Jake Berman's Blog

October 5, 2025

Jake's Endorsements, November 2025 NYC general election

I've been asked by a good number of people on Bluesky and elsewhere for my voting endorsements. I've collected my voting recommendations here.

CANDIDATES

NYC Mayor: Zohran Mamdani. I was publicly skeptical of him in the primary, and I'm still not crazy about a lot of his ideas. But he's the best option in the field because he's correctly identified what NYC's problems are, and he's surrounded himself with competent people. The alternatives are far worse. Andrew Cuomo ran the subways into the ground when he was governor. Curtis Sliwa is an incoherent crank, even though some of his ideas are good and he genuinely wants the best for the city. Eric Adams, mercifully, dropped out.

Public Advocate: Both candidates suck. Jumaane Williams is a NIMBY slumlord who keeps making bad-faith commentary about how Eric Adams's rezoning plan, City of Yes, needs more "real affordability" and more "community involvement" of the kind that got us into this mess in the first place. The Republican, Gonzalo Duran, wants stronger rent control measures and even more hyperlocal control over development decisions. One is nominally a Democrat and the other is nominally a Republican but they're effectively the same on housing. Personally, I'm writing in Abby, my friend Amanda's dog. Abby is very cute, and will do no harm if she is elected.

Abby the Dog would make a better Public Advocate than either candidate.

Comptroller: Mark Levine. Levine is the kind of earnest Jewish guy who has kept the mayor's office honest, and he's been excellent on bus lanes and expanding bike lanes.

Manhattan Judges: No recommendation. I don't litigate anymore, so I can't offer public endorsements beyond the courthouse scuttlebutt I hear from friends and colleagues.

Manhattan DA: Alvin Bragg. Crime is down in NYC. I give him bonus points because Bragg had the stones to go after Trump and secure a conviction when so many other prosecutors failed.

Manhattan Borough President: Brad Hoylman-Sigal. Hoylman-Sigal supports more bus lanes and a resumption of outdoor dining, and has been an effective legislator in Albany. I endorse him wholeheartedly.

Brooklyn Borough President: Antonio Reynoso. Reynoso vocally backed City of Yes, and has consistently supported reforming the laws to address the housing crisis. He's also been really good on biking, pedestrian and transit infrastructure. I offer him my unqualified support.

City Council, District 1 (LES, Chinatown, Tribeca, FiDi): Both candidates suck. Christopher Marte, the incumbent city councilman, is awful. Marte opposed Mayor Adams's City of Yes housing plan - one of the few good things that Adams did. I loathe Adams, but credit where credit is due: City of Yes was genuinely good, and it's a shame that the City Council watered it down. Marte's also against congestion pricing. Strike two. And while he's not as openly corrupt as Eric Adams, I will note that Marte's brother mysteriously managed to get one of the first legal marijuana dispensary permits in the neighborhood at a time when those were nearly impossible to get. Strike three.

I would love to vote for someone else, but the other candidate is Helen Qiu, a MAGA pastor with a completely unserious plan to fix the housing crisis that's so stupid it's not even worth my time to break it down. Seriously, the sum total of her plan is "abolish rent control and allow public housing tenants to buy their apartments." That's not a plan or even the outline of a plan - that's a tweet.

My neighborhood deserves a real alternative, so I'm writing in Nira the Cat. Nira is a native New Yorker, a lawyer barred in CATalonia, and she lives in the district (about 15 feet away from my bedroom). Nira's extremely good at keeping my apartment rodent-free, which is a major accomplishment in NYC.

Nira the Cat, Esq. would make a great city councilor.

Nira the Cat, Esq. would make a great city councilor.

City Council, District 36 (Bed-Stuy, Crown Heights): Chi Osse. This is my old neighborhood on Brooklyn. Osse is a thoughtful councilman who has been aggressively promoting better housing policy, and Osse has clearly gotten into the weeds of how to fix the zoning and building codes. He also sponsored the law to abolish mandatory broker fees. I moved back to Manhattan a few weeks ago, but he deserves your vote.

BALLOT PROPOSITIONS

Proposal 1 (Cross-country ski trails in the Adirondacks): Planning to vote no, but open to hearing other opinions. There are plenty of upstate ski resorts already, and the State had to bail out the upstate resorts less than a decade ago.

Proposals 2 + 3 (Streamlined review for affordable housing and small projects): YES, YES, YES. New housing is forced to go through way too much bureaucracy already, and anything that can speed the process is good.

Proposal 4 (Affordable Housing Appeals Board): YES, YES, YES. Currently, city councilors have the power to veto affordable housing in their districts. Proposal 4 would strip this authority, and instead put it in the hands of a three-person committee made up of the Boro President, City Council Speaker and Mayor. This is good, because the new committee answers to the whole borough and whole city, not to just the hyperlocal concerns of one neighborhood.

Proposal 5 (Creating a new digital city map): Yes. The current official city map uses paper maps. Centralizing and digitizing this function is a no-brainer.

Proposal 6 (moving local elections to even years): Yes. Right now, NYC local elections are held in odd-numbered years, when fewer people turn out to vote. Holding local elections in presidential years increases voter turnout dramatically and reduces election administration costs. California experimented with this law and it was a huge success.

September 13, 2025

HELL YEAH. California finally legalized apartment buildings near transit, statewide. Let's talk about the consequences.

BOTTOM LINE, UP FRONT: The big rezoning bill, SB79, passed the Legislature and it is a big fucking deal for dealing with the housing crisis. Because now it's legal to build apartments near public transit, statewide.

Side note before I begin - this post is about LA, but everything about this also applies to the Bay Area.

There are two crises that California faces these days. #1 is the housing crisis, because there just isn't enough housing to match the number of jobs. The housing crisis exists because cities have made it nearly impossible to build new housing. Some suburbs, like El Segundo, Beverly Hills, and Alhambra, have barely grown in 40-50 years despite skyrocketing demand.

The State has been trying to force cities to get their shit together for decades. The State created tools that local governments could choose to build more housing on their own terms, and city councils basically shrugged. The State tried to throw money at the problem and fund new affordable housing, but city councils buried new affordable housing in red tape - it costs almost as much to build a new rent-controlled apartment as to buy a single-family home. The State tried a quota system for cities, and LA cities were supposed to build 1.3 million homes by 2029. But cities put on a dog and pony show, promptly returned to business as usual, and Newsom chickened out. LA's cities are on pace to build 467,000, less than a third of the target.

Crisis #2 is the transportation. Traffic is horrible, and public transport isn't very useful, and it's facing a post-pandemic funding crisis. Transit works in New York, Tokyo and London because because they build stuff within walking distance of the stations. If you go to LA Metro stations in Rancho Park or El Segundo ... there's just not much there.

London's train stations have stuff you can walk to nearby...

[image error]

... while LA's do not.

This year, the Legislature finally got serious. They passed laws streamlining the California Environmental Quality Act and allowing builders to get inspections done faster. (Buildings departments are legendary for being slow and corrupt.) SB79 completes the trifecta of big reforms this year. SB79 does two things: it legalizes apartments near public transit, overriding local laws, and it also allows public transit agencies to act as real estate developers on the land they own. Let's talk about what's in the bill; and here's a map of affected areas.

THE BASICS OF THE BILL.

There's two parts to the bill. There's the actual zoning standards, which a city can tweak but not override. There's also no way for a city to legally deny a building that matches the law.

1: WHAT THESE NEW APARTMENTS CAN LOOK LIKE.

Rather than giving a laundry list, SB79's key provisions are best listed as a table. Here's what you can build:

Transit typeHow close to the transit?Legal heightUnits per acreAllowable square footageWhat does this look like?SubwayWithin 200'9 stories160 units/acre4.5x the lot sizeThis building from K-townSubway< 1/4 mile7 stories120 units/acre3.5x lot sizeThis building from K-townSubway1/4-1/2 mile, city size >35,0006 stories100 units/acre3x lot sizeThis building from Pasadena-----------------------Light rail, busway, frequent MetrolinkWithin 200'8 stories140 units/acre4x lot sizeThis building from SFLight rail, busway, frequent Metrolink< 1/4 mile6 stories100 units/acre3x lot sizeThis building from PasadenaLight rail, busway, frequent Metrolink1/4-1/2 mile, city size >35,0005 stories80 units/acre2.5x lot sizeThis building from NYCSB79 buildings have a requirement to build rent-controlled units (or equivalent below-market-rate condos). It's a sliding scale, based on the income level restriction. Keep in mind, "low-income housing" is a descriptor based purely on family size and salary, not a proxy for moral fiber or anything.

Apartment typeIncome limit (family of 4)Who makes that much money?PercentageExtremely low income$45k (30% of median)a restaurant waiter (before tips)7%Very low income$75k (50% of LA median)LAUSD teachers10%Low-income$121k (80% of LA median)A Cedars-Sinai nurse13%SB79's flavor of zoning actually reflects a return to the old way of doing things. In the past, LA allowed way more to be built than today. In 1960, LA City alone was zoned for 10 million homes, and by the 21st century, that number had been cut in half. I suspect that Sacramento would never have intervened if the cities hadn't been so unwilling to change. The cities fucked around, and oh boy, did they find out.

2: TRANSIT AGENCIES CAN BUILD APARTMENTS ON LAND THEY OWN.

The second part of the legislation is that Metro, and other transit agencies now have legal authority to develop land that they own near transit stations. This isn't a big deal in the short term. But in the long term, it opens the door for one of the things that made Tokyo's transit system so good - because Japanese transit operators develop and operate real estate. 20% of Japan Rail's revenue comes from its real estate unit. This isn't a new thing in Los Angeles, either. It's actually the oldest thing in LA. The old Red Car system made their real money developing real estate near the stations. This was normal during a century ago - Oakland's streetcar company was owned by a company called the "Realty Syndicate."

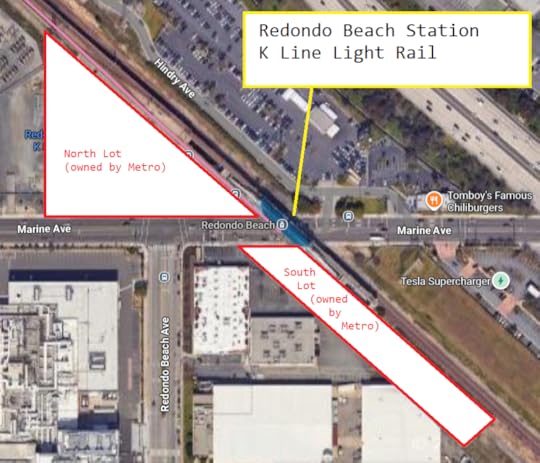

There's tons of opportunities for Metro and Metrolink to take advantage of, because much of the transit network was built as park-and-ride. Here's Redondo Beach station on the Pink Line, for example. There's four full acres of land that's used for parking lots - enough to house 2,000 people under SB79's baseline zoning.

3: WHERE SB79 DOESN'T APPLY.

Now, SB79 does have safeguards, because you don't want people to live in Bad Places. Nobody wants a repeat of the Palisades Fire. Thus, SB 79 doesn't apply to:

Fire zonesAreas vulnerable to sea level riseBuildings with rent-controlled apartmentsDesignated historic areas (with limitations to prevent abuse)These are pretty common-sense limitations, and they're probably going to have to be adjusted in the future.

THE END OF THE BEGINNING.

Now, I'm not going to say this is going to fix the housing market overnight. This is a crisis 50 years in the making. And the market is difficult, because the Administration's tariffs and immigration raids have wreaked hell on the construction industry. But it's still a big fucking deal, guys.

It's going to take more more reforms, more fixes to make LA and the Bay Area work again. But things are finally getting fixed. Let's do this.

September 9, 2025

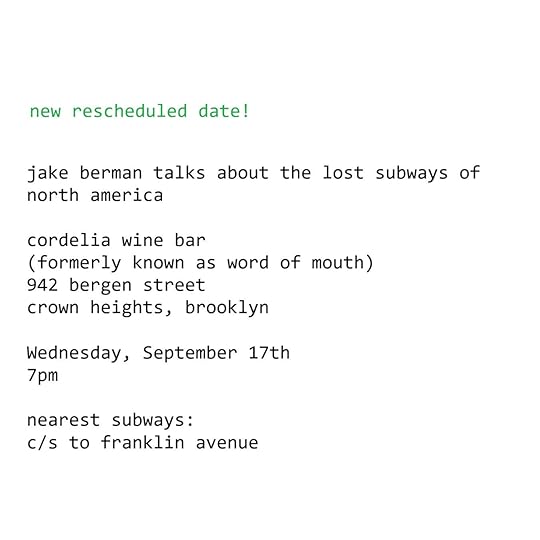

new event: september 17, 7pm, cordelia wine bar, brooklyn

the event in brooklyn that was originally cancelled is back on for next week. see you there?

note: this is a non-ticketed event; come as you are.

August 11, 2025

My Thursday event in Brooklyn has been postponed.

The venue owners have decided to do a renovation, so the book talk is postponed until we can get a new date set. I'll post here when there's a new time.

July 28, 2025

On reaching the natural endpoint of suburban development

Paul Krugman wrote a good post on Substack yesterday about how Atlanta is approaching the limits of sprawl. What I really want to nail down is how this is really a limitation imposed by road capacity more than anything else. If you build your infrastructure and your cities with only drivers in mind, you reach capacity real fast.

The gold standard for how many people you can move in any given direction is PPHPD, which stands for "People Per Hour Per Direction," for one specific lane or track.

One lane/track of......has a capacity of this many people/hour/direction.City street800Freeway2000Busway9000Bike lane12000Sidewalk15000Light rail/tram18000Subway/elevated45000

These numbers are general figures, because the details matter. (For example, Vancouver's SkyTrain maxes out around 18,000 PPHPD, using 250'/76m long trains, while the old Independent Subway in NYC was designed for 60,000 PPHPD, using 600'/185m trains.)

The math sounds ridiculous at first glance: how on earth can a single bus lane have more capacity than a four-lane freeway? But it really is so - it's just simple geometry. A picture is worth a thousand words.

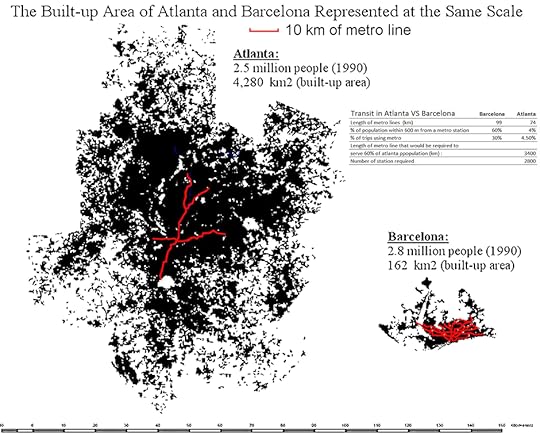

Now, think of Atlanta for a second, which is pretty much endless suburbs as far as the eye can see, and compare it to, say, Barcelona. (The map here is from 35 years ago, where traffic was a huge problem already!) And you can't densify those suburbs because of the zoning laws.

Pre-demic, over 20% of Atlanta's jobs were located in 0.7% of the land area, and it doesn't take a genius to figure out that everyone having to drive to the concentrations of jobs is a recipe for gridlock. If you rely only on the private car, there is no way short of massive urban demolition, to add more roadway capacity if you want a non-lousy commute.

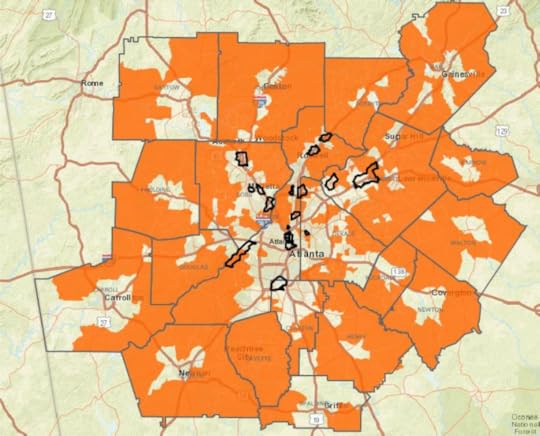

("Unaffordable" areas are orange, and the jobs-rich areas are in black.)

I suspect it's not just Atlanta that's going to have this issue going forward, because Atlanta's land use and transport patterns are so, well, normal for the United States, especially cities that came of age after the Second World War. Something has to change if we want to fix this.

June 25, 2025

Let's talk about how the California state government has reformed the California Environmental Quality Act, making it significantly easier to build more housing.

One of the big reasons that California has a housing crisis is, ironically, an environmental law, the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). CEQA (pronounced SEEK-wha) is a major obstacle to building new housing. Governor Newsom is expected to sign a reform bill on Friday exempting new urban apartments from CEQA.

Wait. How could the something called the California Environmental Quality Act possibly be bad?

Really, it's because of the law of unintended consequences. But to explain why, I'm going to first give some background on what CEQA actually is. CEQA, signed into law by Ronald Reagan in 1970, requires state and local governments to study the environmental impacts of public projects before approving them. Look before you leap, in other words.

OK. So what's so bad about studying things?

There's three problems with this, as it applies to housing. One, the CEQA studies are incredibly expensive and time-consuming, enough to make many new buildings financially unviable. Two, any crank can sue, arguing that the project hasn't been studied enough. There are no consequences for filing a meritless CEQA lawsuit, as long as you're willing to pay the lawyers. Three, CEQA as written doesn't distinguish between categories of projects. So even if a particular project is obviously good for the planet (like, say, an apartment building next to a train station), you still have to go through the whole process. This creates a whole lot of shitty incentives.

These days, the single largest source of CEQA litigation is new urban apartment buildings, as opposed to (e.g.) factories in protected habitat. CEQA has even been used as extortion. In one particular case, there was a RICO suit about this relating to a hotel in Hollywood.

Fine then. What does the reform bill actually do?

The reform bill, AB609, exempts apartment buildings in urban areas from CEQA entirely, removing the source of delay. This is a good thing - there's a housing shortage, people have to live somewhere, and it's better that you build new apartments in cities instead of subdivisions in the Mojave.

There's precedent for this change to the law as well. Before 2020, CEQA litigation was a huge impediment to improving public transit. That year, Newsom signed bill SB 288, which eliminated CEQA review for pedestrian, bike, and public transit improvements. The rationale for this change is the same. Better public transport is good for the planet, since it gets people out of their cars. No more nonsense like when the Beverly Hills school district sued Metro to stop the Westside subway extension of the D Line. I expect something similar to happen for housing.

So what's the big takeaway?

TL;DR: Eliminating CEQA review for new urban apartments is a big deal. I'd caution against expecting any immediate impact, because buildings still take too long to build and there need to be more reforms - but this is a huge step in the right direction.

June 19, 2025

Jake's endorsements for NYC Mayor

In order of how I think you should rank mayoral candidates them in the Democratic primary:

Zellnor Myrie. Brad Lander. Scott Stringer. Adrienne Adams. Zohran Mamdani.Here's my reasoning:

Zellnor Myrie is my first choice because his housing policy is the best by far, and if you're following me, you know that I support building as much housing as possible.

Brad Lander is quietly competent and also pro-housing. I voted before Trump's ICE agents arrested him on nonsense charges, but good for him for standing up for the rule of law.

Scott Stringer and Adrienne Adams are fine, and neither is Cuomo or Mamdani, so I'm comfortable ranking them 3rd and 4th. Then there's Zohran Mamdani, who I've ranked 5th. Bottom-line, Mamdani's plans in the areas I care about most - transit and housing - are a mix of impossible and ill-advised, but I'm going to hold my nose and rank him anyway.

Mamdani wants free buses. There's three major problems with this idea. First, the Mayor doesn't control the MTA, the governor does - so short of the city taking over the MTA there's no good way to implement the plan. Second, free buses are generally not what transit users want - even the poorest riders are willing to pay for service, provided that the service quality is high. Transit users, both in surveys and by voting with their fares, are generally willing to pay more for transit IF it's fast, frequent, reliable and convenient. Third, free buses deprive the MTA of revenue, at a time when MTA operations are already underfunded - making service worse. That money has to come from somewhere.

Mamdani's housing plan is also bad, full stop. A rent freeze on stabilized apartments and stronger rent controls were tried in San Francisco and they failed miserably at attacking the basic problem of not enough housing. Not to mention, 45% of New Yorkers live in market rate apartments, and a rent freeze off-loads the problem onto those people. It's robbing Peter to pay Paul.

I don't trust his promise to build 200,000 units of rent-stabilized housing either. He's promised to build all this housing with union labor, and without reforming the housing/zoning bureaucracy. This is like promising that you can get in shape without eating right or exercising.

Now, you may be wondering, if I just spent the last three paragraphs shitting all over Mamdani, why'd I rank him 5th? Well, it's because Mamdani isn't Andrew Cuomo, and Mamdani is currently running second to Cuomo in the polls.

I think Mamdani's plans are bad and ill-advised, but Cuomo's plans are even worse. After all, we know what Cuomo's record on transit is. When he was governor, Cuomo ran the MTA into the ground, and took money from the MTA budget to fund upstate ski resorts. On the housing front, Cuomo's promised to do fuck-all to fix the housing crisis. Cuomo has no business being anywhere near City Hall, which is why I ranked Mamdani 5th.

Thus, that gets you my ranking order: Myrie, Lander, Stringer, Adrienne Adams, Mamdani. If you live in New York City, you should go and vote. Election day is Tuesday.

June 15, 2025

A primer on what it takes to publish a book

The first step is to write something really, really good and finish it. Be willing to self-reflect, get feedback and cut things that don't work or serve the larger purpose of the book. (I actually ended up cutting my favorite chapter, which involved the Army being deployed to the streets of Denver to stop a streetcar strike.) Once your manuscript has been polished, then the publishing process starts.

SELF-PUBLISHING VS. TRADITIONAL

The first decision you make once your manuscript is done is to figure out whether you want to publish traditionally, i.e., through a press, or by self-publishing. (There's also something these days called "hybrid publishing," which is somewhere in between.)

I think most authors should at least consider self-publishing, even if they don't end up going that route. Self-publishing is faster, gives you more control over the end product, and if it sells, you make more money, usually between 50% and 70% of the gross. The tradeoff is, you assume 100% of the risk if it doesn't sell, self-publishing still carries a stigma, and managing your book project is all on you. And I mean everything, from editing to layout to cover design. At worst, you may be out tens of thousands of dollars, and be stuck with a garage full of unsold books. You also run the risk of being taken for a ride by your vendors - since you're paying out of pocket, you ARE the product.

Traditional publishing takes a lot longer. I submitted my proposal to University of Chicago Press in October 2021, signed the contract in April 2022, finalized the manuscript after editing in March 2023, and the book was released to the public in November 2023. You make less royalty money, as well. 10% of MSRP per copy is more-or-less standard. The MSRP price of Lost Subways is $35, so I make $3.50 for every copy sold.

The good part about traditional publishing is, the financial risk to the author is zero. it costs the author nothing but their time, and the publisher absorbs the cost of editing, distribution, book design and inside marketing. (Note: when I say "inside marketing," I'm talking about the inside baseball of book marketing - getting reviews from the trade press, selling it to libraries, getting it on shelves and managing inventory.)

WHY I PUBLISHED TRADITIONALLY

I chose to go the traditional publishing route for three reasons. First, I was making serious points about transport and housing, but I'm a lawyer by trade, not a planner or an academic. Publishing the book traditionally gave me credibility within the urban planning space. When talking to the media, I was able to name-drop the University of Chicago Press, so reporters knew that I wasn't just some crank. Second, my publisher was able to draw on tons of subject matter experts to edit and review the book. Third, because The Lost Subways is a coffee table book - albeit one that required a dissertation's worth of research - printing it is expensive. It would have cost me $20,000 of my own money to print 1000 full-color paperbacks. It cost $0 of my own money to print The Lost Subways in hardcover. (Caveat: this is not the case for most authors; text-only books are much cheaper to print, and your marginal distribution cost of an e-book is zero.)

HOW TO GET A TRADITIONAL PUBLISHER

The usual first step in finding a traditional publishers is to find a literary agent. Ideally, your agent is one who represents authors in your field. If you don't know anyone with an agent, a good place to start is to find books that are comparable to yours, and check the acknowledgments. Authors usually thank their agents there. Major publishers generally won't accept un-agented manuscripts because there's just so much junk out there. There's also a standard format for contacting agents called the "query letter" - the agent Jane Friedman has a great guide to this. (She also wrote a corresponding for fiction.)

The industry standard is that your agent takes 15% of your royalties. Trustworthy agents don't charge up front. If a prospective agent is asking for money, assume they're a scammer and move on.

Once you've got an agent, the agent will shop it around to publishers. A good agent will keep you posted on where they're at, but the publishing business is conservative and slow when it comes to these things, especially if you're a first-time author.

Expect a lot of rejection, both when pitching agents and then when pitching publishers. The rule of thumb I've heard is that one in 50 submitted manuscripts gets an agent. Of agented manuscripts, half are published. A word to the wise: if an agent gives you substantive comments on your manuscript, but declines to represent you, you should seriously consider incorporating their feedback. They've seen more manuscripts than you can count, and more importantly, they know what sells.

I was lucky, because a family member knew a reputable agent who was interested. All the same, my agent had no luck pitching The Lost Subways to publishers. On my initial go-around, I got rejected by 25 different publishers, after which my agent and I went our separate ways. (The original book was meant to be a simple coffee table book, rather than a coffee table book with bunch of #longreads about cities and full citations.) After this initial round of failure, I junked the first manuscript entirely and started again from scratch.

On my second try, I decided to go it alone. In this go-around, I ignored the major publishers entirely and focused on niche publishers: academic and architectural presses. There, an agent isn't necessarily required, and there's more willingness to look at specialty products. University of Chicago Press is where I hit paydirt.

OKAY, SO WHAT ARE PRESSES LOOKING FOR?

Simple. Publishers want to know that your book will sell. This is a business, after all. You need to submit a proposal with your manuscript showing how you plan to sell books. The traditional sales target for a new author is 10,000 copies, though your mileage may vary. (For example, with academic books where the target audience is other academics, the target number is usually smaller.) Your job is to show that you have a platform - i.e., that you're someone influential enough to be worth listening to. Being prominent in your field or having a huge social media following are obvious ways to do it, but this category is notoriously squishy. Personally, I showed that with a combination of traditional media exposure, a lot of viral Reddit content, and a profitable subway map business that I had built from scratch. After some discussions with University of Chicago, we got down to brass tacks.

COOL. WHAT THEN?

If they make you an offer, you start the contracting process, which is where a good agent will help negotiate; there are good guides to this online as well. If you're a first time author you generally don't hire a lawyer because lawyers are so damn expensive and publishing contracts are relatively standardized. You probably won't have much leverage to negotiate in this stage, because it's rare to get more than one offer at a time.

At this point, publishers usually offer you an advance against royalties, which is a lump sum paid half up front and half on delivery. For new authors, it's usually not a big chunk of change given how much work goes into it. (You see million dollar advances for celebrity memoirs, politicians' books and other stuff with a guaranteed audience, but for new authors it's often less than $10,000.) I'll give a worked example to show how this operates.

Let's say that I sign a book deal for a $10,000 advance with a 10% royalty rate. The cover price is $35, so I make $3.50 in royalties per book. This means that I get no royalties for the first 2857 copies of the book sold, because the publisher already paid out that amount as an advance. After the contract is inked, you send the manuscript to the publisher.

Then the editing process begins. My editors at UChicago did a ton of smart, thoughtful editing, and even the copy-editor they brought in was an urban planner. They also sent out my book for peer review by experts in the field. (This happens at academic publishers, but not with commercial ones.) Once all of that editing and back-and-forth was done, THEN we finally went to production.

Notably, most publishing contracts give the publisher the right to design the cover and name the book. University of Chicago gave me a lot of input into the cover design, and they liked my suggested title, but strictly speaking, they could've named the thing Revenge of the Zucchini People if they wanted to.

After all of this saga, the book has its release, and the marketing begins. This is a huge adjustment to go through as an author. Writing is such a lonely thing - and then you're expected to promote the book on social media, talk to the media, arrange events and so forth. (UChicago Press did assign me a staff publicist, who was great, but this is not the norm in academic publishing.)

SO... YOU'RE EXPECTED TO DIY ALL YOUR MARKETING?

Kind of. In my particular case, about 1/3 of the media appearances came through my publicist, as well as a handful of major institutions that wanted me to give a talk, like the 92nd Street Y in NYC and the Cleveland Public Library. In addition, University of Chicago Press did the yeoman's work of getting the publishing industry press (Booklist, Publisher's Weekly, Kirkus etc) to review the book. Libraries bought up a lot of the initial print run because of an excellent review in Booklist.

The rest was all me. The days of a publisher scheduling book tours are long-gone unless you're a celebrity, and if you're a celebrity, you're probably not reading this post looking for advice. Instead, my book tour was basically made up of me emailing bookstores, museums, libraries, and advocacy groups in places I was already going to be. I specifically scheduled my stops in LA, Boston, DC, Sacramento, and SF to coincide with my holiday travel plans. A few places gave me an honorarium, but for the most part, all of this travel was out of my own pocket. I'm thankful that my day job was fully remote at the time, and that I had friends and relatives willing to host me.One thing I highly recommend when marketing your book is to not be stingy with review copies. Sending free copies to influential people in the transit and housing fields often has resulted in me making all of my investment back and more. It pays to be generous.

COOL. SO, NOW YOU'RE ROLLING IN THE BIG BUCKS, RIGHT?

In a word, no. The Lost Subways of North America has sold 10,000 copies, which is the benchmark for whether a book has long-term staying power, but less than 10% of traditionally published books ever get this far - the majority of books sell less than 1,000 copies. (A few mega-hits keep publishers afloat, the top 10% of books turn a profit, the next 15% break even, and the rest lose money.) I'm incredibly fortunate to have hit that milestone. But in real money terms, we're talking about $35,000 in royalties, before taxes, for a book that took over a decade to write. There's no use sugarcoating it: getting a book published at all is a huge achievement, but don't expect to get rich doing it.

In financial terms, however, the book has gotten me a whole lot more paid writing and design gigs. It's surprisingly common to use books to open doors like this. Many business books, for example, are basically treated as a business development expense. Or, if you're an academic, you often have to publish a book to get tenure. But for me, it really was because I felt that I had something to say. When my release date hit a year and a half ago, I said to myself that I would be happy with the result even if it flopped - even if it didn't vibe with the public, I created something I could point to and be proud of. Writing and researching the book has given me the opportunity to travel the continent, talk to people who care about transport and housing, and learn about the way other people live.

In the end, when I look in the mirror, was it worth it? Absolutely. I wouldn't be writing this if I didn't think so. But there was a lot that I wish I knew when I was starting out.

May 14, 2025

Let's talk about how poorly LA is meeting its state housing quotas.

Bottom line, up front: the quota system has been as toothless as the old quota system, and more aggressive measures are needed to build more housing.

A few years ago, I was hopeful that the new state housing quota system would get LA's cities to get off their tuchuses and build more housing. I'm sad to say that I was wrong.

Let's go back a few years to 2021, where the state established that Greater LA needed 1.35 million new units between 2021 and 2029. The grand total permitted, halfway through this eight-year cycle, is 132,839, less than 10% of the need. Now, the quota system has separate tiers for rent-stabilized housing, and it's pretty damned dire - 5.6% of the quota has been met for low-income housing, and 2.6% for moderate-income, and 2.5% for very-low-income housing. The bulk of new construction has been market-rate, and there's nowhere near enough of it.

There are a few cities making good faith efforts to actually fix the crisis. Santa Ana, for example, gets a gold star for doing its part. But most cities, for better or for worse, have decided that that they continue with business as usual. West Hollywood has met 17% of its market-rate quota, and less than 1% of its new rent-controlled quota. Beverly Hills has made 15% of its market rate quota, and built exactly two new rent-controlled units in this time. Manhattan Beach has met its market rate quota, but they've built exactly zero new rent-controlled apartments.

The root causes have already been discussed at length on this blog - over-strict zoning regulations, city planning and building departments that make it virtually impossible to build anything new, chickenshit Sacramento politicians who aren't willing to actually enforce the law and crack down on cities that refuse to build housing, and so on. And, of course, there's the underlying issue of LA continuing to add new jobs far faster than it adds new housing - it's been a well-known fact since at least 2001. All those workers have to live somewhere.

So, let's talk about what reforms that have actually worked, and what we can extrapolate from this. The ADU one is the biggest one, and the reason the ADU reforms have worked is that they're bureaucratically simple. If you own a house, you can build an ADU there, full stop. The laws are relatively uniform statewide, and the laws are relatively simple to comply with, so you don't need an army of lawyers to navigate the bureaucracy. This is actually how apartment construction used to be - it's how LA got the cheap, adequate dingbat apartment that's practically everywhere in SoCal built in bulk. And that's the key - straightforward regulations that allow people to do copy-paste urban housing like we did in the old days.

Will the cities do this? I doubt it, because there have been no political consequences for violating the law. Technically, the State can void the zoning of cities that aren't pulling their weight. Which means that the Legislature is going to have to pass new laws to strip local control. There's SB79, which would directly rezone land located near train stations and other transit to allow apartment buildings, so you don't end up with crazy stuff like the Westwood-Rancho Park station on the Expo Line. There's AB609, which would exempt new urban apartments from the California Environmental Quality Act. (For those of you who aren't aware, lawsuits under CEQA, which is meant to protect the environment, is routinely used to block new apartments and transit - half of all new housing faced CEQA threats.) Then there's AB253, which would accelerate building permit issuance. LA DBS and other city buildings departments are notoriously slow and corrupt, and AB253 would fix it.

So there is hope, but there's going to need to be a lot more reform in order to get us out of this mess.

April 9, 2025

My review of the new NYC subway map is out!

Check it out at Vital City.