Julia Hotz's Blog

August 19, 2025

The three words that changed how I view the world

Three years ago, sitting in the courtyard of the social prescribing birthplace, I was interviewing the social prescribing godfather, Professor Dr. Sir Sam Everington OBE, when he gave me the best advice: “Assume it’s possible.”

For Sam (he says we can call him that), that’s the mantra that helped social prescribing go from what it was to what it is: What began in the 1990s as a doctor doling out yoga class “prescriptions” in an old London church has become an unstoppable global movement spanning 32 countries.

He didn’t ask for permission. He didn’t balk at the potential of bureaucrats shutting him down. He didn’t pay mind to skeptics who thought getting fellow doctors, community groups, and insurers on board would be impossible.

He just assumed social prescribing was possible. And he was right.

I’ve thought about Sam’s advice a lot the past year, as I watched The Connection Cure, my book on social prescribing hit the shelves, and see the concept gain new attention on podcasts, radio shows, TV spots, articles and op-ed pages.

Whenever an out-of-the-box idea gains steam— especially in healthcare, especially in the United States, and especially in this weird political moment—there will always be naysayers. In comment sections and book reviews, I’ve heard just about every reason why social prescribing is impossible: Insurance companies would never pay for it. Medical schools would never teach this. Doctors and therapists are too busy. Hospitals are too worried about their own profit. Patients are too addicted to quick fixes.

But then, in the background and on the frontlines, people are quietly assuming the opposite: “Social prescribing is possible - and I’ll show you how.”

In the past year, I’ve seen social prescribing get buy-in from a wide range of voices — from the queen of science podcasts Alie Ward to the (literal) King of England, from CNN’s famous Michael Smerconish to reality TV’s famous Kourtney Kardashian. I’ve seen the former U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy make the case for it in his “Parting Prescription for America” and the World Health Organization do the same. I’ve seen the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the Department of Veteran Affairs, and the National Endowment of the Arts all renew their investment in social prescribing. And across the nation, I’ve seen more than 40 social prescribing programs emerge.

This past year has seen lots of other firsts for the movement, too: Massachusetts Cultural Council launched the nation’s first statewide arts prescription program. New Jersey Performing Arts Center expanded their partnership with Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield, the first insurer to cover social prescriptions. San Mateo, California became the first county to declare loneliness an emergency, and plans to include social prescribing as part of its response. The “Arts for Everybody” campaign hosted a first-of-its-kind one day celebration of arts and health across 18 cities and towns.

But this, I know, is only the beginning— and this is where you can help.

For starters, you can help social prescribing get in front of a 500,000+ strong audience at SXSW by voting for our book talk and panel by August 24th. You can help boost awareness by reading The Connection Cure and leaving a review on Goodreads and Amazon. You can join our next virtual all-hands meeting on September 10th to help build local action.

But most importantly, you can continue to assume social prescribing is possible — and let people know why. From the GenZ NYC transplant finding a running club to the widow in his 80s finding an online storytelling circle, I’ve heard hundreds of stories about the magic that happens when people are reconnected to what matters to them. And if there’s one thing I’ve learned in writing The Connection Cure, it’s that stories have the power to change hearts and minds. Even when everything else seems impossible.

This was cross-posted on the blog of Social Prescribing USA.

May 6, 2025

What would your younger self tell YOU over coffee?

Me and my dear Aunt Fran making “puffers” — wet paper towel balls with food coloring. Circa 1996.

Me and my dear Aunt Fran making “puffers” — wet paper towel balls with food coloring. Circa 1996. Three months ago, there’d been a big TikTok trend where people were “meeting their younger selves” for coffee. Inspired by a poem, the prompt would invite Current You to offer some words of wisdom to Younger You -- a 30 second confessional, usually set to a Mazzy Star track and a montage of grayscale coffee shop scenes.

Thanks for reading The Connection Cure! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

More often than not, Younger You gets told a version of this: It all works out. The dead-end job. The not-quite-right relationship. The painful friend breakup. “Be present, and don’t worry so much about the future,” the Older Yous urge.

This seems reasonable. After all, we can never have enough reminders of how cosmically significant we are, or how rarely our assume-the-worst, they-definitely-hate-me, I’m-going-to-die-alone delusions actually materialize.

And yet, as true as this all is, the trend doesn’t tell us how we actually worry less, and become more present. Nor does it reflect on the other side of this question: What would your younger self tell YOU over coffee?

This, I think, is a missed opportunity.

To be clear, I’m not talking about 18-year-old you, or even 28 year-old you. But 8-year old you—

covered in dirt clobs and colored markers, preoccupied by playground games and sand castle construction? They, I think, have the wisdom we could really use.

8 year-old you wouldn’t think to tell you not to overthink; they’d be too busy using their hands to spend time in their heads.

8 year-old you wouldn’t shame you for second guessing yourself; guessing is the only thing they know (“Are we there yet?”). And that’s just fine; when you’re a kid, uncertainty is the rule, not the exception.

8 year-old you is under no pretenses that digging up bugs or devising dance routines is any less worthy than poring over excel spreadsheets and hoping this email finds you well. (38 year-old you might be shocked to learn AI is more likely to come for the latter.)

But maybe most importantly, 8 year-old you doesn’t need a self-help bookshelf or blue checkmark influencer to remind you to be mindful—a state, defined by the concept’s originator, Harvard psychologist Dr. Ellen Langer as “what you’re doing when you’re having fun.”

I don’t mean to make it sound so simple, or suggest all of our 8 year-old selves had it so easy. That’s especially true today (New research finds kids today are much less happy than kids thirty years ago.)

But that only proves my point. This is not about age; this is about mindset. The older we get, I think, it becomes more important for us to unthink. To work less and play more. To abandon our false sense of control, and pick fun.

I was reminded of this last week, as one of the unlucky Newark airport passengers stranded with a seven hour delay. Most adults, myself included, sat around and huffed—groaning into the ambient lofi-lined halls about all the plans they’ll miss and bookings they’ll have butchered, trying desperately to get on alternative flights.

As hour six became hour seven, I finally gave up and pulled up a seat next to the only Newark airport establishment that isn’t trying to sell me something: the indoor playground.

The parents encircling the playground sat glued to their phones—furiously scanning for flight updates and filling out compensation forms. “For the love of God, can’t we just get there?” their heavy undereye-bagged faces screamed.

But the kids—who’d been there just as long as the parents —couldn’t be bothered. They were

preoccupied with slides and ladders. Ropes and mushroom-shaped obstacles. Tag games and new airport friends.

I sipped my coffee and watched, knowing I’d just met my younger self for coffee. And without saying anything, they told me everything I needed to know.

---

If you haven’t done so yet, please order and review my book, The Connection Cure! This helps to spread the word about the power of social prescribing.

For the first five people who send me a screenshot of their review, I’ll mail you a customized social prescription :)

An indoor playground in Barcelona airport.

An indoor playground in Barcelona airport.Thanks for reading The Connection Cure! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

February 20, 2025

“Why sh*t not working—and how can we fix it?”: Announcing the first social prescribing all-hands meeting

Last weekend, my friend Raj showed me a clip that (temporarily) restored my faith in politics: in it, council member Chi Osse breaks down the chronic dysfunction within New York’s subways and points to other cities (Istanbul! Berlin! Tokyo!) with better and cheaper systems. Then, the kicker: he holds himself accountable to “start building again.”

Osse’s series—aptly named “Why sh*t not working—and how can we fix it?”—asks the one we’re probably all asking right now, when civic life feels like a dumpster fire, and when politicians seem more interested in dissing the other guy than doing anything about it.

But here’s the thing: behind the doom-and-gloom headlines and social media riffraff, people are fixing sh*t. My nonprofit, the Solutions Journalism Network, has nearly 17,000 stories to show for it. By reporting on what *actually* works to tackle sticky issues, we’re reminded: problems are solvable when we focus on policy, not politicians. Human-felt results, not lip-service promises. “Hope with teeth”, not doom-and-gloom.

That’s been especially true for social prescribing —a fix for some of the biggest problems in health, healthcare, and our culture. In 2024, the same year The Connection Cure hit stands, the United States made some major strides: New York launched its 1115 waiver program to build “social care networks” and create partnerships between doctors and community orgs. Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Oregon reformed their 1115 Waivers, too, allowing state Medicaid agencies to cover Indigenous health care practices, like dance and music therapy.

There were a lot of firsts along the way. Massachusetts launched the nation’s first statewide arts prescription program, with more than 300 cultural organizations on board. New Jersey, home of the first social prescription pilot to partner with an insurer, got NEA funding to expand. San Mateo, California, after becoming the first country to declare loneliness an emergency, is investing in social prescribing, and Jefferson County, Montana is including it in their health plan, too. Tennessee State Senator Shane Reeves wrote an op-ed calling to expand social prescribing. And the outgoing U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy even wrote a “parting prescription” calling on healthcare to invest in community.

But beyond government measures, a grassroots movement is growing, too. On July 27, 18 politically and demographically diverse cities and towns hosted an epic one-day celebration of the medicinal value of the arts (for everybody!), which led to more funding. Social Prescribing USA, the nonprofit home of the movement, grew its community of practice by 400%, and is documenting the spread in real-time. And during my own book tour to some three dozen U.S. cities and towns, I’ve met people from all walks of life—artists, doctors, nature-lovers, retirees, high school students, volunteers —all asking the same questions: What can I do? How can I help?

Which is why, on March 19th, this #SocialPrescribingDay, I’m co-hosting a virtual “All-Hands” meeting to turn that “how-can-we-fix-it” energy to action. With Social Prescribing USA, we’re calling on EVERYONE to take one concrete action to help integrate social prescribing in our healthcare systems, community institutions, and discussions of health and wellness.

Especially now—during President’s week, Black History Month, and a political moment like no other—we remember the call-to-action from the late great John Lewis, who challenged “each one of us in every generation to do our part.” “If we believe in the change we seek,” he wrote, “the responsibility is ours alone to build a better society and a more peaceful world.”

Because here’s the other thing: It’s true that greed, groupthink, discrimination, and dysfunction are part of our American story. But generosity, grassroots mobilizing, outside-the-box-thinking, take-it-to-the-streets action are, too. And after all, whether you felt it through Kendrick Lamar’s halftime show or Bob Dylan’s biopic, there’s a spirit of revolution among us. And that revolution will not be televised:

The revolution will put you in the driver’s seat.

The revolution will be live.

Will you join?

Thanks for reading The Connection Cure! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

February 2, 2025

This neuroscience trick makes time feel longer—and better

Unless you’re Punxsutawney Phil, or Bill Murray, you might be forgetting today is Groundhog Day.

Throughout my childhood, GroundHog Day meant getting in unnecessarily heated debates (good practice for adulthood!) about whether or not the titular groundhog would see his shadow

But as an angsty 31-year old, it marks another occasion to contemplate my usual angst about time— why we feel we never have enough of it, and why we’re also so bad at spending it on what matters.

You see, this otherwise random holiday has become synonymous with the plot of the 1993 classic, featuring a cranky weatherman inexplicably reliving GroundHog day over and over again.

It summarizes how lots of us feel this time of year. And in our defense, the winter months don’t help. Those New Years resolutions we made for January 1st require repetition on January 2nd, 3rd, and 4th. Those emails we ignored in 2024 require copy-paste-template-answering in 2025. That chili we made on Sunday does taste just as good on Wednesday.

Couple all this with the cold weather, the current political sh*tshow, and the seven hundred sicknesses going around, it’s easy to understand why we seek familiarity at the expense of variety. We’re too exhausted to do much else. And besides, when our wellness culture obsesses over “atomic habits” and morning routines, repetition feels like a virtue.

But then, when I get pangs of getting-older-anxiety, or reminders of how tragically short life is, I wonder: what the hell am I doing? Why am I auto-piloting my days away? Why do the hours feel long but the weeks blur together and the years fly by?

Dr. David Eagleman, a Stanford neuroscientist, has good news. He reminds us “time is not the unitary phenomenon we may have supposed it to be” and points to the ways we perceive it differently depending on the novelty of our experiences. Did you ever wonder why you remember your first day of work, but not your 564th? Or why you remember your first meal with your partner, but not the 13,456th? Or why, if you’ve ever been in a car crash, you remember every detail and feel time stands still?

Eagleman explains this through neuroplasticity; because our plastic little brains are tasked with making sense of the world, they have to adjust their neural circuitry every time they face new sensations.

Laying down neural circuitry takes work. And humans happen to be really good at it; it’s why we’ve survived bear attacks and pandemics. It’s why people with Alzheimer’s—whose perception of the world gets shattered every day—find ways to rebuild that world each time.

It’s also why kids feel like time is infinite; when every day brings a new first —a first snow, a first bike ride, a first school, a first friend— kid-brains work hard to create new pathways. In return, they feel time as rich, and memorable, and slow (“Are we there yet?!”).

But as we get older, when GroundHog Day ourselves into the same sensations, environments, and routines, there’s no growth, and our brain model stops adjusting. And as a consequences, Eagleman says, time tends to feel like it speeds up as we get older.

Liz Moody, one of my favorite podcast hosts (who had me on her show last month), has a hack to counter this. She calls it the Novelty Rule—a way to “slow down our perception of time by increasing novel experiences.” Liz aims for one novelty activity each a week, and points to lots of examples: Making a new recipe. Playing a board game. Calling an old friend.

Even small novel experiences “make our brain more primed to remember that week, instead of letting them blur together,” Liz says. And after all, any activity can become novel if you bring another person (hint hint).

When I test the Novelty Rule on myself, I know Liz is right. If I think about the days I most remember from this time last year, it’s certainly not the days spent in routine; It’s the days spent deviating from it: The day the Quiltwomen dressed in black turtlenecks and participated in an emo JCPenney photoshoot for a very pregnant Kate. The night we threw Kiera a “funeral-themed” 30th birthday, casket and all. The hours spent running in rain and falling in the mud with Dan to watch bikes race through rural Belgium.

This year, the groundhog gave us six more weeks of winter.

But really, he gave us all the time in the world.

You can check out conversation I had on The Liz Moody Podcast and some of my other interviews here.

Thanks for reading The Connection Cure! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

January 1, 2025

A better alternative to New Year’s resolutions

It’s the most wonderful time of the year—right before it’s the most restrictive.

Like many of you, I’ve spent the last couple of weeks subsisting entirely on a diet of butter, cookies, butter cookies, and every imaginable configuration of bread and cheese. I’ve put on real pants exactly three times. And last Thursday, I clocked sixteen hours on the couch.

And yet, also like you (I’m guessing), I write these off as last licks before beginning what’s sure to be my healthiest year yet.

January 1st kicks off a series of unoriginal austerity measures: Cutting out gluten and dairy and renewing my vows to vegetables. Cutting out sedentary pleasures and adopting a strict regimen of daily squats and sit-ups. Cutting out distractions and filling my free hours hustling to sell my book. Cutting out going out and spending more nights hibernating in—practicing hydration, sleep, skin care, and all of the trendy wellness virtues.

When I make these new year’s resolutions—ones I typically quit by mid-February, I always picture a version of my future self. She’s unrecognizably fit and fashionable. She’s got a crisp haircut, defined abs and invisible under-eye bags. She’s got fancy footwear and glowing cheekbones. She looks healthy, but is she?

Especially this time of year, when everything feels like an ad for finance planners and weight loss apps, it’s easy to think about health as the sum of our nutrition, fitness, financial security, and hours slept. But after spending five years investigating, I've come to define health as the sum of our connections. It’s the extent to which we know and live by what matters to us.

There’s some hard data as proof. Large-scale reviews associated the strength of our social relationships and our purpose in life with increased longevity and lower risk of premature mortality. Another analysis associated having a hobby with fewer depressive symptoms and higher levels of wellbeing. And the eighty-year-plus Harvard Adult Development Study found close relationships are the strongest predictor of our long-term health and happiness.

We know this from first-hand experience, too. Everybody who made a 2024 highlight reel knows their peak moments were marked not by trim bellies, but belly laughs. Not by money made, but memories made. Not by the glow of watching our own mirror’s reflection, but the glow of watching others’ milestones.

And yet, come January 1, we forget these intuitive truths, even as we so easily practiced them one week earlier. We cast aside shared joy as indulgent, and treat the isolation of restriction as virtuous. We get collective amnesia and realize, too late, that we were the healthiest not when we cut out connection, but when we embraced.

It turns out there’s a way to find the best of both worlds, and it starts with a better alternative to new year’s resolutions.

We get some hints from history, where our ancestors’ New Year’s resolutions looked more like community-vows than rites of self-discipline. 4,000 years ago, the Babylonians celebrated new year’s through Akitu, a 12-day festival designed for planting new crops and renewing promises to the gods. The Romans similarly used January—named after two-faced Janus, the god of doorways—as a time to both reflect on the old year, and promise good conduct in the new year. Some Christians still use New Year’s Eve as a time to gather, sing hymns, and together resolve to do better.

Call me ancient, but I think there’s some profound wisdom here—to ditch aesthetic causes, and focus, instead, on spiritual ones.

To be clear, I don’t mean spiritual in the God-y sense, per se; I mean spiritual as causes that “relat[e] to the human spirit… as opposed to material or physical things”. In other words, if we really want to be healthy, we should treat resolutions as things we do with other people. As something more like social prescriptions.

Why? Well, for starters, you might actually succeed; though surveys suggest only 8 percent of us successfully stick to New Year’s resolutions, social prescriptions for activities we find fun and meaningful are more likely to stick. It also helps that these social prescriptions, like salads and sleep, are objectively healthy. Their most common ingredients—movement, nature, art, and service —have been linked with reduced inflammation and rumination, less of the stress hormone cortisol, and more activity within pathways of mood-boosting neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine.

And yet, what probably helps most of all is the way they come with accountability. Unlike New Year’s resolutions, social prescriptions don’t require a thick wallet or iron self-discipline to help us stay true to our word; they simply require the encouragement and shared mission of other people. In other words, e don’t have to buy another gadget to help us exercise or manage our stress; we can ask our doctors to prescribe us (or prescribe ourselves) a spot on a local sports team or art class that expects us there each Tuesday.

It may sound corny, but in a year where $40,000 Equinox memberships were named a defining health trend, it’s worth reminding what Sam Cooke says: “the best things in life are free.” True health and wellness is shared.

And so, maybe, instead of thinking about New Year’s resolutions as a list of bad things we cut out, we should think about them as an invitation to bring more good things in. A chance to renew our vows to what matters to us, together.

But don’t take it from me: take it from your future self. Come January 1 2026, when you look in the mirror, you’ll find yourself rested and fit and glowing not because you stuck to a list of restrictions, but because you were having too much fun to remember them. You’ll be healthy not because you ditched the most wonderful times, but because you built your days around prolonging them.

Want to give someone (or yourself!) The Connection Cure—the world’s first book about social prescribing?

Enter the Goodreads book giveaway! And if you haven’t done so yet, please remember to leave a Goodreads/ Amazon review!

Thanks for reading The Connection Cure! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

August 16, 2024

5 science-backed mood-boosters

If the subject line has you thinking you’re about to read some affiliate-link-filled ad for essential oil diffusers and de-stressing seltzers, I promise you: this is not that.

In fact, I wrote this newsletter and its namesake book to explore options that go beyond that—the industry of wellness, built on individual products—and amplify this—a culture of wellbeing, built on [socially-prescribed] community activities.

Thanks for reading The Connection Cure! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I wrote it to help us realize, now, while we’re still alive, what we’ll all remember on our deathbeds: how what really mattered were the joys we experienced, the meaning we discovered, and the relationships we built—true wellbeing sources that money can’t buy.

And yet, I also wrote it because actually doing that — practicing that deathbed wisdom— is really f&@king hard.

I’m proof. Yesterday, after discovering my new refrigerator stopped working, my food spoiled, and my kitchen became home to a vicious family of flies, I admit, I didn’t think to myself, “I could really use a social prescription right now.”

Instead, after shouting some expletives, calling PC Richard & Son as if they were 9-1-1, decorating my home with fly glue ribbons like they were party streamers before inevitably walking into a ribbon and getting fly glue stuck in my hair, I spent the the day ruminating: sulking in my glue-filled pity party, doom-scrolling and little-treating myself, convinced I had suffered the gravest injustice imaginable.

Our culture makes it easy to do this: To ruminate and isolate and make our bad moods worse. But who can blame us? Especially when we’re faced with the more mundane everyday mood-kills—Sissyphian inboxes and infinite media feeds, piled-on finances and endless errands, passive aggressive texts and tedious to-do-lists, social prescriptions feel like another chore; why would we “prescribe ourselves” a community experience, like dancing or birdwatching, when our time feels so limited as is? If we can get new age products that *optimize* for *peak satisfaction*, why would we choose age-old, communal pursuits…activities that might bring us some wellbeing, sure, but might bring us some discomfort, too (and, at the very least, require us to get off the couch)?

Except, here’s an inconvenient truth: these age-old community activities actually do help us feel better, and they’re probably more effective and long-lasting than that mood-boosting candle is.

You probably already know this. Have you ever noticed how sh*tty moments feel less sh*tty when we have some other moment to look forward to after? Or how rejections feel less painful when we have other sources of meaning we can rely on? Or how bad moods feel less bad when we have people we can vent to/ laugh about/ problem solve them with?

We also know there’s a difference between wellness and wellbeing: Between what gives us pleasure and what gives us joy. Between how our jobs’ conception of our purpose and what we see as sources of meaning. Between a small-talky shallow acquaintance and a 3am-fear-sharing, true-weird-self-accepting friend.

Social prescriptions for community activities can help deliver these deathbed virtues. But even though we know this, intuitively, it’s hard to remember them, practically. When presented with some mood-killer—a breakup, a layoff, a loss, or some other stress-sadness-worry-anger-loneliness-inducing event— it’s much easier to pick a quick fix.

But what if it were easier to pick the community activity? What if we could find the right “precision” medicine for our precise slice of bad mood? What if social prescriptions for wellbeing were as practically accessible and culturally sexy as products for wellness?

Enter the Crowdsourced DSM—the before-and-after testimonies of people in The Connection Cure (including yours truly) who’ve been through its five featured medicines—movement, nature, art, service, and belonging, when they deal with five different kinds of bad mood— sad, overwhelmed, anxious , grumpy, and lonely. The website also gives us practical options of free or donation-based local community activities we can “prescribe ourselves” when we pass through these five moods.

This, too, is part of the social prescribing movement. For as great as it would be for the policy and insurance overlords to magically make social prescriptions universally available in healthcare, it’s going to take all of us to see them as essential to our health. It’s going to take all of us to support not just an industry of quick-fix wellness, but a culture of long-lasting wellbeing. And it’s why I couldn’t be more thrilled that some of the biggest platforms in wellness—like Kourtney Kardashian’s POOSH, Gwentyh Paltrow’s GOOP, Jason Wachrob’s mindbodygreen and a bunch of other wellness podcasts—recently endorsed social prescriptions as part of the equation of what makes us well.

I don’t imagine these five “mood boosters” will be cure-alls. And hey, if you want to sulk in your glue party, who am I to judge? But I hope these guides, and the big wellness names supporting them, help you practice the deathbed wisdom you already know: your bad mood won’t last forever. And there are ways to feel better, faster, for longer, together.

Come see me talk about social prescribing with some really brilliant people in in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Rutland, Washington D.C, Philadelphia, and more!

And, p.s. speaking of remembering “what matters to you?”, here’s a chance to win your very own “Rx: Connection ‘What matters to you?’ notepad and social prescription pill bottle (see below)! What better way to remember social prescribing than to have physical reminders on your desk?!?

Here’s how you can enter to be one of five winners:

Leave a review of The Connection Cure on Goodreads/Amazon (only if you’ve actually read some of it! We want genuine reviews only :))

Email back a screenshot of proof, and your best mailing address!

Thanks for reading The Connection Cure! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

June 11, 2024

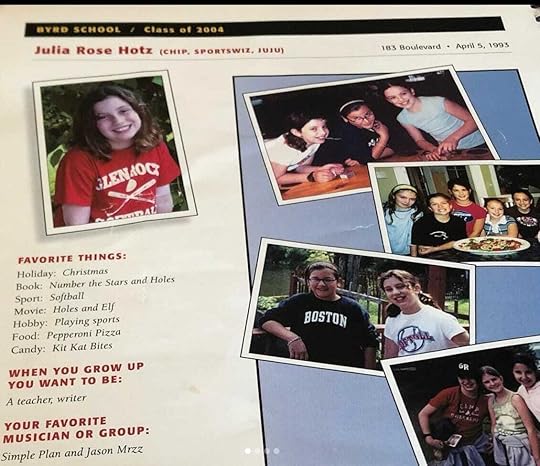

A letter to my 5th grade self on what made her dreams come true

Dear 5th grade Julia,

There are so many things I wish I could have told you when you wrote this yearbook bio circa 2004. (1) Kit Kat Bites will tragically go extinct, (2) the self-administered haircuts were a no-go, (3) approximately 0 people will call you “sportswiz”.

But more than your mistakes, I’d tell you one thing were right about: today, on June 11th, your book, THE CONNECTION CURE, will hit the stands in the US and the UK. You will officially become a “writer” — something you could have only dreamed about— and it will be with your dream publisher at Simon & Schuster.

Of course, you didn’t achieve this—or any bit of good fortune—alone. You’ll learn, even more with time, that your success is a product of the people who believed in, listened to, and unconditionally supported you.

In fact, this will be the core thesis of your book: our health is a product of our social environment.

This is not a new idea: ancient thinkers have proven it time and again. But your book will be among the first to report on the rapidly growing practice bringing that idea to life: social prescribing.

Some social prescriptions are for the activities that you take for granted now, fifth grade Julia: Playing sports. Swimming in the ocean. Exploring nature. Writing poetry. Joining a book club. Singing in a choir. Volunteering for the park cleanup. Sharing meals with neighbors.

You won’t appreciate it then, but you’ll realize, when you repeat these activities twenty years later as you report on social prescribing, that you were actually chasing some of the best kinds of medicine: Childlike wonder. A sense of joy. A search for meaning. And you were chasing these medicines with other people — building the kind of relationships proven to help you live a long, healthy life.

Anyway, you’ll have a blast taking these social prescriptions again—finding them medicinal for your occasional bouts of sadness, distraction, worries, frustration, and loneliness that comes with the human experience. And as you write this book, you’ll believe more and more in everyone’s right to have social prescriptions, so that they, too, have the medicine they need to make the their 5th grade dreams come true.

—-

To my family, friends-turned-family, colleagues-turned-friends, and wonderful connections all around the globe: thank you for demonstrating the thesis of this book firsthand.

Through it all , you’ve been MY social prescription. And as we celebrate the release of The Connection Cure today (some ideas to do that here), know that it exists thanks to you.

Thanks for reading The Connection Cure! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

May 29, 2024

The best medicine for “getting older anxiety”

Last month, I celebrated my 31st birthday, when, in lieu of the usual Egg Toss—corralling loved ones to *literally* toss eggs in competitive pairs, I spent it corralling them to belt Bonnie Tyler on repeat— paying homage to the Total Eclipse and to my original “Karaoke Party” from two decades earlier.

Each year, I pick a new kid-like activity. And this year, after texting a friend my (apparently) annual birthday blues symptoms, I finally realized why—when she pointed out I might have a mild case of “getting older anxiety.”

It never occurred to me that somebody wouldn’t have this. The idea that growing older means losing the joys of being younger feels embedded in every corner of our culture. Just think, for instance, about the biggest Boomer music hits: There’s the Bruce Springsteen song about “glory days” gone by. There’s Bryan Adams’ hit about the “summer of 69” being the best days of his life. And the worst is John Mellencamp’s little ditty about Jack and Diane: Life goes on long after the thrill of living it’s gone.

Eight year-old me found those lyrics terrifying.You mean to tell me there’s a point at which life will stop being this fun? That my glory days and best days will happen in my youth? That I’ll wake up one day and the thrill will be gone?

Birthday bring out the angsty eight year-old in me that still grapples with those questions. And they also bring out the part of me in denial about getting older at all— the part that genuinely believes this whole ruse of paying taxes and having a day job is really just a field trip from a rigorous schedule of the everything and nothing that defined my younger years: ambling around backyards and basements, swimming in scum-topped ponds and “treasure hunting” in forests, stomping and screaming the lyrics to Mr. Brightside as if my life depended on it.

When I open up my eager eyes, I see the more jilting reality: I am older. And so are all of the people who’ve made so thrilling, so far. My childhood friend Kate —who I picture, still, as the “child” who used to spend Memorial Day Weekend cupid shuffling at the Jersey Shore, is now nursing a (beautiful!) child of her own. My college friends—who’ve made New York City and its many park-turned-egg toss arenas feel like home— now find themselves covertly scrolling Zillow listings in the suburbs, dreaming about their new homes. And my parents—who’ve joyfully supported the Karaoke Party and every kidlike activity since — recently bought a new car, and reminded the dealer that “it would be their last.”

The most distinct thrill of being younger, I’ve realized, isn’t unlimited time for kidlike activities; it’s feeling like your time with the human co-stars of those activities is unlimited, too.

It isn’t, of course. The bleak charts showing who we spend time with as we get older confirm: with every passing decade, we spend less and less time with the friends and family who cemented our early years.

And so, in the face of this unfathomable fact, we do everything we can to distract ourselves from it. We toss eggs and belt songs to remind us of how ageless we felt when we first did those things. We binge the shows, the snacks, the music and the movies of our childhood to give us comfort in adulthood. Instead of confronting a potentially lonely future, we seek the comfort in the nostalgia of our past.

There’s an evolutionary-rooted reason why we do this, according to psychologist Krystine Bacho. Derived from the Greek for the pain of (“algos”) returning home (“nostos”), nostalgia helps us cope with loneliness, since it reminds us of our relationships with other people, and “meets a cognitive need [by encouraging] that things will get better because they’ve been good before.”

But even though nostalgia can be a helpful coping mechanism, it can also be harmful, if overused. Early records considered nostalgia a disease, a kind of “love sickness,” in which symptoms included “longing” and “melancholy”.

So, what’s the cure?

The 19th century French doctor Hippolyte Petit puts it bluntly: "Create new loves for the person suffering from love sickness; find new joys to erase the domination of the old."

In other words, take the time you’d spend longing for the thrills of your past, and redirect it towards finding new thrills in your present.

After all, just as we don’t have unlimited time with loved ones, we don’t have unlimited time ourselves. Zero people, to date, have escaped the one truth that unifies all of us: We’re all going to die.

In 1580, the French philosopher Michel de Montaigne wrote an essay on this blunt fact, calling us to embrace“inevitability of death”, and pointing to the ancient Egyptians, who’d display skulls and skeletons to remind them of this. The ancient Romans allegedly made a big show about death, too, and used a now-famous catchphrase—“Memento Mori”, or “Remember death” to help them practice it. Mexico’s still-thriving tradition of día de Muertos similarly serves to remind us: death is a part of life.

Most modern Americans aren’t as good with these rituals. But new books remind us of the underlying theme: how remembering death can help us create a more fulfilling life. Jodi Wellman’s aptly-named Four Thousand Mondays (You Only Die Once) gives us practical tools to make it to death with no regrets. Dr. Meg Jay’s Twenty Something Treatment suggests people dealing with the uncertainties of growing older will find “life is the best medicine.” And my own book, The Connection Cure, echoes both books’ core messages: to get out of our own heads and keep from living in the past, we need to connect with the people and activities that make us feel present. We need to “create new loves.”

That’s what I’m trying to remember when I feel pangs of getting older anxiety. The angsty eight-year old in me may have been on to something. But the thirty one year-old in me could offer her some perspective— the kind that only comes with age:

I’d tell her to enjoy her present, and the people making it so lovely now. I’d tell her, candidly, that day jobs and babies, cross-state moves and the circle of life, will make it harder and rarer to see those people. But I’d tell her, too, that she’ll find new co-stars— new ways to“return home.”

And then, when the old co-stars come back for a reunion special —at weddings, on birthdays, for rare nights on the town— she won’t be wondering if her glory days are behind her.

Instead, while she’s stomping and screaming to Mr. Brightside—just like she did twenty years earlier—she’ll realize: the thrill will never be gone. It will live on as long as she does.

If you liked this post, consider forwarding to a friend, and ordering the eponymous book, The Connection Cure, from your preferred retailer here

Thanks for reading The Connection Cure! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

May 26, 2024

Joe McGivney and the Jar

[From The Connection Cure archive — originally published in 2021]

Five years ago, armed with an empty olive jar, some dirt, and a bunch of rocks and pebbles, I taught my students the only lesson that would ever really matter.

They wouldn’t know this then. And neither would I—until I remembered the lesson last April, when the only person I’d ever known to actually live by it had died.

The lesson takes just three minutes: open the olive jar and fill it with the big rocks. Ask the students if it’s full (They say ‘yes’). Then add the pebbles, close the jar, and shake until they fill the rocks’ empty-spaces-between. Ask the students if the jar is full (They say ‘yes’). Then repeat with dirt. Students, again, agree it’s full.

The kicker comes when you empty the jar—the rocks, the pebbles, and the dirt— and start over. This time, put the dirt in first. Ask the students if the jar is full (They say ‘no’). Then add the pebbles (Still ‘no’). By the time you try to add the rocks, there’s no room left in the jar.

Then, in your best soapbox tone, tell the students how the rocks represent the most important things in their lives: the people they care about. The pebbles represent things that matter, but less: work, hobbies, and passions. And the dirt is everything else: ‘likes’ and ‘views’ and the stock market and BravoTV all of the small stuff that sucks our attention, even when we know it doesn’t matter. “If you put the dirt in the jar first, there’s no room for the rocks,” you tell them, still soapboxing. “But if you’ve got the ‘rocks’ and lose everything else, your jar is still full.”

——-

Of course, the lifelong work of following the jar lesson is much harder than teaching it. It’s not that we don’t love our rocks, and we’re reminded just how much during breakups and birthdays and pandemics. But the day-to-day work of cherishing our rocks doesn’t come naturally, when most of our activities and attentions point us to dirt; ‘feeds’ and hacks and packed-calendars that instruct us to save the cash and the calories and the hours so that we have more freedom and more time, until something or someone shakes our jars and reminds us to ask: what are you saving it for, anyway?

Joe McGivney knew. And he spent his life—or at least each Tuesday—helping others find out.

Tuesday was the only day my household held any sort of ritual; Mom would make my brother and me spinach pie, and Dad would set off around rush hour on the ninety minute trek from Jersey to a church gymnasium in deep Brooklyn, where Joe, his best friend of sixty years, had organized for their greater crew of Bay Ridge-born Boomers to shoot some hoops. “Tuesday Night Hoop,” he called it.

For more than thirty years, Joe continued to gather his childhood best friends for that holy ritual, making them custom mustard yellow pinnies with ‘Tuesday Night Hoop’ inscribed on the front and their not-to-be-repeated nicknames on the back. Through births and bereavement, hurricanes and highway construction and 9/11, they met every Tuesday. They met when the Battery Tunnel starting charging ten bucks each way. They met when cancer and knee pains and back aches turned most of the players’ spritely cross-court sprints into sluggish shuffles. They met when the church landlord tried to evict them in pursuit of more lucrative renting opportunities, until Joe, with his gentle grace and kind, coke-bottle glasses eyes, persuaded otherwise. They met because if you didn’t show up to meet, Joe would whip out his meticulous Excel sheet and record your excuse, which had better be damn good, like “Walking Pneumonia” or “FIPM” (Fell Into Parking Meter).

Later I realized that Joe didn’t just do this on Tuesdays; he lived his whole life through the prism of his friends. Christmas was a chance to gather them for a spirited Kris Kringle exchange. The Tribeca Film Festival was a chance to invite sophisticated film analyses over less sophisticated Bud Lights. The pandemic was a chance to hold virtual poker nights, so raucous you could hear the Zoom roars two floors up. His post-retirement free-time was a chance to start an old-man band and book gigs at old-man bars, where more friends could gather.

——-

It turns out that living through the prism of friendship isn’t just more fun; it’s actually healthier. In 1938, when Harvard researchers designed an 80-year-study to explore what makes a long life, they found that the people who were healthiest at age 80 were the ones most satisfied in their relationships at age 50. People with strong social connections, according to the study, experienced less cognitive decline than those without them. Other research confirms this: the absence of strong social connections is linked with poor sleep, heart trouble, chronic stress, and even premature death.

The ancient Greeks knew this, too. When the philosopher Epicurus (341- 270 B.C) came down with a painful and fatal urinary infection, he turned to his most reliable medicine: his friends. Deep in Athens city center, in the friends’ garden-facing, jointly-owned home — a trend gaining steam some 2,400 years later, he spent his final days eating cheese and laughing liberally and asking life’s deep questions beside them, writing that physical pain is no match for the ‘cheerfulness of mind’ that comes from such activities.

——-

When Joe died last April, just nine months after his cancer diagnosis, Bay Ridge boomers everywhere wept, knowing that they’d forever feel the space in their jars. And when one thought it might be in the spirit of Joe to weep not in solitude, but together, they realized something: they didn’t have each other’s phone numbers. The calling, the congregating—that had been the job of Joe, whose own yellow pinnie nickname — the “Commissioner”— said it all.

At his funeral, when throngs of gray and no-haired men howled with laughter as they reminisced over the thousands of gatherings he’d arranged over the years, I wondered if Joe knew what being the Commissioner meant to them. To me.

I wondered if I could live it a bit more like Joe—through the prism of the people I cared most about. I wondered what my days would look like if I could dedicate the hours of them, proportionately, to the rocks in my jar. What would I be giving up? Would that sacrifice be worth it?

And then, when I walked up to his open casket and saw Joe’s gentle grin, I had my answer, for draped over his chemo-worn body was no tuxedo, no achievement medal, but the purest relic of a rare, rock-centric life: a mustard yellow pinnie, and a declaration of his legacy: “Tuesday Night Hoop.”

——-

This Thanksgiving, I’m grateful to have known a jar like Joe’s. And when I find myself habitually reciting the “I’m-too-busys” or “It’s-too-fars” or “I’ll-be-too-tired” in the wake of a chance to gather with loved ones, I’ll try to remember what fills my own jar.

The One Thing on My To-Do List

[From The Connection Cure archive — originally published in 2022]

Recently I realized how I’ve turned everything into a to-do list.

Like Big Post-It had hoped, I’m prolific in the pen-and-paper ones: color-coded sticky notes strewn around my desk, with scribbles to renew my passport and purge my Google Drive and look up how NFTs actually work.

But most concerning are the “lists” I’ve projected everywhere else.

My texts— intentionally-unopened reminders to find time for drinks with Kat or lunch with Ryan.

My inbox—never-yet-read newsletters, hasty “dont-forget-to-X” messages from:me, to:me.

My web browser— dozens of dormant tabs for tofu recipes and tub cleaning hacks.

My iPhone notes— daily, time-stamped tasks that ritually, inevitably, get copy-and-pasted from one day to the next.

----

Pretty much everyone, it seems, has a similarly endless to-do-list. It’s the creeping undertone of every “I’m running late” or “I have to leave early” text. It’s the mental Tetris game we play every Saturday—when we try to squeeze in three birthdays, two catch-up calls, a CrossFit class and a grocery haul during That One Magic Hour there’s no line at Trader Joe’s.

And still, pretty much everyone wishes they had a little bit more time for their to-do-ing. For me, I dream about having 2 free days, or even 2 hours, to tackle my to-do-lists, like weedwacker taking to an overgrown field. What will I do when I finish?, I wonder, conjuring images of reading by candlelight or idle walks along the water.

But then, when I look back on the rare instances when this has happened—when I’ve crossed off a sizable chunk of to-dos, I come to an uninspiring answer: I’d fill it with more stuff, of course.

Just as weeds grow back faster and fuller when you cut them, so do to-do-lists.

----

Back in 1866, an economist named William Stanley Jevons drew attention to this paradox, after an engineer named James Watt invented a more fuel-efficient steam engine.

Because Watt’s engine used less coal than others, economists thought his invention (hack!) would help coal consumption go down.

But actually, that was the problem; because Watt’s steam engine was more efficient —it took trains and boats less coal to travel the same distance than it did with other engines— coal use became cheaper. And so, his engine created a market for more trains. More boats. More routes going to more places. So many, Jevons calculated, that Watt’s invention increased the world’s total coal consumption.

About a hundred years after Jevons, a psychologist named Cyril Northcote Parkinson made a similar observation. He’d been studying the expansion of the British government in the mid-twentieth century. Each year, he noticed, the government created new positions, and, then, more new positions (“subordinates”) for the old new positions to manage. But that wasn’t because Britain suddenly had more work to do (in fact, with their empire dwindling, they had less); instead, it had to do with our human impulse to create work for ourselves. So long as there is time—he said, in what’s now known as Parkinson’s Law—we will always find work to fill that time.

----

During my particularly batty spells of to-do-ing— like hard boiling eggs by-the-dozen or painting my nails while I wait for the G train— I laugh, wondering what the cavemen would say if they could see this little Sissyphyian chase for more hours in the day; if they could witness the whole market we’ve created for time-saving and errand-slashing: One-hour-delivery and meal-prep boxes. Pomodoro timers and pen-and-paper planners. Frozen dinners and Task Rabbits.

Of course, you’d rightly point out, the cavemen can’t relate, because, besides eating Paleo and chilling in the cave, there wasn’t a whole lot for them to do. It’s a blessing, you’ll counter, to live in a world with abundant opportunity, with no time to be bored or sit still.

And you’d be right. We to-do because we there’s so much to do; because we’re curious and ambitious and want to be the most well-lived versions of ourselves.

But yet, I think, we also fixate on the ‘doing’ because it’s a lot easier than ‘not doing’. Because making and then tackling to-do-lists is our way of exercising control over a world that seems to lack it. To-do listing, maybe, is how we cope with societal violence, racism, climate change, government corruption-- forces the cavemen probably didn’t have to deal with; we may not be able to stop the decline of democracy, but at least we mailed those thank you notes.

----

We now have a whole glossary of terms to describe the uneasiness of an unfinished to-do list: FOMO. Sunday scaries. “Fall anxiety,” as an article recently described of the mid-August blues we feel when we think of the trips not-taken, summer reads not-read, plans not-executed.

But we also have many millennia’s worth of literature and philosophy and science suggesting that this feeling—of wishing we’d done more— is kind of a scam in the grand scheme. How, instead, our truest joy comes not from a packed-calendar, but from the simple, focused moments within it.

When the frenetic temptations to to-do-list strikes, it helps to picture 90-year-old-me realizing this; how I’ll be OK with never understanding NFTs and not cleaning my potentially Tetanus-lined bathtub if it means more time on less; the pizza crawls and park picnics and ‘til-2am phone calls. The spontaneous stuff that could have never come out of a to-do list. The contents of what a “well-lived” life really is.

A friend recently told me over coffee, “Busy a decision,” and the opposite is also true: not being busy is a decision. Which is why, scribbled on Post-its and self-sent texts and emails, you’ll find just one item left on my to-do list: stop making them.