Foster Dickson's Blog

November 25, 2025

Dirty Boots: Y’all come back now, y’hear?

Brain drain is massive problem in most of the Deep South, and the phenomenon is not new. When my friends and I were finishing school in the 1990s, the inarguable sentiment among us was that leaving Montgomery, Alabama was the only viable option for a good life. And many of us acted upon that assumption. (Of course, I didn’t, but that’s another story.) Among my classmates at the Carver Creative and Performing Arts Center were actor and artist Ashley Longshore, and I can say with complete certainty that neither would have achieved the same things had they stayed here. Yet it is also important to recognize that this was brain drain: our local community had these talented people, and we lost them to other communities. Today, my mind wanders to what any of those creative and intellectually curious people could have created here where we came from. Of course, for those of us who have stayed, some have found ways to earn a living in the arts and culture sectors of the economy – where our skills and talents lay – but many have not.

As a larger-scale example of brain drain, the statistics provided by Rethink Mississippi are startling. According to their website, of the adults who leave the state, 40% have a bachelor’s degree, and of those who stay only 21% have a degree. Sixty-six of the state’s eighty-two counties had a net loss of population between 2010 and 2020, due largely to outmigration, a circumstance often attributed to a lack of economic opportunities and cultural offerings. Perhaps most startling: the number of other states who showed a net loss of population in the 2020 census— zero.

While Mississippi may be alone in their standing as the only state to experience net population loss, they are far from being alone in suffering from brain drain. In May 2024, al.com reported on a study that showed Alabama ranking tenth-worst in the nation with this problem: “more well-educated residents are leaving the Yellowhammer State than are moving in – 45% more in 2023, to be exact.” That means that we’re losing two educated people for every one we gain. A list later in the article shares that Mississippi ranked second-worst and Louisiana fourth-worst. (As a complete outlier, South Carolina was the only Southern state in the top-ranking group: second in the nation with a 137% net gain.)

Brain drain is not something a community or a state can always recognize directly and daily, like they would a food desert, but it is a problem with real-life effects. When I taught high school, I used to remark to my students how badly our state needed them to stay, live, and work here once they had finished their degrees. Almost all of them shrugged off the notion; some outright laughed at it. But a few gave me the opportunity to explain. Most of them had attended public schools for K-12, meaning that our people had invested tens of thousands of dollars in educating them over thirteen years. Then if they went to college, especially to a public university, and even more especially if they received scholarships, we would be investing tens of thousands more in them— all without any binding obligation or contract that would hold them in place. What a gift! So, if they were born with God-given talents and skills, then added the education and enrichment that the people of Alabama provided, but went on to use and apply those skills elsewhere . . . the Alabamians who’ve invested in them, intentionally or generally, get nothing for our investment. Moreover, people with college degrees tend to earn higher salaries than those without, so by leaving, they would be paying their higher taxes in another state, not in ours. Brain drain leaves people in affected states with the task of educating the next generation with reduced tax revenues, which hampers that next generation from having the opportunities that the last generation enjoyed . . . A few students recognized that I had a point. Continuity, even stasis, becomes more difficult when educated people leave.

Brain drain is not something a community or a state can always recognize directly and daily, like they would a food desert, but it is a problem with real-life effects. When I taught high school, I used to remark to my students how badly our state needed them to stay, live, and work here once they had finished their degrees. Almost all of them shrugged off the notion; some outright laughed at it. But a few gave me the opportunity to explain. Most of them had attended public schools for K-12, meaning that our people had invested tens of thousands of dollars in educating them over thirteen years. Then if they went to college, especially to a public university, and even more especially if they received scholarships, we would be investing tens of thousands more in them— all without any binding obligation or contract that would hold them in place. What a gift! So, if they were born with God-given talents and skills, then added the education and enrichment that the people of Alabama provided, but went on to use and apply those skills elsewhere . . . the Alabamians who’ve invested in them, intentionally or generally, get nothing for our investment. Moreover, people with college degrees tend to earn higher salaries than those without, so by leaving, they would be paying their higher taxes in another state, not in ours. Brain drain leaves people in affected states with the task of educating the next generation with reduced tax revenues, which hampers that next generation from having the opportunities that the last generation enjoyed . . . A few students recognized that I had a point. Continuity, even stasis, becomes more difficult when educated people leave.

Brain drain can also be tied to losing our “sense of place.” This term describes how we feel connected to some geographic locations because of what we experienced there. Connecting the two ideas, we can see a wrongheaded conclusion: if I don’t see modern economic and cultural opportunities in the place where I’m from, then that place must have nothing to offer. This assumption is supported by the often-stated belief that those who “got out” have succeeded. And so those who have stayed . . . must have failed?

This either-or mentality excludes and denies the pertinent lessons of bioregionalism, an idea that emphasizes human cooperation with and appreciation of nature and each other in localized settings. Writing for the Schumacher Center, author Kirkpatrick Sale offered this:

The concern for place, for the preservation of nature, the return to such traditional American values as self-reliance, local control, town-meeting democracy—these things can ally many different kinds of political people; in fact, they have a way of blunting and diminishing other and less important political differences.

If we manage to define a “good life” not by political gains or material wealth, but instead by the desire for harmonious co-existence and appreciation of local culture, the driving forces behind brain drain could be blunted. In a bioregionalist view, it makes no sense to leave the best things in life – family, community, and local traditions – for the possibility of wealth, social prominence, and media culture, which are less valuable (even though they’re certainly enticing). If Deep Southern states have anything to offer, it’s what a bioregionalist says is best: family, community, traditions, and harmony with nature . . . Just sayin’.

For brain drain to slow – or hopefully stop – people in an area need to see two things when they look around them: a culture worthy of life-long participation and sustainable economic opportunities. The first of those has to come from the ground up. Having that understanding could mean giving our young people reasons to stay and bringing back some of the people who’ve left. The second of those can come from the ground up, but has to be supported by the policies of state and local governments, especially in the area of economic development. If we want community, we’ve got to work with each other locally, instead of looking to extractive and corporate interests to discern our path forward.

November 13, 2025

Throwback Thursday: “Sherman’s March,” 40 Years Later

I promise, no one is ready for Sherman’s March the first time they see it.

Ross McElwee’s quirky documentary Sherman’s March was released forty years ago today, on November 13, 1985. One might assume from the title that it’s a film about . . . Sherman’s March, the one to the sea, during the Civil War, after the burning of Atlanta. And it kind of is, but not really. It’s also about a guy who got a grant, who struggles with relationships, and who has some uncertainties that center on Burt Reynolds and nuclear war. Though McElwee was going to make a movie about the historical events of William Tecumseh Sherman’s military campaign in the mid-1800s, he instead wandered off in a different direction when his girlfriend broke up with him. The film’s subtitle “A Meditation on the Possibility of Romantic Love in the South During an Era of Nuclear Weapons Proliferation” probably comes closer to describing the content than the title does.

In a September 1986 article in The New York Times titled “When Film Makers Play It by Ear,” writer Annette Insdorf puts it this way:

His sister suggests to him that he use his camera as a way to meet women. This turns out to be a successful strategy, as seven all-too-real Southern females wander into Mr. McElwee’s path, lens and heart: a vapid actress, a right-wing interior decorator, a linguist who lives on a deserted island, an anti-nuclear activist, a Mormon folksinger, a rock singer, and a former love who is now a lawyer. They do not seem fazed by the fact that they are being pursued by a camera as well as a man.

[ . . . ]

In this American landscape where Burt Reynolds is the main idol and anti-Communism the main ideology, the film maker’s quirky sensibility captures lines and images more amazing than fiction.

Sherman’s March is one of those movies that makes us ask, What the hell am I watching? Through minutes-long scenes of McElwee in a studio apartment talking on the phone or through awkward scenes when he is on a date while holding a big 1980s video camera on his shoulder, viewers are carried through episodes of seeming randomness, punctuated by this guy’s sister fussing at him, for about an hour and a half. Then, when it’s over, we go, That was brilliant.

I heard about Sherman’s March much later, in the early 2010s, from filmmaker Andy Grace. In the fall of 1985, when the movie was released, I was in the sixth grade, so it wouldn’t have been my thing. Later, with some hindsight on the ’80s and with some experience with love and art, I recognize this film for its offbeat greatness. For fans of cult classics and other GenX ephemera, I highly recommend it.

October 2, 2025

Southern Movie 79: “Trash Humpers” (2009)

Though he was born in California, director Harmony Korine grew up in Nashville, Tennessee and in New York City. After the success of 1995’s Kids then of 1997’s Gummo, it was in Nashville where he made the bizarre, low-budget Trash Humpers, which was released in 2009. The movie only runs an hour-and-fifteen, and it follows the absurd exploits of an elderly trio who go around the suburbs drinking, destroying things, causing problems, and of course, feigning sex with garbage and other inanimate objects. In its lead-in to a May 2010 interview with Korine, Nashville’s Tennessean called this one “a film that almost defies categorization: an unsettling document of stylized lives lived without regard for narrative structure or decency.” Trash Humpers, which is made in the style of a 1990s VHS home movie, is very weird and possibly pointless, but with Harmony Korine . . . that might just be the point.

Trash Humpers opens with footage of three people, who are either standing in front of a garage door or are humping trash. They are clearly actors in the kinds of clothes that old people would wear, and they have on masks or makeup. (Once we see them moving around, they are clearly not elderly.) We immediately ask ourselves why they are doing what they are doing: dry humping garbage cans and garbage bags on the side of the street, while grunting and groaning. One man attempts sex with a thick wisteria vine on a fence, while another gives a blowjob to hanging tree branch. By the end of this introductory scene, the grotesque tone is set.

Next, the ridiculous antics continue. In daylight, we see the two men in an abandoned house using an axe and a hammer to destroy TVs and knock holes in walls. We assume that the woman is holding the camera as they do this. From there, they are in a parking lot, drinking and sitting around. One of the men lays in the bushes. When night falls, they watch a local soccer game from afar, clean their wheelchair in car wash stall, and then destroy a TV and a boom box in another parking lot. By now, the actors are actually talking, laughing, hooting, and taunting the inert electronics as they kick them and dance around. They finish the scene by throwing cinder blocks from a nearby pile.

Our story – if we want to call it that – moves on. Now, the characters are playing basketball on an outdoor court. Soon, a chubby boy, who is probably eight to ten years old and wearing a black suit and tie, is out there with them, and they laugh at him as he misses baskets. Our view then shifts, and we watch the three half-mumble, half-sing to a baby doll in a clear plastic bag, while the boy stands by. The boy is uncomfortable at all this, but he becomes the strangest of the characters in a moment. Next, they are all sitting in the grass, while the boy explains how to put a child in a plastic bag and shake it. He laughs as he does this. But then it gets worse. From there, he is on a tennis court with a hammer and begins to demonstrate how to he will kill it, beating the doll in the head and body with the hammer. Once again, he laughs while he does this. Even though we know, by this point, that what we are watching is utterly absurd and fictional, it’s still hard to watch a kid smash a baby doll with a hammer while he laughs and proclaims, “I told you I’d kill it!”

Keep in mind: we are only about eleven minutes into this film, which goes on for an hour and fifteen.

Once the boy is through beating the doll, he is sitting in the old woman’s lap in the wheelchair. She is showing him how to put a razor blade in an apple, so the person will not realize it’s there until they’ve swallowed the blade. Nearby, the two old men are passed out on the pavement with empty wine bottles lying next to them. Across the grassy lot, two men run by, and the camera catches them in the background. Yet, they return to action as the boy has one old man pulling him and the woman by a strap around one old man’s neck. The boy again cackles.

That night, the two old men return to humping trash, while the old woman watches nearby. She appears bored and almost asleep. Through the night, they do some humping, which includes tearing off some tall flower stalks and acting like they are jerking them off.

After a few more random scenes of trash humping, we find our three characters back at what appears to be an apartment complex, possibly a nursing home. We are shown two new characters: grown men in surgical gowns with pantyhose stretched between their heads to imply that they are conjoined twins. First, the twins hang in a tree for some unknown reason, while one’s butt is exposed to the camera, then they are in a small apartment making pancakes. They argue over when and how to put the butter on. After a moment, our elderly trio are sitting at a card table in the apartment den clanging their silverware on the plates and demeaning to be served pancakes. The twins bring a stack, but the elderly woman stands up and beginning shouting not to eat them because they’re poisoned. She is cussing up a storm and demands that the conjoined twins sit down and eat the pancakes covered in dishwashing soap instead of syrup. By the time they’re actually eating, the old woman starts ranting about poison, and the twins are encouraged to eat the soap-covered pancakes.

Next, the five bizarre characters are in a basement. Some of the elderly characters appears to be sleeping on the cold floor, while the twins rant nonsensically. For part of this, one of the two is separated, standing on his own without the connection headwear. In the corner, one the elderly characters is humping the side of a refrigerator.

Then, elderly men are in different clothes and are in a bedroom or hotel room with three women, possible prostitutes. Two are white and one is black, and the indiscernible nonsense continues. This appears to be something of an orgy, which ends with the women petting the two men as someone sings “Silent Night.”

We’re still not at the half-hour mark yet . . . From there, our three characters sit in the home of a middle-aged gay man who tells stories and demonstrates his neck exercises. After that, in the daylight, one of the crew is seen in a Confederate flag t-shirt as he begins humping a large tree, then we spend a minute or so looking at a naked man’s face-down body, lying among rocks and bushes, while someone sings in the background. Once again, we jump inexplicably to the three walking down the railroad tracks, but are then joined by an older man – an actual older man – in a French maid’s costume who is first playing guitar than ranting at them on an overpass bridge. In the next scene, French maid guy is dead in the kitchen with his throat cut.

We’re still not at the half-hour mark yet . . . From there, our three characters sit in the home of a middle-aged gay man who tells stories and demonstrates his neck exercises. After that, in the daylight, one of the crew is seen in a Confederate flag t-shirt as he begins humping a large tree, then we spend a minute or so looking at a naked man’s face-down body, lying among rocks and bushes, while someone sings in the background. Once again, we jump inexplicably to the three walking down the railroad tracks, but are then joined by an older man – an actual older man – in a French maid’s costume who is first playing guitar than ranting at them on an overpass bridge. In the next scene, French maid guy is dead in the kitchen with his throat cut.

By this time, we’re at about forty-five minutes with a half-hour left to go. At the risk of minimizing the fact that the absurdity and nonsensical rambling continues unabated, I’ll share a bit about the remaining “plot,” since it’s very difficult to summarize a film like this one. From here, we get a weird birthday party scene where a guy is playing Neil Young-esque guitar licks, another middle-aged man playing trumpet in the bed, yet another older man playing acoustic guitar in his living room, some driving around, some breaking of fluorescent lightbulbs, some bike riding . . . and of course, some trash humping.

The way the film ends is just as disturbing as we’d expect. After intermittently abusing a plastic baby doll throughout the movie, we see the old woman character with a real baby and stroller. She starts inside the house as the baby twists and squirms in her arms, then she takes it outside into the night. The credits appear. Even though we know this has all been staged, we still think, Oh crap, somebody get that baby away from her!

As a document of the South, Trash Humpers gives a glimpse into an otherwise overlooked nook within the larger scope of modern Southern culture: the dark humor of disaffected Generation-Xers who grew up in a generally dull, conservative suburban culture. We all know about William Faulkner and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Ernest Gaines, and we all know about the Civil War and the Depression and the Civil Rights movement. When I watch this film, I see a South that I recognize. I see the sense of humor and the weirdly antagonistic playfulness of the skaters, punks, and others who I knew growing up in the 1980s and 1990s in Alabama. As far as we were concerned, there was nothing to do, because nothing around us resembled the vibrant popular culture that we saw on MTV, so we created our “fun” out of what we had. In that vein, I understand how Harmony Korine (who is a year older than I am) and his friends came up with this idea, performed in these bizarre ways, and put it all together in the most undesirable packaging they could imagine. In fact, according to the Trivia section of the movie’s IMDb page:

Harmony Korine had at one point considered leaving the film on unmarked VHS tapes left in random locations to be discovered as a mystery to the unsuspecting public. Korine also considered distributing the film via mailing it to police stations, but this idea was abandoned when such a release strategy would mean the film would not retain copyright.

Some people will watch Trash Humpers and say, “That’s not Southern.” Oh yes, it is! It’s not stereotypically Southern. It’s not canonically Southern. It stands aside from approved features like white-columned mansions, quaint town squares, swarthy demagogues, old black men on porches, and overall-wearing banjo players. Because one aspect of storytelling is eliminating the parts that don’t fit with the larger narrative in the way you want to tell it, some parts do get left out. Today, we call that being “marginalized.” Well, when watching Trash Humpers, we’re looking at “marginalized” Southerners: disruptive, destructive, disaffected white kids who grew up after the twentieth century’s massive social upheavals, bored in the Sunbelt South’s strip malls and suburbs. The GenXers I describe are not the faux elderly characters on the screen— they are the people who thought up these characters to alleviate the boredom of what many considered to be a desirable life. And they’re just as much a part of Southern culture as any guy in a plaid shirt and jeans riding around in a truck and listening to the latest country hits.

September 25, 2025

Dirty Boots: Honoring bell hooks

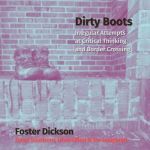

I’m reminded often of how badly we need public intellectuals like bell hooks, now more than ever. Though she passed away in 2021, bell hooks – whose given name was Gloria Watkins – left behind more than three dozen books and countless other expressions of her ideas, including dialogues and media appearances. In works like Feminism is for Everybody, Belonging, Teaching to Transgress, and All About Love, she articulated a vision of equality that could empower everyone and that anyone could relate to.

I’m reminded often of how badly we need public intellectuals like bell hooks, now more than ever. Though she passed away in 2021, bell hooks – whose given name was Gloria Watkins – left behind more than three dozen books and countless other expressions of her ideas, including dialogues and media appearances. In works like Feminism is for Everybody, Belonging, Teaching to Transgress, and All About Love, she articulated a vision of equality that could empower everyone and that anyone could relate to.

Consider an example from the opening chapter of her 1994 book Teaching to Transgress, titled “Engaged Pedagogy.” When I taught twelfth-grade English at an arts magnet school, I used to do a weeks-long unit on critical thinking, and “Engaged Pedagogy” was one of the readings that I handed out. Among the passages that I spent class time on was this one:

During my twenty years of teaching, I have witnessed a grave sense of dis-ease among professors (irrespective of their politics) when students want to see them as whole human beings with complex lives and experiences rather than simply as seekers of compartmentalized bits of knowledge.

bell hooks reminds readers that students need to see their teachers as human beings first and foremost, instead of as authority figures forcing “bits of knowledge” onto them. When this change is first permitted then actually does happen, the classroom becomes a more humane place, where learning can be a life-enhancing activity rather than drudgery or rule enforcement.

Or this brief sentence from the book Teaching Community: “There are serious taboos against acknowledging shame.” We’ve all done things that we wish we hadn’t done, and it’s uncomfortable to have those actions returned to our attention, or worse, held up for public scrutiny. So, what do we do? We suppress anything that could be embarrassing, refusing to deal with it. But sometimes facing it is what needs to happen for meaningful healing to be possible and for meaningful change to occur. We often avoid this, though, because fear and anxiety warn us that compassion will be absent and that forgiveness will be withheld. But what if they weren’t? What if we could enter the pain of facing our worst actions, knowing – because the lived experience of understanding and love had shown us – that, in doing so, we would clearly be moving toward salvation?

I could keep offering passages and quotes for consideration, but instead I’ll urge anyone who is willing to read at least one of her books. In them, a reader will find startling levels of compassion alongside intense moments that are challenging. In Belonging, she acknowledges the difficulty of being a modern black feminist whose rural Southern roots are difficult to reconcile. In All About Love, she parses the differences between a parent genuinely loving their children while doing things within the family that are not acts of love. In Teaching Critical Thinking, we read about her views that learning is a journey that teachers and students take together, a process that improves the lives of all involved. What is wonderful about her work is that, as any good teacher will, she offers us support and encouragement alongside difficult lessons that can help us to grow.

In honor of her birthday – today, September 25 – I wanted to share those few words and also recommend this 2024 episode of American Experience, “Becoming bell hooks.” Listening to her reminds us that every choice doesn’t have to be about deciding how we can win or succeed or decide whose side we’re on.

As a side note, if you really like bell hooks and have a good sense of humor, I highly recommend the Instagram account @savedbythebellhooks, which juxtaposes quotes from her work with the TV show Saved by the Bell.

September 18, 2025

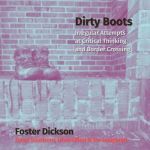

Throwback Thursday: The Textbook Squabble, ’80s style

This article appeared in the September 18, 1985 edition of The Alabama Journal, Montgomery’s now-defunct afternoon newspaper. An astute reader will see similarities between today’s disputes over how certain people and groups are represented and over what are acceptable representation for schoolchildren and these disputes from forty years ago. I thought it was particularly tactful of this journalist Susan Hurst to write that “the Civil Liberties Union of Alabama, the National Organization for Women and the Eagle Forum gave diverse testimony [italics mine] this morning . . .” Yeah, I’ll bet.

September 11, 2025

Dirty Boots: The Books in Our Classrooms

Because I live in the 21st century like everybody else, I also experience our modern culture and media outlets pushing us to pay attention to what is new. We spend a lot of time nowadays in a quasi-cultural vortex, spinning around among the cultural and economic forces that shape us and that we ourselves shape: producers produce what their data tells them consumers will consume, the media needs something to say so they jump on the task of getting the message out, and ordinary people work as hard as we can to bring home the money to buy the new things that are being marketed and talked about. In the realm of books and reading, this set of cultural forces points to embracing what is recently created, published, or released: popular novels, YA about marginalized people, biographies of entertainers, political memoirs, whatever other cause célèbre.

I would rather if we give more attention to books that are proven to be worthwhile and less attention to new trends. Let’s be honest, the folks who push this consumption-centered way of life are doing it because they need us to buy things, constantly. But what a world we’d have if we spent more time considering ideas that have stood the test of time! Or if we pondered our common humanity instead of our current differences or our own individuality! What if . . . we stepped out of that all-American cycle of prioritizing what is Now! and Me! in favor what is long-lasting and universal . . . Our perspectives would certainly change, probably for the better.

I would rather if we give more attention to books that are proven to be worthwhile and less attention to new trends. Let’s be honest, the folks who push this consumption-centered way of life are doing it because they need us to buy things, constantly. But what a world we’d have if we spent more time considering ideas that have stood the test of time! Or if we pondered our common humanity instead of our current differences or our own individuality! What if . . . we stepped out of that all-American cycle of prioritizing what is Now! and Me! in favor what is long-lasting and universal . . . Our perspectives would certainly change, probably for the better.

This comes into play in a significant way when we’re talking about the books we use in our schools. Ignoring for a moment the politicized squabbles of late, literature teaches us lessons, and when we see that those ideas from the past are relevant in the present, that recognition can help us to transcend our differences. However, there’s a perilous tightrope to be walked when considering my suggestion. TS Eliot put it this way in his essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent,” which was published in 1919:

Yet if the only form of tradition, of handing down, consisted in following the ways of the immediate generation before us in a blind or timid adherence to its successes, “tradition” should positively be discouraged. We have seen many such simple currents soon lost in the sand; and novelty is better than repetition. Tradition is a matter of much wider significance. It cannot be inherited, and if you want it you must obtain it by great labour.

In the American South, tradition is a concept of utmost important. Ours is a conservative culture that relies heavily on the past as a source of wisdom. That, in turn, has also resulted in our now-infamous levels of resistance to change. The problem with our conservatism – and with the modern concept of “traditional values” – lies in what Eliot calls “a blind or timid adherence to its successes,” which “should be discouraged.” If we ignore the failures of our traditions, we can’t repair them and do better.

Though he is sometimes decried as a neophobe and even a racist today, the late Harold Bloom had a good perspective on these issues. In “An Elegy for the Canon,” the introduction to his 1994 book The Western Canon, Bloom wrote against then-new calls for updating the “list” of “accepted” books that are taught in schools. (I use quotes here because there is no such list, nor much agreement about which books would be on one if there was.) Bloom believed that individual readers, not society at large, decide what is good and what is valuable, so he rejected calls for a socio-political solution to the dilemma. Ultimately, thought Bloom, what is truly worthwhile would appeal to many people, would survive the test of time, would stand up to criticism, and would thus remain well-known beyond its own era. He wrote, “All that we can do now is maintain some continuity with the aesthetic and not yield to the lie that what we oppose is adventure and new interpretations.” I am no more opposed to newness, progress, or innovation than Eliot and Bloom were. What all three of us oppose is calling something “good” simply because lots of people seem to like it right away. What would be better than arguing at public meetings over library holdings and classroom readings: deciding for ourselves, taking our time to form an opinion based on deeper thinking, and celebrating what is perpetuated naturally by readers.

This has been on my mind since The National Council of Teachers of English published their report The State of Literature Use in Secondary English Classrooms back in July. (For those who aren’t NCTE members, a summary is offered in this blog post.) Looking over the results reminds me how appalling it is that students in Southern states read so little about the South. Including the best works from one’s own culture should be a foregone conclusion. Certainly, To Kill a Mockingbird makes the cut often. Looking farther out, we might see Up from Slavery, Beloved, As I Lay Dying, or The Watsons Go to Birmingham. But, considering the Common Core’s demands for such a large amount of nonfiction reading, those books – four of the five being fiction – are not enough.

So, here are six nonfiction books by writers from the South that, I believe, disallow that “a blind or timid adherence to [our] successes.” I hear these days that “we need to know our history.” Agreed. And I’ll add: Our culture, too. To understand the South requires more than a set of surface-level facts about slavery, the Civil War, and the Civil Rights movement, and for too many people, that’s all they’ve got in their intellectual toolbox. Dig a little deeper, friends.

Belonging by bell hooks

Published in 2009, this book’s subtitle is “A Culture of Place.” bell hooks, whose given name was Gloria Watkins, was an African American feminist writer, originally from rural Kentucky, whose ideas point to a better world that could be built upon understanding and compassion. Belonging was one of her later books, and it looks back on her relationship to her family and to her Kentucky roots. She discusses growing up in a place where she felt she didn’t completely belong, then when she left, she found that others didn’t fully accept her because of where she was from! Leaving the South for college then for various teaching jobs, bell hooks found anti-Southern prejudice and knew she had to come to terms with it as a Southerner.

Sex, Economy, Freedom & Community by Wendell Berry

Published in 1993, this book of eight essays is startlingly direct in offering Berry’s assessments of what we have let our culture become: materialistic in our values and unrealistic in our expectations. From the opening “Preface,” the Kentucky writer, poet, and farmer lays it out there that education has becoming something that people only care about for its economic potential and that unlimited “growth” is not possible with limited resources. His essays elaborate on and elucidate those views. This book came out right about the time that the internet was going mainstream, and Berry has a few things to say about its emergence, too.

The Long Haul by Myles Horton

Published in 1990, this autobiography tells the story of the Highlander Folk School’s founder. Horton was an educator and activist whose work had a heavy influence on the Civil Rights movement. In this book and in an earlier work titled Unearthing Seeds of Fire, he lays out the idea behind “folk schools” and shares his vision that education and organizing are best when they teach people to solve their own problems. His legacy is alive and well today, as Highlander is still operating in Tennessee.

Forty Acres and a Goat by Will D. Campbell

Published in 1986, this is a memoir by the infamous “bootleg preacher,” who by that time had also published two successful novels. Campbell became a figure in the Civil Rights movement in the mid-1950s when he served as a chaplain at the University of Mississippi and supported the movement despite pressure from white supremacists and segregationists. After that, as he put it, he worked as a “freelance civil rights activist.” What is perhaps best about this book is that its stories tell us, Certainly you know about that . . . but did you know about this?

The Omni-Americans by Albert Murray

Published in 1970, this book is one that I would call a cult classic. Murray was an Alabama native who attended Tuskegee Institute then became a well-known jazz and blues critic and essayist. The subject here is race, African Americans in particular, and Murray had a perspective that very few mainstream books offer. In a conversational style that presents a painstakingly nuanced argument, Murray picks apart common conceptions of black people and rails against the people who’ve created those images. His main target are what he calls the “social science types,” whose studies and reports have formed the basis of the idea that black people as a group are poor, degraded, and left behind. His perception, rooted in his upbringing in an all-black community north of Mobile, is that of a vibrant culture whose successes and beauty are too little recognized by a white culture that worked to create the negative circumstances that it decries.

Killers of the Dream by Lillian E. Smith

Published in 1949, this nonfiction work is not for the squeamish. To teach this book would take a special person and even to read it requires an uncommon degree of open-mindedness. Lillian Smith was a white writer and activist in the years before the Civil Rights movement, and this one followed her 1944 (fiction) novel Strange Fruit about an interracial love affair between a black man and a white woman in Georgia. That prior work earned her more than a little negative attention, but this one sealed the deal. One of her arguments in this book is that white women were among the main problems in the segregated Jim Crow South because they ceded so many of their roles to black women; these were white wives and mothers, Smith wrote, who had black women clean their houses, cook their family’s meals, raise their children, and even in some cases, satisfy their husbands. Smith’s rhetoric is strong, and her assessments cannot be taken lightly.

Other Recommendations:Confederates in the Attic by Tony Horwitz

September 1, 2025

A Quick Tribute to RL Burnside, Gone Twenty Years Now

With his house-rocking guitar style and his quizzical facial expressions, RL Burnside seemed like one of a kind. Though his early music and his locale place him squarely in the blues tradition, his music in later years transcended genre by allowing crossover and embracing modern styles, mostly through collaborations and remixes. The great hill country bluesman passed away twenty years ago today, on September 1, 2005.

I came late to RL Burnside’s music, finding it in the mid-2000s, around the time of his death. Not knowing anything about Burnside, I had bought the CD compilation from the 2004 Bonnaroo concert, and on it, guitarist Luther Dickinson plays a rip-it-up version of “Peekaboo” with Robert Randolph— which led me to wonder who he was. Luther Dickinson is the leader of North Mississippi All-Stars and the son of the late Jim Dickinson, a Memphis-based record producer. That, in turn, led me to find his collaborations with Burnside and with fife-and-drum legend Otha Turner. That new-to-me discovery then led to the purchase of the North Mississippi All-Stars’ Hill Country Revue album, also from the 2004 Bonnaroo, which had Burnside performing with the band.

Though I’ve never heard anyone claim that RL Burnside is not a bluesman, there is some argument over whether those latter-day albums are blues albums. The fall after that Bonnaroo show, critic John Clarke wrote this in an October 2004 review of A Bothered Mind in the British newspaper The Times:

The argument goes that Burnside was a respectable North Mississippi bluesman (listen to the simple vocal and guitar beauty of Bird without a Feather for evidence of this) who didn’t merely sell his soul to the Devil, but remortgaged it to a bunch of hip-hop performers and producers, including Kid Rock and Lyric Born. [ . . . ] Is it blues? I don’t think that it matters really. In a field that is also occupied by the likes of Little Axe and Moby, Burnside gets my vote as the most entertaining and authentic of them all.

A year later, Burnside’s September 2005 New York Times obituary called him a “Master of Raw Mississippi Blues.” It had this to say:

With a raw, unadorned electric guitar style and hypnotic one-chord songs, Mr. Burnside’s music was seen by critics as a link to the sound of Muddy Waters and Mississippi Fred McDowell. That might not have been a coincidence: Mr. Burnside, who was born in Harmontown, Miss., grew up near McDowell and learned to play guitar from him, and said that a cousin of his had married Muddy Waters.

But Mr. Burnside’s music had a rough, obstinate energy that also appealed to contemporary rock musicians and fans, and in the 1990’s, after decades of

obscurity, Mr. Burnside began to find wide success. In 1991, in his mid-60’s, he signed with Fat Possum, based in Oxford, Miss. One of his first albums for that label, “Too Bad Jim,” was produced by Robert Palmer, a former pop critic for The New York Times.

RL Burnside was 78 years old at the time of his death. His discography can be found here.

August 28, 2025

Dirty Boots: Parking a Bicycle Straight

I was well into my teaching career before I ever heard the term “working-class academic.” If I remember correctly, it was in 2009 at a rhetoric-composition conference in Minneapolis, where I was speaking on a panel about community writing. Anyone who has been to these conferences knows that, when you’re not speaking, you go listen to other panels. It was at one of those where I heard the term. As I read more about this idea, it became clear to me that a working-class academic is basically what I am.

A working-class academic is just what it sounds like it is: a person who was raised in a blue-collar family, among blue-collar people and with blue-collar values, but who then sought a career in academia, which is a distinctly non-blue collar field. This decision often puts a person at odds with the community that raised him. As one article in the journal College Composition and Communication put it, working-class academics feel “dual estrangement and internalized class conflict,” a side effect of leaving one culture to live in another. Because of the nature of our work, the people from our upbringing – parents, siblings, former neighbors, old friends – often don’t understand, appreciate, or even approve of what we do or who we become.

A working-class academic is just what it sounds like it is: a person who was raised in a blue-collar family, among blue-collar people and with blue-collar values, but who then sought a career in academia, which is a distinctly non-blue collar field. This decision often puts a person at odds with the community that raised him. As one article in the journal College Composition and Communication put it, working-class academics feel “dual estrangement and internalized class conflict,” a side effect of leaving one culture to live in another. Because of the nature of our work, the people from our upbringing – parents, siblings, former neighbors, old friends – often don’t understand, appreciate, or even approve of what we do or who we become.

Yet, despite this “estrangement,” my work as a teacher of English and writing is informed by my experience. When I talk to students about how grammar is a system, I use the human body and machinery as metaphors, and when I explain why following grammar rules is important, I relate it to traffic and sports. In sharing my belief that “writing is a tool for thinking,” as the NCTE puts it, I ask, Would you dig a hole, then go get a shovel? No. Then why would you think that you couldn’t start writing until you have everything figured out? Use the tools that are made for the job! A common question among working people – students and their parents – is: what good will this do me? Teachers have to be able to answer that question. My answer is: thinking clearly and communicating well are valuable in life, no matter what job you do. When ideas about writing are put into the context of everyday life, then what we do in an English class can be understood as useful skills.

The real-world value in academics is not always readily apparent, though, and some aspects of our culture reinforce the worst stereotypes. In a now-infamous set of remarks, the late Alabama governor George Wallace once called academics “pointy-headed intellectuals” who couldn’t figure out “how to park a bicycle straight.” Wallace’s political career was built upon his image as a champion of the working man, and to treat academics in this way was meant to affirm the working class’s negative bias against the teachers and professors whose assignments seemed useless in school. Creating an us-versus-them paradigm, Wallace wanted to contrast people with “common sense” against people with “book learning,” implying that a person can’t have both. This pandering to the lowest common denominator won him many votes, but it also pushed many Alabamians away from learning about things that could have actually improved their lives, like how politicians use rhetoric to influence people and how regressive tax structures hurt the poorest people. I’ve learned about these things by engaging, rather than shunning, intellectual pursuits and by combining “book learning” with real-world experiences from my working-class upbringing.

Today, I hear the Wallace-like prattling about us-versus-them, but this time it comes in the form of “college makes people liberal.” After Wallace’s heyday, the late-twentieth century saw remedies to severe poverty in the South, and many Southerners also found greater affluence and material comfort in cities and towns, just about the time that the suburban politics of the post-Civil Rights era were forming. Which led far too many people to a new kind of binary thinking: you’re either a conservative Republican with good sense or you’re a liberal Democrat who doesn’t “get it.” Combine the anti-intellectual sentiments of the past with anti-liberal sentiments of the present, and voila! Today, if a “good family” with conservative values sends a teenager to college, and that teenager comes home with new ideas— Oh no, those professors are not going to turn my kid liberal! But that’s not what’s actually happening.

As a working-class academic, I have seen this change from the inside, experienced it personally. Earning an English degree in the 1990s and a masters degree in the 2000s has broadened my horizons in ways that my parents never would have, would never have tried to, and didn’t embrace, and those changes in me led to differences of opinion among us. No one turned me liberal. What my professors did was show me ways of living and thinking that my upbringing never offered – and never would have – which led me to understand that ways of living and thinking unlike my own could be just as valid as my own. My education also helped me to understand that social issues, political leanings, and life choices are not as cut-and-dried as they might seem. Personally, I don’t think that’s so much “liberal” as it is American. That is, if we truly mean what we say about hard work, opportunity, and freedom.

The CCC article referenced above is: Borkowski, David. “‘Not Too Late to Take the Sanitation Test’: Notes of a Non-Gifted Academic from the Working Class.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 56, no. 1, 2004, pp. 94–123. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/4140682.

August 21, 2025

Watching: “A Warehouse on Tchoupitoulas” (2013)

The 2013 documentary A Warehouse on Tchoupitoulas offers 75-minute glimpse into the New Orleans music venue called simply The Warehouse. After a couple of minutes of background info from the guys who converted an old warehouse into a concert hall, the discussion turns to opening night in 1970, which featured the Peter Green incarnation of Fleetwood Mac and The Grateful Dead. As a bit of rock n’ roll lore, it was that opening weekend that yielded the lines about being busted in New Orleans in the Dead’s song “Truckin’.” What follows are a bunch of stories about Jim Morrison’s last show in the US, Bob Marley in his prime, going deep see fishing with Foghat, and whole weekends with the Allman Brothers.

The Warehouse hosted a huge slate of bands over the years, many recognizable while some clearly came and went. To view the full list of shows held at The Warehouse throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, look on the website blackstrat.com. There are also images and more.

About the film itself, the subject matter is really interesting, but what is on-screen lacks energy. Viewers are told in the opening moments that, due to legal issues, the music and footage of the actual shows won’t be included. That leaves a plethora of still images and a bunch of interviews with older people who are waxing nostalgic about things they did and saw thirty to forty years earlier. While it’s easy to tell that what they experienced was probably really cool, what a viewer gets is just individual ones of them talking about it . . . which isn’t nearly as cool. But to document that place at that time, it’s what we have. (The warehouse-turned-venue has even been torn down now.)

Below is a link to the full documentary, which is available on YouTube.

August 12, 2025

Dirty Boots: Community and Politics

It’s hard to tell these days whether to believe that we’re “more divided than ever” or that we’re “not as divided as we think we are.” One thing is for sure, though: no easy solutions are popping up. Of the people around me in my daily life, most seem to have an opinion about this. Frankly, I can tell that most of that most are either guessing or just repeating what they hear everyone else say. I don’t think any of us really know.

What got me thinking about this was an article in Commonweal last spring titled “Where Politics is Still Possible.” When I saw it, I thought, Still possible? In a democracy, politics has to be possible! Reading beyond the title – an uncommon act in itself – I found writer Jonathon Malesic focusing on students at several smaller US colleges and universities whose civics courses are steeped in real-world scenarios. Acknowledging the ups and downs, we read that many of the students he met were apathetic about politics, yet the demographics of these smaller schools often included more non-traditional students, which broadened the experience for everyone. So, were the students divided? Not exactly. Malesic writes, “Over and over, students told me that their policy views do not line up with either of the major political parties. This does not mean they are all centrists, just that their leanings are often complex.” He seems to point to the same conclusion that I have come to: we’re not so much divided as scattered. And while some Americans decry college as useless or rattle sabers about brainwashing, his article reminds us of this: “College is not the only place people can learn democratic participation; labor unions and civic organizations are such places, too. But college offers a rare combination of factual knowledge, skill-building, and pluralism that can form highly engaged citizen-leaders.”

Educating ourselves can help to clear a path out of this frustration. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle believed that politics is a “practical science [ . . . ] since it is concerned with the noble action or happiness of the citizens.” The adjective practical comes from the word practice, which in English is both a noun and a verb. In either form, it implies a hands-on kind of utility that is in-action. The practice of politics cannot occur among people who are passive, neglectful, or ignorant, because none of those traits can lead to “noble action” or to the “happiness of the citizens.” Calling it a science implies a foundation in empirical reality and a willingness to accept new, previously undiscovered facts within the process of improving our knowledge, and thus improving our lives. Politics, at its best, should welcome new knowledge through active participation in a hands-on process. That is how things can get better.

Educating ourselves can help to clear a path out of this frustration. The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle believed that politics is a “practical science [ . . . ] since it is concerned with the noble action or happiness of the citizens.” The adjective practical comes from the word practice, which in English is both a noun and a verb. In either form, it implies a hands-on kind of utility that is in-action. The practice of politics cannot occur among people who are passive, neglectful, or ignorant, because none of those traits can lead to “noble action” or to the “happiness of the citizens.” Calling it a science implies a foundation in empirical reality and a willingness to accept new, previously undiscovered facts within the process of improving our knowledge, and thus improving our lives. Politics, at its best, should welcome new knowledge through active participation in a hands-on process. That is how things can get better.

And even though we have no shortage of people wanting to get radical, one of the worst ideas that we can entertain is to throw out everything and start fresh. If we go back to the colonial days, the United States has more than three centuries of tradition, wisdom, precedent, and lived experience to work with. Some of it is ugly, painful, and shameful. Much of it is useful. The questions now are not “should it have happened?” or “who is to blame?” but “what can we learn from it?” One of my favorite writers, Alabama native Albert Murray, put it this way, speaking to students at Howard University in 1978:

But the primary concern of revolution is not destruction but the creation of better procedures and institutions. All too often being a rebel means only that you’re against something. Whereas being a revolutionary should mean that you are against something because you are for something better. Indeed, primarily because you are for something better. [ . . . ] You reject that which is unproductive or counterproductive. But you don’t reduce everything to rejection and rebellion, because the whole idea of life, which is to say the process of living and continuing to exist, is affirmation. The whole idea of education is to find the terms and meanings that make fruitful continuity possible.

“The whole idea of” politics might also be “to find the terms and meanings that make fruitful continuity possible.” This modern problem of whether politics is still possible has a much better chance of being resolved when people and communities are less interested in what they are against and more interested in what they are for. The question, riffing off of Murray, could be: what are we trying to affirm?

Thinking about what I’m for, several things come to mind. I’m for finding solutions with each other, for real and in-person, not through governments and politicians. I’m for helping people see that the interests of the powerful are not actually the interests of all people. I’m for organizing ourselves in ways and in groups that don’t include a political party. I’m for recognizing the limitations and the dangers of social media and other “online communities.” Related to that, I’m also for establishing rules making social media companies, email providers, and other web-based businesses require legal and verifiable forms of identity to have an account, in the same way that banks, courts, schools, and utilities do. Community and politics are both built upon trust, and trust can’t be built upon political agendas and false identities. Changes like that could reduce the cognitive dissonance that leads to distrust. Which, if we truly are divided, is the real problem at the root of it all.