Simon Fellowes's Blog

September 8, 2025

All Change

FYI I’ve decided to export my writings to Substack. Its system is a heck of a lot easier to use and of course it allows the possibility of monetization (yay!). Not that I have any immediate intentions of doing so. But should the wolves ever show up at the door, it’s always an option.

Anyway, I would hugely appreciate it of all you kind and loyal readers would in future go to this link below to discover my latest ramblings and point of view. Hopefully they will be as entertaining and thought provoking as ever. Thank you.

July 27, 2025

Mainstream

Things change. Bite it. Accept it. Stop moaning. I get it. But still…

When I was growing up, music was something used to define yourself. Your choice in the artist you liked said something about you, something you wanted other people to know.

Quite often, certainly amongst me and my friends, that choice could be obtuse, certainly ‘alternative’. We took great pleasure in discovering someone or something no one else had heard about.

But we also delighted in turning our friends onto that thing. We didn’t always want to keep it all to ourselves. In fact some of the time, we needed to know whether there was something peculiar in liking that thing, whatever it might be. If we could find others who agreed with our point of view, who liked the thing as much as we did, then somehow it made us feel a little less strange, a little less alone.

I’m sure that same behaviour exists today, and you can no doubt trawl through endless Spotify playlists, Instagram stories, TikTok clips, and find any number of artists unknown to most people but who’ve managed to foster a passionate and devoted following.

But the vast majority of people seem to be happier opting for something that is not only mainstream but also wilfully accepts the status quo (especially if sounding like the band of the same name).

Yes, we’re back to the subject of Oasis. But before I’m accused of misanthropic churlishness (let alone envy, jealously, or spite) I have no beef with the band themselves (I’m sure they’re relieved). Nor do I disparage the however-many hundreds of thousands of people enjoying their shows, whether watched from inside the stadiums or on the top of a nearby hill. These are difficult times and anyo ne able to appreciate a few hours of joy isn’t to be knocked for doing so.

It’s just that watching events that in reality seem no different from a football match — beer, bucket hats, and copious swearing — or even a boozed up stroll along the main street of Ayia Napa — feels a long way from what Rock and Roll used to be about.

Rock and Roll was once the domain of people who felt they didn’t fit in, who wanted to rebel from the ‘normal’ way of behaving, who wanted to distinguish themselves from the generation who’d come before.

Elvis was the first example of this, terrorising fundamentalists, pissing off parents, challenging sexual and racial mores. The baton was picked up by The Rolling Stones, not only pissing off parents but pissing against walls, getting mixed up with drugs, satanism, Hells Angels and eventually murder. Bowie came next, playing with the idea of what it meant to be a man, a woman, and anything in between. And finally The Sex Pistols, being furious and filthy, getting beaten up and arrested… one of them dying. That’s what Rock and Roll used to be about. That’s what people believed it to be about.

No longer it seems. The biggest band in Britain offers little more than a mass sing-along. There’s nothing wrong with that. The TV variety show ‘The Good Old Days’ once offered the same.

But that it should be seen as a paragon of ‘attitude’, of ‘rebellion’, is absurd. In reality, the experience is as comfortable as a pair of Bonehead’s moccasins.

One shouldn’t be surprised. It’s been a long time coming. The assimilation of the concept of rebellion of teenage revolution, into something com-modifiable has been an ongoing process for the last 40 years. Ever since corporations recognised the potential of Pop Stars, whether to sell newspapers, perfume, or fizzy drinks, Rock music’s mantle as the voice of dissent has evaporated. Heavy Metal has been neutered and even Hip-Hop is now a self-parody, the few artists of worth still making social statements — NAS, Kendrick Lamar — dwarfed by those happy to rhyme about sex and money.

Ultimately none of this is important. Music is simply a part of the industrial entertainment complex to be filed alongside festivals, city breaks, the Marvel franchise, gymnasiums, the Premier League, and wellness retreats. We shouldn’t expect to find anything intelligent or interesting in any of these places.

Instead music has become an opportunity to turn off the brain, to spend a few hours thinking only about yourself, to become lost in an ‘experience’, albeit one constantly archived on your phone. It’s an opportunity to be you, a version unencumbered by life’s pressures and demands. In doing so, one’s life is reduced to moments, ‘unforgettable’ moments to remind us we’re living, that we’re still alive. Whether silhouetted against a sunset in Goa, or grinning with pals against a vista of exploding fireworks, or even a jumbo-sized video screen, it’s important we’re seen to be part of whatever’s going on.

We don’t want to feel disconnected.

We don’t want to be outsiders.

It’s the one thing that nowadays we’re most afraid of.

Yet once upon a time this is what Rock and Roll used to be about, what it used to represent — a celebration of alienation, of being different, of feeling disconnected.

No more…

Now it’s an arm around the shoulder, a drunken gurn into the lens, an instant upload onto social media.

Like I said, things change, accept it and stop moaning.

But my, what a long and complicated journey we’ve been on.

27/08/2025

June 17, 2025

BEEN THERE THEN

Two weeks from now, the British band Oasis will begin their long anticipated world tour. The shows have been fifteen years in the making, the group, fronted by brothers Liam and Noel Gallagher, having acrimoniously split in 2009. A generation of nearly 40-somethings, having paid extortionate prices to attend, are hoping to be entertained by a gaggle of jowly-looking individuals approaching their 60s. The catalogue of hits will be played, the stadiums filled with dewey-eyed, bucket-hat-wearing lads and ladettes, bawling out the words in a shared communion of remembrance, harking back to the times when they first heard these anthems, these Beatles pastiches, these Slade-like stomp-alongs, a time when the audience actually knew how to feel.

I saw the original Oasis myself, several times it had to be said. The first at some taping of a minor television show. The second on set for the making of their video for ‘Roll With It’ (I was coincidentally employed as a director at the production company who made the video), at Earls Court shortly after the release of the band’s debut album, and again at Maine Road, by which point Oasis had been embraced by the hordes.

For a brief moment the band had represented something kinetic, a blast of the familiar but delivered with enough energy, attitude, and volume to make it feel worthwhile. Detractors bemoaned the luddite nature of their approach, both the music and their unabashed show of ignorance (they volubly eschewed the reading of books). The band was also mildly homophobic, once declaring they hoped a rival of theirs caught AIDS. It was undoubtably an ugly package, but it did represent a strain of British society that exists and in truth has always existed. What annoyed the band’s critics more was that this grisly behaviour was celebrated, that a yobbish, wilfully un-inquisitive state of mind was seen as more honest, more relatable, and somehow more authentic than the foppish posing of their contemporaries.

There was no doubt it reflected a swathe of British society scared of the unknown and things they didn’t comprehend. Such existential terror continues today, people looking for anyone but themselves to blame for their ills, for their inability to understand what the fuck is going on. Whether that target is immigrants, queers, transsexuals, or people who support a different political point of view, there’s always a target, a receptacle for your bitterness, resentment, and hate.

Not that all Oasis fans should be tarred with this brush. But like Brexit, you didn’t have to be a racist to vote for it, but every single racist most definitely did.

More concerning however in these febrile and complicated times is the rush to nostalgia; an almost pathological need to return to a better and more understandable time where people had a clearer sense of who they were and where they fitted in with society. Current generations have been rendered apart, the older no longer understanding what motivates the young, the young despising the old for their privilege — a long term career, an affordable home. Music, especially here in the UK, has reflected this dynamic. For decades, certainly during my growing years, most people were cognisant of the current ‘number one’, the song that had made it to the top of the charts. Whether a novelty song or something of weight, the fact that people were aware of the song’s identity in some small way brought the country together. Pop groups would appear on a variety of TV shows, and rather than being a mystery to viewers, were recognised, admittedly sometimes only for being ‘that twat in a dress’, or the band with ‘that mad prick who looks off his head’.

Still, there existed a collective sensibility at play. A teenager could take pleasure explaining to her gran that, ‘No, David Bowie is definitely into girls.’ Pop music acted like a thread, the playlists selected by Radio One drawing people together. Everyone knew the tunes, some people knew the words. Music defined the way they were feeling, how they dressed, how they danced, how they presented themselves.

And of course, as we know, all that has changed. Music has disintegrated into a myriad of silos, few of them interacting, leaving everyone to twist in their own self-defined space. The only time these tribes intersect is at the big music festivals where it’s simply uneconomic to focus on only one type of music. But for the rest of the year, everyone retreats into their own carefully curated worlds. There’s as much likelihood of an Alex Warren fan knowing a song by The 1975 as there is a Doechii lover singing along to Wolf Alice. Yet all are top ten artists. Maybe it has always been this way to a degree, but it now feels more acute. Nor would it be a problem if it wasn’t the fact that a need to participate in something ‘unifying’, something bigger than ourselves, a way of being maybe, an attitude that transcends those in our immediate vicinity but instead hovers in the air… something that feels like change… clearly nags away in the back of people’s minds.

So where to go to find this sense of community? Too often it seems in all the wrong places. Extremists on both sides of the political spectrum retreat into their chambers of neanderthal bile. The progressives meanwhile stand on the sidelines and howl, impotent, navel-gazing, their hands nowhere near the levers of power.

The rest are left with Oasis… or Springsteen, or Dylan, or McCartney, the latter trio willing troubadours long past their prime. Listening to all three sing is now a painful experience, the mind flashing back to how they use to sound, how they’re supposed to sound. I expect Liam Gallagher will deliver the same, a feeble rasp and an avoidance of any note that’s challenging. If his performance a few months back at the Joshua versus Dubois heavyweight fight can be seen as a marker, it’ll be a miracle if he manages even that.

The truth of the matter is you can never go back. How hard will the members of the audience, having spunked up a couple of hundred quid on a ticket, plus travel costs, plus the exorbitant beers, try to convince themselves that what they’re experiencing is worth the outlay. How hard will it be to avoid the reality that they’re no longer even a replica of who they once were and nor is the world around them. As they exhaustedly trudge their way back to the station, wearing their souvenir T-shirts and reading their £40 programmes, will they feel consoled by the fact ‘they were there’, and that for a few hours they could pretend to themselves that the confusing universe they were forced to inhabit had pressed pause.

© Simon Fellowes 16/06/2025

May 27, 2025

The Morning After

Now that it’s all over it feels as if it has followed a predictable story : Liverpool’s moment of glory tainted by tragedy. This is what the city, the club and its supporters have grown used to. You can’t have it all, no matter how hard you’ve worked or what you might have come to expect.

In some ways it seems reflective of football as a whole. No matter how large the spectacle, however extreme the emotions, there is still something missing, something rotten, or at least ‘not quite right’, at its heart.

As a long time Liverpool FC supporter, I’m delighted the team has won the Premier League again and of course it was hugely satisfying they were able to do so in front of their fans. But with four games left to play before the end of the season, it resulted in a surprisingly damp squib of an affair, the players — psychologically at least — done and dusted or, as the saying goes, ‘already at the beach’.

Matters quickly turned to the season coming up next, which players would leave and who would come in. The internet has allowed a world of speculation, multiple websites dedicated to rumour-mongering, journalists building their reputation on obtaining the inside track. It makes for a fevered and exhausting atmosphere, especially as 90% of the claims made usually turn out to be false.

But such is the rapaciousness of the modern game, no one is allowed to sit still for a second. The football ‘business’ demands a non-stop narrative, something to fill the airwaves, whether on TV, radio or online.

If a football player or manager isn’t at the heart of the speculation, then a media figure will do, the will-he won’t-he departure of the BBC’s Gary Lineker enough to fill newspaper columns for weeks.

Such are the number of television channels geared towards football, it is now possible to watch it being played somewhere around the world every day (and night) of the week. And just because most of the domestic seasons have finished, don’t imagine for a second the caravan has stopped moving. Even without a summer schedule filled with a UEFA Championship or a World Cup, there is now the spurious FIFA Club World Cup competition starting in a couple of weeks. And if your team hasn’t been selected to play in that competition, don’t worry, the pre-season friendlies will be soon underway, Manchester United already having flown to Kuala Lumpur for their first match on the 28th May, three days after the regular season ended.

What to make of all this? The greed that killed the golden goose? Wembley stadium was notably empty of Manchester City fans at the FA Cup semi-final so exhausted were they with both the effort and cost of travelling to London two or three times a year. Such are the perils of success.

And though more than a million dedicated and ecstatic Liverpool supporters filled the streets of their city to pay homage and say thanks to the squad of brilliant players who won the trophy they so desired, the day will now sadly be more remembered for the monstrous act of a frustrated maniac stuck behind the wheel of a car driving down a street it had no business being anywhere near.

Such is the reality of football these days. You hope for so much but it only takes one moment to ruin it all.

Lessons, as they say, will be learnt. But such is the emotional irrationality of both the supporters and the men who own the clubs, it seems almost inevitable more mistakes will be made. Hopefully none that result in injuries to innocent people, but still, damage to the game will be dealt in a similar vein of pigheaded ignorance and selfishness.

27/05/2025

January 23, 2025

LEARNING FROM HISTORY

And we’re back.

Apologies to regular readers for the absence. Last year was spent working on a couple of longer-form writing projects — two novels to be precise — so the desire to commit time to a blog receded. And maybe there simply wasn’t too much to inspire the imagination. Post Covid, things fell into something of a rut. Of course stuff happened, but it all felt pretty much more of the same — the same angst, the same turbulence, the same bullshit, the same horror — it was hard to feel energised by any of it. What energy I did feel, I poured into the books I was writing.

One of them tells a tale of a former 80s Pop Star (write what you know etc) now living as a recluse and feasting on nothing but memories. His life is disturbed when a young woman finds her late mother’s teenage diary in which an entry details an abusive incident between the teenager and the former pop star. The young woman then takes it upon herself to find the reclusive the pop star and determine whether what her mother wrote happened.

The second book concerns an author (write what you know etc) who is finding it impossible to come up with anything to write such is the tsunami of information, opinions, and news items, bombarding him every day. Hell, we’ve all been there. At the instigation of a friend, in the hope for inspiration, the writer checks back through some old film screenplays he wrote when he worked in the film business. He discovers one he’d completely forgotten. (This too happened to me such is the amount of verbiage I’ve churned out over the years). Reading back through the script stirs up long-buried memories and the writer sets out to find out what caused him to repress them. It’s an Almodovar-type of story (at least I like think so) set in the present day and the early 1960s.

Writing both novels allowed me to process my relationship with the current state of the world. It’s something all artists do, at least all the ones I like. I was struck when writing both books how I had to go back in time in order do this. It forced me to wonder if this was simply a product of growing old, and that without even realising it we start to stake stock, try to make sense of the shape of our lives and how we’ve arrived where we are. Or maybe it’s simply down to the fact that we’re more active when young, making more of an effort to ‘find out about ourselves’, going to great lengths and travelling huge distances to do so.

Once we’ve arrived at some sort of a destination, or at least a place that feels semi-satisfactory, the need to put ourselves about becomes less of an urge. What’s more, over time we find ourselves repeating ourselves, ending up in situations too reminiscent of something already experienced. Why keep doing the same old thing and learning nothing? It feels a redundant way to be.

Still, we have to keep living, we have to feel engaged, or what else is there? A sense of dwindling obsolescence, of disengagement and boredom?

This need to stay connected with and motivated by the world feels extremely acute at the moment. The political change in America and the excessive craziness it brings, of course can feel overwhelming. A lot of people I’m speaking to have decided to ‘switch off’, to tune everything out for the next four years (as if in truth that’ll be possible). Certainly no one wants to be burdened by the psychic weight such destabilisation evokes.

But even if one did want to behave like a mini-version of Rumpelstiltskin and metaphorically go to sleep ‘until it’s all over’ (it’ll never be truly over) there will still be the aftermath to deal with. And stumbling out of the cave oblivious to what brought the world to whatever state it finds itself in, is hardly going to equip anyone with the knowledge and wisdom needed to fix things.

In an attempt to learn from past experience, from history, I recently read Sebastian Haffner’s memoir ‘Defying Hitler’. I was led to it by the writer Emmanuel Carrère who, in his latest book V13 (an examination of the Bataclan attacks of 2015), stated that Haffner’s book was one of the best examples of explaining how a society sleepwalks into disaster. Having read the book, I agree.

Because what shocked me most when reading about the incremental changes Hitler and his cohorts imposed on the German people, was the manner in which people managed to explain them away, how they dealt with them.

As the bar was continuously raised, the behaviour of Hitler’s men becoming increasingly brutal, the German people tied themselves in knots trying to rationalise what was happening.

This behaviour of course you expect from politicians, always looking to hold onto power. You also expect it from industrialists and businessmen, changing with the weather, only concerned with protecting their own interests and those of their shareholders.

But what took me aback were the people like myself and my friends, what I suppose can be described as the liberal intelligentsia (although that does imply something a lot more high-brow than we are). Nevertheless, the way such people made sense of Hitler was by dismissing him as a blowhard, a madman, an accident waiting to happen. They simply couldn’t believe he’d be able to hold onto power for long, that he was so crazy and inept it was inevitable his project would fall apart.

And it did of course, after fifteen years, after millions were killed and havoc wreaked upon major cities all over Europe.

So it does make me wonder how smart does it pay to be? You may think you have an understanding of the lunacy taking place, but that doesn’t mean simply by writing and talking about it you can stop it.

What it means going forward I don’t as yet know. But it’s on my mind. And I can feel the clock ticking.

Or maybe it’ll just mean yet another novel. Will it be enough? Is it the best one can do? Watch this space I guess.

© Simon Fellowes 23/1/25

October 2, 2023

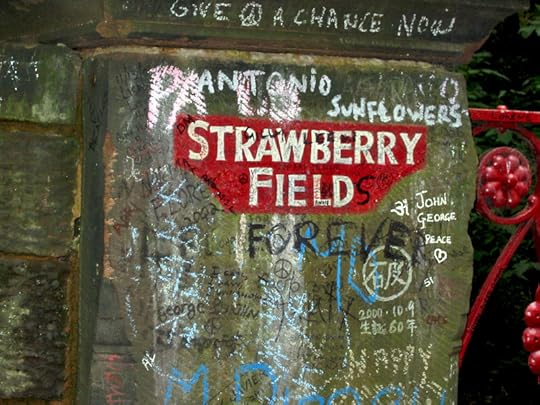

Nothing Is Real

I’m reading D.H. Lawrence’s ‘Sons And Lovers’ for the first time. I know that it might seem surprising, but it’s amazing how many of the classics can slip through the net. There’s a large enough canon to plough through, so I suppose it’s inevitable many get missed along the way (and no doubt will continue to do so).

In reading the book, I’ve been struck by the brutality of the life of the father character, Walter Morel, especially regarding his job as a miner in a Nottinghamshire pit. It shouldn’t have come as a surprise. We have long been aware of the misery and hardship connected to such work. But what registered more powerfully was the reminder of how much this brutalised men, and how, in turn, thanks to alcohol (a desperate attempt at self-medication), they regularly took out their anger, desperation, and frustration, on those around them, particularly their women.

It was one of the worst impacts of an industrialised society, where men in huge numbers were co-opted in the service of machines. A minority of individuals became fantastically rich off these labours, while many might say the advantages industrialisation brought — heat, light, and travel — immeasurably improved people’s lives. But at a huge cost to humanity, the long term repercussions we are only recognising now as the planet heats up to unsustainable levels.

Still, a fascination with technology continues apace. If anything it’s faster than ever. Each week some announcement is made regarding the latest advancements in automation or AI. Our brains race to assimilate these facts, trying not only to understand the potential uses and practicalities of such wonders, but also the long-term affects. But they are hard to predict, caught up as we are in a fog of ignorance, conspiracy, and paranoia.

All we have to go on is our actual experience of technology and the advantages or disadvantages it brings. That can be seen on a macro level — the various climate disasters now taking place — to the micro — the myriad of irritations that unnerve our daily lives.

From the tyranny of email — a tool that was supposed to make life quicker and easier but instead extends our working hours — to Social Media, a method of communication that has only magnified our feelings of insecurity and mistrust.

The pernicious impact of technology has never been felt more keenly as it was last Saturday afternoon by Liverpool football fans who watched as their team were denied a legitimate goal by a ‘significant human error’ on the part of VAR referees who screwed up the online technology. Two red card decisions were also debatable. None of this would have mattered had Liverpool won the game (unlikely once the team had been reduced to nine players), but with the margins for winning the League so fine, and the millions at stake between fifth and fourth place, such errors can have a huge affect. Worse, they sap energy from the game. If the supporters, already paying inflated prices to attend, are no longer able to trust the judgements they’ve been assured are infallible thanks to VAR, it’s hard to maintain trust. If the evidence of what you are seeing can be challenged or ignored, why care about anything at all?

This Orwellian world where onside is offside, where more time is less time, where connection is loneliness, engenders a sense of destabilisation in us all.

Bad actors take advantage of this, whether it be Putin spouting his nationalist poison, shutting down all forms of dissent, or Elon Musk allowing Twitter (X) to be invaded in the name of free speech by an army of cranks, propagandists, and liars. Conversation becomes addled by a flood of disinformation, the effort required to distinguish fact from fantasy too exhausting for people. This allows he who shouts loudest and longest to profit — cf. Donald Trump.

Even within the petty politics of the UK, such methods of deception are now being rolled out in readiness for the next General Election. The PM Rishi Sunak decries 15-minute cities and the supposedly harmful affects they’ll have on personal freedoms. Having narrowly held onto Uxbridge and Hillingdon in a recent by-election after stoking unfounded fears about the ULEZ extension, the Govt now sees this world of dis-information as a route to success. To be frank, after thirteen years in power, it’s all they’ve got left.

While all this continues, Chat GPT and Generative AI make further leaps and bounds, eradicating a multitude of tasks once accomplished by dedicated workers. In response to this job eradication, we shrug, unable to understand how we might stop it, believing that if we don’t embrace such technological advances, we’ll be handing the future to people who will.

Perhaps inbuilt into this mechanical tsunami are the roots of its own destruction. Maybe those who adopt it without sufficient consideration will be the first to lose. The revolution will commence amongst societies who have most cruelly disregarded the humanity of their citizens.

Like the men of the early twentieth century, enslaved by Industrialisation and unquestioned promises of progress, a generation of people will be left to rue decisions made, watching the life they knew and understood rapidly dissolve around them.

As of today, it already feels as if something similar is happening on The Kop.

1/10/2023

September 17, 2023

Off Brand

Reading the headlines this morning — awash with the exposé of alleged rapist and all round scum-bag Russell Brand — I naturally find myself asking ‘Is anyone surprised?’ The Channel 4 documentary and corresponding Sunday Times piece that revealed the allegations, co-opted the title of Dan Davies’ forensic biography of serial paedophile Jimmy Savile, ‘In Plain Sight’. And it seems as if here is another case of a self-obsessed pervert running amok, aided and abetted by willing promoters within the UK Media all keen to cash-in on his shock-jock persona. But it got me thinking. What was it about that period in our history when such characters were so feted, and why?

The noughties feel a nebulous time, most remembered for the events of 9/11, a furious blast that rudely interrupted the millennium, confirming, as if it needed to be confirmed, that things were going to be a lot more complicated than we thought, and that the bright shiny future was probably going to have to be put on hold while we dealt with the errors of our immediate past.

The 90s in contrast, is a period we’re happy to be nostalgic about. Those who were teenagers during that time are now commissioners at broadcast companies, or executive producers. The 90s is the rose-tinted era they remember most fondly, and therefore the one with which we are currently being bombarded. This past summer saw a slew of BritPop bands reforming and taking to the stage, playing to thousands of dewey-eyed 40-somethings, bucket hats retrieved from the back of the wardrobe, all the better for protecting the newly bald pate from the rays of the sun.

The noughties (in the UK at least) could be seen to have ended with the London Olympics in 2012, the apogee of self-congratulation, a massive slap on the back for integration, promising a successful future on the world stage. It turned out a myth of course. The naysayers and creeps had always been waiting, if not lurking, in the background, ready to tear the edifice apart, the version of Britain they hated to recognise.

So where did the likes of Brand fit into this maelstrom? There was always a pretence of self-awareness about him. You saw it in his stage act. ‘Mate, I can say the most godawful things, but as long as I keep winking – in a post-modern way – we can all nudge each other, indulge in the degradation, convincing ourselves that it’s only a laugh.’

But of course we know now that it actually wasn’t. And some — in fact, quite a few — knew at the time but decided to keep schtum, the cash cow too productive, too much of a sure bet.

We were all in on the joke… weren’t we? We were savvy, alert. The laddishness of the 90s had primed us into a state of constant distrust, disbelieving anything served up. It was all meaningless bollocks, Mandelson’s spin, the art of the con, advertising wank. We were knowing, at least that’s what we kidded ourselves. Nothing meant anything. Amorality was where it was at. The pornification of society was just one of those things. Ease up, relax, everyone’s doing it — what’s your fucking problem?

And of course some of us were strong enough to take it in our stride, those of us who felt convinced none of it was having an effect — not on us anyway — even if we didn’t realise it, like one of those programmes on your computer that whirrs away in the background, refreshing itself while you obliviously work on something else.

But there were many, too many, on whom it did have an effect, either directly, in the case of Brand’s tragic victims, or indirectly, the legions of girls (and boys) who now see themselves merely as a commodity, an image to be filtered, sculpted, implanted, or hacked to bits.

At first this was called empowerment, a taking back control of your identity, of your individuality, casting off the shackles of a puritan society that determined what you should or shouldn’t do, how you should be.

The noughties also saw the rise of reality TV — regular people becoming national stars overnight. Talent shows sold the idea that anyone could be plucked from obscurity and propelled onto the world stage. Because, after all, if you looked close enough, what was the difference between the Pop stars of old and people like you and me? Quite alot in truth, but that would only be revealed in time, and was certainly of no interest to the executives controlling the shows who were all in favour of democratising fame as long as the great British public kept voting on their phones at 50p a time.

But the curtain had been parted to reveal the truth (at least that was the suggestion). Brand and those who followed in his wake, most notably Ricky Gervais, built a profile on mocking the status quo, on making it clear to their audience they ‘knew how things worked’, that they like us, were in on the scam.

It’s no great surprise both men have continued in this direction, Brand more radically, setting himself up as some kind of Tru-fact online guru, eschewing MSM (mainstream media to you and me) while spouting a number of tenuous theories guaranteed to delight an audience (and it’s a vast number – at the last count he had 11.2 million followers on X (formerly Twitter) Elon Musk being one of them) desperate to believe that they’re different from everyone else, superior even, possessing the inside track on the imagined puppeteers pulling the strings. Gervais too presents himself as a pontificator on big themes, his stand-up shows going under the names: Politics, Fame, Science — and if those weren’t large enough — Humanity. You’d like to think he was being ironic, but he isn’t.

Brand has also played with the image he knows people have of him, his concert shows titled: Scandalous, Messiah Complex, Doing Life.

These guys aren’t ignorant. In fact more than anything, their consciously oblique stance celebrates the cynical philosophy of the 90s that informed both their identities and their work.

Gervais however plays with this cynicism, showing himself at heart to be a sentimentalist, evidenced by the ending of all his television series where everything works out in a metaphorical group hug.

But in Brand’s case, like Savile, like all psychopaths, such soppy endings don’t appeal. The pleasure comes from pushing yourself to the edge, to break the moral code of which you’re so cognisant. For only by transgressing the rules you feel inhibiting you — inhibiting society — do you truly feel in control.

It’s a dance with the devil, but in the end you always get caught.

As Brand himself says in ending his video rebuttal of the allegations made against him this week:

“… I want you to stay close, stay awake but more importantly than any of that, if you can, stay free.”

Freedom for himself, but never for his victims.

17/9/2023

July 10, 2023

Nostalgia

It’s the summer concert season when London becomes host to an extraordinary number of major recording artists performing on stages in and around the capital. From Hyde Park, to Wembley, Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, The Emirates, Twickenham, Finsbury Park, Gunnersbury Park, Brockwell Park, Victoria Park, The 02, Alexandra Palace, Kew Gardens, Somerset House, Crystal Palace, there doesn’t seem to be a square inch of space where some enormous PA hasn’t been installed, along with the attendant merchandise stalls, burger vans, mobile phone recharging units, and portaloos.

Depeche Mode, Arctic Monkeys, Beyoncé, The Red Hot Chilli Peppers, Harry Styles, Def Leppard & Motley Crue, Blur, The Weeknd, Pulp, 50 Cent, The Who, Iron Maiden, Kiss, Peter Gabriel, Wu Tang Clan, Roger Waters, Duran Duran, Fat Boy Slim, The Human League, Iggy Pop, Blondie, Primal Scream, Noel Gallagher, Pink, Guns ’n Roses, Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, Take That, Lana Del Rey, and Black Pink, have all blown into town during the last eight weeks to perform. And that’s just the more notable headliners.

Many of the ticket prices have been well north of £150, yet thousands of punters have been willing to pay. Despite the sneering comments of some, the gigs have been well-attended, most of them sold out. There is clearly an appetite for an ‘experience’, to be part of whatever is going on. The hangover of being locked away during the Covid crisis of 2020-21 is only now being shucked off, the public eager to make the most of their freedom. No matter the cost of living crisis, a ‘live today, pay tomorrow’ attitude is at hand. But it’s combined with something more.

Beyond the need for a sense of the communal, to be part of something shared that’s happening right now, is also the nagging feeling that when it comes to some of the artists — both the old and middle-aged — this might be the last time to see them. Certainly it might be the last time when the artist in question is able to put on a performance of worth, or at least one that captures — if only fleetingly — their energy of old. Close your eyes and you might possibly find yourself transported back to that gig at The Rainbow, The Hammersmith Odeon, The Astoria, The Roundhouse before its makeover.

An exercise in nostalgia is in full effect, one full of joy and happy memories. And that’s no bad thing, except that it’s finite. There are only so many times you can dig out such memories, activate the same poignant recognition of what the songs meant to you the first time around.

Blur is a perfect example. They performed their first reunion gig in 2009. It was an excellent show, a pleasure to celebrate hearing the songs of the last ten years once again. The band reformed again in 2012. I can’t remember why — money perhaps, or maybe because the the Hyde Park concerts had been received so well. They then played a series of shows in 2015. This summer — some 8 years later — the group have reformed once more, playing two nights at Wembley and various other gigs around the world. Yet they have released only one new album since their heyday, The Magic Whip, (to no great acclaim), though are about to release a new set of songs in the coming weeks. But most of their set-list is pulled from tracks released between the years 1991 and 2003, allowing a generation of 40 and 50 years olds to relive their youth; the sun-blanched days of Britpop, Euro 96, and holidays in Greece. Kids become parents, parents become grandparents.

The collection of concerts currently taking place in London reflect this generational separation. Pop music, once essentially the persevere of the young, has now become a signifier of where you are in life and the soundtrack that shaped your identity. There is some bleed-through, but watching the crowd arriving for Bruce Springsteen last Saturday night, it was noticeable that most of the 20-somethings were the kids collecting rubbish or working the gates. No doubt the demographic make-up for Black Pink was skewed in the other direction, the same youngsters however still doing the lousiest, mind-numbing, and lowest-paid jobs.

What this means going forward is anyone’s guess. How much longer will people turn up to see the icons of Rock and Pop trawl through their repertoire, one that rarely changes from one tour to the next. Will people need to see The Rolling Stones one more time? Or McCartney for that matter? And when such ‘legends’ are gone, who will replace them? Will the likes of Blur and The Red Hot Chilli Peppers continue to draw a similarly loyal crowd.

Next year, all the talk is of Taylor Swift and her five nights booked at Wembley. There’s also of course the perennial debate about a potential Oasis reunion and how much the Gallagher brothers will need to be paid for it to happen. But scanning the landscape it’s hard to see what might keep audiences coming back year after year and in such numbers. The familiarity of the experience is bound to have a diminishing effect.

Or maybe not, each generation behaving like the one that’s come before, looking to enjoy an evening of reminiscing and a good old-fashioned sing-along.

Whether this results in interesting music or pushes the dial of creativity on however, remains questionable. The live music experience, certainly when it comes to outdoor events, has transmogrified into something very different from the intense and intimate, sometimes spellbinding, shows that occur in theatres or clubs. But maybe that isn’t so important to people anymore. To be present at such moments one has to show commitment, to pay attention, to turn up early, before a band has found a mass audience. There are too many distractions, demands on most people’s time to expect such thing. Far better to wait until a band has proven themselves, established a body of work you can trust. That’s when it make sense to shell out the money, guaranteed of a good time, a handful of songs you know, and an extensive food and drink menu to keep you going.

9/7/2003

September 11, 2022

The Establishment

When I was a teenager it was cool to be considered anti-Establishment. Perhaps it’s cool for all teenagers to feel that way, even the current Tory prime minister who, as a young Liberal Democrat, proposed abolishing the monarchy altogether. But times change. People change.

I grew up during the decade of Punk when a healthy disregard for all things authoritarian was a given. More than anyone else, the Queen symbolised a notion of order. It was therefore only right that she should be the most obvious receptacle for our irreverent displeasure. There was nothing truly revolutionary or violent in our position, despite the tabloid papers attempt to paint it that way. It was more cheeky than cruel — disrespectful yes, but with a sense of humour. ‘We love our Queen… ‘ Rotten sang after all, ‘And God saves.’

My generation of self-proclaimed reprobates used our mischievous skills (learnt at the altar of McClaren, Foucault, and Guy Debord) to disrupt the status quo, or at least try to mess with it. We became entrepreneurs, self-motivated egomaniacs doing what we could to de-stabilise the system while fleecing it for as much money as we could.

We may have had dreams of something significant, but most of us so-called creatives ended up working as advertisers, marketeers, brand consultants, television programmers, journalists. We were salesmen — a generation of Willy Lomans — no more and no less.

New Labour was the apogee of our influence, a rebranded political party that for a decade managed to convince the country better times lay ahead. That was until forces beyond their control — 9/11 and the financial crash of 2008 — brought reality screaming into view, revealing the limitations of those bedazzled by a belief in their own infallibility.

Until then we had been happily benefiting from the largesse of the Establishment and its associated corporations, hoovering up their investment, their sponsorships, their praise. We had welcomed their support, allowing ourselves to be seen not only in their company but under their logos and banners. In our minds it wasn’t selling out, it was cashing in. Or so we told ourselves. They were the new patrons, the new Popes. It was how the smartest of us survived.

Some lucky few made good sized fortunes from the arrangement, media whizz-kids selling their independent companies to the highest bidder. The comedians at Talkback, Bob Geldof, Tony Eliot at Time Out learnt from their forebears — hippy entrepreneurs like Richard Branson and Chrysalis’ Chris Wright — selling up when their stock was at their highest. It was good times… for some.

Nowadays however, such a renegade approach seems almost mystical, built on a world of cocksure innocence, something now subsumed by the boot of the conglomerates, the masters of the universe, the Ayn Rand-inspired super-egos, the likes of Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, and Jeff Bezos. Positioning themselves as edgy outsiders, they have become the rulers of all, collecting every data point of our lives, before selling it on or using it for their own self-advancing purposes. We are mere blips, binary numbers on an endless scroll.

The death of the Queen allows us to take a step back from this debilitating reality. It’s a reflective time. We not only take stock of what the Queen meant or at least signified to our lives, we also, by proxy, examine ourselves, our values, what feels important. For those of us who have suffered a comparable loss, hundreds of thousands during Covid, the situation feels more acute, mothers, grandmothers, fathers and grandfathers, and in too many cases, children, all gone. The resultant emotions therefore aren’t hard to access.

But beyond the emotional response, there is also an acknowledgement of the Queen’s role in our lives, the meaning of the monarchy. For the majority of people, it seems, or at least we are led to believe, it is something with which we are not only satisfied but also need. It establishes a sense of order, of uniformity, of continuity, of stability. Such is the febrile nature of our times, the existential threats permanent, the sense of atomisation profound, the losing of a symbol so deeply embedded within our framework gives us permission to come together, to find common ground. It is how the period of mourning is designed, a decision made by those at the top of society that this is the narrative we should all believe in, the one to be most firmly embraced. If they are correct in their assumption, and that this is indeed the way everyone feels, events can proceed unchallenged. Should they however measure it wrong, as the Royal family did after the death of Diana, rumblings begin, a groundswell of angry public opinion, the first murmurings of revolt.

But for the time being, a collective position has been taken, an understanding that this is the way people feel, and therefore is the way everyone should behave. The BBC is summarily shackled, playing its role as the nation’s broadcaster (an opportunity to ingratiate itself with its detractors thus boosting its chances of retaining its charter) faithfully trotting out the establishment line. Anyone foolish to stick their head above the parapet and question if not mock events — see the footballer Trevor Sinclair and the comedian Kevin Bridges for examples — is swiftly despatched to a metaphorical tower. Meanwhile, the bastions of the ruling classes rise up, the clerics, the military, the politicians (past enmities forgotten), the lords, gathering as one. Major, Blair, Brown, May, a rehabilitated Cameron and Johnson, line up in black to pay their respects in a series of carefully crafted speeches.

Out on the streets, the great unwashed, speak of rainbows, of symbolic clouds, of the reunion of the Fab Four, and other such nonsenses. They enthusiastically compare the Queen, a woman they might, at most, have encountered for seconds, to their own mother or grandmother. It’s a collective madness, delusional, and reminiscent of North Korea. But the people want it, they need it, these confected moments of magic. Like simple folk staring at the rise and fall of the sun, they long to find meaning.

Though mercifully lacking the hysteria that surrounded the death of Diana, the loss of the Queen still allows performative acts. The age of the selfie, unlike in 1997, is now organically embedded, offering greater opportunities. The cellophane wrapped flowers are still in abundance, the cloying notes pinned to stuffed toys tied lovingly onto railings.

When all this detritus of lachrymosity is cleared away what will be left is Charles, the new king. A forgiven adulterer, he is now the nation’s representative, its standard bearer, its beacon. He rules over a nation greatly diminished since the accession of his mother. Post Brexit it is now an entity splitting at the seams, the Scottish nationalists and the Irish republicans both agitating to pull away. Has he the nous, the power, the personality to keep this island together? Time will tell. But fearing the possibility, one feels the Establishment is taking this opportunity of transference of regal power to bolster its credentials, to remind the populace of what they have, the pomp and circumstance, the tradition, the history, the elaborate codes. As the massed ranks of cavalry take to the streets, their uniforms bold, their weaponry gleaming, they act as reminder of solidity, of the known as opposed the unknown, the complex abyss should we throw everything away. But they also represent a symbol of power, a rigidity of thought, of behaviour.

Many are happy to live under such auspices. To them, a sense of order is all that can be trusted, the only thing holding society together. Reject it, or simply pick at its seams, and one risks destabilisation, a re-framing of the way life has been and should forever be.

How long these types should stay in the ascendancy remains to be seen. Certainly their ways have created a manifestly unfair society, no matter what they might claim.

But for now such questions have been put on pause. For a fortnight at least, the prime minister Liz Truss and her hopelessly unqualified cabinet have been given a breather.

Once Elizabeth II has been lain in her grave however, the obstreperous forces of reality will rise once again, and with them, the familiar voices of my generation of anti-establishmentarians.

© Simon Fellowes 11/9/2022

September 9, 2022

Reduced State

An update from the motherland now that the Queen has slipped away. I was in movie theatre when the news was officially announced. Things had looked ominous since lunchtime when the PM was passed a note during the House of Commons debate on energy prices. Her grim-faced reaction spoke volumes. A copy of the note was then passed to the opposition benches to identical response.

A short while later an official comment was relayed by the royal physicians that the Queen’s status was a matter of concern. Word then came out that members of the immediate Royal family were heading to Balmoral. At this point it became clear the end was nigh, if not within days then hours.

The BBC cancelled all regular programming, the news presenters dressed in black. I watched some of the news footage, but when the Royal correspondent Nicholas Witchell began banging on about the state of mind of the Royal Corgis I decided I’d had enough.

Rain had been falling since lunchtime, but taking advantage of a short break in the downpour, I walked up the hill to my local cinema to watch a screening of the Penelope Cruz/Antonio Banderas movie ‘Official Competition’. The trailer suggests the film is a broad comedy but in fact it is more than that: a clever examination of actors’ egos, the skill of acting itself, and the idiocy at the heart of much movie making. All three leads give excellent performances – Cruz especially, able to balance absurdity with intelligence.

Within minutes of the movie starting however, there was a technical fault in the cinema, the screen switching to the film being shown in the adjacent screening room, an NFT live stream of ‘Much Ado About Nothing’. I later figured out that this must have happened at the exact moment the official announcement of the Queen’s death was being made.

Someone went to find one of the cinema workers, and within minutes the problem was rectified, the film digitally rewound and replayed from the beginning. However, in the rush to fix the problem, the film was now screened in a reduced perspective (the one used by the NFT). It therefore looked diminished, as if we were watching on a large TV screen.

Nevertheless, unwilling to interrupt the film again, we the British audience, stoic and as uncomplaining as ever, watched (and enjoyed) the film in its reduced state.

In hindsight it felt symbolic; the kind of behaviour of which the Queen herself would have approved.

© Simon Fellowes 9/9/2022