Deepanjana Pal's Blog

September 14, 2024

The Gods of Kaos

This is not an ode to Jeff Goldblum, even though he is magnificent as Zeus and the reason I started watching Kaos; and Nabhaan Rizwan, whose performance as Dionysus is a fantastic blend of comedy and pathos. Neither is this a review of writer and creator Charlie Covell’s excellent show, which reimagines stories and characters from classical Greek mythology. The show is lavishly-imagined, has a dazzling cast, does a fantastic job of using music as a storytelling tool, and has been masterfully directed by Georgi Banks-Davies and Runyararo Mapfumo. Ok, those two sentences were a mini review, but that’s not the point of this post.

I’m here to preface this week’s column, which was first hard to write and then hard to compress. I don’t usually bring personal…stuff into my work writing, but this one time, it felt appropriate. Anyway, after much wrangling, chopping and rewording, I thought I’d managed to cut the column down to size for print, but I was wrong.

So the compressed version is here, in today’s edition of Hindustan Times and the unedited version is below.

Towards the end of Netflix’s hit series Kaos, king of the gods Zeus hosts a watch party. He invites Hera, Poseidon and Dionysus over to Olympus to witness the devout President Minos disprove a prophecy that states he will be killed by his child. In this fascinating alternative reality that creator and writer Charlie Covell has imagined, the gods breathe the same air as mortals and every human is born with a prophecy, written for them by the Fates. It turns out Zeus was once a mortal and his prophecy says his family will fall, allowing “Kaos” to reign. Even though Zeus has long cast aside his humanity to become the thundering deity that he is in the present, the appearance of a new wrinkle reduces him to a nervous wreck. He begins to suspect his prophecy has been set in motion and spirals into maniacal cruelty as he attempts to outwit fate and convince himself that his godliness is intact.

In Kaos, the gods have a range of powers, but the most important symptom of godhood is immunity from death and the source of this divine immortality is Meander water.

(The Meander at Olympus, in Kaos.)

This elixir is — SPOILER ALERT — drawn from dead humans. On earth, people live god-fearing lives in the hope of being “renewed”, or rewarded with a better life when they’re reborn. However, reincarnation is a fiction peddled by the gods. In truth, those who seek renewal end up in the Nothing, a secret part of Hades’s Underworld where the dead stand in silent, frozen agony. Their essence is harvested to create Meander water, which comes up as a gravity-defying, circular fountain in the gardens of Olympus. Zeus, Hera and Poseidon repeatedly dismiss mortals as contemptibly puny and flawed. It’s only when we realise what they already know about the Meander that Kaos’s core irony is revealed — it is the essence of humanity that makes the gods divine.

Coming back to the watch party: President Minos is ordered by the gods to upend his prophecy so that Zeus may be reassured that the will of the Fates can be defied. And so the gods gather to watch a man enter a labyrinth of dungeons, dagger in hand, to kill his son.

A curious parallel unfolds as this particular moment plays out in Kaos. Just as the gods sit in Zeus’s home to watch Minos on an vintage-inspired TV, so do we watch the gods (and Minos) on our screens at home. What we see mirrors what the gods of Kaos see, creating an Escher-esque illusion of screens reflecting one another. If Minos and other mortals are playthings who are idle entertainment for the Olympians, then Zeus, Hera and the others in Kaos are much the same for audiences around the world. They’re doing their best to dazzle us in the hope of being renewed for successive seasons; much like the humans in Kaos live in hope of “renewal”. (Covell must have noticed the meta possibilities of using that particular word in her world-building.)

The way Covell and the show’s directors set up the screen-within-the-screen sequences turns audiences into the gods whose entertainment are the on-screen gods; just as humans in the show are for Zeus, Dionysus, Hera and Poseidon.

Though the gods revel in their powers, Kaos quickly establishes that humans are quite beyond their control. Zeus, Hera and Poseidon do their best to manipulate events and people to do their bidding, but with little actual effect. The situation is similar with the show’s off-screen ‘gods’. The importance given to views, engagement and box office earnings make audiences seem powerful and influential, but we have little actual say over what is commissioned, released and platformed. For instance, a second season of The Rings of Power is out on Prime Video despite a first season that was disappointing both in terms of critical reception and also viewership numbers. In contrast, the historical fantasy My Lady Jane was well-received and developed a cult following after its release, but still got cancelled instead of getting renewed for another season. Despite this, My Lady Jane remains a significantly better work and a more entertaining watch than The Rings of Power, the renewal of which appears to have more to do with Amazon founder Jeff Bezos’s ego and Amazon Studios wanting a franchise to milk.

Kaos effectively sets up a hierarchy based on knowledge and power that includes the audience in its structure. At the bottom are the mere mortals, who live their everyday lives shrouded in illusions and lies propagated by the gods. For example, Pious Agatha, who offers herself as a human sacrifice to Olympus, is convinced her devoutness will earn her renewal, but she ends up in the Nothing. Above these humans are Zeus and the Olympian gods, cocooned in their belief that they’ve got humans under their control. The audience on the other side of the screen occupies the next higher rung because they know what the gods don’t know (but Kaos’s fabulous trio of Fates do): Free will is a confounding detail and love can upend best-laid plans.

(Sam Buttery, Suzie Eddie Izzard and Ché as the Fates.)

During the watch party, Zeus and the other gods track Minos as he goes into the labyrinth. That they can do this makes them feel like all-seeing divinities (with snacks). Yet their perspective is limited to what Minos knows and sees — a detail we the audience know, because we’ve seen Ari, Minos’s daughter, enter the labyrinth earlier. Everyone, from Minos to the Netflix subscriber, acts under the illusion of having the power of knowledge, but for every rung of the hierarchy, there is a surprise.

Minos is surprised by the gods; the gods and Minos are surprised when they see Ari; the audience, the gods and Minos are shocked when Ari reveals everyone had misread the prophecy, and ends up killing her father. The only one unsurprised by the twists and turns is Covell, by virtue of being the show’s creator and writer. (Being the creator of an imaginary world isn’t power enough. Just ask George R.R. Martin, who wrote a thoroughly disgruntled post — which he later deleted — about House of the Dragon.)

Yet despite the knowledge and power that come with being the mastermind of Kaos, for Covell to turn what they have imagined into reality, they need the fake gods and real audiences. Without the ignorant others doing their bits, Covell stops short of realising themself as a creator. (Suddenly, the detail that the Fates are non-binary, like Covell, feels significant.)

Whether it’s Zeus devouring news reports on the disasters he’s unleashed, or Hera eavesdropping on people in confessional boxes, the humans give the gods a sense of purpose. The divine of Kaos don’t necessarily need worshippers, but they do need humanity. Mortals make the immortals feel alive and literally give the latter their powers. We as viewers have a similar relationship with art. We turn to it for comfort, distraction, inspiration and more. We approach it with a sense of entitlement, offering little in return; as though art’s existential purpose is to be consumed. Yet Covell’s retelling of the Greek myths, with wonderful additions like individualised prophecies and Hera’s Tacitas (who put the mute in mutilated), is brilliant and richly creative whether or not it hits Netflix’s top 10. Similarly, the magnificent performances by the cast of Kaos — particularly Jeff Goldblum as Zeus, Nabhaan Rizwan as Dionysus, Janet Mc Teer as Hera, Stephan Dillane as Promtheus, Michelle Greenidge as the Tacita and Misia Butler as Caenaeus — don’t become any less accomplished if Netflix commits the mortal sin of not renewing the show. They may have been commissioned for our entertainment, but what they’ve eventually created along with the rest of Kaos’s team exists independent of the audience.

Of course, being a consumer of culture doesn’t have to feel as exploitative as Zeus and the gods are with humans. Over the past two weeks, my family and I have had to grapple with the jarring reality of my father being diagnosed with cancer. We’re living in hope that the disease can be beaten into remission and while we soldier towards whatever is fated, I find us turning to art in different ways. My mother stayed up nights adapting a short story into a short play for an amateur theatre group to perform during the upcoming Durga Puja. Yesterday, Hindustani classical singer Manali Bose’s intricate taankari rippled through our home after my father found a video of hers while on social media. Last week, after an impossibly long day, Mohammed Rafi sang “Main Zindagi Ka Saath Nibhata Chala Gaya” to the three of us.

We sat in our study, where three walls are stacked with books of fiction and non-fiction, collected and inherited, and Rafi crooned about turning every concern into flyaway dust. We sat in a silence that carried in it both our fatigue, but also our determination to find every little joy we can in defiance of this situation; to hold hope in our sights; to marvel at the enchantment of Rafi’s voice.

The song is from the 1961 film Hum Dono and Rafi died decades ago, as did music director Jaidev and lyricist Sahir Ludhianvi. Yet here we were, drawing on their magic as though they were in the room with us.

In Kaos, the Nothing is an archive of souls that seems infinite. Its closest equivalent in the real world is perhaps the internet, with its algorithms that petrify us into lifeless, agency-less versions of ourselves. Yet early adopters of the internet like me know that is not all the digital space can be. We discovered worlds through the internet and felt like gods because of the way the medium let us defy boundaries of legality and geography to access works of art that were gatekept from us by institutions and commerce. We became better versions of ourselves because of what was online.

Even though it is today threatened with stagnation and toxicity, the internet is also a realm in which humans have been at their most inventive, where art and artists thrive and become immortal. It preserves work, ensuring art is not lost and may be found by those who need it. In a way, the song from Hum Dono has become eternal despite being a relic of the past because it is online and just a click away. It loses nothing with each listen. If anything, the song comes a little more alive because new memories are made around it. The melody swats despair away with every determinedly upbeat note, and I’m reminded of a line spoken by the one character in Kaos who can restore life to the dead: “All the best things are human.”

August 3, 2024

Wolverine Kaku and Other Pleasures

I’m starting a fortnightly column with Hindustan Times, titled D for Drama. Having been spoiled by the internet in recent years, I really struggled to stick to the word count while writing this first column. Here’s to rediscovering the discipline and succinctness that print demands of writers in time for the next column. For now though, here’s the unedited version (you can read the edited column here):

It’s a morning show of Deadpool and Wolverine in the middle of the week, but this cinema in south Kolkata is almost full. In the queue for 3D glasses, a young man is on the phone. “Right now there’s an important family event that I can’t get out of, but I’ll be available after lunch,” he says. When he hangs up, his companion teases, “Family event, huh?” The young man solemnly replies, “I’m here to pay my respect to Deadpool-da and Wolverine kaku.” “Da” being the diminutive form of “dada” meaning older brother and “kaku” meaning uncle in Bengali.

I lost sight of this distant relative of Deadpool and Wolverine once inside, but he must have contributed to the resounding cheer that filled the darkened room when Hugh Jackman finally lost his shirt in the film’s predictable climax. Deadpool and Wolverine is more of a mediocre comedy special by Ryan Reynolds than a film, but the bar is low for superhero movies these days and Reynolds’s real-life superpower is marketing. Until the first Deadpool film made $782 million(ish), no one thought this character would strike a chord with audiences. Yet watching Reynolds play him, it’s makes perfect sense that a trash-talking motormouth who presents himself as a truth teller is so wildly popular in this era of trolling and internet personalities.

For many today, social media handles are akin to Deadpool’s superhero suit, simultaneously offering anonymity and a distinctive persona. The virtual world is performative, but it values honesty above (almost) everything else. Online performances and virality may be steeped in artifice, but despite this they often end up platforming uncomfortable truths. Deadpool embodies (via Reynolds’s muscular physique) precisely this multiplicity, especially in this latest outing in which Reynolds deliberately blurs the boundaries between punchlines and life experiences. From savagely running down his past films to cracking jokes about Jackman being a divorcé, Deadpool turns reality into a card trick. He’s as honest as he is deceptive — and the fans love it.

If you wait for Deadpool and Wolverine to arrive on streaming, you’ll miss what makes it fun — the experience of watching the film with fans who react volubly to whatever shows up on screen. It doesn’t matter if you haven’t followed the saga of the Fox and Disney deal, but you will grin at the jokes Reynolds cracks at the their expense because of the surrounding laughter. Similarly, you may not give two hoots about whether Henry Cavill is the next Wolverine, but when Deadpool promises “Cavillrine” he’ll be much better treated by Marvel (a reference to Cavill being unceremoniously dropped by Warner Bros), you’ll probably crack a smile.

And when Wolverine stands shirtless before you, you will add to whatever noise the audience is making to express collective lust, adoration and visceral acknowledgement that the path to a body like Jackman’s is not paved with fish fry, biriyani and mishti. Even if you called him “Wolverine kaku” 120 minutes ago. Uncle can stay standing; we’ll all be seated.

Culturally speaking, there seems to be a skittishness we feel about depicting older men as desirable. It’s tempting to imagine this is the net result of feminists pointing out how power imbalances between genders have been normalised and romanticised. However, it’s more likely that being desirable still doesn’t come with associations of respect and veneration. Conventionally, it’s been associated with sin and femininity. God forbid we tar men who are effectively the elders of our societies with that brush (insert outraged gasp here). At the same time, who doesn’t want to feel desirable? Topping the list of those who do are ageing men, haunted by the spectre of becoming irrelevant.

This is possibly why we’re now getting so many films in which heroes establish their desirability through feats of physical strength that are graphically violent, but also involve a striptease-like unveiling of the body. It’s unerringly similar to how the virility of a romantic hero (usually, a younger man) is showcased using the device of a love scene. Both flash their bodies and for the same reason — to entice the viewer — but the mood is starkly different. The hero of a romance is one we’re encouraged to (respectfully) objectify. When the hero is an older man, the genre is invariably action and desire is sublimated so that it can appear disguised in violence. Just think of how everyone’s hormones erupted at the sight of the wrinkled ‘zaddy’ Shah Rukh Khan in Jawan, whose action scenes are choreographed to showcase the actor at his sexiest. When the silver foxes aren’t ready to retire and can flex the muscle of a loyal fanbase in a way younger, less-established heroes can’t, action movies seem to be the safest option. (Deadpool teases Wolverine that he’ll be doing these movies till he’s 90, but chances are higher that this would also be Reynolds’s fate, given Deadpool is a masked hero.)

Fighting is very much the love language in Deadpool and Wolverine; so much so that thanks to one particularly spectacular fight scene, the Honda Odyssey has become to gays what U-Haul is to lesbians (or so Tumblr informs me). Unleashed by the film’s R rating, Deadpool is committed to poke you in the eye with the subtext, using his commentary to decode every tight close-up and innuendo-laden dialogue. Yet despite being anchored by a gleefully foul-mouthed hero, to protect tender sensibilities from being unsettled by the film’s erotic and homoerotic possibilities, Deadpool also falls back on comedy. Now, that moment when you felt tingly is a build-up to a punchline, rather than a tricky moment that holds a mirror up to your longings. Phew!

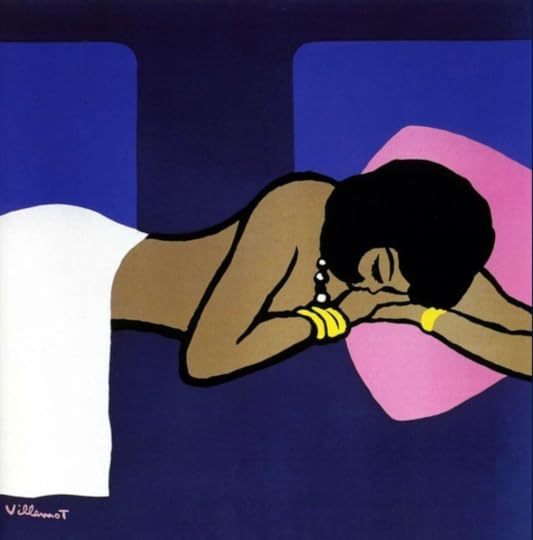

A rare recent work that leans comfortably into desire for the male body is Asim Abbasi’s show Barzakh, starring Fawad Khan and Sanam Saeed among others. The six-episode show quickly unravels into becoming unwatchable, but it begins with a gorgeous sequence, in which cinematographer Mo Azmi and actor Khushhal Khan perform the extraordinary feat of making the thin moustache seem impossibly sensual. Desire is a dangerous, forbidden thing in Barzakh, but Abbasi and Azmi celebrate it through beautiful, fragmentary moments, like the scene in which a young boy watches a man bathing or when Fawad puts kajal in his eyes.

The show’s production design and cinematography are its saving graces even though they ultimately can’t compensate for Barzakh‘s misguided attempts at being poetically layered and intelligent. Yet every now and then, breaking the tedium of its overwrought storytelling, are portraits of tenderness and longing between men. The show’s infatuation with beauty give the viewer some exquisite, unsettling moments. Moments that turn two-dimensional visuals of a scene into something almost tactile; all because of a gaze framed by desire.

When it comes to the small, more private screen for streaming entertainment, romanticism remain audience favourites across the world. Maybe it’s the way desire reveals our vulnerabilities or the way it levels the unevenness of the patriarchal playing field, but box office numbers suggest that when they’re in the cinema, in the company of strangers, audiences feel more comfortable with heroes who lash out rather than those who sit with their longings (perhaps thus nudging us to collectively do the same?). Still, it’s heartening to know that even in the middle of all things bland and messy, Wolverine kaku and others are taking moments to give us the pleasure of nainsukh.

July 28, 2021

Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities

June 15, 2021

June 5, 2021

Art thou Vincenzo

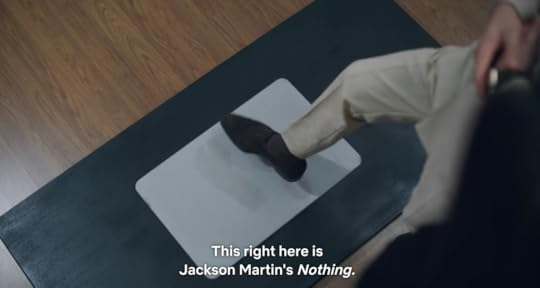

In episode 14 of Vincenzo, when our hero needs to get inside the office of the director of Ragusang Gallery to bring down the Korean tower of Babel, art comes to the rescue. The intrepid (and adorable) intelligence agent An Ki-Seok (Im Chul-Soo) finds out that the director keeps a celebrated but rarely-seen work of contemporary art in her office, which she shows only to select visitors. The work is by an American artist named Jackson Martin, costs approximately $90,000 and is titled “Nothing”. All Vincenzo (Song Joong-Ki) needs to do is to pose as a snooty collector and convince the director to show him “Nothing”, and hey presto! The director’s office will be opened up to him.

It all goes according to plan — with the added bonus of a much-awaited kiss between Vincenzo and Cha-Young (Jeon Yeo-Bin) — until the couple are in the director’s office and have to a) spot the artwork, and b) be suitably impressed by it. Because this is “Nothing”:

Vincenzo will see Salvatore Garau’s $18,000 “immaterial sculpture” and raise you the $90,000 “Nothing”, thank you very much.

Obviously, “Nothing” is writer Park Jae-Bum’s tongue-in-cheek comment on contemporary art. The director of the gallery explains that the sculpture, which Vincenzo initially mistakes for a doormat, examines “the emptiness of material culture” through the artist’s “sixth sense”. It’s almost as good a line as the one Garau delivered to justify his decision to present (and price) thin air as fine art: “After all, don’t we shape a God we’ve never seen?”

“Nothing” isn’t the only time art and art galleries make an appearance in Vincenzo. The art gallery pops up at three key moments in the show, each time creating a space in which romance can blossom, giving both viewers and characters some relief from the ‘real’ world beyond the gallery. Inside the white box, Vincenzo can set aside violence and instead flirt with attractive women against an artistic backdrop, like when he approaches a woman who agrees to testify against her husband so long as Vincenzo will go on a date with her (more on that later) or the meeting between Cha-Young and Vincenzo right at the end of the show. The implication seems to be that these are relationships that won’t survive outside the cloistered, unreal world of the gallery.

On the other hand, art is very much a part of the real world of Vincenzo. Much like the classical music in the drama’s soundtrack, the classical paintings in the production design offer a subtle commentary to the unfolding events, like footnotes in a text. They are details that are very deliberately included with director Kim Hui-Won making sure we don’t miss them. For example, at one point in the show, Vincenzo and Cha-Young corner an unscrupulous lawyer. When he’s blustering and denying the allegations of bribery against him, this is what the set looks like. Notice the clean and clear windows.

When he’s been exposed and is begging for mercy, this poster miraculously appears on the window behind him.

The idea of using art to signal the mindset of the characters in the foreground shows up again in the last episode, when Vincenzo and Cha-Young meet after a year at where else but a gallery.

The painting doesn’t come into focus at any point, but if you’re a fan of Caravaggio, then you’ll recognise it’s “The Seven Acts of Mercy”, which Caravaggio painted after he killed a man and was forced to flee Rome. The parallel with Vincenzo, who has killed way more than one man and is currently on the run, is obvious. We later learn that Vincenzo’s carrying out a lot of these acts of mercy on his private island, which is supposed to be a refuge for a chosen few. Like Vincenzo the Lover, Vincenzo the Merciful also seems to belong in a bubble, which is perhaps why we see him against the backdrop of “The Seven Acts of Mercy” in a gallery. The utopic island refuge he has built is cut off from the rest of the world. On the island, Vincenzo is the kindly, forgiving patriarch (albeit of an island owned by mafia); elsewhere, he’s the unforgiving devil in the impeccably tailored suit who walks alone and doesn’t hesitate to kill those he finds objectionable.

There are two paintings that occupy the foreground in Vincenzo. The first is a work from the late Middle Ages, which we see in the aforementioned unscrupulous lawyer’s office. When Vincenzo visits the office, he sees the painting and guesses that it’s hiding something.

Later, he breaks in and discovers a safe behind the painting. In that safe are all the bribes that the lawyer has received. In case you were wondering, the painting is “Kiss of Judas” by Giotto di Bondone. Yep, Judas, who sold Christ out for 30 pieces of silver, marks the spot where the sell-out lawyer stashes his cash.

And then there’s “Liberty Leading the People” by Eugène Delacroix, which gets by far the most fun treatment I’ve seen European art get in popular entertainment since René Magritte’s “The Son of Man” in The Thomas Crowne Affair. We first see Delacroix’s painting as part of an exhibition titled Palette of Emotion, where Vincenzo meets the wife of one of Babel’s morally-corrupt senior employees. It’s essentially a seduction scene in which — brace yourself — art criticism works as pick-up lines. Vincenzo’s opening gambit is to stand behind the woman and murmur, “War and art are best observed at a distance” (which we can conclude is a signature move since he repeats it when he meets Cha-Young against the backdrop of “The Seven Acts of Mercy”. His success rate is 100% and as any art critic will confirm, this requires way more suspension of disbelief than anything else in Vincenzo. That includes the pigeon god, Inzaghi. But I digress…).

So there they are, Vincenzo and the woman in a dead-end marriage, staring unblinkingly at a painting of liberty. When she takes a couple of steps towards him, he comes closer, all the while murmuring not sweet nothings, but details about Delacroix’s painting, like the use of colour and the flag that became a symbol of first the French Revolution and then France. It’s enough to make her pulse flutter, but Vincenzo has a final flourish — “She reminds me of you,” he says, indicating Delacroix’s painting of the goddess Liberty.

Next thing we know, the woman agrees to give a testimony in court against her husband provided Vincenzo will go on a date with her. If she’d asked him to come up and see her etchings, it would have been sheer perfection, but “Take me to see an opera” isn’t bad as euphemisms go.

Even better than Vincenzo using Liberty to liberate a woman from her unhappy marriage is the moment in which the ragtag bunch of Geumga Plaza tenants recreate Delacroix’s painting.

This scene is delightfully ridiculous and elegantly choreographed as the it goes from complete chaos to a structured but bonkers ode to “Liberty Leading the People”. Hilarious as the moment is, it’s also earnestly idealistic. The tenants of Geumga Plaza are similar to the people following Liberty in the painting — everyday folk who are either exploited or ignored by the establishment and those in power (and all of them vibrantly alive, unlike the painting in which the living are a minority and most are dead). Initially, the Geumga gang are a loosely-connected group, but in the course of the show, they become a proper collective that is empowered and resilient. They fight for their rights (very literally on more than one occasion), emerge victorious and stand by their principles. The hat-tip to Delacroix is the exact moment when the Geumga gang comes together as a collective.

Of course, they have no idea that they’re recreating a French painting, but that in itself is an ode to the timelessness of art. Almost 200 years after Delacroix painted “Liberty Leading the People” in France, it continues to feel inspiring and relevant to people in Korea.

There’s a sharp contrast between the affection and respect that Vincenzo accords to classical European art and the way the writing of the drama effectively dismisses contemporary art. While even a 14th century painting (“Kiss of Judas”) is shown as pertinent to the present, the present-day works in Ragusang Gallery, like “Nothing”, come across as elaborate, elitist pranks. “Nothing” is almost literally what the title suggests. Not just that, it doesn’t last. The work is easily vandalised and the only one who shows any remorse for “Nothing” being destroyed is the director of Ragusang Gallery.

This attitude is… interesting because modern art is usually treated with respect in K-dramas. A number of shows have artists as heroes or second leads (eg. Her Private Life and Run On). I find the art that we see in these shows to be mostly regrettable, but those in the world of the show are deeply appreciative of modern art as a vocation. The artists in K-dramas are invariably painters — rather than, say, performance artists or video artists, which are generally considered edgier, cooler genres — and through their work, modern art tends to be depicted as something that adds beauty and insight to a difficult world. Vincenzo in contrast shows little respect for contemporary art and artists. It’s adoration is reserved for historic, European art.

There’s something almost surreal about seeing paintings and artists in TV serials. Art is supposed to be highbrow while TV is decidedly lowbrow, but at least in K-drama, the twain do meet. Regardless of what kind of art is privileged, these shows present fictional worlds where creativity is a cherished part of everyday life and art isn’t just an indulgence for the moneyed and the privileged. Through the art that it showcases, dramas like Vincenzo send out the message that the imagination is something to be celebrated. Even if it’s called “Nothing”.

June 3, 2021

DRASTIC

Excerpts from this Newsweek article by Rowan Jacobsen

“The people responsible for uncovering this evidence are not journalists or spies or scientists. They are a group of amateur sleuths, with few resources except curiosity and a willingness to spend days combing the internet for clues. Throughout the pandemic, about two dozen or so correspondents, many anonymous, working independently from many different countries, have uncovered obscure documents, pieced together the information, and explained it all in long threads on Twitter—in a kind of open-source, collective brainstorming session that was part forensic science, part citizen journalism, and entirely new. They call themselves DRASTIC, for Decentralized Radical Autonomous Search Team Investigating COVID-19.”

“Thanks to DRASTIC, we now know that the Wuhan Institute of Virology had an extensive collection of coronaviruses gathered over many years of foraging in the bat caves, and that many of them—including the closest known relative to the pandemic virus, SARS-CoV-2—came from a mineshaft where three men died from a suspected SARS-like disease in 2012. We know that the WIV was actively working with these viruses, using inadequate safety protocols, in ways that could have triggered the pandemic, and that the lab and Chinese authorities have gone to great lengths to conceal these activities. We know that the first cases appeared weeks before the outbreak at the Huanan wet market that was once thought to be ground zero.”

“One important piece was an extensive Medium post by the Canadian longevity entrepreneur Yuri Deigin that discussed RaTG13, a virus Shi Zhengli had revealed to the world in a February 3 paper in the journal Nature. In that paper, Shi presented the first extensive analysis of SARS-CoV-2, which had seemed to come from nowhere—the virus was unlike any that had been seen before, including the first SARS, which had killed 774 people from 2002 to 2004. In her paper, however, Shi also introduced RaTG13, a virus that is similar in genetic makeup to SARS-CoV-2, making it the only known close relative at the time. … The paper aroused Deigin’s suspicions. He wondered if SARS-CoV-2 might have emerged through some genetic mixing and matching from a lab working with RaTG13 or related viruses. His post was cogent and comprehensive. The Seeker posted Deigin’s theory on Reddit, which promptly suspended his account permanently.”

“If there is a moment when the DRASTIC team coalesced into something more than its disparate parts, it would be this thread. In real time, for all the world to see, they worked through the data, tested various hypotheses, corrected each other, and scored some direct hits.”

“The genetic sequence for RaTG13 perfectly matched a small piece of genetic code posted as part of a paper written by Shi Zhengli years earlier, but never mentioned again. The code came from a virus the WIV had found in a Yunnan bat. Connecting key details in the two papers with old news stories, the DRASTIC team determined that RaTG13 had come from a mineshaft in Mojiang County, in Yunnan Province, where six men shoveling bat guano in 2012 had developed pneumonia. Three of them died. DRASTIC wondered if that event marked the first cases of human beings being infected with a precursor of SARS-CoV-2—perhaps RaTG13 or something like it.”

“In his online explorations, he’d recently discovered a massive Chinese database of academic journals and theses called CNKI. … Working through the night at his bedside table on phone and laptop, fueled by chai and using Chinese characters with the help of Google Translate, he plugged in “Mojiang”—the county where the mine was located—in combination with every other word he could think of that might be relevant, instantly translating each new flush of results back to English. ‘Mojiang + pneumonia’; ‘Mojiang + WIV’; ‘Mojiang + bats’; ‘Mojiang + SARS’. Each search brought back thousands of results and half a dozen different databases for journals, books, newspapers, master’s theses, doctoral dissertations. … He was on the verge of calling it quits, he says, when he struck gold: a 60-page master’s thesis written by a student at Kunming Medical University in 2013 titled ‘The Analysis of 6 Patients with Severe Pneumonia Caused by Unknown Viruses’. In exhaustive detail, it described the conditions and step-by-step treatment of the miners. It named the suspected culprit: ‘Caused by SARS-like [coronavirus] from the Chinese horseshoe bat or other bats.’ … (Shortly after The Seeker posted the theses, China changed the access controls on CNKI so no one could do such a search again.)”

“Within days, DRASTIC managed to locate the coordinates of the mysterious Mojiang mine, but it would not catch the attention of the media until late 2020, when a race to get there began. The first attempt was by the BBC’s John Sudworth, who found his path blocked by trucks and guards. (Sudworth would soon be forced to leave China because of his reporting.) The AP tried around the same time, with no better luck. Later, teams from NBC, CBS, Today, and other outlets also found their way blocked by trucks, trees, and angry men. Some were told that it was dangerous to proceed because of wild elephants. Eventually, a Wall Street Journal reporter reached the entrance to the mine by mountain bike—only to be detained for five hours of questioning. The mine’s secrets remain.”

“By examining some metadata tags that had been accidentally uploaded by the WIV along with its genetic sequences for RaTG13, Ribera discovered that scientists at the lab had indeed been actively studying the virus in 2017 and 2018—they hadn’t stuck it in a freezer and forgotten about it, after all.”

“Cross-referencing snippets of information from multiple sources, Ribera guessed, in a Twitter thread dated August 1, 2020, that a cluster of eight SARS-related viruses mentioned briefly in an obscure section of one WIV paper had actually also come from the Mojiang mine. In other words, they hadn’t found one relative of SARS-CoV-2 in that mineshaft; they’d found nine. In November 2020, Shi Zhengli confirmed many of DRASTIC’s suspicions about the Mojiang cave in an addendum to her original paper on RaTG13 and in a talk in February 2021.”

“When asked about the missing database in January 2021, Shi Zhengli explained that it had been taken offline during the pandemic because the WIV web server had become the focus of online attacks. But once again, DRASTIC poked holes in this explanation: the database was taken down on September 12, 2019, shortly before the start of the pandemic, and well before the WIV would have become a target.”

“But all the evidence DRASTIC has produced points in the same direction: The Wuhan Institute of Virology had spent years collecting dangerous coronaviruses, some of which it has never revealed to the world. It was actively testing these viruses to determine their ability to infect people, as well as what mutations might be necessary to enhance that ability—likely with the ultimate goal of producing a vaccine that would protect against all of them. And the ongoing effort to cover this up implies that something may have gone wrong.”

May 31, 2021

Full credits

Loved this show, and not just because I didn’t guess whodunit until about one-third into the last episode. The crime solving is well-worked out (mostly — I’m still not sure why Erin’s friend named Frank Sheehan when she knew who the father actually was). I loved the relationships between the women and how deeply flawed everyone is. The show also offers such an evocative portrait of small-town America’s helplessness as communities grapple with social change and crumbling fortunes. And yes, Kate Winslet is a goddess.

May 9, 2021

Vaccine fever

The queue for those aged between 18 and 44 years, with appointments to get the first shot of the Covid-19 vaccine, is about 100 people long when we join it. The only reason I’m in it is because I’m inordinately lucky. Luck is not a word that we should associate with a vaccination drive during a pandemic and yet… .

The day CoWin opened up to everyone — May 1 — the site crashed multiple times. I’m among those who couldn’t register, but Saumya did and she registered me under her number. For the past week, Saumya and I have been tracking BMC’s Twitter handle and multiple Telegram channels that ping each time registrations open. Hundreds of slots disappear in a matter of seconds. We both despaired. Every evening that we failed at this Hunger Games-meets-Kaun Banega Crorepati’s “fastest finger first” hybrid (aka phase three of India’s vaccination drive), I became a little more resigned to not getting the shot while Saumya got more determined to crack the system. There were still silver linings. I was able to alert three friends who had been struggling to find slots for their parents; two of them got appointments. We all cheered, as though they’re our own parents. Grief is not the only thing we share in the age of Covid.

By May 6, we’re seeing updates on social media of people who have driven as far as Thane, Navi Mumbai and Badlapur to get their shots. At some point, officials and locals in those areas will start grumbling about privileged, car-owning Mumbaikars “stealing” vaccines from them. Saumya and I did not consider those far-flung centres as options — it’s true that neither of us wanted to swoop in on someone else’s share of vaccines, but the primary reason for our higher moral ground was that we were not willing to go any further north than Ghatkopar. We’re happy to pay for the vaccine, but our upper limit for the commute was 13 kilometres.

Of course, no one should have to pay for these vaccines except governments, whose responsibilities include ensuring the welfare of citizens, but the world is anything but ideal. If the Indian government’s strategy behind allowing private hospitals to sell the vaccines was to ease the load on civic authorities supplying free vaccines, it doesn’t seem to be working (leaving aside the minor detail of this being an example of our government effectively encouraging private hospitals to profiteer from the pandemic). As things stand right now, private hospitals have to procure their own supplies of vaccines while states receive their supplies via the Centre. CoWin is the only platform through which you can book an appointment at either a private hospital or a government-run centre and there is no uniformity. The menu card of vaccines lists prices ranging from Rs 500 to Rs 900 in Mumbai. My mother tells me that it’s crossed the Rs 1,000 mark in Kolkata. Each municipal corporation has different timings for their slots. BMC opens registrations at 7.30pm on one day, 8pm on another, 7.45pm on yet another and the only way you can know this is if you’re stalking their Twitter handle. Private hospitals open their windows at different hours of the day — 2pm for one, 5pm for another, a third allows advance bookings if you check at 4pm on certain days of the week — and there are no formal announcements. Saumya and I have postgraduate degrees, we’ve worked as journalists for more than a decade, we have good computers and internet connections. If we’re frustrated by CoWin, how are those with unstable data networks, cheap hardware and limited English literacy negotiating this process?

Compared to the 500-odd slots that civic authorities open up daily, private hospitals offer approximately 100. They disappear in a second, sometimes less. Both Saumya and I agreed that we had a better chance of getting appointments at places with more slots. Saumya kept the CoWin page open on her computer throughout the day, logging in repeatedly, trying multiple times and noting the changes that were introduced without warning — an extra OTP here, a “secret code” there. Every evening, after failing, we spent a few minutes wondering how the bulk of the Indian population can even hope to crack CoWin (which has only an English-language version. Ironic, given most BJP members struggle with English and the party’s long campaign for Hindi supremacy). CoWin, developed and managed by the BJP government at the Centre, seems designed to be accessible to the least number of people and penetrable by only the most privileged. So much for a political party that projects itself as champion of the son of the soil.

The day it finally happened, I wasn’t even near my phone or computer, which is to say I was of absolutely no help to Saumya who didn’t plead off the staring contest with CoWin. That day, the bad news felt too much. I am safe, my families are safe, and yet I’m breaking under the weight of the updates that stream in through my phone and computer. Every ripple that reaches me shimmers with either death or the fear of it. That day, too many people had been reduced to a flicker of a memory. We were told as kids that sharing means there is more for everyone. I’m learning in my middle age that this holds true of grief and uncertainty.

And yet, I find that no matter how much I may want to build for myself a hiding place made of white noise and night-calm darkness, I spiral back to check for updates. I would rather know and retreat than be delusional like our government which believed the pandemic was over when cases dipped earlier this year and which continues to maintain CoWin is a functioning system and there are no shortages in the country. So I returned to my phone minutes after resolving to set it aside and found Saumya’s missed call. I called her back, my heart slowing down as though preparing for bad news even though I knew she and hers were fine. “Tomorrow, Nair Hospital, both of us,” Saumya said. It was as close to a miracle that we can hope for in our day and age. Saumya, my vaccine fairy, had got appointments for the first shot of Covishield.

Which is how we’re in a queue on May 8. We’re both carrying bottles of water in our bags. I am also carrying two bars of chocolate. Yet the fact is that given we’re in a hospital that treats Covid patients and standing in a socially-undistanced queue, I doubt either of us would lower our masks even if we were about to pass out with dehydration and hunger. Thanks to Mumbai humidity, my mask at this point is basically a receptacle for sweat. We look around to distract ourselves and spot a doll impaled upon the whorls of barbed wire on the boundary wall.

The line behind us has snaked beyond my line of sight. As far as I can see, it’s people like us — young, upper middle-class, smartphone-wielding and privileged. In the middle of a raging second wave, it’s true that every person vaccinated is a step in the right direction, but this queue should have been filled with those who have little choice but to brave the pandemic in order to make a living; people like drivers, delivery people, domestic help, grocery store workers. Instead it’s filled with people who can work from home. For people like us, it really is a free vaccine, but for those who are less privileged, there are hidden costs. These range from what the English-literate middleman will charge for trying their luck with CoWin; to earnings lost from first queuing up for the vaccine and then the potential side effects like fever, diarrhoea and body ache that knock most of us out for two days.

India has spent the last few decades pretending it’s a superpower and now, the bubble of that dream has been pricked by Covid-19. The pandemic has reminded us with brutal force that we are in fact a poor country with a crippled economy. We cannot afford the number of tests that we should be conducting, we cannot afford the gene sequencing that we should be doing to identify variants and their traits, and we cannot afford vaccines in the amount that we need them. As if all the complicated legalities surrounding patents and production of vaccines didn’t pose enough of a challenge to vaccine distribution, the BJP government has turned the vaccination drive into a publicity stunt. In April, possibly to boost the BJP’s chances in state elections that were being conducted at the time, the Prime Minister announced vaccination would be made available to everyone from May 1 even as states struggled to reach their targets of vaccinating frontline and healthcare workers. More people were testing positive, thanks to a second wave that was made infinitely worse by irresponsible election campaigning and the government’s decision to organise the Hindu pilgrimage festival of Kumbh Mela. (Both the election rallies that gathered thousands of people as well as the crowds at the Kumbh Mela proved to be super spreaders. There are now concerns that these large gatherings may have helped the virus to mutate into strains that may be vaccine-resistant.) Meanwhile, even as vaccination was opened up to everyone, vaccines were in short supply across the country.

While India broke record after record in terms of daily caseloads and made international news for under-reporting Covid deaths, BMC would close vaccination centres for three days because Mumbai had no supplies. Unnamed sources told Business Standard that the Central government, which is in charge of Covid management and the vaccination drive, had last placed an order for 120 million vaccines more than month ago, in March. Earlier this week, in May, the Centre announced it had (finally) ordered 160 million more doses of Covishield and Covaxin. Even so, Thane Municipal Corporation announced that tomorrow, there would be no vaccination for the 45+ age category — the targets of the second phase of the vaccination drive — because it doesn’t have vaccines. Earlier, there was a stampede in a vaccination centre in Mumbai and friends in Bengaluru described how they’d arrived and waited for hours at vaccination centres only to be told there weren’t enough vaccines by the time it was their turn. Doctors in India started spreading the word that there was no need for concern if you didn’t get the second dose after a month, as was originally prescribed; that the efficacy was better if the gap was extended; that you could even get the second shot after six months.

All this is to soothe the panic of the privileged, who want their security against this dreaded disease right now. Meanwhile, those most vulnerable to contracting Covid-19 continue with their daily lives, opening shops and cleaning homes and driving public transport. Not that we can begrudge anyone their anxiety. Covid is terrifying for just how unpredictable it is. Last year, rural India had felt safe against it, seeing it as a city illness, but this year, it’s ravaging the hinterland. The new variants of Covid-19 are more transmissible and this time round, more children are contracting the infection (last year, children were considered least vulnerable to Covid). In one person, the illness is a little worse than a common flu. In another, it can mean death in a matter of days or even hours. In the hellscape that is Uttar Pradesh and Delhi, the dead are being burned on pavements and parking lots, and the ailing are gasping for breath. Local newspapers in states like Gujarat have embarked on a campaign to show the discrepancies in the official count of Covid deaths. Goa recently reported a positivity rate ranging from 40-51%.

While the Prime Minister and other BJP leaders issue statements that claim the pandemic is under control and there are no shortages to speak of, the mismanagement is there for everyone to see. We’re receiving aid from across the world (though we don’t know who is receiving that aid on the ground in India) and individuals across the country are working round the clock to make Indian’s broken healthcare system somewhere close to functional. It is not for citizens to set up a healthcare infrastructure by establishing relief networks and organising everything from makeshift ambulances to oxygen cylinders, and yet here we are.

At Nair Hospital, it takes us a little more than an hour to reach the waiting area and I’m disoriented by how much it reminds me of a Durga Puja pandal. A skeleton of bamboo poles wrapped in fabric, filled with the faithful. It’s not loud inside, despite being crowded. A low hum of anxiety and unspoken prayers hangs heavy in the air. At the counter, volunteers check our ID, ask if we have any drug allergies, if we’ve had Covid-19, if we’re married. In another age, I would have asked what marital status has to do with vaccine safety or efficacy and why they’re assuming that only married women may be pregnant or if they’ve read the recent studies that suggest the Covid-19 vaccines are safe for pregnant women, but those are battles for another day. It is enough that these volunteers are here and doing this thankless, exhausting, anxiety-inducing job of talking to and brushing fingertips with strangers.

We do our best to touch nothing and no one in the pandal. They’ve lined up chairs for those waiting, but no one wants to sit despite having spent more than an hour standing. Next to our queue is another one for those getting their second shots. A woman in a white lab coat wanders into our queue and cuts in, right in front of Saumya. She doesn’t hear the nearby cop telling her she’s in the wrong queue. She doesn’t notice the stiff outraged bodies around her, of people who have seen her cut in. Normally, we’d tap her on the shoulder to attract her attention. Now we rely on telepathy. My gaze wanders to the vaccination slip she’s clutching in the hands interlocked behind her. She is a doctor, among those who were to be vaccinated during the first phase of the vaccination drive, which started in January. She’s come for her second shot now, in May. When she finally turns around, I notice the dark circles around her irritation-crinkled eyes. “Kuthey?” she growls angrily at the cop who has been able to get her to hear him. Where indeed. The lines are like shifty cells under a microscope. You see the order only if you know what you’re looking for. There are clusters of people grouped together, each trying to reach the vaccine counter quicker by attempting to expand distance from the one behind them and shrink the distance from the one ahead of them. It isn’t surprising that a fight breaks out in one corner. You can’t have this many privileged Indians in a room without at least one person trying to intimidate the staff. Nair Hospital, however, has been managing Covid and crowds for more than a year now. The raised voices and outrage are like water off a duck’s back. The angry older man sputters inconsequentially. Our line moves forward.

The actual shot takes less than a minute. There are eight counters and I’m sent to a woman who seems impossibly young, in scrubs that seem too large for her.

She tears off a fresh syringe from a strip, pulls out a vial from a green box, and I feel a pinch. It’s over before I know it. I’m now very impressed by the presence of mind of all those who managed to click photographs of themselves getting injected. It’s a dedication to photographic documentation — admittedly wrapped in narcissism, virtue signalling and leveraging social media — that I don’t possess. I’m more of a write-an-elaborately-long blog post kind of girl.

There’s barely a drop of blood on the cotton that she presses on my arm after giving me the shot. She warns me that the injection spot will hurt and that I shouldn’t massage it or apply ice or heat packs on it. “People do all that?” I ask her. “You wouldn’t believe the things men do at the slightest pain,” she tells me and I assume she’s grinning under her mask. She tells me to have Crocin if I get a fever, to be careful for the next two weeks and to come back for my second shot after 45-60 days. She’s utterly unflappable and calm. I thank her before leaving. “It’s my pleasure,” she tells me in English. I should have asked her name, but I’m too focused on blinking back tears. Also, there’s already another person hovering nearby, waiting to assign someone to my spot.

As I settle down in the waiting area, I give thanks to all the gods and to Saumya, who’s sitting right next to me. We exchange notes. Saumya reminds me that we need to take a photo of the two of us, newly-vaccinated as we are. She has family on another continent and these photographs make those faraway folk feel like they’re present in her life, despite the distance. I know the feeling. That’s how I felt when my parents sent me photographs of their vaccine adventure last month. As we wait for the minutes to pass, I notice we’re all women in this particular spot — saris, ridas, jeans, salwars, blingy chappals, sneakers, plastic kohlapuris. A little India, patiently waiting for the time when we will walk free and in the meantime, keeping the peace and the faith.

Twenty four hours later, when I’m feverish and aching, that waiting area will come back to me again and again. I find myself wondering how many of those women are feeling like I am, if someone is feeding them khichdi and giving them the Crocin.

May 2, 2021

Come for the Pretty Faces, Stay for the Storytelling

An edited version of this has been published in this week’s India Today.

Mainland India should have been the last place where South Korean entertainment would find fans. Ours is a country with its own thriving television and film industries. Culturally, we’ve been fascinated by the West, rather than our Asian neighbours. Our audiences aren’t known for embracing subtitles and are so parochial that no actress from northeast India was considered for the role of champion Manipuri boxer Mary Kom in the mainstream Bollywood film based on her life.

Yet, according to Netflix India, in 2020, there was a 370% growth in its Indian viewership of Korean television serials, fondly known as K-dramas. So what is it about this genre that has convinced Indian audiences to turn away from the macho men of desi entertainment, and towards the feisty heroines and impossibly pretty heroes of K-drama?

Mr. Queen

Mr. QueenWhile Korean entertainment has had a loyal following in northeast India for approximately a decade, the rest of India woke up to K-dramas last year. At this time last year, when we mistakenly thought we were going through the worst of the Covid-19 pandemic, K-dramas emerged as the antidote to lockdown blues. Escapist, unpretentious and time-consuming, K-dramas helped fill the yawning hours with something other than doomscrolling. A year later, neither the pandemic nor India’s love affair with K-dramas shows any signs of waning.

Not to discount the charms of Korean actors and their pore-less skin, but the key to the popularity of K-dramas lies in the storytelling. Like all popular television entertainment, K-drama has its share of cringe-inducing, melodramatic plots filled with clichés and regrettable twists. However, the K-drama industry also did something that went against the grain of show business in other countries. As part of its efforts to woo the female audience, the South Korean television industry actively hired women writers. Initially, women writers were inducted to write romantic soap operas and even now, both romances and romantic sub-plots remain an important element in K-dramas. However, women writers today write everything from zombie historical dramas to crime procedurals. In 2019, Forbes reported that almost 90% of K-drama writers were women.

The impact of women writers and an eagerness to cater to a feminine audience has given rise to certain tropes. These range from critically-important storytelling decisions like prioritising women’s stories and having strong, female characters; to trivial details like having at least two swoon-worthy male leads in each show and a gratuitous bathroom/ locker room scene featuring a male actor’s ogle-worthy torso. The tactic is simple and effective: come for the pretty faces, stay for the storytelling.

Vincenzo

VincenzoFemale leads in K-dramas are women who are imperfect, complex and charming. In historical dramas, they are almost always spirited and independent-minded while dramas set in the present have working women as heroines. They’re paired with men who are sensitive, supportive and do not feel threatened by successful, ambitious women. Today, irrespective of whether it has been written by a male or female writer, a K-drama will have two features: male characters who recognise women are not to be reduced to sex objects; and meaty roles for women actors. Rarely will a K-drama be set in a world that doesn’t include women in both minor roles as well as positions of power. Consequently, what we get is an alternative reality in which both men and women feel represented and present.

If you’re an alert viewer, there are often nuances that distinguish the writing of a male writer from that of his feminine counterpart. An example of how gender can add perspective to the writing is the difference between Taxi Driver and Beyond Evil’s depictions of violent crimes against women. In Taxi Driver (written by Oh Sang-Ho, a male writer), we’re shown a young woman being assaulted and tortured. To emphasise her helplessness, the camera lingers over her tortured body and the audience sees the young woman only as a victim who needs saving (by who else, but the male hero). Her only identity is that of the vulnerable woman victim (a standard trope of crime fiction) and she’s viewed through the male gaze of her oppressor.

In contrast, Beyond Evil — which in addition to being written by Shim Na-Yeon, a female writer, is directed by a woman (Kim Soo-Jin) — shows how patriarchal violence reduces a woman into an object. This is done very literally — a young woman leaves home to meet a friend one night and the next morning, all that remains of her are her fingertips. Without underplaying the gruesome violence of the crime, Beyond Evil finds different ways to ensure the victim is seen as a person, rather than simply the object of a serial killer’s passion. The dead bodies are all blurs and through flashbacks, we’re repeatedly shown the victims as people with lives unmarked by the horrors of their final moments. The woman’s body does not exist only as a site of violence in Beyond Evil. Even a minor character, who ends up as an unclaimed body in a morgue, is remembered as someone with a personality.

All this is not to suggest K-drama is a promised land of progressive storytelling. It is singularly lacking in diversity, occasionally homophobic and the beauty conventions it promotes are punishing. In theory, K-drama’s beauty ideals should have limited impact on us in India — most of us have very different features and colouring, which should make K-beauty standards feel like a fantasy rather than an achievable reality — but soon enough, Instagram will dangle ads for BB creams, sheet masks and lip tints before you, and at an ungodly hour of the night, you’ll end up buying them. Not as much because of the Instagram ad as the fact that K-dramas are a concerted campaign to sell products. The Korean beauty ideal — with its aggressive reliance on both skincare and cosmetic products — is among the more insidious but persuasive marketing campaigns. Most of the time, the hard sell is more obvious, like product placements for Subway sandwiches and Samsung phones (no one in a K-drama uses an iPhone). Occasionally, a show will have fun with it, like the way Run On abandoned its plot temporarily to poke fun at the romantic trope of gazing deep into someone’s eyes while advertising a brand of contact lenses.

Run On

Run OnYet, even as they remain focused on audience ratings and commercial success — after all, these shows are primetime television programming in South Korea — K-dramas are often both ambitious and idealistic. In these shows, the super-rich families are invariably dysfunctional while the middle-class home, with working parents and modest earnings, is shown as the ideal. Big businesses tend to be the hub of all villainy and frequently, those who work regular jobs are the heroes. Creative professions, like authors and artists, are glorified and just when you least expect it, the dialogue will casually sneak in a reference to Adam Smith, Slavoj Žižek or Martin Heidegger.

Along with high jinks, melodrama and product placements for everything from Swarovski jewellery to Kopiko candy, social commentary is also woven into the plots with subtlety. Twenty years ago, Coffee Prince explored gender and sexuality when it set up a romance between an entrepreneur and his apparently-male-but-actually-a-woman employee. Sky Castle took a hammer to elitism and the manic competition that underlies the college admission system in South Korea. Crash Landing On You, one the most successful K-dramas of all time, presented a cross-border romance that didn’t reduce the North Koreans to evil caricatures. Stranger and Vincenzo examined corruption and the way people in positions of power manipulate the lives of the less-privileged. Into the Ring, which seems to be a romance but is actually a David-and-Goliath contest between an idealistic citizen and the political system, pushed for more women joining politics.

Writing (and directing K-drama) is an epic assignment, beset with challenges. Each show is between 16 to 20 episodes long, and the duration of each episode is at least 60 minutes. This means the plot has to unfold over a minimum of 16 hours and each episode is almost a feature film in itself. Scripts must follow the strict guidelines laid down by Korea Communication Standards Commission (KCSC), thanks to which cigarettes are never lit, knives are blurred out and romances in K-drama are practically Victorian in sensibility. Shows can take anywhere from eight to 14 episodes to build up to a single kiss and sex scenes are about as rare as copulating pandas in the wild. Yet fans will tell you that the conversation-heavy slow burn of K-drama romances feel more satisfying than graphic scenes from other foreign shows. Everyday banalities are charged with chemistry so that there’s more sexual longing packed into a casual touch than in most sex scenes. Plus, there’s the added bonus of not needing to worry about either your dad or domestic help barging in while you’re watching a romantic scene.

In February, Netflix announced it would spend nearly $500 million on films and television shows produced in South Korea as part of its mission to be the one-stop shop for K-dramas in Asia. That’s good news for the Korean entertainment industry and it’ll be interesting to see how K-dramas respond to the creative space that companies like Netflix offer writers and directors. In the meantime, perhaps the popularity of K-drama in India will be a wake-up call for the Indian entertainment scene. Especially during the pandemic, all Indian creators have no option but to pin their hopes on streaming platforms, which means Indian shows may well find themselves in direct competition with K-dramas for audiences. Already, shows like Vincenzo, Run On and The Uncanny Counter have been on Netflix India’s most-watched shows. Considering the mediocre quality of much of the Hindi programming on streaming platforms, that’s not good news for Indian writers and directors.

Stranger, behind the scenes

Stranger, behind the scenes

April 12, 2021

Enjoy Enjaami

I actually found my way to the song “Enjoy Enjaami” because of an interview with Arivu in which he spoke about the layers nestling in the lyrics of his hit song. What really drew me to it was how Arivu spoke about wrapping elements of a lament (from the musical genre of oppari) and references to a history of caste oppression into a chant that celebrates solidarity and power. That same sensibility runs through the visuals of the music video, which now has more than 129 million views and 3.1 million likes on YouTube.

Director Amith Krishnan has made one of the most stunning music videos I’ve seen in ages for “Enjoy Enjaami”. Not only is it gorgeously shot, it reflects the idealism and richness of the lyrics. With its modern baroque aesthetic — women draped in gleaming fabrics and bejewelled right to the tip of their nails; men decked in gold and glam — the video subtly thumbs its nose at how Dalits and other oppressed, marginalised communities tend to be depicted in mainstream Indian entertainment as impoverished, hopeless victims. At the same time, the fertile dream landscape stands parallel to the rugged real landscape in which people toil, often for very little gain. Despite seeming disparate, “Enjoy Enjaami” shows these worlds are connected — through laughter, dreams, music and dance as a community remembers its past and dreams of a different future.

Bottom line: Come for the politics, stay for the beauty.

I think the lady in the centre is Arivu’s grandmother, whose remembrances are at the heart of the song’s lyrics.

I think the lady in the centre is Arivu’s grandmother, whose remembrances are at the heart of the song’s lyrics.

Deepanjana Pal's Blog

- Deepanjana Pal's profile

- 34 followers