David R. Stokes's Blog

September 5, 2018

DAVIDSTOKESLIVE.COM

https://davidstokeslive.wordpress.com/

The post DAVIDSTOKESLIVE.COM appeared first on David R. Stokes.

April 4, 2018

Dr. King—The Preacher’s Last Year

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was killed 50 years ago today in Memphis, Tennessee. I wonder what he would think about our national journey since the day his powerful voice was so violently silenced?

He was a great man on so many levels. But he was first a pastor/preacher, erudite and eloquent, persuasive and passionate—and at times controversial—in the pulpit.

A year to the day before his death in Memphis, Dr. King preached Riverside Church in Manhattan. The church, built against the backdrop of the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy of the 1920s, was founded by Harry Emerson Fosdick and John D. Rockefeller Jr., a liberal preacher with a generous benefactor. Mr. Rockefeller initially donated more than $10.5 million, and his contribution grew to more than $32 million by 1959. It was a case of petro-dollars funding Protestant liberalism.

As Dr. King spoke to a crowd of nearly 4,000 on April 4, 1967, he said that as a religious leader he wanted to “move beyond the prophesying of smooth patriotism to the high ground of a firm dissent.”

His subject was not Civil Rights – it was the Vietnam War.

Though careful to talk about America as his “beloved nation,” and not hesitant to address the crowd as “my fellow Americans,” he said that “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world” was “my own government.”

At that time, polls indicated that nearly 75% of Americans supported the war.

Dr. King faced his own media firestorm in the immediate aftermath of his “Beyond Vietnam” speech. The Washington Post described it as “unsupported fantasy,” and the New York Times called it “Dr. King’s Error.” U.S. News and World Report went even further, suggesting that King was “lining up with Hanoi,” and President Johnson angrily speculated that King had “thrown in with the Commies.”

Even legendary baseball player/hero Jackie Robinson came out against the speech and the NAACP adopted a resolution warning that King’s effort to connect the anti-war movement with civil rights was a “serious tactical mistake.”

Later that year, the annual Gallup Poll of the “Ten Most Popular Americans,” would not include the name of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.—for the first time in more than a decade.

One long and very difficult year after his Riverside remarks, Dr. King was in Memphis. The night before his death, he was scheduled to speak at Mason Temple. There were storm and tornado warnings, and he was weary from travel, so he asked Rev. Ralph Abernathy to go in his place. When Abernathy got to the church, he saw thousands who had braved violent weather to hear King, so he called back to the Lorraine Motel and encouraged his friend to come over. King did go over, and he gave what was to be his last sermon.

During his 20-minute extemporaneous address that evening, he asked: “Who is it that is supposed to articulate the longings and aspirations of the people more than the preacher?” He then added a word of encouragement to the great number of preachers in the crowd:

I want to commend the preachers…and I want you to thank them, because so often, preachers aren’t concerned about anything but themselves. And I’m always happy to see a relevant ministry.

As he warmed to the crowd and his message he said: “We don’t have to argue with anybody. We don’t have to curse and go around acting bad with our words.”

He called for the development of what he referred to as “a kind of dangerous unselfishness” and segued to a rhetorical comfort zone, the biblical story of the Good Samaritan. He used the famous story as the basis for his admonition: “Let us rise up tonight with a greater readiness. Let us stand with greater determination…we have an opportunity to make America a better nation.”

Then he waxed personal, describing a previous assassination attempt by “a demented black woman” ten years before and how the blade came so close to his aorta that one sneeze would have ended his life. This was a familiar King story, one that he told many times with the refrain “If I had sneezed…” being repeated again and again for effect. At this point, other preachers on the platform that night became unsettled because this story was usually one placed earlier in a speech. The concern was that Dr. King might “miss his landing” and not end on a high note.

There is an old formula in the African-American tradition of preaching: “Start low, go slow. Rise higher, catch fire. Retire.” The concern was that King was not quite catching fire. Then, however, came those final moments as he talked about being to the mountain top and seeing the “promised land,” and the now famous and passionate ending:

So, I’m happy tonight! I’m not worried about anything! I’m not fearing any man! Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!

As a preacher, King was Sunday-centric, always with an eye on the next sermon. So the next afternoon, Thursday, April 4, 1968, he placed a call from room 306 of the Lorraine Motel back to Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta and gave his secretary the title for his upcoming Palm Sunday sermon: “Why America May Go to Hell.”

He never had the chance to preach that one. A few hours later his voice was silenced in a brief and deadly explosion of violence.

Dr. King is remembered all these years later for his words and deeds. He is honored–appropriately so—as a hero. It is, though, an interesting question: What would Dr. King say today?

The post Dr. King—The Preacher’s Last Year appeared first on David R. Stokes.

September 23, 2017

65 Years Ago: The Day Politics Met Television

AS SUMMER TURNED to Fall in 1952, Richard Milhous Nixon was a young politician in a hurry. In just six years, he had gone from obscurity to celebrity. His future seemed secure and bright as the Republican Vice Presidential nominee on the ticket with the most popular political candidate in generations—General Dwight D. Eisenhower. But Nixon’s national ascendancy was almost over before his fortieth birthday. A scandal about a “secret rich man’s fund” was making newspaper headlines across the country. Many called for him to be dropped from the ticket. Even Eisenhower’s support wavered.

Nixon decided to do damage control in a way no politician had done before—via a nationally televised address.

It was the dawn of the television age—the beginning of an entertainment, information, and communication seismic shift. In living rooms around the country, the large radio was being exiled to elsewhere in the house in favor of the contraption Edward R. Murrow would later characterize as “lights and wires in a box.” But until that September night when Richard Nixon spoke “coast to coast,” the shift from wireless to tube was anything but a fait accompli.

Nixon’s speech was, in fact, the first full synchronization of medium and message for a new age. More Americans watched Nixon that September night than would watch any single event on television for many years to come. But even politicians were slow to figure out what it all meant. The Republican National Committee put their Vice Presidential candidate on two radio networks (Mutual and Columbia; MBS, CBS), while on only one television hook-up (NBC). But, no matter—suspense built, and by airtime at 9:30 p.m. (eastern) on Tuesday, September 23, 1952 nearly 60 million viewers tuned in—an unheard of audience up to that point and well beyond.

Forget that Jersey Joe Walcott was defending his World’s Heavyweight Boxing Championship that very hour against a guy named Rocky Marciano (complete with Rocky’s famous knockout punch)—people wanted to hear what this man accused of financial improprieties would have to say. Would Nixon resign from the Republican ticket? Would he tell the truth? Would he really give out his personal financial details when no other politician had ever done so in such a public manner?

What viewers saw that night was a presentation—primitive in its production quality, in keeping with the technology of the young medium—but carefully crafted and skillfully delivered. It was a deliberately arranged combination of facts, figures, and family. At moments it was clinical. Occasionally it was corny. But it all worked.

Pat Nixon sat near her husband at the otherwise empty El Capitan Theater in Hollywood. Some reporters saw her presence cynically, but they soon forgot about that as Mr. Nixon told a story that would chisel this small screen moment in storied stone. It was about a cocker spaniel.

A dog named Checkers.

Nixon didn’t read a script or use a teleprompter. He just used a few notes to aid his prodigious memory. He demonstrated a mastery of detail and appeared to Americans as a sort of new kind of political communicator—just a guy having an animated conversation with friends. When the half-hour was up, the camera lights were turned off before the candidate could actually give out the contact information for the Republican National Committee for phone calls and telegrams. Mad at himself for the mistake, he was certain he had failed.

Then he noticed one of the cameramen had tears in his eyes.

A moment later, Darryl Zanuck, the Hollywood mogul whose career included the production of the first “talking” movie (The Jazz Singer in 1927) and hits such as All About Eve (1950), telephoned. He told Nixon that the broadcast was “the most tremendous performance” he’d ever seen.

Calls and telegrams overwhelmed the RNC. It was obvious that Nixon had not only won the day, but he had also tapped into something powerful. Years later, he would have a problem or two with television, but that night in 1952 he not only survived his first political firestorm—he triumphed.

David R. Stokes is a pastor, author, columnist, and broadcaster. His latest book, The Churchill Plot, is an espionage thriller set against the backdrop of Winston Churchill’s death and funeral in 1965. David’s website is: www.davidrstokes.com .

The post 65 Years Ago: The Day Politics Met Television appeared first on David R. Stokes.

February 20, 2017

Of Coolidge, Harding, and Hoover

Happy President’s Day.

On August 2, 1927, President Calvin Coolidge had breakfast in the White House residence with his wife, Grace. He remarked to her, “I have been president four years today.” It was one of those quick, concise, directly-to-the-point sentences she had been used to hearing since they first met in 1905. It was also something the American people were familiar with, having nicknamed the 30th president “Silent Cal.” Mr. Coolidge ascended to the nation’s highest office following the sudden food-poisoning death of Warren Harding in a San Francisco hotel in 1923. The next year he won his own full term in a landslide election victory.

He had a meeting with reporters in his office that morning. Before fielding a few questions, he said, “If the conference will return at twelve o’clock, I may have a further statement to make.” Curious, but compliant, in those long-since-gone days of semi-civility between presidents and the press, the journalists found their way back at noon.

Shortly before than noon meeting, Coolidge took a pencil and wrote a message on a piece of paper. He handed it to his secretary with the instruction to take it to his stenographer and have him make a few copies. Ever the frugal man, he suggested that the brief statement could be copied several times on the same sheet, thus economizing on paper. He told the secretary not to give the note to the stenographer, though, until ten minutes before noon. Attempts by presidents to manage a news story are nothing new under the sun. Mr. Coolidge asked for the pages to be brought to him uncut. Before the reporters were admitted to the office, he took a pair of scissors and cut the paper into smaller slips. When he was just about ready, he told his secretary:

I am going to hand these out myself; I am going to give them to the newspapermen, without comment, from this side of the desk. I want you to stand at the door and not permit anyone to leave until each of them has a slip, so that they may have an even chance.

The handwritten note from the president said, simply: “I do not choose to run for president in nineteen twenty-eight.” Though the classic play The Front Page (currently in revival on Broadway) was still a year away from being first published and produced, the rush from the President’s office that day comes to mind as the reporters rushed out to find telephones.

Calvin Coolidge could have been re-elected if he had wanted the job for another term. His anointed successor, Herbert Hoover, went on to win big in 1928, though it is clear that Coolidge was less-than-enthusiastic about him. It is one of those curious “what ifs” of history; would Coolidge have dealt with the coming of the Great Depression better than his successor?

Historians tend to bunch the three Republican presidents of the 1920s—Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover—together in a way suggesting they were identical triplets separated at birth. But there were many differences—some subtle, some not so much.

Herbert Hoover, all of his speechifying about “individualism” notwithstanding, was not the fiscal conservative many today make him out to be. As Amity Shlaes pointed out in her book, The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression, a few years ago, Mr. Hoover had a strong penchant for interventionist policies. He “could not control his own sense of urgency,” and “liked to jump in, and find some moral justification for doing so later.” In many ways, he helped to turn a recession into the Great Depression “by intervening in business, by signing into law a destructive tariff, and by assailing the stock market.”

Ironically, when closely examined, Herbert Hoover’s approach to economics had more in common with his successor (FDR) than it did with the two men preceding him in the White House.

Warren G. Harding generally ranks in the bottom five when studies are done about the effectiveness of our chief executives. In fact, Hoover fares better than the man from Marion, Ohio. This is largely due to the scandals that came to light after his untimely death—the affair known as Teapot Dome. Also, some of Mr. Harding’s personal behavior was less than presidential. That said, he might have been a saint on that front compared to a few future chief executives.

What is usually missed about Harding is how effective he was on the issue of the economy. When he assumed the presidency in March 1921, he inherited a mess. Woodrow Wilson had expanded the role and size of government dramatically, incurring a $25 billion-dollar debt. He also had authoritarian tendencies, even imprisoning a few political enemies (e.g., Eugene V. Debs, the perennial Socialist presidential candidate).

The truth is, the economic problems in the 1920-1921 depression were actually worse in many ways than the Great Depression a decade later. But the earlier downturn didn’t last as long. Warren Harding cut federal spending and lowered taxes, and in less than two years the number of unemployed in the country fell from 4.9 million to 2.8 million. The trend would continue for a few years, falling to a rate of 1.8 per cent by 1926 under Coolidge. Harding also set the political prisoners free, even inviting Eugene Debs to the White House. Frankly, the twentieth president was highly-effective and very popular before his untimely (and some whisper, suspicious) death. Most of the scandalous stuff came out later— sort of like what happened after President John Kennedy died.

By the time Calvin Coolidge became president upon the death in 1923, the country enjoying a time of optimistic prosperity. He was a fiscal conservative who tried his best to stay out of the way. He believed that the government functioned best as a referee—not as an active player in the economic game.

After he was elected in his own right, Coolidge told the nation in his March 4, 1925, inaugural address:

I want the people of America to be able to work less for the government and more for themselves. I want them to have the rewards of their own industry. That is the chief meaning of freedom. Until we can re-establish a condition under which the earnings of the people can be kept by the people, we are bound to suffer a very distinct curtailment of our liberty.

His decision not to run in 1928—at the height of his popularity—puzzled many. But Coolidge understood the nature of leadership and its seductions. He explained it this way:

It is difficult for men in high office to avoid the malady of self-delusion. They are always surrounded by worshipers. They are constantly, and for the most part sincerely, assured of their greatness. They live in an artificial atmosphere of adulation and exaltation, which sooner or later impairs their judgment. They are in grave danger of becoming careless or arrogant.

I believe that had Calvin Coolidge decided to run again in 1928, he would have responded to the initial shock waves of 1929-1930 differently than Herbert Hoover did. And maybe, just maybe, the Great Depression would not have lasted so long. At any rate, Mr. Coolidge died suddenly on January 5, 1933, after Hoover had been badly beaten by Franklin Roosevelt. He did not live to see what a prolonged depression looked like, but one suspects that he would have ventured an opinion or two.

And his words would have been brief and directly on point.

The post Of Coolidge, Harding, and Hoover appeared first on David R. Stokes.

January 17, 2017

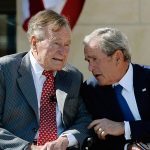

Becoming a FORMER President

Long after nightfall on January 20, 1969, Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson arrived at their 330-acre Texas ranch. LBJ had been an ex-President for just a few hours. Throughout the day people had gathered, first at Andrews Air Force Base, then at Bergstrom Air Force Base in Texas. They showed up to say thank you to the man who had ascended to the presidency in those chaotic Dallas moments more than five years before—and who less than a year before had pulled himself out of the race for a final term in the White House.

One of the first signs that life was going to be comparatively perk-free was when they came upon the scene of their massive collection of luggage. It had all been left in the carport that evening with no one around to carry the bags. Mr. and Mrs. Johnson laughed, and she remarked: “The coach has turned back into the pumpkin and all the mice have run away.”

The U.S. Senate is sometimes referred to as the country’s most exclusive club. But actually, that distinction better describes the fraternity of former Presidents of the United States. Reentering the atmosphere of earthly reality, minus the privileges and powers inherent in our nation’s highest office, has not always been an easy adjustment.

As we move into the noon hour this Friday, we will have five former presidents roaming the land. There is the first President Bush who has clearly managed to conduct himself with the kind of self-effacing dignity that characterized his personal style during his Oval Office tenure. His son, George W. Bush, has obviously learned from his father.

Then there are Jimmy and Bill – two men who seem determined to magnify the weaknesses of their previous service in ways that make the news on a near-daily basis.

For a long time after Mr. Carter headed back to Plains, Georgia, after a single frustration-laden term, I often thought that he was a better ex-president than he was a president. He was building homes for the poor, teaching his Bible class, and using his influence for the general betterment of mankind. But frankly, I liked “Habitat for Humanity” Jimmy much better than the “Hurray for Hamas” cheerleader who has too often conducted his own misguided and counterproductive shuttle diplomacy without portfolio.

Bill Clinton reminds me a little of Theodore Roosevelt, at least in the sense that TR reputedly wanted to be the bride at every wedding he attended and the occupant of the casket at every funeral. Mr. Clinton seems to want to be the candidate in every election.

It remains to be seen what kind of former president Mr. Obama will be. He will remain a resident of Washington, DC, which may make it hard for him to fade away. Stay tuned on that one.

In fairness, being a former president must be an awkward thing. Woodrow Wilson (the last president to remain a DC resident, though Bill and Hillary maintain a home in the district) left office a broken man – physically and emotionally—the cheering having stopped long before his White House exit. Lyndon Johnson went back to Texas and spent his final years working at his ranch and on his memoirs.

Some former presidents found their second wind after leaving office. Richard Nixon made a new career for himself as a writer and thinker – and did much to rehabilitate his image and reputation after his resignation. His funeral in 1994 (attended by all four members of the fraternity at the time) was in many ways a healing event providing a measure of needed closure. His successor Gerald Ford, by all accounts, enjoyed the high esteem of his countrymen – as did Ronald Reagan, even as he entered and endured the long and sad goodbye of Alzheimer’s Disease. Harry Truman conducted himself well as a former president – though, sadly, he didn’t live long enough to see his complete recovery from the distinction of leaving office with the lowest ever recorded approval rating.

But I think the gold standard for ex-presidential life and service, was set by a man who seemed to embody the very idea of an ineffective presidency.

I am, of course, referring to Mr.Thirty-One: Herbert Clark Hoover.

In a real sense, the presidency was the worst thing that ever happened to him. He had been so successful prior to that and was known for his unmatched resume and clear sense of duty and compassion. The man pretty much saw to it that Europe didn’t starve after The Great War ended in 1918.

His election in 1928 was one of the most inevitable political events of those times. It was a no-brainer. The Great Engineer was probably the most qualified man ever to hold the office. But we all know the rest of the story. The economic catastrophe of the age happened on his watch, and for a number of reasons, his reputation as a great man unraveled.

It’s interesting to note that Hoover wrestled with what to call his crisis. Up to that time, massive financial reverses had been referred to as panics. But Hoover didn’t want to scare folks, so he made sure the obviously more benign term – depression – was used. Of course, he didn’t foresee the addition of the enduring modifier great to it.

Mr. Hoover was swept out of office by promises of change including the “yes we can” of the day: “Happy Days Are Here Again!” Of course, the truth is that Franklin Roosevelt didn’t really change much, adopting and continuing many of Hoover’s policies and approaches. But his frenetic first hundred days and his savvy use of the media of the times made sure that people “felt” like things were changing. FDR was, in many ways, the father of the post-modern politics of meaning.

Hoover lived for more than thirty-one years as a former President. He wrote sixteen books (including one titled Fishing for Fun – And How to Wash Your Soul), and eventually was able to serve his country again with great distinction. I say “eventually” because he was banned from the White House during FDR’s lengthy administration. In fact, the relationship between the thirty-first and thirty-second presidents was probably the worst ever between two former chief executives. For all of FDR’s purported charm, he also had a capacity for brutal pettiness.

In the early days of his presidency, Harry Truman invited Hoover back to the White House – something both men felt was long overdue. And as Europe struggled to recover from the ravages of World War Two, Mr. Hoover was dispatched by the President to tour Germany—using Herman Göering’s old train car—to investigate the food supply. Hoover told Truman that the situation was dire, and this was the catalyst for an extensive program that provided food for millions of school children.

The 40 tons of food were described at the time as Hooverspeisung – Hoover Meals.

Soon another assignment came from Truman. He asked Hoover to serve on a commission to reorganize the executive departments of the federal government. He was elected chairman and it then came to be known as the Hoover Commission. When Dwight D. Eisenhower became President in 1953, he asked his most recent Republican predecessor to serve as chairman of another such commission.

And by the time Herbert Hoover died at the age of ninety in October 1964, having lived out his final years in an apartment at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York City, he had proven himself to be a dedicated and constructive former President of the United States.

It seems to me that former Presidents have two good options if they want to preserve or enhance their legacies. They can go to the ranch, like Lyndon. Or they can wait to be called on to serve, like Herbert.

When former Presidents take too much initiative to seize the moment, they seem to be forgetting that they already had their turn.

I wonder how what kind of former president the next one will be?

The post Becoming a FORMER President appeared first on David R. Stokes.

December 23, 2016

The Forgotten Christmas Song

Christmas is more than a day in December. It’s a season. Reminders of this are all around us, from the weather, to the gatherings, to the music on the radio. It is not unusual for savvy media outlets to saturate their formats with all things Yuletide for a few weeks at the end of the year. It puts us “in the mood”—and money in their accounts.

What’s your favorite Christmas song? Some like to hear about chestnuts roasting on an open fire. Others love to think about bells jingling. Yet others tear up (with good reason) thinking about a Holy Night so long ago. They may even want to fall on their knees.

A case can be made that the greatest Christmas song ever written is one with no familiar music. The tune is no longer available to us. But the lyrics, ah, those lyrics—well, they’re actually inspired.

As the Apostle Paul was writing to young Pastor Timothy about everything from order in the church to the dangers of greed, he gave us an easily overlooked but enduring Christmas nugget. It may be not be a toe-tapper like I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus—but it completely captures the essence of Christmas. That essence is incarnation.

God became one of us so that He could reach those of us willing to surrender to Him.

As the Apostle wound up a series of thoughts about the church and those who serve and lead, he paused to reflect on a larger issue. Strategies and structure are not ends in themselves. They are secondary to powerful ideas. While he may have felt the need to give Timothy some practical advice about how to do his important job, he never lost sight of the why in all of it. Nor should we.

There can be many controversies in life—macro and micro. All of them require attention. Some of them require systems and structure. No doubt, this was something with which Timothy wrestled. Therefore, his wise mentor, Paul, offered advice.

Things that tend to polarize people often have little to with objective truth. Instead, subjective experience is allowed to play too large a role in our lives and passions. When this happens, Paul’s writings suggest that we need to stop and sing. And we should sing something very specific, the most beautiful of all Christmas carols, though it is highly unlikely that we’ll hear the words blended with any seasonal music.

We are not told the style of music, nor are we told the instrument or instruments used to express it (if any). We are given just the words, and they have endured. They are ancient words, yet ever new.

The first Christmas Carol is introduced in scripture this way: “Beyond all question, the mystery of godliness is great…” (I Timothy 3:16 NIV).

Communities of faith throughout history have wrestled with many things. But Paul reminds us all these centuries later that there are some no-brainers for the faithful. First and foremost is that most powerful of all ideas is that God has come to the earth—the Word has been made flesh.

So, this season, let us reach back for one of the forgotten “oldies”—a first-century worship favorite. They likely sang it in places like Ephesus, Thyatira, and Philippi. There were no ornate cathedrals or padded pews, or multimedia presentations to tantalize the eyes. Just powerful words. Go ahead and make up your own music, but don’t mess with the words. They are from God—a Christmas gift from the one who gave us the reason for the season.

And, one…two…three…

“He appeared in a body,

Was vindicated by the Spirit,

Was seen by angels,

Was preached among the nations,

Was believed on in the world,

Was taken up in glory.”

I Timothy 3:16 (New International Version)

Merry Christmas!

The post The Forgotten Christmas Song appeared first on David R. Stokes.

December 17, 2016

A Kinder, Gentler Churchill?

Winston Churchill was indomitable, often rude, terribly stubborn, and clearly enamored of his opinions. But did you know that he also had a softer side? It’s true. The English Bulldog had a great capacity for graciousness.

Churchill’s pathway to power as Prime Minister of Great Britain on May 10, 1940 had been paved with persistent criticism of political opponents and even of colleagues in his own Tory (Conservative) Party. He saved some of his most stinging barbs for his predecessor at number 10 Downing Street, Neville Chamberlain. Among his criticisms of Chamberlain was this particularly caustic remark: “At the depths of that dusty soul there is nothing but abject surrender.”

But in spite of all the venom, Churchill was overwhelmingly kind to Chamberlain after taking his job. That’s right, Winston Churchill had a “warm and fuzzy” side.

One of the first things Churchill did in May 1940 was to tell Chamberlain that he and his wife could stay in their home at 10 Downing Street for the immediate future. Neville’s wife, Anne, not only enjoyed living in the Prime Minister’s residence, but she had actually done much to improve the dwelling.

Neville was moved by this generous gesture. Though he had taken chronic offense at Winston for his personal attacks in the House of Commons and the press, considering him something of an enemy (even once having Churchill’s phone tapped), it’s clear that this feeling was not reciprocated on a personal level. Winston remained personally loyal. This would pay significant political dividends during fragile moments when the War Cabinet was debating whether or not to make peace overtures toward Hitler. Chamberlain backed Churchill on that.

Neville was also dying.

“Blood, toil, tears, and sweat,” are famous words to us today. They evoke thoughts of courage, fearlessness, and an unwavering determination to succeed. Other Churchillian phrases echo down to us through the corridors of time – words like: “finest hour,” “we shall never surrender,” “we shall fight on the beaches,” and so forth. They are timeless and meaningful.

But I think one of Winston Churchill’s best orations from those days has been overlooked for too long. It was the eulogy he shared about Neville Chamberlain, who succumbed to complications due to stomach cancer on November 10, 1940, just six months after leaving office:

It fell to Neville Chamberlain in one of the supreme crises of the world to be contradicted by events, to be disappointed in his hopes, and to be deceived and cheated by a wicked man. But what were these hopes in which he was disappointed? What were these wishes in which he was frustrated? What was that faith that was abused? They were surely among the most noble and benevolent instincts of the human heart, the love of peace, the toil for peace, the strife for peace, the pursuit of peace, even at great peril, and certainly to the utter disdain of popularity or clamor. Whatever else history may or may not say about these terrible, tremendous years, we can be sure that Neville Chamberlain acted with perfect sincerity according to his lights and strove to the utmost of his capacity and authority, which were powerful, to save the world from the awful, devastating struggle in which we are now engaged. This alone will stand him in good stead as far as what is called the verdict of history is concerned.

Winston Churchill was not the one-dimensional warmonger some in his day thought him to be, an opinion that persists in some quarters today. He was an inspiring leader at the right time and in the right place. And he had a way with words, like when he said:

In War: Resolution. In Defeat: Defiance: In Victory: Magnanimity. In Peace: Goodwill.

[David’s next book, a thriller called, THE CHURCHILL PLOT, will be published in 2017.]

The post A Kinder, Gentler Churchill? appeared first on David R. Stokes.

October 11, 2016

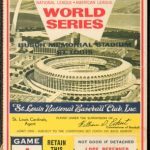

A Forgotten Hero of October

This time of year, as Autumnal rays lengthen shadows and trees are clothed in color, I usually find myself thinking a lot about what was going on 48 years ago—in 1968. It was time of conflict, assassination, national division, international disorder, and cultural explosion.

But I remember it also as a great year for baseball. It was the last year before divisional play began to fill October wall-to-wall. Back then, there were just two leagues—American and National. No divisions. So October baseball competed with Sunday football for barely one weekend. In fact, the World Series was over before Columbus Day.

It was also the year of Mickey. Three men named Mickey, to be precise.

MICKEY MANTLE hits his 535th home run off Denny McClain

There was Mickey Mantle, who was retiring at the end of the season after a certain-to-make Hall of Fame career. His last visit to league stadiums became a farewell tour of sorts. I saw him play his last game at Tiger Stadium in Detroit near where I grew up. And when he came to bat for the final time, I saw pitcher Denny McLain throw him a fat pitch designed to let Mickey hit it into the right field stands. When The Mick rounded second base on his final home run trot in Detroit, he tipped his hat to McLain.

It was very cool.

MICKEY LOLICH

Of course, being a life-long Tiger fan, the mention of the name Mickey immediately brings to mind a guy named Mickey Lolich, a journeyman left-hander who found the ultimate groove that October. He had long pitched in the shadow of teammate McLain, who won 31 games that year (the last man to win 30). But the locals knew he had the stuff. And in the World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals, he pitched game seven on just two days rest and went the distance (that’s nine full innings—there’s no law against this) to lead the Tigers to the World Championship. This was long before baseball discovered “closers,” “middle-relievers,” and “pitch counts.”

But there was another Mickey that year—and he’s one of baseball’s forgotten heroes. His name—and you may have to scratch your head to remember—was Mickey Stanley. He was a gold-glove centerfielder, and a pretty fair hitter.

As the Tigers coasted toward the series that year, manager Mayo Smith knew he had a problem. You see, he had four great outfielders and only three positions: Mickey Stanley, Jim Northrup, Willie Horton, and another man destined for the Hall of Fame on the first ballot. His name was Al Kaline, one of the greatest all-around players ever. He came straight to Detroit from High School in 1953, and never spent a day in the minor leagues. In 1955, he became the youngest player ever to lead the league in batting, with a .340 average.

He broke his hand ’68 and missed many games. The outfield performed well in his absence, but Manager Smith knew that this might be Kaline’s only shot at playing in a World Series. So he conceived a gutsy plan.

Ray Oyler was the Tiger shortstop. The guy was amazing with the glove, but couldn’t hit a lick. I mean the guy could strike out in Tee-Ball. So Smith talked to Mickey Stanley and asked him if he’d ever played shortstop. He hadn’t. The two positions were very different.

MICKEY STANLEY

Nevertheless, Mickey Stanley was moved from outfield to infield just for the World Series. This made room for Kaline in the lineup (this was also long before things like the “designated hitter” and “”Money Ball”). By all accounts, Stanley accepted the role without complaint, demonstrating what it meant to be a team member. He played flawlessly—not a misstep or error.

It was a great example to young ball players, who for many years heard Little League coaches bark: “What do you mean you don’t want to play where I need you? Did Mickey Stanley complain when he was put at shortstop?” Coaches loved Mickey Stanley.

Not long after the ’68 season, baseball began to change. Free agency came, along with more money, money, money. Players moved around a lot more. They started building stadiums where you could actually see the game from any seat (go figure).

I still love baseball. But I wonder if the spirit of Mickey Stanley is anywhere to be found? Not only in baseball—but in America, in general?

The post A Forgotten Hero of October appeared first on David R. Stokes.

October 1, 2016

My Blog is Moving…;-)

[To all SUBSCRIBERS to my blog–I am moving to a new site: http://davidrstokes.com/blog/. Please go there to read my new post and sign up for future posts to be delivered to your email address. — DAVID R. STOKES]

Ashton is one of my six grandsons. He’s twelve, going on forty. Recently, I somehow persuaded him to watch my favorite movie with me. I told him that if after thirty minutes he didn’t like it, he could bail. [READ MORE at http://davidrstokes.com/2016/10/hooked-on-a-story/]

Hooked On A Story

Ashton is one of my six grandsons. He’s twelve, going on forty. Recently, I somehow persuaded him to watch my favorite movie with me. I told him that if after thirty minutes he didn’t like it, he could bail.

Of course, he loved it.

The film is the 1963 classic, The Great Escape—the sort of true story of an epic attempt at mass escape from a heavily guarded German prison camp during World War II. I was seven years old when it came out, so I never got to see it in all its full screen glory. I was first introduced to the story when one of the networks—this was way back when there were just three—aired the movie over two nights in 1967.

That was a big event in our house. My parents let me stay up late on two consecutive school nights to watch it. It is actually one of my fondest “warm fuzzy” family memories from my childhood. Mom made popcorn, and Dad did color commentary about what World War II was like. I pointed out that his war was Korea—but he held court nonetheless.

That was a big event in our house. My parents let me stay up late on two consecutive school nights to watch it. It is actually one of my fondest “warm fuzzy” family memories from my childhood. Mom made popcorn, and Dad did color commentary about what World War II was like. I pointed out that his war was Korea—but he held court nonetheless.

What makes a movie endure and remain popular half a century later? Well, certainly the cast is a factor. I mean, Richard Attenborough, James Garner, David “Ducky” McCallum (how old is that guy?), and the ultimate Mr. “Cool”—Steve McQueen—they surely played a role (pun intended) in the film’s contemporary and legacy success. But there must be more. I once saw a film that had Gregory Peck and Michael Caine in it, and it was a bomb.

It’s got to be the story itself.

The late Don Hewitt, long time producer of CBS’s staple 60 Minutes, was once asked about the secret of the news magazine’s staying power. He replied that the key was as old as the Bible and as simple as four words—“tell me a story.”

It is my experience—as a writer and speaker—that good stories begin with questions—Why? Why not? How? What if?

I am often asked how I came up with the story I tell in Camelot’s Cousin: The Spy Who Betrayed Kennedy. Well, it began with a question. In September 2011, I was invited to speak about my previous book, The Shooting Salvationist, to a forum at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. In the audience that evening was a writer who won a Pulitzer Prize for journalism in the early 1970s. His area of expertise was intelligence and the CIA.

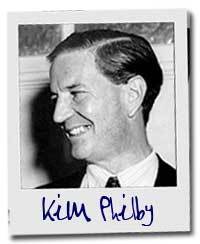

My host that evening invited this journalist to join us for a late dinner. It turned out to be quite an evening. Having always been fascinated by the world of intrigue during the Cold War, I picked this man’s brain. We talked much about the infamous spy, Kim Philby, who had been abruptly asked to leave the U.S. in 1951, under a cloud of suspicion. During our conversation that night the subject of materials he left behind was discussed. Philby had—according to his own memoir published in 1967—buried them in Virginia.

So, I asked the question—what if someone found what he buried? And what if something Mr. Philby planted beneath the Virginia soil pointed to other nefarious people and things?

So, I asked the question—what if someone found what he buried? And what if something Mr. Philby planted beneath the Virginia soil pointed to other nefarious people and things?

That was all it took—I was hooked on a story.

[CAMELOT’S COUSIN now has 312 Amazon Customer Reviews averaging nearly 5 stars each — the last said: “A real page turner. Written in a very comfortable conversational tone, it is a very successful historical novel. It puts together facts about some mysteries of WWII and the Cold War with a well drawn fictional story.”]

The post Hooked On A Story appeared first on David R. Stokes.