Art thou Vincenzo

In episode 14 of Vincenzo, when our hero needs to get inside the office of the director of Ragusang Gallery to bring down the Korean tower of Babel, art comes to the rescue. The intrepid (and adorable) intelligence agent An Ki-Seok (Im Chul-Soo) finds out that the director keeps a celebrated but rarely-seen work of contemporary art in her office, which she shows only to select visitors. The work is by an American artist named Jackson Martin, costs approximately $90,000 and is titled “Nothing”. All Vincenzo (Song Joong-Ki) needs to do is to pose as a snooty collector and convince the director to show him “Nothing”, and hey presto! The director’s office will be opened up to him.

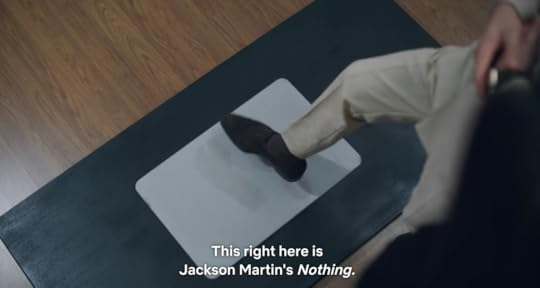

It all goes according to plan — with the added bonus of a much-awaited kiss between Vincenzo and Cha-Young (Jeon Yeo-Bin) — until the couple are in the director’s office and have to a) spot the artwork, and b) be suitably impressed by it. Because this is “Nothing”:

Vincenzo will see Salvatore Garau’s $18,000 “immaterial sculpture” and raise you the $90,000 “Nothing”, thank you very much.

Obviously, “Nothing” is writer Park Jae-Bum’s tongue-in-cheek comment on contemporary art. The director of the gallery explains that the sculpture, which Vincenzo initially mistakes for a doormat, examines “the emptiness of material culture” through the artist’s “sixth sense”. It’s almost as good a line as the one Garau delivered to justify his decision to present (and price) thin air as fine art: “After all, don’t we shape a God we’ve never seen?”

“Nothing” isn’t the only time art and art galleries make an appearance in Vincenzo. The art gallery pops up at three key moments in the show, each time creating a space in which romance can blossom, giving both viewers and characters some relief from the ‘real’ world beyond the gallery. Inside the white box, Vincenzo can set aside violence and instead flirt with attractive women against an artistic backdrop, like when he approaches a woman who agrees to testify against her husband so long as Vincenzo will go on a date with her (more on that later) or the meeting between Cha-Young and Vincenzo right at the end of the show. The implication seems to be that these are relationships that won’t survive outside the cloistered, unreal world of the gallery.

On the other hand, art is very much a part of the real world of Vincenzo. Much like the classical music in the drama’s soundtrack, the classical paintings in the production design offer a subtle commentary to the unfolding events, like footnotes in a text. They are details that are very deliberately included with director Kim Hui-Won making sure we don’t miss them. For example, at one point in the show, Vincenzo and Cha-Young corner an unscrupulous lawyer. When he’s blustering and denying the allegations of bribery against him, this is what the set looks like. Notice the clean and clear windows.

When he’s been exposed and is begging for mercy, this poster miraculously appears on the window behind him.

The idea of using art to signal the mindset of the characters in the foreground shows up again in the last episode, when Vincenzo and Cha-Young meet after a year at where else but a gallery.

The painting doesn’t come into focus at any point, but if you’re a fan of Caravaggio, then you’ll recognise it’s “The Seven Acts of Mercy”, which Caravaggio painted after he killed a man and was forced to flee Rome. The parallel with Vincenzo, who has killed way more than one man and is currently on the run, is obvious. We later learn that Vincenzo’s carrying out a lot of these acts of mercy on his private island, which is supposed to be a refuge for a chosen few. Like Vincenzo the Lover, Vincenzo the Merciful also seems to belong in a bubble, which is perhaps why we see him against the backdrop of “The Seven Acts of Mercy” in a gallery. The utopic island refuge he has built is cut off from the rest of the world. On the island, Vincenzo is the kindly, forgiving patriarch (albeit of an island owned by mafia); elsewhere, he’s the unforgiving devil in the impeccably tailored suit who walks alone and doesn’t hesitate to kill those he finds objectionable.

There are two paintings that occupy the foreground in Vincenzo. The first is a work from the late Middle Ages, which we see in the aforementioned unscrupulous lawyer’s office. When Vincenzo visits the office, he sees the painting and guesses that it’s hiding something.

Later, he breaks in and discovers a safe behind the painting. In that safe are all the bribes that the lawyer has received. In case you were wondering, the painting is “Kiss of Judas” by Giotto di Bondone. Yep, Judas, who sold Christ out for 30 pieces of silver, marks the spot where the sell-out lawyer stashes his cash.

And then there’s “Liberty Leading the People” by Eugène Delacroix, which gets by far the most fun treatment I’ve seen European art get in popular entertainment since René Magritte’s “The Son of Man” in The Thomas Crowne Affair. We first see Delacroix’s painting as part of an exhibition titled Palette of Emotion, where Vincenzo meets the wife of one of Babel’s morally-corrupt senior employees. It’s essentially a seduction scene in which — brace yourself — art criticism works as pick-up lines. Vincenzo’s opening gambit is to stand behind the woman and murmur, “War and art are best observed at a distance” (which we can conclude is a signature move since he repeats it when he meets Cha-Young against the backdrop of “The Seven Acts of Mercy”. His success rate is 100% and as any art critic will confirm, this requires way more suspension of disbelief than anything else in Vincenzo. That includes the pigeon god, Inzaghi. But I digress…).

So there they are, Vincenzo and the woman in a dead-end marriage, staring unblinkingly at a painting of liberty. When she takes a couple of steps towards him, he comes closer, all the while murmuring not sweet nothings, but details about Delacroix’s painting, like the use of colour and the flag that became a symbol of first the French Revolution and then France. It’s enough to make her pulse flutter, but Vincenzo has a final flourish — “She reminds me of you,” he says, indicating Delacroix’s painting of the goddess Liberty.

Next thing we know, the woman agrees to give a testimony in court against her husband provided Vincenzo will go on a date with her. If she’d asked him to come up and see her etchings, it would have been sheer perfection, but “Take me to see an opera” isn’t bad as euphemisms go.

Even better than Vincenzo using Liberty to liberate a woman from her unhappy marriage is the moment in which the ragtag bunch of Geumga Plaza tenants recreate Delacroix’s painting.

This scene is delightfully ridiculous and elegantly choreographed as the it goes from complete chaos to a structured but bonkers ode to “Liberty Leading the People”. Hilarious as the moment is, it’s also earnestly idealistic. The tenants of Geumga Plaza are similar to the people following Liberty in the painting — everyday folk who are either exploited or ignored by the establishment and those in power (and all of them vibrantly alive, unlike the painting in which the living are a minority and most are dead). Initially, the Geumga gang are a loosely-connected group, but in the course of the show, they become a proper collective that is empowered and resilient. They fight for their rights (very literally on more than one occasion), emerge victorious and stand by their principles. The hat-tip to Delacroix is the exact moment when the Geumga gang comes together as a collective.

Of course, they have no idea that they’re recreating a French painting, but that in itself is an ode to the timelessness of art. Almost 200 years after Delacroix painted “Liberty Leading the People” in France, it continues to feel inspiring and relevant to people in Korea.

There’s a sharp contrast between the affection and respect that Vincenzo accords to classical European art and the way the writing of the drama effectively dismisses contemporary art. While even a 14th century painting (“Kiss of Judas”) is shown as pertinent to the present, the present-day works in Ragusang Gallery, like “Nothing”, come across as elaborate, elitist pranks. “Nothing” is almost literally what the title suggests. Not just that, it doesn’t last. The work is easily vandalised and the only one who shows any remorse for “Nothing” being destroyed is the director of Ragusang Gallery.

This attitude is… interesting because modern art is usually treated with respect in K-dramas. A number of shows have artists as heroes or second leads (eg. Her Private Life and Run On). I find the art that we see in these shows to be mostly regrettable, but those in the world of the show are deeply appreciative of modern art as a vocation. The artists in K-dramas are invariably painters — rather than, say, performance artists or video artists, which are generally considered edgier, cooler genres — and through their work, modern art tends to be depicted as something that adds beauty and insight to a difficult world. Vincenzo in contrast shows little respect for contemporary art and artists. It’s adoration is reserved for historic, European art.

There’s something almost surreal about seeing paintings and artists in TV serials. Art is supposed to be highbrow while TV is decidedly lowbrow, but at least in K-drama, the twain do meet. Regardless of what kind of art is privileged, these shows present fictional worlds where creativity is a cherished part of everyday life and art isn’t just an indulgence for the moneyed and the privileged. Through the art that it showcases, dramas like Vincenzo send out the message that the imagination is something to be celebrated. Even if it’s called “Nothing”.

Deepanjana Pal's Blog

- Deepanjana Pal's profile

- 34 followers