Seeing Joshua 探之鋒

“We are here to visit a friend,” I said to the guard at the entrance.

Tiffany, Joshua Wong Chi-fung’s long-time girlfriend, trailed behind me. It was our first time visiting Joshua at Pik Uk Correctional Institution and neither of us quite knew what to expect.

Joshua Wong, behind bars

Joshua Wong, behind bars

“Has your friend been convicted?” asked the guard. We nodded in unison. There are different visiting hours and rules for suspects and convicts. Each month, convicts may receive up to two half-hour visits from friends and family, plus two additional visits from immediate family upon request.

The guard pointed to the left and told us to register at the reception office. “I saw your taxi pass by earlier,” he said while eyeing a pair of camera-wielding paparazzi on the prowl. “Next time you can tell the driver to pull up here to spare you the walk.”

At the reception counter, Officer Wong took our identity cards and checked them against the “List.” Each inmate is allowed to grant visitation rights to no more than 10 friends and family members—anyone not on the List will be turned away. Tiff was confidant that both of our names had been added; she had triple-checked that with Joshua’s attorney ahead of time.

“Miss, you’re okay. But the second visitor, Mr. Ng, your name doesn’t quite match our record. The inmate submitted a slightly different Chinese surname,” said Officer Wong. I knew about Joshua’s dyslexic tendencies.

“But don’t worry,” the officer assured, “I can fix that for you if you would just give me a minute.”

I thanked him and asked if I could bring pen and paper with me.

“Sorry, but no phone, no notebook, no nothing—you can’t bring anything in other than your ID card. Rules are rules.”

Pik Uk Prison in Sai Kong

Pik Uk Prison in Sai Kong

Tiff and I exited the reception office and headed straight to the main building, almost sprinting to evade the two relentless paparazzi. Once inside, we deposited our belongings in a locker and walked through an X-ray gantry much like the ones at the airport. Tiff held on to a bag of personal supplies for Joshua.

Visitors are permitted to bring basic items for inmates, but they must meet stringent prison requirements. Tiff knew the only way to guarantee compliance was to purchase everything—from notebooks to batteries and undergarment—at the general store near Lai Chi Kok Reception Centre, where Joshua and the other two convicted student activists, Nathan Law Kwun-chung and Alex Chow Yong-kang, spent their first night after their sentencing.

We were told to take a seat and wait for our number to be called. There were a half-dozen other visitors in the waiting room. Tiff and I entertained ourselves by watching the news on the overhead television set. Paul Lam, Chairman of the Hong Kong Bar Association, was telling reporters that the jailing of Joshua and other activists was not politically motivated. Tiff rolled her eyes and focused on something else.

15 minutes later, an officer called out several numbers including ours. Everyone in the waiting room got up and walked in a single file towards the narrow visiting area. Tiff and I located Joshua’s booth and there he was: the same scrawny boy with a different haircut. He flashed a Cheshire cat smile, clearly elated to see his girlfriend. In an instant, I went from second visitor to third wheel.

Tiff picked up the handset and started to chirp. I saw Joshua’s lips move but couldn’t hear him. The thick glass walls separating prisoners from visitors were certifiably soundproof. What did come through, however, was his good spirits—none of the prison weariness had rubbed off on him.

Tiff spoke in rapid-fire spurts, updating Joshua on personal and political matters with determined efficiency. She also referred to the notes scribbled on her palms. Joshua alternately nodded and spoke, all the while smiling like a kid seeing snowflakes for the first time. If it weren’t for his brown prison clothes, I wouldn’t have guessed that he was serving a six-month sentence.

While they talked, a smiling prison guard saw me standing behind Tiff and walked over to offer me a chair. I declined but thanked him profusely.

As seen on TV

As seen on TV

“Your turn,” Tiff said, handing me the handset after some 10 minutes. Mindful that every second I took would be one fewer for the two of them, I rushed through what I needed to discuss with Joshua. I also told him about Typhoon Hato and Chris Patten’s article in The Financial Times condemning his imprisonment. He nodded—I suspected he already knew all that from watching the news on TV.

I was most concerned about Joshua’s living conditions and bombarded him with questions. He told me the juvenile ward was surprisingly airy, and that most nights he could barely feel the summer heat. “I even need a thin blanket at night,” he said. “It’s much better than sleeping on concrete during Occupy.”

The food is nothing to write home about: plain rice, chicken wings and steamed vegetables. He shares a tiny cell with another minor inmate, who was convicted for illegal drug use—as most juvenile delinquents at Pik Uk were.

I asked him about any abuse, and he assured me there had been none whatsoever. He had just completed a seven-day “orientation” and a new routine would begin next week. He was expected to begin language and maths classes with other young inmates. He worried somewhat about the physical training—jogging and marching—as he isn’t the athletic type and doesn’t answer well to strict commands.

I asked him what the hardest part was about being behind bars. “Passing the time,” he sighed. “Time crawls in here. Every day I rack my brain to keep myself occupied.” He had nearly finished the six books that visitors are allowed to bring him each month.

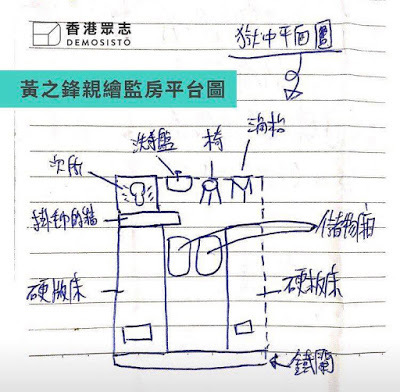

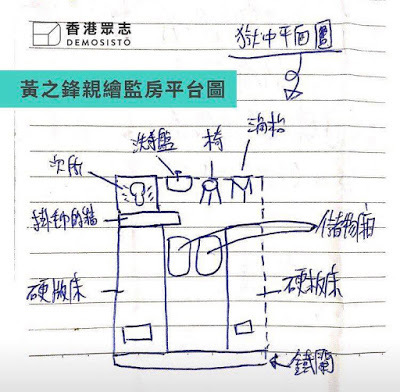

Joshua's cell, drawn by him

Joshua's cell, drawn by him

I wanted to know if he had a message for his supporters.

“Please tell everyone I’m doing fine and not to worry about me. Instead, ask them to help Demosisto in any way they can,” he said, referring to his pro-democracy political party.

“The majority of our core members are, or will soon be, in jail,” he added, shaking his head in frustration. “We need to keep our party running and get ready for the upcoming by-election to fill Nathan’s Legco seat.” Weeks before Demosisto’s chairman Nathan Law Kwun-chung went to prison, he was striped of his lawmaker title for straying from the prescribed oath when he was sworn in.

“Among all the opposition parties in Hong Kong, we have come under the heaviest attack. But we won’t give up.” There was indignation and defiance in his voice.

The rest of the 30 minutes went by quickly. We knew time was up when several uniformed officers suddenly appeared to escort the inmates back to their cells. Joshua got up and waved goodbye, training his eyes on Tiff and still smiling from ear to ear. It was sweet and heartbreaking at once.

On our way back to town, I replayed the visit in my head. All things considered, Joshua has adjusted well to the new environment. As much as he struggles to pass the time, his timetable will fill up once his habit of journal keeping and letter writing takes hold and he gets his radio and newspaper subscription.

What’s more, based on my limited interaction with the staff, everyone in the juvenile ward seemed to be courteous and helpful. Nothing suggested Joshua was being treated with anything but respect and professionalism. That’s a marked departure from the many horror stories about youth incarceration I’ve read in the local press. Perhaps his fame had afforded him some protection.

All that may change after Joshua turns 21 in October, when he will be transferred to the adult ward. There, he will be required to work every day—be it carpentry, laundry, kitchen duties or repairs and maintenance—to earn his keep. And he will have to adapt to a new routine all over again.

____________________________________

A shorter version of this article appeared on SCMP.com under the title "Behind bars, Hong Kong political activist Joshua Wong remains in good spirits."

As posted on SCMP.com

As posted on SCMP.com

Tiffany, Joshua Wong Chi-fung’s long-time girlfriend, trailed behind me. It was our first time visiting Joshua at Pik Uk Correctional Institution and neither of us quite knew what to expect.

Joshua Wong, behind bars

Joshua Wong, behind bars“Has your friend been convicted?” asked the guard. We nodded in unison. There are different visiting hours and rules for suspects and convicts. Each month, convicts may receive up to two half-hour visits from friends and family, plus two additional visits from immediate family upon request.

The guard pointed to the left and told us to register at the reception office. “I saw your taxi pass by earlier,” he said while eyeing a pair of camera-wielding paparazzi on the prowl. “Next time you can tell the driver to pull up here to spare you the walk.”

At the reception counter, Officer Wong took our identity cards and checked them against the “List.” Each inmate is allowed to grant visitation rights to no more than 10 friends and family members—anyone not on the List will be turned away. Tiff was confidant that both of our names had been added; she had triple-checked that with Joshua’s attorney ahead of time.

“Miss, you’re okay. But the second visitor, Mr. Ng, your name doesn’t quite match our record. The inmate submitted a slightly different Chinese surname,” said Officer Wong. I knew about Joshua’s dyslexic tendencies.

“But don’t worry,” the officer assured, “I can fix that for you if you would just give me a minute.”

I thanked him and asked if I could bring pen and paper with me.

“Sorry, but no phone, no notebook, no nothing—you can’t bring anything in other than your ID card. Rules are rules.”

Pik Uk Prison in Sai Kong

Pik Uk Prison in Sai KongTiff and I exited the reception office and headed straight to the main building, almost sprinting to evade the two relentless paparazzi. Once inside, we deposited our belongings in a locker and walked through an X-ray gantry much like the ones at the airport. Tiff held on to a bag of personal supplies for Joshua.

Visitors are permitted to bring basic items for inmates, but they must meet stringent prison requirements. Tiff knew the only way to guarantee compliance was to purchase everything—from notebooks to batteries and undergarment—at the general store near Lai Chi Kok Reception Centre, where Joshua and the other two convicted student activists, Nathan Law Kwun-chung and Alex Chow Yong-kang, spent their first night after their sentencing.

We were told to take a seat and wait for our number to be called. There were a half-dozen other visitors in the waiting room. Tiff and I entertained ourselves by watching the news on the overhead television set. Paul Lam, Chairman of the Hong Kong Bar Association, was telling reporters that the jailing of Joshua and other activists was not politically motivated. Tiff rolled her eyes and focused on something else.

15 minutes later, an officer called out several numbers including ours. Everyone in the waiting room got up and walked in a single file towards the narrow visiting area. Tiff and I located Joshua’s booth and there he was: the same scrawny boy with a different haircut. He flashed a Cheshire cat smile, clearly elated to see his girlfriend. In an instant, I went from second visitor to third wheel.

Tiff picked up the handset and started to chirp. I saw Joshua’s lips move but couldn’t hear him. The thick glass walls separating prisoners from visitors were certifiably soundproof. What did come through, however, was his good spirits—none of the prison weariness had rubbed off on him.

Tiff spoke in rapid-fire spurts, updating Joshua on personal and political matters with determined efficiency. She also referred to the notes scribbled on her palms. Joshua alternately nodded and spoke, all the while smiling like a kid seeing snowflakes for the first time. If it weren’t for his brown prison clothes, I wouldn’t have guessed that he was serving a six-month sentence.

While they talked, a smiling prison guard saw me standing behind Tiff and walked over to offer me a chair. I declined but thanked him profusely.

As seen on TV

As seen on TV“Your turn,” Tiff said, handing me the handset after some 10 minutes. Mindful that every second I took would be one fewer for the two of them, I rushed through what I needed to discuss with Joshua. I also told him about Typhoon Hato and Chris Patten’s article in The Financial Times condemning his imprisonment. He nodded—I suspected he already knew all that from watching the news on TV.

I was most concerned about Joshua’s living conditions and bombarded him with questions. He told me the juvenile ward was surprisingly airy, and that most nights he could barely feel the summer heat. “I even need a thin blanket at night,” he said. “It’s much better than sleeping on concrete during Occupy.”

The food is nothing to write home about: plain rice, chicken wings and steamed vegetables. He shares a tiny cell with another minor inmate, who was convicted for illegal drug use—as most juvenile delinquents at Pik Uk were.

I asked him about any abuse, and he assured me there had been none whatsoever. He had just completed a seven-day “orientation” and a new routine would begin next week. He was expected to begin language and maths classes with other young inmates. He worried somewhat about the physical training—jogging and marching—as he isn’t the athletic type and doesn’t answer well to strict commands.

I asked him what the hardest part was about being behind bars. “Passing the time,” he sighed. “Time crawls in here. Every day I rack my brain to keep myself occupied.” He had nearly finished the six books that visitors are allowed to bring him each month.

Joshua's cell, drawn by him

Joshua's cell, drawn by himI wanted to know if he had a message for his supporters.

“Please tell everyone I’m doing fine and not to worry about me. Instead, ask them to help Demosisto in any way they can,” he said, referring to his pro-democracy political party.

“The majority of our core members are, or will soon be, in jail,” he added, shaking his head in frustration. “We need to keep our party running and get ready for the upcoming by-election to fill Nathan’s Legco seat.” Weeks before Demosisto’s chairman Nathan Law Kwun-chung went to prison, he was striped of his lawmaker title for straying from the prescribed oath when he was sworn in.

“Among all the opposition parties in Hong Kong, we have come under the heaviest attack. But we won’t give up.” There was indignation and defiance in his voice.

The rest of the 30 minutes went by quickly. We knew time was up when several uniformed officers suddenly appeared to escort the inmates back to their cells. Joshua got up and waved goodbye, training his eyes on Tiff and still smiling from ear to ear. It was sweet and heartbreaking at once.

On our way back to town, I replayed the visit in my head. All things considered, Joshua has adjusted well to the new environment. As much as he struggles to pass the time, his timetable will fill up once his habit of journal keeping and letter writing takes hold and he gets his radio and newspaper subscription.

What’s more, based on my limited interaction with the staff, everyone in the juvenile ward seemed to be courteous and helpful. Nothing suggested Joshua was being treated with anything but respect and professionalism. That’s a marked departure from the many horror stories about youth incarceration I’ve read in the local press. Perhaps his fame had afforded him some protection.

All that may change after Joshua turns 21 in October, when he will be transferred to the adult ward. There, he will be required to work every day—be it carpentry, laundry, kitchen duties or repairs and maintenance—to earn his keep. And he will have to adapt to a new routine all over again.

____________________________________

A shorter version of this article appeared on SCMP.com under the title "Behind bars, Hong Kong political activist Joshua Wong remains in good spirits."

As posted on SCMP.com

As posted on SCMP.com

Published on August 28, 2017 03:38

No comments have been added yet.