Susan Mary Malone's Blog: Happiness is a Story

February 10, 2020

A NEW NOVEL WITH A TEXAS TWIST

How about a new novel with a Texas Twist? What if you had a fantasy lover and he came to full-blown technicolor life?

Would people think you were a liar? Psychotic? Who would you trust to tell?Shawna counts on only her closest friends but can offer no explanation, even to her therapist—or herself—though her two Labradors know the truth too well.

The timing couldn’t be worse. A hip Jungian analyst with her own radio call-in show, her life starkly in the public eye, a false step or hidden skeleton could ruin everything. Then a tall, dark stranger arrives to take over her town and play dangerous mind games.

When Shawna’s best friend Annabelle has a fling with that stranger, Christian—a man who is also engaged in a perilous sport with Shawna’s producer—things begin to twist out of control. Christian involves himself in another mind game with Annabelle and her psychotic boyfriend, who has drugged and is holding her captive. The world around them spins into a black hole, swirling ever to deeply into a vortex Shawna has run from since childhood.

Inch by inch Shawna descends. Is it madness? In such a mental state, how can she free herself from her own demons long enough to help save her dear friend?

And why with all the various currents pulling them ever over the falls, does Johnny, a character from an old Western television series, decide to defy all the rules of the Universe and arrive squarely and in full human form in her bed? Is he there to help Shawna face the terrifying loss of death that has a vice grip on her remaining sanity? Or is he part of the unfolding suspense of a lover’s triangle gone awry?

So this is the novel I’m working on now, and what fun it is!I’ve studied Jung all my adult life, sometimes getting caught by the foot in a complex of my own making. But then, that’s what Jungian psychology is all about, no? It’s learning the tools to claw your way out of the neuroses that try to trip us all.

And in Jungian terms, all women have a male side (the animus), and men have a female side (the anima). By integrating that “other” side, we become full human beings.

Is Johnny Shawna’s animus? And if so, how did he come to literal life?

A few years ago I talked about a fictional character from my early teens who popped back into my consciousness. Johnny Madrid Lancer stole my heart all those years ago, and, after I wrote this, well, he never really left . . .

And then, the real insanity started. And a book was born.

It all takes place in Ft. Worth, where I grew up and so many of my friends still live. So, it’s quite Ft. Worthian. Lol. But the rest of it dances from my head.

So I’m off to it for a bit, taking a deep dive into revisions, adding texture and nuance to the story. Of course, I’ll keep that luscious cowboy from actually coming to real life.

Or, will I?

A NEW NOVEL WITH A TEXAS TWIST

How about a new novel with a Texas Twist? What if you had a fantasy lover and he came to full-blown technicolor life?

Would people think you were a liar? Psychotic? Who would you trust to tell?

Shawna counts on only her closest friends but can offer no explanation, even to her therapist—or herself—though her two Labradors know the truth too well.

The timing couldn’t be worse. A hip Jungian analyst with her own radio call-in show, her life starkly in the public eye, a false step or hidden skeleton could ruin everything. Then a tall, dark stranger arrives to take over her town and play dangerous mind games.

When Shawna’s best friend Annabelle has a fling with that stranger, Christian—a man who is also engaged in a perilous sport with Shawna’s producer—things begin to twist out of control. Christian involves himself in another mind game with Annabelle and her psychotic boyfriend, who has drugged and is holding her captive. The world around them spins into a black hole, swirling ever to deeply into a vortex Shawna has run from since childhood.

Inch by inch Shawna descends. Is it madness? In such a mental state, how can she free herself from her own demons long enough to help save her dear friend?

And why with all the various currents pulling them ever over the falls, does Johnny, a character from an old Western television series, decide to defy all the rules of the Universe and arrive squarely and in full human form in her bed? Is he there to help Shawna face the terrifying loss of death that has a vice grip on her remaining sanity? Or is he part of the unfolding suspense of a lover’s triangle gone awry?

So this is the novel I’m working on now, and what fun it is!

I’ve studied Jung all my adult life, sometimes getting caught by the foot in a complex of my own making. But then, that’s what Jungian psychology is all about, no? It’s learning the tools to claw your way out of the neuroses that try to trip us all.

And in Jungian terms, all women have a male side (the animus), and men have a female side (the anima). By integrating that “other” side, we become full human beings.

Is Johnny Shawna’s animus? And if so, how did he come to literal life?

A few years ago I talked about a fictional character from my early teens who popped back into my consciousness. Johnny Madrid Lancer stole my heart all those years ago, and, after I wrote this, well, he never really left . . .

And then, the real insanity started. And a book was born.

It all takes place in Ft. Worth, where I grew up and so many of my friends still live. So, it’s quite Ft. Worthian. Lol. But the rest of it dances from my head.

So I’m off to it for a bit, taking a deep dive into revisions, adding texture and nuance to the story. Of course, I’ll keep that luscious cowboy from actually coming to real life.

Or, will I?

October 12, 2019

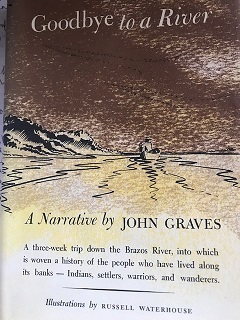

When a Texas Author Produces Pure Gold

Those who read the best books about Texas will know this one inherently, with no need of even a title. It’s where I at least would say modern Texas letters began, with McMurtry soon to follow, and a host of others after him.

But without John Graves’ marvelous voice, the grace of which catches you from word one, without his narrative using journey as story structure, part memoir, part history, the door for the next Texas authors wouldn’t have been opened nearly so wide.

A native Texan who had long since moved around the world, Graves learned in 1957 that the Brazos River would be dammed in several places—a river he had grown up fishing and canoeing and hunting on. So on assignment for Sports Illustrated, he took a 3-week trip down the part of it that had been “his,” from below Possum Kingdom Lake to around Glen Rose, to reclaim what would purportedly be forever changed.

Sports Illustrated rejected the article (man, would I love to see that rejection letter!). Holiday Magazine eventually published it. But of course, the river itself, like all of Texas, and his ode to the beauty of it, as well as the harshness of the land and the violence that took place around its shores, couldn’t be contained in only such a short piece.

So in 1960, Goodbye to a River was published by Knopf. Huge critical acclaim followed, and still today writers and readers speak of it with no small measure of reverence. Including me.The late historian A.C. Green, in a review for the Dallas Times Herald, said it was “as fine a book as has ever been written about Texas.”

And John Graves became known as the Dean of Texas Letters.

As he’s paddling down the Brazos (named by the Spanish, meaning “Arms of God”), showing us places where a bald eagle could still come “flapping easily down the wind,” he relays stories of the clashes as settlers began homesteading the area. Most of that brutal history spans about a twenty-year stretch from the late 1850s to the ‘70s, with some beyond.

Because this was as bloody a piece of Texas history as it gets.We didn’t just have regular Indians. Texas, during that time, was part of the Comancheria, which stretched from the vast lands of West Texas to New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Kansas. For 2 centuries the Comanche had ruled this area, going from pretty much the dregs of Indian society to the fiercest, meanest of the mean, once they figured out the proper use of the horse wasn’t for barbeques.

When they did, though, becoming master horsemen and fierce fighters, nobody could best them.

So, thinking the land was theirs (as it had been for centuries), they played blood sport with the incoming early settlers, most of whom were Southern, fleeing the War to come and the one they lost if they stayed. They were, as Graves said, “sharp around the edges, not tender . . .” And once the War Between the States ended, here came the cavalry and the Texas Rangers too.

A bloody time indeed.

Graves relates stories of Charles Goodnight and Cynthia Ann Parker and her half-white son Quanah, and of famous massacres of settlers by Comanche warriors.But he also tells the ones about the not-so-famous, like Jesse Veale, the last man killed in the county by the Comanche in 1873, at Ioni Creek. He and his friend had stolen some Indian ponies, and the warriors came at them. When Joe yelled, “What the hell we gonna do?” he thought Jesse yelled, “Run it out!” Joe did. But when he looked back, Jesse was on the ground shooting and trying to club the warriors with his pistol. To no avail, of course. And for probably a thousand times throughout his life, Joe must have wondered what if he had said, “Fight it out.”

The book is peppered with these vignettes, at the spots where they happened. As Graves said, “No end. No end to the stories . . .”

And funny thing, Texans being Texans, once the Comanche were finally contained, including Quanah Parker, who became not only a great chief but traded quite prosperously with the white man. Well, the new settlers turned a bit on each other. Sometimes they even dressed up as Indians to go attack one another.

Of the mostly Southern folks who settled here, Graves said, “They were cattle kings and horse thieves and half-breeds and whole sons of bitches and preachers in droves and sinners in swarms.”

No wonder with that mix peace didn’t come quickly!

As Graves said, “Law and order . . . were fairly faint ideals.”

But this is also in its essence, an ode to the love one man has for “his” part of the river, and for being upon it, with it, letting the stories and remembrances slowly rise to the surface.“The river’s aloneness was on me and I liked it and was going to hold onto it while it lasted.”

The depths of meaning bubble up slowly through the long well-constructed passages, so that many quotations don’t capture the essence, sort of like how one piece of the river doesn’t express the whole thing.

In today’s world of rushing books, where plot turners are king, what a beautiful breath of fresh air it was reading this again. I first read it at 17, and have reread it countless times since. The voice. That’s what modern books have lost, with some exceptions of course, but to read prose from a writer with such mastery, ahhhh. Heaven. And of course, as many folks know, I’m just a fool for such a voice.

Full disclosure: I knew Mr. Graves. He ultimately settled with his wife and children near Glen Rose. There he wrote Hard Scrabble and From a Limestone Ledge about the land. We have a farm in Bosque County, not far from there, and for 7 glorious years I lived and tended cattle there, mended fence, cut and baled hay. The usual farm stuff. The best living and the best place to write.

We’d run into one another now and then, and at literary events. He was a quiet, thoughtful man, with a playful sense of humor. And so gallant. He never missed asking how my writing was going.

The heart of this wonderful book is knowing who you are, the part of the place from which you come, how important that is to the person you became.“If a man couldn’t escape what he came from, we would most of us still be peasants in Old World hovels. But if, having escaped or not, he wants in some way to know himself, define himself, and tries to do it without taking into account the thing he came from, he is writing without any ink in his pen.”

We’ll go from here to more “modern” books about Texas, but to understand Texas Letters, and the best books about Texas, The Wind from our last discussion, and Goodbye to a River from this one, provide the foundation upon which those letters stand.

Ah, the richness of them. And it always makes me think, as Graves said about the river:

“The point was to be there.”

When a Texas Author Produces Pure Gold

.single .thumbnail img {

width: 400px;

}

Those who read the best books about Texas will know this one inherently, with no need of even a title. It’s where I at least would say modern Texas letters began, with McMurtry soon to follow, and a host of others after him.

But without John Graves’ marvelous voice, the grace of which catches you from word one, without his narrative using journey as story structure, part memoir, part history, the door for the next Texas authors wouldn’t have been opened nearly so wide.

A native Texan who had long since moved around the world, Graves learned in 1957 that the Brazos River would be dammed in several places—a river he had grown up fishing and canoeing and hunting on. So on assignment for Sports Illustrated, he took a 3-week trip down the part of it that had been “his,” from below Possum Kingdom Lake to around Glen Rose, to reclaim what would purportedly be forever changed.

Sports Illustrated rejected the article (man, would I love to see that rejection letter!). Holiday Magazine eventually published it. But of course, the river itself, like all of Texas, and his ode to the beauty of it, as well as the harshness of the land and the violence that took place around its shores, couldn’t be contained in only such a short piece.

So in 1960, Goodbye to a River was published by Knopf. Huge critical acclaim followed, and still today writers and readers speak of it with no small measure of reverence. Including me.

The late historian A.C. Green, in a review for the Dallas Times Herald, said it was “as fine a book as has ever been written about Texas.”

And John Graves became known as the Dean of Texas Letters.

As he’s paddling down the Brazos (named by the Spanish, meaning “Arms of God”), showing us places where a bald eagle could still come “flapping easily down the wind,” he relays stories of the clashes as settlers began homesteading the area. Most of that brutal history spans about a twenty-year stretch from the late 1850s to the ‘70s, with some beyond.

Because this was as bloody a piece of Texas history as it gets.

We didn’t just have regular Indians. Texas, during that time, was part of the Comancheria, which stretched from the vast lands of West Texas to New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Kansas. For 2 centuries the Comanche had ruled this area, going from pretty much the dregs of Indian society to the fiercest, meanest of the mean, once they figured out the proper use of the horse wasn’t for barbeques.

When they did, though, becoming master horsemen and fierce fighters, nobody could best them.

So, thinking the land was theirs (as it had been for centuries), they played blood sport with the incoming early settlers, most of whom were Southern, fleeing the War to come and the one they lost if they stayed. They were, as Graves said, “sharp around the edges, not tender . . .” And once the War Between the States ended, here came the cavalry and the Texas Rangers too.

A bloody time indeed.

Graves relates stories of Charles Goodnight and Cynthia Ann Parker and her half-white son Quanah, and of famous massacres of settlers by Comanche warriors.

But he also tells the ones about the not-so-famous, like Jesse Veale, the last man killed in the county by the Comanche in 1873, at Ioni Creek. He and his friend had stolen some Indian ponies, and the warriors came at them. When Joe yelled, “What the hell we gonna do?” he thought Jesse yelled, “Run it out!” Joe did. But when he looked back, Jesse was on the ground shooting and trying to club the warriors with his pistol. To no avail, of course. And for probably a thousand times throughout his life, Joe must have wondered what if he had said, “Fight it out.”

The book is peppered with these vignettes, at the spots where they happened. As Graves said, “No end. No end to the stories . . .”

And funny thing, Texans being Texans, once the Comanche were finally contained, including Quanah Parker, who became not only a great chief but traded quite prosperously with the white man. Well, the new settlers turned a bit on each other. Sometimes they even dressed up as Indians to go attack one another.

Of the mostly Southern folks who settled here, Graves said, “They were cattle kings and horse thieves and half-breeds and whole sons of bitches and preachers in droves and sinners in swarms.”

No wonder with that mix peace didn’t come quickly!

As Graves said, “Law and order . . . were fairly faint ideals.”

But this is also in its essence, an ode to the love one man has for “his” part of the river, and for being upon it, with it, letting the stories and remembrances slowly rise to the surface.

“The river’s aloneness was on me and I liked it and was going to hold onto it while it lasted.”

The depths of meaning bubble up slowly through the long well-constructed passages, so that many quotations don’t capture the essence, sort of like how one piece of the river doesn’t express the whole thing.

In today’s world of rushing books, where plot turners are king, what a beautiful breath of fresh air it was reading this again. I first read it at 17, and have reread it countless times since. The voice. That’s what modern books have lost, with some exceptions of course, but to read prose from a writer with such mastery, ahhhh. Heaven. And of course, as many folks know, I’m just a fool for such a voice.

Full disclosure: I knew Mr. Graves. He ultimately settled with his wife and children near Glen Rose. There he wrote Hard Scrabble and From a Limestone Ledge about the land. We have a farm in Bosque County, not far from there, and for 7 glorious years I lived and tended cattle there, mended fence, cut and baled hay. The usual farm stuff. The best living and the best place to write.

We’d run into one another now and then, and at literary events. He was a quiet, thoughtful man, with a playful sense of humor. And so gallant. He never missed asking how my writing was going.

The heart of this wonderful book is knowing who you are, the part of the place from which you come, how important that is to the person you became.

“If a man couldn’t escape what he came from, we would most of us still be peasants in Old World hovels. But if, having escaped or not, he wants in some way to know himself, define himself, and tries to do it without taking into account the thing he came from, he is writing without any ink in his pen.”

We’ll go from here to more “modern” books about Texas, but to understand Texas Letters, and the best books about Texas, The Wind from our last discussion, and Goodbye to a River from this one, provide the foundation upon which those letters stand.

Ah, the richness of them. And it always makes me think, as Graves said about the river:

“The point was to be there.”

October 10, 2019

When a Texas Author Produces Pure Gold

width: 400px;

}

Those who read the best books about Texas will know this one inherently, with no need of even a title. It’s where I at least would say modern Texas letters began, with McMurtry soon to follow, and a host of others after him.

But without John Graves’ marvelous voice, the grace of which catches you from word one, without his narrative using journey as story structure, part memoir, part history, the door for the next Texas authors wouldn’t have been opened nearly so wide.

A native Texan who had long since moved around the world, Graves learned in 1957 that the Brazos River would be dammed in several places—a river he had grown up fishing and canoeing and hunting on. So on assignment for Sports Illustrated, he took a 3-week trip down the part of it that had been “his,” from below Possum Kingdom Lake to around Glen Rose, to reclaim what would purportedly be forever changed.

Sports Illustrated rejected the article (man, would I love to see that rejection letter!). Holiday Magazine eventually published it. But of course, the river itself, like all of Texas, and his ode to the beauty of it, as well as the harshness of the land and the violence that took place around its shores, couldn’t be contained in only such a short piece.

So in 1960, Goodbye to a River was published by Knopf. Huge critical acclaim followed, and still today writers and readers speak of it with no small measure of reverence. Including me.

The late historian A.C. Green, in a review for the Dallas Times Herald, said it was “as fine a book as has ever been written about Texas.”

And John Graves became known as the Dean of Texas Letters.

As he’s paddling down the Brazos (named by the Spanish, meaning “Arms of God”), showing us places where a bald eagle could still come “flapping easily down the wind,” he relays stories of the clashes as settlers began homesteading the area. Most of that brutal history spans about a twenty-year stretch from the late 1850s to the ‘70s, with some beyond.

Because this was as bloody a piece of Texas history as it gets.

We didn’t just have regular Indians. Texas, during that time, was part of the Comancheria, which stretched from the vast lands of West Texas to New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Kansas. For 2 centuries the Comanche had ruled this area, going from pretty much the dregs of Indian society to the fiercest, meanest of the mean, once they figured out the proper use of the horse wasn’t for barbeques.

When they did, though, becoming master horsemen and fierce fighters, nobody could best them.

So, thinking the land was theirs (as it had been for centuries), they played blood sport with the incoming early settlers, most of whom were Southern, fleeing the War to come and the one they lost if they stayed. They were, as Graves said, “sharp around the edges, not tender . . .” And once the War Between the States ended, here came the cavalry and the Texas Rangers too.

A bloody time indeed.

Graves relates stories of Charles Goodnight and Cynthia Ann Parker and her half-white son Quanah, and of famous massacres of settlers by Comanche warriors.

But he also tells the ones about the not-so-famous, like Jesse Veale, the last man killed in the county by the Comanche in 1873, at Ioni Creek. He and his friend had stolen some Indian ponies, and the warriors came at them. When Joe yelled, “What the hell we gonna do?” he thought Jesse yelled, “Run it out!” Joe did. But when he looked back, Jesse was on the ground shooting and trying to club the warriors with his pistol. To no avail, of course. And for probably a thousand times throughout his life, Joe must have wondered what if he had said, “Fight it out.”

The book is peppered with these vignettes, at the spots where they happened. As Graves said, “No end. No end to the stories . . .”

And funny thing, Texans being Texans, once the Comanche were finally contained, including Quanah Parker, who became not only a great chief but traded quite prosperously with the white man. Well, the new settlers turned a bit on each other. Sometimes they even dressed up as Indians to go attack one another.

Of the mostly Southern folks who settled here, Graves said, “They were cattle kings and horse thieves and half-breeds and whole sons of bitches and preachers in droves and sinners in swarms.”

No wonder with that mix peace didn’t come quickly!

As Graves said, “Law and order . . . were fairly faint ideals.”

But this is also in its essence, an ode to the love one man has for “his” part of the river, and for being upon it, with it, letting the stories and remembrances slowly rise to the surface.

“The river’s aloneness was on me and I liked it and was going to hold onto it while it lasted.”

The depths of meaning bubble up slowly through the long well-constructed passages, so that many quotations don’t capture the essence, sort of like how one piece of the river doesn’t express the whole thing.

In today’s world of rushing books, where plot turners are king, what a beautiful breath of fresh air it was reading this again. I first read it at 17, and have reread it countless times since. The voice. That’s what modern books have lost, with some exceptions of course, but to read prose from a writer with such mastery, ahhhh. Heaven. And of course, as many folks know, I’m just a fool for such a voice.

Full disclosure: I knew Mr. Graves. He ultimately settled with his wife and children near Glen Rose. There he wrote Hard Scrabble and From a Limestone Ledge about the land. We have a farm in Bosque County, not far from there, and for 7 glorious years I lived and tended cattle there, mended fence, cut and baled hay. The usual farm stuff. The best living and the best place to write.

We’d run into one another now and then, and at literary events. He was a quiet, thoughtful man, with a playful sense of humor. And so gallant. He never missed asking how my writing was going.

The heart of this wonderful book is knowing who you are, the part of the place from which you come, how important that is to the person you became.

“If a man couldn’t escape what he came from, we would most of us still be peasants in Old World hovels. But if, having escaped or not, he wants in some way to know himself, define himself, and tries to do it without taking into account the thing he came from, he is writing without any ink in his pen.”

We’ll go from here to more “modern” books about Texas, but to understand Texas Letters, and the best books about Texas, The Wind from our last discussion, and Goodbye to a River from this one, provide the foundation upon which those letters stand.

Ah, the richness of them. And it always makes me think, as Graves said about the river:

“The point was to be there.”

August 30, 2019

When Texas Female Authors Go Awry

Texans love their state, that’s for sure. This is a proud place, by its heritage, its culture, and the people’s love of the land. Especially in the vast expanses of West Texas, the folks who settled it were a gritty bunch, and still are today. So what happens with a Texas female author disparages an entire area?

It doesn’t go well. Which is a bit of an understatement!In 1925, Harper and Brothers published a novel called The Wind, set outside of Sweetwater, Texas. And, they published it anonymously, as a marketing ploy. But although reviews in newspapers outside the South were favorable (one likening it to the sweeping tragedy of Russian novels), those from Texas flew into a rage.

R. C. Crane, a Sweetwater lawyer and president of the West Texas Historical Society called it “a deliberate effort, by disregard and exaggeration and distortion of facts, to deliver a slam on West Texas in the making.”

Some thought it was written by, horrors!, a Yankee, in order to perpetrate anti-Texas propaganda. There were even unconfirmed stories of public book burnings. As Texas Monthly said at the time, “It was . . . roundly ‘cussed’ by West Texans . . .”

In short, the state’s people were pissed.

In 1926, the author’s name was revealed as novelist, scholar, and folklorist Dorothy Scarborough. A Native Texan who spent years of her childhood living in Sweetwater. She was held in high esteem. So the criticism did die down. Some.

I first heard of this book decades ago while taking a class in Folklore at Texas A&M, under Dr. Sylvia Ann Grider, who wrote the foreword to this edition. I thought I knew something about Texas Letters back then, and was somewhat shocked to learn of this book.

And of course my question was, what caused all the uproar?Plenty, I’ll tell you!

Set in the devastating drought the area faced in 1886-87, which wiped out the burgeoning cattle boom. The book helped to if not destroy, to at least put a chink in the whole myth of Texas and the romance of the cowboy.

It was not a pretty time.

Enter into this vast land of sand storms and drought and unrelenting wind. A young woman from Virginia, left destitute and sent to her only living relative—a cousin and hard-scrabble cattle rancher—for shelter.

This is no Edna Ferber’s Giant, where a similar young Eastern girl moves to the West Texas plains. In that book, from a well-to-do family, Leslie marries the larger-than-life Bick Benedict, and moves into the big house, on sections upon sections of land. But she always had a place to go back to.

Funny thing though—the press didn’t treat Ferber’s book much better. The Houston Press suggested she should be lynched!

The two well-known and thought-of Texas female authors were acquaintances, although the two books were published twenty years apart.

But on the opposite end of the spectrum, Letty, our poor, frail, nervous waif sent from the fertile hills and valleys of Virginia, is deposited into a shack, where the wind and the sand rage through the cracks in the walls, coating everything—always—with dust. And she has no home to go back to.

It wasn’t, however, the sand or the bleak barren landscape, or the lack of people to visit (mirroring the lack of food and water), which did Letty in.

But rather, as the book begins, “The wind was the cause of it all.”Especially when the demon norther rides in.

As the book proclaims, “So the norther was a wild stallion that raced over the plains, mighty in power, cruel in spirit, more to be feared than man. One could hear his terrible neighings in the night, and fancy one saw him sweeping over the plains with his imperious mane flying backward and his fiery hoofs ready to trample one down.”

And this from page 2-3!

So we know from the get-go things do not bode well for sensitive Letty. Just as we know from the first moments on the train, chugging her every so inexorably toward her destination as massive water flowing irrevocably to Niagara Falls, that we’re headed toward a beastly descent.

And, we also know she’s not the most stable of sorts to begin.

What could possibly go wrong?

We have a front-row seat as Letty slowly goes mad. Indeed, the descent is so meticulously done, it starts in the beginning and almost every line thereafter continues the drip, drip of her sanity being siphoned away.

“The wind was angry that she had read its thoughts so clearly, for it had risen to a gale now, and shouted round the house. It called to her to come out if she dared. It defied her, challenged her, mocked her.”

The story draws to a conclusion that is at once as horrifying as it is perfect for the character. Though you didn’t see it coming, it all just fits.

Unless you’ve experienced this wind, you can’t imagine the sweep of it, relentless across unending treeless prairies as it whips the sand into icicles that cut through your skin like searing sandpaper. In certain seasons, it blows without ceasing.

But it’s the loneliness that underlies it that is the true demon in the wind.I’ve spent some time in West Texas, my mom growing up on a farm there outside of Ballinger. So we went to visit relatives a lot. My grandparents farmed vast acres (at least to me!) of cotton, the fields stretching out forever and a day.

And when the wind blew, as it often did, ripping the orange clay from the ground and flinging it headlong through the air, that cruel spirit that robbed women of their pretty skin and bright eyes, it being far harder on them than on men, made one shiver at its fury.

What I remember most though was the haunting loneliness between the roar of the gales.

My mom didn’t see it that way. Lol. She was from hardy stock, raised on the West Texas land. She did tell me stories of the great Dust Bowl, of Mamaw sweeping heaps of sand out of the house every morning, which came through every available crack (and in my young mind, probably made more cracks on its own). And of Mamaw putting wet rags over the children’s faces at night to keep the sand from their lungs, and hopefully stave off the dust pneumonia (which took many a child during that time).

But she also told of how they thought they were rich during the Depression, because they grew their own food. There are benefits to being raised on a farm.

And being of such sturdy stock helped propel her to college, and then to nursing school. Back in a time when most women had no career, she became head charge nurse on the pediatric unit at John Sealy Hospital in Galveston.

I believe a land makes its people. And, that folks are different from diverse areas. West Texas folks are tough as nails, generous to a fault, sturdy as hell, and somewhat unforgiving of weakness (as is Cora, Letty’s cousin’s wife, in the book).

The land makes them so. My mother was the strongest person I’ve ever met. She bore the deepest of human sorrows. Brought her to her knees, but she stood again. And faced life as it came.

Sensitive, frail, Easterner Letty wasn’t made of such robust stock, and had little to draw from in order to face that demon wind.

But ahh, what an amazing piece of literature as she gets swallowed whole by her madness.This is a wonderful book, written by a Texas female author at the top of her game, and despite (or perhaps in addition to) all the hoopla, it deserves its place in the cannon of Texas Letters.

If you want to know what it was really like in the late 1800s in West Texas, past the romance and myth, beneath the hopes and dreams that drove people westward, The Wind will carry you through. Ride along as:

“Again the curtains of sand were rolled up from the plains to the sky, wavering, shifting, their gigantic folds writhing with hideous suggestion.

“What horrors did those curtains hide?”

And since it’s been the Dog Days here in Texas, our August giveaway includes lots of dog stuff to help beat the heat! That and wine glasses and wine t-shirt, signed books and bluebonnet soap. Come join us!

When Texas Female Authors Go Awry

width: 400px;

}

Texans love their state, that’s for sure. This is a proud place, by its heritage, its culture, and the people’s love of the land. Especially in the vast expanses of West Texas, the folks who settled it were a gritty bunch, and still are today. So what happens with a Texas female author disparages an entire area?

It doesn’t go well. Which is a bit of an understatement!

In 1925, Harper and Brothers published a novel called The Wind, set outside of Sweetwater, Texas. And, they published it anonymously, as a marketing ploy. But although reviews in newspapers outside the South were favorable (one likening it to the sweeping tragedy of Russian novels), those from Texas flew into a rage.

R. C. Crane, a Sweetwater lawyer and president of the West Texas Historical Society called it “a deliberate effort, by disregard and exaggeration and distortion of facts, to deliver a slam on West Texas in the making.”

Some thought it was written by, horrors!, a Yankee, in order to perpetrate anti-Texas propaganda. There were even unconfirmed stories of public book burnings. As Texas Monthly said at the time, “It was . . . roundly ‘cussed’ by West Texans . . .”

In short, the state’s people were pissed.

In 1926, the author’s name was revealed as novelist, scholar, and folklorist Dorothy Scarborough. A Native Texan who spent years of her childhood living in Sweetwater. She was held in high esteem. So the criticism did die down. Some.

I first heard of this book decades ago while taking a class in Folklore at Texas A&M, under Dr. Sylvia Ann Grider, who wrote the foreword to this edition. I thought I knew something about Texas Letters back then, and was somewhat shocked to learn of this book.

And of course my question was, what caused all the uproar?

Plenty, I’ll tell you!

Set in the devastating drought the area faced in 1886-87, which wiped out the burgeoning cattle boom. The book helped to if not destroy, to at least put a chink in the whole myth of Texas and the romance of the cowboy.

It was not a pretty time.

Enter into this vast land of sand storms and drought and unrelenting wind. A young woman from Virginia, left destitute and sent to her only living relative—a cousin and hard-scrabble cattle rancher—for shelter.

This is no Edna Ferber’s Giant, where a similar young Eastern girl moves to the West Texas plains. In that book, from a well-to-do family, Leslie marries the larger-than-life Bick Benedict, and moves into the big house, on sections upon sections of land. But she always had a place to go back to.

Funny thing though—the press didn’t treat Ferber’s book much better. The Houston Press suggested she should be lynched!

The two well-known and thought-of Texas female authors were acquaintances, although the two books were published twenty years apart.

But on the opposite end of the spectrum, Letty, our poor, frail, nervous waif sent from the fertile hills and valleys of Virginia, is deposited into a shack, where the wind and the sand rage through the cracks in the walls, coating everything—always—with dust. And she has no home to go back to.

It wasn’t, however, the sand or the bleak barren landscape, or the lack of people to visit (mirroring the lack of food and water), which did Letty in.

But rather, as the book begins, “The wind was the cause of it all.”

Especially when the demon norther rides in.

As the book proclaims, “So the norther was a wild stallion that raced over the plains, mighty in power, cruel in spirit, more to be feared than man. One could hear his terrible neighings in the night, and fancy one saw him sweeping over the plains with his imperious mane flying backward and his fiery hoofs ready to trample one down.”

And this from page 2-3!

So we know from the get-go things do not bode well for sensitive Letty. Just as we know from the first moments on the train, chugging her every so inexorably toward her destination as massive water flowing irrevocably to Niagara Falls, that we’re headed toward a beastly descent.

And, we also know she’s not the most stable of sorts to begin.

What could possibly go wrong?

We have a front-row seat as Letty slowly goes mad. Indeed, the descent is so meticulously done, it starts in the beginning and almost every line thereafter continues the drip, drip of her sanity being siphoned away.

“The wind was angry that she had read its thoughts so clearly, for it had risen to a gale now, and shouted round the house. It called to her to come out if she dared. It defied her, challenged her, mocked her.”

The story draws to a conclusion that is at once as horrifying as it is perfect for the character. Though you didn’t see it coming, it all just fits.

Unless you’ve experienced this wind, you can’t imagine the sweep of it, relentless across unending treeless prairies as it whips the sand into icicles that cut through your skin like searing sandpaper. In certain seasons, it blows without ceasing.

But it’s the loneliness that underlies it that is the true demon in the wind.

I’ve spent some time in West Texas, my mom growing up on a farm there outside of Ballinger. So we went to visit relatives a lot. My grandparents farmed vast acres (at least to me!) of cotton, the fields stretching out forever and a day.

And when the wind blew, as it often did, ripping the orange clay from the ground and flinging it headlong through the air, that cruel spirit that robbed women of their pretty skin and bright eyes, it being far harder on them than on men, made one shiver at its fury.

What I remember most though was the haunting loneliness between the roar of the gales.

My mom didn’t see it that way. Lol. She was from hardy stock, raised on the West Texas land. She did tell me stories of the great Dust Bowl, of Mamaw sweeping heaps of sand out of the house every morning, which came through every available crack (and in my young mind, probably made more cracks on its own). And of Mamaw putting wet rags over the children’s faces at night to keep the sand from their lungs, and hopefully stave off the dust pneumonia (which took many a child during that time).

But she also told of how they thought they were rich during the Depression, because they grew their own food. There are benefits to being raised on a farm.

And being of such sturdy stock helped propel her to college, and then to nursing school. Back in a time when most women had no career, she became head charge nurse on the pediatric unit at John Sealy Hospital in Galveston.

I believe a land makes its people. And, that folks are different from diverse areas. West Texas folks are tough as nails, generous to a fault, sturdy as hell, and somewhat unforgiving of weakness (as is Cora, Letty’s cousin’s wife, in the book).

The land makes them so. My mother was the strongest person I’ve ever met. She bore the deepest of human sorrows. Brought her to her knees, but she stood again. And faced life as it came.

Sensitive, frail, Easterner Letty wasn’t made of such robust stock, and had little to draw from in order to face that demon wind.

But ahh, what an amazing piece of literature as she gets swallowed whole by her madness.

This is a wonderful book, written by a Texas female author at the top of her game, and despite (or perhaps in addition to) all the hoopla, it deserves its place in the cannon of Texas Letters.

If you want to know what it was really like in the late 1800s in West Texas, past the romance and myth, beneath the hopes and dreams that drove people westward, The Wind will carry you through. Ride along as:

“Again the curtains of sand were rolled up from the plains to the sky, wavering, shifting, their gigantic folds writhing with hideous suggestion.

“What horrors did those curtains hide?”

And since it’s been the Dog Days here in Texas, our August giveaway includes lots of dog stuff to help beat the heat! That and wine glasses and wine t-shirt, signed books and bluebonnet soap. Come join us!

August 2, 2019

Why Writers Write

Oh, for about a gazillion reasons! Some serious, lots of goofy ones too. And we really all may be crazy to boot :). But whether a famous Texas author or a not-so-famous one from Brazil, the reasons writers write are as unique and personal as each one penning something on the page.

[image error]

Here’s a short list: They have something to sayWe all do, no? Writers just actually put it on paper.

They love books and wordsOh, God, I hope we all do!

To help them make sense of some event in their livesEven Hemingway said he got over a lot of things by writing them out.

To change the world (yep, insane as that might sound!)You have to be somewhat starry eyed to do this!

It’s such a glamorous lifeLOL!

To see their names in printSome arrogance actually helps you stay in this crazy game.

To become richDouble LOL!

To be readAhhh, how writers love when people read their books!

Even more when they review! We can live off of a good review for a long time.

To leave something tangible at the end of this lifeWe all want that, no? Some marker that says, “I was here.”

Because they mustAnd of course, an entire litany of reasons exist.

Funny thing, this writing life. You actually spend the vast majority of it (99.9{6464318088dfd005ab448827a59cc6b2cc907b812a28fd79b32dfd5dcd883448}) in your quiet, hopefully well-lighted room, as Hemingway called it. Alone. In solitary confinement.

The writing itself just has to be done in silence.

But also funny enough, it’s that other .1{6464318088dfd005ab448827a59cc6b2cc907b812a28fd79b32dfd5dcd883448} that takes out most writers. The querying of agents. If you do sign with one (the vast majority of writers never do), then the agent querying publishers. All the rejections that come with this. Then, after publication, the criticism in negative reviews.

And that doesn’t even mention all the promotion, which is an entire job in itself.

Putting your baby out into the world is always a humbling experience. Even for the most famous Texas authors, and those from around the world, working today.

Because no writer is every reader’s cup of tea.

Often, it’s awkward for friends and/or family to read an author’s book. They hesitate, because, well, they just didn’t like it. And this most often comes back to they prefer other genres. Which is perfectly fine. If you love Chinese food and hate Mexican and I take you to Joe T. Garcia’s, I won’t be surprised when you complain J

Likewise, if you normally read Category Romance, or Spy Thrillers, or Sci/Fi, or Cozy Mysteries, you’re not gonna like my books very much. It’s okay! I already know that.

Rejection is a given in this business. Writers write despite it.

What authors strive for is to find their audience. To reach those who do read in their genre. All we ask for is that those folks find us, and give us a read. Wherever those chips fall, well, is where they fall.

We’ll beg for your review anyway 🙂

You can’t imagine the number of writers I’ve seen come and go. Stars in their eyes; the dream of fame and fortune on their horizon. For every writer I know who has stuck with it, 200 more have fallen away. I work with so many authors as well, and see this every day.

Because if you write for any or all of the first 9 reasons, and not the 10th, the fortitude to stick with it proves elusive.

Ten years ago, I allowed this business to break my heart. My literary agent could not get my new novel sold. We received the most beautiful rejections from major publishers you can imagine. They loved it—loved the characters, the story, the writing. But the business was changing, and what NY publishers wanted were huge, break-out books (they still do). The midlist author died.

And yep, my heart got broken and for a while, I couldn’t write. My courage took a hike and horror of horrors, I just quit for a bit.

I went insane though.

Because even if I didn’t write them out, characters were still enacting stories in my head. Playing their parts, even if I refused to play mine.

Nobody ever said writers were the most stable of folks!

But I realized then, I couldn’t not write. It is my world. My true love. As my pastor-friend said (and still does), “It’s your form of prayer.”

And now my agent is shopping to publishers my new novel J

Yep. I never feel closer to the divine than when I’m writing.

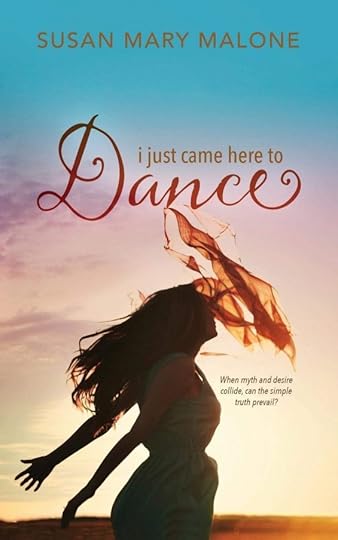

Oh, and that book we couldn’t sell? It was picked up by a small publisher, and had a great run. I own the rights back now, and it’s soon to be published as an author’s edition. I Just Came here to Dance will be out again soon!

The fabulous Texas author Chris Manno talks some about this in our recent newsletter as well. If you haven’t read Chris, you’re missing a real treat!

So why do writers write? For a lot of reasons. But the ones who stick it out, write because they must J

As the poet Rainer Marie Rilke said, in Letters to a Young Poet:

“This most of all: ask yourself in the most silent hour of your night: must I write? Dig into yourself for a deep answer. And if this answer rings out in assent, if you meet this solemn question with a strong, simple “I must,” then build your life in accordance with this necessity . . .”

And our July giveaway of cool Texas and wine stuff drew lots of entries! Mr Green drew the winner from a hat

[image error]

Kristine Hall, of Lone Star Literary Life. How fitting! Don’t forget to come join in the fun for August!

.single .thumbnail img{width: 400px;}Why Writers Write

Oh, for about a gazillion reasons! Some serious, lots of goofy ones too. And we really all may be crazy to boot :). But whether a famous Texas author or a not-so-famous one from Brazil, the reasons writers write are as unique and personal as each one penning something on the page.

Here’s a short list:

They have something to say

We all do, no? Writers just actually put it on paper.

They love books and words

Oh, God, I hope we all do!

To help them make sense of some event in their lives

Even Hemingway said he got over a lot of things by writing them out.

To change the world (yep, insane as that might sound!)

You have to be somewhat starry eyed to do this!

It’s such a glamorous life

LOL!

To see their names in print

Some arrogance actually helps you stay in this crazy game.

To become rich

Double LOL!

To be read

Ahhh, how writers love when people read their books!

Even more when they review! We can live off of a good review for a long time.

To leave something tangible at the end of this life

We all want that, no? Some marker that says, “I was here.”

Because they must

And of course, an entire litany of reasons exist.

Funny thing, this writing life. You actually spend the vast majority of it (99.9%) in your quiet, hopefully well-lighted room, as Hemingway called it. Alone. In solitary confinement.

The writing itself just has to be done in silence.

But also funny enough, it’s that other .1% that takes out most writers. The querying of agents. If you do sign with one (the vast majority of writers never do), then the agent querying publishers. All the rejections that come with this. Then, after publication, the criticism in negative reviews.

And that doesn’t even mention all the promotion, which is an entire job in itself.

Putting your baby out into the world is always a humbling experience. Even for the most famous Texas authors, and those from around the world, working today.

Because no writer is every reader’s cup of tea.

Often, it’s awkward for friends and/or family to read an author’s book. They hesitate, because, well, they just didn’t like it. And this most often comes back to they prefer other genres. Which is perfectly fine. If you love Chinese food and hate Mexican and I take you to Joe T. Garcia’s, I won’t be surprised when you complain J

Likewise, if you normally read Category Romance, or Spy Thrillers, or Sci/Fi, or Cozy Mysteries, you’re not gonna like my books very much. It’s okay! I already know that.

Rejection is a given in this business. Writers write despite it.

What authors strive for is to find their audience. To reach those who do read in their genre. All we ask for is that those folks find us, and give us a read. Wherever those chips fall, well, is where they fall.

We’ll beg for your review anyway

July 31, 2019

Why Writers Write

Oh, for about a gazillion reasons! Some serious, lots of goofy ones too. And we really all may be crazy to boot :). But whether a famous Texas author or a not-so-famous one from Brazil, the reasons writers write are as unique and personal as each one penning something on the page.

Here’s a short list:

They have something to say

We all do, no? Writers just actually put it on paper.

They love books and words

Oh, God, I hope we all do!

To help them make sense of some event in their lives

Even Hemingway said he got over a lot of things by writing them out.

To change the world (yep, insane as that might sound!)

You have to be somewhat starry eyed to do this!

It’s such a glamorous life

LOL!

To see their names in print

Some arrogance actually helps you stay in this crazy game.

To become rich

Double LOL!

To be read

Ahhh, how writers love when people read their books!

Even more when they review! We can live off of a good review for a long time.

To leave something tangible at the end of this life

We all want that, no? Some marker that says, “I was here.”

Because they must

And of course, an entire litany of reasons exist.

Funny thing, this writing life. You actually spend the vast majority of it (99.9%) in your quiet, hopefully well-lighted room, as Hemingway called it. Alone. In solitary confinement.

The writing itself just has to be done in silence.

But also funny enough, it’s that other .1% that takes out most writers. The querying of agents. If you do sign with one (the vast majority of writers never do), then the agent querying publishers. All the rejections that come with this. Then, after publication, the criticism in negative reviews.

And that doesn’t even mention all the promotion, which is an entire job in itself.

Putting your baby out into the world is always a humbling experience. Even for the most famous Texas authors, and those from around the world, working today.

Because no writer is every reader’s cup of tea.

Often, it’s awkward for friends and/or family to read an author’s book. They hesitate, because, well, they just didn’t like it. And this most often comes back to they prefer other genres. Which is perfectly fine. If you love Chinese food and hate Mexican and I take you to Joe T. Garcia’s, I won’t be surprised when you complain J

Likewise, if you normally read Category Romance, or Spy Thrillers, or Sci/Fi, or Cozy Mysteries, you’re not gonna like my books very much. It’s okay! I already know that.

Rejection is a given in this business. Writers write despite it.

What authors strive for is to find their audience. To reach those who do read in their genre. All we ask for is that those folks find us, and give us a read. Wherever those chips fall, well, is where they fall.

We’ll beg for your review anyway

Happiness is a Story

- Susan Mary Malone's profile

- 85 followers