Salman Rashid's Blog

June 4, 2023

REDISCOVERING THE GRAND TRUNK ROAD

Yet, Suri has stayed long in our collective memories as the builder of the Grand Trunk Road, a legacy bequeathed, in part, to present-day Pakistan.

But was it really so?

It took travel writer Salman Rashid years of research, countless cross-country treks, rides on rickety two- and four-wheelers, frog-jumping the parapets of numerous forts, gingerly stepping down the decaying brick steps of ancient baolies [water reservoirs], conversations with both the simplest of minds and internationally certified authorities and generous dollops of his one-of-a-kind humorous and satirical asides to make short — read: long — work of the well-kept secret that the Grand Trunk Road is. Simply put, it has far more to it than meets the eye.

The road’s Pakistani trajectory begins from the town of Landi Kotal at the rugged edges of the Khyber Pass, in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). Shady trees line either side of the ancient route that flows towards Wagah near Lahore, before crossing into India and ending in southernmost Bangladesh. On the way, it has touched many settlements, been ground for historic monuments and peace treaties and branched off at the whims of various invaders and kings.

All that the road has weathered in its centuries of existence — facts and fables, history and folklore, cultural ethos and a landscape painted, in part, by deliberate intent — makes for an amazing conglomerate of knowledge that has been glossed over by crediting its construction to Sher Shah Suri.

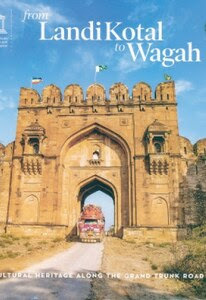

Hence, Rashid’s latest travel treatise, From Landi Kotal to Wagah: Cultural Heritage Along the Grand Trunk Road. This absorbing, beautifully produced book is testimony to the fact that the Grand Trunk Road — about which much has already been written — was waiting to be rediscovered and recorded from an angle other writers have failed to highlight.

This angle is essentially that, although Suri probably did build some segments of the road, the numerous landmarks along its Pakistani length prove the presence, passing or settlement of travellers, preachers and warriors from as early as the fourth century.

Rashid writes a zesty story of this extensively traversed highway’s origins, beginning from the fourth century in the time of the Mauryans, to the sixth century when Cyrus, king of the Achaemenid empire, annexed modern-day Pakistan. The author then takes us through the Buddhist, Mughal, Sikh and British eras to bring readers to the status of the road in the present day.

Rashid’s findings draw a line between fact and fiction, verifying historical record and simultaneously debunking myths that have come to be over the years, either in ignorance or purposeful design to benefit contemporary needs and populations.

For instance, he writes of a small fortification in Torkham, KP, that shows all the signs of having been constructed in the early 20th century, most likely by the British. However, his local guide refuses to venture inside because he has grown up believing that it was actually the site of Timur’s gallows, where the Mongol conqueror had had many a dissident hanged.

Hardly anywhere else might we have read of the second-century warrior king Kanishka following a darting rabbit along a swamp, only to meet a local shepherd who told him that Buddha had prophesied that a victorious ruler would raise a stupa in that particular location to house the largest portions of the sage’s earthly remains. Eager to prove himself the ‘one’, Kanishka promptly had a stupa built and planted a peepal tree, marking a site to where every Buddhist pilgrim gravitated for 400 years.

By referencing records such as the Tuzk-i-Babari — also known as Babarnama or History of Babar — and Tuzk-i-Jahangiri [History of Jahangir] as well as a good deal of investigative good sense, Rashid creates a marvellous balance between historical accuracy and folklore. The local populace would even today rely religiously on hearsay — the authors of such yarns might never even have been near any source material — but any attempt to counter them will result in one being “drummed out of town.” Such situations give Rashid’s book a wry humour to which only he can do full justice.

Rashid addresses the Grand Trunk Road — originally called the Rajapatha [Royal Highway] and, in the area that is now Pakistan, the Utra Rajapatha [Northern Royal Highway] — as a living entity that is at times vibrant, at other instances bloodthirsty and, at yet other moments, a detour for specific political, social or religious invasions. Sometimes it is buried in anonymity, yet it continues to be very much part of an important line of communication down centuries of political, religious and social invasions.

The rich, historical story of the grandest highway in the Subcontinent criss-crosses a spread of beautiful geography and landscapes of wondrous culture, heritage, fable and folklore that is much deeper and more intriguing than its kilometres of surface.

We see the crumbling kos minars [milestones], which once numbered in the hundreds along the length of the road, but now only two survive in the Pakistani section. Also surviving in various states of despairing disrepair are the tomb of one Lala Rukh — purportedly either the daughter or granddaughter of Mughal emperor Akbar — and the baradari [garden] of Behram Khan, son of the Pakhtun poet and warrior Khushal Khan Khattak.

On this excellent adventure ride into antiquity, we also read about the Macedonian king Alexander’s trek through what is now Pakistan and stories of princesses who sponsored great architectural projects. In his trademark humorous style, Rashid comments that it seems the British government’s decision to lay a railway track between the tombs of the Mughal emperor Jahangir and his beloved wife Noor Jahan was intended to “accentuate the intellectual difference between the two” because Jahangir was “scarcely worthy” of the lady who “towered” above him.

This makes the opinion of the octogenarian village matriarch, with which Rashid begins his book, all the more poignant: “Roads make all the difference to women. They have little meaning for men who can ride horses that we women can’t.”

Yesterday, today and tomorrow. From Landi Kotal to Wagah is quite the stylistic tapestry of contemporary comment and the mystique of antiquity. And Rashid’s technique of breaking up scholastic historic content with first-person anecdotes adds much flavour to what may, at times, be a somewhat taxing read for those who might pick it up for entertainment purposes only.

From Landi Kotal to Wagah: Cultural Heritage Along the Grand Trunk Road

By Salman Rashid

Sange-e-Meel, Lahore

ISBN: 978-9231003875

250pp.

The reviewer is a freelance journalist, translator and creative content/ report writer who has taught in the Lums Lifetime programme. She tweets @daudnyla

February 20, 2022

Happy Birthday to Me

January 31, 2022

The Fort of Jewels

The Mianwali district gazetteer of 1915 noted it was known as Maniot, corrupted from Manikot, signifying ‘Fort of Jewels’. This, the gazetteer recorded, was because the ‘Kalabagh diamonds’ were found here. Whatever these diamonds were, no one could tell me then nor on a recent visit.

What did exist on the hilltop was a pair of ruinous Hindu temples. The larger of the two was leaning about 15 degrees out of its true axis and it was a miracle it was still standing. In fact, even the author of the gazetteer had noted its ‘almost tottering’ state.

All those years ago, I had feared that, even if diamond hunters were not to undermine the building, Nature certainly would do the deed. That the building is still there testifies to the building skill of ancient engineers and stone masons.

Closer examination of the site shows that the surviving temples that face the rising sun did not stand alone. They were a part of a complex of several similar buildings. The remains of at least two can be seen immediately below the leaning building, and another to the north. The hill being clayey and porous and susceptible to erosion, it appears that these buildings simply subsided with the ground giving way beneath them.

On the crest of the hill is another similar temple, set on a high stone plinth. It faces west and is in an advanced stage of decay. It has lost its shikhara [steeple], whose debris lies all around the building. Its entrance, choked with thorny mesquite, is impossible to get through. The hilltop around the temples is liberally strewn with pottery shards, evidence that it was inhabited for a considerable period.

In a line across the hill region of Sindh Sagar Doab, between the rivers Jhelum and the Indus, there stretches a string of ancient temples, dating to the time of the Hindu Shahya (8th -11th century CE) rulers of Kashmir. All of these temples date to the latter Hindu Shahya period.

Beyond the Indus, there are two more sites of the same period. One, not very far west of Maniot, had two almost ruined structures in 1985. The other, Bilot, in Dera Ismail Khan district is the most magnificent, with eight beautifully ornate structures enclosed in a massive defensive wall.

In all, beginning with Nandna overlooking the Jhelum floodplain, there are remains at Ketas, but brutally vandalised by ‘conservators’ who knew nothing of what they were doing. Then there is nearby Malot with its stark Greek influence and Sassi da Kallara near Talagang. The latter is unique among the other stone edifices, for being a baked-brick structure. And there are the two at Amb village, one of which — at nearly 40m in height — is the tallest among these structures. Together with Maniot and the sites mentioned on the far side of the Indus, they make seven temple complexes.

The singular characteristic of all these temples is the rather busy ornamentation on their exteriors. It is as if the stone became putty in the hands of the masons. According to Kamil Khan Mumtaz, the well-known architect and historian, most of the motifs — including the trefoil arch of the entrance — derive from earlier Buddhist emblems. There is also a plethora of beautiful rosettes and motifs of the amalaki (Emblika officinalis), a bitter fruit native to the Subcontinent and much used in Ayurvedic medicine.

The writer of the gazetteer says that local Hindus revered these temples as the Samadhi (where Hindu and Sikh ashes are deposited after cremation) of a fakir known either as Naga Arjun or Naga Uddhar. Ancient coins are also said to have been found on the hill, but the writer does not mention if he had them deciphered. Since it had rained a day before my recent visit and because coins are mostly uncovered after a wet period, I scoured the ground, but found nothing.

Going by the template followed in the ornamentation of all these temples, the elevation was replicated in exact miniature on the three sides of the building. Therefore, even where the temple is completely ruinous, as in the case of Nandna, or has lost its steeple, as in Sassi da Kallara and Malot, one can see from the replication what the whole building would have once looked like. At Maniot, the departure from the norm is that the steeples in both surviving temples were stubby, ending in large amalaki toppings.

There seems to have been no scientific investigation at Maniot, but it should be safe to say that this complex was built in about the latter part of the ninth century. That was a hundred years before the Turks began their periodic plundering raids, when this site might have fallen into disuse for some time.

But as Manto said, religion lives in the soul and does not die with all the killing one might gloat over as having destroyed a belief; faith lives on. And here too the ancient religion lived on.

The only change that came over these temples was that, instead of the worship of Shiva and Vishnu, they became sacred to a local fakir who might have lived several hundred years after their walls first resonated to the sounds of recited scripture.

But then 74 years is a long time, time enough for three generations who have never seen a Hindu in Mari to forget what once was. Today, locals only refer to the ancient worship site as ‘place of the kafirs’.

The temple that has been leaning on its side for a long time might yet have some hope. Khurram Shehzad, the deputy commissioner at Mianwali, has asked for a study to be made if the angle can be corrected without damaging the structure. If not that, there might be something to be done to restrict further damage.

If I could have my way, there would be a 200-km trail from Nandna, winding through the Salt Range touching upon all the temples enumerated above. There are stories to tell along the way and architecture to marvel at. Magnificent Bilot, with its collection of temples, would prove a fitting grand finale for the tour.

Also in Dawn

January 11, 2022

Tomb Recorder

His work is genuine, without shortcuts in his fieldwork and research methods, and the result — whether in his frequent newspaper articles or his books — is primary material for the reader interested in anthropological works. Kalhoro reminds one of the tireless and brilliant Adam Nayyar, executive director of the Pakistan National Council of the Arts who, sadly, left us too soon.

Kalhoro’s recent work, Wall Paintings of Sindh: From the 18th to 20th Century, is a treatise on the funerary art of the province. Interestingly, it is only in Sindh that we find on tombs depictions of the interred with their likeness clearly shown. It is as if, even in death, the life of the protagonist, lived well and to the fullest, is worthy of celebration. There are hunting scenes, battle scenes, peeks into domestic life and representations of the many love tales so fancied by any Sindhi.

Of the last, the tales of Sassui-Punnu, Sohni-Mehar (Mahiwal in Punjab), Momal-Rano and Umar-Marvi are the most favoured adornments on 18th century Baloch tombs. This was when the Kalhoros ruled over Sindh, and the Talpurs and other Baloch tribes looked up to them as spiritual masters. The Talpurs rose to high positions in the government and army and could afford to build their decorated tombs during their lifetimes.

Among these depictions, the rarest is a rendering on the tomb of Sobdar Jamali — who served in the army of the Kalhoros — near Shahdadkot of the fishergirl Noori, whose radiant beauty smote the 14th century Samma king Jam Tamachi. In this rare rendition, the lovers are shown in a boat. Since Jam Tamachi ruled from Thatta, the lake would be Keenjhar Jheel, where the lovers lie buried on an island.

Kalhoro notes that there were two other shrines with similar depictions. Sadly, all three tombs collapsed in the devastating monsoon storms of 2010. This rare depiction now only survives in this book. The floods that will pass into future folklore also seriously damaged several other monuments and we are fortunate that this tireless anthropologist has preserved them in this book.

According to Kalhoro, Sindhi art received heavy input from Rajasthani masters during the Kalhoro rule (1701-1784) which is discernible in the Drigh Bala tombs of Dadu. Elsewhere, we see the clear hand of local artists so well acquainted with the style and colour of the attire favoured by Sindhis.

One cannot but marvel at the detail these artists included in their work: for instance, the shepherd who casts his demonic eye on the distraught Sassui — as she wanders the desert after Punnu is kidnapped by his brothers to be taken back to Kech — is shown with a spindle, weaving goat hair into yarn. This is a common enough scene even in contemporary Sindh.

There is a clear evolution of the art from the early 18th century, when human and animal figures and historical events and love tales appeared as a matter of course. In a personal communication, author Kalhoro said this was the Sufi tradition of looking upon this life as a temporary phase. It was the afterlife where the late hero enjoyed everlasting glory, and the depictions in the tomb were a way of celebrating that life.

During the Talpur period (1784-1843), we see a shift to floral designs and depictions of mosques and other holy sites. Now, men are not so much in battle or in the hunting grounds, but seated cross-legged in front of the wooden rehl [book stand], with the holy book upon it.

As if to record a societal change, there are now depictions of women being killed. Kalhoro views this as a record of honour killing. As well as that, we see a robber having murdered a caravaner, levelling his rifle at the others, presumably to rob them. Most interesting is a pair of British soldiers, booted and helmeted, following Sassui as she pursues the caravan taking her Punnu back to Kech. While all these are from the 19th century, after the British takeover, care was taken to not deface earlier art, notes Kalhoro.

Clearly, patrons had declined with the end of the Talpur dynasty and, with them, the art. Writes Kalhoro: “The painters … were not skilled in executing figural painting in colonial and post-colonial Sindh, but they displayed great skill in geometric and floral designs.”

The funerary art of Sindh is unique for Pakistan. No other province has anything even remotely comparable. And Zulfiqar Ali Kalhoro has rendered a priceless service to history by putting on record what is fast eroding. Like all his previous works, this book, too, is essential reading and an important travel companion for any informed laypersons as they explore the hundreds of tombs sprinkled across Sindh.

December 26, 2021

Gwadar: Song of the Sea Wind

For long, images of the golden, unspoiled beaches of the Makran coast had “captured the imagination of the romantically inclined” as a place where one could “actually be away from the madding crowd.”

Other images, showing hills in “crumpled disorderly piles devoid of every shred of vegetation”, would tempt the wilderness enthusiast. But reaching the coast was not easy and, hence, the place remained unexplored.

However, things are changing fast and Gwadar — on the Makran coastline — is poised to become a bustling seaport and industrial city, mostly because of the much-celebrated China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Ever since Gwadar became easily accessible by road from Karachi, via the Makran Coastal Highway, there has been a regular inflow of tourists to the city, though foreign tourists are still to discover it.

With the growing importance of, and government attention on, Gwadar in mind, Shahzeb Khan Kakar, Director General of the Gwadar Development Authority (GDA), came up with the idea of preparing a document that presents an introduction to Gwadar and its promise of being a city of the 21st century. Well-known travel writer and fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, Salman Rashid, undertook the task of writing the book.

The book, Gwadar: Song of the Sea Wind, tells the story of not only Gwadar, but the entire coast from Sonmiani all the way to the last outpost Jivani, about 60 kilometres from Gwadar in the east and 115km from the Iranian port of Chabahar in the west.

Rashid chose to follow the route taken by Nearchus, a general in Alexander the Great’s army during his invasion of India. On retreat from India, Nearchus commanded a fleet of ships and war galleys and sailed to the Indian Ocean for the westward journey to Babylon from the Makran coast.

The book uncovers the history as well as the geographical details of the Makran coast in an engaging manner. Readers also learn about the origins of the names of the places when the Greeks travelled through, as Rashid has used the nomenclature of the Greeks, those given locally in the Baloch and Persian languages, and corresponding names with which the places are known today, justifying them by geographical location.

Contrary to popular belief, Makran is a melting pot of ethnicities. People from various origins live here, such as the Baloch, Jats, Africans, Brahuis and Gichkis. Some arrived in the area as traders and seafarers centuries ago, while others fled trouble in their native lands, mostly during the 16th century. We read of the myths and legends related to the Makran coast, especially about the origins of people with blue, green and pale yellow eyes and fair skin and hair, but whether they are descendants of the crew of the Greek ship that sank centuries ago, or of Turkish sailors who availed of the hospitality at Gwadar while fleeing Muscat when threatened by the Portuguese, will always remain a mystery.

In his captivating manner, Rashid tells readers about Astola Island, believed — according to Greek mythology — to have been claimed by the sun god, the myth about the daughter of the sun god and the superstition that anyone who went there was never seen again; hence, it being enchanted. The myth gained weight after an unnamed Greek ship manned by an Egyptian crew disappeared near the island.

The legend continued even in the 19th century, as British engineers laying down telegraph lines had been warned that it was dangerous to land on the enchanted island. The British believed Gwadar to be “suitable as the headquarters for the management of the telegraph” as it was situated midway between Karachi and the Iranian port town of Bander Abbas.

Travelling through, the Greeks discovered Makran to be a place of hardy people, where everyday life was a struggle because of its climate. While other towns were smaller and undeveloped, Pasni and Gwadar were much richer and civilised, with parks full of flowerbeds and trees.

In 1294, Venetian explorer Marco Polo passed through, and noted that the people of Makran were “professed traders” who took their business “by the sea and land in all direction.” Polo noted: “the staple in Makran was no longer fish as it had been at the time of Alexander” — there was a plentiful supply of rice, corn, meat and milk. As trading grew manifold, fishing was relegated to a secondary position, though — as Rashid points out — all this could only have been possible by a substantial increase in maritime trade.

Rashid reminds us that many of the world’s islands were not always islands, but were probably created when the Ice Age ended and floods from the melting ice raised sea levels by up to 30 metres. It is believed that Astola was connected to the mainland until the rising waters cut it off, turning it into an island. Whatever wildlife existed there mostly perished because of food scarcity, except for rats, snakes and lizards. Today, however, its sandy beach provides nesting grounds for many species of birds and the endangered green and hawksbill turtles, as in the British time, and its waters are home to several species of fish and dolphin.

There are reminders of historical events that influenced the region. For instance, how Gwadar’s ownership went from the Khan of Kalat to Oman, from which it was bought back by the Pakistan Government in 1958; or the plundering of Gwadar and Pasni by the Portuguese in the 16th century after they had driven the Turks from Muscat, which the Portuguese laid claim to and where the Turks were gaining a foothold.

The construction of the Makran Coastal Highway is not only opening opportunities for tourists, but also helping local fishing communities; they no longer have to salt and dry their catch and wait for Sri Lankan boats, as they did in the past. Now, refrigerated lorries wait to collect the fish and transport them to Karachi and onward to other parts of the country.

There are interesting descriptions of the architecture of Shahi Bazaar, which gained its character from the abundant use of timber, the graceful two-storeyed houses that memorialise Gwadar’s past affluence and of the gold-mining that continued through the 1990s. The various ancient buildings and the stories behind them are described in a manner that lets readers feel as though they’re travelling with the writer. It is heartening to learn that the GDA has taken note of the crumbling Shahi Bazaar and adjacent residential lanes and has plans to restore and preserve them.

The book is important since, after work done by British explorers and geographers in the 19th century, no such study had been carried out in the area. With Gwadar poised to receive world attention, Song of the Sea Wind is a treatise to be read and cherished. Printed on glossy paper with beautiful photographs, it will serve as a perfect travel companion to those who wish to visit the place.

While the entire Makran coast is a delight for the traveller, explorer, tourist and naturalist, in Rashid’s words, “It is Gwadar, the headquarters of seaboard Makran, that promises to be the gem.” He sees Gwadar not merely as a place of fun and frolic, focused only on tourism, but as a city of port and industry. There are also plans to establish an “Educational City” with all facilities such as a university, vocational training centre, medical college and nursing school.

The future envisaged for Gwadar is of a city drawing businesspeople from across Pakistan and abroad. It is to be a city with glittering malls, brightly lit streets and factories, all powered by electricity generated from wind, sun and coal.

One wishes that the plans for Gwadar’s development soon materialise, as this will not only be development of the region, but of the whole country.

Gwadar: Song of the Sea Wind

By Salman Rashid

Sang-e-Meel, Lahore

ISBN: 978-9693533385

144pp.

July 25, 2021

Mithi: Whispers in the Sand

Back then, the journey from Naukot to Nagarparkar, which lies at the easternmost edge of Tharparkar district — today, a five-hour drive — would take up to 14 hours, writes Salman Rashid in his new book, Mithi: Whispers in the Sand.

Rashid’s canon of work — especially his articles based on travels across Pakistan — has, over time, garnered something of a cult following and is widely viewed as a reliable source of history on the region. Travel writing on South Asia has historically been dominated by the narrative voice of European colonialists. Rashid, however, provides the perspective of a local, carefully sifting through the accounts of colonial adventurers, highlighting their biases and handicaps and setting the record straight where necessary.

The author first drove across Tharparkar district in 1984, wife and friend in tow. “It was like stepping into a country still in the 19th century,” he recalls. He would, over the course of four decades, keep returning to this remote region — including Mithi, the district’s largest town — and witness it transform. In his research for the book, he refers to the limited material available, including the works of British administrators such as Stanley Napier Raikes (magistrate of “Thurr and Parkur” in 1847), gazetteers, folklore and the “collective inherited memory” of locals, some of whom had received eyewitness accounts of events from their grandparents.

During his numerous visits to the district, the last of which was made in 2017, Rashid conducted a series of interviews with residents. These include a green-eyed Sodha thakur [landlord] whose ancestor brought the Rajput caste to this part of Thar in the 13th century; an affluent trader who has no desire to travel out of the region or enter politics, despite the insistence of many; nomadic jogis who believe that cobras never die natural deaths and can live for thousands of years, eventually shape-shifting into eagles or peacocks; and a retired official of the Wildlife Department, who saved the Indian gazelle from extinction and helped create a wildlife sanctuary in the district. These portraits form a significant portion of the book and provide readers with a nuanced understanding of life in the desert and how it is changing.

Like a detective, Rashid connects the dots, picking up on clues drawn from personal observation and various historical sources. He learns for instance, that the lost city of Pari Nagar, located at Virawah near Nagarparkar, dates back to the fifth century CE and once thrived as an international seaport, at a time when “an inland arm of the sea extended through the Rann [of Kutch] and right up to Virawah.”

The latter geographical detail is confirmed in the work of an anonymous Greek seaman who, having sailed past the Indus Delta in the first century CE, arrived at a gulf that lay west of the Gulf of ‘Cutch’ and wrote about it in a handbook titled Circumnavigation of the Eastern Ocean. Using Google Earth, Rashid sees the dried-up remains of this gulf, which culminates near the ruins of Pari Nagar.

Similarly, Rashid draws the attention of archaeologists to a mysterious site referred to as Singharo. According to Raikes’s Memoir on the Thurr and Parkur Districts of Sind, the fort — already in ruins by the mid-19th century — was built by the Talpurs, but Rashid estimates it to be far older, dating back to the 15th century, and serving as a residence of a Rajput prince. Its intricately carved blocks of white marble and architectural “lavishness” set it apart from the Talpur forts, he observes.

It was on his first visit that Rashid was introduced to the folkloric legend of “Turwutt” — a larger-than-life character who, according to a local of Nagarparkar, used to climb up the Karonjhar Hills daily, “to keep an eye on the world.” After a close reading of Sindh’s history and a biographical paper published in Britain in 1875, Rashid discovers that this is a reference to George Booth Tyrwhitt, a deputy collector of the district in 1857, who learned to speak the Thari language and is revered by locals to this day — much like John Jacob, an East India Company officer and the political superintendent at Jacobabad.

While history would have us believe that there was, throughout Sindh, “a quiet acceptance of imperial presence”, Rashid’s research suggests otherwise. He finds evidence of a Thari uprising against British rule in 1859, led by a celebrated military commander named Rooplo Kohli, and Rajput chief Rana Karan Singh Ranpuri. The former was hanged at Saigam, just outside Nagarparkar, and the latter imprisoned at Kala Pani, or the Cellular Jail on the Andaman Islands. Tyrwhitt’s popularity among locals is all the more puzzling in light of these events, especially since he was instrumental in ruthlessly quelling the rebellion.

Today, Tharparkar district is reputed to be one of the safest regions in the country and a place where, according to the locals, theft does not exist. But, as Rashid points out, it wasn’t always like this. Nicholas Withington’s account of his journey across Thar, starting in December 1613, paints a very different picture. As the English merchant approached Nagarparkar from Ahmedabad, Gujarat, he kept receiving news of “the murder by robbers of some hapless peripatetic trader.”

Travelling from Nagarparkar to Thatta, he was robbed numerous times, while the three Indian traders in his party were executed and dumped in “a hurriedly dug hole.” He decided to turn back, but was robbed yet again and this time was also deprived of his clothing.

Withington — who, according to Rashid, was the first European to visit Nagarparkar — notes that the residents of the region between Nagarparkar and Thatta did not pay tax or allegiance to the Mughal court and were answerable solely to local chiefs. Their favourite pastime was to rob travellers and then safely escort these victims out of their territory so that others could rob them.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Baloch marauders used Mithi as a base to conduct raids on Kutch towns, notes Rashid. This practice only came to an end after the British gained control of Thar in the 1850s. “Wily as British administrators were, they knew how to tame the unruly Baloch ... within a couple of decades ... they were given policing and military duties in Thar,” he writes.

Rashid also questions the interpretations of some of the local lore. Referring to Marui’s defiance of Umar, the Soomro king who kidnapped her, he writes: “Marui’s tale has long been sung as a love song. It is very strange that intellectuals failed to look at it as it really is: a story of resistance to the powers that be ... In Thar, and perhaps all of Sindh, it is Marui alone who stands out as an extraordinarily rebellious heroine: a young and defenceless woman who resisted the overtures of an all-powerful monarch and yet regained her freedom.”

He resents the way the government has “pimped up” the historic site of Marui’s well with modern structures and alien conocarpus trees, stripping it of its primal aura. The well is no longer accessible to Thari women, who would come here to fill their pitchers.

The Thar that emerges in the book is one that transcends man-made borders. Prior to Partition, Nagarparkar lay at the centre of all the action, as a way station on two ancient trading routes — one from Gujarat to Shikarpur and the other from Gujarat to Thatta. Up until the earthquake of 2001, Nagarparkar’s bazaar, with its terracotta roofs, resembled “a village in Lombardy.”

Change, however, is inevitable and has its advantages, admits Rashid. Within a few years, the Thar that he saw in 1984 will be no more. Phhoto, who belongs to the jogi cult, the members of which for centuries have wandered from place to place and exhibited serpents for a living, tells him, “Perhaps it is good that our children are turning to education and business. At least their lives will be better.”

The reviewer is a journalist. He tweets @_alibhutto

Mithi: Whispers in the Sand

By Salman Rashid

Sang-e-Meel, Lahore

ISBN: 978-9693533248

216pp.

Also in Dawn, Books & Authors, July 25th, 2021

June 8, 2021

Walton Aerodrome

Besides a servant or two, there was no one else in the house and I, wearying of things I did not understand, wandered off into the large garden outside. Through a gap in the hedge, I saw several planes parked by a steel wall. Today I know that would have been the wall of an aircraft hangar.

I poked about the clearly junked planes before clambering into the open door of one. Up the inclined aisle, I walked past dancing cobwebs, between tattered seats with more metal than upholstery, into the cockpit. I took one seat, grabbed the steering wheel and, producing sounds of engines, flew the giant machine into the blue welkin above. As the craft flew, I stood by the side window to watch the landscape unfold way beneath me.

I do not recall how long I flew over a very interesting world of rivers and forests before my uncle startled me. ‘Good job. You’ve flown long. Let’s go home now!’

The next time I saw Walton aerodrome was perhaps three or four years later, when I came with my mother to receive a cousin of mine, for this was the first international airport of Lahore. In 1962, they shifted the airport to a place in the cantonment, which for some inexplicable reason was marked ‘Fish Tanks’ on an old map of the area. Walton, again, became as it had started out in the beginning: a flying club.

The next time I saw Walton aerodrome was perhaps three or four years later, when I came with my mother to receive a cousin of mine, for this was the first international airport of Lahore. In 1962, they shifted the airport to a place in the cantonment, which for some inexplicable reason was marked ‘Fish Tanks’ on an old map of the area. Walton, again, became as it had started out in the beginning: a flying club. In the 1960s, I would cycle to Walton to watch bright orange gliders, hauled by an antiquated military vehicle with the lettering ‘Dodge Power Wagon’ on its bonnet cover. Once airborne, the pilot released the steel rope and flew free. Sometimes I would wonder if the pilots felt the same thrill I had experienced many years earlier, flying the aircraft which I now know was a DC-3 Dakota. Though the flying club has no gliders now, those who once took to the air in engine-less aircraft to acquire glider pilot licenses number a hundred and eighteen.

Rewind to the year 1930, when a group of aviators donated their personal holdings in this part of Lahore to establish the Punjab Flying Club. These gentlemen were Dr Gokal Chand Narang, Dr J.B. Sproull (a European resident of Lahore), Roop Chand and Sardar Bahadur Sir Sunder Singh Mijithia. On a grass strip, they began flying operations that year. By 1937, when the institution was renamed the Northern Indian Flying Club, it was spread over 156 acres of land. (Aside: over the years, much of this land was occupied by powerful agencies and turned into housing and offices. Today, the club holds less than a fifth of what it once owned.)

Come World War II and the flying club doubled as a military strip as well. Not long after, with Pakistan on the world map, the Quaid-i-Azam landed at Walton. The hangar today designated as the Ultralight Sports Flying Club (USFC) was used as a VIP lounge for the founder of Pakistan. Others of his followers also graced this building, according it premium position in Pakistan’s built heritage.

Post-independence, the Lahore Flying Club became the paramount aviator training institution of the country and, today, some 80 percent of the pilots flying for Pakistani airlines have passed through its doors on their way to the skies. Not only that, until 1952, 80 cadets of the Royal Pakistan Air Force, as it was then known, got their initial flying training here.

From the Walton runway flew Orient Airways, Pak Air and Crescent Air Transport, which were eventually to be merged into one that we today know as Pakistan International Airlines. In more ways than one, the Walton aerodrome, or the Lahore Flying Club if you please, has made much history in Pakistan.

With a respectable number of privately owned aircraft and trainee pilots, the club was just about breaking even — this because it receives no government funding. Trainee pilots pay a certain amount per hour to fly, and the club needs to have 200 hours of flying to generate enough funds to pay its staff. As for the salaries, they are nothing less than a joke. A trained aircraft mechanic earns 18,000 rupees per month, and the chief instructor makes just over 100,000 rupees! For most of these persons, keeping the club flying is a labour of love.

Duped by a glib land grabber, the government has agreed to shift the flying club in order to turn this beautiful open space with trees into concrete. For beginners, they have prohibited flying from Walton. No flying means no funds — that should effectively asphyxiate the institution. There are airy-fairy plans to shift the club to Muridke, outside Lahore. In the meanwhile, there is talk of forcing the club to remove its aircraft, spare parts and equipment to Faisalabad where, without a hangar and storage facilities, all will be at the mercy of the elements. All this equipment is worth several hundred million rupees.

The schemes to shift to Faisalabad or Muridke are, at best, hare-brained. Consider: the mechanics with their meagre salary will hardly be able to maintain the daily commute out and back. Some of these men are second-generation employees, who will certainly become jobless. If anything, the government owes them the gratitude to let them continue in their profession.

Consider those great men from landed families only 100 years ago who donated their personal holdings to create what eventually became the Lahore Flying Club. And loathe now those who began as clerks and coolies and made big money by sucking up to powerful men who now wish to destroy a legacy for a few more rupees in their already bloated bank accounts. Old money and new simply have no comparison.

We who recite Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s name as if it comes from scripture will not hesitate to tear down a building where he had rested his tired body after a journey from Delhi to Lahore. We almost did the same with Faletti’s Hotel and the room where Jinnah had stayed while attending court in Lahore back in the 1920s. But then pressure from those who care for this once-beautiful city prevented the destruction of that historic hotel.

Can we once again do the same to save a priceless piece of our heritage that we do not own? This is what we have rightfully borrowed from generations of the future and to whom we have to pass it on.

Postscript: Dr Sproull, a dentist, is listed as the second secretary of the flying club, serving from 1941 to 1948. Could it have been this gentleman that my doctor uncle had gone to see some years later, taking me along so that I could give myself the ride of my life?

Also in Dawn

April 16, 2021

Rehman Sahib

With Rehman sahib and Mahboob Ali, the only woodcut artist in Pakistan

With Rehman sahib and Mahboob Ali, the only woodcut artist in PakistanOnly months earlier, I had foolishly invested everything we had in those infamous ‘investment companies’ and lost my last rupee within three months. Incidentally, the company I invested with was Alliance, owned and run by a bunch of bearded mullahs of the Tablighi Jamat. So much for these spurious claims to lay down lives for the honour of prophet hood! Shabnam and I were completely impoverished in the name of religion as practiced in Pakistan and we had borrowed from friends in Karachi to move back to Lahore.

I needed to write somewhere and Pakistan Times was the only paper in Lahore I could write for. (I did not much care for two other papers then coming out of the city.) My introduction was met with instant recognition which was a bit of a surprise because I had only been writing since 1983 and did not expect to be known to someone of Rehman sahib’s stature. Now I know true greatness of the soul does not keep one from looking at lower stations of life. I asked if I could write for him and he at once asked for Aziz Siddiqui sahib to join us. Here I, a pygmy, was in the company of two intellectual giants of the gentlest demeanour imaginable.

Before sending me off with Siddiqui sahib, Rehman sahib said I should see him before leaving. In his office, Siddiqui sahib introduced me to a person whose name should best be left unsaid and told him I would be writing for his page. Sending the man off, Siddiqui sahib said, I was to always see him and no one else. I was to give my work to him and not directly to the page in charge. I was only to recognise Siddiqui sahib’s reservations after a few weeks. But that is another story that tells how perspicacious Siddiqui sahib was about my personality and the professional capacity of his underling.

Back in Rehman sahib’s office, I was offered an honorarium that, given our circumstance, seemed reasonable and I started writing for Pakistan Times. I was told to see him for payments at the beginning of the month. Those were pre-computer days (I got my first machine in 1991) and every week I would see Siddiqui sahib with my typescript hard copy. At the beginning of the next month I went in for my dues. Rehman sahib took out his wallet, counted out the money and said he had drawn my dues to make things simpler. This was the payment mode for the three or so months I wrote for Pakistan Times.

Then The Frontier Post began publication from Lahore and Beena Sarwar made me an offer that was too good to be true. I went to see Rehman sahib to tell him what I was being offered and if I had his permission to take it.

‘Bhai, iss main poochnay kee kya baat hai!’ – What’s there to ask, he exclaimed. With unstinting encouragement he told me to do as well as I had done while with him. A couple of years later while still at the Post, friend Sarwat Ali and I were talking of the time we both wrote for PT. Sarwat said the paper still owed him several thousand rupees because they had no money to pay freelance contributors.

Surprised I told him I was always paid in the first week of the new month. I also told Sarwat how Rehman sahib so kindly drew my dues so that I did not have to run around after the cheque. What Sarwat said next was a shock to me: Rehman sahib had been paying me out of his own purse!

That Shabnam and I were penniless when we moved back from Karachi was a fact known only to my childhood friend Parvaiz Saleh and army friend Moneir Aslam and no one else. There was no way Rehman sahib could have heard of our pecuniary position because neither Moneir nor Parvaiz were on Rehman sahib’s circuit. I remember remarking to Sarwat about it and he said that was Rehman sahib and he just knew. To this day I have not been able to figure out how he could have known and I never asked because I knew I would embarrass him. For that same consideration I never mentioned this act of insightful understanding and compassion either in writing or verbally to anyone.

Time rolled on as we struggled to get back on our feet. Some months later I went to see Rehman sahib and to his asking how I was doing I responded with the stock phrase that people normally use. I had never said ‘guzr rahi hai’ ever before because it was so redolent of defeat and I don’t recall what frame of mind I was in to utter this abject phrase. I got a right proper dressing down. ‘Guzr rahi hai?’ Rehman sahib almost exploded. Here I was not yet forty and so defeated by life. There followed a short talk the gist of which was to never give up the good fight. I left his office, my soul uplifted and prepared to take head on whatever life threw at me.

Thereafter I often met Rehman sahib and what I began to like most was the clarity of his thought. You asked a question and the response was utterly unequivocal. It was as crystal clear as his writing. His responses were meant to clarify, never to confound. It was as if Rehman sahib had been forewarned and had prepared for whatever I wanted to discuss. It was nothing of the sort. This was just a very great mind at work ready to give.

It took us a few years and we were back on track when Shabnam had some business with Rehman sahib. We climbed up to his top floor office in the Human Right Commission of Pakistan (HRCP) building. Seeing us he immediately turned away from whatever he was doing and with his patent impish smile asked after both of us. After Shabnam’s business was done, we chatted about things and I jokingly commented on how grumpy I was getting. The year would have been 1996 or thereabouts.

Since Mr Wilson of Dennis the Menace fame is a favourite character – and who could have played it better than Walter Matthau as in the first movie – I said, ‘When I grow old I am going to be as grouchy as Mr Wilson.’

Rehman sahib did not approve of that growing old phrase. ‘What is the matter with you? I am in my sixties and I don’t think of old age and here you are more than twenty years my junior dreaming of it!’

Another pep talk followed. The essence of what Rehman sahib said was to die young as late as possible; to keep the spirit alive and to value and cherish life. Death was not even to be thought about.

Rehman sahib became the haven to turn to when it blew hard and he was the anchor to tether one’s boat to when it got rough.

It was impossible to escape his scintillating sense of humour. At some function where tea or a meal followed, as we were heading for the food table, Rehman sahib, his face alight with that same mischievous smile waved his hand in the direction of the crowd milling around the table trying to get ahead of each other, and said, ‘Khana barpa hai!’ It sounded exactly as he had meant it to sound: the battle was afoot.

That was not his only one-liner. It is unfortunate that virtually thousands of his brilliant one-liners are now either lost or preserved in a few minds that were around him.

When Asma Jahangir suddenly passed away, I was at the funeral where I spotted Rehman sahib. In the years of my association with him, I had come to know how close he was to that wonderful feisty human rights defender that Asma was. I went across to him. We shook hands and before I could say anything, my face contorted as I tried to control my emotions. Rehman sahib squeezed my hand and nodded. Nothing needed to be said. For a brief while he and I sat down either on a bench or some chairs laid out without speaking. Then he was swamped by others and I excused myself.

For some time now I had been thinking of photographing my senior friends and a few months ago I went to the HRCP offices with my camera. Rehman sahib was not there. I called his son Asha’ar to ask and he said, he was a bit irregular at work and that I could always come around to do the photography at home. But I was engaged in a project and the mission kept getting put off. And then it was too late.

I was in the outback of Sadiqabad (Rahim Yar Khan) where cell phone signals were erratic. One evening I got a truncated text message from Shabnam about someone being ‘no more’. I had waited too long to photograph the man I had come to know in 1989 and learnt to love and respect for what he was. Now his smile will live only in my memory.

Returning from the south I went to see Asha’ar. I had thought it unnecessary to call beforehand. Because Asha’ar was down with a fever, his wife (who I had never met) came out to ask. I told her I was away and could not attend the funeral. All she had to say how great a loss it had been and I broke down. I don’t know what she would have thought of my abrupt turn about as I came out of the house. She might have considered me a horribly uncouth person to leave so suddenly, but I did not want her to see.

In the car, I wept.

February 21, 2021

Happy Birthday to Me

February 12, 2021

From Landi Kotal to Wagah

The result of a collaboration of more than two years, the coffee table book explores the built and intangible heritage along the Grand Trunk Road (GT Road) in Pakistan, combining a thoroughly researched narrative with a wealth of photos that illustrate the diverse and rich panorama of this 2500-year-old historical trade road. Over the centuries, the road has been extensively travelled by traders, pilgrims and great civilizations like the Greeks, Turks and Mughals who left their marks, perpetuating the mythical status of this legendary road.

The aim of the book is to foster tourism, promote awareness and ultimately protect the little known historic sites (largely non-Muslim) along the GT Road that spans over 2400km from Bangladesh to Afghanistan. The development and publication of the book was supported by the Embassy of Switzerland, the European Union and the World Bank. The author is Salman Rashid, a preeminent travel writer and a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. The book is richly illustrated with photographs taken by Asad Zaidi. It is distributed in a co-publishing arrangement with Sang-e-Meel Publishers.

At the book launch, Patricia McPhillips (country representative and director, Unesco) welcomed the guests and thanked all partners for their support and contribution. She stated: ‘Through this book, the Unesco hoped to highlight the vast potential cultural development in various parts of Pakistan, and the pressing need to preserve and protect heritage sites, to further our shared cause of encouraging cultural pluralism and social cohesion.”

Welcoming the publication of the book, Bénédict de Cerjat (ambassador of Switzerland) highlighted the rich and impressive cultural heritage of Pakistan. He emphasized that the Grand Trunk Road is one of Asia’s oldest and longest major roads, which has linked Central Asia to the Indian subcontinent, facilitated trade for centuries and is still used for transportation. He commended the Unesco for its valuable initiative and encouraged the guests to follow the author’s journey and discover the many fascinating places along the historical road.

In her speech, Androulla Kaminara (ambassador of the European Union to Pakistan) emphasized: “Over the centuries, along the Grand Trunk Road not only goods but cultures, ideas, religions and languages were exchanged, leaving a permanent trace on the societies along the road today. This rich heritage is an important manifestation of cultural diversity that needs to be protected and promoted, especially for its key role in attracting tourism and boosting economic growth which are priorities of the government of Pakistan.”

The author of the book, Salman Rashid, spoke about the many years he has spent traveling along the GT Road, and the fascinating history and culture he has experienced in his travels, which can now be shared with readers through this book.

The chief guest, Shafqat Mahmood, federal minister for National Heritage and Culture Division, appreciated the role this book will play in fostering tourism, while also preserving the history and heritage of Pakistan for the generations to come.

All partners emphasized that this unique book serves to encourage the people and government of Pakistan to protect and preserve the heritage which forms an integral part of the history of the land that is now Pakistan.

Also here, here, here, here and here

Salman Rashid's Blog

- Salman Rashid's profile

- 43 followers