Mark Fuller Dillon's Blog

October 15, 2025

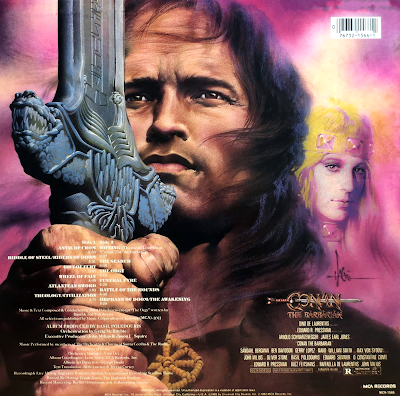

CONAN THE BARBARIAN, 1982.

Click for a better jpeg.

Click for a better jpeg.Now and then, a film not only exceeds my expectations, it leaps beyond them. If a film is older, this impact owes nothing to nostalgia, but shows how definitively the film has remained a living work.

This applies especially to CONAN THE BARBARIAN. I never saw the film in 1982; instead, I bought the MCA record album of the Basil Poledouris score. Despite the lousy sound of that vinyl pressing, despite the often-muddy recording of an under-rehearsed orchestra, the music stood out for me in its mood of melancholy introspection. I fell in love with it, and this love has endured.

Sometimes, good film composers write music not based on the films on screen, but on the films that play in their heads. Jerry Goldsmith did this often: no matter how wretched the film, he was able, time after time, to find something worthwhile in the garbage heap. For all that I knew, Basil Poledouris might have done the same with CONAN THE BARBARIAN, but I would not find out for certain until I had seen the film without interruption, at its full length of 130 minutes, just two or three years ago.

To my happy surprise, the film turned out not only to deserve its musical score, but to reflect it. The music was not glitter on a dull rag, not a pleasing mask on a bland face, but an accurate reflection of what the film showed and implied.

The 1980s brought a surprising number of brutally violent yet humanistic films, films that emphasized action without sacrificing human concerns. I think of THE ROAD WARRIOR, BLADE RUNNER, ALIENS, THE TERMINATOR, ROBOCOP: films of unexpected emotional resonance, "pulp" fantasies that somehow managed to convey something honest about human sorrows and human strengths. CONAN not only fits within this category, it defines the category.

What CONAN emphasizes even more than these other films is the melancholy, the isolation, of heroism, and this element shines out beyond the film's details of spurting blood and brutal deaths.

Much could be said about the technical excellence of this film. Its director, John Milius, might not be Akira Kurosawa, but he shows undeniable skill with the blocking of actors, the staging of action, the emotional and thematic values of lingering moments, the effectiveness of editing. His use of landscapes, of crowds, to support emotions and implications reveals a genuine vision.

In choosing his cast for their physicality, Milius ran the risk of poor performances. To counter this, he puts emphasis on eye gestures, on moments of stillness to convey suffering or sorrow. Even if someone like Sandahl Bergman lacks the voice of an actress, Milius ensures that her face, her movements, overcome this limitation. As a result, her character becomes not only convincing, but heart-breaking. Visual details make all of the difference.

The film is also less about well-rounded people than about the roles they serve. In moments like the introduction of the wizard, of Subotai, of Valeria, a character is not so much encountered by the hero, as recognized. This actually works in the films favour: these characters are not like us; they are mythic patterns, representations, within their own fantasy world.

All of this appears on screen, and is clear to anyone who pays attention, yet the meaning of CONAN, at least at first glance, can seem less clear, if only because the film would rather show its implications than spell them out. Some people have called this film a right-wing power fantasy, yet I doubt this, if only because the film adds layers to its apparent simplicity.

Early in the film, when Conan makes a name for himself as a gladiatorial slave, he is asked by a sponsor, "What is best in life?"

Conan replies, "Crush your enemies, see them driven before you, and to hear the lamentation of the women."

The sponsor approves, yet the film goes on to suggest better things in life. Subotai shows Conan the value of friendship and loyal companionship. Valeria shows him the value of love and a sexual relationship between equals. Osric shows him the value of family, of paternal devotion. And Thulsa Doom, ironically, shows him the value of purpose in life, of the strength and freedom to achieve this purpose.

All of this would suggest a film deeper and more nuanced than a simple power fantasy, and these layers become all the more clear at the film's ending. Unlike STAR WARS, with its final explosion and ceremonial medals, CONAN ends with a hero lost in thought, without purpose. After his defeat of Thulsa Doom, while surrounded and vastly out-numbered by the torch-bearing servants of Doom, Conan raises the broken sword of his father, and then drops it, discards it, as if to say, "Do whatever you like with me. My goal is completed. I'm finished."

Conan's moments of reflection, of isolation; Valeria's loneliness, her need for warmth and for someone who will not simply "pass by in the night;" Osric's realization, "There comes a time when the jewels cease to sparkle, when the gold loses its luster, when the throne room becomes a prison, and all that is left is a father's love for his child," these are not merely details. These are, I suspect, the foundation of what CONAN THE BARBARIAN means as a film.

A film that deals explicitly with violence and action can sometimes be misunderstood as being only about violence and action. Nobody would make this mistake while watching SEVEN SAMURAI, but many have been less willing to see nuance in CONAN THE BARBARIAN. I would urge them to take another look.

September 18, 2025

Neoliberalism, Oligarchy, the New McCarthyism: Can America Survive?

Walt Kelly, POGO, 1953. Click on the image for a better jpeg.

Walt Kelly, POGO, 1953. Click on the image for a better jpeg.America has gone through this before, and survived. But will it survive this time?

The formation of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1938, The National Security Act of 1947, and the spectre of McCarthyism from the late 1940s to the early 1950s, all cast a cold spell on liberty and freedom of speech in the United States. These were terrible times, but certain features of American society allowed the country to endure:

-- A growing middle-class with increasing wealth and political influence, along with increased leisure time for thought, reflection, and civic participation.

-- The suddenly-opened doors of college and university education to people who could not have afforded such things before the introduction of the G.I. Bill (the Servicemen's Readjustment Act) of 1944, along with an explosion of affordable paperbacks that opened up worlds of thought and literature to the working class.

-- A strong civil society, formed of unions, churches, town halls, colleges and universities, fraternal organizations, and active public spaces where people could meet, mingle, and share concerns.

These pillars of democracy and civic participation no longer exist in post-1970s America. Neither Democrats nor Republicans consider such foundations important; what matters in their neoliberal non-society are transactions of the market, by the market, for the market. In such a world-view, merely human concerns are obsolete.

Over the course of decades, America has removed all of the defences that once protected the country from HUAC, from McCarthyism, from the power of oligarchs and demagogues. A crumbling, hollowed-out society must now face a neoliberal cliff, perhaps even fascism, but without organization, without solidarity, and without hope.

Can Americans prevail?

I want them to prevail. But I have my doubts.

September 7, 2025

Poetry Matters, But Why?

Why does it trouble me that poetry no longer seems to matter in our culture? What does poetry do, and why do we need it?

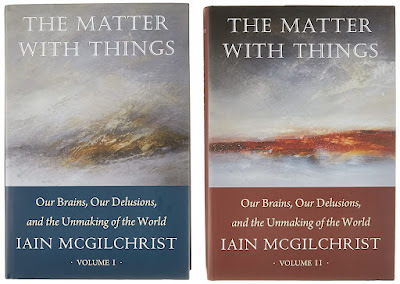

This question nagged at me for years, but recently, my thoughts have been clarified, thanks to a terrifying book by Iain McGilchrist, THE MATTER WITH THINGS. He writes at length about the different forms of attention provided by the two hemispheres of the brain. As human beings, we need both forms, but our societies often prioritize one form of attention above the other, or even pretend that only one form exists.

Click for a better jpeg.

Click for a better jpeg.To summarize badly what is, in McGilchrist's book, a detailed and nuanced argument: the right hemisphere of the brain is attentive to the broad scope of life, to time as flow, to experience as a shifting interaction with a living world. It recognizes that other people are as real as we are, and that they, too, harbour a concealed, subjective experience of life.

In opposition to this, the left hemisphere wields a set of specialized tools: it solves problems by turning living forms into abstractions or mechanisms, by reducing the flow of time to points on a graph, by transforming landscapes into maps. These reductive tools are essential to human survival, but the left hemisphere can lose itself in abstraction: then it mistakes abstract data for reality, living beings for machines, maps for terrain. It mistakes isolated moments of lifeless time as more objective and real than the flowing tangle of human experience.

The right hemisphere is able to integrate the abstract conclusions of the left into a broader, living perspective. The result is a back-and-forth communication between two necessary modes of responding to the world, but sometimes, this communication becomes one-sided. While the right hemisphere accepts a need for the reductive problem-solving tools of the left, the left often disregards the integrations, the reminders and insights, of the right. It assumes that its created abstractions are the real thing, that its reductive tools are the only valid ones for existence.

When societies grow in complexity, when they face more and more technical challenges, they rely more and more on left-hemisphere methods. They teach the methods in schools. They reward the methods with money. They often reach a point where they consider these methods the only "realistic" approach to life, and they dismiss the second thoughts, the warnings, the broad perspectives of the right hemisphere, as unprofitable distractions.

Iain McGilchrist argues that Western society has trapped itself within a cage of reductive left-hemisphere attention, that it disregards or dismisses the troubling yet living perspectives of the right.

In his own words:

"Public discourse in a culture can accentuate some ideas, concepts, beliefs and values at the expense of others. And when this happens, it is not as if these ideas, concepts, beliefs or values are atomistic; they bring with them a largely coherent world-picture, which gradually forms itself in the culture, and over time is expressed in a myriad of ways. I believe our own culture is unbalanced in the degree to which the left hemisphere’s take predominates. And, unfortunately, the left hemisphere is decidedly imperceptive -- and so is unaware there is a problem."

The result is a world of machine systems fit only for machine-people, of algorithms considered more intelligent than human consciousness, of a natural world increasingly exploited and poisoned, of human relationships and political systems rapidly falling apart. It often seems that our entire way of life has been designed to ignore the wider, deeper, empathetic awareness of the right hemisphere.

We still have right hemispheres, but many of us ignore them, or distrust them, or consider them irrelevant to our consumer-capitalist, oligarchic present. The cost of our denial is human misery.

How can we escape from this trap?

For a start, we can, each of us, begin to pay attention to our forsaken right hemispheres; we can begin to communicate with our own selves. One form of communication is complex melodic music; another is poetry.

Poetry and music are akin: both rely on sound, on complex yet regular rhythms, on suggestive and fleeting moods, on things not quite understood yet felt in the bones.

I would suggest that we no longer value poetry because we no longer value the broader, living perspectives of human attention. If we immerse ourselves in poetry, if we begin to appreciate its visceral impact, then we can train ourselves to recognize and to heed the promptings of the right hemisphere.

This argument for utility ignores an important truth: poetry, like music, is beautiful. Poetry, like music, can move us in ways hard to explain yet impossible to disregard. Poetry, like music, cultivates an aesthetic and emotional appreciation of life, and this appreciation can make us more complete, more aware, more human.

Poetry belongs to us in the way that webs belong to spiders, that hives belong to bees and hornets. We create poetry, we read and recite poetry, because we need it. Here in this appalling century, we have been taught to believe that poetry no longer matters, because we have been taught to believe that human lives no longer matter.

Both assumptions are wrong; both can be corrected, if we have the will to confront them.

July 7, 2025

Sometimes, When I Dare Myself To Read Robinson Jeffers

Photo by Edward Weston, 1929. Click for a better jpeg.

Photo by Edward Weston, 1929. Click for a better jpeg.Sometimes, when I dare myself to read Robinson Jeffers, I think, "No no no, what if he's right?" But then I read him again, and think, "No no no, he's right." Either notion appalls me.

Rearmament

by Robinson Jeffers.

These grand and fatal movements toward death: the grandeur of the mass

Makes pity a fool, the tearing pity

For the atoms of the mass, the persons, the victims, makes it seem monstrous

To admire the tragic beauty they build.

It is beautiful as a river flowing or a slowly gathering

Glacier on a high mountain rock-face,

Bound to plow down a forest, or as frost in November,

The gold and flaming death-dance for leaves,

Or a girl in the night of her spent maidenhood, bleeding and kissing.

I would burn my right hand in a slow fire

To change the future... I should do foolishly. The beauty of modern

Man is not in the persons but in the

Disastrous rhythm, the heavy and mobile masses, the dance of the

Dream-led masses down the dark mountain.

-- From

THE SELECTED POETRY OF ROBINSON JEFFERS.

Random House, New York, 1938 (Eighth Printing).

Originally appeared in

SOLSTICE AND OTHER POEMS.

New York: Random House, 1935.

Why Imagine Reality? Reality Is Here.

Imagine a Second World War, in which the Western governments all supported nazi Germany.

On second thought, never mind. Why imagine a state of corruption that exists right now in the daylight?

July 3, 2025

Apologists For Genocide Make the Same Excuses Over and Over Again

"Remember, kids: Israel has the right to defend itself against doctors, nurses, farmers, teachers, firefighters, reporters, the mutilated, the blinded, the crippled, the starved, and of course, children.

"Especially children. Ever and always, children."

Genocide Kills Meaning

Genocide is not only a crime against humanity, it is a crime against meaning, against human purpose. Genocide negates not only our best values, but kills any hope for the discovery and preservation of new values. Like nuclear war, genocide is the ultimate nihilism, and here we are now, dying within our own minds, dying within our Western culture.

May 19, 2025

Trapped In A Neoliberal Hell

"Never think. Never feel. Interact only through financial transactions. Value only the commands of the market." These are the implicit messages of neoliberal consumer capitalism.

Yet human beings think and feel. Human beings require values and relationships that go far beyond the transactions of selling and buying. Human beings need human values. Take these away, and societies fall apart.

When people understand this, governments panic. Implicit messages become explicit, and so does punishment. Speak out against environmental destruction, and you will be ridiculed. Speak out against proxy wars, and you will be cancelled. Speak out against genocide, and you are finished.

Yet still, we think, we feel, we live by empathy. We continue to be human, because the alternative is an openly authoritarian hell on Earth.

Life is hard right now, life will get worse, but somehow, we must hang on to being human. We must persevere, because if we lose, we die.

May 18, 2025

Biden's Cancer Is Not Justice

Click for a better jpeg of this ghoul.

Click for a better jpeg of this ghoul.I would never wish cancer on anyone. Yet I would also never wish genocide on anyone. Genocide Joe, true to his name, is a thug who could have stopped a genocide, but instead, allowed it to happen, allowed it to persist.

Now that Genocide Joe has been diagnosed with cancer, many people have mentioned cosmic "justice." But no, there is no justice in cancer. Justice remains a human concept, a human goal. For Genocide Joe to pay for his crimes against the human species, he would need to face trial and conviction, but our current society rewards genocide while punishing those who speak out against atrocities. For this reason, Genocide Joe will meet the worms in his grave without facing justice.

No one deserves cancer. But Genocide Joe should have paid a social cost for his cruelty. That failure is ours.

May 4, 2025

Collapse

During my lifetime, two global powers have collapsed: the USSR, and now, the USA. The first died peacefully; the second seems determined to drag the rest of us down with it. (If we survive these convulsions, we can watch a third collapse: the European Union.)

I never wanted to see any of this, but here we are.