Mike Reuther's Blog

March 10, 2024

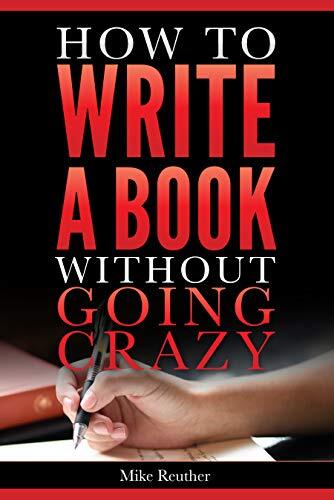

Want to write a book?

A book that will will ignite the author within you.

Many people dream of writing the book of their dreams but simply can’t

make it happen or even get started. This book by longtime author and

freelance writer Mike Reuther shows the key to tapping creativity and

giving birth to a book.

You’ll learn how to:

Find ideasTap your creativityFind your flow and rhythmWrite fast

February 28, 2023

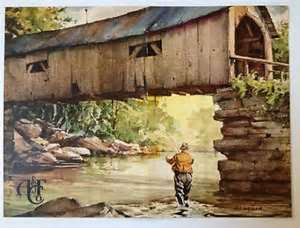

Another fly-fishing book

A Fly-Fishing Story is an odyssey, a road adventure, and one man’s personal quest that brings the outdoors alive.

November 17, 2022

Just Write

The trick is not becoming a writer. The trick is staying a writer.

Those words from the late great author Harlan Ellison so aptly sum up what it is to be an author.

Anyone can decide they want to write books, screenplays, the Great American Novel.

The problem is staying the course.

Writing, you see, is not among the lucrative professions out there. Oh. Did I call it a profession?

A profession, at least to me, means a career. You know, one of those jobs you show up for at some office – five, six, even seven days a week – that pay well and provide a decent living.

You see, that’s the crux of the matter. Writers, for the most part folks, don’t make a lot of money. In a world that, let’s face it, revolves so much around chasing the almighty dollar, it can come down to those…

View original post 258 more words

November 1, 2022

It’s NaNoWriMo

Follow the yellow brick road.

The words from the celebrated movie, “The Wizard of Oz” pretty much say it all for those willing to take a leap of faith.

For authors unsure about writing that first book, following the yellow brick road means making that first step and continuing with and completing the journey to that land of Oz.

What better way to start than today – Nov. 1, the official kick-off to NaNoWriMo.

For those of you not familiar with this rather odd term, it stands for National Novel Writing Month, a time to let the words flow.

The annual event was started in 1999 by Chris Baty to get wannabe writers started on writing a book.

Have you always wanted to write a book? Are you dying to get words onto that computer screen or piece of paper?

Have you always dreamed of being an author? Now is the time to make that dream come alive.

With NaNoWriMo, you write a 50,000-word novel in a month’s time.

But you don’t have to participate in the official event to start pounding that keyboard and creating that book of your dreams.

You can make it happen on your own.

Today is as good a time as any.

What have you got to lose?

Mike Reuther is a novelist and the author of books on writing. Check out his Amazon page at https://www.amazon.com/Mike-Reuther/e/B009M5GVUW

November 28, 2021

The Dying Light – VI

Mom and I continued with the business. The drought years were soon replaced by some wet years. The streams ran full of water and trout, and the flocks of fishermen returned. My old man did not return.

I met a woman too. She came into the store one April day just before the beginning of trout season to buy some flies. With long flowing dirty-blonde hair, an easy manner, and a smile that lit up a room, I was smitten almost immediately. Gail had just moved back to the area to start up her own fly-fishing guide service. Like me, she had been disillusioned with a job and was looking to start fresh in what she liked to call “trout country.”

Up till this point, I had kept out of relationships. I guess I didn’t want to end up like my parents.

“Where have you been all my life?” I said.

We had just made love on a moonlit night along the banks of Miller’s Creek. By now, we were many months into the relationship, and I was seriously thinking of asking Gail to marry me.

“When someone says something as cliché as that, it must mean he’s ready to tie the knot.”

“Well … what do you think?” I said.

“Of what?”

She nudged me with her foot.

“You know what? Let’s just do it.”

“Well …”

“C’mon Mr. Impulsive,” she said, giving me a harder nudge with her foot. “We’ll just do it. A quickie elopement in Maryland. No fuss. No big ceremony.”

And so, we did.

The evening of the day of the elopement, I called first mom and later my old man to give them the news.

Mom couldn’t have been happier. From the time she met Gail, my mom liked her. She felt it was about time I met someone to spend the rest of my life with.

My old man was a different story.

Marriages, he said, are tricky deals.

“Hell. Look at your mother and me.”

“Dad. I know you have another family, another wife.”

Just like that, I’d blurted it out.

He didn’t respond. I heard muffled noises, like the crumpling of paper, in my phone.

“Look. Your mother was never easy to live with. And your grandmother … I mean hell Billy … the two of them.”

“What are you saying dad?”

“Nothing.”

“Look,” he said. “You could have invited me to the ceremony.”

“It was an elopement dad. We didn’t invite anyone.”

“What … a shotgun marriage?”

That caused us both to laugh.

“So, who is this woman?” he said.

“Just someone I met and now love and plan to stay with …”

“For the rest of your life?”

“That’s the plan.”

“Must be one hell of a girl.”

“She is.”

“I’d like to meet her.”

“Sure. We’ll go fishing.”

“Fishing?”

“Sure. She fishes. As a matter of fact, she’s one hell of an angler. Fishes rings around me.”

“That isn’t saying much son. You’re fishing skills always left a bit to be desired.”

I should have let it go, but I couldn’t. Anger had suddenly overcome me. Too often, I had allowed this man to do and say what he wanted. And he had given me such an opening. I couldn’t help myself.

“It might have helped if you were around half the time to teach me some of your fishing strategies, some of your secret tactics. Then again, I guess I did learn some of your secrets.”

“What can I say son … I’m sorry.”

“You’re sorry? You’re sorry? That’s it?”

“What do you want me to say?”

“I don’t know dad. I don’t know.”

It would be a few years after that phone call with my old man before I would again see him. As usual, he turned up unexpectedly, this time not at my mom’s, but my house on a mid-May day.

In those years since my old man had bailed out on us at the store, my mom had tried without success to get a divorce from him. But for whatever reason, my old man didn’t want one.

But as the years went by and she failed to secure a divorce, she resigned herself to remaining, as she put it, “a happily married woman.”

“Happily married mom?” I said.

“Sure. Happily married as long as that bigamist is out of my life.”

He was old when he returned. The cocksure man with the salesman’s glib tongue was mostly a memory. It was kind of sad really. He walked slowly now and talked slowly. When he appeared at our front door, I hardly recognized the stooped figure. There he was, in an old floppy fishing hat, tattered vest, holding a fly rod, the stub of a cigar clenched between his teeth.

“Are we going to go fishing or what?” They were the first words out of his mouth.

“Fishing?”

“Sure. You and that little lady of yours. I hear she’s the real deal. A hell of an angler. I’d like to see that for myself.”

I wasn’t surprised that my old man would prove to be such a hit with my wife. Never mind that I had told her everything about him, warts and all. My old man, for all his faults, was a charmer, a hit with the ladies.

Still, she was reluctant to accompany us fishing on Miller’s Creek the next day.

“Just you two need to go. Not me. A father and son reunion.”

My dad wouldn’t hear of it.

“No sir little lady,” he said. “I heard you’re the real deal out there on the stream, and I want to see for myself.”

We ended up at our favorite hole early that evening, the spot where my old man and I had caught all the trout during the Green Drake hatch years earlier. It was here we’d built the campfire and eaten the big one I’d caught after my old man had broken into the cabin, the same night mom had informed us that Nana was dead.

“We should have come earlier,” I said. “The March Browns were on earlier in the day.”

“That’s right,” Gail said.

“Never mind the March Browns,” my old man said. He gazed up at the sky. “The dying light.”

“Best time to go fishing for trout,” I said.

Gail allowed herself a puzzled look.

I guess I expected a competition, for my old man to show us he was the best angler among us and the best damn fisherman Miller’s Creek had even seen. But age had seemed to bring concessions. He used a wading staff to creep into the shallow waters now, and there was an overall patience and deliberateness about him. And even after Gail had hooked three trout and I reeled in two, and he had yet to catch even one, he seemed unfazed, in no hurry at all to prove his angling expertise.

At one point, while preparing to cast his line, he stopped and gawked in admiration as Gail landed and brought to net a nice eighteen-inch brown trout.

“Yes sir. I guess you really are the real deal there Missy.”

“It’s Gail,” she said, managing a smile.

“Right you are. Right you are.”

The fishing began to slow down as the light faded. The buzz of cicadas filled the air, the pool before us, up till then alive with the occasional rises of trout, grew still.

My old man had not yet caught a trout.

“What do you think?” I asked of no one in particular.

“I think these fish have had enough of us,” Gail said.

“Bullshit,” my old man said. “This is when it gets good.” He had been sitting on a rock for the past ten minutes, spending much of that time pawing through a fly box and then fighting what appeared to be a losing battle to get a fly tied onto his leader in the fading light.

“Do you need a flashlight?”

He waved me off with a single swipe of his hand and started to rise, stumbling a bit as he got to his feet.

“I got the damn thing tied on.”

“What do you have on?”

“Green Drake. Number eight.”

“Green Drake?” I said.

“It’s too early for the Drakes,” Gail said. “They won’t be here for another week or more.”

“That shows what you know Missy.”

With his wading staff he steadied himself and made a few tentative steps into the shallow water. There was a rise of a fish on the far side of the pool, and a few moments later, another rise. My old man stared out at the dark waters of the creek. For what seemed like the longest time but was perhaps just moments, he waited.

He slowly raised his rod, then whipped it back and forth before shooting out line. I didn’t see his fly hit the water, nor follow its slow journey floating on the far side of the pool, but I heard the splash alright.

My old man yanked back his rod.

“Whoa,” Gail said. “That’s a big fish.”

“Goddamn right that’s a big fish,” he shouted, then emitting a shrill whistle.

“Don’t let him get away,” I shouted.

He didn’t.

After a ten-minute fight, my old man reeled in the biggest trout I had even seen caught from Miller’s Creek. It was a two-foot-long, deep-bellied brown trout with rounded dark speckles and a rich butter-colored underside.

“What a beautiful fish,” Gail said as we gathered around to get a close look at the fish.

“No Green Drakes huh?” my old man said. He gave Gail a wise-ass grin.

“What can I say?” she said.

He looked at me. “Let’s eat the son-of-a-bitch,” he said.

“Okay,” I said. “We’ll have trout for lunch tomorrow at our place.”

He shook his head. “I’m talking about now.” He pointed across the creek to the cabin.

Dad. That’s private property.

“Sure,” he said. “My private property.”

“What are you talking about?”

“I made a deal on the place. It’s mine.”

Gail and I looked at each other.

“At least it will be in another month.”

We just stared at my old man. “Well c’mon,” he said. “Let’s wade across the creek and build a fire. There’s nothing like freshly caught trout cooked over flames.”

From the short story, The Dying Light by Mike Reuther. Check out his author page at https://www.amazon.com/Books-Mike-Reuther/s?rh=n%3A283155%2Cp_27%3AMike+Reuther

November 26, 2021

The Dying Light – V

Why did I go back?

I’m not sure.

It would be easy to say it was because of my life back in Houston and a job I hated. But maybe it was something else, a need to finally make things right, even if I knew, deep in my heart that it was a foolish notion.

It was October, that splendid time in northcentral Pennsylvania when the trees drip the colors of wine and the air turns crisp and the aroma of fall—wood smoke from the cabins along Miler’s Creek, fills the air. It’s not a time of beginnings, but of settling in— for the long winter. The stream-bred trout of Miller’s Creek enter the spawning season as the chill sets in, a time to begin reflecting on the sins and bad decisions of the passing year.

My old man had done what he said he might do: He had purchased Stone General Store.

My return home did not become a reality without its share of long and hard consideration. There were more than a few long-distance phone calls, some with my old man, others with my mother.

“We can make this work,” my old man said more than once.

“Make what work dad?” I asked. “Make what work?”

I found a place to live, a small one-room cabin, a few miles from my boyhood home.

My old man found his own place as well. He had given up his sales job and living part-time elsewhere.

“Does this make us a family?” I asked my old man.

I had just locked the front door to the store and watched the last of the customers, a hunter in camouflage clothing and a red vest, drive out of the parking lot after filling his pickup with gas. The two of us were all alone in the store. It was the end of the day around dusk, the opening of small game season, and it had been a particularly busy day for us.

My old man gave me a funny look.

“I don’t know what the hell you mean?” he said.

“C’mon. You and me and mom. The three of us … owners and operators of this store.”

He hit the light switch and the back of the store where the fly shop was located went black before he moved past me. “It just makes us business partners,” he said. I watched him disappear out the side entrance door. I heard his car start up and drive off up the two-lane road.

Those first years owning and operating the store were good ones. The change in ownership did not chase off any of the old customers. We were busy most days, although winter brought a lull to the business, as we expected it would.

The start of fishing season in April brought the customers flooding back, and summer meant tourists and travelers and bikers flocking to the store as well.

We had expanded the small delicatessen to include ice cream. It seemed like a small enough addition, but it certainly meant a boost to our fortunes, especially on the days when families toting kids had no other reason to come into the place.

My old man took care of the fly fishermen who came in for flies and other angling needs. He relished this part of the business, and I suspect it was the principal reason he decided to be part of the operation. He loved nothing better than to point fisherman to the right flies to use and jaw with them about the fishing conditions on Miler’s Creek and some of the feeder streams in the valley.

My old man had a way with people, honed no doubt from his years as a salesman. Laughter and lusty jokes often filled the fly shop area of the store.

Mom worked the deli along with a few locals, a couple of young women, making sandwiches and checking out the fishing accessories or other knick-knacks and items customers picked up at the store.

I kept the books, ordered supplies, maintained inventory, and assisted with different things both in the fly shop and the deli.

I think the store gave us all a sense of purpose if nothing else, even if the work left me tired and weary many days. Still, it was nice to see the store turning a profit, if a slim one.

It was the 1990s. The movie, A River Runs Through it, about a father and his two boys connected by fly fishing in the wilds of Montana, had captured the fancy of the nation, and many people were taking up the sport for the first time, and our store seemed to be catching the wave of its popularity.

But then came the drought years, when Miller’s Creek and other streams throughout the valley ran low. Trout turned belly-up in sections of creeks by mid-summer two straight years. Fishing served such a large part of the store’s income, and dry seasons proved to be disastrous for our business.

A deep sense of first frustration and later helplessness set in.

“We just have to be patient,” my mom said. “It will all come back. Mother Nature has a way of balancing things out.”

My old man suggested we cut our losses and sell. He saw little reason for continuing with what he saw as a losing proposition. Increasingly, he had stayed away from the store. The store’s daily operations unconnected to fishing mostly bored my old man anyway, and with fewer anglers coming in, he had grown restless.

“What do you suppose he does with himself when he’s not here?” I asked my mom.

I was in the deli sweeping the wooden floor. It was the end of another slow day at the store.

My mom frowned. “Maybe looking for a job or hanging out in upstate New York.”

“You mean in Rochester? But I thought that was all over.”

“Over?” My mom shot me a look of utter disbelief.

“You don’t know the whole story? Do you?”

She sprayed some disinfectant on an area of the food counter before wiping it with a cloth.

“The whole story?”

We were the only two in the place. A pickup truck shot past the store along the two-lane road.

“Your father has another family.”

“What?”

“Yes. Up in Rochester. He’s got a wife, two grown sons.”

“Two grown sons.”

There came a ringing in my ears. For a moment, the room seemed to sway.

“What? You mean …”

“I mean he has two families. Us and them.”

My mom stood there with hands on her hips, staring at me, expressionless. My mind began to reel. The long absences over the years. The tension and fights between my old man and my mom. Sure. It all made sense.

“The diary?” I said, choking back the words.

My mom nodded.

“Nana knew and you didn’t?”

Her eyes grew moist. “Don’t ask me how she knew, but she did.”

“Why didn’t you tell me before?” I asked.

“Oh honey. Would it have mattered?”

“I guess not,” I said.

There was nothing more to say.

He’s pulling out. Taking his share of the store. It will just be you and me.”

“Fine,” I said. “That’s just fine with me.”

From the book, The Dying Light by Mike Reuther. https://www.amazon.com/-/es/Mike-Reuther-ebook/dp/B0989DDHGZ

November 24, 2021

The Dying Light – IV

Dad stayed around for the funeral and the graveside service a few days later.

He was right there next to me and mom in the little country church when the minister, a skinny man known as Pastor Ed, gave the eulogy and later the send-off for Nana in the graveyard behind the church before her casket was lowered into the ground.

It seemed, in many ways, like old times. My old man and my mom and me together again. Of course, I knew this was a special time, a family event.

Unlike the old days, they didn’t sleep together back at the house. My old man spent his nights in Nana’s room. Something seemed different between my old man and mom. The years, perhaps Nana’s death, had changed things somehow.

Gone was the bickering, the accusations, even some of the tension that permeated that house when my old man was around.

“I know you never liked Nana,” mom said. “You didn’t have to stick around for all this.”

The three of us were on the porch, remarkably enough, recalling some of the old times with Nana: The strawberry shortcake she liked to bake, her feisty personality.

“I have to give that old bitch credit. She never took any shit from anyone,” my old man said.

“Please Frank. She was my mother. Don’t call her a bitch. But you’re right. She didn’t take crap from anyone, including you.”

My old man shot my mom an evil grin. “Well now, I’m not gonna deny that. The old girl had some piss and vinegar alright.”

It grew quiet. A robin sitting in a willow tree at the far end of the property flew from a branch toward the porch. It fluttered before us and swiveled, letting out a cawing noise before disappearing. Every year, robins built a bird nest on the porch beneath the spouting, and the robin was apparently checking on her young, letting us know we were intruders. Off in the distance, a faint rumble of thunder rocked the sky.

“Hank Stone’s store is for sale,” my old man said. He turned and looked at my mom.

“I could have told you that,” she said, staring off toward Miller’s Creek.

“Really?” I said. For this was truly news to me. Stone General Store was a landmark in the valley. Gasoline, groceries, a delicatessen, and of course, bait and tackle and those locally hand-tied flies.

“I’m making an offer.”

My mother laughed, as if choking, put a hand to her chest, glanced at my old man, before throwing back her head to surrender to an uncontrollable burst of giggling. I had never witnessed my mother laughing so hard, so uncontrollably. It was the one time I can remember my old man appearing something akin to embarrassment.

“What the hell’s so funny Marie?” he said.

“C’mon Frank. You don’t have two nickels to rub together.”

My old man glared at her. “Okay, he said. “You’re partly right. I don’t have a whole lot of money. A lot of what I earn I send to you, but I got enough for a small down payment and with a couple of partners, I could have that store by the fall. We’ll see who’s laughing when the deer hunters are flooding the store on their way back and forth to their camps and I’m happy taking their money.

“Oh, really now,” mom said, fighting a smile. “You’ve looked into this?”

My old man nodded.

“And you have partners?”

Her eyebrows raised, her head cocked, my mom waited for him to respond.

Lightning lit up the sky. Thunder followed. The storm was drawing closer.

“Well … there’s junior here, and you.”

My mom appeared stunned.

“My God Frank. Have you lost your mind?

“I don’t think so.”

“You have. You’ve lost your mind.”

“Dad. Really? You’re serious about this?”

My old man crossed his arms. He looked like a petulant child. “I’ve never been more serious about anything in my life.”

My mom shot up from the porch swing. “This is just too much,” she said. She threw open the porch screen door and disappeared into the kitchen.

“I’m not kidding about this Billy. That store … it’s a gold mine.”

It was a gold mine, the only store for miles around where people could fill their gas tanks and stock up on groceries, household supplies, and fishing equipment.

“It takes work to run a store dad.”

“Don’t you think I know that junior?”

“I think you know a lot of things dad … but sometimes …”

“What?”

“You’re kind of impulsive.”

“So … what? You don’t want to be a partner?”

“Jesus dad. I didn’t say that.”

“This is a chance.”

“A chance?”

“Our chance. Don’t you see. To be a family. All of us … in this together.”

I wanted to tell my old man a lot of things at that moment. How that ship had sailed. I wanted to ask him where he’d been twenty years ago, when a ten-year-old kid really needed him, and how he couldn’t just suddenly make things better through the years by taking his son fishing during the great mayfly hatches on Miller’s Creek.

“Your mother tells me you hate your job and hate Houston. Hell son … you could come home. Be a businessman.”

“Jesus dad. Jesus.”

A loud burst of thunder rocked the sky and the screen door whined open. My mom held a small brown book in her hands. In almost ceremonial fashion, with an erect bearing, she slowly walked to my old man sitting beside me on the porch, and with the book still in her hands, dropped it on his lap.

“What’s this?”

My old man looked at my mom as if she’d lost her mind.

“So.” He looked kind of helplessly over at me then back at mom. I recognized the book as Nana’s diary. No one, of course, was ever allowed to read Nana’s diary. Not even mom. I knew this couldn’t be good for my old man. I’m pretty sure he sensed this too as he sat there looking kind of stupidly at this musty old book with the dull brown cover sitting in his lap.

Mom snatched it up and cast furious eyes upon my old man.

“Do you want to tell me what this is all about?” he said.

It took my mom no time at all to thumb through the pages before she stopped and held the diary open. With a look that wavered between agony and triumph, she held it open before her with two hands.

“Do you want me to read it Frank? Or do you want to read it?”

For the longest time, they locked eyes, my mother with that expression of agonized triumph. It was clear she had caught him somehow. He looked confused but trapped as well.

The porch chimes tinkled from the wind. There came another burst of thunder and it began to rain.

“Maybe Billy should read it.” She thrust the diary toward me, holding it aloft.

“Why don’t you just stop this Goddamn nonsense Marie.”

“Nonsense huh? Nonsense?” My mother screamed above the rain now rain pounding the roof, the wooden planks at the edge of the porch, and the wooden railing in front of us, spraying us with droplets and mist.

“Why don’t we go inside?” my old man said. “I’m getting wet.”

My mother raised the diary, the rain pummeling all around us with a furious torrent. I had never witnessed my mother commit an act of violence. She had never even spanked me, but I thought she might slap my old man silly with that diary.

But she didn’t hit him with that diary, that book that held some secret. With a long back-handed swipe of her arm, the diary flew from her hand and into the rain down the hill. My old man gawked at my mother as if she’d gone mad. And perhaps, she had gone a bit mad.

The sky blinked with lightning. A crash of thunder, like massive boulders smashing, shook the earth. The diary sat there in the grass, a small brown square, collecting rain. No one made any attempt to retrieve it.

First my mother, then my old man, and finally I too left the porch and went into the house. It rained all afternoon and into the night.

The next morning, brilliant sunshine filtered through the windows of the small house, and a pungent, welcome aroma of bacon and eggs drifted to my room.

When I looked out the window of my boyhood bedroom, I could see the diary still there on the ground part way down the hill.

My mother was at the stove moving around eggs in a skillet when I came into the kitchen.

“Where’s dad?” I asked.

“He left. It must have been the middle of the night.” She turned around. “How do you want your eggs? Scrambled?”

“Sure.”

We ate in silence.

After breakfast, I packed my things and prepared to leave. I had an afternoon flight to catch out of the small airport in town thirty miles away.

“I wish you could stay longer,” she said.

We were driving along the two-lane road along Miller’s Creek. Cabins dotted the streambank along the way to the main highway.

“What are you going to do?” I said.

“I’ve been thinking about that. I’ve been thinking long and hard about that.”

The big sign of Stone General Store loomed above the pine trees along the road.

“Ha. Can you believe dad? Talking about buying that place.” Several pickup trucks were parked in the gravel lot fronting the store. Two fishermen in waders and ballcaps crossed the lot toward a truck.

“It’s not the worst idea he ever came up with,” she said, glancing at the scene as she drove us past the store.

After checking in my two bags, we sat in the small airport lounge, waiting for the time of my departure. The conversation was mostly about my job and how things were going back in Texas.

“I just hope you’re happy,” she said. “Life is short you know. No sense doing what you don’t like.”

“I worked hard you know. I didn’t want to be like him.”

“You mean … like your father.”

“Who else?”

My mother looked out the big windows toward the runway where a small propeller plane was coming in for a landing.

All at once, she smiled. “No. You don’t want to be like your father.”

The announcement came for me to board my plane. Aside from a handful of other people, who began to rise from their seats and gather some belongings, I was the only other passenger taking this flight on the small commuter plane bound for Pittsburgh where I’d board another plane for Chicago and then on to Texas.

“So … what was in the diary?” I asked.

My mother sighed. She looked past me toward the boarding area. “Another time.” She brought me toward her in an embrace and kissed my cheek before gently pushing me away. “Go. You don’t want to miss your plane.”

From the short story, The Dying Light by Mike Reuther. His Amazon Author Page can be found at https://www.amazon.com/Mike%20Reuther/e/B009M5GVUW/ref=la_B009M5GVUW_pg_2?rh=n%3A283155%2Cp_82%3AB009M5GVUW&page=2&sort=author-pages-popularity-rank&ie=UTF8&qid=1512326113

November 22, 2021

The Dying Light – III

After college, I got the engineering job, but soon found I hated everything about working for an energy company in southeast Texas. Houston was a boomtown, a rude awakening of culture shock for a country boy from northcentral Pennsylvania.

It was a new, up-and-coming company, with smart, ambitious people. The main office was in downtown Houston, and it seemed everyone was content to make the long commute from any one of the affluent growing suburbs that surrounded that hot humid city.

I hated Texas. I grew to hate the idea of working for a company that drilled into the ground for oil. Weaning the country off foreign resources be damned. I dreamed of escape, of rolling rural landscapes. Often, I thought of home, of Miller’s Creek, and those wonderful stream-bred brownies that prowled the waters for mayflies.

I was just past my thirtieth birthday, feeling as if life was quickly passing me by when I got the phone call. “Can you come home?”

I knew the news was not good. My mother’s voice sounded weak, resigned.

“Nana isn’t well.”

Nana had fallen … again. This time, she had broken her hip.

It was late May, and the Green Drake Hatch was just starting on Miller’s Creek. Mom and I had just returned home from the hospital to see Nana. Remarkably, she was recovering quite well. There had been no broken hip, just a bad bruise that had left her hobbling. Still, she would need therapy and learn to use a walker.

“How do I tell Nana that it’s best she be put in a home?”

We sat on wooden rocking chairs on the porch facing Miller’s Creek down below. A gentle breeze blew the chimes dangling from a ceiling hook. The wind felt warm, a summer kind of breeze.

“I’m thinking of selling the place,” mom said. “It’s either that or move into town. I just can’t take care of an old woman out here in the country. She needs to be close to medical services.”

“But mom. You love it here.”

“Everything in life has its time,” she said, brushing away a single tear from her cheek. “Maybe it’s time to move on.”

She bit down on her lip and rocked back and forth in the chair. “I have a realtor coming out tomorrow.”

“You’re gonna sell the place?”

I looked to my right at the screen door leading into the kitchen. It whined and closed with a sharp slap when it closed. How many times as a boy had I raced across this porch and gone through that door. The wooden planks of the porch where we sat were chipped and badly in need of paint. Mom’s garden, where she always planted carrots and snapper beans, radishes, tomatoes, and some years even corn, was on the other side of the house next to the old springhouse. Nana always tended to the small spot in the garden where her big plump strawberries grew. The first batch would be just about ready to pick.

“What about your garden? You’ve always loved to garden,” I said hopefully.

“I didn’t plant one this year.”

“What?” I sprang from my chair and loped down the two steps from the porch. Sure enough, weeds and crab grass had invaded the large rectangle annually given over to her bountiful array of vegetables. A crow from the roof of the house squawked at me.

I walked back to the porch. “Geez mom,” I said.

“I’m tired Billy,” she said. “Just plain tired.”

She looked tired. In the long time since I’d been home her hair, which she grew long past her shoulders, had gone almost completely gray. The lines on her face had deepened. She was too quickly becoming an old woman.

I plopped into the rocking chair. For the longest time, the two of us sat there, next to each other, rocking gently, the porch planks creaking, the gentle spring breeze tinkling the chimes.

“Aren’t you going to go fishing tonight?”

“Fishing?” Of course, it had crossed my mind. “I don’t know. I don’t even know if I remember how anymore. It’s been so long time since I picked up a fly rod.”

“Oh honey. It’s like riding a bike. You don’t forget how to do that.”

“True,” I said.

“Isn’t this when those big bugs are out on the water? What do you call them?”

“Green Drakes. Yeah.”

She gave me a funny smile and nodded toward the far end of the porch where my fly rod was leaning in the corner.

“So that’s where it is,” I said.

“What? You thought I got rid of it?”

She got up slowly from the rocking chair. “I’ll whip up a quick supper and then you can fish.”

I looked down the hill where I spotted a single fisherman in a vest and carrying a rod disappear into the rhododendrons along the stream. Trailing behind him was a young boy, perhaps ten or eleven, carrying a little tackle box in one hand, a rod in the other. “Wait up dad,” he called out.

The sun had disappeared behind clouds after supper. A soft rumble of thunder shook the sky as I went down the hill from the house to Miller’s Creek. And then it dawned on me. Would this be the last time I fished here?

My old man said a fisherman should have a plan whenever he went fishing. What flies to use, what parts of the stream to fish.

“Sometimes the riffles are the prime holding spots for the damn trout,” he said. “Don’t forget the edges and along the banks. They don’t always sit waiting for bugs in the deep holes.”

Over the water, mayflies floated, including some Green Drakes. A spinner fall had just started in the early evening, occasional bugs dropping to the water.

At the first bend in the stream, I heard a trout rise for a fly, a soft splashy sound interrupting the quiet of the early evening. Sure enough, a ring appeared on the water’s surface underneath the branches of a pine reaching over the creek.

I felt a stir of excitement. It had been a long time since I’d fished. It was all I could do to keep my hands from shaking as I tied a Green Drake on to my leader when the trout rose once again.

I calculated the distance I needed to cast—about forty feet–from where I stood to the spot of the rise. I pulled some line from the reel and waved the rod back and forth and let loose the line. The fly fell with a smack on the surface along with the trailing leader in a heap, a clumsy cast, sure to scare the trout.

“Jesus. Didn’t I teach you how to cast a better than that?”

It was my old man. There he stood on the bank not far away, wearing that same old floppy fishing hat, a faded olive-green fishing vest, an unlit cigar clenched between his teeth. “Ten o’clock, two o’clock. Remember?”

I remembered. How could I forget? The casting motion. Bring the rod back to the ten o’clock position, then bring it forward to two o’clock for the line to go.

He reached into his vest and pulled out a fly box before poking through the selections. He looked about the air.

“There’s a few Green Drakes out,” he said. “Probably in the next half hour or so is when they’ll really start coming.”

In letters mom wrote to me, in our long-distance phone calls, she had made it clear that my old man was all but out of our lives. She’d even heard a rumor that he was “shacked up with some hussy in upstate New York.”

“Why don’t you just get a divorce?” I asked.

“Your father doesn’t want one,” she said.

“I guess he likes to show up now and then to fish Miller’s Creek.”

“Oh Billy, I don’t remember the last time he’s been home to do that.”

And now, here he was.

Another soft rumble of thunder gently shook the sky. My old man looked skyward. “Jesus, I hope it doesn’t storm. It’s been too long since I fished the Green Drake Hatch here.” He glanced my way before lighting up his stogie. He stared at the water. “Ya probably scared that fish with that horseshit cast,” he said.

“Likely so.”

“What do you say we head downstream a little ways?”

“Sounds good.”

I followed my old man along the well-worn narrow footpath next to the stream. Strange evening calls of birds filled the air as we moved past more rhododendron and brush and negotiated the occasional log blocking the path.

“Let’s try here for a while,” he said.

We were about a hundred feet or so before a swinging bridge over the creek. Just on the other side of the bridge back from the bank was a one-story cabin with a long front porch facing the creek. Near the bank was a fire pit surrounded by a few weathered Adirondack chairs.

My old man had once bragged about catching a dozen trout in just a half hour from this spot. Naturally, I had tried my luck here at different times over the years only to find much less success.

Still, it was a prime spot for holding trout. Just on the other side of the bridge was a big oval-shaped pool, one of the deepest sections of Miller’s Creek. As a kid, I had gone swimming here. By the time I was well into my teens, I reluctantly took part in a few forbidden nights of skinny dipping with some of the local kids. My first summer home from college I lost my virginity here to a girl named Lucy whose family owned one of the cabins downstream.

We made our way around the bridge and down the bank.

Several trout were rising in the slow-moving water of the pool.

My old man took a drag on his cigar and studied the water. “I’ve waited a long time for this.” He smiled and gazed at the water for a few more moments and looked at me. “It’s good to be out here again … after all these years.”

“Good to see you dad.”

“Yeah. Good to see you too junior.”

It was the best evening of fishing I ever had on Miller’s Creek. For the first time in my life I matched my old man fish for fish. After every other cast, it seemed, one of us was reeling in a trout. They were gulping our Green Drakes like hungry men from a Depression food line.

With each hookup, my old man would emit a loud shrill whistle, the same whistle he had used to summon me home as a kid.

As it grew dark, the trout continued swallowing our Green Drake offerings.

“This is almost becoming monotonous,” my old man said. With a sigh, he reeled in his line and set down his rod. He reached into one of his vest pockets and pulled out a flask. Uncapping it, he took a long pull on it before offering it to me.

I took a drink. I was barely a drinker, and the whiskey tasted bitter.

“I think I’ve had enough fishing for one night,” he said. “How about you?”

I shrugged. “Probably so.”

I handed him back the flask.

Out of the corner of my eye, I could see him staring at me as he took another drink.

“Same ol’ Billy. Take things as they come.”

I bristled at his words. I was always too laid-back, too easygoing for him. He’d wanted me to join him as a salesman instead of going off to college. It was the only way to make a living, he said. A man was on the road, not in an office, making his own rules, living by his wits and his own assertiveness.

“It’s gotten me this far,” I said.

“Yeah … yeah I guess you’re doing okay. Financially anyway. Your mother says you don’t like your job.”

He was still studying me as we stood there next to the creek, waiting for some response.

“It’s got its ups and downs.”

Without looking at him, I raised the rod up and made another cast. In the waning light I could barely see my fly floating on the surface.

I jerked back the rod a split second after the splash. The weight on the line was unmistakable. I could feel the fish plunge for the depths. I held the rod high as he leaped four feet from the water.

“Hell junior.”

The trout tried desperately to shake the fly and then he was zigzagging in the water. I let him run before bringing in line. The fish made another run and one more heroic leap before tiring. The line was tight as I brought him toward me.

The trout turned out to be the biggest fish either of us caught that evening—more than twenty inches long with a thick girth.

The two of us went to our knees to study my trophy, one of the mammoth stream-bred brownies of Miller’s Creek.

“I say we keep this lunker,” my old man said. “He’s a meal.”

“Mom can pan fry him in cornmeal,” I said.

“I got a better idea,” he said. He was looking across the creek at the cabin.

I didn’t know what he was talking about, but I didn’t like the gleam in his eyes.

“Yeah. I guess I can throw him back. I don’t like to eat trout that much anyway.”

“That’s because you haven’t had ‘em cooked over a fire streamside.” He was still staring across the creek toward the cabin.

“C’mon,” he said. “Let’s cross.”

“Dad. That’s not our property.”

The no trespassing signs were posted on trees on the other side of the creek.

He was already several steps into the water and looking back over his shoulder at me. “Are you coming or what?”

“Jesus dad. Would you grow up?”

“C’mon junior. We don’t have all night.”

I watched him slosh through the shallow, far end of the pool and climb up the bank on the opposite side.

He was already gathering some twigs for the fire when I cursed to myself and crossed the creek with the dying trout cradled in my arms.

In no time at all, my old man had a nice twig fire going in that fire pit.

“What if the people who own this cabin suddenly show up,” I said nervously. “I mean … we’re trespassing you know.”

“Fuck ‘em. Besides, that isn’t likely to happen.”

“So. You know the people who own it?” I peered through the darkness at the cabin. It was a rustic old place, for sure, not much more than a hut really. Firewood was stacked on the porch. I was relieved no vehicles were parked in the dirt driveway next to the cabin.

“Bill Hunley owned it years ago, but hell … he’s been dead a long time. I don’t know who has it anymore.”

He was huddled over the small fire, building a little wall of rocks around the flames. All at once, he stood up and admired his work. “Now. Let’s get that fish cleaned and have ourselves a trout supper.”

I stared at him.

“You want me to clean the damn fish,” he said.

“Have at it.”

“Where is it?”

“Soaking in the stream.”

“Well go get it.”

He was making me feel like his little boy all over again, carrying out his orders. At work, back in Texas, a supervisor often made me feel the same way.

“I’ll grab some of that firewood,” he said, looking toward the cabin. “We’ll cook that fish and have ourselves a real fire.”

I watched my old man deftly slice the trout’s belly with a knife and scrub out the entrails before cutting off the head and the tail.

“You really plan to eat this fish?”

He smiled and poked at the flames. He looked back at the cabin. “I’ll bet there are some plates and utensils in there. Hell. Maybe even a nice frying pan.”

“Dad. No.”

And then, he was walking toward the cabin and up the porch steps.

“That’s your father,” Nana said more than once. “Does what he wants and when he wants. Got no check on his desires and appetites.”

This had come right after my old man had found himself in a bad spot with the law. The details were fuzzy, but it had something to do with a kind of minor embezzlement involving a sales client.

“I guess that’s part of his charm. Huh Marie?”

“I guess,” my mother said, poking at her meal.

And now, all these years later, I could see that my old man really had not changed as I watched him try to jimmy the door of the cabin.

“Dad. Not a good idea.”

My old man let out a whistle. “Well what do you know,” he said. “The door’s open.”

His dark figure disappeared into the cabin, and in the next moment light filled the inside of the building.

“We’re in luck,” he called out before emitting another whistle. “Plates, forks and knives, a frying pan, and even some grub.”

A horrible feeling of anxiety washed over me.

“Look at this junior,” he said coming back to the fire. “They had steaks stored away in a freezer.” He set the steaks on the ground and quickly unwrapped the aluminum foil covering the meat.

“For God’s sake dad. Put ‘em back. Really. This is crazy.”

“Hell junior. Finders keepers.”

I just looked at him.

His face was lit up from the flames, displaying the sheer delightful mischief of a teenage boy who’d just gotten away with shoplifting merchandise from a store.

The smell of fish sizzling in the pan over the flames filled the night air.

“You’re like a fucking kid,” I said.

My old man’s wicked smile quickly vanished.

“What the hell is wrong with you?” he said, turning angry eyes on me.

“What is wrong with me? What is wrong with you? Trespassing, breaking into a cabin, stealing.”

He continued staring at me. With a sigh, he looked down at the steaks unwrapped from the foil. “You want me to return them? Okay. Ya little pussy. I’ll return them.”

“I think that would be a good idea.”

“But I’m eating off these plates.” He shot me a sneer. “Okay?”

“Sure. Have it your way,” I said.

Eating that trout along the banks of Miller’s Creek on that May evening next to that small campfire felt deliciously forbidden. In a weird, twisted way, we were bonding. There was no denying it.

“Pretty tasty trout. Eh junior?”

“Not bad. Not bad at all.”

“Fresh from the stream cooked over a fire. Best way to eat trout.”

I saw the flash before my old man, a flickering and bobbing of light from upstream.

“Oh shit,” I said. “Now we’re in trouble.”

My old man had just pushed a forkful of meat into his mouth when he noticed the light. “Bullshit,” he said. He reached into his vest and pulled out a Glock. In the next motion, he snapped in the magazine before getting into a crouch and holding the gun with two hands. He looked more than eager to have an excuse to use it.

God no, I thought.

We remained there next to the campfire watching the light draw nearer, bouncing along the path beside the stream. My old man had the gun trained on the light.

“Hey you two.”

It was the voice of a woman.

“Identify yourself,” my old man called out. He held the Glock in one hand with the barrel pointed toward the dark figure.

“It’s me.”

“Mom?”

“Nana’s dead.”

“What?”

My old man lowered the gun. “Took the ol’ coot long enough,” he said, but not loud enough for mom to hear. Mom stood on the other side of the stream, holding the flashlight. I could just make out her dark figure.

“Why don’t you two come home?”

“You okay Marie?” my old man said.

“Just come home,” she said before retreating down the path.

“Wait up mom. We’ll walk with you.”

“Put out that damn fire first,” mom said. “What are you two doing on private land anyway?”

From the book, The Dying Light by Mike Reuther. His author page can be found at https://www.amazon.com/Mike-Reuther/e/B009M5GVUW%3Fref=dbs_a_mng_rwt_scns_share

November 19, 2021

The Dying Light – II

Photo by Mike on Pexels.com

Photo by Mike on Pexels.comMy dad remained a salesman throughout my boyhood. His returns home became less frequent, but somewhat predictable. He liked to show up when the mayfly hatches arrived. In late April, he’d appear for the Hendricksons. In mid-May he liked to come home for the March Browns, and he never seemed to miss trips home later in the month or early June for the Green Drake Hatch.

In the fall, he liked to fish when the Caddis flies were heavy in the air and the trees assumed their autumnal splendor. The old man, for all his faults, was a romantic at heart, I think.

“There really is something special about this place,” he said one soft spring night when I was seventeen and we were sitting on the porch stringing up our fly rods. By now, I’d grown old enough, in his mind, to accompany him on his fishing journeys.

And, I was catching fish, learning some of the old man’s methods for fooling trout. But there were other more important things I was learning. One night I recall particularly.

We had just arrived at a spot my old man called The Ledge. It was here where the stream turned into a high wall of rocks, the roiling waters carving a deep gorge into the creek bottom. The Ledge was always teeming with the creek’s share of big stream-bred brown trout, some of them eager to devour Green Drakes.

To reach The Ledge was tricky, not for the lame or aging angler. One had to wade slowly across the creek and negotiate a series of boulders and churning white water that could easily knock an angler off his feet.

“That’s why this place is one of my favorite spots,” he said. “No one fishes it.”

The air was filled with Green Drakes that night, a spinner fall that rivaled some of the famous ones occurring on Penns Creek or the Henry’s Fork in Idaho. Rings appeared across the surface, the trout making splashing rises to grab the insects.

Early on, as darkness began to fall, we each caught one trout. My old man landed a nice fifteen-inch brown while I caught a smaller one.

It looked like it might turn out to be one of those rare almost miraculous fishing outings, when trout would grab our flies on every other cast. But it wasn’t to be. The trout continued rising and slurping down the Green Drakes, but not our artificial offerings.

“This spot is usually good for giving up a few fish during the Green Drake Hatch,” my old man said.

“Maybe we should go to some other fly,” I said.

My old man reeled in his line and studied his fly. “Just one of those nights, I guess.” He peered out on the surface of the stream. It had become harder to see the rings on the water, but I could hear the splashy rises of the fish. My old man slumped down on one of the long slate rocks that fed into the stream.

I made another cast and watched my fly float until I lost sight of it as it continued into the dark waters near the overhanging rocks. The hard tug on the line and the splash came unexpectedly. I had a fish and a big one, but I no sooner yanked back the rod when the trout was off.

“Damnit,” I said, reeling in my line only to discover that the fish had torn away my fly.

“Must have been a big son of a bitch,” my old man said.

Up till that point, I’d lost interest in fishing, but now I was eager for more action. Almost desperately, I asked my dad for another Green Drake. My old man always brought flies he had tied himself.

He patted his vest. “Shit. I don’t have any more.”

“Really? Damn.”

“Sorry Billy. I left my one box of flies back in the car.”

“Goddamn it,” I said.

It was a small disappointment among a parade of much bigger disappointments in my life of late, one angst-ridden adolescent misery after another.

I had blossomed that senior year of high school. The rail-thin, shy kid with the acne had made a few friends. The kid who had never been much good at sports found out he had a talent for jumping over a high bar, but a leg injury cut short a promising track season.

I grinded my way through calculus and advanced chemistry, but when the top schools showed little interest, I resigned myself to attending one of the less selective colleges in the coming fall to study engineering, a practical career.

And then, perhaps the biggest disappointment of all–unrequited love. A girl I dated a few times, her sporadic attentions toward me I naively misread as something else.

In another week, I would graduate from that high school, starting my journey to a new life.

“I think I’m through for the night anyway,” my old man said.

“I guess we could fish tomorrow night?” I said hopefully.

“I’m leaving in the morning,” he said.

There was a loud splash in the middle of the stream and then the strange call of a bird.

“Why do you always have to leave?” I said.

We were both gazing out at the stream.

It was a question I had never dared to ask him, but one I had asked of my mother more than once over the years. Of course, I had never received a response to my satisfaction.

“Life’s complicated son,” he said. He had lit up one of his cheap cigars as he sat there on the long slate rock, peering out at the water.

“C’mon,” I said sharply. “What’s the deal?”

He turned to look up at me. There was hardly any light left in the sky now, and it was just the two of us there along the dark stream. His cigar glowed, like the last ember from a campfire. I hoped he might finally talk to me, like a real father.

“The dying light,” he said. “Always the best time to go fishing for trout.”

“Except for tonight,” I said trudging off.

I left him there—streamside, puffing on his stogie and staring out into the dark stream.

That night, from my bedroom, I heard my mother and him from their bedroom laughing, and later in the night, quarreling. When I woke up the next morning, he was gone. It would be years before I would see him again.

From The Dying Light, a short story by MIke Reuther. His books can be found at https://www.amazon.com/Mike-Reuther/e/B009M5GVUW%3Fref=dbs_a_mng_rwt_scns_share

November 18, 2021

The Dying Light

My old man always said the best time to be out on the water was around dusk.

“The dying light,” he said. “That’s when the trout are on the take.”

When I was a kid, those were mysterious words, haunting words.

“You mean, that’s when you can catch ‘em?” I asked.

My old man would nod his head and look off toward the creek, a cigar clenched between his teeth, a far-off look in his dark eyes.

For years, he never took me fishing when the sun disappeared behind the hills that threw shade across Miller’s Creek, the trout stream that flowed some hundred yards in front of our modest country house. He didn’t want me out on the water those spring nights when the trout were rising for the different species of mayflies over the water.

“When you get a little older,” he told me.

The problem was, when I got a little older, my old man was mostly gone.

Mom said he had restless feet. Mom’s own mother, we called her Nana, had a different interpretation. “He’s not the family-man type,” she said with a frown.

I was ten when I caught my first trout on Miller’s Creek, a stream-bred brownie with a belly the color of butter.

It wasn’t dusk and my old man wasn’t there to see it, a thirteen-inch beauty I proudly put on a metal stringer and brought home to show off to mom and Nana.

I caught the trout with a spinning rod on a nightcrawler.

“That’s okay,” he said, when he next came around a few weeks later. “I’ll teach you how to use a fly rod one of these days.”

I watched him wiggle into his waders before tying a Green Drake onto his leader. The sun was falling fast over the hills across Miller’s Creek, and he was eager to get out on the water to catch the evening hatch.

“Can’t I go with you dad?”

“The other fishermen might not like it,” he said. He bit down on an unlit cigar. “You might get in the way.”

“I’ll just sit and watch.”

He pulled the knot tight on the eyelit of the Green Drake and studied it. “Maybe next time,” he said.

I watched him hop off the back porch facing the creek, stop to light his cigar, before trudging down the hill toward the water. Near the creek, he turned and started off along the well-worn footpath that ran along the stream before disappearing into the brush, the smell of his cheap cigar filling the spring night.

He never told me exactly where he went. Years later, I would fish many of the same holes and riffles where he likely caught trout on those spring evenings when the mayflies were in the air and the trout were on the take.

I would wake up the following morning and follow the smell of fish into the kitchen where I’d find a half-dozen or more brown trout soaking in the sink.

“You gonna clean those or what Frank?” Mom asked.

She always sounded perturbed, but the strange smile on her face belied any true anger.

“After some of those scrambled eggs and sausage you’re so good at cookin’ up Marie.”

It wasn’t long before the wonderful smell of eggs and bacon and freshly made coffee permeated the kitchen. “Yes sir. Nothing like a good breakfast to start the day,” my old man said.

Mom turned from the stove and smiled and went back to her cooking.

“Where did you catch ‘em?” I asked.

“Now that’s a secret Billy boy. You know a fisherman never reveals his best fishing spots.”

“You gotta lot of secrets. Don’t ya Frank?”

Nana stood in the doorway glaring at my old man. She held a small basket of strawberries, the first batch of the season.

“Well … look’s who’s here. The judge and jury herself.”

My old man gave Nana a long appraising wise guy look as if sizing her up for some sales pitch.

“How ya doin’?”

Nana shook her head and shuffled into the kitchen. She was hard of hearing and diabetic with bad legs. Mom flashed a disapproving look at Nana before scooping up some eggs, sausage and bacon onto a plate and setting it down before my old man.

“Think I’ll head into the living room,” she said as she plopped the basket of strawberries on the kitchen table and limped off.

Outside the kitchen screen door, a bird squawked. I spotted a robin sitting on one of the branches of our willow tree.

“She don’t like me too well … does she Marie?”

Mom ignored the question. “Those strawberries look good.”

I picked one up and sank my teeth into it. “They are good,” I said, the juice running down my chin. “Make strawberry shortcake mom.”

“Yeah mom,” my old man said.

Mom’s eyes were like lasers on him. “Sure. Like you’re gonna be around to eat it.”

“Aw c’mon Marie. We’ve already been over that.”

“Right. We’ve already been over that. Why can’t you get a job close by? Why do you always work hours away … Elmira, Scranton, Rochester.”

“I’m a salesman. On the road a lot Marie.”

“He’s a salesman Marie,” called out Nana in a mocking voice from the living room.

My old man grinned. “She sure hears pretty good when she wants to.” He pushed himself away from the table and headed out of the kitchen.

Soon, he was dressed in his creased slacks, sport jacket and tie, his uniform for selling whatever product he was pushing at the time. My old man worked for many companies, selling everything from insurance to home furnishings. And he was always on the road.

“On the road. Where all the bums end up,” Nana said with disgust.

“He does provide for us,” my mom said. “Usually anyway.”

“I wonder how many hussies he’s paying.”

“Nana,” said my mom with a reproving tone.

“What’s a hussy?” I asked.

My old man had roared off down Route 16 in his latest car, a beat-up Lincoln Continental with dice hanging from the rear-view mirror.

“Never you mind Billy. Just never you mind.”

I had an inkling what a hussy was, but I dismissed the thought. Just before leaving us, I’d watched my old man and my mom embrace right there on the front porch and kiss long and passionately. Surely, there were no hussies in his life. My mother and old man …. They loved each other. I made myself believe it. At ten years old, the two things I wanted most in life were to catch a creel full of trout in the dying light and to have a normal family life with a father who was always home.

From the short story, The Dying Light by Mike Reuther. The author’s books can be found at https://www.amazon.com/Books-MIke-Reuther/s?rh=n%3A283155%2Cp_27%3AMIke+Reuther&page=2