Simon Pont's Blog

April 10, 2015

BRANDS AS TRANSMEDIA PORTALS -

WHERE ENTERTAINMENT MEETS MARKETING

(Picture: The DB10, on location in Rome.)

None of us should be satisfied with what we believe brands to be capable of.

Whatever we believe that capability, it can be more.

When Henry Jenkins first introduced Transmedia in his treatise, Convergence Culture (2006), he spoke of ‘media formats’ as ‘entrypoints into a story world’.

Jenkins talked not of brands but of ‘media’ as a story-telling tool.

On April 6th, 2010, the Producers Guild of America announced the addition of ‘Transmedia Producer’ to the Producers Code of Credits. A big deal (that some termed ‘unprecedented’), it marked the first time in the guild’s 60-year history that a new credit had been added to the list.

At the time, no one was thinking of a Transmedia Producer as anything other than a person - and certainly no one was thinking about brands.

Five years on... and it is high-time we consider the greater potential for brands as ‘story-world entrypoints’ and transmedia producers.

Simply, we need to think differently - more ambitiously - about what can happen when you bring together the worlds of entertainment and marketing.

We need to shrug off near-ancient, limiting definitions like “product placement” and “commercial interruption”, because these definitions hinder new ways of approaching the creation and funding of entertainment.

We’ve come a long from Mike Myers in Wayne’s World, mugging ironically as he flips the lid on a delivery from Pizza Hut.

Rather than brands as jarring interlopers within a story, we must explore how they can facilitate the creation of entertainment, and even enhance the content being made.

When director James Cameron wanted to explore the Mariana Trench (and document the expedition as an independent movie), he turned to Rolex.

In Deepsea Challenge 3D (2014), Rolex effectively serves as co-producer in the film’s funding, with logo presence on the final theatrical poster, side by side with National Geographic and Disruptive LA.

Rolex subsequently released the Rolex Deepsea with D-Blue dial. Watch buffs could barely find words to express how radical an act this was for Rolex, suggesting the luxury brand paragon to be breaking and beginning a very different commercial and creative direction to its past.

When director Sam Mendes took to the Pinewood stage on December 4th last year, announcing the 24th Bond movie to be Spectre, he also lifted the veil on the new Aston Martin DB10. No one groaned. No one derided the moment as gratuitous product placement. Rather, flashbulbs popped and a delighted Andy Palmer, CEO of Aston Martin, emphasised:

“In the same year that we celebrate our 50-year relationship with 007, it seems doubly fitting that we unveil this wonderful new sports car created especially for James Bond.”

In reality, Aston Martin will use Spectre as the platform for what will not be a one-off sports car, but the design direction of their remodelled Vantage. In 2017, anticipate straplines to the effect, “Built for James Bond. And now for you.”

Land Rover/Jaguar are also keenly in on the act, Spectre becoming the latest instalment in their ongoing brand renaissance. The Range Rover Sport SVR and Defender Big Foot will grab precious screen time, while Jaguar’s web site proudly spoiler-alerts, “The C-X75 will feature in a spectacular car chase sequence through Rome alongside the Aston Martin DB10”.

To label Aston Martin and Jaguar as mere product placements in Spectre is to miss the bigger picture. These are partnerships: brand integrations that add further layers upon the narrative world.

This year’s Kingsman, from 20th Century Fox, is a positive roll call of Cool Britannia brands. Think: Turnbull & Asser, Deakin & Francis, Drake, George Cleverley, Cutler & Gross, Smythson, and Bremont.

Under the banner of ‘Curated British Luxury’, men’s style destination MR PORTER invites us to dress like a Kingsman, offering a 60 piece collection.

Across their own digital and social graphs, 8 eight brands (9 when you include Mr Porter) all excitedly promote Kingman (and their “hand-picked collaboration” with the movie), so driving trailer views and product purchase.

Once upon a time, this might have been called merchandising - but it surely becomes something far more sophisticated when it loops in director Matthew Vaughn and costume designer Arianne Phillips at the pre-production stage.

Kingsman effectively presents retail brands as Transmedia entrypoints, fuelling movie anticipation, but more interestingly offering us the physical and mental props to get us in-character and wish-fulfilling.

It is clear that the entertainment business is learning the language of brands (and marketing) - and it will arguably do so faster than the agency world can learn how to make legitimate and singularly entertaining content.

Directors like James Cameron, Sam Mendes and Matthew Vaughn are showing us what the intersection of entertainment and marketing can look like: where brands can become buzz builders and movie co-producers, where they can become wish-fulfilment props and Transmedia portals.

I’m reminded of a scene from Robert Altman’s The Player (1992).

Griffin Mill: It lacked certain elements that we need to market a film successfully.

June: What elements?

Griffin Mill: Suspense, laughter, violence. Hope, heart, nudity, sex. Happy endings. Mainly happy endings.

June: What about reality?

Reality notwithstanding, to Griffin’s list I wonder, can we add ‘brands’?

SP.

Article as also appears in BrandRepublic, The Huffington Post and Business 2 Community.

March 19, 2015

RETAIL REINVENTION: Lessons from the digital rag trade

The meeting point of RETAIL and EDITORIAL was traditionally ‘THE MAGAZINE’. A style bible like Vogue or Harper’s, for example, would carry glossy colour ads of beautiful things, commercial messages betwixt a sacrosanct and inviolable editorial. I say ‘would carry’ when, of course, this practice still exists. Yet while it remains a present tense model, it is now so very far from being the only model.

Mr Porter, Net-a-Porter, Matchesfashion.com, ASOS: these are retail businesses. They may have physical form, a flagship store here, an occasional pop-up there, but they are ostensibly on-line retail businesses, a digital shop front to the world, looking to build fame and finger-clicking footfall. And what is so fascinating and instructive is how they approach their fame-building and business of selling.

Their approach is to not behave like a yesteryear retail business.

To sustain their business model, they seldom (if ever) resort to buying media to showcase and pump out their sales messages. To sell as loudly as possible, the aforementioned on-line businesses sell, by appearing not to sell.

Net-a-Porter single-mindedly describes itself as “The world’s premier on-line luxury fashion destination.” No mention of retail or buying. Net-a-Porter wish to be the embodiment of ‘fashion’. Vogue.com rather modestly by comparison headlines itself as simply offering “The latest fashion news, beauty coverage, celebrity style, fashion week updates, culture reviews, and videos”.

Figuratively, that once very clear and paginated line between full page glossy ad and editorial is today considerably more opaque. And the consequence is no longer, mercifully, some transparently disgraceful and badly merged ugly duckling ‘advertorial’. The consequence is that on-line retailers in particular consider themselves bona fide editorial engines. And in considering themselves as such, they are very legitimately becoming so. In written word and filmed footage, the growing multitude of Mr Porter’s are a fascinating hybrid of retail business AND editorial brand. Where the role of the latter is to suggestively, sexily, shrewdly sell us the former.

Where Revlon founder Charles Revson “sold hope” and not cosmetics, Mr Porter and its kind sell style and swagger, not merely shoes and belts and scarves. Which is why Mr Porter’s You Tube brand channel has 69k subscribers, and makes short videos of how people pack and get dressed that generate views in the hundreds of thousands.

This digitally empowering and line blurring world of ours is why Net-a-Porter is a weekly magazine (The Edit), a monthly magazine (Porter), an on-line TV channel (Edit TV/#NAPTV), and yes, “The world’s premier on-line luxury fashion destination”… where you can also buy shoes and belts and scarves.

Net-a-Porter is becoming a media empire. Net-a-Porter is becoming Vogue quicker than Vogue can become Net-a-Porter. And I applaud the fact that pioneering retail brands are no longer beholden to traditional media brands and channels to feature their “ads”.

I toast the fact that retail brands have their own voice, a seemingly bottomless well of opinions and advice, and are digitally creating their own communication channels through which to draw us in.

What is perhaps most insightful of all is how we - ‘The Once Distrusting Consumer’ - now show willingness to embrace (retail) brands as trusted and legitimate style aficionado’s and commentators. Retail is expertly and swiftly recreating itself in the image of media, while so much traditional media still struggles and scratches around for ways to evolve and monetise.

Once upon a time, we simply expected retailers to try and sell to us, and for editorial to be published and printed in a manner little different to when Johannes (Gensfleisch zur Laden zum) Gutenberg first introduced the benefits of movable type to the world, back in 1450.

“Once upon” is now starting to feel like “long, long ago”, because online retailers refuse to be limited by former definitions of what retail is and does.

Being progressive is about progressing into uncharted waters, driven by self-definition rather than the constraints of existing definitions.

Progressive is a small independent fashion label in LA making one of the most popular YouTube films of all time (Wren Studio’s; First Kiss for Fall 14; more than 90 million views).

Progressive is a coffee capsule company publishing ‘collectible’ lifestyle quarterlies and making consumption feel like elite club membership (Nespresso).

Progressive is a men’s retail website writing branded style guides that sit proudly on the most prominent shelves of Foyles and (almost) feel like a mere snip at £50 (The Mr Porter Paperback Slipcased edition).

Karl Lagerfeld once advised, “Buy only because something excites you”. It is clear that on-line retail is innovating hard to excite and encourage us like never before.

SP.

Article as also appears on The Wall, The Huffington Post and Business 2 Community.

February 12, 2015

BRAND POTENTIAL: NEW RULES

"BRAND -

a bundle of meanings, feelings and values, as seen and perceived in the eye and mind of the consumer."

That's always been how I've defined a brand to people. And it's a definition that's more than not kept me on the right tracks.

Brands communicate in hope that our view of them is consistent; that we may covet them and want to draw them close. Conversely, we all bring our own perceptions and prejudices, conscious and subconscious, to the table.

In consequence: 'advertising' is quite the see-saw, where a brand becomes the sum total of what it says and does - and of how we, the audience, interprets and so feels about it.

From the first dawn of brands, to the Digital Now, this concept of what a brand is has NOT changed.

But what is changing, ever changing, is the construct of how brands are built and perceived. Meaning 'advertising', in nature and nomenclature, is changing irrevocably.

Where advertising was the self-promotion of a brand or product, the agenda and motive ('Buy Me!') so abundantly clear, that construct is curdling far past its sell-by date.

I don't believe we can take a brand-centric approach to 'advertising' anymore.

Where 'The Brand' and 'What it feels it must urgently say' is the start-point, the consequence is a social bore too keen to brag, monologue and impose. History does not record the carpet baggers and snake oil salesman as hugely effective or particularly liked.

Simply consider 'advertising', by dictionary definition:

"To call attention to something, in a boastful or ostentatious manner, in a public medium of communication, in order to induce people to buy or use." (dictionary.com)

Boastful. Ostentatious. Not the most likeable or attractive of human traits.

Which all leads to a new set of rules.

For brands to advertise.

They have to stop advertising.

(At least, they need to stop doing so as governed by outmoded terms and former definitions.)

For brands to sell.

They have to stop selling.

For brands to win the hearts and minds they so crave.

They must earn those hearts and minds.

And they must earn them through a view of the world and a perceived role within it that is a clear and discordant break from the bygone advertising practices of yesteryear.

Which is all very exciting.

The really very exciting future for brands, for 'what a brand is', is now dependent on how open and ambitious we can be about 'what a brand does'.

Brands really do have the potential to evolve. Those brands that get it right over the next 10 years will pull away from the primordial pack, from the push messaging of boiler room marketeers. "Sell! Sell! Sell!" is not the future of branding.

I believe brands have the opportunity to elevate themselves to a Higher Order. And I don't mean this as being all and only about social causes and big ideals and 'doing good'. It's broader than that.

Higher Order doesn't have to be only about involvement in the worthy and heavy stuff.

Brands can increasingly become patrons and benefactors and the instigators of cultural causes, leading to things created that we all get to experience and enjoy. In some corners and categories of the world, this has occasionally already happened. American Express' historic involvement in the TriBeca Film festival and the funding of independent projects with film-makers like Ed Burns: this is one example. American Express, 'The Brand', effectively a silent investor and facilitator, an executive producer if you will, in an authentic creative outcome.

Consider Absolut vodka. 'The Product' is a white spirit, but 'The Brand' is a slice of iconic 20th century advertising as consequence of being a bona fide collaborator in modern art.

In 1986, Andy Warhol was the first of what now amounts to 850 commissions by Absolut vodka. The brand's modern art collection is one of the most valuable in the world, and, as born of the Absolut's patronage, is recognised as an important part of Sweden's cultural heritage. Modern art has inspired Absolut's brand expression, and Absolut continues to make a genuinely positive contribution to the modern art movement.

Any Warhol: ad funded. His work: branded content. The suggestion feels both right and wrong - because terms like 'ad funded' and even 'branded content' come with connotations of clunky editorial influence.

However, if we park 'ad funded' and the historic associations, and instead think 'BRAND FUNDED', where the brand can adopt more conventional titles like patron or co-producer, then marketing budgets become a very tenable way of helping drive the commissioning of bona fide creativity, whether that be art, radio plays, TV shows or even motion pictures.

This idea could not be more prescient, while still not being even close to original. Back in the 30's, the original producers of the radio and later TV 'soap operas' were (as the name suggests) the companies that made and sold soap to housewives.

Joining Procter & Gamble, Colgate-Palmolive and Lever Brothers from 85 years ago, now all brands are in the entertainment business. And their new start-point is not themselves, but how they may entertain us. From being brand-centric, brands must relearn how to be entertainment-centric.

The trailblazing brands of tomorrow will be those able to stretch into spaces of creative and cultural legitimacy, where they will ultimately say so much more about themselves, by explicitly saying less about themselves.

By becoming cultural benefactors and content co-producers, brands at last have a shot at reaching their potential, touching us all in a way that 'on the nose' advertising never could.

SP.

Article as also appears in The Huffington Post, The Wall and Business 2 Community.

November 17, 2014

IT’S NOT WHAT YOU SPEND, IT’S WHAT YOU SAY: Movie-Marketing by Brilliant Example

Nightcrawler (2015)

The Jazz Singer. 1927. A major commercial hit for Warner Brothers and a motion picture watershed. The ‘talkies’ had arrived, ‘the silent movie’ bowed into the shadows, and into the 1930’s and 40’s stepped the likes of Citizen Kane, Walt Disney, Gone with the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, Hitchcock, Kapra and Casablanca. The ‘Golden Age’ of cinema.

Movie lovers could debate long into the night whether the 1970’s represented a second kind of ‘Golden Age’ - and debate could further rage as to whether we’re currently witnessing a third Golden Age of cinema.

Consider this century. We’ve had Gravity and Avatar and the ever-expanding Marvel universe; Jack Sparrow and Disney finding their mojo with Frozen; Pixar’s Nemo, Buzz and Woody; Nolan’s Batman; Bourne and Bond rebooted; and The Potter, Hobbit and Hunger Games franchises.

Of the current 19 highest grossing films of all time (those being movies with a worldwide box office over the magic $1bn), 16 of those movies have been this millennium. Within the top 40 highest grossing movies of all time, only 4 movies date before 2000. Of course, not adjusting for inflation and the increasing cost of cinema tickets biases these numbers - but irrespective of adjustments, we are seeing the expenditure of much gold up there on our silver screens, and a global movie industry where the stakes and investments have never been higher.

JUST IMAGINE

Making a movie is seldom, if ever, cheap. Even those indie breakthroughs like Clerks and Blair Witch involved real people fronting their very real money. And at the other end of the spectrum, you have evermore annual tent poles rising on production budgets (un)comfortably north of $175m dollars. In support of that investment, you may well see some part (poster, trailer etc) of a global marketing campaign that cost a figure similar to production.

Imagine a $400m exposure? Just imagine you’ve cut all those cheques, while your brainpan itches with the recollection of how Disney took a $200m hit on John Carter - or you think farther back to movies like Heaven’s Gate and Ishtar, or Catwoman and Cutthroat Island? The wrong kind of pirates can fail, Halle Berry in a figure-hugging cat suit is no guarantee, and even casting Matthew McConaughey and having him take his shirt off still might not turn out as ‘awright’ as hoped. 2005's Sahara generated a relatively strong $122m box office… but cost over $241m to make. No one builds a career on those kinds of ratios.

The reality is that ‘too big to fail’ is no kind of logic, and that movies can tank for all kinds of reasons. Even good ones. Timing is one key variable.

Hard to believe, but It’s a Wonderful Life was a loss-maker for RKO on its release in 1946. It went up against Miracle on 34th Street and The Best Years of Our Lives. Easier to believe, World War 2 reduced Hollywood’s international release market by 60%. In consequence MGM's The Wizard of Oz and Walt Disney's Pinocchio, Fantasia and Bambi all underperformed.

Now for the good news. The cautionary tales are instructive, and while there’s no sure-fire way to snare lightening in a bottle, movie-marketing is being invited to experiment and express like never before.

BY BRILLIANT EXAMPLE

During a recent interview in The Hollywood Reporter, Tomas Jegeus (co-president of worldwide marketing and distribution at 20th Century Fox) acknowledged, “the increasing cost (of marketing a movie) is a massive challenge. Yet it's not how much you spend”, he added, “it’s the message. If we don't have the message right, nothing else matters”. Ultimately, Jegeus is talking to the fine art of knowing exactly what and what not to say.

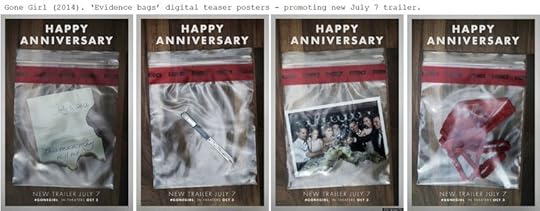

In the case of Fox’s Gone Girl, Jegeus exampled, “We couldn't allude to the twist, so we couldn't tell half the story. We focused the whole campaign on Ben Affleck's character. Once the movie opened, we decided we could say more.”

This summer’s Gone Girl campaign was a treat. The proposition was perfectly judged and crafted, and of all the creative assets, the ‘Evidence bags’ posters (promoting the July 7 trailer) were further evidence of ‘transmedia marketing’ as it can be done.

Boil it right down, and movie-marketing is all about the WHAT, WHERE and WHEN.

WHAT to say (message and execution).

WHERE to say it (media).

And WHEN (timing).

But that’s not to say marketing a movie is easy. Far from it.

This summer’s Edge of Tomorrow (make that: Live Die Repeat) provided vivid example of how a studio initially got the message wrong, and later marketed it right.

The title, Edge of Tomorrow, did the movie no favours. It sounds bland. Translate it into other languages, and it barely makes sense (not that it makes that much sense in English). Then compare its final theatrical poster work with Tom Cruise’s previous dystopic/sci-fi/blockbuster, Oblivion.

Audiences could be forgiven for thinking it was the same movie. Which is all a shame, because both movies are very good.

‘Live. Die. Repeat.’ however is a great (central premise) tag line, which became ever-larger in creative executions as Warner Brothers’ campaign progressed. For the movie’s Home Ent digital and disc release, the tag line had usurped the original title, effectively becoming the far better title.

The happy lesson in this is that it’s not necessarily too late to tactically adjust.

Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey is another example of how they ultimately - rather than initially - got the messaging right.

In 1968, 2001 polarised critics. Some gushed. Others just didn’t get it, and audiences initially inclined to the latter. On the basis of poor early box office, MGM were going to pull the movie. Exhibitors however reported to MGM that 2001 was gaining popularity with younger audiences, some of whom were eschewing popcorn in favour of “funny cigarettes” and LSD as they tripped their way through the movie’s psychedelic star gate sequence at the end of the second act.

In response, MGM marketing conceived a tactical poster months after the initial release: ‘2001: The ultimate trip’. You can see how the movie’s poster work evolved, the early illustrative work then inculcating the tactical creative, culminating in later theatrical posters that re-positioned the movie.

Whether 1968, 2001, or 2014, the delivery of What, Where and When requires invention and playfulness. How you tease. What you reveal. When you reveal it. What you hold back.

As a piece of compelling articulation, I’m a huge fan of Studio Canal’s tagline for The Imitation Game. “The true Enigma was the man who cracked the code.”

Churchill famously described Russia as “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.” The description could as easily stand for what the best teaser marketing looks to achieve.

I absolutely loved the 50” teaser for this Autumn’s Nightcrawler. It’s a character portrait. A perfectly honed, performed and edited piece of content in its own right; the thinnest slice of a movie you can’t wait to feast on.

And while Nightcrawler’s later official trailer ably did what it had to do, I wondered whether it fell into the trap of so many final trailers, of showing and telling too much of the movie to come? Trailers are at their weakest when they become über-abridged versions of the final cut they’re promoting. They are at their best when we’re left still wanting.

Left ‘still wanting’ is certainly what the recent trailer for Eastwood’s 2015 American Sniper achieves. Like the Nightcrawler teaser, it’s a ‘standalone’ piece of content, a 1 min 40 scene that hurls you instantly into the moment, positing, “What would you do?”

This October, the final trailer for the independently produced Keanu Reeves actioner John Wick also played a blinder. Where 47 Ronin was a poorly marketed Last Samurai/Airbender mash-up that compelled few, John Wick was the very opposite: a Death Wish style/80’s throwback that plays it deadpan, while knowing exactly what it is and how it’s ironic.

The Wrap hailed the R-rated action thriller “a financial coup for Lionsgate's Summit Entertainment, taking $14.1 million in its opening weekend, double the projection of some analysts and more than $5 million better than the debut of Reeves’ 2013 mega-bomb 47 Ronin.”

John Wick was the right message. And it supported a smart theatrical window. When Fox’s Colin Firth spy thriller “Kingsman: The Secret Service” pushed its Oct 24 release to next February, Lionsgate pounced. “That opened up this weekend”, explained Lionsgate’s Richie Fay, “when the main competition would be Ouija, which skewed young and female — the opposite of the demo target for John Wick.”

Lionsgate should also consider adding actress Elizabeth Banks to their marketing payroll. Check out her (pro)activity on Instagram and Twitter in the build up to Mocking Jay Part 1. Bank’s considerable ability to independently promote the movie’s she stars in can only strengthen any decision to cast her. Patrick Stewart obliquely spoke to this very point in his address at this year’s Cannes Lions. Stewart and McKellan's use of Twitter to gain following and ultimately draw attention to their Broadway play was an exercise in celebrity (re)branding and broadening your consumer base.

A few well-judged tweets and it turns out Professor X and former USS Enterprise captain is one self-deprecatingly comic guy. Who knew? Very few, until Patrick Stewart showed us.

And no mention of this year’s star turns would be complete without mention of Marvel, and how one supervillain’s act of sabotage can be another superheroes’ viral ‘pheno-meme’.

The most popular movie trailer of all time was a trailer no one was meant to see. Marvel’s ‘leaked’ Age of Ultron teaser was up to 45m views after 6 days and provided the perfect drum roll ahead of the studio’s October 28th Phase 3 announcement: a 9 movie batch over the next 5 years. There are certainly no strings on studio president Kevin Feige.

Of course, The Avengers is an established franchise with a strong and simple premise. But the point is that any premise is only strong and simple once you’ve made it that way. Genre-busting films like Blade Runner and Donnie Darko generated dismal initial box office because they got the better of the marketing minds that failed to effectively position and articulate them.

Back in 1964, it would have been just as easy to get the message wrong with Sergio Leone’s ground-breaking A Fistful of Dollars. Instead, United Artists struck gold. ‘The Man with No Name’ was a piece of pure marketing invention that gave mystique and cohesion to the spaghetti western franchise.

Fifty years later, and the 50 Paddington bear statues around London to promote the forthcoming movie is a similar act of marketing genius - the evocation of an iconic character that adds extra charm to the streets of London at Christmas time, as well as generating income for the NSPCC.

GOLDEN OPPORTUNITIES

In the movie industry, ‘entertainment’ is the thing of manufacture. There’s an investment in a tangible product, which everyone involved in the making hopes will sell. But hope is not enough and selling a movie is no fair-weather, plain-sailing task.

On the one hand, you have audience fragmentation, spiralling media costs, and an audience’s tech-assisted ability to edit and ignore. On the other (which is where it gets exciting), you have a digital playing field, transmedia story-telling, and the potential to grab pop culture by the throat.

A third Golden Age of cinema may be hotly debated, but movie-marketing is being granted opportunities that are surely golden enough.

SP.

Article as also appears in The Huffington Post, Business 2 Community, Medium and LinkedIn.

November 4, 2014

WHILE IT MIGHT LOOK A LITTLE LIKE A DUCK

The ad model changed. An unintended consequence of Tim Berners-Lee sending an html missive, and the butterfly effect of digital revolution that followed.

Technology evolved ‘media’, and turned a portable telephone into a pocket-able, indispensable screen and ‘Reality Augmenter’. The list of consequences doesn’t end there, of course, but the long-short: old ways are being replaced by new necessities. Former ‘proven conventions’ have become broken records, so many ‘established paradigms’ sinking like heavy-weight dinosaurs in an unforgiving bath of tar.

Specifically, for the world of brands and agencies, this Star Date 2014 of ours is a bright and shiny frontier – bold new ways to do things, exciting places for brands to explore – but with more than a few frisky and fast-moving meteor fields to also contend.

Back in the analogue days of happy dinosaurs and no meteor fields, ad agency swagger could write the kind of cheques its ego could indeed cash. You had Maurice and Charles Saatchi, drunk on ‘Nothing is Impossible’ Thatcherism even try and buy a bank, the Midland Bank. Has balls-out hubris ever soared to greater heights than an ad agency wanting to offer banking loans to its clients, so that they might then be able to cover the costs of the fees they’re being charged?

In 1987, Saatchi’s attempts to buy Britain’s fourth largest bank (with assets to the tune of $77bn) failed dismally, but the money in making ads remained for a good 15 or so more years. Right up to the early noughties, the Saatchi employee car park still looked like a Park Lane dealership, chock full of high-end autos of Italian, German and British persuasion. Walk around that same car park today and it’s a ghostly affair, a kind of paradise (make that: prestige marque) lost - and I paint the picture because it’s so very telling of a very simple truth: you can’t make ads the same way anymore.

In our here and now, few brand-builders would dispute the new manifesto theory of advertising – where PUSH messaging and audience INTRUSION is replaced with PULL messages and the call to create content of inherent audience appeal. It’s sense of the wonderfully common kind. Sensible in a way we can all prefix with ‘infinitely’. It’s just, while very few brands (or their builders) would dispute the challenge to make ‘content’ that’s inherently appealing, fewer still have found their way into this new blue ocean.

It’s misguided to simply drop the word ‘advert’ from the marketing lexicon, replace it with ‘content’, and then progress in just the same way, producing something that’s as much a brand-centric message as it ever was. The undisputable, game-a-changing fact is this: all brands are now in the entertainment business.

And the step-up-to-mike response is not to apply old world thinking and create an open pipeline of ‘brand films’ that (a) don’t entertain, (b) come across like a social bore and (c) do nothing to earn or reward their audience’s attention. The role of a ‘brand film’ is not to simply bang on about the brand with all the same yesteryear car salesman hustle of a slightly longer TV ad.

The role of a brand film is to offer a ‘content gift’, something that charms or rewards, and in some small or more significant way, makes the viewer’s world that little bit better and more satisfying. Even if only for a moment. I still come back to the genius of Forsman & Bodenfors combining JCVD, Enya, and a desert sunset to illustrate “the precision and directional stability of Volvo Dynamic Steering.”

Brands are at their best when they are patrons and benefactors and investors in culture and creativity. They are at their best when their participation is self-evident but near silent. Brands become more appealing by saying less, and doing so with subtly and sincerity. Where brands are loud and brash, heavy-handed and charmless in their communications, and sincere in an estate agent kind of way, then they deserve all the derision and negative buzz they get, and all the views and likes they don’t.

I like what the Folio Society are up to. Their content gifts are arguably of niche appeal, but the Folio Society know their audience and reward accordingly, offering human narratives that complement the beautiful books they make and stories they sell. Three examples, niche as said, but still very nice: Ben Jones discussing his illustrations for A Clockwork Orange, The Art of Letterpress and The Art of Marbling.

Often curious how fine a line it can be between something working… and simply not working. The same tone and ‘human interest’ angle as used by the Folio Society is applied by M&S here in their Best of British SS14 Collection – and yet, as a viewer it leaves me cold and bored. I just don’t care. And I wager that very few ever would. It’s a sorry example of ticking off the needs of a client brief (we want to talk about provenance and quality and craftsmanship) with a painfully literal, brand-centric solution. In contrast, consider the content delight of M&S Food’s ‘Adventures in Imagination’. Because of course, really great ads are actually just great content. Though this thought is one Chivas appear to be wrestling with, ‘uploading and hoping’ with a diverse range of output that misses more than it hits.

First, a modest hit: Chivas’s ‘Story of Craftsmanship’ (honouring a partnership with British watchmaker Bremont) is a simple idea. Mostly split screens uniting lots of circles, it’s very nicely executed, though not a patch on what I suspect was its inspiration - the very brilliant ‘Symmetry’ short.

In contrast, Chivas’ content output struggles to know what it is when you then consider it’s ‘Win the right way’ platform, recruiting Hollywood high-brow-and-hot talent like Oscar Issac and Chiwetel Ejiofor to misapply stylised gloss to a CSR message. While start-ups able to generate social as well as commercial capital is a big-idea-into-ideal worthy of loud applause, I’m not buying into Chivas as its sincere champion. The Issac and Ejiofor executions feel like ads striving to be something else, when they’d have been better off just being better ads.

If Chivas had absolute commitment to the cause, taking ‘Win the right way’ truly to their DNA, they’d stop feeling a need to still make the kind of throw-back work (check out: Charles Dance as bar man and brand archetype) reminiscent of a time where the epitome of cool was regarded by some as Crockett and Tubbs cruising South Beach in a white Testarossa.

It’s not that I mean to pick on Chivas. It’s just their content output illustrates the blue oceans and meteor fields all brands presently face. Brands have permission like never before, to make ‘content’ that is sincere and that audiences have always naturally craved. While on the downside, ‘bad advertising’ is arguably more found out than it ever was, its underlying urge to sell laid wholly bare.

The entertainment business is fundamentally about entertaining, about making money by being very good at entertaining, at rewarding and satisfying audiences. The lesson for brands is that pseudo imitation of the bona fide entertainment industry can lead to content-sins worthy of a Dr Frankenstein. It’s all well and good casting Hollywood talent, but making something that looks a little like a duck and walks a little like a duck is no guarantee of a winning quack or waddle. And while a masquerading platypus with a knack for impersonation might be rather entertaining, anything less literal and similarly false is likely to falter.

SP.

Article as also appears on BrandRepublic, The Huffington Post, Medium and Business 2 Community.

June 4, 2014

WHEN ART WORKS

Words. They equip us to define and explain, that’s their literal and ‘on the nose’ purpose. Their description in Hamlet (Act 2, Scene 2); “Words are the pegs on which we hang ideas”.

Words as pegs. For ideas. I’ve always liked that idea. What I also find so eloquently smart and cunning about words is what they don’t say, but rather what they evoke. Words don’t just convey meaning but incite feeling.

Beyond being pegs, words are triggers, provocateurs. Without even asking us to, words force us to feel. They prompt us to reveal ourselves, our opinions of things and view of the world and how we believe it should be. Here’s where I‘m going with this.

ART. MONEY. Two words, two triggers, two serious opinion grenades, no pin, chucked right into your lap. So many connotations, so much harbored opinion, such baggage.

I remember the first time I was pointedly asked about art and money, ‘The Art vs Advertising Question’, specifically, ‘Is advertising about art or commerce?’

‘AND’ NOT ‘OR’

1996, a sultry Spring day, muggier than ideal if you’re in a job interview. I was an applying graduate, feigning wisdom I still don’t have as I considered the semantic hand grenade. The Head of Planning across from me gave no clues as she thoughtfully opened the window in her office, before blowing cigarette smoke at it. I can’t say I nailed the answer, and I didn’t go on to work at McCann Erickson, but the question has stood the test of time considerably better than the unreformed social mores and interviewing techniques practiced in yesteryear Adland.

‘Is advertising art or commerce?’ It hasn’t taken me 18 years to formulate a decent reply, but it remains an unresolved and divisive polemic showing as much signs of wrinkle as Dorian Gray.

The answer to the question, of course, isn’t an ‘either-or’, but an ‘and’. ‘Art’ and ‘Commerce’ (more pointedly, ‘Money’) are not ninja’s striking poses on opposing sides. Certainly advertising is the inventive flux that helps ensure the wheels of consumerism glide smoothly. Consumerism is vital to the health of capitalism. Ergo, no denying it, advertising is commerce.

But. This is where the ‘And’ comes in.

Advertising is also, when done brilliantly, ambitiously, wonderfully, remarkably... an example of art. You betcha.

Advertising is artistry that can be registered on numerous levels. The art of human understanding and insight into what drives us and prompts us to behave as we do. The subtle art of encouraging us to behave differently, to feel something or something new about a brand, to buy into that brand’s representation and by extension, to part with actual cash in order for it to be ours.

Aside from these subtleties, simply consider the advertising we can see. Consider the genius print campaigns for Nike, Silk Cut, The Economist, Club 18-30, Wonderbra and Absolut. Advertising can, of course, be wildly creative, and is no less ‘art’ for being a message-carrier. Doesn’t all art try and communicate, on levels both literal and sub-textual?

But let’s now talk more of money, because this is where the water really muddies.

MONEY

We all need it, and most would agree that having more would, at the very least, be useful. Yet craving money, along with overt demonstrations of wealth, we typically find vulgar, in bad taste, rather unseemly.

We incline to link money with greed, and struggle to see the kind of goodness in it that Gordon Gekko found so easy. Akin to the Pleasure-Guilt conflict of Catholicism, money is as incendiary as they come, a hand grenade packed with conflict and cognitive dissonance. Money makes things better. Money makes things worse. With claims abound, that it spoils things; is amoral; overrides integrity; takes the fun out of it; “has ruined the sport”.

And it’s when we consider ‘money’ and ‘art’ in the same breathe, sentence and context that we really feel the eternal struggle.

For the ‘true artist’ does it for his art, never the money. It’s about the purity, the nobility, some kind of deeper truth on some kind of moral or spiritual plain that sits in a skyscraper viewing deck far above the amoral basement in which money counts its beans. And yet, I gotta say, to me this kind of posturing has always reeked high, with the thickest olfactory notes of bullshit. And adding an extra note is the notion that for art to truly be ART there needs to be some kind of suffering.

The starving writer, the penniless painter, the threadbare poet – caricatures that imply that hard yards have to we walked, like some kind of purge or pilgrimage. Nobility in adversity? The only thing in adversity is adversity.

What’s wrong with being paid, paid well even, for the art you create? That is surely every artist’s ultimate goal? Art shouldn’t be a not-for-profit endeavour. Quite the contrary, unique creative talent should and can be worth its weight in gold. Cashing in on your God-given talent has nothing to do with selling out.

The American ‘commercial illustrator’ Bob Peak is a personal favourite of mine. His movie poster and advertising artwork are collage scenes of high-end glamour, covetable lifestyles of 60’s swagger resplendent of the life Peak himself could afford to live.

Crack open John le Carré’s latest novel, A Delicate Truth. Inside front page, third line of his biog: “For the last fifty years he has lived by his pen”. Now that’s awesome. To be brilliant at what you do, and paid to do what you love. To be able to commercialise your passion. For half a century. Crazy cool. Doesn’t get cooler.

We might not write or paint or sing for the money, rather the love of it, but you can only turn passions into professions if someone applies a price tag.

I believe there is everything right with art being collectively viewed as something of fiscal worth, of people wanting to own it, and by extension, its value increasing.

In March 1987, top art sales entered a new dawn when van Gogh’s Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers went under hammer for £24.75 million (that’s $82 million in today’s dollars).

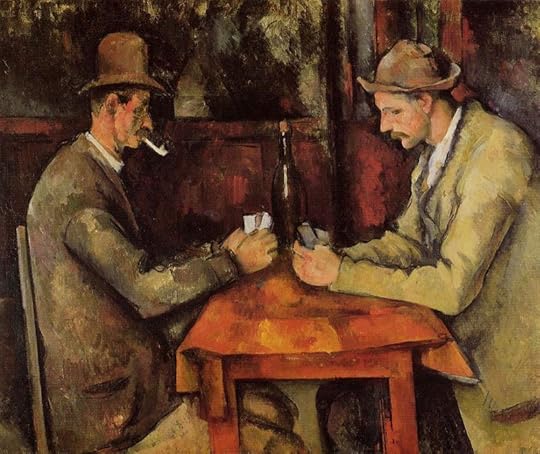

In 2011, Cézanne’s The Card Players became the most expensive painting ever sold. Someone’s for the cool sum of $250 million.

Rothko, Malevich, Warhol, Baishi, Kooning, Modigliani, Pollock, Picasso, Bacon (Francis not Kevin), Newman, Klimt, Johns, Munch – 20th century artists who’ve produced works bought for north of $50m.

Long short: when art works, it works in all senses of the word. Art commands monetary worth, which is as it should be.

But for me, where this all gets seriously exciting, is that it’s no longer 1996. Which is to say, while ‘The Art vs Advertising Question’ remains relevant, it’s no longer exclusive to those being interviewed at a big ad agency. What makes ‘advertising’ great, and who gets to make it is changing fundamentally. It’s becoming something anyone can become part of.

THE AD MODEL HAS MUTATED

“Mutation: it is the key to our evolution. It has enabled us to evolve from a single-celled organism into the dominant species on the planet. This process is slow, and normally taking thousands and thousands of years. But every few hundred millennia, evolution leaps forward.”

Professor Charles Francis Xavier, X-Men (2000)

In Professor Charles Xavier’s sense of the word, ‘advertising’ has mutated. This is where we’re at, what we’re witnessing, what we can all potentially be part of. Advertising’s evolutionary leap. Presently mid-air.

Push marketing, ‘magic bullets’, passive consumption, naïve consumers, silent witnesses: so much throwback thinking to the mass media conventions of a bygone age, to 1996 and considerably earlier.

Today brands have an opportunity to play a very different role in people’s lives. To create new opportunities for people. Consider Samsung’s ‘Launching People’ initiative.

Today brands can have a powerful role in society, and can contribute to society. They can mobilise and move things powerfully and positively forward. Consider the Arthur Guinness Projects.

Today brands can demonstrate genuine taste and be all the better perceived for their associations with independent talent. Consider Burberry’s Acoustic platform and Christopher Bailey’s helping hand in Jake Bugg’s career.

Today, great ‘advertising’ can potentially be made by anyone. If it’s content that turns people’s heads or prompts us to grin or shudder with delight, then brands like Samsung and Burberry and Guinness crave to be part of it.

Technological convergence, of devices that all connect, has inevitably rippled into cultural consequence.

‘Cultural convergence’ is about personal and creative liberation. The internet is an open-invitation to share, upload, express and create. Technology has become an opportunity-maker, an introducer, the connector of talent and inclination to new possibilities. From connectivity: connections.

The Digital Age is all about creating connections. The meeting of like-minds and kindred spirits. The connection of talents, of attractions, collaborations, mutual benefits and remarkable outcomes. So many synaptic snaps. Dots joined in new ways, something new, something brilliant. Sizzle, zing, spark. Wham. Not alchemy, but the potential for awesomeness.

‘Art & Advertising’ have never been more curvy and compatible bedfellows. In the words of Mr Jake Bugg, it’s time for advertising “to jump on that lightning bolt”. It’s time for brands to embrace their brilliant mutation and bare their adamantium claws.

Back in 1996, if only I could have talked about Wolverine.

SP.

March 25, 2014

Back Through the Looking Glass: The Lessons of Gravity

“Lowry … stood across the road from his subjects and observed. Often enough there are a number of individuals in a crowd peering back at him. They invite us momentarily into their world, like characters on a stage sometimes do, breaking the fourth-wall illusion.”

‘Sir Ian McKellen: My lifelong passion for LS Lowry’ (The Telegraph, 21 April 2011)

Breaking the fourth wall is always a bold decision. To explicitly acknowledge the audience is to deliberately break the illusion, an act as liable to pull an audience out of the moment as draw them conspiratorially in.

It worked for Alfie, it worked for Ferris Bueller, and considering Sir Ian McKellen’s remarks, it worked rather well for Northern artist LS Lowry.

Of course, art and movies and story-telling at their best have always used their magic to invite audiences into their world.

When Alice stepped through the looking glass, she broke through the fourth wall, crossed the divide and entered a land different to her own. This is why we love books and movies and plays. Because we are transported. We are exposed to a place other than our own. We become someone other than who we are, potentially are provoked into experiencing a set of feelings that are far from commonplace. And as you read this (yes, that was me breaking the fourth wall) you may fairly think, “this is all true, but nothing new.”

Where novelty always returns to the fray is when technological progress marries with creative vision, allowing story-tellers to keep challenging “the imaginary boundary between any fictional work and its audience.” (Wikpedia)

Consider Irmin Roberts’ reverse (dolly) zoom in Vertigo (1958) and Spielberg’s genius-stealing of it for Jaws (1975), in both cases evoking for audiences that “falling-away-from-oneself feeling”.

Consider the way Steadicam inventor Garret Brown tracked Danny’s Big Wheel tricycle tours through the hallways of the Overlook Hotel. Kubrick acknowledged the invaluable contribution Brown made to The Shining, using the Steadicam “as it was intended to be used – as a tool which can help get the lens where it’s wanted in space and time without the classic limitations”.

Consider the genius of Welles, Altman and De Palma and where they respectively placed their lenses to create the opening tracking shots for Touch of Evil (3 mins 20), The Player (8 mins 5) and Bonfire of the Vanities (4 mins 50).

Movies have always provided escapism, for audiences the suspension of everyday proceedings, where we suddenly stop disbelieving, forget who we are, and begin to vicariously experience something else.

In 1978, the marketing of Richard Donner’s Superman promised, “You’ll believe a man can fly”. In 2013, Zach Snyder’s Man of Steel treated us to Superman-cam, of not just watching a 21st C-GI Superman, but being part of scenes as if we could fly as him.

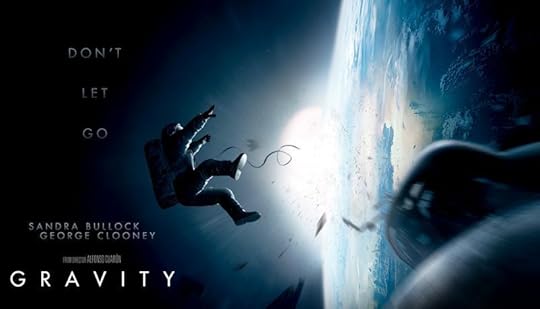

As ‘The Audience’ we have always inclined to step (like Alice) through the fourth wall and project ourselves into the scene – and the latest film-making technologies are making that natural inclination a more immersive, deeply felt experience. The success of Gravity, and particularly the success of the Gravity trailers, provide perfect illustration.

Gravity’s official trailer is close to 11m views on YouTube. It was the highest viewed trailer of all the movies nominated for an Oscar in 2013. Warner Bros produced a total of 41 official videos for the film, generating over 26m views. In consequence they have also re-written the rules for the role of promotional content in a movie’s marketing mix – because the trailers weren’t just serving to tease. They weren’t merely keyhole views of the main event – but visual spectacles in their own right. The official trailer is a 2 min 20 sensation of the very proposition that would have got Gravity the green light in the first place. Just imagine being lost in space, not in the “Danger Will Robinson” sense, but in the trapped in a vacuum, the ultimate bigness of nothing creating the most absolute sense of claustrophobia and despair? You get that experience from the trailer.

The trailer has the potential to become an event on its own merit, to be content that works standalone in its ability to mesmerise and hypnotise.

In the ‘All About Me’ age of social media documentation, first person chronicling and Go Pro capturing, Gravity’s trailer is the perfect content fix. Tellingly, the theatrical poster for Gravity also eschewed famous face exhibiting conventions. Like the image of Jaws ascending on an unsuspecting swimmer, Gravity’s poster shows its own ‘ultimate oh-no moment’, the image of a space man, safety line suddenly broken.

Gravity further evidences that it is a fascinating time for the marketing of movies, and indeed, for movie-making.

Second-generation 3-D is more effectively immersing audiences within ‘The Moment’. 3-D is at last evolving from the gimmickry of shooting arrows at us. With Avatar, Cameron created a very green and vividly rendered world, which started the 3-D ball rolling once again. Certain scenes in Prometheus were better for being seen with depth perception, the technology evoking a viewing experience that paralleled that felt by the characters. And then Alfonso Cuarón came along and changed the game again, making a movie that felt like you were watching from inside a gyroscope.

Whether watching Gravity in 2D or 3D, the experience is captivating, dizzying, disorienting. The audience is afforded 91 minutes of what it must feel like to attend space camp, and then have disaster strike. (Cuarón described his opening tracking shot as “a pain in the ass” – but then, maybe all great art is?)

I suspect Gravity might just be the dawning sun of a new genre in movie making: the ‘super-immersive’ movie concept. It will influence the movies that get produced and how they are later marketed.

While there has always been a connecting thread, a kind of umbilical cord between screen and audience, in where the lens is so remarkably placed, Gravity newly considers ‘the viewing sensation’. Cuarón is re-acknowledging that all the world really is a stage, upon which we have concurrent roles, where we serve as both audience and look to fashion ourselves as protagonist.

The Best Director oscar is gloriously deserving for a movie (and movie concept) that sucks us through the fourth wall and into the illusion of story and space. While we know that we’ll make it out of the movie theatre, our empathy with Sandra Bullock is such that there are moments when we feel it could be touch and go.

Watching Gravity isn’t life threatening, but to steal a line from Robert Redford at the end of The Sting, a tale of illusion and deception, “it sure is close”.

SP.

Article as also appears in The Huffington Post, The Wall and Business 2 Community.

March 21, 2014

THAT FIRST KISS

“That first kiss, that pause, just before, that pause spilling with expectation and possibility. Eyes. Mouth. Parting lips. Anticipation. Closer. Yes. Complicity. A submission, a moment shared in time and trust, a kiss offered, a kiss taken; a first intimacy. Kissing is The Business.”

Remember to Breathe: A novel (2012)

It feels like about once a quarter, a new viral ‘pheno-meme’ storms out across the internet. Each example makes it ever-clearer that all content is far from equal. The short form ‘video’ that goes stellar is fast becoming the ‘new broadcast’, not reaching everyone all at once in a single Super Bowl spot buy, but rather multiple millions in an ever skyward arc over a week or two.

Content that gets to 300+ views is an achievement. The 1,000 view marker is wholly kudos deserving as milestone’s go. 1m views? Well, that’s the super leagues, think segments from US chat shows like ‘The Tonight Show’ with Jimmy Fallon. Fallon’s lip sync battle with Paul Rudd – very funny – is clocking close on 8m views. And I still grin when I think of the little ditty Sarah Silverman put together in duet with Matt Damon: 5.9 views.

But the stuff that goes into the tens of millions – wtf, how many views?! – well, that’s simply epic, MASSIVE, a bona fide juddering of the zeitgeist.

The latest content ‘Must See’ is ‘First Kiss’, which I first saw early last week, when it was at around 20m views. Me = late to the party. As you read this, it’ll be north of 60m.

First Kiss got me wondering, why do I like it? Why does it work? What can we learn from it? Why has it caught the touch paper that is cyberspace?

Can viral video be deconstructed, the nature of its allure and communicability be some kind of calculation? Might there just be a genesis code upon which we can devise a circa three minute stream that games the online system? Or is every content pheno-meme something different, each its own exception to any governable rule, where the only thing we can really garner is that each is just bloody good and worth a watch in its own imaginative and inimitable way? I wondered. And I still wonder. And the thing with wondering is that it can easily lead to ‘listing’. Here are seven reasons why First Kiss works:

1. It feels real: ‘Authentic’ seems to be a word that never goes out of fashion in branding, advertising and film-making circles – and certainly, First Kiss doesn’t feel like fakery. It’s intimate, tender, very human; honest. It feels very real. The camera is openly capturing a genuine moment. No one is ‘acting’. And this is the really rather smart bit, because…

2. Its set-up makes it unique: For 99 folk out of 100, whacking a camera in their face changes their behaviour. They freeze, freak, act weird, turn odd. The camera is an invasion. Behaving ‘normally’ in front of a camera is actually abnormal. Curiously, in First Kiss, the camera ‘heightens’ the participant’s ‘naturalness’, first their awkwardness, then everything else. The camera’s presence actually makes the moment. Kissing a stranger is already weird. ‘The Camera’ compliments rather conflicts the weirdness. It adds to and captures and ‘gifts’ us a moment we otherwise would not have had the chance to see.

3. ‘The Familiar’ is flipped: It’s a great one-line concept, a ‘high concept’: “We asked 20 people to kiss for the first time.” But it’s not just 20 people, it’s 20 strangers. A first kiss is normally between two people who know one another on some level, human attraction established. First Kiss flips something universally familiar: make strangers kiss. The result is something awkward… But that’s not awkward. Because there’s consent and curiosity. And the casting of the ‘consentees’ is perfect. Everyone is appealing. They’re not airbrush beautiful. Nor are they ugly. They’re easy to look at.

4. Voyeuristic Permission: The digital age invites us to watch. In the ‘content game’, there is no game if there are no watchers, but understanding the emotional role of the online viewer is key. In Red Bull Stratos: we watch in awe. If watching live: awe and apprehension (will he make it, will he die?). With Epic Split: it’s a retro-rebooted slice of “did he really do that?” With First Kiss, how will they, will they kiss the way they look, what will happen then?

5. It’s ‘Happy-Making’: Human nature is portrayed as we hope, believe and want it to be. People kiss. No one’s hurting anyone. In fact, a few are really getting into it. Afterwards, they’re still goofy, but they’re also closer, different, relieved, relaxed, the intimacy has created something new which we’ve bared witness to. We have witnessed something transformative.

6. It’s nicely done: First Kiss is all very well judged. The emotional tone is just right. The production values are spot on. The monochrome really adds. The soundtrack ‘We Might be Dead Tomorrow’ perfectly complements, as does the absence of any over indulgent graphics or preachy final message. Nothing is heavy-handed.

7. It’s vicarious & prompting: I was having a drink with a film director buddy, recently single, who said it made him want to kiss a stranger, or kiss someone new, or do both. First Kiss is very relatable, emotionally accessible; easy to empathise with and get on the inside of. Even if you don’t want to kiss a stranger, everyone’s got a string of first kisses in their memory vault.

Content that makes us feel better about ourselves, about life, about what it is to be human – this, we are going to be interested in and drawn to.

Whether viewers know it or not, First Kiss was made by 3-employee US fashion brand, Wren. But not knowing doesn’t suddenly make First Kiss less. The film is deliberately, shrewdly, unbranded. To be judged in its own right.

As Melissa Coker, founder of Wren, points out, “It’s a very noisy world out there.” By filming strangers kissing, she has our attention.

SP.

Article as also appears in The Huffington Post, The Wall and Business 2 Community.

Related articles

That First Kiss

That First Kiss The Native... Returns

The Native... Returns Now Do Wear to the Left, 007

Now Do Wear to the Left, 007

March 14, 2014

GREAT BRAND THEORY, INVISIBLE DESIGN & NODDY HOLDER

“Why not write the crowds into the song?”

“Why not write the crowds into the song?”

Some men are born great. Others have greatness thrust upon them. Slightly abridged, but you’ll recognize the line: Shakespeare, Twelfth Night, passing comment on how our natures and our circumstances influence how we step figuratively up to the plate. Philosophically speaking, provocatively speaking, the line is also a bit of cheat in that it mashes together opposing schools of thought.

The Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle proposed ‘Great Man Theory’. Carlyle’s thinking was that greatness is the stuff of nature, leadership a slug of DNA code sitting snuggly (or absently) in the double helix. Great men are born that way. That was Carlyle’s reckoning.

Tolsty (he of War & Peace and seriously impressive beard) sat on the other side of the debating chamber. Leo argued man’s moments of greatness to ‘zeitgeist theory’, to the times we pass through and how we take whatever slings and arrows on the chin. Context makes us great.

As a formula for brands and advertising (and their potential role in culture), I think we can take sage instruction from Messrs.’ Carlyle and Tolstoy. Meaning, for one thing, that ‘the Bard of Avon’ would have also made a damnably shrewd brand builder.

I believe brands are made great. In making them great, I’d like to suggest that ‘Great Brand Theory’ is not in isolation and opposition to the zeitgeist. Rather, ‘Great Brand Theory’ is a brand intrinsically so designed that it’s open-minded and adaptive to change. A great brand is a flexible brand. It’s one that knows what to do with the opportunities, as and when they come knocking. Opportunities, of course, are the external factors, as determined by those Tolstoyan circs of the day.

The great brands have the skills to surf the zeitgeist’s swells and troughs. Ineffectual brands sink beneath them. With a final glug that’s equally ineffectual.

And in ensuring that brands surf rather than sink, a singularly simple question arises. What is our zeitgeist, ‘der Geist seiner Zeit’ (as Gerg Hegel phrased it back in 1848), this spirit of our 2014 times?

Certainly enough, it is a digital one. Meaning it is a technologically-empowered one. A creatively-enabled one. A ‘mobile computer in our pocket that connects us to the world’ one. By consequence, it is a liberated one, in that the Digital Age gives all voice and invites us all to like/comment/share and tweet/post/upload.

Our zeitgeist is not one where anyone’s role is that of passive and mute witness. Our zeitgeist is one of being actively invited to get stuck in and a play a part. And this all has huge implications for how brands can make themselves great, and how advertising must consider the role it gives people. Which brings me to Noddy Holder (and isn’t the non sequitur it may appear).

You may well be as familiar with the work of Slade as you are with the frequently quoted lines of Shakespeare. And even if you’re not so au fait with the former, I’d wager you could sing along to ‘Cum on Feel the Noize’, a track that first entered the UK charts at number 1 back in February 1973. It stayed there throughout March, selling half million copies in its first 3 weeks. It is said that the factory couldn’t press the vinyl’s quickly enough. Ten years later, US heavy metal group Quiet Riot achieved massive success, sold 6 million copies of their cover version, and then in 1996, UK pub rockers Oasis paid homage with their own take.

‘Cum on Feel the Noize’ might be a seriously good tune to mosh or jog to, but I also believe its success is due to what it’s about. I think it resonates with audiences, because it’s about them.

‘Cum On Feel the Noize’ saw Slade attempt to “recreate and write about the atmosphere at their gigs”. Front man Noddy Holder recalled it as, "how I had felt the sound of the crowd pounding in my chest". Co-writer Jim Lea added, “I thought — why not write the crowd into the songs.” (Source: Wikipedia)

“Why not write the crowds into the song?” I love this sentiment. I love the acknowledgement that a moment is defined by its audience, that they make it what it is. Without the audience, Holder & Co were just a group of crazy-haired guys up on a stage performing to an empty room.

Why not write the consumer into the campaign? Of course, this is what ‘Great Brands’ do. In our connected and converged age, great brands ensure their audience feels the noise by making them the centerpiece of the campaign moment. Great brands acknowledge that it is the contribution, energy and participation of the audience that defines the advertising, so making it a moment full of both noise and feeling. Campaigns that embrace the zeitgeist are campaigns that invite consumers to play their part. Great brands put consumers not just in control but ‘in character’.

Bud Light’s 2014 Super Bowl spot, ‘Ian Up For Whatever’ is a perfect example of a brand putting ‘The Consumer’ in character, of literally writing them into the campaign.

'Ian Up For Whatever' - Bud Light 2014 Super Bowl (#UpForWhatever)

The ad might center on Ian Rappaport, but we enjoy his adventures vicariously, our delight in watching turning the third person narrative into a first person experience.

The Heist, Zombie Run and Tough Mudder are recent additions to this burgeoning cultural trend in “first person/in character/’gamefied’ experiences. We now live in an age where we can hire zombies to chase us, and pay for the pleasure of tackling obstacle courses that electrocute us, while giving us permission to get as muddy as 5 year olds.

These very physical experiences reflect what has already taken place online, of the shift from ‘passive observer to active participant’.

Culturally, significantly, we’re moving more and more from ‘See it’ to ‘Live it’, meaning the designing of ad campaigns has become the designing of human experiences, of brands creating something for us all to live through.

Once upon a time, advertising campaigns were all about visibility. They were messages piped to us through static media channels. A big poster on a big flat poster site. 2D, unmoving, changing every 2 weeks. There was a time when poster sites couldn’t change image in the blink of an eye, and that change could not be prompted by, say, the Sun coming out or the passing of a plane overhead. In our analogue past, ‘media’ was rather unremarkable and ‘The Campaign’ was obvious in intent, on the nose in message, all elements quite literal and clearly visible.

We’ve moved from using media that makes the brand message ‘Visible & Literal’ to something that is much more ‘Staged & Revelatory’. 21st century advertising isn’t simply about the stuff that comes at you head on. It’s about the stuff that comes at you from the side, wraps round you, that creates a narrative context in which you have a role, with a desired emotion being all part of the plan.

Great brands are becoming cultural architects, their advertising becoming as much about the stuff you can’t see, constructs of ‘invisible design’, about the deliberate crafting of character-based first-person experiences.

Great men, great design, great bands, great brands, great experiences; none of these things happens by chance. In each case, our zeit invites it. But in making it so, we all have our parts to play.

SP.

Article as also appears in The Huffington Post, The Wall, Medium and Business 2 Community.

February 19, 2014

THE NATIVE... RETURNS

Epic Split. Volvo trucks (2013). Agency: Forsman & Bodenfors

I got into the advertising business because I liked advertising. I liked it back then. And I still like it. And it’s why I’m inclined to still call an ad an ‘ad’, and view advertising as something that can be brilliant and that may still serve to influence, even inspire.

I say all this because eyeing ‘Advertising’ head on right now, you can’t help but note the furrowed brow of existential angst. In defence, the ad industry isn’t alone. The angsty frown is endemic of our times.

Our Digital Age now pushes at the borders of previously understood meanings and practices. ‘How things once were’ now feels shaky; no longer proven. ‘How things can be’ becomes open rolling debate and ongoing exploration.

Challenges to why things exist and how they might alternatively exist is actually all very exciting. Yet speculation begets uncertainty begets possible misdirection. New words pop up, old words require redress and face inquiry. 'Advertising' is one such ‘Word & Deed’ that's been summoned to the stand. What the hell does it mean anymore? Just what is advertising? Is it fit for 21st century purpose? Or is it all a bit Betamax in an age of Blu-ray, its profile too Cro-Magnon for this era of cloud computing?

It was John Claude Van Dame’s Epic Split that really got me wondering. Some were quick to explain Epic Split (and its success) as an ad trying not to be an ad. It felt a little as if praise for this slice of viral genius was being given rather reluctantly. (At time of writing, Epic Split’s at 69.7m You Tube views.) Surely, some suggested, the only way any ad can be this popular is if it’s an ad masquerading as “great content”?

I’m not sold.

The only thing that’s great content… is great content… and isn’t it possible that great content can still actually be “an ad”?

My feeling is that we might be guilty of sucker punching ourselves. Ours is an industry that invented “New & Improved”, imbued weighty meaning to words like Plus and Ultra. From Ariel Ultra to Google Plus, the ad community will perhaps always be the most open-minded when it comes to a new formula (whether in tablet or code) – and ‘Advertising’, as an industry and as a noun, is getting its own ‘Ultra’ treatment.

The ‘Advertising Ultra Plus’ of our prime time hour goes by the strapline ‘Native Advertising’, the implication being that advertising sans prefix is potentially some kind of Old Wold paradigm putz.

Which leads me to suggest this. ‘Native Advertising’ is nothing new. At least, not in sentiment. To steal from a Thomas Hardy novel, I think we’re more so discussing ‘The Return of the Native’.

Native Advertising is nothing more than a returning articulation of a long-standing intention. It’s a reminder that brands must be built on one thing, on producing images and proposing ideas that are worth a damn; that are made of the stuff we all naturally want and enjoy.

‘Advertising’ is content (of a type), and all content has worth when it entertains or informs us. Entertain me. Inform me. Do either or both. Content that has a ‘pay off’ will always be worth my while and be the content I want and seek out. And there’s no reason that can’t assume the form of an ‘ad’.

Not wishing to come over all nostalgic, but off the top of my head, consider... Canal Plus’ ‘Never under estimate the power of a great story’, Guinness Surfers, the Stella Artois Jean de Florette-inspired series that came out of BBH in the 90’s. From the same decade and agency, add Levis and Boddington’s. Think (trust me, it’s fun to) Kylie Minogue besting a bucking bronco, brought to us courtesy of Agent Provocateur; Tiger Woods bouncing a golf ball on the head of his club; Terry Tate playing ‘Office Linebacker’ for Reebok; a John West fisherman kung-fu fighting a big bear. And this is all before I throw in Cadbury’s drum-playing Gorilla, TBWA’s ‘Get a Mac’ campaign and Wieden+Kennedy’s re-imagined Old Spice Guy. (If you haven’t clicked on at least one of those links, there’s something wrong with you.)

All of the aforementioned: content that naturally rewards. The fact there is a commercial agenda behind it, that it’s content “as brought to you by a brand”... well, that’s incidental. Native Advertising is a new headline that’s nothing new. It’s Clive Owen starring in 8 online movie shorts for BMW Films back in 1992. It’s Procter & Gamble, Colgate-Palmolive and Lever Brothers selling soap to 1930’s housewives via the ad format of daytime radio ‘soap operas’. (P&G still run a production arm.)

Just as in the 1930’s, I’d like to think that brands still have the capacity to become radio, TV and film producers. I’d like to think that ad-funded in these “native” times can simply encourage any brand to make a brilliant piece of content, while remaining editorially impartial. Similarly, I don’t mind if there is commercial bias if the ‘content’ makes me smile the way I did when I saw Bud Light’s “Ian up for whatever”.

Can we simply file ‘Native Advertising’ under the catch-all, "Advertising is dead, long live advertising"? I suspect we probably can. Let’s not be so quick or so premature as to lament the demise of ‘advertising’. Let’s unfurl that brow.

While being de rigour, I’d argue that Native Advertising is principally a return to timeless brand thinking. Which is something we should never tire of - where great content can be advertising, in that it needs to be smart and enjoyable, rewarding to watch and potent in its ability to persuade.

To this end, let me conclude by telling you that my 7 year old son is a fairly serious fan of superheroes, his favourite Avenger a photo-finish between Iron Man and Thor. I'm with him on that. But as much as my son likes superheroes, he likes super villains more. "Why, Dad, is Loki such a good bad guy?” he recently asked. "Maybe because he's really smart, and cunning, and has all the best lines?" This received a sagely nod from my son and a, "I think you're right."

Where ‘Epic Split’ was my favourite ad/native ad/brand film/content piece of 2013, Jaguar’s ‘British villains’ is already my favourite of 2014 - because it's simply so very satisfying to watch. Because my 7 year old thinks it's “brilliant”. Because it makes us both grin on the outside and glow on the inside. And because it reminds me that ‘advertising’ hasn't changed. Not the really good stuff.

Great ‘advertising’ can still be great, whatever age you live in or age you are. Great is the work you know the moment you see it, irrespective of the label you give to it.

SP.

Article as also appears in Medium.