S.W. O'Connell's Blog

November 24, 2025

The Polymath Spy

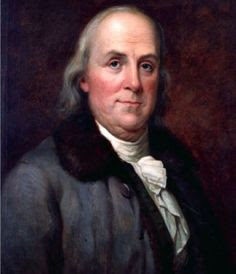

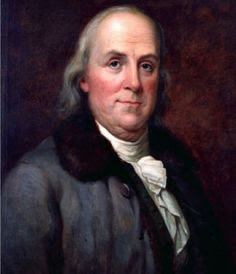

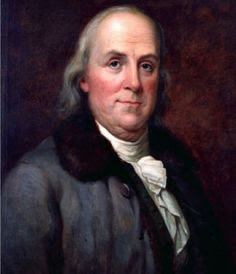

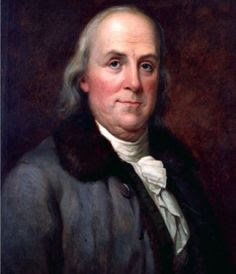

In the chillDecember of 1776, as ice floes were forming on the Delaware River, the USS Reprisal docked at Auray, a port town shrouded in Atlantic mist. Benjamin Franklin, akey historical figure in my novel, The Reluctant Spy, stepped onto whatwould prove to be a decisive, if not kinetic, field of battle.

Sailing to France

Sailing to FranceDoctor in theHouse?

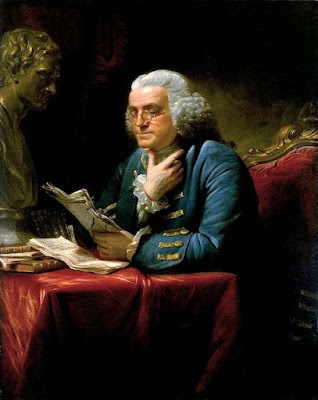

At the then veryripe age of seventy, the polymath from Philadelphia—printer, inventor,philosopher—arrived not as a conqueror but as a supplicant spy, his fur cap andspectacles deliberately signaling rustic American virtue. Dispatched byCongress, Franklin's mission was to persuade the French King Louis XVI to join the war againstBritain and secure more loans, arms, and ships to shift the balance inAmerica's favor. To achieve this, he would walk a tightrope among the mostskilled practitioners of the dark arts in history.

King Louis XVI

King Louis XVI

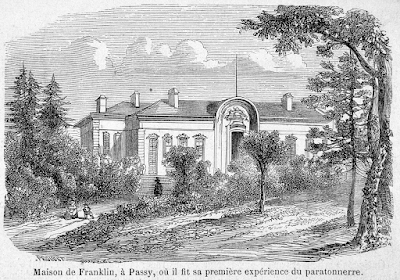

Franklin's Home Away from Home: Hotel Le Valentinois

Franklin's Home Away from Home: Hotel Le Valentinois

Chief among hispatrons and adversaries was Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, the foreign ministerwhose gaze fixed on Britain's North American jewel. Vergennes, acalculating aristocrat scarred by the Seven Years' War's humiliations, saw therebels as a tool for French revenge.

Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes

Charles Gravier, comte de VergennesFranklin knew asmuch and outwitted him masterfully, hosting salons where philosophes likeRaynal and d'Alembert debated liberty over claret, subtly steering discoursetoward Franco-American solidarity. "We must make them believe the cause istheirs," Franklin confided to Deane, his early ally—a Connecticut merchantwhose prior secret shipments of powder had already greased the wheels.

Working the “Street”Yet alliances were fragile blooms ina thorned garden. Franklin's network extended into the underworld — a tangledweb of booksellers, couriers, and informants who smuggled secrets amid salonsand at French ports, where informants tracked British naval dispatches. He evenenlisted the Marquis de Lafayette's circle, funneling funds to the youngnobleman's expeditionary force.

Charles-Joseph Panckoucke

Charles-Joseph PanckouckeA key ally was Charles-JosephPanckoucke, the powerhouse Parisian bookseller and publisher whose Palais-Royal shop was a revolutionary printing hub. He openly collaborated with Franklin,churning out pro-American pamphlets such as the Affaires de l'Angleterreet de l'Amérique series in 1776–1777 to sway French public opinion andelites toward an alliance.

By 1777, more French gunpowder andmuskets flowed covertly to Washington's ragged Continentals, sustaining ValleyForge's winter quarters.Sultan ofSophistication

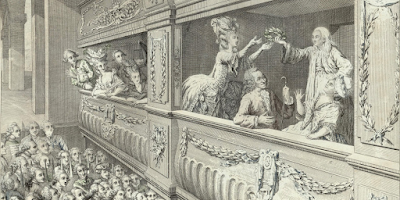

Franklin'sespionage was no cloak-and-dagger affair so much as a symphony of subtlety. Hecultivated British expatriates in Paris, posing as a harmless savant whileextracting tidbits on troop movements from loose-lipped officers at the iconic theater and social venue, Comédie-Française.

Comédie-Française

Comédie-Française

One such ploynetted details of Burgoyne's Saratoga campaign, intelligence relayed ininvisible ink to Congress. The stunning American victory at Saratoga thatOctober sealed the deal: bolstering American morale and tipping Vergennestoward an open alliance. In February 1778, France formalized the Treaty ofAmity and Commerce and the Treaty of Alliance in a blaze of mutualpledges—commerce, defense, and the dream of a transatlantic republic. A formaldeclaration of war came the following month.

Signing the TreatiesSpies Among Us

Signing the TreatiesSpies Among UsAdversarieslurked in every corner of the city. The British embassy, a hive of spies underPaul Wentworth and Edward Bancroft—a turncoat American chemist in Franklin'sown employ—plotted ceaseless sabotage. Bancroft, double-dipping for Londonwhile transcribing Franklin's dispatches in lemon juice, fed Whitehall a streamof half-truths, nearly unraveling the mission when forged letters in 1778accused Deane of profiteering.

Edward Bancroft

Then there wasArthur Lee, Franklin's fellow commissioner, a Virginia lawyer whose paranoiafestered into outright enmity. Lee, sidelined by his own prickly demeanor,accused Franklin of embezzlement and senility, caballing with British agents todiscredit him. "Lee is a wretch," Franklin later quipped, but thebarbs stung, fracturing the American delegation and inviting French skepticism.

Beyond, GeorgeIII's envoys like William Eden prowled the salons, dangling peace overtures topeel France away. At the same time, Prussian and Spanish diplomats—wary ofBourbon overreach—whispered doubts in Vergennes's ear.

ObstaclesChallenges mounted.Secrecy was paramount. A single leak could summon British frigates to Brest.Franklin countered using a cipher system blending Polybius squares andhomophonic substitutions, smuggling letters in wine bottles or hollowed canes.

Crafting Secret Letters

Crafting Secret LettersFinancial straitsgnawed deeper—Congress's credit evaporated amid war's voracity, forcingFranklin to beg loans from French bankers like the Neufvilles, who demandedruinous interest. "I am become the diplomatic beggar of Europe," helamented in a dispatch.

Chick Magnet

Chick MagnetYet he respondedwith unflagging bonhomie, charming Versailles courtiers with bifocaldemonstrations and anti-slavery tracts that aligned American ideals with Frenchhumanism. Franklin used his avuncular image to woo the French noblewomen. A trait that his other commissioners foundoff-putting, but yielded no small conquests.

Twists and BarbsWhen Britishspies torched American supply ships in the summer of 1779, cripplingreinforcements bound for the Carolinas, Franklin retaliated not with rage but witha mock obituary for the "late" General Howe (who returned to Britain in disgrace in 1778), circulated in privateletters, humiliated London, and eroded morale. To the French, he spun the arsonas proof of British desperation, urging Vergennes to dispatch Admirald'Estaing's fleet anew, even as d'Estaing's stalled Savannah siege that autumntested the alliance's mettle.

The "Late" General Howe

The "Late" General HoweMeanwhile, Bancroft'sbetrayals went unnoticed, but Lee's slanders echoed through Congress, andBritain's steadfast resolve suggested a tough struggle ahead. Franklin, alwaysthe optimistic strategist amid chaos, wrote to Washington: "Persevere, andthe sun will break through."

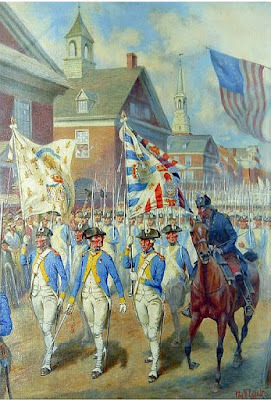

Deception’sTwilightBy the close of1778, Franklin sat by Passy's hearth, spectacles fogged by pipe smoke, studyinga chessboard tilted in delicate advantage. The alliance thrived—French ships filled with cannon slicing through Atlantic waves, Vergennes's coffers opening for yet another loan, and soon French soldiers would fight side by side with the hard-pressed Americans.

The French Army - Crucial to Victory

The French Army - Crucial to VictoryThe old scholarhad woven a web of cleverness and charm, outsmarting empires with a smile and asecret. His first year in Paris marked a tour de force of realpolitik amid therising storm. He would need to keep playing his game, as the stakes would be higher as the long-warring nations struggled to reach peace.

October 31, 2025

Spirits of Seventy-Six

Ever since I posted my vintageYankee Doodle Spies Blog titled, “George Washington, Vampire Slayer,” I havewanted to share more Revolutionary War stories from beyond the grave. Below aremore ghostly figures who continue to march (or drift) to a haunting version ofthe Yankee Doodle tune. Recent reports by paranormal investigators includeElectronic Voice Phenomena (EVPs), which are sounds or voices recorded onelectronic devices. EVP recordings oftenhappen in environments with background noise and are interpreted as messagesfrom the deceased. Some believe these are communications from spirits.

All these sightings are lore, passed down over theyears by visitors and caretakers who hardly believe what they see, but arestill spooked all the same.

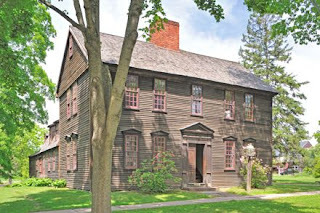

The Anguished Angel

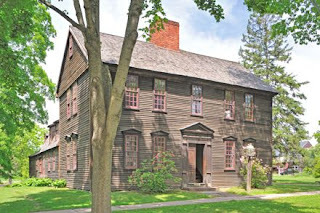

Built in 1716, Concord's ColonialInn served as a temporary hospital during the Revolutionary War, treatingwounded soldiers after the Battles of Lexington and Concord. Legend connects itto a nurse named Rosemary, a middle-aged caregiver who tended to the injuredamid the chaos of 1775. Reports describe her apparition as a spectral woman inold-fashioned nursing attire. The anguished angel of mercy drifts silentlythrough dimly lit hallways, her footsteps silent but her presence chills theair. Guests in Room 24, a corner chamber with creaking floorboards and antiquefurnishings, often wake to grayish figures huddled in pain—wounded soldierswith bandaged limbs and vacant stares, vanishing like mist when approached.Cold spots appear unexpectedly, doors latch shut on their own, and faintmedicinal scents linger.

The Concord Inn

The Concord InnOne account from 2018 details afamily hearing labored breaths and seeing a translucent figure checking anempty bed before fading away. Paranormal investigators capture EVPs of whisperslike "hold on" and orbs in photos. These sightings continue, echoingthe inn's bloody past.

A Smuggler’s Spirit

Copp’s Hill Burying Ground,established in 1659, overlooks the site of the 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill,where British artillery targeted the North End, riddling gravestones withcannon fire. Captain Daniel Malcolm, a Sons of Liberty smuggler who evaded dutieson 60 casks of wine, lies beneath one of the most scarred markers—a wingedskull epitaph declaring him a "True Son of Liberty." His spirit,restless from the desecration, reportedly stirs paranormal activity: strangelights flicker like musket flashes among the crooked slate stones at dusk,casting elongated shadows that twist unnaturally. Muffled cries echo as if fromwounded ranks, groans rise like wind through pines, and translucent figures intricorn hats pace the paths, halting abruptly. Visitors feel an icy grip ontheir shoulders or hear gravel crunch under invisible boots.

Captain Daniel Malcolm's Gravestone

Captain Daniel Malcolm's GravestoneA 2023 account describes a groupphotographing the pockmarked stone when orbs swirled, accompanied by a guttural"liberty" whisper on recordings. The hauntings peak on foggy nights,blending colonial fury with eternal vigilance.

Sentinel SpooksOn September 6, 1781, during theBattle of Groton Heights, 160 American defenders held Fort Griswold against 800British raiders led by Benedict Arnold. Despite inflicting heavy losses, thegarrison faced a massacre after surrender. Lieutenant-Colonel William Ledyardwas bayoneted, and many were slain or wounded inside the redoubt. Today, thesite is a state park with the Groton Monument overlooking the Thames River, andit’s filled with stories of restless spirits. Wounded defenders sometimesappear beside modern picnickers on the grassy slopes—gaunt figures in bloodiedlinen shirts, leaning on muskets with vacant eyes fixed on the horizon. Suddenchills sweep through groups mid-meal, accompanied by ragged breaths and thesound of phantom footsteps on the earthworks.

Fort Griswold

Fort GriswoldA 2025 report describes a familyseeing translucent soldiers resting against the ramparts, their groanssynchronized with the wind before vanishing. EVPs capture pleas like"mercy" near the death hole where bodies were piled. The hauntingsgrow stronger at dawn, recalling the betrayal and brutality that marked thisforgotten outpost.

A Southern SpiritThis legend is strikingly similarto the famed “Headless Horseman.” In 1781, during a Patriot raid on WedgefieldPlantation near Georgetown, South Carolina, British dragoons guarded theproperty and some prisoners amid the chaos of the Southern Campaign—specifically,some of the famed “Swamp Fox” Francis Marion’s men. A clash ensued when a rescueparty arrived. One sentry, beheaded by a swift sword stroke in the skirmish,became the lore's centerpiece: "The Headless Sentry." Apologies toIchabod Crane!

At twilight, the sentry’sapparition staggers across the yard—a headless torso in a tattered red coat andriding boots, his large flintlock pistol gripped in a gloved hand, gropingblindly for his lost head. Hoofbeats thunder or chains rattle from nowhere,building to a frenzy as he lurches toward witnesses, the ragged neck stumpoozing ethereal blood. Approachers hear guttural gurgles, feel a rush of fetidbreath, before he dissolves into mist.

Headless Dragoon Haunts sthe Bunkers

Headless Dragoon Haunts sthe BunkersThe estate is now a golf courseresidential community, but that has not driven away the ghost—a 2020 video fromgolfers captured distorted audio of clopping hooves and a form flickering nearthe clubhouse. The ghost writhers on grounds where the raid unfolded, pistolraised in futile defense, vanishing at full dark. This tale warns of war'sdismembering toll and its effect on your handicap!

Warrior WhispersFrom 1776 to 1783, British prisonhulks in Wallabout Bay held over 11,500 American captives in squalor; disease,starvation, and abuse claimed most, their bones dumped into unmarked graves nowbeneath Fort Greene Park's Prison Ship Martyrs' Monument—a 149-foot Doriccolumn dedicated in 1908. Lore clings to the waterfront: faint whispers ofmartyred Patriots drift on breezes by the East River, spectral murmurs of"freedom" or chained coughs blending with lapping waves. At dusk,visitors near the monument hear ragged breaths from the crypt below, whereremains were reinterred, or glimpse emaciated shadows shuffling in fettersalong the shore. Cold fog rolls in unbidden, carrying briny rot and distantclanks of irons.

Martyrs Monument

Martyrs Monument

A 2017 historical tour reportedEVPs of overlapping pleas amid the hum of traffic, tying back to the"ghost ship" Jersey's horrors. These echoes mark the unseengraveyard, a silent rebuke to forgotten suffering.

The Phantom EncampmentValley Forge National HistoricalPark in Pennsylvania marks the grueling winter encampment of the ContinentalArmy from 1777-1778, where around 2,500 soldiers died from typhus, pneumonia,and starvation in the freezing cold, their shelters just simple log huts amidfrozen fields. Archaeological evidence shows most bodies were taken to distanthospitals for burial, leaving the site eerily free of graves, yet the sense oftragedy remains. Victorian-era romanticism created the legend, adding whispersof unrest. Phantom soldiers in threadbare blue coats trudge across snowlesspaths at sunset, bayonets shining under moonlit oaks, their empty footstepsmatching phantom drum rolls that unset modern nerves. Distant musket cracksbreak the silence, as if volleys echo from unseen lines. On stormy nights,ghostly campfires glow across barren hillsides—orange flickers drawing eyes toshadows huddled for warmth, faces gaunt and frostbitten, vanishing withthunderclaps.

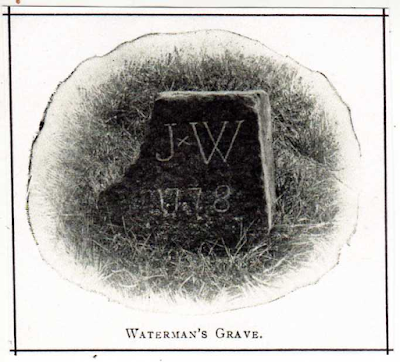

Since reports began in 1895, witnesses have glimpsed a solitary sentry saluting, his tricorn hat cast in shadow. South of Route 23, near Varnum's quarters, an "JW" headstone commemorates Lieutenant John Waterman, who died on April 23, 1778. A 1901 obelisk, relocated in 1939, sparks tales of wraiths clawing from the soil, although no haunt linked to him has been proven—only legends of his vigilant shade patrolling the monument with eyes fixed on intruders.

The Haunted Obelisk

The Haunted Obelisk

September 28, 2025

A Peer in Paris

As Paris buzzed with intrigue during the AmericanRevolution, Lord David Murray, the seventh Viscount Stormont, the Britishambassador to Louis XVI's court and chief of intelligence, was at the center ofthis complex web of intrigue. Appointed in 1772, Stormont was a Scottish peerrelated to Lord Mansfield, the chief justice who had ruled against colonialprotests during the Stamp Act crisis of 1765. His diplomatic cover cloakedespionage aimed at blocking French support for the rebelling colonies.

Lord Stormont

Lord Stormont

The 1776 Declaration of Independence upped the stakes.George Washington's Continental Army faced severe shortages of weapons, powder,and funds. Franklin's arrival in Paris in December was a game-changer: thePhiladelphian captivated French intellectuals and aristocrats alike. He lobbiedForeign Minister Charles Gravier, the Comte de Vergennes, for more covert aid.Vergennes, estimating the strategic blow to Britain, authorized secretshipments through intermediaries, such as the front company Rodrigue, Hortelez& Cie.

Comte de Vergennes

Comte de Vergennes

From his Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré estate, Stormont took thisas a dire threat. His network, funded by Whitehall subsidies and coordinatedwith Loyalist exiles, became Britain’s eyes and ears in a city full of conspiracy.At the core of Stormont's operation was Dr. Edward Bancroft, aMassachusetts-born physician and chemist whose scientific credentials maskedhis duplicity. Recruited in March 1776 by British secret service agent PaulWentworth, a wealthy Loyalist tobacco merchant acting as Stormont's intermediary,Bancroft had infiltrated the American mission.

Edward Bancroft

Placement and AccessServing as Silas Deane's secretary—the Connecticut merchanttasked with buying munitions—Bancroft gained access to Franklin's villa inPassy, a hub of covert diplomacy. From there, he documented every detail:Vergennes' promises of gunpowder, arms shipments disguised as commercial cargo;the negotiations over loans to fund the American cause. Bancroft’s use ofspycraft was brilliant. He used stain (invisible ink), hidden papers, andpseudonyms.

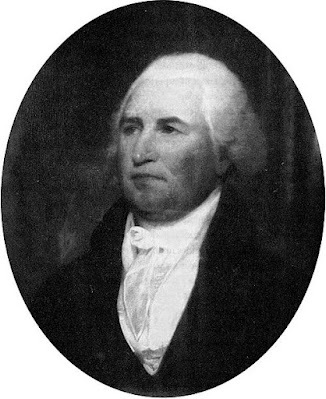

Silas Deane

Silas Deane

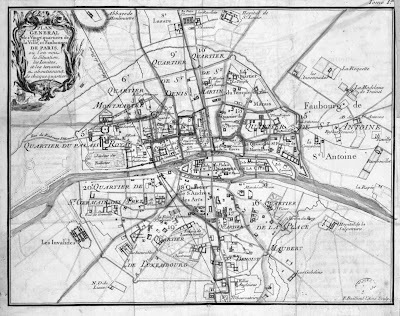

He made weekly visits to a “dead drop" in a crevice atthe base of a tree on the south terrace of the Jardin des Tuileries. Stormontdispatched his private secretary, Thomas Jeans, who retrieved these drops underthe cover of darkness. Stormont’s instructions and new requests forintelligence were also left by Jeans, often accompanied by payments of up to£500 annually.

Jardin des Tuileries

Jardin des Tuileries

By April 1777, asnegotiations between France and America intensified, Bancroft's leaks includedverbatim transcripts of commissioners' minutes and drafts of the 1778 Treaty ofAlliance. One dispatch, smuggling the final version of the treaty, reached KingGeorge III within 48 hours of its signing in Paris, allowing Britain to preparenaval responses.

King George III

King George III

Stormont used this intelligence in heated meetings withVergennes, citing specifics to accuse France of violating the 1776 Treaty ofCommerce and demanding inspections—his démarches spawned hesitation and boughtBritain months of breathing space.

Signing the Treaty

Signing the Treaty

His influence reached the Atlantic ports ofLorient, Brest, and Nantes, which were crucial points for American supplies.Here, a network of embedded agents—dockyard foremen, corrupt customs officials(douaniers), and bribed ship chandlers—monitored rebel privateers such as the USS Reprisal,commanded by the daring American Captain Lambert Wickes.

USS Reprisal

USS Reprisal

Stormont’s informants tracked illegal exchanges: Americantobacco and indigo were traded for Charleville muskets and gunpowder, which wasrouted through Roderigue Hortalez et Cie.

Actionable IntelligenceIn July 1777, Lambert Wickes' squadron escorted a Dutchconvoy loaded with arms past Ushant. Stormont's informers provided intelligencethat led the Royal Navy to intercept the convoy, seizing prizes worth £100,000. Asthe British ambassador, he issued a strong démarche to Versailles. Thispressured Vergennes to issue mild protests against "illegal" sailing. Although enforcement was pro forma,Stromont’s protests delayed France’s full naval involvement until 1778.

Illegal Sailing

Illegal Sailing

Meanwhile, spymaster Stormont developed a mole within theForeign Ministry's Archives Section—a junior archivist, possibly bribed with500 louis d'or—who stole dispatches from locked cabinets.

Lord North

Lord North

Breaking into the Quai d'Orsay's bureaucracy was a masterstroke against the French. These stolendispatches revealed Franco-American subsidies, as well as overtures to Spain'sCharles III for a Mediterranean diversion against Gibraltar. Stormont forwardedcopies to London via secure couriers, helping Prime Minister Lord North lobbyneutral European nations, such as the Dutch, against Bourbon plans.

Unplugging the ElectricianBut no target infuriated Stormont more than Franklin, the"electrician of sedition,” whose charm threatened French neutrality.Intercepts exposed Franklin's secret letters to William Petty, the second Earlof Shelburne, a Whig opposition leader who called the war "madness"in Parliament and secretly provided £10,000 to American agents such as ArthurLee.

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin

In a slick psychological operation, Stormont leaked"correspondence" accusing Franklin of treasonous dealings—leakingrebel plans to Lord Shelburne for personal gain.These accusations were circulated in London newspapers and Paris coffeehouses,sparking a scandal.

Lord Shelburne

Lord ShelburneAngered at the false reports, Shelburne fought a duel withhis purported accuser, Colonel William Fullarton, in Hyde Park, but bothsurvived unscathed. This episode damaged trust within the American delegation,with Deane suspecting Lee of leaks and making French courtiers wary of deeperinvolvement. It also provided the predicate for my fifth novel in the YankeeDoodle Spies series, The Reluctant Spy.

Success and FailureLord Stormont’s web of espionage delayed French armsshipments, kept London apprised of secret negotiations, and sowed discord amongboth French and American diplomats. However, Stormont's efforts in Paris could not stopthe momentum of support for America by France, Spain, and the Netherlands.

Admiral d'Estaing

Admiral d'Estaing

After the treaty of alliance was signed in 1778, Frenchfleets under Admiral d'Estaing sailed for Savannah, shifting the war. Stormont, whoseprotests were ignored, was recalled that June — bringing a great sigh of reliefto Vegennes and Franklin. Although his network dissolved, its efforts hadsustained the British struggle for two more years—a testament to the power ofespionage in the forging of revolution.

The Peer's PostscriptIn a final note, Edward Bancroft's treason to America wasnot revealed in 1889 — from Stormont's secret papers—highlighting how Britain’sintelligence secrets were sustained over many decades.

August 27, 2025

The Clockmaker's Gambit

In April 1775, the American colonies had burst into open rebellion against King George III. In the glittering salons of Paris, whispersof liberty mingled with the clink of wine glasses as the nobility watched thewar in America unfold from afar. Some volunteered to join the fight, defyingtheir King Louis XVI's wishes. Most simply read the bulletins andbroadsheets, whispering their support.

Beaumarchais: Clcomaker, Playwright & Spy

Beaumarchais: Clcomaker, Playwright & SpyBut a commoner, a clockmaker and part-time playwright, wasweaving a web that would stretch across the Atlantic and help give birth to anation. Pierre Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, a watchmaker turned playwright,was about to help elevate the most significant rebellion of the century.

The ClockmakerBorn in 1732 to a Parisian clockmaker, young Pierre Caronwas no stranger to tinkering. His skillful fingers crafted timepieces so finethey caught the eye of King Louis XV’s court. By his twenties, he had charmedhis way into Versailles, teaching harp to the royal daughters and earning thenoble suffix “de Beaumarchais” through a clever marriage and a talent forreinvention. His skills brought him close to young Louis XVI, an amateur clockmaker.

18th-century Century Clocks were High Tech Gadgets of the Age

18th-century Century Clocks were High Tech Gadgets of the AgeThe Playwright

But clocks and courtly manners were just the beginning.Beaumarchais had a restless mind, thriving on the stage and in the shadows. His plays, like The Barber of Seville and The Marriage of Figaro, delivered sharp jabs at the aristocracy, earning him both applause and enemies. His plays drew the King's ire and were banned, but later revived as operas by Mozart. By the 1770s, he wore manymasks: dramatist, merchant, and secret agent for the French crown.

Scene from Marriage of Figaro

Scene from Marriage of FigaroA Complex Script

But it was in a different kind of play where Beaumarchaistruly found his calling. France, still sore from its defeat in the Seven Years’War, saw a chance to poke Britain in the eye by aiding the American rebels. ButLouis XVI, cautious of open war, needed plausible deniability. Beaumarchais's flairfor drama made him the perfect man to orchestrate a covert operation.

King Louis XVI

King Louis XVIIn 1775,he met with American agents in London, including Arthur Lee, a Virginia lawyerwith a fiery patriot’s spirit. Lee’s stories of colonial resolve ignited aspark in Beaumarchais. Here was a cause that blended profit with principle—achance to arm the rebels, weaken Britain, and help rearm France.

The PitchmanBeaumarchais pitched his plan to Foreign Minister Comte de Vergenneswith the enthusiasm of a man promoting a hit play. “Sire, the Americans needmuskets, powder, and cannon,” he argued. “Let me supply them through a front—atrading company. France stays clean, Britain is caught off guard, and libertywins.” Vergennes, no fool, saw the merit.

Comte de Vergennes

Comte de Vergennes

By 1776, Beaumarchais had createdRoderigue Hortalez & Compagnie, a front (a sort of shell) company thatacted as both merchant house and espionage hub. With a million Livres from theFrench treasury (and another from Spain, persuaded by Beaumarchais’ silvertongue), our playwright got to work.

Secret ScriptImagine a busy office in Paris, clerks scribbling invoices,while in the back room, Beaumarchais haggles with arms dealers and dodgesBritish spies. The operation was a dangerous game. Britain’s spies prowled thedocks, looking for French interference.

Back-room Scheming and Planning

Back-room Scheming and Planning

Beaumarchais wrote coded letters, usedaliases like “Durand,” and spun stories to mislead the enemy. One moment, hewas a merchant shipping “cloth” to the West Indies; the next, he was smugglingmuskets to American privateers. His ships, loaded with 200 cannons, 25,000muskets, and tons of gunpowder, sailed under neutral flags to ports likeSaint-Domingue, where American agents waited.

Stormy Reviews

But the sea was no friend to Beaumarchais. Storms, Britishpatrols, and shoddy captains sank half his cargoes. Worse, the Americans wereslow to pay. Congress, short on cash, sent promissory notes and tobacco insteadof money.

Stormy Seas, Secret Cargoes

Beaumarchais was under pressure but kept going, driven by a mix ofideals and ambition. His supplies arrived at critical moments for GeneralWashington’s army. At Saratoga in 1777, American troops, armed with Frenchmuskets, crushed General Burgoyne’s redcoats—a victory that convinced France tojoin the war openly. Beaumarchais’ guns had tipped the scales.

The Clock StrikesDespite his successes, Beaumarchais’ life was a riskybalancing act. His enemies at court, jealous of his influence, whisperedaccusations of treason. His debts piled up as Congress delayed payments. In1777, he faced brief exile after a duel gone wrong but bounced back, ever thesurvivor. His plays kept him in the public eye, their sharp wit echoing his owndefiance. The Marriage of Figaro, banned for its cheek, was a jab at theold order—a nod, perhaps, to the American rebels he admired.

Resetting the ClockBy 1778, France’s formal alliancewith America changed Beaumarchais’s role. His secret trading gave way toofficial French aid. But he kept scheming, running spy operations forVergennes, uncovering British plans, and even outfitted ships for privateeringto harass British trade. Theseactivities were less about traditional espionage and more about logisticalcoordination to disrupt British supply lines. For instance, Beaumarchais usedhis network to monitor British merchant vessels, enabling privateers to targetthem effectively, which indirectly supported the Allied war effort.

Doctor Franklin

Doctor Franklin

His Paris home became a hub forAmerican envoys like Silas Deane and Benjamin Franklin, who valued his charmand connections. Franklin, in his fur cap and with a sly grin, calledBeaumarchais “a genius in his way,” though he joked about Beaumarchais’ endlessrequests for repayment.

Winding DownBy 1779, his focus increasinglyshifted to settling financial disputes with the Continental Congress overunpaid debts for earlier covert aid, decreasing his role inintelligence-gathering. The war’s end in 1783 didn’t bring peace forBeaumarchais. Congress owed millions, but American funds were limited. He spentyears chasing debts, with his wealth shrinking.

Peace celebrated in Paris

Peace celebrated in Paris

When the French Revolution brokeout in 1789, Beaumarchais supported its ideals but recoiled at its violence.Accused of hoarding arms, he fled to Germany, returning only afterRobespierre’s fall. He died in 1799, his life a whirlwind of victories and setbacks.

Storming the Bastille Launched the Revolution

Curtain Call

Beaumarchais saw America’s fightas a reflection of his own struggles against privilege and authority. His playsmocked the nobility; his guns supported the rebels. He was a man full ofcontradictions—a courtier who despised tyranny, a profiteer risking everythingfor a cause.

The Watchmaker's Gambit

In April 1775, the American colonies had burst into open rebellion against King George III. In the glittering salons of Paris, whispersof liberty mingled with the clink of wine glasses as the nobility watched thewar in America unfold from afar. Some volunteered to join the fight, defyingtheir King Louis XVI's wishes. Most simply read the bulletins andbroadsheets, whispering their support.

Beaumarchais: Clcomaker, Playwright & Spy

Beaumarchais: Clcomaker, Playwright & SpyBut a commoner, a clockmaker and part-time playwright, wasweaving a web that would stretch across the Atlantic and help give birth to anation. Pierre Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, a watchmaker turned playwright,was about to help elevate the most significant rebellion of the century.

The ClockmakerBorn in 1732 to a Parisian clockmaker, young Pierre Caronwas no stranger to tinkering. His skillful fingers crafted timepieces so finethey caught the eye of King Louis XV’s court. By his twenties, he had charmedhis way into Versailles, teaching harp to the royal daughters and earning thenoble suffix “de Beaumarchais” through a clever marriage and a talent forreinvention. His skills brought him close to young Louis XVI, an amateur clockmaker.

18th-century Century Clocks were High Tech Gadgets of the Age

18th-century Century Clocks were High Tech Gadgets of the AgeThe Playwright

But clocks and courtly manners were just the beginning.Beaumarchais had a restless mind, thriving on the stage and in the shadows. His plays, like The Barber of Seville and The Marriage of Figaro, delivered sharp jabs at the aristocracy, earning him both applause and enemies. His plays drew the King's ire and were banned, but later revived as operas by Mozart. By the 1770s, he wore manymasks: dramatist, merchant, and secret agent for the French crown.

Scene from Marriage of Figaro

Scene from Marriage of FigaroA Complex Script

But it was in a different kind of play where Beaumarchaistruly found his calling. France, still sore from its defeat in the Seven Years’War, saw a chance to poke Britain in the eye by aiding the American rebels. ButLouis XVI, cautious of open war, needed plausible deniability. Beaumarchais's flairfor drama made him the perfect man to orchestrate a covert operation.

King Louis XVI

King Louis XVIIn 1775,he met with American agents in London, including Arthur Lee, a Virginia lawyerwith a fiery patriot’s spirit. Lee’s stories of colonial resolve ignited aspark in Beaumarchais. Here was a cause that blended profit with principle—achance to arm the rebels, weaken Britain, and help rearm France.

The PitchmanBeaumarchais pitched his plan to Foreign Minister Comte de Vergenneswith the enthusiasm of a man promoting a hit play. “Sire, the Americans needmuskets, powder, and cannon,” he argued. “Let me supply them through a front—atrading company. France stays clean, Britain is caught off guard, and libertywins.” Vergennes, no fool, saw the merit.

Comte de Vergennes

Comte de Vergennes

By 1776, Beaumarchais had createdRoderigue Hortalez & Compagnie, a front (a sort of shell) company thatacted as both merchant house and espionage hub. With a million Livres from theFrench treasury (and another from Spain, persuaded by Beaumarchais’ silvertongue), our playwright got to work.

Secret ScriptImagine a busy office in Paris, clerks scribbling invoices,while in the back room, Beaumarchais haggles with arms dealers and dodgesBritish spies. The operation was a dangerous game. Britain’s spies prowled thedocks, looking for French interference.

Back-room Scheming and Planning

Back-room Scheming and Planning

Beaumarchais wrote coded letters, usedaliases like “Durand,” and spun stories to mislead the enemy. One moment, hewas a merchant shipping “cloth” to the West Indies; the next, he was smugglingmuskets to American privateers. His ships, loaded with 200 cannons, 25,000muskets, and tons of gunpowder, sailed under neutral flags to ports likeSaint-Domingue, where American agents waited.

Stormy Reviews

But the sea was no friend to Beaumarchais. Storms, Britishpatrols, and shoddy captains sank half his cargoes. Worse, the Americans wereslow to pay. Congress, short on cash, sent promissory notes and tobacco insteadof money.

Stormy Seas, Secret Cargoes

Beaumarchais was under pressure but kept going, driven by a mix ofideals and ambition. His supplies arrived at critical moments for GeneralWashington’s army. At Saratoga in 1777, American troops, armed with Frenchmuskets, crushed General Burgoyne’s redcoats—a victory that convinced France tojoin the war openly. Beaumarchais’ guns had tipped the scales.

The Clock StrikesDespite his successes, Beaumarchais’ life was a riskybalancing act. His enemies at court, jealous of his influence, whisperedaccusations of treason. His debts piled up as Congress delayed payments. In1777, he faced brief exile after a duel gone wrong but bounced back, ever thesurvivor. His plays kept him in the public eye, their sharp wit echoing his owndefiance. The Marriage of Figaro, banned for its cheek, was a jab at theold order—a nod, perhaps, to the American rebels he admired.

Resetting the ClockBy 1778, France’s formal alliancewith America changed Beaumarchais’s role. His secret trading gave way toofficial French aid. But he kept scheming, running spy operations forVergennes, uncovering British plans, and even outfitted ships for privateeringto harass British trade. Theseactivities were less about traditional espionage and more about logisticalcoordination to disrupt British supply lines. For instance, Beaumarchais usedhis network to monitor British merchant vessels, enabling privateers to targetthem effectively, which indirectly supported the Allied war effort.

Doctor Franklin

Doctor Franklin

His Paris home became a hub forAmerican envoys like Silas Deane and Benjamin Franklin, who valued his charmand connections. Franklin, in his fur cap and with a sly grin, calledBeaumarchais “a genius in his way,” though he joked about Beaumarchais’ endlessrequests for repayment.

Winding DownBy 1779, his focus increasinglyshifted to settling financial disputes with the Continental Congress overunpaid debts for earlier covert aid, decreasing his role inintelligence-gathering. The war’s end in 1783 didn’t bring peace forBeaumarchais. Congress owed millions, but American funds were limited. He spentyears chasing debts, with his wealth shrinking.

Peace celebrated in Paris

Peace celebrated in Paris

When the French Revolution brokeout in 1789, Beaumarchais supported its ideals but recoiled at its violence.Accused of hoarding arms, he fled to Germany, returning only afterRobespierre’s fall. He died in 1799, his life a whirlwind of victories and setbacks.

Storming the Bastille Launched the Revolution

Curtain Call

Beaumarchais saw America’s fightas a reflection of his own struggles against privilege and authority. His playsmocked the nobility; his guns supported the rebels. He was a man full ofcontradictions—a courtier who despised tyranny, a profiteer risking everythingfor a cause.

July 25, 2025

The Triple Agent

Paris, December 1776. The air was crisp with winter’s chill, and the Tuileries Gardens lay shadowed, their neat paths empty except for a single figure moving purposefully. Edward Bancroft, a doctor, scientist, and man of letters, slipped through the darkness, his breath fogging in the cold. In his coat pocket, a rolled letter to “Mr. Richards” rested, its ink written in a special code only the right eyes could decipher. To the world, Bancroft seemed to be a loyal American, a trusted aide to Benjamin Franklin. Still, tonight, as he approached a twisted box tree and slipped his message into a hollow, he played a different role: a spy for King George III.

Tuileries Gardens

Tuileries Gardens

Born in Westfield, Massachusetts, in 1744, Edward Bancroft moved to Connecticut with his widowed mother after she remarried David Bull. There he was tutored by none other than Silas Deane, the schoolteacher who would become our Deane of Spires—America’s agent in Paris.

Home in 18th-century Massachusetts

Home in 18th-century Massachusetts

Young Bancroft was a quick study,but he was restless. At sixteen, he gave up an apprenticeship with a doctor in Killingworth to seek adventure in Dutch Guiana or Suriname. There, he assumedthe mantle of a physician, treating plantation workers while pursuing his studyof the natural world. A fateful acquaintance was made when Paul Wentworth, awealthy plantation owner, hired Bancroft to survey his land. While there,Bancroft penned a semi-biographical novel as a homage to his employer, detailingthe life of a planter.

Celebrated Scientist

He made his way to London, where in 1769, his Essay on the Natural History of Guiana earned him recognition. He began calling himself “Doctor,” despite having no formal degree. He made the rounds in coffeehouses and intellectual salons, where he met Doctor Benjamin Franklin, the American colonial representative in London. Franklin recognized potential in Bancroft’s wit and worldly charm, and they soon became close friends. As the colonies moved down the road to rebellion, Bancroft’s pro-American writings—like his 1769 Remarks on the Review of the Controversy between Great Britain and Her Colonies—enhanced his patriot bona fides.

Ben Franklin: Mentor and Mark?

Ben Franklin: Mentor and Mark?

In 1771, Cupid’s arrow struck,and Bancroft married young Penelope Fellows, daughter of a prominent Catholicfamily. Ironic as Bancroft was, at best, a Deist. A son, Edward, was born in1772, and the couple went on to have six more children.

In 1776, Silas Deane arrived in Paris to seek French aid, as Congress’s representative (using a cover), he tapped his former student to help. Franklin, now an American commissioner, soon arrived, appointing his London acquaintance as secretary to the American delegation. To Deane and Franklin, Bancroft was a trusted employee, copying letters, translating dispatches, and organizing supplies for American ships. But beneath this front, a darker loyalty simmered—Bancroft was, in actuality, now a mole.

Silas Deane

Silas Deane

Before Bancroft left London for France,Paul Wentworth, now a recently recruited agent of the British Secret Service who ran a spy ring, approached him. Wentworth was an American-born loyalist who ran a British spy ring and had employed Bancroft when they were both living in Dutch Guiana. A meetingwas arranged with William Eden, the head of the Secret Service, and a deal was struck. For $ 200 a year—later increased to $500, then $1,000—Bancroft agreed tobetray his fellow Americans.

William Eden

William Eden

His motives were a mix of loyaltyto the British Empire, financial ambition, and doubt about the chances of Americanindependence. Believing that the colonies’ best future was within the Empire,he began a life in the shadows, engaging in a risky game—secretly passinginformation to the British while working for Franklin and Deane. In the spyparlance, he had perfect placement and access.

On Tuesday nights, Bancroft carried out his secret routine. Using the alias “Edward Edwards,” he penned reports to a “Mr. Richards,” using invisible ink while cleverly disguising his intelligence reports within stories of romantic escapades. Details about American negotiations with France, troop movements, and Franklin’s personal thoughts would be slipped into a bottle, tied with a string, and hidden in a hollow in a Tuileries tree after 9:30 p.m. When Bancroft cleared the area (departed), a British agent from the embassy would make the pickup, leaving new orders, which Bancroft would gather later that night. America’s secrets were in the hands of William Eden and King George III just two days later.

George III

George III Suspicious Colleague

Yet Bancroft’s game was filled with danger: Arthur Lee, an American diplomat, suspected betrayal. Of course, the prickly Virginian suspected everyone! Lee saw Bancroft’s stock speculations and rumored mistress as a red flag. He warned Franklin and Congress in 1778, claiming there was evidence of Bancroft’s treachery. “I consider Dr. Bancroft a Criminal concerning the United States,” Lee wrote. But he had no proof. Franklin remained loyal to his friend and dismissed them.

Arthur Lee

Arthur Lee

Bancroft caught wind of these accusations and warned his friends. To avoid suspicion, the British staged a fake arrest of Bancroft, accusing him of aiding the rebels—a ruse that kept his cover intact. Lee’s warnings diminished, and Bancroft’s deception remained hidden.

Bancroft’s actions were remarkable. He translated the commission’s correspondence, repaired American ships, and even advised John Paul Jones, all while passing secrets to London. In 1781, he stole Deane’s private letters, which revealed despair over America’s prospects and called for peace with Britain. Published in New York after Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, the stolen letters damaged Deane’s reputation, calling him a traitor.

John Paul Jones

John Paul Jones

After the war ended, Bancroft’s reputation continued to grow. In 1783, he moved to England to secure his British pension, while continuing to correspond with Franklin. Bancroft’s scientific work thrived; his 1794 book, Experimental Researches Concerning the Philosophy of Permanent Colors. This earned him a fellowship at the Royal Society, and his patents for quercitron dye made him a wealthy man. Our secretary, double and triple agent, moleand scientist, died on 7 September 1821, at Addington Place in Margate.

Edward Bancroft

Edward Bancroft

Was Bancroft a traitor to America or a patriot to Britain? The question hangs like fog over the Tuileries. Some historians suggest he was a British loyalist who truly believed in the Empire’s unity. Bancroft’s betrayal, though daring, did not destroy the American cause. Ironically, his intelligence, though detailed, often went unused by the British, who did not utilize his reports effectively. Why not? Did they suspect him of being a triple agent? Some speculate Franklin knew of his duplicity but let him operate under the adage of keeping friends close and enemies closer.

A Spy at Work?

A Spy at Work?

Whatever the truth, his espionage activities remained hidden until 1891, when British archives revealed his treachery, shocking historians and damaging his legacy. Regardless of who he betrayed, Bancroft’s spying, though daring, did not destroy the American cause. That might just provide our answer—or not. Such is the dilemma of traversing the wilderness of mirrors.

The Surinam Spy

Paris, December 1776. The air was crisp with winter’s chill, and the Tuileries Gardens lay shadowed, their neat paths empty except for a single figure moving purposefully. Edward Bancroft, a doctor, scientist, and man of letters, slipped through the darkness, his breath fogging in the cold. In his coat pocket, a rolled letter to “Mr. Richards” rested, its ink written in a special code only the right eyes could decipher. To the world, Bancroft seemed to be a loyal American, a trusted aide to Benjamin Franklin. Still, tonight, as he approached a twisted box tree and slipped his message into a hollow, he played a different role: a spy for King George III.

Tuileries Gardens

Tuileries Gardens

Born in Westfield, Massachusetts, in 1744, Edward Bancroft moved to Connecticut with his widowed mother after she remarried David Bull. There he was tutored by none other than Silas Deane, the schoolteacher who would become our Deane of Spires—America’s agent in Paris.

Home in 18th-century Massachusetts

Home in 18th-century Massachusetts

Young Bancroft was a quick study,but he was restless. At sixteen, he gave up an apprenticeship with a doctor in Killingworth to seek adventure in Dutch Guiana or Suriname. There, he assumedthe mantle of a physician, treating plantation workers while pursuing his studyof the natural world. A fateful acquaintance was made when Paul Wentworth, awealthy plantation owner, hired Bancroft to survey his land. While there,Bancroft penned a semi-biographical novel as a homage to his employer, detailingthe life of a planter.

Celebrated Scientist

He made his way to London, where in 1769, his Essay on the Natural History of Guiana earned him recognition. He began calling himself “Doctor,” despite having no formal degree. He made the rounds in coffeehouses and intellectual salons, where he met Doctor Benjamin Franklin, the American colonial representative in London. Franklin recognized potential in Bancroft’s wit and worldly charm, and they soon became close friends. As the colonies moved down the road to rebellion, Bancroft’s pro-American writings—like his 1769 Remarks on the Review of the Controversy between Great Britain and Her Colonies—enhanced his patriot bona fides.

Ben Franklin: Mentor and Mark?

Ben Franklin: Mentor and Mark?

In 1771, Cupid’s arrow struck,and Bancroft married young Penelope Fellows, daughter of a prominent Catholicfamily. Ironic as Bancroft was, at best, a Deist. A son, Edward, was born in1772, and the couple went on to have six more children.

In 1776, Silas Deane arrived in Paris to seek French aid, as Congress’s representative (using a cover), he tapped his former student to help. Franklin, now an American commissioner, soon arrived, appointing his London acquaintance as secretary to the American delegation. To Deane and Franklin, Bancroft was a trusted employee, copying letters, translating dispatches, and organizing supplies for American ships. But beneath this front, a darker loyalty simmered—Bancroft was, in actuality, now a mole.

Silas Deane

Silas Deane

Before Bancroft left London for France,Paul Wentworth, now a recently recruited agent of the British Secret Service who ran a spy ring, approached him. Wentworth was an American-born loyalist who ran a British spy ring and had employed Bancroft when they were both living in Dutch Guiana. A meetingwas arranged with William Eden, the head of the Secret Service, and a deal was struck. For $ 200 a year—later increased to $500, then $1,000—Bancroft agreed tobetray his fellow Americans.

William Eden

William Eden

His motives were a mix of loyaltyto the British Empire, financial ambition, and doubt about the chances of Americanindependence. Believing that the colonies’ best future was within the Empire,he began a life in the shadows, engaging in a risky game—secretly passinginformation to the British while working for Franklin and Deane. In the spyparlance, he had perfect placement and access.

On Tuesday nights, Bancroft carried out his secret routine. Using the alias “Edward Edwards,” he penned reports to a “Mr. Richards,” using invisible ink while cleverly disguising his intelligence reports within stories of romantic escapades. Details about American negotiations with France, troop movements, and Franklin’s personal thoughts would be slipped into a bottle, tied with a string, and hidden in a hollow in a Tuileries tree after 9:30 p.m. When Bancroft cleared the area (departed), a British agent from the embassy would make the pickup, leaving new orders, which Bancroft would gather later that night. America’s secrets were in the hands of William Eden and King George III just two days later.

George III

George III Suspicious Colleague

Yet Bancroft’s game was filled with danger: Arthur Lee, an American diplomat, suspected betrayal. Of course, the prickly Virginian suspected everyone! Lee saw Bancroft’s stock speculations and rumored mistress as a red flag. He warned Franklin and Congress in 1778, claiming there was evidence of Bancroft’s treachery. “I consider Dr. Bancroft a Criminal concerning the United States,” Lee wrote. But he had no proof. Franklin remained loyal to his friend and dismissed them.

Arthur Lee

Arthur Lee

Bancroft caught wind of these accusations and warned his friends. To avoid suspicion, the British staged a fake arrest of Bancroft, accusing him of aiding the rebels—a ruse that kept his cover intact. Lee’s warnings diminished, and Bancroft’s deception remained hidden.

Bancroft’s actions were remarkable. He translated the commission’s correspondence, repaired American ships, and even advised John Paul Jones, all while passing secrets to London. In 1781, he stole Deane’s private letters, which revealed despair over America’s prospects and called for peace with Britain. Published in New York after Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, the stolen letters damaged Deane’s reputation, calling him a traitor.

John Paul Jones

John Paul Jones

After the war ended, Bancroft’s reputation continued to grow. In 1783, he moved to England to secure his British pension, while continuing to correspond with Franklin. Bancroft’s scientific work thrived; his 1794 book, Experimental Researches Concerning the Philosophy of Permanent Colors. This earned him a fellowship at the Royal Society, and his patents for quercitron dye made him a wealthy man. Our secretary, double and triple agent, moleand scientist, died on 7 September 1821, at Addington Place in Margate.

Edward Bancroft

Edward Bancroft

Was Bancroft a traitor to America or a patriot to Britain? The question hangs like fog over the Tuileries. Some historians suggest he was a British loyalist who truly believed in the Empire’s unity. Bancroft’s betrayal, though daring, did not destroy the American cause. Ironically, his intelligence, though detailed, often went unused by the British, who did not utilize his reports effectively. Why not? Did they suspect him of being a triple agent? Some speculate Franklin knew of his duplicity but let him operate under the adage of keeping friends close and enemies closer.

A Spy at Work?

A Spy at Work?

Whatever the truth, his espionage activities remained hidden until 1891, when British archives revealed his treachery, shocking historians and damaging his legacy. Regardless of who he betrayed, Bancroft’s spying, though daring, did not destroy the American cause. That might just provide our answer—or not. Such is the dilemma of traversing the wilderness of mirrors.

June 26, 2025

Deane of Spies

July 1776. The Seine shone under a summer moon, its ripples hiding secrets as Silas Deane stepped onto the cobblestones of Place Louis XV. He looked back to see if he was being followed. Not this time. The Connecticut merchant-turned-diplomat, Deane’s role was crucial to the young rebellion—securing badly needed aid from France. Although not a polished diplomat, the Yankee trader, a skilled negotiator, was up against a city full of spies and schemers. He would have to wage a secret war for America’s survival, with betrayal waiting at every turn. Though only a passing figure in my novel, The Reluctant Spy, it’s important to understand Deane’s role, as he set the stage for much that followed.

Paris: a Maze of Intrigue

Paris: a Maze of IntrigueYoung Yankee

Who would have thought a young Connecticut Yankee would be drawn into the world of global espionage? Silas Deane was born in Groton in 1737. Fortunate enough to attend Yale, he eschewed the typical graduate’s career as a cleric, schoolmaster, or lawyer. Connecticut’s access to the sea and its favorable rivers made it a hub of trade, and Dean earned a fortune in trading timber and rum. As with all of his class and status, Deane was drawn into politics as the colonies slid toward revolution and was a stalwart member of the Continental Congress. His talent got him named America’s first envoy to France during the early days of the struggle. America needed everything: money, supplies, weapons, and munitions. And America needed them quickly. Armed only with a letter of introduction and a seasoned dealmaker’s grit, he sailed off on this desperate venture in March 1776.

Silas Deane

Silas Deane

Aware of the intrigue awaiting him (the canny Benjamin Franklin likely briefed him), he posed as a merchant in a modest apartment in a quiet part of Paris, not Versailles. From there, he undertook the daunting task of convincing France to throw in with the Americans, at a time when British General William Howe was unleashing a sea and land campaign that would drive the Americans from New York and the Jerseys. Neutral France would prove a hard nut to crack, officially. His task was complicated by the fact that the spy services of both France and Britain were watching this obscure American.

Rodrigue y Hortalez, Et Cie

Dean hit pay dirt when French Foreign Minister Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, connected Deane with a pesky clockmaker and renowned playwright, Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais. Beaumarchais secretly approached Vergennes about taking action to aid the Americans' struggle, but Vergennes would not risk British ire—at least not yet.

Beaumarchais

Beaumarchais

The roguish Beaumarchais had set up a front company, Rodrigue y Hortalez, a Spanish company, to smuggle goods to America. Dean jumped at the opportunity, negotiating the transfer of 200 cannons, 25,000 uniforms, and ammunition that kept the Continental Army alive through 1777. Ships slipped from Le Havre to American ports, their cargoes disguised as commercial goods. Each shipment was fraught with danger, as French ports swarmed with British spies, spreading gold to detect evidence of French perfidy. Exposure, being caught in flagrante delicto, could cause Vergennes to close the operation, leaving the American cause in mortal peril.

Covert Shipments Nurtured the Rebellion

Covert Shipments Nurtured the Rebellion

But the threat, as usual, was from within. Edward Bancroft, a former pupil of Deane, became his secretary, privy to all aspects of the operation and everything else Deane was up to. The problem was that Bancroft was a British agent who clandestinely fed information to the British embassy, ensuring details would arrive on King George’s ministers’ desks within days.

Edward Bancroft

Edward Bancroft

The Cause was looking weak, very weak, in late 1776, and the need for a formal alliance was growing increasingly separate. The Continental Congress decided to up the ante by sending a former American representative in London to help Deane. Benjamin Franklin was not just another envoy—he was possibly the most renowned man of the era and soon eclipsed Deane, who was more of a back-office operator. Franklin would soon take the lead in dealings with the French.

Talent Scout

But Deane was doing much more than kibbitzing with the aristocracy. He actively recruited talent for the Cause, sending large numbers of experienced (sometimes, not so) officers to serve in the Continental Army. Among them were the Marquis de Lafayette, Baron De Kalb, Casimir Pulaski, Baron von Steuben, Thomas Conway, and Philippe du Coudray. The latter brought heat on Deane when he ticked off Congress with demands for money and rank, and Conway would be controversial in many ways. Still, they did provide a shot of Vitamin B-12 in the butt of an Army struggling for experienced leaders. Deane also helped John Paul Jones, arranging the initial French support for Jones’s first raids in European waters.

Lafayette

Lafayette

When an American planter and scion of the aristocratic Lee family of Virginia entered the scene, clouds darkened over Deane. Newly arrived diplomat Arthur Lee distrusted Deane, accusing him of profiteering from supply contracts. Lee’s suspicions had some merit; Deane’s merchant instincts did lead him to dabble in stocks, blurring public duty and private gain. These accusations, though unproven, were a blight on his record. When the American victory at Saratoga in October 1777 made a formal alliance just a matter of time, Deane’s welcome had worn out. Congress took Lee’s allegations seriously and recalled the man whose efforts kept the Cause alive in its darkest hours.

Arthur Lee

Arthur Lee

When Deane arrived at the nation's capital in 1778, he was unprepared for the deluge. He had anticipated praise, but instead faced a grilling from Congress over his accounts. Unprepared, with incomplete records, he faltered. It worsened for him in 1781 when his private letters, expressing doubts about America’s chances and urging peace with Britain, were published.

Philadelphia Was Unwelcoming

Philadelphia Was Unwelcoming

Branded a traitor, Deane fled to Europe, living in exile in London and Ghent. Who stole them? Some point to Bancroft, but Lee cannot be ruled out. Deane’s final years were grim. In 1789, he died suddenly aboard a ship bound for America, possibly from poisoning. It was not until the 19th century that documents exonerated Deane from the charges against him, but by then his grim legacy was sealed in the minds of most Americans.

Meeting De Kalb and Lafayette

Meeting De Kalb and LafayetteGrim Legacy?

Deane, thrust into the shadowy world of diplomacy and skullduggery, did quite well until inside forces, a spy and an implacable political foe, undid him. Yet the record is clear. The canny businessman initiated the supply chain that would feed the Cause, recruited (mostly) good talent, and set the stage for Franklin, Adams, Jay, and others to complete the work of making Paris a second front in the war against Britain. Bancroft’s treachery, Lee’s vendetta, and Congress’s ingratitude crushed his legacy, but Deane’s work in Paris kept the American Revolution alive. As he stood by the Seine in 1776, gazing at a city that could make or break a nation, he could not foresee the cost—only that freedom demanded it.

May 31, 2025

The French Fox

Although action and intrigue are the hallmarks of the YankeeDoodle Spies series, the war was, in fact, mainly won through the latter.Intrigue, fortified by no small dose of guile, enabled the rebel Americancolonies to throw off the yoke of the British Empire. They also received alittle help from their friends, particularly a Frenchman who played the greatgame of international diplomacy through a mix of statesmanship, espionage, anddeception.

Charles Gravier, comte de Vergennes

Charles Gravier, comte de VergennesCharles Gravier,Comte de Vergennes, was a shrewd statesman who orchestrated a complex diplomatic strategy against France’s despised enemy, Great Britain. He maintained a calm andaccommodating demeanor with his opponents and even kept his friends and allieson their toes.

Burgundian RootsIt is almost ironic that this relentless foe of Britainoriginated from an ancient ally of the English and an adversary of France, theGrand Duchy of Burgundy. However, when Charles Gravier was born in Dijon on achilly December day in 1719, the region was merely a province of France.Gravier’s father was a local magistrate, respectable but not particularly highin the French social hierarchy.

Dijon, Capital of Burgundy

Dijon, Capital of BurgundyFollowing in his father’s footsteps, young Charles studiedlaw. Eschewing the military or clergy that ensnared so many sons of the elites,he entered the French diplomatic service at the age of twenty. Soon, hispatience, intellect, and knack for intrigue set him on a lifetime trajectorythat would change the world.

A Diplomat’s RiseVergennes’ earlyposts provided the training of a diplomat and a spy. His apprenticeship began inLisbon in 1740 during the heated years of the War of the Austrian Succession.He learned to read a room, assessing the strengths and weaknesses of couriers and diplomats—and their true intentions. Postings in Bavaria and the Palatinate followed. More challenging wasthe 1755 plum posting as ambassador to Istanbul (formerly Constantinople), where the Ottomans anddiplomats of the Russian Empire tested his wiles.

Istanbul

IstanbulExperience in the Byzantine world of the formerly Byzantine Ottoman Empire prepared him for later challenges, like Sweden in 1768. There, he facedhis Russian adversaries once more, employing a mix of charm, persuasion,espionage, and gold to keep the court’s pro-French party in power and the Swedes who favored Catherine the Great's Russia out.

Gravier: Ambassador to the Sublime Porte

Gravier: Ambassador to the Sublime PorteThese posts schooled Vergennes in the art of high (and low)diplomacy, and foreshadowed what the mastermind could do when he reached thenext level in the diplomatic corps.

Catherine the Great, Czarina of Russia

In the spring of 1775, the slow-burning insurrection in the American colonies erupted into a powder keg of revolutionary warfare. Evenfrom far-off Versailles, the canny Vergennes could smell opportunity, if notthe gun smoke. The catastrophic treaty ending the Seven Years’ War had tornaway France’s most valued colonies—Canada was gone, India had been diminished, the West Indies islands were lost, West Africa had been lost to Britain, and Louisiana was given to Spain ascompensation. France might not regain any of its lost colonies, but it sought revenge. The prickly American colonists now allowed Vergennes to bleed Britaindry.

Action at Lexington Brings War to America

Action at Lexington Brings War to AmericaVergennes was no friend of liberty. He played a power game,using the Yankees as his baseball bat. While Britain’s army and navy werebogged down, France had a chance to regain its power and prestige. Hedispatched agents to investigate the rebels. Were they tough enough to endure?Could they fight the world’s most powerful military? Vergennes wanted answersbefore he risked his nation.

Black OperationsWhen America’s first envoy, Silas Deane, turned up in Parisin 1776, with his hand out, looking for aid. Vergennes kept it low—he was notready to connect France to the rebellion. But a covert op might buy him time.When Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, a playwright with a sideline inskullduggery, approached him with a secret scheme to help America (and harm theAnglais), Vergennes consented. With Vergenneslooking the other way, he set up a fake trading outfit called RoderigueHortalez et Cie. This front company shipped muskets, powder, and cannons acrossthe ocean with tobacco and other cash crops sailing to France, where they'dsell and the profits then used to replace the French munitions and ordnance. At the same time, France had plausible deniability (it was a Spanish firm). Theports of France became smuggling hubs, with crates marked for “privatemerchants” ignored by French customs officials.

Beaumarchais: Playwright and Schemer

Beaumarchais: Playwright and SchemerEnter Doctor Franklin

The stakes grew higher when the most famous American in theworld, Benjamin Franklin, wandered into Paris in December 1776. Franklin’s furcap and homespun wit charmed and disarmed everyone from salon ladies to shopkeepers.Vergennes wisely let Franklin-mania work the crowd but kept the seriousbusiness behind closed doors. Despite Franklin's charm offensive, Gravierremained adamant. He would not risk an open alliance until the Americansproduced a major battlefield victory.

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin FranklinTurning Point

That came in October 1777. A British invasion from Canadawas smashed in two pitched battles, resulting in the surrender of the Britishat Saratoga, New York. Paris was a blaze when word of the triumph arrived. Forhis part, Vergennes now had proof of success and began coaxing the still-antsyKing Louis XVI to throw in with the American cause officially.

Turning Point: Saratoga Surrender

Turning Point: Saratoga SurrenderOn 6 February 1778, France and the United States signed twotreaties. The Treaty of Amity and Commerce primarily aimed to promote trade andcommercial relations between the two nations. The Treaty of Alliance establishedmilitary cooperation against Great Britain during the American RevolutionaryWar. Just like that, France was at war with Britain, and Vergennes was all in.But the ever-cautious King Louis delayed a public proclamation until Late March.

Signing the Treaty of Amity

Signing the Treaty of AmityThis war would be expensive, and Vergennes secretly pursuedsupport from Spain and the Netherlands. Despite diplomatic and secretmaneuverings, Spain did not join until 1779, with the stated goal of reclaiminglands lost to the British, specifically West Florida and Gibraltar, rather thanaiding the upstart Protestant rebels. Although they had been secretly lendingto the Americans, the Dutch did not join until 1780. Vergennes’ diplomatic tourde force had finally paid off.

City of SpiesParis during the Revolution rivaled Cold War-era Berlin as ahub of intrigue. Spies lurked in every tavern and salon, the British sniffingout American plans, the French tracking British agents, and Spain’s agentsgathering on behalf of His Catholic Majesty. Vergennes’s counterintelligencewas everywhere: surveilling diplomats, intercepting letters, and planting falseleads. One wolf in sheep’s clothing was Edward Bancroft, Franklin’s secretary, whowas feeding secrets to London. Despite his agents’ best efforts, Vergennes didnot uncover Bancroft’s treachery, which stayed hidden till later. Some believeFranklin was in on the treachery and exploited it.

Spy: Edward Bancroft

Spy: Edward BancroftFrance at War

Versailles was replete with naysayers on the alliance (perhapspersuaded with British gold), and they yapped at the always wobbly Louis. However,the Foreign Minister was now fully aligned with the Americans, ensuring that theflow of aid never stopped. But America’s real need was French military might,especially its navy. Despite some early fits and starts, when it came, itproved decisive.

Chesapeake: The French Fleet Played a Decisive Role

Chesapeake: The French Fleet Played a Decisive RoleNow was the time for the vengeance Vergennes struggled solong to achieve. Troops and ships sailedto the New World to join the Americans and exact that vengeance. Franco-Americanefforts faltered at Newport, Rhode Island, and Savannah, Georgia. Still, the1781 Yorktown campaign, where French troops and ships under Rochambeau and deGrasse sealed Cornwallis's troops on the York River in tidewater Virginia, wasthe brainchild of Vergennes.

A Separate PeaceThe surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown convinced theBritish that the game was over. But what they could not win on land and sea,they would try to win at the peace table. The spy-versus-spy atmosphere inParis intensified further when the British and American peace commissionersbegan sparring over the details, such as boundaries, fishing rights, tradingrights, western land ownership, and Indian affairs.

French Support Made Yorktown Possible

French Support Made Yorktown PossibleVergennes worked toalign the interests of France, Spain (a French ally, not an American one), and theUnited States during peace negotiations. He pushed for a unified approach toensure that the Americans coordinated with French interests. However, the Americans sometimes actedindependently, to Vergennes' frustration.

Peace of ParisVergennes spent most of his time on the broader peaceprocess. The Treaty of Paris was part of a series of agreements collectivelyknown as the Peace of Paris. That resolved the global conflicts among Britain,France, Spain, and the Netherlands. He negotiated terms for France, securingminor territorial gains (like Tobago and parts of Senegal) and protectingFrench interests in the West Indies and India.

Celebrating the Treaty of Peace with Britain in Paris

Celebrating the Treaty of Peace with Britain in ParisVergennes was leery of American commissioners skirtingFrench guidance. And with good reason.They signed a preliminary peace agreement with Britain in November 1782 withoutconsulting France fully and violating the terms of the 1778 alliance. Despitethis, Vergennes accepted the outcome, recognizing that American independencealigned with France’s overall goal of weakening Britain. Vergennes signed his own treaty with Britain the following year.

Cost of EmpireVergennes' service came at a cost. In 1781, King Louis appointed him as his Chief Minister, combining the roles of Foreign Minister and Prime Minister. Long days and nights oftoil and the pressure of orchestrating financial, diplomatic, intelligence, andeven military affairs strained him mentally and physically to the point where, onFebruary 13, 1787, he keeled over at 67. He passed away just as France’s war debts started fueling talk of revolution. Somesay Vergennes’ great gamble on America bankrupted France, which eventually ledto the French Revolution in 1789.

But hindsight is fifty-fifty. Charles Gravier’s goalwas to check British hegemony and restore French glory. To that end, hesucceeded. As for the French Revolution? Even the greatest and most perceptiveminds cannot see the future. Who in 1778 would have thought King Louis's support for America would ultimately result in a trip to the guillotine? But one might speculate that with him guiding the vacillating King Louis, the nation and the monarchy might have avoided the chaos of the French Revolution and the carnage that it brought to France and the world.

King Louis XVI

King Louis XVIAmericans owe a debt to Charles Gravier, Comte deVergennes—the man who viewed a ragged revolution as France’s opportunity. Hiscunning and insight were instrumental in America’s founding alongside theMinutemen and Continentals. Lauded neither in France nor America, the diplomatfrom Dijon played a pivotal role in the birth of a nation and changing theworld like few others have.

Alliance Rosette Worn By Continental Army Officers

Alliance Rosette Worn By Continental Army Officers

April 30, 2025

Lord in the Shadows

In the waning years of the 18th century, as the fires ofrebellion blazed across the Atlantic, William Eden, 1st Baron Auckland, stoodat the apex of Britain’s clandestine war. From his unassuming office in London,hidden behind the façade of bureaucratic mundanity, Eden orchestrated a web ofespionage that stretched from the drawing rooms of Westminster to the muddybattlefields of the American colonies. He was not a man of the sword, but ofthe quill and the whisper, a master of secrets whose name was known only to aselect few, yet whose influence shaped the course of empires.

Privileged YouthBorn in 1744, the son of a Durham baronet, William Eden’searly life was one of privilege and education. He became a legal scholar atEton and Christ Church, Oxford. In 1771, he published Principles of Penal Lawand became a recognized authority on commercial and economic questions. Yet hiskeen mind for strategy drew him into the shadowy world of intelligence. By thetime the American colonies began their murmurs of discontent, Eden had alreadyproven his worth in diplomatic circles, but it was his appointment as the headof the British Secret Service in 1776 that would define his legacy.

Eton CollegeSpy Master

Eton CollegeSpy MasterThe American War for Independence was not just a war of battlesand maneuvers but also an intelligence war. Eden understood this better thanmost. While Secretary of State for the Colonies Lord George Germain plotted grand strategy and generals like Sir WilliamHowe and Lord Charles Cornwallis planned campaigns, Eden waged a silent war,fought with coded letters, double agents, and quiet betrayals. His office,tucked away in a nondescript building near St. James’s, was a nerve center ofespionage. Maps of the colonies, intercepted dispatches, and lists of suspectedrebel sympathizers and agents lay stacked on his desk. Each provided a clue inthe vast canvas of rebellion he sought to undo. To accomplish this, theintelligence budget soared to some £200,000 during this period! That’s about £40,706,380in 2025 money, adjusted for inflation.

George GermainReading “Traffic”

George GermainReading “Traffic”Eden began his mornings reviewing reports from his networkof spies, many of whom operated under the cover of merchants, clergymen, oreven Loyalist sympathizers in the colonies. Spies embedded deep within theContinental Army could feed details of troop movements and supply shortagesthat would make their way to London. Spies in the rebel capital worked in thesocial circles of Philadelphia and developed political information throughelicitation and observation. Eden read dispatches with a meticulous eye, hisquill scratching notes in the margins, decoding the hidden meanings behindtheir carefully chosen words.

Reading Traffic

Reading TrafficThe Cocktail Party Circuit

Eden’s evenings were spent in the company of the powerful,attending dinners and balls where the fate of the empire was often decided overport and cigars. He was a master of subtlety, his conversations laced withdouble meanings, his questions probing yet innocuous. At one such gathering,hosted by Lord North, Eden overheard a whispered conversation between twoFrench diplomats, hinting at their plans to escalate support for the rebels.The next day, a coded message was dispatched to a British agent in Paris,tasked with uncovering the details of the French plot.

Diplomats Sharing ConfidencesPolitico & Envoy

Diplomats Sharing ConfidencesPolitico & EnvoyIn 1778, Eden, as a Member of Parliament, introduced an Actto improve the treatment of prisoners of war, which caused some controversy asAmerican captives were often regarded as traitors, not war prisoners. He also organized, arranged, and accompaniedthe Earl of Carlisle as a commissioner to North America in a failed attempt toend the American War of Independence through negotiation. On his return in 1779,he published his widely read Four Letters to the Earl of Carlisle. This work discussed the ongoing war with theAmerican colonies, France, and Spain, advocating for continued military effortsto crush colonial resistance. Eden also examines public debts, credit, andsupply-raising methods, alongside Ireland’s push for free trade, reflecting oneconomic and imperial policies.

The Earl of CarlisleA Spy’s Home Life

The Earl of CarlisleA Spy’s Home LifeYet, for all his successes, Eden was not immune to theweight of his responsibilities. The war was a personal and political struggle,and the constant stream of betrayals, failures, and losses took their toll. Hewed Eleanor Elliot, of the influential Elliot family. She and their six sons and eight daughtersprovided some solace, but even in the quiet moments at home, his mind was neverfar from the war. Eden would sit by the fire, a glass of Madeira in hand, hiseyes fixed on the flames as he pondered the next move in the deadly game ofchess he played with the rebels.

Eden's First Daughter, Eleanor AgnesThe Great Game

Eden's First Daughter, Eleanor AgnesThe Great GameBut Eden’s most significant challenge was collectingintelligence in the one place the war would be won or lost—Paris. The British orchestratedintelligence operations against the American commissioners, the Frenchgovernment, and the Spanish and Dutch representatives. While British diplomatsand agents were also active in all the major European capitals, Paris was thepolitical center of gravity in the game being played out. Spies were recruited and“run” against all parties, with the American Commission in Passy and BenjaminFranklin himself a target. His agents spread disinformation to undermine Frenchconfidence in the American cause or delay their military commitments, thoughwith limited success given France’s strategic commitment.

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin FranklinEden tracked negotiations between French Foreign MinisterCharles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, and American representatives like BenjaminFranklin. The goal was to influence the French and Spanish from officiallyjoining the Americans in war with Britain. But in 1778, France threw her hatinto the ring and signed a formal treaty of Amity and Alliance with the UnitedStates. Britain did manage to slow Spain’s entry into the conflict, buteventually that too would fail.

Spies Among UsOne of the darkest moments of Eden’s tenure came in 1781, asthe war neared its climax. The British surrender at Yorktown was a blow to the army and Eden’s carefully constructed network. Many of hisagents were exposed or captured, their identities betrayed by a mole within theSecret Service itself. Eden’s investigation into the breach was ruthless; hisinterrogations were conducted in the cold, stone-walled chambers beneath hisoffice. The traitor, a junior clerk with gambling debts and a taste for Frenchgold, was quietly dealt with, his fate sealed in a manner that left no trace.

Surrender at YorktownManaging Defeat