible at picturing.

Let me give you a couple of examples.

Example 1: Let’s say you and I are face to face in the same room chatting for a couple of hours. Perhaps over a coffee. Then you get up and go to the bathroom. Once you are out of sight, another person joins me and asks who was just here. I tell them the correct answer.

“Oh, what do they look like?”

Not a clue. I could easily recognise you of course, but I can’t “see” you if you’re not there and I think, as a result, I don’t really have any language to usefully describe you.

“Tall? Short? Blonde? Dark? Glasses? Beard?”

I have hunches that feel intuitively correct, but I certainly wouldn’t put money on them.

“Okay, but so what were they wearing?”

I try to imagine clothes. Some sort of shirt I guess. It has a colour, though I couldn’t really tell you which. Wasn’t there a hat of some sort? I’m not 100%.

And back you come from the bathroom looking exactly as you did before you left. The sight of you is not new information exactly, but it’s not information I can retrieve without having it in front of me.

Example 2: Putting information into a graphical format prevents me from understanding it.

The kinds of diagrams, infographics, pictorial layouts and charts that most people use to present complex information in an easily digestible form might as well be hieroglyphics.

I don’t think this is just my inability to process visual data. I believe that most infographics, when interrogated with rigour, do actually turn out to have been obscuring and, more often than not, misinterpreting meaning.

I think it’s just that other people are satisfied by an image. Which is not to say they merely pretend to understand, but that their understanding is impressionistic rather than logical or sequential.

It’s that impressionistic understanding I don’t have access to.

So even when the size, shape, colour or direction of the elements within a graphic make no literal sense and fail to map in any coherent way onto the thing that they purport to represent, people will still collectively“get” it. Other people, that is. There will be a shared, unspoken, agreed interpretation of that pretty but ultimately (to me) informationless cryptogram.

Tell me something, and I’ll usually understand. Draw me a diagram, and you might as well have done an interpretive dance while juggling bees. In a completely different building.

I have similar issues with hearing, but in many ways, my auditory world is both infinitely better and also very much worse.

So, I have no deafness or hearing loss to speak of. Things are just as loud as they have always been, and, if anything, my high frequency hearing is at the upper end of the bell curve for people my age. Given the tens of thousands of hours I have spent around musicians, in recording studios, at concerts, in clubs and wearing headphones, I seem to have come away relatively unscathed so far.

Which is, of course, a good thing, because pretty much my favourite of all the pastimes is to listen to music.

Also, throughout my life, my ears have been an immense asset, both personally and professionally. But they have also been quite possibly my greatest sensory impediment.

It comes down to both biology and physics: my ears stick out. Not just a little bit, but substantially more than most people.

Apart from the aesthetics of this, something I long since came to terms with (this is just what I look like and as long as you don’t spend too much time pointing and laughing, I’m happy enough with that outcome), it means that my hearing is very directional. Useful, right?

I have two finely-tuned parabolic dishes, positioned precisely head-width apart, that collect and funnel sound into the space between with great accuracy and in very high quality.

This means that I can locate the point source of a sound’s origin, orientate myself in a reverberant space and, I imagine, enjoy the spatial and textural dimensions of stereo recordings and live acoustic music at a level beyond the grasp of most conventionally-eared humans.

However, directional is not omnidirectional. It’s not a 360° deal. In fact, if you’re behind me, I can’t hear you. The noise rejection at the back of my ears is almost as good as the signal collection at the front.

Now, that used to be my most consequential auditory quirk. But it scarcely registers in comparison to what has now become the real issue.

How my brain processes sound – and, in particular, speech – has changed. Over the last five years, the problem has been getting noticeably more pronounced year on year.

I have some difficulty distinguishing and sorting out simultaneous auditory signals, regardless of their spatial positioning. I lack the ability to focus in on just one sound rather than another, or separate foreground signal from background noise. This is especially the case when competing sounds inhabit similar frequency ranges.

This is pretty common, I understand. It’s why I can tell when someone under 30 has mixed the sound on a video or, say, radio commercial. Older people need more headroom between the voice and the music so they can hear the dialogue properly, and younger people can’t even begin to fathom that.

Perhaps as the result of my long career in audio, I am more sensitive to the phenomenon and its effects. Perhaps I have it worse than other people. But the upshot of this is that two or more people speaking at once just becomes sonic soup.

To explain: If you’re talking to me and another person also starts speaking, I can’t hear either of you. This isn’t just an irritation. I find it quite stressful, and simply trying harder to follow what’s being said just increases the stress without improving the result.

Worst of all for me are cocktail parties, after-work drinks or pretty much any ‘gathering’ at all. Put 100 people in a room with terrible acoustics and give them all champagne and canapés and the first thing I’ll do is make it 99 people. I can’t deal with it at all.

Not that it was ever in my top one thousand favourite activities, but I’ve now lost whatever ability I may once have had to mingle. When you consider that my main job is putting (admittedly brilliant) people in a room together for whole weeks at a time, you have to wonder about some of my choices.

And while it’s obviously about sound, it’s really not about hearing. This is very clearly a psychological phenomenon. I know this because as the experience intensifies, I become more overwhelmed, then fairly quickly distressed.

I enjoy a room full of people networking about as much as I would enjoy that same number of people simultaneously shouting at me for ruining their Christmas. Inevitably, I have to leave, go sit somewhere quietly and just breathe.

Okay, so before you attempt to diagnose this as some sort of condition or disorder, or place me on a spectrum of some kind so as to name and therefore helpfully address and assist in mitigating the issue, consider the following: it’s entirely possible that a) I may have done this to myself, and b) that it is merely the unfortunate but ultimately minor negative side effect of a different and otherwise wholly positive psychological adaptation.

Which is that I’ve become good (or at least much better than I was) at listening.

I feel I need to qualify that somehow. It has to do with a combination of things, some of which I’ve worked on deliberately, others are by-products of what I’ve spent the last 40 years (and especially the last 10) focusing on.

For instance, I often notice that I’m using interviewing techniques in conversations. I’ve long been interested in what makes a good interview anyway and I used to teach the skill, both at university and at radio stations. But now I appear to have adopted the practice in everyday conversation – and I have much better conversations as a result. Interviewing is often less about asking questions than it is about listening to the answers.

Generally speaking, unless your role is to give instruction or provide a briefing, the aim would be to speak for less than half the duration of the conversation.

Also, I quite often find that I’m the only person in the room who followed the dialogue in a tv show or film where it appears to have washed over other people. This is particularly true when strong accents are at play. Others might pick up gist but not detail. I can usually tell you what was said – and I expect that has something to do with years of dialogue editing, which, of all the things I could be said to have some skill at, is probably my strongest suit.

It also might come from 10 years in Birmingham – which not only has a characteristic regional accent that some find difficult to decipher, but is also home to many other accents that your typical South Birmingham resident will encounter daily. And also, now that I think of it – my family tree has roots in Glasgow, notoriously one of the more impenetrable accents in the English language and adjacent dialects.

But perhaps most significant is the fact that speech is now the main way in which I consume information. A few podcasts, of course. But far more narrated long form articles, audiobooks and AI text-to-speech readings of pretty much any document that comes my way. Hours of listening, every day, at every spare moment.

We’re not talking about the Stephen Hawking style text-to-speech you might be thinking of either. AI narration has come a very long way in the past couple of years. Check out Speechify, for instance. Other than the fact that nobody ever seems to take a breath and there are some odd inflections, strangely-placed pauses and unusual emphasis choices, it’s often quite hard to distinguish some of the AI voices from real people.

But all this is just to say: I listen deliberately. I focus. I value and process what is being said. I don’t always remember everything and that’s a whole other thing, but generally, I am a listener.

What I can’t do is just sort of dip in and out – or skim as you might do with printed text. I can’t have speech radio on in the background. I need to take in every word like beads on a string. And I certainly can’t multitask, I can’t listen to a podcast and read email at the same time. I would suspect anyone who said they could of being a liar (and quite possibly a murderer).

There is nothing impressionistic or secondary about it for me. If I’m listening, I am LISTENING. And if there’s interruption, cross-talk or competing sound, my brain interprets it as static. Interference. As a threat.

So, speaking while I’m listening to something or someone is a little like dancing in front of the TV while I’m trying to watch a film. The problem is not that I ‘fail’ to simultaneously process the dancing as well as the movie – or, indeed, that I’m “bad at watching”. It’s just that I can no longer sufficiently appreciate either the film or the dance – either of which I may well have enjoyed properly if presented separately.

This is fine. I’m certainly not getting the sense that I’m missing out. I don’t particularly wish that I could tolerate noisy social gatherings any more than I wish I could eat more avocados (I happen not to like avocados very much and so not eating them is no hardship… though guacamole is a different story, where the avocado is a perfect vehicle for other, much more interesting flavours – I digress).

In other words, to draw a parallel with the Haggunennons of Azizatus Three: I may not be able to drink the coffee, but I have at least developed far longer arms.

We see things differently. We hear things differently. We think differently and move about differently.

Sometimes the context or environment makes that a problem. But it’s generally the environment that is the source of the problem. At the very least – it certainly seems like a much simpler task to try to address the problem at the level of the environment than it might be to try and standardise the person.

Because these minor non-disability disabilities that I experience from time to time – misidentifying orange text or having to excuse myself when a conference coffee break becomes intolerable – they help me understand a little better the need for radically-inclusive design.

Which is handy, because that’s actually what I’m working on. It’s what that Open Minds Erasmus+ project I mentioned up top is all about.

We all have physical and psychological differences. Cultural and historical ones too. Most technologies, buildings, systems, practices and environments are constructed as if we don’t. Or as if the people that they happen to exclude don’t particularly matter. But we can build all of these things differently if we choose to. Hence the project.

It’s not my experience of the world that led to Open Minds (at least not consciously), but more that my involvement in Open Minds has helped me better understand and contextualise both my experience of the world and the ways in which other people’s may reveal our inherent differences in different contexts and in sometimes non-obvious ways.

That said, there’s certainly no need to go around changing the built environment for my specific benefit – and there are presumably some things that I could actually improve through effort. If there was a ‘cure’ for mild colourblindness or auditory overwhelm, I’d probably consider it – though I’d far rather you spent your research funding on cancer or ALS or something.

I’m not demanding that the universe be customised to my needs. But as a general rule of thumb, it seems far better to standardise the accommodation of differences in all contexts than it might be to try and fix the faults you might encounter in people like me.

I raise them here not to make you aware of my own idiosyncracies and foibles, but perhaps as a reminder that this is absolutely the least of it, and we never have any idea what things other people might be having difficulty with – physically, emotionally, psychologically or otherwise.

So, I don’t know – be kind, I guess?

The post Not faulty – just non-standard first appeared on Dubber.

August 6, 2023

Thoughts, fully formed

Elon Musk has ruined social media, but I might also be partly to blame.

Writing on the internet, for me, began with bulletin boards in the early to mid 1990s. I progressed fairly quickly to Usenet, gravitating toward rec.radio.broadcasting and meeting some people there with whom I seemed to share not just a common interest, but also sense of humour and, broadly speaking, outlook.

Before long, I was spending time in what Howard Rheingold called “Virtual Communities”. In fact, after dabbling in The WELL for a bit, it was a new community of Rheingold’s that I joined: Brainstorms. It was 1998. I had to apply and it required some sort of consensus approval of my credentials, which were fairly limited, but with a little minor embellishment (slight exaggerations rather than outright falsehoods), they appeared to do the trick.

The classic New Yorker cartoon truism applied: “On the Internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.”

Once I successfully passed as ‘the right sort’, I began to get a sense of the kinds of social behaviours that were acceptable or expected. And while I hadn’t thought of it this way until very recently, it was here I learned how I liked to be ‘on social media’ (though virtual communities and social networks do differ in a number of ways). I was chatty, generally sympathetic, watched others for cues and joined in when I thought I got the gist of the running joke or shared cultural reference. There were plenty of good role models for this at that time – and not just an optimism about the kinds of communities that can be formed in this way, but a positive determination.

If a technological social utopia could be formed by force of will alone, we would absolutely not be where we are today. Rheingold’s electric neighbourhood was entirely paved with good intentions.

Around that time, I also started and moderated an email discussion forum in Google Groups called NZ Radio. That kept me entertained and busy for a few years, but as things became somewhat fractious and more often work than fun, I managed to offload it to Paul Kennedy – regular poster, broadly of the same mind and, as keeper of the pop charts, sufficiently tangential to the industry to approach the task of moderation with a degree of impartiality I increasingly lacked.

I started blogging in 2002, if I remember correctly (an increasingly pertinent, though likely redundant, caveat these days). Blogging was different. It wasn’t contributing to themed conversations, but more of a monologue. A soliloquy.

I approached blogging more like the kind of journalism I’d attempted back in my youthful days writing for the likes of Rip It Up, Smash Hits and other music outlets clearly short of talented scribes prepared to exchange prose for vinyl. My style, to the extent that I had one, could be described as conversational, funny enough to make you smile but not actually laugh, fairly unevenly edited, broadly under-researched and only occasionally registering as authoritative to any degree. This was the late 80s and so fortunately, nobody seemed to mind.

I do have a very clear recollection of where I was at the time blogging came into my life and who was, if not responsible, then at least salient and therefore blameable.

Russell Brown had spoken to my third year students that day and was explaining the shift of his Hard News segment from radio feature to what appeared to be some sort of online ‘Dear Diary’.

I was in my 15th floor office of the Faculty of Arts Building on the corner of Queen Street and Mayoral Drive in Auckland City, overlooking the Central Library, Art Gallery and the adjacent lower slopes of Albert Park. I was Degree Leader for Radio in the School of Communication Studies and, unlike during my later and more senior academic posts, I had the privilege of a nice view.

I also had a viewpoint and, now, a platform. Like most things that seemed at the time a democratising force, these also probably came more under the banner of privilege.

I effectively exchanged those floor to ceiling windows for Windows 98. The vista seemed more expansive. I started on Blogspot as The Wireless – and years later, I migrated to my own name domain.

Fast forward to 2005. Now in the UK, I started New Music Strategies – a separate and more active blog dedicated to helping independent musicians, labels and other music industry types operating under their own steam and dealing with the realities of a post-Napster world.

New Music Strategies provided me with a space to try out the ideas I was experimenting with in the academic domain, but in a way that could actually be useful to someone. It was there I composed the Twenty Things You Must Know About Music Online as a series of posts. I compiled them into a free ebook that was the closest I’ve ever come to “going viral”. CD Baby’s Derek Sivers got his hands on it, and gave it to all 50-odd thousand active members of the site. It spread from there – and closest estimates had it at around half a million downloads by the end of 2008.

I never made money from blogging, but I certainly made some money and had experiences I could not otherwise have afforded because of it. I started getting invited to speak at music industry events: at first around the UK, then further afield. Blogging took me to Chicago, New York, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Marseilles, Genova… and contributed to adventures in Brazil, India, Colombia, Venezuela, Uganda and beyond.

Everywhere I went, people were encouraged or inclined to read the blog (a far less niche activity than it is today) and, from there, download the ebook.

Perhaps most significantly, 20 Things somehow ended up on the San Francisco desktop of Ethan Diamond, who was in the process of establishing Bandcamp. He got in touch and we started working together. Long story short, that ended well.

In addition to starting New Music Strategies, 2005 was also the year I recorded my first podcast, ostensibly as a piece of practice-based research, though perhaps in reality more an exercise in self-amusement (this was something of a hallmark of my academic career and I exploited the overlap between ‘things I enjoy’ and ‘things that count as work’ even more than is typical of those who populate the domain of Media Studies). Having moved to Birmingham the year before, I teamed up with an equally curious and even more successfully authority-shy and protocol-averse colleague to test the nascent audio distribution waters.

Dubber and Spoons Take The Bus was exactly what it sounded like. James Debenham (‘Spoonford’ or ‘Spoons’ on various online forums at the time) and I lived on the south side of the city in Moseley. Our employer, the University of Central England, was on the north side in Perry Barr. We entertained ourselves with deliberately and self-consciously inane conversations on the two-bus journey home from work. North to City, City to South.

Podcasting involved recording some of those dialogues using the most rudimentary of early portable mp3 devices, and putting the resulting file, more or less unedited, up on the internet.

There was certainly nothing that could have been considered remotely ‘radiophonic’ about the production. There were some technical elements that involved a little HTML coding and I remember there being much discussion of RSS enclosures. In fact, I believe that those discussions formed a significant part of the content of the ‘show’. To loosely paraphrase McLuhan, the content of any new medium is two or more men talking at length about the mechanics of that medium.

“Podcasting is not a category of content, it is a method of distribution,” we insisted.

The Buscast was approximately as good and as bad as you could expect something like that to be (that is, not especially). We garnered something of a following, achieved a mention in the Guardian newspaper as an early example of podcasting (a “top 9”, which suggests they couldn’t actually find a tenth) – and we were covered in an “and finally…” local BBC TV news report.

As usually happens with these sorts of ‘fun at the time’ ventures, we eventually ran out of steam. Much of the podcast series remains online, thanks to James, now based in Australia. It would be nice to think they represented podcasting’s equivalent of the Alan Lomax folkways recordings. Mostly, I think they have, at best, lasting value as historical audio documentation of just how deafeningly rattly West Midlands double decker buses were a couple of decades ago, rather than for any quality informational, techno-historigraphical or entertainment value. Again, my recollection is untrustworthy, but I seem to remember talking about Batman a fair bit.

It wasn’t just podcasting I was messing about with in its earliest incarnation. I was, fairly predictably, a social media early adopter. Tom was my friend, which is to say, I was on MySpace for the entirety of its doomed lifespan and predicted (or perhaps willed) its inevitable demise. Let’s not forget that there is already a pretty high bar when it comes to trashing a popular social platform through billionaire hubris and crushing stupidity.

I was on Facebook fairly early on too – pretty much as soon as it became available beyond the confines of Ivy League US colleges. It became quickly apparent it was not for me, and so I deleted my account after a relatively short while, only re-establishing a presence in 2013 while trying to make a documentary in Brazil. Local contacts informed me that this was the only platform anyone would ever use to speak to me – and I’ve been more or less trapped there ever since. There are some people in different places around the world who I genuinely care about and am interested in, and while many of them would be surprised to learn they have something in common with South American revolutionary political activists, Facebook is the only place they appear to exist and communicate.

After an initial dalliance with Hipstamatic and a blossoming interest in photography, I signed up to Instagram just slightly too late to secure my preferred ‘dubber’ user name, having to default to my perennially disappointing backup handle with a first initial included.

I don’t particularly enjoy Instagram. You’d think I would. I like taking photos and enjoy other people saying that they like them. I like looking at other people’s photos and seeing the faces of friends. I particularly like seeing people I like having a nice time. I really enjoy seeing cats, dogs and otters being cats, dogs and otters. But the rapid current of that timeline’s stream sweeps them all away before anything resembling actual appreciation can occur. Also, despite my lifelong interest in narrative, I don’t understand ‘Stories’ at all. I’m assured this is an age thing, which seems entirely plausible. But I do feel that Instagram excludes me somehow.

I have absolutely zero idea how long I’ve been on LinkedIn. I have, it seems, successfully blocked out the majority of my experience on that platform, though I suspect my initial registration would probably have coincided with the beginnings of my disillusionment with the world of academia. I’ve never sought alternative employment there, but as corporate and superficial as the site has always seemed to me, there wasn’t really anywhere else that would accommodate that sort of online career daydream.

However, it’s fair to say I don’t like LinkedIn. Nor do I trust how delighted people say they are to announce the things that they announce, nor find credible their purported excitement about what is fundamentally just them doing their job – a job, it should be noted, that they are likely on LinkedIn in the hopes of changing.

I joined The Platform Formerly Known As Twitter not long after it started – 2006, or at the latest, 2007. It has not only been my preferred social media environment ever since, but also my primary means of communication with the majority of the new friends I formed in my thirties and forties – something that moving to the other side of the world inevitably entails.

It’s also been a welcome anchor to home, especially through the no-admittance pandemic years. New Zealand Twitter is often the very best of Twitter. It absolutely ruled through earthquakes, eruptions, lockdown, the most progressive political landscape in living memory and a veritable Aotearoa renaissance in music, art and culture. Throughout, people who were effectively acquaintances when I lived in Auckland became very good friends long after I left.

By dint of my early platform adoption (there weren’t that many people to follow at first) and as a result of having some measure of internet profile acquired by writing about online music at a time when this was an, if not hopeful, then at least not yet entirely demoralising endeavour, I managed to acquire something in the region of 10,000 Twitter followers. This seemed a quantification and reflection of my New Music Strategies readership, but there were other people here too. A lot of them. Not “fame”, by any stretch, but something else. A semblance of significance, perhaps.

As you may have gathered, I was trained (to the extent one was ‘trained’ in the late 1980s) as a radio broadcaster. One of the things they teach you in radio broadcasting is you only ever speak to one person, never to an ‘audience’. I used Twitter a bit like that. So I only ever had one of two main intended recipients in mind: either a) an imagined reader, singular; or b) the actual, real, living human being that I was conversing with.

I spoke to the second of these far more often than I spoke to the first.

Several people I now consider to be among my closest friends are people I got to know on Twitter first, real life ‘meatspace’ later. On several occasions, including one ‘Birmingham Twitter Christmas Gathering’ I organised at my local pub, I actively engineered physical co-presence with people I seemed to like on Twitter. We even swapped gifts. I made mixtapes for attendees. It was quite lovely and everyone who came was someone I could imagine inviting for dinner, if I’d been better at that sort of thing.

While never anywhere close to perfect, for a while Twitter looked like it was managing some of the rose-tinted ambitions of Rheingold and his happy band of cyberhippies. It was a good time with good friends.

My friend Clutch and I hosted live social media whisky tastings (@twhisky, naturally), which, for a while, turned into a bit of a thing that saw us invited to distilleries, having reasonably hair-raising adventures on remote Scottish islands, drinking altogether too much extraordinarily rare and expensive whisky and eventually co-authoring books about the stuff. It also spawned a life motto: Ordeals Beget Treats. More about that… probably elsewhere.