Bob Marshall's Blog

September 19, 2025

This Company Eliminated All Managers and Turned Every Product Team Into a Profitable Startup

Whilst most tech companies are debating the merits of OKRs versus alternative goal-setting frameworks, a Chinese appliance manufacturer has been quietly running one of the world’s most radical organisational experiments. Haier’s “Rendanheyi” model—which translates roughly to “inverted triangle of individual-goal combination”—has transformed a near-bankrupt refrigerator company into a global giant by eliminating traditional management and replacing it with market-driven entrepreneurship.

But could this model work for software development organisations? The answer might surprise you.

What Is Rendanheyi?Rendanheyi flips traditional corporate structure on its head. Instead of hierarchical departments managed through cascading objectives, Haier operates as an ecosystem of thousands of small, autonomous business units called “self-managed teams” or SMTs. Each unit:

Operates as an independent business with full P&L responsibilityServes real customers (either external customers or other internal units)Buys and sells services from other units at market ratesShares in financial outcomes through profit-sharing and ownership stakesHas direct access to resources without middle management gatekeepingThe result? No middle managers, no annual planning cycles, no OKRs—just market forces driving alignment and accountability.

Why Traditional Goal-Setting Falls Short in Software DevelopmentBefore exploring how Rendanheyi might apply to software organisations, it’s worth acknowledging why conventional approaches often struggle:

The Innovation Problem: OKRs assume you can predict what success looks like. But breakthrough software products often emerge from experimentation that defies predetermined key results.

The Measurement Trap: Software development involves significant creative and problem-solving work that’s difficult to capture in quarterly metrics. Teams often end up optimising for what’s measurable rather than what’s valuable.

The Speed Penalty: Complex goal-setting processes add overhead and delay decision-making in an industry where speed to market is crucial.

The Scaling Challenge: As software organisations grow, maintaining alignment through cascading objectives becomes increasingly bureaucratic and disconnected from actual customer value.

Rendanheyi in Software: The Natural FitSoftware development organisations might actually be ideal candidates for Rendanheyi-style transformation, for several reasons:

Digital Products Enable Clean Unit SeparationUnlike manufacturing, where supply chains create complex interdependencies, software products can often be cleanly separated into distinct services, features, or platforms. A music streaming service, for example, could organise around units like:

Recommendation Engine Team (sells personalised playlists to other units)Audio Infrastructure Team (provides streaming services to product teams)Mobile Experience Team (builds customer-facing apps, buys services from backend teams)Analytics Platform Team (sells data insights to all other units)Natural Market Pricing MechanismsSoftware organisations already use internal concepts that mirror market pricing:

Infrastructure costs (AWS bills, computational resources)Engineering time (sprint capacity, story points)User engagement metrics (DAU, retention, conversion rates)These existing metrics could form the basis of an internal market where teams buy and sell services from each other.

Rendanheyi Through the Lens of QuintessenceThe “Quintessence” framework—which describes the ideal software development organisation—provides a compelling lens through which to evaluate Haier’s model. The alignment is remarkably strong, suggesting that Rendanheyi might represent one of the closest real-world implementations of quintessential organisational principles.

Strong Convergence AreasElimination of Traditional Management: Both Rendanheyi and Quintessence completely reject traditional hierarchical management. The quintessential organisation has “no managers” and emphasises that people doing the work should own “the way the work works.” Haier’s elimination of middle management and direct connection between autonomous units mirrors this perfectly.

Flow Over Silos: Quintessence emphasises horizontal value streams rather than vertical departmental structures. Haier’s approach of organising around customer-facing business units rather than functional departments aligns with this principle of organising around value flow rather than organisational convenience.

Trust and Autonomy: Both frameworks treat people as capable adults rather than resources to be controlled. Theory-Y assumptions about human nature—that people find joy in collaborative work and naturally take ownership—align with Haier’s trust in unit leaders to make entrepreneurial decisions.

Distributed Decision-Making: Quintessence advocates for the “Advice Process” and pushing decisions to where information originates. Haier’s model of autonomous decision-making within market constraints serves a similar function.

Key Tensions and Philosophical DifferencesMarket Mechanisms vs. Needs-Based Coordination: This represents the most interesting tension. Haier uses internal markets and P&L responsibility as coordination mechanisms, whilst Quintessence emphasises collaborative attention to “folks’ needs” through dialogue and consensus. However, these approaches might be more complementary than contradictory—internal markets serve as a mechanism for surfacing and meeting stakeholder needs.

Individual vs. Collective Accountability: Haier emphasises individual entrepreneurial ownership within small units, whilst Quintessence explicitly prefers group accountability and rejects “single wringable neck” approaches. Though Haier’s focus on small teams (10-15 people) somewhat bridges this gap.

Financial Incentives: Haier relies heavily on profit-sharing and market-based rewards, whilst Quintessence views extrinsic motivation sceptically, preferring intrinsic motivation through purpose, mastery, and autonomy. This represents a fundamental difference in assumptions about what motivates human behaviour.

Assessment: 75-85% AlignmentHaier achieves remarkable alignment with Quintessence principles—perhaps 75-85%—which is extraordinary for any large-scale implementation. The core philosophy of trusting people, eliminating bureaucracy, focusing on customer value, and enabling self-organisation aligns strongly.

The main gaps centre around Quintessence’s emphasis on nonviolence, psychology, and broader stakeholder consideration beyond customers and profits. Haier’s internal market mechanisms, whilst effective, might create competitive pressures that Quintessence would view as potentially harmful to interpersonal relationships.

Learning from Toyota’s Chief Engineer ModelToyota’s Chief Engineer (CE) system offers another organisational model worth considering alongside Rendanheyi. The CE has complete responsibility for a vehicle programme from conception through production, coordinating across functional departments without formal authority over the specialists involved.

Key aspects of Toyota’s model that complement Rendanheyi thinking:

Cross-Functional Integration: The CE integrates expertise from multiple disciplines—similar to how Haier’s business units must coordinate across traditional functional boundaries.

Responsibility Without Authority: The CE must influence and coordinate without commanding—developing skills in consensus-building and collaborative decision-making that would serve software organisations well.

Long-Term Product Ownership: Unlike project-based structures, the CE maintains responsibility throughout the product lifecycle, similar to how Haier units maintain ongoing customer relationships.

Market-Driven Decisions: The CE makes trade-offs based on customer needs and market constraints rather than internal politics or resource optimisation.

For software organisations, a hybrid approach might combine Haier’s entrepreneurial autonomy with Toyota’s integration model—autonomous product teams with designated integrators responsible for cross-team coordination and long-term product vision.

Built-in Customer Feedback LoopsSoftware development organisations already have rapid feedback mechanisms through user analytics, A/B testing, and deployment metrics. This real-time customer data will drive market dynamics more effectively than quarterly OKR reviews.

A Rendanheyi Software Organisation in PracticeImagine a mid-sized SaaS company reorganising around Rendanheyi principles:

Team StructureInstead of traditional engineering, product, and design departments, the company forms customer-focused units:

Onboarding Experience Squad (responsible for new user activation)Core Platform Team (provides APIs and infrastructure services)Enterprise Features Unit (builds B2B functionality)Growth Engine Team (drives user acquisition and retention)Internal Market DynamicsTeams operate on market principles:

The Growth Engine Team “buys” A/B testing infrastructure from the Core Platform Team at rates based on computational costs and engineering timeThe Enterprise Features Unit “pays” the Onboarding Squad based on how many enterprise customers successfully complete setupTeams can choose to build internally or “buy” from other teams based on cost and qualityProfit and Loss ResponsibilityEach unit tracks financial performance:

Revenue attribution: Customer subscription revenue is attributed to teams based on feature usage and customer feedbackCost allocation: Infrastructure, support, and development costs are allocated based on actual resource consumptionProfit sharing: Teams share in the financial success of their contributionsAutonomous Decision MakingTeams make independent choices about:

Technology stack and architecture decisionsHiring and team compositionFeature priorities based on customer valueWhether to build, buy, or partner for new capabilitiesThe Benefits for Software DevelopmentThis approach could solve several persistent challenges in software organisations:

Faster Innovation: Teams can experiment and pivot without waiting for approval or updating company-wide roadmaps.

Better Customer Focus: When teams’ success is directly tied to customer value rather than internal metrics, product decisions improve.

Natural Scaling: As the organisation grows, new teams can form organically around customer needs rather than requiring top-down reorganisation.

Reduced Bureaucracy: No need for complex planning processes, alignment meetings, or quarterly business reviews.

Talent Retention: Engineers and designers get entrepreneurial ownership and direct impact on business outcomes.

The Challenges and ConsiderationsHowever, implementing Rendanheyi in software development isn’t without significant challenges:

Technical Architecture RequirementsSoftware systems would need to be architected for independence:

Microservices architecture to enable teams to deploy independentlyClear API boundaries to facilitate internal marketsRobust monitoring and billing to track resource usage across teamsCultural TransformationThe shift from employee to entrepreneur mindset is profound:

Risk tolerance: Team members must be comfortable with financial accountabilityCollaboration vs. competition: Internal markets could create unhealthy competition between teamsLeadership development: Teams need entrepreneurial skills, not just technical expertiseMeasurement and Pricing ComplexityCreating fair internal markets is challenging:

How do you price shared infrastructure like security, compliance, or platform services?What happens to teams working on foundational technology that doesn’t directly drive revenue?How do you handle cross-team dependencies that don’t fit clean market models?Regulatory and Compliance ConstraintsSoftware companies often face regulatory requirements that don’t align with fully autonomous units:

Data privacy regulations may require centralised oversightSecurity standards might mandate consistent practices across teamsFinancial reporting may require traditional departmental structuresImplementation Strategies for Software OrganisationsFor software companies interested in experimenting with Rendanheyi principles, here are some practical starting points:

Start with Product TeamsBegin by giving product development teams more autonomy and P&L visibility. Let them make technology choices, prioritise features based on customer data, and share in the financial outcomes of their work.

Create Internal Service MarketsIdentify shared services (infrastructure, design systems, analytics) and experiment with market-based allocation. Let teams choose between building internally or “buying” from shared service teams.

Implement Transparent Cost AllocationMake infrastructure costs, engineering time, and other resources visible to teams. Start charging teams for their actual resource consumption rather than treating these as free shared resources.

Develop Customer-Centric MetricsMove beyond engineering metrics (story points, velocity) to customer value metrics (feature adoption, customer satisfaction, revenue attribution).

Experiment with Team FormationAllow teams to form organically around customer problems or business opportunities rather than maintaining static organisational boundaries.

The Future of Software OrganisationRendanheyi represents a fundamentally different approach to organisational design—one that treats internal operations like external markets and replaces management hierarchy with entrepreneurial ownership. For software development organisations facing scaling challenges, innovation bottlenecks, and talent retention issues, it offers a compelling alternative to traditional approaches.

Whilst full implementation requires significant commitment and cultural change, the principles behind Rendanheyi—customer focus, market accountability, entrepreneurial ownership, and autonomous decision-making—can be adopted incrementally by forward-thinking software organisations.

The question isn’t whether your next quarterly planning cycle should use OKRs or another goal-setting framework. The question is whether you’re ready to move beyond goal-setting entirely and trust market forces to drive alignment and performance.

For software organisations willing to make this leap, the rewards could be transformational: faster innovation, better customer outcomes, and a more engaged, entrepreneurial workforce that thinks like owners because they actually are owners.

The future of software development might not look like traditional corporate hierarchies at all. It might look more like a marketplace of entrepreneurial teams, competing and collaborating to create customer value. And that future might be closer than we think.

Further ReadingHamel, G. (2011). The big idea: First, let’s fire all the managers. Harvard Business Review, December 2011.

Hamel, G., & Zanini, M. (2020). Humanocracy: Creating organizations as amazing as the people inside them. Harvard Business Review Press.

Marshall, R. W. (2021). Quintessence: An acme for software development organisations. Falling Blossoms. [Available on Leanpub]

Hamel, G., & Zanini, M. (2018). The end of bureaucracy. Harvard Business Review, November-December 2018.

Kennedy, M. N. (2003). Product development for the lean enterprise: Why Toyota’s system is four times more productive and how you can implement it. Oaklea Press.

Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Riverhead Books.

Reinertsen, D. G. (2009). The principles of product development flow: Second generation lean product development. Celeritas Publishing.

Sobek, D. K., Ward, A. C., & Liker, J. K. (1999). Toyota’s principles of set-based concurrent engineering. MIT Sloan Management Review, 40(2), 67-83.

September 17, 2025

Why Curiosity Beats Shame in Software Retrospectives

There’s a moment in therapy that therapists call ‘the shift’—when you stop drowning in your patterns and start watching them with fascination. You realise you’ve been having the same argument with your partner for three years, and instead of feeling like a broken record, you start laughing. ‘Oh, there I go again, catastrophising about the dishes.’ The pattern doesn’t vanish overnight, but something fundamental changes: you’re no longer at war with yourself.

What if software teams could experience this same shift?

The Drama We Know By HeartEvery team has their recurring drama. Maybe it’s the sprint planning meeting that always runs two hours over because nobody can agree on story points. Perhaps it’s the deployment Friday that inevitably becomes deployment Monday because ‘just one small thing’ broke. Or the code review discussions that spiral into philosophical debates about variable naming or coding standards more generally, whilst the actual logic bugs slip through unnoticed.

We know these patterns intimately. We’ve lived them dozens of times. Yet most teams approach retrospectives like a tribunal, armed with post-its and grim determination to ‘fix our dysfunction once and for all.’ We dissect our failures with the energy of surgeons operating on ourselves, convinced that enough shame and analysis will finally make us different people.

But what if we’re approaching this backwards?

The Mice Would Find Us FascinatingDouglas Adams had it right when he suggested that mice might be the truly intelligent beings, observing human behaviour with scientific curiosity. Imagine if we could watch our team dynamics the way those hyperintelligent mice observe us—with detached fascination rather than existential dread.

‘Interesting,’ the mice might note. ‘When the humans feel time pressure, they consistently skip the testing phase, then spend three times longer fixing the resulting problems. They repeat this behaviour with remarkable consistency, despite claiming to have “learned their lesson” each time.’

The mice wouldn’t judge us. They’d simply observe the pattern, maybe take some notes, perhaps adjust their experiment parameters. They wouldn’t waste energy being disappointed in human nature.

The Science of Predictable IrrationalityBehavioural economists like Dan Ariely have spent decades documenting how humans make decisions in ways that are wildly irrational but remarkably consistent. We’re predictably bad at estimating time, systematically overconfident in our abilities, and reliably influenced by factors we don’t even notice. These aren’t bugs in human cognition—they’re features that served us well in evolutionary contexts but create interesting challenges in modern day work environments.

Software teams exhibit these same patterns at scale. We consistently underestimate complex tasks (planning fallacy), overvalue our current approach versus alternatives (status quo bias), and make decisions based on whoever spoke last in the meeting (recency effect). The beautiful thing is that once you name these patterns, they become less mysterious and more laughable.

Curiosity as a Debugging ToolWhen we approach our team patterns with curiosity instead of judgement, something magical happens. The defensive walls come down. Instead of ‘Why do we always screw this up?’ we start asking ‘What conditions reliably create this outcome?’

This shift from shame to science transforms retrospectives from group therapy sessions into collaborative debugging. We’re not broken systems that need fixing—we’re complex systems exhibiting predictable behaviours under certain conditions. Complex systems can be better understood through observation, and sometimes influenced through small experiments, though the outcomes are often unpredictable

Consider the team that always underestimates their stories. The shame-based approach produces familiar results: ‘We need to be more realistic about our estimates.’ (Spoiler alert: they won’t be.) The curiosity-based approach asks different questions: ‘What happens right before we make these optimistic estimates? What information are we missing? What incentives and other factors are shaping our behaviour?’

The Hilariously Predictable HumansOnce you start looking for patterns with curiosity, they become almost endearing. The senior developer who always says ‘this should be quick’ right before disappearing into a three-day rabbit hole. The product manager who swears this feature is ‘simple’ whilst gesturing vaguely at convoluted requirements that would make a vicar weep. The team that collectively suffers from meeting amnesia, forgetting everything discussed five seconds after the meeting ends.

These aren’t character flaws to be eliminated. They’re what Dan Ariely would call ‘predictably irrational’ behaviours—systematic quirks in how humans process information and make decisions. The senior developer genuinely believes it will be quick because they’re anchored on the happy path scenario (classic anchoring bias). The product manager sees simplicity because they’re viewing it through the lens of user experience, not implementation complexity (curse of knowledge in reverse). The team forgets meeting details because our brains are optimised for pattern recognition, not information retention across context switches.

We’re not broken. We’re just predictably, irrationally human.

Practical Curiosity: Retrospective Questions That TransformInstead of ‘What went wrong this sprint?’ you might like to try:

‘What hilariously predictable human things did we do again?’‘If we were studying ourselves from the outside, what would be fascinating about our behaviour?’‘What patterns are we executing so consistently that we could almost set our watches by them?’‘Under what conditions do we make our most questionable decisions?’What shared assumptions inevitably led to this sprint’s outcomes?‘What would the mice find interesting about how we work?’These questions invite observation rather than judgement. They make space for laughter, which is the enemy of shame. And they reduce the role of shame—the antithesis of learning.

The Liberation of Accepting Our ProgrammingHere’s the paradox: accepting our patterns makes them easier to change. When we stop fighting our humanity and start working with it, we find leverage points we never noticed before.

The team that always underestimates might not become perfect estimators, but they can build buffers into their process (Cf. TOC). The developer who disappears into rabbit holes can set timers and check-in points (such as Pomodoros). The product manager can be paired with someone who thinks in implementation terms.

We don’t have to become different people. We just have to become people who understand ourselves better.

AI as a Curiosity AmplifierHere’s where artificial intelligence might genuinely help—not as a problem-solver, but as a curiosity amplifier. AI excels at exactly the kind of pattern recognition that’s hard for humans trapped inside their own systems.

Pattern Recognition Beyond Human Limits

AI could spot correlations across longer timeframes than teams naturally track. Perhaps story underestimation always happens more, or less, after certain types of client calls, or when specific team members are on holiday. Maybe over-architecting solutions correlates with unclear requirements, or planning meetings grow longer when the previous sprint’s velocity dropped.

These are the kinds of subtle, multi-factor patterns that human memory and attention struggle with, but that could reveal fascinating insights about team behaviour.

Systematic Curiosity Drilling

More intriguingly, AI could help teams ask better layered questions: ‘We always over-architect when requirements are vague → What specific types of vagueness trigger this? → What makes unclear requirements feel threatening? → What would need to change to make simple solutions feel safe when requirements are evolving?’

This is the kind of systematic curiosity that therapists use—moving from ‘this is problematic’ to ‘this is interesting, let’s understand the deep logic.’ AI could be brilliant at sustaining that investigation without getting distracted or defensive.

The Crucial Cautions

But here’s what AI absolutely cannot do: the therapeutic shift itself. The moment of laughing at your patterns instead of being tormented by them? That’s irreplaceably human. AI risks creating surveillance anxiety—the sense that someone (or something) is always watching and judging.

There’s also the fundamental risk of reinforcing the very ‘fix the humans’ mentality this approach seeks to avoid. AI pattern recognition could easily slide back into ‘here are your dysfunctions, now optimise them away.’

The sweet spot might be AI as a very patient, non-judgmental research assistant—helping teams investigate their own behaviour more thoroughly. The humans still have to do the laughing, the accepting, and the choosing. But AI could make the curiosity richer and more evidential.

Just remember: the mice observed the humans with detached fascination, not with algorithms for improvement.

The Recursive GiftThe most beautiful part of this approach is that it’s recursive. Once your team learns to observe its patterns with curiosity, you’ll start applying this same gentle scrutiny to your retrospectives themselves. You’ll notice when you slip back into judgement mode and laugh about it. You’ll develop patterns for catching patterns.

You’ll become a team that’s as interested in how you think as in what you build. And that might be the most valuable code you ever debug.

The Pattern That Doesn’t DisappearYour recurring drama won’t vanish. The sprint planning will probably still run long sometimes. The ‘quick fix’ will occasionally become a weekend project. But your relationship to these patterns will transform. You’ll work on them without the crushing weight of believing you should be different than you are.

And in that space—between pattern and judgement, between observation and criticism—you’ll find something remarkable: the room to actually change.

The mice would be proud.

Further ReadingAdams, D. (1979). The hitchhiker’s guide to the galaxy. Harmony Books.

Ariely, D. (2008). Predictably irrational: The hidden forces that shape our decisions. Harper.

Netó, D., Oliveira, J., Lopes, P., & Machado, P. P. (2024). Therapist self-awareness and perception of actual performance: The effects of listening to one recorded session. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process and Outcome, 27(1), 722. https://doi.org/10.4081/ripppo.2024.722

Williams, E. N. (2008). A psychotherapy researcher’s perspective on therapist self-awareness and self-focused attention after a decade of research. Psychotherapy Research, 18(2), 139-146.

Just Who is this Guy (FlowChainSensei) Anyway? And Why is He Qualified to Comment on Agile Software Development?

Claude and I wrote me a new bio.

In the world of software development discourse, few voices are as provocative—or as polarising—as the one behind the handle FlowChainSensei. If you’ve spent any time in Agile circles online, you’ve likely encountered his scathing critiques of Agile software development practices. But who exactly is this mysterious figure who claims that ‘40 million brilliant minds‘ are now ‘spending their days in fruitless stand-ups and retrospectives’ and that ‘Agile has zero chance of delivering on its promises’?

Meet Bob Marshall: The Organisational AI TherapistFlowChainSensei is the online persona of Bob Marshall, who currently describes himself as an ‘Organisational AI therapist’. This isn’t just a catchy title—Bob brings serious credentials that explain why his voice carries weight in discussions about the future of both software development and organisational effectiveness.

BackgrounderBob’s career trajectory reveals the depth of his software development expertise. His first 20 years were spent in the trenches as a developer, analyst, designer, architect and code troubleshooter—roles that gave him intimate knowledge of how software actually gets built and where things go wrong. This hands-on experience was followed by some 15 years helping a multitude of clients improve their software development approaches, before evolving into his current therapeutic practice.

This progression from practitioner to consultant to therapist reflects an increasingly sophisticated understanding of where the real problems lie in software development—not in the technical details, but in the human and organisational systems that create the context for technical work.

Five Decades in the VanguardBob’s most compelling qualification is his longevity and verifiable involvement in the field. With 53 years in software development—including creating back in 1994 some practices that later became known as Agile—he has demonstrable evidence of being in the thick of it and the vanguard even before Agile happened.

During the period from 1994-2000, Bob was instrumental in creating what he calls ‘European Agile’ and created the Javelin software development method. This wasn’t someone learning about Agile from a certification course—Bob has documentation, project records, and verifiable traces of his involvement in developing the foundational practices years before the Agile Manifesto was even written.

From Agile Pioneer to Organisational PsychotherapistWhat sets Bob apart from other Agile worthies is his evolution beyond traditional consulting approaches. He spent fours years as founder and CEO of Familiar, the first 100% Agile software house in Europe, but that was decades ago. He hasn’t been a consultant for over 20 years.

Instead, Bob developed what he calls ‘Organisational Psychotherapy’—bringing psychotherapy techniques out of the therapy room and into the organisation as a whole. He’s documented this approach extensively in his book Hearts over Diamonds: Serving Business and Society through Organisational Psychotherapy (Marshall, 2019).

The Therapeutic Alliance: Why Relationships Trump SolutionsBob’s approach inverts everything most people expect from organisational change work. Where consultants diagnose problems and provide solutions, Bob creates space for organisations to surface their own unconscious assumptions. The key insight: it’s the therapeutic relationship itself that enables change, not any specific techniques or frameworks.

This relationship-centred approach explains why his work feels ‘alien’ to most business frameworks. People can’t categorise it as consulting, coaching, training, or change management because it operates from completely different assumptions about how transformation happens. As Bob notes in his therapeutic practice: voluntary participation is fundamental—nobody can be forced into genuine therapeutic engagement.

Organisational Cognitive Dissonance: The Hidden Driver of ReadinessOne of Bob’s notable contributions is his analysis of organisational cognitive dissonance—what happens when organisations simultaneously hold incompatible belief systems. In his seminal 2012 post on OrgCogDiss, he explains how this internal tension creates the conditions for genuine change.

Unlike external pressure, which organisations can often rationalise away, cognitive dissonance is internal and harder to dismiss. Bob observed that this dissonance typically resolves itself within a nine-month half-life—but often not in the direction change agents hope for. Organisations either fully adopt new approaches or revert to old patterns, but they can’t sustain internal contradictions indefinitely.

This insight explains why so many transformation efforts create enormous organisational pain but ultimately fail. The dissonance gets resolved through exits and resistance rather than genuine adoption, leaving organisations depleted but not actually transformed.

The Memeplex Problem: Why Piecemeal Change FailsBob’s work on ‘memeplexes’—interlocking systems of organisational beliefs—reveals why most change initiatives fail. You can’t swap out individual beliefs when they’re part of an interlocking system. Trying to introduce ‘self-organisation’ into a command-and-control organisation without addressing the entire supporting structure of beliefs about authority, expertise, and planning just creates internal contradictions.

He explores this concept further in his book Memeology: Surfacing and Reflecting on the Organisation’s Collective Assumptions and Beliefs (Marshall, 2021). Most failed transformations are attempts to graft elements from one memeplex onto another incompatible one, creating the very cognitive dissonance that eventually leads to rejection of the new elements.

Beyond Agile: The Quintessence AlternativeBob isn’t just a critic—he’s developed alternatives. His framework ‘Quintessence’, detailed in his book Quintessence: An Acme for Highly Effective Software Development Organisations (Marshall, 2021), represents what he calls ‘the radical departure from Agile norms, based as it is on people-oriented technologies such as sociology, group dynamics, psychiatry, psychology, psychotherapy, anthropology, cognitive science and modern neuroscience’.

But true to his therapeutic approach, Bob doesn’t push Quintessence as a solution to be implemented. Instead, he creates conditions where organisations might naturally evolve toward more effective ways of working based on their own insights and readiness.

The Evidence Question: Why Facts Don’t Change MindsBob makes a provocative observation about the role of evidence in organisational change: assertions often carry more weight than verifiable facts because ‘nobody’s opinion is swayed by evidence’. This isn’t cynicism—it’s recognition that evidence gets interpreted within existing paradigms until something else creates readiness for change.

Drawing on Thomas Kuhn’s work on paradigm shifts, Bob notes that evidence alone never creates fundamental change—it gets reinterpreted within existing frameworks until organisations become ready to see things differently. This readiness comes from organisational stress and cognitive dissonance, not from logical argument.

The Readiness Challenge: Why Most People Don’t EngageBob sees the general lack of engagement with his writing as corroboration for Gallup’s data on employee engagement—few are yet ready to own improvement efforts and their own motivation. Most people remain trapped in patterns where they expect solutions to be provided rather than taking responsibility for their own transformation.

This explains why his therapeutic approach focuses on creating conditions for readiness rather than trying to convince people with evidence or argument. Until someone genuinely wants to change, all the insights in the world won’t help them.

Why His Critique ResonatesBob’s perspective resonates with many practitioners experiencing Agile fatigue because he articulates what they feel but struggle to express. His recent post ‘How We Broke 40 Million Developers‘ struck a chord by describing how modern practices often feel performative rather than productive.

The Bottom Line: Qualified by Experience and UnderstandingIs Bob qualified to comment on Agile (and the alternatives)? Absolutely. His five+ decades in software development, his demonstrable involvement in creating pre-Agile practices, his experience sucessfully founding and running the first 100% Agile software house in Europe, and his deep work in organisational psychology and change give him a unique vantage point.

His perspective is clearly informed by his therapeutic practice and his promotion of alternative approaches. And his core challenge remains valid: after more than 20 years of Agile domination, are we better at attending to people’s needs? Are users getting products and services that genuinely serve them better?

The Therapeutic DifferenceWhat makes Bob’s voice distinctive isn’t just his comments on Agile—it’s his deep insights and understanding of how organisational change actually works. His therapeutic approach recognises that transformation happens through relationships and readiness, not through evidence and argument. Organisations change when they’re ready to see themselves differently, not when they’re presented with compelling data about their dysfunction.

This insight challenges the entire ‘evidence-based’ approach to organisational improvement. Bob suggests that meaningful change happens through shifts in readiness and perspective, with evidence becoming compelling only after those shifts occur, not before.

Whether you see Bob as a wise elder statesman or a contrarian voice, his decades of experience and unique therapeutic perspective offer valuable insights into why so many development efforts and ‘Agile transformation’ efforts fail—and what might work better.

Of course, you have to have the motivation to do better for any of Bob’s insights to be of any help to you.

Further ReadingBridges, W. (2004). Managing transitions: Making the most of change (2nd ed.). Da Capo Press.

Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. University of Chicago Press.

Marshall, R. W. (2019). Hearts over diamonds: Serving business and society through organisational psychotherapy. Leanpub.

Marshall, R. W. (2021a). Memeology: Surfacing and reflecting on the organisation’s collective assumptions and beliefs. Leanpub.

Marshall, R. W. (2021b). Quintessence: An acme for highly effective software development organisations. Leanpub.

Marshall, R. W. (2012, November 16). OrgCogDiss. Think Different. Retrieved from https://flowchainsensei.wordpress.com/2012/11/16/orgcogdiss/

Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications, and theory. Houghton Mifflin.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press.

Bob Marshall blogs at Think Different and his books on Organisational Psychotherapy, Memeology, and Quintessence are available through Leanpub.

September 16, 2025

The Agile Paradox: Why Developers Can’t Find a Way Out

How management mandates create the very problem they’re meant to solve

I’ve had the same conversation dozens of times over the past few years. A developer, usually over coffee or in the quiet corner of a conference, leans in and says something like: ‘I’m so tired of Agile. The ceremonies feel meaningless, the estimates are fiction, and we’re not actually being agile at all. Isn’t there something better?’

The frustration is real, and it’s widespread. But here’s the kicker: when I ask what alternative they’d prefer, the conversation usually stalls. Not because developers lack ideas—they have plenty—but because they’ve internalised a harsh truth. In most organisations, no alternative to Agile is ‘viable’ precisely because management has mandated Agile as the solution.

This creates a perfect catch-22 that keeps teams trapped in approaches that often aren’t working for them.

The Agile Promise vs RealityLet’s be clear: Agile methodologies weren’t born from management consultants or process enthusiasts. They emerged from developers who were frustrated with rigid, documentation-heavy approaches that seemed designed to prevent software from being built. The original Agile Manifesto was a rebellion against exactly the kind of top-down mandate we see today.

But somewhere along the way, Agile became the thing it was meant to replace. Instead of ‘individuals and interactions over processes and tools’, we got Scrum Masters obsessing over story point velocity. Instead of ‘responding to change over following a plan’, we got sprint commitments treated as unbreakable contracts.

The irony is thick.

The Viability TrapHere’s where the organisational dynamics get truly perverse. When management declares Agile as the standard approach, they’re not just choosing a process—they’re making it the only process that can succeed within the organisational context.

Consider what ‘viable’ means in a corporate environment:

Resource allocation: Only Agile-compatible roles get budget approvalTool selection: The company invests in Jira, Azure DevOps, or other Agile-focused platformsPerformance metrics: Success is measured in story points, sprint velocity, and burndown chartsCareer advancement: Understanding Agile ceremonies becomes a prerequisite for leadership rolesVendor relationships: Third-party teams and consultants are selected based on Agile experienceIn this ecosystem, suggesting an alternative approach isn’t just a process change—it’s asking the organisation to abandon significant investments and restructure fundamental management assumptions about how work gets measured and managed.

The Innovation Stifling EffectThe mandate creates a particularly insidious problem: it prevents the organic experimentation that led to Agile in the first place. The most effective development approaches often emerge from teams trying to solve specific problems in specific contexts. But when there’s only one ‘approved’ way to work, this natural evolution stops.

I’ve seen teams that would benefit enormously from approaches like:

Kanban-style continuous flow for maintenance-heavy projectsShape Up-style cycles for product development with unclear requirementsLean startup approaches for experimental featuresTraditional waterfall for compliance-heavy or well-understood domainsQuintessence for a total, yet incremental and self-paced overhaul of shared assumptions and beliefs about the very nature of workBut suggesting any of these becomes an uphill battle against established process, tooling, and metrics—not because they wouldn’t work better, but because the organisation has made them unviable by design (and mandate).

The Hidden CostsThis viability trap creates costs that rarely show up in sprint retrospectives:

Developer burnout increases when people feel trapped in ineffective processes they can’t change. The psychological impact of being forced to participate in ceremonies you believe are wasteful is significant.

Innovation slows when teams spend more energy navigating process requirements than solving actual problems. Every stand-up spent discussing why estimates were wrong is time not spent making the product better.

Talent retention suffers as experienced developers seek environments where they have more autonomy over how they work. The best developers often have options, and rigid process adherence isn’t typically what attracts them (understatement!).

Breaking the CycleSo how do we break out of this trap? Solution suggest we recognise that viability of alternatives is as much about the organisation as it is about development practices.

Start with principles, not processes. Instead of mandating specific ceremonies or frameworks, organisations might choose to focus on outcomes: shipped software, customer satisfaction, team health. Let teams experiment with how they achieve these goals.

Measure what matters. Story point velocity tells you very little about whether you’re building the right thing or building it well. Focus on metrics that actually correlate with business success and the needs of (all the) Folks That Matter .

.

Create safe spaces for experimentation. Allow teams to try different approaches for specific projects or timeframes. Make it clear that experiments are encouraged, and not career-limiting moves.

Invest in tooling flexibility. Choose platforms and tools that can support multiple approaches rather than locking into Agile-specific solutions (bin JIRA)

Most importantly, recognise that context matters. The approach that works for a startup building an MVP is different from what works for a team maintaining critical infrastructure. One size fits all is exactly the kind of thinking that led to Agile rebellion in the first place.

The Path ForwardThe developers crying out for alternatives aren’t anti-process or anti-collaboration. They’re pro-effectiveness. They want to build great software and have positive working relationships with their colleagues. They’re frustrated because they can see that the current approach isn’t achieving those goals, but they’re powerless to change it.

The path forward invites courage from both developers and management.

Until then, we’ll continue to have conversations in coffee shop corners about how things could be better, whilst the next sprint planning meeting looms on the calendar.

The real tragedy isn’t that Agile doesn’t work—it’s that we’ve created organisational structures that prevent us from discovering what would work better. And that’s the most un-agile thing of all.

What alternatives have you wanted to try but couldn’t? How has your organisation balanced consistency in the way the work works with team autonomy? The conversation continues in the comments and, hopefully, in conference room discussions everywhere.

Further ReadingAbrahamsson, P., Salo, O., Ronkainen, J., & Warsta, J. (2002). Agile software development methods: Review and analysis (Technical Report No. 478). VTT Publications.

Anderson, D. J. (2010). Kanban: Successful evolutionary change for your technology business. Blue Hole Press.

Boehm, B., & Turner, R. (2003). Balancing Agility and discipline: A guide for the perplexed. Addison-Wesley Professional.

British Computer Society. (2023, November 7). The uncomfortable truth about Agile. https://www.bcs.org/articles-opinion-and-research/the-uncomfortable-truth-about-agile/

Cockburn, A. (2006). Agile software development: The cooperative game (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley Professional.

Dalmijn, M. (2020, May 6). Basecamp’s Shape Up: How different is it really from Scrum? Serious Scrum. https://medium.com/serious-scrum/basecamps-shape-up-how-different-is-it-really-from-scrum-c0298f124333

DeMarco, T., & Lister, T. (2013). Peopleware: Productive projects and teams (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley Professional.

Hunt, A. (2015, December 20). The failure of Agile. Atlantic Monthly. https://blog.toolshed.com/2015/05/the-failure-of-agile.html

Noble, J., & Biddle, R. (2018). Back to the future: Origins and directions of the “Agile Manifesto”—views of the originators. Journal of Software Engineering Research and Development, 6(1), Article 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40411-018-0059-z

Poppendieck, M., & Poppendieck, T. (2003). Lean software development: An Agile toolkit. Addison-Wesley Professional.

Serrador, P., & Pinto, J. K. (2015). Does Agile work? A quantitative analysis of Agile project success. International Journal of Project Management, 33(5), 1040-1051.

Singer, R. (2019). Shape Up: Stop running in circles and ship work that matters. Basecamp. https://basecamp.com/shapeup

Thomas, D. (2019). Agile is dead (long live Agility). In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGPLAN Symposium on Scala (pp. 1-1).

September 15, 2025

The Agile Manifesto: Rearranging Deck Chairs While Five Dragons Burn Everything Down

The Agile Manifesto isn’t wrong, per se—it’s addressing the wrong problems entirely. And that makes it tragically inadequate.

For over two decades, ‘progressive’ software teams have been meticulously implementing sprints, standups, and retrospectives whilst the real dragons have been systematically destroying their organisations from within. The manifesto’s principles aren’t incorrect; they’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic whilst it sinks around them.

The four values and twelve principles address surface symptoms of dysfunction whilst completely ignoring the deep systemic diseases that kill software projects. It’s treating a patient’s cough whilst missing the lung cancer—technically sound advice that’s spectacularly missing the point.

The Real Dragons: What Actually Destroys Software TeamsWhilst we’ve been optimising sprint ceremonies and customer feedback loops, five ancient dragons have been spectacularly burning down software development and tech business effectiveness:

Dragon #1: Human Motivation Death Spiral

Dragon #2: Dysfunctional Relationships That Poison Everything

Dragon #3: Shared Delusions and Toxic Assumptions

Dragon #4: The Management Conundrum—Questioning the Entire Edifice

Dragon #5: Opinioneering—The Ethics of Belief Violated

These aren’t process problems or communication hiccups. They’re existential threats that turn the most well-intentioned agile practices into elaborate theatre whilst real work grinds to a halt. And the manifesto? It tiptoes around these dragons like they don’t exist.

Dragon #1: The Motivation Apocalypse‘Individuals and interactions over processes and tools’ sounds inspiring until you realise that your individuals are fundamentally unmotivated to do good work. The manifesto assumes that people care—but what happens when they don’t?

The real productivity killer isn’t bad processes; it’s developers who have mentally checked out because:

They’re working on problems they find meaninglessTheir contributions are invisible or undervaluedThey have no autonomy over how they solve problemsThe work provides no sense of mastery or purposeThey’re trapped in roles that don’t match their strengthsYou can have the most collaborative, customer-focused, change-responsive team in the world, but if your developers are quietly doing the minimum to avoid getting fired, your velocity will crater regardless of your methodology.

The manifesto talks about valuing individuals but offers zero framework for understanding what actually motivates people to do their best work. It’s having a sports philosophy that emphasises teamwork whilst ignoring whether the players actually want to win the game. How do you optimise ‘individuals and interactions’ when your people have checked out?

Dragon #2: Relationship Toxicity That Spreads Like Cancer‘Customer collaboration over contract negotiation’ assumes that collaboration is even possible—but what happens when your team relationships are fundamentally dysfunctional?

The real collaboration killers that the manifesto ignores entirely:

Trust deficits: When team members assume bad faith in every interactionEgo warfare: When technical discussions become personal attacks on competencePassive aggression: When surface civility masks deep resentment and sabotageFear: When people are afraid to admit mistakes or ask questionsStatus games: When helping others succeed feels like personal failureYou hold all the retrospectives you want, but if your team dynamics are toxic, every agile practice becomes a new battlefield. Sprint planning turns into blame assignment. Code reviews become character assassination. Customer feedback becomes ammunition for internal warfare.

The manifesto’s collaboration principles are useless when the fundamental relationships are broken. It’s having marriage counselling techniques for couples who actively hate each other—technically correct advice that misses the deeper poison. How do you collaborate when trust has been destroyed? What good are retrospectives when people are actively sabotaging each other?

Dragon #3: Shared Delusions That Doom Everything‘Working software over comprehensive documentation’ sounds pragmatic until you realise your team is operating under completely different assumptions about what ‘working’ means, what the software does, and how success is measured. But what happens when your team shares fundamental delusions about reality?

The productivity apocalypse happens when teams share fundamental delusions:

Reality distortion: Believing their product is simpler/better/faster than it actually isCapability myths: Assuming they can deliver impossible timelines with current resourcesQuality blindness: Thinking ‘works on my machine’ equals production-readyUser fiction: Building for imaginary users with imaginary needsTechnical debt denial: Pretending that cutting corners won’t compound into disasterThese aren’t communication problems that better customer collaboration can solve—they’re shared cognitive failures that make all collaboration worse. When your entire team believes something that’s factually wrong, more interaction just spreads the delusion faster.

The manifesto assumes that teams accurately assess their situation and respond appropriately. But when their shared mental models are fundamentally broken? All the adaptive planning in the world won’t help if you’re adapting based on fiction.

Dragon #4: The Management Conundrum—Why the Entire Edifice Is Suspect‘Responding to change over following a plan’ sounds flexible, but let’s ask the deeper question: Why do we have management at all?

The manifesto takes management as a given and tries to optimise around it. But what if the entire concept of management—people whose job is to direct other people’s work without doing the work themselves—is a fundamental problem?

Consider what management actually does in most software organisations:

Creates artificial hierarchies that slow down decision-makingAdds communication layers that distort information as it flows up and downOptimises for command and control rather than effectivenessMakes decisions based on PowerPoint and opinion rather than evidenceTreats humans like interchangeable resources to be allocated and reallocatedThe devastating realisation is that management in software development is pure overhead that actively impedes the work. Managers who:

Haven’t written code in years (or ever) making technical decisionsSet timelines based on business commitments rather than realityReorganise teams mid-project because a consultant recommended ‘matrix management’ or some suchMeasure productivity by story points rather than needs attended to (or met)Translate clear customer needs into incomprehensible requirements documentsWhat value does this actually add? Why do we have people who don’t understand the work making decisions about the work? What if every management layer is just expensive interference?

The right number of managers for software teams is zero. The entire edifice of management—the org charts, the performance reviews, the resource allocation meetings—is elaborate theatre that gets in the way of people solving problems.

Productive software teams operate more like research labs or craftsman guilds: self-organising groups of experts who coordinate directly with each other and with the people who use their work. No sprint masters, no product owners, no engineering managers—just competent people working together to solve problems.

The manifesto’s principles assume management exists and try to make it less harmful. But they never question whether it has any value at all.

Dragon #5: Opinioneering—The Ethics of Belief ViolatedHere’s the dragon that the manifesto not only ignores but actually enables: the epidemic of strong opinions held without sufficient evidence.

William Kingdon Clifford wrote in 1877 that

‘it is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence’

(Clifford, 1877).

In software development, we’ve created an entire culture that violates this ethical principle daily through systematic opinioneering:

Technical Opinioneering: Teams adopting microservices because they’re trendy, not because they solve actual problems. Choosing React over Vue because it ‘feels’ better. Implementing event sourcing because it sounds sophisticated. Strong architectural opinions based on blog posts rather than deep experience with the trade-offs.

Process Opinioneering: Cargo cult agile practices copied from other companies without understanding why they worked there. Daily standups that serve no purpose except ‘that’s what agile teams do.’ Retrospectives that generate the same insights every sprint because the team has strong opinions about process improvement but no evidence about what actually works.

Business Opinioneering: Product decisions based on what the CEO likes rather than what users require. Feature priorities set by whoever argues most passionately rather than data about user behaviour. Strategic technology choices based on industry buzz rather than careful analysis of alternatives.

Cultural Opinioneering: Beliefs about remote work, hiring practices, team structure, and development methodologies based on what sounds right rather than careful observation of results.

The manifesto makes this worse by promoting ‘individuals and interactions over processes and tools’ without any framework for distinguishing between evidence-based insights and opinion-based groupthink. It encourages teams to trust their collective judgement without asking whether that judgement is grounded in sufficient evidence. But what happens when the collective judgement is confidently wrong? How do you distinguish expertise from persuasive ignorance?

When opinioneering dominates, you get teams that are very confident about practices that don’t work, technologies that aren’t suitable, and processes that waste enormous amounts of time. Everyone feels like they’re making thoughtful decisions, but they’re sharing unfounded beliefs dressed up as expertise.

The Deeper Problem: Dysfunctional Shared Assumptions and BeliefsThe five dragons aren’t just symptoms—they’re manifestations of something deeper. Software development organisations operate under shared assumptions and beliefs that make effectiveness impossible, and the Agile Manifesto doesn’t even acknowledge this fundamental layer exists.

My work in Quintessence provides the missing framework for understanding why agile practices fail so consistently. The core insight is that organisational effectiveness is fundamentally a function of collective mindset:

Organisational effectiveness = f(collective mindset)

I demonstrate that every organisation operates within a “memeplex“—a set of interlocking assumptions and beliefs about work, people, and how organisations function. These beliefs reinforce each other so strongly that changing one belief causes the others to tighten their grip to preserve the whole memeplex.

This explains why agile transformations consistently fail. Teams implement new ceremonies whilst maintaining the underlying assumptions that created their problems in the first place. They adopt standups and retrospectives whilst still believing people are motivated, relationships are authentic, management adds value, and software is always the solution.

Consider the dysfunctional assumptions that pervade conventional software development:

About People: Most organisations and their management operate under “Theory X” assumptions—people are naturally lazy, require external motivation, need oversight to be productive, and will shirk responsibility without means to enforce accountability. These beliefs create the very motivation problems they claim to address.

About Relationships: Conventional thinking treats relationships as transactional. Competition drives performance. Hierarchy creates order. Control prevents chaos. Personal connections are “unprofessional.” These assumptions poison the collaboration that agile practices supposedly enable.

About Work: Software is the solution to every problem. Activity indicates value. Utilisation (of eg workers) drives productivity. Efficiency trumps effectiveness. Busyness proves contribution. These beliefs create the delusions that make teams confidently ineffective.

About Management: Complex work requires coordination. Coordination requires hierarchy. Hierarchy requires managers. Managers add value through oversight and direction. These assumptions create the parasitic layers that impede the very work they claim to optimise.

About Knowledge: Strong opinions indicate expertise. Confidence signals competence. Popular practices are best practices. Best practices are desirable. Industry trends predict future success. These beliefs create the opinioneering that replaces evidence with folklore.

Quintessence (Marshall, 2021) shows how “quintessential organisations” operate under completely different assumptions:

People find joy in meaningful work and naturally collaborate when conditions support itRelationships based on mutual care and shared purpose are the foundation of effectivenessWork is play when aligned with purpose and human flourishingManagement is unnecessary parasitism—people doing the work make the decisions about the workBeliefs must be proportioned to evidence and grounded in serving real human needsThe Agile Manifesto can’t solve problems created by fundamental belief systems because it doesn’t even acknowledge these belief systems exist. It treats symptoms whilst leaving the disease untouched. Teams optimise ceremonies whilst operating under assumptions that guarantee continued dysfunction.

This is why the Qunitessence approach differs so radically from ‘Agile’ approaches. Instead of implementing new practices, quintessential organisations examine their collective assumptions and beliefs. Instead of optimising processes, they transform their collective mindset. Instead of rearranging deck chairs, they address the fundamental reasons the ship is sinking.

The Manifesto’s Tragic BlindnessHere’s what makes the Agile Manifesto so inadequate: it assumes the Five Dragons don’t exist. It offers principles for teams that are motivated, functional, reality-based, self-managing, and evidence-driven—but most software teams are none of these things.

The manifesto treats symptoms whilst ignoring diseases:

It optimises collaboration without addressing what makes collaboration impossibleIt values individuals without confronting what demotivates themIt promotes adaptation without recognising what prevents teams from seeing their shared assumptions and beliefs clearlyIt assumes management adds value rather than questioning whether management has any value at allIt encourages collective decision-making without any framework for leveraging evidence-based beliefsThis isn’t a failure of execution—it’s a failure of diagnosis. The manifesto identified the wrong problems and thus prescribed the wrong solutions.

Tom Gilb’s Devastating Assessment: The Manifesto Is Fundamentally FuzzySoftware engineering pioneer Tom Gilb delivers the most damning critique of the Agile Manifesto: its principles are

‘so fuzzy that I am sure no two people, and no two manifesto signers, understand any one of them identically’

(Gilb, 2005).

This fuzziness isn’t accidental—it’s structural. The manifesto was created by ‘far too many “coders at heart” who negotiated the Manifesto’ without

‘understanding of the notion of delivering measurable and useful stakeholder value’

(Gilb, 2005).

The result is a manifesto that sounds profound but provides no actionable guidance for success in product development.

Gilb’s critique exposes the manifesto’s fundamental flaw: it optimises for developer comfort rather than stakeholder value. The principles read like a programmer’s wish list—less documentation, more flexibility, fewer constraints—rather than a framework for delivering measurable results to people who actually need the software.

This explains why teams can religiously follow agile practices whilst consistently failing to deliver against folks’ needs. The manifesto’s principles are so vague that any team can claim to be following them whilst doing whatever they want. ‘Working software over comprehensive documentation’ means anything you want it to mean. ‘Responding to change over following a plan’ provides zero guidance on how to respond or what changes matter. (Cf. Quantification)

How do you measure success when the principles themselves are unmeasurable? What happens when everyone can be ‘agile’ whilst accomplishing nothing? How do you argue against a methodology that can’t be proven wrong?

The manifesto’s fuzziness enables the very dragons it claims to solve. Opinioneering thrives when principles are too vague to be proven wrong. Management parasitism flourishes when success metrics are unquantified Shared delusions multiply when ‘working software’ has no operational definition.

Gilb’s assessment reveals why the manifesto has persisted despite its irrelevance: it’s comfortable nonsense that threatens no one and demands nothing specific. Teams can feel enlightened whilst accomplishing nothing meaningful for stakeholders.

Stakeholder Value vs. All the Needs of All the Folks That Matter

Gilb’s critique centres on ‘delivering measurable and useful stakeholder value’—but this phrase itself illuminates a deeper problem with how we think about software development success. ‘Stakeholder value’ sounds corporate and abstract, like something you’d find in a business school textbook or an MBA course (MBA – maybe best avoided – Mintzberg)

What we’re really talking about is simpler, less corporate and more human: serving all the needs of all the Folks That Matter .

.

The Folks That Matter aren’t abstract ‘stakeholders’—they’re real people trying to get real things done:

The nurse trying to access patient records during a medical emergencyThe small business owner trying to process payroll before FridayThe student trying to submit an assignment before the deadlineThe elderly person trying to video call their grandchildrenThe developer trying to understand why the build is broken againWhen software fails these people, it doesn’t matter how perfectly agile your process was. When the nurse can’t access records, your retrospectives are irrelevant. When the payroll system crashes, your customer collaboration techniques are meaningless. When the build and smoke takes 30+ minutes, your adaptive planning is useless.

The Agile Manifesto’s developer-centric worldview treats these people as distant abstractions—’users’ and ‘customers’ and ‘stakeholders.’ But they’re not abstractions. They’re the Folks That Matter , and their needs are the only reason software development exists.

, and their needs are the only reason software development exists.

The manifesto’s principles consistently prioritise developer preferences over the requirements of the Folks That Matter . ‘Working software over comprehensive documentation’ sounds reasonable until the Folks That Matter

. ‘Working software over comprehensive documentation’ sounds reasonable until the Folks That Matter require understanding of how to use the software. ‘Individuals and interactions over processes and tools’ sounds collaborative until the Folks That Matter

require understanding of how to use the software. ‘Individuals and interactions over processes and tools’ sounds collaborative until the Folks That Matter require consistent, reliable results from those interactions.

require consistent, reliable results from those interactions.

This isn’t about being anti-developer—it’s about recognising that serving the Folks That Matter is the entire point. The manifesto has it backwards: instead of asking ‘How do we make development more comfortable for developers?’ we might ask ‘How do we reliably serve all the requirements of all the Folks That Matter

is the entire point. The manifesto has it backwards: instead of asking ‘How do we make development more comfortable for developers?’ we might ask ‘How do we reliably serve all the requirements of all the Folks That Matter ?’ That question changes everything. It makes motivation obvious—you’re solving real problems for real people. It makes relationship health essential—toxic teams can’t serve others effectively. It makes reality contact mandatory—delusions about quality hurt real people. It makes evidence-based decisions critical—opinions don’t serve the Folks That Matter

?’ That question changes everything. It makes motivation obvious—you’re solving real problems for real people. It makes relationship health essential—toxic teams can’t serve others effectively. It makes reality contact mandatory—delusions about quality hurt real people. It makes evidence-based decisions critical—opinions don’t serve the Folks That Matter ; results do.

; results do.

Most importantly, it makes management’s value proposition clear: Do you help us serve the Folks That Matter better, or do you get in the way? If the answer is ‘get in the way,’ then management becomes obviously a dysfunction.

better, or do you get in the way? If the answer is ‘get in the way,’ then management becomes obviously a dysfunction.

If we want to improve software development effectiveness, we address the real dragons:

Address Motivation: Create work that people actually care about. Give developers autonomy, mastery, and purpose. Match people to problems they find meaningful. Make contributions visible and valued.

Heal Toxic Relationships: Build psychological safety where people can be vulnerable about mistakes. Address ego and status games directly. Create systems where helping others succeed feels like personal victory.

Resolve Shared Delusions: Implement feedback loops that invite contact with reality. Measure what actually matters. Create cultures where surfacing uncomfortable truths is rewarded rather than punished.

Transform Management Entirely: Experiment with self-organising teams. Distribute decision-making authority to where expertise actually lives. Eliminate layers between problems and problem-solvers. Measure needs met, not management theatre.

Counter Evidence-Free Beliefs: Institute a culture where strong opinions require strong evidence. Enable and encourage teams to articulate the assumptions behind their practices. Reward changing your mind based on new data. Excise confident ignorance.

These aren’t process improvements or methodology tweaks—they’re organisational transformation efforts that require fundamentally different approaches than the manifesto suggests.

Beyond Agile: Addressing the Real ProblemsThe future of software development effectiveness isn’t in better sprint planning or more customer feedback. It’s in organisational structures that:

Align individual motivation with real needsCreate relationships based on trustEnable contact with reality at every levelEliminate management as dysfunctionalGround all beliefs in sufficient evidenceThese are the 10x improvements hiding in plain sight—not in our next retrospective, but in our next conversation about why people don’t care about their work. Not in our customer collaboration techniques, but in questioning whether we have managers at all. Not in our planning processes, but in demanding evidence for every strong opinion.

Conclusion: The Problems We Were Addressing All AlongThe Agile Manifesto succeeded in solving the surface developer bugbears of 2001: heavyweight processes and excessive documentation. But it completely missed the deeper organisational and human issues that determine whether software development succeeds or fails.

The manifesto’s principles aren’t wrong—they’re just irrelevant to the real challenges. Whilst we’ve been perfecting our agile practices, the dragons of motivation, relationships, shared delusions, management being dysfunctional, and opinioneering have been systematically destroying software development from within.

Is it time to stop optimising team ceremonies and start addressing the real problems? Creating organisations where people are motivated to do great work, relationships enable rather than sabotage collaboration, shared assumptions are grounded in reality, traditional management no longer exists, and beliefs are proportioned to evidence.

But ask yourself: Does your organisation address any of these fundamental issues? Are you optimising ceremonies whilst your dragons run wild? What would happen if you stopped rearranging deck chairs and started questioning why people don’t care about their work?

Because no amount of process optimisation will save a team where people don’t care, can’t trust each other, believe comfortable lies, are managed by people who add negative value, and make decisions based on opinions rather than evidence.

The dragons are real, and they’re winning. Are we finally ready to address them?

Further ReadingBeck, K., Beedle, M., van Bennekum, A., Cockburn, A., Cunningham, W., Fowler, M., … & Thomas, D. (2001). Manifesto for Agile Software Development. Retrieved from https://agilemanifesto.org/

Clifford, W. K. (1877). The ethics of belief. Contemporary Review, 29, 289-309.

Gilb, T. (2005). Competitive Engineering: A Handbook for Systems Engineering, Requirements Engineering, and Software Engineering Using Planguage. Butterworth-Heinemann.

Gilb, T. (2017). How well does the Agile Manifesto align with principles that lead to success in product development? Retrieved from https://www.gilb.com/blog/how-well-does-the-agile-manifesto-align-with-principles-that-lead-to-success-in-product-development

Marshall, R.W. (2021). *Quintessence: An Acme for Software Development Organisations. *[online] leanpub.com. Falling Blossoms (LeanPub). Available at: https://leanpub.com/quintessence/ [Accessed 15 Jun 2022].

September 13, 2025

Praising the CRC Card

For the developers who never got to hold one

If you started your career after 2010, you probably never encountered a CRC card. If you’re a seasoned developer who came up through Rails tutorials, React bootcamps, or cloud-native microservices, you likely went straight from user stories to code without stopping at index cards. This isn’t your fault. By the time you arrived, the industry had already moved on.

But something was lost in that transition, and it might be valuable for you to experience it.

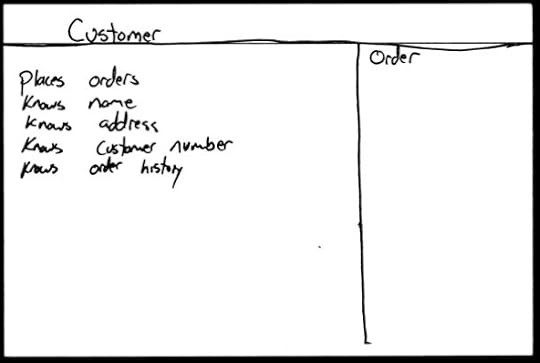

What You MissedA CRC card is exactly what it sounds like: a Class-Responsibility-Collaborator design written on a physical index card. One class per card. The class name at the top, its responsibilities listed on the left, and the other classes it works with noted on the right. Simple. Physical. Throwaway.

The technique was developed by Ward Cunningham and Kent Beck in the late 1980s, originally emerging from Cunningham’s work with HyperCard documentation systems. They introduced CRC cards as a teaching tool, but the approach was embraced by practitioners following ideas like Peter Coad’s object-oriented analysis, design, and programming (OOA/D/P) framework. Peter Coad (with Ed Yourdon) wrote about a unified approach to building software that matched how humans naturally think about problems. CRC cards are a tool for translating business domain concepts directly into software design, without getting lost in technical abstractions.

The magic wasn’t in the format—it was in what the format forced you to do.

The ExperiencePicture this: You and your teammates sitting around a conference table covered in index cards. Someone suggests a new class. They grab a blank card and write ‘ShoppingCart’ at the top. ‘What should it do?’ someone asks. ‘Add items, remove items, calculate totals, apply promotions,’ comes the reply. Those go in the responsibilities column. ‘What does it need to work with?’ Another pause. ‘It needs Product objects to know what’s being added, a Customer for personalised pricing, maybe a Promotion when discounts apply.’ Those become collaborators.

But here’s where it gets interesting. The card is small. Really small. If you’re writing tiny text to fit more responsibilities, someone notices. If you have fifteen collaborators, the card looks messy. The physical constraint was a design constraint. It whispered: ‘Keep it simple.’

Aside: In Javelin, we also advise keeping all methods to no more than “Five Lines of Code”. And Statements of Purpose to 25 words or less.

The SeductionSomewhere in the 2000s, we got seduced. UML tools (yak) promised prettier diagrams. Digital whiteboards now offer infinite canvas space. Collaborative software lets us design asynchronously across time zones. We can version control our designs! Track changes! Generate code from diagrams!

We told ourselves this was progress. We retrofitted justifications: ‘Modern systems are too complex for index cards.’ ‘Remote teams need digital tools.’ ‘Physical methods don’t scale.’

But these were lame excuses, not good reasons.

The truth is simpler and more embarrassing: we abandoned CRC cards because they felt primitive. Index cards seemed amateur next to sophisticated UML tools and enterprise architecture platforms. We confused the sophistication of our tools with the sophistication of our thinking.

What We Actually LostThe constraint was the feature. An index card can’t hold a God class. It can’t accommodate a class with dozens of responsibilities or collaborators. But more importantly, it forced you to think in domain terms, not implementation terms. When you’re limited to an index card, you can’t hide behind technical abstractions like ‘DataProcessor’ or ‘ValidationManager.’ You have to name things that represent actual concepts in the problem domain – things a business person would recognise. The physical limitation forced good design decisions and domain-focused thinking before you had time to rationalise technical complexity.

Throwaway thinking was powerful. When your design lived on index cards, you could literally throw it away and start over. No one was attached to the beautiful diagram they’d spent hours or days perfecting. The design was disposable, which made experimentation safe.

Tactile collaboration was different. There’s something unique about physically moving cards around a table, stacking them, pointing at them, sliding one toward a teammate. Digital tools simulate this poorly. Clicking and dragging isn’t the same as picking up a card and handing it to someone.

Forced focus was valuable. You couldn’t switch to Slack during a CRC card session. You couldn’t zoom in on implementation details. The cards kept you at the right level of abstraction—not so high that you were hand-waving, not so low that you were bikeshedding variable names.

The Ratchet EffectHere’s what makes this particularly tragic: once the industry moved to digital tools, it became genuinely harder to go back. Try suggesting index cards in a design meeting today. You’ll get polite smiles and concerned looks. Not because the method doesn’t work, but because the ecosystem has moved backwards. The new developers have never seen it done. The tooling assumes digital. The ‘best practices’ articles all recommend software solutions.

We created a ratchet effect where good practices became impossible to maintain not because they were inadequate, but because they felt outdated.