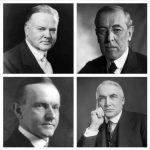

Of Coolidge, Harding, and Hoover

Happy President’s Day.

On August 2, 1927, President Calvin Coolidge had breakfast in the White House residence with his wife, Grace. He remarked to her, “I have been president four years today.” It was one of those quick, concise, directly-to-the-point sentences she had been used to hearing since they first met in 1905. It was also something the American people were familiar with, having nicknamed the 30th president “Silent Cal.” Mr. Coolidge ascended to the nation’s highest office following the sudden food-poisoning death of Warren Harding in a San Francisco hotel in 1923. The next year he won his own full term in a landslide election victory.

He had a meeting with reporters in his office that morning. Before fielding a few questions, he said, “If the conference will return at twelve o’clock, I may have a further statement to make.” Curious, but compliant, in those long-since-gone days of semi-civility between presidents and the press, the journalists found their way back at noon.

Shortly before than noon meeting, Coolidge took a pencil and wrote a message on a piece of paper. He handed it to his secretary with the instruction to take it to his stenographer and have him make a few copies. Ever the frugal man, he suggested that the brief statement could be copied several times on the same sheet, thus economizing on paper. He told the secretary not to give the note to the stenographer, though, until ten minutes before noon. Attempts by presidents to manage a news story are nothing new under the sun. Mr. Coolidge asked for the pages to be brought to him uncut. Before the reporters were admitted to the office, he took a pair of scissors and cut the paper into smaller slips. When he was just about ready, he told his secretary:

I am going to hand these out myself; I am going to give them to the newspapermen, without comment, from this side of the desk. I want you to stand at the door and not permit anyone to leave until each of them has a slip, so that they may have an even chance.

The handwritten note from the president said, simply: “I do not choose to run for president in nineteen twenty-eight.” Though the classic play The Front Page (currently in revival on Broadway) was still a year away from being first published and produced, the rush from the President’s office that day comes to mind as the reporters rushed out to find telephones.

Calvin Coolidge could have been re-elected if he had wanted the job for another term. His anointed successor, Herbert Hoover, went on to win big in 1928, though it is clear that Coolidge was less-than-enthusiastic about him. It is one of those curious “what ifs” of history; would Coolidge have dealt with the coming of the Great Depression better than his successor?

Historians tend to bunch the three Republican presidents of the 1920s—Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover—together in a way suggesting they were identical triplets separated at birth. But there were many differences—some subtle, some not so much.

Herbert Hoover, all of his speechifying about “individualism” notwithstanding, was not the fiscal conservative many today make him out to be. As Amity Shlaes pointed out in her book, The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression, a few years ago, Mr. Hoover had a strong penchant for interventionist policies. He “could not control his own sense of urgency,” and “liked to jump in, and find some moral justification for doing so later.” In many ways, he helped to turn a recession into the Great Depression “by intervening in business, by signing into law a destructive tariff, and by assailing the stock market.”

Ironically, when closely examined, Herbert Hoover’s approach to economics had more in common with his successor (FDR) than it did with the two men preceding him in the White House.

Warren G. Harding generally ranks in the bottom five when studies are done about the effectiveness of our chief executives. In fact, Hoover fares better than the man from Marion, Ohio. This is largely due to the scandals that came to light after his untimely death—the affair known as Teapot Dome. Also, some of Mr. Harding’s personal behavior was less than presidential. That said, he might have been a saint on that front compared to a few future chief executives.

What is usually missed about Harding is how effective he was on the issue of the economy. When he assumed the presidency in March 1921, he inherited a mess. Woodrow Wilson had expanded the role and size of government dramatically, incurring a $25 billion-dollar debt. He also had authoritarian tendencies, even imprisoning a few political enemies (e.g., Eugene V. Debs, the perennial Socialist presidential candidate).

The truth is, the economic problems in the 1920-1921 depression were actually worse in many ways than the Great Depression a decade later. But the earlier downturn didn’t last as long. Warren Harding cut federal spending and lowered taxes, and in less than two years the number of unemployed in the country fell from 4.9 million to 2.8 million. The trend would continue for a few years, falling to a rate of 1.8 per cent by 1926 under Coolidge. Harding also set the political prisoners free, even inviting Eugene Debs to the White House. Frankly, the twentieth president was highly-effective and very popular before his untimely (and some whisper, suspicious) death. Most of the scandalous stuff came out later— sort of like what happened after President John Kennedy died.

By the time Calvin Coolidge became president upon the death in 1923, the country enjoying a time of optimistic prosperity. He was a fiscal conservative who tried his best to stay out of the way. He believed that the government functioned best as a referee—not as an active player in the economic game.

After he was elected in his own right, Coolidge told the nation in his March 4, 1925, inaugural address:

I want the people of America to be able to work less for the government and more for themselves. I want them to have the rewards of their own industry. That is the chief meaning of freedom. Until we can re-establish a condition under which the earnings of the people can be kept by the people, we are bound to suffer a very distinct curtailment of our liberty.

His decision not to run in 1928—at the height of his popularity—puzzled many. But Coolidge understood the nature of leadership and its seductions. He explained it this way:

It is difficult for men in high office to avoid the malady of self-delusion. They are always surrounded by worshipers. They are constantly, and for the most part sincerely, assured of their greatness. They live in an artificial atmosphere of adulation and exaltation, which sooner or later impairs their judgment. They are in grave danger of becoming careless or arrogant.

I believe that had Calvin Coolidge decided to run again in 1928, he would have responded to the initial shock waves of 1929-1930 differently than Herbert Hoover did. And maybe, just maybe, the Great Depression would not have lasted so long. At any rate, Mr. Coolidge died suddenly on January 5, 1933, after Hoover had been badly beaten by Franklin Roosevelt. He did not live to see what a prolonged depression looked like, but one suspects that he would have ventured an opinion or two.

And his words would have been brief and directly on point.

The post Of Coolidge, Harding, and Hoover appeared first on David R. Stokes.