Cynthia Dewi Oka's Blog

November 13, 2016

Post-Election Song of Myself

Time walked across the street called midnight.

It left us standing in a forest of pundits and their fluorescent fruit.

Still, it was dim. As water in the bowels of the city, as the impression that I had been here before, looking over this fear in the shape of a red pudding, trembling at the fork’s slightest gesture.

What good is the fork when hunger is gone?

There is no secret to resurrection buried under the wood. I know I am forcing the opposite of song to sing.

Does it ever miss us – time, I mean? As it strides into the fire-worked night, the crowds pale with clenching their fists.

A predator has been elected president.

Strangely, his orange-ness reminds me of hope. In the sense that as a child I used to swallow orange seeds to transform my body into a tree.

Because in place of roots, a displaced people have nerves sparkling with rings far too small for our fingers.

Binders of laminated identity, and mothballs to seduce time into staying a little while longer.

Does it ever miss us – hung here like lanterns over the monstrous body of love?

I was seven when I tried to pee standing up without a penis. The piss ran hot down my legs, and I knew I had failed.

The latch was rusted shut. In the ditch under the toilet seat, mosquitos bred their empire.

I banged on the door, screaming, “Papa! Papa!” though I knew he would beat me afterward for trying to escape my body.

This is how I think about race in America. That banging,

because we do not want to die.

A white supremacist has been elected president, and I keep

thinking about the bullets hugged by my friends’ brains, and my father, skin smooth as teeth, under a thin hospital blanket.

How he drew that last breath and everything behind it:

the buses stained with chicken shit, the ghosts in the rafters who stole his hair

and the combs for his remaining hair,

my mother’s feet black with dried blood,

and everything he was willing to kill in himself

to be here, and hated

in a new way. How that breath raged

inside him, and how I stood at the closed door of his life, with no hammer, no key.

I never did grow leaves, and roots to me sound like Questlove saying, “Time will tell…Time never stops telling,” which is another way of saying time will not come back to save us,

the body is not a thing to escape.

Here is mine. It is soft and hard at once. It pees sitting down. Sometimes it can exhale a poem out of the most poisoned air.

It would eat the rusted latch before it gives in.

April 30, 2016

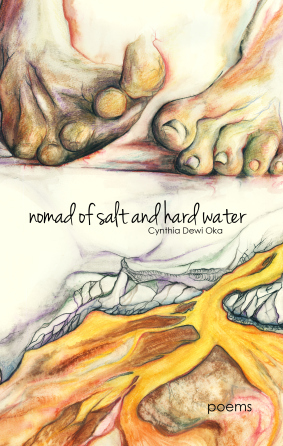

Nomad of Salt and Hard Water

It wasn’t me you saw

among the pale shipwrecked vowels.

I have never breathed that sunset,

I have never been found.

Excerpt from the Preface:

After the first print run of Nomad sold out, I was offered the opportunity to do a second printing with Thread Makes Blanket press. Inspired by Audre Lorde, who revised her poems until the end of her life, I wanted to see what would happen if I re-approached the poems in Nomad. I had just finished writing my second collection and my personal life was beginning to settle after a few years of major transitions. Revisiting Nomad was an opportunity to reflect on my vision and poetics at a time when my understanding of what it meant to be a woman of color, a migrant, a survivor, a mother, a laborer, a witness – and other identities that I relied on to inhabit the world – had been deeply shaken.

And lest there be any suggestion that such a challenge was presented by a “post-racial” society or any other analogous “improvement” in our state of affairs, let me clarify that exactly the opposite happened. It was, in fact, confronting the powerlessness of these identities in the face of relentless state, corporate, white and male brutality that made me realize how insufficient they were as incubators of freedom, no matter how solid or how much of my hope for communion depended on their existence within the soul-starving landscape of neoliberalism. As James Baldwin so aptly wrote, “People are trapped in history, and history is trapped in them.”

Examining the foundational moments that motivated the writing of Nomad became a radical search for cracks in the walls. And if I was once tempted to beautify them, I have, through this project, tried to understand how the poems themselves could become acts of slipping through.

…By extension, I hope this experiment might help readers question the idea of fixed points in poetry, that is, the “canon,” through which the West manifests its paradigm of civilization as a linear, cumulative archive of self-enclosed categories. Coming from a line of displaced people, people who have not been wanted by their home- or host lands, who are constantly erasing and reinventing past lives, I feel particularly conscious of being made up of fragments of dominant (or relatively dominant) histories to which I neither belong nor lay claim. Disappearance is a part of us – the line that connects my generation to even the one before is fraught with lost memory. Thus, interrupting the ideal of a singular body of work that endures for all eternity is also a way for me to affirm this mode of existence, one which lays bare the pretensions; the lie of the archive and the empire it sustains.

—

Published by Thread Makes Blanket, and available for order via AK Press. Here’s what some of our best contemporary poets have to say about it:

Oka has revisited her body (of work) with an intentional force that reclaims our losses and a skin-shedding so necessary that it redefines poetry. The lyricism in Oka’s poetry is enough to split a canonical rock open.

WILLIE PERDOMO

Oka’s mythmaking creates a landscape that calls on nature, the power of women, and the idea of writing and rewriting on the palimpsest of the destroyed and those reclaiming their power.

TARA BETTS

These poems are dazzling perceptive dream-songs strung out on a bridge crossing countries of land and ocean. They are built to hold loneliness, heartache, and the promise of happiness.

JOY HARJO

The bravery of crossing out and rewriting not only history but one’s own story, understanding the mutability of a tale, establishes this poetry as an inquiry into the wildness of interiority.

CINDY ARRIEU-KING

The official map’s mandates no longer apply. Just when you think the legends make sense, a nomad like Oka comes along to re-inscribe the lines.

PATRICK ROSAL

This compelling and revised edition speaks to women of color, migrants, survivors, mothers, laborers–all of us–to say: “you are stronger than / the ruins you carry, that salvage is not your / body.”

CRAIG SANTOS-PEREZ

June 9, 2015

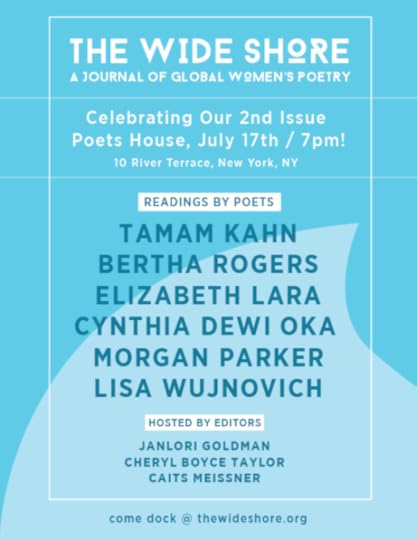

The Wide Shore at Poet’s House

Excited to be part of The Wide Shore reading at Poet’s House in New York this summer. Hope to see you there!

February 10, 2015

Missing Plane

in memory of the 239 passengers aboard Malaysian Airlines MH370,

which disappeared on March 8, 2014

I.

Language was the flight that disappeared.

At first the sky seemed strangely bare:

not like a coat with one lost button,

but a universe of coat where the button

has never existed. Soon, there is panic.

Because no one can close the universe

so it keeps flapping open and swelling

with cold. In the center of the button

there are threads, torn from the rest

of the coat, looping around each other

like hearts. The search begins in earnest.

Was the button loose to begin with?

II.

Within that question, needled by wind,

you rewind and fast-forward through

starless regions of the brain. Try to pin-

point to the second the flight’s last

heard of transmission. What was said,

by whom, why those words? Listening

to what you think was there, what will

neither reproach nor acknowledge you.

(Or is it air that has fastened its ear

to the walls of your soul? Is this God

saying goodnight?) This is how you fill in

the hole: with a lineage of broken sound.

III.

Then radar, and the work of spinning

heaven-bound bodies, which inform you

the flight wandered far over uncharted

waters. How? Who would steer it there?

The universe is beginning to feel like

nakedness. You tape paper over the cavity,

prick it with a hundred possible sightings.

Pattern will be your salvation, even as

your pulse moves through shark-infested

murk, aching to collide with damage

you can touch, taste. This is how the sea

you didn’t know was you, becomes yours.

IV.

For a brief time, the flight’s black box

sends out pings. When it is silent, there is

nothing but grief. The sky forever

blue and you beneath it, a cut thread.

Sometimes you dream you are the black box,

waiting to be raked up from the depths

to speak to that open wound, what happened.

Would you be able to wear the world then?

Would it embrace and warm your body?

Once a language was flung into the air.

Despite an extensive international

search no trace

December 9, 2014

Even If

in memory of Aiyana, Tamir, Michael, Trayvon, Eric

in hope of becoming who we have been waiting for

I.

The whiskey cooled to a nail

circles the scent of the chasm a boy

leaves behind – an anarchy of limbs

distilled to the muscular pattern

worn by those who daily sour

the ink on their fingers with bile

press them against the glass jar

of history: pickled skin, sparks

colliding in the canyons of skull

even as they dig heels their silence

into cement, a smear of faces

straddling the speed of a bullet

the city blooms. Hatred, body, fire

civil punctuations on the note

posted again and again like spit

of the poor, polaroid of the damned

to the wrong address: it’s never been

God, only pain that is incorruptible

II.

We throw the words down like planks

bound by the rags of our rage across

what physicists call an event horizon

They tangle, knock against each other

propelled by the engines that churn

color in and through us colored people

(the weak splinter in a rapture of dust)

We conjure the other side, homeward

glance to scrape us clean of metaphor

but the eyes resist direction, implode

on the present, shifting train of flesh

classified, prototyped, unrelenting bas

relief, language staggering upon us

(What is this us anyway? Stratagem?

Proverbial currency? Certainly not fact

unlike the ghosts that crouch in the pores

of our faces, sucking the salt of days

that tick by unresolved toward complete

survivor’s amnesia – by which we nod

in recognition at each other’s still life)

How my body empties when migrating

birds drag the sun out of the blue, that

kind of hollow, un-skinned, memory

loosened, damp world spinning away

nothing but I pinging from leaf to leaf

Give me the lie instead that gives me

weight, agony by which I earn my place

III.

Thanksgiving in lieu of sick marrow, tin scraps

laughing off the edge. Flirtation: jury convened

in defense of disbelief. Febrile air. Bone Thugs

& Harmony on waves and waves of ice. Even

the pulverized dead wafting in and out of lungs

“too heavy.”

IV.

A man I should not have loved said,

“There’s always guilt.”

I keep coming back to this. Stain on a favorite

photograph. I’ve never held

Michael. Aiyana. Trayvon. Eric. Tamir.

When vultures feed, what’s left is the hardness that angled

the body in ferocious light, revealed

futility. Come close, closer to see

my own blindness, the brutal demands of hope –

Chestnut Street, watching the city flex behind me

on the café window blood’s refusal

of skin’s ontology, even now

shafts of cerulean divide the streets, voices

muffled in the walls. The mouth on my neck

a lit match

V.

I can’t even.

I can’t even though.

I can’t even the odds (a man insisting the life he took was fiction).

I can’t even as hundreds lie prone on the piss-stained road, the whites of their eyes.

I can’t I can’t.

He said, “I can’t breathe.”

He said, “I’m tired of it.”

I can’t even with the dogs barking down the darkness, the dog I have been called.

I can’t even under camouflage of fire. Even with phoenix in my DNA.

There is a debt that must be paid.

I can’t even if you say peace.

December 8, 2014

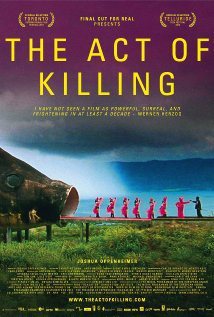

How to Watch The Act of Killing

My poem, “How to Watch The Act of Killing”, was recently nominated by Fifth Wednesday Journal, where it was first published, for a 2015 Pushcart Prize. I am truly amazed and humbled. Earlier this year, poet Rachel Jamison Webster had selected this poem for Fifth Wednesday’s Editor’s Prize in Poetry.

I had written the poem in response to the documentary, The Act of Killing, directed by Joshua Oppenheimer, a harrowing and necessary confrontation with the genocide that took place in 1965-66 against suspected (or alleged) Communists, leftists, union leaders, peasants and Chinese Indonesians. These events helped inaugurate decades of ruthless military rule, unchecked corruption, and relentless persecution of dissenters and minority ethnic groups under General Soeharto. Many Indonesian talents were involved in the making of this film, but could not be named because the people who committed these crimes – some of whom play central roles in the film – are still in power. So the acknowledgment for this poem is not for me alone; it is for all of the Indonesian artists, writers, thinkers, organizers, survivors who have or must remain Anonymous. I share this poem with my deepest love and respect, my pain and wildest hope, for them.

I had written the poem in response to the documentary, The Act of Killing, directed by Joshua Oppenheimer, a harrowing and necessary confrontation with the genocide that took place in 1965-66 against suspected (or alleged) Communists, leftists, union leaders, peasants and Chinese Indonesians. These events helped inaugurate decades of ruthless military rule, unchecked corruption, and relentless persecution of dissenters and minority ethnic groups under General Soeharto. Many Indonesian talents were involved in the making of this film, but could not be named because the people who committed these crimes – some of whom play central roles in the film – are still in power. So the acknowledgment for this poem is not for me alone; it is for all of the Indonesian artists, writers, thinkers, organizers, survivors who have or must remain Anonymous. I share this poem with my deepest love and respect, my pain and wildest hope, for them.

Read the momentous draft US Senate resolution, recently introduced by Senator Tom Udall of New Mexico, regarding the role of the US government in the perpetration of these mass killings and the ensuing 30+ years of military dictatorship under President Soeharto.

How to Watch The Act of Killing

Remember this isn’t real.

Though the fires laugh redly & the bamboo bleeds.

Black crowns of tualang trees & birds fall

like sleet. Beneath the shamed sun houses

shudder like goats at the stockyard.

Though the women’s faces purple,

their thighs licked by flames like corn husks.

Machetes wink & children’s mouths gape like eyes.

This is not the mathematic scene of torture

nor the wire’s political restraint –

you must believe

what is not really happening. Angels of death

rocking coal-flesh against their breasts, lips

kissing away terror’s foam, anointing

brows with cigar smoke.

Now the ones who play the prey – grandchildren & neighbors,

strangers and childhood friends – stare

sphinx-like through the screen. A make-believe memory,

myth shaped like a wail

looking for the body it belongs to.

Is this what you mean when you say homeland?

When you say heal & touch

please, these nerve-ends of separation?

Remember you are not there

whipped by the patriotic winds, imprinted

in sulfur, though you are

a child of the act of burning,

a child lost and smuggled to the seated side of the screen:

You must open your hands & hold

the fate that is yours,

which isn’t to decide who lives or dies or where

metaphor ends & pain is demoted

back to unthinkable pain, but to look again & again

at this blood of initiation, the hatred

that brought you here & stoops now

an old man behind the camera, sleepless, immaculate

in his suit & fedora surveying the great fresco of his life

your libraries of Anonymous,

your sparrow-less, silent world.

October 19, 2014

Current Projects

A few years ago, I read somewhere that the poet Audre Lorde revised her poems throughout her life. I love this idea, because as poets know, a poem is never truly “done.” As a living artifact of our lives, changing worlds, and evolving perspectives, poems have the capacity to transform, to become more of themselves at any particular time.

So when my first print run of Nomad of Salt and Hard Water (Dinah Press, 2012) sold out, I decided that instead of re-printing the same book, I’d go back in and see if/how the poems could grow as I have. I’m really excited to experiment with new possibilities for these poems that have been so critical for my development as an artist, while continuing to work towards the original intention and spirit of the book.

The original edition will still be available in e-book form. The new edition of Nomad of Salt and Hard Water will be published by Thread Makes Blanket Press.

~~~

I recently completed my second book-length poetry manuscript, Salvage, with great support from colleagues and mentors, and the time and writing space provided by my residency at the Vermont Studio Center. Thank you, everyone! I am looking forward to finding a home for this book. A sampling of individual poems from the manuscript (publication dates 2013/14) is available in the Publications page.

June 18, 2014

The Blog Tour: My Writing Process

I recently came back from a 2-week residency at the Vermont Studio Center where I completed my second book-length manuscript of poems. Since then, I’ve been meaning to write some reflections about my work and it’s nice to have the structure of a blog tour to do so. Thank you to both artists who invited me to participate – fiction writer Glendaliz Camacho and essayist/poet Seema Reza, both of whom I met through the Voices of Our Nations Writing Workshop. Check out their blogs – they really invite you to think deeply about what it means to pursue creativity and goodness in your life; they’re also often funny as hell.

OK, so as it goes, I’ll answer the four questions posed by the tour, and then tag two other writers to continue the thread.

1. What are you working on?

My second collection of poems is in many ways a response to the journeys initiated by my first book, Nomad of Salt and Hard Water. The muse of that project was a fierce, shape-shifting wanderer and myth-maker; she was tough, irreverent, elemental. She gave me the strength to make huge changes that paralleled the writing of the book – moving to the States, leaving my family/job/community behind, getting married, and beginning a life that was centered around my craft. I don’t think I was particularly deluded about what it meant to start over – I had been an immigrant before after all – but I really had no idea that poetically, Nomad had led me to the edge of a very deep and turbulent sea.

And it was not for a crossing. There was another muse beneath the waves, and for almost a year I wrote these super whack poems trying to get to her without straying too far from land. One lead that I did have was that I was (am!) extremely troubled by US drone attacks in Pakistan and would spend a few hours each day trolling the news, learning about the missiles and procedures behind the strikes, noting the names of dead and surviving, while trying to adjust to life in a small town in South Jersey, and to marriage, both of which were demanding me – at the risk of deportation if I quit! – to confront everything I was terrified of: loss of independence, intimacy, being truly seen.

What the hell was the connection? It wasn’t until I dove in that I could understand that what this new muse was asking me to do. I was unemployed, I couldn’t go anywhere, I was too broke to do anything but read and research – raw feeling that I couldn’t divert elsewhere and scattered facts were all I had to work with. So I started to mine, with poems, the wrecks in my history and the national/global histories that I am a part of. To understand how the debris implied and echoed each other across the borders of generations and communities, shaping what can and cannot be felt, much less articulated.

So I think the best way to describe the new collection is that it is an act of salvage. Of gathering the broken, rusted things allows us to glimpse where we come from, where we tried to go, the storms we could not weather. They sit at the bottom of us and form our foundation; in those swaying depths untouched by sunlight, they are our crumbling inheritance, evidence that even damage is a testament to life, to the possibility of recovery.

2. How does your work differ from others’ work in the same genre?

Hmmm…this question sounds like a veiled invitation to self-promote. I think the best way for me to answer is to define what I try to do relative to my imagined readers.

I ask questions and raise concerns that I really hope will resonate with others, that instead of creating a “niche” will foster self-questioning and conversations about certain realms of the human experience. In my second book, that means specifically war, displacement and violence against women – which have become so normalized in our economic and social landscape that it seems all we can do about them is have opinions (which we then post on various social media platforms to generate little fiefdoms of agreement. “To like or to not like, that is the question.”).

I would like to see these issues returned to the arena of human (both collective and personal) responsibility, and also, creativity. I think we need more creative, not rhetorical, ways of acknowledging these issues and how profoundly they have shaped us as a nation, an idea of humanity, how they inform what we can and cannot do with(in) our bodies and the spaces we inhabit. There is so much trauma all around us – it is in the anti-depressant commercials that run every ten minutes when Suits is on (a show ironically all about individual ambition, tenacity and self-sufficiency); it is in people’s obsession with Game of Thrones – a show so unapologetic about violence no wonder it’s cathartic for a society that otherwise operates on total denial about its own foundations of war, sexual violence and genocide; it is in Facebook memes that offer platitudes about joy, gratitude, cats, etc. and give us an excuse to look away from the homeless guy on the train who stinks with his own shit and is holding out his hand to anyone for change, a cigarette, mercy.

Rather than try “to get over” trauma, I think we need to converse with it. I think the key to the spiritual resilience and emotional creativity resides in that place where we are most afraid to breathe.

3. Why do you write what you do?

I write the specific poems that I do because the combination of my life experiences, the places I’ve gone, the books I’ve read, the ideas I’ve come across, the questions I’ve grappled with, and the craft I’ve studied have given me the tools to write these poems. I think of poets as vessels, and poetry chooses us to write this or that, based on what we can hold. I think of what Raul Zurita said at the Dodge Poetry Festival in 2013, “Things happen just for the poem to be.” Maybe that’s a mystical interpretation of my vocation, but it makes sense to me.

Beyond that, I write because I know what it is to feel powerless. And to write is to propose a particular version of reality, to claim its possibility – which is all power really is. So I write to teach myself that I have power, to make my power visible to me. I write because it is the condition of my freedom.

4. How does your writing process work?

Process for me is that which happens at the juncture of a specific project’s unique potential and one’s life circumstances. I find it difficult to boil it down to a series of steps. Instead I’ll mention the components that have been crucial for me.

The first is study. When I was writing my first book, I devoured collections. I wanted to understand what made a body of poems work – the sort of mechanics of it, but more importantly, the emotional and aesthetic composition, the possible routes it can take. With the recent project, I’ve been a lot more interested in collected works, in witnessing a poet’s experimentation with their craft over a lifetime, and how certain kinds of projects allow them to flex certain muscles – sound, form, metaphor, (il)logic – and the clarifying of their voice over time. All of this though, is to figure out what kind of poet I am and want to grow into, what kind of poems I really aspire to write. I find that good poems are those that make you want to be a better poet, and great poems are those that make you forget you are a poet, because they throw you back into the heart and madness and music that is humanity.

Second is discipline. This means at a basic level some sort of routine – because I’m a working mom, the thing that works for me is to wake up at 5 in the morning and write for a few hours before everyone else is up. At a more fundamental level though, discipline means a true submission to see the poem through – no matter how deep it asks you to go. Everyone does this differently, but for me it usually means many revisions and many overhauls, but also a practice of taking risks and feeling deeply in the rest of my life. If I stagnate, so will the poem. I’ve heard a lot of people say they don’t have enough time, to write, to revise, etc. Bullshit. If it’s important to you, you’ll make the time.

Third is self-ownership. In addition to the books I read, I think of my life as a kind of library. Each new experience allows it to grow. I think sometimes it’s possible to get stuck in one section (as a kid all I wanted to read was comic books, and only certain series at that) and forget that there are like eight floors still left to explore. I was in denial for a long time, for instance, about my Evangelical upbringing. I felt ashamed of it, not only because it was a culture of shame, but because I was hanging out with all these lefties and commies who were oh-so-disdainful of anything that even remotely smelled of God. But I grew up on the Psalms. They were the first words I learned to speak, quite literally. In addition to this, my original artistic endeavors were painting, singing, piano and dance. And whether or not I’m conscious of it, I draw on those original trades to write my poems. I think in images (what are the colors, what is the relationships between this and that object, where is the source of light, etc.) and movement (how fast, how curved, etc.), and in voice (what is the tone of the line, how does it move across the tongue, etc.). And yes, I think in God – not Jehovah-God, but in that mystery (or abyss) that stares back at the individual from the brink and fractures what we think we know.

Lastly, solitude. I don’t have my own office. I have a corner of the kitchen table during the wee hours of the morning. While a physical set-up can do wonders (e.g. while in Vermont I had my own studio overlooking a river), I can’t stress enough how critical it is to nourish an inner world that only I have access to. As much as possible I use my commute for solitary practice – though it’s crowded, I get to be an anonymous atom and really nobody gives a shit who I am or what I can do for them in that 30-45 minute period, twice a day. I can get lost in my thoughts and daydreams, in poems I’m reading, I can ask dangerous questions of myself in that envelope of time. Being a poet is a lonely road, but I don’t think that’s necessarily because the practice requires solitude. I think the loneliness comes from a heightened state of self-consciousness that results from being told (and believing) that we are different, “special,” misunderstood, etc. If anything solitude is where I feel most connected to the planet and the lives of others, because it is in solitude that I can give them the attention they deserve.

The Tour Continues!

Vicente Lozano is a writer based in Austin, Texas. He is the recipient of a post graduate fellowship from the Michener Center for Writers and he’s also participated in Macondo, Sandra Cisneros’ socially engaged writing community. In 2007 he received a Dobie-Paisano Fellowships from the Texas Institute of Letters and he’s also received several artist grants from the Vermont Studio Center, which is where I met him! He is an amazing human, super sharp but so grounded and thoughtful – I can’t wait to hear how he will answer these questions. He is also probably my favorite Tweeter – you can follow him @vtlozano.

Rajiv Mohabir is the author of the chapbooks na bad-eye me (Pudding House Press, 2010) and na mash me bone (Finishing Line Press, 2011). In addition to being a VONA (which is where I met him) and Kundiman fellow, he received his MFA in creative writing and literary translation from Queens College, CUNY. He has been published in Prairie Schooner, Crab Orchard Review, Drunken Boat, Great River Review, Assacarus, Anti-, small axe, Lantern Review, Four Way Review, and Saw Palm, and in 2010 he was nominated for a Pushcart Prize. He’s currently a PhD candidate at the University of Hawai’i, Mānoa. I’m a serious fan of Rajiv’s poetry and existence in the world.

June 15, 2014

Guest Blog: Sevé Torres on the Oasis Within

Blue Cliff Monastery is a Buddhist monastery in Pine Bush, NY in the tradition of the Plum Village, and Thich Nhat Hanh. The retreat I attended was for people of color and every day I felt the presence of love, mindfulness, Sangha, Buddha, Thay, and an internal movement toward peace. This retreat was the first moment I have had to breathe in almost three whirlwind years of life changes and transformations. It was also the first time I made a choice of my own, for myself and for others around me, to take the Five Mindfulness Trainings.

Great Harmony Meditation Hall has high, vaulted, wooden ceilings and a smooth pale hardwood floor. I walked in as one of the Sisters was telling Vonda that she could sit in the center since she was someone who would be receiving the trainings. The mats and cushions we were to sit on were set facing the front of the hall, while the others were turned to face our cushions directly. I walked mindfully through the center of the cushions sitting behind her, a bit worried about my ability to sit without shifting or massaging the parts of my calves and feet that would surely get numb. My knees lack flexibility and while I am able to sit with my legs crossed, I cannot yet sit in even the half lotus position. As the monks and nuns entered the meditation hall and took their positions facing us, I felt a deep sense of how important the event I was about to undergo was. All around me sat my sisters and brothers in the practice, and I felt a wave of anxiety leave my body.

Danielle, Odie, Vonda, Queen, and many others played a role in how important this ceremony was for me. Their presence on those center cushions allowed me to feel a great sense of peace and serenity. Lex who was sitting behind me allowed me to feel like I was not alone in my inflexibility, perched on his knees three-meditation cushions beneath him. Some of us would take all five trainings, some of us would take a few, but in that moment when the monastics began to chant and Brother PK led the ceremony I experienced one of the most profound spiritual moments of my life.

Colonization has taken many rituals from people of color and labeled them primitive, illogical, and pagan. However, in that moment, by our own free will and in the support of the Sangha I felt like we had gotten them back. This moment felt like home. The bowing in gratitude, our foreheads and palms touching the earth, the open heart receiving the words, the body straining to remain calm and centered, the affirmation in response to questions in front of the community, and the chanting felt like we had arrived in a moment of pure awareness and love.

After the ceremony had ended we walked up to our dharma discussion leaders and they handed us our Five Mindfulness Training Certificate, a document that in addition to containing the information of that day, also contained our dharma names. These names we were later told are usually aspirational, and that we should meditate and return to these names often in our practice. The name I received was Healing with a Peaceful Heart. We practiced hugging meditation with those around us, those in the Mountain Family, and those who we had built a kinship with while at the retreat. And in the embrace of my brothers and sisters in the practice I began to see what my dharma name had the power to liberate within, as I tasted true happiness.

When I returned home, my body was flooded with emotion and the world’s speed was and is still a bit disorienting. The ways I had made others suffer, and their own suffering confronted me almost immediately. I was reminded of habit energies as my speech wound its way through the air unskillfully. I was reminded of how the five mindfulness trainings are a practice, and how returning to our breath and steps can create spaciousness. At times my eyes would well and I would observe the feelings going through me as I touched the present moment.

Not long after I arrived home I encountered this passage while reading Sister Dang Nghiem’s book, Healing: A Woman’s Journey from Doctor to Nun:

“When we love someone, it’s not because we live next to the person that we love him or her. We love because we can see the beauty in that person, and we learn to love him in a way that he lives inside us. We can see the suffering and shortcomings not yet transformed in that person, and we practice wholeheartedly in order to help transform those things for him. That is true love.” (138)

The path I must walk begins with one step and it helps that I feel the support of my brothers and sisters in the practice however far away they may be. I also have tools and my breath to allow me to return to the present moment and create the spaciousness, reverence for life, true happiness, deep and loving speech, true love, nourishment and healing that I will need to become of aware of my suffering and transform it. As Thay says, “Pain is inevitable, but suffering is optional.” Now I can notice the pain in my body, my mind, and my heart and embrace it with my awareness. Now I can truly take my first steps in the present moment: each step truly a wonderful moment.

-Sevé Torres

March 17, 2014

Sounding More Like Ourselves

…is how the great poet and playwright Derek Walcott characterized the heart of a writer’s struggle, our internal mark of achievement and satisfaction, over a lifetime. What does this mean in a literary world held captive by the MFA industry, surveilled by government agencies, policed by the comforts of whiteness, maleness and empire, and molded by academic trends that not only inflect little of the everyday person’s besiegement by debt and meaninglessness, but are in fact fully complicit in reproducing that misery at a grand scale (witness the plight of adjunct faculty)? I also wonder at a practical level, what does this mean when I don’t read and write in my native tongue, but in a language designed to subjugate and exile me from my history? It’s rather like trying to find one’s true reflection in a house of distorting mirrors.

I don’t have any resolutions, but I think these are questions worth wrestling with. As an early writer, I believed that my reasons for writing had to do with socially just reasons (which makes sense because women and people of color do not have moral permission in our society to do anything simply because we feel like it) – to witness injustice, to defend against disappearance, to reveal what was erased, etc. Then the pendulum swung to the other end – I became convinced that I was writing to save my own life, to heal my own pain, to reconcile with the world of loss. I’m sure my reasons will change again, but at the “completion” (in quote marks because no writing is ever finished) of my second poetry manuscript, I realized something profoundly liberating: that no reason can ever encompass the practice of writing. What I thought were reasons were no more than the circumstances and conditions for my specific experience of the practice. We don’t ask a flower why it flowers and even if there was an answer, I think it would be a circular one: it would flower to discover what kind of flower it was. It is the outside gaze that demands a reckoning, the scientist/the god/the academy that demands the justification that this trait/this poem be part of a bigger plan, an evolution, an argument for our lives. But I’d like to put out there that when it comes to writing, trauma is not the culprit or point of origin. Trauma is an environment that requires our adaptation.

One more thought. Notice that Walcott does not say “to sound like ourselves,” but, “to sound more like ourselves.” Voice is such an integral thing to people who have experienced historic and systemic silencing, but self is not reducible to voice. Nor is voice reducible to self: it is a social artifact, while it might be of me it will have to live out there and find resonance independent of me to have any lasting value. A similar relationship pertains with language – neither can the self own language or be engulfed by it. Or at least this is what I believe and find comfort in, that I am as much what I cannot bring to say, as I am what I articulate. Somewhere between self, voice and language, is writing, like needle and thread, patterning leakages, sites of osmosis and blending, but also boundaries, limits to metamorphosis, what is inalienable to us and will not be breached.