Wodehouse’s War – Prisoner #796 and the Berlin broadcasts

Pelham Grenville Wodehouse was born 143 years ago on 15 October 1881. He died at the age of 93, in the USA, fifty years ago, next year. The Hinterland Festival in Kells will be celebrating his work in 2025 with a number of events and in this blog I want to anticipate that commemoration by looking at one of the most difficult periods of his life, his incarceration by the Nazis during World War 2 and the subsequent furore over his five anodyne but controversial broadcasts to the USA and Britain from a Berlin radio studio in July/August 1941.

While Wodehouse has attracted a number of accomplished biographers (Joseph Connolly, Frances Donaldson, Robert McCrum, Barry Phelps, David A. Jasen et al ) The most comprehensive work on the events of 1940/41 is Wodehouse’s War by Iain Sproat. Sproat also contributed the author’s biography to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

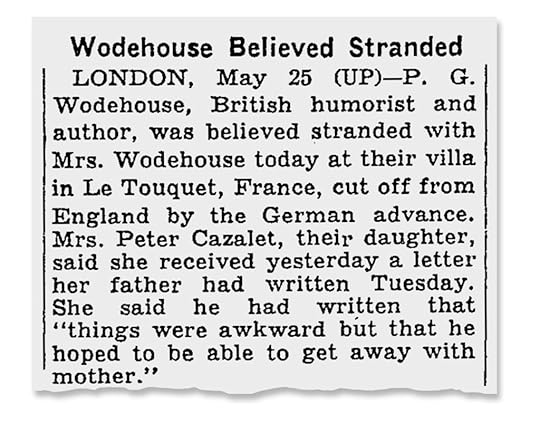

In 1934 Wodehouse and his wife Ethel purchased a villa in the French coastal resort of Le Touquet, not far from Boulougne. The German blitzkrieg that led to the rapid fall of France in 1940 took not only the Wodehouse’s by surprise, but the British and French authorities as well. The Wodehouses, contrary to some contemporary narratives, made two attempts to get back to Britain but were dogged by ill luck when, first their car, and then a truck, both broke down within a short distance of their villa. They had no option but to remain in Le Touquet and await the arrival of the Germans.

On 22 May 1940 the Germans occupied Le Touquet. As a British non-combatant citizen Wodehouse was required to report at 9:00 a.m. each day to the German authorities in the nearby town of Paris Plage. On 21 July Wodehouse was informed that, because he had not yet reached the age of 60 (he was almost 59) he was to be committed to an internment camp. He was taken to a prison in a suburb of the French city of Lille, about 70 miles from Le Touquet. Within a week Wodehouse and 44 others were brought to a nearby railway station. They and c.800 other male internees were then transported by cattle truck to Liège in Belgium, a journey of 19 hours. On the 3 August 1940 Wodehouse, along with other internees, was packed into one of a number of cattle trucks (50 men to each truck) and sent to a medieval stone fortress called the Citadel in the town of Huy. He was kept there for six weeks in vile conditions, with inadequate food rations, sleeping on straw on a stone floor, before the internees were again moved to a former lunatic asylum in the village of Tost in Upper Silesia. Although this final destination, where he remained until the summer of 1941, might sound grim, it was an improvement on the temporary accommodation afforded the internees since July 1940. The regime in Tost was relatively mild, and Wodehouse, because he was nearing 60, was not required to perform manual labour, such as hauling coal or clearing the roads of snow. The inmates of Tost were allowed to stage concerts and even cricket matches. In late December 1940 the camp was visited by an Associated Press reporter, Angus Thuermer, who interviewed Wodehouse. It was the first news of the writer in almost six months. Thuermer’s article emphasised that, although Wodehouse had been offered preferential treatment by the Germans, he had steadfastly refused this.

When Thuermer’s article was published, a concerted campaign began in the, still-neutral, USA to secure Wodehouse’s release and his return to America. Wodehouse also began to receive dozens of letters from American fans wishing him well.

A few months before his 60th birthday, on the 21st of June 1941, Wodehouse was released from Tost, sent to Berlin, and at the behest of the German authorities, housed in the Hotel Adlon in the city. There he was joined by Ethel, who had remained in France during Wodehouse’s period of internment. The Wodehouses were then accommodated in a number of locations around Germany. This included some stays in Berlin. On the 9th of September 1943 Wodehouse and Ethel were permitted to return to France, where they lodged at the Hotel Bristol in Paris. There they remained until the city was liberated by the allies on the 25th of August 1944.

While living in Berln, shortly after his release from Tost, Wodehouse did a radio interview with the CBS correspondent Harry Flannery. This was scripted in advance, and, retrospectively, would add to Wodehouse’s grief when the controversy over his subsequent actions blew up. It appears that, after this interview was broadcast, Wodehouse had a conversation with a former Hollywood associate of his, Werner Plack, a returned German actor who worked for the Foreign Ministry. Plack, who obviously had his own agenda, suggested that Wodehouse should do a number of short-wave radio broadcasts to the USA, describing his experiences as an internee. Crucially, as far as Wodehouse was concerned, these would not be censored. He recorded the five broadcasts between the 25th of June and the 26th of July 1941. Wodehouse was determined, in writing the scripts, not to understate the hardships and the uncertainties of the previous twelve months, but he was also intent on maintaining a ‘stiff upper lip’ and not appearing to whine. His experience had, after all, been far less onerous than that of British prisoners of war or serving soldiers. He may well have erred a little too much on the side of flippancy. However, the pieces were sufficiently subversive and critical of Germany that they were used, in written form, by the US War Department in its Intelligence School at Camp Ritchie, as excellent examples of anti-Nazi propaganda.

However, the content of the five pieces – which amounted to a humorous account of his internment – was of far less importance than the very fact of their existence. Few American listeners ever heard the short-wave transmissions, but the reaction in the UK to the idea of one of their country’s most celebrated writers broadcasting on German radio, varied from the censorious to the apoplectic. All five broadcasts were later beamed to Britain in August 1941, but the reaction had kicked in long before that. The most visceral response to Wodehouse’s decision to record these innocuous pieces (in terms of their content at least) came on the BBC on 15 July 1941 when the Daily Mirror columnist William N. Connor (who wrote under the pseudonym ‘Cassandra’) was allocated ten minutes of air time after the Nine O’Clock News to vent his spleen against Wodehouse. The decision to broadcast Connor’s script was entirely the responsibility of then Minister for Information, Duff Cooper. The BBC Governors, having studied Connor’s script in advance, were opposed to the broadcast. The BBC had monitored the first two Wodehouse pieces and found them to be apolitical and inoffensive. The corporation, however, was overruled by Cooper and because the BBC was obliged to make airtime available to the Ministry of Information, the piece was transmitted to a BBC audience, the vast majority of whom had not heard the original Wodehouse broadcasts. Accordingly, they were guided in their response by Connor’s invective. After the venom of ‘Cassandra’ their assumption could only have been that Wodehouse had been a party to an egregious piece of pro-Nazi propaganda.

Connor’s script included the following diatribe, much of which was inaccurate and potentially defamatory.

‘When the war broke out Pelham Grenville Wodehouse was at Le Touquet – gambling. Nine months later he was still there. Poland had been wiped out. Denmark had been overrun and Norway had been occupied. Wodehouse still went on with his fun. The elderly playboy didn’t believe in politics. He said so. No good time Charlie ever does. Wodehouse was throwing a cocktail party when the storm troopers clumped in on his shallow life. They led him away – the funny Englishman with his vast repertoire of droll butlers, amusing young men and comic titled fops. Politics, in the form of the Nazi eagle, came home to roost. Bertie Wooster faded and Dr. Goebbels hobbled on the scene. He treated his prisoner gently. Wodehouse was stealthily groomed for stardom. The most disreputable stardom in the world – the limelight of quislings. On the last day of June of this year, Doctor Goebbels was ready. So too was Pelham Wodehouse. He was eager and he was willing, and when they offered him liberty in a country that has killed liberty, he leapt at it. And Doctor Goebbels taking him to a high mountain, showed unto him all the kingdoms of the world, and said unto him: “all this power will I give thee if thou wilt worship the Führer.” Pelham Wodehouse fell on his knees. Perhaps you have heard this man’s voice reaching out to you from his luxury suite on the third floor of the Adlon hotel in Berlin. Maybe you can forgive him. Some of us can neither forgive nor forget. 50,000 of our countrymen are enslaved in Germany. How many of them are in the Adlon hotel tonight? Barbed wire is their pillow. They endure – but they do not give in. They suffer – but they do not sell out. Between the terrible choice of betrayal of one’s country and the abominations of the Gestapo, they have only one answer. The jails of Germany are crammed with men who have chosen without demur. But they have something that Wodehouse can never regain. Something that 30 pieces of silver could never buy.’

William N. Connor – ‘Cassandra’

In the House of Commons the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, criticised Wodehouse, observing that the writer had ‘lent his services to the Nazi war propaganda machine’. Quintin Hogg, the senior Tory MP (later Lord Hailsham) compared Wodehouse to William Joyce, the infamous ‘Lord Haw Haw’, the Irish-American fascist and nightly purveyor of Nazi propaganda and morale-sapping lies from Germany’s English language radio service. ‘While he was clowning,’ Hogg railed to the House of Commons, ‘British boys were resisting the Germans, and there can be nothing but contempt for the action of a man who, in order to live in a hotel more comfortably than his fellow prisoners, did that kind of thing against his country.’ Some MPs, and many more members of the public, wanted Wodehouse to be tried for treason.

The Cassandra broadcast and the Commons statements engendered a wave of hysterical anger against Wodehouse among a British public, the vast majority of whom had not heard the broadcasts or even read a transcription of them. Some British libraries banned his books. Despite the initial opposition of the BBC to the ‘Cassandra’ broadcast (one of the governors had even approached Winston Churchill, asking him to overrule Duff Cooper— he declined) the corporation was later to become embroiled in the anti- Wodehouse hysteria. In December 1943, when a head of steam had been built up against Wodehouse, the BBC banned the broadcast of his works, even of songs with lyrics written by him. Not until 1950 was his work reinstated, with a transmission on the Light Programme. However, the fact that Wodehouse’s works sold three million copies in Britain between the summer of 1941 and the end of the war, suggests that not everyone in the UK wanted him to face a firing squad and were prepared to reserve judgement until they had heard from the man himself.

The Times and the Daily Telegraph devoted much space in their letters pages to a discussion of Wodehouse’s obvious faux pas and of Connor’s BBC broadcast. The great and the good became embroiled in the controversy. The humorist and novelist Edmund Clerihew Bentley (Trent’s Last Case), in a letter to the Telegraph, was one of the least forgiving. He called for the rescinding by the University of Oxford of the Doctorate granted to Wodehouse in 1939, an honour bestowed, observed Bentley cattily, ‘upon one who has never written a serious line’. ‘Amends can be made, however,’ he continued. ‘Those who awarded the honour can take the earliest opportunity of removing it. That action would have a certain effectiveness, not only as a mark of disapproval but as a sign of repentance; and most of my fellow graduates, I believe, would heartily welcome it on both grounds.’

Edmund Clerihew Bentley

Wodehouse’s erstwhile friend A.A. Milne, a World War 1 veteran, was more ambiguous in his letter to the Telegraph, but hardly more supportive …

‘He has encouraged in himself a natural lack of interest in ‘politics’ – ‘politics’ being all the things which the grown-ups talk about at dinner when one is hiding under the table. Things for instance, like the last war, which found and kept him in America … Irresponsibility in what the papers call ‘a licensed humorist’ can be carried too far, naivety can be carried too far. Wodehouse has been given a good deal of licence in the past, but I fancy that now his licence will be withdrawn. Before this happens I beg him to surrender it of his own free will; to realise that though a genius may grant himself an enviable position about the battle where civic and social responsibilities are concerned, there are times when every man has to come down into the arena, pledge himself to the cause in which he believes, and suffer for it.’

The creator of Winnie the Pooh was being less than fair in relation to Wodehouse’s World War 1 record. In 1914, aged 32, (although resident in USA) Wodehouse had tried to enlist in the Royal Navy but had been rejected on medical grounds. In 1917, when the USA entered the war, Wodehouse volunteered at a newly established recruiting office for ex-pat British citizens but was again rejected on medical grounds.

The crime novelist Dorothy L. Sayers wrote a rather more understanding letter to the Telegraph. British people, she pointed out, had learned much more since 1940 of the depravity of the Nazi regime, than Wodehouse would have been aware of at the time of his internment. ‘But how much of all this can possibly be known or appreciated from inside a German concentration camp – or even from the Adlon hotel? Theoretically, no doubt, every patriotic person should be prepared to resist enemy pressure to the point of martyrdom; but it must be far more difficult to bear such heroic witness when its urgent necessity is not, and cannot be, understood.’

Dorothy L. Sayers

Playwright Sean O’Casey, in his letter to the Telegraph took a more literary and aesthetic approach and, in the process, coined a memorable appellation for Wodehouse. ‘The harm done to England’s cause,’ O’Casey wrote, ‘and to England’s dignity is not the poor man’s babble in Berlin, but the acceptance of him by a childish part of the people and the academic government of Oxford, dead from the chin up, as a person of any importance whatsoever in English humorous literature, or any literature at all. It is an ironic twist of retribution on those who banished Joyce and honoured Wodehouse. If England has any dignity left in the way of literature, she will forget forever the pitiful antics of English literature’s performing flea (my italics). If Berlin thinks the poor fish great, so much the better for us.’

The letters page of the Times was more focussed on the Cassandra BBC rant of 15 July 1941 than on the original broadcasts on which the diatribe was based. In a letter to the ‘newspaper of record’ Duff Cooper took full responsibility for the William Connor broadcast. The Information Minister acknowledged that, ‘the governors indeed shared unanimously the view expressed in your columns that the broadcast in question was in execrable taste … occasions, however, may arise in time of war when plain speaking is more desirable than good taste.’

Connor himself doubled down on his BBC broadcast. He responded in the Times to accusations that he had defamed and misrepresented Wodehouse, or, at best, that he had been guilty of ‘bad taste’.

‘Since when,’ Connor wrote, ‘has it been bad taste to name and nail a traitor to England? The letters which you have published have only served as a sad demonstration that there is still in this country a section of the community eager and willing to defend its own quislings.’ Connor claimed that 90% of letters to his own newspaper, the Mirror agreed with the sentiments he had expressed in the 15 July BBC broadcast (at which point, it should be re-iterated, the five essays had not even been re-broadcast to Britain). He claimed that Mirror readers were more representative of the British population than those of the Times. He deprecated the ‘storm of protest’ which he claimed the Times had ‘so diligently fanned.’

Connor then took a further swipe at the Times by bringing up its record on pre-war appeasement of Hitler, asserting that the pro-Wodehouse ‘storm of protest’ …

‘…compares favourably with the flat calm of acquiescence which was such a prominent feature of your correspondence before and up to the year of Munich. I learn with interest that the governors of the BBC share your views of what you describe as a ‘notorious’ broadcast. However, I accurately anticipated their reaction and it is to the credit of Mr. Duff Cooper that he insisted beforehand that the BBC should have no say whatsoever in the script of this talk. It would certainly not have been possible for him to have adopted this point of view, had it not been that their lamentable governorship had rendered matters of propaganda demonstrably outside their scope. To the accusation that this broadcast was vulgar, I would remind you that this is a vulgar war, in which our countrymen are being killed by the enemy without regard to good form or bad taste. When Dr. Goebbels announces an apparently new and willing propaganda recruit to further this slaughter, I still retain the right to denounce this treachery in terms compatible with my own conscience – and nothing else.’

After the war Connor changed his mind about Wodehouse’s culpability and was gracious enough to apologise to the author for the BBC broadcast. Duff Cooper, however, although a fan of Wodehouse’s writing, did not apologise for allowing the ‘Cassandra’ broadcast to go ahead. His main concern at the time was that the five ‘Berlin’ essays were being transmitted to a USA where the spirit of isolationism was rampant, until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941 brought America into the war.

It was some while after the ‘Berlin’ broadcasts before Wodehouse became aware of the adverse reaction in Britain. In a letter to the British Foreign Office on 21 November 1942 he attempted to set the record straight. He referred to ‘my unfortunate broadcasts’ and tried to demonstrate that ‘I was guilty of nothing more than a blunder’. He denied that the five recorded essays had been a quid pro quo for his release (something that was widely believed at the time) maintaining that this had come about because he was sixty years of age and was in line with German policy towards foreign internees. This was something of a white lie as he was released from Tost four months before his 60th birthday. He went on to claim that the rationale behind the radio essays was to respond to the hundreds of good wishes he had been receiving from American readers and supporters while interned. He claimed to have written the five pieces while incarcerated in Tost and to have read them to his fellow prisoners, ‘who were amused by them, which would not have been the case had they contained the slightest suggestion of German propaganda.’ Wodehouse also denied that he was ‘being maintained by the German government’ (another prevailing perception among the wider British public). He was, he insisted, supporting himself in Germany with borrowed money and with the proceeds of the sale of his wife’s jewellery. ‘All of this I realise,’ he concluded, ‘does not condone the fact that I used the German shortwave system as a means of communication with my American public, but I hope that it puts my conduct in a better light … I should like to conclude by expressing my sincere regret that a well meant but ill-considered action on my part should have given the impression that I am anything but a loyal subject of His Majesty.’

The liberation of Paris in August 1944 provided Wodehouse with his first opportunity to explain himself directly to British officials. Wodehouse’s case was fully investigated, while the war continued, to see if either his behaviour or his broadcasts merited treason charges, similar to those that would be brought in 1945 against William Joyce at the end of the conflict. A British Intelligence Corps officer, Major E.J.P. Cussen began an enquiry into Wodehouse’s wartime activities shortly after the liberation of Paris. Examining allegations that Wodehouse had, for example, made no effort to flee Le Touquet in advance of the arrival of the Germans; had collaborated with the Germans in Le Touquet by welcoming them to his villa; had sought and obtained favours from his captors while in captivity; and had offered his services to the Germans in exchange for a measure of personal freedom for himself and his wife Ethel, Cussen conducted a number of interviews with British ‘ex-pat’ residents of Le Touquet in the 1930s and 40s. He also studied German files discovered in Paris where the Wodehouses had spent most of the year prior to the liberation of the city in August 1944. In relation to the charges unrelated to his Berlin broadcasts (failure to evacuate, collaboration etc) Cussen found no supportive evidence. Wodehouse had made two failed attempts to flee Le Touquet and, like the British military authorities, had been caught unawares by the speed of the German advance. He had not fraternised or collaborated with the Germans in his Le Touquet villa, in fact his bathroom had been commandeered for the use of German soldiers. He had not sought favours from his German captors (there was substantial evidence, in the form of the Thuermer interview, that he had been offered preferential treatment but had turned it down).

His potential treason came down to the issue of the five Berlin broadcasts. Did they amount to Nazi propaganda? There was no denying that Wodehouse had recorded the broadcasts and that they were, at the very least, unwise, naïve and even reprehensible. But were they overt Nazi propaganda knowingly designed to undermine the morale of British listeners? Were they critical of British policy, or of the British war effort?

In fact the broadcasts were entirely apolitical and, if anything, subtly antagonistic towards his German ‘hosts’.

In his first essay, for example, Wodehouse wrote …

‘I have just emerged into the outer world after forty-nine weeks of civil internment in a German internment camp and the effects have not entirely worn off. I have not yet quite recovered that perfect mental balance for which in the past I was so admired by one and all … Young men, starting out in life have often asked me how can I become an internee? Well, there are several methods. My own was to buy a villa in Le Touquet on the coast of France and stay there till the Germans came along. This is probably the best and simplest system. You buy the villa, and the Germans do the rest. At the time of their arrival, I would have been just as pleased if they had not rolled up. But they did not see it that way, and on May the 22nd along they came, some on motorcycles, some on foot, but all evidently prepared to spend a long weekend. The proceedings were not marred by any vulgar brawling. All that happened, as far as I was concerned, was that I was strolling on the lawn with my wife one morning, when she lowered her voice and said, ‘Don’t look now but there comes the German army.’ And there they were, a fine body of men, rather prettily dressed in green, carrying machine guns …’

In terms of the content of the five pieces—as opposed to the unpalatable fact that a British subject was broadcasting from Berlin to the USA, and later to Britain—grave exception was taken by many to what they interpreted as the amicable tone of the writing when it came to descriptions of the Germans and Wodehouse’s relationship with them. Little account was taken of the obviously facetious references to the ‘fine body of men, rather prettily dressed in green’. This, and many other allusions, was taken at face value, as is often the case where the humourless reader is concerned.

While the notion that Wodehouse was a Nazi-loving fascist propagandist died a quick death after the war—this after all was the creator of the ridiculous Mosley-lite Roderick Spode, in the Jeeves and Wooster stories, Spode being the leader of the fictional British fascist movement the ‘Black shorts’—the question remained, did Wodehouse trade his celebrity and his craft for preferential treatment by the German government? The answer is almost certainly ‘No’

The entirely fictional fascist Roderick Spode

The fact was that the release of Wodehouse was brokered by the German Foreign Ministry in an effort to impress the USA (that was his friend Werner Plack’s agenda) and because, as he would turn 60 on 15 October 1881, he was due for release anyway from the Silesian internment camp. In addition to the Flannery/CBS radio interview Wodehouse had written an article, while interned, for the Saturday Evening Post magazine entitled ‘My War With Germany’. As it was difficult to obtain transcripts of his five broadcasts, Wodehouse was largely judged on the content of the interview (in which he had made an ill-advised reference to ‘whether Britain wins the war or not’) and the SEP article. To many of his critics neither was sufficiently pugnacious. Wodehouse, ever the self-deprecating humorist, did what was expected of him by his audience in both the interview and the article. He was lighthearted and lacking in the sort of gravitas that might have been more appropriate in the circumstances and could have made his subsequent trial in the ‘court of public opinion’ somewhat less distressing. He was not helped when, post-war, Flannery wrote a book, Assignment to Berlin, about his experiences in Berlin, in which Wodehouse came in for hostile treatment. Flannery wrote that, ‘It was one of the best Nazi publicity stunts of the war, the first with a human angle … Wodehouse was his own Bertie Wooster.’

The Flannery/Wodehouse interview and SEP article included comments such as …

‘I never was interested in politics. I’m quite unable to work up any kind of belligerent feeling. Just as I’m about to feel belligerent about some country I meet a decent sort of chap. We go out together and lose any fighting thoughts or feelings.’

CBS interview.

Harry Flannery

‘A short time ago they had a look at me on parade and got the right idea; at least they sent us to the local lunatic asylum. And I have been there forty-two weeks. There is a good deal to be said for internment. It keeps you out of the saloon and helps you to keep up with your reading. The chief trouble is that it means you are away from home for a long time. When I join my wife I had better take along a letter of introduction to be on the safe side.’

Saturday Evening Post article, ‘My War With Germany’.

‘In the days before the war I had always been modestly proud of being an Englishman, but now that I have been some months resident in this bin or repository of Englishmen [the Tost internment camp] I am not so sure. …The only concession I want from Germany is that she gives me a loaf of bread, tells the gentlemen with muskets at the main gate to look the other way, and leaves the rest to me. In return I am prepared to hand over India, an autographed set of my books, and to reveal the secret process of cooking sliced potatoes on a radiator. This offer holds good till Wednesday week.’

Saturday Evening Post article,‘My War With Germany’.

After the broadcast of the Flannery interview on the CBS network in the USA, Wodehouse was asked by the German Foreign Ministry would he be interested in doing some radio pieces (the declared intention was that they would be for American broadcast only) in the same light-hearted vein. His release, however, was not dependent on his agreement. Where Wodehouse came unstuck was in the fact that there was an ongoing rivalry between Goebbels’s Ministry of Propaganda and the German Foreign Ministry of von Ribbentrop. When the Propaganda Ministry became aware of the adverse reaction to the broadcasts in Britain (before anyone had even heard them) they appropriated the recordings, transmitted them to Britain on the German English language radio service and did nothing to discourage the belief that Wodehouse was a Nazi sympathizer. This was precisely the reverse of the intention of the Foreign Ministry. Americans would have been unimpressed by the Berlin broadcasts of a known British Nazi fellow traveller (such as William Joyce). The fact that Wodehouse was not pro-Fascist but was still allowed to make light of his experiences in a German internment camp was a far more valuable propaganda coup for the Foreign Ministry. The intervention of the Ministry of Propaganda spoiled their rival ministry’s scheme and bathed Wodehouse in an altogether different light than a series of innocuous broadcasts aimed, not at Britain, but at the USA. Later when the Propaganda Ministry asked Wodehouse to make a broadcast about the Katyn massacre (the murder of 4000 Polish officers by the invading Russian army) he refused and told the Foreign Office in Berlin that he would prefer to return to Tost than make any further broadcasts. This was long before he had become aware of the negative reaction to his talks in Britain.

After the liberation of Paris, Wodehouse reported to the American authorities and asked them to alert the British as to his whereabouts. He was visited by the writer and broadcaster Malcolm Muggeridge, then working in British intelligence, who interrogated/interviewed him and came to the conclusion that any charges of treason against Wodehouse would be misplaced, and that he ‘was ill-fitted to live in an age of ideological conflict having no feelings of hatred about anyone, and no very strong views about anything. … I never heard him speak bitterly about anyone — not even about old friends who turned against him in distress.’ A few days later, on 9 September, Wodehouse was subjected to a four day interrogation session with Major E.J.P. Cussen of the Intelligence Corps who had been sent to investigate Wodehouse’s wartime activities on behalf of MI5. Cussen filed his report on 28 September 1944 although his investigation continued into 1945. The report was kept under wraps until 1980. Iain Sproat finally managed to obtained a copy that year, after repeated requests.

On the basis of Cussen’s investigation and report—he described Wodehouse’s behaviour as ‘unwise’ but not treasonous—the British Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), Theobald Mathew, issued a memorandum informing MI5 that ‘there is not sufficient evidence to justify a prosecution of this man. It is possible that information may subsequently come to light, which will establish a more sinister motive for this man’s activities in Germany but, having regard to the nature and content of his broadcasts, there is, at the moment, nothing to justify any action on my part.’

The Attorney General’s announcement of the DPP’s decision in the House of Commons was, however, less than effusive in its assertion of Wodehouse’s innocence. It suggested that there was some fire in the smoke but that there just wasn’t enough evidence to prosecute. That, in effect, condemned Wodehouse, in the court of public opinion, to a lengthy post-war sentence of censure, condemnation and vilification, such as the Daily Worker editorial of 24 November 1944. The socialist newspaper, in its excoriation of Wodehouse, also reflected a profound antipathy towards the perceived betrayal of Britain by an ‘appeasing’ pre-war British aristocracy that had more than a sneaking regard for the anti-labour and anti-democratic sentiments regularly expressed by Hitler.

‘We do not dispute that Wodehouse is as petty and contemptible as the ruling class characters portrayed in his best sellers’ claimed the Daily Worker, ‘But since when has amiability and bone-headedness been an excuse for serving Goebbels? The sloppy Wodehouse broadcasts from Berlin were deliberately selected by the subtle German propagandists. Better a famous British author expressing doubts about the victory of his own country than a second Haw Haw churning out fantastic lies. Wodehouse represents the rottenness that infected a section of Britain in the years preceding the war. His day is over.’

In official circles the impact of Wodehouse’s lukewarm exoneration by the Churchill government was accentuated by the fact that Cussen continued his investigation into 1945, although he did not produce another report. This was probably because the later testimony he received only served to reinforce his original findings of innocence on Wodehouse’s part. The problem, from Wodehouse’s point of view, was that Cussen was not obliged to release, or even to record, additional exculpatory evidence, of which he found much in 1945. His job was simply to establish if there was a prima facie case against the writer. It was the possibility of coming across some damning evidence, previously overlooked, that extended Cussen’s enquiry beyond the presentation to MI5 of his initial report. There was no damning evidence against Wodehouse in 1944 and that did not change as the investigation continued in 1945. But with no need to amend the September 1944 Cussen report, or to outline the new evidence in the Home Office file on Wodehouse, there was no fulsome exoneration of Wodehouse.

Ironically Cussen became so convinced that Wodehouse was innocent of all the charges levelled against him that he encouraged the writer to campaign to clear his name before the British public. Aside from a couple of newspaper interviews, Wodehouse, influenced by advisers and, principally, by his publishers, chose not to do so. He revealed in a letter to the entertainment weekly, Variety, on 8 May 1946 that he had begun to write a memoir of his time as an internee. It was to be called Wodehouse in Wonderland, and included a chapter on the Berlin broadcasts. However, he also had a new Jeeves book coming out in 1946 (Joy in the Morning) and his publishers, Herbert Jenkins in GB and Doubleday in the USA, advised him to put off the publication of this memoir. It never subsequently emerged, much to their relief, as they believed that it would impact the sales of his novels and short stories. They preferred that Wodehouse let sleeping dogs lie, which, arguably, did him a considerable disservice.

The whole controversy is broached in the ironically titled 1953 publication Performing Flea (thank you Sean O’Casey!) a collection of correspondence with his friend Bill Townend from 1920-1953. This included a number of letters about the broadcast controversy. These, however, were not carefully argued apologias setting out the case for the defence. They were generally light-hearted missives, between good friends, in the style and sprit of the broadcasts themselves. The sole exception is a letter of 18 April 1953 in which Wodehouse formally gave Townend permission to publish their correspondence. In this letter he addresses a number of the wilder allegations levelled at him over the years. He admits that ‘I ought to have had the sense to see that it was a loony thing to do to use the German radio for even the most harmless stuff, but I didn’t. I suppose prison life saps the intellect’ and he added in a rider to Townend … ‘You ask do I approve of your publishing this book with all the stuff about my German troubles? Certainly. But mark this, laddy, I don’t suppose that anything you say, or anything I say, will make the slightest damn bit of difference. You need dynamite to dislodge an idea that has got itself firmly rooted in the public mind.’

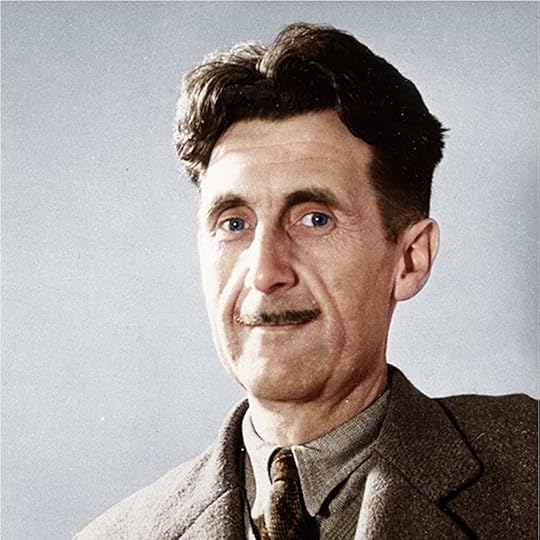

One of Wodehouse’s most prominent post-war defenders was George Orwell. In a 1946 essay, published in Windmill magazine, entitled ‘In defence of P.G.Wodehouse’, Orwell picked apart some of the misapprehensions and outright fabrications that had grown up around the broadcasts. ‘Wodehouse’s main idea in making them,’ Orwell wrote, ‘was to keep in touch with his public and — the comedian’s ruling passion — to get a laugh. Obviously, they are not the utterances of a Quisling of the type of Ezra Pound …’ [The American poet, based in Italy, was a notorious fascist and anti-semite]. Orwell essentially gave Wodehouse a fool’s pardon, asserting that the cloistered and apolitical author, ‘cannot have realised that what he did would be damaging to British interests.’

George Orwell

Orwell pointed out that, in 1940, British attitudes towards the coming conflict were …

‘… noticeably tepid … eminent publicists were hinting that we should make a compromise peace as quickly as possible, trade union and Labour Party branches all over the country were passing anti-war resolutions. Afterwards, of course, things changed … By the middle of 1941 the British people knew what they were up against and feelings against the enemy were far fiercer than before. But Wodehouse had spent the intervening year in internment, and his captors seem to have treated him reasonably well. He had missed the turning-point of the war, and in 1941 he was still reacting in terms of 1939. He was not alone in this. On several occasions about this time the Germans brought captured British soldiers to the microphone, and some of them made remarks at least as tactless as Wodehouse’s. They attracted no attention, however.’

Orwell also cited the timing of Wodehouse’s release from Tost prison, a few days before the invasion of Russia. He posited the theory that Wodehouse’s broadcasts were a small but significant element of German diplomatic efforts to keep the USA out of the war.

‘The release of Wodehouse was only a minor move, but it was not a bad sop to throw to the American isolationists. He was well known in the United States, and he was — or so the Germans calculated — popular with the Anglophobe public as a caricaturist who made fun of the silly-ass Englishman with his spats and his monocle. At the microphone he could be trusted to damage British prestige in one way or another, while his release would demonstrate that the Germans were good fellows and knew how to treat their enemies chivalrously.’

Orwell went on to observe, in the spirit of the Daily Worker editorial of November 1944, that the British upper classes ‘were discredited by their appeasement policy and by the disasters of 1940, and a social levelling process appeared to be taking place. Patriotism and left-wing sentiments were associated in the popular mind, and numerous able journalists were at work to tie the association tighter.’ Among the ‘able journalists’ was William ‘Cassandra’ Connor, hence the deluge of working-class support for his 15 July 1941 BBC anti-Wodehouse philippic. Orwell continued …

‘In this atmosphere, Wodehouse made an ideal whipping-boy. For it was generally felt that the rich were treacherous, and Wodehouse — as “Cassandra” vigorously pointed out in his broadcast — was a rich man. But he was the kind of rich man who could be attacked with impunity and without risking any damage to the structure of society. To denounce Wodehouse was not like denouncing, say, Beaverbrook. A mere novelist, however large his earnings may happen to be, is not of the possessing class.’

Orwell concluded the article by appealing for forgiveness for someone who ‘became the corpus vile in a propaganda experiment’

‘In the case of Wodehouse, if we drive him to retire to the United States and renounce his British citizenship, we shall end by being horribly ashamed of ourselves. Meanwhile, if we really want to punish the people who weakened national morale at critical moments, there are other culprits who are nearer home and better worth chasing.’

Wodehouse remained in France until 1947 and never returned to the UK from the time he and his wife moved back to the USA (April 1947) to the time of his death in 1975. He did not renounce his British citizenship, however, and he continued to write about an England which, he candidly admitted in a 1950 interview, was ‘gone … some people think [it] never existed’. (Orwell had dated its demise as being as early as 1915). Even when Wodehouse was in his 90s British journalists, in interviews to promote his work, much to his annoyance (but hardly unexpectedly, and with absolute validity) continued to ask him about the Berlin broadcasts.

In 1975 the UK government made restitution/acknowledged his innocence/said ‘let bygones be bygones’ (delete as appropriate), when he was awarded a Knighthood of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) thanks to the intervention of Labour party prime minister Harold Wilson. This had already been proposed on a number of occasions since the mid 1960s but had been vetoed by civil servants. The Times wrote of the announcement in the January 1975 Honours List that it marked ‘official forgiveness for his wartime indiscretion. … It is late, but not too late, to take the sting out of that unhappy incident.’ Wodehouse lived for barely a month after the announcement, dying of a heart attack in a Long Island hospital on 14 February 1975, aged 93.

In much the same way as his contemporary and compatriot, Charlie Chaplin, regained the affections of the American people and received an honorary Academy Award (and the longest standing ovation in Oscar history) after his own self-imposed exile in the wake of allegations of being a communist fellow traveller, Wodehouse slowly regained the esteem of his fellow countrymen. If the work of the patently antisemitic fascist sympathiser, Ezra Pound, was rehabilitated [his poetry is still taught on third level literature courses] it stood to reason that the gentle humour of the apolitical Wodehouse would be likely to weather the storm of often ill-informed, if generally valid, criticism and condemnation. Most of the work of Wodehouse is still in print and he is as popular today as he was in the pre-war era, and again at the time of his death, almost fifty years ago. He may, as George Orwell observed, have been ‘his own Bertie Wooster’ when he unwisely agreed to allow himself to become a minor tool of the Nazi propaganda machine, but his readers, including a generation unborn at the time of his broadcasts, (including the current writer) while not offering him a free pass, allowed him a fool’s pardon. Given his own reaction to his appalling decision-making in July 1941, Wodehouse was happy enough to accept this qualified absolution. As he put it himself, ‘The whole thing is an example of what a blunder it is to let your feelings get the better of your prudence.’