Praising the CRC Card

For the developers who never got to hold one

If you started your career after 2010, you probably never encountered a CRC card. If you’re a seasoned developer who came up through Rails tutorials, React bootcamps, or cloud-native microservices, you likely went straight from user stories to code without stopping at index cards. This isn’t your fault. By the time you arrived, the industry had already moved on.

But something was lost in that transition, and it might be valuable for you to experience it.

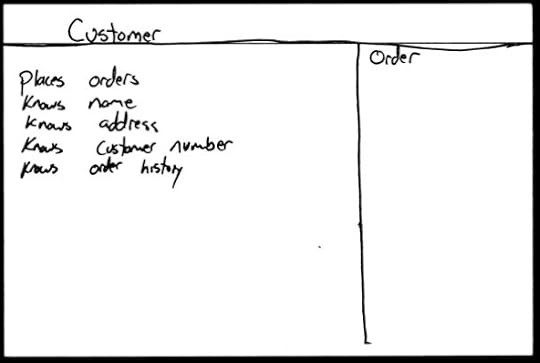

What You MissedA CRC card is exactly what it sounds like: a Class-Responsibility-Collaborator design written on a physical index card. One class per card. The class name at the top, its responsibilities listed on the left, and the other classes it works with noted on the right. Simple. Physical. Throwaway.

The technique was developed by Ward Cunningham and Kent Beck in the late 1980s, originally emerging from Cunningham’s work with HyperCard documentation systems. They introduced CRC cards as a teaching tool, but the approach was embraced by practitioners following ideas like Peter Coad’s object-oriented analysis, design, and programming (OOA/D/P) framework. Peter Coad (with Ed Yourdon) wrote about a unified approach to building software that matched how humans naturally think about problems. CRC cards are a tool for translating business domain concepts directly into software design, without getting lost in technical abstractions.

The magic wasn’t in the format—it was in what the format forced you to do.

The ExperiencePicture this: You and your teammates sitting around a conference table covered in index cards. Someone suggests a new class. They grab a blank card and write ‘ShoppingCart’ at the top. ‘What should it do?’ someone asks. ‘Add items, remove items, calculate totals, apply promotions,’ comes the reply. Those go in the responsibilities column. ‘What does it need to work with?’ Another pause. ‘It needs Product objects to know what’s being added, a Customer for personalised pricing, maybe a Promotion when discounts apply.’ Those become collaborators.

But here’s where it gets interesting. The card is small. Really small. If you’re writing tiny text to fit more responsibilities, someone notices. If you have fifteen collaborators, the card looks messy. The physical constraint was a design constraint. It whispered: ‘Keep it simple.’

Aside: In Javelin, we also advise keeping all methods to no more than “Five Lines of Code”. And Statements of Purpose to 25 words or less.

The SeductionSomewhere in the 2000s, we got seduced. UML tools (yak) promised prettier diagrams. Digital whiteboards now offer infinite canvas space. Collaborative software lets us design asynchronously across time zones. We can version control our designs! Track changes! Generate code from diagrams!

We told ourselves this was progress. We retrofitted justifications: ‘Modern systems are too complex for index cards.’ ‘Remote teams need digital tools.’ ‘Physical methods don’t scale.’

But these were lame excuses, not good reasons.

The truth is simpler and more embarrassing: we abandoned CRC cards because they felt primitive. Index cards seemed amateur next to sophisticated UML tools and enterprise architecture platforms. We confused the sophistication of our tools with the sophistication of our thinking.

What We Actually LostThe constraint was the feature. An index card can’t hold a God class. It can’t accommodate a class with dozens of responsibilities or collaborators. But more importantly, it forced you to think in domain terms, not implementation terms. When you’re limited to an index card, you can’t hide behind technical abstractions like ‘DataProcessor’ or ‘ValidationManager.’ You have to name things that represent actual concepts in the problem domain – things a business person would recognise. The physical limitation forced good design decisions and domain-focused thinking before you had time to rationalise technical complexity.

Throwaway thinking was powerful. When your design lived on index cards, you could literally throw it away and start over. No one was attached to the beautiful diagram they’d spent hours or days perfecting. The design was disposable, which made experimentation safe.

Tactile collaboration was different. There’s something unique about physically moving cards around a table, stacking them, pointing at them, sliding one toward a teammate. Digital tools simulate this poorly. Clicking and dragging isn’t the same as picking up a card and handing it to someone.

Forced focus was valuable. You couldn’t switch to Slack during a CRC card session. You couldn’t zoom in on implementation details. The cards kept you at the right level of abstraction—not so high that you were hand-waving, not so low that you were bikeshedding variable names.

The Ratchet EffectHere’s what makes this particularly tragic: once the industry moved to digital tools, it became genuinely harder to go back. Try suggesting index cards in a design meeting today. You’ll get polite smiles and concerned looks. Not because the method doesn’t work, but because the ecosystem has moved backwards. The new developers have never seen it done. The tooling assumes digital. The ‘best practices’ articles all recommend software solutions.

We created a ratchet effect where good practices became impossible to maintain not because they were inadequate, but because they felt outdated.

For Those Who Never Got the ChanceIf you’re reading this as a developer who never used CRC cards, I want you to know: you were cheated, but not by your own choices. You came into an industry that had already forgotten one of its own most useful practices. You learned the tools that were available when you arrived.

But you also inherited the complexity that came from abandoning constraints. You’ve probably spent hours in architecture meetings where the design sprawled across infinite digital canvases, where classes accumulated responsibilities because the tools could accommodate any amount of complexity, where the ease of adding ‘just one more connection’ led to systems that no one fully understood.

You’ve felt the pain of what we lost when we abandoned the constraint.

A Small ExperimentNext time you’re designing something new, try this: grab some actual index cards. Write one class per card. See how it feels when the physical constraint pushes back against your design. Notice what happens when throwing away a card costs nothing but keeping a complex design visible costs table space.

You might discover something we lost when we got sophisticated.

Do it because CRC cards were actually superior to modern digital tools for early design thinking. We didn’t outgrow them – we abandoned something better for something shinier.

Sometimes the simpler tool was better precisely because it was simpler.

The industry moves fast, and not everything we leave behind should have been abandoned. Some tools die not because they’re inadequate, but because they’re unfashionable. The CRC card was a casualty of progress that wasn’t progressive.

Further ReadingBeck, K., & Cunningham, W. (1989). A laboratory for teaching object-oriented thinking. SIGPLAN Notices, 24(10), 1-6.

Coad, P., & Yourdon, E. (1990). Object-oriented analysis. Yourdon Press.

Coad, P., & Yourdon, E. (1991). Object-oriented design. Yourdon Press.

Coad, P., North, D., & Mayfield, M. (1995). Object-oriented programming. Prentice Hall.

Coad, P., North, D., & Mayfield, M. (1996). Object models: Strategies, patterns, and applications (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall.

Wirfs-Brock, R., & McKean, A. (2003). Object design: Roles, responsibilities, and collaborations. Addison-Wesley.