Michael Greger's Blog

February 3, 2026

Keeping Better Score of Your Diet

How can you get a perfect diet score?

How do you rate the quality of people’s diets? Well, “what could be more nutrient-dense than a vegetarian diet?” Indeed, if you compare the quality of vegetarian diets with non-vegetarian diets, the more plant-based diets do tend to win out, and the higher diet quality in vegetarian diets may help explain greater improvements in health outcomes. However, vegetarians appear to have a higher intake of refined grains, eating more foods like white rice and white bread that have been stripped of much of their nutrition. So, just because you’re eating a vegetarian diet doesn’t mean you’re necessarily eating as healthfully as possible.

Those familiar with the science know the primary health importance of eating whole plant foods. So, how about a scoring system that simply adds up how many cups of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, beans, chickpeas, split peas, and lentils, and how many ounces of nuts and seeds per 1,000 calories (with or without counting white potatoes)? Looking only at the total intake of whole plant foods doesn’t mean you aren’t also stuffing donuts into your mouth. So, you could imagine proportional intake measures, based on calories or weight, to determine the proportion of your diet that’s whole plant foods. In that case, you’d get docked points if you eat things like animal-derived foods—meat, dairy, or eggs—or added sugars and fats.

My favorite proportional intake measure is McCarty’s “phytochemical index,” which I’ve profiled previously. I love it because of its sheer simplicity, “defined as the percent of dietary calories derived from foods rich in phytochemicals.” It assigns a score from 0 to 100, based on the percentage of your calories that are derived from foods rich in phytochemicals, which are biologically active substances naturally found in plants that may be contributing to many of the health benefits obtained from eating whole plant foods. “Monitoring phytochemical intake in the clinical setting could have great utility” in helping people optimize their diet for optimal health and disease prevention. However, quantifying phytochemicals in foods or tissue samples is impractical, laborious, and expensive. But this concept of a phytochemical index score could be a simple alternative method to monitor phytochemical intake.

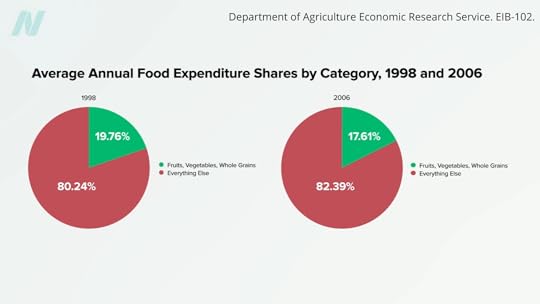

Theoretically, a whole food, plant-based or vegan diet that excluded refined grains, white potatoes, hard liquors, added oils, and added sugars could achieve a perfect score of 100. Lamentably, most Americans’ diets today might be lucky to score just 20. What’s going on? In 1998, our shopping baskets were filled with about 20% whole plant foods; more recently, that has actually shrunk, as you can see below and at 2:49 in my video Plant-Based Eating Score Put to the Test.

Wouldn’t it be interesting if researchers used this phytochemical index to try to correlate it with health outcomes? That’s exactly what they did. We know that studies have demonstrated that vegetarian diets have a protective association with weight and body mass index. For instance, a meta-analysis of five dozen studies has shown that vegetarians had significantly lower weight and BMI compared with non-vegetarians. And even more studies show that high intakes of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes may be protective regardless of meat consumption. So, researchers wanted to use an index that gave points for whole plant foods. They used the phytochemical index and, as you may recall from an earlier video, tracked people’s weight over a few years, using a scale of 0 to 100 to simply reflect what percentage of a person’s diet is whole plant foods. And even though the healthiest-eating tier only averaged a score of about 40, which meant the bulk of their diet was still made up of processed foods and animal products, just making whole plant foods a substantial portion of the diet may help prevent weight gain and decrease body fat. So, it’s not all or nothing. Any steps we can take to increase our whole plant food intake may be beneficial.

Many more studies have since been performed, with most pointing in the same direction for a variety of health outcomes—indicating, for instance, higher healthy plant intake is associated with about a third of the odds of abdominal obesity and significantly lower odds of high triglycerides. So, the index may be “a useful dietary target for weight loss,” where there is less focus on calorie intake and more on increasing consumption of these high-nutrient, lower-calorie foods over time. Other studies also suggest the same is true for childhood obesity.

Even at the same weight, with the same amount of belly fat, those eating plant-based diets tend to have higher insulin sensitivity, meaning the insulin they make works better in their body, perhaps thanks to the compounds in plants that alleviate inflammation and quench free radicals. Indeed, the odds of hyperinsulinemia—an indicator of insulin resistance—were progressively lower with greater plant consumption. No wonder researchers found 91% lower odds of prediabetes for people getting more than half their calories from healthy plant foods.

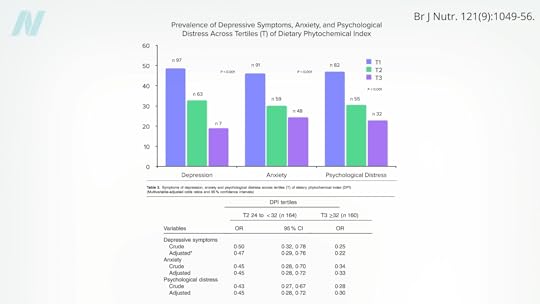

They also found significantly lower odds of metabolic syndrome and high blood pressure. There were only about half the odds of being diagnosed with hypertension over a three-year period among those eating more healthy plants. Even mental health may be impacted—about 80% less depression, 2/3 less anxiety, and 70% less psychological distress, as you can see below and at 5:15 in my video.

Is there a link between the dietary phytochemical index and benign breast diseases, such as fibrocystic diseases, fatty necrosis, ductal ectasia, and all sorts of benign tumors? Yes—70% lower odds were observed in those with the highest scores. But what about breast cancer? A higher intake of healthy plant foods was indeed associated with a lower risk of breast cancer, even after controlling for a long list of other factors. And not just by a little bit. Eating twice the proportion of plants compared to the standard American diet was linked to more than 90% lower odds of breast cancer.

Doctor’s Note

You can learn more about the phytochemical index in Calculate Your Healthy Eating Score.

If you’re worried about protein, check out Flashback Friday: Do Vegetarians Get Enough Protein?

It doesn’t have to be all or nothing, though. Do Flexitarians Live Longer?

For more on plant-based junk, check out Friday Favorites: Is Vegan Food Always Healthy?.

January 29, 2026

How Low Can LDL Cholesterol Go on PCSK9 Inhibitors?

People with genetic mutations that leave them with an LDL cholesterol of 30 mg/dL live exceptionally long lives. Can we duplicate that effect with drugs?

Data extrapolated from large cholesterol-lowering trials using statin drugs suggest that the incidence of cardiovascular events like heart attacks would approach zero if LDL cholesterol could be forced down below 60 mg/dL for first-time prevention and around 30 mg/dL for those trying to prevent another one. But is lower actually better? And is it even safe to have LDL cholesterol levels that low?

We didn’t know until PCSK9 inhibitors were invented. Are PCSK9 Inhibitors for LDL Cholesterol Safe and Effective? I explore that issue in my video of the same name. PCSK9 is a gene that mutated to give people such low LDL cholesterol, and that’s how Big Pharma thought of trying to cripple PCSK9 with drugs. After a heart attack, intensive lowering of an individual’s LDL cholesterol beyond a target of 70 mg/dL does seem to work better than more moderate lowering. There were fewer cardiovascular deaths, heart attacks, or strokes at an LDL less than 30 mg/dL compared with 70 mg/dL or higher, and even compared to less than 70 mg/dL. There is a consistent risk reduction even when starting as low as an average of 63 mg/dL, and pushing LDL down to 21 mg/dL, remarkably, showed “no observed offsetting” of adverse side effects.

Maybe that shouldn’t be so surprising, since that’s about the level at which we start life. And there’s another type of genetic mutation that leaves people with LDL levels of about 30 mg/dL their whole lives, and they are known to have an exceptionally long life expectancy. So, where did we get this idea that cholesterol could fall too low?

The common claim that lowering cholesterol can be dangerous due to depletion of cell cholesterol is unsupported by evidence and does not consider the exquisite balancing mechanisms our body uses. After all, that’s how we evolved. Until recently, most of us used to have LDL levels around 50 mg/dL, so that’s pretty normal for the human species. The absence of evidence that low or lowered cholesterol levels are somehow bad for us contrasts with the overwhelming evidence that cholesterol reduction decreases risk for coronary artery disease, our number one killer.

What about hormone production, though? Since the body needs cholesterol for the synthesis of steroid hormones—like adrenal hormones and sex hormones—there’s a concern that there wouldn’t be enough. You don’t know, though, until you put it to the test. For decades, we’ve known that women on cholesterol-lowering drugs don’t have a problem with estrogen production and that lowering cholesterol doesn’t affect adrenal gland function. As well, it doesn’t impair testicular function in terms of causing testosterone levels to fall below normal. If anything, statin drugs can improve erectile function in men, which is what you’d expect from lowering cholesterol. But you’ll notice these studies only looked at lowering LDL to 70 mg/dL or below. What about really low LDL?

On PCSK9 inhibitors, you can get most people under an LDL of 40 mg/dL and some under 15 mg/dL! And there is no evidence that adrenal, ovarian, or testicular hormone production is impaired, even in patients with LDL levels below 15 mg/dL. The risk of heart attacks falls in a straight line as LDL gets lower and lower, even below 10 mg/dL, for example, without apparent safety concerns, but that’s over the duration of exposure to these drugs. The longest follow-up to date of those whose LDL, by way of using multiple medications, was kept less than 30 mg/dL is six years.

Now, we can take comfort in the fact that those with extreme PCSK9 mutations, leading to a lifelong reduction in levels of LDL to under 20 mg/dL their whole lives, remain healthy and have healthy kids. Cholesterol-affecting mutations are what cause the so-called “longevity syndromes,” but that doesn’t necessarily mean the drugs are safe. The bottom line is we should try to get our LDL cholesterol down as low as we can, but much longer follow-up data are necessary anytime a new class of drugs is introduced. So far, so good, but we’ve only been following the data for about 10 years. For example, we didn’t know statins increased diabetes risk until decades after they were approved and millions had been exposed. Also worth noting: PCSK9 inhibitors cost about $14,000 a year.

Doctor’s Note

How can we decrease cholesterol with diet? See Trans Fat, Saturated Fat, and Cholesterol: Tolerable Upper Intake of Zero.

For more on statin drugs, see the related posts below.

January 27, 2026

How to Beat Heart Disease Before It Starts

Why might healthy lifestyle choices wipe out 90% of our risk for having a heart attack, while drugs may only reduce risk by 20% to 30%?

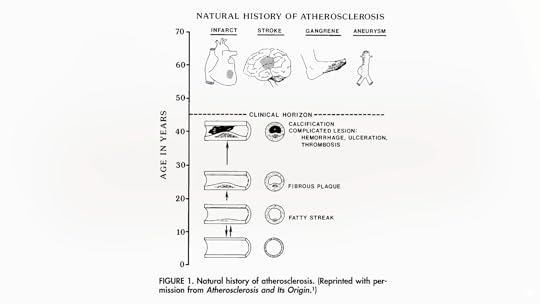

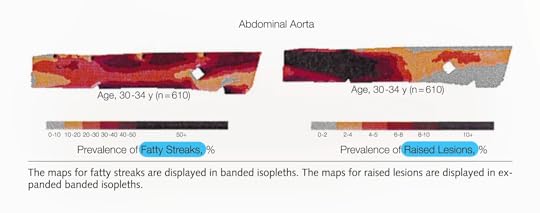

On the standard American diet, atherosclerosis—hardening of the arteries, the number one killer of men and women—has been found to start in our teens. Investigators collected about 3,000 sets of coronary arteries and aortas (the aorta is the main artery in the body) from victims of accidents, homicides, and suicides who were 15 to 34 years old and found that the fatty streaks in arteries can begin forming in our teens, which turn into atherosclerotic plaques in our 20s that get worse in our 30s and can then become deadly. In the heart, atherosclerosis can cause a heart attack. In the brain, it can cause a stroke. See the progression below and at 0:35 in my video Can Cholesterol Get Too Low?.

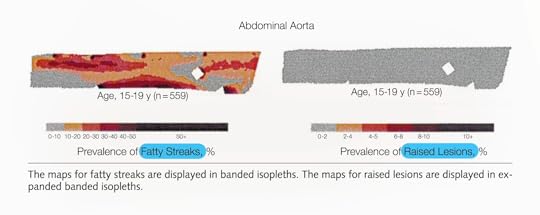

How common is this? All of the teens they looked at—100% of them—already had fatty streaks building up inside their arteries. By their early 30s, most already had those streaks blossoming into atherosclerotic plaques that bulged into their arteries. From ages 15 through 19, their aortas had fatty streaks building up throughout them, but no plaques yet, on average, as seen below and at 1:15 in my video.

The plaques started appearing in their abdominal aorta in their early 20s and worsened by their late 20s, by which time fatty streaks had infiltrated throughout. By their early 30s, their arteries were in bad shape, as seen below and at 1:25 in my video.

But that’s just the abdominal aorta, the main artery running through the torso that splits off into our legs. What about the coronary arteries that feed the heart?

Researchers found the same pattern: fatty streaks in teens, early signs of plaque in early 20s that progress with age, and by the early 30s, most people already had plaques in their coronary arteries, as seen below and at 1:47 in my video.

Atherosclerosis starts as early as adolescence.

That’s why we shouldn’t wait until heart disease becomes symptomatic to treat it. If it starts in our youth, we should start treating it when we’re youths. If you knew you had a cancerous tumor, you wouldn’t want to wait until it grew to a certain size to treat it. If you had diabetes, you wouldn’t want to wait until you started going blind before you did something about it. So, how do you treat atherosclerosis? You lower LDL cholesterol through a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol—a diet that’s low in eggs, meat, dairy, and junk.

If we want to stop this epidemic, we have to “alter our lifestyle accordingly, beginning in infancy or early childhood. Is such a radical proposal totally impractical?” (Eating more healthfully? Radical?!) It would take serious dedication to change our behavior, but atherosclerosis is our number one cause of death. In the case of cigarettes, we did pretty well, slashing smoking rates and dropping lung cancer rates. And, yes, healthy eating is safe. According to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the largest and oldest association of nutrition professionals in the world, even strictly plant-based diets are appropriate for all stages of life, starting from pregnancy. (NutritionFacts.org is among the websites recommended by the Academy for more information.)

The title of an important study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology declares: “Curing Atherosclerosis Should Be the Next Major Cardiovascular Prevention Goal.” What evidence do we have that a lifelong suppression of LDL will do it? There is a genetic mutation of a gene called PCSK9 that about 1 in 50 African Americans are lucky to be born with because it gives them about a 40% lower LDL cholesterol level their whole lives. Indeed, they were found to have dramatically lower rates of coronary heart disease—an 88% drop in risk compared to those without the genetic mutation, despite otherwise terrible cardiovascular risk factors on average. Most had high blood pressure and were overweight, almost a third smoked, and nearly 20% had diabetes, but that highlights how a lifelong history of low LDL cholesterol levels can substantially reduce the risk of coronary heart disease, even when there are multiple risk factors.

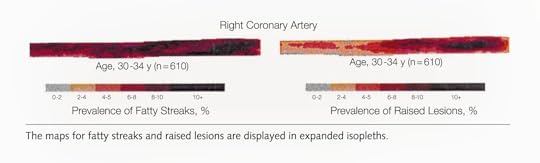

This near-90% drop in events like heart attacks or sudden death occurred at an average LDL level of 100 mg/dL, compared to 138 mg/dL in those without the genetic mutation. This means LDL can drop below even 100 mg/dL. Why does a drop in LDL cholesterol by about 40 mg/dL from a lucky genetic mutation lower the risk of coronary heart disease by nearly 90%, while the same reduction with statin drugs lowers it by only about 20%? The most probable explanation? Duration. When it comes to lowering LDL cholesterol, it’s not only about how low it is, but how long it’s been low.

That’s why healthy lifestyle choices may wipe out about 90% of our risk for having a heart attack, while drugs may reduce it by only 20% to 30%. If you’re getting treated with drugs later in life, you may have to get your LDL under 70 mg/dL to halt the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. But if we start making healthier choices earlier, it may be enough to lower LDL cholesterol just to 100 mg/dL, which should be achievable for most of us. That’s consistent with country-by-country data that suggested death from heart disease would bottom out at a population average of about 100 mg/dL, as seen below and at 5:21 in my video.

But that’s only if you can keep your LDL cholesterol down your whole life.

If you’re relying on medication later in life to halt disease progression, you may need to get your LDL below 70 mg/dL, and if you’re trying to use drugs to reverse a lifetime of bad food choices, you may not get to zero coronary heart disease events until your LDL drops to about 55 mg/dL. If your heart disease is so bad that you’ve already had a heart attack but you’re trying not to die from another one, ideally, you might want to push your LDL down to about 30 mg/dL. Once you get that low, not only would you likely prevent any new atherosclerotic plaques, but you’d also help stabilize the plaques you already have so they’re less likely to burst open and kill you.

Is it even safe to have cholesterol levels that low, though? In other words, can LDL cholesterol ever be too low? We’ll find out next.

Doctor’s Note

Didn’t know atherosclerosis could start at such a young age? See Heart Disease Starts in Childhood.

For more on drugs versus lifestyle, check out my video The Actual Benefit of Diet vs. Drugs.

Want to learn more about so-called primordial prevention? See When Low Risk Means High Risk.

Does Cholesterol Size Matter? Watch the video to find out.

January 22, 2026

Is Fasting an Effective Treatment for Diabetes?

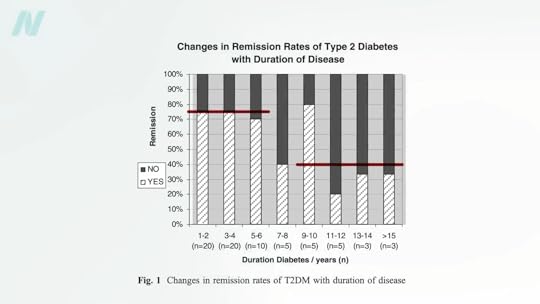

By losing 15% of their body weight, nearly 90% of those who have had type 2 diabetes for less than four years may achieve remission.

Currently, more than half a billion adults have diabetes, and about a 50% increase is expected in another generation. I’ve got tons of videos on the best diets for diabetes, but what about no diet at all?

More than a century ago, fasting was said to cure diabetes, quickly halting its progression and eliminating all signs of the disease within days or weeks. Even so, starvation is guaranteed to lead to the complete disappearance of you if kept up long enough. What’s the point of fasting away the pounds if they’re just going to return as soon as you restart the diet that created them in the first place? Might it be useful to kickstart a healthier diet? Let’s see what the science says.

Type 2 diabetes has long been recognized as a disease of excess, once thought to afflict only “the idle rich…anyone whose environment and self-support does not require of him some sustained vigorous bodily exertion every day, and whose earnings or income permit him, and whose inclination tempts him, to eat regularly more than he needs.” Diabetes is preventable, so might it also be treatable? If we’re dying from overeating, maybe we can be saved by undereating. Remarkably, this idea was proposed about 2,000 years ago in an Ayurvedic text:

“Poor diabetic people’s medicine

He should live like a saint (Munni);

He should walk for 800–900 miles.

Or he shall dig a pond;

Or he shall live only on cow dung and cow urine.”

That reminds me of the Rollo diet for diabetes proposed in 1797, which was composed of rancid meat. That was on top of the ipecac-like drugs he used to induce severe sickness and vomiting. Anything that makes people sick has only “a temporary effect in relieving diabetes” because it reduces the amount of food eaten. His diet plan—which included congealed blood for lunch and spoiled meat for dinner—certainly had that effect.

Similar benefits were seen in people with diabetes during the siege of Paris in the Franco‐Prussian War, leading to the advice to mangez le moins possible, which translates to “eat as little as possible.” This was formalized into the Allen starvation treatment, considered to be “the greatest advance in the treatment of diabetes prior to the discovery of insulin.” Before insulin, there was “The Allen Era.”

Dr. Allen noted that there are clinical reports of even severe diabetes cases clearing up after the onset of a “wasting condition” like tuberculosis or cancer, so he decided to put it to the test. He found that even in the most severe type of diabetes, he could clear sugar from people’s urine within ten days. Of course, that’s the easy part; it’s harder to maintain once they start eating again. To manage patients’ diabetes, he stuck to two principles: Keep them underweight and restrict the fat in their diet. A person with severe diabetes can be symptom-free for days or weeks, but eating butter or olive oil can make the disease come raging back.

As I’ve said before, diabetes is a disease of fat toxicity. Infuse fat into people’s veins through an IV, and, by using a high-tech type of MRI scanner, you can show in real time the buildup of fat in muscle cells within hours, accompanied by an increase in insulin resistance. The same thing happens when you put people on a high-fat diet for three days. It can even happen in just one day. Even a single meal can increase insulin resistance within six hours. Acute dietary fat intake rapidly increases insulin resistance. Why do we care? Insulin resistance in our muscles, in the context of too many calories, can lead to a buildup of liver fat, followed by fat accumulation in the pancreas, and eventually full-blown diabetes. “Type 2 diabetes can now be understood as a state of excess fat in the liver and pancreas, and remains reversible for at least 10 years in most individuals.”

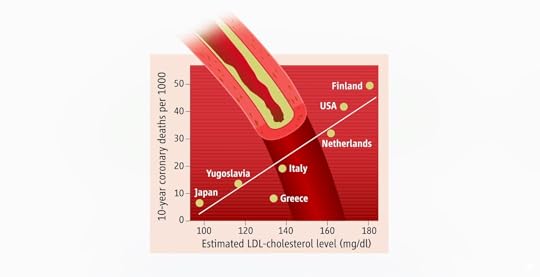

When people are put on a very low-calorie diet—700 calories a day—fat can get pulled out of their muscle cells, accompanied by a corresponding boost in insulin sensitivity, as shown below and at 4:43 in my video Fasting to Reverse Diabetes.

The fat buildup in the liver has then been shown to decrease substantially, and if the diet is continued, the excess fat in the pancreas also reduces. If caught early enough, reversing type 2 diabetes is possible, which would mean sustained healthy blood sugar levels on a healthy diet.

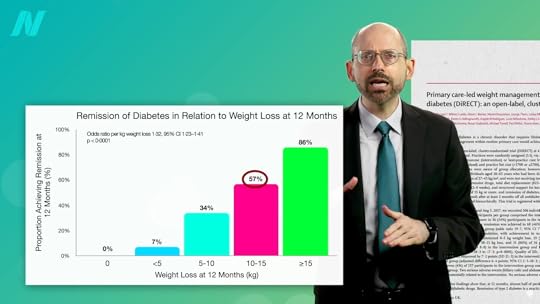

With the loss of 15% of body weight, nearly 90% of individuals who have had type 2 diabetes for less than four years can achieve non-diabetic blood sugar levels, whereas it may only be reversible in 50% of those who’ve lived with the disease for longer than eight years. That’s better than bariatric surgery, where those losing even more weight had lower remission rates of 62% and 26%, respectively. Your forks are better than surgeons’ knives. Indeed, most people who have had their type 2 diabetes diagnosis for an average of three years can reverse their disease after losing about 30 pounds, as you can see below and at 5:37 in my video.

Of course, an extended bout of physician-supervised, water-only fasting could also get you there, but you would have to maintain that weight loss. One of the things that has been said with “certainty” is that if you regain the weight, you regain your diabetes.

To bring it full circle, “the initial euphoria about ‘medicine’s greatest miracle’”—the discovery of insulin in 1921—“soon gave way to the realisation” that, while it was literally life-saving for people with type 1 diabetes, insulin alone wasn’t enough to prevent such complications as blindness, kidney failure, stroke, and amputations in people with type 2 diabetes. That’s why one of the most renowned pioneers in diabetes care, Elliott Joslin, “argued that self-discipline on diet and exercise, as it was in the days prior to the availability of the drug [insulin], should be central to the management of diabetes….”

Doctor’s Note

Check out Diabetes as a Disease of Fat Toxicity for more on the underlying cause of the disease.

For more on fasting for disease reversal, see:

Friday Favorites: Fasting to Treat Depression Friday Favorites: Fasting for Irritable Bowel Syndrome Fasting for Post-Traumatic Brain Injury HeadacheFasting is not the best way to lose weight. To learn more, see related posts below.

What is the best way to lose weight? See Friday Favorites: The Best Diet for Weight Loss and Disease Prevention.

January 20, 2026

All About Allulose

Sugar and high fructose corn syrup are the original industrial sweeteners—inexpensive, filled with empty calories, and contributing to diseases such as obesity, type 2 diabetes, cavities, and metabolic syndrome. Artificial sweeteners, like NutraSweet, Splenda, and Sweet’N Low, are the second-generation sweeteners. They are practically calorie-free, but cautions have been raised about their adverse effects. Sugar alcohols, such as sorbitol, xylitol, and erythritol, are the third-generation sweeteners. They’re low in calories but carry laxative effects or even worse. What about rare sugars like allulose?

What Is Allulose?

Allulose is a natural, so-called rare sugar, present in limited quantities in nature. “Recent technological advances, such as enzymatic engineering using genetically modified microorganisms, now allow [manufacturers] to produce otherwise rare sugars” like allulose in substantial quantities.

Allulose and Weight Loss

What happened when researchers evaluated the effect of allulose on fat mass reduction in people? As I discuss in my video Is Allulose a Healthy Sweetener?, more than a hundred individuals were randomized to a placebo control (0.012 grams of sucralose twice a day), a teaspoon (4 g) of allulose twice a day, or 1¾ teaspoons (7 g) of allulose twice a day for 12 weeks. Despite no changes in physical activity or calorie consumption in the groups, body fat significantly decreased following allulose supplementation. There weren’t any significant changes in LDL cholesterol levels in either of the allulose groups, though.

What about the purported anti-diabetes effects?

Does Allulose Help with Diabetes?

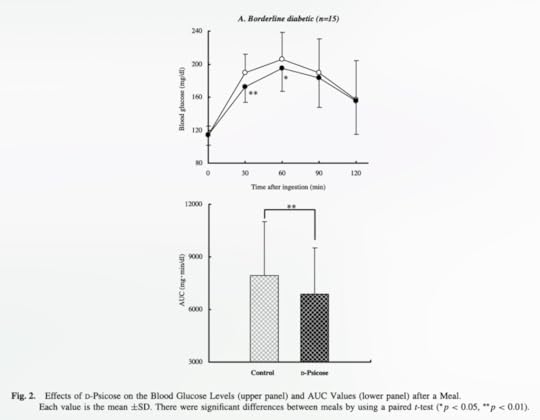

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover experiment, people with borderline diabetes consumed a cup of tea containing either 1¼ teaspoons (5 g) of allulose or no allulose (control) with a meal. There was a significant reduction in blood sugar levels 30 and 60 minutes after consumption, but it was only about 15% lower compared to the control group and didn’t last beyond the first hour. To test long-term safety, the same researchers then randomized healthy people to a little over a teaspoon (5 g) of allulose three times a day with meals for 12 weeks. There didn’t appear to be any adverse side effects, but there weren’t any effects on weight or blood sugar levels either. So, it turns out the body fat data are mixed, as are the sugar data.

Another study found no effects of allulose on blood sugar levels in healthy participants tested up to two hours after consumption, though a similar study on individuals with diabetes did. And a systematic review and meta-analysis of all such controlled feeding trials suggested that the acute benefit on blood sugars was of “borderline significance.” It’s unclear whether this small and apparently inconsistent effect could translate into meaningful improvements in long-term blood sugar control. It may not be enough just to add allulose—you might also have to cut out junk food.

Is Allulose Good or Bad for You?

As I discuss in my video Does the Sweetener Allulose Have Side Effects?, unlike table sugar, allulose is safe for our teeth; it apparently isn’t metabolized by cavity-causing bacteria to produce acid and promote plaque buildup. It doesn’t raise blood sugar levels either, even in people with diabetes. Allulose is considered a “relatively nontoxic” sugar, but what does that mean?

How Much Allulose Is Too Much?

In one study, researchers gave healthy adults beverages containing gradually higher doses of allulose “to identify the maximum single dose for occasional ingestion.” No cases of severe gastrointestinal symptoms were noted until a dose of 0.4 g per kg of bodyweight was reached, which is about eight teaspoons for the average American. Severe symptoms of diarrhea were noted at a dose of 0.5 g per kg of bodyweight, or about ten teaspoons.

In terms of a daily upper limit given in smaller doses throughout the day, once participants reached around 17 teaspoons (1.0 g/kg bodyweight) a day, depending on weight, some experienced severe nausea, abdominal pain, headache, or diarrhea. So, most adults in the United States should probably stay under single doses of about 8 teaspoons (0.4 g per kg of bodyweight) and not exceed about 18 teaspoons (0.9 g per kg of bodyweight) for the whole day.

So, What’s the Verdict on Allulose?

Are rare sugars like allulose a healthy alternative for traditional sweeteners? Well, considering the variety of potentially beneficial effects of allulose “without known disadvantages from metabolic and toxicological studies, allulose may currently be the most promising rare sugar.” But how much is that saying? We just don’t have a lot of good human data. “As a result of the absence of these studies, it may be too early to recommend rare sugars for human consumption.” This is especially true given the erythritol debacle.

January 15, 2026

Can Olive Oil Compete with Arthritis Drugs?

What happened when topical olive oil was pitted against an ibuprofen-type drug for osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis?

Fifty million Americans suffer from arthritis, and osteoarthritis of the knee is the most common form, making it a leading cause of disability. There are several inflammatory pathways that underlie the disease’s onset and progression, so various anti-inflammatory foods have been put to the test. Strawberries can decrease circulating blood levels of an inflammatory mediator known as tumor necrosis factor, but that doesn’t necessarily translate into clinical improvement. For example, drinking cherry juice may lower a marker of inflammation known as C-reactive protein, but it failed to help treat pain and other symptoms of knee osteoarthritis. However, researchers claimed it “provided symptom relief.” Yes, it did when comparing symptoms before and after six weeks of drinking cherry juice, but not any better than a placebo, meaning drinking it was essentially no better than doing nothing. Cherries may help with another kind of arthritis called gout, but they failed when it came to osteoarthritis.

However, strawberries did decrease inflammation. In fact, in a randomized, double-blind, crossover trial, dietary strawberries were indeed found to have a significant analgesic effect, causing a significant decrease in pain. There are tumor necrosis factor inhibitor drugs on the market now available for the low, low cost of only about $40,000 a year. For that kind of money, you’d want some really juicy side effects, and they do not disappoint—like an especially fatal lymphoma. I think I’ll stick with the strawberries.

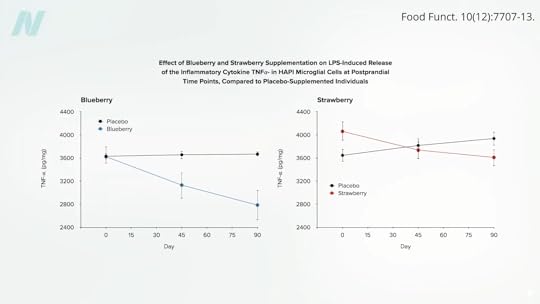

One reason we suspected berries might be helpful is that when people consumed the equivalent of a cup of blueberries or two cups of strawberries daily, and their blood was then applied to cells in a petri dish, it significantly reduced inflammation compared to blood from those who consumed placebo berries, as you can see below and at 2:02 in my video Extra Virgin Olive Oil for Arthritis.

Interestingly, the anti-inflammatory effect increased over time, suggesting that the longer you eat berries, the better. Are there any other foods that have been tested in this way?

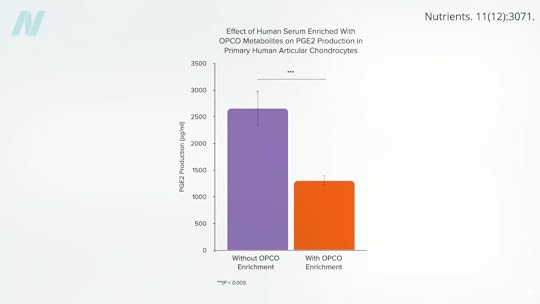

Researchers in France collected cartilage from knee replacement surgeries and then exposed it to blood samples from volunteers who had taken a whopping dose of a grapeseed and olive extract. They saw a significant drop in inflammation, as shown below and at 2:30 in my video.

There haven’t been any human studies putting grapeseeds to the test for arthritis, but an olive extract was shown to decrease pain and improve daily activities in osteoarthritis sufferers. So, does this mean adding olive oil to one’s diet may help? No, because the researchers used freeze-dried olive vegetation water. That’s basically what’s left over after you extract the oil from olives; it’s all the water-soluble components. In other words, it’s all the stuff that’s in an olive that‘s missing from olive oil.

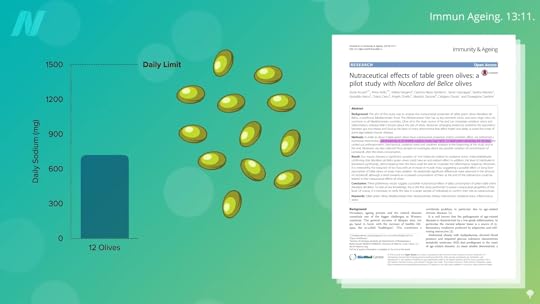

If you give people actual olives, a dozen large green olives a day, you may see a drop in an inflammatory mediator. But according to a systematic review and meta-analysis, olive oil—on its own—does not appear to offer any anti-inflammatory benefits. What about papers that ascribe “remarkable anti-inflammatory activity” to extra virgin olive oil? Their evidence is from rodents. In people, extra virgin olive oil may be no better than butter when it comes to inflammation and worse than even coconut oil.

So, should we just stick to olives? Sadly, a dozen olives could take up nearly half your sodium limit for the entire day, as you can see below and at 3:47 in my video.

When put to the test, extra virgin olive oil did not appear to help with fibromyalgia symptoms either, but it did work better than canola oil in alleviating symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find any studies putting olive oil intake to the test for arthritis. But why then is this blog entitled “Can Olive Oil Compete with Arthritis Drugs?” Because—are you ready for this?—it appears to work topically.

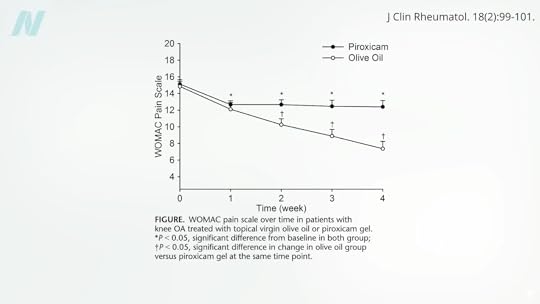

Topical virgin olive oil went up against a gel containing an ibuprofen-type drug for osteoarthritis of the knee in a double-blind, randomized, clinical trial. Just a gram of oil, which is less than a quarter teaspoon, three times a day, costing less than three cents a day, worked! Topical olive oil was significantly better than the drug in reducing pain, as you can see below and at 4:37 in my video.

The study only lasted a month, so is it possible that the olive oil would have continued to work better and better over time?

Is olive oil effective in controlling morning inflammatory pain in the fingers and knees among women with rheumatoid arthritis? The researchers went all out, comparing the use of extra virgin olive oil to rubbing on nothing and also to rubbing on that ibuprofen-type gel, and, evidently, the decrease in the disease activity score in the olive oil group beat out the others.

Doctor’s Note

For more on joint health, see related posts below.

What about eating olive oil? See Olive Oil and Artery Function.

January 13, 2026

The Hidden Costs of Bariatric Surgery

Weight regain after bariatric surgery can have devastating psychological effects.

How Sustainable Is the Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery? I explore that issue in my video of the same name. Most gastric bypass patients end up regaining some of the fat they lose by the third year after surgery, but after seven years, 75% of patients followed at 10 U.S. hospitals maintained at least a 20% weight loss.

The typical trajectory for someone who starts out obese at 285 pounds, for example, would be to drop to an overweight 178 pounds two years after bariatric surgery, but then regain weight up to an obese 207 pounds. This has been chalked up to “grazing” behavior, where compulsive eaters may shift from bingeing (which becomes more difficult post-surgery) to eating smaller amounts constantly throughout the day. In a group of women followed for eight years after gastric bypass surgery, about half continued to describe episodes of disordered eating. As one pediatric obesity specialist described, “I have seen many patients who put chocolate bars into a blender with some cream, just to pass technically installed obstacles [e.g., a gastric band].”

Bariatric surgery advertising is filled with “happily-ever-after” fairytale narratives of cherry-picked outcomes offering, as one ad analysis put it, “the full Cinderella-romance happy ending.” This may contribute to the finding that patients often overestimate the amount of weight they’ll lose with the procedure and underestimate the difficulty of the recovery process. Surgery forces profound changes in eating habits, requiring slow, small bites that have been thoroughly chewed. Your stomach goes from the volume of two softballs down to the size of half a tennis ball in stomach stapling and half a ping-pong ball in the case of gastric bypass or banding.

As you can imagine, “weight regain after bariatric surgery can have a devastating effect psychologically as patients feel that they have failed their last option”—their last resort. This may explain why bariatric surgery patients face a high risk of depression. They also have an increased risk of suicide.

Severe obesity alone may increase the risk of suicidal depression, but even at the same weight, those going through surgery appear to be at a higher risk. At the same BMI (body mass index), age, and gender, bariatric surgery patients have nearly four times the odds of self-harm or attempted suicide compared with those who did not undergo the procedure. Most convincingly, so-called “mirror-image analysis” comparing patients’ pre- and post-surgery events showed the odds of serious self-harm increased after surgery.

About 1 in 50 bariatric surgery patients end up killing themselves or being hospitalized for self-harm or attempted suicide. And this only includes confirmed suicides, excluding masked attempts such as overdoses classified as having “undetermined intention.” Bariatric surgery patients may also have an elevated risk of accidental death, though some of this could be due to changes in alcohol metabolism. When individuals who have had a gastric bypass were given two shots of vodka, their blood alcohol level surpassed the legal driving limit within minutes due to their altered anatomy. It’s unclear whether this plays a role in the 25% increase in prevalence of alcohol problems noted during the second postoperative year.

Even those who successfully lose their excess weight and keep it off appear to have a hard time coping. Ten years out, though physical health-related quality of life may improve, general mental health can significantly deteriorate compared to pre-surgical levels, even among those who lost the most weight. Ironically, there’s a common notion that bariatric surgery is for “cheaters” who take the easy way out by choosing the “low-effort” method of weight loss.

Shedding the weight may not shed the stigma of prior obesity. Studies suggest that “in the eyes of others, knowing that an individual was at one time fat will lead him/her to always be treated like a fat person.” And there can be a strong anti-surgery bias on top of that—those who chose the scalpel to lose weight over diet or exercise were rated more negatively (for example, being considered less physically attractive). One can imagine how remaining a target of prejudice even after joining the “in-group” could potentially undercut psychological well-being.

There can also be unexpected physical consequences of massive weight loss, like large hanging flaps of excess skin. Beyond being heavy and uncomfortable and interfering with movement, the skin flaps can result in itching, irritation, dermatitis, and skin infections. Getting a panniculectomy (removing the abdominal “apron” of hanging skin) can be expensive, and its complication rate can exceed 50%, with dehiscence (rupturing of the surgical wound) one of the most common complications.

“Even if surgery proves sustainably effective,” wrote the founding director of Yale University’s Prevention Research Center, “the need to rely on the rearrangement of natural gastrointestinal anatomy as an alternative to better use of feet and forks [exercise and diet] seems a societal travesty.”

In the Middle Ages, starving peasants dreamed of gastronomic utopias where food just rained down from the sky. The English called it the Kingdom of Cockaigne. Little could medieval fabulists predict that many of their descendants would not only take permanent residence there but also cut out parts of their stomachs and intestines to combat the abundance. Critics have pointed out the irony of surgically altering healthy organs to make them dysfunctional—malabsorptive—on purpose, especially when it comes to operating on children. Bariatric surgery for kids and teens has become widespread and is being performed on children as young as five years old. Surgeons defend the practice by arguing that growing up fat can leave “‘emotional scars’ and lifelong social retardation.”

Promoters of preventive medicine may argue that bariatric surgery is the proverbial “ambulance at the bottom of the cliff.” In response, proponents of pediatric bariatric surgery have written: “It is often pointed out that we should focus on prevention. Of course, I agree. However, if someone is drowning, I don’t tell them, ‘You should learn how to swim’; no, I rescue them.”

A strong case can be made that the benefits of bariatric surgery far outweigh the risks if the alternative is remaining morbidly obese, which is estimated to shave up to a dozen or more years off one’s life. Although there haven’t been any data from randomized trials yet to back it up, compared to non-operated obese individuals, those getting bariatric surgery would be expected to live significantly longer on average. No wonder surgeons have consistently framed the elective surgery as a life-or-death necessity. This is a false dichotomy, though. The benefits only outweigh the risks if there are no other alternatives. Might there be a way to lose weight healthfully without resorting to the operating table? That’s what my book How Not to Diet is all about.

Doctor’s Note

My book How Not to Diet is focused exclusively on sustainable weight loss. Check it out from your library or pick it up from wherever you get your books. (All proceeds from my books are donated to charity.)

This is the final segment in a four-part series on bariatric surgery, which includes:

The Mortality Rate of Bariatric Weight-Loss Surgery The Complications of Bariatric Weight-Loss Surgery Bariatric Surgery vs. Diet to Reverse DiabetesThis blog contains information regarding suicide. If you or anyone you know is exhibiting suicide warning signs, please get help. Go to https://988lifeline.org for more information.

January 8, 2026

Is Surgery Necessary to Reverse Diabetes?

Losing weight without rearranging your gastrointestinal anatomy carries advantages beyond just the lack of surgical risk.

The surgical community objects to the characterization of bariatric surgery as internal jaw wiring and cutting into healthy organs just to discipline people’s behavior. They’ve even renamed it “metabolic surgery,” suggesting the anatomical rearrangements cause changes in digestive hormones that offer unique physiological benefits. As evidence, they point to the remarkable remission rates for type 2 diabetes.

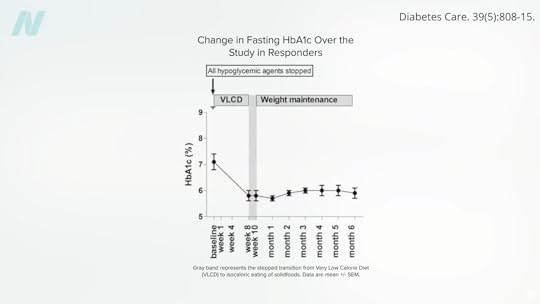

After bariatric surgery, about 50% of obese people with diabetes and 75% of “super-obese” diabetics go into remission, meaning they have normal blood sugar levels on a regular diet without any diabetes medication. The normalization of blood sugar can happen within days after the surgery. And 15 years after the surgery, 30% remained free from their diabetes, compared to a 7% remission rate in a nonsurgical control group. Are we sure it was the surgery, though?

One of the most challenging parts of bariatric surgery is lifting the liver. Since obese individuals tend to have such large, fatty livers, there is a risk of liver injury and bleeding. An enlarged liver is one of the most common reasons a less invasive laparoscopic surgery can turn into a fully invasive open surgery, leaving the patient with a large belly scar, along with an increased risk of wound infections, complications, and recovery time. But lose even just 5% of your body weight, and your fatty liver may shrink by 10%. That’s why those awaiting bariatric surgery are put on a diet. After surgery, patients are typically placed on an extremely low-calorie liquid diet for weeks. Could their improvement in blood sugar levels just be from the caloric restriction, rather than some sort of surgical metabolic magic? Researchers decided to put it to the test.

At a bariatric surgery clinic at the University of Texas, patients with type 2 diabetes scheduled for a gastric bypass volunteered to stay in the hospital for 10 days to follow the same extremely low-calorie diet—less than 500 calories a day—that they would be placed on before and after surgery, but without undergoing the procedure itself. After a few months, once they had regained the weight, the same patients then had the actual surgery and repeated their diet, matched day to day. This allowed researchers to compare the effects of caloric restriction with and without the surgical procedure—the same patients, the same diet, just with or without the surgery. If there were some sort of metabolic benefit to the anatomical rearrangement, the patients would have done better after the surgery, but, in some ways, they actually did worse.

The caloric restriction alone resulted in similar improvements in blood sugar levels, pancreatic function, and insulin sensitivity, but several measures of diabetic control improved significantly more without the surgery. The surgery seemed to put them at a metabolic disadvantage.

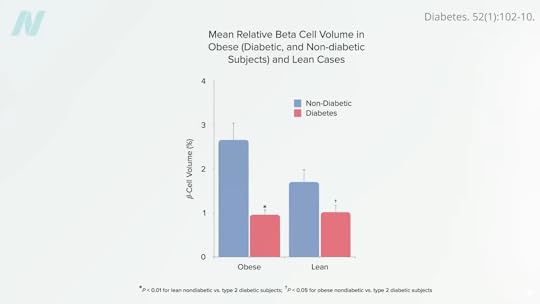

Caloric restriction works by first mobilizing fat out of the liver. Type 2 diabetes is thought to be caused by fat building up in the liver and spilling over into the pancreas. Everyone may have a “personal fat threshold” for the safe storage of excess fat. When that limit is exceeded, fat gets deposited in the liver, where it can cause insulin resistance. The liver may then offload some of the fat (in the form of a fat transport molecule called VLDL), which can then accumulate in the pancreas and kill off the cells that produce insulin. By the time diabetes is diagnosed, half of our insulin-producing cells may have been destroyed, as seen below and at 3:36 in my video Bariatric Surgery vs. Diet to Reverse Diabetes. Put people on a low-calorie diet, though, and this entire process can be reversed.

A large enough calorie deficit can cause a profound drop in liver fat sufficient to resurrect liver insulin sensitivity within seven days. Keep it up, and the calorie deficit can decrease liver fat enough to help normalize pancreatic fat levels and function within just eight weeks. Once you drop below your personal fat threshold, you should then be able to resume normal caloric intake and still keep your diabetes at bay, as seen below and at 4:05 in my video.

The bottom line: Type 2 diabetes is reversible with weight loss, if you catch it early enough.

Lose more than 30 pounds (13.6 kilograms), and nearly 90% of those who have had type 2 diabetes for less than four years can achieve non-diabetic blood sugar levels (suggesting diabetes remission), whereas it may only be reversible in 50% of those who’ve lived with the disease for eight or more years. That’s by losing weight with diet alone, though. For people with diabetes, losing more than twice as much weight with bariatric surgery, diabetes remission may only be around 75% of those who’ve had the disease for up to six years and only about 40% for those who’ve had diabetes longer, as seen below and at 4:41 in my video.

Losing weight without surgery may offer other benefits as well. Individuals with diabetes who lose weight with diet alone can significantly improve markers of systemic inflammation, such as tumor necrosis factor, whereas levels significantly worsened when about the same amount of weight was lost from a gastric bypass.

What about diabetic complications? One reason to avoid diabetes is to avoid its associated conditions, like blindness or kidney failure requiring dialysis. Reversing diabetes with bariatric surgery can improve kidney function, but, surprisingly, it may not prevent the occurrence or progression of diabetic vision loss—perhaps because bariatric surgery affects quantity but not necessarily quality when it comes to diet. This reminds me of a famous study published in The New England Journal of Medicine that randomized thousands of people with diabetes to an intensive lifestyle program focused on weight loss. Ten years in, the study was stopped prematurely because the participants weren’t living any longer or having any fewer heart attacks. This may be because they remained on the same heart-clogging diet but just in smaller portions.

Doctor’s Note

This is the third blog in a four-part series on bariatric surgery. If you missed the first two, check out The Mortality Rate of Bariatric Weight-Loss Surgery and The Complications of Bariatric Weight-Loss Surgery.

My book How Not to Diet is focused exclusively on sustainable weight loss. Check it out from your local library, or pick it up from wherever you get your books. (All proceeds from my books are donated to charity.)

January 6, 2026

Top 10 NutritionFacts.org Videos of 2025

We create more than a hundred new videos every year. They are the culmination of countless hours of research. We comb through tens of thousands of scientific papers from the peer-reviewed medical literature so busy people like you don’t have to.

In 2025, I covered a wide variety of hot topics. I released an extensive series on Ozempic, updates on vitamin B12, and, of course, a lot on aging and anti-aging based on my research for How Not to Age. Which videos floated to the top last year?

#10 How Much Vitamin B12 Do We Need Each Day?

How are the recommended daily and weekly doses of vitamin B12 derived?

#9 The Best Way to Boost NAD+: Supplements vs. Diet (webinar recording)

This webinar wrapped up the pros and cons of all the NAD+ supplements and the ways to naturally boost NAD+ with diet and lifestyle. (Did you know we now offer a growing library of on-demand webinars for CME credits? To learn more and to register, visit us on the LearnWorlds platform.)

#8 How to Improve Your Heart Rate Variability

A healthy heart doesn’t beat like a metronome.

#7 The Best Foods for Your Skin

Greens, apples, tomato paste, and grapes are put to the test as edible skin care candidates.

#6 Friday Favorites: Foods That Cause Inflammation and Those That Reduce It

This is a popular combination of two earlier videos, exploring which foods are the worst when it comes to triggering inflammation within hours of consumption and what an anti-inflammatory diet looks like?

#5 The Healthiest Way to Drink Coffee

Why do those who drink filtered coffee tend to live longer than those who drink unfiltered coffee?

#4 Is One Egg a Day Too Much?

*Spoiler alert*: Meta-analyses of studies involving more than 10 million participants confirm that greater egg consumption confers a higher risk of premature death from all causes.

#3 Do Not Eat Pawpaws

Pawpaw fruits, like soursop, guanabana, sweetsop, sugar apple, cherimoya, and custard apple, contain neurotoxins that may cause a neurodegenerative disease.

#2 The Highest Antioxidant: Apple, Bean, Berry, Lentil, or Nut?

Remember these kinds of videos from way back when? I brought them back! Of course, the best apple, bean, berry, lentil, and nut are the ones you’ll eat the most of, but if you don’t have a strong preference, which ones have the highest antioxidant power?

#1 How to Slow Cancer Growth

The fact that this video was so popular is validation for my plan to take on cancer after How Not to Hurt, my upcoming book on lifestyle approaches to pain management, which should be out in (fingers crossed) December 2026. This video explains how, at this very moment, many of us have tumors growing inside our bodies, so we cannot wait to start eating and living more healthfully.

Thank you for being a part of this community. We gained more than 170,000 new subscribers on YouTube in 2025, and the number of people we can reach with this life-saving, life-changing information continues to grow.

January 1, 2026

Bariatric Surgery: Risks in the OR and Beyond

The extent of risk from bariatric weight-loss surgery may depend on the skill of the surgeon.

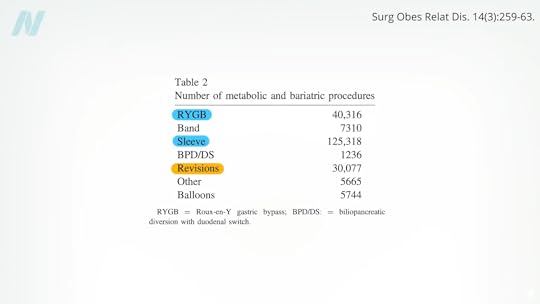

After sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, the third most common bariatric procedure is a revision to fix a previous bariatric procedure, as you can see below and at 0:16 in my video The Complications of Bariatric Weight-Loss Surgery.

Up to 25% of bariatric patients have to go back into the operating room for problems caused by their first bariatric surgery. Reoperations are even riskier, with up to 10 times the mortality rate, and there is “no guarantee of success.” Complications include leaks, fistulas, ulcers, strictures, erosions, obstructions, and severe acid reflux.

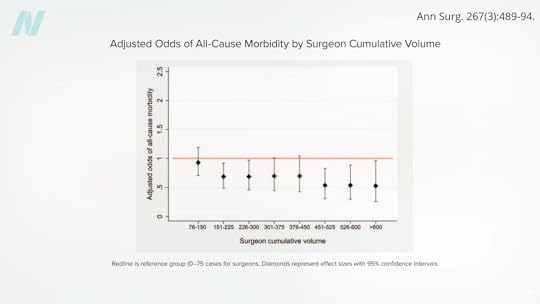

The extent of risk may depend on the skill of the surgeon. In a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine, bariatric surgeons voluntarily submitted videos of themselves performing surgery to a panel of their peers for evaluation. Technical proficiency varied widely and was related to the rates of complications, hospital readmissions, reoperations, and death. Patients operated on by less competent surgeons suffered nearly three times the complications and five times the rate of death.

“As with musicians or athletes, some surgeons may simply be more talented than others”—but practice may help make them perfect. Gastric bypass is such a complicated procedure that the learning curve may require 500 cases for a surgeon to master the procedure. Risk for complications appears to plateau after about 500 cases, with the lowest risk found among surgeons who had performed more than 600 bypasses. The odds of not making it out alive may be double under the knife of those who had performed less than 75 compared to more than 450, as seen below and at 1:47 in my video.

So, if you do choose to undergo the operation, I’d recommend asking your surgeon how many procedures they’ve done, as well as choosing an accredited bariatric “Center of Excellence,” where surgical mortality appears to be two to three times lower than non-accredited institutions.

It’s not always the surgeon’s fault, though. In a report entitled “The Dangers of Broccoli,” a surgeon described a case in which a woman went to an all-you-can-eat buffet three months after a gastric bypass operation. She chose really healthy foods—good for her!—but evidently forgot to chew. Her staples ruptured, and she ended up in the emergency room, then the operating room. They opened her up and found “full chunks of broccoli, whole lima beans, and other green leafy vegetables” inside her abdominal cavity. A cautionary tale to be sure, but perhaps one that’s less about chewing food better after surgery than about chewing better foods before surgery—to keep all your internal organs intact in the first place.

Even if the surgical procedure goes perfectly, lifelong nutritional replacement and monitoring are required to avoid vitamin and mineral deficits. We’re talking about more than anemia, osteoporosis, or hair loss. Such deficits can cause full-blown cases of life-threatening deficiencies, such as beriberi, pellagra, kwashiorkor, and nerve damage that can manifest as vision loss years or even decades after surgery in the case of copper deficiency. Tragically, in reported cases of severe deficiency of a B vitamin called thiamine, nearly one in three patients progressed to permanent brain damage before the condition was caught.

The malabsorption of nutrients is intentional for procedures like gastric bypass. By cutting out segments of the intestines, you can successfully impair the absorption of calories—at the expense of impairing the absorption of necessary nutrition. Even people who just undergo restrictive procedures like stomach stapling can be at risk for life-threatening nutrient deficiencies because of persistent vomiting. Vomiting is reported by up to 60% of patients after bariatric surgery due to “inappropriate eating behaviors.” (In other words, trying to eat normally.) The vomiting helps with weight loss, similar to the way a drug for alcoholics called Antabuse can be used to make them so violently ill after a drink that they eventually learn their lesson.

“Dumping syndrome” can work the same way. A large percentage of gastric bypass patients can suffer from abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, bloating, fatigue, or palpitations after eating calorie-rich foods, as they bypass your stomach and dump straight into your intestines. As surgeons describe it, this is a feature, not a bug: “Dumping syndrome is an expected and desired part of the behavior modification caused by gastric bypass surgery; it can deter patients from consuming energy-dense food.

Doctor’s Note

This is the second in a four-part series on bariatric surgery. If you missed the first one, see The Mortality Rate of Bariatric Weight-Loss Surgery.

Up next: Bariatric Surgery vs. Diet to Reverse Diabetes and How Sustainable Is the Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery?.

My book How Not to Diet is focused exclusively on sustainable weight loss. Check it out from your local library, or pick it up from wherever you get your books. (All proceeds from my books are donated to charity.)