Jason Y. Ng's Blog

August 28, 2017

Seeing Joshua 探之鋒

“We are here to visit a friend,” I said to the guard at the entrance.

Tiffany, Joshua Wong Chi-fung’s long-time girlfriend, trailed behind me. It was our first time visiting Joshua at Pik Uk Correctional Institution and neither of us quite knew what to expect.

Joshua Wong, behind bars

Joshua Wong, behind bars

“Has your friend been convicted?” asked the guard. We nodded in unison. There are different visiting hours and rules for suspects and convicts. Each month, convicts may receive up to two half-hour visits from friends and family, plus two additional visits from immediate family upon request.

The guard pointed to the left and told us to register at the reception office. “I saw your taxi pass by earlier,” he said while eyeing a pair of camera-wielding paparazzi on the prowl. “Next time you can tell the driver to pull up here to spare you the walk.”

At the reception counter, Officer Wong took our identity cards and checked them against the “List.” Each inmate is allowed to grant visitation rights to no more than 10 friends and family members—anyone not on the List will be turned away. Tiff was confidant that both of our names had been added; she had triple-checked that with Joshua’s attorney ahead of time.

“Miss, you’re okay. But the second visitor, Mr. Ng, your name doesn’t quite match our record. The inmate submitted a slightly different Chinese surname,” said Officer Wong. I knew about Joshua’s dyslexic tendencies.

“But don’t worry,” the officer assured, “I can fix that for you if you would just give me a minute.”

I thanked him and asked if I could bring pen and paper with me.

“Sorry, but no phone, no notebook, no nothing—you can’t bring anything in other than your ID card. Rules are rules.”

Pik Uk Prison in Sai Kong

Pik Uk Prison in Sai Kong

Tiff and I exited the reception office and headed straight to the main building, almost sprinting to evade the two relentless paparazzi. Once inside, we deposited our belongings in a locker and walked through an X-ray gantry much like the ones at the airport. Tiff held on to a bag of personal supplies for Joshua.

Visitors are permitted to bring basic items for inmates, but they must meet stringent prison requirements. Tiff knew the only way to guarantee compliance was to purchase everything—from notebooks to batteries and undergarment—at the general store near Lai Chi Kok Reception Centre, where Joshua and the other two convicted student activists, Nathan Law Kwun-chung and Alex Chow Yong-kang, spent their first night after their sentencing.

We were told to take a seat and wait for our number to be called. There were a half-dozen other visitors in the waiting room. Tiff and I entertained ourselves by watching the news on the overhead television set. Paul Lam, Chairman of the Hong Kong Bar Association, was telling reporters that the jailing of Joshua and other activists was not politically motivated. Tiff rolled her eyes and focused on something else.

15 minutes later, an officer called out several numbers including ours. Everyone in the waiting room got up and walked in a single file towards the narrow visiting area. Tiff and I located Joshua’s booth and there he was: the same scrawny boy with a different haircut. He flashed a Cheshire cat smile, clearly elated to see his girlfriend. In an instant, I went from second visitor to third wheel.

Tiff picked up the handset and started to chirp. I saw Joshua’s lips move but couldn’t hear him. The thick glass walls separating prisoners from visitors were certifiably soundproof. What did come through, however, was his good spirits—none of the prison weariness had rubbed off on him.

Tiff spoke in rapid-fire spurts, updating Joshua on personal and political matters with determined efficiency. She also referred to the notes scribbled on her palms. Joshua alternately nodded and spoke, all the while smiling like a kid seeing snowflakes for the first time. If it weren’t for his brown prison clothes, I wouldn’t have guessed that he was serving a six-month sentence.

While they talked, a smiling prison guard saw me standing behind Tiff and walked over to offer me a chair. I declined but thanked him profusely.

As seen on TV

As seen on TV

“Your turn,” Tiff said, handing me the handset after some 10 minutes. Mindful that every second I took would be one fewer for the two of them, I rushed through what I needed to discuss with Joshua. I also told him about Typhoon Hato and Chris Patten’s article in The Financial Times condemning his imprisonment. He nodded—I suspected he already knew all that from watching the news on TV.

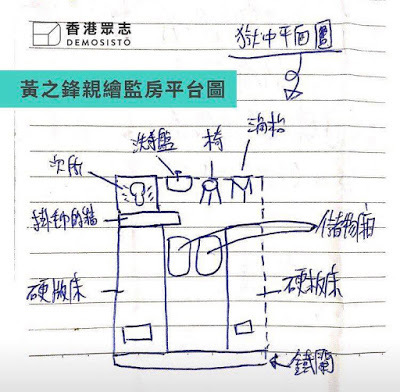

I was most concerned about Joshua’s living conditions and bombarded him with questions. He told me the juvenile ward was surprisingly airy, and that most nights he could barely feel the summer heat. “I even need a thin blanket at night,” he said. “It’s much better than sleeping on concrete during Occupy.”

The food is nothing to write home about: plain rice, chicken wings and steamed vegetables. He shares a tiny cell with another minor inmate, who was convicted for illegal drug use—as most juvenile delinquents at Pik Uk were.

I asked him about any abuse, and he assured me there had been none whatsoever. He had just completed a seven-day “orientation” and a new routine would begin next week. He was expected to begin language and maths classes with other young inmates. He worried somewhat about the physical training—jogging and marching—as he isn’t the athletic type and doesn’t answer well to strict commands.

I asked him what the hardest part was about being behind bars. “Passing the time,” he sighed. “Time crawls in here. Every day I rack my brain to keep myself occupied.” He had nearly finished the six books that visitors are allowed to bring him each month.

Joshua's cell, drawn by him

Joshua's cell, drawn by him

I wanted to know if he had a message for his supporters.

“Please tell everyone I’m doing fine and not to worry about me. Instead, ask them to help Demosisto in any way they can,” he said, referring to his pro-democracy political party.

“The majority of our core members are, or will soon be, in jail,” he added, shaking his head in frustration. “We need to keep our party running and get ready for the upcoming by-election to fill Nathan’s Legco seat.” Weeks before Demosisto’s chairman Nathan Law Kwun-chung went to prison, he was striped of his lawmaker title for straying from the prescribed oath when he was sworn in.

“Among all the opposition parties in Hong Kong, we have come under the heaviest attack. But we won’t give up.” There was indignation and defiance in his voice.

The rest of the 30 minutes went by quickly. We knew time was up when several uniformed officers suddenly appeared to escort the inmates back to their cells. Joshua got up and waved goodbye, training his eyes on Tiff and still smiling from ear to ear. It was sweet and heartbreaking at once.

On our way back to town, I replayed the visit in my head. All things considered, Joshua has adjusted well to the new environment. As much as he struggles to pass the time, his timetable will fill up once his habit of journal keeping and letter writing takes hold and he gets his radio and newspaper subscription.

What’s more, based on my limited interaction with the staff, everyone in the juvenile ward seemed to be courteous and helpful. Nothing suggested Joshua was being treated with anything but respect and professionalism. That’s a marked departure from the many horror stories about youth incarceration I’ve read in the local press. Perhaps his fame had afforded him some protection.

All that may change after Joshua turns 21 in October, when he will be transferred to the adult ward. There, he will be required to work every day—be it carpentry, laundry, kitchen duties or repairs and maintenance—to earn his keep. And he will have to adapt to a new routine all over again.

____________________________________

A shorter version of this article appeared on SCMP.com under the title "Behind bars, Hong Kong political activist Joshua Wong remains in good spirits."

As posted on SCMP.com

As posted on SCMP.com

Tiffany, Joshua Wong Chi-fung’s long-time girlfriend, trailed behind me. It was our first time visiting Joshua at Pik Uk Correctional Institution and neither of us quite knew what to expect.

Joshua Wong, behind bars

Joshua Wong, behind bars“Has your friend been convicted?” asked the guard. We nodded in unison. There are different visiting hours and rules for suspects and convicts. Each month, convicts may receive up to two half-hour visits from friends and family, plus two additional visits from immediate family upon request.

The guard pointed to the left and told us to register at the reception office. “I saw your taxi pass by earlier,” he said while eyeing a pair of camera-wielding paparazzi on the prowl. “Next time you can tell the driver to pull up here to spare you the walk.”

At the reception counter, Officer Wong took our identity cards and checked them against the “List.” Each inmate is allowed to grant visitation rights to no more than 10 friends and family members—anyone not on the List will be turned away. Tiff was confidant that both of our names had been added; she had triple-checked that with Joshua’s attorney ahead of time.

“Miss, you’re okay. But the second visitor, Mr. Ng, your name doesn’t quite match our record. The inmate submitted a slightly different Chinese surname,” said Officer Wong. I knew about Joshua’s dyslexic tendencies.

“But don’t worry,” the officer assured, “I can fix that for you if you would just give me a minute.”

I thanked him and asked if I could bring pen and paper with me.

“Sorry, but no phone, no notebook, no nothing—you can’t bring anything in other than your ID card. Rules are rules.”

Pik Uk Prison in Sai Kong

Pik Uk Prison in Sai KongTiff and I exited the reception office and headed straight to the main building, almost sprinting to evade the two relentless paparazzi. Once inside, we deposited our belongings in a locker and walked through an X-ray gantry much like the ones at the airport. Tiff held on to a bag of personal supplies for Joshua.

Visitors are permitted to bring basic items for inmates, but they must meet stringent prison requirements. Tiff knew the only way to guarantee compliance was to purchase everything—from notebooks to batteries and undergarment—at the general store near Lai Chi Kok Reception Centre, where Joshua and the other two convicted student activists, Nathan Law Kwun-chung and Alex Chow Yong-kang, spent their first night after their sentencing.

We were told to take a seat and wait for our number to be called. There were a half-dozen other visitors in the waiting room. Tiff and I entertained ourselves by watching the news on the overhead television set. Paul Lam, Chairman of the Hong Kong Bar Association, was telling reporters that the jailing of Joshua and other activists was not politically motivated. Tiff rolled her eyes and focused on something else.

15 minutes later, an officer called out several numbers including ours. Everyone in the waiting room got up and walked in a single file towards the narrow visiting area. Tiff and I located Joshua’s booth and there he was: the same scrawny boy with a different haircut. He flashed a Cheshire cat smile, clearly elated to see his girlfriend. In an instant, I went from second visitor to third wheel.

Tiff picked up the handset and started to chirp. I saw Joshua’s lips move but couldn’t hear him. The thick glass walls separating prisoners from visitors were certifiably soundproof. What did come through, however, was his good spirits—none of the prison weariness had rubbed off on him.

Tiff spoke in rapid-fire spurts, updating Joshua on personal and political matters with determined efficiency. She also referred to the notes scribbled on her palms. Joshua alternately nodded and spoke, all the while smiling like a kid seeing snowflakes for the first time. If it weren’t for his brown prison clothes, I wouldn’t have guessed that he was serving a six-month sentence.

While they talked, a smiling prison guard saw me standing behind Tiff and walked over to offer me a chair. I declined but thanked him profusely.

As seen on TV

As seen on TV“Your turn,” Tiff said, handing me the handset after some 10 minutes. Mindful that every second I took would be one fewer for the two of them, I rushed through what I needed to discuss with Joshua. I also told him about Typhoon Hato and Chris Patten’s article in The Financial Times condemning his imprisonment. He nodded—I suspected he already knew all that from watching the news on TV.

I was most concerned about Joshua’s living conditions and bombarded him with questions. He told me the juvenile ward was surprisingly airy, and that most nights he could barely feel the summer heat. “I even need a thin blanket at night,” he said. “It’s much better than sleeping on concrete during Occupy.”

The food is nothing to write home about: plain rice, chicken wings and steamed vegetables. He shares a tiny cell with another minor inmate, who was convicted for illegal drug use—as most juvenile delinquents at Pik Uk were.

I asked him about any abuse, and he assured me there had been none whatsoever. He had just completed a seven-day “orientation” and a new routine would begin next week. He was expected to begin language and maths classes with other young inmates. He worried somewhat about the physical training—jogging and marching—as he isn’t the athletic type and doesn’t answer well to strict commands.

I asked him what the hardest part was about being behind bars. “Passing the time,” he sighed. “Time crawls in here. Every day I rack my brain to keep myself occupied.” He had nearly finished the six books that visitors are allowed to bring him each month.

Joshua's cell, drawn by him

Joshua's cell, drawn by himI wanted to know if he had a message for his supporters.

“Please tell everyone I’m doing fine and not to worry about me. Instead, ask them to help Demosisto in any way they can,” he said, referring to his pro-democracy political party.

“The majority of our core members are, or will soon be, in jail,” he added, shaking his head in frustration. “We need to keep our party running and get ready for the upcoming by-election to fill Nathan’s Legco seat.” Weeks before Demosisto’s chairman Nathan Law Kwun-chung went to prison, he was striped of his lawmaker title for straying from the prescribed oath when he was sworn in.

“Among all the opposition parties in Hong Kong, we have come under the heaviest attack. But we won’t give up.” There was indignation and defiance in his voice.

The rest of the 30 minutes went by quickly. We knew time was up when several uniformed officers suddenly appeared to escort the inmates back to their cells. Joshua got up and waved goodbye, training his eyes on Tiff and still smiling from ear to ear. It was sweet and heartbreaking at once.

On our way back to town, I replayed the visit in my head. All things considered, Joshua has adjusted well to the new environment. As much as he struggles to pass the time, his timetable will fill up once his habit of journal keeping and letter writing takes hold and he gets his radio and newspaper subscription.

What’s more, based on my limited interaction with the staff, everyone in the juvenile ward seemed to be courteous and helpful. Nothing suggested Joshua was being treated with anything but respect and professionalism. That’s a marked departure from the many horror stories about youth incarceration I’ve read in the local press. Perhaps his fame had afforded him some protection.

All that may change after Joshua turns 21 in October, when he will be transferred to the adult ward. There, he will be required to work every day—be it carpentry, laundry, kitchen duties or repairs and maintenance—to earn his keep. And he will have to adapt to a new routine all over again.

____________________________________

A shorter version of this article appeared on SCMP.com under the title "Behind bars, Hong Kong political activist Joshua Wong remains in good spirits."

As posted on SCMP.com

As posted on SCMP.com

Published on August 28, 2017 03:38

July 28, 2017

Major Yuen to Ground Control 自袁其說

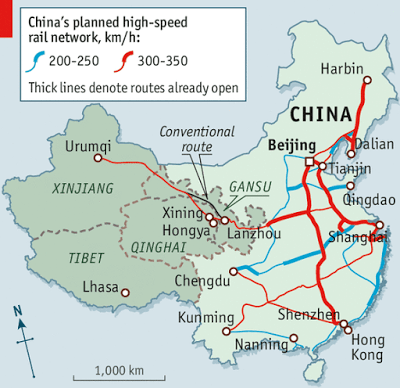

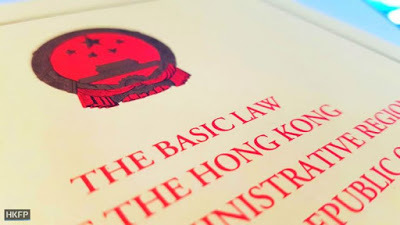

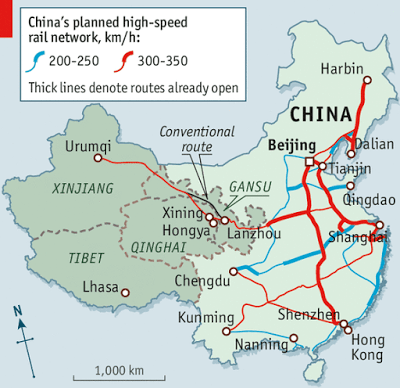

Seven years after Donald Tsang’s administration rammed a funding bill through the legislature to bankroll the cross-border rail link, the SAR government this week unveiled a long-awaited proposal to resolve the border control conundrum. At issue is whether carving out certain areas at the West Kowloon terminal station where mainland officers are given broad criminal and civil jurisdiction will run afoul of the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s mini-constitution.

It is an 84-billion-dollar question that can make or break the controversial infrastructure project. If the government’s proposal falls through, then every time-saving and convenience advantage to justify the rail link’s dizzying price tag is put at risk. But if the plan prevails, it may create a foreign concession of sorts in Hong Kong and open a Pandora’s box of extraterritorial law enforcement.

Justice Secretary Rimsky Yuen

Justice Secretary Rimsky Yuen

The central question is a straightforward one: is the joint checkpoint proposal constitutional?

The answer can be found in Chapter II of the Basic Law which governs the relationship between mainland China and Hong Kong. Articles 18 and 22 prohibit national laws from being applied in Hong Kong (with the exception of matters relating to defence and foreign affairs) and forbid Chinese authorities from interfering in the special administrative region’s affairs. In addition, Article 19 grants Hong Kong courts exclusive jurisdiction over cases that occur anywhere within the territory. That means any attempt to enforce Chinese law on Hong Kong soil—no matter the location or size of the area—is on its face in breach of at least three provisions of the Basic Law.

But the government begs to differ. Justice Secretary Rimsky Yuen Kwok-keung (袁國強) has so far put forward two counter-arguments. First, he argues that the designated areas, once leased to the Central Government, will no longer be part of the SAR territory and therefore outside the jurisdiction of the Basic Law.

Yuen’s argument is plainly circular, especially if you recast his logic as follows: it is constitutional to carve out certain areas because those areas have been carved out of the constitution. If that were true, then by analogy there would be nothing to stop the government from excluding, say, left-handed people from the protection of the Basic Law on the basis that those people will have no such protection once they are excluded.

Does this mean anything to anyone any more?

Does this mean anything to anyone any more?

Second, the Justice Chief invokes Article 20 of the Basic Law, which allows the SAR government to enjoy new powers conferred to it by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC). Bending that provision to serve his purpose, Yuen argues that the SAR government can seek a “new power” from the NPCSC under Article 20 so that it can in turn authorize the mainland authorities to enforce national laws in the designated areas.

In essence, Yuen is asking Beijing to give Hong Kong the power to give Beijing the power to do what Beijing doesn’t currently have the power to do in Hong Kong. Mr. Secretary should get an “A” for creativity and an “F” for logic.

Such illogic aside, many are asking how constitutional lawyers have gotten comfortable with seemingly similar arrangements enjoyed by foreign consulates and “mainland-controlled” areas like the Liaison Office in Sai Ying Pun and the People’s Liberation Army Garrison in Tamar.

Foreign consulates are specifically dealt with in Annex III to the Basic Law, which imports Chinese regulations governing diplomatic privileges in compliance with the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations. Even so, consuls and their staff only enjoy diplomatic rights and not law enforcement powers. What’s more, Hong Kong courts still have full jurisdiction over any illegal acts committed on those premises. The same is true for the Liaison Office and the PLA Garrison.

Expect to see this in the heart of Hong Kong

Expect to see this in the heart of Hong Kong

Then how do other countries address similar issues in their extraterritorial checkpoints, such as the passport control at London’s Eurostar terminal and the U.S. immigration controls at Canadian airports? The answer is simple: they don’t have to. Sovereign nations are free to enter into any border control arrangements with each other as they see fit, because their relationship is not bound by the Basic Law. But ours is.

If the joint checkpoint proposal violates the Basic Law, the next question becomes: are there less invasive alternatives?

Commentators and advocacy groups have tabled a number of options, one of them is to limit the mainland officers’ powers to the performance of immigration and customs controls only, instead of the full criminal and civil jurisdiction currently being proposed. While this scaled-back arrangement still won’t pass constitutional muster, it will at least allay fears that mainland authorities stationed in the heart of Hong Kong may arrest and detain passengers at will—fears that are understandable considering that the missing booksellers incident is still fresh on everyone’s mind.

The most legally viable alternative so far is one that involves a combination of ground and on-board clearance procedures. Based on the current rail network, high-speed trains leaving West Kowloon must make a first stop in either Shenzhen or Guangzhou. Under the “combined approach”, Hong Kong passengers whose final destination is one of those two cities will exit the train and go through a physical checkpoint upon arrival. Those who continue their journey to other destinations will stay in their seats and await immigration officers to check their documents and luggage on board while the train is in transit to the next city.

On-board clearance is typical in Europe and does not cause any travel delay to passengers regardless of their destinations. However, the combined approach will incur additional expenses on the mainland side by requiring physical checkpoints to be set up in Shenzhen and Guangzhou. Therein lies the conflict of interest: mainland authorities see no reason why they should bear any of the cost of linking Hong Kong to their massive high-speed rail system. Hong Kong citizens are the ones who need to figure things out for themselves.

China's high speed rail network

China's high speed rail network

In the coming months, legal experts and government officials will continue to argue over the legality of the joint checkpoint proposal. Already, at least two judicial reviews have been filed to challenge it in local courts. Whereas complicated legal issues may be of little interest to the majority of citizens who prize convenience and connectivity above constitutional principles, they matter even less to the SAR government. For the bureaucrats know, if the stalemate should go on any longer, the NPCSC will have no qualms about issuing yet another interpretation of the Basic Law, just as it so eagerly did before using it to unseat a half-dozen opposition lawmakers who had strayed from their oaths.

That explains the Justice Secretary’s confidence in the rail plan. He too knows that no matter what unsound arguments he puts forth, Beijing will always have the last word. But each time the NPCSC uses its trump card, it chips away at the authority of the Basic Law and make the “one country, two systems” promise mean a little less. And it is again the citizens of Hong Kong who will pay the price—in dollars and in dignity.

____________________________________

This article appeared on SCMP.com as " Why Hong Kong’s justice minister Rimsky Yuen is so sanguine about joint checkpoint for express rail link " and in the South China Morning Post print edition as "Unsound logic from justice chief on express rail checkpoint."

As posted on SCMP.com

As posted on SCMP.com

It is an 84-billion-dollar question that can make or break the controversial infrastructure project. If the government’s proposal falls through, then every time-saving and convenience advantage to justify the rail link’s dizzying price tag is put at risk. But if the plan prevails, it may create a foreign concession of sorts in Hong Kong and open a Pandora’s box of extraterritorial law enforcement.

Justice Secretary Rimsky Yuen

Justice Secretary Rimsky YuenThe central question is a straightforward one: is the joint checkpoint proposal constitutional?

The answer can be found in Chapter II of the Basic Law which governs the relationship between mainland China and Hong Kong. Articles 18 and 22 prohibit national laws from being applied in Hong Kong (with the exception of matters relating to defence and foreign affairs) and forbid Chinese authorities from interfering in the special administrative region’s affairs. In addition, Article 19 grants Hong Kong courts exclusive jurisdiction over cases that occur anywhere within the territory. That means any attempt to enforce Chinese law on Hong Kong soil—no matter the location or size of the area—is on its face in breach of at least three provisions of the Basic Law.

But the government begs to differ. Justice Secretary Rimsky Yuen Kwok-keung (袁國強) has so far put forward two counter-arguments. First, he argues that the designated areas, once leased to the Central Government, will no longer be part of the SAR territory and therefore outside the jurisdiction of the Basic Law.

Yuen’s argument is plainly circular, especially if you recast his logic as follows: it is constitutional to carve out certain areas because those areas have been carved out of the constitution. If that were true, then by analogy there would be nothing to stop the government from excluding, say, left-handed people from the protection of the Basic Law on the basis that those people will have no such protection once they are excluded.

Does this mean anything to anyone any more?

Does this mean anything to anyone any more?Second, the Justice Chief invokes Article 20 of the Basic Law, which allows the SAR government to enjoy new powers conferred to it by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC). Bending that provision to serve his purpose, Yuen argues that the SAR government can seek a “new power” from the NPCSC under Article 20 so that it can in turn authorize the mainland authorities to enforce national laws in the designated areas.

In essence, Yuen is asking Beijing to give Hong Kong the power to give Beijing the power to do what Beijing doesn’t currently have the power to do in Hong Kong. Mr. Secretary should get an “A” for creativity and an “F” for logic.

Such illogic aside, many are asking how constitutional lawyers have gotten comfortable with seemingly similar arrangements enjoyed by foreign consulates and “mainland-controlled” areas like the Liaison Office in Sai Ying Pun and the People’s Liberation Army Garrison in Tamar.

Foreign consulates are specifically dealt with in Annex III to the Basic Law, which imports Chinese regulations governing diplomatic privileges in compliance with the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations. Even so, consuls and their staff only enjoy diplomatic rights and not law enforcement powers. What’s more, Hong Kong courts still have full jurisdiction over any illegal acts committed on those premises. The same is true for the Liaison Office and the PLA Garrison.

Expect to see this in the heart of Hong Kong

Expect to see this in the heart of Hong KongThen how do other countries address similar issues in their extraterritorial checkpoints, such as the passport control at London’s Eurostar terminal and the U.S. immigration controls at Canadian airports? The answer is simple: they don’t have to. Sovereign nations are free to enter into any border control arrangements with each other as they see fit, because their relationship is not bound by the Basic Law. But ours is.

If the joint checkpoint proposal violates the Basic Law, the next question becomes: are there less invasive alternatives?

Commentators and advocacy groups have tabled a number of options, one of them is to limit the mainland officers’ powers to the performance of immigration and customs controls only, instead of the full criminal and civil jurisdiction currently being proposed. While this scaled-back arrangement still won’t pass constitutional muster, it will at least allay fears that mainland authorities stationed in the heart of Hong Kong may arrest and detain passengers at will—fears that are understandable considering that the missing booksellers incident is still fresh on everyone’s mind.

The most legally viable alternative so far is one that involves a combination of ground and on-board clearance procedures. Based on the current rail network, high-speed trains leaving West Kowloon must make a first stop in either Shenzhen or Guangzhou. Under the “combined approach”, Hong Kong passengers whose final destination is one of those two cities will exit the train and go through a physical checkpoint upon arrival. Those who continue their journey to other destinations will stay in their seats and await immigration officers to check their documents and luggage on board while the train is in transit to the next city.

On-board clearance is typical in Europe and does not cause any travel delay to passengers regardless of their destinations. However, the combined approach will incur additional expenses on the mainland side by requiring physical checkpoints to be set up in Shenzhen and Guangzhou. Therein lies the conflict of interest: mainland authorities see no reason why they should bear any of the cost of linking Hong Kong to their massive high-speed rail system. Hong Kong citizens are the ones who need to figure things out for themselves.

China's high speed rail network

China's high speed rail networkIn the coming months, legal experts and government officials will continue to argue over the legality of the joint checkpoint proposal. Already, at least two judicial reviews have been filed to challenge it in local courts. Whereas complicated legal issues may be of little interest to the majority of citizens who prize convenience and connectivity above constitutional principles, they matter even less to the SAR government. For the bureaucrats know, if the stalemate should go on any longer, the NPCSC will have no qualms about issuing yet another interpretation of the Basic Law, just as it so eagerly did before using it to unseat a half-dozen opposition lawmakers who had strayed from their oaths.

That explains the Justice Secretary’s confidence in the rail plan. He too knows that no matter what unsound arguments he puts forth, Beijing will always have the last word. But each time the NPCSC uses its trump card, it chips away at the authority of the Basic Law and make the “one country, two systems” promise mean a little less. And it is again the citizens of Hong Kong who will pay the price—in dollars and in dignity.

____________________________________

This article appeared on SCMP.com as " Why Hong Kong’s justice minister Rimsky Yuen is so sanguine about joint checkpoint for express rail link " and in the South China Morning Post print edition as "Unsound logic from justice chief on express rail checkpoint."

As posted on SCMP.com

As posted on SCMP.com

Published on July 28, 2017 08:02

July 19, 2017

FAQ on 4DQ 四議員宣誓案常見問題

The slow-motion disaster that is Oathgate has now spread from the pro-independence firebrands to the mainstream pro-democracy camp.

After the High Court disqualified localist lawmakers Yau Wai-ching (游蕙禎) and Baggio Leung Chung-hang (梁頌恆) nearly nine months ago, four more members of the Legislative Council (Legco) lost their jobs last Friday. Nathan Law Kwun-chung (羅冠聰), “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung (梁國雄), Lau Siu-lai (劉小麗) and Edward Yiu Chung-yim (姚松炎) had all strayed from the prescribed oath during the swearing-in ceremony. According to the supreme decision handed down by China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC 人大常委會 ) in November, that minor infraction was enough for all of them to each get a pink slip.

If you are wondering how the loss of six seats has affected the balance of power in Hong Kong, you are not alone. The following FAQs are designed to answer that question and posit what is to come.

They're fired

They're fired

Walk me through the numbers before and after Oathgate?

There are a total of 70 seats in Legco, half of which are called “geographical constituencies” (GCs) and other half “functional constituencies” (FCs).

All 35 GCs are directly elected by a broad base of registered voters, which means GC lawmakers are mostly good folks who are accountable to their constituents. By contrast, most of the FCs (30 out of 35) are not democratically elected – they are handpicked by a small circle of committee members within a particular trade group, such as real estate, food and beverage, and retail. With the exception of a number of politically liberal groups like medical professionals, lawyers and social workers, the FC is stacked with pro-Beijing, pro-establishment businessmen who march in lockstep with the government.

Before Oathgate, the opposition held a total of 29 seats in Legco: 19 GCs and 10 FCs. Although the opposition was in the minority in Legco at large (29 out of 70) and within the FC (10 out of 35), they enjoyed a majority in the GC (19 out of 35). After losing six seats in two rounds of disqualification, the opposition is down to 23 seats: 14 GCs and 9 FCs. For the first time since the handover, they have lost their GC majority.

The following table summarises the impact of Oathgate to date:

Number of seats held by opposition Before Oathgate After Oathgate Geographical constituencies 19(majority) 14(minority) Functional constituencies 10(minority) 9(minority) Total 29(minority) 23(minority)

Balance of power shifted

Balance of power shifted

T he opposition has never enjoyed a majority in Legco even before Oathgate. What difference does losing six seats make?

Under the Basic Law, any bill introduced by the government (except for those relating to constitutional issues such as electoral reform or any amendment to the Basic Law) requires a simple majority vote in Legco. With or without Oathgate, the pro-establishment camp has enough votes to rubber stamp any government-led initiatives, such as an anti-subversion bill under Article 23 of the Basic Law or a funding proposal for the high-speed rail link to Shenzhen.

The only thing standing between us and bad government bills is the filibuster (which thwarted C.Y. Leung’s attempt in 2012 to create new ministerial positions to, critics say, enrich his political friends) and public outcry (which forced Tung Chee-hwa 董建華 to withdraw the controversial anti-subversion bill in 2003).

While Oathgate has not affected the overall balance of power in Legco vis-à-vis government-proposed bills, it has tipped the balance by handing the GC majority to the pro-establishment camp.

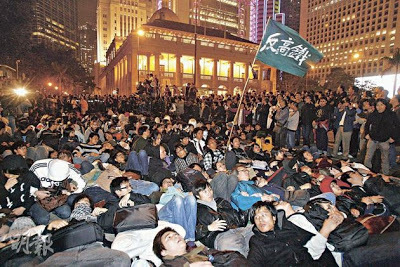

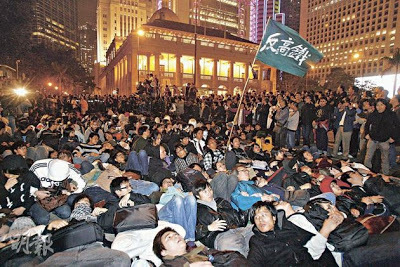

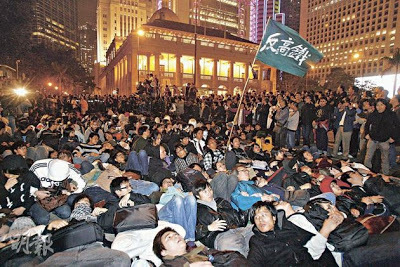

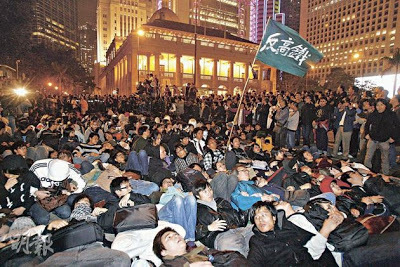

Protest against high-speed rail link

Protest against high-speed rail link

Why does losing the GC majority matter?

The Basic Law contains a bizarre voting rule called the “separate vote count” (分組點票). Unlike government-proposed bills that require a simple majority vote by all 70 Legco seats voting together, any bill introduced by an individual lawmaker must go through two rounds of voting: it must first be passed by the GC before being separately voted on by the FC.

Oathgate has created an opening for the pro-establishment camp to wreak havoc by proposing dangerous bills. Without its GC majority, the opposition has lost the ability to defeat bad bills introduced by their opponents. Going forward, any proposal floated by a lawmaker from the dark side will sail through both the GC and FC during the separate vote count.

One of the first things that the pro-establishment camp will do with its new GC majority is propose an amendment to voting procedures – a motion that only a lawmaker on the Committee on Rules of Procedure can initiate. The goal is to put an end to the filibuster by, for instance, putting a cap on how long or how many times a Legco member can speak when debating a bill or enabling the chairman to cut short the session and proceed to a vote. With both the GC and FC now controlled by Beijing loyalists, there is nothing to stop that amendment from being passed and the opposition can kiss the filibuster goodbye.

The filibuster is currently the opposition’s only effective weapon to delay or derail bad government bills such as funding requests for infrastructure projects that squander billions of taxpayer dollars. Thanks to Oathgate, we stand to lose the only checks and balances against the government led by a chief executive whom we play no part in choosing.

Albert Chan, one of the skilled filibusterers

Albert Chan, one of the skilled filibusterers

Does it mean the government can now pass an anti-subversion law without any resistance?

Remember, any bill introduced by the government, including the anti-subversion bill under Article 23 of the Basic Law, requires only a simple majority vote of all 70 LegCo members voting together. Since the pro-establishment has always enjoyed a majority in Legco at large, the opposition never has sufficient votes to block that bill from being passed whether or not they have those six seats.

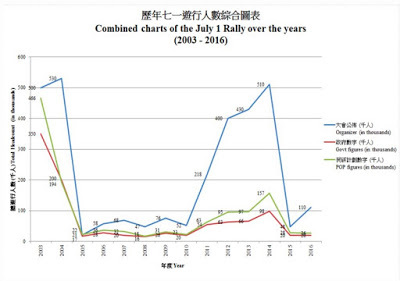

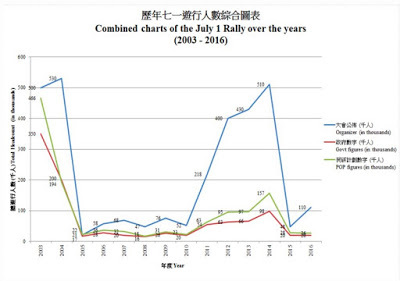

As mentioned earlier, the only things stopping the pro-establishment camp from passing the much-dreaded bill are the filibuster – which is now in jeopardy – and public pressure. The latter remains an effective deterrence because the SAR government cannot afford a repeat of the political crisis that rattled the city in 2003.

Epic July 1st march in 2003

Epic July 1st march in 2003

Why don’t the disqualified lawmakers simply appeal the court rulings?

First, the chances that the High Court rulings will be reversed or set aside are slim. NPCSC decisions are meant to be the ultimate interpretation of the Basic Law and binding on all levels of local courts. As much as appellant court judges may be sympathetic to the opposition’s arguments, their hands are tied.

Second, appeals are costly. Already, the disqualified lawmakers owe millions in counsel and court fees, and because the annulment of their office is retroactive, they may be on the hook for millions more if the government goes after them for paid salaries and expense disbursements. For some of the ousted lawmakers, bankruptcy is the only way out.

Appeals are also time-consuming. It takes months, sometimes years, for a case to move through the court calendar. By the time a ruling is handed down, the pro-establishment will have already completed their handiwork and killed the filibuster by amending the Rules of Procedures using their new GC major.

Appeals take time and money

Appeals take time and money

Wouldn’t order be restored if voters send those lawmakers back in the Legco in the by-elections to fill the vacate seats?

One of the biggest hurdles facing the ousted lawmakers is their eligibility to run for Legco again. In August 2016, the Returning Officers (選舉主任) – bureaucrats who have enormous power and discretion to decide whether an individual is eligible to run – banned several localist candidates from the Legco race on the basis that their declarations of allegiance to the SAR government were “insincere.” There is a high chance that the same political screening will be applied or even tightened in the upcoming by-election to prevent the ousted lawmakers from returning to Legco.

Moreover, any individual who has filed for bankruptcy or received a sentence of three months or more is subject to a five-year moratorium on a Legco run. Nathan Law and “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung, for instance, both face potentially stiff prison terms for their involvement in the occupy movement in 2014 as well as imminent bankruptcy for reasons explained earlier. That means the two will likely not be able to run again until 2024, a political eternity away.

Finally, the earliest that the by-elections can be held is this winter. Even if the unseated lawmakers somehow get over the above hurdles and win back their seats, they may be returning to a very different legislature. By then, the pro-establishment camp will have declawed the opposition by taking away the filibuster.

Nathan Law will try to get voted back in

Nathan Law will try to get voted back in

What can we do now? Are we doomed?

Things are expected to get much worse before they get better.

In the coming months, the High Court is expected to unseat two more lawmakers, Eddie Chu Hoi-dick (朱凱廸) and Cheng Chung-tai (鄭松泰), both of whom had embellished their oaths. The opposition will be mere seats away from losing the critical number in Legco to veto damaging amendments to the Basic Law. Once the pro-establishment camp secures a super-majority it has been salivating over for years to change the constitution as they see fit, the consequences can be catastrophic.

____________________________________

This article appeared on Hong Kong Free Press under the title "FAQ: How might the ejection of 4 more pro-democracy lawmakers alter Hong Kong’s political landscape?"

As posted on hongkongfp.com

As posted on hongkongfp.com

After the High Court disqualified localist lawmakers Yau Wai-ching (游蕙禎) and Baggio Leung Chung-hang (梁頌恆) nearly nine months ago, four more members of the Legislative Council (Legco) lost their jobs last Friday. Nathan Law Kwun-chung (羅冠聰), “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung (梁國雄), Lau Siu-lai (劉小麗) and Edward Yiu Chung-yim (姚松炎) had all strayed from the prescribed oath during the swearing-in ceremony. According to the supreme decision handed down by China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC 人大常委會 ) in November, that minor infraction was enough for all of them to each get a pink slip.

If you are wondering how the loss of six seats has affected the balance of power in Hong Kong, you are not alone. The following FAQs are designed to answer that question and posit what is to come.

They're fired

They're firedWalk me through the numbers before and after Oathgate?

There are a total of 70 seats in Legco, half of which are called “geographical constituencies” (GCs) and other half “functional constituencies” (FCs).

All 35 GCs are directly elected by a broad base of registered voters, which means GC lawmakers are mostly good folks who are accountable to their constituents. By contrast, most of the FCs (30 out of 35) are not democratically elected – they are handpicked by a small circle of committee members within a particular trade group, such as real estate, food and beverage, and retail. With the exception of a number of politically liberal groups like medical professionals, lawyers and social workers, the FC is stacked with pro-Beijing, pro-establishment businessmen who march in lockstep with the government.

Before Oathgate, the opposition held a total of 29 seats in Legco: 19 GCs and 10 FCs. Although the opposition was in the minority in Legco at large (29 out of 70) and within the FC (10 out of 35), they enjoyed a majority in the GC (19 out of 35). After losing six seats in two rounds of disqualification, the opposition is down to 23 seats: 14 GCs and 9 FCs. For the first time since the handover, they have lost their GC majority.

The following table summarises the impact of Oathgate to date:

Number of seats held by opposition Before Oathgate After Oathgate Geographical constituencies 19(majority) 14(minority) Functional constituencies 10(minority) 9(minority) Total 29(minority) 23(minority)

Balance of power shifted

Balance of power shifted

T he opposition has never enjoyed a majority in Legco even before Oathgate. What difference does losing six seats make?

Under the Basic Law, any bill introduced by the government (except for those relating to constitutional issues such as electoral reform or any amendment to the Basic Law) requires a simple majority vote in Legco. With or without Oathgate, the pro-establishment camp has enough votes to rubber stamp any government-led initiatives, such as an anti-subversion bill under Article 23 of the Basic Law or a funding proposal for the high-speed rail link to Shenzhen.

The only thing standing between us and bad government bills is the filibuster (which thwarted C.Y. Leung’s attempt in 2012 to create new ministerial positions to, critics say, enrich his political friends) and public outcry (which forced Tung Chee-hwa 董建華 to withdraw the controversial anti-subversion bill in 2003).

While Oathgate has not affected the overall balance of power in Legco vis-à-vis government-proposed bills, it has tipped the balance by handing the GC majority to the pro-establishment camp.

Protest against high-speed rail link

Protest against high-speed rail linkWhy does losing the GC majority matter?

The Basic Law contains a bizarre voting rule called the “separate vote count” (分組點票). Unlike government-proposed bills that require a simple majority vote by all 70 Legco seats voting together, any bill introduced by an individual lawmaker must go through two rounds of voting: it must first be passed by the GC before being separately voted on by the FC.

Oathgate has created an opening for the pro-establishment camp to wreak havoc by proposing dangerous bills. Without its GC majority, the opposition has lost the ability to defeat bad bills introduced by their opponents. Going forward, any proposal floated by a lawmaker from the dark side will sail through both the GC and FC during the separate vote count.

One of the first things that the pro-establishment camp will do with its new GC majority is propose an amendment to voting procedures – a motion that only a lawmaker on the Committee on Rules of Procedure can initiate. The goal is to put an end to the filibuster by, for instance, putting a cap on how long or how many times a Legco member can speak when debating a bill or enabling the chairman to cut short the session and proceed to a vote. With both the GC and FC now controlled by Beijing loyalists, there is nothing to stop that amendment from being passed and the opposition can kiss the filibuster goodbye.

The filibuster is currently the opposition’s only effective weapon to delay or derail bad government bills such as funding requests for infrastructure projects that squander billions of taxpayer dollars. Thanks to Oathgate, we stand to lose the only checks and balances against the government led by a chief executive whom we play no part in choosing.

Albert Chan, one of the skilled filibusterers

Albert Chan, one of the skilled filibusterersDoes it mean the government can now pass an anti-subversion law without any resistance?

Remember, any bill introduced by the government, including the anti-subversion bill under Article 23 of the Basic Law, requires only a simple majority vote of all 70 LegCo members voting together. Since the pro-establishment has always enjoyed a majority in Legco at large, the opposition never has sufficient votes to block that bill from being passed whether or not they have those six seats.

As mentioned earlier, the only things stopping the pro-establishment camp from passing the much-dreaded bill are the filibuster – which is now in jeopardy – and public pressure. The latter remains an effective deterrence because the SAR government cannot afford a repeat of the political crisis that rattled the city in 2003.

Epic July 1st march in 2003

Epic July 1st march in 2003Why don’t the disqualified lawmakers simply appeal the court rulings?

First, the chances that the High Court rulings will be reversed or set aside are slim. NPCSC decisions are meant to be the ultimate interpretation of the Basic Law and binding on all levels of local courts. As much as appellant court judges may be sympathetic to the opposition’s arguments, their hands are tied.

Second, appeals are costly. Already, the disqualified lawmakers owe millions in counsel and court fees, and because the annulment of their office is retroactive, they may be on the hook for millions more if the government goes after them for paid salaries and expense disbursements. For some of the ousted lawmakers, bankruptcy is the only way out.

Appeals are also time-consuming. It takes months, sometimes years, for a case to move through the court calendar. By the time a ruling is handed down, the pro-establishment will have already completed their handiwork and killed the filibuster by amending the Rules of Procedures using their new GC major.

Appeals take time and money

Appeals take time and moneyWouldn’t order be restored if voters send those lawmakers back in the Legco in the by-elections to fill the vacate seats?

One of the biggest hurdles facing the ousted lawmakers is their eligibility to run for Legco again. In August 2016, the Returning Officers (選舉主任) – bureaucrats who have enormous power and discretion to decide whether an individual is eligible to run – banned several localist candidates from the Legco race on the basis that their declarations of allegiance to the SAR government were “insincere.” There is a high chance that the same political screening will be applied or even tightened in the upcoming by-election to prevent the ousted lawmakers from returning to Legco.

Moreover, any individual who has filed for bankruptcy or received a sentence of three months or more is subject to a five-year moratorium on a Legco run. Nathan Law and “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung, for instance, both face potentially stiff prison terms for their involvement in the occupy movement in 2014 as well as imminent bankruptcy for reasons explained earlier. That means the two will likely not be able to run again until 2024, a political eternity away.

Finally, the earliest that the by-elections can be held is this winter. Even if the unseated lawmakers somehow get over the above hurdles and win back their seats, they may be returning to a very different legislature. By then, the pro-establishment camp will have declawed the opposition by taking away the filibuster.

Nathan Law will try to get voted back in

Nathan Law will try to get voted back inWhat can we do now? Are we doomed?

Things are expected to get much worse before they get better.

In the coming months, the High Court is expected to unseat two more lawmakers, Eddie Chu Hoi-dick (朱凱廸) and Cheng Chung-tai (鄭松泰), both of whom had embellished their oaths. The opposition will be mere seats away from losing the critical number in Legco to veto damaging amendments to the Basic Law. Once the pro-establishment camp secures a super-majority it has been salivating over for years to change the constitution as they see fit, the consequences can be catastrophic.

____________________________________

This article appeared on Hong Kong Free Press under the title "FAQ: How might the ejection of 4 more pro-democracy lawmakers alter Hong Kong’s political landscape?"

As posted on hongkongfp.com

As posted on hongkongfp.com

Published on July 19, 2017 07:34

FAQ on 4DQ 四議員DQ常見問題

The slow-motion disaster that is Oathgate has now spread from the pro-independence firebrands to the mainstream pro-democracy camp.

After the High Court disqualified localist lawmakers Yau Wai-ching (游蕙禎) and Baggio Leung Chung-hang (梁頌恆) nearly nine months ago, four more members of the Legislative Council (Legco) lost their jobs last Friday. Nathan Law Kwun-chung (羅冠聰), “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung (梁國雄), Lau Siu-lai (劉小麗) and Edward Yiu Chung-yim (姚松炎) had all strayed from the prescribed oath during the swearing-in ceremony. According to the supreme decision handed down by China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC 人大常委會 ) in November, that minor infraction was enough for all of them to each get a pink slip.

If you are wondering how the loss of six seats has affected the balance of power in Hong Kong, you are not alone. The following FAQs are designed to answer that question and posit what is to come.

They're fired

They're fired

Walk me through the numbers before and after Oathgate?

There are a total of 70 seats in Legco, half of which are called “geographical constituencies” (GCs) and other half “functional constituencies” (FCs).

All 35 GCs are directly elected by a broad base of registered voters, which means GC lawmakers are mostly good folks who are accountable to their constituents. By contrast, most of the FCs (30 out of 35) are not democratically elected – they are handpicked by a small circle of committee members within a particular trade group, such as real estate, food and beverage, and retail. With the exception of a number of politically liberal groups like medical professionals, lawyers and social workers, the FC is stacked with pro-Beijing, pro-establishment businessmen who march in lockstep with the government.

Before Oathgate, the opposition held a total of 29 seats in Legco: 19 GCs and 10 FCs. Although the opposition was in the minority in Legco at large (29 out of 70) and within the FC (10 out of 35), they enjoyed a majority in the GC (19 out of 35). After losing six seats in two rounds of disqualification, the opposition is down to 23 seats: 14 GCs and 9 FCs. For the first time since the handover, they have lost their GC majority.

The following table summarises the impact of Oathgate to date:

Number of seats held by opposition Before Oathgate After Oathgate Geographical constituencies 19(majority) 14(minority) Functional constituencies 10(minority) 9(minority) Total 29(minority) 23(minority)

Balance of power shifted

Balance of power shifted

T he opposition has never enjoyed a majority in Legco even before Oathgate. What difference does losing six seats make?

Under the Basic Law, any bill introduced by the government (except for those relating to constitutional issues such as electoral reform or any amendment to the Basic Law) requires a simple majority vote in Legco. With or without Oathgate, the pro-establishment camp has enough votes to rubber stamp any government-led initiatives, such as an anti-subversion bill under Article 23 of the Basic Law or a funding proposal for the high-speed rail link to Shenzhen.

The only thing standing between us and bad government bills is the filibuster (which thwarted C.Y. Leung’s attempt in 2012 to create new ministerial positions to, critics say, enrich his political friends) and public outcry (which forced Tung Chee-hwa 董建華 to withdraw the controversial anti-subversion bill in 2003).

While Oathgate has not affected the overall balance of power in Legco vis-à-vis government-proposed bills, it has tipped the balance by handing the GC majority to the pro-establishment camp.

Protest against high-speed rail link

Protest against high-speed rail link

Why does losing the GC majority matter?

The Basic Law contains a bizarre voting rule called the “separate vote count” (分組點票). Unlike government-proposed bills that require a simple majority vote by all 70 Legco seats voting together, any bill introduced by an individual lawmaker must go through two rounds of voting: it must first be passed by the GC before being separately voted on by the FC.

Oathgate has created an opening for the pro-establishment camp to wreak havoc by proposing dangerous bills. Without its GC majority, the opposition has lost the ability to defeat bad bills introduced by their opponents. Going forward, any proposal floated by a lawmaker from the dark side will sail through both the GC and FC during the separate vote count.

One of the first things that the pro-establishment camp will do with its new GC majority is propose an amendment to voting procedures – a motion that only a lawmaker on the Committee on Rules of Procedure can initiate. The goal is to put an end to the filibuster by, for instance, putting a cap on how long or how many times a Legco member can speak when debating a bill or enabling the chairman to cut short the session and proceed to a vote. With both the GC and FC now controlled by Beijing loyalists, there is nothing to stop that amendment from being passed and the opposition can kiss the filibuster goodbye.

The filibuster is currently the opposition’s only effective weapon to delay or derail bad government bills such as funding requests for infrastructure projects that squander billions of taxpayer dollars. Thanks to Oathgate, we stand to lose the only checks and balances against the government led by a chief executive whom we play no part in choosing.

Albert Chan, one of the skilled filibusterers

Albert Chan, one of the skilled filibusterers

Does it mean the government can now pass an anti-subversion law without any resistance?

Remember, any bill introduced by the government, including the anti-subversion bill under Article 23 of the Basic Law, requires only a simple majority vote of all 70 LegCo members voting together. Since the pro-establishment has always enjoyed a majority in Legco at large, the opposition never has sufficient votes to block that bill from being passed whether or not they have those six seats.

As mentioned earlier, the only things stopping the pro-establishment camp from passing the much-dreaded bill are the filibuster – which is now in jeopardy – and public pressure. The latter remains an effective deterrence because the SAR government cannot afford a repeat of the political crisis that rattled the city in 2003.

Epic July 1st march in 2003

Epic July 1st march in 2003

Why don’t the disqualified lawmakers simply appeal the court rulings?

First, the chances that the High Court rulings will be reversed or set aside are slim. NPCSC decisions are meant to be the ultimate interpretation of the Basic Law and binding on all levels of local courts. As much as appellant court judges may be sympathetic to the opposition’s arguments, their hands are tied.

Second, appeals are costly. Already, the disqualified lawmakers owe millions in counsel and court fees, and because the annulment of their office is retroactive, they may be on the hook for millions more if the government goes after them for paid salaries and expense disbursements. For some of the ousted lawmakers, bankruptcy is the only way out.

Appeals are also time-consuming. It takes months, sometimes years, for a case to move through the court calendar. By the time a ruling is handed down, the pro-establishment will have already completed their handiwork and killed the filibuster by amending the Rules of Procedures using their new GC major.

Appeals take time and money

Appeals take time and money

Wouldn’t order be restored if voters send those lawmakers back in the Legco in the by-elections to fill the vacate seats?

One of the biggest hurdles facing the ousted lawmakers is their eligibility to run for Legco again. In August 2016, the Returning Officers (選舉主任) – bureaucrats who have enormous power and discretion to decide whether an individual is eligible to run – banned several localist candidates from the Legco race on the basis that their declarations of allegiance to the SAR government were “insincere.” There is a high chance that the same political screening will be applied or even tightened in the upcoming by-election to prevent the ousted lawmakers from returning to Legco.

Moreover, any individual who has filed for bankruptcy or received a sentence of three months or more is subject to a five-year moratorium on a Legco run. Nathan Law and “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung, for instance, both face potentially stiff prison terms for their involvement in the occupy movement in 2014 as well as imminent bankruptcy for reasons explained earlier. That means the two will likely not be able to run again until 2024, a political eternity away.

Finally, the earliest that the by-elections can be held is this winter. Even if the unseated lawmakers somehow get over the above hurdles and win back their seats, they may be returning to a very different legislature. By then, the pro-establishment camp will have declawed the opposition by taking away the filibuster.

Nathan Law will try to get voted back in

Nathan Law will try to get voted back in

What can we do now? Are we doomed?

Things are expected to get much worse before they get better.

In the coming months, the High Court is expected to unseat two more lawmakers, Eddie Chu Hoi-dick (朱凱廸) and Cheng Chung-tai (鄭松泰), both of whom had embellished their oaths. The opposition will be mere seats away from losing the critical number in Legco to veto damaging amendments to the Basic Law. Once the pro-establishment camp secures a super-majority it has been salivating over for years to change the constitution as they see fit, the consequences can be catastrophic.

____________________________________

This article appeared on Hong Kong Free Press under the title "FAQ: How might the ejection of 4 more pro-democracy lawmakers alter Hong Kong’s political landscape?"

As posted on hongkongfp.com

As posted on hongkongfp.com

After the High Court disqualified localist lawmakers Yau Wai-ching (游蕙禎) and Baggio Leung Chung-hang (梁頌恆) nearly nine months ago, four more members of the Legislative Council (Legco) lost their jobs last Friday. Nathan Law Kwun-chung (羅冠聰), “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung (梁國雄), Lau Siu-lai (劉小麗) and Edward Yiu Chung-yim (姚松炎) had all strayed from the prescribed oath during the swearing-in ceremony. According to the supreme decision handed down by China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC 人大常委會 ) in November, that minor infraction was enough for all of them to each get a pink slip.

If you are wondering how the loss of six seats has affected the balance of power in Hong Kong, you are not alone. The following FAQs are designed to answer that question and posit what is to come.

They're fired

They're firedWalk me through the numbers before and after Oathgate?

There are a total of 70 seats in Legco, half of which are called “geographical constituencies” (GCs) and other half “functional constituencies” (FCs).

All 35 GCs are directly elected by a broad base of registered voters, which means GC lawmakers are mostly good folks who are accountable to their constituents. By contrast, most of the FCs (30 out of 35) are not democratically elected – they are handpicked by a small circle of committee members within a particular trade group, such as real estate, food and beverage, and retail. With the exception of a number of politically liberal groups like medical professionals, lawyers and social workers, the FC is stacked with pro-Beijing, pro-establishment businessmen who march in lockstep with the government.

Before Oathgate, the opposition held a total of 29 seats in Legco: 19 GCs and 10 FCs. Although the opposition was in the minority in Legco at large (29 out of 70) and within the FC (10 out of 35), they enjoyed a majority in the GC (19 out of 35). After losing six seats in two rounds of disqualification, the opposition is down to 23 seats: 14 GCs and 9 FCs. For the first time since the handover, they have lost their GC majority.

The following table summarises the impact of Oathgate to date:

Number of seats held by opposition Before Oathgate After Oathgate Geographical constituencies 19(majority) 14(minority) Functional constituencies 10(minority) 9(minority) Total 29(minority) 23(minority)

Balance of power shifted

Balance of power shifted

T he opposition has never enjoyed a majority in Legco even before Oathgate. What difference does losing six seats make?

Under the Basic Law, any bill introduced by the government (except for those relating to constitutional issues such as electoral reform or any amendment to the Basic Law) requires a simple majority vote in Legco. With or without Oathgate, the pro-establishment camp has enough votes to rubber stamp any government-led initiatives, such as an anti-subversion bill under Article 23 of the Basic Law or a funding proposal for the high-speed rail link to Shenzhen.

The only thing standing between us and bad government bills is the filibuster (which thwarted C.Y. Leung’s attempt in 2012 to create new ministerial positions to, critics say, enrich his political friends) and public outcry (which forced Tung Chee-hwa 董建華 to withdraw the controversial anti-subversion bill in 2003).

While Oathgate has not affected the overall balance of power in Legco vis-à-vis government-proposed bills, it has tipped the balance by handing the GC majority to the pro-establishment camp.

Protest against high-speed rail link

Protest against high-speed rail linkWhy does losing the GC majority matter?

The Basic Law contains a bizarre voting rule called the “separate vote count” (分組點票). Unlike government-proposed bills that require a simple majority vote by all 70 Legco seats voting together, any bill introduced by an individual lawmaker must go through two rounds of voting: it must first be passed by the GC before being separately voted on by the FC.

Oathgate has created an opening for the pro-establishment camp to wreak havoc by proposing dangerous bills. Without its GC majority, the opposition has lost the ability to defeat bad bills introduced by their opponents. Going forward, any proposal floated by a lawmaker from the dark side will sail through both the GC and FC during the separate vote count.

One of the first things that the pro-establishment camp will do with its new GC majority is propose an amendment to voting procedures – a motion that only a lawmaker on the Committee on Rules of Procedure can initiate. The goal is to put an end to the filibuster by, for instance, putting a cap on how long or how many times a Legco member can speak when debating a bill or enabling the chairman to cut short the session and proceed to a vote. With both the GC and FC now controlled by Beijing loyalists, there is nothing to stop that amendment from being passed and the opposition can kiss the filibuster goodbye.

The filibuster is currently the opposition’s only effective weapon to delay or derail bad government bills such as funding requests for infrastructure projects that squander billions of taxpayer dollars. Thanks to Oathgate, we stand to lose the only checks and balances against the government led by a chief executive whom we play no part in choosing.

Albert Chan, one of the skilled filibusterers

Albert Chan, one of the skilled filibusterersDoes it mean the government can now pass an anti-subversion law without any resistance?

Remember, any bill introduced by the government, including the anti-subversion bill under Article 23 of the Basic Law, requires only a simple majority vote of all 70 LegCo members voting together. Since the pro-establishment has always enjoyed a majority in Legco at large, the opposition never has sufficient votes to block that bill from being passed whether or not they have those six seats.

As mentioned earlier, the only things stopping the pro-establishment camp from passing the much-dreaded bill are the filibuster – which is now in jeopardy – and public pressure. The latter remains an effective deterrence because the SAR government cannot afford a repeat of the political crisis that rattled the city in 2003.

Epic July 1st march in 2003

Epic July 1st march in 2003Why don’t the disqualified lawmakers simply appeal the court rulings?

First, the chances that the High Court rulings will be reversed or set aside are slim. NPCSC decisions are meant to be the ultimate interpretation of the Basic Law and binding on all levels of local courts. As much as appellant court judges may be sympathetic to the opposition’s arguments, their hands are tied.

Second, appeals are costly. Already, the disqualified lawmakers owe millions in counsel and court fees, and because the annulment of their office is retroactive, they may be on the hook for millions more if the government goes after them for paid salaries and expense disbursements. For some of the ousted lawmakers, bankruptcy is the only way out.

Appeals are also time-consuming. It takes months, sometimes years, for a case to move through the court calendar. By the time a ruling is handed down, the pro-establishment will have already completed their handiwork and killed the filibuster by amending the Rules of Procedures using their new GC major.

Appeals take time and money

Appeals take time and moneyWouldn’t order be restored if voters send those lawmakers back in the Legco in the by-elections to fill the vacate seats?

One of the biggest hurdles facing the ousted lawmakers is their eligibility to run for Legco again. In August 2016, the Returning Officers (選舉主任) – bureaucrats who have enormous power and discretion to decide whether an individual is eligible to run – banned several localist candidates from the Legco race on the basis that their declarations of allegiance to the SAR government were “insincere.” There is a high chance that the same political screening will be applied or even tightened in the upcoming by-election to prevent the ousted lawmakers from returning to Legco.

Moreover, any individual who has filed for bankruptcy or received a sentence of three months or more is subject to a five-year moratorium on a Legco run. Nathan Law and “Long Hair” Leung Kwok-hung, for instance, both face potentially stiff prison terms for their involvement in the occupy movement in 2014 as well as imminent bankruptcy for reasons explained earlier. That means the two will likely not be able to run again until 2024, a political eternity away.

Finally, the earliest that the by-elections can be held is this winter. Even if the unseated lawmakers somehow get over the above hurdles and win back their seats, they may be returning to a very different legislature. By then, the pro-establishment camp will have declawed the opposition by taking away the filibuster.

Nathan Law will try to get voted back in

Nathan Law will try to get voted back inWhat can we do now? Are we doomed?

Things are expected to get much worse before they get better.

In the coming months, the High Court is expected to unseat two more lawmakers, Eddie Chu Hoi-dick (朱凱廸) and Cheng Chung-tai (鄭松泰), both of whom had embellished their oaths. The opposition will be mere seats away from losing the critical number in Legco to veto damaging amendments to the Basic Law. Once the pro-establishment camp secures a super-majority it has been salivating over for years to change the constitution as they see fit, the consequences can be catastrophic.

____________________________________

This article appeared on Hong Kong Free Press under the title "FAQ: How might the ejection of 4 more pro-democracy lawmakers alter Hong Kong’s political landscape?"

As posted on hongkongfp.com

As posted on hongkongfp.com

Published on July 19, 2017 07:34

July 17, 2017

Going Too Far 官逼民反

On Thursday evening, Chinese dissident and political prisoner Liu Xiaobo died from liver cancer in a Shenyang Hospital. Liu was, as the Western press sharply pointed out, the first Nobel Peace Prize laureate to die in custody since Carl von Ossietzky did in Nazi Germany in 1938. Supporters the world over mourned the death of a man who lived and died a hero. The only crime he ever committed was penning a proposal that maps out a bloodless path for his country to democratise.

Liu lived and died a hero

Liu lived and died a hero

Then on Friday afternoon, Beijing’s long arm stretched across the border and reached into Hong Kong’s courtroom. Bound by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee’s decision on oath-taking etiquettes, the Hong Kong High Court ruled to unseat four democratically-elected opposition lawmakers, including Nathan Law, the youngest person ever to be elected to the legislature. The only infraction the four ever committed was straying from their oaths during the swearing-in ceremony to voice their desire for their city to democratise.

The two news stories, less than 24 hours apart, share a chilling symmetry. They underscore the Chinese government’s growing intolerance for dissent on both the mainland and the territories it controls.

Read the rest of this article on TheGuardian.com.

As the article appeared in The Guardian

As the article appeared in The Guardian

Liu lived and died a hero

Liu lived and died a heroThen on Friday afternoon, Beijing’s long arm stretched across the border and reached into Hong Kong’s courtroom. Bound by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee’s decision on oath-taking etiquettes, the Hong Kong High Court ruled to unseat four democratically-elected opposition lawmakers, including Nathan Law, the youngest person ever to be elected to the legislature. The only infraction the four ever committed was straying from their oaths during the swearing-in ceremony to voice their desire for their city to democratise.

The two news stories, less than 24 hours apart, share a chilling symmetry. They underscore the Chinese government’s growing intolerance for dissent on both the mainland and the territories it controls.

Read the rest of this article on TheGuardian.com.

As the article appeared in The Guardian

As the article appeared in The Guardian

Published on July 17, 2017 09:42

July 9, 2017

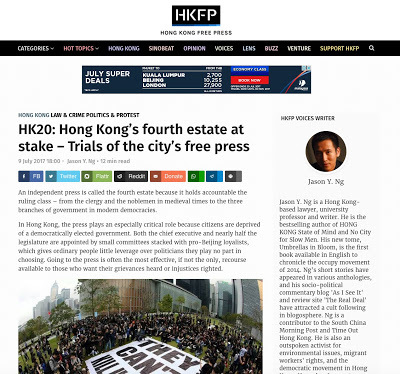

Trials of the Fourth Estate–Special Double Issue 第四權之考驗-特別雙刊

An independent press is called the fourth estate because it holds accountable the ruling class—from the clergy and the noblemen in medieval times to the three branches of government in modern democracies.

In Hong Kong, the press plays an especially critical role because citizens are deprived of a democratically elected government. Both the chief executive and nearly half the legislature are appointed by small committees stacked with pro-Beijing loyalists, which gives ordinary people little leverage over politicians they play no part in choosing. Going to the press is often the most effective, if not the only, recourse available to those who want their grievances heard or injustices righted,

Article 27 of the Basic Law protects freedom of the press, as does the Bill of Rights Ordinance which guarantees broad rights to “impart information and ideas.” While the letter of the law is clear, the reality in which journalists operate tells a different story.

Since the handover, Hong Kong’s ranking on the World Press Freedom Index has been in freefall, slipping from 18th in 2002 to 73rd in 2017 and lagging behind countries such as Haiti, Bosnia and El Salvador.

Has the city’s free press become the first casualty in the “one country, two systems” experiment?

Last papers standing

Last papers standing

Overt suppression

In Hong Kong, direct encroachment on press freedom can take many forms. The Apple Daily, the only broadsheet newspaper that remains openly critical of Beijing, bears the brunt of the onslaught.

During and since the Umbrella Movement, the paper has come under repeated cyber-attacks, its parent company Next Media has had its headquarters firebombed, and its outspoken founder Jimmy Lai (黎智英) has been harassed.

But Apple Daily is hardly alone and its woes are merely the tip of the iceberg.

First, there is outright censorship. Since 2015, online-only news media outlets such as Hong Kong Free Press, Initium (端傳媒) and Stand News (立場新聞) have been barred from attending government press conferences. Just last week, the government’s Information Services Department extended the ban to official events related to the 20th anniversary of the handover.

“Online media make bureaucrats nervous because they are hard to control,” says Lau Sai-leung (劉細良), a former government information coordinator and co-founder of House News(主場新聞), the predecessor of Stand News.

Lai Sai-leung, Stand News columnist

Lai Sai-leung, Stand News columnist

“Unlike most traditional print media outlets which are owned by big businesses, online outlets are independently owned.” Lau tells me. “They are targeted because they aren’t part of the unholy alliance between the government and the establishment.”

Defamation suits are another effective tool to silence the independent press. On at least three occasions between 2013 and 2016, chief executive C.Y. Leung threatened litigation against Hong Kong Economic Journal (HKEJ 信報) and Apple Daily for reporting his alleged ties with Triads, abuse of power and undeclared business dealings.

“Leung’s threats bear the hallmarks of the intimidation tactics in Singapore, where senior government officials are known to use legal action to inhibit dissent,” William Nee, a Hong Kong-based researcher at Amnesty International, tells me.

William Nee, researcher at Amnesty International

William Nee, researcher at Amnesty International

If all things fail, however, adversaries resort to the blunt instrument of physical violence. The Hong Kong Journalists Association documented a significant surge in the number of cases of attacks on frontline reporters during and since the Umbrella Movement by pro-Beijing groups and, in some instances, law enforcement.

Among the long list of documented physical assaults committed against journalists, the most egregious one occurred in 2014 when Kevin Lau Chun-to (劉進圖), the former editor-in-chief of Ming Pao(明報), was stabbed six times in broad daylightoutside a restaurant. The news sent shock waves across the media industry and remains one of the most frequently cited incidents of violence against journalists in the region.

Lau and his colleagues spent weeks after the attack sifting through hundreds of news reports he had worked on, trying to identify individuals or organizations he might have upset. It was a sobering exercise for him and his staff.