The Surinam Spy

Paris, December 1776. The air was crisp with winter’s chill, and the Tuileries Gardens lay shadowed, their neat paths empty except for a single figure moving purposefully. Edward Bancroft, a doctor, scientist, and man of letters, slipped through the darkness, his breath fogging in the cold. In his coat pocket, a rolled letter to “Mr. Richards” rested, its ink written in a special code only the right eyes could decipher. To the world, Bancroft seemed to be a loyal American, a trusted aide to Benjamin Franklin. Still, tonight, as he approached a twisted box tree and slipped his message into a hollow, he played a different role: a spy for King George III.

Tuileries Gardens

Tuileries Gardens

Born in Westfield, Massachusetts, in 1744, Edward Bancroft moved to Connecticut with his widowed mother after she remarried David Bull. There he was tutored by none other than Silas Deane, the schoolteacher who would become our Deane of Spires—America’s agent in Paris.

Home in 18th-century Massachusetts

Home in 18th-century Massachusetts

Young Bancroft was a quick study,but he was restless. At sixteen, he gave up an apprenticeship with a doctor in Killingworth to seek adventure in Dutch Guiana or Suriname. There, he assumedthe mantle of a physician, treating plantation workers while pursuing his studyof the natural world. A fateful acquaintance was made when Paul Wentworth, awealthy plantation owner, hired Bancroft to survey his land. While there,Bancroft penned a semi-biographical novel as a homage to his employer, detailingthe life of a planter.

Celebrated Scientist

He made his way to London, where in 1769, his Essay on the Natural History of Guiana earned him recognition. He began calling himself “Doctor,” despite having no formal degree. He made the rounds in coffeehouses and intellectual salons, where he met Doctor Benjamin Franklin, the American colonial representative in London. Franklin recognized potential in Bancroft’s wit and worldly charm, and they soon became close friends. As the colonies moved down the road to rebellion, Bancroft’s pro-American writings—like his 1769 Remarks on the Review of the Controversy between Great Britain and Her Colonies—enhanced his patriot bona fides.

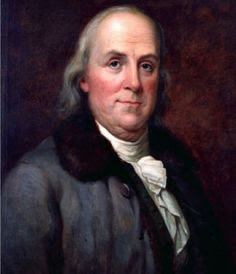

Ben Franklin: Mentor and Mark?

Ben Franklin: Mentor and Mark?

In 1771, Cupid’s arrow struck,and Bancroft married young Penelope Fellows, daughter of a prominent Catholicfamily. Ironic as Bancroft was, at best, a Deist. A son, Edward, was born in1772, and the couple went on to have six more children.

In 1776, Silas Deane arrived in Paris to seek French aid, as Congress’s representative (using a cover), he tapped his former student to help. Franklin, now an American commissioner, soon arrived, appointing his London acquaintance as secretary to the American delegation. To Deane and Franklin, Bancroft was a trusted employee, copying letters, translating dispatches, and organizing supplies for American ships. But beneath this front, a darker loyalty simmered—Bancroft was, in actuality, now a mole.

Silas Deane

Silas Deane

Before Bancroft left London for France,Paul Wentworth, now a recently recruited agent of the British Secret Service who ran a spy ring, approached him. Wentworth was an American-born loyalist who ran a British spy ring and had employed Bancroft when they were both living in Dutch Guiana. A meetingwas arranged with William Eden, the head of the Secret Service, and a deal was struck. For $ 200 a year—later increased to $500, then $1,000—Bancroft agreed tobetray his fellow Americans.

William Eden

William Eden

His motives were a mix of loyaltyto the British Empire, financial ambition, and doubt about the chances of Americanindependence. Believing that the colonies’ best future was within the Empire,he began a life in the shadows, engaging in a risky game—secretly passinginformation to the British while working for Franklin and Deane. In the spyparlance, he had perfect placement and access.

On Tuesday nights, Bancroft carried out his secret routine. Using the alias “Edward Edwards,” he penned reports to a “Mr. Richards,” using invisible ink while cleverly disguising his intelligence reports within stories of romantic escapades. Details about American negotiations with France, troop movements, and Franklin’s personal thoughts would be slipped into a bottle, tied with a string, and hidden in a hollow in a Tuileries tree after 9:30 p.m. When Bancroft cleared the area (departed), a British agent from the embassy would make the pickup, leaving new orders, which Bancroft would gather later that night. America’s secrets were in the hands of William Eden and King George III just two days later.

George III

George III Suspicious Colleague

Yet Bancroft’s game was filled with danger: Arthur Lee, an American diplomat, suspected betrayal. Of course, the prickly Virginian suspected everyone! Lee saw Bancroft’s stock speculations and rumored mistress as a red flag. He warned Franklin and Congress in 1778, claiming there was evidence of Bancroft’s treachery. “I consider Dr. Bancroft a Criminal concerning the United States,” Lee wrote. But he had no proof. Franklin remained loyal to his friend and dismissed them.

Arthur Lee

Arthur Lee

Bancroft caught wind of these accusations and warned his friends. To avoid suspicion, the British staged a fake arrest of Bancroft, accusing him of aiding the rebels—a ruse that kept his cover intact. Lee’s warnings diminished, and Bancroft’s deception remained hidden.

Bancroft’s actions were remarkable. He translated the commission’s correspondence, repaired American ships, and even advised John Paul Jones, all while passing secrets to London. In 1781, he stole Deane’s private letters, which revealed despair over America’s prospects and called for peace with Britain. Published in New York after Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, the stolen letters damaged Deane’s reputation, calling him a traitor.

John Paul Jones

John Paul Jones

After the war ended, Bancroft’s reputation continued to grow. In 1783, he moved to England to secure his British pension, while continuing to correspond with Franklin. Bancroft’s scientific work thrived; his 1794 book, Experimental Researches Concerning the Philosophy of Permanent Colors. This earned him a fellowship at the Royal Society, and his patents for quercitron dye made him a wealthy man. Our secretary, double and triple agent, moleand scientist, died on 7 September 1821, at Addington Place in Margate.

Edward Bancroft

Edward Bancroft

Was Bancroft a traitor to America or a patriot to Britain? The question hangs like fog over the Tuileries. Some historians suggest he was a British loyalist who truly believed in the Empire’s unity. Bancroft’s betrayal, though daring, did not destroy the American cause. Ironically, his intelligence, though detailed, often went unused by the British, who did not utilize his reports effectively. Why not? Did they suspect him of being a triple agent? Some speculate Franklin knew of his duplicity but let him operate under the adage of keeping friends close and enemies closer.

A Spy at Work?

A Spy at Work?

Whatever the truth, his espionage activities remained hidden until 1891, when British archives revealed his treachery, shocking historians and damaging his legacy. Regardless of who he betrayed, Bancroft’s spying, though daring, did not destroy the American cause. That might just provide our answer—or not. Such is the dilemma of traversing the wilderness of mirrors.