Michael Greger's Blog

November 20, 2025

Celebrating Native American Heritage Month with Chef Lois Ellen Frank, Ph.D.

For more about Chef Lois, check out this interview.

“Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez and First Lady Phefelia Nez have been vocal proponents of healthy eating. President Nez found that plant-based eating shortened his recovery time after long-distance runs and helps him to maintain his weight loss. First Lady Nez provided us with one of her family-favorite soup recipes that we modified. We used the modified version for a course called Native Food for Life Online, offered through the American Indian Institute (AII) and the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM). Minestrone is its Italian name, but the ingredients in this soup originated in the Americas. Chef Walter Whitewater said that growing up on the Navajo Nation, he used to harvest wild onions, carrots, garlic, and spinach. With the addition of frozen corn, canned beans, and zucchini squash, as well as the pasta, all foods that most community members have on hand or receive as part of the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR), our version of this recipe is a favorite of Chef Walter. Serve with No Fry Frybread, No Fry Blue Corn Frybread, Homemade White Corn Tortillas, or Blue Corn Tortillas.” – Chef Lois Ellen Frank

Navajo Minestrone Soup

Ingredients

Makes approximately 2 quarts

2 cups cooked whole-grain pasta, such as mini farfalle (bow-tie pasta), penne, or elbows (approx. 1 cup uncooked)

1 tablespoon bean juice or water

1 small yellow onion, diced (approx. 1 cup)

3 carrots, peeled, cut into ⅛-inch-thick sticks, and halved into half-moon slices (approx. 1 cup)

2 stalks celery, sliced (approx. 1 cup)

½ cup frozen sweet corn kernels

1 tablespoon roasted garlic

1 zucchini, cut into ½-inch cubes (approx. 1 cup)

1 (15 oz.) can diced tomatoes, organic and no salt added, if possible

2 tablespoons tomato paste

1 cup spinach, fresh or frozen

5 cups water

1 (15 oz.) can dark red kidney beans, drained and rinsed (approx. 1½ cups)

1 (15 oz.) can pinto beans, drained and rinsed (approx. 1½ cups)

1 tablespoon fresh basil, finely chopped

½ teaspoon fresh oregano, finely chopped

½ teaspoon fresh thyme, finely chopped

2 teaspoons New Mexico red chile powder, mild

1 tablespoon flat leaf parsley, finely chopped

¼ teaspoon black pepper, or to taste (optional)

Instructions

In a large, cook the pasta according to the package directions. Remove from heat, drain the cooking water, rinse with cold water to stop the pasta from cooking, and set aside.

In a separate soup pot, heat the bean juice over medium-high heat until hot but not smoking. Sauté the onion for approximately 4 minutes, stirring occasionally to prevent burning. Add the carrots and the celery, and cook for an additional 5 to 6 minutes, stirring but letting the vegetables begin to caramelize. Add the corn and cook for another 2 minutes, stirring once to prevent burning. Add the roasted garlic and cook for another minute, stirring constantly to mix the garlic into the other ingredients. (The bottom of your pan will turn brown, and the vegetables should begin to caramelize.) Add the zucchini and cook for another 3 minutes, stirring to prevent burning. Add the diced tomatoes and tomato paste, stirring to completely mix into the other vegetables and deglaze the bottom of the pan. Add the spinach and water and bring to a boil. Then cover, reduce the heat to medium low, and let simmer, covered, for 10 minutes, stirring once or twice.

Add the canned kidney and pinto beans, stirring them to blend with all the ingredients, then add the basil, oregano, thyme, red chile powder, flat leaf parsley, and black pepper, if using. Return to a boil, then reduce the heat and let simmer for another 10 minutes.

Taste, season with more of any of the spices, if desired. Add the cooked pasta, stir, and bring to a boil. Cook for an additional 1 to 2 minutes until the soup is completely hot. (Do not cook the soup too long, as the cooked pasta may become overcooked.) Remove from heat. Serve.

Recipe adapted from Seed to Plate, Soil to Sky: Modern Plant-Based Recipes Using Native American Ingredients by Lois Ellen Frank with Culinary Advisor Walter Whitewater. Copyright © 2023 by Lois Ellen Frank. Published by Balance Publishing, an imprint of Hachette Book Group. All rights reserved.

You can find Chef Lois Ellen Frank here.

November 18, 2025

Plant-Based Hospital Menus

The American Medical Association passed a resolution encouraging hospitals to offer healthy plant-based food options.

“Globally, 11 million deaths annually are attributable to dietary factors, placing poor diet ahead of any other risk factor for death in the world.” Given that diet is our leading killer, you’d think that nutrition education would be emphasized during medical school and training, but there is a deficiency. A systematic review found that, “despite the centrality of nutrition to a healthy lifestyle, graduating medical students are not supported through their education to provide high-quality, effective nutrition care to patients…”

It could start in undergrad. What’s more important? Learning about humanity’s leading killer or organic chemistry?

In medical school, students may average only 19 hours of nutrition out of thousands of hours of instruction, and they aren’t even being taught what’s most useful. How many cases of scurvy and beriberi, diseases of dietary deficiency, will they encounter in clinical practice? In contrast, how many of their future patients will be suffering from dietary excesses—obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease? Those are probably a little more common than scurvy or beriberi. “Nevertheless, fully 95% of cardiologists [surveyed] believe that their role includes personally providing patients with at least basic nutrition information,” yet not even one in ten feels they have an “expert” grasp on the subject.

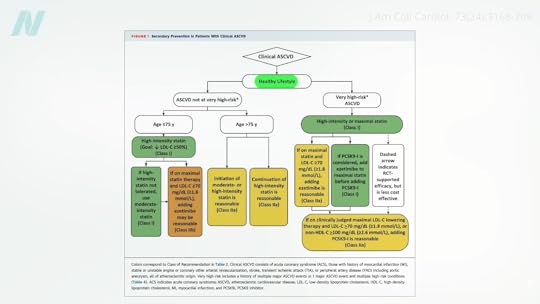

If you look at the clinical guidelines for what we should do for our patients with regard to our number one killer, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, all treatment begins with a healthy lifestyle, as shown below and at 1:50 in my video Hospitals with 100-Percent Plant-Based Menus.

“Yet, how can clinicians put these guidelines into practice without adequate training in nutrition?”

Less than half of medical schools report teaching any nutrition in clinical practice. In fact, they may be effectively teaching anti-nutrition, as “students typically begin medical school with a greater appreciation for the role of nutrition in health than when they leave.” Below and at 2:36 in my video is a figure entitled “Percentage of Medical Students Indicating that Nutrition is Important to Their Careers.” Upon entry to different medical schools, about three-quarters on average felt that nutrition is important to their careers. Smart bunch. Then, after two years of instruction, they were asked the same question, and the numbers plummeted. In fact, at most schools, it fell to 0%. Instead of being educated, they got de-educated. They had the notion that nutrition is important washed right out of their brains. “Thus, preclinical teaching”— the first two years of medical school—“engenders a loss of a sense of the relevance of the applied discipline of nutrition.”

Following medical school, during residency, nutrition education is “minimal or, more typically, absent.” “Major updates” were released in 2018 for residency and fellowship training requirements, and there were zero requirements for nutrition. “So you could have an internal medicine graduate who comes out of a terrific program and has learned nothing—literally nothing—about nutrition.”

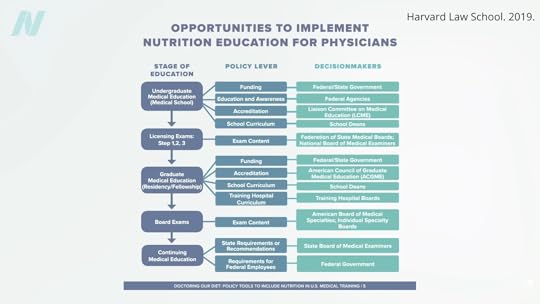

“Why is diet not routinely addressed in both medical education and practice already, and what should be done about that?” One of the “reasons for the medical silence in nutrition” is that, “sadly…nutrition takes a back seat…because there are few financial incentives to support it.” What can we do about that? The Food Law and Policy Clinic at Harvard Law School identified a dozen different policy levers at all stages of medical education and the kinds of policy recommendations there could be for the decision-makers, as you can see here and at 3:48 in my video.

For instance, the government could require doctors working for Veterans Affairs (VA) to get at least some courses in nutrition, or we could put questions about nutrition on the board exams so schools would be pressured to teach it. As we are now, even patients who have just had a heart attack aren’t changing their diet. Doctors may not be telling them to do so, and hospitals may be actively undermining their future with the food they serve.

The good news is that the American Medical Association (AMA) has passed a resolution encouraging hospitals to offer healthy food options. What a concept! “Our AMA hereby calls on [U.S.] Health Care Facilities to improve the health of patients, staff, and visitors by: (a) providing a variety of healthy food, including plant-based meals, and meals that are low in saturated and trans fat, sodium, and added sugars; (b) eliminating processed meats from menus; and (c) providing and promoting healthy beverages.” Nice!

“Similarly, in 2018, the State of California mandated the availability of plant-based meals for hospital patients,” and there are hospitals in Gainesville (FL), the Bronx, Manhattan, Denver, and Tampa (FL) that “all provide 100% plant-based meals to their patients on a separate menu and provide educational materials to inpatients to improve education on the role of diet, especially plant-based diets, in chronic illness.”

Let’s check out some of their menu offerings: How about some lentil Bolognese? Or a cauliflower scramble with baked hash browns for breakfast, mushroom ragu for lunch, and, for supper, white bean stew, salad, and fruit for dessert. (This is the first time a hospital menu has ever made me hungry!)

The key to these transformations was “having a physician advocate and increasing education of staff and patients on the benefits of eating more plant-based foods.” A single clinician can spark change in a whole system, because science is on their side. “Doctors have a unique position in society” to influence policy at all levels; it’s about time we used it.

For more on the ingrained ignorance of basic clinical nutrition in medicine, see the related posts below.

November 13, 2025

3-MCPD in Refined Cooking Oils

There is another reason to avoid palm oil and question the authenticity of extra-virgin olive oil.

The most commonly used vegetable oil in the world today is palm oil. Pick up any package of processed food in a box, bag, bottle, or jar, and the odds are it will have palm oil. Palm oil not only contains the primary cholesterol-raising saturated fat found mostly in meat and dairy, but concerns have been raised about its safety, given the finding that it may contain a potentially toxic chemical contaminant known as 3-monochloropropane-1,2-diol, otherwise known as 3-MCPD, which is formed during the heat treatment involved in the refining of vegetable oils. So, these contaminants end up being “widespread in refined vegetable oils and fats and have been detected in vegetable fat-containing products, including infant formulas.”

Although 3-MCPD has been found in all refined vegetable oils, some are worse than others. The lowest levels of the toxic contaminants were found in canola oil, and the highest levels were in palm oil. Based on the available data, this may result in “a significant amount of human exposure,” especially when used to deep-fry salty foods, like french fries. In fact, just five fries could blow through the tolerable daily intake set by the European Food Safety Authority. If you only eat such foods once in a while, it shouldn’t be a problem, but if you’re eating fries every day or so, this could definitely be a health concern.

Because the daily upper limit is based on body weight, particularly high exposure values were calculated for infants who were on formula rather than breast milk, since formula is made from refined oils, which—according to the European Food Safety Authority—may present a health risk. Estimated U.S. infant exposures may be three to four times worse.

If infants don’t get breast milk, “there is basically no alternative to industrially produced infant formula.” As such, the vegetable oil industry needs to find a way to reduce the levels of these contaminants. This is yet another reason that breastfeeding is best whenever possible.

What can adults do to avoid exposure? Since these chemicals are created in the refining process of oils, what about sticking to unrefined oils? Refined oils have up to 32 times the 3-MCPD compared to their unrefined counterparts, but there is an exception: toasted sesame oil. Sesame oil is unrefined; manufacturers just squeeze the sesame seeds. But, because they are squeezing toasted sesame seeds, the 3-MCPD may have come pre-formed.

Virgin oils are, by definition, unrefined. They haven’t been deodorized, the process by which most of the 3-MCPD is formed. In fact, that’s how you can discriminate between the various processing grades of olive oil. If your so-called extra virgin olive oil contains MCPD, then it must have been diluted with some refined olive oil. The ease of adulterating extra virgin olive oil, the difficulty of detection, the economic drivers, and the lack of control measures all contribute to extra virgin olive oil’s susceptibility to fraud. How widespread a problem is it?

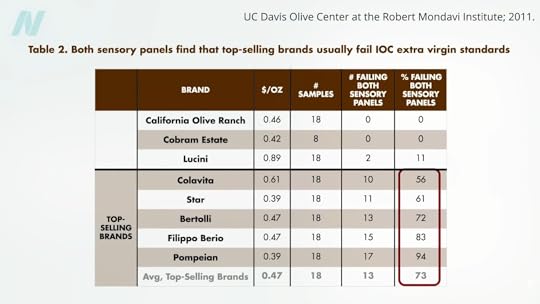

Researchers tested 88 bottles labeled as extra virgin olive oil and found that only 33 were found to be authentic. Does it help to stick to the top-selling imported brands of extra virgin olive oil? In that case, 73% of those samples failed. Only about one in four appeared to be genuine, and not a single brand had even half its samples pass the test, as you can see here and at 3:32 in my video 3-MCPD in Refined Cooking Oils.

Doctor’s Note

If you missed the previous post where I introduced 3-MCPD, see The Side Effects of 3-MCPD in Bragg’s Liquid Aminos.

There is no substitute for human breast milk. We understand this may not be possible for adoptive families or those who use surrogates, though. In those cases, look for a nearby milk bank.

November 11, 2025

Celebrating Veterans Day with Ronnie Penn

We had the pleasure of talking with Ronnie Penn about his military service, his work as a chef and a coach, and what Veterans Day means to him. We hope you enjoy this interview.

Thank you for your service, Ronnie. We’re honored to speak with you today. Can you start by sharing a bit about your background? What inspired you to enlist, and when did your military journey begin?

I grew up wanting to serve something bigger than myself, and the Marine Corps gave me that opportunity. I enlisted in 2004 and deployed to Iraq during Operation Iraqi Freedom and to Afghanistan from 2012 to 2014. Later, I served in the Coast Guard as a chef, which opened a whole new chapter in how I looked deeper into nutrition. Service taught me discipline, resilience, and the importance of teamwork—qualities I carry into everything I do today.

How did your time in the military shape who you are today? Is there anything in particular about your service that you would like to share?

The military taught me to stay calm under pressure and adapt quickly. Whether it was on deployment overseas or working with my shipmates in the galley, I learned how much impact food, mindset, and discipline can have on performance and morale. Those lessons shaped who I am now—not only as a veteran, but also as a coach who helps others take control of their health.

Were there any habits or disciplines from your military experience that helped in your transition to plant-based living or in your work today as a coach?

Two habits stuck with me: structure and accountability. In the Marines, every detail mattered. That same mindset helps me stick to meal prep, training schedules, and coaching clients. It also made the transition to plant-based eating easier because I was already used to planning ahead and being intentional about what I put into my body.

You’ve spoken about health issues that arose during competition prep, which ultimately led you to switch to a plant-based diet. What symptoms were you experiencing at the time, and what physical or medical changes did you notice after the transition?

When I was competing in bodybuilding, I pushed my body hard—lots of animal protein, supplements, and restrictive dieting. Over time, I developed digestive issues and constant fatigue. Switching to a whole food, plant-based diet changed everything. My digestion improved, and my energy came back. It was eye-opening to see how quickly the body can heal when you give it the right fuel.

Did you encounter any challenges accessing or preparing plant-based foods during active service? How did you make it work in that environment?

Back then, plant-based options were limited, especially on deployment. I loaded up on oatmeal, beans, rice, fruits, and vegetables whenever I could, and I had to get creative, too. I learned how to make simple meals with what was available, and that creativity carried into my role as a chef in the Coast Guard.

Were there any particularly memorable reactions from your shipmates or peers when you introduced them to plant-based meals as a chef in the Coast Guard?

At first, my shipmates were skeptical. But once I started cooking hearty meals, like lentil stews, veggie burritos, or black bean burgers, they were surprised by how satisfying plant-based food could be. I still remember one crew member saying, “I didn’t even miss the meat.” Moments like that showed me how powerful food can be in changing perceptions.

You’ve become a vocal advocate for plant-based eating in high-performance settings. Are there any particular studies or sources that informed or reinforced your choices?

The work of Dr. Greger and NutritionFacts.org has had a huge impact on me. I also leaned on research from the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM) and books like The China Study. Seeing the science laid out gave me confidence that a plant-based diet wasn’t just personal preference; it was evidence-based. Also, the Netflix documentaries What the Health and Forks Over Knives were also extremely effective influences.

In your opinion, how can education about preparing whole plant foods be a path forward for people to achieve better health?

Education is the key. When people learn how to prepare whole plant foods in simple, tasty ways, it removes the intimidation factor. Once they see how it can lower blood pressure, improve energy, and even prevent chronic disease, it clicks. Food literacy is one of the most powerful tools we have for better health.

Please tell us about your online personal training program and app. What inspired you to start these projects, and how do they help you reach more people with your message?

I started my online fitness coaching because I wanted to reach people beyond the gym. Not everyone can afford a trainer, but most people have a smartphone. Through my training app, I provide meal plans, workout routines, and a grocery list with accountability check-ins. It’s a way to scale what I do—helping people take small, daily steps toward a healthier life.

Lastly, what does Veterans Day mean to you? Is there anything you would like to share with your fellow veterans?

Veterans Day is a moment of reflection for me. It’s about honoring the sacrifices of those who served, as well as reminding myself to live in a way that makes that service meaningful. I want to encourage other veterans to take care of themselves, not just physically, but mentally and emotionally, too. We served our country; now it’s time to serve ourselves by living healthy and purposeful lives.

To learn more about Ronnie, visit his website: https://www.ronniepenn.com/

November 6, 2025

Chlorohydrin 3-MCPD in Bragg’s Liquid Aminos

Chlorohydrin contaminates hydrolyzed vegetable protein products and refined oils.

In 1978, chlorohydrins were found in protein hydrolysates. What does that mean? Proteins can be broken down into amino acids using a chemical process called hydrolysis, and free amino acids (like glutamate) can have taste-enhancing qualities. That’s how inexpensive soy sauce and seasonings like Bragg’s Liquid Aminos are made. This process requires high heat, high pressure, and hydrochloric acid to break apart the protein. The problem is that when any residual fat is exposed to these conditions, it can form toxic compounds called chlorohydrins, which are toxic at least to mice and rats.

Chlorohydrins like 3-MCPD are considered “a worldwide problem of food chemistry,” but no long-term clinical studies on people have been reported to date. The concern is about the detrimental effects on the kidneys and fertility. In fact, there was a time 3-MCPD was considered as a potential male contraceptive because it could so affect sperm production, but research funding was withdrawn after “unacceptable side effects [were] observed in primates.” Researchers found flaccid testes in rats, which is what they were going for, but it caused neurological scars in monkeys.

What do you do when there are no studies in humans? How do you set some kind of safety factor? It isn’t easy, but you can take the lowest observed adverse effect level (LOAEL) in animal studies, which, in this case, was kidney damage, add in some kind of fudge factor, and then arrive at an estimated tolerable daily intake (TDI). For 3-MCPD, this means that high-level consumers of soy sauce may exceed the limit. This was based on extraordinarily high contamination levels, though. Since that study, Europe introduced a regulatory limit of 20 parts per billion (ppb) of 3-MCPD in hydrolyzed vegetable protein products like liquid aminos and soy sauce. The U.S. standards are much laxer, though, setting a “guidance level” of up to 50 times more, 1,000 parts per billion.

I called Bragg’s to see where it fell, and the good news is that it is doing an independent, third-party analysis of its liquid aminos for 3-MCPD. The bad news is that, despite my pleas that it be fully transparent, Bragg’s wouldn’t let me share the results with you. I have seen them, though, but I’m only allowed to confirm they comfortably meet the U.S. standards but fail to meet the European standards.

This is just the start of the 3-MCPD story, though. A study in Italy tested individuals’ urine for 3-MCPD or its metabolites, and 100% of the people turned up positive, confirming that it’s “a widespread food contaminant.” But 100% of people aren’t consuming soy sauce or liquid aminos every day. Remember, the chemical results from a reaction with residual vegetable oil. When vegetable oil itself is refined, when it’s deodorized and bleached, those conditions also lead to the formation of 3-MCPD.

Indeed, we’ve known for years that various foods are contaminated. In what kinds of foods have these kinds of chemicals been detected? Well, if they’re in oils and fats, then they’re in greasy foods made from them: margarine, baked goods, pastries, deep-fried foods, fatty snacks like potato and corn chips, as well as infant formula.

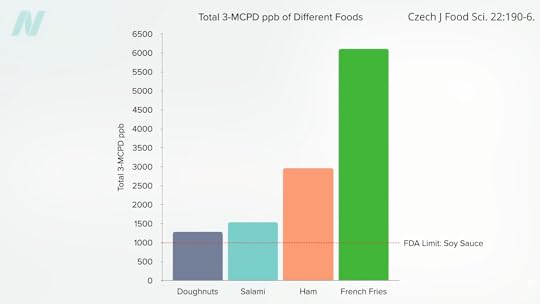

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s limit for soy sauce is 1,000 ppb, but donuts can have more than 1,200 ppb, salami more than 1,500 ppb, ham nearly 3,000 ppb, and French fries in excess of 6,000 ppb, as seen here and at 4:03 in my video The Side Effects of 3-MCPD in Bragg’s Liquid Aminos.

Most of us don’t have to worry about this problem, unless we’re consumers of fried food. Someone weighing about 150 pounds, for example, who eats 116 grams of donuts, would exceed the European Food Safety Authority’s TDI, even if those donuts were the person’s only source of exposure. That’s about two donuts, but the same limit-blowing amount of 3-MCPD could be found in only five French fries.

Doctor’s Note

Believe me, I pleaded with the Bragg’s folks over and over. It’s curious to me that Bragg’s allowed me to talk about where its level of 3-MCPD fell compared to the standards but not say the number itself. At least it’s doing third-party testing.

Learn more about this topic in my video 3-MCPD in Refined Cooking Oils.

You can also check out Friday Favorites: The Side Effects of 3-MCPD in Bragg’s Liquid Aminos and Refined Cooking Oils.

November 4, 2025

Treat the Cause

Treat the underlying cause of chronic lifestyle diseases.

It’s been said that more than 2,000 years ago, Hippocrates declared, “Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food.” In actuality, it appears that he never actually said those words, but there’s “no doubt about the relevance of food…and its role in health and disease states” in his writings. Regardless, 2,000 years ago, disease was thought to arise from a bad sense of “humors,” as you can see here and at 0:32 in my video Lifestyle and Disease Prevention: Your DNA Is Not Your Destiny.

Now, we have science, and there is “an overwhelming body of clinical and epidemiological evidence illustrating the dramatic impact of a healthy lifestyle on reducing all-cause mortality”—meaning death from all causes put together—“and preventing chronic diseases such as coronary heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and cancer.” But don’t those diseases just run in our family? What if we just have bad genes?

According to the esteemed former chair of nutrition at Harvard, for most of the diseases that have contributed “importantly” to mortality in Western peoples, we’ve long known that non-genetic factors often account for at least 80% to 90% of risk. We know this because rates of the leading killers, like major cancers and cardiovascular diseases, vary up to 100-fold around the world, and, “when groups migrate from low- to high-risk countries, their disease rates almost always change to those of the new environment.” Modifiable behavioral factors have been identified, “including specific aspects of diet, overweight, inactivity, and smoking that account for over 70% of stroke and colon cancer, over 80% of coronary heart disease, and over 90% of adult-onset [type 2] diabetes”—diseases that can largely be prevented by our own actions.

If most of the power is in our own hands, why do we allocate massively more resources to treatment than prevention? And speaking of prevention, “even preventive strategies are heavily biased towards pharmacology rather than supporting improvements in diet and lifestyle that could be more cost-effective. For example, treatment of [high] serum cholesterol with statins alone could cost approximately 30 billion dollars per year in the United States and would have only a modest impact on coronary heart disease incidence. The inherent problem is that most pharmacologic strategies don’t address the underlying causes of ill health in Western countries, which are not drug deficiencies.”

Ironically, the chronic diseases that are most amenable to lifestyle treatment are the same ones most profitably treated by drugs. Why? If you don’t change your diet, you have to pop the pills every day for the rest of your life. So, the cash-cow drugs are the very drugs we need the least. “Even though the most widely accepted, well-established chronic disease practice guidelines uniformly call for lifestyle change as the first line of therapy, physicians often do not follow these recommendations.” “By ignoring the root causes of disease and neglecting to prioritize lifestyle measures for prevention, the medical community is placing people at harm.”

“Traditional medical care relies primarily on the application of pharmacologic and surgical interventions after the development of illness,” whereas lifestyle medicine relies primarily on “the use of optimal nutrition (a whole foods, plant-based diet) and exercise in the prevention, arrest, and reversal of chronic conditions leading to premature disability and death. It looks in a holistic way at the underlying causes of illness.”

Dr. Adriane Fugh-Berman, director of PharmedOut, a wonderful organization I’m proud to support, wrote a great editorial entitled “Doctors Must Not Be Lapdogs to Drug Firms.” “The illusion that the relationship between medicine and the drug industry is collegial, professional, and personal is carefully maintained by the drug industry, which actually views all transactions with physicians in finely calculated financial terms…The drug industry is happy to play the generous and genial uncle until physicians want to discuss subjects that are off limits, such as the benefits of diet or exercise, or the relationship between medicine and pharmaceutical companies…Let us not be a lapdog to Big Pharma. Rather than sitting contentedly in our master’s lap, let us turn around and bite something tender.”

Doctor’s Note

The organization I mentioned, PharmedOut, is a project of Georgetown University Medical Center.

For more on Lifestyle Medicine, see related videos below.

October 30, 2025

Ideal vs. Normal Cholesterol Levels

Having a “normal” cholesterol level in a society where it’s normal to die from a heart attack isn’t necessarily a good thing.

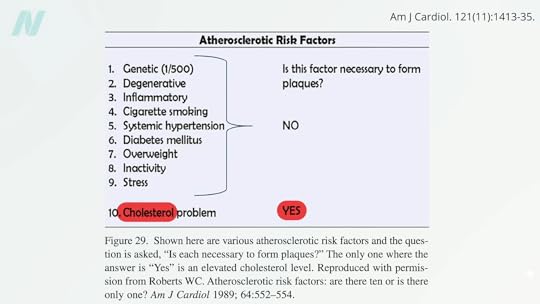

“Consistent evidence” from a variety of sources “unequivocally establishes” that so-called bad LDL cholesterol causes atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease—strokes and heart attacks, our leading cause of death. This evidence base includes hundreds of studies involving millions of people. “Cholesterol is the cause of atherosclerosis,” the hardening of the arteries, and “the message is loud and clear.” “It’s the Cholesterol, Stupid!” noted the editor of the American Journal of Cardiology, William Clifford Roberts, whose CV is more than 100 pages long as he has published about 1,700 articles in peer-reviewed medical literature. Yes, there are at least ten traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis, as seen below and at 1:11 in my video How Low Should You Go for Ideal LDL Cholesterol?, but, as Dr. Roberts noted, only one is required for the progression of the disease: elevated cholesterol.

Your doctor may have just told you that your cholesterol is normal, so you’re relieved. Thank goodness! But, having a “normal” cholesterol level in a society where it’s normal to have a fatal heart attack isn’t necessarily good. With heart disease, the number one killer of men and women, we definitely don’t want to have normal cholesterol levels; we want to have optimal levels—and not optimal by current laboratory standards, but optimal for human health.

Normal LDL cholesterol levels are associated with the hidden buildup of atherosclerotic plaques in our arteries, even in those who have so-called “optimal risk factors by current standards”: blood pressure under 120/80, normal blood sugars, and total cholesterol under 200 mg/dL. If you went to your doctor with those kinds of numbers, you’d likely get a gold star and a lollipop. But, if your doctor used ultrasound and CT scans to actually peek inside your body, atherosclerotic plaques would be detected in about 38% of individuals with those kinds of “optimal” numbers.

Maybe we should define an LDL cholesterol level as optimal only when it no longer causes disease. What a concept! When more than a thousand men and women in their 40s were scanned, having an LDL level under 130 mg/dL left them with atherosclerosis throughout their body, and that’s a cholesterol level at which most lab tests would consider normal.

In fact, atherosclerotic plaques were not found with LDL levels down around 50 or 60, which just so happens to be the levels most people had “before the introduction of western lifestyles.” Indeed, before we started eating a typical American diet, “the majority of the adult population of the world had LDLs of around 50 mg per deciliter (mg/dL)”—so that’s the true normal. “Present average values…should not be regarded as ‘normal.’” We don’t want to have a normal cholesterol based on a sick society; we want a cholesterol that is normal for the human species, which may be down around 30 to 70 mg/dL or 0.8 to 1.8 mmol/L.

“Although an LDL level of 50 to 70 mg/dl seems excessively low by modern American standards, it is precisely the normal range for individuals living the lifestyle and eating the diet for which we are genetically adapted.” Over millions of years, “through the evolution of the ancestors of man,” we’ve consumed a diet centered around whole plant foods. No wonder we have a killer epidemic of atherosclerosis, given the LDL level “we were ‘genetically designed for’ is less than half of what is presently considered ‘normal.’”

In medicine, “there is an inappropriate tendency to accept small changes in reversible risk factors,” but “the goal is not to decrease risk but to prevent atherosclerotic plaques!” So, how low should you go? “In light of the latest evidence from trials exploring the benefits and risks of profound LDLc lowering, the answer to the question ‘How low do you go?’ is, arguably, a straightforward ‘As low as you can!’” “‘Lower’ may indeed be better,” but if you’re going to do it with drugs, then you have to balance that with the risk of the drug’s side effects.

Why don’t we just drug everyone with statins, by putting them in the water supply, for instance? Although it would be great if everyone’s cholesterol were lower, there are the countervailing risks of the drugs. So, doctors aim to use statin drugs at the highest dose possible, achieving the largest LDL cholesterol reduction possible without increasing risk of the muscle damage the drugs may cause. But when you’re using lifestyle changes to bring down your cholesterol, all you get are the benefits.

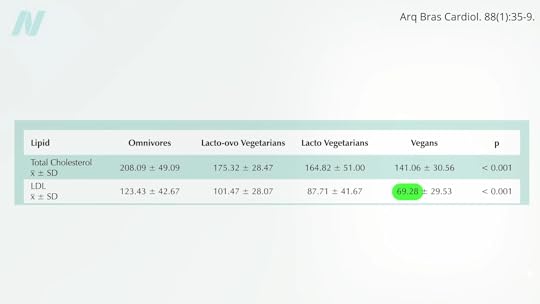

Can we get our LDL low enough with diet alone? Ask some of the country’s top cholesterol experts what they shoot for, “and the odds are good that many will say 70 or so.” So, yes, we should try to avoid the saturated fats and trans fats found in junk foods and meat, and the dietary cholesterol found mostly in eggs, but “it is unlikely anyone can achieve an LDL cholesterol level of 70 mg/dL with a low-fat, low-cholesterol diet alone.” Really? Many doctors have this mistaken impression. An LDL of 70 isn’t only possible on a healthy enough diet, but it may be normal. Those eating strictly plant-based diets can average an LDL that low, as you can see here and at 5:28 in my video.

No wonder plant-based diets are the only dietary patterns ever proven to reverse coronary heart disease in a majority of patients. And their side effects? You get to feel better, too! Several randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that more plant-based dietary patterns significantly improve psychological well-being and quality of life, with improvements in depression, anxiety, emotional well-being, physical well-being, and general health.

For more on cholesterol, see the related posts below.

October 28, 2025

Fasting and Plant-Based Diets for Migraines and Traumatic Brain Injuries

What effects do fasting and a plant-based diet have on TBI and migraines?

An uncontrolled and unpublished study purported to show a beneficial effect of fasting on migraine headaches, but fasting may be more likely to trigger a migraine than help it. In fact, “skipped meals are among the most consistently identified dietary triggers” of headaches in general. In a review of hundreds of fasts at the TrueNorth Health Center in California, the incidence of headache was nearly one in three, but TrueNorth also published a remarkable case report on post-traumatic headache.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that more than a million Americans sustain traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) every year. Chronic pain is a common complication, affecting perhaps three-quarters of those who suffer such an injury. There are drugs, of course, to treat post-traumatic headache. There are always drugs. And if drugs don’t work, there is surgery, cutting the nerves to the head to stop the pain.

What about fasting and plants? A 52-year-old woman presented with a highly debilitating, difficult-to-manage, unremitting, chronic post-traumatic headache. And when I say chronic, I mean chronic; she experienced pain for 16 years. She then achieved long-term relief after fasting, followed by an exclusively plant-foods diet, free of added sugar, oil, or salt.

Before then, she had tried drug after drug after drug after drug after drug—with no relief, suffering in constant pain for years. Before the fast, she started out in constant pain. Then, after the fast, the intensity of the pain was cut in half, and though she was still having daily headaches, at least there were some pain-free periods. Six months later, she tried again, and eventually her headaches became mild, lasting less than ten minutes, and infrequent. She continued that way for months and even years, as you can see below and at 1:45 in my video Fasting for Post-Traumatic Brain Injury Headache.

Now, of course, it’s hard to disentangle the effects of the fasting from the effects of the whole food, plant-based diet she remained on for those ensuing years. You’ve heard of analgesics (painkillers). Well, there are some foods that may be pro-algesic (pain-promoting), such as foods high in arachidonic acid, including meats, dairy, and eggs. So, the lowering of arachidonic acid—from which our body makes a range of pro-inflammatory compounds—may be accomplished by eating a more plant-based diet. So, maybe that contributed to the benefit in the fasting case, since many plant foods are high in anti-inflammatory components. In terms of migraine headaches, more plant foods and less animal foods may help, but you don’t know until you put it to the test.

Researchers figured a plant-based diet may offer the best of both worlds, so they designed a randomized, controlled, crossover study where those with recurrent migraines were randomized to eat a strictly plant-based diet or take a placebo pill. Then, the groups switched. During the placebo phase, half of the participants said their pain improved, and the other half said their pain remained the same or got worse. But, during the dietary phase, they almost all got better, as you can see here and at 3:11 in my video.

During that first phase, the diet group experienced significant improvements in the number of headaches, pain intensity, and days with headaches, as well as a reduction in the amount of painkillers they needed to take. In fact, it worked a little too well. Many individuals were unwilling to return to their previous diets after they completed the diet phase of the trial, thereby refusing to complete the study. Remember, the participants were supposed to go back to their regular diets and take a placebo pill, but they felt so much better on the plant-based diet that they refused. We’ve seen this with other trials, where those trying plant-based diets felt so good, they often refused to abandon them, harming the study. So, plant-based diets can sometimes work a little too well.

All my videos on fasting are available in a digital download here.

October 23, 2025

Should We Fast for IBS?

More than half of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) sufferers appear to have a form of atypical food allergy.

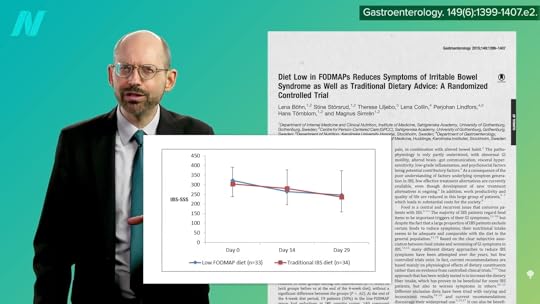

A chronic gastrointestinal disorder, irritable bowel syndrome affects about one in ten people. You may have heard about low-FODMAP diets, but they don’t appear to work any better than the standard advice to avoid things like coffee or spicy and fatty foods. In fact, you can hardly tell which is which, as shown below and at 0:27 in my video Friday Favorites: Fasting for Irritable Bowel Syndrome.

Most IBS patients, however, do seem to react to specific foods, such as eggs, wheat, dairy, or soy sauce, but when they’re tested with skin prick tests for typical food allergies, they may come up negative. We want to know what happens inside their gut when they eat those things, though, not what happens on their skin. Enter confocal laser endomicroscopy.

You can snake a microscope down the throat, into the gut, and watch in real-time as the gut wall becomes inflamed and leaky after foods are dripped in. Isn’t that fascinating? You can actually see cracks forming within minutes, as shown below and at 1:03 in my video. This had never been tested on a large group of IBS patients, though, until now.

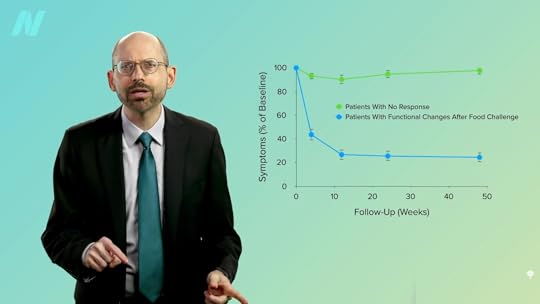

Using this new technology, researchers found that more than half of IBS sufferers have this kind of reaction to various foods—“an atypical food allergy” that flies under the radar of traditional allergy tests. As you can see below and at 1:28 in my video, when you exclude those foods from the diet, there is a significant alleviation of symptoms.

However, outside a research setting, there’s no way to know which foods are the culprit without trying an exclusion diet, and there’s no greater exclusion diet than excluding everything. A 25-year-old woman had complained of abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea for a year, and drugs didn’t seem to help. But, after fasting for ten days, her symptoms improved considerably and appeared to stay that way at least 18 months later. It wasn’t just subjective improvement either. Biopsies were taken that showed the inflammation had gone down, her bowel irritability was measured directly, and expanding balloons and electrodes were inserted in her rectum to measure changes in her sensitivity to pressure and electrical stimulation. Fasting seemed to reboot her gut in a way, but just because it worked for her doesn’t mean it works for others. Case reports are most useful when they inspire researchers to put them to the test.

“Despite research efforts to develop a cure for IBS, medical treatment for this condition is still unsatisfactory.” We can try to suppress the symptoms with drugs, but what do we do when even that doesn’t work? In a study of 84 IBS patients, 58 of whom failed basic treatment (consisting of pharmacotherapy and brief psychotherapy), 36 of the 58 who were still suffering underwent ten days of fasting, whereas the other 22 stuck with the basic treatment. The findings? Those in the fasting group experienced significant improvements in abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, loss of appetite, nausea, anxiety, and interference with life in general, which were significantly better than those of the control group. The researchers concluded that fasting therapy “could be useful for treating moderate to severe patients with IBS.”

Unfortunately, patient allocation was neither blinded nor randomized in the study, so the comparison to the control group doesn’t mean much. They were also given vitamins B1 and C via IV, which seems typical of Japanese fasting trials, even though one would not expect vitamin-deficiency syndromes—beriberi or scurvy—to present within just ten days of fasting. The study participants were also isolated; might that make the psychotherapy work better? It’s hard to tease out just the fasting effects.

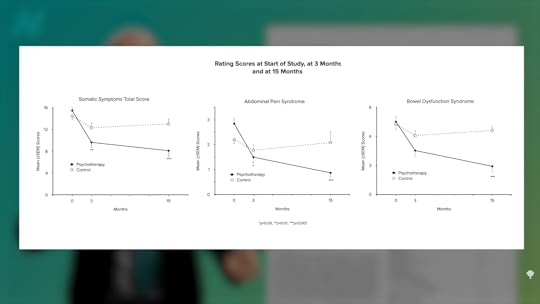

Psychotherapy alone can provide lasting benefits. Researchers randomized 101 outpatients with irritable bowel syndrome to medical treatment or medical treatment with three months of psychotherapy. After three months, the psychotherapy group did better, and the difference was even more pronounced a year later, a year after the psychotherapy ended. Better at three months, and even better at 15 months, as you can see here and at 3:58 in my video.

Psychological approaches appear to work about as well as antidepressant drugs for IBS, but the placebo response for IBS is on the order of 40%, whether psychological interventions, drugs, or alternative medicine approaches. So, doing essentially nothing—taking a sugar pill—improves symptoms 40% of the time. In that case, I figure one might as well choose a therapy that’s cheap, safe, simple, and free of side effects, which extended fasting is most certainly not. But, if all else fails, it may be worth exploring fasting under close physician supervision.

All my fasting videos are available in a digital download here.

Check the videos on the topic that are already on the site here.

For more on IBS, see related posts below.

October 21, 2025

Might Meat Trigger Parkinson’s Disease?

What does the gut have to do with developing Parkinson’s disease?

Parkinson’s disease is an ever-worsening neurodegenerative disorder that results in death and affects about 1 in 50 people as they get older. A small minority of cases are genetic, running in families, but 85% to 90% of cases are sporadic, meaning they seem to pop up out of nowhere. Parkinson’s is caused by the death of a certain kind of nerve cell in the brain. Once about 70% of them are gone, the symptoms start. What kills off those cells? It still isn’t completely clear, but the abnormal clumping of a protein called alpha-synuclein or α-synuclein is thought to be involved. Why? Researchers injected blended Parkinson’s brains into the heads of rats and monkeys, and Parkinson’s pathology and symptoms were induced. It can even happen when injecting just the pure, clumped α-synuclein strands themselves. How, though, do these clumps naturally end up in the brain?

As I discuss in my video The Role Meat May Play in Triggering Parkinson’s Disease, it all seems to start in the gut. The part of the brain where the pathology often first appears is directly connected to the gut, and we have direct evidence of the spread of Parkinson’s pathology from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to the brain: α-synuclein from brains of Parkinson’s patients is taken up in the gut wall and creeps up the vagal nerves from the gut into the brain—at least that was the case in rats. If only we could go back and look at people’s colons before they got Parkinson’s. Indeed, we can. Old colon biopsies from people who would later develop Parkinson’s were dredged up, and, years before symptoms arose, you could see the α-synuclein in their gut.

Research supported by the Michael J. Fox Foundation has found that you can reliably distinguish the colons of patients from controls by the presence of this Parkinson’s protein lodged in the gut wall. But how did it get there in the first place? Are “vertebrate food products…a potential source of prion-like α-synuclein”? Indeed, nearly all the animals with backbones that we consume—cows, chickens, pigs, and fish—express the protein α-synuclein. So, when we eat common meat products, when we eat skeletal muscle, we’re eating nerves, blood cells, and the muscle cells themselves. Every pound of meat contains, on average, half a teaspoon of blood, and that alone could be an α-synuclein source to potentially trigger a clumping cascade of our own α-synuclein in the gut. Though “it may seem intuitive that dietary α-synuclein could seed aggregation in the gut,” this kind of buildup, what evidence do we have that it’s actually happening?

We have some pretty interesting data. There’s a surgical procedure called a vagotomy, in which the big nerve that goes from our gut to our brain—the vagus nerve—is cut as an old-timey treatment for stomach ulcers. Would cutting communication between the gut and the brain reduce Parkinson’s risk? Apparently so, suggesting that the gut to brain’s vagal nerve may be critically involved in the development of Parkinson’s disease.

Of course, “many people regularly consume meat and dairy products, but only a small fraction of the general population will develop PD,” Parkinson’s disease. So, there must be other factors at play that “may provide an opportunity for unwanted dietary α-synuclein to enter the host, and initiate disease.” For example, our gut becomes leakier as we age, so might that play a role? What else makes our gut leaky? “Dietary fiber deprivation has also been shown to degrade the intestinal barrier and enhance pathogen entry.” So, this raises “possibilities for food-based therapies.”

Parkinson’s patients have significantly less Prevotella in their gut, a friendly fiber-eating flora that bolsters our intestinal barrier function. So, low levels of Prevotella are linked to a leaky gut, which has been linked to intestinal α-synuclein deposition, but fiber-rich foods may bring Prevotella levels back up. “Therefore, it is possible that by adopting a plant-based diet, in addition to the beneficial effects of phytonutrients, increasing overall fiber intake may modify gut microbiota and gut permeability [leakiness] in beneficial ways for people with PD.”

So, does a vegan diet—one with lots of fiber and no meat—reduce risk for Parkinson’s? Parkinson’s “appears to be rare in quasi-vegan cultures,” with rates that are about five times lower in rural sub-Saharan Africa, for instance. All this time, we were thinking the benefits seen for Parkinson’s from plant-based diets were due to the antioxidants and anti-inflammatory nature of the animal-free diets, but maybe it’s also due to the increased intestinal exposure to fiber and decreased intestinal exposure to ingested nerves, muscles, and blood.

Wasn’t that fascinating? For more on Parkinson’s, see the related posts below.