Myles Dungan's Blog

October 5, 2025

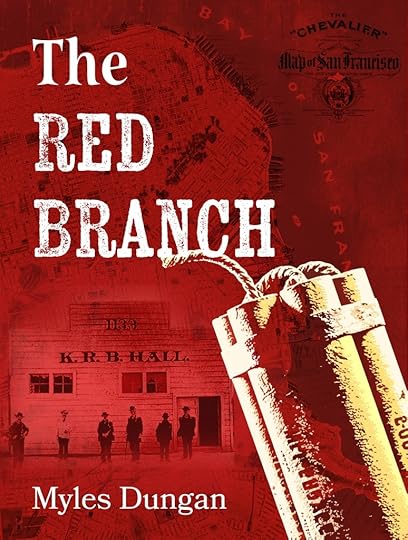

The Red Branch is ‘live’ and out there.

The book, not the arboreal appendage.

(Signed copies available from Antonia’s Bookstore)

After a great launch in Hodges Figgis (huge thanks to my old James’s Street pupil Tom Dunne for doing the honours) …

The Red Branch is already registering on Kindle. #21 yesterday in 19th Century Historical Fiction.

September 9, 2025

September 2, 2025

A NEW DEPARTURE

Nothing whatever to do with Parnell, Davitt and Devoy!

Perilously late in life I’ve started to make stuff up.

Sorry, no, I’m not completely losing it (though others might argue to the contrary). Nor have I developed any beguiling conspiracy theories about how cats are really our rulers and clouds contain messages that only the initiated can read.

It’s just that I’ve written a detective novel called The Red Branch and that the adventurous Etruscan Press in Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania (once a big Irish town) have foolishly offered to publish. Why an American publisher? Because it’s set in 19th century America. San Franciso in 1883.

Did you know that in the 1880s San Francisco unwittingly provided a consignment of dynamite to be used by Irish republicans to blow up some of the more interesting parts of London and remodel the British capital? That bit is 100% true.

That’s the starting point of The Red Branch, a mash up of detective and espionage fiction set in ‘Irish’ San Francisco with a cast of less than charming underworld psychopaths, crooked politicians, eccentric cops and an imported Irish detective trying to keep his head above water, or at least keep his head!

While most of the story is made up, as good stories should be, there is also a vein of historical fact running through the novel. Some of the characters are real 19th century San Franciscans. There are even a couple of genuine Anglo-Irish spooks. But most of the characters, like the plot, are complete fiction. No footnotes. No citations.

Ah, the liberation!

Here’s the blurb.

‘It’s 1883 and the Fenians are at it again, bombing high profile targets in London (Scotland Yard, the House of Commons etc). Some of the dynamite is coming from 6000 miles away in San Francisco. Because he’s Irish, expendable, and an annoying pain in the ass, a young London Metropolitan policeman, Robert Emmet Orpen, is despatched on a secret mission to the city by the Bay. His job is to infiltrate the Fenian front organisation in San Francisco, the Knights of the Red Branch.

His cover is blown before he sees his first cable car.

He finds himself on the San Francisco police force, competing for the attention of the flamboyant southerner, Sergeant Wellington Campbell, and the feisty Californian medic, Ophelia Williams. He ends up investigating a bloody revenge killing while going ten rounds with the seamier side of California’s murderous politics, and San Francisco’s Irish-American turf wars.

The Red Branch is part-detective, part-espionage, part-thriller, where the Rogues Gallery of malevolent characters and the sequence of deadly events are often observed with a wry sense of humour, and where you will be trying (and hopefully failing) to get your bearings until the final page.’

It will be in bookshops at the end of the month and is currently available for pre-order.

I keep waiting for a bolt of lightning to smite me for my effrontery. But I just didn’t want that mocking inscription on my headstone, you know the one.

‘He talked a lot of shite about a novel, but he never did write it.’

February 14, 2025

The sad fate of the real Saint Valentine

Cue the mushy music, break out the chocolates, take a wee moment to smell that garland of roses, and count those cards again, because, if you didn’t know that it’s St. Valentine’s day you’re either out of luck, or an incurable grouch.

We’ll get to the sad fate of the man after whom the day is named, a little later.

One thing you can say about St. Valentine—purveyor of love and affection, hero to card-makers, chocolatiers, intimate restaurants, the Post Office, and maternity hospitals around the middle of November—is that the various Churches in which he is revered, work the man very hard indeed. The afterlife doesn’t necessarily mean a restful retirement for holy men. Valentine is not just the patron saint of lovers you see. He doesn’t get any downtime after mid-February. In addition to his patronage of love, amour, amore, liebe, STDs and lovebites, he is also the patron saint of beekeepers. He is charged with their protection and with the sweetness of honey. Not only that but he is patron saint AGAINST epilepsy, fainting and the bubonic plague. He’s been doing quite well on the latter in recent years.

The man himself was a Christian martyr who met a sad and violent end around the year 270 AD in Rome, where his skull is still exhibited to this day. But, fear not, apparently a small vessel containing some of his blood—which has survived remarkably well after one thousand seven hundred and fifty odd years—is on display in the Carmelite Church in Whitefriar Street in Dublin. Hopefully it’s the blood of the correct Valentine, because apparently there are around a dozen saints and martyrs of that name who feature in regional Christian church lists. The most recent one was canonised in 1988. There is even a Pope Valentine, but he only lasted in office for forty days, in 827, so, wisely perhaps, no pontiff has assumed the name since the ninth century.

Is it significant, one wonders, that, apparently, there are no churches dedicated to St. Valentine in buttoned-down England, while there are dozens in his name in amorous Italy? Which brings to mind the title of that long-running 1970s farce No Sex Please We’re British. It ran in the West End for sixteen years. One of the Italian churches named after him was situated in the 1960 Rome Olympic village, though, by all accounts, the presence of St. Valentine is not essential for lustful carry-on in Olympic villages.

The problem with Valentine and all the saccharine of the day associated with his name, is that he was a Christian martyr. There is no getting away from the fact, as you sip your first prosecco of the night and dive into the Quality Street, that poor Valentine, to whom you owe tonight’s date with your outrageously handsome or beautiful escort, came to a very bad end indeed.

As regards the poor man’s demise, there is some clubbing involved, but not of the type that you might hope to be indulging in later tonight if that romantic dinner goes well. As with most of the early saints and martyrs, the precise details of his passing are disputed. But the consensus seems to be that he fell foul of the Roman Emperor Claudius, not the I Claudius of the Robert Graves books, who was a good egg, but Claudius the Second, who was more of a hard-boiled type. Valentine, or Valentinus to give him his Roman name, was accused of marrying Christian couples, hence his designation as patron saint of lovers. But Claudius the Second was a tad unsentimental about Christian nuptials. In fact he didn’t approve of Christians of any stripe. Aiding and abetting Christianity was a capital offence in third century Rome.

Claudius ordered that Valentine should be beaten to death with clubs—not the sort of end that we would associate with such a mushily romantic figure. The good news is that the beating failed to kill him. The bad news is that he was then beheaded, which did the job. Spare a thought for his dreadful end as the maitre d’escorts you to your table tonight. Actually … maybe save your reflections until tomorrow. Contemplating beatings and beheadings as you order the starter might spoil your appetite, or ruin that all-important frisson as you gaze rapturously into the eyes of your dinner date.

Do enjoy your evening.

February 10, 2025

New online lecture series – Free of Charge

January 31, 2025

MOUNT RUSHMORE AND THE FIFTH HEAD or

So, it appears that Rep. Anna Paulina Luna (surely there must be room for a MAGA in there somewhere?) has introduced a bill to add Donald Trump’s face to Mount Rushmore. What a spiffing idea. And what a shame John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum died in 1941 and won’t be around to finish the job he started in 1927. He would have wanted to be there so much.

The original funding for the monument came via the Mount Rushmore National Memorial Act, signed into law by Calvin Coolidge—they probably had to wake him up to sign it—in 1927. The presidential heads are 18 metres high (that’s 60 feet in American money), employed 400 workers to get the job done and, required the transfer of more than 400,000 tons of dynamited rock to other destinations. But, hey, you can get all this stuff on Wikipedia so go look there for more statistical information.

It took Borglum seventeen years to get the job done so, sadly, it’s unlikely that former President Trump will be around to see his face alongside George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Teddy Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln. Unless he lives to be 95. He might need to lay off the burgers if that’s going to happen.

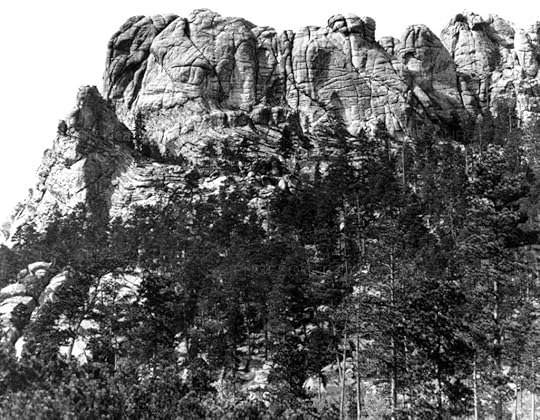

BEFORE

AFTER

Politically the most obvious place to put Trump would be to the right of George Washington. Sadly that’s not possible, unless it becomes a sort of Snapchat head, i.e it disappears shortly after it appears. Thomas Jefferson was supposed to go there, and they started work on him before they discovered the rock was unsuitable. They scrubbed poor Tom 1.0 and restarted him to Washington’s left. That would mean Trump would have to go to the left of Teddy Roosevelt (who smashed the big corporate trusts in the early 1900s) and Abraham Lincoln (something of a DEI champion given that he emancipated the slaves in 1862)

Alternatively why not simply scrape over Washington and just Trumpify his head. The first president has surely had his day by now. And he’s already got a wig! So the construction crew (Proud Boy volunteers maybe? Come on, they owe him) would be a-head of the game. (See what I did there? Wasn’t it utterly puerile? A bit like … never mind).

The very best of luck to Rep. Luna when it comes to securing from Congress the appropriation for this well-thought-out project. I’m sure the National Endowment for the Humanities would happy to stump up at least some of the cost. It’s for a sculpture, right? And a non-woke one at that. Perfect. Or maybe the tech bros might pass the hat around, once they find their way out of the President’s back passage. However, bear in mind that even when the dynamite and the man-hours have all been accounted for, there will still be ongoing maintenance costs. Who is going to pay for the annual re-bronzing? A ton of Leichner Camera Clear Tinted Foundation Blend of Orange doesn’t come cheap.

A word of warning to Rep. Luna, however. It’s only fair she be reminded that the Supreme Court, in 1980, back in the day when it was still a court of law, rather than The Court of King Donald, acknowledged the validity of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie in the case of United States v Sioux Nation of Indians. This Fort Laramie treaty should not to be confused with the 1851 treaty of the same name, which was negotiated by an Irishman, Thomas Fitzpatrick. You’re welcome USA.

The verdict in United States v Sioux Nation of Indians. recognised that the Lakota nation (‘Sioux’ is, apparently what their enemies called them) had not been compensated adequately for the illegal seizure of the sacred Black Hills of Dakota when gold was discovered there in the 1870s and Colonel George Armstrong Custer was sent in to protect the trespassing gold-diggers. A sum of $102m was awarded by SCOTUS, which the Lakota politely declined. They just wanted the land back. So it was deposited for them should they change their minds. That initial sum has now grown to more than $2 billion. By the time the Trumphead is completed it should be worth twice that. At this rate the Lakota will be able to just buy the land back. Who knows what they might do with John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum’s playground if they do. None of the current heads housed there have any reason to feel beloved of the indigenous peoples of north America.

Based on the 1980 SCOTUS decision the Lakota must have some moral right to intervene in any plan to add even more heads to the national monument (what price Rep. Luna is looking for more cash to include President Vance on the mountain when his term finishes in 2037?). Let’s face it, the Lakota might not be thrilled at the idea of honouring someone who tosses the name ‘Pocahantas’ around as if it’s some sort of side-splitting slur.

If the Lakota do object (and who knows, maybe they love him, just like 49.8% of the 63.9% of voters who turned up on 5 November) perhaps President Trump could Sioux them. He’s really good at that. (See what I did there? Wasn’t it utterly puerile?).

How about this for the Fifth Head instead? OK, maybe not. You probably have to be a US citizen (and not from Hawaii).

Is Saint Brigid a canonised saint of the Roman Catholic Church or a pagan goddess?

(But thanks for the bank holiday anyway)

I’m pretty sure I’m going to regret this.

I certainly did the last time I broached the subject. And let me begin by acknowledging our debt to St. Brigid, whoever she might have been, because we in Ireland now enjoy a bank holiday in her name. Bless her (lilywhite) cotton socks and her miracles.

Now that I’ve got that out of the way, some context. Back in 2019 I was doing a weekly radio column (on Fridays) for the RTÉ Radio 1 Drivetime programme called ‘Fake Histories’ which, as the name suggests, delved into myths that had, for one reason or another, become accepted as ‘history’.

Because one Friday fell on 1 February, the feast day of the Irish saint, St. Brigid, and because her very existence had long been the subject of controversy, I thought I’d have a go at that.

It was a really baaaad idea.

Within hours of the item going out on Drivetime the programme’s producer-in-charge (I’m really sorry Elayne!) was fielding calls from the press office of the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Dublin demanding either a retraction, or my head on a plate, or something along those lines. Because the Archbishopric of Dublin has nothing more important to think about than the veracity of the existence of someone who, if they ever lived, died almost 1500 years ago, the press office just wouldn’t go away. I had to produce chapter and verse to justify even the limited scepticism of the original piece. I wasn’t suggesting that Brigid was not an Irish saint, just that she, along with hundreds of others (including every Irish saint other than Patrick, who is Welsh) had been de-listed in 1969. Although, in fairness to the Archbishop’s press office I suppose I did suggest that she might not have existed. Maybe that’s really what got their goat. Fair cop really.

Bellow you will find the original script and underneath that the frantic justification designed to get the archdiocesan press office off our backs (sorry again Elayne!). A short cut through all the sources, something of a ‘one stop shop’ really is the entry for Brigid/Bridget/Brigit in the Dictionary of Irish Biography (my first port of call in writing the damn thing) where the very first paragraph of her entry tells us that, ‘Most scholars regard her as a ghost personality generated in the period of transition from paganism to Christianity, replacing the pagan goddess Brigit …’ QED! Well sort of anyway. I don’t think the press office was convinced.

https://www.dib.ie/biography/brigit-brighid-brid-bride-bridget-a0961And let me reiterate, I’m delighted that Brigid has become a feminist icon and I’m eternally grateful to her for the bank holiday, which has turned us into a nation of Brigidophiles. Or Brigitophiles if you’re a sceptic (see below).

Text of the Infamous Broadcast – 1 February 2019

Hopefully by now you will already have woven your traditional St. Brigid’s cross so that nothing I have to say on the subject of the eponymous holy woman will stay your hand as you twist the strands into their intricate pattern, and clip off the ends so that the extremities are neat and flush.

Because you may not like what you are about to hear.

Tradition has it that Brigid was born in Faughart, Co. Louth in the year 451, two decades after the advent of Christianity in Ireland. Her mother is said to have been a Scottish slave baptised by St. Patrick, so Brigid herself was born into slavery. She is recorded as having founded a number of monasteries, most notably in Kildare, or Cill Dara, the ‘Church of the Oak’. Among the Lilywhites she is known as Brigid of Kildare. While abbess of that monastery she founded a school of art which produced the Book of Kildare. This beautifully illustrated volume managed to draw the praise of the infamous Hibernophobe Gerald of Wales, making it the only thing about Ireland Gerald ever saw that he actually liked. Tradition has it that she died in Kildare in 525 at the grand old age of seventy-two.

Brigid is informally recognised as a saint in no less than three Christian religions, Roman Catholicism, the Anglican communion, and Eastern Orthodox Catholicism. But the devil is in the word ‘informally’ because in 1969 she, along with dozens of other virtuous early Christians, had her name expunged from the list of saints by the Vatican. The Vatican doesn’t just remove things, it ‘expunges’ them. It was a bit like a drastic cabinet reshuffle with lots of patron saints losing their portfolios.

Among those deprived of their haloes in this cull was Saint Christopher, patron saint of travellers and, worst of all, Saint Nicholas, the man who later became Santa Claus. So, while good old Father Christmas can still climb up and down chimneys, and bring presents to millions of children, as far as the Vatican is concerned he can’t perform miracles. Brigid was handed her P45 because there were serious doubts as to whether she ever existed. So, was she real, does she have anything to do with the weaving of reed crosses on 1 February – and please keep this to yourself—was she actually a pagan goddess?

As Brigid was one of ninety-three saints removed from the universal calendar in 1969 she also had her feast day officially revoked. So, technically, 1 February is no longer St. Brigid’s Day. There is still a saint called Bridget, but she’s Bridget of Sweden. She seems to have three different feast days, one in July and two in October. Meanwhile our unfortunate Brigid has none.

One suspicion is that she was stripped of her status just because she shared a name with a pagan goddess.

The eminent Irish historian Daithí O’hÓgáin thinks the woman we now know as Brigid might well have been chief druid at the pagan temple to the goddess of the same name, and that she was responsible for turning the temple into a Christian monastery. Her Christian feast day, also happens to be the date of the pagan feast day of Imbolc. Imbolc is up there with Bealtaine, Lúnasa and Samhain as one of the four great pagan seasonal festivals. Because it was equidistant between the winter solstice and the spring equinox Imbolc celebrated the beginning of spring. Which, in an Irish context is, you would have to say, the perpetual triumph of optimism over experience. Can any Irish person put their hand on their heart and recall a single St. Brigid’s Day that felt even remotely spring-like?

The Christian Brigid had a heavy portfolio of responsibilities– in alphabetical order these included babies, blacksmiths, boatmen, brewers, cattle, chicken farmers, children in trouble, dairymaids, fugitives, infants, Ireland, Leinster, midwives, nuns, poets, the poor, poultry farmers, printing presses, sailors, scholars and travellers. The pagan Goddess Brigid had it easy by comparison, she was in charge of fertility, which, let’s face it, can’t have been a major problem in pre-Christian Ireland.

The Christian Brigid had two miraculous talents which must have made her very popular indeed and will have convinced a lot of pagans that Christianity wasn’t so bad after all. She could control the rain and the wind, always a good trick on the rainy, windy, periphery of Europe and, with even more mass appeal, she could turn water into wine.

But is she a canonised saint? Sadly, not since 1969.

SOME SOURCES – AKA THE FRANTIC JUSTIFICATION

(Assuming you could be arsed)

Quote from Dictionary of Irish Biography

(Here is the opening paragraph of the entry for ‘BRIGIT (Brighid, Brid, Bride, Bridget) )

‘… reputed foundress and first abbess of Cell Dara (Kildare), is the female patron saint of Ireland , but it is uncertain whether she existed as a person. Most scholars regard her as a ghost personality generated in the period of transition from paganism to Christianity, replacing the pagan goddess Brigit, the Irish manifestation of the Celtic Brigantia. There is no contemporary evidence for St. Brigit, but she, or her cult, is well documented in the annals, hagiography, genealogies and liturgical literature.’

http://www.answers.com/Q/When_was_St._Brigid_canonized

As you may be aware, in 1969 the Catholic Church officially determined that details of several hundred very early saints were too obscure and uncertain to satisfy the modern criteria for congregational canonisation, and they were removed from the list of accepted saints. Brigid was one of these. Note that this does not necessarily mean that these persons were not saints; the Church says that only God makes saints, the canonisation process is for official recognition, and there are undoubtedly tens of thousands of uncanonised saints in heaven. However, considerable doubt has been expressed as to whether Brigid ever existed.

https://www.catholic.org/saints/faq.phpCanonization, the process the Church uses to name a saint, has only been used since the tenth century. For hundreds of years, starting with the first martyrs of the early Church, saints were chosen by public acclaim. Though this was a more democratic way to recognize saints, some saints’ stories were distorted by legend and some never existed. Gradually, the bishops and finally the Vatican took over authority for approving saints.

The official Roman calendar of feast days for celebration by the Universal Church (in other words, all over the world) does not have a saint’s feast day every day. The Church chooses saints to be celebrated worldwide very carefully — they must have a strong message for the Church as a whole. That doesn’t mean that other saints are somehow less holy — although some of the saints that have been dropped were legendary and there is little evidence they existed.

Before the formal canonization process began in the fifteenth century, many saints were proclaimed by popular approval. This was a much faster process but unfortunately many of the saints so named were based on legends, pagan mythology, or even other religions — for example, the story of the Buddha traveled west to Europe and he was “converted” into a Catholic saint! In 1969, the Church took a long look at all the saints on its calendar to see if there was historical evidence that that saint existed and lived a life of holiness. In taking that long look, the Church discovered that there was little proof that many “saints”, including some very popular ones, ever lived.

Religious orders, countries, localities, and individuals are free to celebrate the feast days of saints not listed on the universal calendar but which have some importance to them. And there are indeed feast days for saints every day of the year. As a matter of fact there are at least three saints for almost every day.

SOME RELEVANT QUESTIONS

Q: Is St. Brigid a canonised saint of the Church?

Q: Is St. Brigid on the official Roman calendar of feast days for celebration by the Universal Church?

Q: Was she or was she not removed from this calendar in 1969 along with numerous other saints?

Q: Is it not the case that St. Brigid only exists on local calendars (e.g Ireland, Australia, New Zealand) and is no longer on the Roman calendar.

Q: Where is St.Brigid’s name on the following lists of saints of the Roman calendar?

[Note – St. Bridget is not St. Brigid – she is a Swedish saint

https://www.roman-catholic-saints.com/saints-b.htmlhttps://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Roman_Calendar#Februaryhttps://www.franciscanmedia.org/sod-calendar/?sotdYear=2019&sotdMonth=02https://www.vercalendario.info/en/event/catholic-liturgy-year-calendar-2019.htmlhttps://findmysaint.com/feastsJanuary 24, 2025

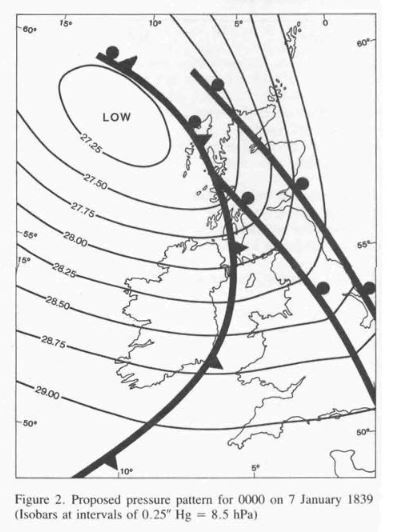

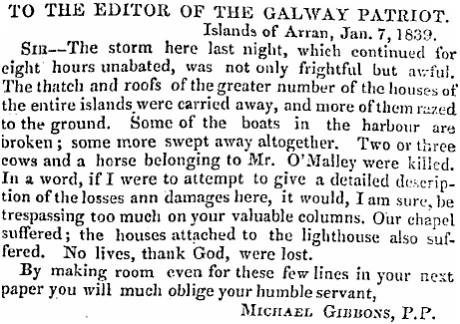

The (other) Night of the Big Wind, 6 January 1839

The Night of The Big Wind

Gradually, during the day, the winds rose. The first area affected was County Mayo where a strong breeze and heavy rains swept in from the Atlantic at around midday. Nollaig na mBan, the religious feast of the Epiphany, wasn’t going to be that pleasant a day after all. There was no Met Éireann in 1839.(We’d be lost without you Met Éireann).

There was a belief among the impressionable that the world would come to an end, that the Apocalypse would descend, on 6 January, and that one Nollaig na mBan would finally prove to be the day of Final Judgment. And that was before the Apocalypse of the Night of the Big Wind.

The squally weather that first appeared on the west coast quickly moved eastwards, and worse followed in its wake. The storm began to gather strength. Soon it was powerful enough to blow down the steeple of the Anglican church in Castlebar. As it moved across the midlands, the wind was gusting at over a hundred knots—around a hundred and eighty five kilometers an hour. (Gusts of 183km/h were recorded in Ceann Mheasa in County Galway last night). According to the scale devised by the Navan born hydrographer and naval officer, Sir Francis Beaufort, in 1805, that was a force twelve—hurricane force.

It was the most destructive wind to hit Europe in more than a century—another hurricane in 1703 had largely bypassed Ireland. But our geographical position on the western periphery of the continent, meant that this time early Victorian Ireland caught the main brunt of nature’s awe-inspiring strength. By the time the wind had blown itself out, upwards of three hundred people were dead, many at sea. Forty-two ships had sunk either sheltering, or vainly attempting to reach shelter. Most of the shipping damage was on the badly hit west coast. So strong were the surging winds that some inland flooding was caused by sea-water.

The Big Wind spared no one. Well-built aristocratic homes, and military barracks were destroyed or badly damaged, as were the bothies and cottages of the rural poor. Exposed livestock was vulnerable, not only to the Big Wind itself, but to the starving aftermath, as crops and stores of fodder were obliterated.

Ironically, given the prevailing conditions, much of the damage was caused by fire. The winds fanned the embers of turf fires, abandoned overnight in hearths. The sparks set fire to thatched roofs. These conflagrations were then spread to adjacent roofs, especially in small towns like Naas, Kilbeggan, Slane and Kells. Seventy-one houses were burned in Loughrea, over a hundred in Athlone.

The County of Meath was right in the path of the wind and the Dublin Evening Post reported that:

‘The damage done in this county is very great. Not a single demesne escaped, and tens of thousands of trees have been snapped in twain or torn up by the roots, and farming produce to an immense amount destroyed.’

The city of Dublin didn’t escape either. The tremendous gusts devoured a quarter of the buildings in the capital, as the wind raced across the Irish Sea to Britain and continental Europe, before finally dissipating. The river Liffey rose, and overflowed the quays in the centre of the city. A noon service at the Bethesda Chapel in Dorset street had given thanks, on 6 January, for deliverance from a potentially destructive fire—that night the wind whipped up the embers of the fire and consumed the church.

One of the unexpected consequences of the Night of the Big Wind came almost seventy years later, after the British government introduced an old age pension for the over-seventies. As the formal registration of births in Ireland had only begun in 1863, many septuagenarians, legitimately entitled to a pension, had no birth certificates to prove their age. One of the ways of ascertaining their entitlement devised by civil servants was to ask the question ‘Do you remember the Night of the Big Wind’. If they did, they got their pension.

Hurricane force winds destroyed property, and killed hundreds of people and animals, as ‘The Night of the Big Wind’ struck Ireland one hundred and seventy-eight years ago this month.

December 5, 2024

LAND IS ALL THAT MATTERS: THE AUTHORS CUT 3

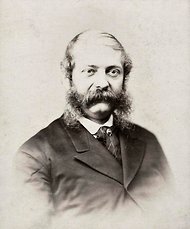

THE AMERICAN JOURNALIST

William Henry Hurlbert under coercion

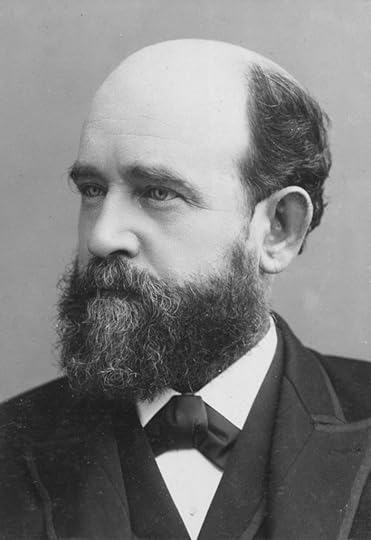

William Henry Hurlbert

Sightings of the Lesser-Spotted American Journalist (auctor Americanus) in Land War Ireland were so frequent as to be without scarcity value. Most (Henry George, James Redpath) came down firmly, or gently, on the side of the Irish tenant. This is what makes the observations of William Hurlbert, one-time editor of the New York World, more provocative. He took the opposite tack to most of his fellow American scribes during the Second Land War. He was described by Michael Davitt (whom he interviewed in 1888) as ‘a coercionist chronicler for Mr. Balfour’[1] and clearly set out his stall in the introduction to his narrative, the two-volume Ireland Under Coercion: The Diary of an American, published in 1888.

The class war between the tenantry and their landlords … which is now undoubtedly waging in Ireland, cannot be attributed to the historical grievances of the Irish people. The tradition and the memory of these historical grievances may indeed be used by designing or hysterical traders in agitation to inflame the present war. But the war itself … has the characteristics no longer of a defensive war, nor yet of a war of revenge absolutely, but of an aggressive war, and of a war of conquest.[2]

Given their experience of crusading American journalists ‘going native’ and siding with tenant against landlord, the leadership of the National League must have wondered what they had done to deserve the attentions of William Henry Hurlbert.

The most obvious question prompted by William Henry Hurlbert’s employment of a literary wrecking ball in his coverage of the Second Land War, aka the Plan of Campaign is: did he begin his journalistic quest (if indeed it can be described as such) with certain pre-conceptions, or is his work based on observation and an ex post facto assessment of what he witnessed? Was his mind made up before he started, or was it still open to argument and observation?

Most Irish nationalists firmly believed that Hurlbert’s cards had been marked well in advance of his arrival in the country, either by self-interested champions of Tory policy or by his own innate political prejudices. Davitt asserted that Hurlbert’s anti-Plan malice derived from an earlier failure to obtain Irish nationalist support in a bid to secure a posting as US ambassador to London. It also had a clear ideological basis. The socialist dogma of his fellow (and more successful) New York-based journalist, Henry George, was anathema to the politically conservative Hurlbert. In his introduction to Ireland Under Coercion, the former New York World editor fulminated against George’s creed of land nationalisation, describing it as ‘confiscation’ and going on to compare George’s template to the manner in which ‘the State proceeded against the private property of rebels and traitors’.[3]

Henry George

That he came from a staunch ‘Dixie’ Protestant family (he had a brief stint as a Unitarian minister) may have coloured his attitude to Irish Catholic nationalism and its tributary agrarian campaigns. But Hurlbert was not necessarily philosophically entrenched and incapable of changing his mind. Take his very name, for example. He was born William Hurlbut in Charleston, South Carolina in 1827 and was educated at Harvard. However, when a printer made a mistake in creating a business card—designating him as ‘Hurlbert’—instead of insisting that the offending objects be immediately immolated, he was so taken with the misprint that he changed his name in accordance with the error. Despite his birth in the ‘deep South’, he was an opponent of slavery, albeit he was an anti-slavery Democrat rather than a Lincoln-supporting Republican. After a lifetime of bachelordom, he obviously reconsidered his position on connubial bliss and married at the advanced age, even for a bridegroom, of fifty-seven. Neither, while on his Irish travels, did he exclusively seek out the sort of opinions he seems to have most wanted to hear. Although it is clear from his narrative that he preferred the company of landlords, like Richard Stacpoole in Clare and Charles Ponsonby in Cork, he also sought out the views of Michael Davitt and the fiery Donegal priest, Father James McFadden.

The title of the work derived from his visit to Ireland might suggest to the unwary that Hurlbert was completely ad idem with his journalistic compatriots from the First Land War, otherwise why highlight the word ‘coercion’ in the title? However, Hurlbert, in his use of this freighted codeword is not referencing the stringent provisions of Balfour’s Crimes Act, but the intimidatory tactics of the Irish National League and its local enforcers. United Ireland described Hurlbert’s work as ‘libellous’ and ‘fit to take its place amongst other grotesque foreign commentaries’.[4] To that sublime journal of the British establishment, The Times, however, fresh from its own ‘Parnellism and Crime’ accusations of thuggery against the Irish party leader and his associates, it was ‘entertaining as well as instructive’.[5]

Hurlbert’s work is exhaustive (two volumes and 653 pages in length) and highly partisan. He includes masses of minute polemical detail—amounts held in savings accounts in banks located near Plan estates, or the (scarcely relevant) number of public houses in the main urban centres of County Clare—but his twin tomes are also clearly influenced in style by gossipy contemporary travellers’ tales. With an eye to a more commercial market, he frequently branches off into detailed descriptions of some of the exquisite landscapes through which he travelled.

The first ‘tell’ when it comes to the political slant of Ireland Under Coercion (after his combative introduction) is his account of a visit to Balfour within hours of his arrival in Dublin in late January 1888. The chief secretary was in ‘excellent spirits’ and displayed much of the nonchalance that consistently aggravated the native antagonism of nationalist politicians towards him. Hurlbert opines, tongue affixed in cheek, that Balfour was ‘certainly the mildest-mannered and most sensible despot who ever trampled in the dust the liberties of a free people’.[6] From the bourn of that ironic swipe—within the first twenty pages of the opening of Volume One—there was no possibility of return for this traveller. It may even have been the case that Hurlbert arrived in Ireland with an entirely open mind and left Dublin Castle charmed by the affable side of Balfour’s nature. If so, his subsequent failure to secure an early balancing interview with Davitt in Dublin might have compounded his hostility to the Plan. He eventually tracked down Davitt in London and conducted an oddly ‘soft focus’ interview that seems to have had as much to do with the latter’s commercial schemes—the development of a wool export business and the opening of granite quarries in Donegal and Mayo—as it did with the renewed agrarian conflict, in which, of course, Davitt was not directly involved. Hurlbert did not include in his itinerary any of the acknowledged leaders of the Plan. He did, however, as noted above, interview and accept the hospitality of a number of the major landlord targets of Plan activists.

It is impossible to encapsulate a work of more than 600 pages in a few paragraphs but it is worthwhile highlighting Hurlbert’s visits to Donegal and Clare, and his treatment of two assertive Roman Catholic priests, Father James McFadden, parish priest of Gweedore, and Father Patrick White, parish priest of Milltown Malbay. He appears to have developed a considerable rapport with McFadden, despite their obvious ideological differences. White he did not meet in person, but his account of the latter’s activities caused the priest to threaten Hurlbert with a libel suit.

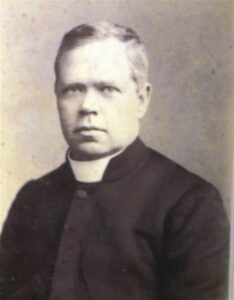

Fr. James McFadden of Gweedore

James McFadden was forty-six years of age in 1888. He was a thick-set, bulldog-like man from a comfortable family background with a very sure sense of his own importance (‘I am the law in Gweedore’[7]) and a history of loyalty to agrarian causes stretching back to his involvement with the Land League. McFadden had been radicalised as a witness to the activities in Donegal of those two notorious evicting landlords, William Sydney Clements, 3rd Earl of Leitrim (murdered by his tenants in 1878) and John George Adair (responsible for the Derryveagh mass evictions in 1861). In 1880 McFadden had also been witness to a much-publicised tragedy when five of his parishioners drowned after a flash storm flooded the Gweedore church in which he was saying mass. McFadden himself managed to escape death only by jumping from the altar through a closed window. McFadden did not brook dissent or opposition from his parishioners and was known locally, in suitably hushed tones, as ‘An Sagart Mór’ (The Big Priest) despite his small stature.

In the year of Hurlbert’s visit to Gweedore, McFadden spent six months in jail in Derry for a seditious speech and for organising boycotts and a rent strike—the initial sentence had been three months but was doubled on appeal. In 1889 he would be at the centre of a far more serious episode when an attempt by an RIC Inspector, William Martin, to arrest him after Sunday mass on 3 February, resulted in a number of McFadden’s parishioners beating Martin to death. McFadden was among those charged with murder arising out of the killing but was allowed to plead guilty to the lesser offence of obstruction of justice. At which point McFadden’s bishop intervened and moved him to a new parish out of harm’s way and banned any further involvement by the priest in agrarian activity.

But that controversial tragedy was in the future when Hurlbert arrived in Gweedore, one of the most immiserated parts of an impoverished county, in early 1888. Most of the land in the area had been acquired in 1838 by Lord George Hill, an improving landlord (with all the negative as well as positive connotations of that designation). In 1845, just as the Great Famine was about to take hold, Hill published a self-regarding memoir, Facts about Gweedore, which outlined many of the changes he had brought about in the area. These included the acquisition of almost half of his estate land for his own purposes. This was a regular feature of landlord ‘improvement’ and was bitterly resented by evicted or potential tenants who were obvious losers in such scenarios. In 1889 McFadden published a riposte entitled The Present and the Past of the Agrarian Struggle in Gweedore, in which he ridiculed Hill’s book as a publication, ‘which might, perhaps, with more regard to truth and accuracy be called ‘Fictions from Gweedore’.[8] The parish priest claimed that the landlord’s ‘improvements’ had failed to benefit anyone but himself. Hill died in 1879, as the First Land War was gathering force in Mayo. In 1888 the Gweedore land, an estate of 24,000 acres, was owned by Hill’s heir, Captain Arthur Hill.

Lord George Hill

In a letter to the Derry Journal in September 1887, McFadden threw down the gauntlet to Captain Hill, twitting the latter with the observation that ‘he may, by the aid of his Winchester repeater and a Coercion government, hope to make gold from granite, but it takes little fore-knowledge to prophesy that the effort will fail him’.[9] McFadden proved a determined and energetic adversary for Hill and the RIC. He appears to have had little in common with the aristocratic Hurlbert, yet, when they met, the two men got on famously, with the American journalist enjoying the hospitality as well as the company of the turbulent priest.

Hurlbert’s initial assessment of McFadden was of a man with ‘great freedom and fluency … sanguine by temperament, with an expression at once shrewd and enthusiastic, a most flexible persuasive voice.’ McFadden laid the blame for the problems in Gweedore and neighbouring Falcarragh (where the troubled estate of Wybrants Olphert was located and where the protective RIC complement had been raised from six to forty) not at the door of the landlords, but at their agents. Because, the priest observed, the land agents were paid by commission based on the amount of rental money actually collected, ‘the more they can screw either out of the soil, or out of any other resources of the tenants, the better it is for them’.

In the course of their conversation, McFadden made one startling concession to Hurlbert. He acknowledged that, even if the tenants themselves owned the land they were working, not all of them would be able to live off their holdings. The admission, of itself, was hardly more than a pragmatic assessment of the economics of subsistence farming in Donegal from a man rooted in reality. The surprising element is that he would have been so candid with a visiting correspondent such as Hurlbert. Clearly the latter had not tipped his hand to the priest, who would also have been aware that much of the income earned in the remoter parts of Donegal did not come from subsistence farming but from the fruits of seasonal migration.

McFadden did, however, offer a solution to the conundrum. Government investment in land reclamation, he claimed, would enable more tenants to make a decent living from their holdings. ‘The district could be improved’, he continued, ‘by creating employment on the spot, establishing factories, developing fisheries, giving technical education, and encouraging cottage industries.’ In outlining this plan, McFadden was anticipating the Congested Districts Board, one of the staging posts in the Conservative government’s strategy in the 1890s of ‘killing Home Rule with kindness’ – creating a contented peasantry (while still maintaining landlord supremacy) that would forswear grievance politics and abandon the cause of legislative independence in favour of enjoying and augmenting their newly acquired creature comforts. (Spoiler alert – it didn’t work.)

As the conversation wound down, Hurlbert tackled McFadden on what he may have perceived as the cleric’s weak spot: the issue of a priest encouraging his flock to ignore the moral responsibility to pay their rent. McFadden, who must have anticipated the question, had his response well-prepared: ‘If a man can pay a fair year’s rent out of the produce of his holding, he is bound to pay it. But if the rent be a rack-rent, imposed on the tenant against his will, or if the holding does not produce the rent, then I don’t think that is a strict obligation in conscience’.

In the case of Gweedore, McFadden was, essentially, making the point that a tenant should not be obliged to subsidise his own rent from income derived while working as a farm labourer in Scotland or elsewhere. Hurlbert demurred, citing the United States as his precedent, and noting that: ‘If a tenant there cannot pay his first quarter’s rent (they don’t let him darken his soul by a year’s liabilities) they promptly and mercilessly put him out’.[10]

The interview at an end, Hurlbert rose to go, but before his departure he was offered ‘a glass of the excellent wine of the country’. Since nineteenth century Irish viticulture was sparse, this might well be taken as a sly reference to the local poitín (poteen). However, McFadden was as much of a thorn in the side of the local illicit distillers as he was of landlords, having waged a dogged campaign against local poteen-makers. Interestingly, the priest declined to join his guest in his own hospitality, pleading that he was ‘almost a teetotaller’. Hurlbert was later advised that it was Captain Hill’s refusal of a similar offer of hospitality that sparked the quarrel with McFadden. This was a classic example of Irish reductionism. There was rather more at issue between priest and landlord than a glass of contraband ‘uiscebaugh’.

Ballyconnell House, Falcarragh, Co. Donegal

Hurlbert’s next host was Wybrants Olphert of Ballyconnell House in nearby Falcarragh. This was an altogether different experience for the American journalist. Before he sat down to lunch with the Falcarragh landlord, Hurlbert noticed the man’s son enter the house and toss a revolver on the hall table, prompting the American to make comparisons with the ‘Wild West’. While McFadden had blamed the landlords’ agents (Hewson and Dopping) for the local unrest, Olphert did not reciprocate the courtesy. He held McFadden, and the Falcarragh curate, Father Daniel Stephens, largely responsible, along with his younger tenants, for the annoyance being visited upon him. Olphert was especially aggrieved because he had agreed to a 20 per cent reduction in rent and insisted to Hurlbert that there had been no evictions on his estate. That situation would soon change, and with a vengeance. In January 1889 Olphert dug in his heels, and Hewson began a series of ejectments that continued for two years. By December 1890 more than 350 families had been evicted, and only 10 per cent were readmitted to their holdings.[11]

In his account of his conversation with Olphert, Hurlbert introduced a trope to which he often returned over the next 500 pages of Ireland Under Coercion, namely the question of the ability of supposedly immiserated tenants to pay their rent. Hurlbert’s thesis was that Plan tenants were agitators with a political agenda, as opposed to subsistence farmers no longer able to pay even arbitrated rents because of continued agricultural depression. In a series of QED moments throughout the book, he makes reference to the total amounts held in Post Office savings accounts in areas where the Plan was at its most belligerent. The implication was that the very existence of savings accounts indicated a considerable degree of local prosperity and that the money being squirrelled away belonged to tenants who should have been remitting it to their landlords, a somewhat dubious line of logic. Hurlbert also made frequent reference to substantial increases in the level of banked savings in the course of the 1880s.

For example, in the case of Falcarragh he observed that the Olphert tenants ‘are not going down in the world’ because bank deposits that stood at £62.15s in 1880 had risen to £494.11s in 1887.[12] In the second volume of his work he makes a similar argument regarding Sixmilebridge in County Clare, Killorglin in County Kerry, and Gorey in County Wexford.[13] However, he offers no evidence that local tenant farmers were the beneficial owners of the bulk of those savings accounts. Neither does he take into consideration the sums being saved by Plan adherents in rent which were being banked locally by the trustees of the fighting funds. This might well account for at least some of the increases noted between 1880 and 1887.

Hurlbert’s visit to Gweedore and Falcarragh took place in early February 1888. Towards the end of that month, he found himself in County Clare, often accompanied on his travels there by Resident Magistrate Colonel Alfred Turner, who, arguably, had more sympathy for the predicament of Irish tenant farmers than did the American journalist. Arriving on 18 February, after an unexplained side trip to Paris, he put up at the ‘spacious goodly house’ of Edenvale, the Ennis home of local landlord Richard Stacpoole. One of his first observations on walking through the town was the ubiquity of public houses. So impressed was he by the preponderance of drinking establishments that he sought some statistical backup and was told that the town (population 6,307) boasted more than 100 (legal) alehouses. This was by way of a prelude to the announcement that 23 of the 36 publicans of Milltown Malbay had been tried at Ennis assizes for boycotting the RIC. One charge was dismissed, one publican was acquitted, ten (‘the most prosperous’) signed a guarantee in court ‘not to further conspire’, while the remainder were despatched to prison to serve a month’s hard labour.

The case allowed Hurlbert to introduce another of the leading protagonists of his narrative, Father Patrick White, parish priest of Milltown Malbay, who, we are told, admitted in open court to being ‘the moving spirit of all this local boycott’. White had persuaded the other merchants of Milltown Malbay to close their premises—to make the village ‘as a city of the dead’—while the case was being conducted in Ennis. After the eleven non-penitent publicans were conducted to jail, White had gone to the home of each to offer support to their families. Mistakenly, however, he had entered the house of one of the ten signatories of the guarantee to be of good behaviour. When he realised his error, according to Hurlbert, he had quickly emerged from the traitorous premises ‘using rather unclerical language’. Hurlbert then tut-tutted that, although this was a ‘tempest in a tea-pot … it is a serious matter to see a priest of the Church assisting laymen to put their fellow men under a social interdict’.

When Hurlbert asked an RIC sergeant about the likely fate of the recanting publicans he got an interesting primer in rural economics. He was told that, although there had been suggestions that the erstwhile boycotting bar-owners would, in their turn, be ostracised by the local ‘butchers and bakers … it’s all nonsense, they are the snuggest publicans in this part of the country, and nobody will want to vex them … the best friend they have is that they can afford to give credit to the country people’.

By way of illustration of his perennial argument that many Plan tenants desperately wanted to come to terms with their landlords, Hurlbert repeated an anecdote that he had picked up from Stacpoole about a ‘good’ tenant who came to the landlord to tell him that he dare not pay his rent. When Stacpoole challenged the man, accusing him of rank cowardice: ‘The man turned rather red, went and looked out of all the windows, one after another, lifted up the heavy cloth of the large table in the room and peeped under it nervously, and finally walked up to Mr. Stacpoole and paid the money’.

In the second volume of Ireland Under Coercion Hurlbert includes Father White among ‘a certain class of the Irish clergy [associated] with the most violent henchmen of the League’ and also implies that such clerics ‘regard the assassination of “bailiffs and tax-collectors” as a pardonable, if not positively amusing, excess of patriotic zeal’.[14]

White considered suing Hurlbert for defamation, but was advised against it and contented himself with writing a pamphlet entitled Hurlbert Unmasked: an exposure of the thumping English lies of William Henry Hurlbert in his ‘Ireland Under Coercion’, in which White accused Hurlbert of having ‘libelled me unsparingly’. In addition to accusing Hurlbert of ‘cowardly and contemptible’ tactics in his ‘stream of contempt and scorn … which must have been pleasant reading, indeed, for all unionists’, White offered his justification for a Christian minister supporting the palpably un-Christian act of boycotting. Validation of his approval of the practice is summed up in his observation that ‘Desperate diseases require desperate remedies’.[15] White also retaliated by drawing attention to the number of ‘anonymous informants’ in Hurlbert’s work. These included such political insiders as a jarvey with a ‘knowing look’, a ‘sarcastic nationalist’ and a ‘shrewd Galway man’. The priest questioned their credentials and, by implication, their very existence.[16] Hurlbert, however, had anticipated some level of scepticism when it came to his protection of confidential sources and used the guarding of their identities as ammunition. He had been urgently requested, he footnoted, by an anonymous ‘friend’, who had introduced him to a number of farm labourers, to expunge their names from the manuscript of the book. This had been done at great inconvenience after the relevant chapter had gone to press. Hurlbert observed of this request: ‘What can be said for the freedom of a country in which a man of character and position honestly believes it to be “dangerous” for poor men to say the things recorded in the text of this chapter about their own feelings, wishes, opinions, and interests?’[17]

There is a bitter irony associated with Hurlbert’s later life. Having, or so it would appear, come to Ireland on a mission to discredit the supporters of Charles Stewart Parnell, he was to suffer a similar fate to that of the Irish parliamentarian. His involvement in a scandalous court case in 1891, in which evidence of an adulterous affair was introduced, left his reputation in tatters. He died, at the age of sixty-eight, in exile in Italy, far from the city of New York where, until relinquishing the editor’s spike on the World newspaper, he had been a major force.

His partisan desire to see Irish landlordism endure was not, even in the medium term, to be granted. Within fifteen years of the publication of Ireland Under Coercion, even the Tories made it clear—with the land purchase legislation introduced by chief secretary George Wyndham in 1903—that they no longer saw any agreeable future in the tea leaves for the Irish landed class.

Was Ireland Under Coercion the legacy of a journalistic spent force seeking redemption and relevance, or the observations of a cold-eyed truth-teller made without fear or favour? That verdict really depended on which side of the nationalist/unionist or tenant/landlord divide you happened to find yourself when the two-volume memoir was published in 1888.

[1] Michael Davitt, The Times Parnell Commission speech delivered by Michael Davitt in defence of the Land League (London, 1890), 152.

[2] William Henry Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion: The Diary of an American (London, 1888) Vol. 1, xxxvi.

[3] Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion, vol. 1, lvii.

[4] United Ireland, 22 August, 1888.

[5] The Times, 18 August, 1888.

[6] Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion, vol. 1, 15.

[7] James McFadden The Present and the Past of the Agrarian Struggle in Gweedore (Derry, 1889), 18.

[8] McFadden, Agrarian Struggle in Gweedore, 85.

[9] Derry Journal, 14 September 1887.

[10] Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion, vol. 1, 91-103.

[11] L.Perry Curtis Jr., ‘Three Oxford Liberals and the Plan of Campaign in Donegal, 1889’, History Ireland, May/June 2011, Volume 19.

[12] Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion, vol. 1, 117.

[13] Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion, vol 2, 5, 12, 248.

[14] Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion, Vol.2, 86.

[15] Patrick White, Hurlbert Unmasked: an exposure of the thumping English lies of William Henry Hurlbert in his ‘Ireland Under Coercion’ (New York, 1890), 18.

[16] White, Hurlbert Unmasked, 24-28.

[17] Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion, Vol.ii, 249.

October 15, 2024

Wodehouse’s War – Prisoner #796 and the Berlin broadcasts

Pelham Grenville Wodehouse was born 143 years ago on 15 October 1881. He died at the age of 93, in the USA, fifty years ago, next year. The Hinterland Festival in Kells will be celebrating his work in 2025 with a number of events and in this blog I want to anticipate that commemoration by looking at one of the most difficult periods of his life, his incarceration by the Nazis during World War 2 and the subsequent furore over his five anodyne but controversial broadcasts to the USA and Britain from a Berlin radio studio in July/August 1941.

While Wodehouse has attracted a number of accomplished biographers (Joseph Connolly, Frances Donaldson, Robert McCrum, Barry Phelps, David A. Jasen et al ) The most comprehensive work on the events of 1940/41 is Wodehouse’s War by Iain Sproat. Sproat also contributed the author’s biography to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

In 1934 Wodehouse and his wife Ethel purchased a villa in the French coastal resort of Le Touquet, not far from Boulougne. The German blitzkrieg that led to the rapid fall of France in 1940 took not only the Wodehouse’s by surprise, but the British and French authorities as well. The Wodehouses, contrary to some contemporary narratives, made two attempts to get back to Britain but were dogged by ill luck when, first their car, and then a truck, both broke down within a short distance of their villa. They had no option but to remain in Le Touquet and await the arrival of the Germans.

On 22 May 1940 the Germans occupied Le Touquet. As a British non-combatant citizen Wodehouse was required to report at 9:00 a.m. each day to the German authorities in the nearby town of Paris Plage. On 21 July Wodehouse was informed that, because he had not yet reached the age of 60 (he was almost 59) he was to be committed to an internment camp. He was taken to a prison in a suburb of the French city of Lille, about 70 miles from Le Touquet. Within a week Wodehouse and 44 others were brought to a nearby railway station. They and c.800 other male internees were then transported by cattle truck to Liège in Belgium, a journey of 19 hours. On the 3 August 1940 Wodehouse, along with other internees, was packed into one of a number of cattle trucks (50 men to each truck) and sent to a medieval stone fortress called the Citadel in the town of Huy. He was kept there for six weeks in vile conditions, with inadequate food rations, sleeping on straw on a stone floor, before the internees were again moved to a former lunatic asylum in the village of Tost in Upper Silesia. Although this final destination, where he remained until the summer of 1941, might sound grim, it was an improvement on the temporary accommodation afforded the internees since July 1940. The regime in Tost was relatively mild, and Wodehouse, because he was nearing 60, was not required to perform manual labour, such as hauling coal or clearing the roads of snow. The inmates of Tost were allowed to stage concerts and even cricket matches. In late December 1940 the camp was visited by an Associated Press reporter, Angus Thuermer, who interviewed Wodehouse. It was the first news of the writer in almost six months. Thuermer’s article emphasised that, although Wodehouse had been offered preferential treatment by the Germans, he had steadfastly refused this.

When Thuermer’s article was published, a concerted campaign began in the, still-neutral, USA to secure Wodehouse’s release and his return to America. Wodehouse also began to receive dozens of letters from American fans wishing him well.

A few months before his 60th birthday, on the 21st of June 1941, Wodehouse was released from Tost, sent to Berlin, and at the behest of the German authorities, housed in the Hotel Adlon in the city. There he was joined by Ethel, who had remained in France during Wodehouse’s period of internment. The Wodehouses were then accommodated in a number of locations around Germany. This included some stays in Berlin. On the 9th of September 1943 Wodehouse and Ethel were permitted to return to France, where they lodged at the Hotel Bristol in Paris. There they remained until the city was liberated by the allies on the 25th of August 1944.

While living in Berln, shortly after his release from Tost, Wodehouse did a radio interview with the CBS correspondent Harry Flannery. This was scripted in advance, and, retrospectively, would add to Wodehouse’s grief when the controversy over his subsequent actions blew up. It appears that, after this interview was broadcast, Wodehouse had a conversation with a former Hollywood associate of his, Werner Plack, a returned German actor who worked for the Foreign Ministry. Plack, who obviously had his own agenda, suggested that Wodehouse should do a number of short-wave radio broadcasts to the USA, describing his experiences as an internee. Crucially, as far as Wodehouse was concerned, these would not be censored. He recorded the five broadcasts between the 25th of June and the 26th of July 1941. Wodehouse was determined, in writing the scripts, not to understate the hardships and the uncertainties of the previous twelve months, but he was also intent on maintaining a ‘stiff upper lip’ and not appearing to whine. His experience had, after all, been far less onerous than that of British prisoners of war or serving soldiers. He may well have erred a little too much on the side of flippancy. However, the pieces were sufficiently subversive and critical of Germany that they were used, in written form, by the US War Department in its Intelligence School at Camp Ritchie, as excellent examples of anti-Nazi propaganda.

However, the content of the five pieces – which amounted to a humorous account of his internment – was of far less importance than the very fact of their existence. Few American listeners ever heard the short-wave transmissions, but the reaction in the UK to the idea of one of their country’s most celebrated writers broadcasting on German radio, varied from the censorious to the apoplectic. All five broadcasts were later beamed to Britain in August 1941, but the reaction had kicked in long before that. The most visceral response to Wodehouse’s decision to record these innocuous pieces (in terms of their content at least) came on the BBC on 15 July 1941 when the Daily Mirror columnist William N. Connor (who wrote under the pseudonym ‘Cassandra’) was allocated ten minutes of air time after the Nine O’Clock News to vent his spleen against Wodehouse. The decision to broadcast Connor’s script was entirely the responsibility of then Minister for Information, Duff Cooper. The BBC Governors, having studied Connor’s script in advance, were opposed to the broadcast. The BBC had monitored the first two Wodehouse pieces and found them to be apolitical and inoffensive. The corporation, however, was overruled by Cooper and because the BBC was obliged to make airtime available to the Ministry of Information, the piece was transmitted to a BBC audience, the vast majority of whom had not heard the original Wodehouse broadcasts. Accordingly, they were guided in their response by Connor’s invective. After the venom of ‘Cassandra’ their assumption could only have been that Wodehouse had been a party to an egregious piece of pro-Nazi propaganda.

Connor’s script included the following diatribe, much of which was inaccurate and potentially defamatory.

‘When the war broke out Pelham Grenville Wodehouse was at Le Touquet – gambling. Nine months later he was still there. Poland had been wiped out. Denmark had been overrun and Norway had been occupied. Wodehouse still went on with his fun. The elderly playboy didn’t believe in politics. He said so. No good time Charlie ever does. Wodehouse was throwing a cocktail party when the storm troopers clumped in on his shallow life. They led him away – the funny Englishman with his vast repertoire of droll butlers, amusing young men and comic titled fops. Politics, in the form of the Nazi eagle, came home to roost. Bertie Wooster faded and Dr. Goebbels hobbled on the scene. He treated his prisoner gently. Wodehouse was stealthily groomed for stardom. The most disreputable stardom in the world – the limelight of quislings. On the last day of June of this year, Doctor Goebbels was ready. So too was Pelham Wodehouse. He was eager and he was willing, and when they offered him liberty in a country that has killed liberty, he leapt at it. And Doctor Goebbels taking him to a high mountain, showed unto him all the kingdoms of the world, and said unto him: “all this power will I give thee if thou wilt worship the Führer.” Pelham Wodehouse fell on his knees. Perhaps you have heard this man’s voice reaching out to you from his luxury suite on the third floor of the Adlon hotel in Berlin. Maybe you can forgive him. Some of us can neither forgive nor forget. 50,000 of our countrymen are enslaved in Germany. How many of them are in the Adlon hotel tonight? Barbed wire is their pillow. They endure – but they do not give in. They suffer – but they do not sell out. Between the terrible choice of betrayal of one’s country and the abominations of the Gestapo, they have only one answer. The jails of Germany are crammed with men who have chosen without demur. But they have something that Wodehouse can never regain. Something that 30 pieces of silver could never buy.’

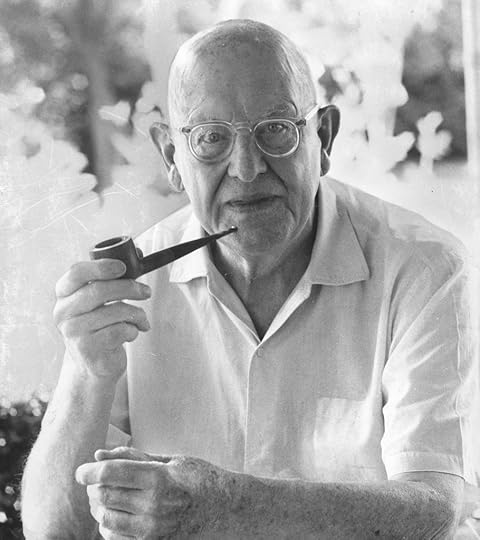

William N. Connor – ‘Cassandra’

In the House of Commons the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, criticised Wodehouse, observing that the writer had ‘lent his services to the Nazi war propaganda machine’. Quintin Hogg, the senior Tory MP (later Lord Hailsham) compared Wodehouse to William Joyce, the infamous ‘Lord Haw Haw’, the Irish-American fascist and nightly purveyor of Nazi propaganda and morale-sapping lies from Germany’s English language radio service. ‘While he was clowning,’ Hogg railed to the House of Commons, ‘British boys were resisting the Germans, and there can be nothing but contempt for the action of a man who, in order to live in a hotel more comfortably than his fellow prisoners, did that kind of thing against his country.’ Some MPs, and many more members of the public, wanted Wodehouse to be tried for treason.

The Cassandra broadcast and the Commons statements engendered a wave of hysterical anger against Wodehouse among a British public, the vast majority of whom had not heard the broadcasts or even read a transcription of them. Some British libraries banned his books. Despite the initial opposition of the BBC to the ‘Cassandra’ broadcast (one of the governors had even approached Winston Churchill, asking him to overrule Duff Cooper— he declined) the corporation was later to become embroiled in the anti- Wodehouse hysteria. In December 1943, when a head of steam had been built up against Wodehouse, the BBC banned the broadcast of his works, even of songs with lyrics written by him. Not until 1950 was his work reinstated, with a transmission on the Light Programme. However, the fact that Wodehouse’s works sold three million copies in Britain between the summer of 1941 and the end of the war, suggests that not everyone in the UK wanted him to face a firing squad and were prepared to reserve judgement until they had heard from the man himself.

The Times and the Daily Telegraph devoted much space in their letters pages to a discussion of Wodehouse’s obvious faux pas and of Connor’s BBC broadcast. The great and the good became embroiled in the controversy. The humorist and novelist Edmund Clerihew Bentley (Trent’s Last Case), in a letter to the Telegraph, was one of the least forgiving. He called for the rescinding by the University of Oxford of the Doctorate granted to Wodehouse in 1939, an honour bestowed, observed Bentley cattily, ‘upon one who has never written a serious line’. ‘Amends can be made, however,’ he continued. ‘Those who awarded the honour can take the earliest opportunity of removing it. That action would have a certain effectiveness, not only as a mark of disapproval but as a sign of repentance; and most of my fellow graduates, I believe, would heartily welcome it on both grounds.’

Edmund Clerihew Bentley

Wodehouse’s erstwhile friend A.A. Milne, a World War 1 veteran, was more ambiguous in his letter to the Telegraph, but hardly more supportive …

‘He has encouraged in himself a natural lack of interest in ‘politics’ – ‘politics’ being all the things which the grown-ups talk about at dinner when one is hiding under the table. Things for instance, like the last war, which found and kept him in America … Irresponsibility in what the papers call ‘a licensed humorist’ can be carried too far, naivety can be carried too far. Wodehouse has been given a good deal of licence in the past, but I fancy that now his licence will be withdrawn. Before this happens I beg him to surrender it of his own free will; to realise that though a genius may grant himself an enviable position about the battle where civic and social responsibilities are concerned, there are times when every man has to come down into the arena, pledge himself to the cause in which he believes, and suffer for it.’

The creator of Winnie the Pooh was being less than fair in relation to Wodehouse’s World War 1 record. In 1914, aged 32, (although resident in USA) Wodehouse had tried to enlist in the Royal Navy but had been rejected on medical grounds. In 1917, when the USA entered the war, Wodehouse volunteered at a newly established recruiting office for ex-pat British citizens but was again rejected on medical grounds.

The crime novelist Dorothy L. Sayers wrote a rather more understanding letter to the Telegraph. British people, she pointed out, had learned much more since 1940 of the depravity of the Nazi regime, than Wodehouse would have been aware of at the time of his internment. ‘But how much of all this can possibly be known or appreciated from inside a German concentration camp – or even from the Adlon hotel? Theoretically, no doubt, every patriotic person should be prepared to resist enemy pressure to the point of martyrdom; but it must be far more difficult to bear such heroic witness when its urgent necessity is not, and cannot be, understood.’

Dorothy L. Sayers

Playwright Sean O’Casey, in his letter to the Telegraph took a more literary and aesthetic approach and, in the process, coined a memorable appellation for Wodehouse. ‘The harm done to England’s cause,’ O’Casey wrote, ‘and to England’s dignity is not the poor man’s babble in Berlin, but the acceptance of him by a childish part of the people and the academic government of Oxford, dead from the chin up, as a person of any importance whatsoever in English humorous literature, or any literature at all. It is an ironic twist of retribution on those who banished Joyce and honoured Wodehouse. If England has any dignity left in the way of literature, she will forget forever the pitiful antics of English literature’s performing flea (my italics). If Berlin thinks the poor fish great, so much the better for us.’

The letters page of the Times was more focussed on the Cassandra BBC rant of 15 July 1941 than on the original broadcasts on which the diatribe was based. In a letter to the ‘newspaper of record’ Duff Cooper took full responsibility for the William Connor broadcast. The Information Minister acknowledged that, ‘the governors indeed shared unanimously the view expressed in your columns that the broadcast in question was in execrable taste … occasions, however, may arise in time of war when plain speaking is more desirable than good taste.’

Connor himself doubled down on his BBC broadcast. He responded in the Times to accusations that he had defamed and misrepresented Wodehouse, or, at best, that he had been guilty of ‘bad taste’.

‘Since when,’ Connor wrote, ‘has it been bad taste to name and nail a traitor to England? The letters which you have published have only served as a sad demonstration that there is still in this country a section of the community eager and willing to defend its own quislings.’ Connor claimed that 90% of letters to his own newspaper, the Mirror agreed with the sentiments he had expressed in the 15 July BBC broadcast (at which point, it should be re-iterated, the five essays had not even been re-broadcast to Britain). He claimed that Mirror readers were more representative of the British population than those of the Times. He deprecated the ‘storm of protest’ which he claimed the Times had ‘so diligently fanned.’

Connor then took a further swipe at the Times by bringing up its record on pre-war appeasement of Hitler, asserting that the pro-Wodehouse ‘storm of protest’ …

‘…compares favourably with the flat calm of acquiescence which was such a prominent feature of your correspondence before and up to the year of Munich. I learn with interest that the governors of the BBC share your views of what you describe as a ‘notorious’ broadcast. However, I accurately anticipated their reaction and it is to the credit of Mr. Duff Cooper that he insisted beforehand that the BBC should have no say whatsoever in the script of this talk. It would certainly not have been possible for him to have adopted this point of view, had it not been that their lamentable governorship had rendered matters of propaganda demonstrably outside their scope. To the accusation that this broadcast was vulgar, I would remind you that this is a vulgar war, in which our countrymen are being killed by the enemy without regard to good form or bad taste. When Dr. Goebbels announces an apparently new and willing propaganda recruit to further this slaughter, I still retain the right to denounce this treachery in terms compatible with my own conscience – and nothing else.’

After the war Connor changed his mind about Wodehouse’s culpability and was gracious enough to apologise to the author for the BBC broadcast. Duff Cooper, however, although a fan of Wodehouse’s writing, did not apologise for allowing the ‘Cassandra’ broadcast to go ahead. His main concern at the time was that the five ‘Berlin’ essays were being transmitted to a USA where the spirit of isolationism was rampant, until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941 brought America into the war.

It was some while after the ‘Berlin’ broadcasts before Wodehouse became aware of the adverse reaction in Britain. In a letter to the British Foreign Office on 21 November 1942 he attempted to set the record straight. He referred to ‘my unfortunate broadcasts’ and tried to demonstrate that ‘I was guilty of nothing more than a blunder’. He denied that the five recorded essays had been a quid pro quo for his release (something that was widely believed at the time) maintaining that this had come about because he was sixty years of age and was in line with German policy towards foreign internees. This was something of a white lie as he was released from Tost four months before his 60th birthday. He went on to claim that the rationale behind the radio essays was to respond to the hundreds of good wishes he had been receiving from American readers and supporters while interned. He claimed to have written the five pieces while incarcerated in Tost and to have read them to his fellow prisoners, ‘who were amused by them, which would not have been the case had they contained the slightest suggestion of German propaganda.’ Wodehouse also denied that he was ‘being maintained by the German government’ (another prevailing perception among the wider British public). He was, he insisted, supporting himself in Germany with borrowed money and with the proceeds of the sale of his wife’s jewellery. ‘All of this I realise,’ he concluded, ‘does not condone the fact that I used the German shortwave system as a means of communication with my American public, but I hope that it puts my conduct in a better light … I should like to conclude by expressing my sincere regret that a well meant but ill-considered action on my part should have given the impression that I am anything but a loyal subject of His Majesty.’

The liberation of Paris in August 1944 provided Wodehouse with his first opportunity to explain himself directly to British officials. Wodehouse’s case was fully investigated, while the war continued, to see if either his behaviour or his broadcasts merited treason charges, similar to those that would be brought in 1945 against William Joyce at the end of the conflict. A British Intelligence Corps officer, Major E.J.P. Cussen began an enquiry into Wodehouse’s wartime activities shortly after the liberation of Paris. Examining allegations that Wodehouse had, for example, made no effort to flee Le Touquet in advance of the arrival of the Germans; had collaborated with the Germans in Le Touquet by welcoming them to his villa; had sought and obtained favours from his captors while in captivity; and had offered his services to the Germans in exchange for a measure of personal freedom for himself and his wife Ethel, Cussen conducted a number of interviews with British ‘ex-pat’ residents of Le Touquet in the 1930s and 40s. He also studied German files discovered in Paris where the Wodehouses had spent most of the year prior to the liberation of the city in August 1944. In relation to the charges unrelated to his Berlin broadcasts (failure to evacuate, collaboration etc) Cussen found no supportive evidence. Wodehouse had made two failed attempts to flee Le Touquet and, like the British military authorities, had been caught unawares by the speed of the German advance. He had not fraternised or collaborated with the Germans in his Le Touquet villa, in fact his bathroom had been commandeered for the use of German soldiers. He had not sought favours from his German captors (there was substantial evidence, in the form of the Thuermer interview, that he had been offered preferential treatment but had turned it down).

His potential treason came down to the issue of the five Berlin broadcasts. Did they amount to Nazi propaganda? There was no denying that Wodehouse had recorded the broadcasts and that they were, at the very least, unwise, naïve and even reprehensible. But were they overt Nazi propaganda knowingly designed to undermine the morale of British listeners? Were they critical of British policy, or of the British war effort?

In fact the broadcasts were entirely apolitical and, if anything, subtly antagonistic towards his German ‘hosts’.

In his first essay, for example, Wodehouse wrote …