Tim Unwin's Blog

November 3, 2025

Our podcast on Digital Inclusion in an Unequal World

The ICT4D Collective has recently launched a podcast channel on Apple Podcasts which contains audio versions of the vignettes in my upcoming book Digital Inclusion in an Unequal World: An Emancipatory Manifesto. The first three episodes are now available as follows:

Tendani Mulanga Chimboza on the exploitation of young women: digital tech at the heart of the immoral economy

This is the first episode of our podcast based on the vignettes contributed by friends and colleagues to Tim Unwin’s new book Digital Technologies in an Unequal World: An Empancipatory Manfesto. In it, Tendani highlights how digital tech is being used to exploit young women in southern Africa. The vignette can also be read here.

Marine Al Dahdah on The Digital Privatisation of India’s Administration

This is the second episode of our podcast based on the vignettes contributed by friends and colleagues to Tim Unwin’s new book Digital Technologies in an Unequal World: An Empancipatory Manfesto. In it, Marine focuses critically on aspects of the digital privatisation of India’s administrative systems. The vignette can also be read here.

Ken Banks on Memories of Innovation for the Most Marginalised

This is the third episode of our podcast based on the vignettes contributed by friends and colleagues to Tim Unwin’s new book Digital Technologies in an Unequal World: An Empancipatory Manfesto. In it, Ken focuses perceptively on the reasons why so many digital initiative notionally intended to help the poor often fail to do so. As he says “I worked for 15 years trying to give a voice to, and support, the work of grassroots organisations through digital tech, butmy frustration in a wider development system that didn’t seem to want to do what they knew was best for those they were meant to serve eventually forced me to step away”. The full vignette can be read here.

Do follow the podcast here to be the first to hear each new episodeOctober 20, 2025

Digital Inclusion in an Unequal World: An Emancipatory Manifesto

I’m delighted to announce the launch of the web-pages for my new book, entitled Digital Inclusion in an Unequal World: An Emancipatory Manifesto, being published by Routledge in 2026. These contain:

An overview of the bookWhat others are saying about itChapter summariesDraft of opening chapterFull drafts of all the 31 vignettes contributed by other leading researchers and practitionersFlyer about the book Order your copy direct from Routledge here Podcasts and audioMany of the authors have contributed audio recordings of their vignettes. These are available here, but are also being shared on a regular basis through the ICT4D blog and podcast over the next six months. Do follow the ICT4D Collective on Apple Podcasts to listen to these inspiring examples of how digital tech can be used constructively by some of the world’s poorest and most marginalised people, but also the reasons why most such initiatives fail sufficiently to serve their interests.

Pre-orderThe book can be pre-ordered from Routledge using the link above, and for those who respond quickly there is a 20% reduction if you order before 23rd October 2025.

January 11, 2025

Why the Global Digital Compact should not be endorsed

Are you or your organisation thinking of endorsing the Global Digital Compact (GDC)? Has your organisation already endorsed it? If so, please think again, and make a valuable political statement by not endorsing it. Endorsing it gives validity to a flawed process and a deeply problematic document. If it only receives a few endorsements those behind it cannot claim legitimacy, despite it having been agreed by governments participating in the UN Secretary General’s Summit of the Future. Those behind the GDC state that it is a “roadmap for global digital cooperation to harness the immense potential of digital technology and close digital divides”. Put simply, as it is currently structured it cannot deliver on this (for some of the reasons why see Reflections on the Global Digital Compact, Why “we” (the people of the world) need to reject the Global Digital Compact, and Scientism, multistakeholderism and the Global Digital Compact). The endorsement process “calls on all stakeholders to engage in realizing an open, safe and secure digital future for all”. As it is currently worded, it will never deliver this.

Choosing not to endorse the GDC is a positive action that will save a huge amount of unnecessary time and effort – and thus money – that could better be spent on delivering effective digital futures in the interests of the many rather than the few. Here are six things to think about before you make a decision:

Have you read it all? You cannot endorse the document unless you agree with it. I also wonder how many people in the 106 organisations that have already signed it have actually read the full document, and do indeed agree with its content? If you do not agree with all of it, how can you endorse it?Does the UN Secretariat have the capacity (both quantitatively and qualitatively) to manage the envisaged GDC process. Despite the planned dramatic expansion of the Office of the Tech Envoy, do you think there is capacity within the UN Secretariat to manage all of the endorsements and engage you actively in future processes and activities? Anyone who is aware of the time and effort that have already been spent by UN agencies in delivering previous global digital initiatives (and processes such as WSIS and the IGF) will know how complex and difficult this is. Do you have faith that the UN Secretariat can effectively deliver the required management of the GDC process? What indeed will this involve?Whose interests does the GDC really serve? Is it anything more than a vanity project for a few leaders within the UN Secretariat, and the powerful interests that they serve? Will it really deliver benefits in the interests of the world’s poorest and most marginalised? If you do not think so, you should not endorse it.Is your organisation merely signing it for appearance’s sake? Are you afraid that you might miss out on an opportunity? Is it just a chance to rebrand what you are already doing, and be seen to be supporting a “global” initiative that has the UN label behind it?Are you endorsing it primarily in your own interests? Are you doing this in the hope that there could be possible future advantages for your own organisation in doing so? Are you really committed to doing things differently so that digital technology can indeed be used by everyone in their own interests? That means everyone, not just the rich and powerful. Are you really going to change fundamentally what you are doing so that you work in the interests of those without power, without a voice, who are being enslaved by those driving the future of digital tech?How can you endorse the GDC if you do not yet know exactly what this means in terms of your future commitments? Apparently endorsing the GDC merely means that you endorse its vision and principles. Do you really endorse all of them? If not, can you endorse it? The endorsement protocol also states that “Organisations and associations can specify action areas where they are involved in and/or interested in contributing, regardless of whether they have endorsed the Compact”. Yet, this does not say what is meant by “contributing”. What do you really want to contribute, and how will you do so?Please think twice before endorsing the GDC. Do you really think that it provides a sufficiently rigorous or comprehensive framework for crafting a future for the design and use of digital tech that will serve the interests of the world’s poorest and most marginalised people and communities. If you care deeply about these issues, can you really endorse it?

November 13, 2024

On the richness of Africa

Crafting the next chapter of my new book about digital tech and development, I found myself writing about poverty again, and remembered a paper On the richness of Africa that I wrote back in 2008. It was never accepted by the journals I submtted it to for publication, but on re-reading it I think that much of what I wrote then is even more pertinent today (the editors clearly thought otherwise, and that I was too far way from the accepted orthodoxy then, and probably still am!). Interestingly, though, I found that “pirate copies” seem to be available on AI generated sites, so someone must have found it interesting!

Given this, I just thought that I would make it available officially once more here. The abstract reads as follows:

ABSTRACT: This paper argues that there needs to be a shift in the balance of understandings of Africa from being a continent dominated by poverty to one that is instead conceptualised as being ‘rich’. It begins with an overview of arguments that seek to portray Africa as being poor, and then examines theinterests that donors, African governments, the private sector, civil society and consultants all have in propagating such an image. In contrast, it then illustrates how Africa can instead be seen as being rich in terms of its mineral wealth, agricultural potential, culture, social and political institutions, andphysical environment. It concludes by arguing that development initiatives that continue to seek to eliminate poverty in Africa will remain doomed to failure unless they refocus their attention on building upon the continent’s existing riches.

Hoping that others (than the digital pirates) might find it still of interest!

November 12, 2024

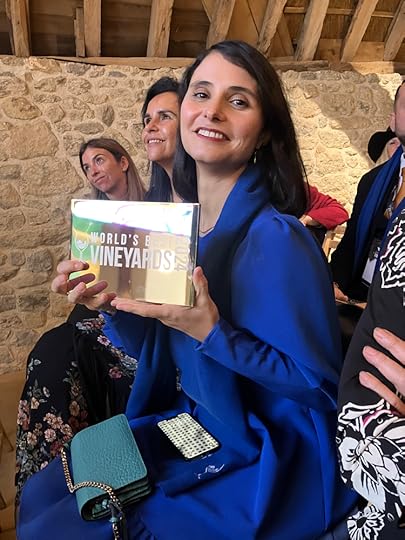

The World’s Best Vineyards Awards 2024 – and an exploration of wineries and vineyards in south-east England

Much of my research and teaching earlier in my career was related to wine, but from the late 1990s the realisation that, while wine can do much to make us happy, being directly involved in the enormous changes taking place as a result of the design, production and use of digital technologies was something that could actually make the world a better place. I greatly value the opportunities that I have had over the last 25 years to engage directly in that field, but as I increasingly realise that digital tech is now beng used to do more harm than good, I value even more the opportunities that I have had to re-engage more actively with wine. I am therefore especially grateful to have been asked at the start of this decade to serve as the UK and Ireland Academy Chair for the World’s Best Vineyards Awards, initiated by William Reed Ltd. Each year, more than 500 panellists from across the world vote for their favourite wine tourism experiences, and these are then collated into lists of the top 50, and the next 51-100 award winners. Although selecting the UK and Ireland panel, and ensuring that all panellists do indeed vote is very much more diffficult and exhausting than you would imagine, the team at William Reed has brought together an amazing group of people associated with the awards, and alongside the award winners we have become a wonderful group of friends, committed to enhancing the visibility and success of wine tourism, which makes all the effort worthwhile. This owes much to Andrew Reed’s (MD Wine and Exhibitions) personal charm, hard work and commitment to perfection, as well as the enthusiasm of the team he has brought together to make the awards the success that they have become.

Each year, the awards ceremony is held in a different part of the world: the Rheingau and Rheinhessen in 2021, Mendoza in 2022, and Rioja in 2023. In 2024 it was the turn of England to host the awards ceremony, and this provided an excellent opportunity for participants to experience the transformations that have taken place in English wine production over the last two decades. The awards ceremony itself was generously hosted by Nyetimber, in its magnificent Medieval Barn, with Eric Heerema (Owner and Chief Executive), Cherie Spriggs (Head Winemaker) and Zoë Dearsley (Brand Ambassador) providing an overview of the property and the wines before the awards were announced. Hopefully the images below capture something of the pleasure and excitement of the event.

The introductions

The Awards ceremony

The Awards ceremony

As Chair of the UK-Ireland panel, it was great to see two of our vineyards and wineries in the top 100 awards: Gusbourne and Nyetimber. Both are to be congratulated for their achievements in this very tough competition.

Pre-awards visit to Tinwood Wine Estate

Pre-awards visit to Tinwood Wine EstateBefore the awards ceremony, all Academy Chairs had been invited to an estate visit and delicious lunch and wine tasting at Tinwood Estate, hosted by Art and Jody:

An exploration of the best of south-east England’s wineries and vineyards

An exploration of the best of south-east England’s wineries and vineyardsAfter the awards ceremony, it was an enormous pleasure to take four of the Academy Chairs (Chiara Giorleo – Chair for Italy; Lotte Karolina Gabrovits – Chair for Germany, Benelux and Nordic; Pál Gabrovits – Chair for Austria, Hungary and Switzerland; and Pedro Nelson Dias – Chair for Portugal) on an exploration of some of the best wineries and vineyards in Surrey, Sussex and Kent. We are all immensely grateful to the proprietors and staff of these estates for their hospitality and the time they spent with us. Glimpses of our experiences (in the order that we visited them) are shared below to encourage you to visit these estates and get to know some of the excellent wines that are currently being produced in south-east England.

Greyfriars Vineyard

Albury Vineyard and Silent Pool

Albury Vineyard and Silent Pool

Leonardslee Family Vineyard

Leonardslee Family Vineyard

Ridgeview

Ridgeview

Chapel Down

Chapel Down

Gusbourne

Gusbourne

Bolney Wine Estate

Bolney Wine Estate

A big thank you once again to all those who hosted us and shared their wines so generously.

July 31, 2024

The flawed logic of the new government’s renewable energy programme: re-valuing the rural environment

“…families and businesses continue to pay the price for Britain’s energy insecurity. Bills remain hundreds of pounds higher than before the energy crisis began and are expected to rise again soon. At the same time, we are confronted by the climate crisis all around us, not a future threat but a present reality, and there is an unmet demand for good jobs and economic opportunities all across Britain”

Ed Miliband, Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero, Great British Energy founding statement, 25 July 2024) https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/introducing-great-british-energy/great-british-energy-founding-statement.

“Backed by a capitalisation of £8.3 billion of new money over this Parliament, Great British Energy will work closely with industry, local authorities, communities and other public sector organisations to help accelerate Britain’s pathway to energy independence”…” Great British Energy will create thousands of good jobs, with good wages, across the country. We will seize the opportunities of the clean energy transition and ensure the British people capture those benefits”

The new UK government’s recent announcement about renewable energy will please many people, especially the business community who will benefit from government subsidies and easing of regulation, urban dwellers who will be able to continue their energy-extravagant lifestyles at the expense of Britain’s rural heritage, and the jingoists who believe that Britain really is “Great”. However, it is based on a deeply flawed understanding of the causes of climate change and the need to reduce carbon emissions,[i] as well as a flawed approach to valuing the rural environment.

In addressing these issues, I must first acknowledge my own rural “peasant” biases. My early research in the 1970s and 1980s was about the evolution of the medieval rural landscape in England, and at the same I was also undertaking research on the contemporary lives of people living in rural areas in some of the poorest parts of Asia and Europe. I was honoured to serve as the elected Secretary General of the Permanent European Conference for the Study of the Rural Landscape for a decade between 1990 and 2000. These interests have never left me, and over the last 50 years I have come to have a deep love for, interest in, and understanding of the importance of rural landscapes as one of the richest parts of Britain’s heritage. I also know a world where the only heating in my house was from a back boiler, which also had to be on if I wanted any hot water. In winter, I vividly recall the water in the glass by my bed freezing at night. We wore layers of warm clothing in winter, and enjoyed the heat of summer, long before central heating and air conditioning[ii] became widespread.[iii]

This critique focuses primarily on three of the main issues that arise from the government’s recent announcements: lower cost electricity generation; renewable impact (both production and distribution); and the business model that serves the interests of the few rich rather than the many poor.

Energy supply and demand: why lower cost energy will increase the environmental impact

Energy supply and demand: why lower cost energy will increase the environmental impactThe idea that lowering energy costs through the use of renewable energy will be good for the people and good for the environment is deeply problematic. It appears to be grounded in the mis-placed belief that carbon emissions and their impact on climate change are perhaps the biggest challenge facing humanity, and that in our country we can address this through a heavily subsidised energy system that will enable us to be energy independent at a lower cost than we are paying at the moment. As Ed Miliband wrote on 25 July 2024, “That is why making Britain a clean energy superpower by 2030 is one of the Prime Minister’s 5 missions with the biggest investment in home-grown clean energy in British history.”[iv]

The problem is that lowering energy costs is almost certain to increase energy consumption in the long term, and it is energy consumption that is the real problem, not the blend of energy that we choose to supply. It is often argued that energy is an inelastic good, and that demand and supply are not responsive to price.[v] In part, this is because there are no close substitutes for “energy” as a whole, although differential costs for alternative fuel types mean that choices of specific fuels (including renewables) will indeed change depending on price.

There are, though, at least two problems with such an argument. First, one of the largest drivers of energy demand, and thus carbon emissions globally, is actually demographic growth (see my An environmentally harmful alliance of growth mantras).[vi] Historically, population growth in the UK has also been one of the main factors increasing energy demand, although the restructuring of our economy since the 1970s “from energy intensive industries, such as cement and steel, to services-based industries such as finance and consulting” has actually led to a substantial decrease in overall energy consumption.[vii] This decline in industrial consumption has masked domestic patterns of consumption. Moreover, recent evidence suggests that the impact of increased pricing mainly as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine has also actually had an impact on reducing existing demand (along with warmer weather) to levels not seen since the 1950s.[viii] This brings into question just how inelastic energy pricing really is. It seems highly likely that reducing prices as a result of the proposed government investment in renewables will actually lead to a resurgence in domestic consumption, which is something that will have negative impacts on the environment. Second, though, demand is also heavily influenced by what societies deem to be appropriate lifestyle choices. Being profligate with energy has been a core characteristic of British lifestyles for at least half a century when energy has been relatively cheap. We don’t actually need to heat and cool our homes and offices as much as we do. If price pressures encouraged us to reduce our domestic energy consumption, then this could only be a good thing nationally for the environment – although energy providing companies would undoubtedly bemoan the reduction because they flourish on increasing markets.

It would be much more sustainable to focus more on implementing effective strategies to reduce overall energy demand instead of increasing lower cost provision of renewable energy, especially when its environmental harms are fully appreciated. To be sure, there will remain those for whom energy costs will still be too high (so-called “fuel poverty”), but it is relatively easy to resolve this through appropriate financial subsidies or tax benefits for the financially poorest in our society, rather than funding businesses to produce more cheap renewable energy.

The environmental impact of the production and distribution of renewable energy.

The environmental impact of the production and distribution of renewable energy.One core element of the new government’s plan is to change the planning procedures to make it easier for renewable energy projects, notably wind farms and solar panels to be constructed on the land of the British Isles.[ix] As Mullane (2024) has commented, “Under the old policy any local community opposition could block the development of onshore wind farms, but this is no longer the case. The revised policy places onshore wind on the same footing as other energy developments under the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). This means onshore wind applications will now be processed in the same way as other renewable energy projects.”[x] Moreover, if large windfarms are indeed designated as nationally significant infrastructure projects this would mean that the Secretary of State, Ed Miliband, would sign off on them, and local councils and citizens would not have a say in the decision.[xi] For such decisions to be made, though, the Secretary of State would need to prove that the benefits of an onshore windfarm or similar energy project were greater than the costs, and among these costs has to be the environmental impact that they have. Our present systems of judging such impact, though, are woebegone, and fail to take satisfactory recognition of the real cost of destroying the historic landscapes that lie at the heart of our culture.[xii] The required environmental impact analyses are indeed quite detailed, but they fail sufficiently to address fundamental questions about the nature of the landscape, especially when windfarm turbines can be seen from a very long distance away. Traditionally, many such processes have been based on some kind of “willingness to pay” approach, where costs are estimated based on how much people would be willing to pay extra not to have something, such as a windfarm, in their neighbourhood. Unfortunately, people living in such areas are often poor, and the amounts they are willing to pay are readily overwhelmed by the financial and political alliances of companies and governments.[xiii] The basic problem, though, is that we don’t have a robust system for judging the impact of these initiatives, and it would seem to be essential that we do put an acceptable process in place before mega-onshore-windfarms are created that will change the landscape forever. Will, for example, detailed archaeological surveys be required before these schemes are put in place?

It is not only the environmental impact of windfarms and solar panels that requires attention but also the infrastructure necessary to transmit the electricity to where it is used. There is a robust ongoing debate about the impact of pylons, with campaigners arguing that they should not be built, and cables instead put underground at a cost that would in most instances not make such projects feasible.[xiv] Ultimately, the decisions that will be made will be political ones, and it seems likely at present that the new government will override such objections, claiming that they are nothing more than nimbyism.[xv] The use of new designs of pylons in the shape of a T might go some way to reduce the eyesore of these infrastructure projects,[xvi] but other more radical solutions also need to be found. One option, for example, would be to build entire new communities around such installations, so that there would be no need for pylons to transport electricity to current centres of high demand. Thinking more radically, it would make sense for heavy industrial uses of electricity to be relocated to parts of the world where few people live and there are excellent sun or wind resources that could be tapped to power them.[xvii] British companies could invest in industrial production in the Sahara for example, although this would not necessarily resolve the geo-political desire for self-sufficiency in energy.

A related challenge is that the areas of highest absolute demand for energy in the UK are often not where there is greatest potential for renewable production, especially for wind, hydro, and tidal. Over the last 35 years, transport (c.38% in 2022) has consumed the largest share of energy, followed by domestic (c.27% in 2022), industry (c.18% in 2022) and services (c. 17% in 2022).[xviii] These activities tend to be concentrated in and around urban areas, and accessing energy from places where it tends to be produced often therefore becomes yet another example of the “urban” exploiting and extracting a surplus from the “rural”.[xix] To be sure, wealthier people with larger houses tend to consume more energy per household, and often live in rural or suburban areas, but such impressions are misleading when interpreting total energy consumption across all sectors. Maps of energy consumption per unit of area in different parts of the UK are difficult to find, since most data are disaggregated on a per household basis. This in itself further disadvantages low population density, rural areas, because it gives the impression that they also have high total consumption levels, which is usually not the case.[xx] The voices of the relative few rural people who live in areas which are likely to be dominated by renewable energy production for the urban masses and the rich, need to be heard as representatives of the heritage landscapes that cannot speak for themselves.

The business interests behind renewable energy

The business interests behind renewable energyAn important part of the government’s case for expanding renewable energy production is that it will contribute to UK economic growth, employment, and expertise that will enable British companies to have a competitive advantage abroad – so that Britain can be truly great again. That is why Miliband makes the jingoistic claims that ““making Britain a clean energy superpower by 2030 is one of the Prime Minister’s 5 missions with the biggest investment in home-grown clean energy in British history”.[xxi] That is why the Labour Party talks and writes about how they will “Make Britain a clean energy superpower”.[xxii]

This development will only happen if the government spends billions of pounds of taxpayer’s hard-earned money on subsidising companies to develop these technologies and build the infrastructure to provide electricity where it is wanted. The price of renewable energy without government subsidy would be unaffordable by most people, and few companies would invest in the renewable sector without such subsidies and guarantees. The government has announced that it will spend £8.3 billion new money over the life of this parliament in capitalising Great British Energy, a publicly owned company, to “work closely with industry, local authorities, communities and other public sector organisations to help accelerate Britain’s pathway to energy independence”.[xxiii] Interestingly, it does not mention citizens or comrades in this list of those it will work with, let alone “for”. Companies have sold the government a dream that renewable energy will save the world from climate change and make Britain great again. This is primarily in their interests, not ultimately in the interests of the majority of British citizens. Moreover, the very real environmental harms caused by such massive roll-out of these technologies are either ignored or vastly under-estimated.

The growing power of the renewable energy sector is well-illustrated by their reaction to the new government’s apparently ambitious new subsidies. As The Guardian has recently reports: “Labour’s clean energy targets may already be in jeopardy just weeks after the party came to power with the promise to quadruple Britain’s offshore wind power, according to senior industry executives…The offshore wind industry has said there will not be enough time to develop the projects needed to create a net zero electricity system by the end of the decade unless ministers increase the ambition and funding of the government’s upcoming “make or break” subsidy auctions”.[xxiv] Ironically, many environmentalists, coming from a very different position to that of most companies, have also criticised the government for not going far enough. As the co-leader of the Green Party, Adrian Ramsey, has said “We need real change if we are to meet the demands of the climate crisis. These Labour plans do not deliver it…Compared to Labour’s original commitment to spend £28bn a year on green investment, this announcement of just £8.3bn over the course of the parliament looks tiny and is nowhere near enough to deliver Labour’s promise of ‘clean electricity’”.[xxv]

There is much to be applauded about the government’s aspirations, but some of the propaganda such as that noted below from the Labour Party seems to be over-ambitious – it is certainly surprising to see the claim that this will make us secure from “foreign dictators”.

In conclusion

Britain needs Great British Energy

A new publicly owned, clean power company for Britain.

Britain already has public ownership of energy – just by foreign governments. Taxpayers abroad profit more from our energy than we do. It is time to take back control of our energy.

A first step of a Labour government will be to set up a new publicly owned champion, Great British Energy, to give us real energy security from foreign dictators.

Great British Energy will be owned by the British people, built by the British people and benefit the British people. It will be headquartered in Scotland, invest in clean energy across our country, and make the UK a world leader in floating offshore wind, nuclear power, and hydrogen.

https://great-british-energy.org.uk/

The British people need to recognise that there will be a very significant impact on our precious rural landscapes from these new government policies. The scale of this is largely unacknowledged and unappreciated. Human impact on nature – our physical environment – has reached crisis point, and this is an issue very much bigger than merely climate change and the reduction of carbon emissions. The new government policies, although possibly being well-intentioned, will not solve the crisis for the British people, but are in danger of making it worse.

This article has merely touched on three of the main issues surrounding the new government’s renewable energy policy, and in conclusion offers three suggestions for practical ways forward:

First, we should focus much more on reducing demand for energy, rather than on supply issues. Population growth and energy-extravagant lifestyles are the real underlying reasons why we have an energy crisis. We need to make fundamental changes to our lifestyles that respect nature rather than consume it through our selfish individualistic greed and ambition.Second, we need to have a fundamental overhaul of our approaches to environmental impact assessment relating to renewable energy intiatives, that is much more holistic and places greater value on respect for nature and our cultural heritage embedded in rural landscapes. We cannot allow a Secretary of State to over-ride citizen opinion by imposing large infrastructure projects in areas of significant environmental value.[xxvi]Third, whilst energy security is an important concern of government, and it is indeed the private sector that is currently the main engine of the economy, governments need to prioritise the interests of all their citizens, and especially the poorest, helpless and most marginalised. The proposed policies seem to serve the interests of global capital more than they do those of the majority of citizens in the UK. It is the interests of the business sector that are now driving renewable energy development, and these insufficiently address the holistic impact of their technologies on nature.[xxvii] We therefore need to provide much more training to those in private and public sector renewable energy companies about the holistic character of environmental impact, including the importance of cultural heritage in relevant decision making processes.This is an important moment for British society, and a change in government always provides an opportunity for the introduction of beneficial new policies and practices. The government’s intention to address energy security and the environmental impact of energy production is to be applauded, but, and it’s a big but, these proposals seem likely to do more harm than good. Many people might feel better off as a result in the short-term, but the long-term environmental impacts of these proposals are likely to result in irretrievable harm to the British natural and cultural environment. It may be that people in government and large swathes of our society, many of whom live modern urban and suburban lifestyles, do not really care. I am sure that I am in a minority, but when our children’s children grow up in a world divorced from lived reality in nature, they will not only have broken the link with their past cultural heritage, but they will have no way of reclaiming it physically. It will become merely a virtual memory, and it will be too late to retrieve that important element of being truly human that is encapsulated in our rural landscapes. The labour of countless rural “peasants” that is encapsulated and represented in these landscapes will be obliterated and made inaccessible for ever from our lived experience because of our modern, technology-driven ignorance and greed.

[i] See the work of the Digital-Environment System Coalition DESC at https://ict4d.org.uk/desc and Unwin, T. (2022) “Climate Change” and Digital Technologies: redressing the balance of power (Part 1), https://timunwin.blog/2022/11/10/climate-change-and-digital-technologies-redressing-the-balance-of-power-part-1/

[ii] Air conditioning in 2023 was estimated to represent about 20% of total electricity use worldwide, and 10% of use in the UK, but total usage is likely to increase in the future (Khosravi, F., Lowes, R, Ugalde-Loo, C.E. (2023) Cooling is hotting up in the UK, Energy Policy, 174, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113456.)

[iii] See also Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2022) UK Energy in Brief, UK: National Statistics, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/63ca75288fa8f51c836cf486/UK_Energy_in_Brief_2022.pdf; and Energy Dashboard, https://www.energydashboard.co.uk.

[iv] Miliiband, E. (2024) Great British Energy founding statement: Secretary of State forward, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/introducing-great-british-energy/great-british-energy-founding-statement.

[v] Taylor, H. (2022) How energy prices will play out, Investors’ Chronicle, https://www.investorschronicle.co.uk/content/cae53ff0-a422-5858-b619-9ccb21a00be6.

[vi] See also my COP 27, loss and damage, and the reality of Carbon emissions, and “Climate Change” and Digital Technologies: redressing the balance of power (Part 1)

[vii] World Economic Forum (2019) UK’s energy consumption is lower than it was in 1970, https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/08/uk-energy-same-as-50-years-ago/.

[viii] Mavrokefalidis, D. (2024) UK energy bible shows demand plummets to 1950s levels, Energy Live News, https://www.energylivenews.com/2024/07/30/uk-energy-bible-shows-demand-plummets-to-1950s-levels/.

[ix] Gov.uk (2024) Policy statement on onshore wind, 8 July 2024, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/policy-statement-on-onshore-wind/policy-statement-on-onshore-wind.

[x] Mullane, J. (2024) Experts react to Ed Miliband lifting ban on onshore wind farms, Homebuilding & Renovating, 11 July 2024, https://www.homebuilding.co.uk/news/experts-react-to-ed-miliband-lifting-ban-on-onshore-wind-farms

[xi] Pratley, N. (2024) Labour lifts Tories’ ‘absurd’ ban on onshore windfarms, The Guardian, 8 July 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/jul/08/labour-lifts-ban-onshore-windfarms-planning-policy. See also, Vaughan, A. and Smyth, C. (2024) Ed Miliband scraps de facto ban on onshore wind farms, The Times, 9 July 2024, https://www.thetimes.com/uk/politics/article/ed-miliband-onshore-wind-farms-ban-gtqjvqhrm.

[xii] For a selection of relevant UK procedures, see https://www.gov.uk/guidance/environmental-impact-assessment, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7c406eed915d7d70d1d981/geho0411btrf-e-e.pdf, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5b4cd2c9e5274a732b817d49/SECR_and_CRC_Final_IA__1_.pdf, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2017/572/contents, https://www.gov.uk/guidance/offshore-energy-strategic-environmental-assessment-sea-an-overview-of-the-sea-process, https://rpc.blog.gov.uk/2021/11/10/considering-environmental-issues-in-impact-assessments/,

[xiii] An interesting new approach recently adopted by the Dutch government for offshore auctions focuses instead heavily on non-price indicators, including attention to the ecosystem and possible negative effects on birds and marine habitats https://windeurope.org/newsroom/news/new-dutch-offshore-auctions-focus-heavily-on-non-price-criteria/. My thanks to Will Cleverly for bringing this example to my attention.

[xiv] See for example, Pratley, N. (2023) The next UK net zero battleground is electricity pylons, The Guardian, 26 September 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/business/nils-pratley-on-finance/2023/sep/26/the-next-uk-net-zero-battleground-is-electricity-pylons; Davies, S. (2024) Sparking a crucial debate: the problem with pylons, NESTA, https://www.nesta.org.uk/feature/future-signals-2024/the-problem-with-pylons/; Energy Networks Association (2024) Explainer – building new pylons in the UK, ENA, 5 July 2024, https://www.energynetworks.org/newsroom/explainer-building-new-pylons-in-the-uk.

[xv] See for example, Partington, R. (2024) Labour told it will need to defeat ‘net-zero nimbys’ to decarbonise Britain, The Guardian, 22 July 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/jul/22/labour-decarbonise-britain-resolution-foundation-report-net-zero-nimbys.

[xvi] National Grid (2023) National Grid energise world’s first T-pylons, https://www.nationalgrid.com/national-grid-energise-worlds-first-t-pylons.

[xvii] See Xlinks, One world, one sun, one grid, https://xlinks.co – thanks again to Will Cleverly for this example.

[xviii] Department for Energy Security & Net Zero (2023) Energy consumption in the UK (ECUK) 1970 to 2022, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/651422e03d371800146d0c9e/Energy_Consumption_in_the_UK_2023.pdf.

[xix] CREDS (2024) Spatial variation in household energy consumption, showing the average total energy use (per person rather than per household) for each Lower Super Output Area (LSOA) in England and Wales, CREDS, https://www.creds.ac.uk/publications/curbing-excess-high-energy-consumption-and-the-fair-energy-transition/, 30 July 2024. See also my 2013 piece on Valuing the impact of wind turbines on rural landscapes: Conca de Barberà, as well as other writings, including Unwin, T. (2023) Experiencing digital environment interactions in the “place” of Geneva (Session 403): the DESC Walk

[xx] See for example the maps in Department for Energy Security & Net Zero (2024) Subnational electricity and gas consumption statistics, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/65b12dfff2718c000dfb1c9b/subnational-electricity-and-gas-consumption-summary-report-2022.pdf.

[xxi] Miliiband, E. (2024) Great British Energy founding statement: Secretary of State forward, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/introducing-great-british-energy/great-british-energy-founding-statement.

[xxii] Labour (2024) Make Britain a clean energy superpower, https://labour.org.uk/change/make-britain-a-clean-energy-superpower/.

[xxiii] Miliiband, E. (2024) Great British Energy founding statement: Secretary of State forward, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/introducing-great-british-energy/great-british-energy-founding-statement.

[xxiv] Ambrose, J. (2024) Labour must speed up wind power expansion or miss targets, says renewables industry, The Guardian, 29 July 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/jul/29/labour-must-speed-up-wind-power-expansion-or-miss-targets-says-renewables-industry.

[xxv] Green Party (2024) Great British Energy – not the real change we need, https://greenparty.org.uk/2024/05/30/great-british-energy-not-the-real-change-we-need/

[xxvi] It can be noted that “unspoilt” rural landscape in the UK is becoming scarcer and scarcer – and thus more precious. While this is in large part because of increasing population and affluence, it is also morally wrong that urban elites (as well as the urban and the elites generally) should impose their personal prejudices and biases that will harm rural landscapes that they do not understand or value. Moreover, significant destruction of the physical environment is also likely negatively to impact tourism revenue as cherished landscapes are changed by the construction of windfarms and mega-solar installations. The CLA estimates that “Rural tourism accounts for 70-80% of all domestic UK tourism and adds £14.56bn to England and Wales’ Gross Value Added” (CLA, supporting rural tourism in England, 21 March 2024, https://www.cla.org.uk/news/supporting-rural-tourism-in-england/).

[xxvii] Many people working for companies in the sector do so because of their commitment to environmental well-being, but often those trained as engineers and scientists do not have a sufficient understanding of the physical and cultural environment impacted by their technologies.

July 9, 2024

Scientism, multistakeholderism and the Global Digital Compact

Recent AI global summit in Geneva: the glitz and glamour of digital tech

Recent AI global summit in Geneva: the glitz and glamour of digital techThe Internet and World Wide Web have been used to bring many benefits across the world, but they have also been used to cause very significant harms. To deny this, is to fall into the trap of scientism, science’s belief in itself. Science is not neutral and value free as many scientists would have us believe. Above all, scientific enquiry and innovation are not inherently “good”, however that is defined. Moreover, science is not necessarily the best or only way of making truth claims about our existence on planet earth.

The recent “Open Letter to the United Nations” by a distinguished group of 37 scientists, notably including Vint Cerf (described in the letter as Internet Pioneer) and Sir Tim Berners-Lee (described as Inventor of the World Wide Web), raises very important issues around the nature of digital technologies and the so-called multistakeholder model. In essence, it seeks to persuade those involved in the Global Digital Compact “to ensure that proposals for digital governance remain consistent with the enormously successful multistakeholder Internet governance practice that has brought us the Internet of today”.

While I profoundly disagree with the agenda and process of the Global Digital Compact, I do so from the other end of the spectrum to the arguments put forward in their Open Letter. I have three fundamental objections to their proposal: that they largely ignore their responsibility for the harms; that their interpretation of multistakeholderism as being bottom up is flawed; and that, in effect, they represent the corporate interests that have for long sought to subvert the UN system in their own interests.

Science and innovation are not necessarily goodThe Internet and World Wide Web were originally invented by scientists (“engineers” as they are referred to in the Open Letter), who were caught up in the excitement of what they were doing. As many of their subsequent statements have suggested, I’m sure these engineers believed that they were doing good. Thus, as the letter goes on to state, the success of those involved in the subsequent development of the Internet and the Web “can be measured by where the Internet is today and what it has achieved: global communication has flourished, bringing education, entertainment, information, connectivity and commerce to most of the world’s population”. While they acknowledge later in their letter that there are indeed harms resulting from the use of the the Internet and Web, they say little about the causes of these harms , nor about the structures of power in their design and propagation. By claiming that the basic architecture of the Internet must not be changed, because it is empowering, they fail sufficiently to take into consideration the possibility that it was their original design of that architecture that was flawed and enabled the rise of the very many harms associated with it.

There is nothing inherently “good” about science; it serves particular sets of interests. Scientists are therefore as responsible for the harms, unintended or deliberate, caused by their inventions as they are for any “good” for which they are used. The letter claims that the technical architecture of the Internet and Web cannot on its own address the harms it is used to cause, but offers no evidence in suport of this argument. If the Internet and Web had not been created as they were, if the architecture had been different, might not the harmful outcomes have been avoided? Did the engineers and others involved take the time to consider the full implications of what they were doing? Did they consider the views of philosophers and social scientists who have studied the diffusion of innovations and their potential harms in the past? Or were they caught up in the technical interests of positivist science? I do not know the answer to these questions, but I do know that they are as responsible for the scale of the harms caused through the use of their inventions, as they are for any good.

On multistalkeholderismThe arguments of the Open Letter are based on the notion that multistakeholder processes have been “enormously successful” in bringing us “the Internet of today”, and that the Global Digital Compact should not damage these by replacing it with “a multilateral process between states”. Accordingly, the authors should also recognise that it is these same multistakeholder processes that have also brought us the harms associated with the Internet and Web. Moreover, the claim that this multistakeholder model of Internet governance is “bottom-up, collaborative and inclusive” is also deeply problematic. Just over a decade ago, I wrote a critique of multistakeholderism (see also my Reclaiming ICT4D) in which I highlighted that despite such aspirations and the efforts of those involved to try to achieve them, the reality is very different. Those arguments apply as much today as they did when I first wrote them. In essence, I argued that there are two fundamental problems in the practice of multistakeholderism: unequal representation, and the decision making process. I challenge the claim that in practice these processes are indeed bottom-up, collaborative and inclusive. The following are just some examples in support of my case:

The world’s poorest and most marginalised people and communities do not participate directly in these gatherings.how many people with disabilities or ethnic minorities actually contribute directly?Most of the organisations claiming to represent such minorities sadly usually have their own interests more at heart than they do of those they claim to speak for.There is a very significant power imbalance between those individuals, organisations and states who can afford to participate in these deliberations and those who do not have the financial resources or time to contribute.Small Island states are notable in their absence from many of these processes, simply because of the cost and time involved in such participation.The large, rich global corporations can afford to engage and lobby for their interests, whereas the poorest and most marginalised face almost impossible difficulties in seeking to compete with them.There are enormous linguistic and cultural barriers to full and active engagement.This applies as much to the technical language and processes used in these deliberations as it does to the dominance of a few interrnational languages in the discussions.The processes of consensus decision making are extremely complex, and require considerable experience of participation before people can have the confidence to contribute.Almost by definition, minority voices are unlikely to be heard in such processes of reaching a consensus.I could highlight many more examples of these challenges from my 25 years of experience in attending international “multistakeholder” gatherings, from the Digital Opportunities Task Force (DOT Force), to the regular cycle of subsequent WSIS, IGF, ICANN, and UN agency gatherings. This is not to deny that many such multistakeholder gatherings do indeed try to support an inclusive approach, but it is to claim that the reality is very different to the aspiration. The image below from the GDC’s page on its consultation process suggests where the power really lies.

It is surely no coincidence that the third of these sub-headings focuses on the $5tn+ represented by the market cap of private sector companies. This need not have been so. They could instead have given a clear breakdown of the exact numbers of submissions from different types of organisation.

The corporate interests underlying the UN digital system and the Global Digital CompactIt is somewhat ironic that this Open Letter is written by “scientists” who in reality largely represent or serve the interests of the digital tech companies, in an effort to roll back what they see as the growing interests of governments represented in the GDC drafts. In stark contrast, I see the entire GDC process as already having been over-influenced by private sector companies (see my 2023 critique of the GDC process). In theory, states should serve the interests of all their citizens, and should rightly be the sector that determines global policy on such issues. It is right that regulation should serve the interests of the many rather than the few.

Here I just briefly focus on three aspects of these challenges: the notion that the Internet is a public good or global commons that serves the interests of all the world’s people; the private sector representation of the scientific community; and the undermining of UN priorities and agendas by the private sector in their own interests. Before I do so, though, I must emphasise that there are many individual scientists who do seek to serve the interests of the poor rather than the rich, and a few of these do also have considerable knowledge and understanding of ethics and philosophy more generally. I also acknowledge the problem of what to do about disfunctional and self-seeking governments.

The Internet as public goodThe arguments that the Internet and Web are public (or for some “common”) goods that should be kept free so that everyone can benefit, and at its extreme that access to the Internet should be considered a human right, are fundamentally flawed. People do not benefit equally from such goods (these arguments go back to Aristotle, and can in part be seen in Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons). Those who benefit the most are the rich and powerful who have the finance, knowledge and ability to do so. This is why digital tech has become such a driver for increased global inequality at all scales. Those who are creating the contemporary digital system are doing so largely in the interests of global capital (for much more detail see my arguments in my Reclaiming ICT4D, Power hierarchies and digital oppression: towards a revolutionary practice of human freedom, and Freedom, enslavement and the digital barons: a thought experiment).

An unhealthy relationship between science and private sector companiesNot all science and innovation are funded or inspired by the interests of private sector corporations, but it is increasingly becoming so, especially in the digital tech sector. Not all scientists or engineers fail to consider the possible unintended consequences of their research and innovation, but many do. All of us have choices to make, and one of those is over whether we seek to serve the interests of the world’s poorest and most marginalised, or the interests of the rich and powerful. Moreover, it is important to recognise that historically it has usually been the rich and powerful who have used technology to serve and reinforce their own interests. There is a strong relationship between power and science (see my The Place of Geography, and Reclaiming ICT4D, both of which draw heavily on Habermas’s Critical Theory, especially Erkenntnis und Interesse). Scientists cannot hide behind their claim that science is neutral or value free.

These challenges are especially problematic in the digital tech sector. Thus, leadership and membership of entities such as the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG) of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), the Internet Architecture Board (IAB), and the W3C (Board of Directors) are all heavily dominated by representatives from private sector companies and computer scientists with close links to such companies. It is just such people who have signed the Open Letter.

The private sector subverting the UN system in its own interestsIt is entirely apropriate that there should be close dialogues between governments and private sector companies. Likewise, it is important for there to be dialogue between UN agencies and companies. Indeed, international organisations such as the ITU and the Commonwealth Telecommunications Organisation have facilitated such engagements between companies and governments since their origins, to ensure that informed decisions and agreements are reached about telecommunications and digital tech policy and practice across the world. However, despite the neo-liberal hegemony that aspires to roll back the role of government, it is still governments that wield the political power – rightly so.

Recognising this, private sector companies have worked assiduously over the past three decades to increase their influence over the UN system through direct funding, sponsorship, and technical “expert” advice (see my A new UN for a new (and better) global order (Part One): seven challenges and A new UN for a new (and better) global order (Part Two): seven solutions for seven challenges). This has been particularly so with respect to the digital tech sector, and was clearly evident in the origins and evolution of the processes leading up to the creation of the Office of the UN Secretary-General’s Tech Envoy and thus the Global Digital Compact (see my critique of these).

In conclusionConstructive criticisms of the Global Digital Compact are always welcome. There is, though, a strange irony that representatives of the very interests that played such a strong role in shaping the GDC should now be criticising the way it has developed. My earlier strident criticisms of the GDC were in part that it already reflected too much private sector interest, and that it would do little in practice to mitigate the very considerable harms and digital enslavement caused through the design and use of digital tech (see my Use it or lose it – our freedom). Perhaps I should therefore be grateful that computer scientists and corporate interests are so critical of the draft. This raises some important questions that could be explored in much further detail:

Could the architecture of the Internet and Web have been designed differently so as to ensure that it was not used to cause the harms and abuses that are so prevalent today? My hunch is that the answer to this is “yes”, but that it would have been much more difficult, and would have required very considerable more work and thought about its design at that early stage.Are those who designed and created the Internet and Web responsible for these harms? Again my answer to this is “yes”, but I appreciate that not everyone will accept this. In origin, the earliest engineers and computer scientists working in this field were focused primarily on the “science” of these innovative technologies. I have never asked them the extent to which they considered the ethics of what they were doing at that time, or how much they examined the potential unintended consequences. However, almost all these “scientists” were the products of an education system and “scientific community” that was grounded in empirical-analytic science and logical positivism (see my critique in The Place of Geography ). Moreover, these scientific communities were always closely engaged with private sector companies (and indeed with the USAn military-industrial complex). There is little doubt that the evolution of the Internet and Web over the last 20 years has been driven primarily by the interests of private sector companies, and they too must be brought to justice with respect to the damage they cause. As for the signatories of this Open Letter, if they claim to be responsible for its positive aspects, then they should also accept that they are responsible for its more reprehensible features. What do we do now about it? This is the really important question, and one that is too complex for those involved in the Gobal Digital Compact to resolve. At best, the GDC can perhaps be seen as a statement of intent by those with interests in promulgating it. It can be ignored or kicked into the long grass. It is impossible to reach a sensible conclusion to these discussions in time for the so-called Summit of the Future in three months’ time. In the meanwhile, all of us who are interested in the evolution of digital technologies in the interests of the world’s poorest and most marginalised must continue to work tirelessely truly to serve their interests. One way we can do this is to work closely with those from diametrically opposed views to try to convict them of their responsibility to craft a fairer, less malevolent digital infrastructure. The geni is out of the box, but it is surely not beyond the realms of human ability to tame and control it. The “scientists” behind the Internet need to step up to their responsibilities to humanity, and start playing a new tune. Some are indeed doing just this, but we need many more to step up to the mark. The so called “bottom up, collaborative and inclusive model of Internet governance” has not well “served the world for the past half century”. It has served some incredibly well, but has largely ignored the interests of the poorest and most marginalised, and has done immeasurable harm to many others. Governments have a fundamental role in helping scientists and companies to make a constructive difference through approproiate regulation and legislation. Whether or not they will choose to do so is another matter entirely.March 26, 2024

Use it or lose it – our freedom

I have written elsewhere at some length on digital enslavement, the ways in which citizens across the world are increasingly being forced into sharing their data with global corporations who then profit from their use and sale (see: Freedom, enslavement and the digital barons and Power hierarchies and digital oppression). A recent journey on the London Underground (metro or subway for non-English speakers) reinforced this point and made me increasingly concerned, nay frightened, by the potential dystopia into which “we” are blindly walking, or (un)subtly being cajoled into accepting. Let me tell the tale, and then draw five conclusions. I end with some practical suggestions for reclaiming our freedom.

Transport for London (TfL) created the Oystercard in 2003 as a pre-paid card through which customers could pay for travelling on various forms of transport in London. It was marketed widely because it was easy to use; TfL have nevertheless gained a vast amount of data about passenger journeys from its use. I have always topped mine up with cash so that my financial expenditure on bank cards could not be linked directly with my travel. I also have a railcard that enables me to get reductions on certain forms of travel, but have long resisted linking this to anything else. Incidentally, I likewise refuse to use mobile payment apps such as Apple Pay, Venmo, Google Pay or ParrotMob, because I do not want them to exploit me further by using my data to generate additional profits at my expense. However, the price reduction on London travel by linking my railcard to my Oyster card has “persuaded” me in the end to link the two. Interestingly, I was not able to do this myself, and because there was no longer a ticket office I had to ask for assistance from the one TfL employee in the vicinity, who was overseeing control and security for 10 or more gates at one of London’s busiest terminals. I was very pleasantly surprised by how helpful and professional he was. He agreed that I was unable to do this myself, but he kindly took me to one of the ticket machines where he could access the relevant links and make the connection. The machine, though, did not take cash and so I could not top the card up; it would of course have accepted a payment card. I had to go back to the kind assistant, who then found the one machine in the area that did indeed take cash. En passim, he mentioned that in the future the machines will only take cards, and that it is likely that the Oyster card will soon be phased out to be replaced solely by bank card, or mobile payments (see many discussions, posts, documents and reports on TfL’s Project Proteus).

I tell this tale at some length because it perfectly captures the six interconnected aspects of our increasing entrapment, exploitation and enslavement through the use of digital tech that I wish to address here. Most will find the above account commonplace and innocent. I don’t, and I tell the story as a cautionary tale in the hope that it will help more people resist our ever increasing digital oppression. The meaning of the title should be clear. If we don’t use cash, through which it is extremely difficult to trace our movements and expenditure, we will lose it, and with it the freedom not to be surveilled and not to be exploited through the extraction of our personal data.

We increasingly have no option: cash or nothingFrom a consumer perspective, it is remarkable how swiftly a “no cash” policy has come upon us. We are told that it is much easier to use cards, it is quicker, and we don’t have to carry around heavy weights of cash. A website aimed at foreign tourists, for example, notes that “Alas, various forms of transport – such as London buses – cannot even accept cash payments. Where cash is accepted, it is also often the most expensive way to pay. Cash is thus best avoided”

But how true really is this? If the machines are not working it can take much longer to pay by card and sometimes it is impossible; paying cash is swift when there is a competent human behind the till; and paper money really is not very heavy. Think of what we lose: the beauty of banknotes (see Virginia Hewitt’s Beauty and the Banknote, as well as the work she and I did together on banknotes in eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union); the feel of “real” money, rather than just a virtual transaction; and, above all else, it cannot easily be traced back to us as individuals. We are incresingly being forced into using cards not for these claimed benefits , but rather because it is in the interest of companies that we do so. What is particularlty worrying is that it is increasingly becoming impossible not to use cards. Even in such lovely, quirky coffee shops such as Store Street Espresso, I had to use a card.

The expanding use of cards increases the extent to which we are being tracked and monitoredAt a relatively benign level, it is often argued that people make a conscious choice, and weigh up the relative benefits of using a card or not. However, I wonder how many people really do understand just how much information they are giving away when they use their bank or payment cards. How many are happy that they are being exploited in this way? Just as social media platforms extract vastly more data than most people realise (see Matilda Davies‘ recent piece on Every scary thing Meta knows about me — and you), so too do cards of all sorts, from credit and debit cards, to loyalty cards, to payments card and beyond. Again, the key point here is the rapidly growing scale at which this is happening. Not only, do we increasingly have to use cards, but the interconnectedness of the systems means that the extent to which we are being tracked and our data extracted is also dramatically on the increase. Why have we become so inured to this?

Our real-time travel is increasingly being connected to our expenditure, behaviours and purchasesNot only are our past purchases, transport journeys, and behaviours being tracked and analysed, but with the greater power of data management systems and ever more sophisticated machine learning algorithms, this information is now being used increasingly in real time to ensnare and exploit us. When these data are then cross-linked to biometric records and security cameras we become even more entrapped and exploitable by those who use and supply these technologies. Surfshark, for example, calculates that London has the fourth highest city density of CCTV in the world at 499 cameras per square km (read to the end to discover which are the top three citites – I was surprised!). Even using cash in London is now only a partial means of escaping from the ever greater real-time machine surveillance by state apparatuses, and enslavement by private sector companies.

Who benefits? Is it ever in our interests?How much do we really benefit from such digital enslavement? Proponents of the use of digital tech in this way always point to the potential benefits of going cashless: it is quicker and easier; customers benefit from companies passing on savings from no longer employing human staff; and it is more consistent and accurate. Even if these were true, is it actually in the interests of citizen consumers? People will clearly respond in different ways, depending on their own circumstances, and how much they value their privacy and personal security. However, those who have lived in a different world, the world of the past, know that systems did indeed work then, and that the supposed benefits of digital tech are very much less than is claimed. Let me give but two examples:

First, most payment machines at railway stations (certainly in the area around London) are poorly designed and it is often very difficult to find the best fare for a particular route. I have always found the staff at ticket offices to be much more knowledgeable about the best tickets to buy, and the complete transaction is frequently therefore swifter when talking to a human than using a machine. Machines also frequently do not work, which causes chaos. The difficulties that many elederly people and those with disablities have in using the machines is also of particular concenr.Second, the use of digital tech in this way deliberately limits human interaction. Yet we know that communal interaction is essential for human life. Increasing evidence suggests that rising mental health issues are in part due to this loss of real and physical regular communication, as a result of this being mediated by digital tech. Buying a ticket from a human actually requires communication, and can be a very valuable opportunity, especially for the lonely or the elderly. It also provides a reminder of exactly how much one is spending, esdecially if cash is used. Just passing a payment card over a device often means that customers have little knowledge of exactly what they are paying, and as a result we can frequently pay much more than we had intended.It is surely the companies who benefit most from the implementation and use of digital tech, rather than citizen consumers. The companies who provide the tech, both hardware and software have all benefitted hugely from a shift from human labour to digital. So too have those companies providing the services, be they train operators or the digital finance institutions. When these become integrated as discussed above, the potential profits from combining data from different sources become even higher. Moreover, our data is then sold to others who also use it to enhance their profits. All this is extraction of profit from our individual actions (travelling and purchasing), and as we increasingly have fewer and fewer options, we increasingly lose our freedom and become enslaved.

Another dimension to this balance equation of “who benefits?” concerns the employment of staff. Lack of data makes it extremely difficult to calculate the overall costs and benefits of replacing human staff by machines, but companies are unlikely to make this transition if they did not see it in their long term interests. Moreover, replacing railway staff by machines reduces the risk of strike action by staff, thus making the system more reliable from the companies’ and citizen consumers’ perspectives. The dehumanisation of labour, though, is a very important issue in itself, and many staff made redundant in this process are unlikely to gain jobs in the tech sector that replaces them. It was therefore a very positive move in October 2023 when the UK Government rejected the planned closure of hundreds of ticket stations across the country in response to the most responded to public consultation of all time. The British public, when asked, clearly do not see much of this digitisation to be in their real interests.

The security dangersThere are also very real security dangers associated with the increased use of digital payments systems and cards. These come in two main forms: the dangers of immediate theft and loss of identity for citizen consumers; and the wider threat to companies and individuals of being hacked.

First, the use of digital systems, especially when so much identity and financial information is stored on our mobile phones, means that it is much easier for criminals to steal such integrated information than it was previously, when everything was separated out. In the past, we did not often carry very large sums of cash around with us and few of us ever carried our passports or other identity documents, and yet those who steal mobile devices and access the information on them today are able to gain very rich rewards. Even just losing a phone can be devastating for many people.Second, the hacking risks for both companies and individuals remain very high. Imagine the impact were criminals and/or foreign states to close down all of the ticket machines across rail networks, or interfere with signalling networks. Such critical infrastructures remain vulnerable (see list of significant incidents by CSIS), and it is only a matter of time before more attacks are experienced. Banking systems are also vulnerable, with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace listing some 200 cyber incidents targeting financial institutions between 2007 and 2022. Such incidents affect services, but other hacks are focused on the acquisition of identity-related information that affects some or all users of a particular service. There have for example been several hacks that have affected TfL customers, notably the 2020 report that Oyster Online accounts had been accessed maliciously, and the 2023 report that the Russian ransomware group C10p had attached a TfL supplier with 13,000 customer contact details being compromised.There is no doubt that increasingly integrated data sets containing information about our identities, our location and travel patterns, our finances, and our behaviours make us more vulnerable to financial and identity theft than was previously the case. This places additional burdens on us to put in place our own safety and security mechanisms if we do not want to be overhelmed by those who use digital tech for malicious purposes.

Freedoms and digital enslavementFreedom is the power to act, speak and think how we want; we are enslaved if we lose that freedom of choice. The above examples suggest that we increasingly have very much less choice and power to act how we choose to by those who restrict the ways in which we purchase goods; we are thus becoming enslaved. Increasingly we cannot avoid being surveilled and our data extracted from us when we travel in London, or indeed in many other places. We are being forced to use cards that enable us to be identified everywhere that we travel within the city. Imagine what a “malign actor” (state, company or civil society) could do with these data?

Moreover, I suggest that those who restrict our freedoms and enslave us in this way are acting very deliberately in their own interests, which are mainly pecuniary. We are moving ever more into what might be considered as a new “mode of production” whereby surplus profit is generated from our very selves. Worryingly, that is not so different from the profit generated from the harsh manual labour of slaves. It is a gentler form of slavery to be sure, softer, less immediately visible, and perhaps even more insidious. But it is no less real. I am not the first to refer to digital slavery in my written work (see for example Chisnall, 2020, who focuses especially on “alienation from self”), but it is a notion with which I have been grappling for several years, and the purpose of this post is very much to try to increase wider awareness of thse complex and difficult issues.

Reclaiming our freedomThere are many ways in our daily lives through which we can seek to resist this dangerous trend, and reclaim our freedom, the most important of which I currently see as being the following: