C.J. Stone's Blog

October 7, 2025

Who Vs. The Whovians

Exterminate/Regenerate: The Story of Doctor Who by John Higgs.

Exterminate/Regenerate: The Story of Doctor Who by John Higgs.John Higgs is my favorite contemporary author. Each new work is like a revelation. I’ve reviewed a number of his books in Splice Today: here, here, here and here. I’d recommend any of them. You’ll see by the subject matter the extraordinary range of his interests, from Watling Street to William Blake; from the KLF to the Beatles. He’s at his best when writing about British popular culture and history from his own unique perspective.

His new book, Exterminate/Regenerate: The Story of Doctor Who is, as its title makes clear, the story of the long-running BBC TV series. It’s had a major effect on the imaginations of British schoolchildren since it was first broadcast on November 23rd 1963. That includes me. Watching the title sequence had a profound impact. Nothing like it had been seen on British television. It had an arresting theme tune, groovy and at the same time avant-garde. It was purportedly the first piece of electronic music to be used in a title sequence on television. It’s gone on to influence generations of musicians, including Aphex Twin, the Chemical Brothers and Paul Hartnoll of Orbital, all of whom cite it as the beginning of their interest in electronic music.

This wasn’t the only first for Doctor Who. The producer was Verity Lambert, the BBC drama department’s first female producer, and the serial was directed by Waris Hussein, the BBC’s first Asian director. Both were young, in their 20s. The program was conceived by Sydney Newman, a Canadian producer, recently hired from a rival commercial station. As such Doctor Who was created by outsiders, for outsiders, and it has continued to appeal to outsiders ever since. It’s the longest running science fiction series ever to appear on TV.

I remember that first program clearly. I was 10, and it had a mysterious effect on me. The Doctor back then was nothing like the cheery trickster we see today. He was sinister and threatening, emerging like a shadow from his police box in the middle of a junk yard, and then kidnapping the two teachers who’d followed his granddaughter home. They enter the box only to discover that it’s larger on the inside than the outside, and is some sort of a futuristic time machine. Higgs compares this to the portals to other worlds that often appear in folk tales and myths. Both the Doctor and his granddaughter turn out to be aliens. They’re all then transported back to the stone age, which is where most of the action takes place.

I was also a witness when the Daleks first appeared on our screens. These are The Doctor’s most famous enemies, which Higgs refers to as “space Nazis”. They were thrillingly scary. This was in the second serial, broadcast in seven weekly parts from December 1963 to February 1964. There’s a wonderful scene in An Adventure in Space and Time, a biographical feature about the first Doctor Who, William Hartnell, written by Mark Gatiss. Verity Lambert catches a bus after the episode had aired, to see all the kids strutting about, putting on Dalek voices. This is when she knows she has a hit on her hands. I can verify that. I was one of those children. I still remember the excitement in the playground as all us kids chanted “I am a Dalek! Exterminate! Exterminate!” waving our hands in front of our chests, or falling to the ground, writhing in agony, in imitation of the victims. It’s something you never forget.

This is what makes Higgs’ book so compelling. He’s taken a fictional character, a person who never existed, and written a biography of him, as if he was a real human being. We have the entire history of the program, from its first conception to its latest manifestation, Doctor by Doctor, over its entire 62-year history. This is an adventure in itself, involving many plot twists and reversals, with subplots and love stories, at least as exciting as any of the individual series in its long and varied career.

You may know the program comes in two distinct parts: the classical era, from 1963 to 1989, featuring seven different Doctors, after which the show was cancelled—returning for one night only, in 1996, starring Paul McGann in a TV movie—and then a revived era, from 2005 to the present, featuring several more. In the second half of the book, dealing with the revived series, Higgs discusses the actor David Tennant’s reasons for wanting to take on the role. “I saw Jon Pertwee turning into Tom Baker,” he recalls. “I remember that experience prompting a conversation with my parents about what actors are and what they do and that was very much the beginning of my decision to do that as a career.” He was three years old.

The program showrunner, who recruited Tennant for the part, was Russell T Davies. It’s Davies’ genius that’s behind the success of the second run of the series. Davies was also influenced by watching the Doctor regenerate as a child. (This is one of the features of the program. The Doctors are regularly dying off and turning into someone else.) He says his first clear memory was of seeing William Hartnell fall to the floor and turning into Patrick Troughton.

“Doctor Who made me a writer,” he says. “I used to make up Doctor Who stories. I used to walk home from school burning with them.”

Between them, Davies and Tennant have inspired a new generation of young people to want to take part in the Doctor Who legacy.

Higgs is an amusing and insightful writer, full of witty observations about his subject. He suggests that the program’s longevity may be due to something that biologists refer to as niche construction. This is the way that a biological entity will alter its environment to secure its long-term survival. As Higgs puts it: “By existing in and engaging with that landscape, it alters it in a way that is hopefully beneficial.” And he compares this to the long-term survival of Doctor Who: “no longer a set of stories reliant on the prior existence of writers and other creative professionals to keep going. It was a set of stories that created the writers and other professionals who would keep it alive.”

There’s then a discussion about what constitutes life. “It generally involves moving, changing, reacting and consuming, which are all things that Doctor Who does. There is a presumption, however, that to be classed as a living thing it is necessary to physically exist. For this reason, the claim that Doctor Who is alive strikes many as absurd. It is far less controversial to say that it behaves like a living thing, not that it is one. That position seems far more reasonable. It only becomes troubling should you attempt to work out what the difference is between something that is a living thing, and something that just acts like one.”

I haven’t followed the series since its revival. It’s one of the features of the program that everyone has their own favorite Doctor. Mine is Tom Baker. As a child I too wanted to write Doctor Who stories, so when Russell T. Davies took on that role, I was resentful, and refused to watch.

Luckily I bumped into a couple of friends in the pub before the book came out. One of them, Craig, told me that he was a fan of Doctor Who. Fans of the program refer to themselves as “Whovians” and they’re often at odds with the makers. I told him about Higgs’ book, which he was eager to read. Later we met in the pub again to discuss it.

There was a revealing misunderstanding at the start. Craig referred to “the Jodie Whittaker era” and I made the mistake of thinking that she was one of the side-kicks. The Doctor usually has a side-kick, often a teenage girl or a young woman. I was showing my inherent sexism. Jodie Whittaker was, in fact, the 13th Doctor, and the first female to play the part.

Craig told me that he’d never been more excited about a Doctor Who book than this one. (And he’s qualified to know, owning and having read hundreds of books devoted to the subject.) He said, “There’s all sorts of things going on at once. It’s bigger on the inside than on the outside.” It was like a love letter to Doctor Who, he said. “It’s about devotion and about identity and about change.”

He said that Higgs uses Doctor Who as a framing device, to show how society and people have changed. “It’s the history not only of Doctor Who, but of the BBC and of British TV culture in general.” He said that it couldn’t have happened anywhere else but the BBC, and in any other decade than the 1960s. “An era defining, unique show about a unique character, not from the pages of literature, but created first for the exciting, still relatively young medium of television. A revolutionary, escapist program, with all that post war hope of future change and advancement, yet exploiting so much of the fear and horror of the war years. A defining show in a defining era, on the edge of new discoveries; the space race, science, and the ‘white heat’ of technology, Doctor Who would go on to define many eras. Much like time travel itself, always of its time, but timeless,” he said.

He then told me about his own relationship to the series. His first Doctor was Peter Davison. “As beige as his costume,” he joked. He went on to say that, in truth, choosing a favorite Doctor is a bit like choosing what to eat. “It depends what mood you’re in. And why limit yourself when there’s so much on offer?”

Craig’s a wheelchair user. During the so-called “Wilderness Years,”, when the program was cancelled, he kept himself going by sending his mum out with a shopping list for her to scour the second-hand shops. He had several friends who also helped feed the beast, including a postman friend and an indulgent uncle. He subscribed to Doctor Who Monthly–the longest running TV tie-in mag in history (yet another Doctor Who first). There were also books, audio books, videos, CDs and fledgling dial-up websites, complete with flash animation cartoons, to help keep the flame alive. He never lost hope that one day the TARDIS would fly back into peoples’ living rooms and hearts once again.

He said that when he was a child, his mum would stick on a video, and he’d be happy for an hour or two while she went out. I was intrigued by this. It occurred to me that there’s nothing more expansive in its scope than Doctor Who. It must’ve been liberating for a person of limited mobility to allow his imagination to roam free, with all time and all space to play around in.

It was Craig who suggested that the program appeals primarily to outsiders—gay people, disabled people, trans people and to the neurodivergent, as well as to rebels and artists and children everywhere. Children are perpetual outsiders in the adult world.

The Doctor’s the ultimate outsider, an alien being from another planet, but he (and occasionally she) always wins in the end. He’s also a fighter for justice and on the side of oppressed people everywhere. Perhaps this is what explains the appeal.

Story originally appeared here.

https://www.eldaddruks.studio/

https://www.eldaddruks.studio/

October 22, 2024

The End of Israel

Judaism is a religion, not a race. Jews have no more exclusive right to the Holy Land than Christians, say, or Rastafarians. There are black Jews, middle eastern Jews, white western Jews, mixed-race Jews, even Palestinian Jews. You can convert. People have converted, many times. Whole tribes who were previously not Jews elected to become Jews. For the women it’s easy. For the men, slightly less so, but still doable. You have to be willing to put up with a certain amount of discomfort for a while. (I’m wincing slightly as I think of this.)

Likewise, the Bible is symbolic, not literal. It is myth, not history. There probably never was a King David or a King Solomon. There probably never was a Moses, or an Abraham. If any of these characters ever existed, they have been mythologised: like Hercules, or Jason and the Argonauts. Biblical stories are not facts, but they do tell us certain truths. They carry hidden messages. They are parables, allegories, metaphors. The promises contained in them have to be understood spiritually. God was not offering his people a piece of real estate, but a state of mind. The promised land should be understood figuratively, as something that is yearned for, hoped for, wished for, longed for, in the deepest recesses of the soul, but never fought for, never killed for.

To be a Jew you have to follow the Torah. The Torah specifically prohibits a number of actions. You shall not kill. You shall not steal. You shall not covet. You shall not bear false witness. God’s promises are conditional. If you do any of these things you are not a Jew. The promises are made null and void by the breaking of the Law. Therefore the people of Israel (most of them) are not Jews. They break the Law every day.

They are Zionists. Zionism is a political ideology. It takes the politics of domination and conquest and dresses it up in religious clothing. Most of the early Zionists were atheists. They did not believe in God, and yet they laid claim to the land of Israel as promised to them by God.

Zionism is a settler colonial project aimed at stealing the land from the indigenous population, many of whom have deep historical roots going back centuries, if not millennia. The Palestinians are the descendants of Canaanites, Philistines, Israelites, Jews, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Crusaders: all the people who have criss-crossed this strip of land, at the crossroads of the world between Egypt and the Fertile Crescent, and left their DNA behind. They are a semitic people, speaking Arabic, one of a nest of semitic languages that defines the population group. Zionism aims at removing those original people, and replacing them with settlers. It is a supremacist ideology. Zionists believe they are superior to other people. They see other people – specifically Palestinians – as inferior, less than human. “Human animals,” as Yoav Gallant, the Israeli Defence Minister called them.

Many settlers have dual nationality: that is, they already have homelands of their own. They are from all over the world – North America, South America, Western Europe, Eastern Europe, Asia, everywhere but Israel – but the Israeli “Law of Return” allows them to settle in Israel, while Palestinians, born in Palestine, but driven from the land in one of the many pogroms, have no such right.

BDS

People say that the Israel-Palestine conflict is complex and intractable, and it is difficult, but the solution lies within the world’s grasp. Israel only exists because of the military backing of the West. Once the West removes its backing, Israel will fall. This is why we should do our best to undermine Western support for Israel, to question governmental and institutional investment in Israel, to enact BDS: Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions. BDS brought down apartheid South Africa. It will bring down apartheid Israel too.

States do not have a right to exist. People have a right to exist. Afrikaner rule in South Africa is no more. The Soviet Union is no more. Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, South Vietnam, East Germany: many states have fallen in the last century. They have been nullified by history. The people are still there, but their identity has changed. The same will happen to Israel. Israel is the illegitimate bastard child of American Imperialism, inserted into the Middle East to control the world’s supply of oil, and to keep the nearby states in check. Its days are numbered. It has proved itself to be violently anti-social in its nature. We should no more allow a psychopathic state to exist than we would allow a society of paedophiles to start recruiting members.

All terrorist groups need to be disbanded. That includes the IDF, one of the greatest terrorist armies in the world. An international force with the full authorisation of the United Nations should be brought in to take their place. There can only be a one-state solution. Israelis with dual nationality can elect to return to their homes, or remain in Palestine as law abiding citizens, subject to the democratic rule of the majority. The Law of Return should be revoked and Palestinians granted the right of return. There should be freedom of religion and all peoples who lay claim to the various covenants of the region should be allowed to worship: Jew, Samaritan, Druze, Gnostic, Mandaean, Yazidi, Christian, Alawite, Sufi, Ismaili, Sunni, Shia. No religion should be allowed to dominate another. Everyone should be free to worship, whomsoever and howsoever they choose.

Quite how any of this can happen is another thing. The confusion between the idea of the promised land as a piece of real estate, and the Holy Land as a state of mind, is one that bedevils us all. You cannot, ultimately, own anything. We are all passing strangers upon this earth, free to drink in its delights while we are here, but then gone and forgotten, blown away like dust in the wind. We should savour every moment, every passing beauty – every shaft of sunlight through the trees, every bird’s call, every breath of air that stirs the leaves – but know that we cannot hold on to any of it. Its secret is in the moment, a wealth deeper and more enriching than all the gold in Fort Knox, and yet as insubstantial as the breeze. This where the Holy Land truly lies, not in substance, but in feeling: not in property but in what we give away, freely, from the generosity of our hearts.

https://www.eldaddruks.studio/

https://www.eldaddruks.studio/https://www.splicetoday.com/politics-and-media/the-end-of-israel

Judaism is a religion, not a race

Judaism is a religion, not a race. Jews have no more exclusive right to the Holy Land than Christians, say, or Rastafarians. There are black Jews, middle eastern Jews, white western Jews, mixed-race Jews, even Palestinian Jews. You can convert. People have converted, many times. Whole tribes who were previously not Jews elected to become Jews. For the women it’s easy. For the men, slightly less so, but still doable. You have to be willing to put up with a certain amount of discomfort for a while. (I’m wincing slightly as I think of this.)

Likewise, the Bible is symbolic, not literal. It is myth, not history. There probably never was a King David or a King Solomon. There probably never was a Moses, or an Abraham. If any of these characters ever existed, they have been mythologised: like Hercules, or Jason and the Argonauts. Biblical stories are not based on facts, but they do tell us certain truths. They carry hidden messages. They are parables, allegories, metaphors. The promises contained in them have to be understood spiritually. God was not offering his people a piece of real estate, but a state of mind. The promised land should be understood figuratively, as something that is yearned for, hoped for, wished for, longed for, in the deepest recesses of the soul, but never fought for, never killed for.

To be a Jew you have to follow the Torah. The Torah specifically prohibits a number of actions. You shall not kill. You shall not steal. You shall not covet. You shall not bear false witness. God’s promises are conditional. If you do any of these things you are not a Jew. The promises are made null and void by the breaking of the Law. Therefore the people of Israel (most of them) are not Jews. They break the Law every day.

They are Zionists. Zionism is a political ideology. It takes the politics of domination and conquest and dresses it up in religious clothing. Most of the early Zionists were atheists. They did not believe in God, and yet they laid claim to the land of Israel as promised to them by God.

Zionism is a settler colonial project aimed at stealing the land from the indigenous population, many of whom have deep historical roots going back centuries, if not millennia. The Palestinians are the descendants of Canaanites, Philistines, Israelites, Jews, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Crusaders: all the people who have criss-crossed this strip of land, at the crossroads of the world between Egypt and the Fertile Crescent, and left their DNA behind. Zionism aims at removing those original peoples, and replacing them with settlers. It is a supremacist ideology. Zionists believe they are superior to other people. They see other people – specifically Palestinians – as inferior, less than human. “Human animals,” as Yoav Gallant, the Israeli Defence Minister called them.

Most settlers have dual nationality: that is, they already have homelands of their own. They are from all over the world – North America, South America, Western Europe, Eastern Europe, Asia, everywhere but Israel – but the Israeli “Law of Return” allows them to settle in Israel, while Palestinians, born in Palestine, but driven from the land in one of the many pogroms, have no such right.

BDS

People say that the Israel-Palestine conflict is complex and intractable, and it is, but the solution lies within the world’s grasp. Israel only exists because of the military backing of the West. Once the West removes its backing, Israel will fall. This is why we should do our best to undermine Western support for Israel, to question governmental and institutional investment in Israel, to enact BDS: Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions. BDS brought down apartheid South Africa. It will bring down apartheid Israel too.

States do not have a right to exist. People have a right to exist. Afrikaner rule in South Africa is no more. The Soviet Union is no more. Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, South Vietnam, East Germany: many states have fallen in the last half century. They have been nullified by history. The people are still there, but their identity has changed. The same will happen to Israel. Israel is the illegitimate bastard child of American Imperialism, inserted into the Middle East to control the world’s supply of oil, and to keep the nearby states in check. It’s days are numbered. It has proved itself to be violently anti-social in its nature. We should no more allow a psychopathic state to exist than we would allow a society of paedophiles to start recruiting members.

All terrorist groups need to be disbanded. That includes the IDF, one of the greatest terrorist armies in the world. An international force with the full authorisation of the United Nations should be brought in to take their place. There can only be a one-state solution. Israelis with dual nationality can elect to return to their homes, or remain in Palestine as law abiding citizens, subject to the democratic rule of the majority. The Law of Return should be revoked and Palestinians granted the right of return. There should be freedom of religion and all peoples who lay claim to the various covenants of the region should be allowed to worship: Jew, Samaritan, Druze, Gnostic, Mandaean, Yazidi, Christian, Alawite, Sufi, Ismaili, Sunni, Shia. No religion should be allowed to dominate another. Everyone should be free to worship, whomsoever and howsoever they choose.

Quite how any of this can happen is another thing. The confusion between the idea of the promised land as a piece of real estate, and the Holy Land as a state of mind, is one that bedevils us all. You cannot, ultimately, own anything. We are all passing strangers upon this earth, free to drink in its delights while we are here, but then gone and forgotten, blown away like dust in the wind. We should savour every moment, every passing beauty – every shaft of sunlight through the trees, every bird’s call, every breath of air that stirs the leaves – but know that we cannot hold on to any of it. Its secret is in the moment, a wealth deeper and more enriching than all the gold in Fort Knox, and yet as insubstantial as the breeze. This where the Holy Land truly lies, not in substance, but in feeling: not in property but in what we give away, freely, from the generosity of our hearts.

https://www.eldaddruks.studio/

https://www.eldaddruks.studio/Also on Israel/Palestine: https://www.splicetoday.com/politics-and-media/where-s-daddy

October 17, 2024

Rockets Over Blueberry Hill

by

I’ve witnessed four youth music rebellions in my life: rock ’n’ roll, psychedelia, punk and rave. There may be more but, if so, I wasn’t a party to them.

Rock ’n’ roll is coterminous with my birth. The first rock ’n’ roll record to chart in the USA – Crazy Man, Crazy by Bill Haley and the Comets – did so in the week of the 20 June 1953, the week I was born. Bill Haley had been a Western Swing artist, but, after recording a rockabilly version of Ike Turner’s Rocket 88 (considered by many to be the first rock’n’roll record) he changed his style. You can see this as healthy opportunism. Rock ’n’ roll was a development of Rhythm and blues, a black music form. Haley saw the potential in the music and repackaged it for a white audience.

There’s a crucial difference between the two versions. Bill Haley sings, “going round the corner and havin’ some fun, takin’ my Rocket on a long, long run,” while Jackie Brenston in Ike Turner’s version sings, “goin’ round the corner and get a beer, everybody in my car’s gonna take a little pill.” What’s odd here is that none of the lyric sites give the actual words. It’s always some version of the Haley lyric, or the Brenston lyric with the word “nip” substituting for pill. It’s about time someone corrected that.

Rock ’n’ roll was the background music to my life growing up in the 50s. My favourite record as a child was Blueberry Hill by Fats Domino. I had it on 78. I guess it was my mum’s. It sounded so ancient, like something that had been created in the primeval swamp at the beginning of time. I had no idea that, actually, it was a recent release, having come out in 1956, only two or three years before I was listening to it. I played it every morning before I went to school. There was something in the quality of the voice, and in the jaunty melancholy of the melody, that drew me in and overwhelmed me with a kind of gentle, sweet sadness.

Blueberry Hill seemed like a place I would like to go. I associated it with a girl I was in love with and who I had a dream about. We were soaring high on the back of a white swan, me and the girl, high, high in the endless sky, with the little toy town world spread out below us, all the tiny cars moving along the roads, and the miniscule houses with people in them. My heart was soaring too, exultant, expansive, reaching out into the far distance, till it flew on ahead and came to a mountain and just under the summit there were all these jewel encrusted pillars with many colours glinting in the sunlight. It was a place of pure beauty that wrenched my heart with the ache of love.

I used to play Blueberry Hill on a little Dansette record player with a lid. The 78 was bigger than the deck, and one day the lid fell down, breaking the record in two. It was one of the great losses of my childhood.

Another memorable record was Elvis Presley’s Wooden Heart. Not strictly rock ’n’ roll, it dates from Presley’s time in the American army, and is based upon a German folk song, Muss i denn. What makes it meaningful for me is that it was through this song that I discovered irony. I associated it with the film, Pinocchio, which I must have seen around this time. Pinocchio, of course, was a puppet. He was made of wood and he did have a wooden heart. There were strings upon that love of his, because he was a puppet. So I imagined Elvis as Pinocchio, singing in that melancholy voice that he didn’t have a wooden heart, when actually he did. That was the irony. He was wishing he didn’t while saying he did: a strangely sophisticated thought for a 7 year old boy.

What this says about me I can’t say. There was always a kind of melancholy to my fantasies, a sense of loss. In my cowboys and Indian fights, when I was shot and fell down, I would often construct a back story that involved someone grieving over me.

Rock’n’roll in 50s Britain was accompanied by the first recognisable post war youth movement, the Teddy Boys, or Teds. Their name was based upon the Edwardian suit jackets they wore, which the Daily Express shortened to “Teddy”. They were generally working class kids rebelling against post war austerity. Their suits, with velvet collars, were meant to signal style and affluence. They adopted rock ‘n’ roll as their musical form, and were known for carrying flick-knives and for rioting during showings of the American film Blackboard Jungle, which featured Bill Haley and the Comets playing Rock Around the Clock. It was the first time rock ’n’ roll was heard in Britain. My uncle Rob, my mum’s youngest brother – only 7 years older than me – was a bit of a Ted in his time. I remember him working on his quiff in front of the mirror in our living room, combing back his hair repeatedly on the sides and then pulling it forward in the front to make the quiff. One day he made a home made bomb out of sugar and fertiliser packed into a metal pipe which he used to blow up a tree in our local woods.

Another of the crazes of the 50s was skiffle. This was a British version of American blues and folk. The foremost skiffle group of the time was Lonnie Donegan‘s, whose first record was a copy of Lead Belly’s Rock Island Line, sung in a very pronounced American accent.Skiffle groups were characterised by acoustic guitars and improvised instruments such as the washboards and the washtub bass. Most of the 60s British rock acts began as skiffle groups. Donegan changed his style in the end and began singing in his native Essex accent, as witnessed by his 1960 hit My Old Man’s A Dustman.

I was 10 when I heard my first Beatles record, Please, Please Me. It was different to anything else at the time: lively, catchy but also sly and suggestive. Listening back it reveals the relationship that the Beatles had with their girl fans, who would have understood the references. My favourite early Beatles record is Twist and Shout, a cover version of a song originally recorded by the Top Notes, then by the Isley Brothers, who had a US hit with their version. The Beatles’ is still the best: fast-paced, infectious, with Lennon’s rasping vocals, rising to a screaming crescendo at the end, it shows what a great little rock ’n’ roll band they always were. The Beatles had begun as Teds. If you look at the first album cover Ringo still has his Teddy Boy quiff. He’s only just joined the group and hasn’t adopted the Beatles cut yet.

British interest in American music led to a further delving into its history and the discovery of the blues. A number of the best known groups of the 60s started off as blues acts, most notably the Rolling Stones, who had a number one hit with Willie Dixon’s Little Red Rooster in 1964. It remains the only blues song ever to reach the top of the UK charts.

The reference to “a little pill” in Ike Turner’s Rocket 88 reminds us that there has always been a relationship between popular music and drugs. In the 50s and early 60s the main drug was speed, amphetamine, which allowed its users to stay up all night and dance – that’s what Rock Around the Clock is about – but by the mid sixties new drugs had become available which began to alter the character of the music: marijuana and LSD. It was the introduction of these drugs that led to the creation of psychedelia, the next great musical form to take over Britain and the world.

—Follow Chris Stone on X: @ChrisJamesStone

—Story originally appeared here.

About CJ Stone

CJ Stone is an author, columnist and feature writer. He has written seven books, and columns and articles for many newspapers and magazines.

Read more of CJ Stone’s work here, here and here.

Donate

https://www.eldaddruks.studio/

https://www.eldaddruks.studio/

May 30, 2024

Money, Magic and the Imagination

A magical ritual in the City of London

A magical ritual in the City of LondonAccording to Julian Vayne, magic is “the technology of the imagination”. It’s using certain techniques to focus the mind, to make a change in the world. That change may be internal, to do with our own attitudes, our hopes and aspirations, our limitations and anxieties. Or it may be external. We may use magic as a way of influencing or controlling other people.

CJ Stone

CJ StoneHow is this possible, you ask? In a secular world, surely magic no longer has any power. Maybe that’s because we no longer call it magic. Maybe magic is still prevalent in our world, but we call it by other names.

Take money for instance. Money is magic. It is one of the most effective, and all-pervading, “technologies of the imagination” of the last few centuries, particularly in its form as fiat money, paper money.

Think about it. Unlike gold or silver, paper money has no intrinsic value. It costs virtually nothing to produce – fractions of a penny – but can represent any exchange, large or small. And where does that representation take place? In the imagination.

Money is a sigil, a magical sign. It signifies value. We measure the value of things by how much we are willing to pay for them. It works as an integral part of a system of control. In our world there is very little you can do without money. Those who have money are made powerful by it. Those who don’t become servile or oppressed. People will do anything for money. They will degrade themselves. They will lie, cheat, steal, even kill. So the power of money controls the world, and those who control that power, control us.

We call the system “Capitalism”. The word “capital” is from the Latin. It means head. And on June 5th a new head will appear on the bank notes produced by the Bank of England: the head of our sovereign, Charles III.

This is a crucial moment in British history, the birth of a new age: the third Carolean era. The first Charles had his head lopped off in 1649. The second oversaw the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. The reign of both monarchs saw significant shifts in the constitutional arrangements in these Isles. It is our purpose to ensure that the third Corolean age is as transformative as the previous two.

Bank of England – Tivoli Corner

Bank of England – Tivoli CornerThe Bank of England was established in 1694, not long after the death of the second Charles. It is the world’s eighth oldest bank, and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. It has been at its present location, on Threadneedle Street, since 1734. The current building was designed and built by John Soane in 1806. This whole period, from 1660 to 1806, saw the rise of Britain, from a parochial off shore Island on the outer margins of Europe, to a global empire. Part of this was done using the resources of the Bank of England.

It is here that the gold reserves of the United Kingdom are held, and it was from here, from this fortress in the middle of London, that the British Empire was created. And on the North West corner of the Bank, at the junction between Princes Street and Lothbury, there is a weird little architectural anomaly: a copy of the Temple of Vesta in Tivoli, Italy. The perfect place for a ritual.

Vesta is a flame. She is the goddess of the hearth. In Rome she was considered the guardian of the Roman people. Unlike most Roman gods, there were no statues of Vesta, only a perpetual fire that was kept burning by her servants, the Vestal Virgins. So it is appropriate then, that on the 6th June 2024, a New Moon, one day after the head of Charles makes its first appearance on our bank notes, that we should put our notes to the flame, as a burnt offering, a ritual sacrifice to the gods.

Bank of EnglandThe MonumentWe do not do this to do any harm to Charles, the man, who, let’s face it, had no choice in his position. He was born to it. But as well as being a man, a mere mortal—with all the vulnerabilities that this entails—he is also a symbol. As a man he will die. As a symbol he will not. He is the sovereign. He represents sovereign power. It is through this power, called the Royal prerogative, that we are ruled on these Isles.

The Royal prerogative is no longer wielded by the sovereign himself, but by his representative, the Prime Minister. British people are not citizens. We are subjects. We have had our sovereignty taken away from us and invested in the head of state, who in turn has invested it in the institutions of the state, the government and the Bank of England. By burning the note we are letting go the power that is inherent in it.

According to David Graeber, in his book, Debt: The First 5,000 Years: In 1694 a consortium of English bankers made a loan of £1,200,000 to the king. In return they received a royal monopoly on the issuance of banknotes. What this meant in practice was they had the right to advance IOUs for a portion of the money the king now owed them to any inhabitant of the kingdom willing to borrow from them, or willing to deposit their own money in the bank – in effect, to circulate or ‘monetize’ the newly created royal debt. This was a great deal for the bankers (they got to charge the king 8 percent annual interest for the original loan and simultaneously charge interest on the same money to the clients who borrowed it), but it only worked as long as the original loan remained outstanding. To this day, this loan has never been paid back. It cannot be. If it were, the entire monetary system of Great Britain would cease to exist.”

In other words, money is debt. It was created by debt and is maintained by debt. By burning our money, we are forgiving the debt. We are releasing the sovereign power of money into the world. We are changing our relationship to money. We are redeeming ourselves. The word “redemption” means to pay back what we owe, and thus to redeem our property. In the ancient world it referred specifically to debt slavery: enslavement due to debt. To be redeemed was to be bought out of slavery: to become free. Thus to burn money is to set yourself free, both from the enslavement of debt, and from the enchantment of the money sigil.

We will be gathering at the Monument to the Great Fire outside of Monument station, about three minutes walk from the bank, at 12 noon on Thursday 6th June. I will be wearing a top hat with a caduceus on it, and carrying a staff made of English bog oak, with a Celtic cross on top. From the Monument we will process to the bank. Those who wish to burn money can go into the bank to have your old notes exchanged for new. If you wish you can mark your old notes with your own magical sigil. The sigil I will use was designed by Julian Vayne. It consists of a less than sign < crossed by a more than sign >, crossed by an equals sign =. (See above).

Once everyone has their notes, we will process to the Temple of Vesta, where, after a suitable prayer, and a reading from our holy books, we will perform the ritual. We will burn our notes. Don’t worry if you don’t want to burn money yourself, merely being there is enough. I will burn mine and you will be a witness to history.

Facebook Event Page: https://www.facebook.com/events/1496865587898805/

Forgive Us Our DebtsPrevious magical actions in the City of London:(Follow the links at the bottom of each article to read the whole sequence)

Money, Magic and the Imagination – Part I

Donate

August 10, 2023

Let Life Be My Guide

August 4, 2023

The Trials of Arthur Revised Edition

When I first started work on The Trials of Arthur, people thought that I was crazy. If I told them about King Arthur they would say, “so where are you meeting him then, in a mental institution?” It became a hard thing to justify. I’d been moderately successful in my writing career up till then, with columns in the Guardian and the Big Issue amongst others. I’d had two books published. After I started work on what I’ve always referred to as “the Arthur book” my career went into terminal decline. I’m not saying that co-writing a book with a biker who says he’s King Arthur caused that to happen. Maybe it was going to happen anyway. But it was certainly a staging post on my journey to oblivion, a mile-stone on the lonely road to nowhere in my writing career, and very prominent in my memory for that reason.

My first conception of the book was that it would be about protest. I wanted to use the figure of Arthur as the central thread around which I would weave a story about protest and rebellion. There was a lot of it about in the 90s and Arthur had been heavily involved in much of it. But by the time of writing those protests were long gone. Consequently I had to find us some new protests to get involved with.

Thus it was that our first trip was up to Scotland to join in with a protest at the Faslane Naval base on the Clyde, where Britain’s nuclear deterrent is kept.

There were several things about this journey which made it memorable, although none of it went into the book. Firstly that I missed the turnoff for the Motorway, which didn’t bode well. I was losing my way already and we hadn’t even started yet. Then that we picked up Mog Ur Kreb Dragonrider on the way – generally known as Kreb – who was due in court in Scotland on some charges relating to the peace protest. Kreb is as memorable for his personality as he is for his name, being one of Arthur’s staunchest supporters, and a truly unique individual.

We stopped at a Motorway service station on the way to get some breakfast. Arthur and I both had full English breakfasts with bacon and sausages and all the trimmings. Kreb is a vegetarian but opted for the full English too. I can’t remember his exact words now, nor his reasoning. What I remember was his tone, a kind of careful, weighed out deliberateness in the way he spoke, a measured seriousness, accepting the food with a kind of bow, because it was a gift, because he honoured it, and because he wanted to partake fully of the experience as a member of the clan.

A glossy beard https://www.independent.co.uk/news/druid-reunited-with-excalibur-1292317.html

https://www.independent.co.uk/news/druid-reunited-with-excalibur-1292317.htmlAfter a while Arthur took over the driving and our speed increased. We were doing up to 120 mph, tagged on behind another vehicle which Arthur was using as a marker, hanging on to its tail, swerving in and out of the traffic with furious precision, weaving a fine line between destiny and danger. Arthur was driving casually with one hand holding the steering wheel, a look of calm concentration on his face. I was most impressed with his driving and always felt like he was in complete control. Until we got to the other end, that is, after we’d dropped Kreb off in Glasgow and were making our way to my friend’s house in the fading light of evening, and he almost drove directly into a roundabout, missing the turning completely, and I suddenly realised that he couldn’t see anything, that he needed glasses, and I took over the driving.

My friend, Alan, had moved in with a woman with a couple of kids. The kids were most impressed with Arthur, especially his sword. Later on we were starting to get very drunk. Arthur wanted food. He was looking for something to eat and came across some dog biscuits in the kitchen, which he began to eat with relish, to everyone’s amusement. He ate at least eight of them. My friend said, “that’s why he has such a cold nose and a glossy beard.”

The following day we drove over to the Faslane protest site and Arthur almost immediately got himself arrested. He was wearing his robes. I overheard someone talking about the arrest. “What’s that for,” he said, “bad dress sense?” He was arrested along with a Labour MP, a Member of the Scottish Parliament, Catholic Priests, Church of Scotland Ministers and members of the Scottish Nationalist Party. I spent the rest of the day waiting for the phone call to say that he needed picking up. It didn’t arrive till late in the evening by which time I had already started to drink.

The following day we went to pick him up from the Friend’s Meeting House in Glasgow, which is where he’d been dumped after his arrest. He was standing on the step outside smoking a cigarette. It looked like he had been standing there all night. Later on we went to find Kreb at the peace camp and then went for a walk. There was an old empty Manor House nearby, which looked like a Pre-Raphaelite castle, and Arthur was talking about squatting it. It seemed like a great place for an Arthurian squat. We were in the garden and there was this old tree with a bough that stooped down low to the ground. Me and Alan both tried climbing it, but neither of us could manage. Alan found this stick and was practicing his swordplay, holding it over his head, making out like he was a Samurai warrior. And then we turned around and there was Arthur perched in the tree, lying on his side like a reclining Buddha, looking like some kind of a tree elf with a look of impish mischief on his face. It was so quick and unexpected it felt like he must have levitated himself to get there.

After that we bought some cider and Arthur was immediately drunk. He only had to open the bottle and smell the contents. We got back to Alan’s place and one of the locals called in, a very broad and muscular lesbian. “Nice tits,” Arthur commented while sucking on his cider bottle. That’s one of his chat-up lines.

“Arthur!” Alan shouted in amused outrage, “she’s a lesbian.”

“I don’t care,” Arthur said, “she’s still got nice tits.”

And that was the end of our first attempt to get material for our book.

A binThe plan was that I was going to follow him around for a year, and work that into a narrative with his past life as a series of flashbacks, but it became quickly apparent that driving him about in hired cars and paying for everything would soon eat up the advance money. I decided to use the story of my original search to find him instead, but we had a new difficulty now. It was joint authorship. Who’s voice was I going to use?

A month or so later we met again in Amesbury for one of the round-table meetings about access to Stonehenge. I had a return ticket on the train. After the meeting we went to the pub to discuss the book, and that’s where we decided on the ploy of writing in the plural: “we” instead of “I”, “our” instead of “my”.

We were soon quite drunk. I said, “I’ll have to get back Arthur, I’m going to miss the train.” I got out my tickets to show him.

“Trust me,” he said, “I’ll get you home,” and he snatched the tickets from me and ripped them up.

So, several hours and many pints later, after a bag of chips and a battered sausage from the chip-shop, we made our way up to the Countess roundabout on the A303 in order to hitch home. After about five minutes Arthur slumped to the floor under his cloak and promptly fell asleep. It was early in the year, February, and very cold. I was marching up and down with the cold. No one was driving past. Those that did saw a crazed middle aged man alongside the body of a dead King. They probably thought it was regicide.

I was jumping up and down with the cold. I was walking about exploring, beating myself with my arms to stay warm. The service station was closed but the entrance lobby was open. I went in there and tried to sleep but couldn’t. The floor was rough and hard. Outside again I found what I supposed was the outlet for the refrigerator units inside. It was blowing out warm air. I stood under the air flow and tried not to die of exposure. This went on for several hours, but I was so tired, I really needed to lie down. The lobby was locked by now. Someone must have crept up without me seeing and turned the lock. Or maybe the lock was automatic, in which case it was a good job I wasn’t inside. There were some dumpster style bins nearby full of cardboard. So I climbed into one of these, pulled the cardboard around me and over me, and, though I didn’t sleep, was at least lying down and moderately warm.

The following day we caught a bus from Amesbury to London. So Arthur had kept his promise. He’d got me home all right…. by allowing me to pay for our tickets on the bus.

Glastonbury Arthur Pendragon in 2009

Arthur Pendragon in 2009Later that year Arthur came to visit me in my hometown, in Kent. The historical Arthur is a Celtic hero, of course, while Kent is the seat of the Saxons, the traditional enemy. While Arthur was staying with me I had this dream, about a small white dragon emerging from the waters of a river. It was a very vivid dream. The dragon was palpably real, snorting with a cold breath, about the size of a small horse, but stockier. Pure, albino white, the water running off its back shining in the sunlight. Afterwards I realised that this was the symbol of Kent, normally depicted as a white rampant horse, rather than a dragon.

This was in 2001. Everyone knows what happened in September of that year. I was getting seriously blocked with the book by now and could no longer see the point of it. Bigger things were happening. Who cared about some crazy biker and his pretensions to legendary status? The whole world was falling to bits.

I’d started to grow very depressed. I was drinking on my own and not writing. The book began to feel like a terrible burden I was carrying, a millstone around my neck. For once that’s a cliché that almost exactly describes the feeling: like a dead weight dragging me down. I couldn’t get any other work. No one was taking me seriously any more. I was telling everyone that I never, ever wanted to write another book. It was a vicious cycle. Whenever I thought about it a kind of stultifying heaviness descended on my mind and I couldn’t lift myself enough to write, but the failure to write was just increasing the weight.

I think now that I was approaching something near to a clinical depression. This wasn’t made any easier by the fact that people were scoffing very noisily at my project. I thought I was looking at the end of my writing career. But here’s a measure of all of that superfluous noise: one of the people who was snorting the loudest at the time later died of alcohol poisoning in the Philippines having sired a child with a teenage prostitute. So who, now, seems the craziest?

Meanwhile Arthur was growing increasingly restive about the lack of progress with the book and had asked a mutual friend to help. So I was invited to Glastonbury with the idea that I would be fed and watered while I got on with the writing. This was in the beginning of 2002.

I have to say this helped: not only having food cooked for me, and people to sit with in the evening, but someone to read the book to after I had finished my days’ writing. The book began to move again. In fact it started to get good. I was writing about the protest scene by now, and suddenly it all began to have relevance again. Yes, the world was turning apocalyptic before our very eyes. Yes, an almost literal hell was being unleashed upon the Earth by the forces of war and insanity. But memories of people’s defiance in the road-protest scene of the 90s seemed like an antidote to that. Something real. Something hopeful, with Arthur’s particular blend of egotism and heroism at the heart of it. People putting themselves on the line for beauty and nature and living up to an ideal.

The deadline had been put back several times by now, and, with most of the book finished, I quickly tossed out an introductory chapter and a conclusion knowing that I would be asked to rewrite them both once the editing got under way. They asked me to rewrite the conclusion but they never asked me to rewrite the introduction.

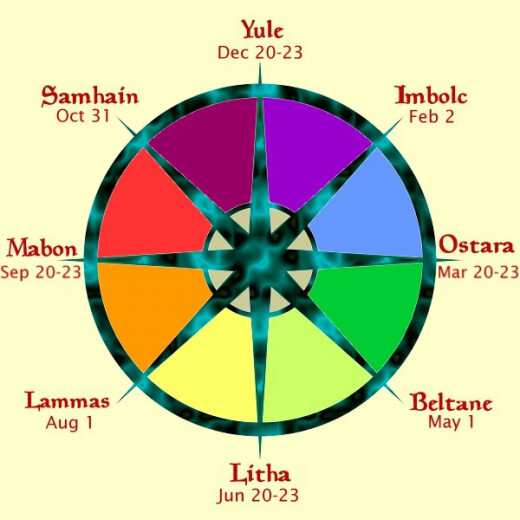

The Wheel of the Year

The book came out in 2003 to no great acclaim. My depression got worse, and I gave up writing altogether to become a postman. My one regret was that I hadn’t made a better job on what would probably turn out to be my last book. It had some good bits, but I always hated the introduction. It was slow and turgid, badly written and clumsy. So when Arthur asked me if I could get the book republished in 2009 I decided that I wanted to rewrite it first.

The Trials of Arthur Revised Edition is the fruits of my labour.

It is the book I always wanted to write.

Not only have I rewritten the first chapter, but I’ve added a number of other chapters too. The original book had seventeen chapters, while the new book has twenty four. It is around 20,000 words longer. Two of the chapters were written by Arthur, the rest by me. We’ve extended the quest element of the first part of the book, while adding a new theme. “The Turning of the Year” represents the pagan calendar as a cycle running through the book. It extends the idea of the quest but specifically attached to the time of year. Thus the first chapter is called “The Turning of the Year: Samhain” and is set on the Prescelly Mountains in Pembrokeshire,West Wales, on Halloween night in 1994.

I won’t tell you about all the new chapters. Suffice it to say that they do what the original first chapter entirely failed to do: they take you right into the action, and then keep you there.

Unlike the original, this is a book I am immensely proud of.

It is also, very definitely, not my last book.

BlurbThis is an updated version of an earlier book “The Trials of Arthur: The Life and Times of a Modern Day King.”

It is more than 20,000 words longer and has nine brand new chapters.

The Central character is a Druid, who is also a Biker.

He claims to be King Arthur, but is actually sane.

It is set in the UK in the mid nineties but it is still relevant today.

It is about someone who may never have existed, and about someone who definitely does exist. About Myth and about meaning. About history and how to make it.. About the world and how to change it. About standing up for what you believe.

It is the Matter of Britain brought up to date.

“So unbelievable it might just be true” Awen Clement, Kindred Spirit

“A haunting elegy to all those people who refuse to accept that they can not make a difference in a world they know must change ” Deborah Orr

Reviews on Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2004656#CommunityReviews

Available here:

DonateLike what you read? Please consider donating. As little as £1 would help. Details on my donations page here: https://whitstableviews.com/donate/

July 19, 2023

Why I (re)wrote The Trials Of Arthur

Front cover

Front coverI wrote the original version of The Trials of Arthur between 2000 and 2003.

It was a book I’d always wanted to write.

I’d originally come across Arthur Pendragon in the mid-nineties, through my good friend Steve Andrews, while I was working on my first book, Fierce Dancing.

There was something about the story which caught my imagination.

Just to give you a brief outline: Arthur Pendragon is this ex-soldier, ex-builder, ex-biker who had some sort of a brain storm back in 1986 and decided he was King Arthur. When I heard about him he was already moderately famous, not only as a media figure – he had been on the Clive Anderson show and had had a number of radio and TV documentaries made about him – but he was also central to the campaign for open access to Stonehenge and heavily involved in the road protest scene of the time. By the time I met him, late in 1996, he was living on-site at the Newbury bypass, then the most prominent and fiercely contested of the road building schemes.

Fierce Dancing had featured a road protest and I had already acquired the status of a sort of spokesman for the movement through my columns in the Guardian and the Big Issue.

It was more than just a protest scene. There was something profound and archaic at its heart. It seemed to evoke feelings and ideas that came from a very deep place. It was tribal. It was animistic. It was archetypal. Arthur’s story seemed to fit in well with the general ethos. I spent the better part of 1996 chasing all over the UK looking for him.

I finally met him in August of that year, at Avebury stone circle in Wiltshire, where we both got very drunk, after which, still drunk, I drove him and another bunch of drunken people over to Bath, where we got even drunker.

That was something Arthur and I did a lot of in our early days.

Tongue-in-cheek Back cover

Back coverAt the time my writing style was very tongue-in-cheek, and Arthur seemed a very tongue-in-cheek kind of hero. He often referred to himself as “the nutter who thinks he’s King Arthur”, which tells you a lot about Arthur’s approach to his identity. Had I written the book then it would almost certainly have been a comedy. I would have played it for laughs. It still is a comedy to a large extent, meaning that there are a lot of funny bits in the book. But it also has a serious point, something I’m not sure I would have been so clear about back in 1996.

So, then, the book didn’t get written in 1996. Other things got in the way. And by 2000, when I finally got round to starting work on it, my life had taken an uncomfortable turn. I was no longer a Guardian writer, and I was no longer writing for Faber & Faber either. The book was commissioned by Thorsons/Element, a New Age imprint of Harper Collins. I felt I was going down in the world. And it wasn’t me who got the commission, it was Arthur. So I was going to have to accept joint authorship, and I no longer had complete control over the end product. This was difficult. I was writing to please Arthur, not writing to please myself, which had a detrimental effect upon my style. I was never anywhere near as confident writing this book as I had been with the others.

Arthur’s view of himself is conditioned by his own self-mythologizing, of course. This is something we all do, but it is greatly compounded when you are not only self-mythologizing in the normal way but also identifying yourself with a mythological hero who is attempting to bring the mythology up to date. This is like mythologizing cubed. Mythology times mythology times mythology.

Arthur thinks he’s Arthur because he always has been Arthur. But clearly there had been a life before this which I insisted on exploring. As I said at the time, it will make the book all the more believable if we know where Arthur comes from. This tends to give the book a kind of hagiographical quality at first as in Arthur’s mind he was always destined to be Arthur. This is one of the prime weaknesses of the original book. Arthur emerges as a hero because of some sort of inherent quality he was born with, rather than as someone who stepped up to the mark and took on the role, which I now think is much nearer the truth. It’s not that Arthur is Arthur because he always was Arthur. It’s that he’s Arthur because he’s made himself Arthur. He’s worked at the role and made it come true. He’s evoked the name and taken the consequences. He adopted the name without necessarily knowing what it would involve. But then the name turned round and bit him and he’s never really been the same since.

So I was never very happy with the first part of the book. It was too much “Arthur did this” and “Arthur did that” and “good old Arthur”, without looking into the context or paying very much attention to anyone else.

Protest CJ Stone

CJ StoneLater I started writing about the protest movement, and this is when the original book starts to get really good. In that version of the book, it takes off around the half-way mark, and in the rewrite I’ve virtually done nothing to change the second half. It was always very good and it still is very good.

The book came out in 2003 and then quietly died a death. By 2009 it was out of print, and Arthur had managed to get the rights back. That’s when he approached me and asked if I could get the book back into print.

Thus it was that in early 2010 I started rewriting the book.

The first thing I did was to get rid of the introduction, which I had never liked. It was slow and clumsy and introduced you to characters that later were to play very little part in the book. It rambles all over the place while never locating you anywhere in particular. Later in the book I had made a decision that whenever a place is evoked we would really enter that place. We would step across its threshold and visualise it. If anyone reading this is ever planning to write a book, I would suggest this as good advice. Be there. Make it live. Make the pages come to life. This is very much what I failed to do in the original introduction.

So the new first chapter takes you right into the heart of an adventure: on the Prescelly Mountains in Pembrokeshire, at Halloween in 1994. We are introduced to people as archetypes. It’s not only Arthur as an archetype, but everyone else as an archetype too. This is a much more satisfying way of entering the book. Arthur is seen as one of many, not one on his own, and his story seems all the more profound for that. It is the story of a whole culture.

We also bring in another innovation: the story of the pagan calendar which runs like a thread throughout the book. Each of the pagan festivals is invoked, starting with Samhain, and ending with the Autumn equinox. This is absolutely precise, as Samhain represents the pagan New Year.

Heart Arthur Pendragon

Arthur PendragonThe book still has Arthur at its heart, of course, but it is also much more about the people around him too. It’s about people remaking themselves, just as Arthur remade himself. It is about the making of a culture as much as the making of a man.

The new book has 24 chapters whereas the old book had 17. This makes a difference of seven chapters. But two of the old chapters have been jettisoned, so in fact there are nine brand new chapters in this book. Two of them were written by Arthur, and the rest by myself. You’ll be able to tell the difference. Arthur’s chapters are very much more tongue-in-cheek than mine, meaning that he’s continued the book I might have written in 1996 and proved to me that he still is a tongue-in-cheek hero.

As for its relevance: it is not about contemporary events, but about things which happened back in the 90s. However, it is about protest, and there are even more things to protest about now than there ever were. The book is virtually a handbook for successful protest. We could subtitle it: How To Protest And Stay Sane!

It is also about challenging the mores of the dominant culture. It is about forging a new identity, about seeking something authentic in a world of dross, about finding something real in a world conditioned by advertising slogans. In other words, it is more deeply relevant now than it ever was.

At our first meeting with the publishers back in 2000 I had asked Arthur what he wanted the message of the book to be.

“If I can do it, anyone can!” he said.

Which doesn’t mean you have to wear a dress and a crown to emulate him. It just means you have to be authentically yourself.

—Read more here

—The Trials of Arthur: Second revision 2023 is available here

DonateLike what you read? Please consider donating. As little as £1 would help. Details on my donations page here: https://whitstableviews.com/donate/

April 4, 2023

Spirits in a material world

I had a clear image of this raggle-taggle band of pagan revellers, strutting the hills, and was momentarily drawn into their world-view: “We are the old people, we are the new people, we are the same people, stronger than before…”

First appeared in the Guardian Weekend, June 4th 1994

DOES the Earth have a spirit? That depends upon your point of view of course. Does anything have a spirit? Is there even such a thing? I only pose the question because what follows depends not so much on the answer as on whether you think the question is worth asking in the first place.

The pagan eco-warriors of Little Solsbury Hill, overlooking the watermeadows of Bath, are in no doubt. The Earth has a spirit, as do all things upon it: trees, plants, animals, even rocks and stones. Mother Earth nurtures all creatures, including ourselves. And how do we repay her? We rip her, wound her, tear down those lovely tree-spirit-beings to make way for motorways. I’m speaking for them now. I’m sure they’d agree that this is the essence of their message. So convinced are they by the truth of this philosophy, that they daily perform acts of extreme courage, shinning up the arms of the JCBs, locking themselves to machinery and even – I saw this – throwing themselves behind the reversing wheels of a truck full of hard-core about to disgorge its load.

One of them told me a story which – having observed a number of such things – I feel perfectly inclined to believe. He’d attached himself by a noose to a tree that was about to come down. Had the tree fallen, of course, he would have gone with it. The supervisor came over to him and asked, “are you serious?”

“Look into my eyes and tell me whether you think I’m serious or not.”

I saw that look as he was telling me the story. I’m certain that the supervisor made the right decision in stopping the digger.

Such conviction is both startling and educational. What we are observing here is a new kind of politics: at least in Britain, at least in recent years. Old-style left-wing politics had a tendency to cynicism and behind the scenes wrangling. It appealed to the greed in human beings, not to their idealism. Trade Unionism was inevitably tied to differentials based on collective bargaining power. On the other hand, the crystal gazing self-indulgence of the conventional New Age opted out of politics altogether for personal self-improvement. One philosophy involved sneering reductionism, the other self-righteous self-aggrandisement. Both were peculiarly fitting for the Thatcher years and doomed to failure. The tribal warriors of Little Solsbury Hill, and other places, represent a new New Age: clear on the question of collective action, politically astute and media-wise, spiritually aware without the attendant vanity.

I’d gone there the first time with a BBC Open Space crew to make a film about the Criminal Justice Bill. This is precisely the kind of protest that section 5 of the bill threatens to make illegal depending, as it does, on trespass, peaceful disruption of work and historical squatting rights. Our first encounter was unpromising. They came spilling out of one of the squats, blinking into the light like some mutant horde. One of them launched himself straight at me and began fingering my waistcoat. “Nice waistcoat. What’s it like on the back?” He was trying to pull the coat off my shoulders to see what the material was like. I lit a cigarette to cover my irritation.

“Two’s up on yer fag, mate?”

Just then the cameraman appeared in his Barbour jacket, battery-pack drawn about his waist like a gun-belt, camera, armed and dangerous, slung across his shoulder like a bazooka.

“Nice coat, mate. Ten’s up on yer salary.”

The quips came thick and fast.

“Used to be a hippie. Now he’s all tan…” referring to my costume. He was right, and not just about the colour of my coat. This character turned out to be Lee Tree. I mentioned alienation.

“Don’t talk to me about alienation. My Dad was a miner. I was brought up on the strike. I know all about alienation.”

We were making our way up the hill when – magically – another of the company squatted on her haunches on a small knoll and began to expound. There was something very precise about this, as if this particular spot on the Earth had something to say for itself. She was addressing me directly. This was Sam, who I later discovered to be the Queen of the Donga tribe. She was talking about the trackways of Twyford Down – the famous dongas from which the tribe got its name – and I was particularly drawn to the quality of unaffected sincerity in her voice. She seemed to be speaking to me from some very ancient, sacred space. Meanwhile Lee mentioned a walk they were proposing, along the length of the Ridgeway, dragging handcarts. He was wearing a multicoloured hat like a fairy hood. I had a clear image of this raggle-taggle band of pagan revellers, with their penny-whistles and their bright patchwork clothes, strutting the hills like something out of a fairy-story, and was momentarily drawn into their world-view: “We are the old people, we are the new people, we are the same people, stronger than before,” as Lee was later to say to me.

I asked Lee what the tribe represented in the modern world. “We’re its conscience,” he said. I asked whether they thought they could win this battle. “We’ve already won,” he said. “Every time we get up in the morning and do what’s right, we’ve won.”

As we scrambled to the top of the hill along trails that stretched through trodden down fences, it seemed to me that these were not the only barriers coming down. I’d had this feeling before. It was like an elusive taste in my mouth: the merest hint of Revolution, maybe. It had the same quality you sense during a strike, when the management in in disarray, and the clockwork routine of the day-to-day is momentarily sprung. It is like a breath of fresh, clean air.

At the top the wind blew fiercely and, looking out over the settlements below, it did indeed seem as if we’d come to some ancient place. The old 20th century life seemed not only miles away, but centuries away. From this distance you couldn’t make out a single car.

I WENT back to the hill a week or so later. My second visit was more relaxed. I’d been through the baptism of blagging and the next few days would cost no more than the odd packet of tobacco and a few pints. I arrived at virtually the same time as a band of French students over in Bath on an EFL course. Their teacher was an old radical. We went to view the action as a digger gouged huge bites out of the blood-red earth. The workmen were taken aback at the sight of all these well-dressed students. No one knew what to make of it all. Some of the students, full of youthful ardour, wanted to overrun the machine themselves.

I counted 20 workmen. Most of them seemed to be standing around doing nothing. I asked how many were actually working and was told by the foreman, with an amused smile, “one”. There are four kinds of worker there. You can tell the difference by the colour of their hats. In order of importance: white = supervisor/engineer, green = foreman, yellow = worker, blue = security. There were many more blue hats than any of the others. I asked how much the security men were paid. One of the protesters told me £3.50 an hour, even for the night shift. During the night, I was told, they had to stand on the machinery in all weathers. I asked a workman if it was true they were only paid £3.50 an hour. “£3.43,” I was told, shamefacedly.

Later, I’m led past the ruins of one of the houses that have already been demolished. A gothic gateway leads to a winding drive. There is the bosom of the hill lay a sad tangle of broken bricks and splintered beams where someone once had their home. Now the area is occupied by protesters. They offer me a cup of tea. Someone passes by on the road above and lets out a piercing “Yip! Yip!” The sound is echoed from around the blackened kettle on the fire: “Yip! Yip!” After tea I’m guided to the security men’s HQ, where one of the protesters is perched on the roof. I’m told that the security men won’t let him have food or water up there. It’s against the European Commission on Human Rights, I’m told. Someone is ringing Liberty to complain.

Night-time on the hill. The tribe is gathered round the campfire, kettle boiling on the embers. Tea, cigarettes, and the odd can of beer are the only drugs in evidence. There’s a few incongruous didgeridoos about, but the main instruments are drums and penny-whistles. The music is jigs and reels with a heavy laden beat. Yips, whoops and war-cries pierce the night air. Someone is dancing in the shadows of a nearby tree. The fire-glow flickers around the circle of laughing faces. The thudding of the drums is like an excited heartbeat pulsing to the rhythm of life.

A young woman breaks into the circle, chattering wildly about herself. She tells us that she uses her “Feminine charms” to disarm the security guards. She’s gambolling from subject to subject excitedly. She’s seen the worst of life, been pregnant and on the street at the same time. Maybe she still is pregnant, she’s not sure. She has a shaved head and plenty of piercings. Her parents have disowned her. She’s a philosopher, she tells us. “All life goes in circles. The Earth goes round the sun, the Moon goes round the Earth.” Someone points out that they’re not circles but ellipses. “Oh all right, but they still go round, don’t they?” It becomes clear that no one actually knows her.

All in the garden is not rosy, it seems. The tribe attracts its share of nutters. But, you wonder, where else would they go? There’s also one distinct drawback to tribal consciousness: tribal paranoia. Rumours fly about like sparks from the fire. Conspiracy theory abounds. The strongest and most often repeated on is that there are narks in their midst. Everyone who speaks on matters of strategy makes a general remark aimed at the infiltrators. “Tell your bosses there’s a demonstration planned on such-and-such a date.”

I ASK where I can sleep and am led up the hill by the light of a storm-lamp to the gloomy exterior of a large bender. I’m too tired by now to worry what might be inside (it’s all that fresh air and the fact that my fags have been blagged away twice over by now), but once the tarpaulin is lifted, I’m led into a perfect little home-from-home. There’s a huge, raised futon with a line of teddy-bears propped against the pillow, carpets over the pallet floor, clothes hang neatly from the interlaced branches that constitute the main structure of the building, and against the far wall there’s a neat little wood-burning stove.

Everything is carefully stored away in boxes. The shape finally dismantles the shaven-headed girl’s theories: definitely an ellipse. I fall asleep to the sound of heart-beat drumming.

I’m woken by the sound of the skylark ripping the sky with its exuberant cry. Now I know where that Yip! Yip! sound comes from. Someone arrives to guide me to a current action. There’s a guy perched on the arm of one of the diggers, his body squeezed under the pneumatic piston that controls it: were the digger to be used it would cut him in half at the waist. Consequently the machine is immobilised and now stands blocking the entrance to the raw gash of earth they’ve already gouged out.

There’s a lot of standing about doing nothing. The workmen and the protesters share the odd jibe. “How did you get here then? See, you can’t say you don’t need roads…” Generally the atmosphere is good-humoured. It only begins to tense when a lorry arrives carrying hardcore. One young woman tries to throw herself in its path. The action comes in fits and starts. One minute it’s peaceful, the next all hell is breaking loose, people running this way and that, security men chasing them along the banks of earth deposited by the cutting. It’s a game really. I think even the security men are pleased to have the monotony of their day broken. There’s one guy, middle-aged, with darkened features and untidy dreads, who’s main contribution seems to be running around wildly, saying, “keep it fluffy, keep it fluffy!” “Fluffy” is the buzzword around here. It seems to mean “peaceful” or, in old-fashioned hip parlance, “cool”. There’s Fluffy Pete who wanders around in orange overalls carrying a staff with a white flag who negotiates between the authorities and the protesters. He’s the self-proclaimed negotiator. There’s a Fluffy-bus. A fluffy-this or a fluffy-that. I’m told that I should be fluffy and I’m afraid I bridle at the suggestion.

But – well – fluffy it is. I wonder what the workmen think of all this?

The foreman is Welsh, a real-life Celt for a change. He’s also a poet. He’s just doing his job, doesn’t like all the aggravation. Spend his time gossiping with the protesters whenever the work is flagging and testing them on the logic of their arguments. And one of the security guards is a spirited Irishman who prefers chatting up the women to working. This is just a job for most of them, though one or two seem to get added job-satisfaction whenever there’s trouble.

But this is the moment that sums up all the ironies of this occasion for me. The official poet for the National Trust, “Boots” Bantock, arrives to congratulate the fluffy-posse on their work. He makes a speech. At the sound of his plummy, posh accent you can see the workmen visibly stiffen, their lips curling into well-conditioned sneers. This is a voice that says only one thing to them – privilege. When did he last have to go grubbing about down the job centre looking for work? What does he know of the humiliation of unemployment, the strain of keeping a family together on the dole, or the dreary regularity of a life conditioned by the clock? And for me the confusion sets in as I see how conservative the working class have become.

Everyone is too afraid to challenge anything anymore. The Revolution’s not on overtime. But nor are the workers.

Later I wander down by the watermeadows to see what’s going on. One of the Fluffies is sitting on a low wall gazing abstractly at those huge, heavy-gauge vehicles gnawing at the land and turning it to dust. He’d spoken to one of the blue-hats earlier, he told me. Do you believe that trees have spirits, he asked? Answer: “No.” Do you believe that animals have spirits? “No.” Do you believe that the Earth has a spirit? “No.” And you: do you believe that you have a spirit? Slight pause, then: “No.”

I went to interview some of the neighbours to find out what they thought of the goings-on around here. The first person I spoke to was Josephine Slater, next-door-but-one to the squat where the protesters office was at the time. She was frightened at first, she told me. But after speaking to them, she found them to be lovely people. She said: “It’s not just ravers, it’s not just travellers, it’s actually ordinary middle-class people who have realised that they’re right, who are beginning to see through the duplicity of the government.” She understood the need for some sort of direct action, she said. “The Government rules with only 43% of the vote, how else can we challenge the power of corruption?”