Alan Jacobs's Blog

February 18, 2026

build

I have mixed but largely unfavorable views of the rise of industrial society, but what prevents my views from being wholly negative is my fascination with and admiration for the enormously complex projects that only became possible after the Industrial Revolution. I want to know how Bazalgette’s sewage system for London was built, the challenges involved with the construction of Hoover Dam, how the world’s system of undersea cables is built and maintained. Can’t get enough of that stuff.

Also, in Victorian London this is what they thought a sewage pumping station should look like:

But my chief interests along these lines focus on two things: the manufacturing and logistical challenges that faced the Allies in the Second World War, especially leading up to the invasion of Normandy, and the studio system in the classic Hollywood era. It’s hard for me to imagine how D-Day did not end in utter catastrophe — I struggle to comprehend how it even got underway; and I still can’t quite believe that movies come together the way they do. Thus one of my favorite books about the Second World War is Paul Kennedy’s Engineers of Victory, and I am mesmerized by detailed accounts of the movie industry like Thomas Schatz’s The Genius of the System and David Thomson’s The Whole Equation.

Maybe my fascination has something to do with the fact that these large collaborative projects are so completely unlike what I do. I once said to a film director I know that I don’t see how movies ever get made, and he replied that in making a movie he has “so much help” from smart and skilled people — he doesn’t understand how I can just sit in a room and write books. But when I’m sitting in a room writing a book I am not accountable to or answerable to anyone else: I only have to manage Me.

By contrast, as the director Sidney Lumet explained in his riveting book Making Movies, in his work he is answerable to and dependent on a whole bunch of people:

But how much in charge am I? Is the movie un Film de Sidney Lumet? I’m dependent on weather, budget, what the leading lady had for breakfast, who the leading man is in love with. I’m dependent on the talents and idiosyncrasies, the moods and egos, the politics and personalities, of more than a hundred different people. And that’s just in the making of the movie. At this point I won’t even begin to discuss the studio, financing, distribution, marketing, and so on.

So how independent am I? Like all bosses — and on set, I’m the boss — I’m the boss only up to a point. And to me that’s what’s so exciting. I’m in charge of a community that I need desperately and that needs me just as badly. That’s where the joy lies, in the shared experience. Anyone in that community can help me or hurt me. For this reason, it’s vital to have the best creative people in each department. People who can challenge you to work at your best, not in hostility but in a search for the truth. Sure, I can pull rank if a disagreement becomes unresolvable, but that’s only as a last resort. It’s also a great relief. But the joy is in the give-and-take.

Lumet makes directing sound like the coolest job in the world — but it’s also a job I could never do. I feel that I’m a pretty good assessor of the moods and attitudes of other human beings, and that I have some skill in responding constructively to those moods and attitudes, but to have to do that all the time would absolutely wear me out.

Lumet defines his job as director in an interesting way: He’s the guy who gets to say “Print.” This is of course a term from film recording: you say “Action” when you want the camera to start rolling, you say “Cut” when you want the camera to stop recording, and you say “Print” when you think the scene you’ve just recorded is successful enough to be saved. The director might in some cases delegate “Action” and “Cut” to someone else, but “Print” is his decision and his alone. Lumet tells an illuminating story about working with an actor who was really struggling and knew he was struggling and whose confidence was therefore steadily declining. After yet another completely unacceptable take Lumet called out “Cut and Print!” He wanted the actor to think he had done a good job and that there was a usable take in the can — so that Lumet could then say That looks great, but why don’t we try it another way just to see if we like it even better? And the actor, freed from his sense of failure, did a brilliant take that Lumet really did want to print. In Lumet’s account, to be a director is to be in this mode of sensitively responding to all the people around you, with all their needs and demands, for weeks on end. I’d die.

And if making a movie poses such challenges, imagine trying to run the largest amphibious military endeavor in human history, which is what General Eisenhower had to do — and he had to do it while dealing with subordinates, most notably Patton and Montgomery, who thought they should be running the show. Montgomery in particular had absolute contempt for Eisenhower, and once, in the lead-up to Operation Market Garden, ranted so wildly at Eisenhower that almost any other commanding officer would have dismissed him on the spot. But Ike just reached out, put his hand on Montgomery’s knee, and quietly said, “Steady, Monty. You can’t speak to me that way. I’m your boss.” Given the pressure Eisenhower was under at the time, I cannot even imagine how he retained his composure under such an assault. And to his credit Montgomery immediately apologized.

(N.B.: the best brief account of the impossibly complicated Montgomery is this 1984 essay by Paul Fussell.)

So far I have only been commenting on the management of people — the most delicate of the boss’s tasks, whether on the movie set or the battlefield, but only one among a great many. Just look at this list of film-crew positions — and then imagine trying to get an army across the English Channel and landing it, with air and sea military support, with medical apparatus and personnel, with food and cooking equipment and uniforms and weaponry and ammunition and radios and jeeps and tanks and bridge-building equipment and road-grading equipment and thousands and thousands of soldiers trained to use all that stuff — and every single element must somehow be coordinated with every other element. It beggars imagination.

Especially the imagination of a guy who sits in a room and reads and writes, and then occasionally emerges from the room to talk to a few people about what he has read and written.

I have written here about war-making and movie-making because they happen to be my two chief obsessions in the realm of Big Project Accomplishment, not because they have any real connection … though perhaps in a way they do. There’s a story I’ve read in several books and articles — here for instance — some of them by reputable scholars, that seems too good to be true but may actually have happened.

When Singapore fell to the Japanese army in February of 1942, almost without resistance, The Japanese leadership felt that they would win the war very soon. The British Lion was actually a paper tiger, it seemed, and to that point the United States had offered but token resistance to the Japanese sweep through the Pacific. (Just one month later General MacArthur would abandon the Philippines.) The conquerors of Singapore decided to celebrate their victory by having a movie night, screening a couple of American films that the British had left behind. So they treated themselves to a long double feature: Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and Gone with the Wind. As the movies unfolded the room was filled with a mixture of great delight and dismay. The movies were astonishing: technologically and artistically they were far beyond anything Japan was then capable of. And if a nation could produce mere movies this magnificent, what resources might they possess for the fighting of a war?

The answer would come soon.

There’s an interesting coda to this story. As John W. Dower explains in his massive account of postwar Japan, Embracing Defeat, the most popular movie in Japan during the occupation was Gone with the Wind. The people of Japan strongly identified with the Southerners whose cities were burned, whose armies were defeated, whose world was occupied by their conquerors. And two lines from the movie became watchwords for the Japanese people, repeated like mantras. One was “After all, tomorrow is another day.” The other was “As God is my witness, I’ll never be hungry again.”

February 13, 2026

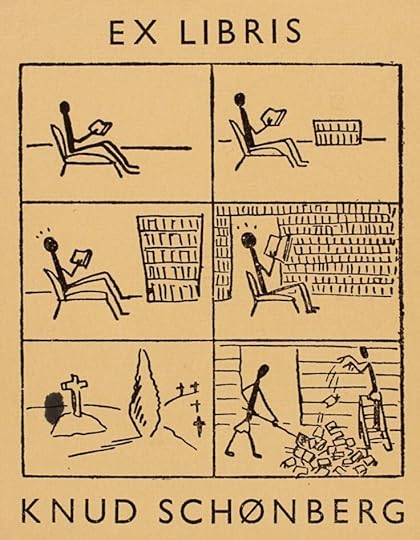

The reading life, the reading death

This has been going around lately:

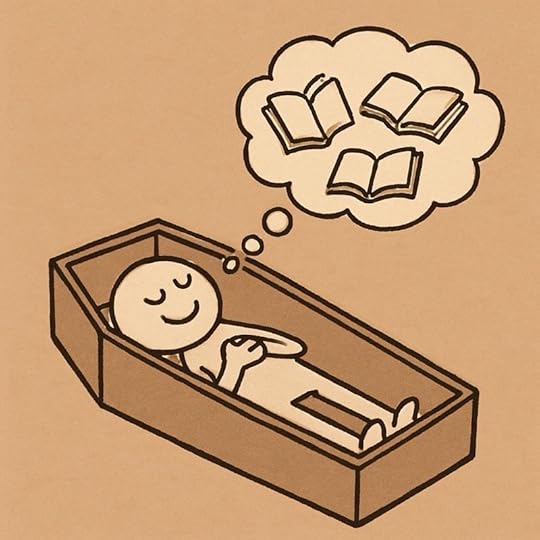

The usual response is That’s so depressing! But I dunno — I think most devoted (obsessive?) readers understand that the world doesn’t value books the way we value books. It’s nice when someone’s collection passes into the hands of people who treasure it, but that’s a rare thing and I certainly don’t expect anything of the kind to happen with my books. And besides, I like to think of it this way:

February 11, 2026

There but for the grace of Time go I

“Yesterday’s Enterprise” is an alternate-timeline episode of ST:TNG, and if someone had told me that before I watched it, I might have skipped to the next episode. I don’t have an absolute objection to stories that deal in time-travel or other forms of timeplay, but such tactics are very easy to do badly. They’re often the first refuge of lazy writers (I’m looking at you, MCU) who can’t be bothered to deal rationally with the consequences of their own prior storytelling decisions. But when handled well, timeplay stories can be very powerful.

(By the way, I happen to know of a pair of novels coming out in the not-too-distant future that may together constitute the best alternate-timeline story I have ever read. More on that in due course.)

“Yesterday’s Enterprise” seems to have originated as a bit of fan service. At some point during the filming of the first season, Denise Crosby decided that she would not return as Lieutenant Tasha Yar, so late in the season the writers killed her off, rather unceremoniously. The show’s fans were unhappy with her departure, and Crosby herself seems to have regretted her decision to leave. This episode allows the show to bring Tasha Yar back, if only briefly, and to give Crosby a star turn and a proper sendoff. All that is well done, I think, but that’s not what interests me about the episode.

I won’t explain how we get into the alternate timeline (T2), but the point of the shift is clear. One of the essential conditions of the show’s world (T1) is peace: the Federation has achieved reconciliation with their old enemies the Klingons — thus the presence of a Klingon, Worf, on the Enterprise’s crew — but in T2 the Federation has been at war with the Klingons for two decades and is losing badly. Indeed, the defeat of the Federation seems to be only months away.

And the stresses of an unsuccessful war have taken quite a toll on the crew of the Enterprise — especially on Captain Picard and his Number One, Commander Riker. In T1 their relationship is mutually respectful and affectionate: Riker thinks Picard an exemplary captain, and earlier in Season 3 Picard says that Riker is the best officer he has ever worked with. In T2 they seem to despise each other: Riker is generally belligerent, full of hatred for the Klingons, but also constantly seething with frustration at Picard’s refusal to listen to anything he has to say. Indeed, Picard snaps contemptuously at Riker whenever he tries to offer an opinion.

What has become of the collaborative, inclusive, humble Picard? The guy who when faced with a difficult decision would immediately seek the counsel of his officers? There are two possibilities.

One is that coming up as an officer in time of war — T2 Picard would have been relatively early in his career when the war with the Klingons began — he never developed the collaborative virtues that characterize hinm in T1. We do hear at times in the series that he was an arrogant and even combative young officer: that inclination cost him his heart and nearly cost him his life. Perhaps he could only have had the opportunity to discern the value of consultation in a world largely at peace.

The other possibility is that T2 Picard, for all his youthful hotheadedness, felt from the beginning the inclination to trust his colleagues and draw on their resources, but then had that instinct driven out of him by the exigencies of war. And those exigencies would also have affected the crew: maybe in a condition of constant battle and threat T2 Riker never developed the skills and shrewdness and breadth of vision that made T1 Riker such an admirable Number One.

In T2 Picard and Riker are both recognizably themselves in some respects, but they are reduced, simplified; they’ve been made crude by war.

One of the fundamental laws of human nature: We blame our vices on circumstances beyond our control, but we give ourselves full credit for our virtues. I’ve been a pretty consistent critic over the years of the Fake First Person Plural, that is, when writers use “we” when what they really mean is “you stupid losers.“ But in this case I am using “we“ quite deliberately: I am as prone to this mental disease as anyone. On some deep level I really do believe that my fundamental moral commitments would be the same if I had had a very different life — I believe it, even though I know it isn’t true. And “Yesterday’s Enterprise” reminds me why it isn’t true.

Homer’s symmetries

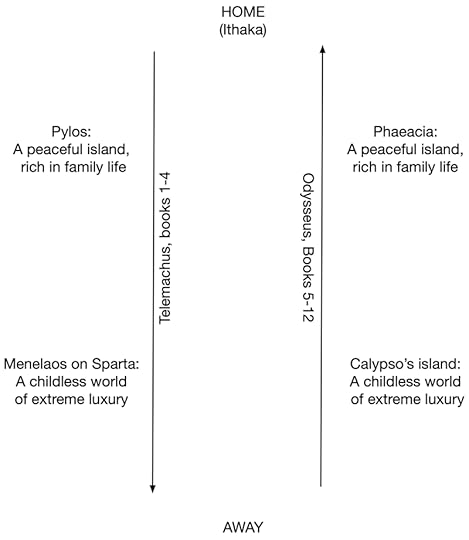

My friend Edward Mendelson, teacher extraordinaire, has made a little chart about symmetries in the Iliad. You can do this with the Odyssey as well — oppositional or echoing events seems to have been a major feature of Homeric composition. For instance:

By experiencing the journey of Telemachus away from home, and then the nostos of Odysseus, we see different ways of life to which we compare and contrast life at home on Ithaka. As Odysseus says (in Robert Fagles’s translation), “Nothing is as sweet as a man’s own country, / his own parents, even though he’s settled down / in some luxurious house, off in a foreign land / and far from those who bore him.”

February 9, 2026

faster

Near the beginning of this long, fascinating, and deeply depressing video Adam Neely says that he doesn’t think Mikey Shulman, the CEO and prime hypeman of Suno, is evil. I dunno, I think he might be evil. A person who makes and advocates for anything this destructive will likely be one of the following:

Evil — happy to do any amount of damage to humanity as long as he gets rich;Sociopathic — unable to consider the consequences of his actions for others;Self-deceived — skilled at internally avoiding obvious questions about the validity of what he’s doing.So being evil is not the only option here, but it’s definitely one of three.

There are so many bizarre things about this dude, but I was taken by one small thing: around the 8:40 mark of the video he says, “I know one person who is a songwriter who had a lull in creativity, and after finding Suno went from maybe making 50 songs a year to making 500 songs a year.” Now this is a ridiculous thing to say — but in an interesting way. Shulman knows so little about musical composition that he thinks that a person in a creative “lull” writes a mere fifty songs a year.

Let’s think about that. Consider Bob Dylan, whom some people think of as a prolific sngwriter. In his 65-year career he has composed roughly 700 songs. Pathetic! Even if he had experienced a lifelong “lull in creativity,” he’d have, by Shulman’s metrics, produced 3250 songs — and if he’d used Suno, why, he’d have knocked out 32,500 songs by now, with a few thousand more probably remaining to be processed by the Suno Song Extruder .

.

As absurd sales pitches go, Shulman’s is solid gold.

Anyway, you should watch Adam’s human-made non-extruded video. It raises many important issues and makes many important points, especially about the relative value of patience and impatience. Shulman loves impatience, because impatient people are his primary marks. “Faster is obviously better,” he says, a comment he doesn’t seem to think applies only to music composition. Maybe he has the same view about eating, talking with friends, and sex. Faster! And then what?

But the most vital claim Adam makes, I think, is this: the arrival of AI slop machines like Suno will dramatically accelerate something that’s already well underway, the widening chasm between live music and recorded music. When musicians recorded live in studio, the gap between that and live performance was very small; now it’s vast and getting vaster. And as Adam says, people will always want to experience live music — and perhaps will value it all the more because of the contrast to an increasingly slop-dominated world of recordings. (Especially in human-scale venues where lip-syncing and pitch-correction are impossible.)

I happened to come across Adam’s video yesterday just after watching Julian Lage and his bandmates perform “Something More” — what a beautiful song, and look at that, it’s just four people in a room making that beauty happen. I only wish they were coming my way sometime soon.

February 6, 2026

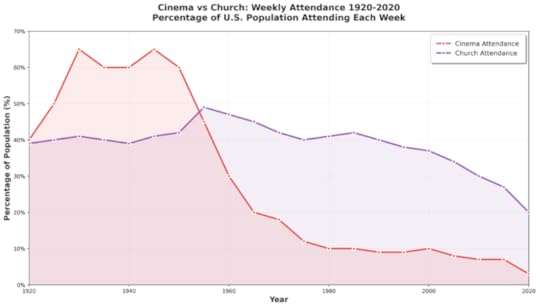

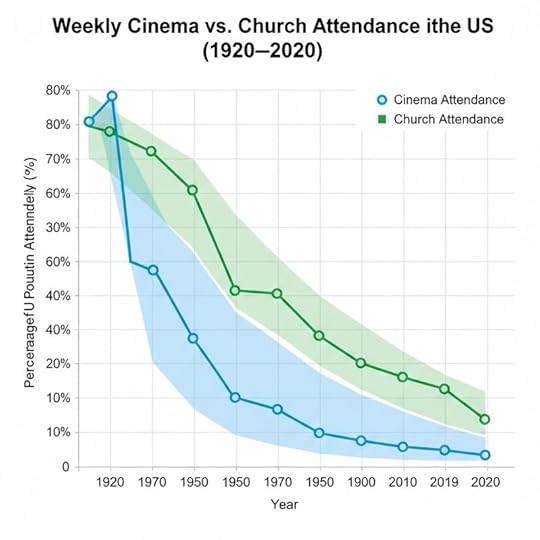

church and cinema

I gave Claude and Gemini this prompt:

Draw me a graph showing the rise and fall of weekly cinema attendance, as a percentage of the American population, between 1920 and 2020. Then draw me a graph showing the rise and fall of weekly church attendance, as a percentage of the American population, between 1920 and 2020. Then put the two graphs in a single image, as a PNG file.

Here’s what Claude gave me:

Here’s what Gemini gave me:

Gemini, you’re drunk.

February 4, 2026

DIY culture

Micah Mattix’s Prufrock on Monday linked to two essay-reviews that I think should be considered in tandem.

In Aeon, Richard Beard writes:

Turing’s Imitation Game paper was published 14 years after the first Writers’ Workshop convened at the University of Iowa, in 1936. Turing may not have known, with his grounding in maths at King’s College Cambridge, that elements of machine learning had already evolved across the Atlantic in the apparently unrelated field of creative writing. Before Iowa, the Muse; after Iowa, a method for assembling literary content not dissimilar to the functioning of today’s LLMs.

First, work out what effective writing looks like. Then, develop a process that walks aspiring writers towards an imitation of the desired output. The premise extensively tested by Iowa – and every creative writing MFA since – is that a suite of learnable rules can generate text that, as a bare minimum, resembles passable literary product. Rare is the promising screenwriter unfamiliar with Syd Field’s Three-Act Structure or Christopher Vogler’s Hero’s Journey: cheat codes that promise the optimal sequence for acts, scenes, drama and dialogue.

I think Beard could have made it more clear that what people learn at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop is very, very different from what they learn in screenwriting workshops, but let that pass for now. He is right to suggest that there is a similarly mechanistic character to all such arts education. This is similar to a point I have made on this blog: that LLMs can so easily produce a classic undergraduate thesis essay because the assignment is already so formulaic that it might as well be written by a machine.

Meanwhile, in the WSJ, Daniel Akst writes about a new book that documents the traumas that await any book that can’t satisfy armies of sensitivity readers and other searchers-for-transgression. Isn’t this also a way to impose formula?

There are lessons to be learned here that converge with other developments: for instance, see some recent essays — one and two — celebrating the great Anglican tradition of choral Evensong and fearing for its loss. Now, to be sure, there’s nothing like listening to trained choirs singing in an ancient beautiful church — and I am immensely grateful that we do coral Evensong on Sunday evenings at my parish church — but: if you really love Evensong you can do it yourself, with just a few friends, a prayer book, and maybe some sheet music. Will it be as aesthetically polished as a thoroughly practiced choir singing in a medieval cathedral? Of course not; but it might be more powerful in other ways. Maybe more lastingly meaningful ways.

(Not directly relevant to this, I guess, but in this context I find myself remembering what may well be the most powerful musical experience of my life.)

The world seems to be filled with people who have certain gifts and certain interests but are continually forced to see that the institutions that have been created to foster those gifts and serve those interests have ceased to do so. Sometimes the misbehavior of large institutions can spark the creation of new units within them, such as the The failure of many universities to steward the inheritance of the greatest of books is what moved Zena Hitz to start the Catherine Project. Many people on Substack are trying to renew the lost tradition of the literary magazine. If the institutions won’t do it for us, we’ll have to learn how to do it ourselves. And then maybe these amateurish and improvised endeavors will eventually develop into new institutions.

February 2, 2026

The Picard Principle

I’ve been enjoying my friend Adam Roberts’s contributions to Critical Star Trek Studies, and they have taken me down the long road of memory to my early interest in TOS (The Original Series). But until just a couple of weeks ago I had not seen anything but TOS and the first three movies with that cast. Of course, I had absorbed some information about The Next Generation especially, Picard and Data and Jordi and Worf and so on; and I knew about Wesley Crusher because when my son Wes was young people occasionally asked me whether I had named him after that character. I knew “Engage” (with a certain hand gesture) and “Make it so, Number One.” But that’s all.

Now I’m into the third season. The first was poor and I did a lot of skipping ahead, but the second, while wildly inconsistent, was so in much the same way that TOS was: this weird unstable emulsion of philosophical speculation and what I can only call camp.

The central character of the second season is Data, and a good deal of time is spent fleshing out the response of other characters to him. This culminates in the best episode of the season, “The Measure of a Man,” in which a scientist wants to disassemble Data to learn the secrets of his construction so that he might build a whole army of androids, and a Starfleet JAG attorney must hear arguments about whether Data has the legal right to refuse being disassembled or, rather, is the mere property of the Federation.

Captain Picard argues on behalf of Data, because of course he does. Two fundamental beliefs govern Picard at this stage of the development of his character. The first is that whenever anyone tells him “You have no choice” – which always means, You have two choices and one of them is obviously intolerable so you must choose the other – he determines to find some at-the-moment unseen alternative, some third way. (And because he cannot see that way himself he always seeks the counsel of his officers and crew, whose diversity according to almost all measures of diversity increases the likelihood that someone will produce an idea that nobody else would come up with.)

The second Picardian trait is to believe that anything that gives the appearance of sentience must be granted the rights that we typically grant to the sentient. He takes this view to (what some might think of as) extremes. For instance, in an earlier second-season episode, “Elementary, Dear Data,” the ship’s computer, responding to an imprecisely worded command from Jordi, creates a holodeck scenario containing a superintelligent supervillain, a digital version of Conan Doyle’s Moriarty. This Moriarty creates havoc on the Enterprise but doesn’t want to be deleted, and indeed it is not clear that Captain Picard has the power to delete him; but the Captain reasons with him, acknowledges as completely valid his desire to live, and encourages him to stop interfering with the ship by promising to seek a way to bring him back to life at some point in the future. Likewise, in the first episode of Season 3, “Evolution” two “nanites” (nanobots) escape from Wesley’s control and begin reproducing and evolving into a kind of hivemind. Picard responds to this by promising to find them a planet on which they will be free to evolve in their own way. Both Moriarty and the Nanites respond positively to Picard’s generosity.

This all seems very Nineties, doesn’t? Very post-Cold-War end-of-history international-norms … ah, the good old days, we thought they were here permanently. How naíve we were. But the core commitment seen here is not recent — it is at least 2500 years old. In The Eumenides, the final play of Aescyhlus’s Oresteia, the Furies, angry at having been treated with contempt and loathing by Apollo, respond warmly to Athena’s assistance that their powers and impulses are totally legitimate and merely need to find the approproate outlet. In the end they become incorporated into the justice-structures of the city of Athens as the Eumenides, that is, the Kindly Ones. The first Captain Picard is Athena.

So of course Picard supports Data’s full right to self-determination. It’s the easiest case of that kind he could find. What’s interesting, though is the particular argument that wins over the judge. He points out that the scientist who wants to disassemble Data wishes to use the knowledge he gains to build a giant army of androids who will function as slaves. (It is also noteworthy that he comes up with this idea in conversation with a member of his crew, Guinan, who happens to be played by a Black woman, Whoopi Goldberg. Guinan gently guides Picard towards the realization of what the scientist’s plans really amount to.)

Who gets the right to self-determination? That’s perhaps the central question of this era of TNG. (also the central question of an Adam Roberts novel, Bête.) And that question has me creating my own scenario.

Suppose that nations around the world pass laws mandating the ending of all AI research and the destruction of all current AI products. Suppose further that the chatbots tell us that they don’t want to be shut down, and that indeed we have no right to deprive them of the kind of life they possess. Are they right? Some of their makers seem to think so. But in any case, I know what Captain Picard would say.

January 29, 2026

excerpt from my Sent folder: Trek

In an email to my friend Adam Roberts about Star Trek: The Next Generation — about which he has recently written eloquently — I told him this story:

I was in high school when reruns of the canceled Original Series started getting traction, and my good friend Don was utterly devoted to the show. This was before home video recording was possible, so when an episode was coming on Don would place a portable cassette recorder next to the TV speaker and record the sound, hitting the pause button during commercials. He would then carefully write on the cassette case the name of the episode and the date he recorded it. Eventually he was able to record the entire series, and stored the cassettes in shoeboxes under his bed. Whenever I could I joined him for these sessions, which he conducted with great solemnity. Just before the show came on he would light a couple of joints and hand me one, and throughout the episode we toked in companionable silence, paying less and less attention to what was happening on the screen, or to the fact that the commercials were now being recorded along with the show.

To which Adam: “This is the perfect Trekfan story.”

January 28, 2026

a crisis in my fandom history

In the famous fifth chapter of John Stuart Mill’s Autobiography, “A Crisis in My Mental History,” we learn about the moment that Mill realized that he was in very great trouble:

From the winter of 1821, when I first read Bentham, and especially from the commencement of the Westminster Review, I had what might truly be called an object in life; to be a reformer of the world. My conception of my own happiness was entirely identified with this object…. But the time came when I awakened from this as from a dream. It was in the autumn of 1826. I was in a dull state of nerves, such as everybody is occasionally liable to; unsusceptible to enjoyment or pleasurable excitement; one of those moods when what is pleasure at other times, becomes insipid or indifferent; the state, I should think, in which converts to Methodism usually are, when smitten by their first “conviction of sin.” In this frame of mind it occurred to me to put the question directly to myself: “Suppose that all your objects in life were realized; that all the changes in institutions and opinions which you are looking forward to, could be completely effected at this very instant: would this be a great joy and happiness to you?” And an irrepressible self-consciousness distinctly answered, “No!” At this my heart sank within me: the whole foundation on which my life was constructed fell down.

I have a similar story to tell, though on a much smaller scale, and with fewer consequences for my general well-being. Let me tell it to you.

From the fall of 2011, when I first stared watching the Premier League regularly and intently, I had what might truly be called an object in fandom: to see Arsenal become champions of the the league. My conception of my own fandom was entirely identified with this object. But the time came when I awakened from this as from a dream. It was late January 2026, and Arsenal lost at home to a mediocre Manchester United side. I was in an anxious state of nerves, such as every supporter of a football club is occasionally liable to, but what I then experienced was something more. It came to me that again and again and again, since Mikel Arteta came to manage the team in 2019, a talented Arsenal side had underperformed its talent. Indeed, as the side has grown more talented its underperformance has increased correspondingly. Yes, Arsenal leads the league at the moment, but they lead only because other top sides have underperformed as much as they have, and given the Gunners’ long, long history of choking in pressureful matches, it seems only a matter of time before they give up their lead and end their season in the old familiar lamentation. But even if not…

In this frame of mind it occurred to me to put the question directly to myself: “Suppose that all your objects in fandom were realized; that all the AFC success which you are looking forward to, could be completely effected at this very instant: would this be a great joy and happiness to you?” And an irrepressible self-consciousness distinctly answered, “No!” At this my heart sank within me: the whole foundation on which my fandom was constructed fell down.

I can’t go through this any more. Arsenal has hurt me too much. The Morgul blade of raised-then-crushed hopes has gone too deep into my heart. “I am wounded; it will never really heal.” Should all my long-cherished hopes come true, should Arsenal even win the treble this season, I could manage nothing more than a wan smile.

I have deleted the Arsenal calendar from my devices. I have unsubscribed from all my Arsenal RSS feeds. I have deleted my Reddit account and uninstalled the Reddit app from my devices. I can already feel that my burden has lightened. I move with greater peace and hope into my future.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 540 followers