Brooks Rexroat's Blog

November 8, 2019

Dispatches From Siberia #51: On Dualities

Last weekend, I traveled to a memorial service that was simultaneously among the most beautiful and heartbreaking things I’ve encountered. Heartbreaking, of course, because of an untimely death. But beautiful in the way he was remembered and what that remembrance means.

The service honored a teacher and mentor. I won’t name him here because his closest loved ones are grieving deeply, and their grief is not mine to co-opt in a blog post. But my experience there was meaningful and profound and, I think, worth sharing.

The reason for such impact is simple: the man we honored was someone who devoted the greatest part of his life and work to the elevation of others. Our cultures, our work, our salaries, classes, our resumes and CVs, our families, even our faiths often suggest or flat demand that we achieve without ceasing, and that we broadcast that achievement as broadly and fully and possible. Institutions and instinct demand that we publish and earn and elevate, that we move always upward and onward. That we earn followers and views, likes, sales, grades, esteem, credentials. It’s all marked and quantified—measurable and blatant.

This week, people flooded from across the country and world to honor a man who put his own energy and force behind the boosting of others. And at the end of his time, people stopped what they were doing and paid notice. The measurement, in this case, wasn’t in the small, daily achievement, but in a lifetime of gracious service to others.

That makes me ponder the meaninglessness of so much of what we’re asked to do, the ways in which we’re expected to behave as we navigate this life.

The ticking and marking and counting and weighing has utility, I suppose. But plenty of achievers are forgotten, in the end. Maybe it’s the givers that are worth remembering. Maybe we should place more of our focus there. All of us. You. Me. We. They. Whomever.

I cut into the regularly scheduled syllabus this week to put inject this concept into our work. We considered how it would benefit us all to remove some focus from the self, on occasion. And I could feel the questions, feel the mental flipping through the syllabi, their tentative schedule logs long demolished by the ebb and flow of the semester. I could feel the mental gymnastics trying to connect the concept of giving to points, to credit, to the ways in which it might impact the grade, the measurement, the weight of achievement.

This duality of achievement versus service has cluttered what it means to teach and learn. On Thursday, I dove into that duality. I gathered my class, collected and stashed their submitted work, and shuffled them out of our classroom—a cinderblock box painted lime green with a single large window that, on that day, was looking out over a drab, rainy streetscape with empty trashcans lingering in a jagged line along the curb.

We moved to a carpeted lounge, flicked on a couple of lamps. We grabbed illicit mugs from the faculty kitchen and I made tea and espresso and plain black coffee—whatever I could muster on the fly from my office stash—and flipped on a Klo Pelgag album then passed out every collection of poetry in my possession that hadn’t already been loaned out for other projects and inquiries. For 80 minutes we read. We read quietly, and read aloud and when we felt like it (by we, I mean me, too) we stopped and wrote. Then we read more. And we listened. All the bags and laptops and phones when into a secure storage room off the main lounge. Other faculty and students squinted or slowed up while passing, but nobody paid any mind. With just books and notepads, we waded through a playground of beautiful and wrenching and exuberant and crushing words

It’s the first time in a long time I’ve truly felt like a teacher, like in initiated something new in a class or group. At the end of our time, as I collected the stack of poetry books, I heard one student say on her way out of the room, “I didn’t expect to have so many feelings in a class.”

A classmate responded, “Yeah, that was intense.”

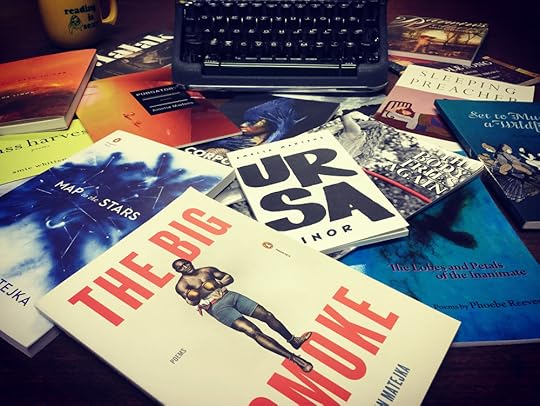

Among the artifacts of our poetic exploration.

There’s no place on a syllabus for intensity. For the number of feelings encountered during a meeting. No line on a resume. But it’s the most worthwhile thing that’s happened in my work this semester. Maybe this year. This decade, perhaps? But again—I count, I weight. I can’t help it because none of us can. What did I accomplish? What didn’t I?

In the best of circumstances, this idea of teaching and learning is hard to navigate. The best of circumstances are a gone glint in someone’s eye, at this point. Last week, my colleagues at a campus down the street received a memo from their new president, reminding them that denim is forbidden in the classroom because their “customers” deserve a professional experience.

I loathe to think what my life might have become, how much I’d have lost, if my best teachers had been asked to treat me as a customer. I loathe thinking of what’s happening to the generation for whom this thought is reality. Last week, too, a family member asked for some suggestions to help with a disciplinary issue in a middle school class. The administrator’s suggestion was to ask the middle schoolers what they feel like learning and adjust the curriculum to match.

I’d repeat that for emphasis, but I can’t bring myself to type it again—or even to copy and paste. You can read it again, if you need to. I can’t bring myself to give that idea any more space.

Everything transactional. Everything measurable. And if the weight is not substantial, the venture and the venturer are dismissed.

I’ve told my writing students this, and I’ll share it again here: if there was no assessment, no measurement, no accreditation or institutional development criteria to advance, I know exactly how I would teach. If my goal was simply to help students learn something, to discover, to equip them to seek without ceasing and to develop the sort of curiosity that will make their lives feel rich, we would do this:

We would meet for two weeks. We would glide through a crash course of reminders on all the techniques and styles at their disposal. Then, I would lead them to a library and abandon them. I’d tell them to find the novel of a literary icon, and then find one by someone who looks nothing like them. I’d ask them to find a story collection released this month, and one written a century ago. I’d ask them to find a memoir by someone whose ideas shock or terrify them. I’d ask them to find an essay collection by someone who inspires them. I’d ask them to read an indie poetry journal and then a collection by someone in the canon. I’d ask them to read a themed poetry collection about a topic they don’t understand. I’d ask them to find something that was self-published and something translated and something that just flat confuses them.

And I’d send them home to read.

Then, I would ask them to write when they are inspired or aggravated—not to worry about the genre or classification—just to write. I would sit in the classroom every day and wait, available to help them process what they’d read or written. To show them how to ask great questions when getting feedback from a classmate, when they felt ready. No workshop. No red-pen markups. There’s a place for all that, eventually, but if they’re going to learn or discover, I don’t want roots in antagonism. They’ll get enough of that, eventually. In November or April, we’d come back together and read to each other, out loud. We’d read from each other, silently. Maybe we’d write reflections.

I promise, that group of writers would be off to a good start.

But none of that is quantifiable. None of it leads to a resume line, or stacks a skill on top of another skill, which justifies the stacking of a course atop another course.

This is all hard and imperfect and will always be. But I can’t help—this week in particular—thinking about how the work I do can be shaded more fully toward the elevation of others, toward the real work of teaching that rests in there somewhere, behind the transactions and the dress slacks and the scales and percentages. It’s in there, I truly believe—a way to elevate the imperative to give—and though the digging might be hard, I’ve got a newly clarified need to seek out that path.

#

Brooks Rexroat lives and writes in Owensboro, Kentucky. Contact him at: brookspatrickrexroat@gmail.com

October 25, 2019

Dispatches From Siberia #50: Time

Yesterday, I had a lunch break.

My fellow lunchtime sunbasker.

This doesn’t seem like it should be too revolutionary. Not newsworthy, maybe not even interesting. But despite purposefully carving out time for a lunch break twice a week—something I hadn’t managed in a number of years—that lunch break generally descends into a quick trip to a fast food place, then a battle to digest while circling the faculty lots, vulture-like and ready to run down the first open parking space. Then, a quick sprint back to whatever task awaits.

Yesterday, though, I put everything down and left. The student essays, the paperwork, the emails—personal and professional—that needed to be answered. The good parking space. The half-finished Chemex beaker of coffee.

I drove home, boiled some fresh ravioli, splashed it in olive oil and black pepper, then led the puppy onto the back porch. I ate. Eeyore sat on my lap. The sun drove down on us, maybe with that kind of warmth for the last time this year.

It was quiet. It was slow. It was beautiful.

It was antithetical to everything else in life.

It's not just me. This is kind of what we do now, right? Our public greetings turn into weird blending complaint/boasts about our busy-ness. We make up committees and tasks and chores, listifying and quantifying, building resumes and CVs, building tenure records and business portfolios. As a professor, this is part of the game: higher ed has been careening toward the ruthless ledge of quantification madness for years.

We’re number-mad and we push ourselves endlessly, even if what we’re pushing for isn’t all that important. But it feels like it should be. It feels like every task is critical and imminently due, like we’re crushing someone’s soul if their report isn’t complete immediately, if their email isn’t answered in real time, if their essay isn’t auto-graded the instant it’s submitted.

Numbers are exhausting, and we’ve made them our oxygen.

This summer, I went to my first Major League Baseball game in a couple years. I was greeted with crushing intensity and needlessly elevated stress: a giant countdown clock on the scoreboard, prompting the pitcher to decide already and let loose the ball a little quicker.

When we’re even in a hurry at a baseball game, something’s gone off the rails.

But those seconds ticking off the clock are numbers, and numbers are connected to money. And numbers are oxygen and money is money and that’s all it takes to kneecap a century or so of leisure.

In the middle of all of that, the things I’m grateful for can’t be revolutionary. They aren’t newsworthy, or even interesting, maybe. The things I’m grateful for in this moment of live and this instant of time are quiet and fleeting: warm pasta balanced on my lap while nine pounds’ worth of dachshund squims into just the most advantageous sun-gathering spot.

Nothing. Else.

I’m grateful for that half hour of small quiet, of fleeting warmth, of tiny comfort, of the chance, when it comes, to finally exhale.

October 4, 2019

Dispatches From Siberia #49: When a Cup of Coffee (And The Guy Who Makes It) Reminds You Why You Do What You Do

It’s been a while since I’ve written an update for the blog. It’s been a while, truly, since I’ve written much of anything. Aside from a couple of scattered days when I’ve blocked out time well in advance, much of my time has gone into my students’ work: planning class sessions, grading, advising—and to working with the university’s track and field team, namely the sprint and jump squad.

That’s all to say, it’s been a busy time.

When I do get some hours to devote to my own work, it’s generally been spent on the business side this year: re-ordering book copies and merch, booking and preparing for readings, submitting work I’ve already written and on and on and on.

All that stuff is part of the gig. In the middle of it, though, I’m finding that writing is something that’s really easy to avoid doing, if you put your mind to it.

Coffee—the great connecter.

That’s why yesterday, on the first day of Fall Break (coincidentally, also the first day that felt remotely like anything that could be accused of being fall), I set aside the insurmountable pile of essays and portfolios that need grades and responses, and I drove to my favorite caffeine spot within reach of our western Kentucky home.

I drove 40 minutes to the White Swan Coffee Lab in Evansville and sidled up to the register to ask for a Chemex. When the owner, David Rudibaugh arrived to take my order, he asked what I needed for the day’s work, and I told him something light a sweet.

But then he did something that served as a much-needed kick in the shins. He called me by name, and then told me he’d enjoyed my book.

Because of the long drive and aforementioned schedule, it’d been months since I’d set foot in the shop, and I’ve never been more than a sporadic customer, though I would be if the earth could somehow fold in on itself and subsume some of the redundant miles of fields between us. But still he picked up the copy of “Thrift Store Coats” I’d left in the store’s give-and-take library. He took it home, he said, read it and passed it on—then found more of my work online and bought copies. It floored me, almost as much as the excellent cup he would go on to prepare for me, which I would deeply enjoy agains the backdrop of wrestling my way through some fresh paragraphs for a new novel.

He didn’t need to do any of that. I’d have kept buying coffee there, whether or not he’d paid any attention to me as anything aside from the guy standing at the register, ordering his next cup.

He didn’t need to pick up the book, certainly didn’t have to read it, and didn’t even need to put effort into knowing my name. As I took my seat and typed and drank, it was clear he knew a lot of names, knew a lot of people at a deeper level than coffee-buyer/coffee-seller.

And that was the kick in the shins, the pointed reminder I needed. Because for all the value of setting apart time to work and hone and craft and revise, the real function in making things is the chance to connect and form bonds with others. Others who make things of their own, and others who want the things you make, and others who don’t understand what you make or why. The best part about writing is the way that, in the end, it puts the writer in proximity to others—personally, socially, intellectually, digitally, and in person. And the same thing is true for master roasters and brewers of fine coffee, or designers of great furniture or…you get the point.

And no—this isn’t a public celebration that someone read my book. I am excited by and grateful about that—it is, frankly, a really cool feeling. But there’s more in it than that—the whole enterprise of creating, at its best, becomes a wonderful connective point, excuse to get to know each other just a bit better. A chance to extend a conversation just a bit further. A chance to exchange just a bit more than the small things we make with the time we wedge free.

There are times, truthfully, when I feel deeply isolated as a writer in my community. There’s not a hub of literature here. There are a handful of folks who practice as writers, but we’re loosely connected when at all. I sometimes envy writers working in larger cities, in literary hubs. But I have to—and we all have to, sometime—put the idealistic version of life aside and instead look for what is around us. Yesterday, it was a skilled maker who took time to appreciate someone else’s craft. Which makes me, too, want to be that person.

Tomorrow, I’ll sit behind a table at a literary festival in southern Ohio. Maybe I’ll sell and sign some books there. I certainly will buy some. In between those two acts, what I hope for most are the small moments of community and connection. Those are the instants that will make me continue to squeeze some moments of sentence-producing into my schedule.

But first: yes, dear students, I’ll get to your papers shortly.

Learn more about White Swan Coffee Lab HERE, then go visit David. Chances are, he’ll find a way to remember you.

December 31, 2018

Dispatches From Siberia: 2018 in Review

What a year. From the publication of “Thrift Store Coats” in April through the recent acceptance of my debut novella “The Busker” and the presale of the forthcoming novel Pine Gap, this was a year of payoff for the last decade of my writing work. Stories I started in graduate school as early as 2009 made their way into print, Thrift Store Coats collected the best of my published work over that span as well of a few newer pieces, and my stint at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference helped me to pivot from what I’ve done to what I’ll do next.

More than any printing, acceptance letter, rejection letter—and even in the middle of a strong year there were still plenty of those—the thing that made 2018 really tick was the chance to travel around the country and meet folks. The release of Thrift Store Coats facilitated trips to and readings in West Virginia, Ohio, Kentucky, Michigan, and Illinois. I had a chance to present at an academic conference in Claflin University in South Carolina, to offer a writing workshop at the transformational Tuxedo Project in Detroit, and to begin work as the fiction editor at burgeoning small press imprint Barren Press. I accomplished author bucket list goals like reading at Literati Books in Ann Arbor and participating in the fantastic InKY Reading Series, after which I fashioned my own brainchild, the Folk & Fiction series that ran its course in Cincinnati a few years back. Meeting other authors, moving around the country, asking and answering questions, and planning more and more words—it was a fulfilling year. That’s all thanks to the booksellers and campuses that welcomed me and so many other writers, to the publishers (especially the small houses) who continue to navigate a wildly difficult market and advocate on behalf of authors new and seasoned, and the readers who continue to seek out new voices, using fiction and poetry as a tool to navigate this wild world.

With gratitude to those folks, I’ll continue writing and publishing in the coming year, but will turn a big part of my focus to creating space for the next group of writers on their way up, whether in the classroom or at conferences, as an editor for Barren, through the curation of the St. Ann St. Visiting Writers Series and its forthcoming pod/videocast series, and as a reader and advocate for the great folks I got to meet this year. Every day, the depth and quality of the community formed between and amongst writers makes itself apparent to me, and I look forward to embracing it and working to create opportunities for others in the coming year.

My deeper thanks to those of you who’ve followed along on this journey: there are good things ahead, and I look forward to sharing them.

November 16, 2018

Dispatches From Siberia #47: Keeping Up With The Joneses

View from the Books by the Banks dais, pre-panel.

A few weeks back, I tabled for the first time at a book festival. Upon getting out of my car, I stopped and rested my elbow on the trunk, watching as one of my fellow tablers pulled a train of seven children’s wagons, strapped together at the handle and each laden with boxes of promotional items, life-sized displays of book characters, action figures, and assorted other swag.

I was in over my head. And not just a little bit.

A week prior, I’d given a reading at the InKY series in Louisville. The series is a longstanding and well-respected one with a decade-and-a-half of history behind it. I’d first encountered the event about five years ago, and it quickly became one of a small list of places I deeply aspired to read if I ever managed to publish a book. A couple of the event organizers marveled at—and even photographed—my display, which was elaborate for a literary fiction person: a foam board-backed 11X17 poster with book prices, a little bit of hipster bling from my good friends at Think Twice Buttons, a grey tablecloth, and a sticker-coated suitcase to carry it all. So there I was, the pinnacle of promotion for an event I esteemed. I’d have no problem, rolling into Cincinnati’s Duke Energy Center for Books on the Banks. My foam board and 1-inch buttons would be perfect…

And then, the wagon train.

Inside, authors were in costume. They brought adorable children and puppies. each of which attracted reader attention in its own awwww-inducing way. But I had some buttons. (Really cool buttons, by the way). NPR had a wheel of prizes. Darth Vader rolled in for a photo op. And there I sat, with a stack of books and not much else, a differential exacerbated by my location at the far edge of what was unfortunately tabbed the “adult fiction” section. Unsuspecting book buyers who took too quick a turn from the young adult table rolled into my space with questions like, “Is this a boys’ book or a girls’ book?”

My humble table set-up could not keep up with its neighbors—and maybe it didn’t need to.

That’s a jarring diversion, we’ll say, from most literary life, where writers take to conferences and Twitter to debate fine points of how we examine social, philosophical, and gender-connected issues fairly or thoughtfully within a text. But then the walk up figure the book is for girls, since it’s pink. It was informative to get outside the writer bubble. It was jarring, too, to have folks ask, as at least three prospective readers did, whether the book was conservative or liberal.

“It’s just a dozen stories about people—all kinds of them,” I said, all three times. All three times, the shopper set down the copy, clearly unsatisfied. And that’s okay, I guess, if a little sad. As complex and thoughtful and inclusive as we try to be while composing, the reality is that there’s still a big part of the public pining for the binary: right or left, girl or boy, good or bad. I get it—it’s easier that way. But less rich and, I think, less hopeful.

Did I mention the buttons?

My hopeful little book ultimately did okay that day. Digging back to my undergraduate marketing class, I tried to distinguish my little stack of realistic Rust Belt stories amongst all the human-sized wizard cut-outs. I disheveled the stack a little, made sure the side-by-side piles stayed uneven. I turned one book over, so folks could read the back without having to work at it—even though event staffers flipped it three times. I took to drawing little factories on the cover page, a small, unique housing for my signature. It had nothing on the graphic novelist to my right, but it didn’t need to.

My favorite part of the day was watching an enormous group of people interact with books. And for all the false binaries, there was some hope, particularly on the short story front. A solid half the folks who ended up buying the book started off with some version of, “I don’t normally read short stories, but…” And yet, they tried it anyway, and for that, I’m grateful. Those were moments that can buoy a day that largely consists of smiling and talking to people who want to know all about you and your book but really have no intentions of buying one—or maybe any books at all. There were the vultures, too, the folks who came in at the end of the day hoping for discounts, though, since a local bookstore handled sales, none of us had the ability to plunge prices, the way, say, folks do at a conference like AWP, where avoiding the baggage surcharge to bring home boxes of books incentives presses to practically give work away by the end of the day.

There were good conversations, not just with readers, but with fellow writers—not to mention a fantastic panel discussion about the PBS Great American Read series. Nearby writers lusted over my twin cups of Deeper Roots Coffee, snagged pre-festival from 1215 Wine Bar and Coffee Lab, while they nursed their own lukewarm Starbucks.

My book got its own name tag.

It all felt good. And frankly, at day’s end, it felt even better as I tossed my sticker-covered suitcase in the back seat and zipped out of the parking garage while my contemporaries wrestled their wagon trains back to their cargo vans.

Sometimes the Joneses are best left to their own device.

November 5, 2018

Dispatches From Siberia #46: Good Publishing News

Super Lamb Banana in Liverpool—which features in the forthcoming book The Busker.

A few weeks back, a colleague looked a me with the sort of look I’m sure I offered a thousand times during my time as a journalist: that look when you’ve just seen something awful and you’re trying act as though everything is normal while asking a compassionate question or two. The compassionate question was this: when was the last time you slept? The question, I had to admit, wasn’t easily answerable. I was in the middle of a grading spree across four very disparate courses, trying to tie up some gangly loose ends connected with a campus series of visiting writers, and I’d taken on the seemingly monumental task of chopping off almost five thousand words from a story that’s been stuck for a few years between a novella and a full-blown novel.

When the Ohio Writers’ Association, populated with some tremendous writers and editors—several of whom I’ve worked with (and had fantastic experiences in doing so) in connection with the Best of Ohio Short Stories series—put out a call for a Great Novella Contest, I wedged some trimming (in order to meet the competition word limit) into an already rail-thin mid-semester schedule.

The book is, among other things, a love letter to Liverpool, which I came to adore across a series of visits in 2010.

This time, the trimming paid off. I was deeply pleased to learn late last week that my novella The Busker won the competition and its prize—an offer of publication with the group’s independent literary imprint, Ragged Crow Press. I’m deeply looking forward to working with the team at OWA and Ragged Crow to polish this story further. It’s one I’ve been in love with for quite some time: this short book is a love letter to lots of folks: to the musicians I’ve known, played alongside, and watched struggle in the face of public indifference to their craft. To traveling. To the city of Liverpool where the story is set, and where I’ve made dear friends. To the ideas of determination and (yes, I’m going to say it) getting by with a little help from your friends. And thus, it’s an ode to the sort of community folks like Emily Hitchcock and Brad Pauquette have fostered through OWA up in my home state.

See the Great Novella contest press release here

The Busker follows Aiden Carlisle, a struggling street musician, in his quest to find a proper stage and an audience that maybe cares more broadly and the song or a coin at a time. He’s got nemeses out on the street, but he’s got some allies, too—if unlikely ones. I’m thrilled for this book to find a proper home it what I think is its best form, a short, quick moving novella that follows its protagonist through one primary quest. Thanks to OWA and Ragged Crow for supporting the novella, and for the readers and editors who gave this book a nod amongst what was, by all accounts, a stacked field of submissions.

October 5, 2018

Dispatches From Siberia #45: Makers of Beautiful Things

Yesterday, I crossed the Ohio River to do one of my favorite things: attend a fiction reading. Michael Martone, author of nearly 20 books ranging broadly in scope and style, was visiting the University of Southern Indiana, and I was fortunate to snag a seat in what would become a standing-room-only event space.

The reading was funny and touching and beautiful and harsh—in other words, it did the things the best writing means to. Afterward, students grabbed free brownies and filtered out and before maintenance folks came to deconstruct the room’s set-up, the faculty-writers lingered for a few moments. As I connected with colleagues from USI and the University of Evansville—most of whom I knew sparsely or hadn’t known at all before the event—I was struck at how quickly we all fell into good conversation.

On the way home, (in between dodging a couple dozen racing police cruisers heading toward this, I listened to iTunes on shuffle (as is generally my traveling custom) and within a few minutes, the music of friends began filtering through the list: The Minor Leagues and then Royal Holland, Tree Top, and back to another, older Minor Leagues tune. Purely: it was a joy of a trip.

There are some tough things about being an artist of any sort. When Jenna Fischer’s Pam Beasley Character in The Office stands and nervously checks her watch waiting for someone—anyone—to show up at her gallery display, well, let’s just say that scene hits close to home. I’ve seen amazing bands play in front of nearly hollow spaces. I’ve been on the stage for a few of those, too. Authors put years into books, travel multi-state jaunts, then sit and wait as three people filter in for a reading. There are conflicts and money issues, band fights in the parking lot, long hours staring at a screen or canvas and wondering if the idea which seemed at first so vivid will ever allow itself to coalesce into anything at all.

There’s difficulty to it, and real hardship.

But the silver lining, when it comes, is a good one. As I get deeper into a life of trying to create things, the one element that continually stands up as lovely and invigorating is the opportunity to spend so much time around other people who practice the making of beautiful things. Visual artists, musicians, writers, actors, spoken word artists and so on: it’s a good life, being around people who seek new depths of thought, new angles of seeing, and new takes on beauty. It’s an enriching life, one that demands flexibility and dynamic motion, not stasis. In other words, it makes me want to be better.

One of my favorite parts of working in academia is the opportunity to bring practicing writers to campus, and giving students a chance to connect with them. Part of the joy of organizing an event series like this one is to give folks an opportunity to get proximal to new and different art, yes, but more importantly, to provide connections with the people who devote their lives to creating beautiful, cautionary, uplifting, and complex things. That, in and of itself, is a unique sort of beauty. It’s a privilege to live a life connected to art, and I’m grateful for small reminders of that.

Brooks Rexroat is the author of Thrift Store Coats and the forthcoming novel Pine Gap. He teaches writing at Brescia University in Owensboro, Kentucky.

June 9, 2018

Dispatches From Siberia #44: An Anniversary List

A year ago this week, I returned from a year-long, Fulbright-funded year in the Russian Federation. Below is a partial list, shared in no particular order, of things Russia gave to me:

1. Several dear friends and numerous colleagues, connections, and acquaintances.

2. The two best suits I’ll ever own, and the best boots.

3. Scope and scale to understand the vastness and beauty of cities mentioned flippantly or in passing by Western media—or simply used as stand-in terms for a government.

4. Adoration for Montreal-based singer songwriter Klo Pelgag, to whom I was introduced in a St. Petersburg café.

5. An affection for the deeply complex Russian language.

6. A clearer understanding of life in America under its present administration.

7. New appreciations for the feeling of otherness.

8. First-person memories of deeply moving landscapes, cityscapes, aerial overviews and train-window panoramas: the great and diverse beauty of Russia.

9. An innate need to occasionally eat borscht.

10. Tenacity in the kitchen: the willingness to cook with whatever happens to be available.

11. A broader and bolder concept of community.

12. Sadness that for a century, major capitalist and communist states spent the world’s wealth defeating each other, rather than cooperating. We could have learned and taught so much.

13. The breathtaking knowledge of what it’s like to be struck by the sun at a different angle each day.

14. A reinforced creed: that people are just people, always and everywhere.

15. Deeper disdain for the fears that keep people separate.

16. Deep stretches of intentional solitude to reflect, think, imagine, and create.

17. A love-hate relationship with public transportation.

18. Adventure.

19. This understanding: No winter can phase me.

20. A longing for ubiquitous simple luxuries: coat rooms, boot polishing machines, hat racks that mean something beyond decoration.

21. Appreciation for a grand journey accomplished and the burning desire to do something like it again, and soon.

June 6, 2018

Dispatches From Siberia #43: A Year Ago Today

A year ago today, I stepped into Columbus John Glenn International Airport, freshly returned from a year in Siberia. The two-leg trip had taken me first from Moscow to New York, where I’d sat in the midst of a mission trip group whose members harangued the Russian flight attendant for hours over the malfunctioning satellite system the left them movie-less and cranky. From New York to Columbus, a male wine salesman spent the full flight teaching a female neighbor all about tasting notes and vintages while she sat, bored. As the plane touched down and he tried to solicit her telephone number, she rolled her eyes and asked, “Why, so you can waste more hours teaching me things I’ve known for years?”

Those encounters compressed the problem of so much human connection: everyone wants to tell. Few want to listen.

Listening is a hard skill, a struggle. I don’t have it fully developed yet, but more than anything, my time abroad, encamped in Siberia and supported by the Fulbright program, made me more eager to listen. As I type this, my desktop is filled with applications from Russian graduate students who hope in the near future to mirror my journey, and I’m struck by how eager each of them seem to listen and learn. Mission trips and sales treks aren’t inherently bad, but they’re founded on the goal of telling and persuading. I’m eternally grateful to have been sent elsewhere with a primary task set of listening, learning, and growing.

As I came down the escalator to the Glenn airport’s waiting to reunite with family, I was laden in all the things I couldn’t cram into my suitcase: a hat that would’ve been crushed if packed, a sweater and coat that hadn’t seemed quite so strange in Moscow as they had in sweltering Ohio, heavy boots, a necktie—all layered on to let my suitcase make weight.

But the greater weight, the more important one, had already been collected internally, through coffee shop chats and adventures into the Altai wilderness. It was the wealth only collected by listening and watching, learning and knowing others.

I’ve certainly not perfected the art of listening, but a year later, as I evaluate applications and think back on my time abroad, it is a good and warming thing to know that as the planes continue to cross the world—even the parts of it separated by barriers of politics, culture, language, and busted assumption—there will be listening and learners on board, people willing to hear each other, not just to preach and sell, but to truly try and know.

May 25, 2018

Dispatches From Siberia # 42: Time Machine

Nada Surf at the Mercy Lounge, Nashville, Tennessee. Photo/Rachael Rexroat

I remember picking it up out of the crate, glancing at the cover, and knowing there would be something useful inside. It was a couple months before college graduation and the public radio station on my campus was selling off all the “for promotional purposes only” discs that record labels had distributed, hoping for some college radio airtime. Morehead State Public Radio was, indeed, a college station, but it seldom played music and when it did—well, there were banjos involved, long before banjos were hip. Some Barsuk Records intern clearly hadn’t done their research on public radio formats in Eastern Kentucky, and I’ll be forever grateful.

See, that rainy afternoon on a sidewalk in front of Breckenridge hall, I picked up Nada Surf’s “Let Go” for a dollar. I’ve scratched up and re-bought three copies since then, so the band and record label were eventually made whole on my quasi-legal purchase.

Of course, I already knew the band: the talk-rock, one-off hit “Popular” blistered airwaves and video playlists during the latter half of my high school days—it felt like an anthem of life on the fringes of half a dozen social groups while ensconced in none of them. But that anthem played on the radio so often I never bothered to pick up the album and listen to the song’s smart pop-punk neighbors.

When I got back to my dorm that afternoon, I expected more of the same, maybe Matthew Caws talking over some more songs on the way to driving, angst-ridden choruses, but what greeted me was something closer to the space I mentally and emotionally occupied at the time: the soft but driving guitar of “Blizzard of ’77,” followed by mellow and thoughtful times wondering such things as, “what it feels like, on the inside of love.”

It’s become one of those rare albums where each song transports me back to a time, a place. “Let Go” drops me firmly back at the end of college and the start of professional life every time it cues up. It’s the kind of disc that when I hear one song, I kill the shuffle function and listen to the whole album a time or two.

That’s exactly what I did that first afternoon: I took the disc back to my room and listened through once while doing homework, then a second time as I simply sat and stared out the window, listening close. I was a journalism student, already smitten with words, but this was the album that snapped something inside my head. I hit repeat again and moved to my desk, then struck out on my first feeble attempt at story writing. This was the album that made me try turning words into art.

A wrinkle in time--at least for the evening: the Mercy Lounge, Nashville, Tennessee.

Nada Surf’s arc has mimicked my own life, as I’m sure it has for many fans. After getting mischaracterized as a one-hit-wonder then producing a gorgeous and critically acclaimed set in “Let Go” (“The Proximity Effect” was released in between, but just in Europe, where folks could deal with a good album that didn’t need radio singles), they followed up with “The Weight is a Gift,” which again struck me just where I was in life, with that heartfelt and apt sigh of a refrain: “Oh, **** it, I’m going to have a party.”

Shortly after that refrain, I ditched me career and headed back to grad school because, oh **** it, I was going to be a writer.

I was in grad school, peering out over the next phase of life when they released Lucky, complete with the seminal (and again, apt) line, “But baby ice is growing on the wing, you rolled the dice but you don’t know anything…”

Enough said.

By 2010, they released a cover disc, ready to borrow from someone else for a bit, and that’s how life felt for me, too.

Then there was “The Stars Are Indifferent from Astronomy.” I’d just moved back from Europe. Matthew Caws was living in Europe, releasing videos of himself singing “When I was Young” in a French church. All of that hit home.

Finally, a couple years ago came “You Know Who You Are,” with a general theme of getting past sadness, and there’s really nothing else that hits home quote like that message, especially in the middle of one’s thirties.

At my wedding, I danced with my mother to “Always Love;” I picked it because that’s what she’s always taught me, above everything else, and so that song resonates through my family in a memorable and important way.

I’ve cried along with “Your Legs Grow” and “Friend Hospital.”

I’ve tried endlessly to learn how to play the deceptively difficult acoustic riff of “Blizzard of ’77” on my own, to little avail.

I once saw the band in T.J. Maxx before a show. If ever there were a convergence of two of my favorite earthly things, it happened in that moment.

For all those moments and all that music, it’s still “Let Go” that’s the time machine, that makes everything stop and sends me back to a specific time and place, before it all got quite so confusing and riddled with second guesses and derailed daydreams. I like where I am now. But I love the moment that album transports me to, it just for a few seconds: the moment before everything.

Tuesday night, I took my wife to Nashville, where Nada Surf closed up the North American leg of their tour, one in which they celebrated that 15-year old album by playing it all, track by track. It sounded as glistening, as important, as full of promise and hope as it did the afternoon I handed over a buck and took those songs back to my dorm.

Before the show started, an old friend from my time living in Tennessee and a man I regard as one of the kindest humans on this planet, Spencer Huffines, walked up and said hi—another, brief but incredible timelime recap. The band dug deep, played songs I’d never heard them play live, going without an opener and hammering away for two-and-a-half hours. There were some folks in the crowd who chatted on their own between the hits and the highlights, at which point they tuned in and belted along with gusto. But most of us were locked in to the time machine, present and transported, thinking about what’d been and what could have been, wondering what’s next, and collected there by the brilliance of art.

The thing that happened in the Mercy Lounge Tuesday night was the very best of what any artist could hope for—the culmination of the life of the sort of ambition that was first sparked in me the night I heard that album.

Brooks Rexroat is the author of Thrift Store Coats, a new collection of Midwestern stories from Orson’s Publishing. He lives and teaches in Owensboro, Kentucky. Say hello on Twitter or Facebook.